Abstract

This study aimed to compare the effect of ohmic and conventional heat treatments on red guava pulp, evaluating the effects on pulp color, degradation kinetics of ascorbic acid and carotenoids, together with the thermal efficiency of both treatments. Samples were heated by conventional heating (water bath) and ohmic heating (platinum electrodes) using alternating voltage of 21.2 V/m and average frequency of 60 Hz at temperatures of 60, 70 and 80 °C for 110 min. In general, the ascorbic acid degradation followed a first order kinetics, for both heat treatments, the pulp color showed no significant variation (p < 0.05) according to the type and time of heating applied, whereas the carotenoid content was favored by ohmic heating, at the two lowest temperatures tested. As for the heat transfer process, the ohmic treatment showed an average thermal efficiency of 40.93%, while the conventional heating, 2.62%, proving to be a promising emerging technology for processing viscous foods with suspended particles like fruit pulps.

Keywords: Thermal treatment, Tropical fruit, Degradation kinetics

Introduction

Guava (Psidium guajava) is a tropical fruit that belongs to the family Myrtaceae, with high nutritional value and representing a source of vitamins and minerals (Jamieson et al. 2021). It also contains antioxidant pigments, such as carotenoids and polyphenols and therefore, among plant foods, it is an important source of antioxidants. Its seeds also stand out for the concentration of polyunsaturated fatty acids, such as omega 3 and 6 (Chiveu et al. 2019).

Guava is well accepted for fresh consumption, global guava exports grew to an estimated 2.3 Mt in 2021, a 3%increase over the previous year. This ranks the commodity cluster as the second fastest growing group among top tropical fruits in 2021 (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations 2022). Brazil leads the consumption of guava in the world and produces 0.424 Mt of the fruit annually. The shelf life of guava is short, as it is a climacteric fruit with high transpiration rate and rapid ripening with loss of mass and firmness. Depending on the cultivar, up to 35% mass loss can occur, especially when coming from countries with a hot climate. Thus, to reduce losses and add value to the product, guava-based pulp, juices and sweets are produced (Bibwe et al. 2022). However, depending on the processing and intensity of the heat treatment applied to the product, the availability of bioactive compounds may be compromised (Lima et al. 2019).

In the food industry, heat treatment is the most traditional preservation method as it is effective in inactivating and destroying undesirable enzymes and pathogenic microorganisms. It is also important in developing the sensory properties of food. Conventional heat treatment processes depend on heat transfer mechanisms (conduction and convection) for food products, and are often limited by thermophysical properties of the food, such as viscosity and fouling on the contact surface. The long exposure of food to heat compromises its nutritional and sensory quality (Fadavi et al. 2018).

In this sense, heat treatment by ohmic heating technology that has been studied and consists of passing an alternating electrical current through the food, which generates intermittent heat in the product, promoting faster and more homogeneous heating (Cappato et al. 2017). The main advantage of ohmic heating is its ability to heat materials in a fast and uniform fashion, including products with particulates. This treatment has been applied with great success in foods with high viscosity and suspended particles due to the solid and liquid phases that present the same heating rate. Therefore, overheating larger particles in more external zones is avoided, which has been analyzed as a preponderant factor in conventional heating (Salari and Jafari 2020). Furthermore, ohmic heating is more environmentally friendly due to the less fouling it causes as well as the significant reduction in gas consumption and combustion-related emissions (Cappato et al. 2017).

Ohmic treatment has been successfully applied in pasteurization and concentration of fruit juices and pulps (Sarkis et al. 2019; Norouzi et al. 2021). However, the effect of ohmic and conventional treatment on the bioactive compounds of pulps, mainly from tropical fruits such as guava, were not compared and widely investigated.

Guava has been considered a superfruit with a rich variety of phenolic compounds, high content of vitamin C and carotenoids (Lima et al., 2019). Therefore, it is relevant to investigate the effect of unconventional technology such as ohmic treatment on the degradation kinetics of these compounds. The results will be useful to obtain information on thermal stability of these bioactive compounds aiming preservation and retention in the matrix that will benefit consumers and processors of tropical fruits that is still little known (Ordóñez-Santos and Martínez-Girón, 2020; Salari and Jafari 2020). Considering these facts, the objective of this study was to compare the effect of ohmic and conventional heat treatments in guava pulps on the degradation kinetics of ascorbic acid, carotenoids and color.

Material and methods

Guava pulp processing

The experiments were conducted from February to June 2020. Guava cultivar Pedro Sato was purchased from a plantation located in the municipality of Ibiporã (state of Paraná, Brazil, 23°16'10''S, 51°2'37''W), and guavas with peel at the beginning of development of yellow color were used. Guavas were selected, washed in water, sanitized with sodium hypochlorite solution (100 ppm), extracted with laboratorial electric pulper (Macanuda, Brazil), and stored in 400 mL polyethylene bags. One part of the fresh pulp was used for physical and chemical characterization (pH, total soluble solids, total titratable acidity, ascorbic acid content and total carotenoids) and the other part of the pulp was frozen at −18°C.

