Abstract

Aim:

In this study, we investigated how platelets and aorta contribute to the creation and maintenance of a prothrombotic state in an experimental model of postmenopausal hypertension in ovariectomized rats.

Methods:

Bilateral ovariectomy was performed in both 14-week-old female spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) and normotensive Wistar Kyoto (WKY) rats. The animals were kept in phytoestrogen free diet. Vascular parameters, platelet, coagulation and aortic prothrombotic functions and mechanisms were assessed.

Results:

Exacerbated platelet aggregation was observed in both SHR and WKY animals after ovariectomy. The mechanism was related to aortic COX2 downregulation and reduction in AMP, ADP, and ATP hydrolysis in serum and platelets. A procoagulant potential was observed in plasma from ovariectomized rats and this was confirmed by kallikrein and factor Xa generation in aortic rings. Aortic rings derived from ovariectomized SHR presented a greater thrombin generation capacity compared to equivalent rings from WKY animals. The mechanism involved tissue factor and PAR-1 upregulation as well as an increase in extrinsic coagulation and fibrinolysis markers in aorta and platelets. Aortic smooth muscle cells pre-treated with a plasma pool derived from estrogen-depleted animals developed a procoagulant profile with tissue factor upregulation. This procoagulant profile was dependent on inflammatory signalling, since NFκB inhibition attenuated the procoagulant activity and tissue factor expression.

Conclusions:

A prothrombotic phenotype was observed in both WKY and SHR ovariectomized rats being associated with platelet hyperreactivity and tissue factor upregulation in aorta and platelets. The mechanism involves proinflammatory signalling that supports greater thrombin generation in aorta and vascular smooth muscle cells.

Keywords: Estrogen, hypertension, menopause, platelet, tissue factor, thrombosis

1. Introduction

The arterial vascular wall contributes to thrombotic complications in a variety of disease states, including but not limited to hypertension, atherosclerosis, diabetes, stroke, and sepsis (Esmon and Esmon, 2011; Lacolley et al., 2012). Vascular wall cells (mainly endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells) can generate a hypercoagulable state by supporting procoagulant enzyme formation (Pawlinski et al., 2004). The vascular wall also functionally modulates and interacts with tissue factor expressing cells that participate in thrombus growth such as platelets, neutrophils, and monocytes (Grover and Mackman, 2018). In hypertension, experimental evidence suggests a hemostatic balance impairment in vasculature. Spontaneously hypertensive rats (SHR) exhibited accelerated FeCl3-induced thrombus formation in carotid arteries (Ait Aissa et al., 2015). Accordingly, vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) supported a greater thrombin generation capacity when compared to VSMCs from normotensive control rats (Ait Aissa et al., 2015). Clinical studies also have reported higher plasma levels of D-dimers, fibrinogen, thrombin-antithrombin complex (TAT), and FVII in hypertensive patients compared to normotensive individuals (Arikan and Sen, 2005; Junker et al., 1998). Moreover, plasma from hypertensive patients has enhanced thrombin generation capacity compared to healthy controls (Elias et al., 2019).

Regarding the prothrombotic events in postmenopausal women, the contribution of cellular and molecular mechanisms involving the vascular wall is still unclear. Gender differences in the risk of cardiovascular diseases are well known (Knowlton and Lee, 2012). Premenopausal women have lower risk than men of the same age, however, this apparent cardio protection disappears with the onset of menopause (Knowlton and Lee, 2012). Indeed, thromboembolic and coronary heart diseases are the leading cause of death in women after loss of ovarian function and the risk is even higher when associated with hypertension, obesity, diabetes, or coagulation disorders during menopause (Anagnostis et al., 2018).

Since menopause is characterized by a natural decline in estrogen production, this hormone has been implicated in several pathophysiological aspects of the vascular wall. Estrogen depletion is associated with changes in lipid metabolism, increased vascular and cardiac oxidative stress, reduced nitric oxide (NO) availability, and reduced vascular reactivity response to vasodilators (Barp et al., 2012; Knowlton and Lee, 2012; Wassmann et al., 2001). In fact, both estrogen receptor (ER) subtypes (ERα and Erβ) are expressed in endothelial and VSMCs. The activation of both receptors mediates NO production (Knowlton and Lee, 2012). Systemically, the decrease in estrogen production is associated with a rise in arterial blood pressure in rat models of ovariectomy (Fang et al., 2001; Harrison-Bernard et al., 2003; Ito et al., 2006; Peng et al., 2003). The angiotensin system seems to be an important mechanism, since estrogens can regulate angiotensinogen, renin, angiotensin II (Ang II) receptors AT1 and AT2 expression, and aldosterone production (Ahmad et al., 2018; Hoshi-Fukushima et al., 2008). AT1 expression increases in blood vessels, kidney, and brain stem in estrogen-depleted SHR (Ito et al., 2006) and, in the heart, estrogen loss causes diastolic dysfunction by altering cardiomyocytes relaxation properties (Zhao et al., 2014). Interestingly, Ahmad et al., 2018 also found that chymase is the main Ang II generating enzyme in cardiomyocytes isolated from ovariectomized SHR and cardiovascular dysfunction positively correlates with an increased chymase activity in this model.

Together with systemic blood pressure changes and Ang II involvement, platelet hyperreactivity has also been described in experimental models of menopausal hypertension (Otsuka et al., 1997; Sasaki et al., 2000). Platelets derived from salt sensitive SHR ovariectomized rats show an increased aggregatory response to classical agonists, which correlates with the rise in blood pressure levels (Otsuka et al., 1997; Sasaki et al., 2000). Once Ang II has prothrombotic effects, this may be one of the mechanisms involved (Celi et al., 2010; Mogielnicki et al., 2005). However, it is not well-understood how platelets, aorta, and VSMCs interact to create and maintain a prothrombotic state after estrogen level drops down. For this purpose, we designed a menopausal hypertension model in which bilateral ovariectomy surgery was performed in 14-week-old female SHR and normotensive Wistar Kyoto (WKY) rats fed with a phytoestrogen free diet. After 50 days of ovariectomy surgery, both WKY and SHR animals evolved to a vascular prothrombotic state associated with nucleotide metabolizing system down-regulation, platelet hyperreactivity, and tissue factor expression up-regulation in both aorta and platelets. We found that aorta and vascular cells are important in supporting procoagulant enzyme assembly and generation by a mechanism that was significantly exacerbated in hypertensive aorta and was dependent of tissue factor and NFκB-mediated proinflammatory signalling.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

Twenty Wistar Kyoto (WKY) and 20 spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) female rats were used in this study. The animals (60-days old, weighting 170-200 g) were acquired from the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul Animal House (Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil) and maintained throughout the experiment (90 days total period) in the animal facility of our institution at the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil), following the Brazilian Law number 11.794/2008, which provides guidance and regulation for scientific research involving animals. Animals were kept at 20–24 °C in a 40-60 % relative air humidity environment with 12 h dark/light cycle and free access to water and food. During their first 60 days, animals received regular standard rodent chow and in the next 90 days, they received a soy-free based diet (PRAGSOLUÇÕES, SP, Brazil) to avoid phytoestrogens interference. All the procedures involving animals were carried out according to the Brazilian Guideline for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific and Educational Purposes (DBCA, RN 30/2016) as stated by the CONCEA (National Council for Control of Animal Experimentation). Our experimental protocol was approved by the Institute's Animal Ethics Committee of the Experimental Research Center at Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil (protocol number 19001/2019).

