Abstract

Molecular cytogenetic and cytogenomic studies have made a contribution to genetics of epilepsy. However, current genomic research of this devastative condition is generally focused on the molecular genetic aspects (i.e. gene hunting, detecting mutations in known epilepsy-associated genes, searching monogenic causes of epilepsy). Nonetheless, chromosomal abnormalities and copy number variants (CNVs) represent an important part of genetic defects causing epilepsy. Moreover, somatic chromosomal mosaicism and genome/chromosome instability seem to be a possible mechanism for a wide spectrum of epileptic conditions. This idea becomes even more attracting taking into account the potential of molecular neurocytogenetic (neurocytogenomic) studies of the epileptic brain. Unfortunately, analyses of chromosome numbers and structure in the affected brain or epileptogenic brain foci are rarely performed. Therefore, one may conclude that cytogenomic area of genomic epileptology is poorly researched. Accordingly, molecular cytogenetic and cytogenomic studies of the clinical cohorts and molecular neurocytogenetic analyses of the epileptic brain appear to be required. Here, we have performed a theoretical analysis to define the targets of the aforementioned studies and to highlight future directions for molecular cytogenetic and cytogenomic research of epileptic disorders in the widest sense. To succeed, we have formed a consortium, which is planned to perform at least a part of suggested research. Taking into account the nature of the communication, “cytogenomic epileptology” has been introduced to cover the research efforts in this field of medical genomics and epileptology. Additionally, initial results of studying cytogenomic variations in the Russian neurodevelopmental cohort are reviewed with special attention to epilepsy. In total, we have concluded that (i) epilepsy-associated cytogenomic variations require more profound research; (ii) ontological analyses of epilepsy genes affected by chromosomal rearrangements and/or CNVs with unraveling pathways implicating epilepsy-associated genes are beneficial for epileptology; (iii) molecular neurocytogenetic (neurocytogenomic) analysis of postoperative samples are warranted in patients suffering from epileptic disorders.

Keywords: Brain, Epilepsy, Chromosomal abnormalities, Chromosome instability, Copy number variants, Cytogenomics, Epileptology, Molecular cytogenetics, Molecular neurocytogenetics, Pathways

Introduction

The last decade has seen a large number of achievements in genetics or genomics of epilepsy. Probably, genomic studies of epileptic disorders have demonstrated one of the most successful explorations of monogenic causes in a heterogeneous group of diseases. These data have been extensively used for understanding molecular mechanisms and developing treatments for this devastative condition [1, 2]. However, in contrast to monogenic epilepsies, epileptic disorders caused by chromosomal aberrations are rarely addressed. Simple querying in browseable scientific databases (e.g. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ or https://scholar.google.com/) demonstrates a bias towards monogenic epilepsies.

Cytogenomic variations (i.e. chromosomal abnormalities and copy number variants or CNVs) are generally addressed by advanced molecular cytogenetic techniques for scanning chromosomal/subchromosomal/intragenic imbalances (array comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) or SNP array) during analysis of neurodevelopmental cohorts (i.e. cohorts of children with intellectual disability, autism, epilepsy and/or congenital malformations) [3–8]. These studies generally focus on disentangling the genomic sources for epilepsy as a symptom [3, 9]. Additionally, searching for CNVs associated with idiopathic neurodevelopmental disorders allows the determination of causative variations in epileptic cases [10–12]. Therefore, it is not surprising that cytogenomic variations manifesting as individual CNVs or CNV burdens are more profoundly studied as to chromosomal abnormalities in the molecular genetic context.

It has long been demonstrated that numerous chromosomal disorders/syndromes exhibit epileptic seizures [13]. However, molecular definition of loci and intracellular pathways affected by chromosomal aberrations remain usually elusive in the epileptic context. It is reasonable to suggest that genomic complexity of chromosomal rearrangements, which encompass from tens to hundreds of genes, hinders the possibility of uncovering molecular and cellular pathways to epilepsy in each affected individual. Since this sophistication leads to difficulties in developing the treatment of epilepsy, clinical interest is limited in cases of epileptic chromosomal abnormalities. Consequently, a large number of patients with chromosomal disorders and epilepsy cannot get appropriate care and treatment. To solve the problem, specific interpretational/bioinformatic methods are required for unraveling molecular mechanisms of epilepsy in chromosomal disorders.

Chromosomal imbalances affecting brain functioning are common and are able to involve random genomic loci of any size or even entire chromosomes (e.g. aneuploidy or gains/losses of whole chromosomes in cellular nuclei) [10, 14]. Accordingly, to describe molecular mechanisms for specific epileptic condition in an affected individual, localization and ontologies of epilepsy-associated genes as well as candidate processes for epileptiform activity are to be known.

Somatic mosaicism is another source for alterations to functioning of the central nervous system. Molecular genetic analyses have repeatedly demonstrated that tissue-specific (brain-specific) mosaicism for causative mutations is detectable in individuals with neurodevelopmental diseases including a wide spectrum of epileptic disorders [15–18]. Generally, epilepsy is associated with the presence of cellular population affected by a mutation (gene mutation) and cellular population with the same mutation in the affected brain. More precisely, abnormal cells are more likely to be concentrated in epilepsy-associated brain lesions [19, 20]. On the other hand, as shown by a series of studies of the diseased brain (neurocytogenetic or neurocytogenomic studies), a broad spectrum of brain diseases (psychiatric, neurodegenerative and neurobehavioral diseases) is shown to be associated with aneuploidy, structural chromosome abnormalities, CNVs, and genome/chromosome instability (for review, see [21–26]). Furthermore, the levels of mosaicism and rates of chromosome/genome instability generally increase through ontogeny [27–29]. These aspects of dynamic behavior of cellular genomes have not been addressed in epilepsy. In total, it seems that there is need for selecting numerous targets for cytogenomic analyses of the brain in individuals suffering from epilepsy.

A brief look at cytogenomics of epilepsy or, as we prefer to call it, cytogenomic epileptology allows an intermediate conclusion that there are several key questions, which are required to be answered to get new insights into chromosomal mechanisms and molecular/cellular pathways of epileptic disorders. We intend this communication to serve a first step forward to the answers. Since a number of previous consortium efforts in genomic research of epilepsy were recognized as successful [30], we decided to form a consortium dedicated to cytogenomic epileptology gathering a number of experts in cytogenomics and genetics of epilepsy. Our theoretical work and review of previously reported (preliminary) data are presented here-below.

Cytogenomic variations: chromosomal abnormalities and beyond

Swimming in an ocean of articles describing genetic defects in epilepsy, one may distinguish a proportion of reports describing cases of chromosomal aberrations in individuals with epileptiform activity. However, the overwhelming majority of these cases are applicable for epilepsy research in clinical context only. Taking into account the importance of technological aspects for cytogenetic case reports (i.e. banding resolution (articles before 1990s), specificity of molecular cytogenetic methods etc. [31]), it was decided to skip detailed exploration of case reports on chromosome abnormalities in epilepsy. Recurrence of associations between chromosomal imbalance or microdeletion/microduplication syndrome and epilepsy, confirmation of the association, and application of cytogenomic techniques (e.g. array CGH or more advanced techniques) were used as criteria for detailed analysis. Table 1 summarizes data on chromosomal and subchromosomal imbalances [32–68], which correspond to these criteria.

Table 1.

Cytogenomics of epilepsy: chromosomal imbalances

| Chromosomal locus/loci | Syndrome/Aberration | References |

|---|---|---|

| 1p36 | 1p36 deletion syndrome | [32, 33] |

| 1q41q42 | 1q41-q42 deletion syndrome | [34] |

| 2p16.1p15 | 2p16.1-p15 microduplication syndrome | [35] |

| 3q29 | 3q29 duplication syndrome | [35, 37] |

| 4p | Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome | [38] |

| 5q14.3 | 5q14.3 Deletion Syndrome | [38] |

| 6 | 6q microdeletions | [40] |

| 7q11.23 | Williams-Beuren region duplication syndrome | [41] |

| 8q21.13-q22.2 | 8q21.13-q22.2 duplication | [42] |

| 8q24.3 | 8q24.3 duplication | [43] |

| 9q33q34 | 9q33-q34 microdeletion | [44–46] |

| 9q33-q34 microduplication | ||

| 9q34.11 | 9q34.11 deletions | [47] |

| 12q22.q23.3 | De novo duplication | [48] |

| 14q12 | Duplications encompassing FOXG1 | [49] |

| 14qter | Ring chromosome 14 | [50, 51] |

| 15q11.1-15q13.3 | Prader-Willi syndrome | [52] |

| Angelman syndrome | [53] | |

| 15q13.3 | 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome | [54, 55] |

| 15q14 | 15q14 deletion | [56] |

| 15q24 | 15q24.1 microdeletion and 15q24.2q24.3 duplication | [57] |

| 16p13.11 | 16p13.11 deletion | [58] |

| 17p13.3 | Miller-Dieker Syndrome | [59] |

| 17q12 | 17q12 duplication | [60] |

| 18p | 18p deletions | [61] |

| 19p13.13 | 19p13.13 deletions | [62] |

| 20 | Ring chromosome 20 | [63] |

| 22q11.2 | 22q11.2 deletion | [64] |

| 22q13.3 | 22q13.3 deletion | [65] |

| Xq13.1 | Xq13 duplication | [66] |

| Xp22.13 | Mosaic CDKL5 deletion (+ inversion) | [67] |

| Xq28 | Microdeletion forms of Rett syndrome | [68] |

Certainly, the table does not demonstrate the whole spectrum of recurrent cytogenomic findings in epilepsy. Still, it gives an overview of the amount of chromosomal syndromes associated with structural chromosomal imbalances and epilepsy. Additionally, individuals with aneuploidy syndromes may exhibit epileptiform activity from case to case [13, 14]. In this light, one should keep in mind somatic chromosomal mosaicism, which is able to change significantly clinical manifestation of chromosomal syndromes or to result into non-syndromic phenotypes, which, nevertheless, include epilepsy as a symptom [21, 69–71]. This suggestion becomes even more intriguing when tissue-specific or brain-specific mosaicism is proposed as a mechanism for brain dysfunction [14, 70, 71]. Thus, somatic chromosomal mosaicism with a special attention to brain-specific mosaics (structural rearrangements and aneuploidy confined to the brain) should be considered as a target for forthcoming studies in cytogenomic epileptology.

