Abstract

Inosine monophosphate (IMP) is the intracellular precursor for both adenosine monophosphate and guanosine monophosphate and thus plays a central role in intracellular purine metabolism. IMP can also serve as an extracellular signaling molecule, and can regulate diverse processes such as taste sensation, neutrophil function, and ischemia-reperfusion injury. How IMP regulates inflammation induced by bacterial products or bacteria is unknown. In this study, we demonstrate that IMP suppressed TNF-α production and augmented IL-10 production in endotoxemic mice. IMP exerted its effects through metabolism to inosine, as IMP only suppressed TNF-α following its CD73-mediated degradation to inosine in lipopolysaccharide-activated macrophages. Studies with gene targeted mice and pharmacological antagonism indicated that A2A, A2B and A3 adenosine receptors are not required for the inosine suppression of TNF-α production. The inosine suppression of TNF-α production did not require its metabolism to hypoxanthine through purine nucleoside phosphorylase or its uptake into cells through concentrative nucleoside transporters indicating a role for alternative metabolic/uptake pathways. Inosine augmented IL-β production by macrophages in which inflammasome was activated by lipopolysaccharide and ATP. In contrast to its effects in endotoxemia, IMP failed to affect the inflammatory response to abdominal sepsis and pneumonia. We conclude that extracellular IMP and inosine differentially regulate the inflammatory response.

Keywords: inosine 5′-monophosphate, inosine, endotoxemia, sepsis

Introduction

Inosine 5′-monophosphate (IMP) occupies a central position in purine biosynthesis, as it is the precursor of both adenosine 5′-monophosphate (AMP) and guanosine 5′-monophosphate (GMP) in cells (1, 2). IMP is the first compound in the purine synthetic pathway to have a completely formed purine ring system. IMP can be synthesized in two distinct pathways (1, 2). First, IMP is synthesized de novo, beginning with simple starting materials such as amino acids and bicarbonate. Alternatively, purine bases, such as hypoxanthine or adenine, released by the hydrolytic degradation of nucleic acids and nucleotides, can be salvaged and recycled into IMP in the so-called salvage pathway. The pathway leading from IMP to AMP involves adenylosuccinate synthetase and adenylosuccinate lyase. IMP dehydrogenase (IMPDH) is a vital enzyme involved in the de novo synthesis of guanine nucleotides. IMPDH catalyzes a crucial step of converting IMP into xanthosine monophosphate (XMP) that is further converted into GMP.

Purine catabolic pathways can also increase intracellular IMP levels. Adenosine monophosphate deaminase catalyzes the deamination of AMP to IMP (3). Inosine triphosphate pyrophosphatase hydrolyzes inosine 5′-triphosphate to IMP and pyrophosphate (4). IMP can itself be catabolized to inosine by 5’-nucleotidase intracellularly (5) and CD73 and other phosphatases in the extracellular space (6–9).

While the intracellular role of IMP as a central hub in purine metabolism is well appreciated, the role of IMP in extracellular signaling remains less well understood. IMP has long been known to potentiate umami taste intensity, an effect that is mediated through metabotropic glutamate receptors (10) and the G protein-coupled receptor T1R1 (11). Outside tasting, the role of IMP in extracellular signaling is even less well defined. Administration of IMP in vivo suppressed the appearance of clinical signs of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis, an effect that was associated with increased levels of the IMP/inosine downstream metabolite uric acid, prompting the authors to speculate that uric acid mediated the anti-inflammatory effects of IMP in their model (12). Serhan and coworkers demonstrated that IMP down-regulates neutrophil recruitment in hindlimb reperfusion injury and that IMP binds specifically with high affinity (Kd of ~250 nM) to neutrophils indicating a receptor-mediated effect (13, 14). IMP also prevents neutrophil-mediated reperfusion injury in the lung (15). Thus, while the effects of IMP on neutrophil-mediated inflammation are partially understood, the role of IMP in regulating macrophage-mediated inflammation have not been elucidated. Here, we evaluated the effect of IMP in macrophage-mediated inflammation in vivo and in vitro.

Materials and methods

Mice

Experimentation on mice was approved by the Columbia University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) and was executed according to protocols AAAU6470 and AABL5575. Male C57BL/6 mice (10–12 weeks old) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA). Animals were housed up to five mice per cage in rooms with a 12h light–dark cycle under nonspecific pathogen–free conditions. A2AAR−/− and A2BAR−/− mice (C57BL/6J background) were bred and maintained in a specific pathogen-free Charles River animal facility (Wilmington, MA, USA). All mice were housed for at least 1 week before experimental use at the animal facility at Columbia University and had access to regular chow and water ad libitum. Adult age-matched male mice were used for all experiments.

Reagents and drugs

LPS (from Escherichia coli, serotype 055:B5), inosine, IMP, hypoxanthine, thioglycolate medium, thiazolyl blue tetrazolium bromide (MTT) were purchased from Millipore-Sigma (St Louis, MO, USA). DMEM, PBS, FBS, T-PER buffer, Pierce Protein Assay Kit and penicillin-streptomycin were obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Waltham, MA, USA). Macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF) was purchased from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ, USA). For cytokine measurements ELISA duo sets were purchased from R&D systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA).

In vivo endotoxemia

In the in vivo endotoxemic studies, mice received an initial intraperitoneal (IP) injection of 1000 mg/kg of body weight IMP or vehicle (physiologic saline) followed by an IP injection of 10 mg/kg of body weight LPS (from Escherichia coli, serotype 055:B5) 30 minutes later. Lung, liver, and spleen samples were collected 90 minutes after the LPS injection and were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Samples were stored at −80 oC until RNA or protein extraction. Blood was collected at 90 minutes after LPS in ice-cold Eppendorf tubes containing EDTA and centrifuged for 10 min at 3500 rpm at 4 °C. The plasma was collected and stored at −20 °C until assayed. Cytokines from the plasma were detected with ELISA as described below.

Pneumonia

10–12-week-old male mice were injected intraperitoneally with either 1000 mg/kg IMP or vehicle (physiologic saline) 1 h before inducing pneumonia. Subsequently, the mice were anesthetized by briefly placing them into an isoflurane chamber (2%, 1 L/min) followed by IP ketamine and xylazine injection (100 mg/kg and 10 mg/kg, respectively). Adequate depth of anesthesia was checked by hind toe pinch reflex. Streptococcus pneumoniae (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA; catalogue number: 6303) and Escherichia coli (ATCC; catalogue number: 10798) bacteria were administered at 1010 CFU at a 1:1 ratio in 40 ul PBS with 20–20 ul in each nostril. At the 6-h time point bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) was performed using 1 ml of PBS. Blood was collected by heart puncture and samples were spun down at 3500 rpm (4 °C) for 10 min. Samples were stored at −20 °C until further analysis.

Cecal ligation and puncture

10–12-week-old male mice were injected IP with either IMP or vehicle (physiologic saline) 1 h before inducing sepsis. Polymicrobial sepsis was induced by subjecting mice to cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) (16–21). Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane (2%, 1 L/min) and the depth of anesthesia was checked by hind toe pinch reflex. Under aseptic conditions, a 2-cm midline laparotomy was performed to allow exposure of the cecum. Approximately two-thirds of the cecum was ligated with a 3–0 silk suture, and the ligated part of the cecum was perforated twice (through and through) with a 21-gauge needle (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). The ligated cecum was gently squeezed to extrude a small amount of feces through the perforation site and was then returned to the peritoneal cavity, and the laparotomy was closed. After the operation, all mice were resuscitated with physiologic saline (1 ml injected subcutaneously) and returned to their cages, where they were provided free access to food and water. The mice were re-anesthetized with isoflurane 16 h after the CLP procedure, and blood, peritoneal lavage fluid, and various organs were harvested.

Preparation and treatment of peritoneal- and bone marrow macrophages

Mice were injected intraperitoneally with 3 ml of 4% thioglycolate and peritoneal cells were harvested 3–4 days later. The cells were plated on 96-well cell culture plates at 200,000 cells/well and incubated in DMEM for 3 h at 37 °C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Non-adherent cells were removed by rinsing the plates three times with cold PBS. Bone marrow from hind limbs was flushed with PBS using a 26-gauge needle, and the resultant cell suspension was passed through a 70-mm nylon mesh cell strainer. The cells were then cultured in DMEM containing 50 ng/mL recombinant M-CSF for 7 days, with a change of culture medium at day 3. Afterwards, bone marrow derived macrophages (BMDMs) were scraped in cold PBS and plated for in vitro treatment. Cells were treated with various concentrations of inosine, hypoxanthine, or IMP 30 min before the addition of 10 μg/ml LPS for either 4 or 24 h and supernatants for cytokine measurements were collected. For IL-1β release cells were treated with 5 mM ATP 20–30 minutes before supernatant collection. Cytokine levels were determined by ELISA as described below.

