Abstract

The partial loss of liver due to liver transplantation or acute liver failure induces rapid liver regeneration. Recently, we reported that the selective inhibition of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (Ido) 1 promotes early liver regeneration. However, the role of Ido2 in liver regeneration remains unclear. Wild-type (WT) and Ido2-deficient (Ido2-KO) mice were subjected to 70% partial hepatectomy (PHx). Hepatocyte growth was measured using immunostaining. The mRNA expression of inflammatory cytokines and production of kynurenine in intrahepatic mononuclear cells (MNCs) were analyzed using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR and high-performance liquid chromatography. The activation of NF-κB was determined by both immunocytochemistry and western blotting analysis. The ratio of liver to body weight and the frequency of proliferation cells after PHx were significantly higher in Ido2-KO mice compared with in WT mice. The expression of IL-6 and TNF-α in MNCs were transiently increased in Ido2-KO mice. The nuclear transport of NF-κB was significantly higher in peritoneal macrophages of Ido2-KO mice compared with WT mice. These results suggested that Ido2 deficiency resulted in transiently increased production of inflammatory cytokines through the activation of NF-kB, thereby promoting liver regeneration. Therefore, the regulation of Ido2 expression in MNCs may play a therapeutic role in liver regeneration under injury and disease conditions.

Keywords: indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 2; liver regeneration; partial hepatectomy; inflammation; nuclear factor-κB

Introduction

The liver plays a central role in metabolic homeostasis (1). Although hepatic metabolism is decreased by acute liver injuries, such as hepatitis and transplantation, this function is restored by liver regeneration based on the rapid proliferation of hepatocytes (2). The 70% partial hepatectomy (PHx) model has been widely used to examine the mechanisms of liver regeneration, repair after tissue injury, and hepatocytes cell cycle dynamics in vivo (3). Particularly, nonparenchymal liver cells are known to promote liver regeneration by the production of inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), via the TLR/MyD88/NF-kB axis (4,5). In addition, the TLR/MyD88/NF-kB pathway is activated by a gut-derived lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and damage-associated molecular pattern in a partial hepatectomy (PHx) (6). Furthermore, heat-shock proteins, which are endogenous TLR ligands, are involved in liver regeneration after PHx (7).

Liver regeneration is promoted not only by inflammatory cytokines but also by other factors, such as tryptophan (Trp) metabolites. The expression of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (Ido) 1, which catalyzes the oxidation of Trp to kynurenine (Kyn) in the first step of the Kyn pathway (8,9), is induced in various immune cells and tissues under inflammatory conditions. Ido1-derived Kyn regulates various immune responses through its interaction with the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (Ahr), which inhibits NF-κB activation (10,11). We recently reported that inhibition of Ido1 accelerates early liver regeneration after PHx by increasing the expression of cell cycle and pro-inflammatory cytokine genes (12). Furthermore, Kyn treatment suppressed liver regeneration in WT mice. In contrast, Ido2, an isozyme of Ido1, is constitutively expressed in the liver, placenta, central nervous system, and macrophages, and its expression is regulated by various inflammatory mediators, including interferon-γ, IL-10, and prostaglandin E2 (13). Constitutive expression of Ido2 is crucial for the prevention of inflammatory diseases, such as psoriasis and endotoxin shock (14,15). We previously reported that Ido2-derived Kyn in hepatocytes prevents severe hepatocellular damage and liver fibrosis induced by CCl4 through activation of Ahr signaling-dependent inflammatory responses (16). However, the biological and physiological roles of Ido2 under liver regeneration conditions remain unclear. Thus, we investigated the role of Ido2 expression in intrahepatic MNCs after PHx.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval

The ethics governing the use and conduct of experiments on animals were strictly observed, and the experimental protocol was approved by the Animal Care of Fujita Health University. The protocol for all animal experiments was approved by the Animal Experimentation Committee of Fujita Health University (approval no. AP20031-R21). Procedures involving mice and their care conformed to international guidelines, as described in Principles of Laboratory Animal Care (National Institutes of Health publication 85–23, revised 1985).

Mice

Ido2-KO mice on a C57BL/6 N background were obtained from the Knockout Mouse Project (KOMP, CA, USA). Homozygous Ido2-KO mice generated by intercrossing heterozygous mice were used for the following experiments. These mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free environment in our facility, maintained at 25°C room temperature, 40–60% humidity, on a 12 h light/dark cycle (lights on at 08:00), and had free access to food and water.