CNVs are a common type of cytogenomic variations repeatedly explored in epilepsy. The data on CNVs in epilepsy is found valuable for gene hunting and assessment of mutational (CNV) burden, which is able to cause the devastative condition. Usually, large consortia are focused on these cytogenomic variations to compare specific CNVs or CNV burdens between different patient groups [10, 72]. As a result, it becomes possible to generate big data on genomic variability and its association with variable phenotypes (i.e. cross-disorder dosage sensitivity of genomic variations) [73]. Unfortunately, replicability of these studies is poor suggesting further enlargement of acquired data sets only. Alternatively, keeping in mind a paradigm of personalized medicine, which is also applicable to epilepsy [74], one may propose individual approaches to analyze CNVs in individuals suffering from epileptic disorders. In fact, a bioinformatic concept of CNVariome might help in narrowing the outcomes of CNVs in epilepsy. This concept is based on an idea that the whole set of CNVs in an individual shape the phenotype. Accordingly, all CNVs detected in a patient are viewed as a system, where CNVs are elements interacting with each other through ontologies of genes affected by these cytogenomic variations [75]. Using this concept, one may uncover molecular and cellular processes changed by CNVs in an individual. The application of CNVariome concept for studying epilepsy has the potential to highlight new mechanisms of this devastative condition.

As one may see from the Table 1, imprinting disorders are associated with chromosome imbalances (deletions at 15q11.1-15q13.3) and epilepsy. Indeed, the two best known imprinting disorders—Angelman and Prader-Willi syndromes—represent a major focus of genetic epileptologists [76]. Here, it is noteworthy that runs of homozygosity or long contiguous stretches of homozygosity spanning shortly the imprinted loci (detectable by SNP array) are associated with epilepsy in atypical cases of Angelman or Prader-Willi syndrome [77, 78]. However, additional research is needed for defining phenotypic outcomes of these cytoepigenomic variations.

Another type of cytogenomic variations poorly addressed in epilepsy is referred to chromosome (genome) instability. An appreciable number of neurological and psychiatric diseases are associated with chromosome instability [24]. Moreover, chromosomal imbalances (deletions, duplications, ring chromosomes) and CNVs are able to produce chromosomal instability in cases demonstrating epileptiform activity [79, 80]. For instance, a specific type of chromosomal inability (chromohelkosis or chromosome ulceration/wound) is relatively common in neurodevelopmental cohorts, which include individuals with epilepsy (for more details, see [80]). In addition, it is pertinent to mention that brain-specific chromosome and genome instability is a key element of the pathogenetic cascades for several brain diseases [21, 24]. Consequently, it appears important to test postoperative and postmortem samples from individuals with epileptic disorders in the chromosome instability context.

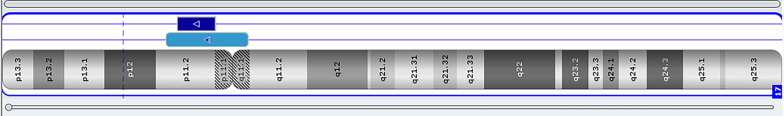

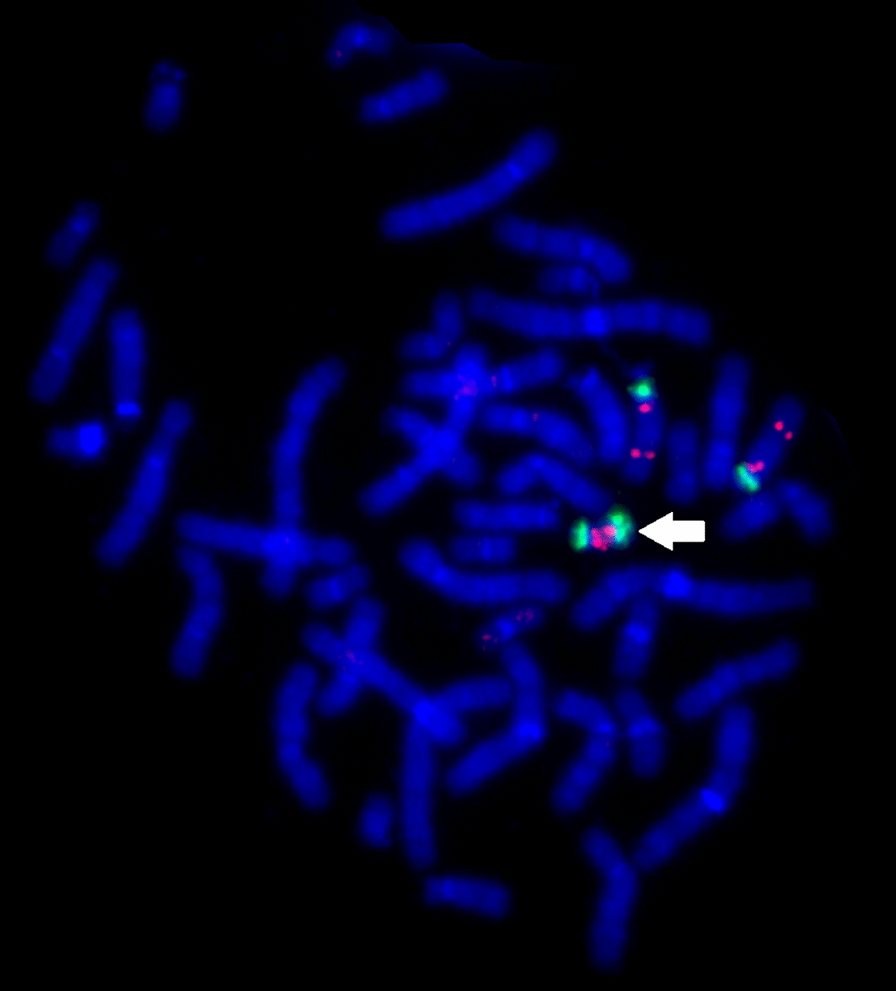

Finally, cytogenomic views on epilepsy are incomplete without considering small supernumerary marker (rearranged) chromosomes. Clinical outcomes of these chromosomal imbalances are highly heterogeneous ranging from normal to severe phenotypes (including epilepsy). Structural variability is supposed to be essential mechanism for such a phenotypic heterogeneity [81]. Another source for the heterogeneity is mosaicism [82]. Figure 1 demonstrates SNP array analysis of a mosaic case of supernumerary rearranged chromosome 17 in a child with epilepsy (Fig. 1). Alternatively, common types of small supernumerary marker chromosomes may even cause clinically recognizable syndromes exhibiting epilepsy. Probably, one of the best example of such syndromes is the inv dup(15) syndrome [83]. Figure 2 depicts fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis of this syndrome in a child suffering from a severe form of epilepsy (Fig. 2). In total, structural and phenotypic heterogeneity of small supernumerary marker chromosomes requires systematic analysis for the clinical interpretation. Databases may help epileptologists and clinical geneticists to assess contribution of small supernumerary marker chromosomes to the etiology of epilepsy. The most detailed information concerning associations between epilepsy and supernumerary marker chromosomes may be acquired using the database of marker chromosomes managed by Prof. Thomas Liehr (http://cs-tl.de/DB/CA/sSMC/0-Start.html). In summary, supernumerary marker chromosomes should be kept in mind when cytogenomic epileptology studies are performed.

Fig. 1.

SNP array analysis of a derivative chromosome 17 demonstrating the co-occurrence of mosaic and non-mosaic chromosomal abnormality (chromohelkosis)

Fig. 2.

Two-color-FISH demonstrating the presence of supernumerary rearranged (inv dup shaped) chromosome 15 (white arrow) in a child with epilepsy (DNA probes: SpectrumOrange—SNRPN + PML; SpectrumGreen—CEP15 or D15Z1)

To use cytogenomic data for unraveling mechanisms of epileptiform activity, specific bioinformatic methods are required. More precisely, chromosomal abnormalities and CNVariome (individual set of CNVs) are to be processed by techniques allowing the analysis of large gene sets. Fortunately, there are specific methods for ontology- and pathway-based evaluation of genes affected by chromosomal imbalances/CNVs based on data fusion and systems analysis [84–87]. These methods are effective enough to provide therapeutic opportunities in patients with chromosomal abnormalities, which are considered as genetic defects associated with untreatable conditions [88]. Since genes are essential elements in systems developed by processing cytogenomic data, it seems logical to address epilepsy associated genes in the pathway context.

Epilepsy genes, pathway-based analysis (classification) and candidate processes

Using a variety of gene hunting strategies, numerous epilepsy-associated genes have been identified during the last decades. Then, molecular processes or pathways implicating these genes have been described [1, 2, 10, 72, 73, 89]. Table 2 shows pathways implicating epilepsy-associated genes or gene families and corresponding disorders.

Table 2.

