Abstract

Objective

We aimed to clinically characterize the health, neurocognitive, and physical function outcomes of curative treatment for Wilms tumor.

Methods

Survivors of Wilms tumor (n=280) participating in the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort, a retrospective study with prospective follow up of individuals treated for childhood cancer at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, were clinically evaluated and compared to age and sex-matched controls (n=625). Health conditions were graded per a modified version of the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events. Standardized neurocognitive testing was graded utilizing age-adjusted z-scores. Impaired physical function was defined by age- and sex-matched z-scores >1.5 SD below controls. Modified Poisson regression was used to compare the prevalence of conditions and multivariable logistic regression to examine treatment associations.

Results

Median age at evaluation was similar between survivors and controls (30.5 years [9.0–58.0] and 31.0 [12.0–70.0]). Therapies included nephrectomy (100%), vincristine (99.3%), dactinomycin (97.9%), doxorubicin (66.8%), and abdominal (59.3%) and/or chest radiation (25.0%). By age 40 years, survivors averaged 12.7 (95% confidence interval [CI] 11.7–13.8) grade 1–4 and 7.5 (CI 6.7–8.2) grade 2–4 health conditions, compared to 4.2 (CI 3.9–4.6) and 2.3 (CI 2.1–2.5), respectively, among controls. Grade 2–4 endocrine (53.9%), cardiovascular (26.4%), pulmonary (18.2%), neurologic (8.6%), neoplastic (7.9%), and kidney (7.2%) conditions were most prevalent. Survivors exhibited neurocognitive and physical performance impairments.

Conclusion

Wilms tumor survivors experience a three-fold higher burden of chronic health conditions compared to controls and late neurocognitive and physical function deficits. Individualized clinical management, counseling, and surveillance may improve long-term health maintenance.

Introduction

Wilms tumor, the most common kidney tumor of childhood, accounts for 5% of pediatric malignancies.1 Sequential multi-institutional clinical trials within the National Wilms Tumor Study Group, the Renal Tumor Committee of the Children’s Oncology Group, and the International Society of Pediatric Oncology have established curative multimodal therapeutic regimens for these children,2 yielding progressively higher five-year survival rates, exceeding 90% for those with favorable histology.1

While treatment regimens are largely successful, exposure to cancer therapy in childhood has long term health implications. The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study (CCSS), using self-reported data, found excess morbidity and mortality among survivors of Wilms tumor compared to a sibling comparison group.3, 4 The cumulative incidence of any chronic health condition 25 years from diagnosis was 65% and 24% for severe, life-threatening, or fatal conditions.5 Cohort studies across North America and Europe have reported similar excess late morbidity and mortality.6–9 These descriptions have relied on registry and self-reported data,5–9 which often lack sufficient detail and likely underestimate the presence of premature, subclinical conditions. Using the clinically assessed St. Jude Lifetime (SJLIFE) cohort, we aimed to comprehensively characterize health conditions and neurocognitive and physical function among survivors of Wilms tumor.

Methods

Study Design and Population

The SJLIFE study, initiated in 2007, is a single center retrospective cohort study with prospective clinical assessments of 5-year survivors of childhood cancer treated at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (SJCRH) from 1962–2012.10 This analysis includes participants diagnosed with Wilms tumor who returned for an on-campus health evaluation (n=280). Additionally, a community control group (n=625) was recruited for comparison (Supplemental Table 1). The study protocol was approved by the SJCRH Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was obtained prior to participation.

Clinical encounters included a history and physical examination; a fasting laboratory battery; questionnaires detailing demographics, medical history, health habits, and quality of life; and standardized neurocognitive and physical function testing.10 Therapeutic exposures abstracted from the medical record included cumulative chemotherapy doses, radiation fields/doses, surgeries, and major medical events during and after cancer treatment. Participants consented to medical record release for validation and grading of health conditions diagnosed prior to SJLIFE evaluations.

Chronic Health Conditions

One hundred sixty eight chronic health conditions were assessed and graded according to a modified version of the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) v4.0311 (grade 1=asymptomatic or mild, 2=moderate requiring minimal intervention, 3=severe or disabling, 4=life threatening). Prevalence of health conditions and psychological outcomes was assessed.

Neurocognitive Assessment

Standardized neurocognitive assessments (Supplemental Table 2), performed by certified examiners, supervised by a board-certified neuropsychologist, measured performance in four domains: attention,12 executive function,13–15 memory,16 and processing speed.15 Age-adjusted z-scores were used for grading; ≥1 and <2 standard deviations (SD) below the population mean were considered mild (grade 1), ≥2 and <3 SD below the population mean moderate (grade 2), and ≥3 SD below the population mean severe (grade 3). Participants unable to complete a particular test were excluded from analysis for that domain.

Physical Function Assessment

Performance testing (Supplemental Table 3) was conducted by exercise specialists to ascertain physical function in six domains: aerobic capacity,17 mobility,18 strength,19, 20 endurance,20 flexibility,21, 22 and balance.23 Survivors performing >1.5 SDs below age- and sex-matched z-scores for controls were considered impaired in that domain. Participants unable to perform a particular test were excluded from analysis for that domain.

Statistical analysis

Two-sample t-tests were used to compare continuous variables. Chi-square (χ2) or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate, were used for categorical variables between participants and eligible non-participants and between survivors and controls.

The prevalence of physical function impairments was compared to the standard population using a one sample t-test. Modified Poisson regression, adjusted for age, sex, and race, was used to compare the prevalence of CTCAE graded conditions, subsequent neoplasms, neurocognitive outcomes, and physical function between survivors and controls. Smoking was added to models for pulmonary outcomes.

The standardized incidence ratio (SIRs) of secondary neoplasms was calculated using age-, sex-, and calendar year-specific cancer incidence from the NCI’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results program. Non-melanoma skin cancers are not registered in the SEER database and were not included in the SIR calculation.

The mean cumulative count (MCC) was calculated by individual chronic conditions after accounting for clinically relevant chronicity and recurrence measures. The overall cumulative burden of grade 1–4 and 2–4 conditions was calculated after summing the individual MCCs. The age-specific cumulative burden and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated by summing chronic health conditions occurring per individual using the bootstrap percentile method. Statistical testing was considered significant at p<0.05. All analyses were completed using SAS 9.4 and R.

Results

Of 445 eligible Wilms tumor survivors, 280 (63%) returned for evaluation. Sixty-nine (15.5%) agreed but had not yet returned, 16 (3.6%) participated by survey only, 46 (10.3%) declined, 9 (2.0%) could not be located, and 25 (5.6%) were pending recruitment (Supplemental Figure 1).

