Abstract

Racial minority men and women face a wide variety of appearance-related pressures, including ones connected to their cultural backgrounds and phenotypic features associated with their identity. These body image concerns exist within a larger context, wherein racial minorities face pressures from multiple cultures or subcultures simultaneously to achieve unrealistic appearance ideals. However, limited research has investigated racial differences in the relationships between theorized sociocultural risk factors and body image in large samples. This study tests pathways from an integrated sociocultural model drawing on objectification theory and the tripartite influence model to three key body image outcomes: appearance evaluation, body image quality of life, and face image satisfaction. These pathways were tested using multigroup structural equation modeling in a national sample of White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian men and women (ns = 205–4797 per group). Although many hypothesized associations were similar in strength across groups, race moderated some of the pathways between sociocultural pressures (media, peer, family), internalization of appearance ideals (thin-ideal, muscular/athletic), appearance surveillance, and body image outcomes. Findings support the likely role of both shared and specific risk factors for body image outcomes, suggesting avenues for tailoring adapted interventions in order to target culturally-salient risk factors.

Keywords: Body image, race, Objectification theory, Tripartite influence model, Face satisfaction

1. Introduction

“I feel like for girls who are Asian and live in the United States there’s already this [problem]- ‘cause I know when I was younger … I lived in Kansas, and … I was a minority and there were so many girls that were White and pretty and skinny, and it’s just like I’m not White, I have to be pretty and skinny” – Participant quoted in Javier and Belgrave (2019).

Racial minority men and women face a wide variety of appearance-related pressures, including unique pressures connected to their cultural backgrounds and to the phenotypic features associated with their racial group (Franko et al., 2013). Sociocultural frameworks propose that individual and cultural differences in appearance-related pressures confer differential risk for body image concerns, which partially accounts for observed differences in body image disturbance among racial groups within the United States (Frederick et al. 2020; Grabe & Hyde, 2006; Roberts, Cash, Feingold, & Johnson, 2006; Schaefer, Thibodaux, et al., 2015; Wildes, Emery, & Simons, 2001).

Research applying sociocultural frameworks to explore body image among diverse samples is emerging, but this work has been limited to date by generally small sample sizes, which limits statistical power to examine the experiences of racial minorities, and this is particularly true for examining minority men. Although the current study faced the limitation of relying on broad categories that encompass many different identities, such as many different groups within the categories “Asian” or “Hispanic,” we had the rare opportunity to highlight racial differences and similarities in the pathways from sociocultural appearance pressures to different aspects of body image satisfaction. The aim of this study was therefore to extend research in this area by examining racial differences in an integrated sociocultural framework based on two widely used sociocultural models of body image: the tripartite influence model (Thompson, Heinberg, Altabe, & Tantleff-Dunn, 1999) and one grounded in objectification theory (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997). Constructs derived from the tripartite influence model and objectification theory were used to predict body image outcomes across different racial groups among men and among women.

1.1. Sociocultural Models of Body Image

1.1.1. Tripartite Influence Model

The tripartite influence model proposes that individuals experience pressure from socializing agents (e.g., media, family, peers) to pursue gendered appearance ideals (i.e., thinness for women; leanness and muscularity among men (Thompson et al., 1999). For example, people experience appearance- or weight-related teasing from peers or family members, which communicates information about valued appearance ideals (Menzel et al. 2010). In response to increasing sociocultural pressures, the tripartite influence model proposes that individuals begin to “internalize,” or integrate these appearance ideals into their sense of self, ultimately resulting in body dissatisfaction when individuals feel that their own appearances do not match the ideal. Existing research suggests the relevance of appearance pressures and appearance ideal internalization to body image for males and females (Keery, Van den Berg, & Thompson, 2004; Tylka, 2011), as well as the potential influence of race on the strength of the relationships proposed within the tripartite model (Rakhkovskaya & Warren, 2016). However, limited research has examined the full model across large samples of men and women from different racial backgrounds.

1.1.2. Objectification Theory

Objectification theory provides a complementary framework for understanding the cultural and individual processes that contribute to group differences in body image concerns. Originally developed to explain the high rates of body image and eating disturbance observed among women, objectification theory employs a gendered lens to acknowledge that women are highly sexualized and objectified (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997). For example, mass media routinely feature sexualized images of women (Kozee, Tylka, Augustus-Horvath, & Denchik, 2007), though other forms of sexual objectification may include sexually degrading jokes or comments, sexualized gaze, or sexual violence. The theory proposes that this sexualization heightens women’s concerns about how their bodies appear to others, which encourages them to engage in routine “surveillance” (monitoring) of how they appear to others. Increased surveillance is then thought to produce poorer body image (i.e., body shame), in part because it draws women’s attention to perceived flaws in their appearance. Objectification theory is supported by research indicating that exposure to sexualized media images has a temporary negative impact on women’s body image (Frederick, Daniels, Bates, & Tylka, 2017), and numerous studies demonstrating a positive association between body surveillance and indices of body image (Frederick, Forbes, Grigorian, & Jarcho, 2007; Rodgers, Chabrol, & Paxton, 2011; Tylka & Hill, 2004).

There is reason to expect that the relationships posited by objectification theory may differ across racial groups because objectification and sexualization experiences vary by racial group. Some aspects of sexualization faced by Asian women are different than those faced by Black women, whose experiences differ from Hispanic women, who differ from White women. Common stereotypes of Asian American women often involve notions ranging from expectations of being docile and subservient, but also erotic and sensual (Kawahara & Fu, 2007). In a focus group study, Asian American were asked about their experiences related to their racial identity, and about the assumptions people make about them based on their race. One common theme that emerged was experiences of be exoticized, objectified, or fetishized (Mukkamala & Suyemoto, 2018).

Black women have long faced the Jezebel stereotype of being highly sexual and using sex to manipulate men (Jewell, 1993), and Black women are often portrayed as sexual objects in some forms of media (Ward, Rivadeneyra, Thomas, Day, & Epstein, 2013). Women of all racial backgrounds are at risk of facing objectification, but the Jezebel stereotype is tied to a long history of justifying racism and sexual violence against Black women. The Jezebel stereotype emphasizes a cluster of beliefs about Black women being “gold-diggers,” “more promiscuous (fast) than other women,” “sexually uninhibited,” willing to “use sex to get what they want,” and out to “steal your man” (Cheeseborough, Overstreet, & Ward, 2020). Hispanic women have long been stereotyped as being sexually available, skilled, desirable, and passionate, with particular focus on curvy body and large buttocks as represented by celebrities such as Jennifer Lopez (Guzman & Valdivia, 2004). Past research has found that Hispanic women are more often presented in a sexualized manner in popular media than White women (Rivadeneyra & Ward, 2005). As with Black women, Hispanic women have often been stereotyped as sexually promiscuous (Lundström, 2006). White women are presented as the norm, idealized, and sexualized in mainstream media, which on the one hand may offer a feeling of prestige and confidence, but on the other hand allows for direct interethnic comparisons between one’s own body and the dominant ideals.

Notably, men also face sexual objectification. For example, muscular and toned male bodies are often hypersexualized in popular media (Burch & Johnsen, 2020; Frederick, Fessler, & Haselton, 2005; Lawrence, 2016), many women report attraction to toned and muscular men (Frederick & Haselton, 2007) and heterosexual men report wanting to become more muscular in order to be more attractive to women (Frederick, Buchanan, et al., 2007). Consistent with objectification theory, multiple studies have found that surveillance is often associated with lower body satisfaction among men (Davids, Watson, & Gere, 2019; Frederick, Forbes, et al., 2007; Girard, Chabrol, & Rodgers, 2018; Tylka & Andorka, 2012). However, additional work is needed to clarify the role of body surveillance in relation to other sociocultural processes among diverse groups of men.

Racialized objectification of men’s bodies is less explored, but has tended to focus on the hypersexualization of Black men and stereotype that Black men are more sexual and promiscuous (Allen, 2021). These stereotypes connect to the idea that race has been gendered – that Black men are viewed as atypically masculine and that Asian men are viewed as atypically feminine (Galinsky, Hall, & Cuddy, 2013), which then connects to stereotypes of Asian men as less being sexy (Wong, Owen, Tran, Collins, & Higgins, 2012). Hispanic men in the popular media are often stereotyped as being masculine and passionate lovers, but these representations occur in a cultural context in the U.S. where Hispanic men also commonly face negative racist stereotypes (Ghavami & Peplau, 2013). Finally, mainstream media often features White men as sexually appealing, particularly athletic White men. These different stereotypes and objectification pressures faced by men and women of different racial groups highlight the importance of understanding pathways connecting sociocultural appearance pressures to body surveillance to body satisfaction.

1.1.3. Integrated Sociocultural Model of Body Image

Although both the tripartite influence model and objectification theory have demonstrated great utility in identifying factors associated with body image outcomes, the constructs are often tested in isolation from each other rather than together in the same study. To help connect these perspectives, Fitzsimmons-Craft (2011) proposed that body surveillance can be a consequence of appearance-ideal internalization. Existing research among college women has produced conflicting results, with some research findings that body surveillance mediated the relationship between thin-ideal internalization and body dissatisfaction (Fitzsimmons-Craft et al., 2012), and other research not replicating this pattern (Fitzsimmons-Craft, 2014). Continued examination of this integrated model, including consideration of muscular-ideal internalization and thin-ideal internalization among men and women from different racial backgrounds would benefit the field’s understanding of the ways in which inter- and intrapersonal experiences identified in sociocultural models may operate in confluence.