Conventional and ohmic heat treatments of guava pulp

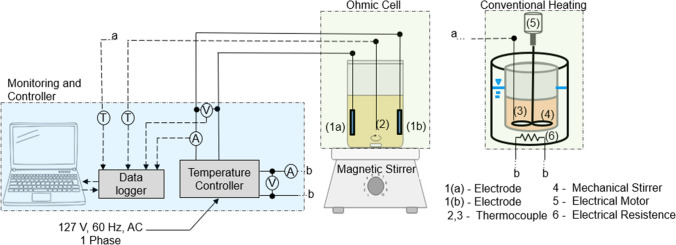

The conventional heating system (Fig. 1) consisted of a 600 mL glass container with a hermetic lid containing 3 holes, as follows: (1) to couple the calibrated type K thermocouple; (2) to insert the mechanical stirrer and (3) to collect the sample. The glass vessel was partially immersed in a temperature-controlled water bath for heating the samples. The heat treatment was provided by means of an electrical resistance controlled by an analog digital device. The device with a data acquisition system monitored and recorded data on electrical consumption and average temperature of the sample as a function of time.

Figure 1:

Experimental setup of ohmic and conventional heating (V = voltage transducer, A = current transducer and T =temperature sensor).

The ohmic heating system (Fig. 1) consisted of a heating system in a 600 mL glass container with hermetic lid and four specific inlets, as follows: (1) to couple the type K thermocouple fitted in the cylindrical glass tube with thermal paste to eliminate air gaps and to prevent interference with the electrical field calibrated to measure the temperature that was recorded to a computer data acquisition system; (2 and 3) two inputs for the electrodes and (4) one output for sample collection. The two electrodes were rectangular platinum (2 x 3 cm) and approximately 6 cm. The ohmic cell was placed under a magnetic stirrer (Ika, C-MAG HS7, Germany) to promote stirring of the pulp during the heat treatment. The data acquisition system monitored and recorded electrical consumption and heat treatment temperature as a function of time, allowing for the assessment of thermal efficiency. An alternating voltage of 21.2 V/m and an average frequency of 60Hz was used. All experiments using conventional or ohmic heating were conducted in duplicate.

Guava pulp heating profile and energy efficiency of conventional and ohmic treatments

The heating dynamic of the conventional and ohmic treatments of guava pulp at 60, 70 and 80°C was evaluated. The energy efficiency (, %) of electricity-to-heat conversion of the two heating treatments was calculated using Equation 1:

| 1 |

where η is the energy efficiency of converting electricity to heat; mg is the guava pulp mass; Cp is the specific heat of the guava pulp at constant pressure; V is the electrical voltage applied to both heat treatments and i represents the electrical current.

Determination of kinetic and thermodynamic parameters of ascorbic acid degradation in guava pulp

The results of ascorbic acid were fitted to kinetics models of zero order (Equation 2), first order (Equation 3), second order (Equation 4) and Weibull (Equation 5).

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

Where, C is the ascorbic acid concentration, C0 is the initial ascorbic acid concentration, k is the reaction rate constant, and t is the time.

To choose the best kinetic model, physical and statistical criteria were considered. The statistical criteria are the coefficient of determination (R2), the chi-square (χ2), and the Akaike information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), since the experiments were done in duplicate the maximum percentage of explainable variation R2máx was also calculated.

The decimal reduction time (D) and half-life (t1/2) of the heat-treated guava pulps were calculated with Eqs. 6 and 7, respectively:

| 6 |

| 7 |

Thermodynamic parameters such as activation energy (Ea), activation enthalpy (ΔH), Gibbs free energy (ΔG) and entropy change (ΔS) of the thermal degradation of ascorbic acid from guava pulp were obtained according to Eqs. 8, 9, 10 and 11:

| 8 |

| 9 |

| 10 |

| 11 |

Where, k0 corresponds to the frequency factor (min−1), R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J mol−1K-1), T is the temperature in K, h is the Plank constant (6.6262×10−34 J s−1), and kB is the Boltzmann constant (1.3806×1023J K−1).

Analytical methods

The pH was measured with calibrated potentiometer (Hanna Instruments, HI 2221, least count 0.02, Brazil), the total soluble solids content was determined by refractometry (Hanna Instruments, least count 0.1oBrix, Brazil), and the titratable acidity content was determined by titrating the sample with 0.1 mol/L sodium hydroxide and phenolphthalein indicator (AOAC Method, 2016).

To extract ascorbic acid, 4.0 g guava pulp and 50 mL 2% oxalic acid solution (w/v) were mixed, and then 10 mL extract was titrated with 2,6 dichlorophenolindophenol (0.02%, w/v) (AOAC Method, 2016).

The determination of total carotenoid content was performed according to Lee and Castle, (2001) with minor modifications. For extraction, Falcon tube containing 2.5 g of guava pulp and 10 mL of solution (5 mL hexane, 2.5 mL methanol and 2.5 mL acetone) was vortexed (Phoenix, AP 59, Brazil) for 1 min and centrifuged for 10 min. The supernatant was collected and the absorbance was read at 450 nm in a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Femto, Brazil).