Participants were more likely to be non-Hispanic white (73.2% vs. 62.4%, p=0.02), older at evaluation (median 30.5 vs. 26.0 years, p=0.01) and farther from cancer diagnosis (26.0 vs. 22.0 years, p<0.01) than non-participants (Supplemental Table 1). Demographic and treatment-related characteristics of study participants are shown in Table 1. Nearly all (92.1%) were diagnosed prior to age six years (median 3.0 years, range: 0.0–15.0), with a median time from diagnosis of 26.0 years (6.0–54.0). Compared to controls, survivors were similar in age (median 30.5 [9.0–58.0] vs. 31.0 [12.0–70.0] years, p=0.32), but more racially diverse (26.8% non-white vs. 17.6%, p <0.01). Survivors (≥25 years old) were less likely to work full time (p<0.01), be married (p<0.01), or complete higher education (p<0.01) than community controls.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study participants and controls

| Wilms Survivors (N=280) | Community Controls (N=625) | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 165 | 58.9% | 347 | 55.5% | ||

| Male | 115 | 41.1% | 278 | 44.5% | 0.34 | |

| Race | ||||||

| White | 205 | 73.2% | 515 | 82.4% | ||

| Non-White | 75 | 26.8% | 110 | 17.6% | <0.01 | |

| Age at last evaluation (years) | ||||||

| Median (range) | 30.5 (9.0–58.0) | 31.0 (12.0–70.0) | ||||

| <18 years | 45 | 16.1% | 19 | 3.0% | ||

| 18–29 years | 89 | 31.8% | 250 | 40.0% | ||

| 30–39 years | 99 | 35.4% | 196 | 31.4% | ||

| ≥40 years | 47 | 16.8% | 160 | 25.6% | <0.01 | |

| Age at diagnosis (years) | ||||||

| Median (range) | 3.0 (0.0–15.0) | |||||

| 0–3 years | 179 | 63.9% | ||||

| 4–6 years | 79 | 28.2% | ||||

| 7–9 years | 13 | 4.6% | ||||

| ≥10 years | 9 | 3.2% | ||||

| Time from diagnosis (years) | ||||||

| Median (range) | 26.0 (6.0–54.0) | |||||

| 5–9 years | 13 | 4.6% | ||||

| 10–19 years | 69 | 24.6% | ||||

| 20–29 years | 92 | 32.9% | ||||

| 30–39 years | 77 | 27.5% | ||||

| ≥40 years | 29 | 10.4% | ||||

| Laterality | ||||||

| Unilateral | 259 | 92.5% | ||||

| Bilateral | 21 | 7.5% | ||||

| Genetic syndrome | ||||||

| Beckwith Wiedemann | 4 | 1.4% | ||||

| WAGR± | 2 | 0.71% | ||||

| Denys Drash | 1 | 0.36% | ||||

| Polycystic Kidney Disease | 1 | 0.36% | ||||

| Hyperparathyroid Jaw Tumor | 1 | 0.36% | ||||

| Relapse | ||||||

| Yes | 26 | 9.3% | ||||

| No | 254 | 90.7% | ||||

| Education, among age ≥25 | ||||||

| Less than high school | 11 | 5.9% | 13 | 2.8% | ||

| Completed high school/GED | 34 | 18.3% | 52 | 11.4% | ||

| Vocational training/Some college | 68 | 36.6% | 105 | 22.9% | ||

| College graduate and higher | 72 | 38.7% | 283 | 61.8% | ||

| Unknown | 1 | 0.5% | 5 | 1.1% | <0.01 | |

| Employment, among age ≥25 | ||||||

| Full-time | 119 | 64.0% | 337 | 73.6% | ||

| Part-time | 20 | 10.8% | 47 | 10.3% | ||

| Not employed | 37 | 19.9% | 41 | 9.0% | ||

| Student/Homemaker/Retired | 5 | 2.7% | 26 | 5.7% | ||

| Unknown | 5 | 2.7% | 7 | 1.5% | <0.01 | |

| Insurance status | ||||||

| Yes | 226 | 80.7% | 510 | 81.6% | ||

| No | 37 | 13.2% | 71 | 11.4% | ||

| Unknown | 17 | 6.1% | 44 | 7.0% | 0.66 | |

| Marital status, among age ≥25 | ||||||

| Missing | 0 | 0.0% | 9 | 2.0% | ||

| Single | 37 | 19.9% | 52 | 11.4% | ||

| Married, living as married | 113 | 60.8% | 350 | 76.4% | ||

| Widowed/Divorced/Separated | 36 | 19.4% | 47 | 10.3% | ||

| Unknown | 0 | 0.0% | 9 | 2.0% | <0.01 | |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Nonsmoker | 176 | 62.9% | 417 | 66.7% | ||

| Ever smoker | 49 | 17.5% | 100 | 16.0% | ||

| Current smoker | 34 | 12.1% | 72 | 11.5% | ||

| Unknown | 21 | 7.5% | 36 | 5.8% | 0.64 | |

| Treatment characteristics | ||||||

| Surgery | ||||||

| Unilateral nephrectomy | 259 | 92.5% | ||||

| Unilateral partial nephrectomy + contralateral biopsy | 4 | 1.4% | ||||

| Unilateral nephrectomy + contralateral partial nephrectomy | 11 | 3.9% | ||||

| Bilateral partial nephrectomies | 6 | 2.2% | ||||

| Chemotherapy | ||||||

| Vincristine | ||||||

| Median (range) | 22.6 (6.0–92.0) | |||||

| None | 2 | 0.7% | ||||

| <20 mg/m2 | 114 | 40.7% | ||||

| 20–30 mg/m2 | 50 | 17.9% | ||||

| ≥30 mg/m2 | 114 | 40.7% | ||||

| Doxorubicin | ||||||

| Median (range) | 175.0 (52.2–490.1) | |||||

| None | 93 | 33.2% | ||||

| <100 mg/m2 | 13 | 4.6% | ||||

| 100–250 mg/m2 | 153 | 54.6% | ||||

| ≥250 mg/m2 | 21 | 7.5% | ||||

| Dactinomycin | ||||||

| Median (range) (mg/m2) | 6.7 (1.2–19.4) | |||||

| None | 6 | 2.1% | ||||

| Yes | 274 | 97.9% | ||||

| Alkylating agents | ||||||

| Median (range) (cyclophosphamide equivalent dose (CED) mg/m2) | 7060.6 (2258–35482) | |||||

| None | 246 | 87.9% | ||||

| Yes | 34 | 12.1% | ||||

| Etoposide | ||||||

| Median (range) (mg/m2) | 1282.2 (337.5–3852.1) | |||||

| None | 243 | 86.8% | ||||

| Yes | 37 | 13.2% | ||||

| Cisplatin | ||||||

| Median (range) (mg/m2) | 430.2 (99.3–1219.5) | |||||

| None | 251 | 89.6% | ||||

| Yes | 29 | 10.4% | ||||

| Radiation | ||||||

| Abdominal | ||||||

| Median dose (range) (cGy) | 1200.0 (880.0–6120.0) | |||||

| None | 114 | 40.7% | ||||

| Hemiabdomen* | 75 | 26.8% | ||||

| Whole abdomen** | 91 | 32.5% | ||||

| Chest | ||||||

| Median dose (range) (cGy) | 1200.0 (900.0–4400.0) | |||||

| None | 210 | 75.0% | ||||

| Yes | 70 | 25.0% | ||||

cGy, centigray; CED, cyclophosphamide equivalent dose; <, less than; mg/m2, milligrams per square meter; ≥, more than or equal to; N, number; %, percentage; p, probability

Wilms tumor, aniridia, genitourinary anomalies, intellectual disability

Left hemiabdomen = 36 and right hemiabdomen = 39

Whole abdomen also included 12 survivors treated with both whole and hemiabdomen (left = 6) and right = 6)

All Wilms survivors underwent surgery, with the majority being unilateral nephrectomy (96.4%). The most common chemotherapeutic exposures included vincristine (99.3%) and dactinomycin (97.9%), and two-thirds (67%) were treated with doxorubicin. Nearly 60% received abdominal (whole and/or hemiabdomen) radiation (median dose 1200 [880–6120] cGy) and 25% chest radiation (median dose 1200 [900–4400] cGy). Twenty-six survivors (9%) experienced relapse (Table 1).