1.2. Racial Similarities and Differences in Body Satisfaction and Sociocultural Pressures

To date, the tripartite and objectification models have been generally been tested on relatively young and predominantly White samples (Moradi, 2010; Moradi & Huang, 2008). In recent years, increasing efforts have been made to bridge the gaps in our understanding of how body image concerns present and develop in diverse samples (Cheney, 2011; Frederick, Forbes, et al., 2007; Sabik, Cole, & Ward, 2010). These efforts have involved first trying to document the relative prevalence of body image concerns across racial groups, and testing whether sociocultural factors operate similarly or differently among these groups.

In meta-analyses, levels of overall body satisfaction are generally similar among Asian, White, and Hispanic women (Grabe & Hyde, 2006; Roberts et al., 2006). A consistent theme, however, is that Black women report higher body satisfaction than Whites, although the overall effect sizes are small (Frederick et al., 2020; Grabe & Hyde, 2006; Roberts et al., 2006; Schaefer & Thibodaux et al., 2015; Wildes et al., 2001). In addition, several large studies have found systematic differences between White and Asian women in their evaluation of specific aspects of their appearance (Frederick, Forbes, et al., 2007; Forbes & Frederick, 2008; Frederick, Kelly, Latner, Sandhu, & Tsong, 2016). Specifically, Asian women evidence greater dissatisfaction with their breasts and facial features compared to White women (Frederick, Kelly, et al., 2016). Turning to men, sparse data and mixed results preclude the ability to make strong conclusions regarding racial differences among men (Frederick et al., 2020).

Regarding appearance surveillance more specifically, some research suggests similar levels between Whites, Asians, and Hispanics (Frederick, Forbes et al., 2007), whereas other research has identified some small differences between these groups (Claudat, Warren, & Durette, 2012; Frederick, Kelly, et al., 2016). The one fairly consistent finding has been that Black women report lower surveillance than White women (Breitkopf, Littleton, & Berenson, 2007; Claudat et al., 2012; Hebl, King, & Lin, 2004; for mixed results, see Fitzsimmons & Bardone-Cone, 2011). Similarly, Black women report less internalization of media ideals than White women (Cashel, Cunningham, Landeros, Cokley, & Muhammad, 2003; Quick & Byrd-Bredbenner, 2014; Rakhkovskaya & Warren, 2014; Warren, Gleaves, Cepeda‐Benito, Fernandez, & Rodriguez‐Ruiz, 2005; Warren, Gleaves, & Rakhkovskaya, 2013), with results being more mixed in studies comparing other groups (Frederick, Kelly, et al., 2016; Hermes & Keel, 2003; Warren et al., 2005; Warren et al., 2013). Thus, among women, the most consistent group differences to emerge are those among Black women who report more positive body image than their peers from other backgrounds. Data on men is not sufficient to make any strong conclusions about racial similarities or differences (Frederick, Forbes, et al., 2007).

1.3. Links Between Sociocultural Constructs and Body Satisfaction Across Racial Identity Groups

The similarities and differences in body image experiences across racial groups have raised speculations about the appearance-related pressures faced by different racial groups, and whether constructs in existing body image models apply similarly across these groups. For example, the underrepresentation of racial minorities in mainstream media may impact both appearance pressures and the internalization of beauty ideals (Bowen & Schmid, 1997; Duke, 2000; Franko et al., 2013). This impact could be positive for racial minorities who may dismiss media appearance pressures or ideals as less relevant, or negative for racial minorities who feel the phenotypes represented as prestigious in popular media differ substantially from their own. Furthermore, racist stereotypes connected to appearance-oriented and objectifying experiences may increase the negative impacts of these experiences on body image among racial minorities (Beltran, 2002; Rubin, Fitts, & Becker, 2003; Taylor & Stern, 1997). Finally, body image ideals communicated within racial subcultures can vary from mainstream media ideals. For example, beauty ideals among Black and Latina women often encompass more shapely figures compared to White women (Capodilupo, 2015; Franko et al., 2012), and non-White groups place greater emphasis on dimensions of body image unrelated to weight, such as facial features (Frederick, Kelly, et al., 2016) and hair (Capodilupo, 2015).

Despite these cultural differences, most of the existing research confirms the expected links between proposed upstream variables implicated in sociocultural theories (e.g., internalization, appearance surveillance) and proposed downstream outcomes (i.e., body image) in distinct racial groups (Boie, Lopez, & Sass, 2013; Buchanan, Fischer, Tokar, & Yoder, 2008; Frederick, Forbes, et al., 2007; Javier & Belgrave, 2015; Nouri, Hill, & Orrell-Valente, 2011; Phan & Tylka, 2006; Rakhkovskaya & Warren, 2016; Watson, Robinson, Dispenza, & Nazari, 2012; Wood, Nikel, & Petrie, 2010). However, a small body of research also indicates that the strength of some proposed pathways may differ across select groups (Burke et al., 2021; Boie et al., 2013; Schaefer et al. 2018), suggesting racial differences in the potency of posited risk factors. For example, although the overall model functioned well for Black, Latina, White, and Asian women, Burke et al. (2021) found that some pathways were weaker for Black women, with the most notable difference being that media pressures were less strongly linked to thin ideal internalization. Importantly, this work is limited by relatively small sample sizes and a general focus on women, with no comparable cross-ethnic examinations among men. Therefore, continued research using large samples of men and women is needed to clarify the utility of these models for different racial groups, as such work may have important implications for culturally-adapted interventions.

1.4. Aims and Research Questions

To address this need, we tested an integrated sociocultural model of body image across large samples of White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian participants using multi-group structural equation modeling (SEM). In the proposed model, we hypothesized pathways from three sources of appearance pressure (i.e., peer, media, and family) to both thin- and muscular-ideal internalization. Internalization of appearance ideals were then hypothesized to demonstrate pathways to body surveillance, consistent with other integrative theoretical models (Fitzsimmons-Craft, 2011). In an effort to extend prior research that has commonly focused on pathological body image, we examined positive appearance evaluation and body image quality of life (i.e., the degree to which body image favorably impacts various domains of functioning such as interpersonal relationships and day-to-day emotions, Cash & Fleming, 2002) as outcomes. These models were generally supported in previous analyses of this dataset for women (Frederick, Tylka, Rodgers, Pennesi, et al., 2022) and men overall (Frederick, Tylka, Rodgers, Convertino, et al., 2022), whereas here we focus on racial group differences and similarities in these pathways.

We also included a diverse set of body image outcomes. Consistent with other research, we investigated people’s overall appearance evaluation (Cash, 2000), but this is the first study to examine racial differences in the predictors of body image-specific quality of life, which focuses on people’s perceptions of the positive and negative impacts of their body image on aspects of their life (Cash & Fleming, 2002). This allows to focus not only on negative outcomes such as body dissatisfaction, but also the more positive aspects of body image. Furthermore, we also examined “face image satisfaction,” which is defined as “individuals’ perceptions of and attitudes towards their own face, especially its appearance, which includes evaluation/affect (face image appraisals and satisfaction, as well as discrete emotional experiences vis-à-vis one’s face) and investment in one’s facial appearance (the salience, centrality, or extent of cognitive-behavioral emphasis on the appearance of one’s face, including ‘facial appearance schematicity’)” (Frederick, Kelley et al., p. 115). This construct is not often explored in body image research, but has important ties to race and appearance self-concept (Frederick, Kelly, et al., 2016; Warren, 2012).

We hypothesized significant pathways from body surveillance and both thin- and muscular-ideal internalization to appearance evaluation and body image quality of life. Finally, we expected significant pathways from each source of appearance pressure to body surveillance, and a pathway from body surveillance to face satisfaction. Given research suggesting racial group differences in this domain (Warren, 2012), we also examined general appearance pressures and appearance surveillance as predictors of face satisfaction. Based on limited evidence from previous studies, we anticipated that some model pathways from sociocultural appearance concerns to body image outcomes may vary across racial groups (e.g., Asian women might be particularly impacted by family pressures; Frederick, Kelly, et al., 2016), but our analyses were primarily exploratory. Due to the fact that some aspects of men’s and women’s appearance concerns can differ on average, such as in concerns over thinness versus muscularity, we examined the pathways separately by gender.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Data were drawn from the U.S. Body Project I, described in detail below in the Procedure section. The sample was restricted to include only participants who completed the full survey and who fit the following criteria: (a) reported currently living in the United States; (b) completed all key body image items; (c) were aged 18–65; (d) had body mass indexes (BMI) ranging from 14.50 to 50.50 based on self-reported height and weight. Age and BMI restrictions were placed on the sample to prevent outliers or mis-entered values from having undue influence on the effect size estimates. A total of 13,518 people clicked on the survey, 12,571 answered the first question, and 12,151 completed the full survey. After applying the inclusion criteria, this created the base dataset for The U.S. Body Project I of 11,620 participants. The data was collected in separate postings throughout 2016 in January, February, April, and September. For more detailed demographics and a discussion of how the current sample compares to nationally representative datasets, please see Frederick and Crerand, et al. (2022).

