Abstract

Background:

Radiomics is a type of quantitative analysis that provides a more objective approach to detecting tumor subtypes using medical imaging. The goal of this paper is to conduct a comprehensive assessment of the literature on computed tomography (CT) radiomics for distinguishing renal cell carcinomas from oncocytoma.

Methods:

From February 15th 2012 to 2022, we conducted a broad search of the current literature using the PubMed/MEDLINE, Google scholar, Cochrane Library, Embase, and Web of Science. A meta-analysis of radiomics studies concentrating on discriminating between oncocytoma and RCCs was performed, and the risk of bias was assessed using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies method. The pooled sensitivity, specificity, and diagnostic odds ratio (DOR) were evaluated via a random-effects model, which was applied for the meta-analysis. This study is registered with PROSPERO (CRD42022311575)

Results:

After screening the search results, we identified 6 studies that utilized radiomics to distinguish oncocytoma from other renal tumors; there were a total of 1064 lesions in 1049 patients (288 oncocytoma lesions vs 776 RCCs lesions). The meta-analysis found substantial heterogeneity among the included studies, with pooled sensitivity and specificity of 0.818 [0.619– 0.926] and 0.808 [0.537– 0.938], for detecting different subtypes of RCCs (clear cell RCC, chromophobe RCC, and papillary RCC) from oncocytoma. Also, a pooled sensitivity and specificity of 0.83 [0.498– 0.960] and 0.92 [0.825– 0.965], respectively, was found in detecting oncocytoma from chromophobe RCC specifically.

Conclusions:

According to this study, CT radiomics has a high degree of accuracy in distinguishing RCCs from RO, including chRCCs from RO. Radiomics algorithms have the potential to improve diagnosis in scenarios that have traditionally been ambiguous. However, in order for this modality to be implemented in the clinical setting, standardization of image acquisition and segmentation protocols as well as inter-institutional sharing of software is warranted.

Keywords: Renal Cell Carcinoma, Oncocytoma, Machine learning, Systematic review, Clear Cell RCC, Chromophobe RCC, Papillary RCC

Introduction

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common type of kidney cancer in the United States, accounting for around 3.64 percent of all cancer cases reported(1). In the modern era, most renal tumors are incidentally discovered on imaging and present as small, localized entities (i.e., <4 cm). A retrospective analysis of 18,000 patients who underwent partial nephrectomy in the community demonstrated that more than 30% of all surgically excised small renal masses (SRMs) were consistently confirmed to be benign when the diagnosis was made only on the basis of CT(2). Renal oncocytomas (ROs) are one of the most common benign renal lesions. Although presence of a central stellate scar has traditionally been cited as pathognomonic for RO, only 25–30% of such tumors have this finding (3). Additionally, about 20% of chromophobe RCCs may also have a central scar (4). As such, RO can often be difficult to diagnose on radiographic appearance alone from chromophobe; clear cell; and/or papillary RCC. While renal mass biopsy (RMB)is a management option for SRM, it is an invasive procedure with the potential for complications. Furthermore, intra-tumoral heterogeneity may affect the diagnostic accuracy of RMB; for instance, a chromophobe RCC may be falsely diagnosed as an oncocytic tumor based on sampling location, as chromophobe RCC and RO have overlapping histological and molecular characteristics, which makes distinguishing them radiographically and/or through RMB especially challenging (5–9). While it is critical to avoid surgery on benign kidney lesions, our current diagnostic approaches (i.e., traditional cross-sectional imaging and RMB) have limitations.

Radiomics is the quantitative analysis of images on a pixel or voxel basis. There is a growing interest and utilization of radiomics for both tumor characterization (e.g. grading and differentiation) and clinical prediction (e.g. survival)(13–17).The contemporary usage of radiomics in RCC has mostly focused on increasing the accuracy of preoperative, non-invasive histologic subtyping of small renal tumors in order to betterinform management.(18) Given the large amount of features extracted from images (e.g., shape; intensity; and spatial relationship of voxels), radiomics is often paired with machine learning (ML) or deep learning (DL) in order to derive meaningful relationships between features and a relevant clinical outcome. In this study, we sought to conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis for studies utilizing CT based radiomics in order to differentiate ROs from (1) RCCs and (2) chRCC specifically.

Methods:

Search strategy

We conducted a search using PubMed/MEDLINE, Google scholar, Cochrane Library, Embase, and Web of Science on studies published from February 15th 2012 to 2022 in English. The following phrases were utilized in a search method that included a combination of keywords and medical subject headings (MeSH)/EMTREE terms: Search terms: (Radiomics OR Artificial Intelligence OR Machine learning OR Deep learning) AND (Kidney OR Renal) AND (Oncocytoma). This study is registered with PROSPERO (CRD42022311575).

Eligibility criteria.

The studies were chosen based on the following criteria: (1) Original full-text studies on CT radiomics clinical investigations to analyze the accuracy of identifying RO and RCCs(clear cell RCC(ccRCC), chromophobe RCC (chRCC), and papillary RCC (pRCC)), (2) Absolute numbers of patients with true positive (TP), false positive (FP), true negative (TN), and false negative (FN) results needed to be either found in published articles or recalculated in the manuscripts using other parameters (e.g., accuracy rate, sensitivity (SEN), specificity (SPE), positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), and a total number of participants). (3) Patients’ histopathological data was available, which served as a gold standard for comparing model performance.

Study selection and data extraction

The articles were screened independently by the 2 authors (NG, FH) based on the titles and abstracts using the Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne Australia, available at www.covidence.org); those not meeting the inclusion criteria stated above were eliminated. If necessary, any disagreements in included articles between the two screeners were reconciled by a third author (PY). After this initial phase, the full texts of all remaining articles were independently reviewed by two authors (PY, FH) for inclusion or exclusion in the final study. Conflicts were resolved in the same way as during the initial screening phase (FDF). Two authors (FH, FDF) extracted the study characteristics from each included study. Disagreements with extracted data were resolved through discussion and consensus or by consulting a third member (NG) of the review team. The data included the following: author, year of publication, , machine learning algorithm, study design, accuracy, validity, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and area under the curve (AUC).