The color parameters a*, b* and L* were obtained using a colorimeter (Konica Minolta, CR-400), with D65 illuminant (daylight) and viewing angle of 10°. The chroma hue angle (h°), the chromaticity or color saturation (C*) and the global color difference (ΔE*) were calculated according to the equations:

| 12 |

| 13 |

| 14 |

Statistical analysis

Two independent experiments, replicates, were carried out for each temperature studied during ohmic heating and also for the conventional heating. The results were fitted to the kinetics models by nonlinear estimation using Statistica 7.0 software for Windows (Statsoft, Tulsa, OK, USA). Statistical significance was evaluated by Tukey’s test at 5% significance level (p<0.05).

Results and discussion

Physical and chemical characterization of guava pulp

The properties of the guava pulp at room temperature before heating are listed in Table 1. The total soluble solids content of 10.10 ± 0.06°Brix was close to that reported by Shrivastava et al. (2018), whose values ranged from 10.71 to 12.34°Brix. Values of pH 3.95 ± 0.05 and total acidity 0.333 ± 0.017 are in agreement with reports in the literature (Evangelista and Vieites 2015; Formiga et. al. 2019).

Table 1:

Properties of the guava pulp used for ohmic and conventional heating.

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Total soluble solids (ºBrix) | 10.10 ± 0.06 |

| pH | 3.98 ± 0.05 |

| Total titratable acidity (%) | 0.333 ± 0.017 |

| Ascorbic acid (mg 100 g−1) | 230.00 ± 0.39 |

| Carotenoids (μg 100 g−1) | 500.27 ± 0.257 |

| Color: L* | 41.67 ± 0.05 |

| a* | 13.08 ± 0.08 |

| b* | 12.06 ± 0.05 |

The ascorbic acid content of the guava pulp was 230.00 ± 0.39 mg 100 g-1 is within the range reported by Yousaf et al. (2020), who evaluated the influence of eight guava cultivars and observed a significant difference between the cultivars for the ascorbic acid content, 222.26-289.43 mg/100 g. Mahawar et al. (2018) also observed content of fresh guava pulp was 245.5 mg/100g. Nevertheless, the carotenoid content of guava pulp of 500.27 ± 0.257 μg 100 g−1 was lower than reported by Menezes et al. (2016), whose value was 608.2 ± 19.8 μg/100 g−1.

Profile of guava pulp heating treatments

The profile of the conventional and ohmic thermal treatments at 60, 70 and 80°C with the respective setpoints is illustrated in Fig. 2 (a and b). For both treatments, the initial temperature of the samples was close to 12 °C and the profile was markedly different. The profiles represent the heating dynamics of guava pulp in relation to the two heating treatments.

Figure 2:

a Temperature profile of guava pulp during conventional. b Temperature profile of guava pulp during ohmic heating. c Electricity consumption at 60 °C for the conventional (CV-A and CV-B) and ohmic (OH-A and OH-B) treatments. d Thermal degradation kinetics of ascorbic acid from guava pulp under conventional (CV) and e ohmic (OH) heating at 60, 70 and 80 °C for 110 min. The lines represent the predicted values for ascorbic acid degradation using first order model.

During conventional treatment, the average time required to reach temperatures of 60, 70 and 80 ºC were 6.3, 20.3, and 44.6 min, respectively. While for the ohmic treatment, the time to reach the respective temperatures was significantly shorter, 6.2, 6.9, and 8.2 min. For the lowest setpoint temperature, 60 °C, the two heating times were close, probably due to the lower power requirement. Nevertheless, in the conventional treatment, the time to reach the setpoint temperature was longer due to the higher thermal inertia of the system, in which it is necessary to raise the temperature of the water mass and transfer heat between the contact surfaces of glass with water and pulp. Further, there is heat loss to the environment through the surface of the water compartment and thermal efficiency from the electrical resistance. On the other hand, in the ohmic treatment, the heating system was almost immediate, since in this system the electric resistance of the pulp itself is used, which generates heat for heating and does not require additional uses, such as heating water that occurs in the conventional system or thermal contact surfaces. Consequently, the pulp fouling problems occurring in the conventional treatment are eliminated.

In the conventional treatment, the average heating rate was 0.16°C/s, 0.06°C/s and 0.03°C/s, and it was observed that the heating rate at the highest temperature (80 °C) reduced by 80% compared to the lowest temperature (60 °C). For the ohmic treatment, the heating rate was practically constant and equal to 0.16 °C/s, 0.17°C/s and 0.16°C/s.

The history of electrical consumption of the two heating treatments at a temperature of 60°C (Fig. 2) evidenced the advantage of using ohmic heating in relation to the conventional one. The total average electrical consumption of heating by using the conventional system was 690 Wh, significantly higher than that of the ohmic system, which was 46 Wh, that is, there was an energy consumption saving of 93%. Also the energy efficiencies of electricity to heat conversion, of the conventional and ohmic treatments at 60 °C (Fig. 2) were 2.62% and 40.93%, respectively. These results confirmed that in terms of energy consumption, the heating of ohmic treatment was advantageous over the conventional treatment.