We then further restricted the sample to include only participants who self-identified as White, Black, Hispanic, or Asian and this was their sole identity (e.g., someone identifying as White and Black would be excluded). Different research traditions and researchers from different countries have different norms for labelling these groups, with some distinguishing “ethnicity” from “race,” some eliminating the term race and relying solely on “ethnicity,” some relying solely on the term “race,” some using a hybrid of “race/ethnicity,” and some referring to these groupings as “racial identities.” The authorship team had a diverse set of views on the appropriate terminology. For brevity, we primarily rely on the term “race” throughout this manuscript to refer to these different identities, with the recognition that in some research traditions appropriate terminology differs. We also added a follow-up question for Asian participants about their cultural backgrounds because we were considering a follow-up study in a geographical region with a large Asian population. Asian participants indicated the following identities: Chinese (32.1%), Korean (12.6%), Vietnamese (11.5%), Japanese (6.3%), Filipino (12.6%), Indian (9.9%), Taiwanese (3.1%), Thai (1.8%), Pakistani (1.4%), Cambodian (1.1%), None of the above (4.2%), More than one above (3.1%), and no response (0.3%).

The aforementioned racial groups (Black, Hispanic, White, Asian) were included in the analyses because these were the only groups that self-identified with a single demographic group and met or came very close to meeting the suggested minimum sample size of 200 for SEM (Kelloway, 2015). After applying this additional inclusion criterion, the analytic sample comprised 4877 men and 5823 women for a total of 10,700 participants. Key demographic characteristics of the sample are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics.

| Men (N = 4877) | Women (N = 5823) | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Mean (SD) | ||

| Age (years) | 33.22 (10.00) | 35.33 (11.28) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.49 (5.64) Percent (N) |

27.69 (6.85) |

| Race | ||

| White | 80.9 (3945) | 82.4 (4797) |

| Black | 6.1 (297) | 8.2 (477) |

| Hispanic | 5.4 (265) | 3.5 (205) |

| Asian | 7.6 (370) | 5.9 (344) |

Note. SD = standard deviation; BMI = body mass index.

2.2. Procedure and Overview of The U.S. Body Project I

The first author’s university institutional review board approved the study. Adult participants were recruited via Amazon Mechanical Turk, a widely used online panel system used by researchers to access adult populations (Berinsky, Huber, & Lenz, 2012, Buhrmester, Kwang, & Gosling, 2011, Kees, Berry, Burton, & Sheehan, 2017; Paolacci, Chandler, & Ipeirotis, 2010; Robinson, Rosenzweig, Moss, & Litman, 2019). Participants were paid 51 cents for taking the survey. The survey was advertised with the title “Personal Attitudes Survey” and the description explained that “We are measuring personal attitudes and beliefs. The survey will take roughly 10–15 min to complete.” The general wording of the advertisement was used to avoid selectively recruiting people particularly interested in body image. After clicking on the advertisement, the participants read a consent form providing more details about the content of the study, including that it would contain items related to sex, love, work, and appearance. They were then given the option to continue with the survey or exit.

After providing informed consent, participants completed the numerical textbox questions (e.g., hours per week worked, number of times in love, sex frequency per week, longest relationship), followed by measures assessing appearance evaluation (Cash, 2000), appearance ideal internalization and pressures (Schaefer et al., 2015), face satisfaction (Frederick, Kelly, et al., 2016), overweight preoccupation (Cash, 2000), body image quality of life (Cash & Fleming, 2002), body surveillance (McKinley & Hyde, 1996), and finally demographics.

This manuscript is part of a series of papers emerging from The U.S. Body Project I. This project invited over 20 body image and eating disorder researchers, four sexuality researchers, and six computational scientists to apply their content and data-analytic expertise to the dataset. This project resulted in the following set of 11 papers for this special issue.

The first two papers examine how demographic factors (gender, sexual orientation, BMI, age, race) are related to body satisfaction and overweight preoccupation (Frederick, Crerand, et al., 2022) and to measures derived from objectification theory and the tripartite influence model, including body surveillance, thin-ideal and muscular/athletic ideal internalization, and perceived peer, family, and media pressures (Frederick, Pila, et al., 2022). The second set of papers examine how these measures and demographic factors predict sexuality-related body image (Frederick, Gordon, et al., 2022) and face satisfaction (Frederick, Reynolds, et al., 2022).

The third set of papers use structural equation modelling to examine the links between sociocultural appearance concerns and body satisfaction among women and across BMI groups (Frederick, Tylka, Rodgers, Pennesi, et al., 2022), among men and across different BMI groups (Frederick, Tylka, Rodgers, Convertino, et al., 2022), across racial groups (current paper) and across sexual orientations (Frederick, Hazzard, Schaefer, Rodgers, et al., 2022).

The fourth set of papers focus on measurement issues by examining measurement invariance of the scales across different demographic groups (Hazzard, Schaefer, Thompson, Rodgers, & Frederick, 2022) and conducting a psychometric evaluation of an abbreviated version of the Body Image Quality of Life Inventory (Hazzard, Schaefer, Thompson, Murray, & Frederick, 2022). Finally, the last paper uses machine learning modeling to compare the effectiveness of nonlinear machine learning models versus linear regression for predicting body image outcomes (Liang et al., 2022).

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-4

Participants completed the Sociocultural Attitudes Towards Appearance Questionnaire-4 (SATAQ-4; Schaefer et al., 2015), which measures appearance pressures and appearance ideal internalization. This measure contains five subscales assessing perceived appearance pressures from family, peers, and media (4 items each), as well as internalization of the thin ideal and muscular ideal. An example of a pressure item was “I feel pressure from the media to look in better shape.”

The thin-ideal internalization subscale consists of five items, but one item was inadvertently omitted (“I want my body to look like it has little fat”), leading us to utilize the remaining four items (e.g., “I want my body to look very thin”) among women. However, given that men may desire to have low body fat but do not typically endorse wanting to be thin (Ridgeway & Tylka, 2005), we used one item assessing desire for leanness (“I want my body to look very lean”) and one item assessing desire for low body fat (“I think a lot about having very little body fat”) to estimate lean-ideal internalization instead of thin-ideal internalization among men.

While the muscular/athletic internalization subscale includes five items, three items are cognitive (e.g., “It is important for me to look athletic,” “I think a lot about looking muscular,” and “I think a lot about looking athletic”) and two are behavioral (“I spend a lot of time doing things to look more muscular,” “I spend a lot of time doing things to look more athletic”). To be consistent with the thin-ideal internalization measure that assesses only cognitive aspects of this internalization, we selected only the three cognitive items from the muscular-ideal internalization measure. Responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Definitely Disagree; 5 = Definitely Agree). Higher subscale scores indicated greater levels of perceived pressures or internalization. Cronbach’s α was ≥ 0.84 for all subscales in all racial groups among women, and α ≥ 70 for all subscales in all racial groups among men except for the two-item lean-ideal internalization subscale among Black men (α = 0.65) and Asian men (α = 0.69).

2.3.2. Objectified Body Consciousness Scale - Body Surveillance Subscale

The 8-item Surveillance subscale of the Objectified Body Consciousness Scale (OBCS-Surveillance; McKinley & Hyde, 1996) assessed the extent to which participants monitor how they appear to others (e.g., “During the day, I think about how I look many times”). Responses were recorded on a 7-point Likert agreement scale with response options ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 7 (Strongly Agree), where higher scores indicate greater levels of surveillance. Cronbach’s α was ≥ 0.81 in all racial groups among women, and α ≥ 0.75 in all racial groups among men.

2.3.3. Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire - Appearance Evaluation Subscale

The 7-item Appearance Evaluation subscale of the Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ- Appearance Evaluation; Brown, Cash, & Mikulka, 1990; Cash, 2000) was used to measure feelings of physical attractiveness and satisfaction with one’s appearance (e.g., “I like my looks just the way they are”). Responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale with response options ranging from 1 (Definitely Disagree) to 5 (Definitely Agree), where higher scores indicate more positive evaluations of appearance. Cronbach’s α was ≥ 0.92 in all racial groups among women, and α ≥ 0.91 in all racial groups among men.

2.3.4. Body Image Quality of Life Inventory

The 19-item Body Image Quality of Life Inventory (BIQLI; Cash & Fleming, 2002), assessed participant’s beliefs about how their bodies affect their lives. Participants indicated whether their feelings about their bodies had positive, negative, or no effects on various aspects of their lives (e.g., “My day-to-day emotions,” “How confident I feel in my everyday life”). Participants responded on a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Very Negative Effect) to 7 (Very Positive Effect), where higher scores represent more positive perceived effects of body image on quality of life. Cronbach’s α was ≥ 0.96 in all racial groups among women and men.

2.3.5. Face Image Satisfaction Measure

Participants completed the Face Image Satisfaction Measure (Frederick, Kelly, et al., 2016), which assesses how happy people feel with their face overall and specific aspects of their face. This scale contains four items. Three of them begin with the stem, “I feel happy with the appearance of my…” followed by aspects of the face (face overall, nose, eyes). The final item reads, “I am happy with the shape of my face.” Participants responded on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Definitely Disagree to 5 = Definitely Agree), with higher averaged scores indicating greater face satisfaction; α ≥ 0.81 for all subscales in all racial groups among women, and α ≥ 0.85 for all subscales in all racial groups among men.

