Abstract

The pathogenicity island termed the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) is found in diverse attaching and effacing pathogens associated with diarrhea in humans and other animal species. To explore the relation of variation in LEE sequences to host specificity and genetic lineage, we determined the nucleotide sequence of the LEE region from a rabbit diarrheagenic Escherichia coli strain RDEC-1 (O15:H−) and compared it with those from human enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC, O127:H6) and enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC, O157:H7) strains. Differing from EPEC and EHEC LEEs, the RDEC-1 LEE is not inserted at selC and is flanked by an IS2 element and the lifA toxin gene. The RDEC-1 LEE contains a core region of 40 open reading frames, all of which are shared with the LEE of EPEC and EHEC. orf3 and the ERIC (enteric repetitive intergenic consensus) sequence present in the LEEs of EHEC and EPEC are absent from the RDEC-1 LEE. The predicted promoters of LEE1, LEE2, LEE3, tir, and LEE4 operons are highly conserved among the LEEs, although the upstream regions varied considerably for tir and the crucial LEE1 promoter, suggesting differences in regulation. Among the shared genes, high homology (>95% identity) between the RDEC-1 and the EPEC and EHEC LEEs at the predicted amino acid level was observed for the components of the type III secretion apparatus, the Ces chaperones, and the Ler regulator. In contrast, more divergence (66 to 88% identity) was observed in genes encoding proteins involved in host interaction, such as intimin (Eae) and the secreted proteins (Tir and Esps). A comparison of the highly variable genes from RDEC-1 with those from a number of attaching and effacing pathogens infecting different species and of different evolutionary lineages was performed. Although RDEC-1 diverges from some human-infecting EPEC and EHEC, most of the variation observed appeared to be due to evolutionary lineage rather than host specificity. Therefore, much of the observed hypervariability in genes involved in pathogenesis may not represent specific adaptation to different host species.

Attaching and effacing Escherichia coli (AEEC) induce a unique intestinal histopathological phenotype termed attaching and effacing (A/E), which is characterized by intimate bacterial attachment to the epithelial cells with effacement of microvilli and rearrangement of the host cell cytoskeleton to form a pedestal-like structure that cups individual bacterial cells (35). The A/E phenotype is encoded by the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) pathogenicity island (PAI) (32). The LEE in human enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) strain E2348/69 is a 36-kb cluster of genes containing five major polycistronic operons: LEE1, LEE2, LEE3, tir, and LEE4 (14). The LEE1, LEE2, and LEE3 operons contain genes which encode components of the type III secretion apparatus (esc and sep genes) and the ler (LEE-encoded regulator) gene. Ler is a positive regulator for the genes located inside the LEE and also regulates a number of genes located outside the LEE (16). The tir operon encodes intimin, Tir, and CesT (the chaperone for Tir) (1, 15). Intimin is a bacterial outer membrane adhesin involved in the intimate attachment of bacteria to host epithelial cells (22). Tir is translocated from the bacteria to the host epithelial cells, where it serves as a receptor for intimin (27). The LEE4 operon encodes the secreted proteins EspA, EspD, and EspB, which are involved in delivering Tir and other proteins to host cells (26, 29). LEE4 also encodes the type III secreted effector protein EspF (33), which is translocated into host cells and alters the tight-junction permeability of epithelial cells (G. Hecht, B. McNara, A. Koutsouris, and M. S. Donnenberg, Abstr. Dig. Dis. Week and 101st Annu. Meet. Am. Gastroenterol. Assoc., abstr. 2370, 2000).

The LEE is also found in a diverse range of A/E pathogens with differing host specificity and evolutionary history. These include Citrobacter rodentium, associated with colonic hyperplasia in mice; certain diarrheagenic strains of Hafnia alvei, now classified as Escherichia (20, 23); and diverse E. coli strains associated with diarrhea and other enteric infections in rabbits, pigs, calves, and dogs (8, 10, 21, 48). Among human diarrheal AEEC isolates, multilocus enzyme electrophoresis has identified four phylogenetic groups which reflect divergent evolutionary histories and follow biotype and serotype (46). Strains within each group also have different pathogenic properties and different virulence factors. EPEC strains colonize the small intestine and cause severe infant diarrhea, and they have been divided into two groups, EPEC 1 and EPEC 2. EPEC 1 strains include the well-characterized strain E2348/69 (O127:H6), as well as isolates of serotypes O55:H6, O142, and O86. The EPEC 2 group, which is more commonly isolated in developing nations, includes the well-characterized strain B171 (O111:H2), as well as other isolates of O111:H2, O126:H2, and O128:H2. Enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC) strains differ from EPEC strains in that they colonize the large intestine and cause diarrhea, bloody diarrhea, colitis, and hemolytic-uremic syndrome due to the production of Shiga toxin (Stx) in these strains. The EHEC 1 group includes the O157:H7 and O55:H7 strains, while EHEC 2 includes the O26:H11 and O111:H8 serotypes. Some AEEC strains which lack Stx and are therefore EPEC are more closely grouped with EHEC than with EPEC. For example, O55:H7 EPEC strains are related to EHEC 1, while the rabbit pathogen RDEC-1 is closely related to O26:H11 strains of EHEC 2 (46).

Electrophoretic grouping is also reflected in differences in the LEE. Among electrophoretic groups, there can be significant differences in the site of LEE insertion in the chromosome. In strains of the EPEC 1 group, the LEE is inserted at a selenocystyl (selC) tRNA gene at min 82 on the E. coli K-12 chromosome (31, 43, 46). In the related EHEC 1 group, the LEE is also inserted into the selC locus, but the LEEs from these strains contain 13 additional open reading frames (ORFs) within a putative P4 family prophage (40, 43, 47). LEEs of some strains from the EHEC 2 and EPEC 2 groups are inserted at the pheU site at min 94 of the K-12 chromosome, while other strains are inserted at a third site, as yet unknown (43). Different insertion sites are believed to represent distinct evolutionary events.