2.2. Experimental design

An experimental model of postmenopausal hypertension in ovariectomized rats was developed (Fig. 1A). The animals arrived at our institution 60 days after birth and this date was considered as day zero of our protocol. At day 40 (with approximately 14 weeks of age), the animals were randomly assigned to undergo either bilateral ovariectomy (OVX) or SHAM surgery (referred here as gonadal-intact animals). The experimental groups (n = 10/group) were as follows: (i) Wistar Kyoto rats – SHAM operated (WKY-SHAM); (ii) Wistar Kyoto rats – ovariectomized (WKY-OVX); (iii) Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats – SHAM operated (SHR-SHAM); and (iv) Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats – ovariectomized (SHR-OVX). At day 90 (50 days after surgery), the protocol was completed and the animals were euthanised for sample collection. Five days before either surgery (at day 35) or euthanasia (at day 85), blood pressure and 17-β estradiol levels were measured. 17-β estradiol was measured by a competitive ELISA-like immunoassay following the manufacturer instructions (E2 ELISA kit, CEA461Ge, Cloud-Clone Corp., Houston, TX, USA). On the same days of blood pressure measurements, a vaginal smear was also collected for estrous cycle phase evaluations. All animals submitted to OVX surgery were in the diestrous phase to avoid metabolic variations. During the entire protocol rats were weighed once a week.

Figure 1. Experimental model of menopausal hypertension.

(A) Twenty female spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) and 20 normotensive Wistar Kyoto (WKY) rats arrived at our institution 60 days after birth. This date was considered as the day zero of our protocol. Before day zero, the animals received a standard diet. During the entire protocol after day zero, they received a phytoestrogen free diet. At day 40 (at approximately 14 weeks of age), the animals were submitted to a bilateral ovariectomy (OVX) or SHAM surgery (referred here as gonadal-intact animals). The experimental groups (n = 10/group) were WKY-SHAM, WKY-OVX, SHR-SHAM and SHR-OVX. Five days before either surgery (at day 35) or euthanasia (at day 85), blood pressure, body weight and estrous cycle phase were evaluated. At day 90 (50 days after surgery), all animals were euthanised for sample collection. (B) Rat body weight variation between animals post-OVX surgery (at day 85) and pre-OVX (at day 35). (C) Ratio between uterus weight and body weight was determined as an index of OVX surgery efficiency.

2.3. Surgical procedure

Surgery was conducted under inhaled general anaesthesia with isoflurane vaporized in oxygen (5 % for induction, 2 % for maintenance) and the animal’s body temperature was maintained at 37 °C throughout the procedures. The ovariectomized group of rats had both ovaries removed, while SHAM operated group were submitted to the identical surgical protocol but does not have their ovaries removed. After anesthetic induction, animals were positioned in lateral decubitus, were trichotomized in both the right and left flanks and an incision of approximately 0.5 cm caudally to the last rib was carried out to reach the abdominal cavity. After the muscle and subcutaneous tissue dissection, the ovary was exposed and two ligation sutures were positioned between the Fallopian tube (close to the uterine horn), vessels, and periovarian adipose tissue. The organ was then removed after a single incision between the two suture ligations. The same procedure was repeated contralaterally and muscle and skin layers were then sutured using polyglactin 910 (Vicryl®) 4-0 and mononaylon 5-0, respectively. Analgesic support was provided after the surgery by a single dipyrone dose (500 mg/kg, via i.m.) and over the first three days post-surgery with tramadol (5 mg/kg, via i.p.) twice a day, every 12 h. After 50 days (at day 90, Fig. 1A) of ovariectomy, animals were deeply anesthetized with isoflurane for blood and organ collection. Euthanasia occurred by exsanguination until cardiorespiratory arrest.

2.4. Biological sample preparation

Blood (approximately 10 mL) was obtained by cardiac puncture in 1:10 (v/v) 3.8 % trisodium citrate. Then platelet-rich plasma (PRP) was prepared immediately by centrifugation at 200 x g in three cycles of 5 min each. The PRP was used for all platelet aggregation experiments at the same day of its collection. Platelet-poor plasma (PPP) was obtained by blood centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 10 min. PPP was aliquoted and stored at −20 °C until use in the coagulation assays, cell treatments, and nucleotidase activity determinations. Abdominal and the descending thoracic aorta and uterus were also collected. Abdominal and thoracic aorta were washed in cold phosphate-buffered saline and kept on ice until use. The thoracic aorta was immediately sectioned in two-millimetre rings and processed as previously described (Ait Aissa et al., 2015) for the aortic ring procoagulant profile assays (see details below). The abdominal aorta was immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C for tissue extract processing and western-blot experiments. The fresh (wet) uterus was weighed in an analytical scale, frozen and kept at −80 °C.

2.5. Cardiovascular parameters

On the 35th and 85th day of the protocol (Fig. 1A), heart rate, systolic and diastolic blood pressure were measured in conscious rats by the tail-cuff method (Insight, Ribeirao Preto, SP, Brazil). The animals were properly adapted to the equipment and the measurement procedure before the protocol started. Three consecutive readings of blood pressure and heart rate were recorded per animal.

2.6. Platelet aggregation

Platelet aggregation agonists ADP (10 μM) or collagen (2.5 μg/mL) were incubated for 5 min at 37 °C in 96-well flat-bottomed plates containing Tyrode-albumin buffer, pH 7.4. Aggregation response was then triggered by the addition of PRP suspension (3-4 x 105 cells/μL) and changes in turbidity were monitored at 650 nm in intervals of 11 s for 30 min using a microplate reader (SpectraMAX 190, Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). The decrease in turbidity over time was measured in absorbance units and results expressed as area under the aggregation curves, as previously described (Berger et al., 2010).

2.7. Nucleotide hydrolysis

The hydrolysis of extracellular nucleotides was determined in serum and platelets by an enzymatic assay as already described (Naasani et al., 2017). E-NTPDase (ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase) and ecto-5’-nucleotidase activities were measured through the malachite green method using ATP, ADP, and AMP as substrates and KH2PO4 as Pi standard. Nucleotide spontaneous hydrolysis was monitored during incubation in absence of serum or platelet extracts. All samples were run in triplicate and enzyme specific activity was expressed as nmol Pi released per min per mg of protein. Phosphodiesterase activity (E-NPP, nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase) was assessed by using the synthetic chromogenic substrate thymidine 5’-monophosphate p-nitrophenyl ester, p-Nph-5’-TMP (Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) at a final concentration of 0.5 mM. The kinetics of p-nitrophenol release was monitored at 405 nm during a total time of 30 min with 14 s intervals between reads. Enzyme activity was expressed as mOD of p-nitrophenol released per min per mg of protein.

2.8. Blood coagulation

The following coagulation parameters were measured in citrated plasma: activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT), prothrombin time (PT), thrombin time (TT), and fibrinogen levels (FBG). These parameters were determined using commercially available kits following the general manufacturer’s instructions (Sullab Diagnosticos, Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil).