Kinetics of thermal degradation of ascorbic acid from guava pulp

Results in Table 2 indicate that the zero-order and second-order mathematical models showed lower values of R2 and higher values of X2, AIC and BIC when compared to the other models used. For these reasons, these models were rejected. Both the first-order model and the Weibull model had good fits, presenting close values of R2 and X2, however the AIC and BIC indices represent a trade-off between the goodness of fit of the model and the simplicity of the model, were lower for the first-order model. Thus, in the present study, the first order model was selected to fit the results for the two treatments, both for ohmic and conventional heating, due to mathematical simplicity and also, it is more parsimonious than the Weibull model, that is, the model involves a smaller number of parameters to be estimated and explained well the behavior of the response variable. The first order model has also been widely used to evaluate the thermal degradation of bioactive compounds from different juices, such as: orange (Vikram et al. 2005), pomegranate (Alighourchi and Barzegar 2009) and acerola pulp (Mercali et al. 2012), and whey acerola-flavored drink (Cappato et al. 2018).

Table 2:

Statistical parameters of evaluated kinetic models for ascorbic acid content during ohmic and conventional heating.

| Model | Statistical Parameters | Ohmic Heating | Conventional Heating | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temp. (°C) | 60 | 70 | 80 | 60 | 70 | 80 | |

| R2max | 0.9195 | 0.9956 | 0.9981 | 0.9192 | 0.9011 | 0.8559 | |

| zero order | R2 | 0.890 | 0.923 | 0.754 | 0.862 | 0.838 | 0.640 |

| χ2 | 0.0100 | 0.0090 | 0.0326 | 0.0010 | 0.0020 | 0.0110 | |

| AIC | 46.360 | 31.542 | 31.395 | 31.425 | 31.438 | 31.571 | |

| BIC | 47.51 | 32.315 | 32.668 | 32.197 | 32.210 | 31.343 | |

| first order | R2 | 0.914 | 0.980 | 0.997 | 0.876 | 0.855 | 0.670 |

| χ2 | 0.0073 | 0.0024 | 0.0004 | 0.0010 | 0.0019 | 0.0101 | |

| AIC | 46.227 | 31.442 | 31.412 | 32.423 | 31.435 | 31.557 | |

| BIC | 47.550 | 32.215 | 32.185 | 32.195 | 32.207 | 32.320 | |

| second order | R2 | 0.880 | 0.935 | 0.960 | 0.886 | 0.865 | 0.690 |

| χ2 | 0.0100 | 0.0076 | 0.0053 | 0.0010 | 0.0020 | 0.0090 | |

| AIC | 46.340 | 31.521 | 31.485 | 31.422 | 31.433 | 31.548 | |

| BIC | 47.570 | 32.293 | 32.258 | 32.194 | 32.205 | 32.330 | |

| Weibull | R2 | 0.920 | 0.982 | 0.997 | 0.898 | 0.892 | 0.769 |

| χ2 | 0.0100 | 0.0030 | 0.0004 | 0.0010 | 0.0015 | 0.0076 | |

| AIC | 48.270 | 33.442 | 33.411 | 33.420 | 33.428 | 33.512 | |

| BIC | 50.630 | 34.987 | 34.956 | 34.965 | 34.973 | 35.057 | |

R2 (Coefficient of determination), X2 (Chi-squared), AIC (Akaike information criterion) and BIC (Bayesian information criterion).

Figure 2c, d illustrates the fit of the first-order model for experimental data on the thermal degradation of ascorbic acid in guava pulp under conventional and ohmic heating at 60, 70 and 80 °C for 110 minutes. According to Figure 2 (c, d), the temperature of both treatments significantly influenced the degradation of ascorbic acid in guava pulp. In conventional heating at 60, 70 and 80 °C for 110 minutes, the mean dimensionless concentration of ascorbic acid reduced 27, 35 and 57%, respectively. While in ohmic heating and at the same temperatures and time, the reduction was 69, 89 and 95%, respectively. These results indicated that the degradation of ascorbic acid in guava pulp was greater when applying ohmic heating than conventional heating.

Values of k (Table 3) of the first order kinetic model of the thermal degradation of guava pulp ascorbic acid under conventional and ohmic heating at 60 °C and 80 °C ranged from 3.327 × 10−3 to 6.788 × 10−3 min−1 and 12.278 × 10−3 to 30.259 x 10−3 min−1, respectively. This reaction rate constant (k) has not yet been described in the literature. Although similar k values were reported by Sarkis et al. (2019), who used the same kinetic model to evaluate the thermal degradation of blackberry pulp anthocyanins under conventional heating at 70, 75, 80 and 90 °C, for 90 min. The k value (Table 3) in ohmic heating at 60 °C was lower (p<0.05) than at 70 and 80 °C, while in conventional heating at 60 and 70 °C, the k value was similar and lower (p<0.05) than at 80 °C. Nevertheless, in conventional and ohmic heating at 80 °C, the value of k was higher (p<0.05) than at 60 and 70 °C, however, in ohmic heating the order of magnitude was 4.45 times greater than in conventional heating. However, Mercali et al. (2014) found no significant differences (p>0.05) in k values when using conventional and ohmic heating to assess acerola pulp vitamin C degradation. This lack of difference in k values may possibly be associated with the use of different conditions and type, temperature, time and electric field of heating. Moreover, it is noteworthy that in this study the heating termed as ohmic was performed using 30 V and water at 75 °C in a jacketed system simultaneously, that is, the largest portion responsible for heating the samples was performed by conventional treatment and being the electric field responsible for the rise of only 10 °C.