Within the LEE, there is also significant divergence among related genes. This was first observed in comparing EPEC 1 strain E2348/69 (14) and EHEC 1 strain EDL933 (40). Each LEE had a similar genetic organization, and genes encoding the Esc, Sep and Ces proteins, which are involved in assembling the type III machinery, were highly conserved. In contrast, more divergence was observed in proteins (and protein motifs) involved in host-pathogen interactions, such as intimin, Esp, and Tir, as well as in a number of genes with cryptic function (40). This variation has formed the basis for several typing schemes. Attempts have been made to classify intimin by means of sequence homology (3, 38), antigenic relatedness (2, 4), and PCR amplification (3, 38, 41, 42). There are at least five genetically and serologically distinct intimin types that generally correspond to electrophoretic groupings. A recent report extended a typing scheme to Tir, EspA, and EspB and demonstrated that A/E strains in different groups and from different animal isolates produce divergent intimin, Tir, and Esp proteins and that these were linked to pathogenesis in cattle (11).

Comparative analyses of complete LEE sequences have been limited since full sequence data are known only for the LEEs from E2348/69 (EPEC 1) and EDL933 (EHEC 1). These two groups are relatively close in evolutionary terms, and both are predominantly human pathogens, although EHEC 1 strains also colonize cattle. Relatively less information is available for animal AEEC. To better understand the contributions of different evolutionary lineage and host specificity, we sequenced the LEE from a divergent pathogen. RDEC-1 (O15:H−) is a rabbit enteropathogenic E. coli (REPEC) strain that produces characteristic A/E lesions in rabbit intestine and appears to be restricted to that host (10). RDEC-1 is most closely related to EHEC 2, especially the O26:H11 strains and to a lesser extent the O111:H8 strains, although RDEC-1 lacks the Stx-producing phage (46). We have previously described the construction and characterization of a plasmid (pDK5) containing a SmaI fragment from RDEC-1 which contains the LEE sequences and confers the A/E phenotype to E. coli K-12 in vitro (25). In this report, we describe the sequence of the RDEC-1 LEE and compare it with those of the EPEC 1 and EHEC 1 LEEs as well as with sequences of individual genes from a variety of A/E animal pathogens.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning, sequencing, and analysis of the LEE.

Plasmid and cosmid DNA for direct sequencing and for the PCR template was prepared using the QIAquick Miniprep kit (Qiagen). The nucleotide sequence of pDK5 was determined by the Taq Dye-terminator methods using an automated 373A DNA sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Electropherograms were analyzed and edited by using Sequencher 4.0 (Gene Codes Corp., Inc., Ann Arbor, Mich.). Comparisons of nucleotide and amino acid sequences were performed with BLAST programs offered by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, Md.).

PCR.

PCR to determine the insertion site of the LEE in RDEC-1 was performed as previously described (44). For the selC gene, chromosomal DNA template prepared from bacterial cells was amplified with primers K261 (5′-CCTGCAAATAAACACGGCGCAT) and K260 (5′-GAGCGAATATTCCGATATCTGGTT), giving a 402-bp amplification product for the intact selC gene. Primers K913 (5′-CATCGGCTGGCGGAAGATAT) and K914 (5′-CGCTTAAATCGTGGCGTC) were used to amplify the pheU gene, giving a 300-bp amplification product for the intact pheU gene. Two pair of primers, K260 plus K255 (K255, 5′-CGTTGAGTCGATTGATCTCTGG) and K296 plus K295 (K296, CATTCTGAAACAAAC TGCTC; K295, 5′-CGCCGATTTTTCTTAGCCCA), for amplifying the right and left junctions for the EPEC E2348/69 LEE, respectively, were used to further analyze both ends of the RDEC-1 LEE. These two pairs of primers both generate 418-bp products from strain E2348/69 (32). For PCR amplification, SUPERMIX high-fidelity mixture (Gibco BRL, Rockville, Md.) was mixed with template DNA (bacterial suspension in distilled water; 94°C for 10 min) and the respective pair of primers, while amplification was performed on a Peltier thermal cycler (MJ Research, Waltham, Mass.). PCR amplification products were separated on a 1.2% agarose gel and analyzed.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The nucleotide sequence for the RDEC-1 LEE region and flanking sequences determined in this study has been assigned GenBank accession number AF200363.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

In this report we describe the RDEC-1 LEE region, the first LEE sequenced from an AEEC of animal origin and the first sequenced from the EHEC 2 evolutionary group. This enables us to examine the structure of a divergent LEE and to compare genes and proteins from AEEC strains of differing host specificity and evolutionary history.

Defining the RDEC-1 LEE.

The physical map resulting from the complete nucleotide sequence of the 37,889-bp SmaI fragment of RDEC-1 in pDK5 is shown in Fig. 1. The G+C content of this 38-kb region is 41.3%, which is well below the E. coli K-12 average (50.8%) and is similar to that of the LEEs of E2348/69 (38.3%) (14) and EDL933 (41.2%) (40). This 38-kb DNA region contains the complete LEE of RDEC-1. Because it is difficult to determine the boundaries of the RDEC-1 LEE, we define an internal 34-kb (nucleotides [nt] 1032 to 35232) “core region” that is highly homologous to the nt-510-to-34592 region of E2348/69 and the nt-43749-to-9556 region of EDL933. The overall homology at the nucleotide level of this 34-kb core region between RDEC-1 and E2348/69 or EDL933 is 89.3%, compared with 92.2% homology between E2348/69 and EDL933. The 34-kb core region of the RDEC-1 LEE contains 40 ORFs, all of which correspond to the genes located on the LEEs from E2348/69 and EDL933 (14, 40). It is noteworthy that the LEE core regions of RDEC-1, EPEC (E2348/69), and EHEC (EDL933) are of virtually the same size and genetic organization, indicating that they have a common ancestor.

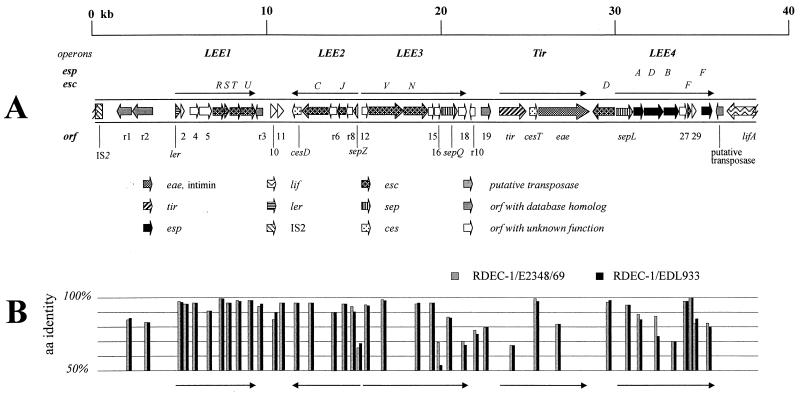

FIG. 1.