Essential types of pathways implicating epilepsy-associated genes (gene families) and corresponding epileptic disorders

| Type of pathways | Epileptic disorders | Chromosomal loci | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sodium channels | Developmental and epileptic encephalopathy, 6 (Dravet and non-Dravet types), 11, 13, 52, 62 types; generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus, types 1, 2, 7; familial focal epilepsy with variable foci 4; familial febrile seizures 3A and 3B; benign familial infantile seizures 3, 5 types | 2q24.3 | SCN1A, SCN2A, SCN3A, SCN7A/SCN6A, SCN9A |

| 3p22.2 | |||

| 11q23.3 | |||

| Potassium channels | Developmental and epileptic encephalopathy, 7, 14, 24, 57 types; generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus, type 10; epilepsy, progressive myoclonic 3, with or without intracellular inclusions; myokymia; benign neonatal seizures, type 1 and 2; cerebellar atrophy, developmental delay, and seizures; Liang-Wang syndrome; paroxysmal nonkinesigenic dyskinesia, 3, with or without generalized epilepsy; epilepsy, intellectual/developmental delay | 1p13.2-1p13.3 | KCN2A, KCNT2, HCN1, KCNT2, KCNB1, KCNQ1, KCND3, KCNC4, KCNA10 |

| Calcium channels | Developmental and epileptic encephalopathy, 42 and 69 types; primary aldosteronism, seizures, and neurologic abnormalities; susceptibility to childhood absence epilepsy 6; susceptibility to idiopathic generalized epilepsy 6 and 9; susceptibility to juvenile myoclonic epilepsy 6 | 3p21.31-3p14.3 | CACNA1E, PACS2, CACNA1A, CACNA1D, CACNA2D2, CACNA2D3, CACNG6, CACNG7, CACNG8 |

| 19q13.42 | |||

| Chloride channels | Susceptibility to idiopathic generalized epilepsy, 11; susceptibility to juvenile absence epilepsy, 2; susceptibility to juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, 8 | Wide cytogenetic distribution | CLCN family |

| Na/K+ pump | Hypomagnesemia, seizures, and mental retardation 2, Developmental and epileptic encephalopathy 98, 99 and 104 | 1q23.2-1q24.2 | ATP6V1A, PIGB, ATP1A2, ATP1A3, ATP1A2, ATP1A4, ATP1B1, KCNJ10, LY9, FXYD2, FXYD6, HEPACAM, FXYD1, FXYD5, FXYD7 |

| 11q23.3- 11q24.2 | |||

| 19q13.12-19q13.2 | |||

| GABA receptors | Developmental and epileptic encephalopathy 19, 43, 45, 54, 74, 78, 79 types; infantile or early childhood epileptic encephalopathy, 2; familial febrile seizures 8; generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus, type 3; susceptibility to generalized epilepsy with febrile seizures plus, type 5; susceptibility to childhood absence epilepsy 4, 5; susceptibility to juvenile myoclonic epilepsy, 5 | 4p12 | GABRA2, GABRB1, GABRB2, GABRA1, GABRG2, GABBR2, GABRB3, GABRA5 |

| 5q34 | |||

| Glycine receptors | Glycine encephalopathy with normal serum glycine | Genes of glycine system have wide cytogenetic distribution | |

| NMDA receptors | Developmental and epileptic encephalopathy 27 and 46 types; neurodevelopmental disorder with or without hyperkinetic movements and seizures, autosomal dominant and autosomal recessive types; focal epilepsy with speech disorder and with or without impaired intellectual development; intellectual developmental disorder, autosomal dominant 6, with or without seizures | 9q31.1-9q34.3 | GRIN1, GRIN2B, GRIN2D, GRIN1, GRIN3A, NSMF |

From the cytogenomic point of view, one may notice cytogenetic co-localization of epilepsy-associated genes from same gene families. This observation is important for deciphering the role of novel chromosomal rearrangements and large CNVs (> 100–150 kb) encompassing these loci in the epilepsy etiology. Epilepsy-associated gene clustering allows us to suggest that intranuclear interactions between these chromosomal loci through specific nuclear genome organization exist. In its turn, such kind of nuclear organization of epilepsy-associated genes may be involved in regulation/deregulation of the clusters (discussed hereafter).

Alternatively, looking at epilepsy-associated gene loci in the disease context (e.g. specific autosomal dominant epilepsy subtypes), the contrary is observed: variable localization and implication in molecular pathways of genes associated with the same type of autosomal dominant epilepsy (Table 3). Thus, we have to recognize the extended complexity of cytogenomic and “pathwayomic” parameters of epilepsy-associated genes.

Table 3.

Chromosomal loci and genes associated with autosomal dominant lateral temporal lobe epilepsy and autosomal dominant nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy

| Chromosomal loci | Phenotype | Disease MIM* | Gene/Locus | Gene/Locus MIM | Gene function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Autosomal dominant lateral temporal lobe epilepsy | |||||

| 3q25-q26 | Epilepsy, familial temporal lobe, 6 | 615697 | ETL6 | – | – |

| 4q13.2-q21.3 | Epilepsy, familial temporal lobe, 3 | 611630 | ETL3 | – | – |

| 7q22.1 | Epilepsy, familial temporal lobe, 7 | 616436 | RELN | 600514 | Neuronal migration |

| 8q13.2 | Epilepsy, familial temporal lobe, 5^ | 614417 | CPA6 | 609562 | Carboxypeptidase |

| 9q21-q22 | Epilepsy, familial temporal lobe, 4 | 611631 | ETL4 | – | – |

| 10q23.33 | Epilepsy, familial temporal lobe, 1 | 600512 | LGI1 | 604619 | Glutamate system |

| 11q13.2 | Epilepsy, familial temporal lobe, 8 | 616461 | GAL | 137035 | Neuropeptide |

| 12q22-q23.3 | Epilepsy, familial temporal lobe, 2 | 608096 | ETL2 | – | – |

| Autosomal dominant nocturnal frontal lobe epilepsy | |||||

| 1q21.3 | Epilepsy, nocturnal frontal lobe, 3** | 605375 | CHRNB2 | 118507 | Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor beta-2 subunit |

| 8p21.2 | Epilepsy, nocturnal frontal lobe, type 4 | 610353 | CHRNA2 | 118502 | Neuronal nicotinic cholinergic receptor alpha-2 subunit |

| 9q34.3 | Epilepsy nocturnal frontal lobe, 5 | 615005 | KCNT1 | 608167 | Sodium-activated potassium channel |

| 15q24 | Epilepsy, nocturnal frontal lobe, type 2 | 603204 | ENFL2 | – | – |

| 20q13.33 | Epilepsy, nocturnal frontal lobe, 1 | 600513 | CHRNA4 | 118504 | Neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor alpha-4 subunit |

*—Mendelian inheritance in Man (https://omim.org/); ^—autosomal recessive inheritance is reported, as well; **—autosomal dominant inheritance is uncertain;

Ontologies of epilepsy-associated genes have been systematically used for uncovering disease-causing pathways [1, 2]. On the other hand, participation of these genes in same gene families and molecular pathways (Table 2) is used as a successful gene hunting strategy [90]. Nonetheless, current knowledge about molecular and cellular systems, which functioning is mediated by a myriad of pathways, implies to apply pathway-based classification for the definition of disease mechanisms [91]. The availability of bioinformatic tools for solving this task in cases of gene mutations [92] and chromosomal aberrations [93] simplifies classifying diseases according to molecular and cellular pathways. Thus, for uncovering the way from genomic changes to epileptic phenotype passing through pathways or metabolic processes, classification issues should be addressed. Consequently, it is unavoidable to establish correlations between (cyto)genomic and clinical (phenotypical) data or to establish genotype–phenotype correlations.

Classification matters

The essential classification of epilepsy is based on clinical observations (as for the overwhelming majority of complex diseases). ILAE (International League Against Epilepsy) classification of the epilepsies is the basic document [94]. Clinical and diagnostic practice (including genetic testing) in epileptology is performed using the classification. Genetic classification of epilepsy, which is less official than clinical and is closer to nature, is almost completely dedicated to monogenic forms/syndromes [95]. Thus, 977 epilepsy-associated genes were classified according to the clinical outcomes of the mutations/variants. Four categories were proposed [96]: (1) gene mutations causing epilepsy per se or syndromes with epilepsy as the core symptom; (2) gene mutations causing neurodevelopmental anomalies/malformations resulting in epilepsy; (3) gene mutations causing gross systemic abnormalities accompanied by epilepsy; (4) gene variants of uncertain significance. In summary, it seems that neither cytogenomic variations nor disease pathways are the focus for classification of epilepsy. Consequently, we conclude that a large bioinformatic, clinical and molecular cytogenetic (cytogenomic) work is required to fill this gap in epileptology, (cyto)genomic epileptology.

Preliminary cytogenomic analysis of the cohort

To form the cohort for cytogenomic analysis of epilepsy, we have initially selected individuals from the Russian neurodevelopmental cohort. Once selected, molecular karyotyping by array CGH or SNP array analyses has been performed. Details and cohort description have been previously presented elsewhere [7, 12, 78, 97–99]. Tables 4 and 5 present the data.

Table 4.

Gross chromosomal aberrations detected in children with epilepsy forming the neurodevelopmental cohort

| Chromosome abnormality according to cytogenetic analysis | Chromosomal loci according to SNP array data | Aberration (copy number change) | Brief clinical description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 46,XX,add(3)(p26) | 3p26.3 | × 1 | Developmental delay, epilepsy, unsteady gait, developmental abnormalities: broad flattened face, cleft palate, short toes, sandal gap, syndactyly of II-III toes; structural heart defect |

| 3p26.3p24.3 | × 3 | ||

| 47,XX, + mar | 17p11.2q11.1 | × 2 ~ 3 | Developmental delay, epilepsy, biliary dysfunction, hypertelorism of the palpebral fissures, congenital clouding of the cornea of the right eye, strabismus, wide nose, low-lying auricles, ear appendages on the left; long QT, increase in mobility, volume and changed parenchyma of the kidneys |

| 17p11.2 | × 3 | ||

| 46,XX,der(11)?add(11)(p13)ins(11)(p13q21q23.3) | – | – | Developmental delay, epilepsy, developmental abnormalities: up-slanting palpebral fissures epicanthus, broad nasal bridge, epithelial coccygeal passage; congenital heart and celiac diseases |

| 46,XX,del(6)(q22.?2q23.?3) | 6q22.1q23.2 | × 1 | Developmental delay, epilepsy, developmental abnormalities: thin sparse hair, narrow face, hypotelorism of the palpebral fissures, enlarged middle part of the face, retrognathia, dys-plastic auricles, small teeth, brachydactyly, thin nails, thoracic kyphosis |

| 46,XY,del(15)(q11.2q1?3) | 15q11.2q13.1 | × 1 | Developmental delay, epilepsy, developmental abnormalities: flattened face, high forehead, ocular hypotelorism, high-arched palate, short neck, wobbly gait |

Table 5.

