Abstract

Purpose

For many low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), breast cancer (BC) screening based on mammography is not a viable option. Clinical breast examination (CBE) may represent a pragmatic and cost-effective alternative. This paper examines the cost-effectiveness of CBE screening programme among a patient group for whom its cost-effectiveness is likely to be least evident (HER2-positive patients) and discuss the wider implications for BC screening in LMICs.

Methods

A Markov model was used to examine clinical and economic outcomes over a life-time horizon from the patient, public payer, and healthcare sector perspective. HER2-positive patients entered the model at either disease-free survival or metastatic BC state. The downstaging effect of CBE determined the starting probabilities in the no-screening and screening scenarios. The model used a monthly cycle length, with half-cycle correction. Costs and outcomes were discounted at 1.5% annually.

Results

Compared with no-screening, the cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) per quality-adjusted life-year gained for the CBE screening programme was $1801, $2381, and $4179 from three mentioned perspectives, respectively. The finding of cost-effectiveness remained robust to a range of sensitivity analyses. The parameters to which ICERs are most sensitive are average age of cohorts, reduction in proportion of metastatic patients at diagnosis, cost of CBE, and BC detection rate of the programme.

Conclusion

For HER2-positive patients and compared with no-screening, CBE screening programme in Vietnam is cost-effective from all investigated perspectives. CBE is a ‘good value’ intervention and should be considered for implementation throughout Vietnam as well as in LMICs where mammography is not feasible.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12282-022-01398-2.

Keywords: Clinical breast examination, Breast cancer, Cost-effectiveness analysis, Health economics, Low- and middle-income countries

Introduction

The perception that cancer is a disease of high-income countries (HICs) no longer holds true particularly regarding breast cancer (BC) as low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) currently account for the largest share (53%) of new cases worldwide [1]. The low 5-year survival rate in LMICs (which varies from 13 to 50% compared with more than 80% in HICs) may in part be explained by the high proportion of late stage of cancer at diagnosis [1]. This situation underscores the importance of early detection through screening. However, for many LMICs, the mammography-based screening programmes used in HICs are unlikely to be feasible or demonstrate sufficient value for money [2, 3]. WHO urges LMICs to look at alternative low-cost screening modalities like clinical breast examination (CBE) and analyse its cost-effectiveness before implementation [4]. In Vietnam, currently, there is no BC screening programme, although BC has the highest prevalence (among female cancers), the highest number of cancer-related deaths, an increasing incidence, and a high rate of late-stage cases at diagnosis (64.2% at stage III or IV) [5]. Thus, there is a need for a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) of a CBE screening programme versus no-screening.

Up to now, Lan NH et al. (2013) is the only study that conducted a CEA of CBE screening programme versus no-screening in Vietnam. The study adopted a public payer perspective with cost inputs based on 2001–2006 data and outcomes expressed as life-years lost (LYS). It concluded that CBE for women aged 40 to 55 years is highly cost-effective [6]. However, costs from this study were based on outdated data and provided poor estimates for the current situation due to advances in treatment such as the introduction of targeted therapy for HER2-positive patients. Besides, with the recent movement towards patient-centred care, measuring outcomes in terms of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) rather than just LYS and performing the CEA from the patient perspective are increasingly important [7], especially for Vietnam where patient out-of-pocket payment (OOP) accounted for approximately 45% of the total health expenditure in 2017 [8]. In this context, patients’ OOP in Vietnam should not be overlooked and assessing cost-effectiveness from other perspectives is needed.

The downstaging effect of CBE would be expected to increase survival and increase/reduce costs depending on BC subtype. The costs of treatment for general BC patients in Vietnam were 66% and 148% higher if they were diagnosed at stage II and III, respectively, compared with stage 0/I [5]. In contrast, the costs of treatment for HER2-positive patients would be expected to increase as patients diagnosed at earlier stage of BC (stage I–III) tend to opt for targeted therapy, while patients diagnosed with metastatic BC (stage IV) chose chemotherapy only to save cost. This choice pattern is a consequence of the remarkably higher cost of targeted therapy in Vietnam which was 10 times more expensive than the total cost of all other treatments combined due to its high cost in nature and low coverage from health insurance (48% for Trastuzumab and 0% for Pertuzumab) [5]. However, if CBE screening is shown to be cost-effective among HER2-positive patients for whom a rise in treatment cost related to earlier detection is likely to be greatest, it is highly likely that it will be even more cost-effective for all BC patients. In this context, the fascinating question is how cost-effective CBE screening programme is among HER2-positive patients.

