Abstract

Background and Aims:

Most population studies that evaluate the relationship between nicotine vaping and cigarette cessation focus on limited segments of the smoker population. We evaluated vaping uptake and smoking cessation considering differences in smokers’ plans to quit.

Design:

Longitudinal ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Surveys conducted in 2016, 2018, and 2020.

Setting:

US, Canada, England, Australia.

Participants:

Adult daily cigarette smokers who had not vaped in the past 6 months at baseline and had participated in two or more consecutive waves of the ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Surveys (n= 2,815).

Measurements:

Plans to quit cigarette smoking at baseline (within 6 months, beyond 6 months, not planning to quit) and at follow-up (within 6 months versus not within 6 months); cigarette smoking cessation at follow-up (smoking less than monthly [including complete cessation] versus daily/weekly/monthly smoking); inter-wave vaping uptake (none, only nondaily vaping, any daily vaping). Generalized estimating equations were used to evaluate whether inter-wave vaping uptake was associated with smoking cessation at follow-up, and with planning to quit at follow-up, each stratified by plans to quit smoking at baseline.

Findings:

Overall, 12.7% of smokers quit smoking. Smokers not initially planning to quit within 6 months experienced higher odds of smoking cessation when they took up daily vaping (32.4%) versus no vaping (6.8%; adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=8.58, 95% confidence interval [CI]:5.06–14.54). Among smokers planning to quit, smoking cessation rates were similar between those who did and did not take up daily vaping (25.1% vs. 16.8%; AOR=1.91, 95%CI:0.91–4.00), though we could not account for potential use of cessation aids. Daily vaping uptake was associated with planning to quit smoking at follow-up among those initially not planning to quit (AOR=6.32, 95%CI:4.17–9.59).

Conclusions:

Uptake of nicotine vaping appears to be strongly associated with cigarette smoking cessation among smokers with no initial plans to quit smoking. Excluding smokers not planning to quit from studies on vaping and smoking cessation may underestimate potential benefit of daily vaping for daily smokers.

Keywords: Cigarette smoking cessation, nicotine vaping products, e-cigarettes, tobacco, quitting plans, population, longitudinal, public health, socioeconomic status, disparities

INTRODUCTION

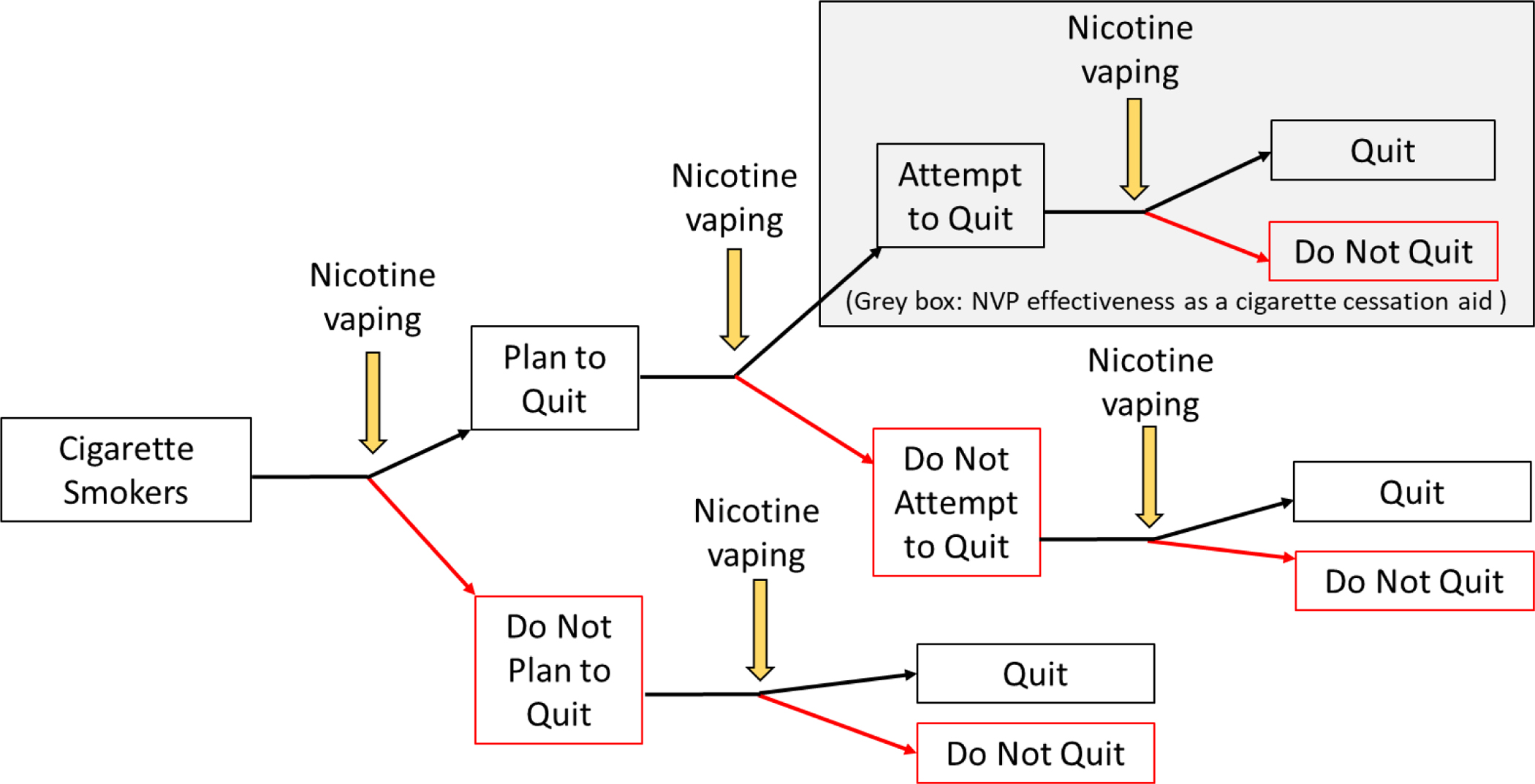

Most population-based studies that have evaluated the relationship between use of Nicotine Vaping Products (NVPs) and cigarette smoking cessation have focused on cigarette smokers who attempt to quit or who express interest in quitting smoking.1 However, nicotine vaping may be related to longer-term progression toward smoking cessation at the population level (see Figure 1). Studies that are limited to smokers who are already planning to quit, or who attempt to quit, exclude from consideration any positive or negative impact that nicotine vaping may have on earlier junctures of the smoking cessation process.

Figure 1.

Junctures at which nicotine vaping may relate to progression toward cigarette smoking cessation at the population level.

NVP: Nicotine Vaping Product

Indeed, using data from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study, a longitudinal study in the United States (US), Kasza et al. (2021a) found that adult daily cigarette smokers who were not planning to ever quit smoking experienced nearly six-fold higher odds of planning to quit smoking in the future when they initiated daily vaping.2 Further, using PATH Study data, Kasza et al. (2021b) found that daily vaping uptake was associated with eight-fold greater odds of smoking cessation among those who were not planning to ever quit.3 These findings are consistent with experimental studies that have reported that giving NVPs to unmotivated smokers is positively associated with change in quit intentions4–5 and reductions in cigarette smoking.6–7 However, no study has yet investigated whether the association between uptake of NVP use and cigarette smoking cessation differs as a function of smokers’ initial plans to quit.