Animal experiment

Mice underwent 70% PHx, as previously described (17). Briefly, mice were incised in the upper abdominal wall, the liver was exposed, and three anterior lobes (right medial, left medial, and left lateral) were rejected by proximal ligation under inhalational anesthetic with isoflurane (anesthetic induction on 4% isoflurane, followed by anesthetic maintenance on 2% isoflurane). Mice were kept warm at 37°C until postoperative awakening. The control group undergone midline laparotomy incision without liver lobe resection. Mice were randomly selected for the partial hepatectomy treatment group at each time point. Mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation at each time point and analyzed (17,18). The experiments complied with the ARRIVE guidelines (19).

Immunohistochemistry

The livers were fixed in 10% buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Immunohistochemical staining for PCNA were used to evaluate hepatocyte proliferation in the liver as previously described (18). Briefly, 4-µm thick sections of the livers were deparaffinized and treated with 3% hydrogen peroxide to inactivate endogenous peroxidases. The sections were heated in 0.1 M citrate buffer (pH 6.0) using the autoclave. The sections were treated with 10% goat serum (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) for 60 min to prevent non-specific antibody binding and then incubated with anti-PCNA (1:2,000, catalog no. LS-B14132, LSBio, Seattle, WA, USA) overnight at 4°C. After washing, primary antibody-stained sections were incubated with horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated rabbit immunoglobulin antibody solution (1:1, Histofine Simple Stain MAX-PO(R), Nichirei, Tokyo, Japan), followed by 3,3′-diaminobenzidine staining (catalog no. K3468, DAKO, Tokyo, Japan). Finally, the sections were counterstained using Mayer's hematoxylin.

RNA extraction and real-time qPCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted from cell lines with ISOGENII (Nippon gene, Tokyo, Japan) and reverse transcription-PCR was performed using Revatra Ace Kits (Toyobo, Tokyo, Japan). PCR amplification was performed using Sso advanced SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). The thermocycling conditions were as follows: denaturation at 95°C for 2 min, annealing at 60°C for 30 sec and elongation at 72°C for 20 sec. The qPCR primers were as follows: IL-6 sense 5′-GATACCACTCCCAACAGA-3′ and antisense 5′-GCCATTGCACAACTCTTT-3′; TNF-α sense 5′-TCATGCACCACCATCAAG-3′ and antisense 5′-CAGAACTCAGGAATGGACAT-3′; Ido1 sense 5′-AGTTGGGCCTGCCTCCTATTC-3′ and antisense 5′-GAAGAAGCCCTTGTCGCAGTC-3′; Ido2 sense 5′-CATACCAGGCAATTGCTCCAC-3′ and antisense 5′-GCCTGGGCTAAAGAGCTCAATAC-3′; 18s sense, 5′-GGATTGACAGATTGATAGC-3′ and antisense 5′-TATCGGAATTAACCAGACAA-3′. CyclinD1 sense, 5′-AGTGCGTGCAGAAGGAGATT-3′ and antisense 5′-CACAACTTCTCGGCAGTCAA-3′; Birc5 sense 5′-TACCTCAAGAACTACCGCATCG-3′ and antisense 5′-AAGGCTCAGCATTAGGCAGC-3′; Foxm1 sense 5′-GGAGGAAATGCCACACTTAGCG-3′ and antisense 5′-TAGGACTTCTTGGGTCTTGGGGTG-3′. The mRNA expression levels of IL-6, TNF-α, Ido1, Ido2, and 18s rRNA were analyzed on a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR Systems in conjunction with Applied Biosystems™ software (Applied Biosystems).

Measurements of kynurenine pathway metabolites

Trp and Kyn levels were measured as previously reported (16). Briefly, MNCs and liver were homogenized (1:4, w/v) in 10% perchloric acid. Next, 50 µl of the supernatants were subjected to high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC; SHIMADU, Kyoto, Japan).

Measurement of serum cytokines

The concentration of IL-6 and TNF-α in the sera was measured by Mouse ELISA Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

MNCs isolation

MNCs were isolated as previously described (17,18). The livers of mice treated with or without PHx were perfused slowly via the inferior vena cava with 10 ml of cold PBS. Briefly, the excised liver was cut into small pieces with scissors in digestion medium (RPMI-1640 containing 10% fetal bovine serum and 20 U/ml collagenase Type I) and then incubated at 37°C for 45 min with shaking at 180 rpm. After incubation, collagenase-digested hepatic cells were pressed through 70 µm cell strainer and were centrifuged at 50 × g for 3 min at 4°C. Then, the supernatant was collected and centrifuged at 600 × g for 5 min at 4°C. Pellet was applied to a discontinuous 70 and 40% Percoll density gradient (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), and the cells at the interface were used as mononuclear cells.