This paper presents the results from a CEA of a CBE screening programme versus no-screening for the group of HER2-positive patients. The study adopts not only a public payer perspective but also a patient perspective and an overall healthcare (patient plus public payer) perspective for the analyses.

Methods

Breast cancer progression from the point it is diagnosed to when treatment is performed and afterwards until the death was modelled using a multi-state Markov model, constructed in Microsoft Excel. To increase the comparability of results, we used the model published by Younis T et al. (2020) which resembles the structures published by other authors and accepted by several health technology assessment agencies [9].

Model structure

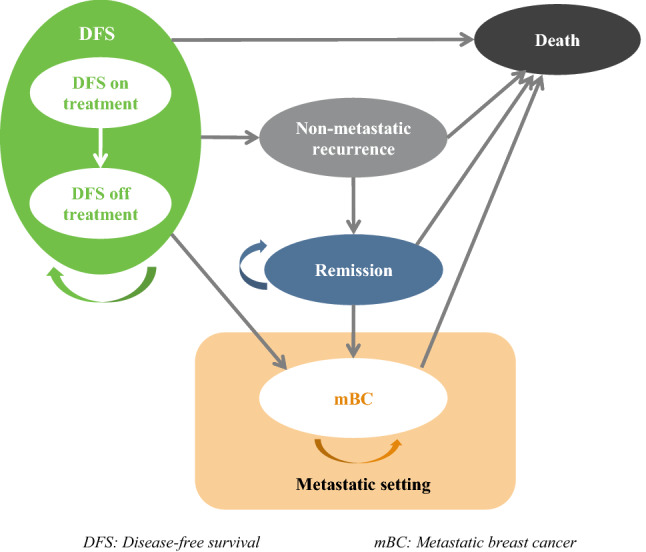

Figure 1 provides a schematic view of the model structure and the transitions between six health states: (1) Disease-free survival (DFS) on-treatment, (2) DFS off-treatment, (3) Non-metastatic recurrence (i.e., local/regional recurrence), (4) Remission, (5) Metastatic breast cancer-mBC, and (6) Death. Patients entered the model in either the DFS or mBC health state depending on their initial diagnosis at stage I/II/III or IV, respectively. Patients can remain in DFS off-treatment, remission, or mBC state as long as they did not experience recurrence or death. Patients in the DFS on-treatment state and non-metastatic recurrent are assumed to receive either targeted therapy or chemotherapy that lasts maximum 12 months (= standard length of treatment for targeted therapy), meaning that patients can only remain in these health states for that maximum length of time.

Fig. 1.

Model of breast cancer progression from diagnosis, to and after treatment

The model uses a monthly cycle length, with half-cycle correction applied, to account for mid-cycle transition. The starting age of patients in the model is 44 years which was the mean age at diagnosis of HER2-positive patients in Vietnam. A discount rate of 1.5% was applied to both costs and outcomes [10]. Other discount rates (0–3.5%) were used in sensitivity analyses.

Parameters and data resources

Starting and transition probabilities

Inputs for starting and transition probabilities were derived from the literature. The starting probabilities describe the initial distribution of the patients into DFS and mBC health states, and were deemed to differ between screening and no-screening scenario due to the downstaging effect of CBE. Starting probabilities in no-screening scenario were obtained from a BC epidemiological study among Vietnamese women in the period of 2001–2007 [11]. Starting probabilities in CBE screening scenario were derived from a pilot CBE screening programme run in eight provinces of Vietnam in 2008–2010 [12].

The probability of remaining in the DFS health state has been estimated based on a parametric function that was fitted to the Kaplan–Meier DFS curves derived from patient-level data of the HERceptin Adjuvant (HERA) trial (data were supplied in personal communication with Roche—funder of the HERA trial). If not remaining, patients can experience recurrence or death. Apart from DFS curves, the transition probabilities from DFS to recurrence were further adjusted by the cure threshold, maximum cure rate, and the split between non-metastatic recurrence and mBC [13].

The probability of moving from non-metastatic recurrence to remission was based on treatment guidelines. Due to the absence of data in Vietnam, the probability of moving from remission to mBC was based on a Canadian study of 12,836 BC patients [14].

Mortality probabilities of patients in DFS, non-metastatic recurrence, and remission were based on the background mortality derived from Vietnamese life tables [15] (In HERA trial, the risk of dying for patients in these health states was lower than the background mortality). The mortality probability of mBC HER2-positive patients was assumed to be the same with that of general BC patients reported in the study of Lan NH et al. (2013) [16].