Cytokine assays

Tissue was lysed by homogenization in T-PER buffer. Cytokine concentrations in plasma, tissue lysates and supernatants were determined by ELISA kits that are specific against murine cytokines. Levels of tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, interleukin (IL)-1β, IL-6, IL-10 and macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-2 were measured using ELISA kits. Plates were read at 450 nm with a reference measurement at 540 nm by a Spectramax 190 microplate reader from Molecular Devices (Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

RNA isolation and RNASeq

Frozen liver samples were submitted to Columbia Molecular Pathology/MPSR (HICCC) core where they were homogenized with Qiagen TissueLyser II (Qiagen, Germantown, MD, USA), at 25/s oscillation frequency for 2 min. RNA was extracted with Qiagen miRNeasy mini kit following the instructions of the manufacturer, and RNA was eluted at a volume of 50 ul. RNA samples with RIN 8≤ were submitted to the JP Sulzberger Columbia Genome Center for RNAseq analysis. Poly-A pull-down was used to enrich mRNAs from total RNA samples, followed by library construction using Illumina TruSeq chemistry (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA). Libraries were sequenced using Illumina NovaSeq 6000. Samples were multiplexed in each lane, yielding a targeted number of paired end 100-bp reads for each sample. Real-Time Analysis software (Illumina) was used for base calling and bcl2fastq2 (version 2.19) was used for converting BCL to fastq format, coupled with adaptor trimming. Pseudoalignment was performed to a kallisto index created from transcriptomes (Human: GRCh38; Mouse: GRCm38) using kallisto (0.44.0). Testing for differentially expressed genes under various conditions was done using DESeq2 R package designed to test differential expression between two experimental groups from RNAseq counts data.

Data Availability

Transcriptome data will be deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database and will be accessible through GEO Series accession number: GSE183880(transcriptome data upload is in progress.)

Statistical analysis

Values in the figures and text are expressed as mean ± standard error of means (SEM) of n observations. Statistical analysis comparing 2 groups was performed by 2-tailed unpaired student t test. When comparing 3 or more groups, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used, followed by Dunnett’s test. For RNAseq data processing DESeq2 differentially expressed gene analysis was applied. log2 fold change values were determined, standard error (lfcSE) was calculated, and Wald statistics was applied to determine p values. Data shown depict Benjamini-Hochberg adjusted p values (padj). Volcano plot depicts false discovery rate (FDR) corrected p values. GraphPad Prism 8.0.2 was used for data illustration. Results were considered statistically different when p was ≤ 0.05.

Results

IMP suppresses TNF-α and augments IL-10 levels in endotoxemic mice

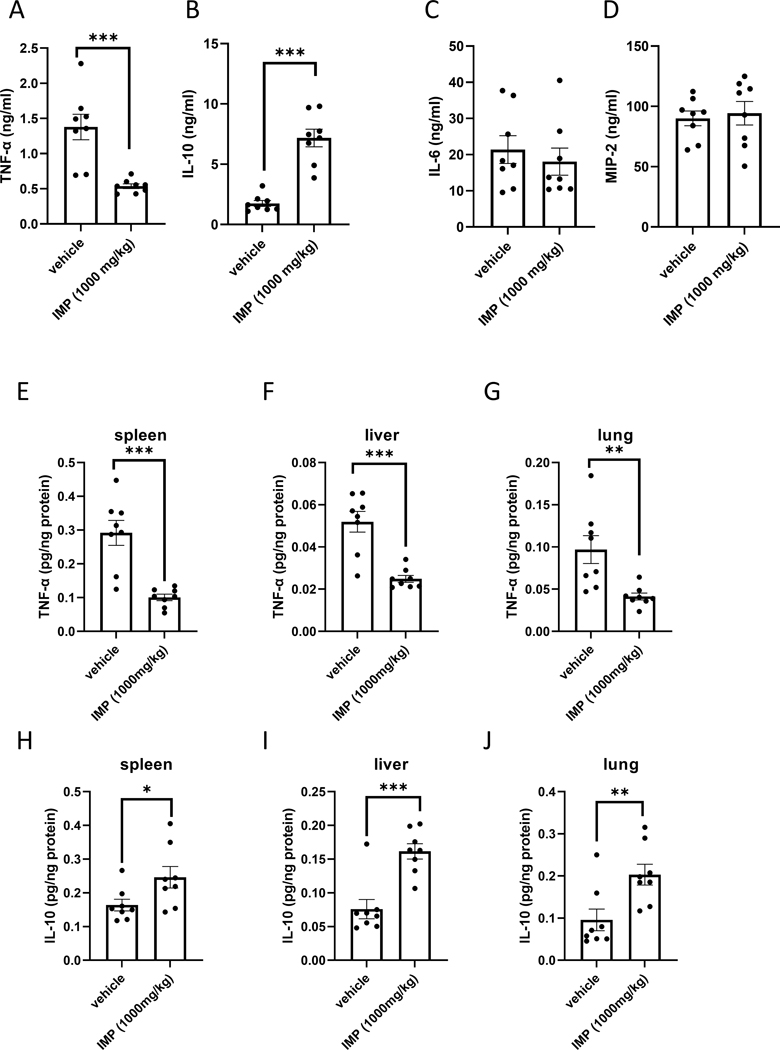

We first assessed the effect of IMP on macrophage-derived cytokine levels in mice intraperitoneally injected with LPS (10 mg/kg). Pretreating the mice with IMP (1000 mg/kg, (22)) 30 min before LPS administration suppressed plasma TNF-α levels (Fig. 1A) and augmented plasma IL-10 concentrations (Fig. 1 B). Plasma levels of IL-6 or MIP-2 were not altered by IMP (Fig. 1 C and D). We then evaluated the effect of IMP on intra-organ levels of TNF-α and IL-10. Similar to its effect in the plasma, IMP suppressed TNF-α levels in spleen, liver and lung (Fig. 1 E–G) and augmented IL-10 levels in all three organs (Fig. 1 H–J). Taken together, IMP selectively and differentially alters the production of cytokines in vivo.

Figure 1. IMP differentially regulates cytokines in murine endotoxemia.

IMP suppresses TNF-α (A) and augments IL-10 (B) in endotoxemia, while IL-6 and MIP-2 levels remain unaffected (C and D) as evidenced by plasma cytokine measurements. IMP also downregulates TNF-α in organs during endotoxemia, as measured in spleen (E), liver (F) and lung (G) tissue lysates, whereas IL-10 levels are elevated in the same organs (H-J). Values in the figures are expressed as mean ± SEM and are representative of 3 experiments (n = 8 mice/group). *p ≤0.05, **p ≤0.01, ***p ≤0.001