Cell culture and immunocytochemical analysis

Murine resident peritoneal macrophages were stimulated with LPS (1 ng/ml, Escherichia coli O55:B5; Sigma-Aldrich) for indicated time periods. After cultivation, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS for 10 min and permeabilized with 0.2% TritonX-100/PBS for 10 min. After being blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA)/PBS for 60 min, the cells were incubated with rat monoclonal anti-F4/80 antibody (1:50, catalog no. ab16911, Abcam Cambridge, U.K.) or rabbit monoclonal anti-NF-κB (1:400, catalog no. #8242, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA) at 4°C, overnight. After washing, the cells were incubated with goat anti-rat IgG (H+L) antibody (1:200, catalog no. ab150157, Abcam) or rabbit anti-rat IgG (H+L) antibody (1:500, catalog no. 611-142-122, Rockland Immunochemicals, Inc. Limerick, PA) for 1 h, respectively. Nuclei were stained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Dojindo, Tokyo, Japan).

Western blotting and nuclear extraction

The livers were washed with cold PBS. Nuclear/cytosolic fractions were isolated using Lysopure™ Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extractor Kit (Wako Chemical), according to the manufacturer's protocol. Ten micrograms of protein were loaded on 10% Mini-PROTEAN TGX gels (Bio-Rad) and transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were incubated with anti-IκB (1:1,000, catalog no. #4812, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-NF-κB p65 (1:1,000, catalog no. #8242, Cell Signaling Technology), anti-Lamin B1 (1:2,000, catalog No. 66095-1-lg, proteintech), β-actin (catalog no. A5441, Sigma-Aldrich), anti-Ido2 (1:1,000, catalog no. ab214214, abcam), anti-Ido1 (1:1,000, catalog no. MABF850, Merck Millipore, Darmstadt, Germany), or anti-Tdo2 (1:1,000, catalog no. MABN1537, Merck Millipore). The membranes were then incubated with HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (1:10,000, catalog no. NA931A, Cytiva., Tokyo, Japan) or HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:5,000, catalog no. NA934V, Cytiva., Tokyo, Japan), respectively. The detection of target proteins was performed with Amersham ECL Prime Western Blotting Detection Reagent (Cytiva). Protein levels were quantified by ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD). To re-probe the PVDF membranes, the antibodies bound to the membranes were removed by a commercial stripping solution.

Statistical analysis

Statistics were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 6 Software (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, USA). All data are expressed as means ± SEM. Differences between WT and knockout mouse groups were analyzed by the Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Scheffe's test. A value of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant (Fig. 1A). For the values obtained in time course experiments, statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's multiple-comparison test. A P-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

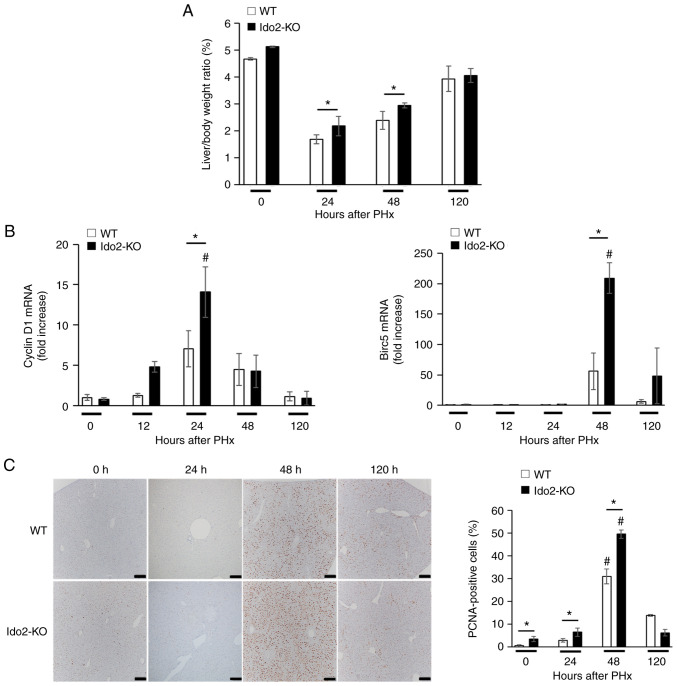

Figure 1.

