Abstract

Heme is an essential cofactor for many human proteins as well as the primary transporter of oxygen in blood. Recent studies have also established heme as a signaling molecule, imparting its effects through binding with protein partners rather than through reactivity of its metal center. However, the comprehensive annotation of such heme-binding proteins in the human proteome remains incomplete. Here, we describe a strategy which utilizes a heme-based photoaffinity probe integrated with quantitative proteomics to map heme–protein interactions across the proteome. In these studies, we identified 350+ unique heme–protein interactions, the vast majority of which were heretofore unknown and consist of targets from diverse functional classes, including transporters, receptors, enzymes, transcription factors, and chaperones. Among these proteins is the immune-related interleukin receptor-associated kinase 1 (IRAK1), where we provide preliminary evidence that heme agonizes its catalytic activity. Our findings should improve the current understanding of heme’s regulation as well as its signaling functions and facilitate new insights of its roles in human disease.

Heme (iron protoporphyrin IX) is classically viewed as a prosthetic cofactor for oxidoreductases, such as cytochrome proteins,1 as well as a transporter of gases, such as molecular oxygen, in globin proteins.2 In addition to these prototypical roles, there is emerging evidence of diverse heme-responsive pathways that are governed by transient heme–protein interactions.3–5 In this regard, heme has recently been shown to regulate gene expression,6–10 mediate mitotic division,11 modulate ion channel activity,12 activate various sensors,5,13–16 and also promote adipogenesis17,18 and inflammation.19,20 More broadly, given that heme generally has low solubility,21 a network of transporters, chaperones, and other protein binding partners to enable trafficking and mobilization in cells is likely mandated.22–24

Though significant progress has been made in characterizing specific heme–protein interactions, our understanding of the full spectrum of proteins that regulate, or are regulated by, heme remains incomplete. This deficiency is due to, in part, the lack of strategies to globally identify proteins capable of binding to heme. Reported methods to experimentally identify heme–protein interactions typically involve biochemical and spectroscopic approaches on purified protein or gel-based separation and affinity chromatography using immobilized heme on resin,25–29 though such methods are generally only suitable for well-behaved recombinant proteins, interactions of high affinity, and proteins of high abundance. Structure- and sequence-based approaches have been used to predict heme-binding proteins in some instances;30 however, these predictions rely on known binding domains and most have not been experimentally validated.

To obtain a more global portrait of heme-binding proteins and, by extension, a broader understanding of heme-mediated biology, here we developed a photoactivatable affinity probe to map heme–protein interactions in native systems (Figure 1a). We rationalized that the implementation of a photoactivatable enrichment tag would enable the capture of transient interactions that span a broad range of heme–protein affinities in native systems.31–33 We applied this approach to identify 350+ heme-binding proteins in multiple human cell types, including proteins known to be involved in heme biosynthesis, transport, and regulation, as well as numerous proteins previously unknown to interact with heme. We further provide evidence that these newly identified heme binding events may impart functional consequences on their corresponding protein targets.

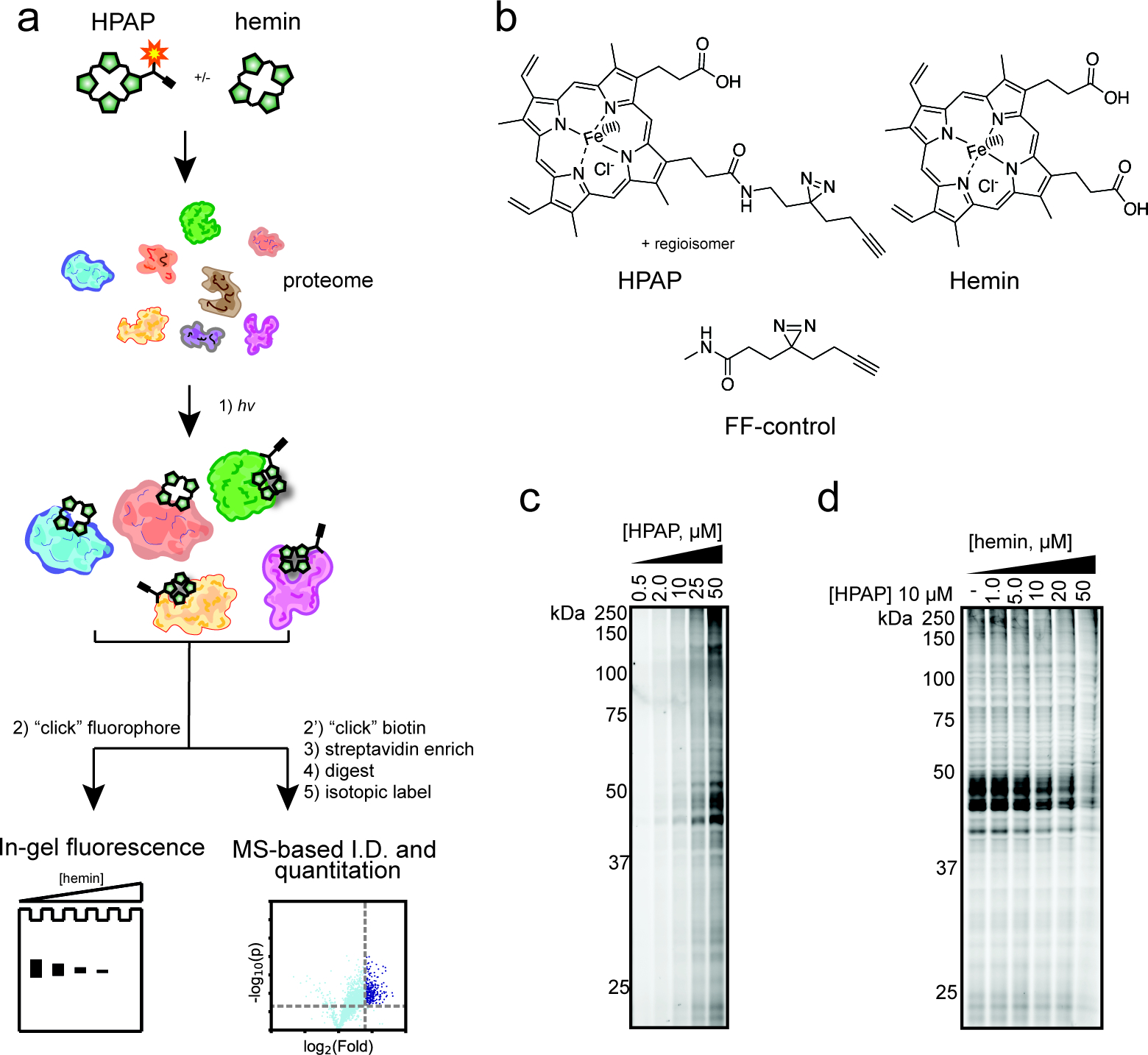

Figure 1.