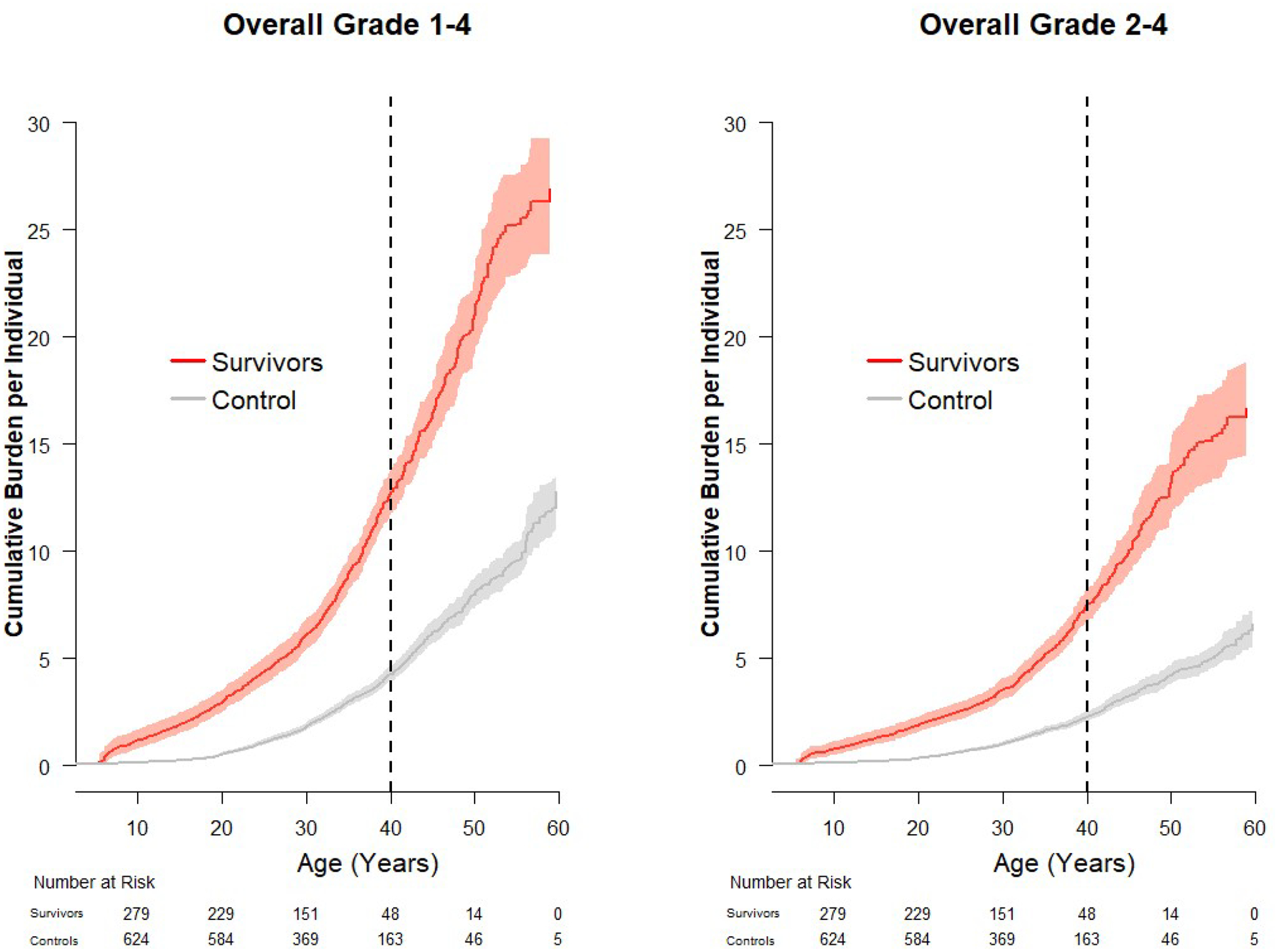

Chronic Health Conditions

By age 40 years, survivors averaged 12.7 (95% confidence interval [CI] 11.7–13.8) grade 1–4 and 7.5 (95% CI 6.7–8.2) grade 2–4 conditions, compared to 4.2 (95% CI 3.9–4.6) and 2.3 (95% CI 2.1–2.5), respectively, among controls (Figure 1). Conditions of the cardiovascular, pulmonary, endocrine, and reproductive systems contributed the largest excess burden (Supplemental Table 4a/4b).

Figure 1.

Cumulative burden and 95% confidence intervals of grade 1–4 and grade 2–4 chronic health conditions in survivors of Wilms tumor and community controls.

Nearly all (99.6%) Wilms tumor survivors had at least one grade 1–4 condition and 91.8% a grade 2–4 condition. The most prevalent conditions, adjusted for sex, current age, and race, are reported in Table 2. Over 50% of survivors had grade 1–4 hypertension and 19.2% were on medication or met criteria for treatment initiation (grade 2–4) compared to 42.6% and 11.2%, respectively, among controls (p<0.01). Grade 2–4 cardiomyopathy was identified in 6.5% of survivors vs. 2.6% of controls (p=0.01). A fifth of survivors had a total cholesterol >200 mg/dL or triglycerides >150 mg/dL (grade 1–4), with 1.8% and 6.3%, respectively, exceeding 300 mg/dL (≥grade 2) and/or already on lipid lowering therapy. Excess grade 2–4 obstructive (11.7% vs. 2.9%, p<0.01), restrictive (9.6% vs. 0.2%, p<0.01) and diffusion (10.4% vs. 0.3%, p<0.01) pulmonary impairments were observed in survivors compared to controls. Adjusting for smoking status, pulmonary diffusion defects were associated with doxorubicin (RR 3.9, 95% CI 1.2–12.6) and restrictive deficits with chest radiation (RR 12.3, 95% CI 1.8–86.4).

Table 2.