IMP fundamentally alters gene expression in the liver

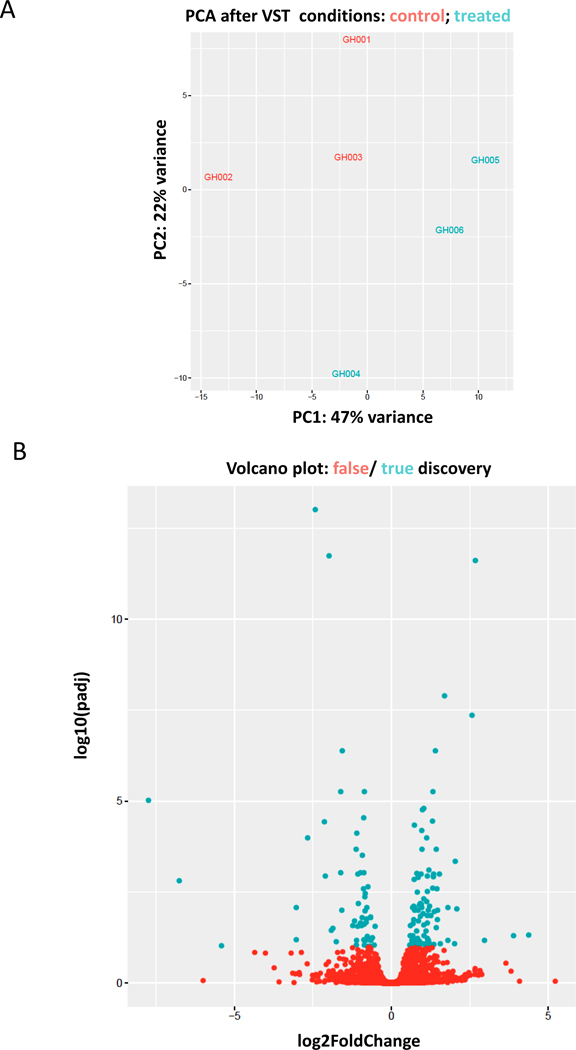

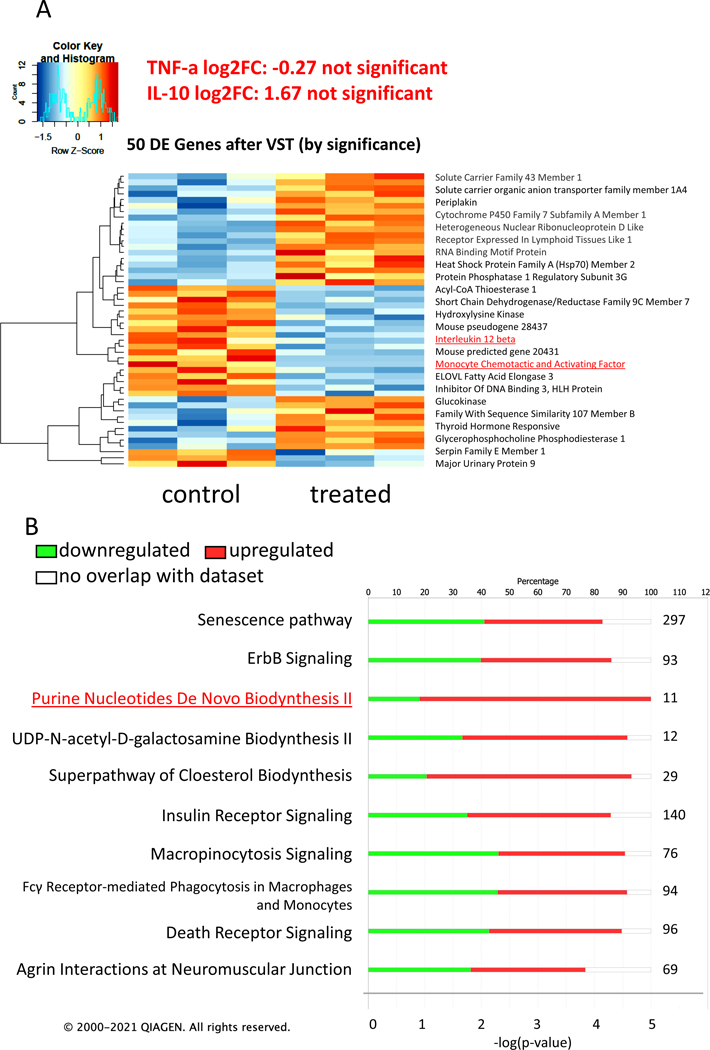

To assess how IMP affects inflammatory cell activation globally in vivo, we subjected liver, the organ containing the highest numbers of macrophages in the body, to RNAseq analyses. High quality RNA was isolated from the livers of 3 vehicle- and 3 IMP-treated mice and submitted for RNAseq analysis. Principal component analysis (PCA) of total transcriptomes from each sample, revealed a clear segregation of vehicle vs. IMP-treated samples (Fig. 2A). Our analysis identified 105 genes that were differentially expressed, determined by adjusted p values (42 downregulated, 63 upregulated; padj ≤ 0.05), between the two treatment groups, as illustrated in the volcano plot (Fig. 2B). The top 50 differentially regulated genes were assembled into a heatmap (Fig. 3A). TNF-α and IL-10 did not come up in the list of genes whose expression was significantly changed. However, IL-12 subunit beta was downregulated in the IMP-treated group. This cytokine is expressed by activated macrophages and acts on T and natural killer cells (23), and its downregulation confirms that IMP has anti-inflammatory effects in endotoxemia. The expression of monocyte chemotactic and activating factor (MCAF/MCP-1), a known chemoattractant of inflammatory cells, was also downregulated in the IMP treated group, further supporting an anti-inflammatory role of IMP. The most affected signaling pathways were identified by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (Qiagen IPA software) and are listed starting with the highest p value (Fig. 3 B). Notably, 9 molecules of the Purine Nucleotides De Novo Biosynthesis II pathway were upregulated in the IMP treated group. Out of these molecules, the upregulation of IMP dehydrogenase is very intriguing. In the de novo purine synthesis pathway IMP dehydrogenase oxidizes IMP at C-2 resulting in xanthosine monophosphate, which can be further metabolized into GMP (1, 2). This change in gene expression indicates that IMP is able to regulate its own metabolism.

Figure 2. Effect on IMP on gene expression in endotoxemic liver.

Principal component analysis (PCA) reveals a clear segregation of vehicle (red) vs. IMP-treated (blue) endotoxemic liver samples (A). Volcano plot depicts 105 genes (blue) that were identified to be differentially expressed, determined by adjusted p values (padj ≤ 0.05) between the two treatment groups (B).

Figure 3. Effect of IMP on key gene expression and pathways.

The top 50 differentially regulated genes are assembled into a heatmap by variance-stabilizing transformation (VST). The left side represents the vehicle-treated control group, the right side represent the IMP-treated group. The group sample number is 3 in each (A). Stacked bar chart displays the percentage of genes that were upregulated (red), downregulated (green), and genes not overlapping with our data set (white) in IPA biological function analysis (B). Pathways were considered significant based on the Fisher’s exact test with a −log 10 p value > 1.3 (corresponds to a p value < 0.05). The numerical value next to each bar represents the number of differentially expressed molecules that are involved in the biological function category. The X axis on the bottom shows the significance (-log (p value)).

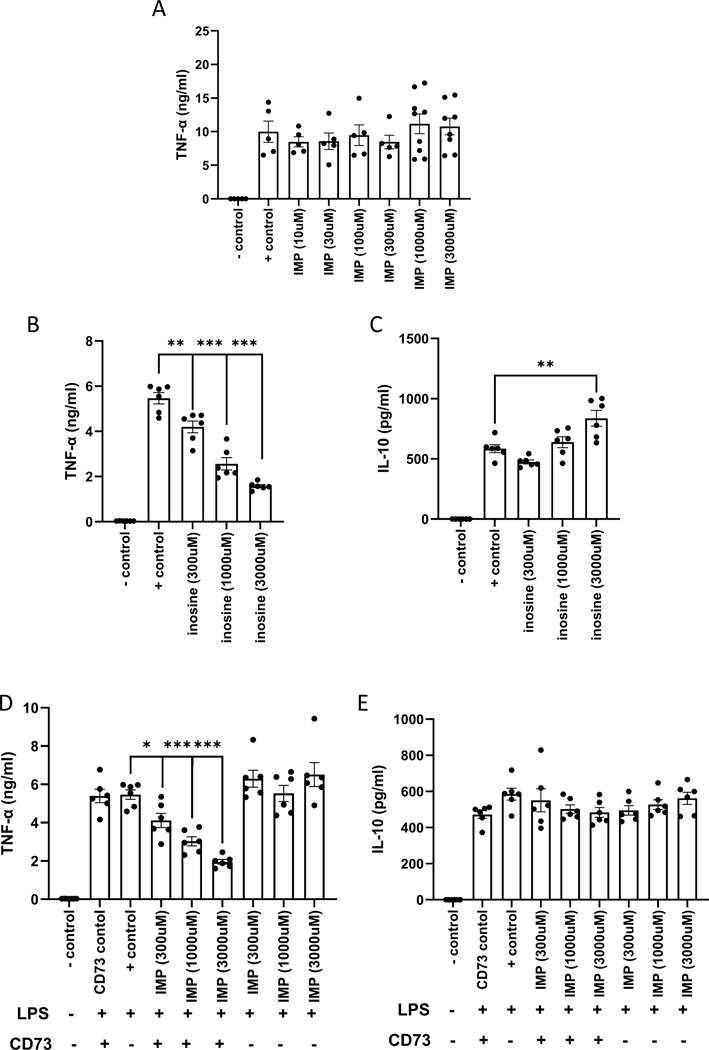

IMP metabolite inosine is the effector of IMP in vitro

To identify the underlying mechanism of the in vivo effect of IMP, we employed a reductionist approach utilizing primary peritoneal macrophage (PM) cell culture. PMs were harvested from C57BL/6J wild type mice and treated with increasing concentrations of IMP 30 minutes before LPS treatment. As opposed to the in vivo results, IMP did not alter the production of TNF-α (Fig. 4A), whereas IL-10 levels did not reach the limit of detection (data not shown) measured 16–24 h after LPS administration. Next, we used inosine, the metabolic product of IMP, to test if IMP needs to be degraded to inosine to be effective. Inosine decreased TNF-α production in a concentration dependent manner (Fig. 4B), while IL-10 levels only increased with the highest concentration of inosine (Fig. 4C). When CD73, an ecto-5′-nucleotidase known to cleave IMP to inosine, was added 5 minutes before IMP, TNF-α levels were suppressed, but IL-10 levels were unchanged (Fig. 4 D and E). These in vitro results suggest that IMP degradation to inosine is responsible for the IMP suppression of TNF-α production.