Chemical proteomic approach to map heme–protein interactions. (a) Schematic workflow using heme-based photoaffinity probe (HPAP) to identify heme-binding proteins. (b) Structure of HPAP, hemin, and FF-control. (c) Gel-based profiling of HPAP-protein interactions in HEK293T lysates. Lysates were incubated with increasing concentrations of HPAP, photo-cross-linked, then conjugated to a TAMRA-azide tag by CuAAC “click” chemistry prior to fluorescence scanning. (d) Competitive blockade of HPAP protein labeling by free hemin.

We first sought to design a “fully functionalized” (FF)34 probe consisting of (i) a heme-based molecular recognition group to engage heme-binding proteins; (ii) a photoactivatable diazirine group for UV light induced cross-linking of probe-interacting proteins; and (iii) an alkyne handle for conjugation to azide reporter tags by copper-catalyzed azide alkyne, or “click”, chemistry (CuAAC).35 A survey of heme–protein structures suggests a substantial fraction of proteins bind heme such that one or both carboxylate moieties are solvent-exposed.36,37 Therefore, we rationalized that a photoreactive retrieval tag appended to either carboxylate would minimize any target binding interference. Considering these factors, we synthesized a heme-based photoaffinity probe (HPAP) in four steps (Figure S1a), resulting in a mixture of two regioisomers at the carboxylate positions (Figure 1b).

We next assessed the ability of HPAP to label proteins in cells using established SDS-PAGE methods.38 In brief, we treated HEK293T cells with increasing concentrations of HPAP followed by exposure to UV light (365 nm), lysis, coupling of probe-modified proteins to a tetramethylrhodamine (TAMRA)-azide tag (Figure S1b) via CuAAC, and subsequent visualization by SDS-PAGE and fluorescence scanning (Figure S2a,b). We observe dose-dependent labeling of both cytosolic and membrane fractions, suggesting that HPAP itself is membrane-permeable and binds proteins stoichiometrically. However, competition studies with excess free hemin resulted in minimal reductions in HPAP labeling, suggesting heme is insufficiently membrane-permeable (Figure S2c,d) to compete for HPAP binding, likely due to the presence of two negatively charged propionate groups relative to HPAP’s one. We next evaluated HPAP in cell lysates, where we observed a concentration- and UV-dependent labeling of proteins (Figure 1c, Figure S2c,d). Critically, HPAP protein labeling is blocked when coincubated with increasing concentrations of unmodified hemin, suggesting that HPAP engages heme-binding proteins (Figure 1d).