Quality assessment of included studies

Since no established quality assessment tool focuses on machine learning methodology, we used a modification of the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies 2 (QUADAS-2) (20).

Data analysis

Published data were extracted and transformed into a datasheet using the reported true-positive, true-negative, false-positive, and false-negative values for distinguishing RO and RCCs. For the meta-analysis, the pooled SEN and SPE with 95% confidence intervals for diagnosis by AI were calculated using a random-effects model. Datasets were used to create forest plots and risk of bias graphs. The risk of publication bias was assessed using funnel plot and symmetry analysis. We plotted the 95% CI and prediction regions around the averaged accuracy estimates in the summary receiver operating characteristic (SROC) space, and the AUC was calculated. All statistical analyses were performed using R software, version 3.5.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2018).

Assessment of heterogeneity

Initially, statistical heterogeneity was evaluated informally from the forest plots of the study estimates and more formally using the I2 statistic (I2> 50%=significant heterogeneity). A hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic curve was also fitted. All studies were presented as a circle and plotted with the hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic curve. The heterogeneity and threshold effect of the included studies were also determined. An I2 test with P < 0.1 generally indicated significant heterogeneity.

Results

Research and selection of studies

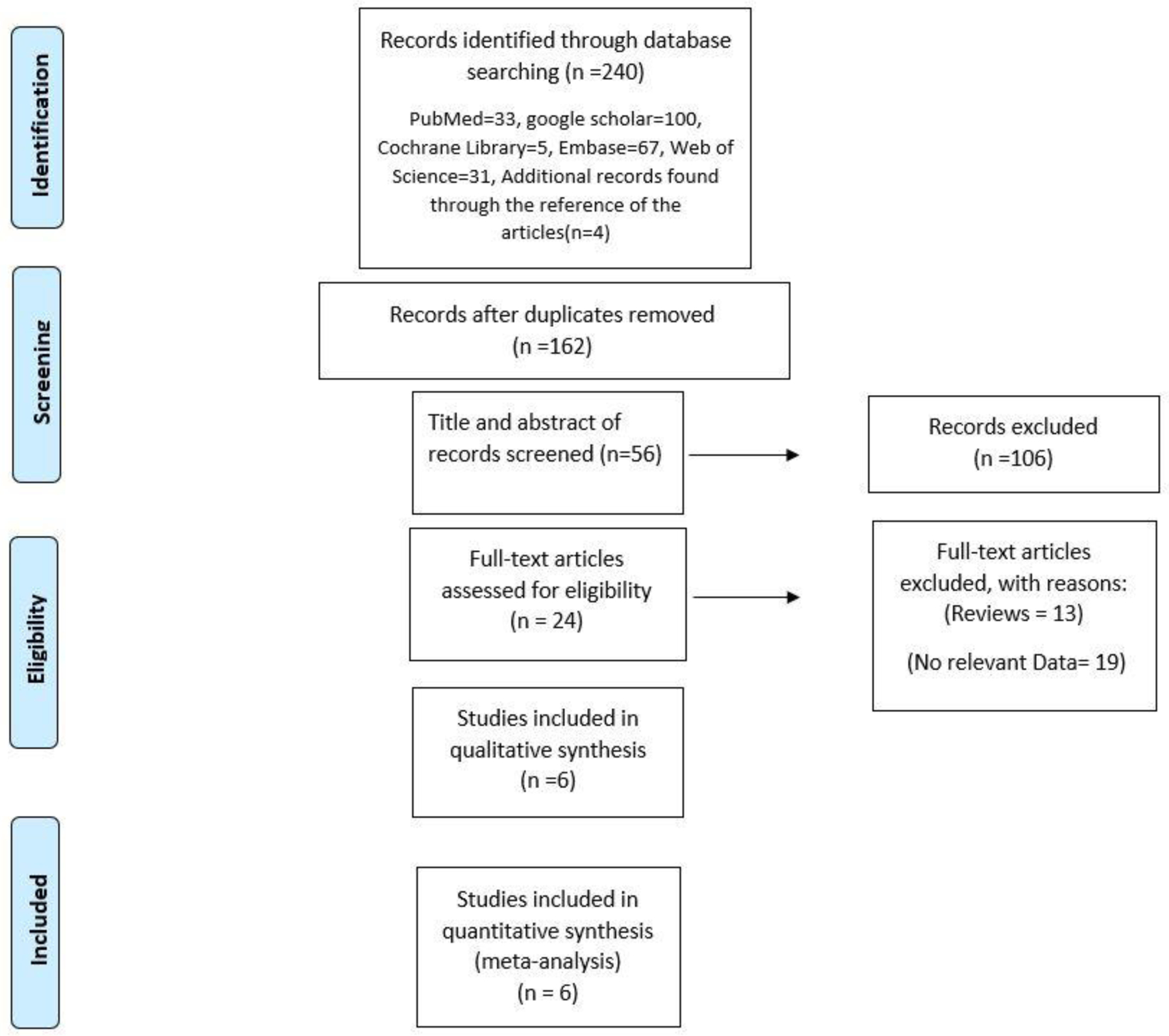

Using the search terms specified above, 240 articles were initially identified from all databases. Finally, 162 articles were included after duplications removed. In addition, 106 papers were eliminated after being deemed irrelevant after reading their titles and abstracts. After reading the entire full texts, it was discovered that 13 publications were reviews or had no relevant data, while seven papers were unavailable for data extraction. In the end, six studies were included(Table 1, 2). The article selection procedure is depicted in Figure 1. We do not have available data to do meta-analysis to calculate sensitivity, specificity, AUC, and accuracy of radiomic algorithms to differentiate RO vs. individual RCC subtypes (i.e., ccRCC; pRCC; chRCC). However, we were able to do meta-analysis on RO vs. RCCs as a whole.

Table 1.