Figure 4. Inosine mediates the effects of IMP in vitro.

IMP fails to influence TNF-α production in PMs in vitro (A), however inosine suppresses TNF-α levels in a concentration dependent manner as measured by ELISA (B). IL-10 levels are only augmented at the highest dose of inosine (C). IMP in the presence of CD73 suppresses TNF-α production (D) but fails to affect IL-10 production (E). Values in the figures are expressed as mean ± SEM and are representative of 5 experiments (n = 5–6/group). *p ≤0.05, **p ≤0.01, ***p ≤0.001

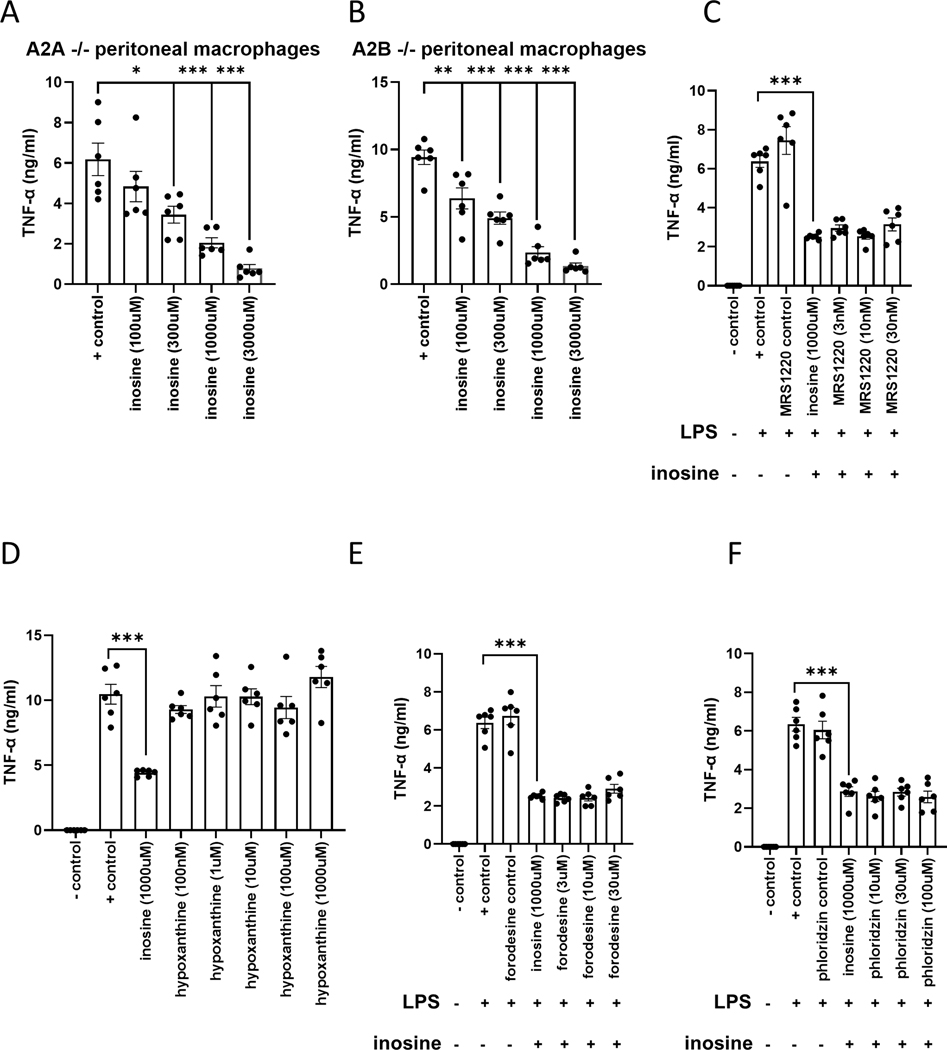

Inosine’s effect is not mediated by A2A, A2B, or A3 adenosine receptors

Adenosine is not the only ligand of adenosine receptors, as they can also bind inosine as well as netrin (24–30). In addition, A2A, A2B, and A3 adenosine receptors suppress TNF-α production by macrophages and are anti-inflammatory (31–37). Thus, we first used PMs isolated from A2AAR−/− and A2BAR−/− mice to test whether inosine suppresses TNF-α through A2A or A2B adenosine receptors. Inosine decreased TNF-α levels in PMs isolated from both A2AAR−/− and A2BAR−/− mice, indicating that the effect of inosine is not mediated through A2A or A2B receptors (Fig. 5 A and B). Next, we used an A3 receptor antagonist MRS 1220 to test whether inosine acts through A3 receptors. PMs isolated from wild type mice were pre-treated with MRS 1220 30 minutes before receiving inosine. The inhibitor failed to prevent the inosine suppression of TNF-α indicating that inosine’s effect is not mediated through A3 receptors (Fig. 5C). Since inosine is metabolized to hypoxanthine by purine nucleoside phosphorylase, we tested the possibility that the inosine suppression of TNF-α was mediate by hypoxanthine. However, hypoxanthine failed suppress TNF-α production (Fig. 5 D). In addition, forodesine, a transition-state analog inhibitor of purine nucleoside phosphorylase failed to affect the ability of inosine to suppress TNF-α levels. These results indicate that hypoxanthine does not mediate the inosine suppression of TNF-α (Fig. 5E). Finally, we tested whether inosine uptake is necessary for inosine to suppress TNF-α production by the macrophages. To investigate this, PMs were pre-treated with phloridzin, a concentrative nucleoside transporter (CNT) inhibitor, 30 minutes before inosine treatment. Phloridzin did not prevent the inosine suppression of TNF-α indicating that the uptake of inosine is not necessary for inosine’s effect (Fig. 5F).

Figure 5. The effect of inosine is not mediated by A2A, A2B or A3 receptors or downstream metabolites.

Inosine suppresses TNF-α production by LPS-stimulated PMs isolated from A2AAR−/− (A) and A2BAR−/− (B) mice. Values in the figures are expressed as mean ± SEM and are representative of 2 experiments (n = 6 mice/genotype). Inosine also suppresses TNF-α production in cells pretreated with the A3 receptor antagonist MRS 1220 (C). The inosine metabolite hypoxanthine fails to suppress TNF-α production (D). Inhibition of inosine catabolism via forodesine fails to alter the inosine suppression of TNF-α production (E). The CNT inhibitor phloridzin fails to prevent the inosine suppression of TNF-α production (F). Values in the figures are expressed as mean ± SEM and are representative of 3 observations. *p ≤0.05, **p ≤0.01, ***p ≤0.001