Table 3:

First order kinetic model and thermodynamic parameters of thermal degradation of ascorbic acid in guava pulp under conventional and ohmic heating.

| Temp. (°C) | Conventional | Ohmic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60 | 70 | 80 | 60 | 70 | 80 | |

| k 10 −3 (min−1) | 3.327 ± 0.022d | 3.860 ± 0.025d | 6.788 ± 0.074e | 12.278 ± 0.796a | 17.855 ± 0.822b | 30.259 ± 0.66c |

| D(min) | 692.1 | 596.6 | 339.2 | 187.5 | 129.0 | 76.1 |

| t1/2(min) | 208.4 | 179.6 | 102.1 | 56.4 | 38.8 | 22.9 |

| Ea (kJ/ mol) | 40.28 ± 11.5 | 46.72 ± 5.06 | ||||

| ΔH (kJ/ mol) | 37.51 | 37.43 | 37.35 | 43.95 | 43.87 | 43.78 |

| ΔG (kJ/mol) | 65.53 | 66.98 | 67.19 | 61.91 | 62.61 | 62.81 |

| ΔS (kJ/ mol K) | −0.084 | −0.086 | −0.085 | −0.054 | −0.055 | −0.054 |

Results are the mean values of two independent experiments (mean ± standard error); means in the same column followed by different lowercase letters are significantly different (p<0.05).

The degradation of ascorbic acid in the ohmic treatment may also have occurred due to non-thermal effects, such as the reactions of water electrolysis and electrode corrosion, as described by Assiry et al. (2003). In water electrolysis, hydrogen is released at the cathode and oxygen at the anode, and when the voltage is alternating, both products are released at each electrode. Thus, the oxygen generated by water electrolysis can cause further oxidation of the ascorbic acid. Also, according to Mercali et al. (2012), in ohmic heating at high temperatures, water boils and bubbles form around the electrodes, possibly due to oxidation and reduction reactions or due to the dissociation of weak acids from the pulp.

The decimal reduction time (D) and the half-life (t1/2) represent the time required to degrade 90 and 50% ascorbic acid in the heat-treated guava pulps, respectively. In conventional and ohmic heating, the values of D and t1/2 ranged from 339.2 to 692.1 min and 76.1 to 187.54 min and from 102.1 to 208.4 min and from 22.9 to 56.46 min, respectively. For both heat treatments, values of D and t1/2 decreased with increasing temperature, indicating that temperature influenced the degradation of ascorbic acid in guava pulp. Values of D and t1/2 for both treatments and at the same temperature were lower for ohmic heating, indicating a greater thermal sensitivity for ascorbic acid degradation, which was also confirmed by the values of k (Table 3). These results were different from those described by Mercali et al. (2013), who evaluated the thermal degradation of ascorbic acid in acerola pulp. However, similar D and t1/2 values were described by Vikran et al. (2005), who evaluated the thermal degradation of ascorbic acid in orange juice under ohmic heating.

A comparative evaluation of the application of ohmic heating in the thermal degradation of ascorbic acid in guava pulp has been difficult and there is not much information in the literature. In addition, there is no uniformity among authors regarding the form of heating promotion carried out with ohmic heating, in which some authors use different forms and it is inefficient to affirm and correlate studies, although in some situations the temperature can be controlled with variation in the electric field (Vikram et al. 2005). There are other situations in which the electric field is constant and the temperature can be controlled with refrigerant fluid through a jacketed circuit (Mercali et al. 2015). Other systems can promote part of the heating through hot fluids and raise the temperature by 5 to 10 degrees with the application of an electric field (Brochier et al. 2018; Mercali et al. 2012).

Thermodynamic parameters of the thermal degradation of guava pulp ascorbic acid with conventional and ohmic heating

In conventional and ohmic heating at 60 to 80 °C for thermal degradation of ascorbic acid in guava pulp, the activation energy (Ea) was respectively 40.28 ± 11.5 kJ/mol and 46.72 ± 5.06 kJ/mol (Table 3). Values of Ea described by Vikram et al. (2005) on nutrient degradation of orange juice was similar to the present study, being respectively 39.84 kJ/mol and 47.3 kJ/mol for conventional and ohmic heating at 50 to 90 °C, for 15 minutes. Still, the same authors described that the ohmic heating had higher Ea due to the high dielectric properties of orange juice and instantaneous heat generation caused by the passage of electric current. For thermal degradation of ascorbic acid from tomato juice with conventional heating from 70 to 90 °C, Ordóñez-Santos and Martínez-Girón, (2020) obtained an Ea of 41.27 kJ mol−1. Castro et al. (2004) for strawberry pulp and heating temperature between 60 and 97 °C obtained an Ea of 21.05 kJ mol-1 for ohmic heating, and Dhakal et al. (2018) for conventional heating also reported a lower value for pineapple juice compared to our result, Ea of 22.02 kJ mol-1, with a temperature range between 75 and 95 °C. The highest Ea value obtained for the ohmic treatment indicates that a small variation in temperature is enough to degrade the ascorbic acid in guava pulp.