Prevalence and severity of chronic health conditions *

| Wilms Survivors (n=280) | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number screened | % | Normal | % | Grade 1 | % | Grade 2 | % | Grade 3 | % | Grade 4 | % | |

| Cardiovascular | ||||||||||||

| Cardiomyopathy | 278 | 99.3% | 260 | 93.5% | 9 | 3.2% | 9 | 3.2% | 0 | 0.0% | ||

| Heart Valve Disorder | 275 | 98.2% | 221 | 80.4% | 50 | 18.2% | 2 | 0.7% | 1 | 0.4% | 1 | 0.4% |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 280 | 100.0% | 216 | 77.1% | 59 | 21.1% | 5 | 1.8% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 272 | 97.1% | 220 | 80.9% | 35 | 12.9% | 13 | 4.8% | 4 | 1.5% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Hypertension | 280 | 100.0% | 136 | 48.6% | 90 | 32.1% | 41 | 14.6% | 13 | 4.6% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Endocrine | ||||||||||||

| Abnormal Glucose Metabolism | 276 | 98.6% | 214 | 77.5% | 40 | 14.5% | 11 | 4.0% | 11 | 4.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Overweight/Obesity | 280 | 100.0% | 133 | 47.5% | 79 | 28.2% | 54 | 19.3% | 14 | 5.0% | ||

| Underweight | 280 | 100.0% | 264 | 94.3% | 16 | 5.7% | ||||||

| Gastrointestinal | ||||||||||||

| Hepatopathy | 280 | 100.0% | 269 | 96.1% | 11 | 3.9% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Musculoskeletal | ||||||||||||

| Bone Mineral Density Deficit | 238 | 85.0% | 116 | 48.7% | 86 | 36.1% | 36 | 15.1% | 0 | 0.0% | ||

| Neurologic | ||||||||||||

| Peripheral Motor Neuropathy | 269 | 96.1% | 253 | 94.1% | 6 | 2.2% | 10 | 3.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Peripheral Sensory Neuropathy | 268 | 95.7% | 208 | 77.6% | 41 | 15.3% | 17 | 6.3% | 2 | 0.8% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Pulmonary | ||||||||||||

| Obstructive Ventilatory Defect | 273 | 97.5% | 198 | 72.5% | 43 | 15.8% | 24 | 8.8% | 7 | 2.6% | 1 | 0.4% |

| Pulmonary Diffusion Defect | 270 | 96.4% | 216 | 80.0% | 26 | 9.6% | 27 | 10.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 1 | 0.4% |

| Restrictive Ventilatory Defect | 272 | 97.1% | 228 | 83.8% | 18 | 6.6% | 18 | 6.6% | 8 | 2.9% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Renal/Urinary Tract | ||||||||||||

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 279 | 99.6% | 251 | 90.0% | 8 | 2.9% | 10 | 3.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 10 | 3.6% |

| Reproductive/Genital | ||||||||||||

| Leydig Cell Insufficiency | 113 | 98.3% | 111 | 98.2% | 2 | 1.8% | ||||||

| Premature Ovarian Insufficiency┼ | 150 | 90.9% | 136 | 90.7% | 14 | 9.3% | ||||||

| Psychological | ||||||||||||

| Anxiety | 266 | 95.0% | 167 | 62.8% | 33 | 12.4% | 50 | 18.8% | 15 | 5.6% | 1 | 0.4% |

| Depression | 280 | 100.0% | 186 | 66.4% | 24 | 8.6% | 46 | 16.4% | 24 | 8.6% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Suicide Attempt | 254 | 90.7% | 250 | 98.4% | 3 | 1.2% | 1 | 0.4% | ||||

| Controls (n=625) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number screened | % | Normal | % | Grade 1 | % | Grade 2 | % | Grade 3 | % | Grade 4 | % | ||

| Cardiovascular | |||||||||||||

| Cardiomyopathy | 618 | 98.9% | 602 | 97.4% | 14 | 2.3% | 2 | 0.3% | 0 | 0.0% | <0.01 | ||

| Heart Valve Disorder | 622 | 99.5% | 520 | 83.6% | 99 | 15.9% | 3 | 0.5% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.02 |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 625 | 100.0% | 464 | 74.2% | 159 | 25.4% | 2 | 0.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.88 |

| Hypertriglyceridemia | 618 | 98.9% | 506 | 81.9% | 95 | 15.4% | 15 | 2.4% | 2 | 0.3% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.46 |

| Hypertension | 625 | 100.0% | 359 | 57.4% | 196 | 31.4% | 59 | 9.4% | 11 | 1.8% | 0 | 0.0% | <0.01 |

| Endocrine | |||||||||||||

| Abnormal Glucose Metabolism | 622 | 99.5% | 513 | 82.5% | 92 | 14.8% | 15 | 2.4% | 2 | 0.3% | 0 | 0.0% | <0.01 |

| Overweight/Obesity | 625 | 100.0% | 258 | 41.3% | 170 | 27.2% | 150 | 24.0% | 47 | 7.5% | 0.13 | ||

| Underweight | 625 | 100.0% | 611 | 97.8% | 14 | 2.2% | <0.01 | ||||||

| Gastrointestinal | |||||||||||||

| Hepatopathy | 625 | 100.0% | 605 | 96.8% | 19 | 3.0% | 1 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0.27 |

| Musculoskeletal | |||||||||||||

| Bone Mineral Density Deficit | 0^ | ||||||||||||

| Neurologic | |||||||||||||

| Peripheral Motor Neuropathy | 614 | 98.2% | 608 | 99.0% | 2 | 0.3% | 4 | 0.7% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | <0.01 |

| Peripheral Sensory Neuropathy | 604 | 96.6% | 528 | 87.4% | 63 | 10.4% | 13 | 2.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | <0.01 |

| Pulmonary | |||||||||||||

| Obstructive Ventilatory Defect | 617 | 98.7% | 561 | 90.9% | 38 | 6.2% | 14 | 2.3% | 3 | 0.5% | 1 | 0.2% | <0.01 |

| Pulmonary Diffusion Defect | 615 | 98.4% | 594 | 96.6% | 19 | 3.1% | 1 | 0.2% | 1 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | <0.01 |

| Restrictive Ventilatory Defect | 615 | 98.4% | 604 | 98.2% | 10 | 1.6% | 1 | 0.2% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | <0.01 |

| Renal/Urinary Tract | |||||||||||||

| Chronic Kidney Disease | 624 | 99.8% | 620 | 99.4% | 0 | 0.0% | 4 | 0.6% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | <0.01 |

| Reproductive/Genital | |||||||||||||

| Leydig Cell Insufficiency | 278 | 100.0% | 278 | 100.0% | 0 | 0.0% | N/A | ||||||

| Premature Ovarian Insufficiency┼ | 318 | 91.6% | 316 | 99.4% | 2 | 0.6% | <0.01 | ||||||

| Psychological | |||||||||||||

| Anxiety | 622 | 99.5% | 466 | 74.9% | 57 | 9.2% | 79 | 12.7% | 20 | 3.2% | 0 | 0.0% | <0.01 |

| Depression | 624 | 99.8% | 496 | 79.5% | 46 | 7.4% | 58 | 9.3% | 23 | 3.7% | 1 | 0.2% | <0.01 |

| Suicide Attempt | 606 | 97.0% | 601 | 99.2% | 4 | 0.7% | 1 | 0.2% | 0.40 | ||||

adjusted for sex, current age, and race

DEXA scans were not performed on control participants

Premature Ovarian Insufficiency was only assessed among female survivors ≤ age 40 years.