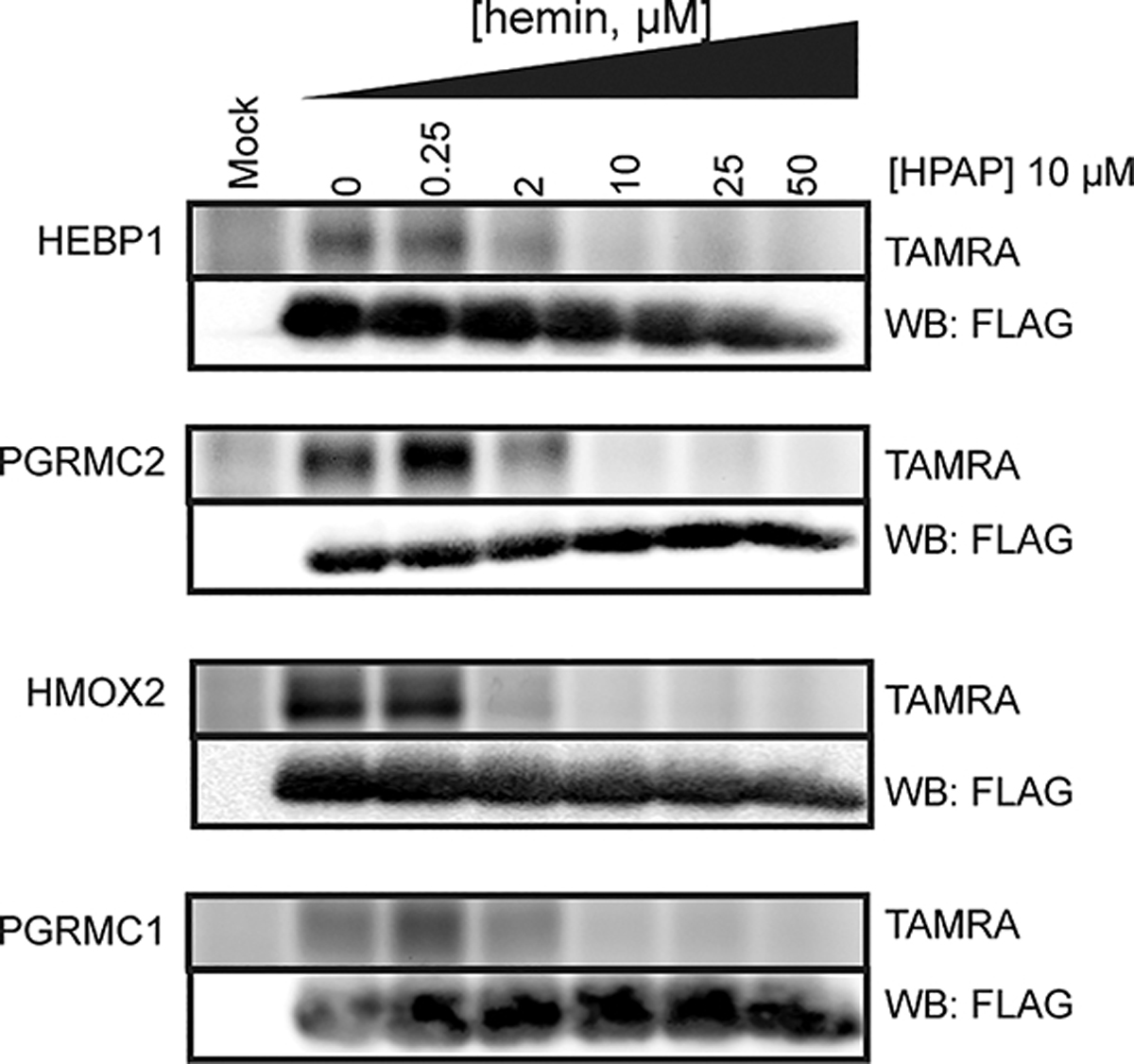

We next sought to confirm that HPAP captures known heme-binding proteins, including heme binding protein 1 (HEBP1; labile heme sensor),39 heme oxygenase 2 (HMOX2; heme catabolic enzyme),40 and progesterone receptor membrane component 1 and 2 (PGRMC1 and PGRMC2; heme chaperones).17,41 Each protein was recombinantly expressed with a FLAG epitope tag in HEK293T cells by transient transfection, and subsequently cell lysates were cotreated with HPAP and increasing concentrations of unmodified hemin followed by in-gel fluorescence scanning. We observed that recombinantly expressed proteins were strongly labeled by HPAP, which was competitively inhibited with hemin (Figure 2, Figure S3). Together, these data suggest HPAP can serve as a useful chemical probe to identify proteins capable of binding to heme.

Figure 2.

Confirmation of HPAP and heme interactions with known heme-binding proteins. FLAG-tagged proteins were recombinantly expressed in HEK293T cells, lysed, and cotreated with HPAP and increasing concentrations of free hemin prior to visualization. Full images are shown in Figure S3.