(A) Physical map of the RDEC-1 LEE. The orientation of each individual gene is indicated by the direction of the arrow. (B) Amino acid identity of conserved genes between RDEC-1 and E2348/69 (GenBank accession no. AF022236) and between RDEC-1 and EDL933 (GenBank accession no. AF071034). Arrows under the bars indicate the major polycistronic operons corresponding to those in panel A.

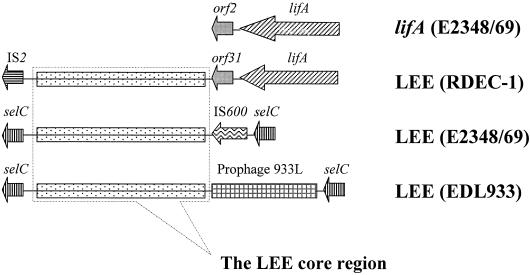

The regions flanking the RDEC-1 34-kb LEE core differ completely from those of E2348/69 and EDL933 (Fig. 2). In strain E2348/69, the LEE core region is surrounded by noncoding nucleotide sequences on the left side and a transposon before joining the selC locus at the right end (14). In EDL933, the flanking sequence of the core region contains 13 additional ORFs within a putative P4 family prophage (40). DNA sequences at the left-hand side of the RDEC-1 LEE core are highly homologous to the IS2 element of E. coli K-12 (99% homology over 396 bp), which is not found within the LEE of E2348/69 or EDL933 (14, 40). The association of IS elements with RDEC-1 LEE is not surprising since IS elements are often found associated with PAI or virulence genes carried on bacterial chromosomes or plasmids (9, 17, 45). IS elements can play a role in excision and presumably integration of PAIs (17), and their presence explains both the divergent LEE-flanking regions and the different insertion sites.

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of homologous and unique sequences in the LEE of RDEC-1, E2348/69, EDL933, and the lifA gene of E2348/69 (GenBank accession no. AJ133705). Homologous sequences are indicated by boxes with the same pattern. The dashed box indicates the 34-kb conserved core region of LEE. The flanking regions of the LEE are divergent among RDEC-1, E2348/69, and EDL933.

The right-hand end of the RDEC-1 LEE core region contains a 1,717-bp fragment which is also not found within the LEE of E2348/69 or EDL933 but shows more than 99% identity at the nucleotide level to the 3′ end of the recently reported lifA gene from E2348/69 (Fig. 2) (28) and the efa1 (for “EHEC factor for adherence”) gene from human EHEC 2 (strain E45035, O111:H−; GenBank accession no. AF159462) (36). The lifA and efa1 genes are homologous to lct from the large virulence plasmid of EHEC O157:H7. All three genes are predicted to encode proteins related to Clostridium difficile enterotoxin B (9, 28, 36). The lifA and efa1 genes encode proteins that have been described to repress host interleukins and/or mediate bacterial adherence independently of the LEE (28, 36). The lifA and efa1 genes are not adjacent to the LEE PAI in other AEEC bacteria, although their exact locations have not been reported, and we believe that the association of lifA and the LEE in RDEC-1 represents the insertion of lifA next to the LEE. Downstream of lifA in the RDEC-1 LEE is an ORF which shows 98% identity at the amino acid level to the Orf2 putative transposase downstream of lifA in E2348/69 (28). Comparing the region between the putative transposase and espF in RDEC-1 and the region downstream of lifA and orf2 in the E2348/69 lifA locus identified a 130-bp region of nonhomology. It appears that a region downstream of espF is a hot spot for the insertion of foreign genes, where a phage was inserted in EDL933 and a lifA gene was inserted in RDEC-1 (Fig. 2) (40).

Because the flanking regions do not contain DNA that could be used to localize the insertion site of the RDEC-1 LEE, we attempted to determine the insertion site of the LEE by PCR using primers specific for known insertion sites for LEEs of other strains as well as in the LEE itself. Amplification products corresponding to the intact selC and pheU genes were observed for RDEC-1 and K-12 strains (data not shown). This indicates that RDEC-1 LEE is not inserted in selC as it is for EPEC 1 and EHEC 1, nor is it inserted in the pheU site as determined for EPEC 2 strains such as those of the O111:H2 serotype, but that it is inserted into a third, novel insertion site.

Overview of the structure of the RDEC-1 LEE core region.

We have identified a total of 40 potential ORFs in the RDEC-1 LEE core region, all of which are found in the previously described LEEs of EPEC (E2348/69) and EHEC (EDL933) (14, 40). The RDEC-1 LEE genes are oriented and annotated according to the LEE of E2348/69 (14), starting with rorf1 and continuing through to espF. The arrangement of the RDEC-1 ORFs is also identical to that of the ORFs in EPEC, and so we predict the presence of at least five major polycistronic operons within the RDEC-1 LEE based on the experimentally determined operon structure of the EPEC LEE (Fig. 1).

There are a number of immediately obvious differences from the LEEs of E2348/69 and EDL933. First, the RDEC-1 LEE lacks orf3. The DNA fragment corresponding to the small orf3 region of E2348/69 has been found in RDEC-1. However, no apparent ORF was identified because of the absence of both ATG and alternative start codons, and we conclude that this ORF is unnecessary for the A/E phenotype in RDEC-1. Therefore, the LEE 1 operon is now ler orf2,4,5 escR,S,T,U, leaving a gap between orf2 and orf4.

Second, the RDEC-1 LEE lacks the enteric repetitive intergenic consensus (ERIC) element found in E2348/69 and EDL933, which is replaced in RDEC-1 by a 37-bp fragment (data not shown). The function of ERIC elements is unknown, and they may merely represent selfish DNA or may be involved in regulation.

Finally, it is clear that genes within RDEC-1 diverge further from both E2348/69 and EDL933 than E2348/69 or EDL933 diverge from each other, as shown in Fig. 1 and Table 1. This is consistent with differences in lineage as well as adaptation to specific hosts. We discuss differences in the major ORFs below.