We hypothesized that the association between uptake of daily vaping and smoking cessation may be stronger among those who were initially not planning to quit than among those who were initially planning to quit, as there are more junctures in the cessation process that vaping can act upon among the former group than among the latter group (Figure 1). That is, vaping may be positively associated with planning to quit, with making a quit attempt, and/or with quitting among those who made a quit attempt. However, aside from the first juncture, where a person’s quitting plans can be reported in the present, population studies that evaluate quit attempts or vaping effectiveness as a cigarette cessation aid (grey box in Figure 1) necessarily exclude from consideration all those who did not characterize themselves as having attempted to quit.8–10 If recall of quit attempts systematically differs between those who did and did not use NVPs or other cessation aids, then efforts are needed to mitigate potential bias in analyses of making a quit attempt and analyses of cessation aid effectiveness when using population-based data.11–13 Our approach was to determine whether current report of quit plans at baseline, which was not subject to recall, distinguishes a differential relationship between vaping uptake and smoking cessation at the population level, extending findings recently reported from the US-only PATH Study.2,3

We used longitudinal data from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Smoking and Vaping Surveys (ITC 4CV) to evaluate the relationship between uptake of NVP use and smoking cessation among adult daily cigarette smokers in the US, Canada, England, and Australia, stratified by initial plans to quit smoking. We also evaluated the relationship between uptake of NVP use and change in plans to quit smoking, again stratified by initial plans to quit smoking.

METHODS

Population

Cohort data for this study come from the 2016–2020 ITC 4CV surveys (Waves 1–3). The ITC 4CV includes four parallel online surveys of adult (ages 18+ years) cigarette smokers and recent quitters in the US, Canada, England, and Australia. Wave 1 data were collected from July 2016–November 2016; Wave 2 from February 2018–July 2018; and Wave 3 from February 2020–June 2020. The retention rate for Wave 2 was 45%14 and the retention rate for Wave 3 was 42%.15 Detailed information on sample recruitment, retention, weighting, etc. can be found in the ITC 4CV technical reports14–15 and methods paper,16 and the full surveys and information on accessing the data are available at: https://itcproject.org.

We analyzed data from daily cigarette smokers who had never vaped or had not vaped in the past six months at their baseline assessment, participated in the next follow-up assessment, and had an inter-wave interval between baseline and follow-up of 18–24 months. These criteria of having not vaped in the past six months at baseline and having an inter-wave interval of 18–24 months were required to ascertain inter-wave vaping uptake that followed the baseline assessment of cigarette quit plans (further described in the Measures section), which excluded 539 persons (please see Supplemental Figure 1), leaving a final sample of n=2,815 persons who contributed n=3,405 observations (i.e., 2,815 persons provided one wave-pair observation and 590 persons provided two wave-pair observations). Compared to the 2,815 persons included in analyses, the 539 persons excluded from analyses were more likely to be younger, male, heavier smokers, and from Canada. Those included versus excluded did not differ on their plans to quit smoking, cessation rates, socioeconomic indicators or race/ethnicity (Supplemental Figure 1).

Measures

Measures are described as being assessed at ‘baseline’ and/or at ‘follow-up.’ That is, we used three waves of data with Wave 1 serving as baseline wave to Wave 2, and with Wave 2 serving as baseline wave to Wave 3, such that the three waves were evaluated as two wave pairs. That is, a person could provide one wave-pair observation, or could provide two wave-pair observations if the person was present in all three waves and met the baseline eligibility criteria at both Wave 1 and Wave 2. In the Statistical Analysis section, we describe our analytic approach to account for multiple observations contributed by a person.

Cigarette quit plans at baseline

At each assessment, smokers were asked: “Are you planning to quit smoking…” with response options being within the next month; between 1–6 months from now; sometime in the future, beyond 6 months; not planning to quit; don’t know. We combined response options and we present results for those who were planning to quit within the next 6 months and for those who were not planning to quit within the next 6 months.

Descriptive characteristics at baseline

Respondents reported their sex (male, female), race/ethnicity (ethnic majority: White/English vs. ethnic minority: Black/other minority), age (18–24 years, 25–39 years, 40–54 years, 55+ years), income (low, moderate, high, not reported, which incorporated country-specific differences in currency) and educational attainment (low, moderate, high, not reported, which incorporated country-specific differences in education systems), which were combined to indicate socioeconomic status (SES) as follows: low if both income and education were low, moderate if either income or education was low, and high if neither income nor education were low (respondents who answered only one of the two items were included in the SES category called for by the answered item), country (US, Canada, England, Australia), cigarettes smoked per day (CPD, 1–10, 11–20, 21–30, 31+), quitting self-efficacy using the item “If you decided to give up smoking completely in the next 6 months, how sure are you that you would succeed? You do not need to be intending to quit to respond” (not at all sure/slightly sure, moderately sure, very sure/extremely sure, don’t know), and desire to quit smoking using the item “How much do you want to quit smoking?” (not at all, a little, somewhat, a lot, don’t know).

Uptake of vaping between baseline and follow-up (inter-wave vaping uptake)

At each assessment, respondents were asked whether they ever vaped and if so, how often they currently vape (daily; less than daily but at least once a week; less than weekly but at least once a month; less than once a month but occasionally; not at all), whether they ever vaped daily and if so, how long ago they stopped vaping daily (less than 1 month ago; 1–3 months ago; 4–6 months ago; 7–12 months ago; 1–2 years ago; more than 2 years ago), and how long ago they last vaped (less than 1 week ago; 1–4 weeks ago; 1–3 months ago; 4–6 months ago; 7–12 months ago; 1–2 years ago; more than 2 years ago).

Among those who at baseline had not vaped within the past six months (which includes those who never vaped and those who last vaped more than six months before baseline), we derived a measure of inter-wave vaping uptake between baseline and follow-up as follows: (1) no vaping uptake (i.e., no vaping after baseline including at follow-up assessment), (2) uptake of only nondaily vaping (i.e., any nondaily vaping after baseline including nondaily vaping at follow-up assessment; note that ‘uptake of only nondaily vaping’ includes those who vaped only once after baseline to make the qualitative distinction between no vaping and any vaping), (3) uptake of any daily vaping (i.e., any daily vaping after baseline including daily vaping at follow-up assessment). We also conducted a separate set of analyses in which we combined the ‘uptake of only nondaily vaping’ group with the ‘uptake of any daily vaping’ group to produce an ‘uptake of any vaping’ group, and we compared this combined group to the ‘no vaping uptake’ group.

Cigarette smoking cessation at follow-up (outcome)

We defined cigarette smoking cessation at follow-up as smoking cigarettes less than monthly, including complete cessation, versus daily/weekly/monthly smoking at follow-up. We also conducted a set of sensitively analyses in which we coded less than monthly cigarette smokers as not having achieved cigarette smoking cessation.

Planning to quit cigarette smoking at follow-up (outcome)

The same item described above for cigarette quit plans at baseline was also used to assess whether plans to quit had changed at follow-up. We defined planning to quit cigarette smoking at follow-up as planning to quit in the next 6 months versus not planning to quit in the next 6 months. Those who responded ‘don’t know’ regarding their plans to quit at follow-up were categorized as not planning to quit in the next 6 months. Those who had already quit at follow-up and were not asked about their plans to quit were included in the sample as ‘planning to quit,’ and in a separate analysis, they were excluded from the sample. We did not impute missing data for any variables.

Statistical analysis

First, we assessed descriptive characteristics of our sample of daily cigarette smokers, stratified by cigarette quit plans at baseline. We compared groups using chi-squared tests. Next, we evaluated prevalence of vaping uptake between baseline and follow-up, stratified by cigarette quit plans at baseline. Then, we evaluated prevalence of cigarette cessation at follow-up as a function of vaping uptake between baseline and follow-up, stratified by cigarette quit plans at baseline. Last, we evaluated prevalence of planning to quit in the next six months at follow-up as a function of vaping uptake between baseline and follow-up, stratified by cigarette quit plans at baseline. Unweighted sample sizes are presented alongside weighted estimates.