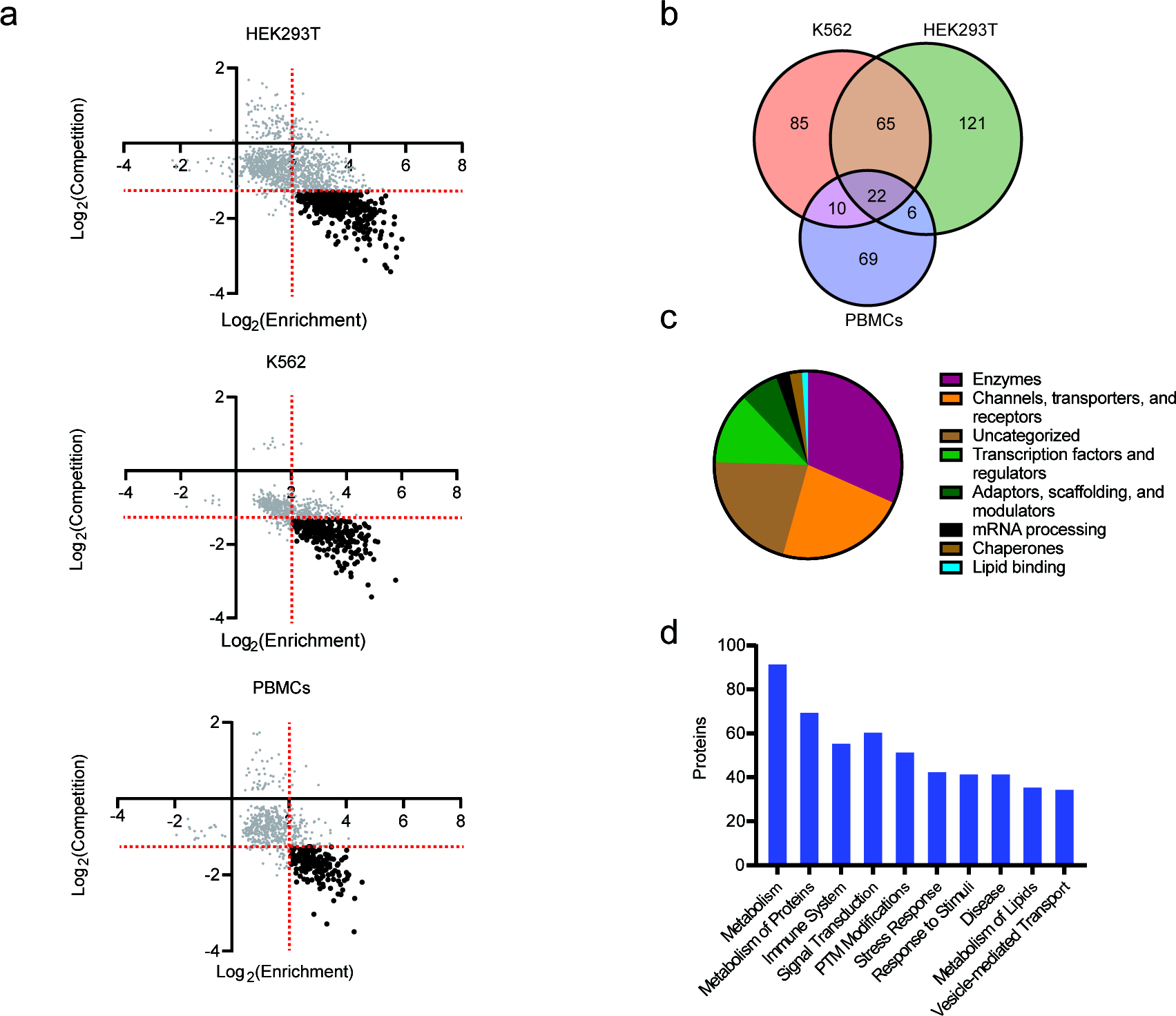

We turned our attention to mapping heme–protein interactions by quantitative mass spectrometry (MS)-based proteomics. For these studies, we evaluated multiple cell models, including (1) the adherent epithelial cell line HEK293T, (2) the suspension cell line K562, and (3) primary human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). HEK293T and K562 cell lines were selected to explore potential differences in proteomic interactions that might emanate from unique physiological characteristics (e.g., tissue origin, anchorage status) and therefore obtain a broader map of heme-binding proteins in the human proteome. We chose to map heme interactions in primary human PBMCs, as heme has been implicated as an inducer of inflammation in a various immune cell subtypes, particularly under hemolytic conditions (e.g., malaria, sickle cell disease).5,13,20 These studies were conducted in two primary experimental formats: (i) enrichment experiments to identify proteins captured and enriched by HPAP relative to a control probe (FF-control, Figure 1b) to account for background proteome interactions of the diazirine tag; and (ii) competition experiments to identify HPAP enriched proteins that are specifically competed with excess unmodified hemin (Figure S4a). For enrichment studies, lysates of each cell type were treated with HPAP or FF-control (25 μM), and for competition studies, lysates were cotreated with HPAP (25 μM) and either DMSO or excess hemin (100 μM). After photo-cross-linking, probe-modified proteins were labeled by CuAAC conjugation to an azide-biotin tag (Figure S1b), enriched with streptavidin-coated beads, proteolyzed into tryptic peptides which were isotopically labeled with tandem mass tags (TMT),42 and subjected to MS analysis, as previously described.38 We operationally defined a heme-binding protein if it was >4-fold enriched over the control and exhibited >3-fold competition with unmodified heme with a p < 0.05 across biological replicates (n = 3) (Figure 3a, Figure S4b, Table S1).

Figure 3.

MS-based profiling of HPAP-protein interactions in human cell lysates. (a) Scatter plots comparing heme-binding proteins in HEK293T, K562, and PBMC lysates. Heme-binding proteins (black) are defined as exhibiting ≥4-fold enrichment (x-axis) by HPAP over FF-control (25 μM) and competed (y-axis) ≥3-fold with excess hemin (100 μM), indicated by red dotted lines. (b) Target overlap between HEK293T (red), K562 (green), and PBMC (purple) cells. (c) Protein class distribution of targets. (d) Top ten biochemical pathways enriched across all targets.

In total, we identified 378 unique heme-binding proteins, including 214 from HEK293Ts, 182 from K562s, and 107 from PBMCs (Figure 3b, Figure S4c). Although we observe some overlap of targets between all three cell types (22), most were unique to one or two cell types (Figure 3b), suggestive of unique expression and potential context-dependent roles of heme in different cells. We noted that among these targets are 19 proteins previously annotated to interact with heme in the UniProt database, including heme biosynthetic (FECH) and catabolic enzymes (HMOX1, HMOX2), chaperones (HEBP1, PGRMC1, PGRMC2), and receptors (BACH1), while the 359 remaining targets are not annotated as heme-binding (Figure S4d). A broader survey of these previously unannotated heme-binding proteins revealed that they consist of members from diverse protein classes, including transporters, transcription factors, scaffolding proteins, and enzymes (Figure 3c) and functional pathways (Figure 3d). This includes transporters such as the mitochondrial SLC family member MTCH2, which currently has no annotated substrates,43 the scavenger receptor CD36, which binds a broad range of ligands, including infected erythrocytes,44,45 nuclear receptors such as NR3C1 and TMEM97, transcription factors including the BCL-6 corepressor BCOR and T-cell differentiator TCF7, lipid biosynthesis enzymes (e.g., AGK, SQLE), and various protein kinases (e.g., MAP2K3, SIK2, STK39).

