Abstract

The global rate of human male infertility is rising at an alarming rate owing to environmental and lifestyle changes. Phthalates are the most hazardous chemical additives in plastics and have an apparently negative impact on the function of male reproductive system. Ferroptosis is a recently described form of iron-dependent cell death and has been linked to several diseases. Transferrin receptor (TfRC), a specific ferroptosis marker, is a universal iron importer for all cells using extracellular transferrin. We aim to investigate the potential involvement of ferroptosis during male reproductive toxicity, and provide means for drawing conclusions on the effect of ferroptosis in phthalates-induced male reproductive disease. In this study, we found that di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) triggered blood-testis barrier (BTB) dysfunction in the mouse testicular tissues. DEHP also induced mitochondrial morphological changes and lipid peroxidation, which are manifestations of ferroptosis. As the primary metabolite of DEHP, mono-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (MEHP) induced ferroptosis by inhibiting glutathione defense network and increasing lipid peroxidation. TfRC knockdown blocked MEHP-induced ferroptosis by decreasing mitochondrial and intracellular levels of Fe2+. Our findings indicate that TfRC can regulate Sertoli cell ferroptosis and therefore is a novel therapeutic molecule for reproductive disorders in male patients with infertility.

Keywords: Di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate, Blood-testis barrier, Transferrin receptor, Sertoli cells, Ferroptosis

Graphical abstract

DEHP causes BTB dysfunction to Sertoli cells, and promotes ferroptosis by increasing TfRC level in Sertoli cells. Regulation TfRC level holds potential in treating ferroptosis-induced male reproductive disease.

Highlights

-

•

DEHP impairs blood-testis barrier and secretory function of Sertoli cells.

-

•

DEHP causes glutathione metabolism disorder and iron overload in Sertoli cells.

-

•

Transferrin receptor facilitates iron accumulation, thereby inducing ferroptosis.

-

•

DEHP disrupts blood-testis barrier by transferrin receptor-mediated ferroptosis.

1. Introduction

Over the last few decades, the production and use of plasticizers have increased worldwide owing to their flexibility and elasticity. However, they can induce reproductive defects and fertility decline in mammals [1,2]. Phthalates are primarily used as plasticizers to soften polyvinyl chloride products, and di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP) is the most widely used and studied phthalates [3]. The use of phthalates continues to grow and accounts for over 55% of the global consumption of plasticizers in 2020 [4]. DEHP accounts for approximately 50% of the total production of phthalates, exceeding 2 million tons worldwide [5]. DEHP is classified as a Group 2B human carcinogen by the United States Environmental Protection Agency, which has designated it as a high-priority substance based on health risk assessments [6]. As DEHP does not form any chemical bonds with product matrices, it can leach into the environment from plastic products as it degrades over time, thereby causing damage to the environment and organisms [7]. Because of the extensive use and discarding of plastic products in diverse environments, including soil, water, and air, DEHP accumulates in the human body through the food chain, impairing organ function, especially in the reproductive system [8]. The health of mammals has been most affected with respect to plastic pollution, which has been the subject of extensive recent research. Nevertheless, limited attention has been paid to the male reproductive toxicity of DEHP, and data at the molecular level are limited. Therefore, it is necessary to understand the toxic effects of DEHP on male reproduction.

Ferroptosis is a type of iron-dependent cell death that differs from other forms of cell death forms, such as apoptosis [9]. Transferrin is an iron carrier protein that binds to Fe3+ to deliver iron to different tissues via transferrin receptor (TfRC)-mediated endocytosis. Excess intracellular iron is stored in ferritin or exported out of the cell via ferroportin but under ferroptosis conditions iron is required to drive lipid peroxidation [10]. A recent report has proved that the change of TfRC causes growth retardation, metabolic disorder, and lethality in muscle, shedding light on the importance of TfRC in muscle physiology [11]. TfRC is a potential factor to drive both aberrant iron accumulation and ferroptosis, thereby exacerbating acute liver damage, providing clinical implications for hepatic ischemia followed by reperfusion patients [12]. TfRC is abundantly expressed and involved in the process of numerous diseases, such as breast, colon, brain, and liver cancer, indicating that TfRC will be a potential therapeutic target [13]. Collectively, these studies indicate that modulation of TfRC-mediated ferroptosis is a potential therapeutic strategy for various pathological conditions.

The development and function of the testicle are crucially reliant on Sertoli cells, which are key role in androgen generation and maintaining male health [14]. One of the functions of Sertoli cells is to maintain the blood-testis barrier (BTB), which is one of the tightest blood-tissue barriers and formed by tight junctions between Sertoli cells [15]. The BTB undergoes rapid remodeling during the epithelial cycle of spermatogenesis, and tight junctions coexist and cofunction with adherens junctions, and gap junctions [16]. Sertoli cells are also androgen-responsive somatic cells that can secrete transferrin, androgen receptor (AR), androgen-binding protein (ABP), and follicle-stimulating hormone receptor (FSHR). AR and ABP are essential for sperm production and male fertility maintenance [17]. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) acts on Sertoli cells during spermatogenesis, germ cell survival, and male fertility through its receptors, such as FSHR [18]. Transferrin accounts for 5% of all proteins secreted by Sertoli cells and is critical for the regulation of spermatogenesis [19]. However, little is known about the effect of DEHP on the structure and function of Sertoli cells.

Spermatogenesis is an iron-dependent process in which iron is imported to the seminiferous tubule by TfRC-transferrin complex, primarily secreted and produced by Sertoli cells [20]. TfRC imports iron from the extracellular environment into cells by interacting with transferrin, contributing to the cellular iron pool required for ferroptosis [21]. TfRC has been widely used for the evaluation of cell function and has been successfully included in studies designed to investigate possible functional changes produced in response to harmful events. Given the potential role of TfRC in Sertoli cells, we hypothesize that DEHP controls the signaling pathways of ferroptosis in mouse testes. To test this hypothesis, we aim to evaluate the structure and function of Sertoli cell in the testis. Using in vivo and vitro approaches, the present study intends to determine whether TfRC as an iron uptake regulator could mediate the ferroptosis-sensitizing effect of phthalate. This study may provide an emerging insight in male reproductive disease and a novel starting point for solving the problem of “The Global Plastic Toxicity Debt”.

2. Methods

2.1. Animals

All animal procedures were performed in accordance with the Guidelines for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of Northeast Agricultural University (NEAU) and approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of NEAU (NEAUEC20220341). All animal experiments comply with the ARRIVE guidelines. Three-week-old male ICR mice were purchased from Liaoning Changsheng Biotech Co., Ltd. (Benxi, Liaoning, China). The male mice were ad libitum fed standard chow and water under a 12-h light/dark cycle and assigned to five groups. The mice were maintained under specific conditions at 21–23 °C and 35–65% humidity. All mice (20/group) were treated with water, corn oil and DEHP at a dose of 50, 200, and 500 mg/kg/d (D50, D200, and D500, respectively) by oral gavage (Fig. 1A) (Table S1). The gavage lasted for 4 weeks until the mice were sacrificed.

Fig. 1.

DEHP induces structural and functional damage to Sertoli cells. (A) The mice were treated with water, corn oil and DEHP at a dose of 50, 200, and 500 mg/kg/d (D50, D200, and D500, respectively) by oral gavage for 28 days. (B) Testis coefficient. (C) Histopathology with H&E, staining. (D) Johnsen Score. (E) AR, ABP, FSHR and Tf protein levels in mice testes; β-actin served as loading control for the total fraction. (F) Changes of BTB structure in mice. (G) The function and integrity BTB in mouse testis. (H) BTB-related protein levels in mice testes; β-actin served as loading control for the total fraction. (I) Transmission electron microscopy and Flameng scores; yellow: mitochondria. (J) Eosin staining of mouse sperm, Papanicolaou staining of mouse sperm and sperm malformation. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Symbol for the significance of differences between the Vcon group and another group: **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

2.2. Reagent and dose selection

DEHP was obtained from Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., LTD, (Shanghai, China). Pubertal exposure to DEHP (50 and 500 mg/kg/d) induces germ cell apoptosis via suppressing ER stress in testes [22]. The lowest observed adverse effect level of DEHP was 140 mg/kg [23]. After oral administration of DEHP, the lethal dose 50 in rodent is 30 g/kg. At the doses of DEHP used were similar to the recent report, at the doses of 50 mg/kg (1/600 LD50), 200 mg/kg (1/150 LD50), and 500 mg/kg (1/60 LD50) [24]. DEHP (200 mg/kg/d) causes DNA damage in sperm and has detrimental effects on the reproductive system from the prepubertal to the pubertal period [25]. DEHP (500 mg/kg/d) induces spermatogenesis disorder by inhibiting testosterone/androgen receptor pathway [26]. The DEHP in soil (1–264 mg/kg) or sewage sludge (12–1250 mg/kg) is difficult to degrade and thus persist in the environment [27]. Daily intake of DEHP for critically ill preterm infants or occupational exposed population can reach 16 mg/kg per day, equivalent to 200 or 500 mg/kg in mice [28].

