Abstract

Objectives

War‐exposed refugee children are at elevated risk for mental health problems, but a notable proportion appear resilient. We aimed to investigate the proportion of Syrian refugee children who can be considered resilient, and applied a novel approach to identify factors predicting individual differences in mental health outcomes following war exposure.

Methods

The sample included 1,528 war‐exposed Syrian refugee children and their primary caregiver living in refugee settlements in Lebanon. Children were classed as having low symptoms (LS) if they scored below clinically validated cut‐offs for post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression and externalising behaviour problems. Children scoring above any cut‐off were classified as having high symptoms (HS). Each LS child was matched with one HS who reported similar war exposure, to test what differentiates children with similar exposures but different outcomes.

Results

19.3% of the children met our resilience criteria and were considered LS. At the individual level, protective traits (e.g. self‐esteem; OR = 1.51, 95% CI [1.25, 1.81]) predicted LS classification, while environmental sensitivity (OR = 0.69, 95% CI [0.59, 0.82]), poorer general health (OR = 0.71, 95% CI [0.58, 0.87]) and specific coping strategies (e.g. avoidance; OR = 0.90, 95% CI [0.85, 0.96]) predicted HS classification. Social/environmental predictors included perceived social support (OR = 1.23, 95% CI [1.02, 1.49]), loneliness and social isolation (OR = 0.85, 95% CI [0.80, 0.90]), child maltreatment (OR = 0.96, 95% CI [0.94, 0.97]), and caregiver mental and general health (e.g. caregiver depression; OR = 0.94, 95% CI [0.92, 0.97]).

Conclusions

Future research should take multiple dimensions of functioning into account when defining risk for mental health problems and consider the identified predictors as potential targets for interventions.

Keywords: War trauma, refugees, resilience, risk factors, protective factors

Introduction

The protracted crisis in Syria has led to the displacement of over 5 million Syrian people into surrounding countries (UNHCR, 2020). Many children and adolescents, who comprise approximately half of Syrian refugees, have not only been exposed to a wide variety of war‐related events, but also face on‐going adversities including lack of basic resources, unstable accommodation, and limited access to education. These adversities can have a significant psychological impact. Recent reports estimate that 23.4–49.6% of Syrian refugee children score above at least one clinical cut‐off when assessing post‐traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, and anxiety (ICED, 2019). However, prevalence rates vary widely (Kandemir et al., 2018; Khamis, 2019b), and not all children who experience significant adversity develop mental health problems. In other words, some appear to show psychological resilience.

Although definitions in the literature vary, resilience can be broadly described as positive development despite adversity (Masten, 2016; Schultze‐Lutter, Schimmelmann, & Schmidt, 2016), operationalised as a process or an outcome (i.e. manifested resilience; Masten, 2016). Importantly, although some children may initially present with mental health problems in response to adversity, they may recover over time and develop a resilient response (Masten & Narayan, 2012). However, in the case of refugees, longitudinal data are often rare (Scharpf, Kaltenbach, Nickerson, & Hecker, 2021), and manifested resilience predominantly investigated using outcomes at a single time, as a cross‐section of a highly dynamic process (Schultze‐Lutter et al., 2016).

Previous research in refugee populations has identified a range of factors across individual and social systems that predict risk and resilience (Popham, McEwen, & Pluess, 2021; Scharpf et al., 2021). For example, different coping strategies show adaptive or maladaptive functions (Khamis, 2019a), while parenting can either buffer or exacerbate the impact of adversity on children's mental health (Bryant et al., 2018; Khamis, 2019a). However, refugees living in informal settlements and low and middle income countries are underrepresented in the literature (Scharpf et al., 2021). Moreover, most current studies on resilience and war exposure are not able to determine if differences in mental health simply reflect different levels of war exposure. In other words, are children doing well due to certain resilience factors or did they have lower risk exposure to begin with?

Study aims

Our aim was to first identify the proportion of children with low risk for mental health problems despite adversity (i.e. displaying manifested resilience) in a sample of Syrian refugees in informal tented settlements (ITS) in Lebanon, and investigate what differentiated those meeting our resilience criteria from others exposed to the same war events but doing poorly at the time of assessment. A better understanding of these factors is important in order to promote resilience and prevent mental health problems through intervention. Based on the literature (ICED, 2019), we expected that approximately 50% of children would show evidence of manifested resilience and that both individual and social factors would differentiate children with low and high risk for mental health problems.

Methods

Study design

We used cross‐sectional data from a large sample of Syrian refugee child–caregiver dyads from the BIOPATH cohort study (McEwen et al., 2022). We applied clinically validated cut‐offs to measures of PTSD, depression, and externalising behaviour problems and used them to categorise children into low (LS) and high (HS) symptom groups. LS and HS children were paired according to their specific war exposure, age, gender, and time since leaving Syria to create a balanced subsample of cases with high and low symptoms of psychopathology but equal reported war exposure. We then investigated the relationships between potential risk and resilience factors and mental health outcomes in the matched subsample.