2.9. Aortic ring assays

To measure the procoagulant profile acquired by normotensive and hypertensive ovariectomized rat aorta, we design an aortic ring assay based on the procedure previously described by Ait Aissa et al., 2015, with some modifications. Thoracic aortic rings (approximately 2 mm) were resuspended in Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate buffer containing 2 g/L bovine serum albumin and incubated at 37 °C for 5 min. Then, a mixture of activated factor VII (FVIIa) (2 nM), factor X (FX) (1.2 nM), activated factor V (FVa) (2.5 nM), and prothrombin (10 nM) was added and thrombin generation monitored by changes in absorbance at 405 nm after the addition of 0.2 mM S2238 substrate (H-D-Phe-Pip-Arg-p-nitroanilide). Similarly, activated factor X (FXa) generation was also measured in the presence of aortic rings by adding a mixture containing FVIIa (2 nM), FX (8 nM) and 0.2 mM S2222 substrate (Bz-Ile-Glu-Gly-Arg-p-nitroanilide). For the plasma kallikrein generation assay, the aortic rings were incubated in Krebs-Ringer with human plasma deficient in prothrombin (diluted 1:5) containing 100 nM corn trypsin inhibitor. Kallikrein formation was then followed at 405 nm by adding S2302 substrate (H-D-Pro-Phe-Arg-p-nitroanilide). In this case, both prothrombin deficient plasma and corn trypsin inhibitor were used to avoid thrombin and activated factor XII (FXIIa) interference, respectively. Kinetic readings were taken over 40 min (14 s intervals) for all the aortic ring assays using 96-well plates in a final volume of 150 μL.

2.10. Nitrite/nitrate measurements

Total nitrate and nitrite levels (NOx−) were determined as an indication of NO production. The measurements were performed in total plasma and aorta extracts according to the Griess method (Miranda et al., 2001).

2.11. Cell culture experiments

Vascular smooth muscle cells (VMSC) (A7r5 cell line, ATCC® CRL-1444), derived from rat thoracic aorta, were cultured in DMEM (high glucose) containing 10 % fetal bovine serum (FBS), 50 U/mL penicillin and 100 μg/mL streptomycin following the standards for cell culture maintenance. VMSCs were used to investigate if the plasma-derived from normotensive and hypertensive OVX rats could induce a procoagulant profile on cell surface. For this purpose, a similar experimental design as described by Berger et al., 2019 was followed. Confluent VSMC monolayers seeded in 96-well plates were treated for 1 h with 5, 10 or 30 % of plasma obtained from OVX and SHAM-operated animals diluted in DMEM without FBS. Then, the medium was removed and cells were washed twice in PBS. The procoagulant profile triggered on VSMC surface was determined by the aPTT assay after addition (50 μL) of a normal rat plasma pool collected from healthy animals. To verify if the procoagulant profile induced on VSMCs was time-dependent, VSMC monolayers were treated with 10 % diluted plasma and cells were washed and processed for aPTT assay after different time-points of incubation (30 min, 1, 2, 4, and 24 h), using the same procedure described before. In another set of experiments, VSMCs were pre-treated overnight (in the presence of 1 % FBS) with PBS or 0.1 μM PDTC to block the NF-κB pathway. Then, it was added 10 % diluted plasma from OVX and SHAM animals in absence of FBS. Incubation was maintained for an additional 2 h and after a washing step, aPTT was measured as above using normal plasma pool. In all experimental settings, clot formation kinetics was monitored (650 nm) at a time interval of 10 s for a total time of 20 min on a SpectraMAX 190 microplate reader (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA).

2.12. Western blotting

Protein expression of different biomarkers related to thrombosis was evaluated in tissue (aorta) and cell (platelets and VSMCs) extracts by immunoblot. Following standard procedures, proteins (30-50 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions, transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, incubated with primary and secondary-horseradish peroxidase conjugated antibodies, and revealed using the colorimetric kit Opti-4CN (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). Protein expression levels were normalized against β-actin and quantified using Image J software (available at https://imagej.nih.gov/ij/). The following antibodies and dilutions were used: Cyclooxygenase 2 (COX-2) – 1:500 (D5H5 #12282 – Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA); inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) – 1:200 (M-19 #sc-650 Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA); tissue factor (TF) – 1:500 (I-20 #sc-23596 – Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA); kallikrein-1 (KLK1) – 1:500 (13G11 #19901 – QED Bioscience, San Diego, CA, USA); factor X (FX) – 1:500 (C-20 #sc-16341 – Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA); factor II (FII) – 1:500 (D-15 #sc-23355 – Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA); protease activated receptor – 1 (PAR1) – 1:500 (ATAP2 #sc-13503 – Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA); plasminogen activator inhibitor – 1 (PAI-1) – 1:1000 (M-20 #sc-6644 – Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA); urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) – 1:500 (#CSB-PA14319A0Rb, Cusabio Biotech Co., Wuhan, China); and β-actin – 1:1000 (#A-1978, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Loius, MO, USA).

2.13. Data analysis

The data are presented as means ± SE, and significant differences were analysed by one-way ANOVA followed by an unpaired t-test with Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. Cardiovascular parameters were analysed by the method of Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) followed by Bonferroni’s test. Data from body and uterus weight were analysed using Kruskal-Wallis followed by Dunn’s test. P-values of 0.05 were significant considered to be significant. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) or SPSS 20.0 software.

3. Results

In this work we designed an experimental model of post-menopausal hypertension in ovariectomized rats to better understand how thrombotic mechanisms in the aorta are impacted by estrogen reduction. For this purpose, we subjected both WKY and SHR female rats feeding on phytoestrogen free diet to a bilateral ovariectomy (OVX) surgery (Fig.1A). Rat body weight increased in groups that had their ovaries removed (Fig. 1B). The OVX surgery efficiency was confirmed by uterine atrophy, as demonstrated by a significant reduction in the uterus weight in ovariectomized animals (Fig 1C). The 17-β estradiol levels also reduced in post-OVX rats compared to its baseline values pre-surgery (Table S1). Normotensive WKY animals had lower systolic (SBP) and diastolic (DBP) blood pressure levels compared to SHR at the baseline pre-OVX measurements (Table 1). The difference between these parameters increased significantly 50 days post-OVX surgery. Estrogen depletion led to hypertension in WKY animals, since SBP increased from 132 ± 4.7 to 169 ± 3 mmHg, while in SHR it led to an exacerbated hypertensive response with SBP increasing from 159 ± 3.5 to 176 ± 2.5 mmHg (Table 1).

Table 1.

Cardiovascular parameters in WKY and SHR ovariectomized rats.

| Parameter | Groups | Pre-OVX Baseline (Day 35) |

Post-OVX Day 85 |

p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR (beats/min) | WKY-SHAM | 331 ± 15 | (a) | 346 ± 8.6 | (a) | 1.000 |