2.3. Testicular index

The testes of the mice were photographed and weighed, and the relative weight of the testis was calculated. The testicular index was calculated as the ratio of the testicular weight to body as a in percentage.

2.4. Hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining

Dissected testes were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde, embedded in paraffin, and cut into 4 μm thick sections. The sections were then deparaffinized, stained with H&E and viewed and photographed using a digital scanner microscope (Panoramic MIDI, 3DHISTECH Ltd., Hungary). Histopathological scoring was then performed on 10 different fields in each section according to Johnsen's criteria [29].

2.5. Transmission electron microscopy

The testicular tissue and TM4 cells were fixed in glutaraldehyde. Then, they were post-fixed in OsO4, dehydrated and embedded in epoxy resin. Slices of testicular and TM4 cells were stained. Images were captured using a transmission electron microscope (HT7650; Hitachi, Japan). Based on previous research methods [30,31], the Flaming mitochondrial injury score (Flameng score) was estimated and the mitochondrial average surface area was determined using ImageJ software.

2.6. Evaluation of the integrity of the BTB

The mice were treated with CdCl2 (3 mg/kg) by intraperitoneal injection before the last day of the experiment as positive control. FITC method was performed to evaluate BTB integrity as previous study [32]. The distribution of FITC was observed using fluorescence microscope (Leica, Germany).

2.7. Sperm morphology

The sperm was collected from cauda epididymides and placed in physiological saline (37 °C). The sperm was stained by Quick sperm stain kit (Nanjing Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute Co., Ltd., Nanjing, China) and eosin stain kits (Zhuhai Beisuo Biotechnology Co. LTD., Zhuhai, China). Finally, the staining of sperm was observed with an EVOS imaging system (Invitrogen, USA).

2.8. RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) and metabolite profiling analysis

RNA extraction, library construction, and data analysis were performed as part of in RNA-seq analysis, as previously described [33]. Metabolite profiling analysis comprised sample pretreatment, LC/MS detection, and data analysis conducted in accordance with a previous study [34]. RNA-seq and metabolite profiling analyses were performed by Shanghai WeiHuan Biotech Co., Ltd (Shanghai, China). The detailed methods are presented in Supplementary 1.1 and 1.2.

2.9. Determination of DEHP and its metabolite contents

To determine the content of DEHP and its metabolites including MEHP, mono(2-ethyl-5-hydroxyhexyl) phthalate (MEHHP), rac mono(2-ethyl-5-oxohexyl) Phthalate (MEOHP), and mono[2-(carboxymethyl)hexyl] phthalate (2cx MMHP), we used an improved method [35], detailed in Supplementary 1.3.

2.10. Glutathione and oxidative stress biomarker levels

The levels of T-GSH, GSH/GSSG, GSH-PX, GST, MDA and 8-OH were determined in testicular tissue and those of T-GSH, GSH/GSSG, GSH-PX, MDA and LPO in TM4 cell using commercially available kits (Jiancheng Biotech, China). Protein concentration was measured using a total protein quantitative assay kit (Jiancheng Biotech, China). The levels were calculated, corrected using the measured protein concentration, and normalized to that of the control. Specifically, 3-nitrotyrosine (3-NT) and 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE) are markers of oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation, respectively. We detected the relative content of 3-NT and 4‐HNE (Abcam, USA) by using Western blot analysis.

2.11. Iron content

The iron content level in the mouse testes was evaluated using an iron assay kit (Dojindo, Tokyo, Japan). Briefly, fresh mouse testes were homogenized in PBS. After centrifugation, the supernatant was collected, and total Fe, Fe2+, and Fe3+ levels were measured using an iron analysis kit (Dojindo, Tokyo, Japan) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

2.12. RNA extraction and quantification

The mRNA expression was quantified using reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Testicular tissues and TM4 cells were lysed using Trizol (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) to obtain total RNA, which was subjected to reverse transcription using a reagent kit (TransGen Biotech, China). qRT-PCR was performed on the QuantStudio 5 system (ABI). The fold difference was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCt method and is presented relative to ACTB and GAPDH expression (Table S2).

2.13. Western blot analysis

Radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (APExBIO, Houston, USA) supplemented with a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Sigma, Germany) was used to isolate total proteins from testicular tissues and TM4 cells. The proteins were electrophoresed on a sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel and then transferred to nitrocellulose membranes, which were blocked using 5% non-fat dry milk. The membranes were incubated with the corresponding primary antibodies (Abcam, EnglandUK; CST, USA; Affinity, USA; ABclonal Technology, China; Bioss, China) (Table S3) at 4 °C overnight, followed by incubation with the corresponding secondary antibodies (Zhongshan Jinqiao Biotechnology Co., Ltd., Beijing, China). Proteins were visualized using an Amersham Imager (GE, Switzerland). Protein densitometry was performed using the ImageJ software.

2.14. Cell culture and treatment

TM4 cells were obtained from the ATCC and maintained in DMEM/F12 (HyClone, USA) supplemented with 10% FBS (Biological Industries, Israel) and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Gibco, USA) in a 5% CO2 atmosphere at 37 °C. MEHP (AccuStandard Inc., USA) was dissolved in DMSO and incubated for 24 h. The cells were stimulated by different intervention factors, such as 10 μΜ Erastin (Sigma, Germany), 1 μΜ DFO (Sigma, Germany), 1 μΜ Fer-1 (Sigma, Germany) and 5 mM NAC (Sigma, Germany) according to specific experimental protocols.

2.15. Cell viability assay

Cell viability was assessed using CCK-8. In brief, TM4 cells were seeded in a 96-well plate. After 24 h of treatment, the TM4 cells viability was quantified by CCK8 assay according to the manufacturer's instructions. The absorbance was measured at 450 nM by using a standard instrument.

2.16. Determination of total ROS

ROS assay kit (Beyotime, China) was used to assess the total ROS level in TM4 cells. TM4 cells were treated as instructed, and then diluted with 10 μmol/L DCFH-DA using serum-free medium. Then, TM4 cells were incubated with for 20 min. The DCFH-DA was removed by washing the cells three times with PBS. The fluorescence of DCF was analyzed by using fluorescence microscope (Leica, Germany).

2.17. Lipid and mitochondrial ROS probe and image assay

The probes of lipid peroxidation probe BODIPY-C11 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) and mtROS probe MitoSOX (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) were used in TM4 cells. Hoechst (Beyotime, China) was used to stain TM4 cell nuclei. TM4 cells were treated with C11-BODIPY for 30 min and washed with PBS. TM4 cell was incubated with Mito Tracker Green (Beyotime, China) for 30 min, and incubated in MitoSox Red for 10 min. The signal was analyzed using a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Germany).

2.18. Cellular and mitochondrial iron detection

The intracellular Fe2+ was assessed by FerroOrange (Dojindo, Tokyo, Japan), which is a fluorescent probe that enables TM4 cell fluorescent imaging of Fe2+. In Brief, TM4 cells were seeded in 12-well plates and incubated overnight. After specific treatment, TM4 cells were labeled with FerroOrange and Mito-FerroGreen working solution for 30 min. At last, the fluorescence of Fe2+ in cytoplasm and mitochondria of TM4 cells was observed using a fluorescence microscope (Leica, Germany). When detecting the mitochondrial iron, the Mito-Tracker Red (Beyotime, China) was used to mark mitochondria. Hoechst (Beyotime, China) was used to stain cell nuclei. Mean fluorescence intensity was measured by using ImageJ software.

2.19. Cell transfection

The expression vector, used for overexpression of GPX4, was purchased from Shenggong Bioengineering Co., LTD (Shanghai, China). siRNA duplexes were obtained from Ruibo Biotechnology Co., LTD (RiboBio, China), as follows: si-TfRC (target sequence: CGTGCTACTTCTAGACTAA) and si-Tf (target sequence: TGACACCAAATGTTTCGTT). Specific knockdown of TfRC or Tf was attained by transfecting TM4 cells with the corresponding siRNA against the target TfRC or Tf using Lipofectamine 3000. Specific overexpression of GPX4 was achieved by transfection of pcDNA3.1-GPX4 vector using Lipofectamine 3000 in TM4 cells. Briefly, TM4 cells were cultured in 6-well plates and transiently transfected with the siRNA or pcDNA3.1-GPX4 vector. After transfection, the TM4 cells were collected for subsequent experiments. Furthermore, TM4 cells were rinsed and incubated in serum-free medium for 30 min to remove any residual transferrin.

2.20. Molecular docking

The crystal structures of TfRC and chemical structure of MEHP were obtained from RCSB PDB database (https://www.rcsb.org) and PubChem database (http://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/), respectively. The protein–ligand docking study between TfRC and MEHP were based on these structures of compounds and was performed with AutoDock 4.2. Furthermore, the molecular docking results were further illustrated by using the PyMol molecular graphic program.

2.21. Transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) in sertoli cells

Mouse primary Sertoli cells were prepared and the TER was measured as described previously and described in detail in Supplementary 1.4 and 1.5 respectively. The TER was calculated through the formula: TER (Ω cm2) = (treatment resistance (Ω)-background resistance(Ω)) × membrane area (cm2).