<, less than; N/A, not applicable; N, number; %, percentage

Survivors also experienced a higher rate of abnormal glucose metabolism (22.4% vs. 17.5% grade 1–4 and 8.0% vs. 2.7% grade 2–4, p<0.01), and among survivors this was associated with abdominal radiation (RR 4.8, CI 1.7–13.7). This was not associated with overweight/obesity (52.5% v. 58.7%, p=0.13) in survivors compared to controls, as might be expected in the general population. In fact, 5.7% of survivors were underweight at clinical evaluation compared to 2.2% of controls (p<0.01).

Survivors experienced more kidney dysfunction than controls (10.0% vs. 0.6% grade 1–4; 7.2% v. 0.6% grade 2–4, p<0.01). Among adult (≥18 years old) survivors (n=235) the median estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) was 96.5 ml/min/1.73 m2 (range: 3.7–146.7).

Over 8% of survivors experienced grade 2–4 peripheral neuropathy, compared to 2.6% of controls (p<0.01). Females experienced excess ovarian failure prior to age 40 (9.3% vs. 0.6%, p<0.01), while 1.8% of males had evidence of Leydig cell insufficiency.

Subsequent Neoplasms

A mean of 27.7 years from diagnosis, 24 (8.6%) Wilms survivors developed 36 subsequent neoplasms (SN), half occurring in prior radiation fields. Non-melanoma skin cancers were most common (n=22), followed by gastrointestinal (n=3), thyroid (n=2), breast (n=2), sarcomas (n=5), and melanomas (n=2). Survivors had nearly a 4-fold increased risk (SIR 3.8, CI 2.1–6.3) for SN compared to the general population. While suggestive, an association with radiation exposure did not reach statistical significance (RR 3.4, CI 0.9–13.4, p=0.08).

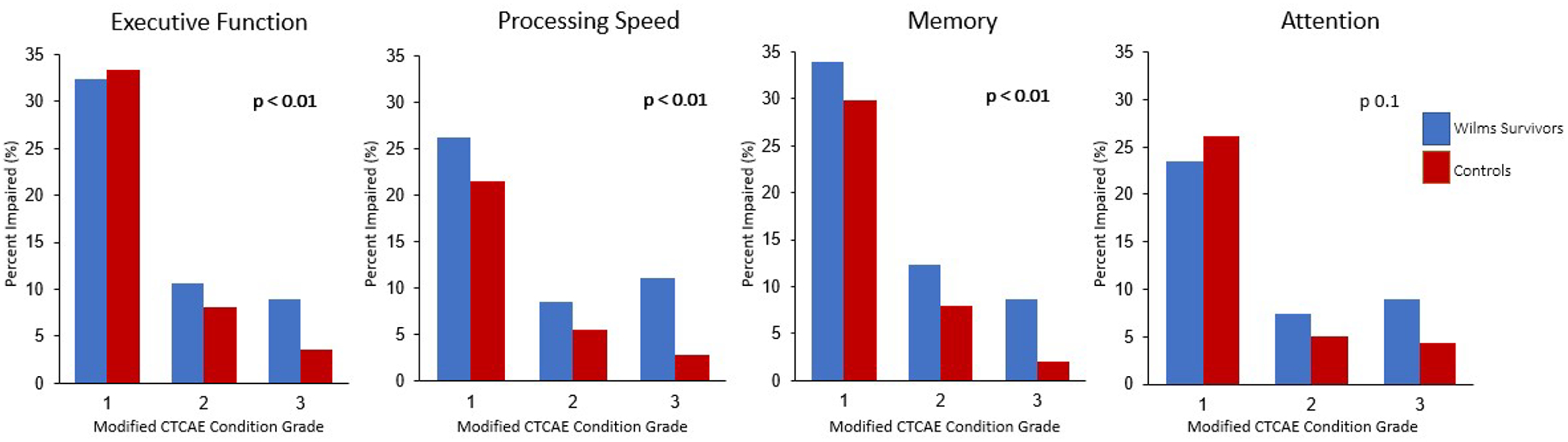

Neurocognitive Function and Psychological Outcomes

Among 246 survivors who completed neurocognitive testing, 52.1% had grades 1–3 and 19.7% grades 2–3 executive function impairment (Figure 2), compared to 45.0% and 11.6%, respectively, among controls (p<0.01). Processing speed (19.7% vs. 8.4%) and memory (20.9% vs. 9.9%) similarly showed a higher prevalence of moderate to severe impairments (grade 2–3) compared to controls (p<0.01). No differences in attention were identified. Associations with treatment exposures were not identified. Non-white survivors were noted to have double the risk of neurocognitive impairment across all domains compared to non-Hispanic white survivors (Supplemental Table 5a). In addition to excess neurocognitive impairment, anxiety (24.8% vs. 15.9% [p<0.01]) and/or depression (25% vs. 13.1% [p<0.01]) were identified more often in survivors than controls.

Figure 2.

Prevalence and grade of neurocognitive impairment among survivors of Wilms tumor and controls by neurocognitive domain.