Ido2-deficient mice exhibit increased liver regeneration. WT mice and Ido2-KO mice were subjected to 70% PHx and were sacrificed and analyzed at the indicated time points (n=5-7 each). (A) Liver body ratio of WT and Ido2-KO mice were measured following PHx. (B) Expression of pro-proliferative genes in the liver was measured at indicated time points after PHx. The results were normalized to the expression of 18S rRNA. (C) Immunohistochemical staining for PCNA expression in liver sections from experimental mice after PHx. The frequency of PCNA+ cells was counted in 10 high-power fields from each liver tissue (scale bar, 200 µm. *P<0.05; #P<0.05 vs. 0 h in each mouse. WT, wild-type; Ido2, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 2; KO, knockout; PHx, partial hepatectomy.

Results

Ido2 deficiency promotes liver regeneration after PHx

To investigate the roles of Ido2 in liver regeneration, we compared liver weight and hepatocyte growth between WT and Ido2-KO mice that were subjected to PHx. Although the ratio of liver to body weight after PHx was significantly higher in Ido2-KO mice than in WT mice at 24 and 48 h after PHx, the ratio was comparable between these mice at 120 h (Fig. 1A). The expression of pro-proliferative genes (Cyclin D1 and Birc5) was significantly higher in Ido2-KO mice than that in WT mice. (Fig. 1B). Consistent with these results, the frequency of PCNA+ cells were significantly increased in Ido2-KO mice compared to WT mice 48 h after PHx (Fig. 1C). These results suggest that Ido2 deficiency accelerates liver regeneration after PHx.

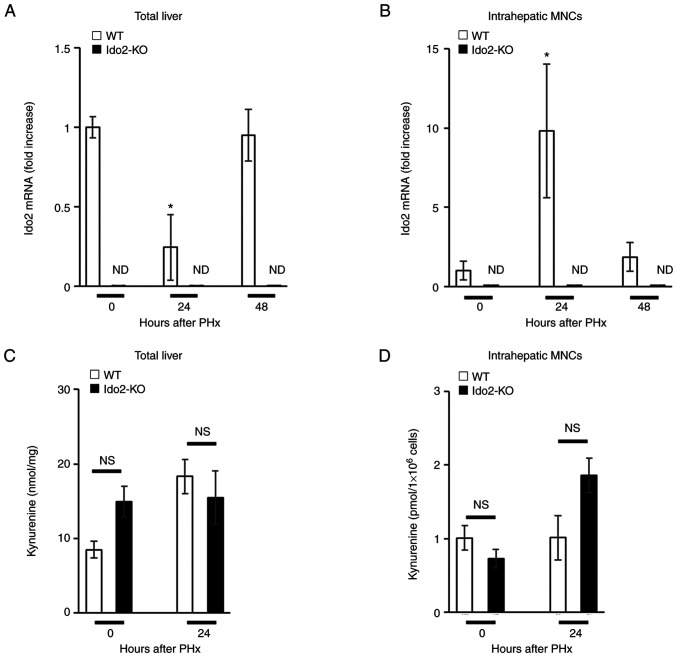

Elevated Ido2 expression in intrahepatic mononuclear cells after PHx

Next, we examined Ido2 expression during liver regeneration after PHx. Ido2 expression was reduced in the total liver 24 h after PHx but was restored within 48 h (Fig. 2A). In contrast, Ido2 expression in intrahepatic MNCs was increased 24 h after PHx and was decreased to baseline levels within 48 h (Fig. 2B). Intriguingly, the levels of Ido1 mRNA expression and Kyn in total liver or intrahepatic MNCs after PHx were comparable between Ido2-KO mice and WT mice (Figs. 2C, D, and Fig. S1). Since Ido2 expression was mainly induced in intrahepatic MNCs after PHx (Fig. 2A and B), we focused on intrahepatic MNCs in the following experiments.

Figure 2.

Expression of the Ido2 gene is increased in intrahepatic MNCs following PHx. WT (n=3) and Ido2-KO (n=3) mice were subjected to 70% PHx. After each time point, the mice were sacrificed and total liver and intrahepatic MNCs were isolated. (A) Total liver and (B) intrahepatic MNCs were analyzed to assess Ido2 mRNA expression using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. (ND, not detected). The results were normalized to the expression of 18S rRNA. (C) Kyn concentration in total liver from WT and Ido2-KO mice was determined using HPLC (0 h group, n=3; 24 h group, n=8). (D) Kyn concentration in intrahepatic MNCs from WT (n=3) and Ido2-KO (n=3) mice was determined using HPLC. *P<0.05 compared with 0 h in each mouse. NS, not significant; HPLC, high-performance liquid chromatography; WT, wild-type; Ido2, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 2; KO, knockout; PHx, partial hepatectomy; MNC, mononuclear cells; rRNA, ribosomal RNA; Kyn, kynurenine.