Costs and utilities’ inputs

Inputs for costs (from patient perspective) and utilities were derived from a sub-sample of only HER2-positive patients/survivors in a study on HRQoL of Vietnamese BC patients/survivors and cost of treatment. Details of these studies methodology and results on HRQol and cost of treatment among general BC patients/survivors (full sample) are available elsewhere [5, 17]. Cost inputs for health services and drugs from public and the payer perspective were obtained from public health service price list regulated by Ministry of Health [18] and National Cancer Hospital (data were supplied in personal communication), respectively.

The model was run with three scenarios of cost inputs: (i) patient perspective (i.e., out-of-pocket payment), (ii) public payer perspective (i.e., social health insurance), and (iii) healthcare sector perspective [i.e., the sum of (i) and (ii)]. Due to the absence of data, only direct medical costs were included (i.e., direct non-medical costs and indirect costs were excluded). The costs incurred by patients and by public payer were mutually exclusive. All costs were adjusted to 2019 price year using a Gross Domestic Product deflator index for Vietnam and are presented in Vietnamese Dong (VND) and US dollars ($).

The model outcomes were expected quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). Utilities of non-metastatic recurrence and remission health states were assumed to equal those of DFS on-treatment and DFS off-treatment, respectively.

Cost-effectiveness analysis

The same simulated population was modelled in CBE screening and no-screening scenarios. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) was calculated by dividing the difference in costs by the difference in QALYs between the two scenarios. According to WHO, interventions with ICERs less than 1–3 times gross domestic product (GDP) per capita are considered as highly cost-effective or cost-effective, respectively [19]. The respective thresholds for Vietnam were 63.2 million VND (~ $2776) and 189.6 million VND (~ $8331) [20].

Sensitivity analyses

In deterministic sensitivity analysis (DSA), the parameters were manually changed and the impact of the change on results was analysed. As recommended by Gray et al. (2011), the range of variation for parameters derived from primary data or previous studies was based on the 95% confidence interval of such parameters [21]. Where the dispersion of the parameter was not available from data source, the range of variation would be ± 20% of the base-case [21]. In probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA), the choice of distributions for parameters followed the recommendation by Briggs et al. (2006) [22]. The DFS curves were described by multivariate normal distributions. Transition probabilities and utility values were modelled using beta distributions. Costs were modelled using a log-normal distribution. PSA was carried out by randomly selecting values from the chosen distributions for each parameter using Monte Carlo simulation. The number of iterations was 2000. Results from these iterations are presented in cost-effectiveness plane (C–E plane) and cost-effectiveness acceptability curve (CEAC).

Results

Starting and transition probabilities used as input parameters in the model are presented in Table 1. The starting probabilities for DFS state were 0.833 in no-screening scenario [11] and 0.924 in screening scenario [12]. Kaplan–Meier curves illustrating the probability of remaining in DFS health state overtime are shown in Supplement Information, Fig S1. The split between non-metastatic recurrence and mBC was based on the split seen in HERA trial in which 72% of the recurrences were mBC [13]. As in this trial, the risk of progression event is decreasing towards 0 at 10 years [13], a cure threshold at month 120th and a maximum cure rate of 95% were considered in the base-case analysis. As such, at month 120th, 95% of the cohorts are deemed cured and can no longer experience a recurrence. Cost inputs for the model, by three perspectives, are presented in Table 2, while utility inputs for all health states are presented in Table 3.

Table 1.

Starting and transition probabilities used as input parameters in the model

| Parameter | Input value | Source | Sensitivity analysis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Starting probabilities for DFS state | |||

| No-screening scenario | 0.833 | Duc et al. 2009 [11] (Vietnam data) | 0.724–0.874 |

| Screening scenario | 0.924 | Hung et al. 2012 [12] (Vietnam data) | NA |

| Transition probabilities from DFS | |||

| Probability of remaining in DFS | DFS curves | HERA trial* | DFS curves in Aphinity and Katherine trials* |

| DFS recurrences that were mBC** | 0.72 | Cameron et al. 2017 [13] (HERA trial, international data) | 0.576–0.864 |

| Cure threshold (maximum cure rate reached at month)** | 120 | 96–180 | |

| Maximum cure rate** | 0.95 | Assumption | 0–100 |

| DFS to death | Background mortality | WHO 2019 (Vietnamese life tables) [15] | NA |