| WKY-OVX | 332 ± 8.6 | (a) | 363 ± 7.8 | (ab) | 1.000 | |

| SHR-SHAM | 376 ± 14 | (a) | 331 ± 8 | (a) | 0.001 | |

| SHR-OVX | 358 ± 7 | (a) | 385 ± 8 | (b) | 0.091 | |

| SBP (mmHg) | WKY-SHAM | 129 ± 3 | (a) | 126 ± 0.8 | (a) | 1.000 |

| WKY-OVX | 132 ± 4.7 | (a) | 169 ± 3 | (b) | <0.001 | |

| SHR-SHAM | 152 ± 4 | (b) | 143 ± 2.8 | (c) | 0.259 | |

| SHR-OVX | 159 ± 3.5 | (b) | 176 ± 2.5 | (b) | <0.001 | |

| DBP (mmHg) | WKY-SHAM | 82 ± 2.7 | (a) | 80 ± 2.4 | (a) | 1.000 |

| WKY-OVX | 81 ± 2 | (a) | 102 ± 1.7 | (b) | <0.001 | |

| SHR-SHAM | 95 ± 3 | (b) | 90 ± 3.2 | (ac) | 1.000 | |

| SHR-OVX | 100 ± 3.7 | (b) | 107 ± 3 | (b) | 0.737 | |

Spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) and Wistar Kyoto rats (WKY) were ovariectomized (OVX)- or SHAM-operated (n = 10/group). Cardiovascular parameters such as, heart rate (HR), systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) were measured before (at the baseline, pre-OVX) and after surgery (post-OVX). Details about the experimental design can be found in Fig. 1A. The results are presented as mean ± SE. For data analysis the method of Generalized Estimating Equations (GEE) followed by Bonferroni’s test was used. The p-value column indicates statistical differences between time (pre-OVX versus post-OVX). The letters indicate statistical differences between experimental groups. Same letter means no difference (p>0.05), while different letters means that there is statistical difference between groups (p<0.05). In all cases, p<0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The first evidence that ovariectomized animals evolved to a prothrombotic state was obtained from ex-vivo platelet aggregation assays (Fig. 2). Platelets from both WKY and SHR rats showed an exacerbated aggregatory response to ADP (Fig. 2A-C) and collagen (Fig. 2D-F) after OVX. Hypertensive animals from SHR group did not have a higher aggregatory response compared to WKY-SHAM group, but this effect slightly increased after OVX surgery compared to WKY-OVX group (Fig. 2B-C and E-F). To investigate the mechanisms behind the platelet pro-aggregatory response, our primary hypothesis was the nitric oxide system. Interestingly, nitrate/nitrite levels in plasma and aorta and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) expression in aorta did not change significantly between groups, despite a little increase observed in nitrite/nitrate levels in plasma of spontaneously hypertensive ovariectomized rats (SHR-OVX) (Fig. 3A-C). Alternatively, when the aorta cyclooxygenase-2 expression was analysed, a reduction around of 50 % was observed both in WKY and SHR groups after OVX surgery (Fig. 3C). The second hypothesis was to investigate nucleotide metabolism involved in platelet aggregation, since ADP is one of the most important aggregation agonist and adenosine is a physiological inhibitor that controls this process. As shown in Figure 4, E-NTPDase (ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase) and ecto-5’-nucleotidase activities reduced almost at the same extent in serum and platelets of normotensive (WKY) or hypertensive (SHR) animals after ovarian removal. The presence of basal hypertension increased ADP hydrolysis on platelets, but estrogen depletion downregulated this parameter (Fig. 4F). Looking to phosphodiesterase activity (E-NPP), SHR had the highest activity levels compared to normotensive rats in both serum and platelets. After OVX, an opposite effect was observed, E-NPP increased in serum from WKY group and decreased in platelets from spontaneously hypertensive animals (Fig. 4D and H).

Figure 2. Platelet aggregation function in estrogen-depleted normo and hypertensive rats.

A bilateral ovariectomy (OVX) or SHAM surgical procedure was performed in 14-week-old female spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) and normotensive Wistar Kyoto (WKY) rats. After 50 days, animals were euthanized and blood was collected for ex-vivo platelet aggregation functional tests. (A) ADP (10 μM)-induced platelet aggregation in platelet rich plasma (PRP). (B) Representative profile of ADP-induced aggregation curves for normotensive WKY rats. (C) Representative profile of ADP-induced aggregation curves for SHR rats. (D) Collagen (3 μg/mL)-induced platelet aggregation in PRP. (E) Representative profile of collagen-induced aggregation curves for normotensive WKY rats. (F) Representative profile of collagen-induced aggregation curves for SHR rats. Data are presented as mean ± SE and (*) represents a statistically significant difference between indicated groups (one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s-post hoc test).

Figure 3. Nitrate/nitrite, nitric oxide synthase and cyclooxygenase 2 levels in normo and hypertensive ovariectomized rats.

A bilateral ovariectomy (OVX) or SHAM surgical procedure was performed in 14-week-old female spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) and normotensive Wistar Kyoto (WKY) rats. After 50 days, animals were euthanized for plasma and aorta collection. (A) Plasma and (B) Aorta nitrite/nitrate (NO−x) levels as determined by the Griess method. (C) Aorta protein expression levels of inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and cyclooxygenase 2 (COX2) as determined by western-blot (upper panel showing the representative blots from three independent experiments and lower panel showing its respective quantitative analysis normalized by the β-actin expression). Data are presented as mean ± SE and (*) represents statistically significant difference between indicated groups (one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s-post hoc test).

Figure 4. Hydrolysis of the main nucleotides involved in platelet aggregation in estrogen-depleted normo and hypertensive rats.

A bilateral ovariectomy (OVX) or SHAM surgical procedure was performed in 14-week-old female spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) and normotensive Wistar Kyoto (WKY) rats. After 50 days, animals were euthanized and serum and platelets were collected to determine the enzymatic activity of ectonucleotidases involved in nucleotide metabolism that are relevant for platelet aggregation function. The activities of E-NTPDases (ectonucleoside triphosphate diphosphohydrolase), ecto-5’-nucleotidase and E-NPP (nucleotide pyrophosphatase/phosphodiesterase) were estimated in serum and platelets by the hydrolysis rate of AMP (A and E), ADP (B and F), ATP (C and G) and 5’-TMP (D and H). Data are presented as mean± SE and (*) represents statistically significant difference between indicated groups (one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s-post hoc test).

Like platelet aggregation, plasma coagulation parameters also changed significantly after ovariectomy (Fig. 5). Extrinsic, intrinsic, and common pathways of blood coagulation were evaluated in citrated plasma by the classical tests such as aPTT, PT, TT, and fibrinogen levels measurements. In general, plasma from OVX animals coagulated faster than those from SHAM-operated animals independent of the basal hypertension levels pre-surgery. This event was particularly evident in intrinsic pathway measurements (aPTT was around of 25 s in the SHAM group, while the coagulation time was 15 s in OVX) but was also observed in extrinsic and common pathway measurements, such as in PT and TT, respectively (Fig. 5A-C and E). In agreement with these alterations, fibrinogen levels drop down in estrogen depleted groups, being more evident in WKY-OVX group (Fig. 5F).

Figure 5. Blood coagulation parameters in estrogen-depleted normo and hypertensive rats.

Citrated blood was collected through intracardiac puncture from ovariectomized (OVX) and SHAM-operated spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) and normotensive Wistar Kyoto (WKY) rats. The following coagulation parameters were determined in plasma: (A) activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT); (B) kinetics of WKY rats aPTT; (C) kinetics of SHR rats aPTT; (D) prothrombin time (PT); (E) thrombin time (TT) and (F) fibrinogen levels. Data are presented as mean ± SE and (*) represents statistically significant difference between indicated groups (one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s-post hoc test).

Aiming to understand how the aorta can contribute to the generation and maintenance of prothrombotic state, we designed some experiments to measure the complex assembly and activity of the main procoagulant enzymes on the aortic ring surface. As shown in Figure 6, the aortic rings can support the complex assembly responsible for kallikrein, FXa and thrombin generation. However, the procoagulant enzyme generation was higher in aortic rings from estrogen deficient rats (Fig. 6A-C). Interestingly, hypertension exacerbated thrombin generation in aortic rings from SHR-OVX group compared to those from WKY-OVX group, which were originally normotensive pre-ovarian removal surgery (Fig. 6C). Corroborating these findings, tissue factor expression (the main molecule known as an initiator of extrinsic coagulation pathway), increased in both the aorta (Fig. 7A) and the platelet (Fig. 7B) surface from ovariectomized animals. In a similar way, OVX increased the aortic expression of other prothrombotic (FII and FX) (Fig. 8A and C) and fibrinolytic (PAI-1 and uPA) (Fig. 8 B and D) proteins, being uPA markedly up-regulated by the presence of basal hypertension, such as in SHR-OVX animals (Fig. 8D). As a consequence of procoagulant enzyme activation, the protease activated receptor 1 (PAR-1), the main receptor cleaved by thrombin and FXa-induced intracellular signalling, also appeared upregulated in WKY-OVX and SHR-OVX aorta (Fig. 8C).