2.22. Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism software (version 8.0). Data are mean ± SD of at least three independent experiments. Multiple groups were analyzed using one-way analysis of variance, followed by Tukey's post-hoc test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. DEHP caused impairment of BTB in sertoli cells

To explored the influence of DEHP on male reproductive system and the underlying mechanism, we performed an in vivo mouse model of the treatment with DEHP (Fig. 1A). We found that DEHP induced testicular atrophy and significantly decreased the organ coefficient of the mouse testis (Fig. 1B and S1A). The structures of the seminiferous tubules in the DEHP-treated groups were disrupted, loosened, disordered, or unclear. DEHP treatment increased the gap between seminiferous tubules and decreased the number of spermatogenic cell layers. Johnsen's score in the DEHP-treated groups was also significantly reduced compared with the Vcon group (Fig. 1C and D). Furthermore, DEHP treatment resulted in extensive mitochondrial vacuolation and mitochondrial cristae loss, and a large number of autophagic vesicles in mouse Sertoli cells (Fig. 1I).

Sertoli cells provide nutritional and physical support for germ cell development, which is tightly regulated by the sex hormones, estrogen, and androgens [36]. We next determined whether DEHP affects the function of Sertoli cells. Firstly, we evaluated the effect of DEHP on secretory function in Sertoli cells. Compared with the Vcon group, the levels of AR, ABP, CSF1, GDNF, INH-α, INH-β, SCF, and SOX9 were decreased, and the levels of CYP19, FSHR, GATA1, and transferrin were increased in the DEHP-treated groups (Fig. 1E and S3C). Then, we evaluated the effect of DEHP on BTB function in Sertoli cells. The typical “Sandwich” structure of BTB appeared intact in the Con and Vcon groups. In the DEHP-treated group, the vesicles, disintegration and fragmentation, and disappearance of circumferential actin bundles were observed at the BTB (Fig. 1F). The levels of AJ proteins (Integrin β1, N-cadherin, E-cadherin, α-catenin, β-catenin, γ-catenin), GJ protein (Cx43), TJ proteins (Claudin 5, Claudin 11, ZO-1, Occludin) and vimentin were decreased after exposure to DEHP (Fig. 1H and S3A-B). However, the level of p-Cx43 was increased after exposure to DEHP. Finally, we assessed the effect of DEHP on BTB integrity in Sertoli cells. The fluorescent signal was only detected in the interstitial and basal part of the testis, but it was not detected in the lumen of seminiferous tubules in the Con and Vcon groups. In the CdCl2 and DEHP treated groups, a large number of fluorescent signals crossed the BTB and diffused into the seminiferous tubule lumen (Fig. 1G). The male reproductive function depends on the production of sperm, and BTB integrity is vital for spermatogenesis [37]. The results showed that abnormal sperm morphology was observed in DEHP treated group, such as head deformities, folded tails and flagellar kinked. Meanwhile, the sperm malformation, TZI and SDI were also increased after exposure to DEHP. Aniline blue staining is used to evaluate sperm nuclear protein maturity (Fig. 1J and S1B-D). The data suggested that the sperm heads were stained with light blue by Aniline blue in the Con and Vcon groups, and were stained with purple by Aniline blue in the DEHP treatment groups. Collectively, these results suggests that DEHP causes functional damage to Sertoli cells, which has a negative consequence on the sperm production.

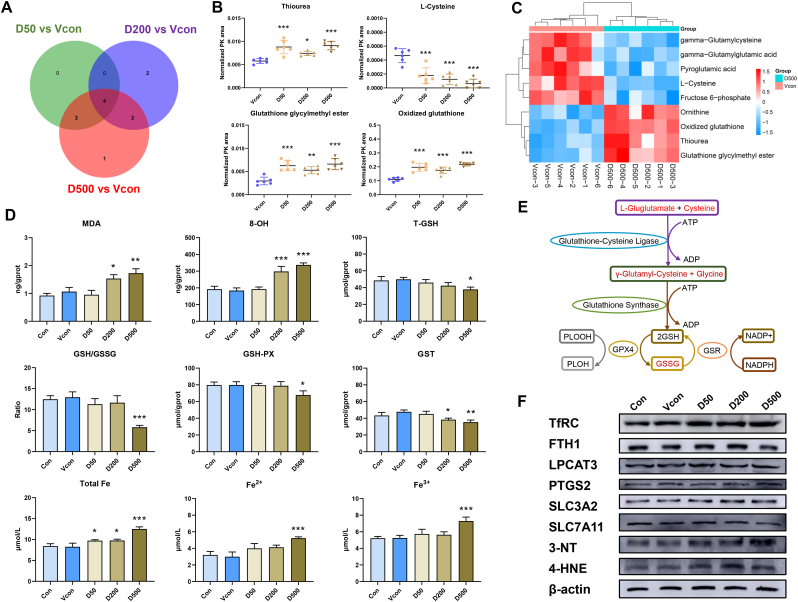

3.2. DEHP activates ferroptosis in the mouse sertoli cells

Although it is known that DEHP is implicated in cell death, including autophagy [38], apoptosis [39], and pyroptosis [40], to the best of our knowledge, the effect of DEHP on ferroptosis progression has not been investigated to date. Ferroptosis is characterized by changes in the morphological features of mitochondria. Consistently, we observed evident alterations in mitochondrial morphology (vacuolated mitochondria, loss of mitochondrial cristae, and presence of autophagic vesicles) in the DEHP-treated groups. Glutathione depletion and lipid peroxide accumulation are important features of ferroptosis [41]. GPX catalyzes GSH oxidation to oxidized GSH (GSSG), which is recycled back to reduced GSH using NADPH [42]. Next, we detected the levels of glutathione and oxidative stress biomarkers. The results showed that DEHP caused significant downregulation of T-GSH, GSH/GSSG, GSH-PX and GST levels (Fig. 2D). GSH is synthesized from l‐glutamate, l‐cysteine and glycine, by γ‐glutamyl‐cysteine and glutathione synthase. However, redox reactions are catalyzed by GSH-dependent enzymes including GSH‐PX and glutaredoxins [43]. The non-targeted metabolic profiling and Venn diagram analysis showed that DEHP affected glutathione metabolism system, and DEHP altered the levels of the four metabolites (thiourea, l-cysteine, glutathione glycylmethyl ester and oxidized glutathione) in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2A–C and E, and Figs. S2A–B). MDA serves as an index for reflecting lipid peroxide and 8-OH is a hallmark of oxidative stress-induced DNA damage. Consistently, we found that DEHP upregulated MDA and 8-OH levels (Fig. 2D). To further determine whether DEHP‐induced testicular damage in turn induces ferroptosis, we determined the levels of ferroptosis-related proteins. As mentioned above, 3-NT is a marker of oxidative stress owing to protein bound nitration and free tyrosine residues [44]. Furthermore, 4-HNE is the most abundant cytotoxic lipid oxidation product and has been extensively studied as marker of increased lipid peroxidation [45]. DEHP decreased SLC7A11 levels and increased the levels of TfRC, transferrin, 3-NT and 4-HNE (Fig. 2F, S3D and S4B).

Fig. 2.

DEHP promotes glutathione metabolism disorders and induces ferroptosis in mouse testes. (A) Venn diagram of metabolite profiling in the testes of mice exposed to D50, D200 and D500. (B) Thiourea, l-Cysteine, glutathione glycylmenthyl ester and oxidized glutathione are the three most significantly differential metabolites. (C) Heat map of metabolite profiling in testes of mice exposed to D50, D200 and D500. (D) T-GSH contents, the GSH/GSSG ratio, GSH-PX activity, GST activity, MDA content, 8-OH content, and total Fe, Fe2+ and Fe3+ contents of mouse testes. (E) Schematic diagram depicting the regulation of DEHP induced glutathione metabolism dysfunction in the testes of mice. (F) Levels of ferroptosis-related proteins in mouse testes; β-actin served as loading controls for the total fraction. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Symbol for the significance of differences between the Vcon group and another group: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Under normal conditions, iron is used by the cell, stored in ferritin or exported via ferroportin. The cell uses iron sensors via iron responsive proteins to downregulate TFRC and upregulate ferritin and ferroprtin to prevent iron accumulation in the cell. However, iron overload could induce ferroptosis through initiating severe lipid peroxidation [46]. To determine whether DEHP-induced transferrin delivered substantial amounts of Fe3+ iron to the cytosol to form Fe2+, we measured the cellular iron levels. Our results showed higher levels of total Fe, Fe3+, and Fe2+ in the DEHP-treated groups than in the Vcon group (Fig. 2D). These results demonstrate that DEHP might induce ferroptosis by activating TfRC in Sertoli cells.