According to Vikram et al. (2005), the activation enthalpy (ΔH) is a measure of energy barrier that must be overcome by reacting molecules and is related to the strength of the bonds, which are broken and made in the formation of the transition state from the reactants. The ΔH for thermal degradation of guava pulp ascorbic acid for conventional and ohmic heating at 60, 70 and 80°C were respectively similar (Table 3). The ΔH for thermal degradation of orange juice ascorbic acid with conventional and ohmic heating was similar to the present study and equal to 37.03 kJ mol−1 and 44.35 kJ mol−1, respectively (Vikram et al. 2005).

Gibbs free energy (ΔG) indicates the driving force of a chemical reaction and determines the spontaneity of the reaction. The ΔG for thermal degradation of guava pulp ascorbic acid for conventional and ohmic heating at 60, 70 and 80 °C was respectively 65.53; 66.98 and 67.19 kJ mol−1 and 61.91; 62.61 and 62.81 kJ mol−1 (Table 3). For both heat treatments, the ΔG was positive and therefore indicated that the degradation of ascorbic acid was a non-spontaneous reaction.

Entropy change (ΔS) indicates the difference in the enthalpy of activation (ΔH) and Gibbs free energy (ΔG) in relation to the transition temperature. The ΔS for thermal degradation of guava pulp ascorbic acid for conventional and ohmic heating at 60, 70 and 80 °C were respectively similar and negative (Table 3). Negative values indicated that the complex activated in the transition state had a more ordered or more rigid structure than the reactants in the ground state. Furthermore, close ΔS values for both heating technologies at all temperatures indicated that the reactivities and reaction times were similar.

Carotenoid content after conventional and ohmic heating

The temperature increases from 60 to 80 °C of the conventional and ohmic heating of the guava pulp reduced the content of carotenoids (Table 4). It is observed that the carotenoid content retention was greater for ohmic heating, since in this process the setpoint temperature is reached in less time. Carotenoids have strongly unsaturated structures and are susceptible to oxidation, isomerization and other chemical modifications, and can also be degraded during processing due to heat treatment. In fruit, carotenoids are found in different plastids, mainly in chloroplasts. It is possible that with the ohmic heating of guava pulp, it caused a greater cell disruption and, consequently, there was greater release of carotenoids. After ohmic processing of whey acerola-flavored drink, especially with high frequencies (1,000 Hz) and voltages (80 V), Cappato et al. (2018) observed that there was greater cell disruption. Heat treatment at 70 °C for up to 300 seconds in cajá pulp (Sales and Waughon 2013) reduced the content of total carotenoids. However, after heating at 80 °C, there was an increase in carotenoid content due to the release of pigments from the breakdown of the carotene-protein bond and disruption of the cell matrix. However, at a higher temperature, that is, at 90 °C, some pigments were degraded and, consequently, the content of total carotenoids was reduced.

Table 4:

Retention of total carotenoid and color parameters in guava pulp after conventional and ohmic heat treatment

| Treatment | Carotenoid retention (%) | ΔE | C* | h° |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fresh | – | – | 17.82 ± 0.05a | 0.88 ± 0.01a |

| CV 60 °C | 110.00 ± 10.00 | 2.20 ± 0.18ª | 18.06 ± 0.35ª | 0.82 ± 0.08ª |

| OH 60 °C | 123.77 ± 10.34 | 2.51 ± 0.46ª | 17.19 ± 0.16ª | 0.90 ± 0.04ª |

| CV 70 °C | 89.02 ± 27.73 | 3.30 ± 1.16ª | 16.56 ± 1.44ª | 0.88 ± 0.05ª |

| OH 70 °C | 100.49 ± 33.72 | 2.06 ± 1.16ª | 19.33 ± 1.97ª | 0.96 ± 0.09ª |

| CV 80 °C | 64.25 ± 4.93 | 2.75 ± 1.11ª | 18.54 ± 0.28ª | 0.88 ± 0.03ª |

| OH 80 °C | 79.23 ± 11.25 | 4.42± 0.54a | 16.71 ± 0.66ª | 0.94 ± 0.02ª |

aDifferent letters in the same column indicate significant differences (p>0.05) by Tukey’s test.

Evaluation of guava pulp color parameters after conventional and ohmic heating

The color parameters chrome hue (h°), chromaticity or color saturation (C*) and overall color difference (ΔE) of the guava pulp after conventional and ohmic heat treatment at 60, 70 and 80 °C are listed in Table 4. Color parameters of the guava pulp after heat treatments at the respective temperatures did not show significant differences (p>0.05). In addition, fresh guava pulps also did not show differences in the parameters C* and h° in relation to pulps heated by both treatments and temperatures. Different results were verified in some fruit-based foods such as acerola pulp (Mercali et al. 2014), and sugarcane juice (Brochier et al. 2018) showed significant changes in color after heat treatment. A possible explanation for these contradictory results of color parameters may be associated, according to Brochier et al. (2018), with the ohmic heating of different food matrices, in which there are differences in voltage gradients, waveforms and compounds with different activities.