Figure 6. Procoagulant phenotype of aortic rings derived from normo and hypertensive ovariectomized rats.

The descending thoracic aorta was collected from ovariectomized (OVX) and SHAM-operated spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) and normotensive Wistar Kyoto (WKY) rats. Then, two mm ring segments were prepared to measure its potential increasing rate of kallikrein, factor Xa (FXa) and thrombin generation. (A) Kallikrein generation was determined by incubating the aortic rings with diluted prothrombin-deficient human plasma and adding the specific synthetic substrate S2302 to measured formed kallikrein. (B) FXa generation was determined by incubating the aortic rings with purified human FX, FVIIa and calcium ions and adding the specific synthetic substrate S2222 to measured formed FXa activity. (C) Thrombin generation was determined by incubating the aortic rings in the presence of purified human prothrombin, FVa, FVIIa, FX and calcium ions and adding the specific synthetic substrate S2238 to measured formed thrombin. Data are presented as mean ± SE and (*) represents statistically significant difference between indicated groups (one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s-post hoc test).

Figure 7. Tissue factor (TF) protein expression in aorta and platelets from normo and hypertensive ovariectomized rats.

Abdominal aorta and platelets were collected from ovariectomized (OVX) and SHAM-operated spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) and normotensive Wistar Kyoto (WKY) rats. Aorta (A) and platelet (B) extracts were prepared, and TF protein expression were analysed by western blot. The upper panel shows representative images from three independent analyses, while the lower panel presents the quantitative data normalized by the β-actin expression. Data are presented as mean ± SE and (*) represents statistically significant difference between indicated groups (one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s-post hoc test).

Figure 8. Prothrombotic and fibrinolytic molecular markers in aorta from estrogen-depleted normo and hypertensive rats.

Abdominal aorta was collected from ovariectomized (OVX) and SHAM-operated spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) and normotensive Wistar Kyoto (WKY) rats. The tissue extracts were prepared and protein expression of prothrombotic markers – kallikrein (KLK1), factor X (FX), factor II (FII) and protease activated receptor – 1 (PAR-1) - (A and C) and fibrinolytic markers – plasminogen activator inhibitor – 1 (PAI-1) and urokinase plasminogen activator (uPA) - (B and D) were determined by western blot. The left panel shows representative images from three independent analyses, while the right panel presents the quantitative data normalized by the β-actin expression. Data are presented as mean ± SE and the symbols (* and #) represents statistically significant difference between indicated groups (one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s-post hoc test).

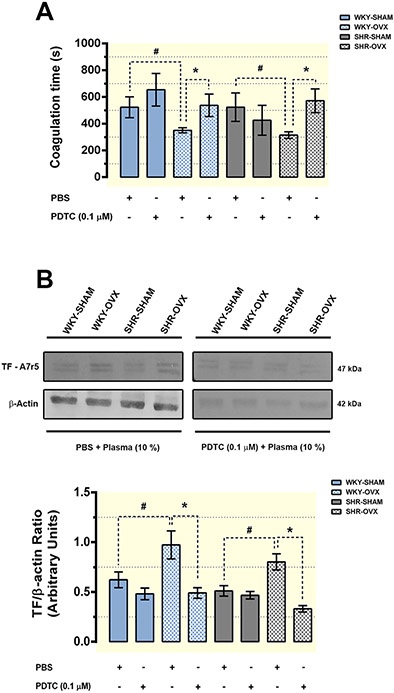

Next, we investigated if the plasma-derived from estrogen deficient animals could also activate and induce a prothrombotic profile in naive VSMCs in vitro. For this purpose, we chose a VSMC cell line (A7r5) derived from rat thoracic aorta, which was treated with increasing concentrations of plasma from normotensive and hypertensive OVX rats. As shown in Figure 9, normal healthy plasma coagulated faster on VSMC surface pre-treated with OVX-derived plasma from both normotensive (WKY-OVX) and hypertensive (SHR-OVX) animals. The procoagulant profile triggered by OVX plasma was dose-dependent (Fig. 9A) and more pronounced in VSMC treated up to 2 h, being similar to the control levels in cells treated by 24 h (Fig. 9B). We also observed that OVX-derived plasma significantly increased the tissue factor expression on VSMC mainly between 30 min and 2 h post-treatment (Fig. 9C and D). In the last experiment (Fig. 10), we hypothesized that the upregulation of the tissue factor and the consequent procoagulant profile triggered on VSMC could be linked to an inflammatory intracellular signalling. To properly test this hypothesis, prior to the addition of OVX-derived plasma, cells were treated with PDTC, a NF-κB pathway inhibitor. As shown in Figure 10A, blocking the NF-κB mediated pathway reduced significantly the procoagulant effect triggered by WKY-OVX and SHR-OVX plasma on VSMC surface. The reduction in VSMC-induced procoagulant activity was accompanied by a down-regulation in tissue factor expression on cells previously treated with PDTC (Fig. 10B).

Figure 9. Plasma-derived from normo and hypertensive ovariectomized rats induced a procoagulant phenotype in vascular smooth muscle cells in culture.

Plasma obtained from ovariectomized (OVX) and SHAM-operated spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) and normotensive Wistar Kyoto (WKY) rats was used to treat a cell line (A7r5) of vascular smooth muscle cells derived from rat thoracic aorta. (A) A7r5 cells were treated with different concentrations of SHR or WKY-derived plasma for 1 h, then cells were washed, and coagulation time was determined through the aPTT assay by the addition of a rat plasma pool collected from healthy animals. (B) A7r5 cells were treated with diluted plasma (10 %) from SHR or WKY animals, at different time-points cells were washed and aPTT was determined as described above. (C) A7r5 cells treated with 10 % plasma from SHR or WKY animals were collected in each time-point, and tissue factor (TF) protein expression was determined by western blot. The panel shows representative images from three independent analyses. (D) Data from TF blots in each time-point were quantified and normalized by the β-actin expression. All data showed on graphs are mean ± SE analysed by one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s-post hoc test. Coagulation data are presented as a ratio between coagulation time from ovariectomized versus SHAM-operated animals. The dotted line on graphs A and B indicates the normal coagulation pattern of A7r5 cells incubated with rat plasma pool collected from healthy animals. The symbols (*) and (#) in panels A and B indicate respectively the statistical difference of WKY and SHR versus the normal coagulation time from cells treated with plasma pool of healthy animals. The same symbols (* and #) in panel D indicate respectively the statistical difference between KY SHAM versus KY OVX and SHR SHAM versus SHR OVX groups.

Figure 10. The procoagulant phenotype induced by plasma derived from normo and hypertensive ovariectomized rats requires NF-κB pathway.

Vascular smooth muscle cells (A7r5) were pre-treated overnight with PBS or 0.1 μM PDTC to block the NF-κB pathway. Then the cells were incubated for 2 h with 10 % plasma obtained from ovariectomized (OVX) and SHAM-operated spontaneously hypertensive (SHR) and normotensive Wistar Kyoto (WKY) rats. After a washing step, coagulation time was determined through the aPTT assay by the addition of a rat plasma pool obtained from healthy animals (A). Similarly, in another set of experiments vascular cells were treated as above and collected for tissue factor (TF) protein expression analysis by western blot (B). The upper panel in B shows representative images from three independent experiments, while the lower panel presents the quantitative data normalized by the β-actin expression. All data are presented as mean ± SE and symbols (* and #) represents statistically significant difference between indicated groups (one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s-post hoc test).