3.3. MEHP induces functional injury in TM4 cells

DEHP is quantitatively metabolized in vivo to its monoester, MEHP [47]. In this study, the concentration of DEHP was low in the DEHP treatment groups, whereas the concentration of its metabolites significantly increased in the D500 group compared with the Vcon group (Fig. S2C). We also found that the MEHP content was much higher than that of other metabolites in the DEHP treatment groups, indicating that absorbed DEHP was rapidly metabolized into MEHP in the mouse testes. To further assess the effect of DEHP on Sertoli cells, we selected 100, 200 and 400 μM concentrations of MEHP for our subsequent experiments (Fig. 3A and B). In agreement with the in vivo experiment results, MEHP could cause mitochondrial vacuolation, mitochondrial cristae loss, and autophagic vesicles in TM4 cells. The mitochondrial average surface area and Flameng score suggested that MEHP disrupted the mitochondrial structure (Fig. 3C–E). MEHP also decreased the levels of AR, ABP, CSF1, GDNF, INH-α, INH-β, SCF and SOX9, and increased the levels of CYP19, FSHR, GATA1 and transferrin in TM4 cells (Fig. 3F–H and S4A). To further investigate the effect of MEHP on the BTB function of Sertoli cells, we completed the TER experiment. The result suggested that MEHP caused Sertoli cell barrier dysfunction (Fig. 3K). Further GSEA suggested that the cell junction and cell adhesion signaling pathways were downregulated (Fig. 3I–J and S5C), and KEGG pathway analysis identified gap junction and adherens junction pathway enrichment (Fig. 4C). These results suggest that MEHP induced structural and functional damage in TM4 cells.

Fig. 3.

MEHP induces structural and functional damage to TM4 cells. (A) TM4 cells were treated with MEHP. (B) The cell viability was assayed using CCK-8 after exposure to different concentrations of MEHP in TM4 cells. (C) Transmission electron microscopy analysis; yellow indicates mitochondria. (D) Determination of mitochondrial average surface area. (E) Flameng scores. (F) Heat map of relative mRNA levels of secretory dysfunction in TM4 cells. (G) Levels of AR, ABP, FSHR and Tf in TM4 cells; β-actin served as loading controls for the total fraction. (H) Quantitation of the protein expression of AR, ABP, FSHR and Tf in TM4 cells. (I) GSEA analysis revealed a decreased cell junction assembly signaling pathway. (J) GSEA analysis revealed a decreased cell junction organization assembly signaling pathway. (K) Changes of TER in SCs. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Symbol for the significance of differences between the DMSO group and another group: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

Fig. 4.

MEHP promotes glutathione metabolism disorders and induces ferroptosis in TM4 cells. (A) GO analysis based on RNA-sequencing results of TM4 cells after exposure to M400. (B) BP analysis based on RNA-sequencing results of TM4 cells after exposure to M400. (C) KEGG analysis based on RNA-sequencing results of TM4 cells after exposure to M400. (D) Heat map of relative mRNA levels of glutathione metabolism-related genes in M400-treated TM4 cells. (E) T-GSH contents, the GSH/GSSG ratio, GSH-PX activity, LPO contents, MDA contents, 8-OH contents in TM4 cells. (F) GSEA analysis revealed an increased ferroptosis assembly signaling pathway. (G) Levels of ferroptosis-related proteins in TM4 cells after exposure to M400; β-actin served as loading controls for the total fraction. (H) Lipid ROS, mitochondrial ROS, mitochondrial iron and intracellular iron level in TM4 cells. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Symbol for the significance of differences between the DMSO group and another group: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

3.4. MEHP causes glutathione metabolism disorder in TM4 cells

In consistent with in vivo results, GSEA suggested that the ferroptosis signaling pathway was upregulated based on RNA-seq of TM4 cells (Fig. 4F). Erastin is a small-molecule inducer of ferroptosis [48]. Fer-1 as a ferroptosis inhibitor suppresses ferroptosis by decreasing intracellular iron depletion by the iron chelator ROS production and lipid peroxidation [49], and DFO can suppresses ferroptosis [50]. To further elucidate the molecular mechanisms for DEHP-induced ferroptosis in Sertoli cells, TM4 cells were treated with Fer‐1, DFO and Erastin (Fig. 5A). Ultrastructural evaluation showed mitochondrial vacuolation, mitochondrial cristae loss, and autophagic vesicles in the Erastin and MEHP treatment groups, whereas these changes were reversed by Fer-1 treatment. The mitochondrial average surface area and Flameng score suggested that Erastin and MEHP disrupted the mitochondrial structure in TM4 cells, but Fer-1 treatment relieved these changes (Fig. 5B). KEGG analysis of TM4 cells also identified glutathione metabolism pathway enrichment (Fig. 4C). The 23 differentially expressed mRNAs related to glutathione metabolism identified through transcriptomic sequencing after MEHP exposure are presented as a cluster heat map in Fig. 4D. Furthermore, MEHP significantly reduced GSH, the GSH to GSSG ratio, and GPH-PX activities compared with the Vcon group, but Fer-1 restored these effects (Fig. 4, Fig. 5C). An important Nrf2 downstream target relevant for ferroptosis is GPX4, thus we also detected the level of Nrf2 proteins. The result showed that DEHP could increase the level Nrf2 and GPX4 proteins in mouse testicular tissue (Fig. S4C). However, MEHP did not change the level Nrf2 protein in TM4 cells (Fig. S5B). DFO was able to partially relieve MEHP-induced the reduction of GPX4 level (Figs. S7A–C). Overall, these results demonstrated that MEHP induced glutathione metabolism disorders, which are vital hallmarks of ferroptosis.

Fig. 5.

Fer-1 inhibits MEHP- induced ferroptosis in TM4 cells. (A) TM4 cells were treated with Fer-1 and DFO, Erastin, or M400; their cell viability was assayed using a CCK8 assay (B) Transmission electron microscopy analysis, mitochondrial average surface area measurement, and Flameng scorea of the treated TM4 cells; yellow indicates mitochondria; green indicates autophagic vacuole. (C) T-GSH contents, the GSH/GSSG ratio, GSH-PX activity, LPO contents, MDA contents, and 8-OH content of TM4 cells. (D) Intracellular and lipid ROS production of TM4 cells. (E) Mitochondrial ROS production of TM4 cells. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Symbol for the significance of differences between the DMSO group and another group: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Symbol for the significance of differences between the MEHP groups and Fer-1 + M400 group groups: ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

3.5. MEHP accelerates ROS generation and lipid peroxidation

A decline in glutathione synthesis can increase oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation, which are the drivers of ferroptosis [51]. Consistently, GO pathway analysis of TM4 cells also identified oxidative stress pathway enrichment (Fig. 4A–B). Therefore, we next determined intracellular and mitochondrial ROS levels and lipid peroxidation intensity in TM4 cells using fluorescence microscopy. A more pronounced positivity for intracellular and mitochondrial ROS and lipid peroxidation was detected in the Erastin and MEHP treated TM4 cells (Figs. 4H, 5D-E and S6A-B). MDA was formed as the end product of LPO and served as an index of LPO intensity. Consistently, the levels of LPO, MDA and 8-OH were also increased in Erastin and MEHP-treated groups compared with the Vcon group, whereas Fer-1 alleviated these effects (Fig. 4, Fig. 5C). Furthermore, 4-HNE level was elevated after exposure to Erastin and MEHP, however, Fer-1 treatment reversed this increase (Fig. 4, Fig. 6B). These results showed that MEHP accelerated lipid peroxidation and then drove the process of ferroptosis in TM4 cells.

Fig. 6.

Fer-1 and DFO inhibit MEHP-induced change in iron levels in TM4 cells. (A) Expression of ferroptosis-related proteins in TM4 cells, β-actin served as loading controls for the total fraction. (B) Quantitation of the protein expression of ferroptosis-related proteins in TM4 cells. (C) Intracellular iron level of TM4 cells. (D) Intracellular iron level in TM4 cells. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Symbol for the significance of differences between the DMSO group and another group: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Symbol for the significance of differences between the MEHP groups and Fer-1/DFO + M400 group groups: #P < 0.05, ###P < 0.001.

3.6. MEHP indues ferroptosis by promoting TfRC-mediated iron transport

We further determined the levels of proteins related to ferroptosis in TM4 cells. SLC7A11 and GPX4 levels were reduced, and transferrin and TfRC was the most significantly upregulated protein following MEHP exposure. Fer-1 treatment reversed these changes (Fig. 6A–B and S5A). TfRC delivers iron to the cytosol to form Fe2+, which then accumulates in the mitochondria and cytoplasm, eventually inducing ferroptosis. To verify whether transferrin regulates iron level in TM4 cells following MEHP exposure, we detected intracellular and mitochondrial Fe2+ levels using FerroOrange and Mito‐FerroGreen probes, respectively. TM4 cells treated with Erastin and MEHP showed a robust increase in FerroOrange and Mito-FerroGreen signals, indicating a rapid increase in intracellular and mitochondrial Fe2+ levels, respectively. However, DFO rescued MEHP-induced ferroptosis (Fig. 6C–D, and S6C-D). Furthermore, DFO could reverse cell viability of TM4 cells to some extent, but did not bring it back to normal level (Fig. S7D). These results indicate that TfRC might play a critical regulatory role in MEHP-induced ferroptosis.