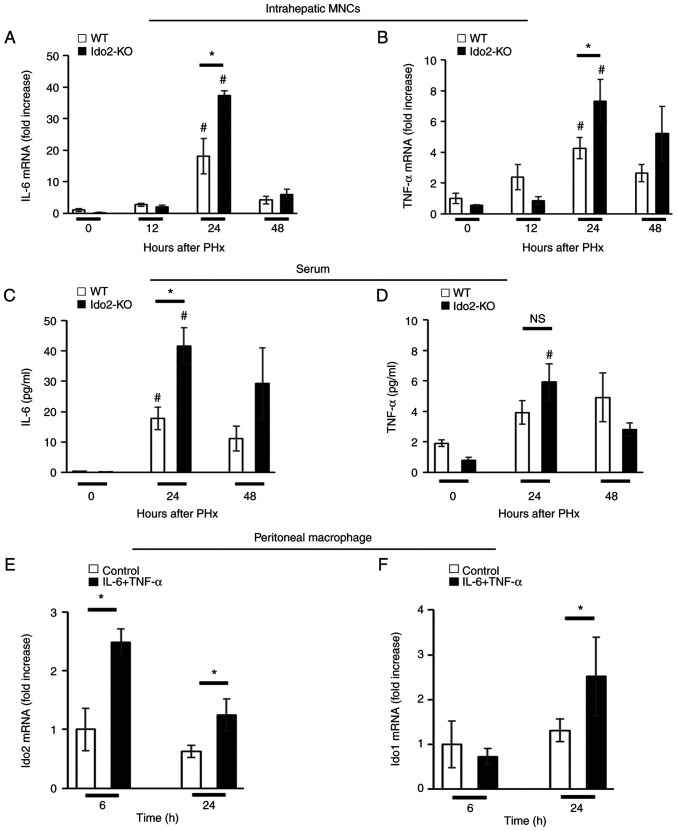

Ido2 deficiency enhances inflammatory cytokine production after PHx

Hepatic expression of TNF-α and IL-6 is essential for hepatocyte proliferation (1,2). We measured the expression of these inflammatory cytokines in intrahepatic MNCs after PHx. The expression of IL-6 and TNF-α mRNA in intrahepatic MNCs was significantly higher in Ido2-KO mice than in WT mice 24 h after PHx (Fig. 3A and B). Similar results were obtained in the sera after PHx. (Fig. 3C and D).

Figure 3.

Ido2-deficient mice exhibit augmented inflammatory cytokine expression. Relative mRNA expression levels of (A) IL-6 and (B) TNF-α in the intrahepatic MNCs of WT (n=5) and Ido2-KO (n=5) mice after PHx were measured using reverse transcription-quantitative PCR. The results were normalized to the expression of 18S rRNA. Concentration of (C) IL-6 and (D) TNF-α in the sera of WT (n=5) and Ido2-KO (n=5) mice after PHx were determined using ELISA. Expression of Ido2 and Ido1 mRNA in peritoneal macrophages of WT mice (n=3 per group) treated with or without recombinant (E) IL-6 (20 ng/ml) and (F) TNF-α (20 ng/ml). The results were normalized to the expression of 18S rRNA. *P<0.05; #P<0.05 vs. 0 h in each mouse. NS, not significant; WT, wild-type; Ido2, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 2; KO, knockout; PHx, partial hepatectomy; MNC, mononuclear cells; rRNA, ribosomal RNA.

Next, we assessed whether Ido2 expression was induced by these inflammatory cytokines. Therefore, we used peritoneal resident macrophages instead of intrahepatic MNCs because the frequency of MNCs in the liver is low to isolate as single cells. Ido2 and Ido1 mRNA expression was induced in peritoneal macrophages by a mixture of IL-6 and TNF-α (Fig. 3E and F). These results suggest that Ido2 is rapidly induced by inflammatory cytokines.