2.3.6. Demographics

Participants self-reported their gender, race, sexual orientation, age, height in feet and inches, and weight in pounds. For the race item, participants were asked “What is your ethnicity? Check all that apply” and were given the options: White, Hispanic, Black/African-American, Asian, Arab, Indian, Native American, Middle Eastern, Pacific Islander, and Other (please specify). If they were Asian or Asian American, they were asked a follow-up question to indicate their specific cultural background: Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, Cambodian, Taiwanese, Filipino, Thai, Pakistani, India, None of the above, or More than one above. BMI was calculated using the self-reported height and weight data.

2.4. Data Analysis

Descriptive statistics and internal consistency were computed with SPSS 25. Latent variable SEM was conducted using Mplus 8.3. The sample contained only participants that completed the full survey; thus, there were no missing data. Estimation via weighted least squares with mean and variance adjustment (WLSMV) was used for SEM as has been recommended for ordinal data (Brown, 2015), and the Mplus DIFFTEST procedure (the χ2 difference test for WLSMV estimation) was used to compare nested models.

2.4.1. Overarching Models

Models predicting appearance evaluation and body image quality of life were previously identified for women (Frederick, Tylka, Rodgers, & Pennesi, et al., 2021) and men (Frederick, Tylka, Rodgers, & Convertino, et al., 2021) in the U.S. Body Project I. For models predicting face satisfaction, only items related to general appearance rather than body-specific items were used to represent appearance pressures, appearance ideal internalization, and body surveillance. Accordingly, single items were used to represent family appearance pressure, peer appearance pressure, and media appearance pressure (I feel pressure from [family members] / [media] / [peers] to improve my appearance). The thin-ideal internalization and muscular-ideal internalization subscales were not used. Four of the eight OBCS- Surveillance items were used (“I rarely think about how I look,” “I rarely compare how I look with how other people look,” and “During the day I think about how I look many times”).

Therefore, a combination of observed and latent variables were utilized for path analyses in which family appearance pressure, peer appearance pressure, and media appearance pressure are linked with appearance surveillance and face satisfaction, and appearance surveillance is linked with face satisfaction. Single-group SEM analyses were conducted to assess the fit of the face satisfaction models in men and women. Measurement models with all constructs across models were then conducted in men and women.

2.4.2. Assessing Model Fit

Adequacy of model fit was judged by the following fit indices: comparative fit index (CFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), and standardized root-mean square residual (SRMR). Values ≥ 0.95 for CFI, ≤ 0.06 for RMSEA, and ≤ 0.08 for SRMR indicate good model fit (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Values of.90 or higher for CFI, up to.10 for RMSEA, and up to.10 for SRMR indicate acceptable but mediocre model fit (Bentler, 1990; Browne & Cudeck, 1993; Hu & Bentler, 1995; MacCallum, Browne, & Sugawara, 1996; Schermelleh-Engel & Müller, 2003). Models were deemed to have adequate fit if most fit indices suggested acceptable fit.

2.4.3. Testing for Racial Differences in Models Predicting Appearance Evaluation, Body Image Quality of Life, and Face Satisfaction

Following examination of the measurement models in men and women, multi-group SEM analyses were then conducted to test for racial differences in models predicting appearance evaluation, body image quality of life, and face satisfaction. In the first step, all structural paths were free to vary for each racial group (fully variant model). Then, all structural paths were constrained across racial groups (fully invariant model). A chi-square difference test between the fully variant and fully invariant models was used to determine whether at least one pathway differed by race. Chi-square difference tests were then used to compare the fully invariant model with models that relaxed one pathway at a time for all ethnic groups. For pathways that differed by race at a significance level of.05, chi-square difference tests were used to compare fully invariant models with models that relaxed those pathways one at a time for White versus Black, White versus Hispanic, White versus Asian, Black versus Hispanic, Black versus Asian, and Hispanic versus Asian participants. Significance thresholds were corrected for multiple comparisons using False Discovery Rate (FDR) procedures (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995) with an FDR of Q = 0.10; all results with p’s < 0.05 retained significance with this correction.

3. Results

3.1. Measurement Models

The measurement models provided adequate fit to the data among women (CFI =0.934, RMSEA =0.084 with 90% CI =0.083–0.084, SRMR =0.052) and men (CFI =0.929, RMSEA =0.079 with 90% CI =0.078–0.079, SRMR =0.052).

3.2. Structural Models

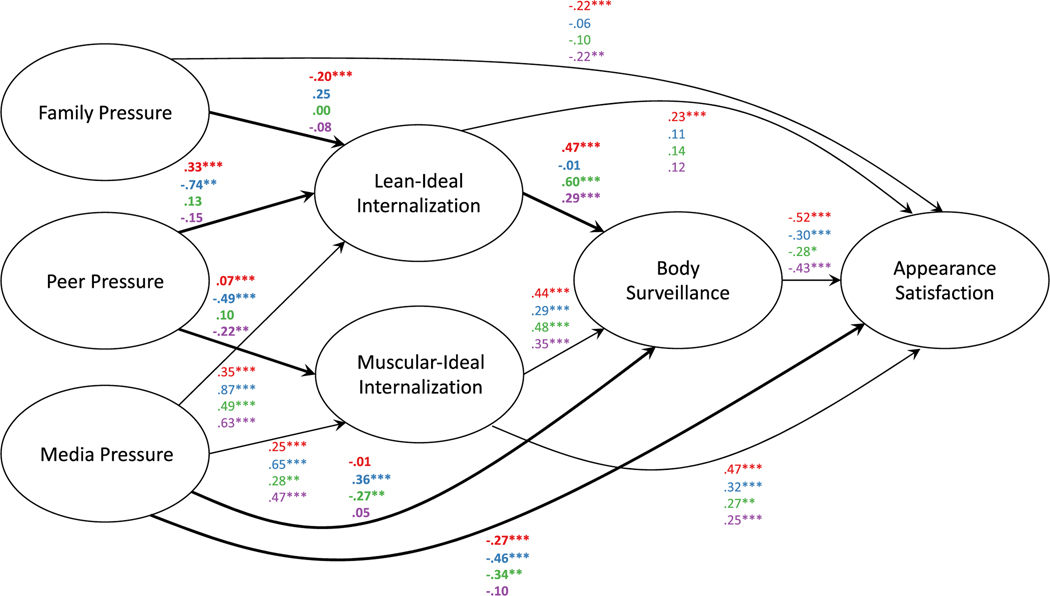

3.2.1. Racial Differences and Similarities in Appearance Evaluation Model among Women

Among women, the fully variant structural model predicting appearance evaluation demonstrated adequate fit (CFI =0.981, RMSEA =0.065 with 90% CI =0.064–0.065, SRMR =0.058) and significantly better fit than the fully invariant model, Δχ2(39, N = 5823) = 146.21, p < .001, indicating that at least one path differed in strength between racial groups. Fig. 1 presents standardized path estimates for each racial group from the fully variant model predicting appearance evaluation among women. Ten paths were found to significantly differ by race; these paths are bolded in Fig. 1, and the racial differences observed for each of these paths are described below.

Fig. 1.

Multi-group structural equation model estimates for appearance evaluation by race among women. Appearance evaluation is labeled here as “appearance satisfaction” to denote that higher scores indicate more positive body image. Standardized path estimates are listed in the following order: White (red font), Black (blue font), Hispanic (green font), Asian (purple font). Paths that significantly differed between racial groups are bolded. Arrows for nonsignificant pathways are not shown. * p < .05, * * p < .01, * ** p < .001.

3.2.1.1. Racial Differences in Paths to Internalization of Appearance Ideals.

The path from family appearance pressures to thin-ideal internalization differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 5823) = 9.81, p = .02; compared to White women, this path was significantly stronger for Black women, Δχ2(1, N = 5274) = 4.26, p = .04, and Asian women, Δχ2(1, N = 5141) = 8.74, p = .003.

The path from media appearance pressures to thin-ideal internalization also differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 5823) = 10.70, p = .01; this path was significantly stronger for Asian women compared to White women, Δχ2(1, N = 5141) = 13.01, p < .001, Black women, Δχ2(1, N = 821) = 4.41, p = .04, and Hispanic women, Δχ2(1, N = 549) = 5.75, p = .02.

3.2.1.2. Racial Differences in Paths to Body Surveillance.

The path from media appearance pressures to body surveillance differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 5823) = 12.93, p = .005; this path was significantly stronger for White women compared to Black women, Δχ2(1, N = 5274) = 11.47, p < .001, and for Asian women compared to Black women, Δχ2(1, N = 821) = 5.67, p = .02.

The path from thin-ideal internalization to body surveillance also differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 5823) = 18.36, p < .001. This path was significantly stronger for White women compared to both Black women, Δχ2(1, N = 5274) = 12.44, p < .001, and Hispanic women, Δχ2(1, N = 5002) = 5.23, p = .02, as well as for Asian women compared to both Black women, Δχ2(1, N = 821) = 8.08, p = .005, and Hispanic women, Δχ2(1, N = 549) = 4.23, p = .04.