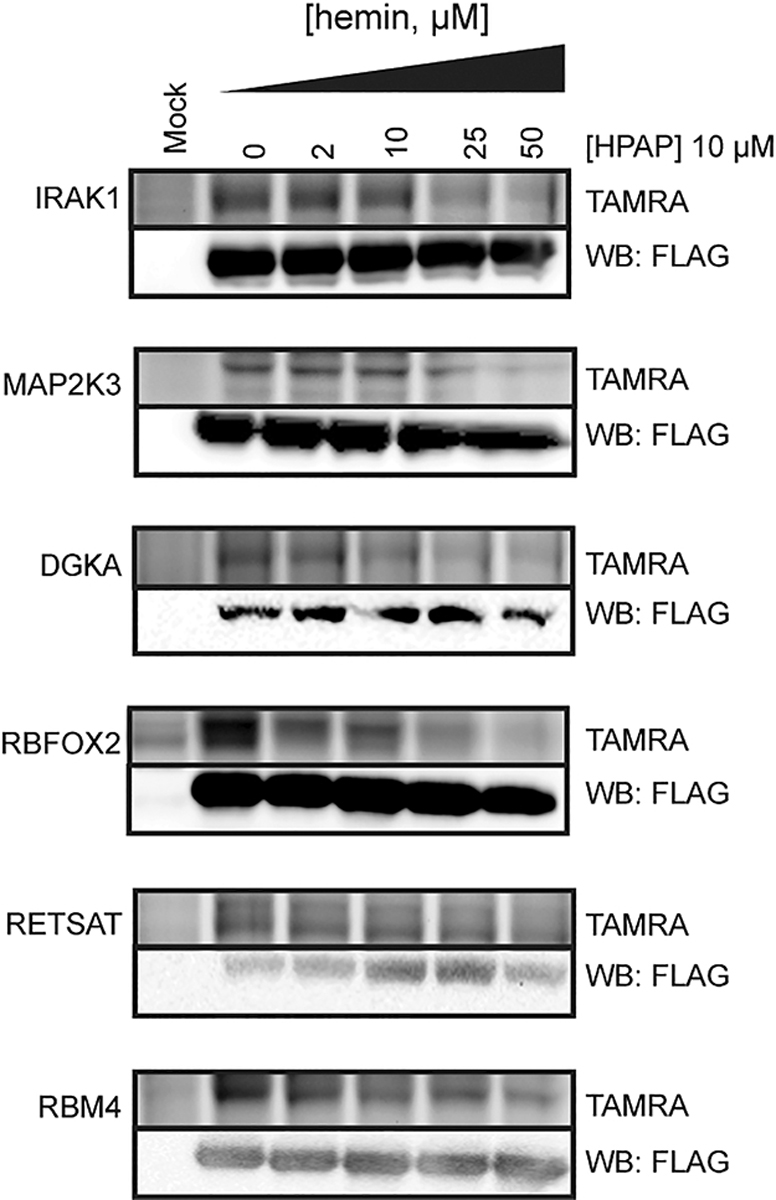

Next, we validated several newly identified heme interactions via treatment of the recombinantly expressed protein, including the following: RBM4, a multifunctional RNA splicing factor;46 RETSAT, a retinol oxidoreductase with extended roles in modulating ROS sensitivity;47 IRAK1, a proinflammatory kinase and component TLR signaling;48 MAP2K3, a protein kinase that modulates MAPK14/p38α signaling;49 RBFOX2, an RNA splicing factor that regulates erythropoietic translation;50 and DGKA, an acylglycerol kinase that controls the synthesis of messenger lipids51,52 (Figure 4, Figure S5). In each instance, we observe strong labeling of the recombinantly expressed target by HPAP, which is effectively blocked when coincubated with free hemin. Together, our results demonstrate that the HPAP probe can be used to identify novel proteins capable of binding heme.

Figure 4.

Confirmation of newly identified heme-binding proteins. FLAG-tagged proteins were recombinantly expressed in HEK293T cells, lysed, and cotreated with HPAP and increasing concentrations of free hemin prior to visualization. Full images are shown in Figure S5.