We used generalized estimating equation (GEE) logistic regression analyses to evaluate the association between vaping uptake and smoking cessation (and separately, between vaping uptake and planning to quit in the next 6 months) using both assessment pairs (i.e., 2016–2018 and 2018–2020), stratified by baseline cigarette quit plans, and we evaluated the interactions between baseline cigarette quit plans and vaping uptake. We tested for statistical rather than ‘biologic’ interaction (see Knol et al., 200717) as our interest was in determining whether the estimate from the combination of the cigarette quit plans term and the vaping uptake term yielded a departure from the underlying form of our statistical model. We additionally attempted to evaluate whether these interactions varied by country, but many models failed to converge, some were not testable due to small cell sizes, and those that remained did not yield any significant country interactions for the main analyses and thus are not reported here. GEE allows for the assessment of change between baseline and follow-up from both assessment pairs in a single analysis while statistically controlling for interdependence among observations contributed by the same individuals, increasing statistical power.18–19 We specified the unstructured covariance and within-person correlation matrices and the binomial distribution of the dependent variables using the logit link function.

All GEE analyses were adjusted for country, sex, race/ethnicity, age group, SES, CPD, time in sample (i.e., the number of waves the respondent had completed), and assessment pair. We decided a priori to adjust for these covariates, and to categorize continuous variables such as age and CPD, consistent with prior ITC analyses and reporting of these descriptive data. All covariates were assessed at baseline of each assessment pair such that time-varying covariates varied by time. Those with missing data on covariates were excluded from analyses (n=52). All analyses were weighted using longitudinal weights that were rescaled for country and for cohort so that the weighted results presented here represent the population of cigarette smokers in each country. All analyses were conducted using STATA V16 software (StataCorp LP: College Station, TX.). Analysis plans were not pre-registered and results should be considered exploratory. This report follows the STROBE reporting guideline for cohort studies (https://www.equator-network.org/reporting-guidelines/strobe/).

RESULTS

Descriptive characteristics of adult daily cigarette smokers, stratified by cigarette quit plans at baseline

Among daily cigarette smokers who had not vaped in the past 6 months, 28% were planning to quit within the next 6 months, 34% were planning to quit sometime in the future beyond 6 months, 26% were not planning to quit at all, and 13% did not know whether they planned to quit. As shown in Table 1, males, those aged ≥55 years, those with lower SES (including each SES component – income and education), and those smoking more cigarettes per day were overrepresented among those who were not planning to quit. Those with higher quitting self-efficacy and greater desire to quit were overrepresented among those who were planning to quit in the next 6 months.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of adult daily cigarette smokers in the US, Canada, England, and Australia who had not vaped in the past 6 months at baseline, by cigarette quit plans (column percentages).

| Cigarette Quit Plans at Baseline |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Planning to quit within the next 6 months n=897 |

Planning to quit sometime in future, beyond 6 months n=1102 |

Not planning to quit n=937 |

Unknown plans to quit n=469 |

||||||||

| Descriptive Characteristics at Baseline | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | % | 95% CI | X2 | p-value | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Overall: N=3405 | 27.5 | 25.2–29.9 | 33.7 | 31.2–36.2 | 25.9 | 23.6–28.3 | 13.0 | 11.4–14.8 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Sex | Male (n=1557) | 52.0 | 47.1–56.9 | 49.9 | 45.4–54.4 | 63.1 | 57.7–68.2 | 45.8 | 38.9–52.9 | 6.8 | <.001 |

| Female (n=1848) | 48.0 | 43.1–52.9 | 50.1 | 45.6–54.6 | 36.9 | 31.8–42.3 | 54.2 | 47.1–61.1 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Race/ethnicity | White (n=3065) | 86.9 | 83.2–90.0 | 87.7 | 84.4–90.4 | 89.6 | 85.9–92.4 | 81.5 | 74.1–87.1 | 2.2 | 0.089 |

| non-White (n=340) | 13.1 | 10.1–16.8 | 12.3 | 9.6–15.6 | 10.5 | 7.6–14.1 | 18.5 | 12.9–25.9 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Age group | 18–24 (n=52) | 4.3 | 2.6–7.0 | 2.4 | 1.3–4.5 | 3.1 | 1.3–7.4 | 2.7 | 0.9–8.1 | 2.4 | 0.015 |

| 25–39 (n=426) | 36.6 | 31.3–42.2 | 33.8 | 29.0–38.9 | 27.8 | 22.2–34.3 | 26.1 | 19.2–34.5 | |||

| 40–54 (n=1055) | 30.6 | 26.7–34.8 | 33.3 | 29.5–37.3 | 27.2 | 23.0–31.9 | 29.6 | 23.8–36.2 | |||

| 55+ (n=1872) | 28.5 | 25.1–32.3 | 30.5 | 27.2–34.0 | 41.8 | 37.1–46.6 | 41.5 | 35.4–47.9 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Income | Low (n=891) | 18.8 | 15.5–22.7 | 24.0 | 20.2–28.1 | 32.8 | 27.8–38.1 | 27.5 | 22.1–33.7 | 4.5 | <.001 |

| Moderate (n=1074) | 28.5 | 24.4–33.0 | 31.5 | 27.4–35.9 | 31.7 | 27.2–36.6 | 32.2 | 26.1–39.0 | |||

| High (n=1235) | 47.7 | 42.8–52.7 | 40.4 | 36.1–44.8 | 31.3 | 26.5–36.7 | 30.7 | 24.9–37.2 | |||

| No answer (n=205) | 4.9 | 3.0–8.1 | 4.2 | 2.7–6.5 | 4.2 | 2.9–6.0 | 9.6 | 5.2–17.0 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Education | Low (n=1298) | 32.9 | 28.5–37.6 | 37.0 | 32.8–41.4 | 45.6 | 40.3–50.9 | 47.1 | 40.2–54.1 | 4.9 | <.001 |

| Moderate (n=1320) | 44.4 | 39.5–49.4 | 45.3 | 40.8–49.8 | 40.1 | 34.9–45.6 | 41.1 | 34.5–48.1 | |||

| High (n=768) | 22.7 | 18.8–27.2 | 17.3 | 14.4–20.7 | 13.5 | 11.0–16.5 | 10.3 | 7.3–14.3 | |||

| No answer (n=19) | 0.1 | 0.0–0.4 | 0.4 | 0.1–1.2 | 0.9 | 0.4–1.9 | 1.5 | 0.6–4.2 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| SES | Low (n=543) | 11.8 | 9.2–15.2 | 14.7 | 11.7–18.2 | 20.1 | 16.3–24.6 | 20.3 | 15.1–26.8 | 5.7 | <.001 |

| Moderate (n=1281) | 32.4 | 28.0–37.2 | 35.5 | 31.4–39.9 | 42.4 | 37.2–47.9 | 43.5 | 36.7–50.6 | |||

| High (n=1578) | 55.7 | 50.8–60.6 | 49.8 | 45.3–54.3 | 37.4 | 32.5–42.6 | 36.1 | 30.0–42.7 | |||

| Missing (n=3) | 0.1 | 0.0–0.4 | 0.0 | - | 0.1 | 0.1–0.5 | 0.1 | 0.0–0.7 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Country | US (n=897) | 20.9 | 17.4–24.9 | 26.7 | 23.0–30.6 | 31.9 | 27.4–36.8 | 35.3 | 28.8–42.4 | 7.0 | <.001 |