3.7. TfRC knockdown inhibits MEHP-induced ferroptosis in TM4 cells

Ferroptosis was induced following ablation of TfRC, which led to iron accumulation [11]. We found that the TfRC level were substantially increased after exposure to DEHP. To confirm the role of TfRC in mediating DEHP-induced ferroptosis, we used siTfRC in our experiments (Fig. 7A and C-D). Compared with the M400 group, the result showed that the TM4 cell viability was mitigated after siTfRC treatment (Fig. 7B). Then, we found that siTfRC prevented the MEHP-induced decrease in T-GSH, GSH/GSSG and GSH-PX levels, and increase in LPO, MDA and 8-OH levels (Fig. 7F). siTfRC effectively blocked the increase in lipid peroxidation and ROS generation in TM4 cells, and alleviated ferroptosis (Fig. 7E and S8A-B). The extracellular complex formed by transferrin and Fe3+ binds to the TfRC, Fe3+ is converted to Fe2+, and Fe2+ is transported into the cytoplasm for utilization. Excessive amounts of Fe2+ trigger ferroptosis via Fenton reactions with the accumulation of ROS [52]. Consistent with the results of DFO treatment, siTfRC reduced FerroOrange and Mito-FerroGreen signals, indicating a rapid decrease in intracellular and mitochondrial Fe2+ levels (Fig. 7E and S8C-D). To verify the potential interaction between MEHP and TfRC at the molecular level, we performed the protein–ligand docking analysis. The binding free energy of docking pattern was 6.02 kcal/mol, indicating stable combination (Fig. 7H). The result indicates there is strong interaction between MEHP and TfRC. Downregulating TfRC abolished MEHP-induced ferroptosis by reducing Fe2+ levels in the cytoplasm and mitochondria (Fig. 7I). To investigate the role of TfRC on the function of Sertoli cells, we completed the TER experiment. TER analysis suggested that siTfRC reversed MEHP-induced Sertoli cell barrier dysfunction (Fig. 7G). These results indicate that TfRC can uniquely suppress ferroptosis by reducing the cellular and mitochondrial iron content.

Fig. 7.

TfRC knockdown inhibits MEHP-induced ferroptosis in TM4 cells. (A) TM4 cells were treated with siTfRC and/or M400. (B) The cell viability was assayed using a CCK8 assay. (C) Levels of TfRC in TM4 cells. (D) Quantitation of the protein expression of TfRC. (E) Intracellular and lipid ROS generation; mitochondrial ROS; intracellular iron level; mitochondrial iron level. (F) T-GSH contents, the GSH/GSSG ratio, GSH-PX activity, LPO contents, MDA contents, and 8-OH content, T-AOC activity, T-SOD activity and CAT activity. (G) Changes of TER in SCs. (H) Molecular docking simulation for the ligand–protein binding of MEHP with TfRC. (I) Schematic diagram depicting the regulation of MEHP-induced ferroptosis by increasing TfRC level in Sertoli cells. Data are presented as the mean ± SD (n = 3). Symbol for the significance of differences between the DMSO group and another group: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. Symbol for the significance of differences between the siNC + M400 group and siTf + M400 group: #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001.

To further demonstrate whether DEHP facilitates iron import in cells via disrupting membrane integrity or other mechanism, we used siTf in the subsequent experiments (Figs. S11A and I). The result showed that Tf knockdown could not reverse MEHP-inhibited cell viability of TM4 cells (Fig. S11E). Tf knockdown also could not antagonized MEHP-induced decrease in T-GSH, GSH/GSSG and GSH-PX levels and increase in LPO, MDA and 8-OH levels (Figs. S11B–D and F–H). Furthermore, Tf knockdown did not inhibited lipid peroxidation, ROS generation, and increase in Fe2+ levels (Fig. S11J-M). Therefore, the result also suggested that TfRC-promoted transport of the iron represents a vital mechanism in DEHP-induced ferroptosis.

Finally, to further confirm the specificity of the TfRC in MEHP-induced ferroptosis, we perform a series of experiments using NAC or GPX4 overexpression vector (Fig. S9A, I and S10A, I). The NAC or GPX4 overexpression capable of reversing cell viability of TM4 cells to some extent, but did not bring it back to normal level (Figs. S9E and S10E). Then, NAC or GPX4 overexpression migrated the MEHP-induced reduction in T-GSH, GSH/GSSG and GSH-PX levels (Figs. S9B–D and S10B-D), and up-regulated in LPO, MDA and 8-OH levels (Figs. S9F–H and S10F–H). NAC or GPX4 overexpression inhibited lipid peroxidation, ROS generation, and intracellular and mitochondrial Fe2+ levels (Fig. S9J-M and S10J-M). However, NAC or overexpression GPX4 did not bring them back to normal level. Collectively, these data reveal that ferroptosis is important for DEHP-induced BTB dysfunction in Sertoli cells via targeting TfRC (Fig. 8 and Graphical Abstract).

Fig. 8.

DEHP promotes ferroptosis by targeting TfRC in Sertoli cells, thereby inducing BTB dysfunction.

4. Discussion

Phthalate, an endocrine disrupter, is a global contaminant with definite reproductive toxicity [[53], [72]]. Phthalates are known to have potential harmful effects on the ecosystem functionality and public health, and many studies have assessed its reproductive toxic effects. A recent report showed that phthalate exposure at levels seen in human populations have male reproductive system adverse effects, particularly DEHP [54]. Phthalates could induce changes in puberty, the development of testicular dysgenesis syndrome, cancer, and fertility disorders in males [55]. However, the underlying mechanism of phthalates-induced male reproductive injury remains unclear. Thus, we conducted the present study to further evaluate phthalates toxicity in mouse testes and to investigate its possible mechanisms. The importance of ferroptosis in male reproductive injury has been well-documented [56]. However, the biological link between phthalate-induced testicular damage and ferroptosis remains to be elucidated. In our study, we found that DEHP caused mouse testicular Sertoli cell BTB and secretory dysfunction in Sertoli cells. Next, we showed that DEHP induced ferroptosis by activating TfRC-mediated iron transport. Moreover, TfRC downregulation effectively inhibited DEHP-induced iron starvation response in Sertoli cells, thereby alleviating BTB dysfunction. This study indicated that TfRC might act as a potential therapeutic target for attenuating phthalate-induced male reproductive disorders.

DEHP is known to exert its male reproductive toxicity through a range of molecular mechanisms, including synthesis disorders and sperm production disorders [[57], [75]]. In the present study, we found that DEHP caused vacuolated mitochondria, mitochondrial cristae loss, and autophagic vesicles in Sertoli cells, which are the somatic cells of the testis that are necessary for testis formation and spermatogenesis [58]. These data suggested that DEHP affected the secretory function of Sertoli cells and the change of integrity in BTB. The BTB and secretory functions of Sertoli cells are essential for the maintenance of spermatogenesis and male fertility [59]. Consistently, these data proved that DEHP induced increases in sperm deformity and sperm protein damage, suggesting that DEHP-induced testicular toxicity is correlated with damage to Sertoli cells.

The alteration in mitochondrial morphology is an obvious feature of ferroptosis and might show that the cells die undergoing ferroptosis [60]. These results suggest that DEHP might drive the occurrence of ferroptosis. The primary hallmarks of ferroptosis include GSH depletion and lipid peroxidation [61]. We found that DEHP induced glutathione metabolism disorder, including glutathione metabolite changes, and glutathione content and related enzyme decline. Disorder in the glutathione system leads to enhanced lipid peroxidation that can result in GSH consumption [62]. In corroboration with other studies, we have shown that DEHP causes DNA oxidative damage and increases lipid peroxidation. Furthermore, DEHP also increases iron levels including total Fe, Fe3+, and Fe2+ in the mouse testis. Herein, we propose that the DEHP-induced increase in iron could intensify cellular oxidative stress and induce lipid peroxidation, eventually causing ferroptosis.

Based on the metabolic pathway, DEHP in the first step forms MEHP, which is the most important metabolite in vivo [63]. We then explored how DEHP activates the iron starvation response. Thus, we used MEHP for Sertoli cell culture. Consistent with the in vivo results, we found that MEHP also affected the BTB and secretory function of Sertoli cells. Moreover, MEHP induced a mass of vacuolated mitochondria, loss of mitochondrial cristae, and autophagic vesicles in TM4 cells. This raises the possibility that transferrin may act as a probable target for mediating DEHP-induced ferroptosis in Sertoli cells. Erastin triggers ferroptosis by direct inhibition of the cystine/glutamate antiporter system [64]. We observed that MEHP substantially contributed to the rapid depletion of glutathione and related enzymes. RNA-seq analysis of TM4 cells also revealed that MEHP induced glutathione system dysregulation and related gene changes. These results are the major hallmarks of ferroptosis.

Erastin induces ferroptosis by increasing intracellular iron. We also found that MEHP substantially increased mitochondrial and intracellular Fe2+ levels, which may mediate MEHP-induced transferrin upregulation. Iron overload subsequently intensifies the cellular oxidative stress and induces lipid peroxidation [65]. The present study showed that MEHP potentiated DNA oxidative damage, mitochondrial and intracellular ROS generation, and lipid peroxidation. Iron metabolism-related proteins are crucial for the study of ferroptosis [[66], [73], [74]]. Therefore, we explored other related proteins or regulators of ferroptosis. Likewise, MEHP partially altered ferroptosis-related proteins including SLC7A11, GPX4, transferrin and TfRC. Despite this, the mechanism by which DEHP induces ferroptosis in Sertoli cells remain largely unknown.