TABLE 1.

Homology of highly variable proteins of RDEC-1 to those of other AEEC strains

| Virulence factor | % Identitya between RDEC-1 and:

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Human O127:H6 E2348/69 (EPEC 1) (intimin α) | Human O157:H7 EDL933 (EHEC 1) (intimin γ) | Dog O45 4221c (intimin α) | Pig O45:K“E65” 1390d (intimin β) | Rabbit O103:H2e (intimin β) | Human O26 (EHEC 2) (intimin β) | Human O111 (EPEC 2) (intimin β) | |

| SepZ | 65 | 69 | 100f | ||||

| Orf19 | 79 | 80 | 99g | 98i | |||

| Tir | 67 | 66 | 100b | 100bgh | 97i | ||

| N terminus (aa 1–244) | 66 | 72 | 100b | 100b | 98 | ||

| Central region (aa 245–351) | 79 | 79 | 100 | 100 | 91 | ||

| C terminus (aa 352–end) | 68 | 60 | 100 | 100 | 99 | ||

| Intimin | 82 | 82 | 86 | 99 | 100 | 100bh | 99k |

| N terminus (aa 1–660) | 94 | 94 | 93 | 99 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| C terminus (aa 661–end) | 55 | 53 | 70 | 99 | 100 | 100bi | 99 |

| EspA | 88 | 85 | 77 | 98 | 100 | 100j | |

| EspD | 87 | 73 | 78 | 100 | 100 | 100j | |

| EspB | 70 | 70 | 70 | 99 | 100 | 100j | |

| EspF | 82 | 80 | 95 | ||||

Homology at predicted amino acid level.

A 1-aa difference over the relevant region.

Strain B10, GenBank accession no. AF113597, AF054421, and AF116900 (30, 37); and strain 84/110/1, GenBank accession no. U59502.

O26:H11 (strain 6549), GenBank accession no. AF035656.

O26:H11 (strain H19), GenBank accession no. U62656; O26:HB6 (strain G85), GenBank accession no. U62657.

O111:H2 (strain DEC 12a), GenBank accession no. AF081187.

Promoter regions and regulation.

The promoter regions for several LEE operons in E2348/69 have been experimentally determined (34, 44), and we compared the known promoter regions of E2348/69 with regions upstream of the RDEC-1 operons. We found that the RDEC-1, EPEC, and EHEC LEEs have very similar predicted promoters, with similar spacing from the initiation codon (Table 2), and that the LEE2, LEE3, tir, and LEE4 promotors and putative regulatory regions are highly conserved. Since both LEE2 and LEE3 are directly regulated by Ler (34), which is highly conserved among AEEC strains, a conserved binding region would be expected. In contrast, examination of the DNA surrounding the predicted promoters revealed significant differences in LEE1 and tir. Upstream of the LEE1 promoter, there is substantial divergence, and the ERIC sequence is entirely lacking in the RDEC-1 LEE, as noted above. These findings may indicate fundamental differences in the regulation of ler, which is itself a key event in pathogenesis.

TABLE 2.

Comparison of the LEE1, LEE2, LEE3, tir, and LEE4 promoter regions among EPEC, EHEC, and RDEC-1a

| Gene or operon | Strain | Sequence

|

Position in LEE |

|---|---|---|---|

| −35 Spacer −10 +1 | |||

| LEE1 | EPEC | TTG TTGACA TTTAATGATAATGTAT TTTACA CATTAGAAA | 3916 |

| EHEC | ••• •••••• •••••••••••••••• •••••• ••••••••• | 40348cb | |

| RDEC-1 | ••• •••••• ••••••••••••••g• •••••• •••••tgc• | 4351 | |

| LEE2 | EPEC | TGC TTGAAA AAGCGTATTGGATAATA TATACA GTATATGTAC | 14766 |

| EHEC | ••• •••••• ••••••••••••••••• ••••t• •••••••••• | 29498c | |

| RDEC-1 | ••• •••••• ••••••••••••••••• ••••t• •••••••••• | 15218 | |

| LEE3 | EPEC | TAG TTGCAA TGTACATAAAGTACATA TACTGT ATATATTATCC | 14789 |

| EHEC | ••• •••••• ••••••••••••••••• •••••• ••••••••••• | 29475c | |

| RDEC-1 | ••• •••••• ••••••••••••••••• ••••a• ••••••••••• | 15241 | |

| tir | EPEC | TGC TTGCAT CAAAAATTATACTGTGA TTTATT TGGTTTATGC | 22446 |

| EHEC | •-• •••••• •••••••c•••t••••• •••••• ••••cg•••t | 21735c | |

| RDEC-1 | •-• •••••• •••••••c•g••••••• •••••• ••••cg•••t | 22993 | |

| LEE4 | EPEC | TGG TTGAAC AATGAGAAAAAATATGG TGAACT TACATCGTCT | 29169 |

| EHEC | ••• •••••• ••••••••••••••••• •••••• •••••••••• | 14934c | |

| RDEC-1 | ••• •••••• ••••••••••••••••• •••••• ••••••aa•• | 29698 | |

| Consensus | TTGACA 17 bp TATAAT |

Alignment of promoter regions among the LEEs from E2348/69, EDL933, and RDEC-1. Identical and different nucleotides are indicated by dots and lower case characters, respectively. Dashes indicate absent nucleotides.

c, complementary strand.

The 300-bp sequence upstream of the tir promoter also differed substantially (56 to 69%), suggesting that there are differences in the regulation of tir, cesT, and eae. Further direct examination of regulation in both RDEC1 and other AEEC is required.

Type III secretion components (Esc, Sep, and Ces).

The proteins that constitute the type III secretion system include Esc proteins, which are conserved among Yersinia species and other pathogens containing the type III secretion system; Sep proteins, which are more often LEE specific or may be found in the SPI-2 island of Salmonella; and the Ces secretion chaperones. In general, proteins necessary for type III secretion, including Esc, Sep, and Ces proteins, are conserved among strains, reflecting conservation of function and a lack of strong evolutionary pressure on cytoplasmic proteins. The Ces proteins are highly conserved (96% identical) among the three LEEs but are unique to the LEE and are not not found in other type III secretion systems. The Esc proteins and SepL also diverge by less than 5% and so are highly conserved among RDEC-1, E2348/69, and EDL933. Among the remaining Sep proteins, SepQ is 86% identical among the three strains but SepZ is hypervariable and is among the most divergent proteins encoded by the LEE (Table 1). This has been previously reported on the basis of a comparison of EPEC and EHEC (40) and of other SepZ entries in GenBank (S. J. Elliott and J. B. Kaper, unpublished data). The function of SepZ is unknown, and the significance of this observation is not clear.