Characteristics of related studies comparing RO with RCCs.

| Number | Author | Year | Methods | Number of Patients | Segmentation Method | Segmented region (2D (Largest diameter), 3D (whole volume) | Subtypes | Best Performance of model (best performing combination of model) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single institution/multi center | Feature selection – Number (first, higher-order, shape, etc.) | CT Phase (s) | Model | Sensitivity (sd if mean available) | Specificity (sd if mean available) | ||||||||

| 1 | Sasaguri | 2015 | CT texture features, Subjective radiology features | RCC: 123 (128 lesions: 24 pap; 104 cc and others), RO:43 (53 lesions) | Manually | 2D (largest possible ROI)-5 mm | 1. RCC vs RO 2. RO vs cc and other 3. RO vs pap | Single | quantitative tumor texture parameters (part of first orders), CT tumor attenuation values | CMP, NP | multinomial logistic regressi on model | 77.7 | 28.3 |

| 2 | Yajuan Li | 2019 | Radiomics/CT Texture analysis | chRCC:44, RO:17 | Manually | 3D (2D on all slices)-2.5 mm | RO vs chRCC | Single | First order, Shape and NP, and texture excretory features phases (GLCM, GLRLM, GLZM), higher orders | CMP & NP, and excretory phases | SVM, k-nearest neighbors, Random forest, Logistic regression, multilayer perception | 99 | 80 |

| 3 | Heidi Coy | 2019 | DL | RO: 51 ccRCC: 128 | Manually | 3D (2D on all slices) | RO vs cc RCC | Single | N/A | Unenhanced, CMP & NP, and excretory phases | neural network model | 85.2 | 52.9 |

| 4 | Amir Baghdadi | 2020 | DL | chRCC: 11, V RO: 9 | Manually | 3D | RO vs chRCC | Single | tumor-to-cortex peak early-phase enhancement ratio (PEER) | Non-contrast phase and the earliest phase of post-contrast in multiple phases | convolutional neural networks (CNNs) | 100 | 89 |

| 5 | Deng | 2020 | CT Texture analysis | Total: 354 RCCs (ccRCC: 244, pRCC: 46, chRCC: 56), RO: 111, fp-AML: 31 | Manually | 2D | RO vs chRCC | Single | CT texture analysis using filtration histogram based parameters | portal venous phase | LR | 34 | 93 |

| 6 | Xiaoli Li | 2021 | Radiomics/CT Texture analysis | chRCC: 94 (56 training, 38 validation), RO: 47 (28 training, 19 validation) | Manually | 3D (2D on all slices) | RO vs chRCC | 2 Centers | Subjective CT analysis + First order, second order, and higher order features + Radiomics Nomogram | CMP & NP, and excretory phases | LASSO logistic regression model, radiomics nomogram model | 89.5 | 97.4 |

RO, renal oncocytoma; MLA, machine learning algorithm; CNN, Convolutional Neural Networks; SVM, support vector machine; UP, Unenhanced phase; CMP, corticomedullary phase; NP, nephrographic phase; GLCM, gray-level co-occurrence matrix; GLSZM, gray-level-size zone matrix; GLRLM, gray-level run-length matrix; NGTDM, gray-tone difference matrix; GLDM, gray-level-dependence matrix

Table 2.

Information of five studies with unavailable data.

| Number | Author | Year | Methods | Number of Patients | Segmentation Method | Segmented region (2D (Largest diameter), 3D (whole volume) | Subtypes | Best performance of model (best combination of model) performing | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single institution/multi center | Feature selection – Number (first, higher-order, shape, etc.) | CT Phase (s) | Model | Sensitivity (sd if mean available) | Specificity (sd if mean available) | ||||||||

| 1 | HeiShun Yu | 2017 | Radiomics/CT Texture analysis | Total: 124, RO:10, chRCC: 22, ccRCC:46, papillary RCC: 41 | Manually | 2D on 10 consecutive slices | 1. RO vs ccRCC, 2. RO vs chRCC, 3. RO vs RCC | Single | Histogram features, second orders (GLCM, GLRLM, and GLCM), and Law’s features | portal venous phase | SVM | - | - |

| 2 | Bino A. Varghese | 2019 | Wavelet CT Texture analysis | ccRCC: 68 RO: 28 | Manually | 3D | RO vs ccRCC | Single | wavelet-based texture features, Haralick texture features | Unenhanced, CMP & NP, and excretory phases | multivariate model | - | - |

| 3 | Fatemeh Zabihollahy | 2020 | DL | RCC: 238 (ccRCC: 123, papRCC: 69, chRCC: 46) RO: 57 | Manually | 3D (2D on all slices) | RCC vs RO | Single | N/A | portal venous and NP | CNN | - | - |

| 4 | Johannes Uhlig | 2020 | Radiomics/CT Texture analysis | ccRCC: 131, RO: 16 | Manually | 3D | RO vs ccRCC | Single | First order, shape, and second order features + age and gender | venous phase | xgboost in SMOTE (has other Algorithms as well in table 10) | - | - |

| 5 | Akshay Jaggi | 2021 | Radiomics/CT Texture analysis | RO: 42, chRCC: 60 | Semi-automatic | 3D (cluster of connected spherical samples) | RO vs chRCC | Single | First order, second order (GLCM), Haralick′s features and Laws′ filters | NP | random forest and AdaBoost | - | - |

RO, renal oncocytoma; MLA, machine learning algorithm; CNN, Convolutional Neural Networks; SVM, support vector machine; UP, Unenhanced phase; CMP, corticomedullary phase; NP, nephrographic phase; GLCM, gray-level co-occurrence matrix; GLSZM, gray-level-size zone matrix; GLRLM, gray-level run-length matrix; NGTDM, gray-tone difference matrix; GLDM, gray-level-dependence matrix

Figure 1.