As a specific ferroptosis marker, TfRC was the most prominently upregulated protein after DEHP and MEHP exposure. In the circulation, TfRC binds to Fe3+ to deliver iron to the testes and other tissues. The resulting transferrin-TfRC complex is internalized, causing the release of iron from TfRC and the transfer of iron to the cytosol to form Fe2+. An increase in unstable iron pools induces oxidative stress, ultimately causing ferroptosis [67]. These results proved that DEHP-induced TfRC transports abundant iron to the mouse testicular tissue and results in the formation of Fe2+, which further caused Fenton's reaction, driving ferroptosis. Taken together, these results provide clear evidence that TfRC might mediates DEHP-induced ferroptosis in the mouse testes. We hypothesized that TfRC might mediate iron starvation response and investigated whether TfRC acts as a potential target for mediating DEHP-induced ferroptosis in Sertoli cells. Herein, gene silencing with siRNA and molecular docking was performed to determine whether MEHP-induced ferroptosis was dependent on TfRC expression. Consistent with ferroptosis inhibition treatment, TfRC downregulation reversed MEHP-induced the decrease of cell viability. The results showed that TfRC downregulation inhibited intracellular and mitochondrial translocation of a large amount of Fe2+ after MEHP exposure in TM4 cells. We also found that MEHP-induced effects on glutathione content and glutathione-related enzyme activities were partially relieved by TfRC downregulation thereby decreasing lipid peroxidation generation. These results suggest that TfRC downregulation abrogated iron overload and subsequently relieved cellular oxidative stress and lipid peroxidation. Epidemiologic studies have suggested that excessive iron intake or high iron status can be detrimental to reproductive system and is related with the clinical expressions of many reproductive disorders, characterized by a dysregulation in iron homeostasis leading to excessive ferroptosis. We found that TfRC uniquely inhibit DEHP-induced ferroptosis and thus reversed Sertoli cell barrier dysfunction.

GPX4 is a phospholipid hydroperoxide glutathione peroxidase, and lipid peroxide is eliminated by GPX4 and its cofactor GSH [[68], [71]]. GPX4 is also a transcription target of Nrf2, which may cause increased GPX4 level and thus more resistance to ferroptosis [[69], [70]]. We found that MEHP decreased the level of GPX4 and did not change the level of Nrf2 in Sertoli cells, suggesting that the change of GPX4 level is not entirely regulated by Nrf2. Of note, NAC or overexpression GPX4 partially restored the glutathione system and eliminate lipid peroxide, but did not bring it back to normal level. Taken together, our results suggest that TfRC inhibition could represent a potential treatment for ferroptosis, and endocrine disruptor-induced male reproductive injury.

In conclusion, our findings suggest that MEHP induces ferroptosis by TfRC-mediated iron accumulation and glutathione metabolism disorders, which eventually leads to BTB dysfunction. Our results offer unique insights into the importance of TfRC. Given the potential role of TfRC in Sertoli cells and that TfRC is a specific marker of ferroptosis, the results presented herein offer a novel mechanism by which TfRC inhibition may prevent both the initiation and progression of ferroptosis, particularly in plasticizer-induced male reproductive disorders. These data suggest a potential new therapeutic strategy for endocrine disruptor-induced reproductive diseases. Such a paradigm not only presents an effective prevention strategy for ferroptosis, but also provides a useful iron-regulation method to relieve phthalate-induced male reproductive injury. In summary, we identified the mechanism of a previously unrecognized ferroptosis-regulating function of phthalates.

CRediT author contribution statement

Yi Zhao: Performed experiments, writing-original draft, editing and formal analysis. Xue-Nan Li, Jia-Gen Cui and Hao Zhang: Data curation. Hao-Ran Wang, Jia-Xin Wang and Ming-Shan Chen: Visualization. Jin-Long Li: Supervision, project administration and funding acquisition.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This study has received assistance from National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 32172932), Key Program of Natural Science Foundation of Heilongjiang Province of China (No. ZD2021C003), China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA (No. CARS-35), Distinguished Professor of Longjiang Scholars Support Project (No. T201908) and Heilongjiang Touyan Innovation Team Program. Some Figs created with BioRender.com.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.redox.2022.102584.

Abbreviations

- DEHP

di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate

- Tf

transferrin

- TFRC

Transferrin receptor

- BTB

blood-testis barrier dysfunction

- AR

androgen receptor

- ABP

androgen-binding protein

- FSHR

follicle-stimulating hormone receptor

- FSH

follicle-stimulating hormone

- MEHP

mono(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate

- RNA-seq

RNA-sequencing

- NEAU

Northeast Agricultural University

- H&E

Hematoxylin-eosin

- MEHHP

mono(2-ethyl-5-hydroxyhexyl) phthalate

- MEOHP

rac mono(2-ethyl-5-oxohexyl) Phthalate

- 2cx MMHP

mono[2-(carboxymethyl)hexyl] phthalate

- NAC

-Acetyl-l-cysteine

- T-GSH

total glutathione

- GSH

glutathione

- GSSG

glutathione oxidized

- GSH-PX

glutathione peroxidase

- GST

glutathione S-transferase

- MDA

malondialdehyde

- 8-OH

8-hydroxyguanine

- LPO

lipid peroxidation

- 3-NT

3-nitrotyrosine

- 4-HNE

4-hydroxynonenal

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- RT-PCR

reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction

- ATCC

American Type Culture Collection

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- DFO

deferoxamine

- Fer-1

ferrostatin-1

- CCK-8

Cell Counting Kit-8

- SD

standard deviation

- CSF1

colony-stimulating factor 1

- GDNF

Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor

- INH-α

inhibin alpha

- INH-β

inhibin beta

- SCF

stem cell factor

- SOX9

Sry-related HMG box-9

- CYP19

cytochrome P450 aromatase

- GATA1

GATA binding protein 1

- Tf

transferrin

- SLC7A11

solute carrier family 7 membrane 11

- SLC3A2

solute carrier family 3 membrane 2

- ROS

reactive oxide species

- FTH1

ferritin heavy chain

- LPCAT3

lysophosphatidylcholine acyltransferase 3

- PTGS2

Cyclooxygenase-2

- GPX4

glutathione peroxidase 4

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Ferguson K.K., McElrath T.F., Meeker J.D. Environmental phthalate exposure and preterm birth. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168:61–67. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.3699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Diamanti-Kandarakis E., Bourguignon J.P., Giudice L.C., Hauser R., Prins G.S., Soto A.M., Zoeller R.T., Gore A.C. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: an Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocr. Rev. 2009;30:293–342. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhou Y., Wang H., Chen Y., Jiang Q. Environmental and food contamination with plasticisers in China. Lancet. 2011;378:e4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61700-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.IHS, Plasticizers 2021. https://ihsmarkit.com/products/plasticizers-chemical-economics-handbook.html Online Published May.