Most type III secretion genes are carried within the LEE1, LEE2, and LEE3 operons, and these operons also include a number of ORFs of unknown function. The ORFs orf2,4,5 (LEE1), rorf6,8 (LEE2), and orf12,15,16 (LEE3) are at least 90% identical at the protein level and are placed in operons with other conserved type III secretion genes, which strongly suggests that these genes are also necessary for type III secretion. This hypothesis has been partly confirmed by mutagenesis studies (S. J. Elliott et al., unpublished data).

Tir operon.

The Tir operon encodes three proteins that are both genetically and functionally linked: Tir, CesT, and intimin. Tir varies in length from 538 amino acids (aa) for RDEC-1 to 550 aa for E2348/69 and 558 aa for EDL933. Both N-terminal and C-terminal regions of Tir demonstrated significant heterogeneity between RDEC-1 and the two human strains. These domains are located within the host cell and have host cell-signaling functions (27). In contrast, the central 107-aa region of Tir (aa 245 to 351) is more conserved and has been demonstrated to contain the intimin-binding domain of Tir (18). Overall, Tir is the second most divergent LEE-encoded factor, with only 66% identity to Tir from E2348/69 and EDL933.

The cesT gene, next to tir, encodes the Tir chaperone, which binds to the N-terminal region of Tir (1,15). Despite the N-terminal variation of Tir, CesT is highly conserved among RDEC-1, E2348/69, and EDL933, suggesting a common motif, among either primary or secondary structures of the Tir protein, that functions to recognize CesT.

Downstream of cesT is the eae gene, encoding intimin, which is the first and best-characterized virulence factor encoded by AEEC strains (22, 24). The RDEC-1 intimin is 18% divergent from that of E2348/69 and EDL933, but this variation is greater in some sections of the protein. One of the striking features of intimin is that the N terminus is highly conserved while the C-terminal third, which contains extracellular domains involved in interacting with Tir and the host cell, is highly variable among different intimins. This feature has been previously reported, and we extend this analysis in Table 2 and discuss it more fully below (4, 38).

Esp operon.

Half of the genes on the LEE4 operon are conserved between RDEC-1 and other AEEC, including sepL and escF, which encode components of the secretion system, and two genes of unknown function, orf27 and orf29. In striking contrast, the genes encoding the secreted proteins EspADBF in the LEE4 operon show up to 30% divergence between RDEC-1 and E2348/69 or EDL933 (Fig. 1). A more complete analysis of the heterogeneity of the esp genes is discussed below and in Table 1.

EspF.

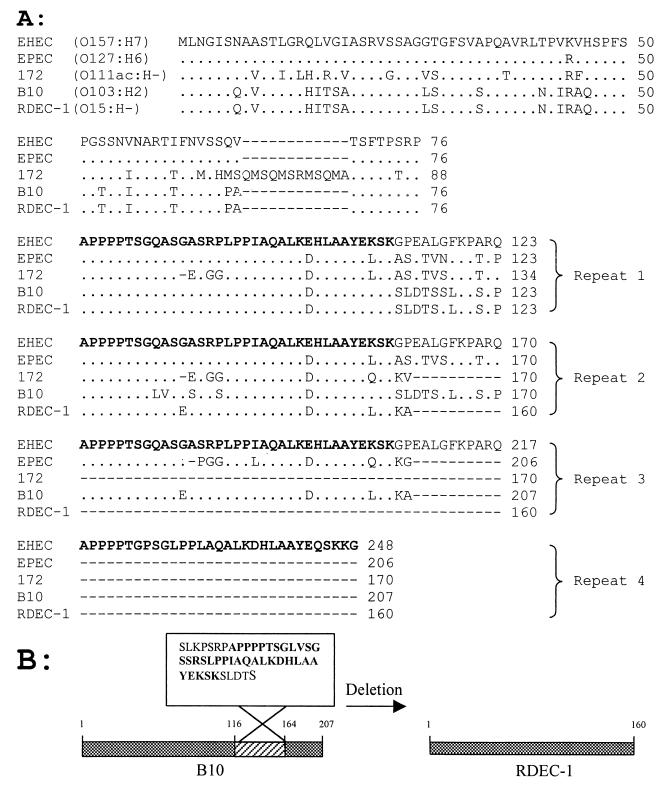

The most variable protein encoded by the LEE is the secreted effector protein EspF (Fig. 3), which differs in both amino acid sequence and in the size of each protein. RDEC-1 EspF is 160 aa, while E2348/69 EspF is 206 aa and EDL933 EspF is 248 aa. Alignment of the different EspF sequences demonstrates the existence of an absolutely conserved proline-rich APPPPT motif that is part of a larger (35-aa) motif (Fig. 3A) repeated within the EspF sequence and also conserved among EspF proteins from different isolates. The number of the larger repeats differs among the EspF proteins, from four repeats in EHEC to three in EPEC and two in RDEC-1, resulting in great differences in the lengths of EspF among strains. Interestingly, EspF from REPEC strain B10 (O103:H−) is identical to that of RDEC-1, except that the B10 EspF contains an additional 47-aa stretch (between aa 116 to 164 of B10 EspF). This may suggests that B10 diverged from RDEC-1 after deletion (or addition) of a repeat unit (Fig. 3B). The EspF of RDEC-1 is 71% identical to the EspF of another EPEC 2 strain of the O111 serogroup. The latter strain contains an additional 12-aa stretch in the EspF protein. We do not yet know the function of these repeats, although they have been observed to contain a proline-rich SH3 binding domain (13, 14, 33), implying that EspF interacts with host signaling molecules. A recent study demonstrated that EspF of EPEC is required for alteration of host intestinal epithelial barrier function (Hecht et al., Abstr. Dig. Dis. Week). We have demonstrated that EspF proteins from different isolates vary in size and that the number of repeat regions ranges from four in EHEC to two in RDEC-1. The presence of different numbers of repeats, as well as differences within each repeat, suggests different signaling functions, and such an ability could be consistent with differences in pathogenesis and host specificity among these AEEC strains.