CNVs detected in children with epilepsy forming the neurodevelopmental cohort

| Genetic sex | Copy number | Chromosome locus (loci) |

|---|---|---|

| Chromosome X | ||

| XX | × 3 | Xp22.13 |

| × 3 | Xq27.3 | |

| × 3 | Xq28 | |

| × 1 | Xq23 | |

| × 2 ~ 3 | Xq26.2q26.3 | |

| × 3 | Xq22.1 | |

| × 0 | Xp11.23 | |

| XY | × 2 | Xq28 |

| × 2 | Xp22.13 | |

| × 2 | Xq21.1 | |

| × 0 | Xq21.1 | |

| × 2 | Xp22.31 | |

| × 2 | Xp11.4 | |

| × 2 | Xq27.3 | |

| × 2 | Xp11.23 | |

| × 2 | Xq12 | |

| Chromosome Y | ||

| XY | × 2 | Yq11.223 |

| × 2 | Yq11.223q11.23 | |

| × 0 | Yq11.23 | |

| Chromosome 1 | ||

| XY | × 1 | 1q42.13 |

| × 1 | 1p31.1 | |

| × 1 | 1p22.1 | |

| × 1 | 1p13.2 | |

| XX | × 3 | 1p36.32 |

| × 4 | 1p31.3 | |

| × 3 | 1p21.3 | |

| × 1 | 1p21.1 | |

| Chromosome 2 | ||

| XX | × 4 | 2q22.1 |

| XY | × 1 | 2q37.1 |

| × 1 | 2q24.3q31.1 | |

| 2q24.3 | ||

| × 1 | 2q31.1 | |

| × 3 | 2p12 | |

| Chromosome 3 | ||

| XY | × 3 | 3p25.3 |

| × 1 | 3p14.1 | |

| × 4 | 3q29 | |

| XX | × 3 | 3p26.3 |

| XX | × 1 | 3p26.2 |

| × 1 | 3p14.2 | |

| × 1 | 3q23 | |

| × 4 | 3q26.33 | |

| Chromosome 4 | ||

| XX | × 3 | 4q34.3 |

| XY | × 4 | 4q21.21 |

| × 3 | 4q31.3 | |

| × 1 | 4q21.22 | |

| Chromosome 5 | ||

| XX | × 3 | 5q13.3 |

| × 1 | 5q22.2 | |

| × 3 | 5p13.2 | |

| × 1 | 5q13.2 | |

| × 1 | 5q33.1 | |

| Chromosome 6 | ||

| XX | × 1 | 6p11.2 |

| × 1 | 6q25.3 | |

| XY | × 3 | 6q26 |

| Chromosome 7 | ||

| XY | × 1 | 7p12.3 |

| × 3 | 7p21.1 | |

| × 3 | 7p13 | |

| × 1 | 7q21.2 | |

| XX | × 3 | 7p22.3p21.2 |

| × 1 | 7q32.3 | |

| × 1 | 7q11.21 | |

| × 4 | 7q21.11 | |

| × 1 | 7q31.1 | |

| × 1 | 7q22.1 | |

| Chromosome 8 | ||

| XY | × 3 | 8p23.3 |

| × 1 | 8q12.2 | |

| × 1 | 8p21.3 | |

| × 1 | 8p21.2 | |

| × 4 | 8q21.13 | |

| × 1 | 8p23.1 | |

| × 1 | 8q12.1 | |

| Chromosome 9 | ||

| XY | × 1 | 9q34.3 |

| XX | × 1 | 9q34.3 |

| × 4 | 9q21.31 | |

| × 4 | 9q33.2 | |

| × 1 | 9q34.13 | |

| × 3 | 9q34.12 | |

| × 2 ~ 3 | 9p24.3p24.2 | |

| × 3 | 9p24.3 | |

| × 1 | 9p24.3p23 | |

| × 1 | 9p23 | |

| Chromosome 10 | ||

| XY | × 3 | 10q24.32 |

| × 4 | 10q24.32 | |

| × 3 | 10q24.1 | |

| × 4 | 10q25.2 | |

| × 4 | 10p12.31 | |

| × 4 | 10q26.3 | |

| × 1 | 10q25.1 | |

| × 4 | 10p15.3 | |

| × 3 | 10q24.2 | |

| Chromosome 11 | ||

| XY | × 1 | 11p15.5 |

| × 1 | 11p13 | |

| × 4 | 11p12 | |

| XX | × 1 | 11p15.4 |

| × 1 | 11q22.3 | |

| × 3 | 11q22.3 | |

| × 4 | 11p13 | |

| × 3 | 11q13.1 | |

| × 3 | 11q12.1 | |

| Chromosome 12 | ||

| XX | × 1 | 12q24.13 |

| × 3 | 12p13.31 | |

| × 1 | 12p12.1 | |

| × 1 | 12q13.12 | |

| XY | × 1 | 12q13.13 |

| × 3 | 12p13.31 | |

| × 1 | 12q24.31 | |

| × 1 | 12p12.2 | |

| Chromosome 13 | ||

| XY | × 1 | 13q12.12 |

| XX | × 1 | 13q33.3 |

| × 3 | 13q14.11 | |

| × 1 | 13q33.3q34 | |

| Chromosome 14 | ||

| XY | × 1 | 14q24.1 |

| × 1 | 14q21.3 | |

| Chromosome 15 | ||

| XX | × 1 | 15q21.3 |

| × 1 | 15q26.3 | |

| × 1 | 15q15.3 | |

| × 1 | 15q21.1 | |

| XY | × 1 | 15q15.1 |

| × 1 | 15q21.3 | |

| × 1 | 15q22.2 | |

| × 3 | 15q26.3 | |

| × 1 | 15q11.2 | |

| Chromosome 16 | ||

| XY | × 1 | 16p13.3 |

| × 1 | 16q23.2 | |

| XX | × 3 | 16p13.3 |

| × 1 | 16p13.3 | |

| × 1 | 16p11.2 | |

| × 3 | 16q24.3 | |

| × 1 | 16p13.12 | |

| × 1 | 16q23.1 | |

| × 1 | 16q23.3 | |

| × 1 | 16q24.3 | |

| Chromosome 17 | ||

| XY | × 3 | 17p13.3 |

| × 1 | 17q21.1 | |

| × 2 ~ 3 | 17p13.2p12 | |

| × 4 | 17p13.2p13.1 | |

| × 3 | 17p13.1 | |

| × 3 | 17p11.2 | |

| × 1 | 17p13.2 | |

| XX | × 3 | 17p13.3 |

| × 1 | 17q21.31 | |

| × 1 | 17q21.1 | |

| Chromosome 18 | ||

| XX | × 3 | 18q12.1 |

| × 3 | 18q21.2 | |

| Chromosome 19 | ||

| XY | × 1 | 19p13.3 |

| × 3 | 19p13.11 | |

| XX | × 1 | 19q13.2 |

| × 1 | 19q13.33 | |

| × 3 | 19q13.41 | |

| × 3 | 19p13.12 | |

| Chromosome 22 | ||

| XY | × 4 | 22q13.2 |

| × 2 ~ 3 | 22q11.1q11.22 | |

| × 3 | 22q11.21 | |

| × 3 | 22q13.33 | |

| × 2 ~ 3 | 22q11.1q11.23 | |

| XY | × 3 | 22q11.21 |

Gross chromosome rearrangements were detected by cytogenetic analysis in 5 (~ 2%) out of 300 individuals. Four cases were confirmed by molecular karyotyping. Certainly, further analysis of actual and extended cohort would show additional cases of chromosomal abnormalities associated with epilepsy, which would demonstrate new pathways implicated in the pathogenesis after bioinformatic analysis. Additionally, molecular karyotyping has allowed us the section of 153 CNVs, which might be implicated in epilepsy pathogenesis in our cohort (Table 5). Currently, in silico analysis using an original and established bioinformatic technology [75, 84–87], of these CNVs is performed.

Although the results of our cytogenetic and cytogenomic analysis of the consortium (epilepsy) cohort are extremely preliminary, we decided to share these data with the scientific community inasmuch as it helps to choose future directions in cytogenomic epileptology. It is to note that non-random sex distribution of chromosome-specific CNVs encompassing autosomal genes is observed. One may hypothesize epilepsy-specific gonosome-autosome interactions by non-random genomic loci, which potentially occur through the specificity of intranuclear chromsome/genome organization. Current bioinformatic analyses shows that a significant proportion of CNVs encompasses genes involved in following pathways: cell cycle regulation, programmed cell death, DNA reparation and replication. Among others, mTOR, PI3K-Akt, p53, PTEN, MAPK pathways have been affected. Since these pathways are associated with brain disorders including epilepsy and genome stability maintenance [24, 100–104], somatic mosaicism and chromosome (genome) instability should become an important focus of cytogenomic epileptology.

Somatic mosaicism and chromosome instability: neurocytogenetic (neurocytogenomic) aspects

As noted before, somatic mosaicism for gene mutations is common in epilepsy and seems to play a specific role in the pathogenesis of epileptic disorders, especially when affecting brain tissues/brain foci. Genomic analyses of postoperative samples of the brain in patients suffering from epilepsy have become a common research practice [19, 20, 105, 106]. Currently, several monogenic neurodevelopmental disorders exhibiting epilepsy have been reported to demonstrate brain-specific mosaicism for gene mutations: focal cortical dysplasia—MTOR (1p36.22), TSC1 (9q34.13), TSC2 (16p13.3), DEPDC5 (22q12.2q12.3) [107–110]; hemimegalencephaly—MTOR (1p36.22), AKT3 (1q43q44), PIK3CA (3q26.32), RPS6 (9p22.1), AKT1 (14q32.33) [107, 108, 111, 112]; hypothalamic hamartoma—GLI3 (7p14.1),OFD1 (Xp22.2) [113, 114]; nonlesional focal epilepsy—SLC35A2 (Xp11.23) [115]; Sturge-Weber syndrome (leptomeningeal angiomatosis)—GNAQ (9q21.2) [116]; tuberous sclerosis 16p13.3—(TSC2) [117]. As one may observe, mosaic mutations in these forms of mosaicism affect mTOR and PI3K-Akt pathways as well as pathways of cell cycle regulation and programmed cell death. Since deregulation of these pathways leads to chromosome instability in brain diseases (for review, see [24]), somatic chromosomal mosaicism and instable genome behavior at the chromosomal level are likely to be associated with epilepsy and are able to be at least elements of the epileptic pathogenic cascade.