Prisma chart for included studies

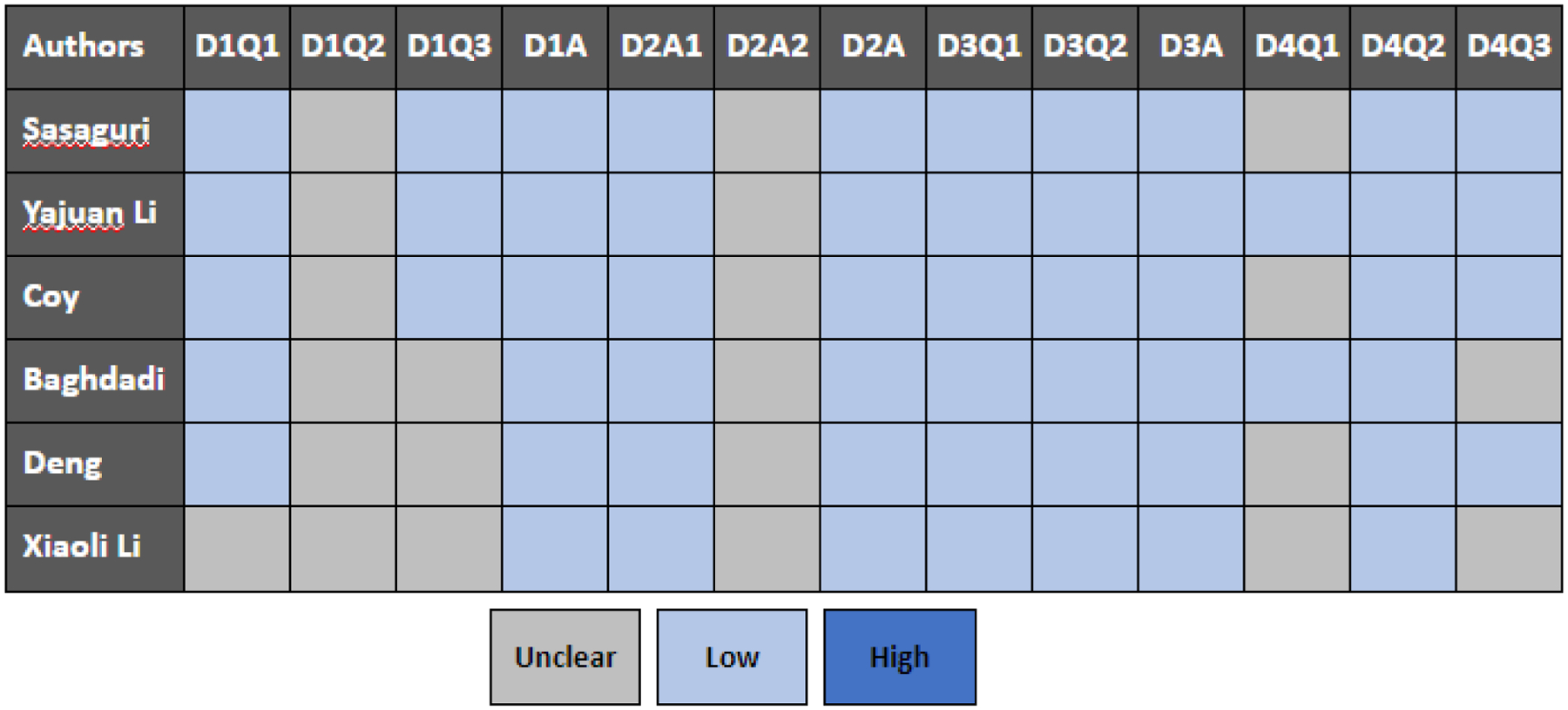

Quality assessment and publication bias

The quality of the included studies was evaluated using the QUADAS-2 checklist, and the results are shown in Figure 2. Overall, the quality of the studies that were included was satisfactory. Concerns about ‘risk of bias’ were raised when it was determined that ‘patient selection’ had problems that could imply bias in terms of inclusion (3 in group 2).

Figure 2.