The path from muscular-ideal internalization to body surveillance also differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 5823) = 19.13, p < .001. This path was significantly stronger for White women compared to Black women, Δχ2(1, N = 5274) = 9.17, p = .003, Hispanic women, Δχ2(1, N = 5002) = 5.60, p = .02, and Asian women, Δχ2(1, N = 5141) = 6.41, p = .01.

3.2.1.3. Racial Differences in Paths to Appearance Evaluation.

The path from family appearance pressures to appearance evaluation differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 5823) = 12.37, p = .006; compared to Black women, this path was significantly stronger for both White women, Δχ2(1, N = 5274) = 10.98, p < .001, and Asian women, Δχ2(1, N = 821) = 7.23, p = .007.

The path from media appearance pressures to appearance evaluation also differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 5823) = 11.33, p = .01; this path was significantly stronger for White women compared to Black women, Δχ2(1, N = 5274) = 10.77, p = .001, and for Black women compared to Asian women, Δχ2(1, N = 821) = 9.28, p = .002.

The path from thin-ideal internalization to appearance evaluation also differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 5823) = 29.20, p < .001; this path was significantly stronger for Black women compared to White women, Δχ2(1, N = 5274) = 37.39, p < .001, Hispanic women, Δχ2(1, N = 682) = 12.17, p < .001, and Asian women, Δχ2(1, N = 821) = 22.14, p < .001.

The path from muscular-ideal internalization to appearance evaluation also differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 5823) = 22.74, p < .001; compared to Black women, this path was significantly stronger for White women, Δχ2(1, N = 5274) = 24.31, p = < 0.001, Hispanic women, Δχ2(1, N = 682) = 4.83, p = .03, and Asian women, Δχ2(1, N = 821) = 12.31, p < .001.

Finally, the path from body surveillance to appearance evaluation differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 5823) = 14.71, p = .002; this path was significantly stronger for White women compared to Hispanic women, Δχ2(1, N = 5002) = 5.55, p = .02, as well as for Black women compared to both White women, Δχ2(1, N = 5274) = 10.15, p = .001, and Hispanic women, Δχ2(1, N = 682) = 12.83, p < .001.

3.2.2. Racial Differences and Similarities in Appearance Evaluation Model among Men

Among men, the fully variant structural model predicting appearance evaluation demonstrated adequate fit (CFI =0.965, RMSEA =0.074 with 90% CI =0.073–0.075, SRMR =0.068) and significantly better fit than the fully invariant model, Δχ2(39, N = 4877) = 111.71, p < .001, indicating that at least one path differed in strength between race groups. Fig. 2 presents standardized path estimates for each race group from the fully variant model predicting appearance evaluation among men. Six paths differed significantly by race; these paths are bolded in Fig. 2, and the racial differences observed for each of these paths are described below.

Fig. 2.

Multi-group structural equation model estimates for appearance evaluation by race among men. Appearance evaluation is labeled here as “appearance satisfaction” to denote that higher scores indicate more positive body image. Standardized path estimates are listed in the following order: White (red font), Black (blue font), Hispanic (green font), Asian (purple font). Paths that significantly differed between racial groups are bolded. Arrows for nonsignificant pathways are not shown. * p < .05, * * p < .01, * ** p < .001.

3.2.2.1. Racial Differences in Paths to Internalization of Appearance Ideals.

The path from family appearance pressures to lean-ideal internalization differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 4877) = 8.82, p = .04. This path was significantly stronger for White men compared to Asian men, Δχ2(1, N = 4315) = 5.22, p = .02, as well as for Black men compared to Hispanic men, Δχ2(1, N = 562) = 10.22, p = .001.

The path from peer appearance pressures to lean-ideal internalization also differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 4877) = 8.14, p = .04. This path was also significantly stronger for White men compared to Asian men, Δχ2(1, N = 4315) = 5.25, p = .02, as well as for Black men compared to Hispanic men, Δχ2(1, N = 562) = 10.23, p = .001.

The path from peer appearance pressures to muscular-ideal internalization also differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 4877) = 12.31, p = .006. This path was significantly stronger for Black men compared to White men, Δχ2(1, N = 4242) = 10.35, p = .001, and Hispanic men, Δχ2(1, N = 562) = 9.43, p = .002.

3.2.2.2. Racial Differences in Paths to Body Surveillance.

The path from media appearance pressures to body surveillance differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 4877) = 14.15, p = .003. This path in Hispanic men was significantly stronger compared to path in White men, Δχ2(1, N = 4210) = 9.20, p = .002, and in the opposite direction of the path observed for Black men, Δχ2(1, N = 562) = 10.84, p = .001. Additionally, this path was significantly stronger for Black men compared to Asian men, Δχ2(1, N = 667) = 4.51, p = .03.

The path from lean-ideal internalization to body surveillance also differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 4877) = 13.65, p = .003. This path was significantly stronger for Hispanic men compared to both White men, Δχ2(1, N = 4210) = 6.94, p = .008, and Black men, Δχ2(1, N = 562) = 7.53, p = .006; this path was also significantly stronger for White men compared to Asian men, Δχ2(1, N = 4315) = 6.25, p = .01.

3.2.2.3. Racial Differences in Paths to Appearance Evaluation.

The path from media appearance pressures to appearance evaluation also differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 4877) = 9.28, p = .03; this path was significantly stronger for Black men compared to White men, Δχ2(1, N = 4242) = 8.16, p = .004, Hispanic men, Δχ2(1, N = 562) = 7.90, p = .005, and Asian men, Δχ2(1, N = 667) = 8.99, p = .003.

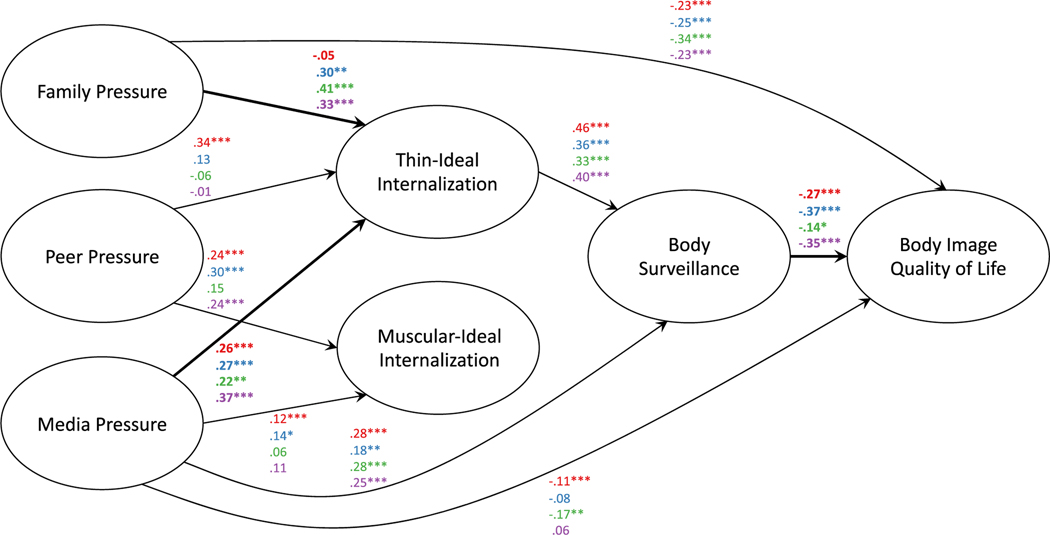

3.2.3. Racial Differences and Similarities in Body Image Quality of Life Model among Women

Among women, the fully variant structural model predicting body image quality of life demonstrated adequate fit (CFI =0.958, RMSEA =0.074 with 90% CI =0.074–0.075, SRMR =0.063) and significantly better fit than the fully invariant model, Δχ2(30, N = 5823) = 93.66, p < .001, indicating that at least one path differed in strength between racial groups. Fig. 3 presents standardized path estimates for each racial group from the fully variant model predicting body image quality of life among women. Three paths were found to differ by race; these paths are bolded in Fig. 3, and the racial differences observed for each of these paths are described below.

Fig. 3.

Multi-group structural equation model estimates for body image quality of life by race among women. Standardized path estimates are listed in the following order: White (red font), Black (blue font), Hispanic (green font), Asian (purple font). Paths that significantly differed between racial groups are bolded. Arrows for nonsignificant pathways are not shown. * p < .05, * * p < .01, * ** p < .001.

3.2.3.1. Racial Differences in Paths to Internalization of Appearance Ideals.

The path from family appearance pressures to thin-ideal internalization differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 5823) = 17.59, p < .001. Compared to White women, this path was significantly stronger for Black women, Δχ2(1, N = 5274) = 7.40, p = .007, and Asian women, Δχ2(1, N = 5141) = 15.41, p < .001; this path was also significantly stronger for Hispanic women compared to Asian women, Δχ2(1, N = 549) = 5.27, p = .02.

The path from media appearance pressures to thin-ideal internalization also differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 5823) = 16.76, p < .001; this path was significantly stronger for Asian women compared to White women, Δχ2(1, N = 5141) = 20.93, p < .001, Black women, Δχ2(1, N = 821) = 6.03, p = .01, and Hispanic women, Δχ2(1, N = 549) = 6.72, p = .01.