Conclusions

The ohmic technology compared to conventional heat treatment resulted in faster heating of guava pulp. Considering the energetic context, the ohmic heating presented an average energy consumption saving of 93% compared to conventional heating, an advantage that reiterates the use of ohmic heating in food processing. The ascorbic acid degradation was well described by the first-order model, and it was dependent on temperature, showing heat sensibility, independent of the type of heat treatment. On the other hand, there was no change in guava pulp color during conventional and ohmic treatments. The carotenoid content retention was greater for ohmic heating, once, in this process, the setpoint temperature is reached in less time, in addition, it is possible that the electric field caused greater cell disruption, increasing the release of carotenoids. Overall, the comparative study between conventional and ohmic heating of guava pulp indicated that, under the conditions explored, there is a trade-off between the degradation of ascorbic acid and energy savings, while for the maintenance of color and carotenoid content, the results provided by ohmic heating are promising.

Abbreviations

- AIC

Akaike information criterion

- AOAC

Association of official analytical chemists

- BIC

Bayesian information criterion

- C

Concentration

- C*

Chroma

- C0

Initial concentration

- cm

Centimeter

- Cp

Specific heat at constant pressure

- CV

Conventional

- D

Decimal reduction time

- Ea

Activation energy

- g

Gram

- h

Plank constant

- h*

Hue angle

- Hz

Hertz

- i

Electrical current

- J

Joule

- k

Reaction rate constant

- K

Kelvin

- k0

Frequency factor

- kB

Boltzmann constant

- L

Liter

- m

Meter

- mg

Guava pulp mass

- min

Minutes

- mL

Milliliter

- Mt

Megatonne

- n

Shape factor

- OH

Ohmic

- pH

Potential of hydrogen

- ppm

Parts per million

- R

Universal gas constant

- R2

Coefficient of determination

- t

Time

- T

Temperature

- t1/2

Half-life time

- V

Volt

- v

Volume

- w

Weight

- Wh

Watt hour

- ΔE*

Global color difference

- ΔG

Gibbs free energy

- ΔH

Enthalpy

- ΔS

Entropy change

- μg

Microgram

- χ2

Chi-square

- η

Energy efficiency

Author’s contributions

VCG carried out the kinetic ascorbic acid and carotenoid and color experimental tests, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. GRS carried out the statistical analyses and made the equipment assembly and adjustment, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. MAS carried out the kinetic and carotenoid and color experimental tests, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors acknowledge funding received from the CNPq (Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico, Brasil), CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior, Brasil), and UTFPR (Universidade Tecnológica Federal do Paraná).

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript.

Code availability

Not Applicable

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors certify that there is no actual or potential conflict of interest in relation to this article.

Ethics approval

Not Applicable

Consent to participate

Not Applicable

Consent for publication

Not Applicable

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Vanessa Cipriani Giuliangeli, Email: vacipriani@gmail.com.

Gylles Ricardo Ströher, Email: gylles@utfpr.edu.br.

Marianne Ayumi Shirai, Email: marianneshirai@utfpr.edu.br.

References

- Alighourchi H, Barzegar M. Some physicochemical characteristics and degradation kinetic of anthocyanin of reconstituted pomegranate juice during storage. J Food Eng. 2009;90:179–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2008.06.019. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gamelin FX, Baquet G, Berthoin S, Thevenet D, Nourry C, Nottin S, Bosquet L. Effect of high intensity intermittent training on heart rate variability in prepubescent children. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2009;105:731–738. doi: 10.1007/s00421-008-0955-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Assiry A, Sastry SK, Samaranayake C. Degradation kinetics of ascorbic acid during ohmic heating with stainless steel electrodes. J Appl Electrochem. 2003;33:187–196. doi: 10.1023/A:1024076721332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibwe B, Mahawar MK, Jalgaonkar K, Meena VS, Kadam DM. Mass modeling of guava (cv. Allahabad safeda) fruit with selected dimensional attributes: regression analysis approach. J Food Process Eng. 2022;45:1–11. doi: 10.1111/jfpe.13978. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brochier B, Mercali GD, Marczak LDF. Effect of ohmic heating parameters on peroxidase inactivation, phenolic compounds degradation and color changes of sugarcane juice. Food Bioprod Process. 2018;111:62–71. doi: 10.1016/j.fbp.2018.07.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cappato LP, Ferreira MVS, Guimaraes JT, Portela JB, Costa ALR, Freitas MQ, Cunha RL, Oliveira CAF, Mercali GD, Marzack LDF, Cruz AG. Ohmic heating in dairy processing: Relevant aspects for safety and quality. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2017;62:104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2017.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cappato LP, Ferreira MVS, Pires RPS, Cavalcanti RN, Bisaggio RC, Freitas MQ, Silva MC, Cruz AG. Whey acerola-flavoured drink submitted ohmic heating processing: Is there an optimal combination of the operational parameters? Food Chem. 2018;245:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro I, Teixeira JA, Salengke S, Sastry SK, Vicente AA. Ohmic heating of strawberry products: electrical conductivity measurements and ascorbic acid degradation kinetics. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2004;5:27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2003.11.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chiveu J, Naumann M, Kehlenbeck K, Pawelzik E. Variation in fruit chemical and mineral composition of Kenyan guava (Psidium guajava L.): Inferences from climatic conditions, and fruit morphological traits. J Appl Bot Food Qual. 2019;92:151–159. doi: 10.5073/JABFQ.2019.092.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dhakal S, Balasubramaniam VM, Ayvaz H, Rodriguez-Saona LE. Kinetic modeling of ascorbic acid degradation of pineapple juice subjected to combined pressure-thermal treatment. J Food Eng. 2018;224:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2017.12.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Evangelista RM, Vieites RL. Avaliação da qualidade de polpa de goiaba congelada, comercializada na cidade de São Paulo. Segur Aliment Nutr. 2015;13:76–81. doi: 10.20396/san.v13i2.1834. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fadavi A, Yousefi S, Darvishi H, Mirsaeedghazi H. Comparative study of ohmic vacuum, ohmic, and conventional-vacuum heating methods on the quality of tomato concentrate. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2018;47:225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2018.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- FAO (2022) Major tropical fruits: preliminary results 2021. Rome. https://www.fao.org/3/cb9412en/cb9412en.pdf. Accessed 03 May 2022