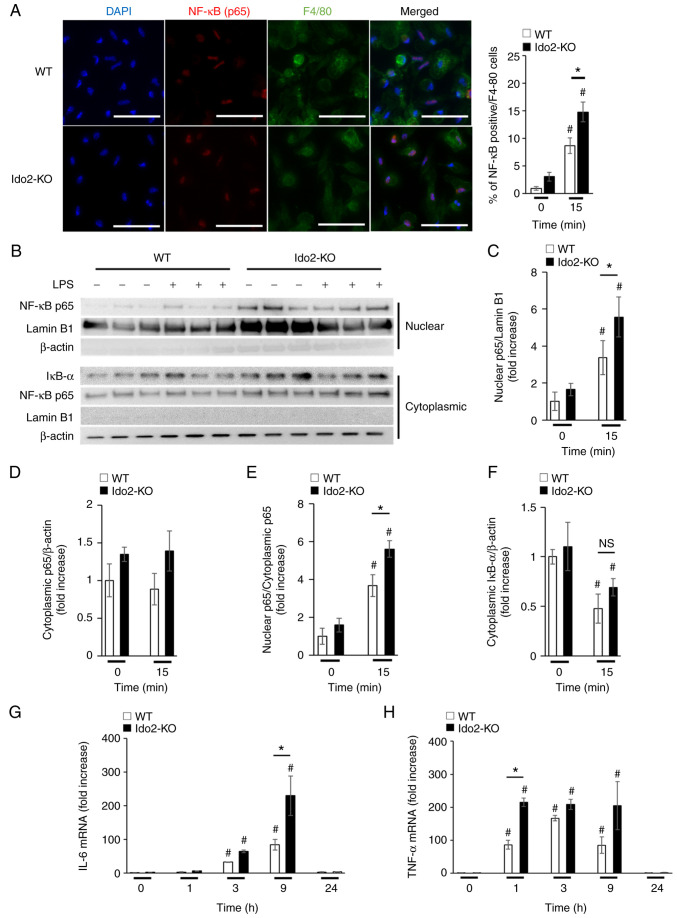

Ido2 deficiency enhances NF-κB intranuclear transport in intrahepatic MNCs

The production of TNF-α and IL-6 after PHx is dependent on NF-κB signaling (4,5). To determine whether NF-κB-mediated production of these cytokines is enhanced in Ido2-KO mice, peritoneal macrophages were stimulated with LPS, which mimics stimulation with the endogenous TLR ligands that are produced after PHx. Upon stimulation with LPS, the nuclear transport of NF-κB (p65) in macrophages was increased in Ido2-KO mice compared to WT mice, as measured by immunocytochemical (Fig. 4A) and western blotting analysis (Fig. 4B-F). Moreover, the mRNA expression levels of IL-6 (Fig. 4G) and TNF-α (Fig. 4H) in peritoneal macrophages from Ido2-KO mice after LPS stimulation were significantly enhanced compared with those in WT mice. Importantly, the levels of Ido1 and Tdo2 protein in peritoneal macrophages were comparable between WT and Ido2-KO mice at this time point (Fig. S2). These results suggest that increased Ido2 expression in peritoneal macrophages may regulate inflammatory cytokine production by suppressing NF-κB signaling.

Figure 4.

Ido2 deficiency enhances NF-κB signaling in peritoneal macrophages. Peritoneal macrophages from WT and Ido2-KO mice were incubated with or without LPS (1 ng/ml) for the indicated time. Intracellular expression of NF-κB p65 in LPS-stimulated peritoneal macrophages was analyzed by (A) immunocytochemical staining and (B) western blotting using indicated antibodies. (A) Frequency of NF-κB p65+F4/80+ cells were determined in 10 high-power fields (scale bars, 50 µm; n=10 per group). Relative densitometric intensity of (C) intranuclear or (D) cytoplasmic NF-κB p65 was determined for each protein band and normalized to that of Lamin B1 (n=3 per group) or β-actin (n=3 per group). (E) Nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio of NF-κB p65 was determined in each normalized protein band. (F) Relative densitometric intensity of cytoplasmic IkB-α was determined for each protein band and normalized to that of β-actin (n=3 per group). (G) IL-6 and (H) TNF-α mRNA expression in peritoneal macrophages of WT mice (n=3 per group) at the indicated time points after LPS stimulation. The results were normalized to 18S rRNA. *P<0.05; #P<0.05 vs. 0 min in each mouse. WT, wild-type; Ido2, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 2; KO, knockout; PHx, partial hepatectomy; MNC, mononuclear cells; rRNA, ribosomal RNA; LPS, lipopolysaccharide.

Discussion

In the present study, we demonstrated that Ido2 deficiency elevated the production of inflammatory cytokines and promoted liver regeneration after PHx. Elevated expression of inflammatory cytokines is suppressed by the intrinsic Ido2 expression in immune cells (such as intrahepatic MNCs and possibly macrophages). Further, Ido2 expression in intrahepatic MNCs may regulate NF-κB signaling and control inflammatory cytokine production after PHx.

Absence of Ido2 leads to the development of inflammatory diseases such as endotoxin shock and psoriasis via the aberrant production of inflammatory cytokines (14,15). Similarly, although aberrant production of inflammatory cytokines is induced in intrahepatic MNCs from PHx-treated Ido2-KO mice, these cytokines are essential for hepatocyte growth, which leads to liver regeneration. Therefore, Ido2 deficiency may have beneficial effects on liver regeneration.