3.2.3.2. Racial Differences in Paths to Body Image Quality of Life.

The path from body surveillance to body image quality of life differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 5823) = 10.72, p = .01; this path was significantly stronger for Black women compared to both White women, Δχ2(1, N = 5274) = 11.66, p < .001, and Hispanic women, Δχ2(1, N = 682) = 10.11, p = .002.

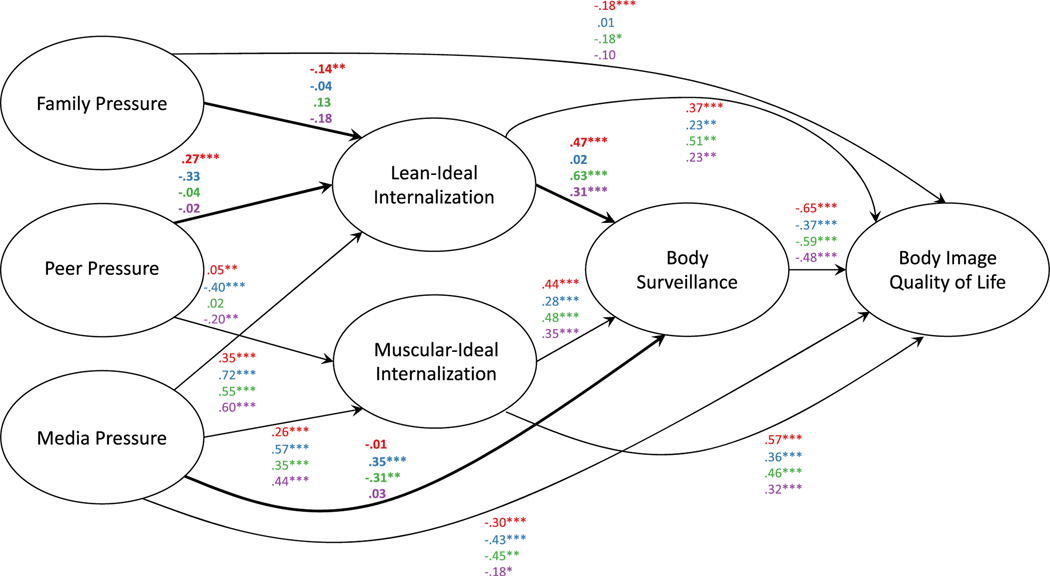

3.2.4. Racial Differences and Similarities in Body Image Quality of Life Model among Men

Among men, the fully variant structural model predicting body image quality of life demonstrated adequate fit (CFI =0.946, RMSEA =0.075 with 90% CI =0.074–0.075, SRMR =0.065) and significantly better fit than the fully invariant model, Δχ2(39, N = 4877) = 84.47, p < .001, indicating that at least one path differed in strength between racial groups. Fig. 4 presents standardized path estimates for each group from the fully variant model predicting body image quality of life among men. Four paths differed significantly by race; these paths are bolded in Fig. 4, and the racial differences observed for each of these paths are described below.

Fig. 4.

Multi-group structural equation model estimates for body image quality of life by race among men. Standardized path estimates are listed in the following order: White (red font), Black (blue font), Hispanic (green font), Asian (purple font). Paths that significantly differed between racial groups are bolded. Arrows for nonsignificant pathways are not shown. * p < .05, * * p < .01, * ** p < .001.

3.2.4.1. Racial Differences in Paths to Internalization of Appearance Ideals.

The path from family appearance pressures to lean-ideal internalization differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 4877) = 11.20, p = .01. Compared to Black men, this path was significantly stronger for White men, Δχ2(1, N = 4242) = 8.37, p = .004, and Hispanic men, Δχ2(1, N = 562) = 4.53, p = .03. Additionally, this path was significantly stronger for Asian men compared to White men, Δχ2(1, N = 4315) = 4.90, p = .03, and Black men, Δχ2(1, N = 667) = 8.38, p = .004.

The path from peer appearance pressures to lean-ideal internalization differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 4877) = 8.40, p = .04. This path differed significantly for Black men compared to White men, Δχ2(1, N = 4242) = 6.36, p = .01, Hispanic men, Δχ2(1, N = 562) = 5.58, p = .02, and Asian men, Δχ2(1, N = 667) = 9.14, p = .003.

3.2.4.2. Racial Differences in Paths to Body Surveillance.

The path from media appearance pressures to body surveillance differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 4877) = 12.24, p = .007. This path differed significantly for Black men compared to Hispanic men, Δχ2(1, N = 562) = 10.23, p = .001, and Asian men, Δχ2(1, N = 667) = 10.82, p = .001. Additionally, this path differed significantly for White men compared to Hispanic men, Δχ2(1, N = 4210) = 4.57, p = .03, and Asian men, Δχ2(1, N = 4315) = 4.28, p = .04.

The path from lean-ideal internalization to body surveillance also differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 4877) = 9.29, p = .03; this path was significantly stronger for White men compared to Asian men, Δχ2(1, N = 4315) = 6.06, p = .01.

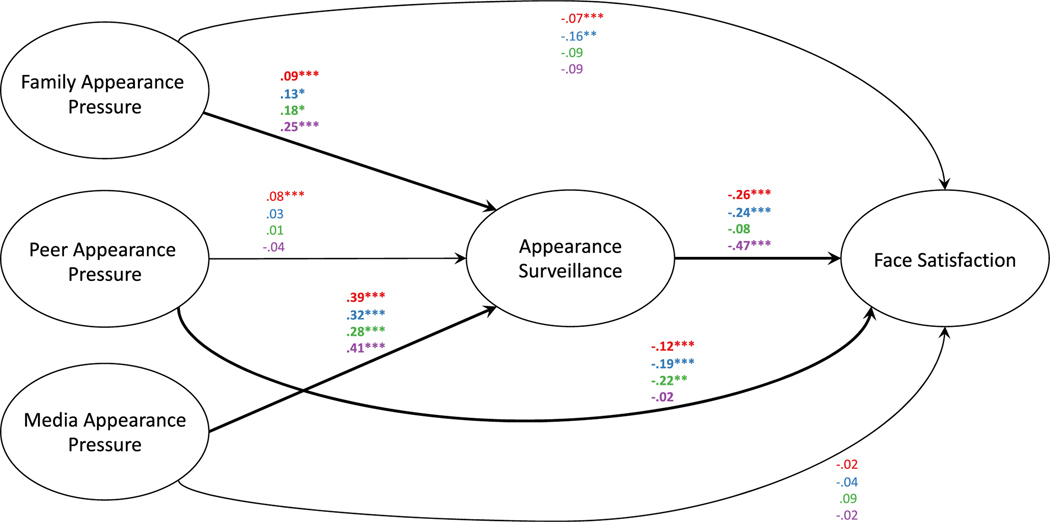

3.2.5. Racial Differences and Similarities in Face Satisfaction Model among Women

Single-group analysis yielded adequate fit of the structural model predicting face satisfaction among women (CFI =0.981, RMSEA =0.062 with 90% CI =0.058–0.065, SRMR =0.039). In multi-group analyses, the fully variant model predicting face satisfaction demonstrated adequate fit (CFI =0.983, RMSEA =0.045 with 90% CI =0.042–0.048, SRMR =0.042) and significantly better fit than the fully invariant model, Δχ2(21, N = 5823) = 57.11, p < .001, indicating that at least one path differed in strength between racial groups. Fig. 5 presents standardized path estimates for each racial group from the fully variant model predicting face satisfaction among women. Four paths differed significantly by race; these paths are bolded in Fig. 5, and the racial differences observed for each of these paths are described below.

Fig. 5.

Multi-group structural equation model estimates for face satisfaction by race among women. Standardized path estimates are listed in the following order: White (red font), Black (blue font), Hispanic (green font), Asian (purple font). Paths that significantly differed between racial groups are bolded. Arrows for nonsignificant pathways are not shown. * p < .05, * * p < .01, * ** p < .001.

3.2.5.1. Racial Differences in Paths to Appearance Surveillance.

The path from family appearance pressures to appearance surveillance differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 5823) = 9.45, p = .02; this path was significantly stronger for Asian women compared to White women, Δχ2(1, N = 5141) = 6.99, p = .008.

The path from media appearance pressures to appearance surveillance also differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 5823) = 10.52, p = .01; this path was significantly stronger for White women compared to Hispanic women, Δχ2(1, N = 5002) = 5.63, p = .02, as well as for Asian women compared to both Black women, Δχ2(1, N = 821) = 4.216, p = .04, and Hispanic women, Δχ2(1, N = 549) = 7.65, p = .006.

3.2.5.2. Racial Differences in Paths to Face Satisfaction.

The path from peer appearance pressures to face satisfaction differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 5823) = 10.08, p = .02; compared to Asian women, this path was significantly stronger for White women, Δχ2(1, N = 5141) = 4.93, p = .03, Black women, Δχ2(1, N = 821) = 8.10, p = .004, and Hispanic women, Δχ2(1, N = 549) = 5.67, p = .02.