4. Discussion

In this study, we developed an experimental model of postmenopausal hypertension induced by bilateral ovariectomy in 14-week-old WKY and SHR female rats. We found that acute endogenous estrogen deprivation after ovariectomy promptly increases the blood pressure independent of a previous basal hypertensive condition, leading to a systemic vascular prothrombotic state. The mechanism behind this finding involved a platelet hyperreactivity, which was directly related to the downregulation of the nucleotide degradation system and the upregulation of tissue factor in both platelets and aorta. The aorta participates in the mechanism by supporting procoagulant enzyme generation, including thrombin, and this event is significantly exacerbated in hypertensive aorta. Interestingly, we found that plasma derived from ovariectomized animals can trigger a prothrombotic profile in cultured vascular cells by increasing tissue factor expression through NF-κB-dependent pathway.

Since hypertension is an important risk factor for vascular thromboembolic events in the postmenopausal period, we decided to use SHR animals, which are a known model of preestablished and sustained hypertension. Previous studies have reported that feeding ovariectomized SHR a high-salt diet will further exacerbate the level of hypertension, which was not observed in normotensive animals (Fang et al., 2001; Harrison-Bernard et al., 2003; Peng et al., 2003). In contrast, Ito et al., 2006 measured blood pressure by radiotelemetry and detected a significant SBP increase in both ovariectomized normotensive (WKY) and SHR feeding a phytoestrogen free diet with standard levels of NaCl. Another important point to be considered in this case is the animal age at the moment of ovary removal surgery. Rats ovariectomized at a young age only develop hypertension when fed a high-salt diet (Fang et al., 2001; Harrison-Bernard et al., 2003), whereas rats ovariectomized at ages from 12–14 weeks-old have increased arterial pressure feeding a phytoestrogen-devoid diet containing both standard or high-NaCl amounts (Ito et al., 2006; Peng et al., 2003). In this study, we ovariectomized 14-week-old animals previously feeding a phytoestrogen free diet with standard NaCl and we followed them for a longer period (50 days). In a similar way to that observed by Ito et al., 2006, we found that both normotensive WKY and SHR animals had increased SBP, DBP, and HR compared to the basal measurements before bilateral ovariectomy surgery. This indicates that it would be a good model to study thromboembolic alteration during postmenopausal hypertension. Of course, following the animals for longer periods of time after ovariectomy would be ideal mainly to mimic the vascular dysfunction caused by senescence in elder menopausal women. Therefore, the endpoint of the protocol may be a limitation to be considered in our study. Regarding the mechanism involved in estrogen depletion-induced hypertension, Ahmad et al., 2018 found an up-regulation of chymase-derived angiotensin II (Ang II) in cardiomyocytes isolated from ovariectomized SHR. Once Ang II has a prothrombotic effect causing platelet hyperreactivity (Fang et al., 2013; Mogielnicki et al., 2005), it is possible that chymase-derived Ang II has also a role in the prothrombotic events observed here. However, this deserves further exploration.

The first evidence of a systemic prothrombotic state was the procoagulant activity observed in plasma coagulation tests and platelet hyperreactivity. Platelets from ovariectomized animals had an enhanced response when stimulated with ADP and collagen. Accordingly, platelets from ovariectomized Dahl-salt-sensitive rats also showed an exacerbated aggregatory response to thrombin by a mechanism dependent of intracellular calcium and PKC activation (Sasaki et al., 2000). Here, we found that other mechanisms may be involved. Nitrite/nitrate levels in plasma and iNOS expression in aorta remained unchanged, while COX-2 decreased in aorta. Both nitric oxide and COX-2 are important platelet regulators since they cause vasodilation and reduce the aggregatory response through cGMP and PGI2 generation, respectively (Shah, 2005). Thus, COX-2 downregulation can contribute to a prothrombotic state by maintaining a vasoconstrictive response and platelet hyperreactivity. Another mechanism we found was related to the inhibition of nucleotide degradation system in estrogen depleted groups. The same nucleotides used in energy metabolism also participate as platelet aggregation regulators. ATP and ADP are stored in platelet dense granules and are secreted during platelet activation. Extracellular ATP is rapidly metabolized in a cascade hydrolysis into ADP, AMP and finally adenosine by the ecto-enzymes E-NTPDase (CD39), ecto-5’-nucleotidase (CD73) and E-NPP (Koupenova and Ravid, 2018). Secreted ATP and ADP, as well as ADP deriving from ATP degradation, activate P2Y1, P2Y12, and P2X1 receptors. Through the P2Y12 receptor, ADP strongly modulates the growth and stability of thrombus by potentiating platelet dense granule release, platelet aggregation and procoagulant activity (Ballerini et al., 2018). On the other hand, adenosine through the P1 receptors acts as a counterregulatory molecule increasing cAMP intracellular levels and inhibiting platelet aggregation (Koupenova and Ravid, 2018). Thus, nucleotide hydrolysis can control the balance between pro and anti-aggregatory profiles. Interestingly, ATP, ADP, and AMP hydrolysis decrease at similar rates in serum and platelets of normotensive and hypertensive ovariectomized animals. This suggests that estrogen deprivation changes nucleotide metabolism shifting the balance, favouring ADP/ATP accumulation and, thus, contributing to platelet hyperreactivity.

Platelets, endothelial cells and VSMC participate in the initial and amplification phases of clot formation. They offer a proper surface of negatively charged phospholipids for coagulation factor complex assembly (Esmon and Esmon, 2011). Exposure of phosphatidylserine on the outer membrane of platelets and vascular cells regulated by flip-flop mechanism is thought to account for the procoagulant profile of these cells. A previous report showed that aortic rings and VSMC from SHR animals had increased amounts of negatively charged phospholipid procoagulant activity, which was correlated to a greater thrombin generation at the surface of SHR-derived aortic rings compared to WKY control rings (Ait Aissa et al., 2015). The authors found that hypertension-induced intracellular calcium elevation in SHR cells promoted the flip-flop process causing exposure of negatively charged phospholipids (Ait Aissa et al., 2015). While changes in membrane phospholipid rearrangement allow coagulation factor binding, the protein effectively responsible for triggering FXa and thrombin generation on vascular cell surface is the tissue factor (TF) (Grover and Mackman, 2018). In fact, it has been shown that SHR has higher levels of TF associated with VSMC, but the present work is the first to demonstrate that estrogen depletion exacerbates TF expression in platelets and aorta. TF was upregulated to a similar extent in both normotensive and hypertensive ovariectomized animals. TF is the major cellular initiator of blood coagulation (Pawlinski et al., 2004). It is a type I transmembrane glycoprotein that orchestrates the initiating cascade by binding to FVII and facilitating its activation to VIIa. FVIIa that is not bound to TF has little activity (Riewald and Ruf, 2002). Once activated, the complex TF-VIIa binds to its substrate FX, generating FXa. The TF-VIIa-Xa complex efficiently cleaves prothrombin (FII) producing the main procoagulant enzyme, thrombin. TF-VIIa-Xa and thrombin also intimately links coagulation to inflammation, since these proteases are PAR-1 and PAR-2 activators triggering proinflammatory cytokines through NF-κB pathway (Riewald and Ruf, 2002). Consistent with TF up-regulation in the aorta, we observed that aortic rings derived from ovariectomized rats supported an increased generation activity of kallikrein, FXa and thrombin on their surface. In this case, ovariectomized SHR presented a greater thrombin generation capacity compared to equivalent rings from normotensive rats, suggesting that estrogen depletion shifted vascular hemostatic balance toward a prothrombotic phenotype.