| Canada (n=759) | 34.2 | 30.0–38.7 | 28.4 | 24.9–32.1 | 14.9 | 12.0–18.3 | 23.8 | 19.0–29.4 | |||

| England (n=982) | 20.8 | 16.4–26.0 | 23.2 | 19.4–27.6 | 34.8 | 29.7–40.2 | 24.0 | 18.3–30.7 | |||

| Australia (n=767) | 24.1 | 20.1–28.5 | 21.8 | 18.1–26.0 | 18.5 | 14.6–23.2 | 16.9 | 12.4–22.7 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Cigarettes smoked per day | 1–10 cigarettes (n=1151) | 46.2 | 41.2–51.2 | 38.7 | 34.3–43.2 | 32.5 | 27.6–37.7 | 32.3 | 26.4–38.8 | 3.0 | 0.002 |

| 11–20 cigarettes (n=1696) | 42.3 | 37.5–47.2 | 48.6 | 44.2–53.1 | 49.5 | 44.2–54.9 | 53.2 | 46.3–60.0 | |||

| 21–30 cigarettes (n=450) | 9.9 | 7.8–12.6 | 10.3 | 8.4–12.6 | 14.9 | 11.1–19.6 | 11.4 | 8.4–15.2 | |||

| 31+ cigarettes (n=108) | 1.6 | 0.9–3.1 | 2.4 | 1.4–4.2 | 3.2 | 2.1–4.8 | 3.1 | 1.7–5.8 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Quitting self-efficacy | Not at all/slightly sure (n=1943) | 39.7 | 34.8–44.8 | 59.8 | 55.3–64.1 | 64.7 | 59.3–69.7 | 57.9 | 51.0–64.5 | 20.7 | <.001 |

| Moderately sure (n=855) | 38.6 | 34.0–43.4 | 28.4 | 24.4–32.7 | 13.7 | 10.7–17.5 | 18.0 | 13.6–23.5 | |||

| Very/extremely sure (n=394) | 20.4 | 16.8–24.7 | 9.4 | 7.0–12.5 | 10.4 | 7.8–13.9 | 8.7 | 5.0–14.7 | |||

| Don’t know (n=210) | 1.3 | 0.7–2.2 | 2.4 | 1.7–3.5 | 11.2 | 7.7–16.1 | 15.4 | 11.6–20.2 | |||

|

| |||||||||||

| Desire to quit | Not at all (n=476) | 0.6 | 0.2–2.1 | 0.8 | 0.4–1.7 | 43.8 | 38.7–49.2 | 4.8 | 2.5–9.2 | 83.6 | <.001 |

| A little (n=649) | 3.3 | 1.6–6.7 | 18.5 | 15.0–22.5 | 32.5 | 27.9–37.6 | 22.3 | 17.4–28.1 | |||

| Somewhat (n=1140) | 26.3 | 22.2–30.9 | 52.7 | 48.2–57.1 | 19.2 | 14.9–24.3 | 42.0 | 35.6–48.8 | |||

| A lot (n=1062) | 69.7 | 64.9–74.2 | 27.3 | 23.7–31.2 | 1.8 | 1.0–3.1 | 18.4 | 13.3–24.8 | |||

| Donť know (n=71) | 0.1 | 0.0–0.4 | 0.8 | 0.4–1.6 | 2.7 | 1.3–5.6 | 12.5 | 7.4–20.3 | |||

Table 1 notes: ns are unweighted and reflect the number of observations; %s and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are weighted.

Vaping uptake between baseline and follow-up as a function of cigarette quit plans at baseline

Overall, 13.5% (95%CI: 11.8–15.4) of daily cigarette smokers took up daily vaping, with daily vaping uptake highest among those who at baseline were planning to quit within the next 6 months (16.3% uptake, 95%CI: 13.0–20.3) and lowest among those who at baseline were not planning to quit at all (10.3% uptake 95%CI: 7.4–14.2) or who did not know whether they planned to quit (10.8% uptake, 95%CI: 7.6–15.1, Table 2).

Table 2.

Vaping uptake between baseline and follow-up as a function of cigarette quit plans at baseline among adult daily cigarette smokers in the US, Canada, England, and Australia who had not vaped in the past 6 months at baseline.

| Vaping Uptake between Baseline and Follow-up |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No vaping uptake |

Nondaily vaping uptake |

Daily vaping uptake |

|||||||||

| Cigarette Quit Plans at Baseline | n | % | 95% CI | n | % | 95% CI | n | % | 95% CI | x2 | p-value |

|

| |||||||||||

| Overall: N=3405 | 2149 | 62.9 | 60.4–65.4 | 803 | 23.6 | 21.5–25.9 | 453 | 13.5 | 11.8–15.4 | - | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Planning to quit within the next 6 months: n=897 (27% of sample) | 540 | 59.0 | 54.1–63.8 | 215 | 24.7 | 20.7–29.1 | 142 | 16.3 | 13.0–20.3 | ||

| Not planning to quit within next 6 months (note: this group is the aggregate of the groups beneath it): n=2508 (73% of sample) | 1609 | 64.4 | 61.4–67.3 | 588 | 23.2 | 20.7–25.9 | 311 | 12.4 | 10.5–14.6 | 2.4 | .089 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Planning to quit sometime in the future, beyond 6 months: n=1102 (34% of sample) |

631 | 57.8 | 53.3–62.2 | 308 | 27.6 | 23.7–31.8 | 163 | 14.6 | 11.7–18.1 | ||

| Not planning to quit: n=937 (26% of sample) | 682 | 72.6 | 67.5–77.0 | 161 | 17.1 | 13.5–21.4 | 94 | 10.3 | 7.4–14.2 | 4.3 | <.001 |

| Unknown plans to quit: n=469 (13% of sample) | 269 | 65.3 | 58.7–71.3 | 119 | 24.0 | 18.8–30.1 | 54 | 10.8 | 7.6–15.1 | ||

Table 2 notes: ns are unweighted and reflect the number of observations; %s and 95% confidence intervals (CI) are weighted.

Cigarette smoking cessation at follow-up as a function of vaping uptake, stratified by cigarette quit plans at baseline

Overall, cigarette smoking cessation rates at follow-up were highest among those who were initially planning to quit within the next 6 months (19.3% quit, 95%CI: 15.4–24.0) and were lowest among those who were initially not planning to quit at all (7.1% quit, 95%CI: 4.9–10.1, Table 3).

Table 3.