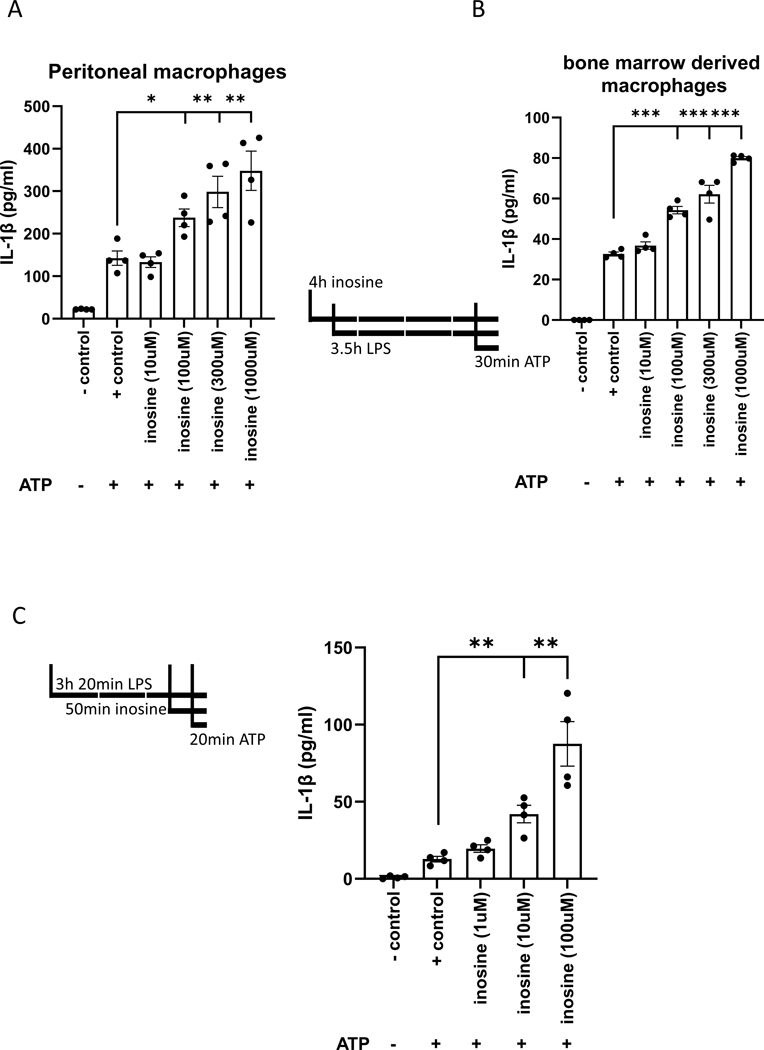

Inosine increases macrophage IL-1β release

Activation of P2X7 receptors following a priming signal such as LPS activates the NLRP3 inflammasome in macrophages, which results in the release of IL-1β. We thus tested the effect of inosine on IL-1β production by macrophages. We first treated PMs with inosine for 30 min prior to priming with LPS for 3 hours, after which the cells were challenged with ATP (5 mM) for 30 min. Inflammasome activation was indicated by IL-1β release into the cell supernatant. Our data demonstrated that inosine increased IL-1β release in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 6A). Next, we repeated the experiment with bone marrow derived macrophages and obtained similar results (Fig. 6B). We then treated the cells with inosine 30 min before the ATP challenge at the 2 and half hour mark of priming with LPS, because we were also interested in how inosine affected inflammasome assembly and activation independent of priming. The ATP challenge lasted 20 min (Fig. 6C). In this case, inosine also increased IL-1β release, indicating that inosine can also augment inflammasome assembly and activation directly. These results indicate that inosine can contribute to inflammatory processes by increasing IL-1β production.

Figure 6. Inosine potentiates IL-1β production in vitro.

IL-1β concentration was measured in the supernatant of inosine treated peritoneal (A) and bone marrow derived macrophages (B). Line drawings depict the treatment schedules. Inosine directly affects purinosome assembly as evidenced by treating the PMs only 2.5 hrs after LPS treatment. Line drawing indicated the altered treatment timeline. Values in the figures are expressed as mean ± SEM and are representative of 4 experiments. *p ≤0.05, **p ≤0.01, ***p ≤0.001

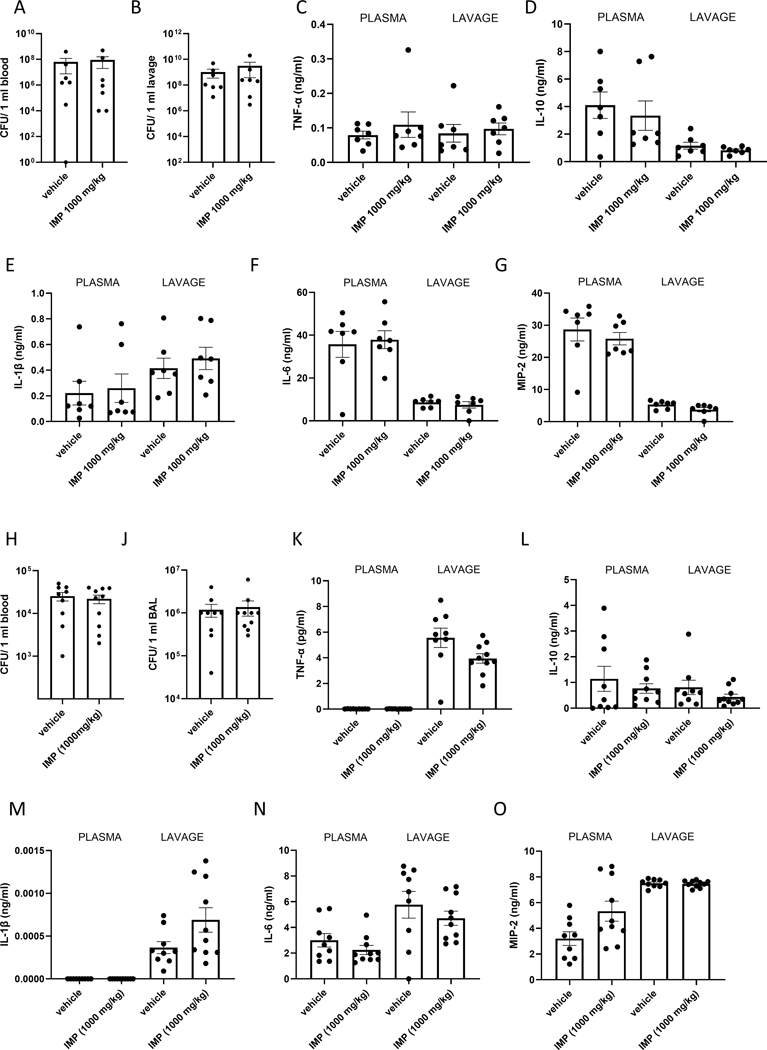

IMP fails to affect inflammation in bacterial infection in vivo

We next tested the effect of IMP on the inflammatory response to infection. First, we used the well-established cecal ligation and puncture model, where we administered IMP (1000 mg/kg; IP) or vehicle prior to the CLP procedure. This model mimics abdominal injury induced polymicrobial sepsis. 16 hours after the induction of sepsis mice were euthanized and peritoneal lavage and blood were collected. We failed to observe any differences in bacterial colony forming units (CFUs) in the lavage and plasma of vehicle- vs. IMP-treated mice (Fig. 7 A and B). Similarly, when we measured the cytokines in the peritoneal lavage and the plasma no differences were found (Fig. 7 C–G) between the two groups.

Figure 7. IMP fails to affect the inflammatory response to CLP induced sepsis or pneumonia.

CFU counts were measured in blood (A) and peritoneal lavage (B) samples collected from septic mice. Cytokines were detected in the plasma and peritoneal lavage of septic mice (C-G). Values in the figures are expressed as mean ± SEM and are representative of 3 experiments (n = 10 mice/group). CFU counts were measured in blood (H) and BAL (J) samples collected from mice with pneumonia. Cytokines were measured from the same mice in the plasma and BAL (K-O). Values in the figures are expressed as mean ± SEM and are representative of 3 experiments (n = 8 mice/group).

Next, we implemented a pneumonia model established in our lab. 1 hour after IMP (1000 mg/kg; IP) or vehicle administration, mice were infected with a mixture of Gram negative and positive bacteria (Streptococcus pneumoniae and Escherichia coli) intranasally. 6 hours after infection bronchoalveolar lavage and blood were collected. Neither CFU (Fig. 7 H and J), nor cytokine levels (Fig. 7 K–O) were different between treatment groups.

Altogether, these results indicate that IMP fails to affect infection-induced inflammation.

Discussion

TNF-α has been the most studied cytokine in experimental models of inflammation. However, there are still many open questions regarding its regulation that remain unanswered. Our results demonstrate that IMP specifically suppresses TNF-α production in murine endotoxemia. Since endotoxin-induced TNF-α in vivo is produced primarily by macrophages (38), we posited that IMP acts on macrophages to suppress TNF-α in vivo. We tested this idea by treating isolated endotoxin-stimulated PMs with IMP and found that IMP failed to suppress TNF-α by these cells. However, converting IMP to inosine using CD73 in vitro recapitulated the in vivo suppressive effect of IMP, indicating that IMP likely reduces TNF-α production following its in vivo degradation to inosine, which we and others had previously shown to be capable of suppressing TNF-α production (27, 39–44). The mechanisms by which inosine exerts its anti-inflammatory effects in macrophages are ill-defined. The fact that adenosine is structurally similar to inosine and our previous results using pharmacological A2A and A2B adenosine receptor antagonists hinted at a role for adenosine receptors in mediating the reducing effect of inosine on TNF-α in macrophages (40). Our current results using macrophages from A2A and A2B adenosine receptor deficient mice have failed to confirm a role for these receptors. In addition, studies with an A3 adenosine receptor antagonist indicate a lack of a role for A3 receptors. Since unlike A2A, A2B and A3 receptors, the only remaining adenosine receptor, the A1 receptor, has not been demonstrated to suppress TNF-α production by macrophages (45–47), it is unlikely that inosine acts on any adenosine receptor. From a potential therapeutic aspect the fact that inosine does not act through adenosine receptors is potentially a plus as adenosine receptor agonists have systemic side effects, most notably hypotension, bradycardia and dyspnea (48).