FIG. 3.

(A) Alignment of EspF of EHEC (O157:H7, strain EDL933), EPEC (O126:H7, strain E2348/69), REPEC O103:H2 (strain B10, GenBank accession no. AF116900), and RDEC-1, showing repeated regions (repeats 1, 2, 3, and 4). A 31- to 35-aa conserved region is indicated in bold. Identical nucleotides are indicated by dots. Dashes indicate absent nucleotides. Numbers on the right side of the sequence indicate the amino acid number. (B) Comparison of EspF of RDEC-1 and B10. Identical amino acids are indicated by shaded bars. Numbers above the box indicate the positions of the amino acids. EspF of RDEC-1 is 47 aa (position indicated by the hatched box) shorter than EspF of B10. The sequence of the conserved 35-aa region is indicated in bold.

Other ORFs.

The proteins rOrf1 and rOrf2 of RDEC have moderate homology (83 to 87%) to those of E2348/69 and EDL933. This level of divergence is intermediate between that of the highly conserved intracellular components of the secretion system and that of the intimin, Esp, and Tir proteins, which are all highly divergent, are exposed on the surface of the cell or secreted into the medium, and interact with the host. This suggests that the rOrf1 and rOrf2 may be surface exposed and/or interact with the host. rOrf1 is predicted to be an outer membrane protein with homology to an outer membrane protein from Salmonella (14), and rOrf2 has recently been demonstrated to be a type III secreted protein that is able to interact with host cells (16a).

A number of other cryptic LEE-encoded proteins are hypervariable, including those encoded by orf10, orf18, rorf10, and orf19. The function of these proteins is unknown, although Orf19 is homologous to the Per-regulated EPEC chaperone protein TrcA, TrcP from the EHEC virulence plasmid, and proteins from Shigella, and probably functions as a chaperone. Recent work (Elliott et al., unpublished) has demonstrated that these genes are unnecessary for type III secretion by EPEC, and the fact that these genes are hypervariable suggests that they may encode proteins that are involved in interaction with the host.

The remaining two proteins, rOrf3 and Orf11, are conserved. rOrf3 is a member of a conserved group of peptidoglycan hydrolases, while the function of Orf11 is unknown (14).

Comparison of highly variable RDEC-1 proteins with those from other AEEC strains.

The LEE clearly contains a number of highly divergent genes and predicted protein products. In general, the highly variable proteins encoded by the LEE are those that are exposed on the surface of the cell and/or directly interact with the host. These include Tir, intimin, the Esp proteins, and the cryptic proteins SepZ and Orf19. Greater divergence is thought to reflect the greater evolutionary pressure on these proteins both from the host immune system, which selects for variation in surface-exposed proteins, and from differences among hosts, which select for differences in the functional domains. Such divergence has been used to classify AEEC isolates and to study differences associated with different host species, pathogenicities, and evolutionary lineages. In this context, we examined the relationship of highly variable RDEC-1 LEE proteins with those from isolates from different animal species and of different lineages, using previously reported sequences (Table 1).

The most common LEE-encoded protein used for typing is intimin, and several methods have been used to classify intimin (2–4, 38, 41, 42). Adu-Bobie et al. (2) identified at least five genetically and serologically distinct intimin types that generally follow evolutionary lineage: intimin α, which includes most of EPEC 1; the large intimin β group, containing human EPEC 2, EHEC 2, and the animal pathogens RDEC-1 and Citrobacter rodentium; intimin γ of EHEC 1; intimin δ of O86:H34 serotype EPEC 1 strains; and a fifth untypeable variety. This work was confirmed and extended using extensive sequence analysis by Oswald et al. (38), who also characterized intimin ɛ, which occurred most often in human EHEC strains of the O103 serogroup. REPEC strains of the O103 serogroup were grouped within the intimin β group, which also included O86:H34 strains, which were untypeable in the previous method (2).

Based on our predicted sequence analysis, we find that RDEC-1 intimin is significantly divergent, especially in the C-terminal third, from those of E2348/69 (α type), EDL933 (γ type), and a dog AEEC strain (α type) (5, 6). In contrast, intimin of RDEC-1 (β type) is over 99% identical to other β-intimins of human EPEC 2 and EHEC 2, including O111:H2, O111:H−, O128:H2, and O26:H11 serotypes and that of O103 REPEC and a pig EPEC strain (7).

A similar observation was made for other proteins. RDEC-1 Tir is highly conserved with that of rabbit isolates and human isolates of EPEC 2 and EHEC 2 groups but is highly divergent (66% identity) from those of E2348/69 and EDL933, especially in the more variable N-terminal and C-terminal thirds of the protein. The cryptic proteins SepZ and Orf19 of RDEC are identical or almost identical to those of O26:H11 and other EPEC 2 and EHEC 2 strains but are between 20 and 35% nonidentical to those of EPEC 1 and EHEC 1. Comparative analyses of EspABD proteins were more difficult because there are fewer database entries for these proteins from strains that have been phylogenetically characterized. Nonetheless, RDEC-1 Esp protein sequences were different from those of EPEC 1, EHEC 1, and dog EPEC and were nearly identical to those of pig EPEC, rabbit isolate O103, and human EPEC of the O26 serogroup, which probably belongs to EHEC 2.

A comparison of the highly variable proteins of RDEC-1 and other rabbit pathogens with proteins of EPEC 1 and EHEC 1 isolates would suggest that variation between these strains was consistent with differences in pathogenesis and host specificity. However, a more extensive comparison indicated that variation followed evolutionary lineage rather than host specificity. RDEC-1 proteins were identical to those of the human EHEC isolate of O26:H11 and very close to those of other human isolates of EHEC 2 groupings. That is, variation in the RDEC-1 LEE appears to be largely a function of evolutionary lineage rather than specific adaptation to a rabbit host because strains with LEE genes closely related to the RDEC-1 genes colonize and cause disease in humans, pigs, dogs, and rabbits.