Cigarette smoking cessation at follow-up as a function of vaping uptake between baseline and follow-up among adult daily cigarette smokers in the US, Canada, England, and Australia who had not vaped in the past 6 months at baseline, stratified by cigarette quit plans at baseline.

| Cigarette Smoking Cessation at Follow-up1 |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cigarette Quit Plans at Baseline | Vaping Uptake between Baseline and Follow-up (inter-wave vaping uptake) | n | % (95% CI) | AOR2 (95% CI) |

|

| ||||

| Overall | Overall: N=3405 | 393 | 12.7 (10.9,14.6) | - |

|

| ||||

| Planning to quit within the next 6 months | Overall: n=897 | 155 | 19.3 (15.4,24.0) | - |

|

| ||||

| No vaping: n=540 | 80 | 16.8 (11.8,23.3) | ref | |

| Any vaping: n=357 | 75 | 23.0 (17.0,30.3) | 1.65 (0.93,2.92) | |

|

| ||||

| No vaping: n=540 | 80 | 16.8 (11.8,23.3) | ref | |

| Nondaily vaping: n=215 | 37 | 21.6 (14.1,31.7) | 1.50 (0.78,2.87) | |

| Daily vaping: n=142 | 38 | 25.1 (16.2,36.6) | 1.91 (0.91,4.00) | |

|

| ||||

| Not planning to quit within the next 6 months (note: this group is the aggregate of the three groups beneath it) | Overall: n=2508 | 238 | 10.1 (8.4,12.1) | - |

|

| ||||

| No vaping: n=1609 | 114 | 6.8 (5.3,8.8) | ref | |

| Any vaping: n=471 | 76 | 19.1 (13.7,25.9) | 3.20 (2.03,5.06) † | |

|

| ||||

| No vaping: n=1609 | 114 | 6.8 (5.3,8.8) | ref | |

| Nondaily vaping: n=588 | 44 | 7.3 (4.5,11.7) | 1.24 (0.68,2.27) | |

| Daily vaping: n=311 | 80 | 32.4 (24.6,41.3) | 8.58 (5.06,14.54) † | |

|

| ||||

| Planning to quit sometime in the future, beyond 6 months | Overall: n=1102 | 129 | 12.4 (9.7,15.8) | - |

|

| ||||

| No vaping: n=631 | 53 | 7.6 (5.5,10.5) | ref | |

| Any vaping: n=471 | 76 | 19.1 (13.7,25.9) | 4.02 (2.19,7.39) | |

|

| ||||

| No vaping: n=631 | 53 | 7.6 (5.5,10.5) | ref | |

| Nondaily vaping: n=308 | 30 | 10.1 (5.5,17.6) | 1.78 (0.87,3.65) | |

| Daily vaping: n=163 | 46 | 36.1 (25.0,49.0) | 10.88 (5.31,22.30) † | |

|

| ||||

| Not planning to quit | Overall: n=937 | 68 | 7.1 (4.9,10.1) | - |

|

| ||||

| No vaping: n=682 | 40 | 6.1 (3.7,10.1) | ref | |

| Any vaping: n=255 | 28 | 9.5 (5.9,15.1) | 1.73 (0.84,3.56) | |

|

| ||||

| No vaping: n=682 | 40 | 6.1 (3.7,10.1) | ref | |

| Nondaily vaping: n=161 | 5 | 1.0 (0.4,2.6) | 0.18 (0.06,0.55) † | |

| Daily vaping: n=94 | 23 | 23.5 (13.8,37.3) | 5.81 (2.60,13.00) ‡ | |

|

| ||||

| Unknown plans to quit3 | Overall: n=469 | 41 | 10.2 (6.9,14.9) | - |

|

| ||||

| No vaping: n=269 | 21 | 6.7 (3.8,11.4) | ref | |

| Any vaping: n=173 | 20 | 16.9 (9.9,27.3) | 3.23(1.24,8.41) | |

|

| ||||

| No vaping: n=269 | 21 | 6.7 (3.8,11.4) | ref | |

| Nondaily vaping: n=119 | 9 | 8.1 (3.4,17.9) | 1.46 (0.47,4.53) | |

| Daily vaping: n=54 | 11 | 36.5 (20.1,56.7) | 8.64 (3.05,24.46) † | |

Table 3 notes: ns are unweighted and reflect the number of observations; %s, 95% confidence intervals (CI), and adjusted odds ratios (AOR) are weighted.

GEE logistic regression analyses were used to assess the association between uptake of vaping (between baseline and follow-up) and cigarette cessation (at follow-up) among adult daily cigarette smokers who had not vaped in the past 6 months at baseline, stratified by cigarette quit plans at baseline, over two periods of time (i.e., Wave 1–Wave 2, and Wave 2–Wave 3), including up to two sets of observations per individual and statistically controlling for the correlation among observations contributed by the same individuals.

Cigarette cessation at follow-up was defined as less than monthly cigarette smoking (vs. monthly/weekly/daily cigarette smoking) among those who were daily cigarette smokers at baseline.

Analyses were adjusted for country, biological sex, race/ethnicity (white, non-white), age group (18–24, 25–39, 40–54, 55+ years), SES (low, moderate, high), cigarettes smoked per day, time in sample, and wave; all covariates were assessed at baseline; GEE models were fitted specifying the unstructured covariance and within-person correlation matrices.

Model convergence not achieved for those with unknown plans to quit (for either model)

Association is significantly different from analogous association among those planning to quit within the next 6 months (p=<0.01 for interaction).

Association is significantly different from analogous association among those planning to quit within the next 6 months (p=<0.06 for interaction).

A significant interaction was found between cigarette quit plans at baseline and vaping uptake in the association with cigarette smoking cessation. Among smokers who at baseline were planning to quit within the next 6 months, daily vaping uptake was associated with a nearly two-fold higher odds of smoking cessation though this estimate did not reach statistical significance (AOR= 1.91, 95%CI: 0.91–4.00), whereas among those who at baseline were not planning to quit within the next 6 months, those who took up daily vaping experienced over 8-fold higher odds of quitting smoking compared to those who did not take up vaping (AOR= 8.58, 95%CI: 5.06–14.54; Table 3). When disaggregating those who were not planning to quit within the next 6 months, the strongest associations between uptake of daily vaping and smoking cessation were found among those who at baseline were planning to quit sometime in the future beyond six months (AOR= 10.88, 95%CI: 5.31–22.30) and those who at baseline did not know whether they planned to quit (AOR= 8.64, 95%CI: 3.05–24.46; Table 3).

Uptake on nondaily vaping was negatively associated with smoking cessation among those who at baseline were not planning to quit at all (AOR=0.18, 95%CI: 0.06–0.55); no other significant differences were observed (Table 3). Findings were consistent in sensitivity analyses in which the definition of smoking cessation considered those who smoked less than monthly as having not achieved cessation, which changed the value of the cessation outcome for only 16 people.

Planning to quit cigarette smoking at follow-up as a function of vaping uptake, stratified by cigarette quit plans at baseline

A significant interaction between cigarette quit plans at baseline and vaping uptake was found in the association with change in plans to quit smoking. Among smokers who at baseline were planning to quit within the next 6 months, there was no statistically significant association between daily vaping uptake and change in plans to quit smoking (AOR= 0.82, 95%CI: 0.44–1.55). By contrast, among those who at baseline were not planning to quit in the next 6 months, those who took up daily vaping had an over 6-fold higher odds of change to be planning to quit smoking compared to those who did not take up vaping (AOR= 6.32, 95%CI: 4.17–9.59). When disaggregating those who were not planning to quit within the next 6 months, the strongest association between uptake of daily vaping and change to be planning to quit smoking was found among those who at baseline were not planning to quit smoking at all (AOR= 10.12, 95%CI: 4.46–22.93).

Finally, in a sensitivity analysis excluding those who had quit smoking at follow-up, we still found a statistically significant positive association between daily vaping uptake and change in plans to quit smoking among those who at baseline were not planning to quit in the next 6 months (AOR= 3.61, 95%CI: 1.92–6.79) and among the subgroup who at baseline were not planning to quit at all (AOR= 11.65, 95%CI: 3.48–38.99; Table 4).

Table 4.