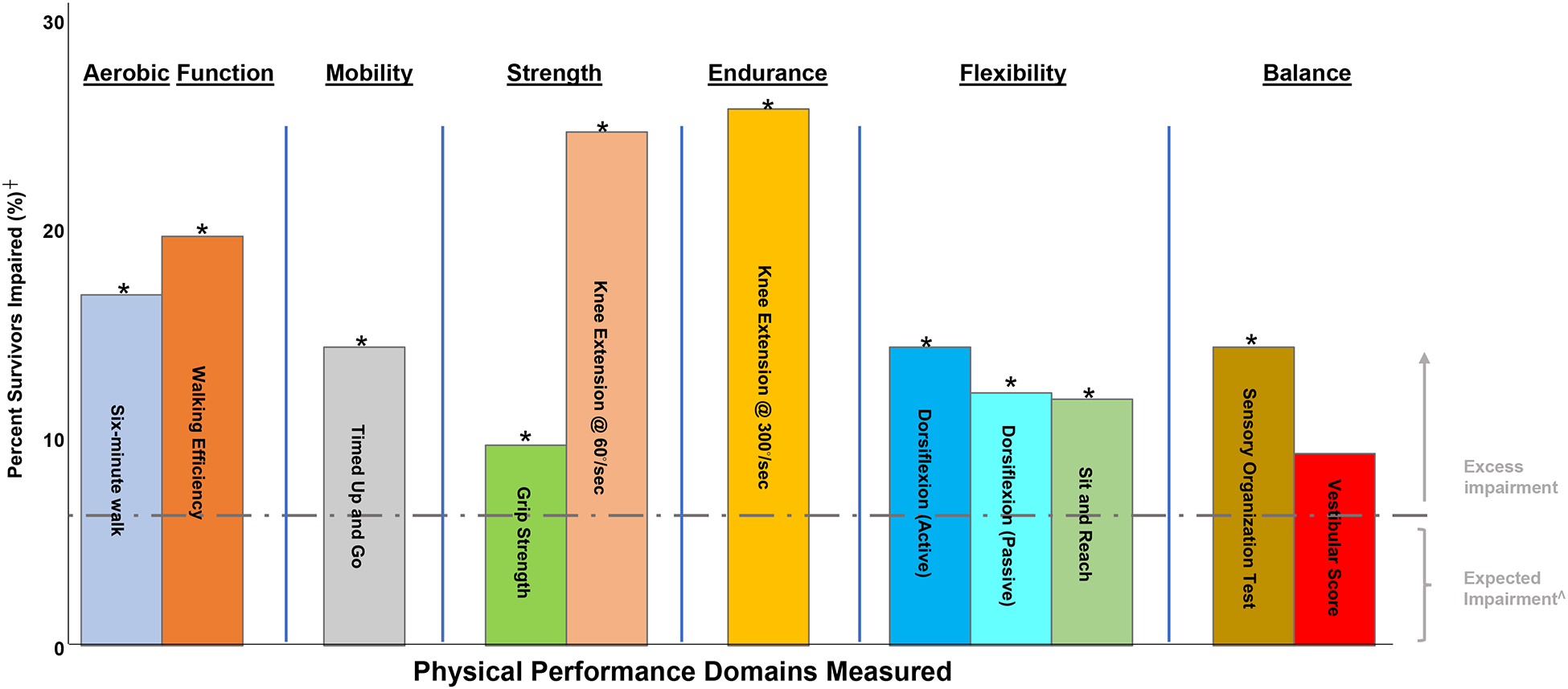

Physical Function

Two hundred seventy survivors completed physical function testing and impairments exceeded expected rates across all domains (Figure 3). Excess impairments were identified in aerobic function, mobility, strength, endurance, and flexibility (p<0.05). No associations with treatment exposures or level of physical activity were identified. However, having a grade 2–4 cardiac condition was associated with impaired six-minute walk (RR 2.2,95% CI 1.3–3.8), grip strength (RR 2.5, 95% CI 1.1–5.3), and knee extension at 60◦/second (RR 1.6, 95% CI 1.1–2.5) and 300◦/second (RR 2.0, 95% CI 1.4–3.0), respectively (Supplemental Table 6).

Figure 3.

Prevalence of physical performance impairment in survivors of Wilms tumor.

┼ Percent with scores >1.5 SD below age and sex-matched z-score for controls.

* p <0.05

Λ Percentage of the general population performing >1.5 standard deviations below age- and sex-matched z-scores

Discussion

Multimodal treatment strategies have advanced cure rates for children diagnosed with Wilms tumor. However, treatment exposures have significant impacts on long-term health. Our systematic, clinical evaluations identified nearly a 3-fold increased health burden, largely driven by endocrine and cardiopulmonary conditions. Additionally, we found clinically assessed impairments in neurocognitive and physical function that can impact health and quality of life for this population. In our analysis, nearly all (99.6%) had at least one chronic health condition, with most (92%) requiring clinical intervention (grade 2–4). Survivors had an almost 4-fold increased risk (SIR 3.8, CI 2.1–6.3) for subsequent neoplasms. This excess health burden was accompanied by a higher-than-expected prevalence of mental health disorders, limited neurocognitive performance, and physical function impairments. These factors may contribute to impaired social attainment and lower rates of employment, marriage, and educational attainment in this population. Attention to these unique risk profiles offer opportunities for early detection and treatment of these health consequences to preserve quality of life.

Wilms treatment regimens have historically been associated with an elevated risk of cardiovascular disease,24, 25 the leading causes of non-malignant late mortality in survivors of childhood cancer, as well as in the general population.26 This analysis identified excess cardiomyopathy in survivors compared to controls, which is anticipated following cardiotoxic exposures (anthracyclines and chest radiation). Additionally, survivors in our cohort experienced excess cardiovascular risk factors (hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes)27 and nearly a third (29.6%) reported a smoking history. When criteria from the American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology28 for hypertension (Supplemental Table 7) are applied to participant data, 26.6% of survivors meet criteria for a diagnosis of hypertension, with an additional 22% meeting criteria for prehypertension at a median of 31 years of age. Similarly, using American Diabetes Association criteria for diabetes29 (Supplemental Table 7), 33.2% of our survivors met criteria for prediabetes and 7.7% diabetes, compared to 19.8% and 4.5%, respectively, in controls. Modification of these risk factors can play a major role in preserving survivor health. In a CCSS study, the presence of hypertension significantly augmented the risk of developing heart failure (RR 19.4, 95% CI 11.4–33.1) and premature coronary artery disease (RR 6.1, 95% CI 3.4–11.2) among survivors exposed to chest radiation compared to those without hypertension.30 Lifestyle modification (smoking, diet, etc.) and management of chronic conditions may have significant health implications for Wilms tumor survivors.

The increased prevalence of heart disease and cardiovascular risk factors has implications for kidney function.31 This study includes survivors of bilateral and syndromic Wilms tumor, which may partially account for the higher prevalence of chronic kidney disease in our study compared with prior studies of unilateral, non-syndromic Wilms tumor survivors.32 Two-thirds of survivors with renal impairment in our study had co-morbid hypertension, diabetes, or both. In three-fourths of these cases, the onset of diabetes and/or hypertension was documented prior to reduced kidney function. Hyperfiltration injury following nephrectomy may also be a contributing factor. Animal studies involving unilateral nephrectomy and five-sixths infarction of the contralateral kidney showed an increase in single nephron glomerular filtration rates, morphological changes, and hypertension, suggesting injury from increased filtration.33 Lacking longitudinal data from the time of nephrectomy, our cross-sectional analysis may have missed the hyperfiltration period. Studies are needed to elucidate the association of hyperfiltration and adverse kidney function among Wilms tumor survivors.

The identification of a significant burden of SNs in this population is consistent with previous studies of kidney tumors34 and highlights the role of cancer screening and surveillance in survivors exposed to radiation, according to the Children’s Oncology Group Long-term Follow-up Guidelines.35 These survivors should undergo a thorough annual skin exam, and those with chest and/or abdominal radiation are at increased risk of breast36, 37 and colon38 cancer, respectively. Early initiation of screening may lead to detection at earlier stages, additional treatment options, and opportunities to improve outcomes.

In addition to increased risk for cardiometabolic, kidney and neoplastic late effects, long-term survivors of Wilms tumor are at increased risk of infertility. Nearly 10% of female survivors experienced premature ovarian insufficiency, likely due to abdominal radiation exposing the ovaries.7, 39–42 None of the females exposed to hemi-abdominal radiation experienced premature ovarian insufficiency. Previous reports have also identified structural uterine abnormalities,43, 44 and risks for premature deliveries45–47 among female Wilms survivors exposed to these radiation fields.