Ethical approval was granted by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Balamand, Lebanon (ref: IRB/O/024‐16/1815). The study was also reviewed by the Lebanese National Consultative Committee on Ethics and approved by the Ministry of Public Health.

Setting and participants

Data collection was conducted in ITSs in the Beqaa region of Lebanon in 2017/2018. We used purposive cluster sampling, approaching settlements representing a range of vulnerabilities according to the UNHCR vulnerability index (UNICEF, UNHCR, & WFP, 2017). After receiving agreement from the community leader of each settlement, we invited one child per family from all eligible families to participate. Families were eligible if they had left Syria no more than 4 years ago, the child was aged 8–16 years, and a primary caregiver was available to participate. Where multiple children in one family were eligible, the child with the birthday closest to the recruitment date was selected, to avoid biased selection. Informed consent and assent were given by each caregiver and child, respectively, and families were compensated for their time. Questionnaire data were collected via interviews in the settlements by a team of 16 interviewers to reduce barriers to participation. Visual aids were used to help understanding (Figure S1). Interviews lasted approximately 50–60 min. In order to focus on responses to war, we excluded children with no reported war exposure (n = 49). For a more detailed explanation of recruitment, see McEwen et al. (2022).

Variables

All participants were interviewed in their homes by trained Arabic‐speaking interviewers. Different interviewers conducted the child and caregiver interviews simultaneously. Some measures were exclusively child or caregiver reported, while others were reported by both (Table S1).

Exposure to war

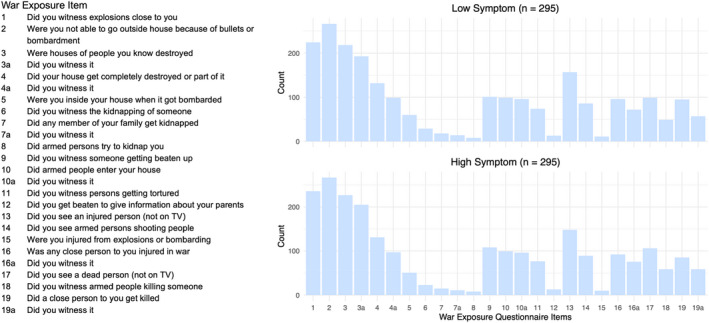

War exposure was measured with the War Events Questionnaire (WEQ), a 25‐item checklist measuring the number of different types of war event experienced (Karam, Al‐Atrash, Saliba, Melhem, & Howard, 1999). Because self‐report may be less reliable in younger children (Oh et al., 2018), child and caregiver responses were combined such that if either one reported that the child experienced an event, the event was considered to have occurred. For the specific items in the war questionnaire see Figure 1.

Figure 1.

War exposure questionnaire response pattern in matched groups. Bar chart showing the number of children who reportedly experienced each war event from the matched Low and High Symptom groups. Note: Items displayed in the table to the left correspond to the item numbers on the bar chart [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Mental health outcomes

Outcomes of interest were self‐reported PTSD (Child PTSD Symptom Scale; CPSS; Foa, Johnson, Feeny, & Treadwell, 2001), self‐reported depression (Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children; CES‐DC; Faulstich, Carey, Ruggiero, Enyart, & Gresham, 1986), and caregiver‐reported externalising behaviour problems measured using the externalising subscale of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 1997) and additional items related to conduct disorder and oppositional defiant disorder administered separately (McEwen et al., 2022). Scales were chosen according to reliability and validity in similar populations and pilot tested with Syrian refugees in Lebanon (McEwen et al., 2020; Appendix S1, Supplemental Methods). The CES‐DC was abridged to 10 items (Table S2) and minor changes to phrasing (including Arabic dialect) were made to the CES‐DC and CPSS based on pilot data (Appendix S1, Supplemental Methods; Table S1). We applied our own clinical cut‐offs (12 out of 51 on the CPSS, 10 out of 30 on the abridged CES‐DC and 12 out of 44 on the combined externalising scale total) derived from validation against consensus diagnosis based on structured clinical interviews using the MINI‐KID (Sheehan et al., 2010) and expert clinical judgement in a representative subsample (n = 119) of the study (McEwen et al., 2020). See Appendix S1, Supplemental Methods for further information.

We then created a categorical composite using the clinically validated cut‐offs: if participants scored below all three cut‐offs they were considered Low Symptom (LS), but if participants scored above the cut‐off for any of the three measures, they were classed as High Symptom (HS). Finally, we computed the average of the standardised scores on the three mental health scales as a continuous mental health composite score for use in sensitivity analyses.