Planning to quit cigarette smoking at follow-up as a function of vaping uptake between baseline and follow-up among adult daily cigarette smokers in the US, Canada, England, and Australia who had not vaped in the past six months at baseline, stratified by cigarette quit plans at baseline.

| Planning to Quit Smoking within the next 6 months at Follow-up (quitters included)2 |

Planning to Quit Smoking within the next 6 months at Follow-up (quitters excluded)3 |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cigarette Quit Plans at Baseline1 | Vaping Uptake between Baseline and Follow-up (inter-wave vaping uptake) | n | % (95% CI) | AOR4 (95% CI) | Vaping Uptake between Baseline and Follow-up (inter-wave vaping uptake) | n | % (95% CI) | AOR4 (95% CI) |

|

| ||||||||

| Overall | Overall: N=3405 | 1130 | 34.7 (32.2,37.2) | - | Overall: n=3012 | 742 | 25.3 (23.0,27.7) | - |

|

| ||||||||

| Planning to quit within the next 6 months | Overall: n=897 | 612 | 70.4 (65.8,74.7) | - | Overall: n=742 | 457 | 63.3 (58.0,68.3) | - |

|

| ||||||||

| No vaping: n=540 | 359 | 69.9 (64.1,75.2) | ref | No vaping: n=460 | 279 | 63.9 (57.3,69.9) | ref | |

| Any vaping: n=357 | 253 | 71.1 (63.3,77.9) | 1.05 (0.66,1.67) | Any vaping: n=282 | 178 | 62.5 (53.5,70.7) | 0.92 (0.57,1.48) | |

|

| ||||||||

| No vaping: n=540 | 359 | 69.9 (64.1,75.2) | ref | No vaping: n=460 | 279 | 63.9 (57.3,69.9) | ref | |

| Nondaily vaping: n=215 | 150 | 74.2 (65.0,81.7) | 1.23 (0.72,2.09) | Nondaily vaping: n=178 | 113 | 67.1 (56.5,76.2) | 1.12 (0.65,1.93) | |

| Daily vaping: n=142 | 103 | 66.4 (52.6,77.9) | 0.82 (0.44,1.55) | Daily vaping: n=104 | 65 | 55.2 (40.1,69.3) | 0.66 (0.34,1.28) | |

|

| ||||||||

| Not planning to quit within the next 6 months (note: this group is the aggregate of the 3 groups beneath it) | Overall: n=2508 | 518 | 21.1 (18.8,23.7) | - | Overall: n=2270 | 285 | 14.4 (10.5,14.5) | - |

|

| ||||||||

| No vaping: n=1609 | 276 | 15.9 (13.6,18.6) | ref | No vaping: n=1495 | 164 | 9.8 (8.0,12.0) | ref | |

| Any vaping: n=899 | 242 | 30.6 (25.9,35.6) | 2.62 (1.90,3.63) † | Any vaping: n=775 | 121 | 17.4 (13.5,22.2) | 2.03 (1.36,3.03) ‡ | |

|

| ||||||||

| No vaping: n=1609 | 276 | 15.9 (13.6,18.6) | ref | No vaping: n=1495 | 164 | 9.8 (8.0,12.0) | ref | |

| Nondaily vaping: n=588 | 119 | 20.3 (15.9,25.6) | 1.45 (1.01,2.10) ‡ | Nondaily vaping: n=544 | 77 | 14.1 (10.7,18.5) | 1.55 (1.03,2.32) | |

| Daily vaping: n=311 | 123 | 49.8 (41.1,58.4) | 6.32 (4.17,9.59) † | Daily vaping: n=231 | 44 | 25.9 (16.5,38.2) | 3.61 (1.92,6.79) † | |

|

| ||||||||

| Planning to quit sometime in the future, beyond 6 months | Overall: n=1102 | 341 | 30.8 (26.9,35.0) | - | Overall: n=973 | 213 | 21.0 (17.6,24.9) | - |

|

| ||||||||

| No vaping: n=631 | 171 | 24.8 (20.5,29.6) | ref | No vaping: n=578 | 118 | 18.6 (14.7,23.2) | ref | |

| Any vaping: n=471 | 170 | 39.1 (32.4,46.2) | 2.18 (1.45,3.27) ‡ | Any vaping: n=395 | 95 | 24.8 (18.9,31.7) | 1.43 (0.90,2.28) | |

|

| ||||||||

| No vaping: n=631 | 171 | 24.8 (20.5,29.6) | ref | No vaping: n=578 | 118 | 18.6 (14.7,23.2) | ref | |

| Nondaily vaping: n=308 | 91 | 29.9 (22.8,38.1) | 1.41 (0.89,2.23) | Nondaily vaping: n=278 | 62 | 22.1 (16.1,29.4) | 1.24 (0.75,2.04) | |

| Daily vaping: n=163 | 79 | 56.5 (45.0,67.3) | 4.52 (2.63,7.77) † | Daily vaping: n=117 | 33 | 31.9 (19.5,47.5) | 2.02(0.98,4.18)‡ | |

|

| ||||||||

| Not planning to quit | Overall: n=937 | 95 | 11.0 (8.0,15.0) | - | Overall: n=869 | 31 | 4.5 (2.5,8.0) | - |

|

| ||||||||

| No vaping: n=682 | 58 | 8.4 (5.5,12.4) | ref | No vaping: n=642 | 20 | 2.6 (1.4,4.7) | ref | |

| Any vaping: n=255 | 37 | 18.0 (11.0,28.1) | 3.05 (1.44,6.47) ‡ | Any vaping: n=227 | 11 | 9.8 (3.9,22.4) | 5.07 (1.84,13.93) ‡ | |

|

| ||||||||

| No vaping: n=682 | 58 | 8.4 (5.5,12.4) | ref | No vaping: n=642 | 20 | 2.6 (1.4,4.7) | ref | |

| Nondaily vaping: n=161 | 9 | 4.5 (1.9,10.5) | 0.72 (0.25,2.06) | Nondaily vaping: n=156 | 5 | 3.7 (1.3,10.1) | 2.41 (0.73,7.98) | |

| Daily vaping: n=94 | 28 | 40.4 (24.7,58.5) | 10.12 (4.46,22.93) † | Daily vaping: n=71 | 6 | 22.9 (7.5,52.0) | 11.65 (3.48,38.99) † | |

|

| ||||||||

| Unknown plans to quit5 | Overall: n=469 | 82 | 16.3 (12.2,21.3) | - | Overall: n=428 | 41 | 6.7 (4.5,9.9) | - |

|

| ||||||||

| No vaping: n=296 | 47 | 12.4 (8.5,17.8) | ref | No vaping: n=275 | 26 | 6.1 (3.7,9.9) | ref | |

| Any vaping: n=173 | 35 | 23.5 (15.6,33.9) | 2.35 (1.12,4.94) | Any vaping: n=153 | 15 | 8.0 (4.2,14.8) | 1.28 (0.49,3.34) | |

|

| ||||||||

| No vaping: n=296 | 47 | 12.4 (8.5,17.8) | ref | No vaping: n=275 | 26 | 6.1 (3.7,9.9) | ref | |

| Nondaily vaping: n=119 | 19 | 14.4 (8.1,24.5) | 1.34 (0.61,2.95) | Nondaily vaping: n=110 | 10 | 6.9 (3.3,14.1) | 1.22 (0.46,3.26) | |

| Daily vaping: n=54 | 16 | 43.9 (26.9,62.4) | 5.45 (2.18,13.58) † | Daily vaping: n=43 | 5 | 11.6 (3.4,32.8) | 1.44 (0.29,7.27)† | |

Table 4 notes: ns are unweighted and reflect the number of observations; %s, 95% confidence intervals (CI), and adjusted odds ratios (AOR) are weighted.

GEE logistic regression analyses were used to assess the association between uptake of vaping (between baseline and follow-up) and planning to quit cigarette smoking at follow-up among adult daily cigarette smokers who had not vaped in the past six months at baseline, stratified by plans to quit smoking at baseline, over two periods of time (i.e., Wave 1–Wave 2, and Wave 2–Wave 3), including up to two sets of observations per individual and statistically controlling for the correlation among observations contributed by the same individuals.