Somatic chromosomal mosaicism and chromosome instability are common genetic defects detectable in neurodevelopmental cohorts (i.e. high rates of chromosomal mosaicism in children with idiopathic autism and intellectual disability with congenital anomalies and epilepsy) [118, 119]. Moreover, somatic mosaicism may initiate instability, which rates are variable and correlate with phenotypic dynamics (increase in rates of mosaicism/instability → worsening; decrease in rates of mosaicism/instability → improvement) [121–123]. Finally, somatic chromosomal mosaicism and chromosome/genome instability represent an important part of pathogenetic cascades of a wide spectrum of brain disorders, including neurobehavioral, neurodevelopmental, psychiatric, neurological and neurodegenerative conditions [21–25, 124–129]. Thus, cytogenomic research of chromosomal variations in the brain (neurocytogenetic or neurocytogenomic analyses) of individuals with epilepsy has the potential to bring new insights into understanding the etiology.

Genome and chromosome instability in the brain is mainly generated in early ontogeny. The developing human brain is significantly affected by chromosome instability (up to 35% of cells) [130–132]. Normally, cellular population affected by chromosome instability diminishes due to neuronal cell death [133, 134]. During later ontogenetic periods genome/chromosome instability in the brain is generally the result of genetic-environmental interactions (i.e. environmental triggers produce a genomically instable cellular population, which is initially susceptible to the instability due to mutational burden altering genome safeguarding pathways) [24, 135]. These neurocytogenetic observations allow suggesting that studies in cytogenomic epileptology require not only analysis and monitoring of chromosome instability, but also a sophisticated evaluation of genome susceptibility to the instability. If successful, neurocytogenetic (neurocytogenomic) studies are able to lead the way to developing diagnostic approaches for suggesting the presence of brain-specific epilepsy-associated genome instability (for details, see [136]) and therapeutic approaches targeted toward inhibition of brain-specific chromosome instability [137].

The most enigmatic area of neurocytogenetics or neurocytogenomics is nuclear genome organization at chromosomal level in brain diseases. It is important to note that epilepsy was the first disease, in which chromosome behavior was studied in the affected brain [138]. Unfortunately, no additional efforts in this direction were made. In fact, neurocytogenetic analysis of nuclear organization in the unaffected and diseased brain has never been systematically performed. Current molecular cytogenetics and cytogenomics possess technological possibilities to perform high-resolution analysis of chromosomal arrangements and rearrangements in post-mitotic cells of the human brain [139–142]. The analysis of brain-specific chromosomal nuclear organization appears even more attractive taking into account that spatial positioning of chromosomes determines behavior and stability of the nuclear genome in an interphase nucleus [140, 142, 143]. In the light of cytogenomic epileptology, studying chromosomal nuclear organization in postoperative brain samples of individuals with epilepsy might bring new important insights into our understanding of molecular and cellular processes leading to focal brain dysfunction.

Conclusions

Theoretical work of our consortium has allowed us to make some important conclusions, which underlie future directions in cytogenomic epileptology:

Cytogenomic variations require more profound research in epileptic disorders.

More detailed bioinformatic analyses (e.g. application of CNVariome concept and systems analysis) of epilepsy-associated genes are needed in cases of chromosomal abnormalities and CNVs.

Neurocytogenetic (neurocytogenomic) studies of chromosomal variation and instability in postoperative samples are warranted in patients suffering from epileptic disorders.

Cytoepigenomic variations (long contiguous stretches of homozygosity spanning shortly the imprinted loci) should not be left aside in large-scale studies in epilepsy genetics.

Supernumerary marker chromosomes are an important target for studies in cytogenomic epileptology.

Extended complexity of cytogenomic (non-random gene co-localization and clusterization) and “pathwayomic” parameters of epilepsy-associated genes as well as behavior of chromosomal loci in interphase should be a focus of cytogenomic studies in epileptology.

Genotype–phenotype correlations are an important part of cytogenomic studies in epileptology.

Cytogenomic pathway-based classification of epileptic disorders seems to be useful for basic and practical research of epilepsy.

Pathways (e.g. mTOR, PI3K-Akt, p53, PTEN, and MAPK) altered in epilepsy and associated with chromosome and genome instability require profound exploration.

Somatic chromosomal mosaicism is a target for future studies in cytogenomic epileptology.

Studies of chromosomal nuclear organization in postoperative brain samples of individuals with epilepsy appear to become an innovative and perspective area of biomedical research.

The consortium focused on studying cytogenomic (cytogenetic and molecular cytogenetic) aspects of epilepsy has the potential to bring new insights in current epileptology.

Chromosomal abnormalities and CNVs represent an important, albeit poorly explored, genetic causes of epilepsy [13, 14, 21]. The problem of lacking cytogenetic and cytogenomic studies of epilepsy is likely to arise from general decrease in cytogenetic competence [144]. It has been systematically reported that ignoring chromosomal approaches to solving genomic biomedical problems lead to incomplete understanding of mechanisms for genetic diseases [144–146]. The formation of our consortium is basically aimed at incorporating cytogenomic variations to the complemented view of genetic causes of epilepsy. We have preferred to use the term “cytogenomic” for designating the consortium in its initial and established meaning [147]. Despite the fair discussions about the term of cytogenomics [148], our consortium is definitively a cytogenomic one, inasmuch as it is focused on studying genome of individuals suffering from epilepsy by molecular cytogenetic and genomic technologies in the chromosomal context. Thus, we concluded the designation “consortium on cytogenomic epilptology” to be appropriate.

Dedication

Our communication as well as our consortium is dedicated to Professor Yuri B. Yurov, an outstanding researcher in the field of medical genomics, whose contribution to molecular cytogenetics and cytogenomics is hard to estimate [149]. His main research targets were chromosomal abnormalities in brain disorders and genomic variations in the diseased brain. Accordingly, Yuri’s original ideas and findings are consistently used for the work of the consortium.