Predictors and confounding variables

We investigated a broad variety of individual and social predictors that have been associated with mental health outcomes in previous research (Table S1). Individual‐level predictors included optimism (Ey et al., 2005), self‐efficacy (Schwarzer & Jerusalem, 1995), a single self‐esteem item (Harris, Donnellan, & Trzesniewski, 2018), the temperament trait of environmental sensitivity (Pluess et al., 2018), coping strategies (Program for Prevention Research, 1999), future orientation, and a single item on the child's general health (McEwen et al., 2022). For the social environment we included positive and negative aspects of the caregiver–child relationship (parental monitoring, Barber, 1996; parent–child conflict, Barber, 1999; psychological control, Barber, Xia, Olsen, McNeely, & Bose, 2012; positive home experiences, McEwen et al., 2022; maternal acceptance, Schaefer, 1965), child maltreatment (Runyan, Dunne, & Zolotor, 2009), the caregiver's own mental and general health (PTSD, Blevins, Weathers, Davis, Witte, & Domino, 2015; anxiety, Henry & Crawford, 2005; single general health item, McEwen et al., 2022; depression, Radloff, 1977), relationships within and beyond the family (loneliness, Asher, Hymel, & Renshaw, 1984; bullying, McEwen et al., 2022; perceived social support, Ramaswamy, Aroian, & Templin, 2009), and the child's home and employment responsibilities (McEwen et al., 2022). Finally, caregivers reported their literacy, income, employment status, household size, and aspects of the wider environment (perceived refugee environment, McEwen et al., 2022; collective efficacy, Sampson, Raudenbush, & Earls, 1997; human insecurity, Ziadni et al., 2011). For detailed information, including modifications to measures and rationale for inclusion of specific predictors, see Table S1.

Statistical methods

Analyses were conducted in RStudio Version 1.1.383. Multiple imputation using Fully Conditional Specification (FCS) in the mice package (van Buuren & Groothuis‐Oudshoorn, 2011) was applied to impute the small number of missing data (<5%). We imputed all missing measures for the analysis, except demographic variables, war exposure, and child mental health. We ran all analyses in both the imputed and original (complete case) datasets and report the pooled imputation estimates in the main text of this paper (complete case analyses are provided in Table S5). The Benjamini–Hochberg procedure was applied to all analyses in order to correct for multiple testing (Benjamini & Hochberg, 1995).

Matching and logistic regression

Children categorised into LS and HS groups were matched using nearest neighbour matching according to Mahalanobis distance in the MatchIt package (Ho, Imai, King, & Stuart, 2011). The groups were matched according to their specific pattern of responses across all the individual war exposure items, in addition to child age, gender, and time since leaving Syria, such that each group had the same proportion of boys and girls, almost identical mean age and time since leaving Syria, and an almost identical number of children who experienced each war event (Standardised Mean Difference between groups <0.1 for every item).

We then examined whether any of the variables of interest predicted LS or HS group membership using binary multivariable logistic regressions. We first ran separate individual models for each predictor. All predictors with a significant effect in their individual model were then entered simultaneously into a single combined model to identify which predictors had distinct effects when controlling for all statistically significant variables. Bivariate correlations between predictors in the combined model were computed to identify potential collinearities (Table S3). As a sensitivity analysis, we repeated these steps in the entire sample for greater power (>.99) using linear regression with continuous measures of war exposure and mental health, to ensure that the matching method did not bias results. We ran individual models for all predictors, additionally controlling for the war exposure total score, with the continuous mental health composite score as the outcome. Individually significant predictors were then entered into a combined linear model.

Results

Descriptive data

We collected data from 1,600 families. Excluding seven repeat participants, two families later identified as ineligible, 14 families missing key demographic or symptom data, and 49 children with no reported war exposure, the final sample included 1,528 children (52.6% female; mean age = 11.48, SD = 2.43) and their primary caregivers (89.5% mother). According to the combined child and caregiver report, children experienced an average of 9.90 (SD = 5.34) war events. The majority of children had experienced a bombardment‐related event, such as witnessing explosions (84%), but many had also experienced more direct interpersonal violence. For example, 36.6% reported witnessing torture and 44.4% reported that someone close to them was killed.

Low and high risk cases

Two hundred and ninety‐five (19.3%) children qualified as LS when combining the cut‐offs for PTSD, depression and externalising behaviour, while 1,233 (80.7%) scored above at least one of the three clinical cut‐offs and were categorised into the HS group (Table 1). In addition to scoring below the cut‐offs on all three psychopathology measures, the LS cases reported significantly higher levels of general well‐being (M = 74.03, SD = 21.08) than HS cases (M = 65.02, SD = 26.60); t(542) = 6.25, p < .001, d = .38 (World Health Organisation – Five Well‐being Index; Sibai, Chaaya, Tohme, Mahfoud, & Al‐Amin, 2009). They also had slightly lower war exposure (Appendix S2, Figure S2).

Table 1.