Those who were planning to quit within the next 6 months at baseline includes those who were planning to quit within one month at baseline and those who were planning to quit between 1–6 months at baseline; the numerator of the outcome for this group reflects maintaining quit plans. The numerators of the outcome for the other baseline quit intentions group reflect changing to have quit plans.

Planning to quit smoking within the next 6 months at follow-up was coded yes for those who were not smoking at least monthly and were not asked about their quitting plans (so as to retain in the analysis those who had quit smoking).

Those who had quit smoking were excluded from analysis.

Analyses were adjusted for country, biological sex, race/ethnicity (white, non-white), age group (18–24, 25–39, 40–54, 55+ years), SES (low, moderate, high), cigarettes smoked per day, time in sample, and wave; all covariates were assessed at baseline; GEE models were fitted specifying the unstructured covariance and within-person correlation matrices.

Model convergence not achieved for those with unknown plans to quit (for any model)

Association is significantly different from analogous association among those planning to quit within the next 6 months (p=<0.01 for interaction).

Association is significantly different from analogous association among those planning to quit within the next 6 months (p=<0.05 for interaction).

DISCUSSION

The key finding from this study is that there is a strong positive association between vaping uptake and cigarette smoking cessation among smokers with no initial plans to quit smoking. Specifically, those not planning to quit in the next 6 months who started vaping daily experienced a 32% cigarette quit rate compared to a 7% cigarette quit rate among their counterparts who did not take up vaping. These findings are consistent with US PATH Study findings2,3 and indicate that studies that focus on smokers who are already planning or attempting to quit may underestimate a potential benefit of daily vaping for smoking cessation at the population-level.

One mechanism by which vaping may be positively associated with smoking cessation could be by changing motivation and self-efficacy for quitting among those initially not interested in quitting smoking. Our findings show that vaping uptake was associated with change in plans to quit smoking among those initially not planning to quit, which is consistent with the one other population-based study that investigated this question.2 Further, in a sensitivity analysis among those who at baseline did not plan to quit at all and continued to smoke at follow-up, we found that they experienced an 11-fold greater odds of planning to quit at follow-up when they took up daily vaping, suggesting that there could be further increases in smoking cessation rates among this ‘hard-to-reach’ group of smokers in the longer term. Importantly, our findings show that these smokers tended to be male, older, smoked more cigarettes per day, and were of lower socioeconomic status than their counterparts who were initially planning to quit.

It is also possible that smokers in our study changed their plans to quit after baseline and subsequently began vaping as a method of quitting. We had between 18–24-month intervals between surveys and we could not assess whether quit intentions changed first or whether vaping status changed first. Regardless of the directionality, our findings show contemporaneous associations between moving from daily smoking to no smoking alongside moving from no vaping to daily vaping specifically among those who were initially not planning to quit smoking. These findings are consistent with the one other population study that evaluated this question among smokers not planning to quit,3 as well as experimental studies that have shown that giving nicotine vaping products to smokers unmotivated to quit increases their motivation to quit,4–6 and is associated with reductions in their cigarette smoking.6–7

Consistent with other studies in the literature, we found no association between uptake of nondaily vaping and smoking cessation.20–22 This may reflect that nondaily vaping was not associated with change in quit intentions and/or may reflect that nondaily vaping did not provide sufficient nicotine to serve as a substitute for those who were daily cigarette smokers, as discussed previously by Gravely et al. (2021).20 Importantly, we found that uptake of nondaily vaping was nearly twice as common as daily vaping uptake, meaning that the majority of vaping uptake occurring among smokers in the population is not expected to yield smoking cessation gains.

When considering differences in the magnitudes of associations between daily vaping uptake and smoking cessation when disaggregating the groups that did not have plans to quit in the next 6 months, we found that those who were least definitive in their plans (i.e., those who were planning to quit beyond 6 months or did not know) experienced the greatest relative increases in smoking cessation when they took up daily vaping. While additional studies are needed to understand our findings more fully, smokers without definitive plans to quit tended to want to quit but had low quitting self-efficacy prior to vaping uptake, thus it is plausible that uptake of vaping among this group may help them to overcome expectancies that living without cigarettes is too challenging.23

While studies on use of nicotine replacement therapy (NRT) and smoking cessation typically focus on cessation aid effectiveness when used during a quit attempt13,24–25 (see also Figure 1), our findings suggest that evaluation of use of NVPs and smoking cessation should also include those not planning to quit. With regard to our findings among smokers who were initially planning to quit, it is possible that those who did not take up vaping may have been more likely to use NRT or other cessation aids than their counterparts who took up daily vaping. We found that those planning to quit smoking who did not take up vaping experienced a 17% smoking cessation rate whereas only 7% of those not planning to quit who did not take up vaping went on to quit smoking. That is, the difference in smoking cessation rates between those who do and do not plan to quit smoking appear to be driven by differences in cessation rates among those who do not take up vaping. In other words, daily vaping uptake is associated with similar smoking cessation rates for those who do and do not plan to quit.

Limitations

In this population-based study, we were not able to ascertain the temporal ordering of vaping uptake and change in plans to quit following baseline assessment, and our findings should not be interpreted as indicating causal associations. We were also not able to ascertain a measure of inter-wave NRT/other cessation aid uptake consistent with our measure of inter-wave vaping uptake and thus we could not evaluate whether/to what extent other aid use may confound our findings for vaping use. Sample sizes were also generally small, owing in part to the follow-up timeframe eligibility requirement, which was necessary to ascertain inter-wave vaping uptake when including nonrecent vapers in the sample given the timeframes for which respondents were asked about their prior vaping experiences; however, this reduced our statistical power. Lastly, many models to test for country-by-vaping uptake interactions failed to converge and others were not statistically testable owing to some very small cell sizes. Future research with additional waves of data will increase statistical power to test for country interactions and to detect additional significant associations if they exist and will also allow for the assessment of smoking cessation in the longer-term. Future research can also evaluate type of vaping products used and amount of nicotine consumed, which may be particularly informative for nicotine vaping product regulation.

Conclusions

For daily cigarette smokers who are not planning to quit smoking, uptake of daily vaping is associated with higher smoking cessation rates compared to no uptake of vaping. Smokers not planning to quit tend to be older, heavier smokers of lower socioeconomic status. Studies focused exclusively on smokers who are already planning or attempting to quit may underestimate a potential benefit of daily vaping for smoking cessation at the population level, including potential to reduce disparities in smoking rates. Lastly, only daily vaping was associated with smoking cessation, suggesting that vaping company marketing practices, vaping policies/restrictions, and public health education campaigns could be undertaken to support smokers’ use of vaping products on a daily basis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to acknowledge and thank all those that contributed to the International Tobacco Control Four Country Smoking and Vaping (ITC 4CV) Survey: all study investigators and collaborators, the project staff at their respective institutions, and all respondents who took part in the surveys.

Funding:

This study was supported by grants from the US National Cancer Institute (P01 CA200512), the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (FDN-148477), and by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (GNT 1106451). Additional support to KAK and AH was provided by Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center and the US National Cancer Institute (P30CA016056). Additional support to GTF was provided by a Senior Investigator Award from the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research and the Canadian Cancer Society O. Harold Warwick Prize. KE is the recipient of fellowship funding from the Society for the Study of Addiction. The sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit for publication.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests: KMC has in the past and continues to serve as a paid expert witness in litigation filed against cigarette manufacturers. DH has served as a paid expert witness on behalf of governments and public health authorities in legal challenges against tobacco and vaping companies. GTF has served as an expert witness or consultant for governments defending their country’s policies or regulations in litigation. GTF and SG served as paid expert consultants to the Ministry of Health of Singapore in reviewing the evidence on plain/standardized packaging. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the NHMRC, or the other funding agencies. None of the other authors has any conflict of interest to declare.