A2A and A3 receptors appeared to mediate the inosine reduction of TNF-α production in vivo (44). However, the cell types expressing these adenosine receptors were not studied. Thus, it is possible that in the in vivo scenario, inosine does not act directly on macrophages, but instead stimulates adenosine receptors on an intermediary cell type, which then instructs macrophages to decrease their TNF-α production. Mast cells are a good intermediary cell type candidate, as inosine has been shown to induce histamine release from mast cells through A3 receptors (25, 49) and histamine can decrease TNF-α production (50). IMP has also been shown to liberate histamine in vivo (51). It is also possible that adenosine receptors on T cells play a role, as T cells can enhance macrophage TNF-α production through IFN-γ and inosine has been shown to suppress T cell production of IFN-γ through A2A receptors (52, 53). Given that IMP can directly bind a cell surface receptor on neutrophils (13), it is also possible that this hitherto unidentified IMP receptor on neutrophils mediates indirectly the IMP suppression of TNF-α production in vivo. Finally, we cannot exclude the umami receptor T1R1 as a mediator of the in vivo effects of IMP.

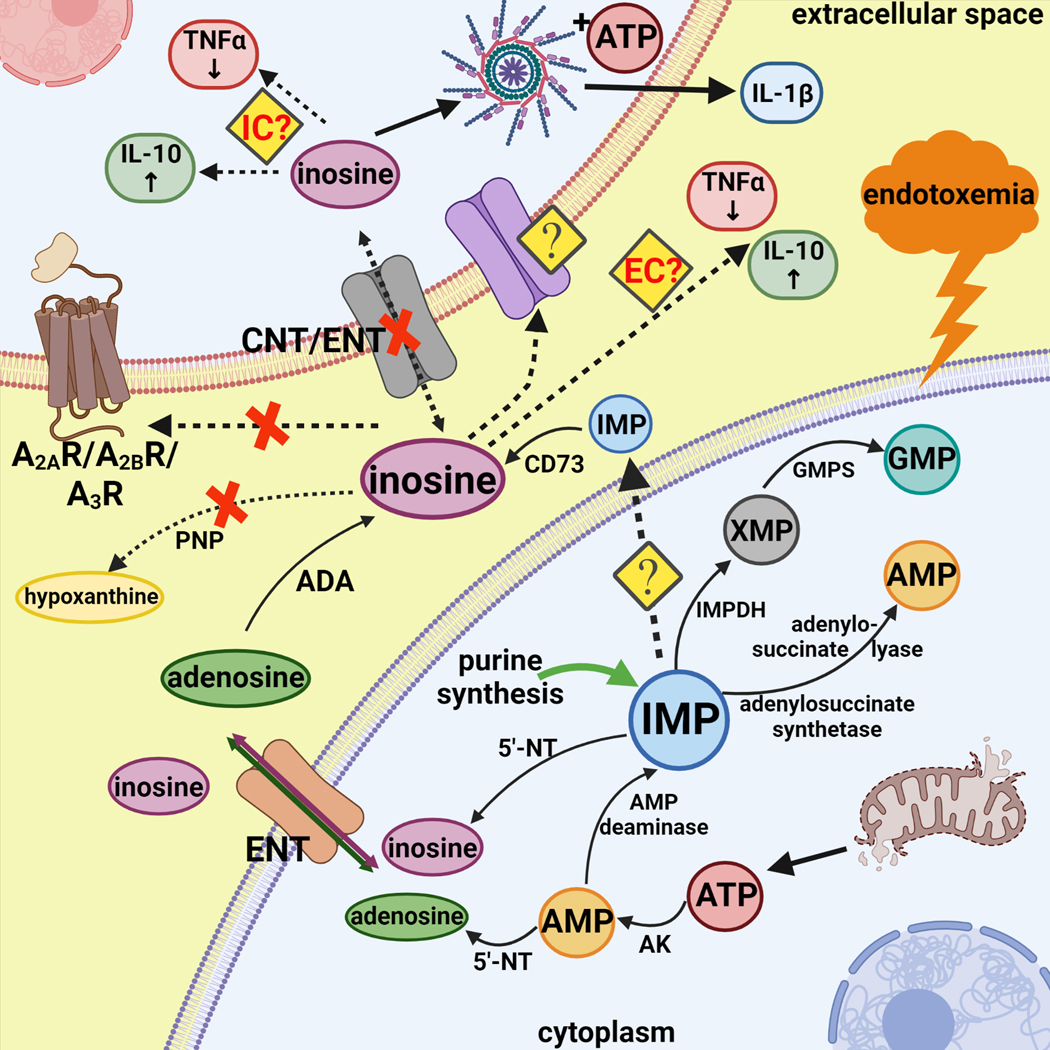

Several other mechanisms for inosine’s mechanism of action can be envisioned and these (as well as purine metabolic pathways) are summarized in Figure 8. It is possible that a so far unidentified cell surface receptor mediates the effects of inosine. Another possibility is that inosine acts after its uptake into the cells by an intracellular mechanism. Our previous study using dipyridamole, an inhibitor of equilibrative nucleoside transporters indicated that even if inosine acts intracellularly, its entry into the cell does not proceed through equilibrative nucleoside transporters. Since macrophages also have functional CNTs (54), we studied the role of these uptake proteins. Phloridzin, a CNT inhibitor (55) failed to prevent the inosine suppression of TNF-α, indicating that inosine uptake in the cells may not be necessary for inosine’s action.

Figure 8.

IMP occupies a central position in purine biosynthesis, as it is the precursor to both AMP and GMP synthesis. Upon endotoxemia injured mitochondria release ATP which is degraded intracellularly to AMP. AMP can be converted to IMP by AMP deaminase or further broken down into adenosine by 5’-NT. While IMP is cleaved by 5`-NT inside the cells, CD73 breaks it down to inosine extracellularly. Adenosine can be also converted into inosine via adenosine deaminase (ADA). Our experimental results indicate that A2AR, A2BR or A3R are not necessary for downstream inosine signaling. Moreover, inosine does not have to be converted to hypoxanthine to alter cytokine production. Previous data using dipyridamole and our current results with phloridzin also exclude inosine uptake via ENTs or CNTs. It is possible that inosine enters the cells through other means, thus decreasing TNF-α and increasing IL-10 production and release. However, it is not yet clear whether inosine modifies cytokine production after its intracellular uptake or while in extracellular space. Furthermore, inosine with the added stimuli of ATP and LPS can activate the inflammasome and induce IL-1β production and release. Abbreviations: 5’-NT: 5’-nucleotidase; AK: adenylate kinase; GMPS: GMP synthase; IMPDH: inosine-5′-monophosphate dehydrogenase; PNP: purine nucleoside phosphorylase

One further possibility was that the effect of inosine was mediated by its degradation product, hypoxanthine. However, since hypoxanthine failed to suppress TNF-α production and inhibiting purine nucleoside phosphorylase, the enzyme that converts inosine into hypoxanthine (56, 57), failed to prevent the suppressive effect of inosine on TNF-α production, we conclude that hypoxanthine does not mediate inosine’s effect.

Although IMP (this study) failed to affect IL-10 production by macrophages in vitro, inosine augmented it, albeit only at high concentrations (data not shown). Further studies will be necessary to determine the mechanisms of the inosine-induced upregulation of IL-10.

While in a previous study we found that inosine ameliorated inflammation and TNF-α production in CLP-induced sepsis (42), IMP failed to affect the host’s inflammatory response to sepsis in the current study. One possibility is that the metabolism of IMP, which is very fast normally (13), is impaired in CLP-induced sepsis. It is also conceivable that IMP binds receptors/molecular targets, which would counter effects caused by inosine. A further issue is the nature of the sepsis model used and the staging of sepsis. That is, potential therapeutic agents need to be tailored to whether sepsis is in the systemic inflammatory response (SIRS) or compensatory anti-inflammatory response stage (CARS) (58). Thus, IMP may have been ineffectual in CLP-induced sepsis because this model can have both inflammatory and anti-inflammatory components whereas endotoxemia, where IMP was protective is dominated by inflammation. Biomarkers helping stage the septic process are still unavailable but there is optimism that genomics/proteomics/metabolomics combined with use of artificial intelligence will aid in the development of useful biomarkers (58).

We also noted for the first time that inosine augmented inflammasome activation in macrophages. This is counterintuitive as all currently available evidence points to inosine being an anti-inflammatory mediator (40, 41, 44, 52). However, another nucleoside, adenosine has previously been shown to be able to augment inflammasome activation, which was mediated by A2A receptors (59).

Extracellular concentrations of both IMP and inosine have been reported to reach at least 100–200 mM (60) and it is possible that these concentrations can increase even further in inflammation, hypoxia, and ischemia (61–68). In fact, a recent study has reported that inosine levels increase in the urine of endotoxemic mice (69). The source of extracellular IMP can potentially be either stressed/dying host cells or the microbiome, as bacteria have been shown to produce IMP (53).