- Formiga AS, Pinsetta JS, Pereira EM, Cordeiro INF, Ben-HurMattiuz E. Use of edible coatings based on hydroxypropyl methylcellulose and beeswax in the conservation of red guava ‘Pedro Sato’. Food Chem. 2019;290:144–51. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2019.03.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamieson S, Wallace CE, Das N, Bhattacharyya P, Bishayee A. Guava (Psidium guajava L.): a glorious plant with cancer preventive and therapeutic potential. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2021 doi: 10.1080/10408398.2021.1945531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HS, Castle WS. Seasonal changes of carotenoid pigments and color in Hamlin, Earlygold, and Budd Blood orange juices. J Agric Food Chem. 2001;49:877–882. doi: 10.1021/jf000654r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lima RS, Ferreira SRS, Vitali L, Block JM. May the superfruit red guava and its processing waste be a potential ingredient in functional foods? Food Res Int. 2019;115:451–459. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2018.10.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahawar MK, Jalgaonkar K, Bibwe B, Kulkarni T, Bhushan B, Meena VS. Optimization of mixed aonla-guava fruit bar using response surface methodology. Nutr Food Sci. 2018;48:621–630. doi: 10.1108/NFS-09-2017-0189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Menezes PE, Dornelles LL, Fogaça AO, Boligon AA, Athayde ML, Bertagnolli SMM. Centesimal composition, bioactive compounds, antioxidant activity and phenolic characterization of guava pulp. Discip Scien Sau. 2016;17:205–217. [Google Scholar]

- Mercali GD, Gurak PD, Schmitz F, Marczak LDF. Evaluation of non-thermal effects of electricity on anthocyanin degradation during ohmic heating of jaboticaba (Myrciariacauliflora) juice. Food Chem. 2015;171:200–205. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercali GD, Jaeschke DP, Tessaro IC, Marczak LDF. Degradation kinetics of anthocyanins in acerola pulp: Comparison between ohmic and conventional heat treatment. Food Chem. 2013;136:853–857. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercali GD, Jaeschke DP, Tessaro IC, Marczak LDF. Study of vitamin C degradation in acerola pulp during ohmic and conventional heat treatment. LWT - Food Sci Technol. 2012;47:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2011.12.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mercali GD, Schwartz S, Marczak LDF, Tessaro IC, Sastry S. Ascorbic acid degradation and color changes in acerola pulp during ohmic heating: effect of electric field frequency. J Food Eng. 2014;123:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norouzi S, Fadavi A, Darvishi H. The ohmic and conventional heating methods in concentration of sour cherry juice: quality and engineering factors. J Food Eng. 2021;291:110242. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2020.110242. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ordóñez-Santos LE, Martínez-Girón J. Thermal degradation kinetics of carotenoids, vitamin C and provitamin A in tree tomato juice. Int J Food Sci Technol. 2020;55:201–210. doi: 10.1111/ijfs.14263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Salari S, Jafari SM. The influence of ohmic heating on degradation of food bioactive ingredients. Food Eng Rev. 2020;12:191–208. doi: 10.1007/s12393-020-09217-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sales A, Waughon TGM. Influence of processing on the bioactive compound content in murici and hog plum onetefruits. Revista Agrarian. 2013;6:7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Sarkis JR, Jaeschke DP, Mercali GD, Tessaro IC, Marczak LDF. Degradation kinetics of anthocyanins in blackberry pulp during ohmic and conventional heating. Int Food Res J. 2019;26:87–97. [Google Scholar]

- Shrivastava DC, Singh NK, Jhade RK. Effect of rejuvenation on biochemical properties of fruit and fruit pulp during different storage period in guava (Psidium Guajava) CV Allahabad Safeda. Int J of Chem Stud. 2018;6:963–966. doi: 10.26438/ijsrcs. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vikram VB, Ramesh MN, Prapulla SG. Thermal degradation kinetics of nutrients in orange juice heated by electromagnetic and conventional methods. J Food Eng. 2005;69:31–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2004.07.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yousaf AA, Abbasi KS, Ahmad A, Hassan I, Sohail A, Qayyum A, Akram MA. Physico-chemical and nutraceutical characterization of selected indigenous guava (Psidium Guajava L.) Cultivars. Food Sci and Tech. 2020;41:47–58. doi: 10.1590/fst.35319. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript.

Not Applicable