Author contributions

IYI developed the idea of the communication and got funding. IYI, APG and MAZ wrote the manuscript. IYI, APG, MAZ, NEI, OSK, YMZ, KSV, ERB, IAD, ADK, VVU, DAS, TBAL, MEI, NSI, MMZ, KAS and SGV made important contributions and performed data analysis. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Yurov’s Laboratory of Molecular Genetics and Cytogenomics of the Brain (Mental Health Research Center) is supported by the Government Assignment of the Russian Ministry of Science and Higher Education, Assignment no. AAAA-A19–119040490101-6. Vorsanova’s Laboratory of Molecular Cytogenetics of Neuropsychiatric Diseases (Veltischev Research and Clinical Institute for Pediatrics and Pediatric Surgery of the Pirogov Russian National Research Medical University) by the Government Assignment of the Russian Ministry of Health, Assignment no. 121031000238-1. Research Laboratory of Pathomorphology of the Nervous System (Almazov National Medical Research Centre) by the Government Assignment of the Russian Ministry of Health, Assignment no. 121031000359–3.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Perucca P, Bahlo M, Berkovic SF. The genetics of epilepsy. Annu Rev Genom Hum Genet. 2020;21:205–230. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genom-120219-074937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Knowles JK, Helbig I, Metcalf CS, Lubbers LS, Isom LL, Demarest S, Goldberg EM, George AL, Jr, Lerche H, Weckhuysen S, Whittemore V, Berkovic SF, Lowenstein DH. Precision medicine for genetic epilepsy on the horizon: recent advances, present challenges, and suggestions for continued progress. Epilepsia. 2022;63(10):2461–2475. doi: 10.1111/epi.17332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McMahon JM, Scheffer IE, Nicholl JK, Waters W, Eyre H, Hinton L, Nelson P, Yu S, Dibbens LM, Berkovic SF, Mulley JC. Detection of microchromosomal aberrations in refractory epilepsy: a pilot study. Epileptic Disord. 2010;12(3):192–198. doi: 10.1684/epd.2010.0326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hochstenbach R, Buizer-Voskamp JE, Vorstman JA, Ophoff RA. Genome arrays for the detection of copy number variations in idiopathic mental retardation, idiopathic generalized epilepsy and neuropsychiatric disorders: lessons for diagnostic workflow and research. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2011;135(3–4):174–202. doi: 10.1159/000332928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mulley JC, Mefford HC. Epilepsy and the new cytogenetics. Epilepsia. 2011;52(3):423–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02932.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galizia EC, Srikantha M, Palmer R, Waters JJ, Lench N, Ogilvie CM, Kasperavičiūtė D, Nashef L, Sisodiya SM. Array comparative genomic hybridization: results from an adult population with drug-resistant epilepsy and co-morbidities. Eur J Med Genet. 2012;55(5):342–348. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2011.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Kurinnaia OS, Zelenova MA, Silvanovich AP, Yurov YB. Molecular karyotyping by array CGH in a Russian cohort of children with intellectual disability, autism, epilepsy and congenital anomalies. Mol Cytogenet. 2012;5(1):46. doi: 10.1186/1755-8166-5-46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lengyel A, Pinti É, Pikó H, Kristóf Á, Abonyi T, Némethi Z, Fekete G, Haltrich I. Clinical evaluation of rare copy number variations identified by chromosomal microarray in a Hungarian neurodevelopmental disorder patient cohort. Mol Cytogenet. 2022;15(1):47. doi: 10.1186/s13039-022-00623-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Poot M, van der Smagt JJ, Brilstra EH, Bourgeron T. Disentangling the myriad genomics of complex disorders, specifically focusing on autism, epilepsy, and schizophrenia. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2011;135(3–4):228–240. doi: 10.1159/000334064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niestroj LM, Perez-Palma E, Howrigan DP, Zhou Y, Cheng F, Saarentaus E, Nürnberg P, Stevelink R, Daly MJ, Palotie A, Lal D, Epi25 Collaborative Epilepsy subtype-specific copy number burden observed in a genome-wide study of 17 458 subjects. Brain. 2020;143(7):2106–2118. doi: 10.1093/brain/awaa171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balagué-Dobón L, Cáceres A, González JR. Fully exploiting SNP arrays: a systematic review on the tools to extract underlying genomic structure. Brief Bioinform. 2022;23(2):bbac043. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbac043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Kurinnaia OS, Zelenova MA, Vasin KS, Demidova IA, Kolotii AD, Kravets VS, Iuditskaia ME, Iakushev NS, Soloviev IV, Yurov YB. Molecular cytogenetic and cytopostgenomic analysis of the human genome. Res Results Biomed. 2022;8(4):412–423. doi: 10.18413/2658-6533-2022-8-4-0-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gersen SL, Keagle MB, editors. The principles of clinical cytogenetics. Trenton: Humana Press Inc; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Yurov YB. Chromosomal variation in mammalian neuronal cells: known facts and attractive hypotheses. Int Rev Cytol. 2006;249:143–191. doi: 10.1016/S0074-7696(06)49003-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poduri A, Evrony GD, Cai X, Walsh CA. Somatic mutation, genomic variation, and neurological disease. Science. 2013;341(6141):1237758. doi: 10.1126/science.1237758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.D'Gama AM, Walsh CA. Somatic mosaicism and neurodevelopmental disease. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21(11):1504–1514. doi: 10.1038/s41593-018-0257-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye Z, McQuillan L, Poduri A, Green TE, Matsumoto N, Mefford HC, Scheffer IE, Berkovic SF, Hildebrand MS. Somatic mutation: the hidden genetics of brain malformations and focal epilepsies. Epilepsy Res. 2019;155:106161. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2019.106161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jourdon A, Fasching L, Scuderi S, Abyzov A, Vaccarino FM. The role of somatic mosaicism in brain disease. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2020;65:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2020.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Niestroj LM, May P, Artomov M, Kobow K, Coras R, Pérez-Palma E, Altmüller J, Thiele H, Nürnberg P, Leu C, Palotie A, Daly MJ, Klein KM, Beschorner R, Weber YG, Blümcke I, Lal D. Assessment of genetic variant burden in epilepsy-associated brain lesions. Eur J Hum Genet. 2019;27(11):1738–1744. doi: 10.1038/s41431-019-0484-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bedrosian TA, Miller KE, Grischow OE, Schieffer KM, LaHaye S, Yoon H, Miller AR, Navarro J, Westfall J, Leraas K, Choi S, Williamson R, Fitch J, Kelly BJ, White P, Lee K, McGrath S, Cottrell CE, Magrini V, Leonard J, Pindrik J, Shaikhouni A, Boué DR, Thomas DL, Pierson CR, Wilson RK, Ostendorf AP, Mardis ER, Koboldt DC. Detection of brain somatic variation in epilepsy-associated developmental lesions. Epilepsia. 2022;63(8):1981–1997. doi: 10.1111/epi.17323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Kurinnaia OS, Kutsev SI, Yurov YB. Somatic mosaicism in the diseased brain. Mol Cytogenet. 2022;15(1):45. doi: 10.1186/s13039-022-00624-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Yurov YB. Single cell genomics of the brain: focus on neuronal diversity and neuropsychiatric diseases. Curr Genomics. 2012;13(6):477–488. doi: 10.2174/138920212802510439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Costantino I, Nicodemus J, Chun J. Genomic mosaicism formed by somatic variation in the aging and diseased brain. Genes (Basel) 2021;12(7):1071. doi: 10.3390/genes12071071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Kurinnaia OS, Zelenova MA, Vasin KS, Yurov YB. Causes and consequences of genome instability in psychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases. Mol Biol (Mosk) 2021;55(1):42–53. doi: 10.31857/S0026898421010158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iourov IY, Yurov YB, Vorsanova SG, Kutsev SI. Chromosome instability, aging and brain diseases. Cells. 2021;10(5):1256. doi: 10.3390/cells10051256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maury EA, Walsh CA. Somatic copy number variants in neuropsychiatric disorders. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2021;68:9–17. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2020.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yurov YB, Vorsanova SG, Iourov IY. GIN’n’CIN hypothesis of brain aging: deciphering the role of somatic genetic instabilities and neural aneuploidy during ontogeny. Mol Cytogenet. 2009;2:23. doi: 10.1186/1755-8166-2-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yurov YB, Vorsanova SG, Iourov IY. Ontogenetic variation of the human genome. Curr Genom. 2010;11(6):420–425. doi: 10.2174/138920210793175958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Andriani GA, Vijg J, Montagna C. Mechanisms and consequences of aneuploidy and chromosome instability in the aging brain. Mech Ageing Dev. 2017;161(PtA):19–36. doi: 10.1016/j.mad.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.EpiPM Consortium A roadmap for precision medicine in the epilepsies. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(12):1219–1228. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00199-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liehr T. Cytogenetics and molecular cytogenetics. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bahi-Buisson N, Guttierrez-Delicado E, Soufflet C, Rio M, Daire VC, Lacombe D, Héron D, Verloes A, Zuberi S, Burglen L, Afenjar A, Moutard ML, Edery P, Novelli A, Bernardini L, Dulac O, Nabbout R, Plouin P, Battaglia A. Spectrum of epilepsy in terminal 1p36 deletion syndrome. Epilepsia. 2008;49(3):509–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01424.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greco M, Ferrara P, Farello G, Striano P, Verrotti A. Electroclinical features of epilepsy associated with 1p36 deletion syndrome: a review. Epilepsy Res. 2018;139:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2017.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chih-Ping C, Schu-Rern C, Peih-Shan W, Shin-Wen C, Fang-Tzu W, Wayseen W. Molecular cytogenetic characterization of a de novo chromosome 1q41-q42.11 microdeletion of paternal origin in a 15-year-old boy with mental retardation, developmental delay, autism and congenital heart defects. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2021;60(2):341–344. doi: 10.1016/j.tjog.2021.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pavone P, Falsaperla R, Rizzo R, Praticò AD, Ruggieri M. Chromosome 2p15-p16.1 microduplication in a boy with congenital anomalies: is it a distinctive syndrome? Eur J Med Genet. 2019;62(1):47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2018.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coyan AG, Dyer LM. 3q29 microduplication syndrome: clinical and molecular description of eleven new cases. Eur J Med Genet. 2020;63(12):104083. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2020.104083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pollak RM, Zinsmeister MC, Murphy MM, Zwick ME, Emory 3q29 Project. Mulle JG. New phenotypes associated with 3q29 duplication syndrome: results from the 3q29 registry. Am J Med Genet A. 2020;182(5):1152–1166. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.61540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kuriko K, Katsumi I, Kazumasa O, Noriko K, Takeshi O, Yasuhisa T, Yasuhiro S, Keiichi O. Epilepsy in Wolf-Hirschhorn Syndrome (4p-) Epilepsia. 2005;46(1):150–155. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.02804.