In summary, our results demonstrate that IMP suppresses TNF-α production in endotoxemia, which likely occurs through its degradation to inosine. Since inosine was previously proposed as a new modality for the treatment of inflammatory diseases (44), IMP may be similarly useful.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants R01GM06618916, R01DK11379004 and R01HL158519 awarded to GH. This research was funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support grant P30CA013696 and used the Genomics and High Throughput Screening Shared Resource.

Summary figure was created with BioRender.com.

Footnotes

Disclosures

G.H. owns stock in Purine Pharmaceuticals, Inc. The other authors have no financial conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Pedley AM, and Benkovic SJ (2017) A New View into the Regulation of Purine Metabolism: The Purinosome. Trends Biochem Sci 42, 141–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pareek V, Pedley AM, and Benkovic SJ (2021) Human de novo purine biosynthesis. Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol 56, 1–16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zabielska MA, Borkowski T, Slominska EM, and Smolenski RT (2015) Inhibition of AMP deaminase as therapeutic target in cardiovascular pathology. Pharmacol Rep 67, 682–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simone PD, Pavlov YI, and Borgstahl GEO (2013) ITPA (inosine triphosphate pyrophosphatase): from surveillance of nucleotide pools to human disease and pharmacogenetics. Mutat Res 753, 131–146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bretonnet AS, Jordheim LP, Dumontet C, and Lancelin JM (2005) Regulation and activity of cytosolic 5’-nucleotidase II. A bifunctional allosteric enzyme of the Haloacid Dehalogenase superfamily involved in cellular metabolism. FEBS Lett 579, 3363–3368 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thompson LF, Eltzschig HK, Ibla JC, Van De Wiele CJ, Resta R, Morote-Garcia JC, and Colgan SP (2004) Crucial role for ecto-5’-nucleotidase (CD73) in vascular leakage during hypoxia. J Exp Med 200, 1395–1405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunha RA (2001) Regulation of the ecto-nucleotidase pathway in rat hippocampal nerve terminals. Neurochem Res 26, 979–991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yegutkin GG (2008) Nucleotide- and nucleoside-converting ectoenzymes: Important modulators of purinergic signalling cascade. Biochim Biophys Acta 1783, 673–694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Idzko M, Ferrari D, Riegel AK, and Eltzschig HK (2014) Extracellular nucleotide and nucleoside signaling in vascular and blood disease. Blood 124, 1029–1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pal Choudhuri S, Delay RJ, and Delay ER (2016) Metabotropic glutamate receptors are involved in the detection of IMP and L-amino acids by mouse taste sensory cells. Neuroscience 316, 94–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang F, Klebansky B, Fine RM, Xu H, Pronin A, Liu H, Tachdjian C, and Li X. (2008) Molecular mechanism for the umami taste synergism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105, 20930–20934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scott GS, Spitsin SV, Kean RB, Mikheeva T, Koprowski H, and Hooper DC (2002) Therapeutic intervention in experimental allergic encephalomyelitis by administration of uric acid precursors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99, 16303–16308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qiu FH, Wada K, Stahl GL, and Serhan CN (2000) IMP and AMP deaminase in reperfusion injury down-regulates neutrophil recruitment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 97, 4267–4272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wada K, Qiu FH, Stahl GL, and Serhan CN (2001) Inosine monophosphate and aspirin-triggered 15-epi-lipoxin A4 act in concert to regulate neutrophil trafficking: additive actions of two new endogenous anti-inflammatory mediators. J Hematother Stem Cell Res 10, 75–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Li P, Ogino K, Hoshikawa Y, Morisaki H, Cheng J, Toyama K, Morisaki T, Hashimoto K, Ninomiya H, Tomikura-Shimoyama Y, Igawa O, Shigemasa C, and Hisatome I. (2007) Remote reperfusion lung injury is associated with AMP deaminase 3 activation and attenuated by inosine monophosphate. Circ J 71, 591–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Csoka B, Nemeth ZH, Mukhopadhyay P, Spolarics Z, Rajesh M, Federici S, Deitch EA, Batkai S, Pacher P, and Hasko G. (2009) CB2 cannabinoid receptors contribute to bacterial invasion and mortality in polymicrobial sepsis. PLoS One 4, e6409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Csoka B, Nemeth ZH, Rosenberger P, Eltzschig HK, Spolarics Z, Pacher P, Selmeczy Z, Koscso B, Himer L, Vizi ES, Blackburn MR, Deitch EA, and Hasko G. (2010) A2B adenosine receptors protect against sepsis-induced mortality by dampening excessive inflammation. J Immunol 185, 542–550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Csoka B, Nemeth ZH, Szabo I, Davies DL, Varga ZV, Paloczi J, Falzoni S, Di Virgilio F, Muramatsu R, Yamashita T, Pacher P, and Hasko G. (2018) Macrophage P2X4 receptors augment bacterial killing and protect against sepsis. JCI Insight 3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Csoka B, Nemeth ZH, Toro G, Idzko M, Zech A, Koscso B, Spolarics Z, Antonioli L, Cseri K, Erdelyi K, Pacher P, and Hasko G. (2015) Extracellular ATP protects against sepsis through macrophage P2X7 purinergic receptors by enhancing intracellular bacterial killing. FASEB J 29, 3626–3637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Csoka B, Nemeth ZH, Toro G, Koscso B, Kokai E, Robson SC, Enjyoji K, Rolandelli RH, Erdelyi K, Pacher P, and Hasko G. (2015) CD39 improves survival in microbial sepsis by attenuating systemic inflammation. FASEB J 29, 25–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hasko G, Csoka B, Koscso B, Chandra R, Pacher P, Thompson LF, Deitch EA, Spolarics Z, Virag L, Gergely P, Rolandelli RH, and Nemeth ZH (2011) Ecto-5’-nucleotidase (CD73) decreases mortality and organ injury in sepsis. J Immunol 187, 4256–4267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhan X, Zhong X, Choi JH, Su L, Wang J, Nair-Gill E, Anderton P, Li X, Tang M, Russell J, Ludwig S, Gallagher T, and Beutler B. (2020) Adenosine monophosphate deaminase 3 null mutation causes reduction of naive T cells in mouse peripheral blood. Blood Adv 4, 3594–3605 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hasko G, and Szabo C. (1999) IL-12 as a therapeutic target for pharmacological modulation in immune-mediated and inflammatory diseases: regulation of T helper 1/T helper 2 responses. Br J Pharmacol 127, 1295–1304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deganutti G, Welihinda A, and Moro S. (2017) Comparison of the Human A2A Adenosine Receptor Recognition by Adenosine and Inosine: New Insight from Supervised Molecular Dynamics Simulations. ChemMedChem 12, 1319–1326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jin X, Shepherd RK, Duling BR, and Linden J. (1997) Inosine binds to A3 adenosine receptors and stimulates mast cell degranulation. J Clin Invest 100, 2849–2857 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Welihinda AA, Kaur M, Greene K, Zhai Y, and Amento EP (2016) The adenosine metabolite inosine is a functional agonist of the adenosine A2A receptor with a unique signaling bias. Cell Signal 28, 552–560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Welihinda AA, Kaur M, Raveendran KS, and Amento EP (2018) Enhancement of inosine-mediated A2AR signaling through positive allosteric modulation. Cell Signal 42, 227–235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Doyle C, Cristofaro V, Sack BS, Lukianov SN, Schafer M, Chung YG, Sullivan MP, and Adam RM (2017) Inosine attenuates spontaneous activity in the rat neurogenic bladder through an A2B pathway. Sci Rep 7, 44416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenberger P, Schwab JM, Mirakaj V, Masekowsky E, Mager A, Morote-Garcia JC, Unertl K, and Eltzschig HK (2009) Hypoxia-inducible factor-dependent induction of netrin-1 dampens inflammation caused by hypoxia. Nat Immunol 10, 195–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van Gils JM, Derby MC, Fernandes LR, Ramkhelawon B, Ray TD, Rayner KJ, Parathath S, Distel E, Feig JL, Alvarez-Leite JI, Rayner AJ, McDonald TO, O’Brien KD, Stuart LM, Fisher EA, Lacy-Hulbert A, and Moore KJ (2012) The neuroimmune guidance cue netrin-1 promotes atherosclerosis by inhibiting the emigration of macrophages from plaques. Nat Immunol 13, 136–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hasko G, Szabo C, Nemeth ZH, Kvetan V, Pastores SM, and Vizi ES (1996) Adenosine receptor agonists differentially regulate IL-10, TNF-alpha, and nitric oxide production in RAW 264.7 macrophages and in endotoxemic mice. J Immunol 157, 4634–4640 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Csoka B, Koscso B, Toro G, Kokai E, Virag L, Nemeth ZH, Pacher P, Bai P, and Hasko G. (2014) A2B Adenosine Receptors Prevent Insulin Resistance by Inhibiting Adipose Tissue Inflammation via Maintaining Alternative Macrophage Activation. Diabetes 63, 850–866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hasko G, Kuhel DG, Chen JF, Schwarzschild MA, Deitch EA, Mabley JG, Marton A, and Szabo C. (2000) Adenosine inhibits IL-12 and TNF-[alpha] production via adenosine A2a receptor-dependent and independent mechanisms. Faseb J 14, 2065–2074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nemeth ZH, Leibovich SJ, Deitch EA, Vizi ES, Szabo C, and Hasko G. (2003) cDNA microarray analysis reveals a nuclear factor-kappaB-independent regulation of macrophage function by adenosine. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 306, 1042–1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Szabo C, Scott GS, Virag L, Egnaczyk G, Salzman AL, Shanley TP, and Hasko G. (1998) Suppression of macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1alpha production and collagen-induced arthritis by adenosine receptor agonists. Br J Pharmacol 125, 379–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Koscso B, Csoka B, Kokai E, Nemeth ZH, Pacher P, Virag L, Leibovich SJ, and Hasko G. (2013) Adenosine augments IL-10-induced STAT3 signaling in M2c macrophages. J Leukoc Biol 94, 1309–1315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li J, Conrad C, Mills TW, Berg NK, Kim B, Ruan W, Lee JW, Zhang X, Yuan X, and Eltzschig HK (2021) PMN-derived netrin-1 attenuates cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury via myeloid ADORA2B signaling. J Exp Med 218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fonseca MT, Moretti EH, Marques LMM, Machado BF, Brito CF, Guedes JT, Komegae EN, Vieira TS, Festuccia WT, Lopes NP, and Steiner AA (2021) A leukotriene-dependent spleen-liver axis drives TNF production in systemic inflammation. Sci Signal 14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garcia Soriano F, Liaudet L, Marton A, Hasko G, Batista Lorigados C, Deitch EA, and Szabo C. (2001) Inosine improves gut permeability and vascular reactivity in endotoxic shock. Crit Care Med 29, 703–708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hasko G, Kuhel DG, Nemeth ZH, Mabley JG, Stachlewitz RF, Virag L, Lohinai Z, Southan GJ, Salzman AL, and Szabo C. (2000) Inosine inhibits inflammatory cytokine production by a posttranscriptional mechanism and protects against endotoxin-induced shock. J Immunol 164, 1013–1019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hasko G, Sitkovsky MV, and Szabo C. (2004) Immunomodulatory and neuroprotective effects of inosine. Trends Pharmacol Sci 25, 152–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liaudet L, Mabley JG, Soriano FG, Pacher P, Marton A, Hasko G, and Szabo C. (2001) Inosine reduces systemic inflammation and improves survival in septic shock induced by cecal ligation and puncture. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 164, 1213–1220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mabley JG, Pacher P, Liaudet L, Soriano FG, Hasko G, Marton A, Szabo C, and Salzman AL (2003) Inosine reduces inflammation and improves survival in a murine model of colitis. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 284, G138–144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gomez G, and Sitkovsky MV (2003) Differential requirement for A2a and A3 adenosine receptors for the protective effect of inosine in vivo. Blood 102, 4472–4478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hasko G, Linden J, Cronstein B, and Pacher P. (2008) Adenosine receptors: therapeutic aspects for inflammatory and immune diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov 7, 759–770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Antonioli L, Blandizzi C, Csoka B, Pacher P, and Hasko G. (2015) Adenosine signalling in diabetes mellitus-pathophysiology and therapeutic considerations. Nat Rev Endocrinol 11, 228–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Antonioli L, Blandizzi C, Pacher P, and Hasko G. (2013) Immunity, inflammation and cancer: a leading role for adenosine. Nature reviews. Cancer 13, 842–857 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Muller CE, and Jacobson KA (2011) Recent developments in adenosine receptor ligands and their potential as novel drugs. Biochim Biophys Acta 1808, 1290–1308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xiao C, Liu N, Jacobson KA, Gavrilova O, and Reitman ML (2019) Physiology and effects of nucleosides in mice lacking all four adenosine receptors. PLoS Biol 17, e3000161 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Masaki T, Chiba S, Tatsukawa H, Noguchi H, Kakuma T, Endo M, Seike M, Watanabe T, and Yoshimatsu H. (2005) The role of histamine H1 receptor and H2 receptor in LPS-induced liver injury. FASEB J 19, 1245–1252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moulton R, Spector WG, and Willoughby DA (1957) Histamine release and pain production by xanthosine and related compounds. Br J Pharmacol Chemother 12, 365–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.He B, Hoang TK, Wang T, Ferris M, Taylor CM, Tian X, Luo M, Tran DQ, Zhou J, Tatevian N, Luo F, Molina JG, Blackburn MR, Gomez TH, Roos S, Rhoads JM, and Liu Y. (2017) Resetting microbiota by Lactobacillus reuteri inhibits T reg deficiency-induced autoimmunity via adenosine A2A receptors. J Exp Med 214, 107–123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mager LF, Burkhard R, Pett N, Cooke NCA, Brown K, Ramay H, Paik S, Stagg J, Groves RA, Gallo M, Lewis IA, Geuking MB, and McCoy KD (2020) Microbiome-derived inosine modulates response to checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy. Science 369, 1481–1489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pastor-Anglada M, and Perez-Torras S. (2018) Who Is Who in Adenosine Transport. Front Pharmacol 9, 627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gupte A, and Buolamwini JK (2009) Synthesis and biological evaluation of phloridzin analogs as human concentrative nucleoside transporter 3 (hCNT3) inhibitors. Bioorg Med Chem Lett 19, 917–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kicska GA, Tyler PC, Evans GB, Furneaux RH, Kim K, and Schramm VL (2002) Transition state analogue inhibitors of purine nucleoside phosphorylase from Plasmodium falciparum. J Biol Chem 277, 3219–3225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schramm VL (2002) Development of transition state analogues of purine nucleoside phosphorylase as anti-T-cell agents. Biochim Biophys Acta 1587, 107–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Buras JA, Holzmann B, and Sitkovsky M. (2005) Animal models of sepsis: setting the stage. Nat Rev Drug Discov 4, 854–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ouyang X, Ghani A, Malik A, Wilder T, Colegio OR, Flavell RA, Cronstein BN, and Mehal WZ (2013) Adenosine is required for sustained inflammasome activation via the A(2)A receptor and the HIF-1alpha pathway. Nat Commun 4, 2909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Traut TW (1994) Physiological concentrations of purines and pyrimidines. Mol Cell Biochem 140, 1–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Poth JM, Brodsky K, Ehrentraut H, Grenz A, and Eltzschig HK (2013) Transcriptional control of adenosine signaling by hypoxia-inducible transcription factors during ischemic or inflammatory disease. J Mol Med (Berl) 91, 183–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hart ML, Grenz A, Gorzolla IC, Schittenhelm J, Dalton JH, and Eltzschig HK (2011) Hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha-dependent protection from intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury involves ecto-5’-nucleotidase (CD73) and the A2B adenosine receptor. J Immunol 186, 4367–4374 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 63.Kong T, Westerman KA, Faigle M, Eltzschig HK, and Colgan SP (2006) HIF-dependent induction of adenosine A2B receptor in hypoxia. FASEB J 20, 2242–2250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Morote-Garcia JC, Rosenberger P, Kuhlicke J, and Eltzschig HK (2008) HIF-1-dependent repression of adenosine kinase attenuates hypoxia-induced vascular leak. Blood 111, 5571–5580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lukashev D, Ohta A, and Sitkovsky M. (2004) Targeting hypoxia--A(2A) adenosine receptor-mediated mechanisms of tissue protection. Drug Discov Today 9, 403–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lukashev D, Ohta A, and Sitkovsky M. (2007) Hypoxia-dependent anti-inflammatory pathways in protection of cancerous tissues. Cancer Metastasis Rev 26, 273–279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sitkovsky MV (2009) T regulatory cells: hypoxia-adenosinergic suppression and re-direction of the immune response. Trends in immunology 30, 102–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Eltzschig HK, Bonney SK, and Eckle T. (2013) Attenuating myocardial ischemia by targeting A2B adenosine receptors. Trends Mol Med 19, 345–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ji M, Lee H-S, Kim Y, Seo C, Oh S, Jung ID, Park J-H, and Paik M-J (2021) Metabolomic Study of Normal and Modified Nucleosides in the Urine of Mice with Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Sepsis by LC–MS/MS. Bulletin of the Korean Chemical Society 42, 611–617 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Transcriptome data will be deposited in NCBI’s Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database and will be accessible through GEO Series accession number: GSE183880(transcriptome data upload is in progress.)