Summary of QUADAS-2 assessments of included studies

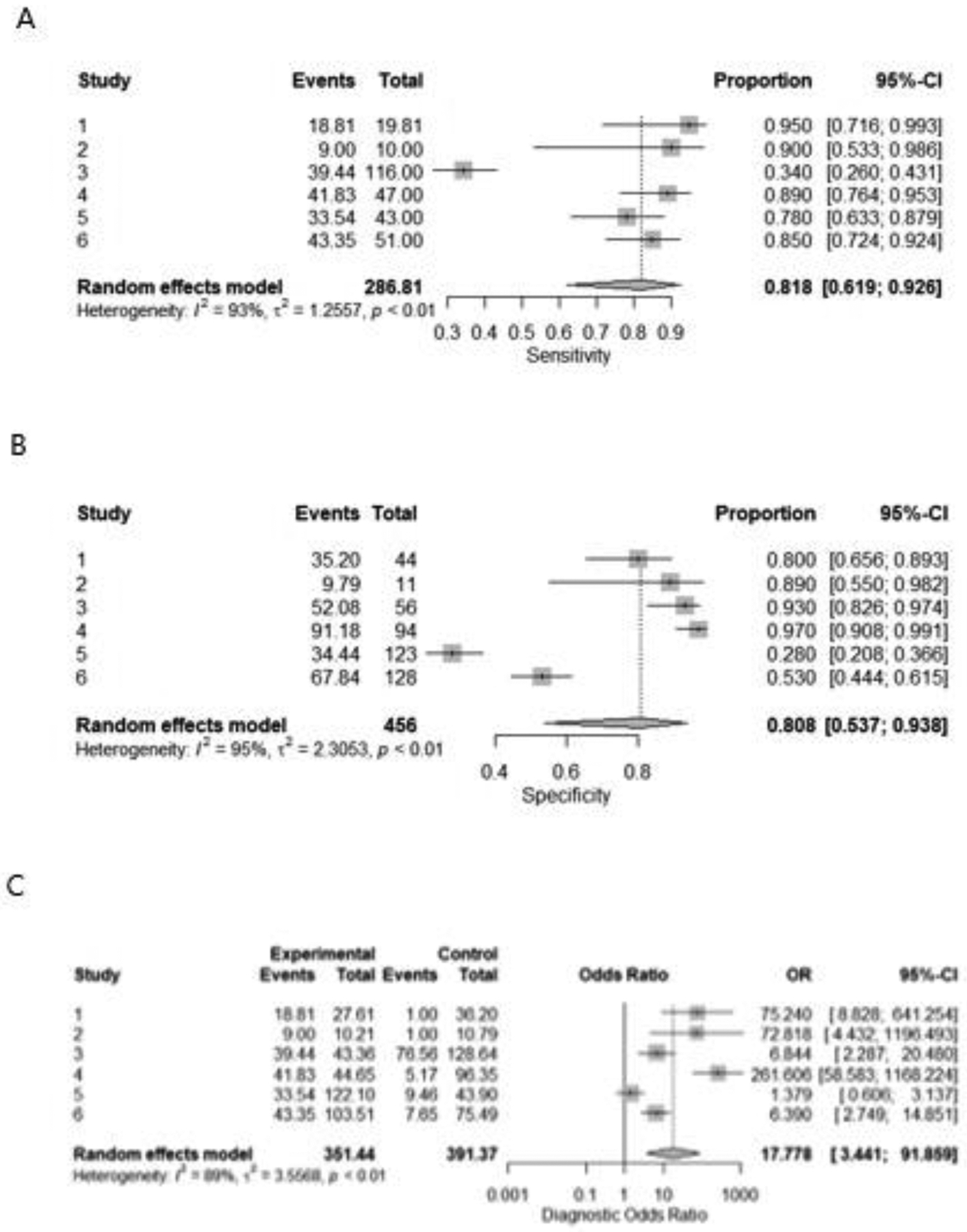

Heterogeneity test

Cochran-Q and I2 were used to assess heterogeneity (Figure 3). When we used the best model performance in differentiating RO from RCCs as well as chRCC, we found high heterogeneity in pooled sensitivity and specificity among the included studies.

Figure 3;

Forest plot for sensitivity(A), specificity(B), and odds ratio(C) of CT radiomics for differentiating between oncocytoma from renal cell carcinomas

Study characteristics

Table 1 lists the features of the 6 studies that were included. They were all retrospective cohort studies. There were 1049 patients in total, with 1064 lesions were found (288 oncocytoma lesions vs 776 RCCs lesions). Patient’s age ranged from 18 to 93. In the 6 studies that included data on CT slice thickness, 17 percent used CT slices with a thickness of 1–3 mm, while the rest used CT slices with a thickness of 5 mm. Figures 3 showed the results of the meta-analysis.

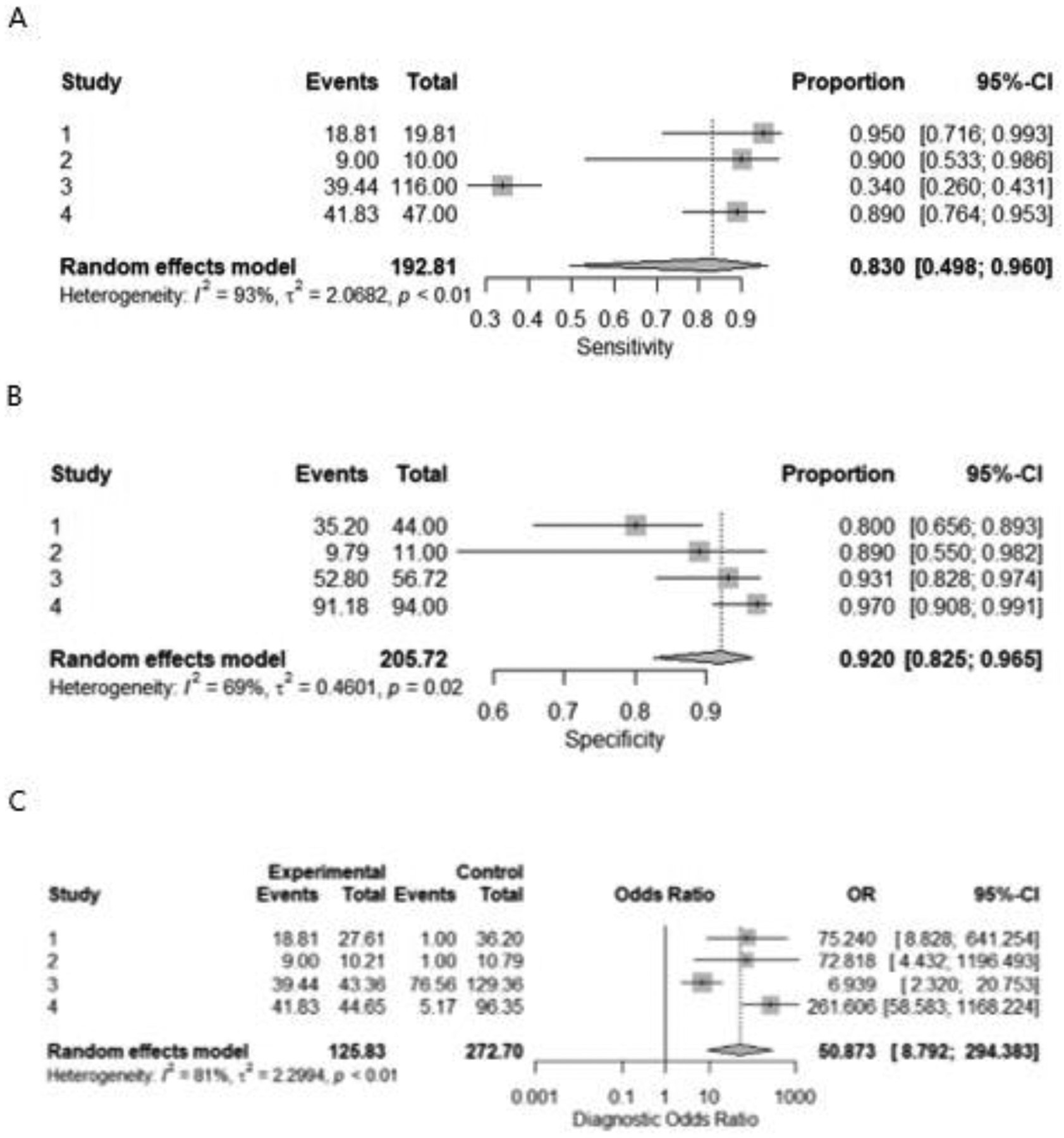

The pooled sensitivity, specificity, and odds ratio were 0.818 [0.619– 0.926], 0.808 [0.537– 0.938], and 17.777 [3.441–91.859], respectively for detection of RO from RCCs. (figure 3A, B, C) For identification of RO from chRCC specifically, the pooled sensitivity, specificity, and odds ratio were 0.83 [0.498– 0.960], 0.92 [0.825– 0.965], and 50.873 [8.792– 294.383], respectively. (figure 4A, B, C).

Figure 4;

Forest plot for sensitivity(A), specificity(B), and odds ratio(C) of CT radiomics for differentiating between oncocytoma from chromophobe renal cell carcinomas.