The path from appearance surveillance to face satisfaction also differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 5823) = 19.78, p = .0002; this path was significantly stronger for Asian women compared to White women, Δχ2(1, N = 5141) = 16.72, p < .0001, Black women, Δχ2(1, N = 821) = 6.83, p = .009, and Hispanic women, Δχ2(1, N = 549) = 16.63, p < .0001, as well as significantly weaker for Hispanic women compared to White women, Δχ2(1, N = 5002) = 4.61, p = .03, and Black women, Δχ2(1, N = 682) = 4.30, p = .04.

3.2.6. Racial Differences and Similarities in Face Satisfaction Model among Men

Single-group analysis yielded adequate fit of the structural model predicting face satisfaction among men (CFI =0.988, RMSEA =0.055 with 90% CI =0.051–0.059, SRMR =0.034). In multi-group analyses, the fully variant model predicting face satisfaction demonstrated adequate fit (CFI =0.988, RMSEA =0.044 with 90% CI =0.041–0.047, SRMR =0.037) and significantly better fit than the fully invariant model, Δχ2(21, N = 4877) = 41.47, p = .005, indicating that at least one path differed in strength between racial groups. Fig. 6 presents standardized path estimates for each racial group from the fully variant model predicting face satisfaction among men. Three paths differed significantly by race; these paths are bolded in Fig. 6, and the racial differences observed for each of these paths are described below.

Fig. 6.

Multi-group structural equation model estimates for face satisfaction by race among men. Standardized path estimates are listed in the following order: White (red font), Black (blue font), Hispanic (green font), Asian (purple font). Paths that significantly differed between racial groups are bolded. Arrows for nonsignificant pathways are not shown. * p < .05, * * p < .01, * ** p < .001.

3.2.6.1. Racial Differences in Paths to Appearance Surveillance.

The path from peer appearance pressures to appearance surveillance differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 4877) = 11.71, p = .009; this path was significantly stronger for White men compared to Asian men, Δχ2(1, N = 4315) = 8.80, p = .003.

3.2.6.2. Racial Differences in Paths to Face Satisfaction.

The path from peer appearance pressure to face satisfaction differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 4877) = 8.70, p = .03; this path was also significantly stronger for White men compared to Asian men, Δχ2(1, N = 4315) = 8.52, p = .004.

The path from media appearance pressure to face satisfaction also differed by race, Δχ2(3, N = 4877) = 15.13, p = .002; this path was significantly stronger for Black men compared to both White men, Δχ2(1, N = 4242) = 11.74, p < .001, and Hispanic men, Δχ2(1, N = 562) = 9.10, p = .003.

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview of Findings

Despite evidence that individuals from diverse backgrounds report significant body image concerns (Frederick et al., 2020; Grabe & Hyde, 2006; Roberts et al., 2006; Wildes et al., 2001), most theoretical models of body image have been primarily developed and tested within largely White female samples, raising questions about the applicability of those models to more diverse groups (Johnson et al., 2015; Keery et al., 2004; Rodgers et al., 2011; van den Berg et al., 2002). Therefore, the aim of the current study was to examine an integrated sociocultural model of body image, combining elements of the tripartite influence model and objectification theory, across large samples of White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian participants using multi-group SEM.

Building upon prior research indicating that appearance experiences (e.g., thin-ideal internalization, appearance surveillance, and body satisfaction) vary across racial groups (Claudat et al., 2012; Frederick et al., 2020; Frederick, Kelly, et al., 2016), findings from the current study indicate that the strength of the of the pathways from the tripartite and objectification constructs to body image outcomes also vary by race. These findings thereby provide both important support for extending these models across racial groups as well as evidence of differences across groups.

4.1.1. Findings for Women

Notably, women demonstrated more numerous group differences in pathway strength than men in the current study. In models predicting appearance evaluation and body image quality of life, media appearance pressures emerged as the most robust predictor of thin-ideal internalization across all examined racial groups. That is, greater perceived media pressure was significantly associated with greater thin-ideal internalization for White, Black, Hispanic, and Asian women. However, this relationship was strongest for Asian women. These findings converge with prior research identifying media as a key contributor to appearance ideal internalization and other deleterious appearance-related experiences among women (Frederick, Daniels et al., 2017), and suggest that Asian women may be most vulnerable to internalizing thinness-oriented media messages.

The relationship between family appearance pressures and thin-ideal internalization was also most pronounced among Asian women, as well as Hispanic women. In considering these results, it is possible that Asian women may be more sensitive to media and family pressures, potentially due to greater interdependent self-construal stemming from a collectivist cultural background (Frederick, Kelly, et al., 2016; Markus & Kitayama, 1991), as well as a greater tendency to experience thinness pressures from parents (Smart, Tsong, Mejía, Hayashino, & Braaten, 2011). The finding that Hispanic women were the most likely to internalize appearance pressures from family may be viewed in light of previous research indicating that familism (i.e., the central role of the family) represents a core value in Hispanic culture (Sabogal, Marín, Otero-Sabogal, Marín, & Perez-Stable, 1987). As previous studies indicate that Hispanic cultural appearance ideals promote both thin and curvy bodies (Franko et al., 2012), it is possible that family pressures may give rise to an especially strong focus on weight and shape in this group.

Consistent with previous studies identifying the thin ideal as the predominant appearance ideal for girls and women (Thompson et al., 1999), higher levels of thin ideal-internalization were related to greater body surveillance across all groups (with stronger effects observed for White and Asian women), while muscular-ideal internalization was only associated with surveillance for White women. These findings contrast with a previous study indicating that the associations between internalization and body surveillance were similar for White and Hispanic women (Boie et al., 2013). However, the authors of that study noted that small sample size may have diminished their ability to identify significant differences between groups. Thus, internalization of the thin ideal as one’s own standard of beauty appears to increase risk for habitual body monitoring among diverse groups of women, but this may be especially true for White and Asian women.

Finally, the relationships between body surveillance and the theoretical outcomes of appearance evaluation and body image quality of life appeared to be reliable among Black women, and somewhat stronger than the associations found for White women. These results suggest that the experience of continuously monitoring one’s appearance and considering how others evaluate one’s appearance may have a deep impact on Black women’s body image. Interestingly, these results contrast with previous research indicating that the relationship between body surveillance and body shame was weakest among Black women compared to White and Hispanic women (Schaefer et al., 2018). Given historical racism against Black individuals in the U.S., it is possible that this result reflects a recognition among Black women that their appearance (potentially including their skin color) impacts how others perceive them. Although Black women are more likely to report high body satisfaction than White women, when considering the variation in body surveillance among Black women, those Black women who are high in body surveillance may be especially likely to experience negative effects as a result of this body high surveillance. It is possible that these relationships among Black women reflect pre-occupations that extend beyond weight and shape concerns in the context of the pursuit of appearance ideals and encompass fear of discrimination. These findings suggest the need for continued research exploring the complex relationship between Black women’s appearance monitoring and risk for negative body image outcomes.

In models predicting face satisfaction among women, media influences were again most robustly associated with the proposed downstream outcome of appearance surveillance, although this effect was strongest for White and Asian women. While family pressures were significantly (although more modestly) associated with appearance surveillance for all groups, this effect was especially strong for Asian women. In contrast, peer appearance pressures exhibited only negligible or non-significant associations with appearance surveillance for all groups. Notably, however, peer appearance pressures had a direct relationship with face satisfaction for White Black, and Hispanic women. These findings indicate that media and family appearance pressures may contribute to engagement in appearance self-monitoring, particularly among Asian and White women, while peer pressures may contribute to face satisfaction via other means (e.g., shame) for White, Black, and Hispanic women. Finally, the link between appearance surveillance and face satisfaction was especially pronounced among Asian women and non-significant for Hispanic women. Overall, these findings are consistent with previous research indicating that Asian women evidence heightened dissatisfaction with their facial features (Frederick, Kelly, et al., 2016), and indicate that pressures from media and family may especially contribute to these concerns.

4.1.2. Findings for Men

Media pressures were strongly linked to lean-ideal and muscular-ideal internalization for men. This suggests that even if the mean scores for the media appearance pressures are not particularly high, among the men who do strongly feel these pressures, they are highly associated with internalization of these appearance ideals. The associations were particularly strong for Black men, which might relate to the fact that media representations of Black men include a strong emphasis on toughness, physicality, athleticism, and sports, which can then shape expectations for what constitutes masculinity (Goodwill et al. 2019). This same logic may also explain why peer pressures were particularly strongly linked to lean-ideal and muscular-ideal internalization for Black men if these media influences shape, or reinforce, expectations about masculinity and appearance among peer groups.

Consistent with research indicating that muscularity is a central appearance focus for men (Frederick, Buchanan, et al., 2005; Frederick & Essayli, 2016; McCreary & Sasse, 2000), muscular-ideal internalization was a robust predictor of body surveillance across all male racial groups, as was lean-ideal internalization for all groups except for Black men. Body surveillance was then associated with appearance satisfaction and body image quality of life for all groups. These findings reinforce the suitability of the model for most groups of men. The non-significant association between lean-ideal internalization and body surveillance for Black men, however, is worth further attention. One possibility is that the strong links between media pressure, muscular-ideal internalization, surveillance and body image outcomes are dominating these relationships, and being muscular and athletic is more central to Black men’s masculinity than being lean. Further work, however, is needed to understand this association.