Number of participants scoring above cut‐offs for individual outcomes in the total and matched high symptom group samples

| Above cut‐off | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | |

| Total sample | |||

| PTSD | 859 | 56.2 | 1,528 |

| Depression | 594 | 38.9 | 1,528 |

| Externalising behaviour | 659 | 43.1 | 1,528 |

| Matched High Symptom group | |||

| PTSD | 188 | 63.7 | 295 |

| Depression | 133 | 45.1 | 295 |

| Externalising behaviour | 146 | 49.5 | 295 |

Matched sample

The matched sample comprised 295 LS‐HS pairs, meaning that a suitable match was found for all LS cases. The matched groups showed almost identical response patterns on the WEQ (Figure 1), had the same proportion of boys and girls (58.3% girls), and were evenly matched on age and time since leaving Syria (Figure S3). The matched sample had slightly less war exposure than the total sample (Figure S4). The selected HS cases had significantly higher scores on the continuous mental health composite score than LS cases (t(399.8) = 24.94, p < .001, d = 2.05), providing evidence that they had significant mental health problems (Figure S5).

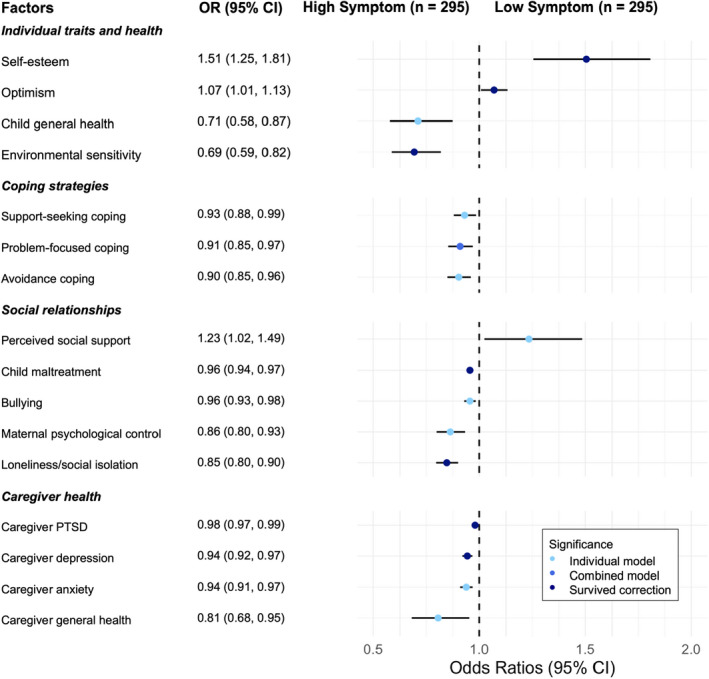

Main results

When LS and HS participants were matched on war exposure, several factors predicted group membership (Figure 2; Table S4). In individual models, self‐esteem, optimism, and perceived social support increased the odds of classification into the LS group. Poor child general health, environmental sensitivity, support‐seeking, problem‐focused coping, avoidance‐based coping, child maltreatment, bullying, loneliness, maternal psychological control, and caregiver general and mental health all decreased the odds a child belonged to the LS group.

Figure 2.

Logistic regression results for the factors that significantly predicted low/high symptom group membership. Forest plot and associated table, showing the odds rations and 95% confidence intervals from the individual logistic regression models for the factors that significantly predicted LS or HS group membership. Note: OR, odds Ratio; CI, Confidence Interval. Factors highlighted light blue for ‘Individual model’ were significant predictors of group only in individual models. Those highlighted royal blue for ‘Combined model’ remained significant when entered into the model combining all individually significant predictors. Those highlighted dark blue for ‘Survived correction’ are the factors that remained when correction for multiple was made in the combined model [Color figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

The logistic regression model combining all individually significant predictors explained 20.6% of the variance. Self‐esteem (OR = 1.38, 95% CI [1.17, 1.62]), optimism (OR = 1.07, 95% CI [1.01, 1.13]), the temperament trait of environmental sensitivity (OR = 0.83, 95% CI [0.72, 0.95]), loneliness and social isolation (OR = 0.90, 95% CI [0.86, 0.95]), child maltreatment (OR = 0.97, 95% CI [0.96, 0.99]), caregiver PTSD (OR = 0.99, 95% CI [0.98, 1.00]), and caregiver depression (OR = 0.96, 95% CI [0.93, 0.99]) survived correction for multiple testing in the combined model. Bivariate correlations between the predictors included in the combined model ranged from small to moderate (r = −.28–.65; Table S3).

The same analysis in the complete case data (n = 542) largely supported the main results, with some minor differences (Table S5). Support seeking was not predictive of group membership in the complete case data, whereas maternal acceptance was predictive. Fewer predictors remained significant in the combined model in the complete case data, likely due to lower power, but maternal psychological control did remain significant, unlike the imputed results. However, the direction of associations remained the same and effect sizes were similar.

The continuous sensitivity analysis looking at predictors of the continuous mental health composite score (n = 1,528) supported the main results, indicating that our matching technique did not introduce bias (Figure S6; Table S6). Every significant predictor in the main logistic regression remained so in the linear regression.

Discussion

Our aims were to identify which children in our sample could be considered to show resilience, and why, using a matching method to ensure mental health differences did not only reflect different levels of war‐exposure. We found that relatively few (19.3%) cases met our criteria for manifested resilience and were overall at low risk for mental health problems. Several specific factors on the individual and social level predicted individual differences in mental health in our sample.