Ethics: Study questionnaires and materials were reviewed and provided clearance by Research Ethics Committees at the following institutions: University of Waterloo (Canada, ORE#20803/30570, ORE#21609/30878), King’s College London, UK (RESCM-17/18–2240), Cancer Council Victoria, Australia (HREC1603), University of Queensland, Australia (2016000330/HREC1603); and Medical University of South Carolina (waived due to minimal risk). All participants provided consent to participate.

Data availability statement:

The data are jointly owned by a third party in each country that collaborates with the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation (ITC) Project. Data from the ITC Project are available to approved researchers 2 years after the date of issuance of cleaned data sets by the ITC Data Management Centre. Researchers interested in using ITC data are required to apply for approval by submitting an International Tobacco Control Data Repository (ITCDR) request application and subsequently to sign an ITCDR Data Usage Agreement. The criteria for data usage approval and the contents of the Data Usage Agreement are described online (http://www.itcproject.org). The authors of this paper obtained the data following this procedure. This is to confirm that others would be able to access these data in the same manner as the authors. The authors did not have any special access privileges that others would not have.

REFERENCES

- 1.Wang RJ, Bhadriraju S, Glantz SA. E-cigarette use and adult cigarette smoking cessation: A meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2020: e1–e17. 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kasza KA, Edwards KC, Anesetti-Rothermel A, et al. E-cigarette use and change in plans to quit cigarette smoking among adult smokers in the United States: Longitudinal findings from the PATH Study 2014–2019, Addictive Behaviors. 2021; pre-proof. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kasza KA, Edwards KC, Kimmel HL, et al. Association of e-Cigarette use with Discontinuation of Cigarette Smoking Among Adult Smokers Who Were Initially Never Planning to Quit. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(12):e2140880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wagener TL, Meier E, Hale JL, et al. Pilot investigation of changes in readiness and confidence to quit smoking after e-cigarette experimentation and 1 week of use. Nicotine Tob Res. 2014; 16(1):108–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carpenter MJ, Heckman BW, Wahlquist AE, et al. A naturalistic, randomized pilot trial of e-cigarettes: Uptake, exposure, and behavioral effects. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017; 26(12); 1795–803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pearson JL, Zhou Y, Smiley SL, et al. Intensive longitudinal study of the relationship between cigalike e-cigarette use and cigarette smoking among adult cigarette smokers without immediate plans to quit smoking. Nicotine Tobacco Res. 2021; 23(3): 527–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foulds J, Cobb CO, Yen M-S, et al. Effect of Electronic Nicotine Delivery Systems on Cigarette Abstinence in Smokers with no Plans to Quit: Exploratory Analysis of a Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021. Nov 26:ntab247. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntab247. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34850164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pierce JP, Benmarhnia T, Chen R, et al. Role of e-cigarettes and pharmacotherapy during attempts to quit cigarette smoking: the PATH Study 2013–16. PLoS One. 2020;15(9):e0237938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaplan B, Galiatsatos P, Breland A, Eissenberg T, Cohen JE. Effectiveness of ENDS, NRT and medication for smoking cessation among cigarette-only users: a longitudinal analysis of PATH Study wave 3 (2015–2016) and 4 (2016–2017), adult data. Tobacco Control. 2021; 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown J, Beard E, Kotz D, Michie S, West R. Real-world effectiveness of e-cigarettes. Addiction. 2014; 109:1531–1540. 10.1111/add.12623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gilpin E, Pierce JP. Measuring smoking cessation: problems with recall in the 1990 California Tobacco Survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 1994; 3: 613–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Borland R, Partos TR, Cummings KM. Systematic biases in cross-sectional community studies may underestimate the effectiveness of stop-smoking medications. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012; doi: 10.1093/ntr/nts002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kasza KA, Hyland AJ, Borland R, et al. Effectiveness of stop-smoking medications: Findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Addiction. 2013; 108, 193–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ITC Project. ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey, Wave 2 (2018) Technical Report. University of Waterloo, Waterloo, ON, Canada; Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina, USA; Cancer Council Victoria, Melbourne, Australia; the University of Queensland, Australia; King’s College London, London, UK. Available online: https://itcproject.org/methods/technical-reports/itc-four-country-smoking-and-vaping-survey-wave-2-4cv2-technical-report/ [Google Scholar]

- 15.ITC Project. (2020, October). ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey, Wave 3 (4CV3, 2020) Preliminary Technical Report. University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada; Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina, United States; Cancer Council Victoria, Melbourne, Australia; the University of Queensland, Australia; King’s College London, London, United Kingdom. https://itcproject.org/methods/technical-reports/itc-four-country-smoking-and-vaping-survey-4cv-wave-3-2020-preliminary-technical-report-oct-2020/ [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thompson ME, Fong GT, Boudreau C, et al. Methods of the ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Survey, Wave 1 (2016). Addiction. 2019; 114, 6–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Knol MJ, van der Tweel I, Grobbee DE, et al. Estimating interaction on an additive scale between continuous determinants in a logistic regression model. 2007. International Journal of Epidemiology. 2007; 36(5):1111–1118. 10.1093/ije/dym157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liang K-Y, Zeger SL. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika. 1986; 73:13–22. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hardin JW, Hilbe JM. Generalized estimating equations. Boca Raton, FL: Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gravely S, Meng G, Hammond D, et al. Nicotine vaping product initiation, frequency of use, and progression towards smoking cessation relative to non-vapers: Findings from the ITC Four Country Smoking and Vaping Surveys. (under review at Addictive Behaviors; ). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kalkhoran S, Chang Y, Rigotti NA. Electronic cigarette use and cigarette abstinence over two years among U.S. Smokers in the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study. Nicotine Tobacco Res. 2020;22(5):728–733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glasser A, Vojjala M, Cantrell J, et al. Patterns of e-cigarette use and subsequent cigarette smoking cessation over two years (2013/2014 to 2015/2016) in the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020. 10.1093/ntr/ntaa182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carter S, Borland R. Finding the Strength to Kill Your Best Friend: Smokers Talk about Smoking and Quitting. Australian Cessation Consortium & GlaxoSmithKline Consumer Healthcare, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilpin EA, Messer K, Pierce JP. Population effectiveness of pharmaceutical aids for smoking cessation: what is associated with increased success? Nicotine Tob Res. 2006; 8:661–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.West R, Zhou X. Is nicotine replacement therapy for smoking cessation effective in the ‘real world’? Findings from a prospective multinational cohort study. Thorax. 2007; 62: 998–1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data are jointly owned by a third party in each country that collaborates with the International Tobacco Control Policy Evaluation (ITC) Project. Data from the ITC Project are available to approved researchers 2 years after the date of issuance of cleaned data sets by the ITC Data Management Centre. Researchers interested in using ITC data are required to apply for approval by submitting an International Tobacco Control Data Repository (ITCDR) request application and subsequently to sign an ITCDR Data Usage Agreement. The criteria for data usage approval and the contents of the Data Usage Agreement are described online (http://www.itcproject.org). The authors of this paper obtained the data following this procedure. This is to confirm that others would be able to access these data in the same manner as the authors. The authors did not have any special access privileges that others would not have.