| Transition probabilities from non-metastatic recurrence/remission | |||

| Non-metastatic to remission | Automatic after 12 months if alive | Assumption | NA |

| Remission to mBC | 0.0076 | Hamilton et al. 2015 [14] (Canada data) | 0.0061–0.0091 |

| Non-metastatic or remission to death | Background mortality | WHO 2019 (Vietnamese life tables) [15] | NA |

| Transition probabilities from mBC | |||

| mBC to death, year 1 | 0.0324 | Lan et al. 2013 [16] (Vietnam data) | Pooled |

| mBC to death, year 2 | 0.0446 | ||

| mBC to death, year 3 | 0.0492 | ||

| mBC to death, year 4 | 0.0511 | ||

| mBC to death, year 5 + | 0.0541 | ||

DFS Disease-free survival (patients were entered the model at stage I, II, or III); HERA trial: HERceptin Adjuvant trial; NA Not applicable; mBC metastatic breast cancer (stage IV breast cancer); WHO World Health Organization

Range used in sensitivity analysis was based on the 95% confidence interval of parameters (if available) or ± 20% of the base-case

*Data were supplied in personal communication with Roche–funder of the HERA trial

**Assumptions/inputs were used to further adjusted the transition probabilities of remaining in DFS/moving to recurrence (either non-metastatic or mBC)

Table 2.

Cost inputs for the model, by perspectives

| Unit: million Vietnamese dong | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Input by perspective (base-case) (1) Patient (2) Public payer (3) Healthcare sector |

Sensitivity analysis (± 20%) | ||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (2) | |

| Screening cost (one-off cost) | ||||

| Cost of CBE per person | 0.0066 | 0.0264 | 0.033 | 0.02–0.03 |

| Cost of CBE per diagnosis (= cost of CBE per person/the proportion of diagnostic positive patients from CBE. The latter was estimated at 0.06% [12]) | 11 | 44 | 55 | 33–55 |

| Diagnosis cost (one-off cost) | 2.76 | 0.79 | 3.55 | 0.59–0.98 |

| Treatment cost for DFS on-treatment or non-metastatic recurrence | ||||

| Monthly treatment cost – those who received chemotherapy only | 9.14 | 5.67 | 14.8 | 4.3–7.1 |

| Monthly treatment cost – those who received targeted therapy (e.g., Trastuzumab + chemotherapy) | 50.3 | 34.4 | 84.7 | 28.6–43.0 |

| Monthly follow-up care cost for DFS off-treatment or remission | 0.58 | 0.14 | 0.72 | 0.11–0.18 |

| Treatment cost for mBC | ||||

| Monthly targeted treatment cost for mBC patients (= cost of full course of targeted therapy/average time in mBC. The former typically lasts 12 months. The latter was estimated at 40 months) | 15.1 | 10.3 | 25.4 | 8.2—12.4 |

| Monthly supportive care cost for mBC patients (if not receive targeted therapy or after targeted therapy) | 1.23 | 0.24 | 1.47 | 0.18–0.30 |

(1) Cost inputs of diagnosis and treatment for DFS on-treatment/non-metastatic recurrence/mBC are from primary data. Cost inputs of follow-up care for DFS off-treatment/remission and supportive care for mBC were estimated from the primary data and Lan NH et al. 2013 [6]

(2) Cost inputs for health services were obtained from public health service price list regulated by Ministry of Health [18]. Cost inputs for drugs were obtained from National Cancer Hospital. Cost inputs of follow-up care for DFS off-treatment/remission and supportive care for mBC were obtained from Lan NH et al. 2013 [6]

(3) Cost inputs are the sum of costs incurred by patients and public payer ((1) + (2) = (3))

CBE Clinical breast examination; DFS Disease-free survival; mBC Metastatic breast cancer

Table 3.

Utilities for health states

| Health state | Mean | Mean, by age groups | Source | Sensitivity analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| < 40 | 40–49 | 50–59 | 60 + | ||||

| DFS on-treatment or non-metastatic recurrence | 0.7662 | 0.8182 | 0.7922 | 0.6900 | 0.6946 | Primary data, 2019 (Vietnam data) | Pooled (not adjusted by age) |

| DFS off-treatment or remission | 0.8545 | 0.9229 | 0.8663 | 0.8647 | 0.7729 | ||

| Metastatic breast cancer (mBC) | 0.6813 | 0.7275 | 0.7044 | 0.6135 | 0.6176 | Younis et al. 2020 [9] (Canadian data), adjusted proportionally based on primary data of Vietnam | |

DFS disease-free survival; HRQoL health-related quality of life

Table 4 shows the base-case results from the patient, public payer, and healthcare sector perspective. In all three perspectives, CBE screening programme brought about 1.1 QALYs and 1.3 life-years gained per person. The cost per QALYs gained was 41 million VND (~ $1801), 54.2 million VND (~ $2381), and 95.1 million VND (~ $4179), respectively, which suggests that from all perspectives, CBE screening programme would be considered as cost-effective.