Resilience

Due to the high levels of adversity faced by our sample, children who scored below the cut‐offs of all three outcome measures can be considered as demonstrating resilience in the context of war exposure. The relatively small number of resilient children in our sample compared to studies focusing on single outcomes (Khamis, 2019b) emphasises the importance of applying a multi‐dimensional approach. The absence of symptoms on one dimension does not mean that a child is doing well overall. However, our sample also shows higher prevalence of mental health problems than some studies that did account for multiple dimensions (Çeri, Nasıroğlu, Ceri, & Çetin, 2018; ICED, 2019). This may be due to challenges specific to our sample, who continue to experience on‐going adversity as refugees in Lebanon, with difficulty accessing basic necessities, services and work (McEwen et al., 2022). Worse mental health might therefore be expected compared to refugee populations resettled in more stable and less adverse conditions (Fazel, Reed, Panter‐Brick, & Stein, 2012). However, it is important to note that children scoring above cut‐offs, that we considered as high risk for mental health problems, may still recover over time (Masten & Narayan, 2012).

Predictors of risk and resilience

Several factors differentiated children with high and low risk for mental health problems. At the individual level, optimism and self‐esteem predicted LS group membership, whereas poor general child health and the temperament trait of environmental sensitivity predicted HS group membership. More surprisingly, coping strategies (support‐seeking, problem‐focused, and avoidant coping) predicted HS group membership. While avoidant coping is generally maladaptive, support‐seeking and problem‐focused coping are considered positive coping strategies (Scharpf et al., 2021). However, the specific context and nature of the adversity the current sample were exposed to likely play an important role here; problem‐focused strategies may be maladaptive when the problem is too complex to fix (Elklit, Østergård Kjær, Lasgaard, & Palic, 2012). Heightened reporting of coping strategies could also indicate increased need for those strategies, due to worse mental health.

At the social level, negative aspects of social relationships (bullying, loneliness/social isolation, child maltreatment, maternal psychological control) and caregiver mental and general health problems were predictive of HS group membership, in keeping with previous research (Karam et al., 2019; Khamis, 2019a; Scharpf et al., 2021). The key implication is that risk factors in the immediate social environment seem particularly important for children's mental health, compared to aspects of the living environment and socio‐economic factors. The nonsignificant findings for some aspects, such as access to education, are unexpected, and may also be due to the specific characteristics of the sample (e.g. few children go to school, so there may not be enough variance in the sample to see significant associations).

Although we have identified a series of predictors that are important in determining which children may be more able to adapt to war exposure in the particular context faced by the current sample, we must consider that these predictors likely interact with one another. The combined model results and bivariate correlations suggest that some predictors share variance, but most correlated predictors retain distinct predictive power even when combined. For example, caregiver depression is correlated with maltreatment, which could indicate a mediating pathway whereby caregiver mental health affects children via parenting (Bryant et al., 2018). However, caregiver depression and child maltreatment both remain significant in the combined model, indicating that they have separate effects on child mental health. On the other hand, individual predictors that are not significant in the combined model indicate potential shared effects on child mental health. For example, the correlations between the social relationship measures could explain why the effect of bullying does not survive in the combined model. The specific experience of bullying may not have additional effects on children when controlling for maltreatment in the home, and social isolation, one possible effect of bullying.

Our findings were supported by the logistic regression in the complete case data, and the linear regression in the total sample, but there were some small differences to note. Support seeking was non‐significant and maternal acceptance was significant in the complete case analysis, but effect sizes were almost identical to the imputed estimates. Additionally, fewer predictors remained significant in the complete case combined model, likely due to decreased power from the smaller sample size. However, maternal psychological control remained significant in the combined model in the complete case but not the imputed data. This could be explained by associations between predictors; maternal psychological control is correlated, and probably co‐occurs with, other social risk factors, such as child maltreatment, as well as with child self‐esteem, which is likely negatively impacted by controlling caregiver actions. The additional children in the imputed data may have increased the power to detect distinct effects beyond shared variance, but may also have tipped the balance as to exactly which predictors were significant in that specific model given these relationships. The individual predictor models indicate a number of measures likely key to our sample's adaptation to war exposure, but the complex interrelationships between predictors require further exploration.

Generalisability

One key strength of this study is the unique sample of vulnerable Syrian refugee children living in Lebanon, a middle income country bordering Syria, with an extremely high proportion of refugees (UNHCR, 2020). As the majority of refugees worldwide reside in low and middle income countries (UNHCR, 2020) our findings are generalisable to a large proportion of the global refugee population.