Kyn is known to inhibit NF-κB signaling-mediated production of inflammatory cytokines through its interaction with Ahr (20,21). We recently reported that absence of Ido2 suppresses Ahr signaling in hepatocytes (16). In this context, we showed that Ido1 mRNA expression and production of Kyn did not differ between WT and Ido2-KO mice after PHx. Therefore, regulation of NF-κB by Kyn cannot be ruled out, but is considered to be small. Based on our findings, the role of Ido2 may differ between intrahepatic MNCs and hepatocytes in terms of Ahr/NF-κB signaling.

We found that intrahepatic MNC-intrinsic Ido2 regulates hepatocyte proliferation after PHx, which raises some questions. First, does hepatocyte-intrinsic Ido2 regulate hepatocyte proliferation? Under steady-state conditions, the frequencies of PCNA+ hepatocytes were found to be significantly higher in Ido2-KO mice than in WT mice regardless of inflammatory cytokine production, suggesting that hepatocyte-intrinsic Ido2 is dispensable for regeneration after PHx. Second, how does Ido2 affect NF-κB activation in a Kyn-independent manner? Ido1 and possibly Ido2 are reported to play non-enzymatic signaling role (13,22,23). In a transforming growth factor β (TGF-β)-dominated microenvironment, Ido1, which is phosphorylated by Fyn kinase, interacts with SH2 domain-containing phosphatases and phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase (p85), leading to the activation of non-canonical NF-κB (22). Recently, the non-enzymatic signaling capacity of Ido2 has been reported to be required for autoimmune arthritis development (23). According to this report, Ido2 interacts with Runx1, GAPDH, RANbp10, and Mgea5, all of which may be involved in immune signaling. Interestingly, Runx1 interacts with NF-κB (p50) to produce inflammatory cytokines in LPS-stimulated macrophages (24), implying that Ido2 might suppress NF-κB activation via regulation of Runx1. Although we did not identify Ido2-interacting proteins in a PHx model, our findings provide a promising potential for Ido2 as a non-enzymatic signaling protein that regulates the NF-κB pathway through a negative feedback loop. Further investigation is needed to identify the mechanism by which Ido2 and its product Kyn regulate liver regeneration through inflammatory cytokine production.

In conclusion, this study suggests that Ido2 deficiency in intrahepatic MNCs augments inflammatory cytokine production and hepatocyte proliferation following PHx. Ido2 may inhibit inflammatory cytokine production by regulating NF-κB in intrahepatic MNCs. Therefore, Ido2 may be a novel target for liver regeneration in various hepatic injuries.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by Grants-in-Aids for Research Activity Start-up (grant no. 19K23873) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) and the Private University Research Branding Project from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (MEXT).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

TA and MH designed the study. TA, MH and HT performed the experiments. TA, MH, and KN were responsible for data integrity and analyses. TA, MH, HT, HI, KN, YY and KS discussed and interpreted the data. TA, MH, HT and HI drafted the manuscript. TA, MH, HT, YY and KS conducted the study. TA and MH confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. KS had the primary responsibility for the final content. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The experimental protocol was approved by the Animal Care of Fujita Health University. The protocol for all animal experiments was approved by the Animal Experimentation Committee of Fujita Health University (approval no. AP20031-R21).