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fernández Hernández L, Alcántara Ortigoza MA, Ramos Angeles SE, González-Del AA. Cleft lip palate in a patient with 5q14.3 deletion syndrome: a possible unreported feature? Cytogenet Genome Res. 2021;161(12):556–563. doi: 10.1159/000521225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hanna MD, Moretti PN, de Oliveira CP, Rosa MT, Versiani BR, de Oliveira SF, Pic-Taylor A, Mazzeu JF. Defining the critical region for intellectual disability and brain malformations in 6q27 microdeletions. Mol Syndromol. 2019;10(4):202–208. doi: 10.1159/000501008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Francesco N, Giacomo G, Alberto S, Salvatore S, Pasquale S, Chiara P, Maria VS, Gerhard K, Giuseppe C, Dario P, Elena F, Stefano D’A, Alberto V. Epilepsy is a possible feature in Williams-Beuren syndrome patients harboring typical deletions of the 7q11.23 critical region. Am J Med Genet A. 2016;170(1):148–155. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.37410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rezazadeh A, Borlot F, Faghfoury H, Andrade DM. Genetic generalized epilepsy in three siblings with 8q21.13-q22.2 duplication. Seizure. 2017;48:57–61. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2017.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bonaglia MC, Giorda R, Tenconi R, Pessina M, Pramparo T, Borgatti R, Zuffardi O. A 2.3 Mb duplication of chromosome 8q24.3 associated with severe mental retardation and epilepsy detected by standard karyotype. Eur J Hum Genet. 2005;13(5):586–591. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Nicita F, Ulgiati F, Bernardini L, Garone G, Papetti L, Novelli A, Spalice A. Early myoclonic encephalopathy in 9q33-q34 deletion encompassing STXBP1 and SPTAN1. Ann Hum Genet. 2015;79(3):209–217. doi: 10.1111/ahg.12106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Matsumoto H, Zaha K, Nakamura Y, Hayashi S, Inazawa J, Nonoyama S. Chromosome 9q33q34 microdeletion with early infantile epileptic encephalopathy, severe dystonia, abnormal eye movements, and nephroureteral malformations. Pediatr Neurol. 2014;51(1):170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.pediatrneurol.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shimojima K, Okamoto N, Goel H, Ondo Y, Yamamoto T. Familial 9q33q34 microduplication in siblings with developmental disorders and macrocephaly. Eur J Med Genet. 2017;60(12):650–654. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2017.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Campbell IM, Yatsenko SA, Hixson P, Reimschisel T, Thomas M, Wilson W, Dayal U, Wheless JW, Crunk A, Curry C, Parkinson N, Fishman L, Riviello JJ, Nowaczyk MJ, Zeesman S, Rosenfeld JA, Bejjani BA, Shaffer LG, Cheung SW, Lupski JR, Stankiewicz P, Scaglia F. Novel 9q34.11 gene deletions encompassing combinations of four Mendelian disease genes: STXBP1, SPTAN1, ENG, and TOR1A. Genet Med. 2012;14(10):868–876. doi: 10.1038/gim.2012.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vari MS, Traverso M, Bellini T, Madia F, Pinto F, Minetti C, Striano P, Zara F. De novo 12q22.q23.3 duplication associated with temporal lobe epilepsy. Seizure. 2017;50:80–82. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2017.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brunetti-Pierri N, Paciorkowski AR, Ciccone R, Della Mina E, Bonaglia MC, Borgatti R, Schaaf CP, Sutton VR, Xia Z, Jelluma N, Ruivenkamp C, Bertrand M, de Ravel TJ, Jayakar P, Belli S, Rocchetti K, Pantaleoni C, D'Arrigo S, Hughes J, Cheung SW, Zuffardi O, Stankiewicz P. Duplications of FOXG1 in 14q12 are associated with developmental epilepsy, mental retardation, and severe speech impairment. Eur J Hum Genet. 2011;19(1):102–107. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2010.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vaisfeld A, Spartano S, Gobbi G, Vezzani A, Neri G. Chromosome 14 deletions, rings, and epilepsy genes: a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma. Epilepsia. 2021;62(1):25–40. doi: 10.1111/epi.16754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Giovannini S, Marangio L, Fusco C, Scarano A, Frattini D, Della Giustina E, Zollino M, Neri G, Gobbi G. Epilepsy in ring 14 syndrome: a clinical and EEG study of 22 patients. Epilepsia. 2013;54(12):2204–2213. doi: 10.1111/epi.12393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vendrame M, Maski KP, Chatterjee M, Heshmati A, Krishnamoorthy K, Tan WH, Kothare SV. Epilepsy in Prader-Willi syndrome: clinical characteristics and correlation to genotype. Epilepsy Behav. 2010;19(3):306–310. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Samanta D. Epilepsy in Angelman syndrome: a scoping review. Brain Dev. 2021;43(1):32–44. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2020.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Damiano JA, Mullen SA, Hildebrand MS, Bellows ST, Lawrence KM, Arsov T, Dibbens L, Major H, Dahl HH, Mefford HC, Darbro BW, Scheffer IE, Berkovic SF. Evaluation of multiple putative risk alleles within the 15q13.3 region for genetic generalized epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2015;117:70–73. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2015.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Whitney R, Nair A, McCready E, Keller AE, Adil IS, Aziz AS, Borys O, Siu K, Shah C, Meaney BF, Jones K, Ramachandran NR. The spectrum of epilepsy in children with 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome. Seizure. 2021;92:221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2021.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen CP, Lin SP, Tsai FJ, Chern SR, Lee CC, Wang W. A 5.6-Mb deletion in 15q14 in a boy with speech and language disorder, cleft palate, epilepsy, a ventricular septal defect, mental retardation and developmental delay. Eur J Med Genet. 2008;51(4):368–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Huynh MT, Lambert AS, Tosca L, Petit F, Philippe C, Parisot F, Benoît V, Linglart A, Brisset S, Tran CT, Tachdjian G, Receveur A. 15q24.1 BP4-BP1 microdeletion unmasking paternally inherited functional polymorphisms combined with distal 15q24.2q24.3 duplication in a patient with epilepsy, psychomotor delay, overweight, ventricular arrhythmia. Eur J Med Genet. 2018;61(8):459–464. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2018.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu JY, Kasperavičiūtė D, Martinian L, Thom M, Sisodiya SM. Neuropathology of 16p13.11 deletion in epilepsy. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(4):e34813. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Falsaperla R, Marino SD, Marino S, Pavone P. Electroclinical pattern and epilepsy evolution in an infant with Miller-Dieker Syndrome. J Pediatr Neurosci. 2018;13(3):302–307. doi: 10.4103/jpn.jpn_182_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hardies K, Weckhuysen S, Peeters E, Holmgren P, Van Esch H, De Jonghe P, Van Paesschen W, Suls A. Duplications of 17q12 can cause familial fever-related epilepsy syndromes. Neurology. 2013;81(16):1434–1440. doi: 10.1212/wnl.0b013e3182a84163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cerminara C, Lo Castro A, D'Argenzio L, Galasso C, Curatolo P. Epilepsy and deletion syndromes of chromosome 18: do not forget the short arm! Epilepsia. 2008;49(10):1813–1814. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01662.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Auvin S, Holder-Espinasse M, Lamblin MD, Andrieux J. Array-CGH detection of a de novo 0.7-Mb deletion in 19p13.13 including CACNA1A associated with mental retardation and epilepsy with infantile spasms. Epilepsia. 2009;50(11):2501–2503. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vignoli A, Bisulli F, Darra F, Mastrangelo M, Barba C, Giordano L, Turner K, Zambrelli E, Chiesa V, Bova S, Fiocchi I, Peron A, Naldi I, Milito G, Licchetta L, Tinuper P, Guerrini R, Dalla Bernardina B, Canevini MP. Epilepsy in ring chromosome 20 syndrome. Epilepsy Res. 2016;128:83–93. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2016.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bayat M, Bayat A. Neurological manifestation of 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Neurol Sci. 2022;43(3):1695–1700. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05825-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ishikawa N, Kobayashi Y, Fujii Y, Yamamoto T, Kobayashi M. Late-onset epileptic spasms in a patient with 22q13.3 deletion syndrome. Brain Dev. 2016;38(1):109–112. doi: 10.1016/j.braindev.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Magini P, Scarano E, Donati I, Sensi A, Mazzanti L, Perri A, Tamburrino F, Mongelli P, Percesepe A, Visconti P, Parmeggiani A, Seri M, Graziano C. Challenges in the clinical interpretation of small de novo copy number variants in neurodevelopmental disorders. Gene. 2019;20(706):162–171. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2019.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cope H, Barseghyan H, Bhattacharya S, Fu Y, Hoppman N, Marcou C, Walley N, Rehder C, Deak K, Alkelai A, Undiagnosed Diseases Network. Vilain E, Shashi V. Detection of a mosaic CDKL5 deletion and inversion by optical genome mapping ends an exhaustive diagnostic odyssey. Mol Genet Genom Med. 2021;9(7):e1665. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.1665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Voinova VY, Kurinnaia OS, Zelenova MA, Demidova IA, Yurov YB. Xq28 (MECP2) microdeletions are common in mutation-negative females with Rett syndrome and cause mild subtypes of the disease. Mol Cytogenet. 2013;6(1):53. doi: 10.1186/1755-8166-6-53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Vorsanova SG, Yurov YB, Soloviev IV, Iourov IY. Molecular cytogenetic diagnosis and somatic genome variations. Curr Genom. 2010;11(6):440–446. doi: 10.2174/138920210793176010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Campbell IM, Shaw CA, Stankiewicz P, Lupski JR. Somatic mosaicism: implications for disease and transmission genetics. Trends Genet. 2015;31(7):382–392. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2015.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Yurov YB, Kutsev SI. Ontogenetic and pathogenetic views on somatic chromosomal mosaicism. Genes (Basel) 2019;10(5):379. doi: 10.3390/genes10050379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Coppola A, Cellini E, Stamberger H, Saarentaus E, Cetica V, Lal D, Djémié T, Bartnik-Glaska M, Ceulemans B, Helen Cross J, Deconinck T, Masi S, Dorn T, Guerrini R, Hoffman-Zacharska D, Kooy F, Lagae L, Lench N, Lemke JR, Lucenteforte E, Madia F, Mefford HC, Morrogh D, Nuernberg P, Palotie A, Schoonjans AS, Striano P, Szczepanik E, Tostevin A, Vermeesch JR, Van Esch H, Van Paesschen W, Waters JJ, Weckhuysen S, Zara F, De Jonghe P, Sisodiya SM, Marini C, EuroEPINOMICS-RES Consortium. EpiCNV Consortium Diagnostic implications of genetic copy number variation in epilepsy plus. Epilepsia. 2019;60(4):689–706. doi: 10.1111/epi.14683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Collins RL, Glessner JT, Porcu E, Lepamets M, Brandon R, Lauricella C, Han L, Morley T, Niestroj LM, Ulirsch J, Everett S, Howrigan DP, Boone PM, Fu J, Karczewski KJ, Kellaris G, Lowther C, Lucente D, Mohajeri K, Nõukas M, Nuttle X, Samocha KE, Trinh M, Ullah F, Võsa U, Epi25 Consortium. Estonian Biobank Research Team. Hurles ME, Aradhya S, Davis EE, Finucane H, Gusella JF, Janze A, Katsanis N, Matyakhina L, Neale BM, Sanders D, Warren S, Hodge JC, Lal D, Ruderfer DM, Meck J, Mägi R, Esko T, Reymond A, Kutalik Z, Hakonarson H, Sunyaev S, Brand H, Talkowski ME. A cross-disorder dosage sensitivity map of the human genome. Cell. 2022;185(16):3041–3055. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.06.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Walker LE, Mirza N, Yip VLM, Marson AG, Pirmohamed M. Personalized medicine approaches in epilepsy. J Intern Med. 2015;277(2):218–234. doi: 10.1111/joim.12322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Yurov YB. The variome concept: focus on CNVariome. Mol Cytogenet. 