Limitations

Our data have certain limitations. First, cross‐sectional data precludes interpretations of the directionality of associations and the more complex dynamic processes of adaptation. Consequently, outcomes and predictors are difficult to separate cross‐sectionally. For example, while self‐esteem can be a stable trait (Brent Donnellan, Kenny, Trzesniewski, Lucas, & Conger, 2012), it could also reflect current mental well‐being. Moreover, those classified as HS may be able to successfully adapt in future, while the resilient sample will not necessarily be impervious to future challenges. Second, our measures were reported rather than observed, and some, such as war exposure, were retrospective, introducing potential recall bias confounded by participants' current state, in addition to challenges regarding reliability when collecting data from children (Panter‐Brick, Grimon, Kalin, & Eggerman, 2015). However, research on refugee war experiences is necessarily retrospective, and we included caregiver report of several key scales including war exposure to improve reliability (Oh et al., 2018). Third, we were limited by evaluating mental health with established symptom scales, some of which had to be translated, and reported by different informants. However, scales were extensively piloted and the most reliable selected, and, where possible, modified to be appropriate for the dialect, literacy and context of the families. Furthermore, we derived cut‐offs through clinical assessment in a subsample, choosing cut‐offs with the best balance of sensitivity and specificity for our particular sample (McEwen et al., 2020). It is important to note that, despite this, specificity fell below 80% and the risk group will contain false positives, meaning that the true proportion of resilient children is likely to be higher. Fourth, individual effects of some predictors were small, which should be considered in interpretation. Fifth, the complete case combined model results differed slightly from those in the imputed data. However, according to further checks, imputation did not significantly change patterns of responding, and the effect sizes remained very similar. Finally, a potential selection bias in recruitment cannot be excluded due to restricted access to certain settlements and reliance on presence of families during recruitment. Notwithstanding these limitations, our results provide an important step to understanding resilience in a highly vulnerable child population with considerable barriers to research access.

Conclusion

Applying a multi‐dimensional approach to child mental health in the context of war exposure, we provided an estimate of the proportion of resilient or low symptom children in a sample of Syrian refugees in Lebanon, and identified multiple predictive factors that could provide important targets for future mental health programmes. About one in five children from our sample showed no significant risk for mental health problems despite substantial war exposure. Multiple individual and social factors predicted outcomes, replicating findings from other conflict‐affected groups in this vulnerable but understudied population, but single factors alone accounted for small proportions of the overall variance in mental health. Our findings likely reflect the simultaneous consideration of multiple outcomes and of multiple predictors, emphasising the importance of characterising development across multiple dimensions rather than focusing on individual disorders, and of exploring the interrelationships between risk and resilience factors, particularly within the family environment. Future research should investigate these relationships longitudinally, to understand how individual resources and the social and environmental context can be leveraged together to help more children adapt to and recover from adversity.

Supporting information

Appendix S1. Supplemental methods.

Appendix S2. Supplemental results.

Table S1. Details of measures.

Table S2. 10‐Item Depression Scale (CES‐DC abridged).

Table S3. Bivariate correlations between predictors combined in regression models.

Table S4. Binary logistic regressions predicting low symptom group membership in individual and combined models.

Table S5. Binary logistic regressions predicting low symptom group membership in individual and combined models: complete case data.

Table S6. Multiple regression main effects in individual and combined regression models.

Figure S1. Visual aid for use with the abridged CES‐DC.

Figure S2. War exposure total score in the low and high symptom groups.

Figure S3. Age and time since leaving syria in matched low and high symptom groups.

Figure S4. Density plot representing the relative distribution of the war event score in the matched sample compared to the total sample.

Figure S5. Mental health symptom scores in the matched low and high symptom groups.

Figure S6. Multiple linear regression results for the factors that significantly predicted symptoms in the whole sample.

Acknowledgements

The BIOPATH study was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (R01HD083387). The funder played no role in study design, in the collection, analysis or interpretation of data, in the writing of the report, or the decision to submit the article for publication. The authors have declared that they have no competing or potential conflicts of interest. The authors warmly thank all participating families for their participation. The authors thank Patricia Moghames, Stephanie Legoff, Nicolas Puvis, and Zeina Hassan, and all other members of the BIOPATH team for their dedication, hard work and insights. This paper is dedicated to John Fayyad, who sadly passed away during the study.

Key points.

Existing research shows that many refugee children suffer from mental health problems, but some appear to be resilient.

We estimated the proportion of children showing low symptoms (LS) across PTSD, depression, and externalising problems despite war exposure (i.e. resilient children). We matched children with and without mental health problems according to their specific war exposure, and investigated which factors differentiated the groups.

19.3% of the children met our multidimensional LS criteria.

A range of factors differentiated LS from high symptom children when controlling for war exposure. Of particular importance were individual factors including self‐esteem, environmental sensitivity, and certain coping strategies, and social factors such as loneliness and social isolation, child maltreatment, and caregiver mental health.

Future intervention research should consider the interrelationships of individual and social factors.

Conflict of interest statement: No conflicts declared.