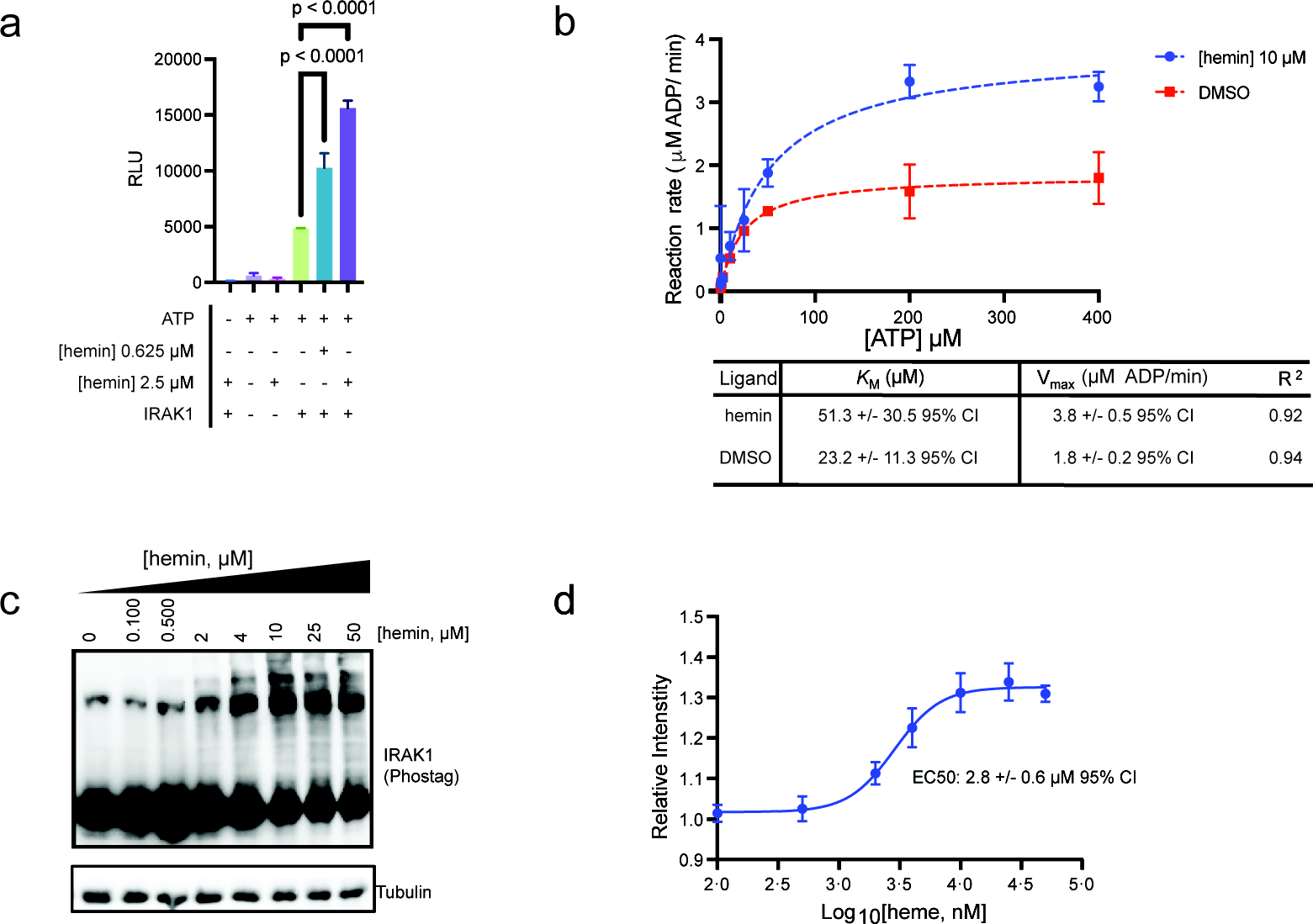

Among the six targets identified and validated in our studies, the serine/threonine kinase, interleukin receptor-associated kinase-1 (IRAK1), plays a critical role in regulating inflammatory signaling pathways. IRAK1 is phosphorylated by IRAK4 and then autophosphorylates, leading to NFkB-mediated inflammation.53–55 Under hemolytic conditions, such as sickle cell disease and malaria, heme is associated with increased inflammation, although the exact molecular mechanism remains unclear.20,56–58 Considering this, we wondered if heme binding might impact IRAK1 enzymatic activity, as heme is also known to regulate the activity of other kinases, such as eIF-2α.59,60 Thus, we examined whether heme affects IRAK1 enzymatic activity by monitoring its conversion of ATP to ADP in the presence of a peptidic substrate. Interestingly, when IRAK1 is incubated with hemin, we observe an increase in ADP production (Figure 5a), suggesting heme might enhance IRAK1 enzymatic activity. We subsequently measured the reaction rate over increasing concentrations of each substrate, ATP and peptide, separately and observed that heme substantially increases the reaction velocity (Vmax) cooperatively with ATP, but not with the peptide substrate (Figure 5b, Figure S6a). We also noted a that heme increases the Km. These observations suggest heme to be an allosteric activating ligand that promotes IRAK1 autophosphorylation under these conditions.61 Indeed, treatment of both HEK293T and THP1, a human monocyte derived cell line, lysates with heme resulted in a substantial concentration-dependent increase in IRAK1 phosphorylation. Together, these data confirm that heme is an agonist of IRAK1 autophosphorylation in these models (Figure 5c,d, Figure S6b,c).

Figure 5.

Characterization of newly identified heme-binding proteins. (a) Quantitation of ATP consumption by IRAK1 treated with heme or DMSO via ADP-Glo assay. (b) Steady state kinetics of IRAK1 to determine the Km and Vmax in the presence of hemin. (c) Immunoblot analysis of IRAK1phosphorylation in HEK293T cell lysates treated with increasing concentrations of hemin followed by SDS-PAGE separation using a phosphor-binding gel matrix. (d) Quantitation of pIRAK1 immunoblotting (mean ± SD, n = 4; Figure S6).

In this study, we have developed a heme-based photoaffinity probe that can be integrated with chemical proteomic workflows to identify heme-binding proteins across the human proteome. We identified many known heme-binders as well as 350+ proteins that, to our knowledge, were not previously known to bind heme. We validated several of these new interactions and present preliminary evidence that heme modulates the activity of one of these targets, IRAK1. Although it is tempting to speculate that heme may influence known downstream inflammatory responses through IRAK1 binding given previously reported activity on this pathway,20,62 further mechanistic investigations in immune cell models are needed. Future studies will also aim to elucidate heme’s binding mode with IRAK1, which does not possess prototypical heme binding domains.63–65 More broadly, we recognize that heme binds proteins in multiple orientations that might occlude capture and identification. Thus, we hypothesize that analogues with varying tag orientations, as well as different heme forms, including biosynthetic precursors and catabolic products, would enable a more complete portrait of heme interactions. Nonetheless, the data sets provided here represent a major expansion of heme-binding proteins, and the chemical proteomics strategy described should facilitate investigations of heme roles in human biology.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the Scripps NMR, MS, and Genetic Perturbation Screening core facilities.

Funding

R.A.H. is supported by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, National Institutes of Health, through Grant Number UL1TR002550 and linked Award TL1TR002551. We thank the National Institutes of Health (R01 AI156268) for research support.

Footnotes

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.2c06104.

Figures S1–S6, experimental methods, and compound characterization (PDF)

Table S1: Complete list of protein targets and proteomic data (XLSX)

Contributor Information

Rick A. Homan, Department of Chemistry, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, California 92037, United States

Appaso M. Jadhav, Department of Chemistry, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, California 92037, United States

Louis P. Conway, Department of Chemistry, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, California 92037, United States

Christopher G. Parker, Department of Chemistry, The Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, California 92037, United States

REFERENCES

- (1).Gilardi G; Di Nardo G Heme iron centers in cytochrome P450: structure and catalytic activity. Rend. Lincei. 2017, 28 (1), 159–167. [Google Scholar]