Table 4.

Base-case results for cost-effectiveness analysis of screening programme based on clinical breast examination

| Unit for cost: million Vietnamese dong | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Life-years per person | QALYs per person | Total cost per person (in million VND) | ICER | ||

| Cost per life-year gained | Cost per QALY gained | ||||

| Patient’s perspective | |||||

| CBE | 14.5 | 12.5 | 511.9 | ||

| No CBE | 13.2 | 11.4 | 465.7 | ||

| CBE vs no CBE | 1.3 | 1.1 | 46.2 | 36.1 | 41.0 |

| Public payer’s perspective | |||||

| CBE | 14.5 | 12.5 | 325.6 | ||

| No CBE | 13.2 | 11.4 | 264.7 | ||

| CBE vs no CBE | 1.3 | 1.1 | 61.1 | 47.7 | 54.2 |

| Healthcare sector perspective | |||||

| CBE | 14.5 | 12.5 | 837.8 | ||

| No CBE | 13.2 | 11.4 | 730.5 | ||

| CBE vs no CBE | 1.3 | 1.1 | 107.3 | 83.9 | 95.1 |

| Threshold for highly cost-effectiveness | 63.2 | ||||

| Threshold for cost-effectiveness | 189.6 | ||||

CBE clinical breast examination; ICER incremental cost-effectiveness ratio; QALYs quality-adjusted life-year; VND Vietnamese dong (currency exchange rate in September 2021: $1 ~ 22,759 VND)

Each plot in the C–E plane (Supplementary Information, Fig S2) represents the result from one iteration of the Monte Carlo simulation, and shows the cost and effect difference between CBE screening and no-screening. All observations were in the northeast quadrant of the C–E plane, indicating that CBE programme has significantly higher costs and effects than no-screening. All observations were also within the cost-effectiveness threshold for intervention in Vietnam.

The curves in the CEACs for CBE screening versus no-screening (Supplementary Information, Fig S3) show the likelihood that CBE screening programme is cost-effective at various willingness to pay (WTP) thresholds. At the threshold of 63.2 million VND (~ $2776 = Vietnam GDP per capita), the CBE screening programme has 100% and 70% probability of being highly cost-effective from the patient and public payer perspective, respectively. From the healthcare sector perspective, the threshold needs to be 1.5 and 2.3 times higher for the CBE screening programme has reached 40% and 100% probability of being cost-effective, respectively.

The tornado diagrams in Fig. 2 present the DSA results from public payer perspective (results for other perspective are in Supplementary Information, Fig S4). The parameters to which ICERs are most sensitive are the average age of cohorts (or average age at diagnosis), reduction in proportion of women with mBC at diagnosis (which reflects the downstaging effect of CBE), cost of CBE, and BC detection rate of a CBE screening programme. Decreasing the reduction in proportion of mBC from 9.1% to 5% would increase ICER from 54.2 million VND to 84 million VND (~ $2381 to $3691). The ICER would increase to 72 million VND (~ $3164) if BC detection rate were reduced from 0.06% to 0.04%. When all costs of CBE were covered by public payer (coverage = 80% in base-case), the ICER would increase to 63 million VND (~ $2768). All increased ICERs were still lower than the cost-effectiveness threshold.

Fig. 2.

Results of deterministic sensitivity analysis, from public payer perspective

Changing the discount rate for costs (0–3.5%), model time horizon (30–60 years), the monthly treatment cost of those who did not receive targeted therapy, and the proportion of metastatic recurrence (58–86% among total recurrence) did not significantly impact the ICER value.

Discussion

A mammography-based screening for breast cancer is not economically feasible in many LMICs including Vietnam. The base-case analysis in this study has shown that a CBE-based screening programme would be cost-effective among HER2-positive patients for whom it would be most challenging to demonstrate cost-effectiveness. Screening increased the incremental QALYs per person. The downstaging effect of CBE resulted in the reduction of women in the mBC health state which was associated with the lowest utility value. Early stage BC also has better prognosis and longer survival time which is, in turn, associated with higher utility value (survivors have significant higher HRQoL compared with patients on-treatment [17]).