Consistent with this observation, similar relatedness tended to occur across all genes within an isolate. For example, in all genes examined, RDEC-1 is 99 to 100% identical to rabbit AEEC and human EHEC O26 isolates, 97 to 99% identical to human O111 isolates, and 66 to 88% identical to EPEC 1 and EHEC 1 strains. If the LEE were to adapt for specific host differences, we might expect that one gene or protein motif would vary while others would vary less. Comparisons of sequences from other AEEC strains and from other loci are necessary to confirm this result.

In conclusion, a comparison of the complete RDEC-1 LEE sequence with full and partial LEE sequences from other sources reveal both conserved and variable characteristics. Conserved genetic features include the overall gene order as well as esc, sep, and ces and several orf and rorf genes, consistent with their conserved gene functions. In contrast, greater divergence was seen in some regulatory regions, genes known or suspected to interact with the host, and regions flanking the core LEE. These variations may be important in adaptations to specific pathogenic life-styles, but a comparison of the RDEC-1 LEE with those from other sources suggests that variation follows evolutionary lineage rather than host specificity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Lisa Sadzewicz and Nick Ambulos of the University of Maryland at Baltimore Biopolymer Laboratory for sequencing and analysis.

This work was supported by Public Health Service grants R01-DK51507 and RO1-DK52100 (E.C.B) and AI-21657 and AI-41523 (J.B.K.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe A, de Grado M, Pfuetzner R A, Sanchez-Sanmartin C, Devinney R, Puente J L, Strynadka N C, Finlay B B. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli translocated intimin receptor, Tir, requires a specific chaperone for stable secretion. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:1162–1175. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adu-Bobie J, Frankel G, Bain C, Goncalves A G, Trabulsi L R, Douce G, Knutton S, Dougan G. Detection of intimins α, β, γ, and δ, four intimin derivatives expressed by attaching and effacing microbial pathogens. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:662–668. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.3.662-668.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agin T S, Cantey J R, Boedeker E C, Wolf M K. Characterization of the eaeA gene from rabbit enteropathogenic Escherichia coli strain RDEC-1 and comparison to other eaeA genes from bacteria that cause attaching-effacing lesions. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;144:249–258. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08538.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Agin T S, Wolf M K. Identification of a family of intimins common to Escherichia coli causing attaching-effacing lesions in rabbits, humans, and swine. Infect Immun. 1997;65:320–326. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.320-326.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.An H, Fairbrother J M, Dubreuil J D, Harel J. Cloning and characterization of the eae gene from a dog attaching and effacing Escherichia coli strain 4221. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;148:239–245. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb10295.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.An H, Fairbrother J M, Dubreuil J D, Harel J. Cloning and characterization of the esp region from a dog attaching and effacing Escherichia coli strain 4221 and detection of EspB protein-binding to HEp-2 cells. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;174:215–223. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.An H, Fairbrother J M, Desautels C, Mabrouk T, Dugourd D, Dezfulian H, Harel J. Presence of the LEE (locus of enterocyte effacement) in pig attaching and effacing Escherichia coli and characterization of eae, espA, espB and espD genes of PEPEC (pig EPEC) strain 1390. Microb Pathog. 2000;28:291–300. doi: 10.1006/mpat.1999.0346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beaudry M, Zhu C, Fairbrother J M, Harel J. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of Escherichia coli isolates from dogs manifesting attaching and effacing lesions. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:144–148. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.1.144-148.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burland V, Shao Y, Perna N T, Plunkett G, Sofia H J, Blattner F R. The complete DNA sequence and analysis of the large virulence plasmid of Escherichia coli O157:H7. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:4196–4204. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.18.4196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cantey J R, Blake R K. Diarrhea due to Escherichia coli in the rabbit: a novel mechanism. J Infect Dis. 1977;135:454–462. doi: 10.1093/infdis/135.3.454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.China B, Goffaux F, Pirson V, Mainil J. Comparison of eae, tir, espA and espB genes of bovine and human attaching and effacing Escherichia coli by multiplex polymerase chain reaction. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;178:177–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13775.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deibel C, Kramer S, Chakraborty T, Ebel F. EspE, a novel secreted protein of attaching and effacing bacteria, is directly translocated into infected host cells, where it appears as a tyrosine-phosphorylated 90 kDa protein. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:463–474. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00798.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Donnenberg M S, Lai L C, Taylor K A. The locus of enterocyte effacement pathogenicity island of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli encodes secretion functions and remnants of transposons at its extreme right end. Gene. 1997;184:107–114. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00581-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elliott S J, Wainwright L A, McDaniel T K, Jarvis K G, Deng Y K, Lai L C, McNamara B P, Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B. The complete sequence of the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli E2348/69. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:1–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elliott S J, Hutcheson S W, Dubois M S, Mellies J L, Wainwright L A, Batchelor M, Frankel G, Knutton S, Kaper J B. Identification of CesT, a chaperone for the type III secretion of Tir in enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:1176–1189. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elliott S, Sperandio V, Giron J A, Shin S, Mellies J L, Wainwright L A, Hutcheson S W, McDaniel T K, Kaper J B. The locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE)-encoded regulator (Ler) controls the expression of both LEE- and non-LEE-encoded virulence factors in enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. Infect Immun. 2000;68:6115–6126. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.11.6115-6126.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16a.Elliott, S. J., E. O. Krejany, J. L. Mellies, R. M. Robins-Browne, C. Sasakawa, and J. B. Kaper. EspG, a novel type III secreted protein from enteropathogenic E. coli with functions similar to VirA of Shigella. Infect. Immun., in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Hacker J, Blum-Oehler G, Muhldorfer I, Tschape H. Pathogenicity islands of virulent bacteria: structure, function and impact on microbial evolution. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:1089–1097. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3101672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartland E L, Batchelor M, Delahay R M, Hale C, Matthews S, Dougan G, Knutton S, Connerton I, Frankel G. Binding of intimin from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli to Tir and to host cells. Mol Microbiol. 1999;32:151–158. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hulton C S, Higgins C F, Sharp P M. ERIC sequences: a novel family of repetitive elements in the genomes of Escherichia coli, Salmonella typhimurium and other enterobacteria. Mol Microbiol. 1991;5:825–834. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1991.tb00755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janda J M, Abbott S L, Albert M J. Prototypal diarrheagenic strains of Hafnia alvei are actually members of the genus Escherichia. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2399–2401. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2399-2401.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janke B H, Francis D H, Collins J E, Libal M C, Zeman D H, Johnson D D. Attaching and effacing Escherichia coli infections in calves, pigs, lambs, and dogs. J Vet Diagn Investig. 