2019;12:52. doi: 10.1186/s13039-019-0467-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wang TS, Tsai WH, Tsai LP, Wong SB. Clinical characteristics and epilepsy in genomic imprinting disorders: Angelman syndrome and Prader-Willi syndrome. Ci Ji Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2019;32(2):137–144. doi: 10.4103/tcmj.tcmj_103_19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Korostelev SA, Zelenova MA, Yurov YB. Long contiguous stretches of homozygosity spanning shortly the imprinted loci are associated with intellectual disability, autism and/or epilepsy. Mol Cytogenet. 2015;8:77. doi: 10.1186/s13039-015-0182-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Zelenova MA, Vasin KS, Kurinnaia OS, Korostelev SA, Yurov YB. Epigenomic variations manifesting as a loss of heterozygosity affecting imprinted genes represent a molecular mechanism of autism spectrum disorders and intellectual disability in children. Zh Nevrol Psikhiatr Im S S Korsakova. 2019;119(5):91–97. doi: 10.17116/jnevro201911905191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hu Q, Chai H, Shu W, Li P. Human ring chromosome registry for cases in the Chinese population: re-emphasizing cytogenomic and clinical heterogeneity and reviewing diagnostic and treatment strategies. Mol Cytogenet. 2018;11:19. doi: 10.1186/s13039-018-0367-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Yurov YB, Zelenova MA, Kurinnaia OS, Vasin KS, Kutsev SI. The cytogenomic “theory of everything”: chromohelkosis may underlie chromosomal instability and mosaicism in disease and aging. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(21):8328. doi: 10.3390/ijms21218328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Liehr T. Small supernumerary marker chromosomes: a guide for human geneticist and clinicians. Berlin: Springer Verlag; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liehr T, Al-Rikabi A. Mosaicism: reason for normal phenotypes in carriers of small supernumerary marker chromosomes with known adverse outcome. A systematic review. Front Genet. 2019;10:1131. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.01131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Battaglia A, Gurrieri F, Bertini E, Bellacosa A, Pomponi MG, Paravatou-Petsotas M, Mazza S, Neri G. The inv dup(15) syndrome: a clinically recognizable syndrome with altered behavior, mental retardation, and epilepsy. Neurology. 1997;48(4):1081–1086. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.4.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Yurov YB. In silico molecular cytogenetics: a bioinformatic approach to prioritization of candidate genes and copy number variations for basic and clinical genome research. Mol Cytogenet. 2014;7(1):98. doi: 10.1186/s13039-014-0098-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yurov YB, Vorsanova SG, Iourov IY. Network-based classification of molecular cytogenetic data. Curr Bioinform. 2017;12:27–33. doi: 10.2174/1574893611666160606165119. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Vorsanova SG, Yurov YB, Iourov IY. Neurogenomic pathway of autism spectrum disorders: linking germline and somatic mutations to genetic-environmental interactions. Curr Bioinform. 2017;12:19–26. doi: 10.2174/1574893611666160606164849. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Yurov YB. Systems cytogenomics: are we ready yet? Curr Genom. 2021;22(2):75–78. doi: 10.2174/1389202922666210219112419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Voinova VY, Yurov YB. 3p22.1p21.31 microdeletion identifies CCK as Asperger syndrome candidate gene and shows the way for therapeutic strategies in chromosome imbalances. Mol Cytogenet. 2015;8:82. doi: 10.1186/s13039-015-0185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wang J, Lin ZJ, Liu L, Xu HQ, Shi YW, Yi YH, He N, Liao WP. Epilepsy-associated genes. Seizure. 2017;44:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2016.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Noebels J. Pathway-driven discovery of epilepsy genes. Nat Neurosci. 2015;18(3):344–350. doi: 10.1038/nn.3933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Iourov IY, Vorsanova SG, Yurov YB. Pathway-based classification of genetic diseases. Mol Cytogenet. 2019;12:4. doi: 10.1186/s13039-019-0418-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Browne F, Wang H, Zheng H. A computational framework for the prioritization of disease-gene candidates. BMC Genom. 2015;16(Suppl 9):S2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-16-S9-S2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Iourov IY. Cytopostgenomics: what is it and how does it work? Curr Genomics. 2019;20(2):77–78. doi: 10.2174/138920292002190422120524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Scheffer IE, Berkovic S, Capovilla G, Connolly MB, French J, Guilhoto L, Hirsch E, Jain S, Mathern GW, Moshé SL, Nordli DR, Perucca E, Tomson T, Wiebe S, Zhang YH, Zuberi SM. ILAE classification of the epilepsies: position paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology. Epilepsia. 2017;58(4):512–521. doi: 10.1111/epi.13709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Krey I, Platzer K, Esterhuizen A, Berkovic SF, Helbig I, Hildebrand MS, Lerche H, Lowenstein D, Møller RS, Poduri A, Sadleir L, Sisodiya SM, Weckhuysen S, Wilmshurst JM, Weber Y, Lemke JR, Berkovic SF, Cross JH, Helbig I, Lerche H, Lowenstein D, Mefford HC, Perucca P, Tan NC, Caglayan H, Helbig K, Singh G, Weber Y, Weckhuysen S. Current practice in diagnostic genetic testing of the epilepsies. Epileptic Disord. 2022;24(5):765–786. doi: 10.1684/epd.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mullen SA, Berkovic SF. ILAE Genetics Commission. Genetic generalized epilepsies. Epilepsia. 2018;59(6):1148–1153. doi: 10.1111/epi.14042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Vorsanova SG, Yurov IY, Demidova IA, Voinova-Ulas VY, Kravets VS, Solov’ev IV, Gorbachevskaya NL, Yurov YB. Variability in the heterochromatin regions of the chromosomes and chromosomal anomalies in children with autism: identification of genetic markers of autistic spectrum disorders. Neurosci Behav Physiol. 2007;37(6):553–558. doi: 10.1007/s11055-007-0052-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Vorsanova SG, Voinova VY, Yurov IY, Kurinnaya OS, Demidova IA, Yurov YB. Cytogenetic, molecular-cytogenetic, and clinical-genealogical studies of the mothers of children with autism: a search for familial genetic markers for autistic disorders. Neurosci Behav Physiol. 2010;40(7):745–756. doi: 10.1007/s11055-010-9321-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Demidova IA, Vorsanova SG, Kurinnaia OS, Vasin KS, Voinova VY, Zelenova MA, Kolotii AD, Kravets VS, Bulatnikova MA, Yablonskaya MI, Sharonin VO, Yurov YB, Iourov IY. Molecular karyotyping of chromosomal anomalies and copy number variations (CNVs) in idiopathic forms of intellectual disability and epilepsy. Res Results Biomed. 2020;6(2):172–197. doi: 10.18413/2658-6533-2020-6-2-0-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Morrison RS, Kinoshita Y. The role of p53 in neuronal cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2000;7(10):868–879. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Garcia-Junco-Clemente P, Golshani P. PTEN: a master regulator of neuronal structure, function, and plasticity. Commun Integr Biol. 2014;7(1):e28358. doi: 10.4161/cib.28358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Pernice HF, Schieweck R, Kiebler MA, Popper B. mTOR and MAPK: from localized translation control to epilepsy. BMC Neurosci. 2016;17(1):73. doi: 10.1186/s12868-016-0308-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Dobyns WB, Mirzaa GM. Megalencephaly syndromes associated with mutations of core components of the PI3K-AKT-MTOR pathway: PIK3CA, PIK3R2, AKT3, and MTOR. Am J Med Genet C Semin Med Genet. 2019;181(4):582–590. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.31736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lee WS, Baldassari S, Stephenson SEM, Lockhart PJ, Baulac S, Leventer RJ. Cortical Dysplasia and the mTOR pathway: how the study of human brain tissue has led to insights into epileptogenesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(3):1344. doi: 10.3390/ijms23031344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Sim NS, Ko A, Kim WK, Kim SH, Kim JS, Shim KW, Aronica E, Mijnsbergen C, Spliet WGM, Koh HY, Kim HD, Lee JS, Kim DS, Kang HC, Lee JH. Precise detection of low-level somatic mutation in resected epilepsy brain tissue. Acta Neuropathol. 2019;138(6):901–912. doi: 10.1007/s00401-019-02052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.López-Rivera JA, Leu C, Macnee M, Khoury J, Hoffmann L, Coras R, Kobow K, Bhattarai N, Pérez-Palma E, Hamer H, Brandner S, Rössler K, Bien CG, Kalbhenn T, Pieper T, Hartlieb T, Butler E, Genovese G, Becker K, Altmüller J, Niestroj LM, Ferguson L, Busch RM, Nürnberg P, Najm I, Blümcke I, Lal D. The genomic landscape across 474 surgically accessible epileptogenic human brain lesions. Brain. 2022 doi: 10.1093/brain/awac376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Park SM, Lim JS, Ramakrishina S, Kim SH, Kim WK, Lee J, Kang HC, Reiter JF, Kim DS, Kim HH, Lee JH. Brain somatic mutations in MTOR disrupt neuronal ciliogenesis, leading to focal cortical dyslamination. Neuron. 2018;99(1):83–97.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2018.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.D’Gama AM, Woodworth MB, Hossain AA, Bizzotto S, Hatem NE, LaCoursiere CM, Najm I, Ying Z, Yang E, Barkovich AJ, Kwiatkowski DJ, Vinters HV, Madsen JR, Mathern GW, Blümcke I, Poduri A, Walsh CA. Somatic mutations activating the MTOR pathway in dorsal telencephalic progenitors cause a continuum of cortical dysplasias. Cell Rep. 2017;21(13):3754–3766. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.11.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Lim JS, Gopalappa R, Kim SH, Ramakrishna S, Lee M, Kim WI, Kim J, Park SM, Lee J, Oh JH, Kim HD, Park CH, Lee JS, Kim S, Kim DS, Han JM, Kang HC, Kim HH, Lee JH. Somatic mutations in TSC1 and TSC2 cause focal cortical dysplasia. Am J Hum Genet. 2017;100(3):454–472. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.01.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ribierre T, Deleuze C, Bacq A, Baldassari S, Marsan E, Chipaux M, Muraca G, Roussel D, Navarro V, Leguern E, Miles R, Baulac S. Second-hit mosaic mutation in mTORC1 repressor DEPDC5 causes focal cortical dysplasia-associated epilepsy. J Clin Investig. 2018;128(6):2452–2458. doi: 10.1172/JCI99384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lee JH, Huynh M, Silhavy JL, Kim S, Dixon-Salazar T, Heiberg A, Scott E, Bafna V, Hill KJ, Collazo A, Funari V, Russ C, Gabriel SB, Mathern GW, Gleeson JG. De novo somatic mutations in components of the PI3K-AKT3-mTOR pathway cause hemimegalencephaly. Nat Genet. 2012;44(8):941–945. doi: 10.1038/ng.2329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pelorosso C, Watrin F, Conti V, Buhler E, Gelot A, Yang X, Mei D, McEvoy-Venneri J, Manent JB, Cetica V, Ball LL, Buccoliero AM, Vinck A, Barba C, Gleeson JG, Guerrini R, Represa A. Somatic double-hit in MTOR and RPS6 in hemimegalencephaly with intractable epilepsy. Hum Mol Genet. 2019;28(22):3755–3765. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddz194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hildebrand MS, Griffin NG, Damiano JA, Cops EJ, Burgess R, Ozturk E, Jones NC, Leventer RJ, Freeman JL, Harvey AS, Sadleir LG, Scheffer IE, Major H, Darbro BW, Allen AS, Goldstein DB, Kerrigan JF, Berkovic SF, Heinzen EL. Mutations of the sonic hedgehog pathway underlie hypothalamic hamartoma with gelastic epilepsy. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;99(2):423–429. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]