The implementation of CBE screening programme would also increase the cost incurred by both women and public payer. First, an increase in the number of patients diagnosed with stage I/II/III who are more likely to opt to targeted therapy compared to mBC patients (stage IV) significantly pushed the treatment cost higher, especially when cost of targeted therapy alone in Vietnam was 10 times higher than the total cost of all other treatments combined [5]. Patients with non-metastatic BC also faced recurrence along with cost of another treatment course; thus, the increase in number of these patients resulted in higher total cost in CBE screening scenario compared with no-screening scenario. Second, the cost of implementing the programme itself is an additional expense. Cost of CBE per person in Vietnam is remarkably cheap if compared with the cost of treatment. However, as BC detection rate from CBE screening programme (one was piloted in 2008–2010) was reported at just 0.06% [12], the cost per diagnosis was 1600 times higher than the cost of CBE per person. Thus, the detection rate plays an important role on the cost-effectiveness of the screening programme, as depicted in the DSA. This underscores the importance of efforts to retain a high detection rate including the training for doctors who perform CBE and perhaps targeting high-risk groups based on age for example.

The increase in both cost and effectiveness of CBE screening programme versus no-screening scenario yielded ICERs per QALY gained that suggest the programme is highly cost-effective from the patient and public payer perspective and cost-effective from the healthcare sector perspective. This is similar with the conclusion from studies in LMICs such as Ghana, India, and Peru where CBE screening was compared with no-screening scenario [23–25]. It should be noted that this result is highly context sensitive, and the comparator plays an important role. Studies in Japan—an HIC with a long-term, nation-wide population-based screening programme using CBE (1987–2003)—reported that CBE was not cost-effective if compared with mammography-based screening programme [26, 27]. These results, again, imply that a CBE screening programme would be cost-effective in countries where a screening programme has not been implemented yet and mammography is not feasible.

Results from PSA were consistent as all iterations of Monte Carlo simulations yielded ICERs that were lower than the cost-effectiveness threshold. The CEAC revealed that at threshold equalled to three times Vietnam GDP per capita, CBE screening programme has 100% probability of being cost-effectiveness in all perspectives. At threshold equalled to GDP per capita, it has 80 to 100% probability of being highly cost-effective from public payer and patient perspective, respectively.

Results from DSA showed that average age of cohorts (or average age at diagnosis), reduction in proportion of women with mBC at diagnosis (which reflects the downstaging effect of CBE), BC detection rate of a CBE screening programme, and the cost of CBE per person are the factors with biggest impacts on the cost-effectiveness of CBE screening programme. Of these, the average age at diagnosis of BC is a non-interventional factor dependent on epidemiological characteristics of BC in Vietnam. All other factors are related to the effectiveness and implementation of CBE screening programme. Efforts to alter these factors appropriately can contribute to increase the programme cost-effectiveness. Cost of CBE was regulated by Ministry of Health as in the category of physical examination in general which is unlikely to be changed for the sake of one programme. Reduction in proportion of mBC is linked with the detection rate as in more BC cases detected at earlier stage by screening may help decrease the proportion of mBC at diagnosis. This, once again, emphasises the necessity of improving detection rate through standardised screening process, continuous training, higher throughput, better follow-up with referral for further tests in suspicious cases, and perhaps targeting high-risk groups.

This is the first study in Vietnam that performed cost-effectiveness analysis of CBE screening programme compared with no-screening among HER2-positive patients. It is within a context of an immense burden in terms of financial and human cost of BC in Vietnam. Considering CBE screening programme is cost-effective for this particular vulnerable group, it is likely to be even more cost-effective for general BC patients among whom the potential for savings in treatment cost are even greater. Nevertheless, further research to confirm this prediction is still needed. The study is also the first to provide CEA from several perspectives including patients, public payers, and healthcare sector perspective; thus, it provides a more comprehensive picture on the cost-effectiveness of CBE screening programme in Vietnam. Most of the data inputs for the model were primary data which is recent and specific to Vietnamese patients to avoid one of the main criticisms for cost-effectiveness study from LMICs (i.e., poor quality due to the inappropriate estimates of cost and effectiveness based on data from HICs).