References

- Asher, S.R. , Hymel, S. , & Renshaw, P.D. (1984). Loneliness in children. Child Development, 55, 1456. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, B.K. (1996). Parental psychological control: Revisiting a neglected construct. Child Development, 67, 3296–3319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber, B.K. (1999). Political violence, family relations, and Palestinian youth functioning. Journal of Adolescent Research, 14, 206–230. [Google Scholar]

- Barber, B.K. , Xia, M. , Olsen, J.A. , McNeely, C.A. , & Bose, K. (2012). Feeling disrespected by parents: Refining the measurement and understanding of psychological control. Journal of Adolescence, 35, 273–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamini, Y. , & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate: A practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 57, 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- Blevins, C.A. , Weathers, F.W. , Davis, M.T. , Witte, T.K. , & Domino, J.L. (2015). The posttraumatic stress disorder checklist for DSM‐5 (PCL‐5): Development and initial psychometric evaluation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28, 489–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brent Donnellan, M. , Kenny, D.A. , Trzesniewski, K.H. , Lucas, R.E. , & Conger, R.D. (2012). Using trait–state models to evaluate the longitudinal consistency of global self‐esteem from adolescence to adulthood. Journal of Research in Personality, 46, 634–645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, R.A. , Edwards, B. , Creamer, M. , O'Donnell, M. , Forbes, D. , Felmingham, K.L. , … & Hadzi‐Pavlovic, D. (2018). The effect of post‐traumatic stress disorder on refugees' parenting and their children's mental health: A cohort study. The Lancet Public Health, 3, e249–e258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çeri, V. , Nasıroğlu, S. , Ceri, M. , & Çetin, F.Ç. (2018). Psychiatric morbidity among a school sample of Syrian refugee children in Turkey: A cross‐sectional, semistructured, standardized interview‐based study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 57, 696–698.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elklit, A. , Østergård Kjær, K. , Lasgaard, M. , & Palic, S. (2012). Social support, coping and posttraumatic stress symptoms in young refugees. Torture, 22, 11–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ey, S. , Hadley, W. , Allen, D.N. , Palmer, S. , Klosky, J. , Deptula, D. , … & Cohen, R. (2005). A new measure of children's optimism and pessimism: The youth life orientation test. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 46, 548–558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faulstich, M.E. , Carey, M.P. , Ruggiero, L. , Enyart, P. , & Gresham, F. (1986). Assessment of depression in childhood and adolescence: An evaluation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for Children (CES‐DC). American Journal of Psychiatry, 143, 1024–1027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel, M. , Reed, R.V. , Panter‐Brick, C. , & Stein, A. (2012). Mental health of displaced and refugee children resettled in high‐income countries: Risk and protective factors. The Lancet, 379, 266–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa, E.B. , Johnson, K.M. , Feeny, N.C. , & Treadwell, K.R.H. (2001). The Child PTSD Symptom Scale: A preliminary examination of its psychometric properties. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 30, 376–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman, R. (1997). The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 38, 581–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris, M.A. , Donnellan, M.B. , & Trzesniewski, K.H. (2018). The Lifespan Self‐Esteem Scale: Initial validation of a new measure of global self‐esteem. Journal of Personality Assessment, 100, 84–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry, J.D. , & Crawford, J.R. (2005). The short‐form version of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS‐21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non‐clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 227–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho, D.E. , Imai, K. , King, G. , & Stuart, E.A. (2011). MatchIt: Nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference. Journal of Statistical Software, 42, 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- International Centre for Evidence in Disability (ICED) . (2019). Survey of disability and mental health among Syrian refugees in Sultanbeyli, Istanbul .

- Kandemir, H. , Karataş, H. , Çeri, V. , Solmaz, F. , Kandemir, S.B. , & Solmaz, A. (2018). Prevalence of war‐related adverse events, depression and anxiety among Syrian refugee children settled in Turkey. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 27, 1513–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karam, E.G. , Al‐Atrash, R. , Saliba, S. , Melhem, N. , & Howard, D. (1999). The War Events Questionnaire. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 34, 265–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karam, E.G. , Fayyad, J.A. , Farhat, C. , Pluess, M. , Haddad, Y.C. , Tabet, C.C. , … & Kessler, R.C. (2019). Role of childhood adversities and environmental sensitivity in the development of post‐traumatic stress disorder in war‐exposed Syrian refugee children and adolescents. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 1–7, 354–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khamis, V. (2019a). Impact of pre‐trauma, trauma‐specific, and post‐trauma variables on psychosocial adjustment of Syrian refugee school‐age children. Journal of Health Psychology, 26, 1780–1790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khamis, V. (2019b). Posttraumatic stress disorder and emotion dysregulation among Syrian refugee children and adolescents resettled in Lebanon and Jordan. Child Abuse & Neglect, 89, 29–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten, A.S. (2016). Resilience in developing systems: The promise of integrated approaches. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 13, 297–312. [Google Scholar]

- Masten, A.S. , & Narayan, A.J. (2012). Child development in the context of disaster, war, and terrorism: Pathways of risk and resilience. Annual Review of Psychology, 63, 227–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen, F. S. , Moghames, P. , Bosqui, T. J. , Kyrillos, V. , Chehade, N. , Saad, S. , … & Pluess, M. (2020). Validating screening questionnaires for internalizing and externalizing disorders against clinical interviews in 8‐17 year‐old Syrian refugee children . Technical working paper. Available from: https://psyarxiv.com/6zu87/