Discussion

Renal cancer incidence has grown from 1975 to 2016, owing mostly to increased incidental tumor detection on imaging investigations (21, 22). These tumors are frequently treated, although greater treatment has not resulted in a significant reduction in renal cancer mortality, raising concerns about overtreatment (2). As a result, improved risk categorization of incidentally detected cancers might help clinicians. Our findings suggested that CT radiomics has a strong diagnostic performance when it comes to distinguishing RO from RCCs, including RO from chRCC.

Granular cytoplasm is found in a subgroup of RCCs, the most prevalent of which are renal RO and chRCC (23). Both chRCC and RO arise from renal intercalated cells, accounting for 6–8% and 3–7% of all renal malignancies, respectively(24). ccRCC has a spectrum of imaging manifestations which may not always be distinguishable from oncocytoma.(25). Due to the overlapping radiological, histological, morphological, and histochemical characteristics, it is difficult for radiologists to identify malignant chRCC from benign renal RO in clinical work, even when relying on renal biopsy due to intra-tumoral heterogeneity. Despite the fact that some physiological parameters match, different management and follow-up procedures are used (26). From an oncologic standpoint, ROs do not require surgery due to their absent metastatic potential (27) while partial or radical nephrectomy is used to treat chRCC(28). As a result, distinguishing between chRCC and ROs is crucial when deciding on treatment options. The preferred and most prevalent non-invasive preoperative approach for the identification of renal tumorsis computerized tomography (CT), particularly dynamic contrast-enhanced (DCE)-CT. Due to overlapping imaging symptoms, radiologists still have difficulty distinguishing chRCC from RO (29).

Radiomics (13) is thus a promising technique for this diagnostic dilemma as it quantitatively assesses textures from medical images on a pixel basis, most of which is invisible to the human eye. It overcomes the potential sampling error of renal biopsy by comprehensively assessing the entire tumor (30–32) and has been employed as an imagingbiomarker for prognosis or prediction in a variety of studies (33, 34). Several studies have shown that radiomics can help discriminate between benign and malignant tumors(35), as well as predict tumor stage and prognosis(36, 37).

On computed tomography (CT) images, Baghdadi et al. developed a machine learning algorithm that distinguished between clear ccRCC and ROs with 95% accuracy. They created their machine by segmenting normal and abnormal kidney tissue and then assigning peak early-phase enhancement ratio (PEER) to malignancies using 192 renal masses. With 100% sensitivity and 89 percent specificity, their system detected regions of interest and subclassified histologically proven malignancies (39). Zabihollahy et al. developed a convolutional neural network (CNN) that could classify solid renal cancers based on CT scans as well. With 83.5 percent accuracy and 89.05 percent precision, their approach distinguished RCC from benign tumors (40).

On the other hand, chRCC was not investigated as a prevalent kind of RCC. Yu et al.(41) used a CT-based texture analysis model to distinguish between 46 ccRCC, 41 pRCC, 22 chRCC, and 10 RO, among other renal malignancies (n = 119). Histogram and gray-level characteristics were used in the texture analysis. The gray-level features were poor-to-fair discriminators of chRCC from RO, whereas the histogram feature median allowed classification of chRCC from RO with an AUC of 0.88.

With five machine learning classifiers, Li et al(4). established a CT-based radiomics technique that focused on the differential diagnosis of RO from chRCC. Radiomics characteristics were used to extract 1029 features from 17 RO and 44 chRCC. With AUC values more than 0.850, all five classifiers demonstrated good diagnostic performance. However, the RO sample size was limited, and clinical considerations (such as conventional imaging characteristics) were not taken into account in the analysis. Xiaoli Li et al.(42) enlisted 47 RO and 94 chRCC in their study, and all features were retrieved from the radiomics signature. In the validation set, the diagnostic performance of the clinical model, the radiomics signature, and the radiomic nomogram was 0.895, 0.957, and 0.988, respectively. When compared to prior radiomics studies, they exhibited several differences and advances. First, they focused on distinguishing RO from chRCC in patients with a central scar, as this is a common cause of misinterpretation in clinical practice. Second, because RO is a very uncommon renal tumor, just 47 individuals were enrolled in their study. This is, to our knowledge, the biggest number of samples used to distinguish RO from chRCC using radiomics signature. Third, the diagnostic performance of various models was evaluated using an external validation data set. The radiomics nomogram’s AUC in the validation data set was 0.988, indicating that the model had good diagnostic performance in the validation data set. This also implies a good predictive value on unfitting new data, demonstrating its robustness and predictive capacity.

However, the most useful predictor for distinguishing RCC from benign renal tumors, lp-AML from RCC, and RO from chrRCC was shown to be entropy. The randomness or irregularity of the grey-value distribution is represented by entropy, and heterogeneous tumors have a higher entropy(43). When compared to benign kidney tumors, RCC had consistently higher entropy. At fine spatial filter (SSF2), entropy greater than 5.62 exhibited a high specificity of 85.7 percent but a low sensitivity of 31.3 percent for predicting RCCs. In comparison to benign renal tumors, RCC showed decreased mean pixel value and maximum positive pixcel in addition to higher entropy. RCC, particularly ccRCC, is prone to degenerative alterations and central necrosis, which is the underlying cause. As a result, the average tumor attenuation is reduced(44–47). In the study by Deng et al.(48) RO had a higher entropy than chrRCC. A central stellate scar, haemorrhage, and a spoked-wheel enhancement pattern are all typical in RO, creating significant radiological intra-tumoural heterogeneity on post-contrast imaging, according to one theory(49–51). These findings backed up a prior study that revealed that RO had a higher standard deviation (SD) of attenuation values than chrRCC(49). Deng et al. also discovered a skewness difference between RO and chrRCC. The asymmetry of the histogram is measured by skewness. The left side of the histogram’s tail is longer than the right side, indicating negative skew(52). RO had a higher skewness than chrRCC at both medium and coarse spatial filters, indicating more radiological tumor heterogeneity.