Despite its strength, the study has some limitations that should be considered when interpreting the findings. First, we have been compelled by the paucity of existing data on transition probabilities to group stages I–III BC to just one-state ‘early BC’ (eBC). While this follows practice adopted in the literature [9], inevitably, it will conceal heterogeneity in cost and outcomes between stages. However, among HER2-positive patients, it is noted that heterogeneity in treatment costs among eBC patients will be significantly lower than among BC patients generally by virtue of their eligibility for chemo/targeted therapy which is a key component of treatment costs. Moreover, it is noted that there is no significant difference in HRQoL among HER2-positive patients diagnosed at different stage of BC. These suggests that the forced abstraction is unlikely to be material. Second, due to absence of data, no direct non-medical costs and indirect costs were included. An analysis from societal perspective would provide a more complete view on cost-effectiveness of CBE screening programme in Vietnam. If as seems probable further savings can be achieved through avoided productivity losses for example, CBE may be even more cost-effective than suggested here. Third, the detection rate of CBE screening programme used in this CEA was from 2008 when the incidence of BC in Vietnam was around 13.8/100,000 women. More recent evidence indicates that the incidence rate was 34.2/100,000 women in 2020 [28]; ceteris paribus, this suggests that the detection rate should be higher than that modelled here which, in turn, will reduce ICER and make the programme more cost-effectiveness.

Conclusions

This analysis was not to assess the cost-effectiveness of CBE screening programme targeted only at HER2-positive women but rather to look at how cost-effective CBE screening programme is among this particular group mindful of the likelihood that among them it was least likely to be cost-effective.

For HER2-positive patients and compared with no-screening, the implementation of CBE screening programme in Vietnam is cost-effective from the healthcare sector perspective and highly cost-effective from the patient and public payer perspective. As HER2-positive patients have poorer prognosis and bear extensively higher cost of treatment for BC, it likely that a CBE screening programme would be highly cost-effective or even dominant for general BC patients. Given the results from conducting this CEA and the fact that it is infeasible to provide and deliver mammography, CBE is a ‘good value’ intervention and should be considered for implementation throughout Vietnam.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors express our sincerest thanks to Roche Products Ireland Limited and the National Cancer Hospital for their support in providing some data used in the modelling.

Author contributions

TTN, MD, and CON contributed to the study conception and design. TTN collected and provided the primary data as well as gathered the secondary data used in the modelling. TTN, SB, and MG populated the model. TTN, CON, and MD contributed to the interpretation of the findings. The first draft of the manuscript was written by TTN. CON, MD, and HVM provided supervisory support and reviewed this paper. All authors contributed to the revision of the manuscript and approved the final version.

Funding

The work reported in this paper was undertaken during TTN’s PhD studies which is funded by the Profs Murray-Yarnell PhD studentship from Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Queen’s University Belfast (United Kingdom). The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and supplementary materials.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics approval

This is a modelling study which did not require ethics approval.

Consent to publish

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Torre LA, Islami F, Siegel RL, Ward EM, Jemal A. Global cancer in women: burden and trends. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2017;26(4):444–457. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yoo KB, Kwon JA, Cho E, Kang MH, Nam JM, Choi KS, et al. Is mammography for breast cancer screening cost-effective in both Western and asian countries?: results of a systematic review. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev APJCP. 2013;14(7):4141–4149. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2013.14.7.4141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mandrik O, Ekwunife OI, Meheus F, Severens JL, Lhachimi S, Uyl-de Groot CA, et al. Systematic reviews as a “lens of evidence”: Determinants of cost-effectiveness of breast cancer screening. Cancer Med. 2019;8(18):7846–7858. doi: 10.1002/cam4.2498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization . WHO position paper on mammography screening. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ngan TT, Ngoc NB, Minh HV, Donnelly M, O'Neill C. Costs of breast cancer treatment incurred by women in vietnam. BMC Public Health. 2022 doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-12448-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lan NH, Laohasiriwong W, Stewart JF, Wright P, Nguyen YTB, Coyte PC. Cost-Effectiveness analysis of a screening program for breast cancer in vietnam. Value Health Reg Issues. 2013;2(1):21–28. doi: 10.1016/j.vhri.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tai B-WB, Bae YH, Le QA. A systematic review of health economic evaluation studies using the patient’s perspective. Value Health. 2016;19(6):903–908. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Out-of-pocket expenditure (% of current health expenditure) [Internet]. 2020 [cited December 12, 2020]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.OOPC.CH.ZS.