In the model examining face satisfaction, media influences demonstrated the strongest and most robust associations with appearance surveillance across groups, and were directly related to face satisfaction for Black men, indicating that general media appearance pressures (i.e., those not promoting a specific appearance ideal) may be strongly related to general appearance monitoring behaviors for most men, but have an especially detrimental impact on Black men’s face satisfaction. These results coalesce with prior research indicating that face satisfaction may be an especially important dimension of body image among Black individuals (Capodilupo, 2015; Frederick, Kelly, et al., 2016). Further, some research indicates that media images commonly value lighter-skinned Black faces with Eurocentric features over darker-skinned Black faces with Afrocentric features. For example, media content analyses suggest that when Black characters are portrayed in television, favorable attributes (e.g., beauty, intelligence) are given to those with Eurocentric facial characteristics, while unfavorable attributes (e.g., unattractiveness, deviance) are given to those with Afrocentric facial features (Steele, 2016). Thus, media portrayals of Black individuals which denigrate Afrocentric features may play an especially powerful role in shaping Black men’s face satisfaction.

In contrast, general family appearance pressures showed only weak or non-significant associations with surveillance among all racial groups, and peer appearance pressures were only related to downstream outcomes (surveillance and face satisfaction) for White men. Importantly, regardless of the degree or source of sociocultural pressure, when men from any of the four groups engaged in higher appearance surveillance, they were equally likely to experience reduced face satisfaction.

4.2. Limitations and Strengths

A few limitations should be noted. Our study relied on a large national sample, but this sample was not nationally representative and was limited to Mechanical Turk workers (for a more detailed discussion of how this sample compares to nationally representative samples, see Frederick, Crerand, et al., 2022). Furthermore, to maximize sample size and power, we used broad racial categories that group together diverse cultural and phenotypic categories. These decisions are further complicated by the fact that lay definitions of ethnic and racial categories are in constant flux, and researcher definitions of these categories do not always map on to lay understandings of these categories, and many participants do not differentiate between them (Terry & Fond, 2013). It is not known how associations among these variables might differ among Mechanical Turk workers, or if the representativeness of these workers to the general population is equal across racial groups. Additionally, although our large sample size enabled us to examine pathways among White, Asian, Hispanic, and Black men and women, we had relatively smaller samples of biracial, multiracial, or ethnic and racial minority participants. Examining the pathways and unique pressures faced by these groups is important for future investigation. Furthermore, we relied on self-reported height and weight to calculate BMI, is be subject to reporting bias, and BMI is problematic as a proposed indicator of health status (e.g., Tomiyama, Hunger, Nguyen-Cuu, & Wells, 2016), and is associated with experiencing weight stigma (Puhl & Brownell, 2006). Furthermore, neither temporality nor causality can be determined from the cross-sectional design. Prospective studies examining these models across racial groups will be valuable.

Despite limitations, this study contains noteworthy strengths. First, the analytic sample was large and diverse in regard to race, gender, and age, addressing the need for more research in this field beyond the commonly restricted demographic of young, White women. It provided the rare opportunity to test and compare these pathways across racial minority men and women. Additionally, this study examined positive dimensions of body image (i.e., body image quality of life and appearance evaluation), broadening our understanding of body image experiences beyond pathological body image. Furthermore, we examined face satisfaction as a separate outcome. Prior research has demonstrated this to be a distinct factor from other facets of body satisfaction (Frederick, Bohrnstedt, Hatfield, & Berscheid, 2014) that is central to certain racial groups’ appearance evaluation (Frederick, Kelly, et al., 2016; Hall, 1995; Kennedy, Templeton, Gandhi, & Gorzalka, 2004; Mintz & Kashubeck, 1999; Pham, 2014; Warren, 2012). Results from this model displayed differences in pathway strength by race, underscoring the value of including face satisfaction as an outcome when studying diverse groups.

4.3. Concluding Comments

Findings from this study support the utility of an integrated sociocultural model of body image across a range of racial groups. Further, many associations between hypothesized risk factors and body image outcomes were similar in strength across racial groups, suggesting that those factors may operate as universally meaningful targets for body image interventions. Results also suggest that some proposed risk factors may be especially relevant to body image outcomes within specific racial groups. For example, Asian women may be especially vulnerable to the harmful effects of media and family appearance pressures, and appearance ideal internalization. Surveillance appeared to be as strongly linked to body image outcomes for Black women as for White women, highlighting the potential importance of surveillance in raising body dissatisfaction among Black women. Among men, media pressures may be especially tied to Black men’s face satisfaction. As interventions emerging from sociocultural models have demonstrated considerable success in primarily White female samples (e.g., dissonance-based and media literature approaches; Stice, Marti, Spoor, Presnell, & Shaw, 2008; Wilksch & Wade, 2009), findings from the current study suggest that these interventions might be effectively adapted and applied to address the shared and specific appearance-related experiences among Black, Hispanic, and Asian men and women.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (grant number T32 MH082761), the National Institute of General Medical Science (1P20GM134969-01A1), and the Kay Family Foundation Data Analytic Grant: 201920202021.

Footnotes

CRediT authorship contribution statement

The first author completed the conceptualization and methodology. The next three authors took the lead on writing and data analyses. All authors engaged in the writing, and made suggestions for interpreting and enhancing the formal analysis. Along with the first author, the last authors engaged in supervision. The first author was primarily involved with funding acquisition (grant PI).

References

- Allen Q.(2021). Campus racial climate, boundary work and the fear and sexualization of black masculinities on a predominantly White university. Men and Masculinities http://doi.org/1097184x211039002. [Google Scholar]

- Beltran M.(2002). The Hollywood Latina body as site of social struggle: Media constructions of stardom and Jennifer Lopez’s“ cross-over butt”. Quarterly Review of Film and Video, 19, 71–86. 10.1080/10509200214823 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini Y, & Hochberg Y.(1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B ((Methodological)), 57(1), 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psychological Bulletin, 107, 238–246. 10.1037/0033-2909.107.2.238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke NL, Schaefer LM, Karvay YG, Bardone-Cone AM, Frederick DA, Schaumberg K, Klump KL, Anderson DA, & Thompson JK (2021). Does the tripartite influence model of body image and eating pathology function similarly across racial/ethnic groups of White, Black, Latina, and Asian women? Eating Behaviors. 42, 101519. 10.1016/j.eatbeh.2021.101519 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berinsky AJ, Huber GA, & Lenz GS (2012). Evaluating online labor markets for experimental research: Amazon.com’s Mechanical Turk. Political Analysis, 20, 351–368. 10.1093/pan/mpr057 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boie I, Lopez AL, & Sass DA (2013). An evaluation of a theoretical model predicting dieting behaviors: Tests of measurement and structural invariance across ethnicity and gender. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development,46, 114–135. 10.1177/0748175612468595 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen L, & Schmid J.(1997). Minority presence and portrayal in mainstream magazine advertising: An update. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 74, 134–146. [Google Scholar]

- Breitkopf CR, Littleton H, & Berenson A.(2007). Body image: A study in a tri-ethnic sample of low income women. Sex Roles, 56, 373–380. 10.1007/s11199-006-9177-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown TA, Cash TF, & Mikulka PJ (1990). Attitudinal body image assessment: Factor analysis of the Body-Self Relations Questionnaire. Journal of Personality Assessment, 55, 135–144. 10.1080/00223891.1990.9674053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, & Cudeck R.(1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Bollen KA, & Long JS(Eds.). Testing Structural Equation Models Newbury Park, CA: Sage. 10.1177/0049124192021002005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan TS, Fischer AR, Tokar DM, & Yoder JD (2008). Testing a culture- specific extension of objectification theory regarding African American women’s body image. The Counseling Psychologist, 36, 697–718. 10.1177/0011000008316322 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester M, Kwang T, & Gosling SD (2011). Amazon’s Mechanical Turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 6, 3–5. 10.1177/1745691610393980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burch RL, & Johnsen L.(2020). Captain Dorito and the bombshell: Supernormal stimuli in comics and film. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences. 10.1037/ebs0000164 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Capodilupo CM (2015). One size does not fit all: Using variables other than the thin ideal to understand Black women’s body image. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 21, 268–278. 10.1037/a0037649 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cash TF (2000). The Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire User’s Manual. (Available from the author at) www.body-images.com. [Google Scholar]

- Cash TF, & Fleming EC (2002). The impact of body-image experiences: Development of the Body Image Quality of Life Inventory. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 31, 455–460. 10.1002/eat.10033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cashel ML, Cunningham D, Landeros C, Cokley KO, & Muhammad G.(2003). Sociocultural attitudes and symptoms of bulimia: Evaluating the SATAQ with diverse college groups. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50, 287–296. 10.1037/0022-0167.50.3.287 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheeseborough T, Overstreet N, & Ward LM (2020). Interpersonal sexual objectification, Jezebel stereotype endorsement, and justification of intimate partner violence toward women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 44(2), 203–216. 10.1177/0361684319896345 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheney AM (2011). “Most girls want to be skinny” Body (dis)satisfaction among ethnically diverse women. Qualitative Health Research, 21, 1347–1359. 10.1177/1049732310392592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]