1989;1:6–11. doi: 10.1177/104063878900100104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jerse A E, Yu J, Tall B D, Kaper J B. A genetic locus of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli necessary for the production of attaching and effacing lesions on tissue culture cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7839–7843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.7839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaper J B, McDaniel T K, Jarvis K G, Gomez-Duarte O. Genetics of virulence of enteropathogenic E. coli. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;412:279–287. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1828-4_47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaper J B, Gansheroff L J, Wachtel M R, O'Brien A D. Intimin-mediated adherence of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and attaching-and-effacing pathogens. In: Kaper J B, O'Brien A D, editors. Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other Shiga-toxin producing E. coli strains. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 1998. pp. 148–156. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Karaolis D K, McDaniel T K, Kaper J B, Boedeker E C. Cloning of the RDEC-1 locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) and functional analysis of the phenotype on HEp-2 cells. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1997;412:241–245. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4899-1828-4_36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kenny B, Lai L C, Finlay B B, Donnenberg M S. EspA, a protein secreted by enteropathogenic Escherichia coli, is required to induce signals in epithelial cells. Mol Microbiol. 1996;20:313–323. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kenny B, Devinney R, Stein M, Reinscheid D J, Frey E A, Finlay B B. Enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC) transfers its receptor for intimate adherence into mammalian cells. Cell. 1997;91:511–520. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80437-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klapproth J M, Scaletsky I C, McNamara B P, Lai L C, Malstrom C, James S P, Donnenberg M S. A large toxin from pathogenic Escherichia coli strains that inhibits lymphocyte activation. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2148–2155. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.4.2148-2155.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Knutton S, Rosenshine I, Pallen M J, Nisan I, Neves B C, Bain C, Wolff C, Dougan G, Frankel G. A novel EspA-associated surface organelle of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli involved in protein translocation into epithelial cells. EMBO J. 1998;17:2166–2176. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marchès O, Nougayrède J-P, Boullier S, Mainil J, Charlier G, Raymond I, Pohl P, Boury M, De Rycke J, Milon A, Oswald E. Role of Tir and intimin in the virulence of rabbit enteropathogenic Escherichia coli serotype O103:H2. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2171–2182. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.4.2171-2182.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDaniel T K, Jarvis K G, Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B. A genetic locus of enterocyte effacement conserved among diverse enterobacterial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:1664–1668. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.5.1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McDaniel T K, Kaper J B. A cloned pathogenicity island from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli confers the attaching and effacing phenotype on E. coli K-12. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:399–407. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.2311591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McNamara B P, Donnenberg M S. A novel proline-rich protein, EspF, is secreted from enteropathogenic Escherichia coli via the type III export pathway. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;166:71–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mellies J L, Elliott S J, Sperandio V, Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B. The Per regulon of enteropathogenic Escherichia coli: identification of a regulatory cascade and a novel transcriptional activator, the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE)-encoded regulator (Ler) Mol Microbiol. 1999;33:296–306. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01473.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nataro J P, Kaper J B. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:142–201. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nicholls L, Grant T H, Robins-Browne R M. Identification of a novel genetic locus that is required for in vitro adhesion of a clinical isolate of enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli to epithelial cells. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:275–288. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01690.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nougayrede J P, Marches O, Boury M, Mainil J, Charlier G, Pohl P, De Rycke J, Milon A, Oswald E. The long-term cytoskeletal rearrangement induced by rabbit enteropathogenic Escherichia coli is Esp dependent but intimin independent. Mol Microbiol. 1999;31:19–30. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Oswald E, Schmidt H, Morabito S, Karch H, Marchès O, Caprioli A. Typing of intimin genes in human and animal enterohemorrhagic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli: characterization of a new intimin variant. Infect Immun. 2000;68:64–71. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.64-71.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Paton A W, Manning P A, Woodrow M C, Paton J C. Translocated intimin receptors (Tir) of Shiga-toxigenic Escherichia coli isolates belonging to serogroups O26, O111, and O157 react with sera from patients with hemolytic-uremic syndrome and exhibit marked sequence heterogeneity. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5580–5586. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5580-5586.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Perna N T, Mayhew G F, Posfai G, Elliott S, Donnenberg M S, Kaper J B, Blattner F R. Molecular evolution of a pathogenicity island from enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli O157:H7. Infect Immun. 1998;66:3810–3817. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3810-3817.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Reid S D, Betting D J, Whittam T S. Molecular detection and identification of intimin alleles in pathogenic Escherichia coli by multiplex PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:2719–2722. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.8.2719-2722.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schmidt H, Russmann H, Karch H. Virulence determinants in nontoxinogenic Escherichia coli O157 strains that cause infantile diarrhea. Infect Immun. 1993;61:4894–4898. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.11.4894-4898.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sperandio V, Kaper J B, Bortolini M R, Neves B C, Keller R, Trabulsi L R. Characterization of the locus of enterocyte effacement (LEE) in different enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) and Shiga-toxin producing Escherichia coli (STEC) serotypes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;164:133–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb13078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sperandio V, Mellies J L, Nguyen W, Shin S, Kaper J B. Quorum sensing controls expression of the type III secretion gene transcription and protein secretion in enterohemorrhagic and enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:15196–15201. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.15196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tobe T, Hayashi T, Han C G, Schoolnik G K, Ohtsubo E, Sasakawa C. Complete DNA sequence and structural analysis of the enteropathogenic Escherichia coli adherence factor plasmid. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5455–5462. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.5455-5462.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Whittam T S, McGraw E A. Clonal analysis of EPEC serogroups. Rev Microbiol. 1996;27:7–16. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wieler L H, McDaniel T K, Whittam T S, Kaper J B. Insertion site of the locus of enterocyte effacement in enteropathogenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli differs in relation to the clonal phylogeny of the strains. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;156:49–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhu C, Harel J, Jacques M, Desautels C, Donnenberg M S, Beaudry M, Fairbrother J M. Virulence properties and attaching-effacing activity of Escherichia coli O45 from swine postweaning diarrhea. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4153–4159. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.10.4153-4159.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]