- 9.Younis T, Lee A, Coombes ME, Bouganim N, Becker D, Revil C, et al. Economic evaluation of adjuvant trastuzumab emtansine in patients with HER2-positive early breast cancer and residual invasive disease after neoadjuvant taxane and trastuzumab-based treatment in Canada. Curr Oncol. 2020;27(6):e578–e589. doi: 10.3747/co.27.6517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Guide to the methods of technology appraisal. London. 2013. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/process/pmg9/resources/guide-to-the-methods-of-technology-appraisal-2013-pdf-2007975843781 [PubMed]

- 11.Duc NB. Breast cancer situation in women in some provinces/cities from 2001 to 2007 [in Vietnamese] Vietnam J Oncol. 2009;1:5–11. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hung NT, Thuan TV. The screening results for early detection of breast and cervical cancer in some cities or provinces from 2008 to 2010 [in Vietnamese] J Pract Med. 2012;4(815):61–63. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cameron D, Piccart-Gebhart MJ, Gelber RD, Procter M, Goldhirsch A, de Azambuja E, et al. 11 years' follow-up of trastuzumab after adjuvant chemotherapy in HER2-positive early breast cancer: final analysis of the HERceptin Adjuvant (HERA) trial. Lancet (London, England) 2017;389(10075):1195–1205. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32616-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hamilton SN, Tyldesley S, Li D, Olson R, McBride M. Second malignancies after adjuvant radiation therapy for early stage breast cancer: is there increased risk with addition of regional radiation to local radiation? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2015;91(5):977–985. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Life tables by country [Internet]. WHO Global Health Observatory data repository. 2019 [cited 13 April 2021]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/gho/data/view.main.61830?lang=en.

- 16.Lan NH, Laohasiriwong W, Stewart JF. Survival probability and prognostic factors for breast cancer patients in Vietnam. Glob Health Action. 2013;6:1–9. doi: 10.3402/gha.v6i0.18860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ngan NH, Mai W, Minh JF, Donnelly JF, O'Neill JF. Health-related quality of life among breast cancer patients compared to cancer survivors and age-matched women in the general population in Vietnam. Qual Life Res. 2022;31(3):777–787. doi: 10.1007/s11136-021-02997-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ministry of Health. Circular on unifying prices of medical examination and treatment services covered by health insurance among hospitals of the same class across the country and guidelines for applying prices and payment for medical services in certain cases. No.: 39/2018/TT-BYT. Hanoi: Ministry of Health; 2018.

- 19.Marseille E, Larson B, Kazi DS, Kahn JG, Rosen S. Thresholds for the cost–effectiveness of interventions: alternative approaches. Bull World Health Organ. 2015;93:118–124. doi: 10.2471/BLT.14.138206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.World Bank. World Bank Open Data - Vietnam country profile [Internet]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/country/vietnam.

- 21.Gray AM, Clarke PM, Wolstenholme JL, Wordsworth S. Applied Methods of Cost-effectiveness Analysis in Health Care. New York: Oxford University Press; 2011. ISBN 978-0-19-922728-0.

- 22.Briggs A, Sculpher M, Claxton K. Decision Modeling for Health Economic Evaluation. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. ISBN 978-019-852662-9.

- 23.Zelle SG, Nyarko KM, Bosu WK, Aikins M, Niëns LM, Lauer JA, et al. Costs, effects and cost-effectiveness of breast cancer control in Ghana. Tropical Med Int Health. 2012;17(8):1031–1043. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2012.03021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Okonkwo QL, Draisma G, der Kinderen A, Brown ML, de Koning HJ. Breast cancer screening policies in developing countries: a cost-effectiveness analysis for India. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(18):1290–1300. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zelle SG, Vidaurre T, Abugattas JE, Manrique JE, Sarria G, Jeronimo J, et al. Cost-Effectiveness analysis of breast cancer control interventions in Peru. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(12):e82575. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0082575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Okubo I, Glick H, Frumkin H, Eisenberg JM. Cost-effectiveness analysis of mass screening for breast cancer in Japan. Cancer. 1991;67(8):2021–2029. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19910415)67:8<2021::AID-CNCR2820670802>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ohnuki K, Kuriyama S, Shoji N, Nishino Y, Tsuji I, Ohuchi N. Cost-effectiveness analysis of screening modalities for breast cancer in Japan with special reference to women aged 40–49 years. Cancer Sci. 2006;97(11):1242–1247. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00296.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Global Cancer Observatory: Cancer Today [Internet]. International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2020 [cited 12 April 2021]. Available from: http://gco.iarc.fr/today.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and supplementary materials.