It is known that high blood pressure can induce microlesions on the vascular wall (Mogielnicki et al., 2005; Wassmann et al., 2001). This fact associated with higher radial hydraulic conductance in hypertensive vessels can facilitate blood clotting factors not only to bind directly to exposed endothelial cells, but also effectively crossing through the lumen reaching medial VSMCs (Lacolley et al., 2012). Thus, we hypothesized that procoagulant markers could be detected directly on vascular tissue extracts. In fact, aorta derived from estrogen depleted rats had increased levels of procoagulant (FX and FII) and fibrinolytic (PAI-1 and uPA) protein biomarkers, which corroborates with higher TF expression and procoagulant enzyme generation on aortic rings. To further explore VSMCs contribution to the hypercoagulable state, we designed some additional experiments in which the A7r5 VSMC cell line was treated with plasma-derived from ovariectomized animals. The rationale behind these experiments was based on previous observations showing that the capacity of activated platelets and even VSMCs to secrete soluble TF-enriched microparticles that circulates free in the blood stream (Pawlinski et al., 2004). Then we further wondering if the plasma derived from hypercoagulable estrogen-depleted animals could also induce a procoagulant activity on naïve VSMCs. Interestingly, VSMCs treated with estrogen deficient plasma had TF expression induced in the first 2 h. In accordance, when normal plasma was added to these cells previously treated with estrogen deficient plasma, it coagulated faster compared to untreated cells. This suggests that estrogen deficient plasma from WKY and SHR activates and triggers a procoagulant profile on VSMC, independent of basal hypertension levels before ovariectomy. Additionally, we also observed that the mechanism behind these effects in VSMCs involves an inflammatory pathway mediated by NF-κB, since PDTC (a NF-κB blocker) significantly reduced TF expression and procoagulant activity on VSMC surface. As previously mentioned, thrombin and TF complex (TF-VIIa-Xa) generated during hypercoagulable states are linked to proinflammatory signalling through the activation of PAR-1 and PAR-2 receptors (Riewald and Ruf, 2002). For example, in endothelial cells thrombin participates in a positive feedback loop, activating PAR-1 and inducing TF expression up-regulation which in turn contributes to increases in FXa and thrombin formation (Minami et al., 2004). Once activated, PAR-1 regulates TF expression triggering IκBα proteolytic degradation and inducing nuclear translocation of NF-κB and c-Rel/p65 complexes (Pendurthi et al., 1997). Similarly, PAR-1 also regulates the expression of other proinflammatory molecules such as ICAM, VCAM and IL-6 (Grover and Mackman, 2018; Minami et al., 2004). Since PAR-1 is up-regulated in aorta from ovariectomized animals, it is reasonable to suppose that such mechanism strongly contributes to the prothrombotic profile described here in our model (an overview for the mechanism is presented in Fig. 11).

Figure 11. Overview of the prothrombotic mechanisms in an experimental model of menopausal hypertension.

Bilateral ovariectomy leads to an increase in blood pressure. This event is associated with platelet hyperreactivity and increased tissue factor expression in platelets, aorta and vascular cells. The aorta and vascular cells of hypertensive ovariectomized animals have a greater capacity to generate procoagulant enzymes such as thrombin and factor Xa, which are formed on the cell surface by binding to tissue factor. Thrombin and factor Xa are the main activators of PAR-type receptors. These receptors regulate, through NF-kB, the expression of the tissue factor itself, which is found in endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells and platelets. The entire process appears to be part of a positive feedback mechanism that maintain a prothrombotic baseline state. Abbreviations: TF - tissue factor; FVIIa - factor VIIa, FXa - factor Xa, THR - thrombin, PLT - platelets; EC - endothelial cell; VSMC - vascular smooth muscle cell; PAR - protease-activated receptor; NF-kB - nuclear factor kappa B.

5. Conclusions

The results of this study aid our understanding of the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying the highest risk of prothrombotic events and its association with hypertension in postmenopausal women. We found that surgically induced estrogen deprivation in rats leads to a vascular prothrombotic state associated with a decrease in the nucleotide metabolizing system, platelet hyperreactivity and tissue factor expression up-regulation in both aorta and platelets. Aorta and vascular cells are important players being able to support procoagulant enzyme generation by a mechanism that was significantly exacerbated in hypertensive aorta. Interestingly, plasma derived from hypercoagulable estrogen-depleted rats can also trigger a prothrombotic profile in cultured naive vascular cells by increasing tissue factor expression through NF-κB-dependent pathway (Fig. 11). Thus, our data suggest that targeting tissue factor mediated events could be a therapeutic option for vascular thromboembolic complications in the postmenopausal period.

Supplementary Material

Table S1. 17-β Estradiol levels in WKY and SHR ovariectomized rats.

Highlights.

Ovariectomy leads to a vascular prothrombotic state independent of hypertension.

Estrogen depletion is associated with platelet hyperreactivity.

Hypertension exacerbates procoagulant enzyme generation in aorta and vascular cells after ovariectomy.

Tissue factor dependent NF-kB pathway is up-regulated in aorta, vascular cells and platelets.

Targeting tissue factor is promising for thromboembolic complications during menopause.

6. Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding and fellowships from Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, Ministério da Ciência e Tecnologia, Brazil (Chamada Universal MCTI/CNPq N° 01/2016, Grant 402523/2016-4 and Chamada Universal MCTI/CNPq N° 28/2018, Grant 422347/2018-3) and Fundo de Incentivo à Pesquisa e Eventos (FIPE-HCPA, GPPG Grants n° 19-0001; 19-0607; 21-0477) at Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre. LT and MB were also supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, grant Tick saliva and its importance for tick feeding and pathogen transmission (Z01 AI001337-01). Figure 1 and 11 were created using BioRender.com.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Credit author statement

SBP and PBT: Methodology, Investigation, Validation, Formal Analysis, Writing-Original draft; PZ, CPK and TNAG: Methodology, Investigation; EPP and LT: Resources, Funding acquisition; MB: Conceptualization, Investigation, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Writing-Review & Editing.

9. Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

8. References

- Ahmad S, Sun X, Lin M, Varagic J, Zapata-Sudo G, Ferrario CM, Groban L, Wang H, 2018. Blunting of estrogen modulation of cardiac cellular chymase/RAS activity and function in SHR. J. Cell. Physiol 233, 3330–3342. 10.1002/jcp.26179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ait Aissa K, Lagrange J, Mohamadi A, Louis H, Houppert B, Challande P, Wahl D, Lacolley P, Regnault V, 2015. Vascular smooth muscle cells are responsible for a prothrombotic phenotype of spontaneously hypertensive rat arteries. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 35, 930–937. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.305377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostis P, Paschou SA, Katsiki N, Krikidis D, Lambrinoudaki I, Goulis DG, 2018. Menopausal Hormone Therapy and Cardiovascular Risk: Where are we Now? Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol 17, 564–572. 10.2174/1570161116666180709095348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arikan E, Sen S, 2005. Endothelial damage and hemostatic markers in patients with uncomplicated mild-to-moderate hypertension and relationship with risk factors. Clin. Appl. Thromb. Hemost 11, 147–159. 10.1177/107602960501100204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballerini P, Dovizio M, Bruno A, Tacconelli S, Patrignani P, 2018. P2Y12 receptors in tumorigenesis and metastasis. Front. Pharmacol 9, 66. 10.3389/FPHAR.2018.00066/BIBTEX [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barp J, Sartório CL, Campos C, Llesuy SF, Araujo AS, Belló-Klein A, 2012. Influence of ovariectomy on cardiac oxidative stress in a renovascular hypertension model. Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol 90, 1229–1234. 10.1139/Y2012-078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger M, de Moraes JA, Beys-da-Silva WO, Santi L, Terraciano PB, Driemeier D, Cirne-Lima EO, Passos EP, Vieira MAR, Barja-Fidalgo TC, Guimarães JA, 2019. Renal and vascular effects of kallikrein inhibition in a model of Lonomia obliqua venom-induced acute kidney injury. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis 13. 10.1371/journal.pntd.0007197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger M, Reck J, Terra RMS, Pinto AFM, Termignoni C, Guimarães J. a, 2010. Lonomia obliqua caterpillar envenomation causes platelet hypoaggregation and blood incoagulability in rats. Toxicon 55, 33–44. 10.1016/j.toxicon.2009.06.033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celi A, Cianchetti S, Dellomo G, Pedrinelli R, 2010. Angiotensin II, tissue factor and the thrombotic paradox of hypertension. Expert Rev. Cardiovasc. Ther 8, 1723–1729. 10.1586/erc.10.161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias A, Rock W, Odetalla A, Ron G, Schwartz N, Saliba W, Elias M, 2019. Enhanced thrombin generation in patients with arterial hypertension. Thromb. Res 174, 121–128. 10.1016/j.thromres.2018.11.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esmon CT, Esmon NL, 2011. The link between vascular features and thrombosis. Annu. Rev. Physiol 73, 503–514. 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang C, Stavrou E, Schmaier AA, Grobe N, Morris M, Chen A, Nieman MT, Adams GN, LaRusch G, Zhou Y, Bilodeau ML, Mahdi F, Warnock M, Schmaier AH, 2013. Angiotensin 1-7 and Mas decrease thrombosis in Bdkrb2−/− mice by increasing NO and prostacyclin to reduce platelet spreading and glycoprotein VI activation. Blood 121, 3023–3032. 10.1182/blood-2012-09-459156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang Z, Carlson SH, Chen YF, Oparil S, Wyss JM, 2001. Estrogen depletion induces NaCl-sensitive hypertension in female spontaneously hypertensive rats. Am. J. Physiol. - Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol 281. 10.1152/ajpregu.2001.281.6.r1934 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover SP, Mackman N, 2018. Tissue Factor: An Essential Mediator of Hemostasis and Trigger of Thrombosis. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 38, 709–725. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309846 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison-Bernard LM, Schulman IH, Raij L, 2003. Postovariectomy Hypertension Is Linked to Increased Renal AT1 Receptor and Salt Sensitivity. Hypertension 42, 1157–1163. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000102180.13341.50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshi-Fukushima R, Nakamoto H, Imai H, Kanno Y, Ishida Y, Yamanouchi Y, Suzuki H, 2008. Estrogen and angiotensin II interactions determine cardio-renal damage in Dahl salt-sensitive rats with heart failure. Am. J. Nephrol 28, 413–423. 10.1159/000112806 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito K, Hirooka Y, Kimura Y, Sagara Y, Sunagawa K, 2006. Ovariectomy augments hypertension through rho-kinase activation in the brain stem in female spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 48, 651–657. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000238125.21656.9e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junker R, Heinrich J, Schulte H, Erren M, Assmann G, 1998. Hemostasis in normotensive and hypertensive men: results of the PROCAM study. The prospective cardiovascular Münster study. J. Hypertens 16, 918–922. 10.1097/00004872-199816070-00004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- knowlton AA, Lee AR, 2012. Estrogen and the cardiovascular system. Pharmacol. Ther 135, 54–70. 10.1016/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2012.03.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koupenova M, Ravid K, 2018. Biology of platelet purinergic receptors and implications for platelet heterogeneity. Front. Pharmacol 9, 37. 10.3389/FPHAR.2018.00037/BIBTEX [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacolley P, Regnault V, Nicoletti A, Li Z, Michel JB, 2012. The vascular smooth muscle cell in arterial pathology: a cell that can take on multiple roles. Cardiovasc. Res 95, 194–204. 10.1093/CVR/CVS135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minami T, Sugiyama A, Wu SQ, Abid R, Kodama T, Aird WC, 2004. Thrombin and Phenotypic Modulation of the Endothelium. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 24, 41–53. 10.1161/01.ATV.0000099880.09014.7D/FORMAT/EPUB [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miranda KM, Espey MG, Wink D a, 2001. A rapid, simple spectrophotometric method for simultaneous detection of nitrate and nitrite. Nitric Oxide 5, 62–71. 10.1006/niox.2000.0319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogielnicki A, Chabielska E, Pawlak R, Szemraj J, Buczko W, 2005. Angiotensin II enhances thrombosis development in renovascular hypertensive rats. Thromb. Haemost 1069–1076. 10.1160/TH04-10-0701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naasani LIS, Rodrigues C, de Campos RP, Beckenkamp LR, Iser IC, Bertoni APS, Wink MR, 2017. Extracellular Nucleotide Hydrolysis in Dermal and Limbal Mesenchymal Stem Cells: A Source of Adenosine Production. J. Cell. Biochem 118, 2430–2442. 10.1002/JCB.25909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otsuka K, Ohno Y, Sasaki T, Yamakawa H, Hayashida T, Suzawa T, Suzuki H, Saruta T, 1997. Ovariectomy aggravated sodium induced hypertension associated with altered platelet intracellular Ca2+ in Dahl rats. Am. J. Hypertens 10, 1396–1403. 10.1016/S0895-7061(97)00312-9/2/AJH.1396.F3.JPEG [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawlinski R, Pedersen B, Erlich J, Mackman N, 2004. Role of tissue factor in haemostasis, thrombosis, angiogenesis and inflammation: lessons from low tissue factor mice. Thromb. Haemost 444–450. 10.1160/TH04-05-0309 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pendurthi UR, Williams JT, Rao LVM, 1997. Inhibition of tissue factor gene activation in cultured endothelial cells by curcumin. Suppression of activation of transcription factors Egr-1, AP-1, and NF-kappa B. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 17, 3406–3413. 10.1161/01.ATV.17.12.3406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng N, Clark JT, Wei CC, Wyss JM, 2003. Estrogen depletion increases blood pressure and hypothalamic norepinephrine in middle-aged spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertens. (Dallas, Tex. 1979) 41, 1164–1167. 10.1161/01.HYP.0000065387.09043.2E [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riewald M, Ruf W, 2002. Orchestration of Coagulation Protease Signaling by Tissue Factor 12, 149–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki T, Ohno Y, Otsuka K, Suzawa T, Suzuki H, Saruta T, 2000. Oestrogen attenuates the increases in blood pressure and platelet aggregation in ovariectomized and salt-loaded Dahl salt-sensitive rats. J. Hypertens 18, 911–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah BH, 2005. Estrogen stimulation of COX-2-derived PGI2 confers atheroprotection. Trends Endocrinol. Metab 16, 199–201. 10.1016/.J.TEM.2005.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wassmann S, Bäumer AT, Strehlow K, Van Eickels M, Grohé C, Ahlbory K, Rösen R, Böhn M, Nickenig G, 2001. Endothelial dysfunction and oxidative stress during estrogen deficiency in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Circulation 103, 435–441. 10.1161/01.CIR.103.3.435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, Wang H, Jessup JA, Lindsey SH, Chappell MC, Groban L, 2014. Role of estrogen in diastolic dysfunction. Am. J. Physiol. - Hear. Circ. Physiol 306. 10.1152/ajpheart.00859.2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. 17-β Estradiol levels in WKY and SHR ovariectomized rats.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.