- (2).Lukin JA; Ho C The Structure–Function Relationship of Hemoglobin in Solution at Atomic Resolution. Chem. Rev. 2004, 104 (3), 1219–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Hou SW; Reynolds MF; Horrigan FT; Heinemann SH; Hoshi T Reversible binding of heme to proteins in cellular signal transduction. Acc. Chem. Res. 2006, 39 (12), 918–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Girvan HM; Munro AW Heme Sensor Proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2013, 288 (19), 13194–13203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Shimizu T; Lengalova A; Martinek V; Martinkova M Heme: emergent roles of heme in signal transduction, functional regulation and as catalytic centres. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48 (24), 5624–5657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Mosure SA; Strutzenberg TS; Shang J; Munoz-Tello P; Solt LA; Griffin PR; Kojetin DJ Structural basis for heme-dependent NCoR binding to the transcriptional repressor REV-ERBβ. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7 (5), eabc6479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Zenke-Kawasaki Y; Dohi Y; Katoh Y; Ikura T; Ikura M; Asahara T; Tokunaga F; Iwai K; Igarashi K Heme Induces Ubiquitination and Degradation of the Transcription Factor Bach1. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007, 27 (19), 6962–6971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Yin L; Wu N; Curtin JC; Qatanani M; Szwergold NR; Reid RA; Waitt GM; Parks DJ; Pearce KH; Wisely GB; et al. Rev-erbalpha, a heme sensor that coordinates metabolic and circadian pathways. Sci. Adv. 2007, 318 (5857), 1786–1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Lavrovsky Y; Chatterjee B; Clark RA; Roy AK Role of redox-regulated transcription factors in inflammation, aging and age-related diseases. Exp. Gerontol. 2000, 35 (5), 521–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Freeman SL; Kwon H; Portolano N; Parkin G; Girija UV; Basran J; Fielding AJ; Fairall L; Svistunenko DA; Moody PCE; et al. Heme binding to human CLOCK affects interactions with the E-box. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2019, 116 (40), 19911–19916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Shen J; Sheng X; Chang Z; Wu Q; Wang S; Xuan Z; Li D; Wu Y; Shang Y; Kong X; et al. Iron metabolism regulates p53 signaling through direct heme-p53 interaction and modulation of p53 localization, stability, and function. Cell Rep. 2014, 7 (1), 180–193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Burton MJ; Kapetanaki SM; Chernova T; Jamieson AG; Dorlet P; Santolini J; Moody PCE; Mitcheson JS; Davies NW; Schmid R; et al. A heme-binding domain controls regulation of ATP-dependent potassium channels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2016, 113 (14), 3785–3790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Guarda CCD; Santiago RP; Fiuza LM; Aleluia MM; Ferreira JRD; Figueiredo CVB; Yahouedehou S; Oliveira RM; Lyra IM; Goncalves MS Heme-mediated cell activation: the inflammatory puzzle of sickle cell anemia. Expert. Rev. Hematol. 2017, 10 (6), 533–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Soares MP; Bozza MT Red alert: labile heme is an alarmin. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2016, 38, 94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Boon EM; Marletta MA Ligand discrimination in soluble guanylate cyclase and the H-NOX family of heme sensor proteins. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2005, 9 (5), 441–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Boon EM; Huang SH; Marletta MA A molecular basis for NO selectivity in soluble guanylate cyclase. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2005, 1, 53–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Galmozzi A; Kok BP; Kim AS; Montenegro-Burke JR; Lee JY; Spreafico R; Mosure S; Albert V; Cintron-Colon R; Godio C; et al. PGRMC2 is an intracellular haem chaperone critical for adipocyte function. Nature 2019, 576 (7785), 138–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Chen J-J; London IM Hemin enhances the differentiation of mouse 3T3 cells to adipocytes. Cell 1981, 26 (1), 117–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Fernandez PL; Dutra FF; Alves L; Figueiredo RT; Mourão-Sa D; Fortes GB; Bergstrand S; Lönn D; Cevallos RR; Pereira RMS; et al. Heme amplifies the innate immune response to microbial molecules through spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk)-dependent reactive oxygen species generation. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285 (43), 32844–32851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Dutra FF; Bozza MT Heme on innate immunity and inflammation. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 5, 115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Yanatori I; Tabuchi M; Kawai Y; Yasui Y; Akagi R; Kishi F Heme and non-heme iron transporters in non-polarized and polarized cells. BMC Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Hanna DA; Martinez-Guzman O; Reddi AR Heme Gazing: Illuminating Eukaryotic Heme Trafficking, Dynamics, and Signaling with Fluorescent Heme Sensors. Biochem. 2017, 56 (13), 1815–1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Leung GC-H; Fung SS-P; Gallio AE; Blore R; Alibhai D; Raven EL; Hudson AJ Unravelling the mechanisms controlling heme supply and demand. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2021, 118 (22), e2104008118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Gallio AE; Fung SSP; Cammack-Najera A; Hudson AJ; Raven EL Understanding the Logistics for the Distribution of Heme in Cells. JACS Au 2021, 1 (10), 1541–1555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Asher WB; Bren KL A heme fusion tag for protein affinity purification and quantification. Protein Sci. 2010, 19 (10), 1830–1839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Bozinovic N; Noé R; Kanyavuz A; Lecerf M; Dimitrov JD Method for identification of heme-binding proteins and quantification of their interactions. Anal. Biochem. 2020, 607, 113865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Mukherjee S; Sengupta K; Das MR; Jana SS; Dey A Site-specific covalent attachment of heme proteins on self-assembled monolayers. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2012, 17 (7), 1009–1023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Li X; Wang X; Zhao K; Zhou Z; Zhao C; Yan R; Lin L; Lei T; Yin J; Wang R; et al. A Novel Approach for Identifying the Heme-Binding Proteins from Mouse Tissues. Genom. Proteom. Bioinform. 2003, 1 (1), 78–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Tsolaki V-DC; Georgiou-Siafis SK; Tsamadou AI; Tsiftsoglou SA; Samiotaki M; Panayotou G; Tsiftsoglou AS Hemin accumulation and identification of a heme-binding protein clan in K562 cells by proteomic and computational analysis. J. Cell. Physiol. 2022, 237 (2), 1315–1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Liou Y-F; Charoenkwan P; Srinivasulu YS; Vasylenko T; Lai S-C; Lee H-C; Chen Y-H; Huang H-L; Ho S-Y SCMHBP: prediction and analysis of heme binding proteins using propensity scores of dipeptides. BMC Bioinform. 2014, 15, S4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Parker CG; Pratt MR Click Chemistry in Proteomic Investigations. Cell 2020, 180 (4), 605–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Qin W; Yang F; Wang C Chemoproteomic profiling of protein–metabolite interactions. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2020, 54, 28–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Wilkinson IVL; Pfanzelt M; Sieber SA Functionalised Cofactor Mimics for Interactome Discovery and Beyond. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 61 (29), e202201136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Conway LP; Jadhav AM; Homan RA; Li W; Rubiano JS; Hawkins R; Lawrence RM; Parker CG Evaluation of fully-functionalized diazirine tags for chemical proteomic applications. Chem. Sci. 2021, 12 (22), 7839–7847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Rostovtsev VV; Green LG; Fokin VV; Sharpless KB A Stepwise Huisgen Cycloaddition Process: Copper(I)-Catalyzed Regioselective “Ligation” of Azides and Terminal Alkynes. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2002, 41 (14), 2596–2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (36).Fufezan C; Zhang J; Gunner MR Ligand preference and orientation in b- and c-type heme-binding proteins. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Genet. 2008, 73 (3), 690–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (37).Smith LJ; Kahraman A; Thornton JM Heme proteins—Diversity in structural characteristics, function, and folding. Proteins: Struct. Funct. Genet. 2010, 78 (10), 2349–2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (38).Parker CG; Galmozzi A; Wang Y; Correia BE; Sasaki K; Joslyn CM; Kim AS; Cavallaro CL; Lawrence RM; Johnson SR; et al. Ligand and Target Discovery by Fragment-Based Screening in Human Cells. Cell 2017, 168 (3), 527–541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (39).Jacob Blackmon B; Dailey TA; Lianchun X; Dailey HA Characterization of a human and mouse tetrapyrrole-binding protein. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2002, 407 (2), 196–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (40).Ishikawa K; Takeuchi N; Takahashi S; Matera KM; Sato M; Shibahara S; Rousseau DL; Ikeda-Saito M; Yoshida T Heme oxygenase-2. Properties of the heme complex of the purified tryptic fragment of recombinant human heme oxygenase-2. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270 (11), 6345–6350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (41).Piel RB 3rd; Shiferaw MT; Vashisht AA; Marcero JR; Praissman JL; Phillips JD; Wohlschlegel JA; Medlock AE A Novel Role for Progesterone Receptor Membrane Component 1 (PGRMC1): A Partner and Regulator of Ferrochelatase. Biochem. 2016, 55 (37), 5204–5217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (42).Thompson A; Schäfer J; Kuhn K; Kienle S; Schwarz J; Schmidt G; Neumann T; Hamon C Tandem Mass Tags: A Novel Quantification Strategy for Comparative Analysis of Complex Protein Mixtures by MS/MS. Anal. Chem. 2003, 75 (8), 1895–1904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (43).Maryanovich M; Zaltsman Y; Ruggiero A; Goldman A; Shachnai L; Zaidman SL; Porat Z; Golan K; Lapidot T; Gross A An MTCH2 pathway repressing mitochondria metabolism regulates haematopoietic stem cell fate. Nat. Commun. 2015, 6, 7901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (44).Stewart CR; Stuart LM; Wilkinson K; van Gils JM; Deng J; Halle A; Rayner KJ; Boyer L; Zhong R; Frazier WA; et al. CD36 ligands promote sterile inflammation through assembly of a Toll-like receptor 4 and 6 heterodimer. Nat. Immunol. 2010, 11 (2), 155–161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (45).Silverstein RL; Febbraio M CD36, a Scavenger Receptor Involved in Immunity, Metabolism, Angiogenesis, and Behavior. Sci. Signal. 2009, 2 (72), re3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (46).Lin J-C; Hsu M; Tarn W-Y Cell stress modulates the function of splicing regulatory protein RBM4 in translation control. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2007, 104 (7), 2235–2240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (47).Weber P; Flores RE; Kiefer MF; Schupp M Retinol Saturase: More than the Name Suggests. Trends. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 41 (6), 418–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (48).Cao Z; Henzel WJ; Gao X IRAK: a kinase associated with the interleukin-1 receptor. Sci. Adv. 1996, 271 (5252), 1128–1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (49).Dérijard B; Raingeaud J; Barrett T; Wu IH; Han J; Ulevitch RJ; Davis RJ Independent human MAP-kinase signal transduction pathways defined by MEK and MKK isoforms. Sci. Adv. 1995, 267 (5198), 682–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (50).Braeutigam C; Rago L; Rolke A; Waldmeier L; Christofori G; Winter J The RNA-binding protein Rbfox2: an essential regulator of EMT-driven alternative splicing and a mediator of cellular invasion. Oncogene 2014, 33 (9), 1082–1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (51).Gellett AM; Kharel Y; Sunkara M; Morris AJ; Lynch KR Biosynthesis of alkyl lysophosphatidic acid by diacylglycerol kinases. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012, 422 (4), 758–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (52).Epand RM; Kam A; Bridgelal N; Saiga A; Topham MK The α Isoform of Diacylglycerol Kinase Exhibits Arachidonoyl Specificity with Alkylacylglycerol. Biochem. 2004, 43 (46), 14778–14783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (53).Wesche H; Henzel WJ; Shillinglaw W; Li S; Cao Z MyD88: an adapter that recruits IRAK to the IL-1 receptor complex. Immunity 1997, 7 (6), 837–847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (54).Liu PH; Sidi S Targeting the Innate Immune Kinase IRAK1 in Radioresistant Cancer: Double-Edged Sword or One-Two Punch? Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (55).Kollewe C; Mackensen A-C; Neumann D; Knop J; Cao P; Li S; Wesche H; Martin MU Sequential Autophosphorylation Steps in the Interleukin-1 Receptor-associated Kinase-1 Regulate its Availability as an Adapter in Interleukin-1 Signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279 (7), 5227–5236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (56).Bozza MT; Jeney V Pro-inflammatory Actions of Heme and Other Hemoglobin-Derived DAMPs. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (57).Janciauskiene S; Vijayan V; Immenschuh S TLR4 Signaling by Heme and the Role of Heme-Binding Blood Proteins. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (58).Smith LJ; Kahraman A; Thornton JM Heme proteins–diversity in structural characteristics, function, and folding. Proteins 2010, 78 (10), 2349–2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (59).Chen J-J; London IM Regulation of protein synthesis by heme-regulated eIF-2α kinase. Trends. Biochem. Sci. 1995, 20 (3), 105–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (60).Igarashi J; Murase M; Iizuka A; Pichierri F; Martinkova M; Shimizu T Elucidation of the Heme Binding Site of Heme-regulated Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 2α Kinase and the Role of the Regulatory Motif in Heme Sensing by Spectroscopic and Catalytic Studies of Mutant Proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 2008, 283 (27), 18782–18791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (61).Segel IH Enzyme Kinetics: Behavior and Analysis of Rapid Equilibrium and Steady-State Enzyme Systems; Wiley, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- (62).Belcher JD; Chen C; Nguyen J; Milbauer L; Abdulla F; Alayash AI; Smith A; Nath KA; Hebbel RP; Vercellotti GM Heme triggers TLR4 signaling leading to endothelial cell activation and vaso-occlusion in murine sickle cell disease. Blood 2014, 123 (3), 377–390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (63).Scarneo SA; Hughes PF; Yang KW; Carlson DA; Gurbani D; Westover KD; Haystead TAJ A highly selective inhibitor of interleukin-1 receptor–associated kinases 1/4 (IRAK-1/4) delineates the distinct signaling roles of IRAK-1/4 and the TAK1 kinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295 (6), 1565–1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (64).Wang L; Qiao Q; Ferrao R; Shen C; Hatcher JM; Buhrlage SJ; Gray NS; Wu H Crystal structure of human IRAK1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2017, 114 (51), 13507–13512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (65).Flannery S; Bowie AG The interleukin-1 receptor-associated kinases: Critical regulators of innate immune signalling. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2010, 80 (12), 1981–1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.