- McEwen, F. S. , Popham, C. M. , Moghames, P. , Smeeth, D. , De Villiers Bernadette, ·, Saab, D. , … & Pluess, M. (2022). Cohort profile: Biological pathways of risk and resilience in Syrian refugee children (BIOPATH). Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 2022,1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh, D.L. , Jerman, P. , Purewal Boparai, S.K. , Koita, K. , Briner, S. , Bucci, M. , & Harris, N.B. (2018). Review of tools for measuring exposure to adversity in children and adolescents. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 32, 564–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panter‐Brick, C. , Grimon, M.‐P. , Kalin, M. , & Eggerman, M. (2015). Trauma memories, mental health, and resilience: A prospective study of afghan youth. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56, 814–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pluess, M. , Assary, E. , Lionetti, F. , Lester, K.J. , Krapohl, E. , Aron, E.N. , & Aron, A. (2018). Environmental sensitivity in children: Development of the Highly Sensitive Child Scale and identification of sensitivity groups. Developmental Psychology, 54, 51–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popham, C.M. , McEwen, F.S. , & Pluess, M. (2021). Psychological resilience in response to adverse experiences. In Multisystemic resilience (pp. 395–416). Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Program for Prevention Research . (1999). Manual for the children's coping strategies checklist and the how I coped under pressure scale. Tempe, AZ: Program for Prevention Research. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff, L.S. (1977). The CES‐D scale. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1, 385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Ramaswamy, V. , Aroian, K.J. , & Templin, T. (2009). Adaptation and psychometric evaluation of the multidimensional scale of perceived social support for Arab American adolescents. American Journal of Community Psychology, 43, 49–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Runyan, D.K. , Dunne, M.P. , & Zolotor, A.J. (2009). Introduction to the development of the ISPCAN child abuse screening tools. Child Abuse and Neglect, 33, 842–845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson, R.J. , Raudenbush, S.W. , & Earls, F. (1997). Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science, 277, 918–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer, E.S. (1965). Children's reports of parental behavior: An inventory. Child Development, 36, 413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scharpf, F. , Kaltenbach, E. , Nickerson, A. , & Hecker, T. (2021). A systematic review of socio‐ecological factors contributing to risk and protection of the mental health of refugee children and adolescents. Clinical Psychology Review, 83, 101930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultze‐Lutter, F. , Schimmelmann, B.G. , & Schmidt, S.J. (2016). Resilience, risk, mental health and well‐being: Associations and conceptual differences. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 25, 459–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwarzer, R. , & Jerusalem, M. (1995). Generalized self‐efficacy scale. In Weinman J., Wright S., & Johnston M. (Eds.), Measures in health psychology: A user's portfolio. Causal and control beliefs (pp. 35–37). Windsor, UK: NFER‐NELSON. [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan, D.V. , Sheehan, K.H. , Shytle, R.D. , Janavs, J. , Bannon, Y. , Rogers, J.E. , … & Wilkinson, B. (2010). Reliability and validity of the mini international neuropsychiatric interview for children and adolescents (MINI‐KID). Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 71, 313–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sibai, A.M. , Chaaya, M. , Tohme, R.A. , Mahfoud, Z. , & Al‐Amin, H. (2009). Validation of the Arabic version of the 5‐item WHO well being index in elderly population. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 24, 106–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) , United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) , & United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) . (2017). The vulnerability assessment for Syrian Refugees in Lebanon .

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees: Operational Data Portal . (n.d.). Available from: https://data2.unhcr.org/en/situations

- van Buuren, S. , & Groothuis‐Oudshoorn, K. (2011). mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. Journal of Statistical Software, 45, 1–67. [Google Scholar]

- Ziadni, M. , Hammoudeh, W. , Abu Rmeileh, N.M.E. , Hogan, D. , Shannon, H. , & Giacaman, R. (2011). Sources of human insecurity in post‐war situations: The case of Gaza. Journal of Human Security, 7, 23–36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Appendix S1. Supplemental methods.

Appendix S2. Supplemental results.

Table S1. Details of measures.

Table S2. 10‐Item Depression Scale (CES‐DC abridged).

Table S3. Bivariate correlations between predictors combined in regression models.

Table S4. Binary logistic regressions predicting low symptom group membership in individual and combined models.

Table S5. Binary logistic regressions predicting low symptom group membership in individual and combined models: complete case data.

Table S6. Multiple regression main effects in individual and combined regression models.

Figure S1. Visual aid for use with the abridged CES‐DC.

Figure S2. War exposure total score in the low and high symptom groups.

Figure S3. Age and time since leaving syria in matched low and high symptom groups.

Figure S4. Density plot representing the relative distribution of the war event score in the matched sample compared to the total sample.

Figure S5. Mental health symptom scores in the matched low and high symptom groups.

Figure S6. Multiple linear regression results for the factors that significantly predicted symptoms in the whole sample.