- 5.Dai Y.X., Zhu S.Y., Chen J., Li M.Z., Talukder M., Li J.L. Role of Toll-like Receptor/MyD88 Signaling in Lycopene Alleviated Di-2-ethylhexyl Phthalate (DEHP)-Induced Inflammatory Response. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022;70:10022–10030. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.2c03864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.-.B.-d.a. United States Environmental Protection Agency; Office of Chemical Safety and Pollution Prevention. Proposed Designation of Di-ethylhexyl Phthalate (DEHP) (1, 1,2-bis (2-ethylhexyl) Ester) (CASRN 117-81-7) as a High-Priority Substance for Risk Evaluation. 2019. pp. 1–59. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhao Y.X., Tang Y.X., Sun X.H., Zhu S.Y., Dai X.Y., Li X.N., Li J.L. Gap Junction Protein Connexin 43 as a Target Is Internalized in Astrocyte Neurotoxicity Caused by Di-(2-ethylhexyl) Phthalate. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2022;70:5921–5931. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.2c01635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cui J.G., Zhao Y., Zhao H., Li X.N. Lycopene regulates the mitochondrial unfolded protein response to prevent DEHP-induced cardiac mitochondrial damage in mice. Food Funct. 2022;13:4527–4536. doi: 10.1039/d1fo03054j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang X., Stockwell B.R., Conrad M. Ferroptosis: mechanisms, biology and role in disease. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2021;22:266–282. doi: 10.1038/s41580-020-00324-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Richardson D.R. Mysteries of the transferrin-transferrin receptor 1 interaction uncovered. Cell. 2004;116:483–485. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00165-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ding H., Chen S., Pan X., Dai X., Pan G., Li Z., Mai X., Tian Y., Zhang S., Liu B., Cao G., Yao Z., Yao X., Gao L., Yang L., Chen X., Sun J., Chen H., Han M., Yin Y., Xu G., Li H., Wu W., Chen Z., Lin J., Xiang L., Hu J., Lu Y., Zhu X., Xie L. Transferrin receptor 1 ablation in satellite cells impedes skeletal muscle regeneration through activation of ferroptosis. J. Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle. 2021;12:746–768. doi: 10.1002/jcsm.12700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu Y., Jiao H., Yue Y., He K., Jin Y., Zhang J., Zhang J., Wei Y., Luo H., Hao Z., Zhao X., Xia Q., Zhong Q., Zhang J. Ubiquitin ligase E3 HUWE1/MULE targets transferrin receptor for degradation and suppresses ferroptosis in acute liver injury. Cell Death Differ. 2022;29:1705–1718. doi: 10.1038/s41418-022-00957-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng E.L., Cardle, Kacherovsky N., Bansia H., Wang T., Zhou Y., Raman J., Yen A., Gutierrez D., Salipante S.J., des Georges A., Jensen M.C., Pun S.H. Discovery of a transferrin receptor 1-binding aptamer and its application in cancer cell depletion for adoptive T-cell therapy manufacturing. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022;144:13851–13864. doi: 10.1021/jacs.2c05349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kloner R.A., Carson C., Dobs A., 3rd, Kopecky S., Mohler E.R., 3rd Testosterone and cardiovascular disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2016;67:545–557. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mruk D.D., Cheng C.Y. The mammalian blood-testis barrier: its biology and regulation. Endocr. Rev. 2015;36:564–591. doi: 10.1210/er.2014-1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng C.Y., Mruk D.D. The blood-testis barrier and its implications for male contraception. Pharmacol. Rev. 2012;64:16–64. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.002790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Emes R.D., Riley M.C., Laukaitis C.M., Goodstadt L., Karn R.C., Ponting C.P. Comparative evolutionary genomics of androgen-binding protein genes. Genome Res. 2004;14:1516–1529. doi: 10.1101/gr.2540304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tapanainen J.S., Aittomaki K., Min J., Vaskivuo T., Huhtaniemi I.T. Men homozygous for an inactivating mutation of the follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) receptor gene present variable suppression of spermatogenesis and fertility. Nat. Genet. 1997;15:205–206. doi: 10.1038/ng0297-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zalata A., Hafez T., Schoonjans F., Comhaire F. The possible meaning of transferrin and its soluble receptors in seminal plasma as markers of the seminiferous epithelium. Hum. Reprod. 1996;11:761–764. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a019250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hoyes K.P., Morris I.D., Hendry J.H., Sharma H.L. Transferrin-mediated uptake of radionuclides by the testis. J. Nucl. Med. 1996;37:336–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng H., Schorpp K., Jin J., Yozwiak C.E., Hoffstrom B.G., Decker A.M., Rajbhandari P., Stokes M.E., Bender H.G., Csuka J.M., Upadhyayula P.S., Canoll P., Uchida K., Soni R.K., Hadian K., Stockwell B.R. Transferrin receptor is a specific ferroptosis marker. Cell Rep. 2020;30:3411–3423. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.02.049. e3417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhao Y., Cui L.G., Li J., Talukder M., Cui J.G., Zhang H., Li J.L. Lycopene prevents DEHP-induced testicular endoplasmic reticulum stress via regulating nuclear xenobiotic receptors and unfolded protein response in mic. Food Funct. 2021;12:12256–12264. doi: 10.1039/d1fo02729h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heudorf U., Mersch-Sundermann V., Angerer J. Phthalates: toxicology and exposure. Int. J. Hyg Environ. Health. 2007;210:623–634. doi: 10.1016/j.ijheh.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Du Z.H., Xia J., Sun X.C., Li X.N., Zhang C., Zhao H.S., Zhu S.Y., Li J.L. A novel nuclear xenobiotic receptors (AhR/PXR/CAR)-mediated mechanism of DEHP-induced cerebellar toxicity in quails (Coturnix japonica) via disrupting CYP enzyme system homeostasis. Environ. Pollut. 2017;226:435–443. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2017.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang H., Zhao, J.G. Cui, X.N. Li, J.L. Li Y. DEHP-induced mitophagy and mitochondrial damage in the heart are associated with dysregulated mitochondrial biogenesis. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022;161:112818. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2022.112818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao Y., Li X.N., Zhang H., Cui J.G., Wang J.X., Chen M.S., Li J.L. Phthalate-induced testosterone/androgen receptor pathway disorder on spermatogenesis and antagonism of lycopene. J. Hazard Mater. 2022;439 doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2022.129689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zolfaghari M., Drogui P., Seyhi B., Brar S.K., Buelna G., Dube R. Occurrence, fate and effects of Di (2-ethylhexyl) Phthalate in wastewater treatment plants: a review. Environ. Pollut. 2014;194:281–293. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2014.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mallow E.B., Fox M.A. Phthalates and critically ill neonates: device-related exposures and non-endocrine toxic risks. J. Perinatol. 2014;34:892–897. doi: 10.1038/jp.2014.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Killian J.K., Dorssers L.C., Trabert B., Gillis A.J., Cook M.B., Wang Y., Waterfall J.J., Stevenson H., Smith W.I., Jr., Noyes N., Retnakumar P., Stoop J.H., Oosterhuis J.W., Meltzer P.S., McGlynn K.A., Looijenga L.H. Imprints and DPPA3 are bypassed during pluripotency- and differentiation-coupled methylation reprogramming in testicular germ cell tumors. Genome Res. 2016;26:1490–1504. doi: 10.1101/gr.201293.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fernandez-Del-Rio L., Rodriguez-Lopez S., Gutierrez-Casado E., Gonzalez-Reyes J.A., Clarke C.F., Buron M.I., Villalba J.M. Regulation of hepatic coenzyme Q biosynthesis by dietary omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids. Redox Biol. 2021;46 doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2021.102061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Li T., Liu Z., Zhang X., Chen X., Wang S. Therapeutic effectiveness of type I interferon in vulvovaginal candidiasis. Microb. Pathog. 2019;134 doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2019.103562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu J.B., Li Z.F., Lu L., Wang Z.Y., Wang L. Glyphosate damages blood-testis barrier via NOX1-triggered oxidative stress in rats: long-term exposure as a potential risk for male reproductive health. Environ. Int. 2022;159 doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2021.107038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wu T., Hu E., Xu S., Chen M., Guo P., Dai Z., Feng T., Zhou L., Tang W., Zhan L., Fu X., Liu S., Bo X., Yu G. clusterProfiler 4.0: a universal enrichment tool for interpreting omics data. Innovation. 2021;2 doi: 10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dai Y., Tian Q., Si J., Sun Z., Shali S., Xu L., Ren D., Chang S., Dong X., Zhao H., Mei Z., Zheng Y., Ge J. Circulating metabolites from the choline pathway and acute coronary syndromes in a Chinese case-control study. Nutr. Metab. 2020;17:39. doi: 10.1186/s12986-020-00460-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chang Y.J., Lin K.L., Chang Y.Z. Determination of Di-(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (DEHP) metabolites in human hair using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Clin. Chim. Acta. 2013;420:155–159. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wu S., Yan M., Ge R., Cheng C.Y. Crosstalk between Sertoli and germ cells in male fertility. Trends Mol. Med. 2020;26:215–231. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2019.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pang J., Feng X., Liang Q., Zheng X., Duan Y., Zhang X., Zhang J., Chen Y., Fan K., Gao L., Li J. Ferritin-nanocaged ATP traverses the blood-testis barrier and enhances sperm motility in an asthenozoospermia model. ACS Nano. 2022;16:4175–4185. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.1c10029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun Y., Shen J., Zeng L., Yang D., Shao S., Wang J., Wei J., Xiong J., Chen J. Role of autophagy in di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP)-induced apoptosis in mouse Leydig cells. Environ. Pollut. 2018;243:563–572. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2018.08.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhao Y., Li H.X., Luo Y., Cui J.G., Talukder M., Li J.L. Lycopene mitigates DEHP-induced hepatic mitochondrial quality control disorder via regulating SIRT1/PINK1/mitophagy axis and mitochondrial unfolded protein response. Environ. Pollut. 2022;292:118390. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.118390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dai X.Y., Li X.W., Zhu S.Y., Li M.Z., Zhao Y., Talukder M., Li Y.H., Li J.L. Lycopene ameliorates di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate-induced pyroptosis in spleen via suppression of classic caspase-1/NLRP3 pathway. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021;69:1291–1299. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c06534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Riegman M., Sagie L., Galed C., Levin T., Steinberg N., Dixon S.J., Wiesner U., Bradbury M.S., Niethammer P., Zaritsky A., Overholtzer M. Ferroptosis occurs through an osmotic mechanism and propagates independently of cell rupture. Nat. Cell Biol. 2020;22:1042–1048. doi: 10.1038/s41556-020-0565-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yan X., Zhang X., Wang L., Zhang R., Pu X., Wu S., Li L., Tong P., Wang J., Meng Q.H., Jensen V.B., Girard L., Minna J.D., Roth J.A., Swisher S.G., Heymach J.V., Fang B. Inhibition of thioredoxin/thioredoxin reductase induces synthetic lethality in lung cancers with compromised glutathione homeostasis. Cancer Res. 2019;79:125–132. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-1938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rushworth G.F., Megson I.L. Existing and potential therapeutic uses for N-acetylcysteine: the need for conversion to intracellular glutathione for antioxidant benefits. Pharmacol. Ther. 2014;141:150–159. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu L., Li S., Liu W., Chen J., Yu Q., Zhang Z., Li Y., Liu J., Chen X. Real time detection of 3-nitrotyrosine using smartphone-based electrochemiluminescence. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021;187 doi: 10.1016/j.bios.2021.113284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dalleau S., Baradat M., Gueraud F., Huc L. Cell death and diseases related to oxidative stress: 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE) in the balance. Cell Death Differ. 2013;20:1615–1630. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2013.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fernandez-Real J.M., Manco M. Effects of iron overload on chronic metabolic diseases. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2014;2:513–526. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(13)70174-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim B.N., Cho S.C., Kim Y., Shin M.S., Yoo H.J., Kim J.W., Yang Y.H., Kim H.W., Bhang S.Y., Hong Y.C. Phthalates exposure and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in school-age children. Biol. Psychiatr. 2009;66:958–963. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.07.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bao Z., Hua L., Ye Y., Wang D., Li C., Xie Q., Wakimoto H., Gong Y., Ji J. MEF2C silencing downregulates NF2 and E-cadherin and enhances Erastin-induced ferroptosis in meningioma. Neuro Oncol. 2021;23:2014–2027. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/noab114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li W., Feng G., Gauthier J.M., Lokshina I., Higashikubo R., Evans S., Liu X., Hassan A., Tanaka S., Cicka M., Hsiao H.M., Ruiz-Perez D., Bredemeyer A., Gross R.W., Mann D.L., Tyurina Y.Y., Gelman A.E., Kagan V.E., Linkermann A., Lavine K.J., Kreisel D. Ferroptotic cell death and TLR4/Trif signaling initiate neutrophil recruitment after heart transplantation. J. Clin. Invest. 2019;129:2293–2304. doi: 10.1172/JCI126428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wu T., Liang X., Liu X., Li Y., Wang Y., Kong L., Tang M. Induction of ferroptosis in response to graphene quantum dots through mitochondrial oxidative stress in microglia, Part. Fibre Toxicol. 2020;17:30. doi: 10.1186/s12989-020-00363-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Brault C., Levy P., Duponchel S., Michelet M., Salle A., Pecheur E.I., Plissonnier M.L., Parent R., Vericel E., Ivanov A.V., Demir M., Steffen H.M., Odenthal M., Zoulim F., Bartosch B. Glutathione peroxidase 4 is reversibly induced by HCV to control lipid peroxidation and to increase virion infectivity. Gut. 2016;65:144–154. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-307904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Li Y., Xiu W., Yang K., Wen Q., Yuwen L., Luo Z., Liu X., Yang D., Xie X., Wang L. A multifunctional Fenton nanoagent for microenvironment-selective anti-biofilm and anti-inflammatory therapy. Mater. Horiz. 2021;8:1264–1271. doi: 10.1039/d0mh01921f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Q., Sun Y., Zhang Q., Hou J., Wang P., Kong X., Sundell J. Phthalate exposure in Chinese homes and its association with household consumer products. Sci. Total Environ. 2020;719 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.136965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Radke E.G., Braun J.M., Meeker J.D., Cooper G.S. Phthalate exposure and male reproductive outcomes: a systematic review of the human epidemiological evidence. Environ. Int. 2018;121:764–793. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2018.07.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mariana M., Feiteiro J., Verde I., Cairrao E. The effects of phthalates in the cardiovascular and reproductive systems: a review. Environ. Int. 2016;94:758–776. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ghoochani A., Hsu E.C., Aslan M., Rice M.A., Nguyen H.M., Brooks J.D., Corey E., Paulmurugan R., Stoyanova T. Ferroptosis inducers are a novel therapeutic approach for advanced prostate cancer. Cancer Res. 2021;81:1583–1594. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-20-3477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Foster P.M., Mylchreest E., Gaido K.W., Sar M. Effects of phthalate esters on the developing reproductive tract of male rats. Hum. Reprod. Update. 2001;7:231–235. doi: 10.1093/humupd/7.3.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Heinrich A., Potter S.J., Guo L., Ratner N., DeFalco T. Distinct roles for Rac1 in Sertoli cell function during testicular development and spermatogenesis. Cell Rep. 2020;31 doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2020.03.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Griswold M.D. The central role of Sertoli cells in spermatogenesis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 1998;9:411–416. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1998.0203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gao M., Yi J., Zhu J., Minikes A.M., Monian P., Thompson C.B., Jiang X. Role of mitochondria in ferroptosis. Mol. Cell. 2019;73:354–363 e353. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.10.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.He Y.J., Liu X.Y., Xing L., Wan X., Chang X., Jiang H.L. Fenton reaction-independent ferroptosis therapy via glutathione and iron redox couple sequentially triggered lipid peroxide generator. Biomaterials. 2020;241 doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2020.119911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yang W.S., Stockwell B.R. Ferroptosis: death by lipid peroxidation. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26:165–176. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu M., Li Y., Wang X., Zhang Q., Wang L., Zhang X., Cui W., Han X., Ma N., Li H., Fang H., Tang S., Li J., Liu Z., Yang H., Jia X. Role of hepatocyte- and macrophage-specific PPARgamma in hepatotoxicity induced by diethylhexyl phthalate in mice. Environ. Health Perspect. 2022;130 doi: 10.1289/EHP9373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yang Y., Luo M., Zhang K., Zhang J., Gao T., Connell D.O., Yao F., Mu C., Cai B., Shang Y., Chen W. Nedd4 ubiquitylates VDAC2/3 to suppress erastin-induced ferroptosis in melanoma. Nat. Commun. 2020;11:433. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-14324-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang D.L., Ghosh M.C., Ollivierre H., Li Y., Rouault T.A. Ferroportin deficiency in erythroid cells causes serum iron deficiency and promotes hemolysis due to oxidative stress. Blood. 2018;132:2078–2087. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-04-842997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen P.H., Wu J., Ding C.C., Lin C.C., Pan S., Bossa N., Xu Y., Yang W.H., Mathey-Prevot B., Chi J.T. Kinome screen of ferroptosis reveals a novel role of ATM in regulating iron metabolism. Cell Death Differ. 2020;27:1008–1022. doi: 10.1038/s41418-019-0393-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aron A.T., Loehr M.O., Bogena J., Chang C.J. An endoperoxide reactivity-based FRET probe for ratiometric fluorescence imaging of labile iron pools in living cells. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:14338–14346. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b08016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang Y., Swanda R.V., Nie L., Liu X., Wang C., Lee H., Lei G., Mao C., Koppula P., Cheng W., Zhang J., Xiao Z., Zhuang L., Fang B., Chen J., Qian S.B., Gan B. mTORC1 couples cyst(e)ine availability with GPX4 protein synthesis and ferroptosis regulation. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:1589. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-21841-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang C., Chen S., Guo H., Jiang H., Liu H., Fu H., Wang D. Forsythoside A mitigates alzheimer's-like pathology by inhibiting ferroptosis-mediated neuroinflammation via nrf2/GPX4 Axis activation. Int. J. Biol. Sci. 2022;18:2075–2090. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.69714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huang Y.Q., Tang Y.X., Qiu B.H., Talukder M., Li X.N., Li J.L. Di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP) induced lipid metabolism disorder in liver via activating the LXR/SREBP-1c/PPARα/γ and NF-κB signaling pathway. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2022;165:113119. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2022.113119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zhao Y., Cui J.G., Zhang H., Li X.N., Li M.Z., Talukder M., Li J.L. Role of mitochondria-endoplasmic reticulum coupling in lycopene preventing DEHP-induced hepatotoxicity. Food Funct. 2021;12:10741–10749. doi: 10.1039/d1fo00478f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Zhao Y., Bao R.K., Zhu S.Y., Talukder M., Cui J.G., Zhang H., Li X.N., Li J.L. Lycopene prevents DEHP-induced hepatic oxidative stress damage by crosstalk between AHR-Nrf2 pathway. Environ. Pollut. 2021;285:117080. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2021.117080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Jiang F.W., Yang Z.Y., Bian Y.F., Cui J.G., Zhang H., Zhao Y., Li J.L. The novel role of the aquaporin water channel in lycopene preventing DEHP-induced renal ionic homeostasis disturbance in mice. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2021;226:112836. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2021.112836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Li M.Z., Zhao Y., Wang H.R., Talukder M., Li J.L. Lycopene Preventing DEHP-Induced Renal Cell Damage Is Targeted by Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021;69:12853–12861. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.1c05250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dai X.Y., Zhao Y., Ge J., Zhu S.Y., Li M.Z., Talukder M., Li J.L. Lycopene attenuates di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate-induced mitophagy in spleen by regulating the sirtuin3-mediated pathway. Food Funct. 2021;12:4582–4590. doi: 10.1039/d0fo03277h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.