There are various drawbacks to this study. To begin with, the sample size of most studies were modest, which could be due to the low clinical incidence of chRCC and RO and it may cause overfitting. The study’s most significant drawback is the minimal number of studies in this field for renal cell masses, as we had to exclude studies that compared various subgroups and reported different results, such as mean sensitivity and specificity. Second, because most studies had retrospective design conducted at a single location, generalizability is limited. Furthermore, studies that employed MRI to detect these groups were omitted. Furthermore, the variation process used in radiomics analysis, which is based on the numerical extraction technique to image analysis, could influence the outcomes of research due to bias and variance, rather than underlying physiological effects. Image capture, segmentation, feature engineering, statistical analysis, and reporting format standards should be developed to improve the reliability and generalization of ML-based radiomics research.

Conclusion

CT radiomics has a high degree of accuracy in discriminating RCCs from RO including chRCCs from RO, according to this study. However, a consistent approach and extensive sample-based inquiry are required to ensure the diagnostic accuracy of CT radiomics.

Highlights.

CT radiomics has a high degree of accuracy in distinguishing RCCs from renal oncocytomas (ROs), including chRCCs from ROs

Radiomics algorithms have the potential to improve diagnosis in scenarios that have traditionally been ambiguous

For this modality to be implemented in the clinical setting, standardization of image acquisition and segmentation protocols as well as inter-institutional sharing of software is warranted.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Howlader NNA, Krapcho M, Miller D, Brest A, Yu M, Ruhl J, Tatalovich Z, Mariotto A, Lewis DR, Chen HS, Feuer EJ, Cronin KA (eds). . SEER Cancer Statistics Review, 1975–2018, National Cancer Institute. . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim JH, Li S, Khandwala Y, Chung KJ, Park HK, Chung BI. Association of Prevalence of Benign Pathologic Findings After Partial Nephrectomy With Preoperative Imaging Patterns in the United States From 2007 to 2014. JAMA Surg. 2019;154(3):225–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wu J, Zhu Q, Zhu W, Chen W, Wang S. Comparative study of CT appearances in renal oncocytoma and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. Acta Radiol. 2016;57(4):500–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li Y, Huang X, Xia Y, Long L. Value of radiomics in differential diagnosis of chromophobe renal cell carcinoma and renal oncocytoma. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2020;45(10):3193–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asselin C, Finelli A, Breau RH, Mallick R, Kapoor A, Rendon RA, et al. Does renal tumor biopsies for small renal carcinoma increase the risk of upstaging on final surgery pathology report and the risk of recurrence? Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations. 2020;38(10):798.e9-.e16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marconi L, Dabestani S, Lam TB, Hofmann F, Stewart F, Norrie J, et al. Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Diagnostic Accuracy of Percutaneous Renal Tumour Biopsy. Eur Urol. 2016;69(4):660–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Herrera-Caceres JO, Finelli A, Jewett MAS. Renal tumor biopsy: indicators, technique, safety, accuracy results, and impact on treatment decision management. World J Urol. 2019;37(3):437–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abrahams NA, Tamboli P. Oncocytic renal neoplasms: diagnostic considerations. Clin Lab Med. 2005;25(2):317–39, vi. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Patel HD, Nichols PE, Su ZT, Gupta M, Cheaib JG, Allaf ME, et al. Renal Mass Biopsy is Associated with Reduction in Surgery for Early-Stage Kidney Cancer. Urology. 2020;135:76–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neves JB, Withington J, Fowler S, Patki P, Barod R, Mumtaz F, et al. Contemporary surgical management of renal oncocytoma: a nation’s outcome. BJU Int. 2018;121(6):893–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenkrantz AB, Hindman N, Fitzgerald EF, Niver BE, Melamed J, Babb JS. MRI features of renal oncocytoma and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;195(6):W421–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trevisani F, Floris M, Minnei R, Cinque A. Renal Oncocytoma: The Diagnostic Challenge to Unmask the Double of Renal Cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gillies RJ, Kinahan PE, Hricak H. Radiomics: Images Are More than Pictures, They Are Data. Radiology. 2016;278(2):563–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shu J, Wen D, Xi Y, Xia Y, Cai Z, Xu W, et al. Clear cell renal cell carcinoma: Machine learning-based computed tomography radiomics analysis for the prediction of WHO/ISUP grade. Eur J Radiol. 2019;121:108738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sun X, Liu L, Xu K, Li W, Huo Z, Liu H, et al. Prediction of ISUP grading of clear cell renal cell carcinoma using support vector machine model based on CT images. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019;98(14):e15022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yang G, Gong A, Nie P, Yan L, Miao W, Zhao Y, et al. Contrast-Enhanced CT Texture Analysis for Distinguishing Fat-Poor Renal Angiomyolipoma From Chromophobe Renal Cell Carcinoma. Mol Imaging. 2019;18:1536012119883161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang GM, Shi B, Xue HD, Ganeshan B, Sun H, Jin ZY. Can quantitative CT texture analysis be used to differentiate subtypes of renal cell carcinoma? Clin Radiol. 2019;74(4):287–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mühlbauer J, Egen L, Kowalewski K-F, Grilli M, Walach MT, Westhoff N, et al. Radiomics in Renal Cell Carcinoma—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers. 2021;13(6). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schieda N, Lim RS, McInnes MDF, Thomassin I, Renard-Penna R, Tavolaro S, et al. Characterization of small (<4cm) solid renal masses by computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging: Current evidence and further development. Diagnostic and Interventional Imaging. 2018;99(7):443–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whiting PF, Rutjes AWS, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, et al. QUADAS-2: A Revised Tool for the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2011;155(8):529–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Siegel RL MK, Jemal A. Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diaz de Leon A, Pedrosa I. Imaging and Screening of Kidney Cancer. Radiol Clin North Am. 2017;55(6):1235–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moch H, Cubilla AL, Humphrey PA, Reuter VE, Ulbright TM. The 2016 WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs-Part A: Renal, Penile, and Testicular Tumours. Eur Urol. 2016;70(1):93–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuthi L, Jenei A, Hajdu A, Németh I, Varga Z, Bajory Z, et al. Prognostic Factors for Renal Cell Carcinoma Subtypes Diagnosed According to the 2016 WHO Renal Tumor Classification: a Study Involving 928 Patients. Pathol Oncol Res. 2017;23(3):689–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang L, Gao L, Arefan D, Tan Y, Dan H, Zhang J. A CT-based radiomics model for predicting renal capsule invasion in renal cell carcinoma. BMC Med Imaging. 2022;22(1):15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richard PO, Jewett MAS, Bhatt JR, Evans AJ, Timilsina N, Finelli A. Active Surveillance for Renal Neoplasms with Oncocytic Features is Safe. The Journal of Urology. 2016;195(3):581–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kawaguchi S, Fernandes KA, Finelli A, Robinette M, Fleshner N, Jewett MA. Most renal oncocytomas appear to grow: observations of tumor kinetics with active surveillance. J Urol. 2011;186(4):1218–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGillivray PD, Ueno D, Pooli A, Mendhiratta N, Syed JS, Nguyen KA, et al. Distinguishing Benign Renal Tumors with an Oncocytic Gene Expression (ONEX) Classifier. Eur Urol. 2021;79(1):107–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Young JR, Margolis D, Sauk S, Pantuck AJ, Sayre J, Raman SS. Clear Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma: Discrimination from Other Renal Cell Carcinoma Subtypes and Oncocytoma at Multiphasic Multidetector CT. Radiology. 2013;267(2):444–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang YQ, Liang CH, He L, Tian J, Liang CS, Chen X, et al. Development and Validation of a Radiomics Nomogram for Preoperative Prediction of Lymph Node Metastasis in Colorectal Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(18):2157–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horvat N, Veeraraghavan H, Khan M, Blazic I, Zheng J, Capanu M, et al. MR Imaging of Rectal Cancer: Radiomics Analysis to Assess Treatment Response after Neoadjuvant Therapy. Radiology. 2018;287(3):833–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang GM, Sun H, Shi B, Jin ZY, Xue HD. Quantitative CT texture analysis for evaluating histologic grade of urothelial carcinoma. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2017;42(2):561–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seijo LM, Peled N, Ajona D, Boeri M, Field JK, Sozzi G, et al. Biomarkers in Lung Cancer Screening: Achievements, Promises, and Challenges. J Thorac Oncol. 2019;14(3):343–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feng Z, Rong P, Cao P, Zhou Q, Zhu W, Yan Z, et al. Machine learning-based quantitative texture analysis of CT images of small renal masses: Differentiation of angiomyolipoma without visible fat from renal cell carcinoma. Eur Radiol. 2018;28(4):1625–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Avanzo M, Wei L, Stancanello J, Vallières M, Rao A, Morin O, et al. Machine and deep learning methods for radiomics. Med Phys. 2020;47(5):e185–e202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Millet I, Curros F, Serre I, Taourel P, Thuret R. Can renal biopsy accurately predict histological subtype and Fuhrman grade of renal cell carcinoma? J Urol. 2012;188(5):1690–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bai X, Huang Q, Zuo P, Zhang X, Yuan J, Zhang X, et al. MRI radiomics-based nomogram for individualised prediction of synchronous distant metastasis in patients with clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Eur Radiol. 2021;31(2):1029–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wojtuch A, Jankowski R, Podlewska S. How can SHAP values help to shape metabolic stability of chemical compounds? J Cheminform. 2021;13(1):74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Baghdadi A, Aldhaam NA, Elsayed AS, Hussein AA, Cavuoto LA, Kauffman E, et al. Automated differentiation of benign renal oncocytoma and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma on computed tomography using deep learning. BJU Int. 2020;125(4):553–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zabihollahy F, Schieda N, Krishna S, Ukwatta E. Automated classification of solid renal masses on contrast-enhanced computed tomography images using convolutional neural network with decision fusion. European Radiology. 2020;30(9):5183–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu H, Scalera J, Khalid M, Touret A-S, Bloch N, Li B, et al. Texture analysis as a radiomic marker for differentiating renal tumors. Abdominal Radiology. 2017;42(10):2470–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Li X, Ma Q, Nie P, Zheng Y, Dong C, Xu W. A CT-based radiomics nomogram for differentiation of renal oncocytoma and chromophobe renal cell carcinoma with a central scar-matched study. Br J Radiol. 2022;95(1129):20210534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hayano K, Tian F, Kambadakone AR, Yoon SS, Duda DG, Ganeshan B, et al. Texture analysis of non-contrast-enhanced computed tomography for assessing angiogenesis and survival of soft tissue sarcoma. Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography. 2015;39(4):607–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hsieh JJ, Purdue MP, Signoretti S, Swanton C, Albiges L, Schmidinger M, et al. Renal cell carcinoma. Nature Reviews Disease Primers. 2017;3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kay FU, Pedrosa I. Imaging of Solid Renal Masses. Radiologic Clinics of North America. 2017;55(2):243–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sasaguri K, Takahashi N, Gomez-Cardona D, Leng S, Schmit GD, Carter RE, et al. Small (< 4 cm) renal mass: Differentiation of oncocytoma from renal cell carcinoma on biphasic contrast-enhanced CT. American Journal of Roentgenology. 2015;205(5):999–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galia M, Albano D, Bruno A, Agrusa A, Romano G, Di Buono G, et al. Imaging features of solid renal masses. The British Journal of Radiology. 2017;90(1077):20170077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Deng Y, Soule E, Cui E, Samuel A, Shah S, Lall C, et al. Usefulness of CT texture analysis in differentiating benign and malignant renal tumours. Clin Radiol. 2020;75(2):108–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Choi JH, Kim JW, Lee JY, Han WK, Rha KH, Choi YD, et al. Comparison of computed tomography findings between renal oncocytomas and chromophobe renal cell carcinomas. Korean J Urol. 2015;56(10):695–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Woo S, Cho JY, Kim SH, Kim SY. Comparison of segmental enhancement inversion on biphasic MDCT between small renal oncocytomas and chromophobe renal cell carcinomas. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201:598–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Davidson AJ, Hayes WS, Hartman DS, McCarthy WF, Davis CJ. Renal oncocytoma and carcinoma: failure of differentiation with CT. Radiology. 1993;186(3):693–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Miles KA, Ganeshan B, Hayball MP. CT texture analysis using the filtration-histogram method: what do the measurements mean? Cancer Imaging. 2013;13(3):400–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]