Our study uniquely included assessments of mental health and neurocognitive function in this population not exposed to central nervous system (CNS) directed therapies. Current literature is mixed on the prevalence of mental health conditions in survivors of childhood cancer.5, 48–50 While some studies have reported that depression and anxiety at similar or even reduced rates compared to the general population, our analysis suggests Wilms survivors experience an increased mental health burden. Nearly a quarter reported symptoms consistent with depression and anxiety. An increased prevalence of moderate to severe impairments of executive function, processing speed, and memory was also observed. Neurocognitive impairment has been described in a smaller sample (n=158) of this same population and similarly did not identify treatment-related associations but did note associations with chronic health conditions.51 Our analysis expands the prior study by grading neurocognitive findings to quantify specific impairments more explicitly. In the absence of traditional treatment-related risk factors, such as CNS-directed therapies, we performed analyses investigating the possible impact of the presence of cardiopulmonary disease on neurocognitive function. Impairments in processing speed were associated with the presence of grade 2–4 cardiovascular disease. However, associations with other neurocognitive domains were not observed. Traditionally, only survivors exposed to CNS-directed therapies have been considered at risk for neurocognitive impairments, however, the overall burden and duration of chronic health conditions may also contribute. In an analysis from the CCSS, path analysis demonstrated direct effects of cardiopulmonary (RR 1.3 95% CI 1.1–1.4) and endocrine (RR 1.1 95% CI 1.0–1.3) conditions on impaired task efficiency.52 Research is needed to determine if early interventions may alter the trajectory of cognitive function in this aging population.

Across all four domains, survivors of non-white race experienced a relative risk of neurocognitive impairment two to three-fold that of white survivors (Supplemental Table 5a), suggesting a differential impact by race. This finding persisted when comparing non-white survivors to non-white controls alone (Supplemental Table 5b). Further research, including social determinants of health and the neurodevelopmental impact of age at treatment, is needed.

Studies of Wilms tumor survivors in the CCSS and British CCSS noted increased physical limitations assessed by self-report.5, 8 Using physical performance testing, we observed excess impairments in aerobic function, mobility, strength, endurance, and flexibility. Prior studies including smaller numbers of Wilms survivors have not observed these impairments.53, 54 Reports from SJLIFE have suggested that exposure to abdominopelvic radiotherapy may cause body composition changes that affect aerobic function, strength and endurance.55 In our study, there were no clear associations between these outcomes and treatment exposures. However, having a cardiac condition was associated with impairment in the aerobic function, strength, and endurance domains, which may have implications for physical and mental health. To our knowledge this is the largest and most comprehensive physical function assessment in Wilms survivors to date, suggesting this population may benefit from a formalized physical training intervention.

Despite systematic health assessments performed in SJLIFE, our study has some limitations. Thirty-seven percent of eligible survivors were not included in the analysis (Supplemental Figure 1) and differed from participants by age and race. Participation required returning to SJCRH, and some survivors who declined participation may have been excluded due to inability to travel; potentially under- or over-estimating the prevalence of conditions. Our findings may not be representative of younger survivors more recently diagnosed due to the limited recruitment to date of these individuals. Despite uniquely characterizing neurocognitive and physical performance, not all participants were able to complete this testing resulting in potential for bias.

Conclusion

Survivors of Wilms tumor experience an excess burden of chronic health conditions threatening quality of life and longevity. Neurocognitive and physical function impairments were more prevalent than anticipated, despite a lack of CNS-directed treatment. Focused health maintenance and surveillance for these unique health risks may provide opportunities for early intervention, with the goal of reducing morbidity and preservation of long-term health.

Supplementary Material

Article Summary.

Clinically assessed health impacts of curative cancer treatment are limited. We aimed to characterize the health and neurocognitive and physical function among Wilms tumor survivors.

What’s Known on This Subject

Clinical trials have established curative therapeutic regimens for children diagnosed with Wilms tumor yielding progressively higher five-year survival rates and a growing population of survivors. Knowledge of late health outcomes for these children has relied on registry and self-reported data.

What This Study Adds

Lacking clinically assessed details, studies may underestimate the presence of premature or subclinical health conditions among cancer survivors. This study comprehensively characterizes health conditions and neurocognitive and physical function among Wilms tumor survivors evaluated at St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital.

Funding/Support:

This study was supported by the National Cancer Institute: Cancer Center Support (CORE) Grant (CA21765) to St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (PI: Dr. Charles W. Roberts) and U01 CA195547 (MPI: Drs. Melissa M. Hudson and Kirsten K. Ness) and the American Lebanese Syrian Associate Charities (ALSAC), Memphis, TN.

Role of Funder/Sponsor (if any):

The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study.

Abbreviations:

- p

probability

- <

less than

- >

more than

- ≥

more than or equal to

- N

number

- %

percentage

- CCSS

Childhood Cancer Survivor Study

- CNS

central nervous system

- cGy

centigray

- CI

confidence interval

- CTCAE

Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events

- MCC

mean cumulative count

- mg/Dl

milligrams per deciliter

- NCI

National Cancer Institute

- RR

respiratory rate

- SD

standard deviation

- SIR

standardized incidence ratio

- SJCRH

St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital

- SJLIFE

St. Jude Lifetime

- SN

subsequent neoplasms

- vs

versus

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosures (includes financial disclosures): The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Clinical Trial Registration (if any): The study protocol is available at ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier, NCT00760656 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00760656). Statistical code is available upon request.