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Taub R. Liver regeneration: From myth to mechanism. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:836–847. doi: 10.1038/nrm1489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fausto N. Liver regeneration. J Hepatol. 2000;32((1 Suppl)):S19–S31. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8278(00)80412-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mitchell C, Willenbring H. A reproducible and well-tolerated method for 2/3 partial hepatectomy in mice. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:1167–1170. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Seki E, Tsutsui H, Iimuro Y, Naka T, Son G, Akira S, Kishimoto T, Nakanishi K, Fujimoto J. Contribution of Toll-like receptor/myeloid differentiation factor 88 signaling to murine liver regeneration. Hepatology. 2005;41:443–450. doi: 10.1002/hep.20603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen Y, Sun R. Toll-like receptors in acute liver injury and regeneration. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11:1433–1441. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2011.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cornell RP, Liljequist BL, Bartizal KF. Depressed liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy of germ-free, athymic and lipopolysaccharide-resistant mice. Hepatology. 1990;11:916–922. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840110603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wolf JH, Bhatti TR, Fouraschen S, Chakravorty S, Wang L, Kurian S, Salomon D, Olthoff KM, Hancock WW, Levine MH. Heat shock protein 70 is required for optimal liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in mice. Liver Transpl. 2014;20:376–385. doi: 10.1002/lt.23813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hoshi M, Matsumoto K, Ito H, Ohtaki H, Arioka Y, Osawa Y, Yamamoto Y, Matsunami H, Hara A, Seishima M, Saito K. L-tryptophan-kynurenine pathway metabolites regulate type I IFNs of acute viral myocarditis in mice. J Immunol. 2012;188:3980–3987. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ito H, Hoshi M, Ohtaki H, Taguchi A, Ando K, Ishikawa T, Osawa Y, Hara A, Moriwaki H, Saito K, Seishima M. Ability of IDO to attenuate liver injury in alpha-galactosylceramide-induced hepatitis model. J Immunol. 2010;185:4554–4560. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0904173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bessede A, Gargaro M, Pallotta MT, Matino D, Servillo G, Brunacci C, Bicciato S, Mazza EM, Macchiarulo A, Vacca C, et al. Aryl hydrocarbon receptor control of a disease tolerance defence pathway. Nature. 2014;511:184–190. doi: 10.1038/nature13323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Takenaka MC, Gabriely G, Rothhammer V, Mascanfroni ID, Wheeler MA, Chao CC, Gutiérrez-Vázquez C, Kenison J, Tjon EC, Barroso A, et al. Control of tumor-associated macrophages and T cells in glioblastoma via AHR and CD39. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22:729–740. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0446-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogiso H, Ito H, Kanbe A, Ando T, Hara A, Shimizu M, Moriwaki H, Seishima M. The inhibition of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase accelerates early liver regeneration in mice after partial hepatectomy. Dig Dis Sci. 2017;62:2386–2396. doi: 10.1007/s10620-017-4651-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prendergast GC, Metz R, Muller AJ, Merlo LMF, Mandik-Nayak L. IDO2 in immunomodulation and autoimmune disease. Front Immunol. 2014;5:585. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fujii K, Yamamoto Y, Mizutani Y, Saito K, Seishima M. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 2 deficiency exacerbates imiquimod-induced psoriasis-like skin inflammation. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21:5515. doi: 10.3390/ijms21155515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamamoto Y, Yamasuge W, Imai S, Kunisawa K, Hoshi M, Fujigaki H, Mouri A, Nabeshima T, Saito K. Lipopolysaccharide shock reveals the immune function of indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 2 through the regulation of IL-6/stat3 signalling. Sci Rep. 2018;8:15917. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-34166-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoshi M, Osawa Y, Nakamoto K, Morita N, Yamamoto Y, Ando T, Tashita C, Nabeshima T, Saito K. Kynurenine produced by indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase 2 exacerbates acute liver injury by carbon tetrachloride in mice. Toxicology. 2020;438:152458. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2020.152458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ito H, Ando K, Nakayama T, Taniguchi M, Ezaki T, Saito K, Takemura M, Sekikawa K, Imawari M, Seishima M, Moriwaki H. Role of Valpha 14 NKT cells in the development of impaired liver regeneration In vivo. Hepatology. 2003;38:1116–1124. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ando T, Ito H, Kanbe A, Hara A, Seishima M. Deficiency of NALP3 signaling impairs liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy. Inflammation. 2017;40:1717–1725. doi: 10.1007/s10753-017-0613-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Percie du Sert N, Hurst V, Ahluwalia A, Alam S, Avey MT, Baker M, Browne WJ, Clark A, Cuthill IC, Dirnagl U, et al. The ARRIVE guidelines 2.0: Updated guidelines for reporting animal research. PLoS Biol. 2020;18:e3000410. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3000410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vogel CFA, Matsumura F. A new cross-talk between the aryl hydrocarbon receptor and RelB, a member of the NF-kappaB family. Biochem Pharmacol. 2009;77:734–745. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2008.09.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gutiérrez-Vázquez C, Quintana FJ. Regulation of the immune response by the Aryl hydrocarbon receptor. Immunity. 2018;48:19–33. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.12.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fallarino F, Grohmann U, Puccetti P. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase: From catalyst to signaling function. Eur J Immunol. 2012;42:1932–1937. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merlo LMF, Peng W, DuHadaway JB, Montgomery JD, Prendergast GC, Muller AJ, Mandik-Nayak L. The immunomodulatory enzyme IDO2 mediates autoimmune arthritis through a nonenzymatic mechanism. J Immunol. 2022;208:571–581. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.2100705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo MC, Zhou SY, Feng DY, Xiao J, Li WY, Xu CD, Wang HY, Zhou T. Runt-related transcription factor 1 (RUNX1) binds to p50 in macrophages and enhances TLR4-triggered inflammation and septic shock. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:22011–22020. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.715953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.