References

- 1.Ward E, DeSantis C, Robbins A, Kohler B, Jemal A. Childhood and adolescent cancer statistics, 2014. CA Cancer J Clin. 2014;64(2):83–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Green DM. The treatment of stages I-IV favorable histology Wilms’ tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22(8):1366–1372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oeffinger KC, Mertens AC, Sklar CA, et al. Chronic health conditions in adult survivors of childhood cancer. N Engl J Med 2006;355(15):1572–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mertens AC, Yasui Y, Neglia JP, et al. Late mortality experience in five-year survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer: the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19(13):3163–3172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Termuhlen AM, Tersak JM, Liu Q, et al. Twenty-five year follow-up of childhood Wilms tumor: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2011;57(7):1210–1216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cotton CA, Peterson S, Norkool PA, et al. Early and late mortality after diagnosis of wilms tumor. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(8):1304–1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Dijk IW, Oldenburger F, Cardous-Ubbink MC, et al. Evaluation of late adverse events in long-term wilms’ tumor survivors. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2010;78(2):370–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong KF, Reulen RC, Winter DL, et al. Risk of Adverse Health and Social Outcomes Up to 50 Years After Wilms Tumor: The British Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(15):1772–1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hogsholt S, Asdahl PH, Bonnesen TG, et al. Disease-specific hospitalizations among 5-year survivors of Wilms tumor: A Nordic population-based cohort study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2021;68(5):e28905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Howell CR, Bjornard KL, Ness KK, et al. Cohort Profile: The St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study (SJLIFE) for paediatric cancer survivors. Int J Epidemiol. 2021;50(1):39–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hudson MM, Ehrhardt MJ, Bhakta N, et al. Approach for Classification and Severity Grading of Long-term and Late-Onset Health Events among Childhood Cancer Survivors in the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26(5):666–674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Homack S, Riccio CA. Conners’ Continuous Performance Test (2nd ed.; CCPT-II). J Atten Disord. 2006;9(3):556–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fine EM, Delis DC. Delis–Kaplan Executive Functioning System. In: Kreutzer JS, DeLuca J, Caplan B, editors. Encyclopedia of Clinical Neuropsychology. New York, NY: Springer; 2011. p. 796–801. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tombaugh T, Rees L, McIntyre N. Normative data for the Trail Making Test. In: Spreen O, Strauss E, editors. Compendium of neuropsychological tests: administration, norms, and commentary. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1996. p. 540. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wechsler D Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. 3rd ed. San Antonio, TX: The Pyschological Association; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Delis DC, Karamer JH, Kaplan E, Ober BA. California Verbal Learning Test--Second Edition. 2nd ed. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lipkin DP, Scriven AJ, Crake T, Poole-Wilson PA. Six minute walking test for assessing exercise capacity in chronic heart failure. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1986;292(6521):653–655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Podsiadlo D, Richardson S. The timed “Up & Go”: a test of basic functional mobility for frail elderly persons. J Am Geriatr Soc 1991;39(2):142–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mathiowetz V, Kashman N, Volland G, Weber K, Dowe M, Rogers S. Grip and pinch strength: normative data for adults. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1985;66(2):69–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muscular weakness assessment: use of normal isometric strength data. The National Isometric Muscle Strength (NIMS) Database Consortium. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996;77(12):1251–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moseley AM, Crosbie J, Adams R. Normative data for passive ankle plantarflexion--dorsiflexion flexibility. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon). 2001;16(6):514–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shephard RJ, Berridge M, Montelpare W. On the generality of the “sit and reach” test: an analysis of flexibility data for an aging population. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1990;61(4):326–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nashner LM, Peters JF. Dynamic posturography in the diagnosis and management of dizziness and balance disorders. Neurol Clin. 1990;8(2):331–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kantor AF, Li FP, Janov AJ, Tarbell NJ, Sallan SE. Hypertension in long-term survivors of childhood renal cancers. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7(7):912–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iarussi D, Indolfi P, Pisacane C, et al. Comparison of left ventricular function by echocardiogram in patients with Wilms’ tumor treated with anthracyclines versus those not so treated. Am J Cardiol. 2003;92(3):359–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kochanek KD, Xu J, Arias E. Mortality in the United States, 2019. NCHS Data Brief. 2020(395):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74(10):e177–e232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Whelton PK, Carey RM, Aronow WS, et al. 2017 ACC/AHA/AAPA/ABC/ACPM/AGS/APhA/ASH/ASPC/NMA/PCNA Guideline for the Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Management of High Blood Pressure in Adults: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(19):e127–e248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.American Diabetes Association. 2. Classification and Diagnosis of Diabetes: Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes-2021. Diabetes Care. 2021;44(Suppl 1):S15–S33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Armstrong GT, Oeffinger KC, Chen Y, et al. Modifiable risk factors and major cardiac events among adult survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(29):3673–3680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levin A, Stevens PE, Bilous RW, et al. KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3(1):128–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Green DM, Wang M, Krasin MJ, et al. Long-term renal function after treatment for unilateral, nonsyndromic Wilms tumor. A report from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort Study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67(10):e28271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hostetter TH, Olson JL, Rennke HG, Venkatachalam MA, Brenner BM. Hyperfiltration in remnant nephrons: a potentially adverse response to renal ablation. Am J Physiol. 1981;241(1):F85–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Breslow NE, Lange JM, Friedman DL, et al. Secondary malignant neoplasms after Wilms tumor: an international collaborative study. Int J Cancer. 2010;127(3):657–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Children’s Oncology Group. Long-term follow-up guidelines for survivors of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancers, Version 5.0. http://www.survivorshipguidelines.org/. Published 2018. Updated Oct 2018. Accessed Jan 25, 2022.

- 36.Lange JM, Takashima JR, Peterson SM, Kalapurakal JA, Green DM, Breslow NE. Breast cancer in female survivors of Wilms tumor: a report from the national Wilms tumor late effects study. Cancer. 2014;120(23):3722–3730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moskowitz CS, Chou JF, Wolden SL, et al. Breast cancer after chest radiation therapy for childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(21):2217–2223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nottage K, McFarlane J, Krasin MJ, et al. Secondary colorectal carcinoma after childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(20):2552–2558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kalapurakal JA, Peterson S, Peabody EM, et al. Pregnancy outcomes after abdominal irradiation that included or excluded the pelvis in childhood Wilms tumor survivors: a report from the National Wilms Tumor Study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2004;58(5):1364–1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chemaitilly W, Li Z, Krasin MJ, et al. Premature Ovarian Insufficiency in Childhood Cancer Survivors: A Report From the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102(7):2242–2250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sklar CA, Mertens AC, Mitby P, et al. Premature menopause in survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(13):890–896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schuck A, Hamelmann V, Bramswig JH, et al. Ovarian function following pelvic irradiation in prepubertal and pubertal girls and young adult women. Strahlenther Onkol. 2005;181(8):534–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nicholson HS, Blask AN, Markle BM, Reaman GH, Byrne J. Uterine anomalies in Wilms’ tumor survivors. Cancer. 1996;78(4):887–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nussbaum Blask AR, Nicholson HS, Markle BM, Wechsler-Jentzch K, O’Donnell R, Byrne J. Sonographic detection of uterine and ovarian abnormalities in female survivors of Wilms’ tumor treated with radiotherapy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;172(3):759–763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Li FP, Gimbrere K, Gelber RD, et al. Outcome of pregnancy in survivors of Wilms’ tumor. JAMA. 1987;257(2):216–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Green DM, Lange JM, Peabody EM, et al. Pregnancy outcome after treatment for Wilms tumor: a report from the national Wilms tumor long-term follow-up study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(17):2824–2830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Green DM, Peabody EM, Nan B, Peterson S, Kalapurakal JA, Breslow NE. Pregnancy outcome after treatment for Wilms tumor: a report from the National Wilms Tumor Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20(10):2506–2513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zeltzer LK, Recklitis C, Buchbinder D, et al. Psychological status in childhood cancer survivors: a report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(14):2396–2404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Michel G, Brinkman TM, Wakefield CE, Grootenhuis M. Psychological Outcomes, Health-Related Quality of Life, and Neurocognitive Functioning in Survivors of Childhood Cancer and Their Parents. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2020;67(6):1103–1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Foster RH, Hayashi RJ, Wang M, et al. Psychological, educational, and social late effects in adolescent survivors of Wilms tumor: A report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. Psychooncology. 2021;30(3):349–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tonning Olsson I, Brinkman TM, Hyun G, et al. Neurocognitive outcomes in long-term survivors of Wilms tumor: a report from the St. Jude Lifetime Cohort. J Cancer Surviv. 2019;13(4):570–579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cheung YT, Brinkman TM, Li C, et al. Chronic Health Conditions and Neurocognitive Function in Aging Survivors of Childhood Cancer: A Report from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2018;110(4):411–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hoffman MC, Mulrooney DA, Steinberger J, Lee J, Baker KS, Ness KK. Deficits in physical function among young childhood cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(22):2799–2805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hartman A, Pluijm SMF, Wijnen M, et al. Health-related fitness in very long-term survivors of childhood cancer: A cross-sectional study. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2018;65(4). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wilson CL, Liu W, Chemaitilly W, et al. Body Composition, Metabolic Health, and Functional Impairment among Adults Treated for Abdominal and Pelvic Tumors during Childhood. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2020;29(9):1750–1758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.