Abstract

Currently, the selective activation of C(sp3)–F bonds and C–C bonds constitute one of the most widely used procedures for the synthesis of high-value products that range from pharmaceuticals to agrochemical applications. While numerous examples of these two methods have been reported in their respective fields, the processes which merge the activation of both single C(sp3)-F bonds and C–C bonds in one step still remain elusive. Here, we demonstrate the controllable defluoroalkylation–distal functionalization of trifluoromethylarenes with unactivated alkenes via distal heteroaryl migration. This is proposed to proceed via tandem C(sp3)–F and C–C bond cleavage using visible-light photoredox catalysis combined with Lewis acid activation. This strategy provides facile and flexible access to multiply functionalized α,α-difluorobenzylic ketones in useful yields (up to 88%) under mild conditions. The products can be further transformed into other valuable compounds, demonstrating the method’s utility.

Subject terms: Synthetic chemistry methodology, Photocatalysis

The radical C–F cleavage of fluoroalkanes offers a valuable method for the synthesis of fluorinated products. Here, photoredox catalysis promotes tandem intermolecular defluoroalkylation/intramolecular heteroaryl migration of unactivated alkenes to yield difluorobenzyl ketones, proposed to proceed via a radical mechanism.

Introduction

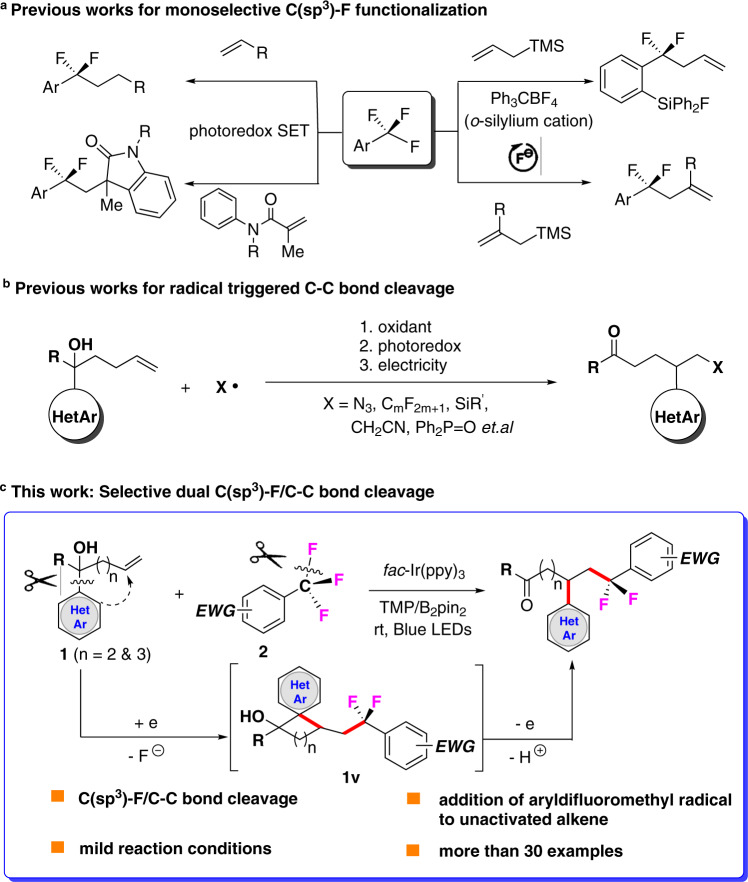

To address environmental concerns and achieve high step economy, the activation of C(sp3)–F bonds is one of the most green and efficient methods for accessing target fluorine compounds1. Therefore, the development of novel and efficient synthetic approaches for the direct functionalization of unactivated C(sp3)–F bonds from easily available reagents such as trifluoromethylarenes (ArCF3) is of vital importance. However, the reactivity and selectivity of this process are limited due to the high energy of C(sp3)–F cleavage (∼115 kcal/mol for PhCF3) and the shielding effect of the three F atoms2. Conventional methods for the cleavage of the C–F bonds in ArCF3 include electrochemical reduction3,4, the use of low-valent metals5–7, and the application of frustrated Lewis pairs8,9. However, due to the gradual decrease in the strength of the remaining C(sp3)–F bonds (99 kcal/mol for PhCFH2), it becomes exceedingly difficult to avoid multiple defluorinations10. Compared to examples in which all three C(sp3)–F bonds in ArCF3 are cleaved without selectivity, few examples of single C (sp3)–F bond cleavage in ArCF3 have been reported11. Importantly, several appealing strategies have been established for the selective cleavage of a single C(sp3)–F bond in Ar–CF3 substrates, enabling efficient access to valuable ArCF2R derivatives (Fig. 1a). For instance, Yoshida and co-workers demonstrated the cleavage of a single C(sp3)–F bond accompanied by the transformation of F atom into an ortho-silylium cation, providing an aryldifluoromethyl cation that can react with various nucleophilic species12. Recently, Bandar’s group reported a fluoride-initiated sequential allylation/derivatization reaction for the construction of diverse α,α-difluorobenzylic compounds13. Photocatalysis has also found applications in this field. Gschwind and König disclosed the photocatalytic single C(sp3)–F functionalization of ArCF3 with N-aryl acrylamides via photocatalysis combined with Lewis acid activation14. Moreover, Jui and co-workers reported the photoredox-catalyzed intermolecular defluorinative coupling of ArCF3 with unactivated alkenes15,16. Despite these achievements, general and mild strategies for defluoroalkylation that allow the rapid activation of single C(sp3)–F bonds from easily available ArCF3 remain elusive.

Fig. 1. Selective functionalization of C(sp3)–F and C–C bonds.

a Monoselective C(sp3)–F functionalization. b Radical triggered C–C bond cleavage. c Selective dual C(sp3)–F/C–C bond cleavage.

On the other hand, the cleavage of inert C–C single bonds has enriched the synthetic arsenal for the synthesis of complex bioactive molecules17. In contrast to conventional transition-metal catalysis, which is restricted by harsh reaction conditions and the need for costly catalysts, controllable radical-medicated C–C bond activation overcomes the above problems of transition-metal catalysis while providing excellent atom and step economies18. In particular, the radical-triggered cleavage of C–C bonds via heteroaryl group migration is an attractive approach in modern organic synthesis19–24. Interestingly, Zhu and co-workers recently reported the radical-triggered fragmentation of unstrained C–C bonds via the migration of distal functional groups (Fig. 1b)25,26. Meanwhile, we reported the sulfonyl radical-triggered difunctionalization of alkenes via remote heteroaryl ipso-migration under electrochemical conditions27. Prompted by these results, our group aims to develop novel and general methods to synthesize valuable aryldifluoromethyl derivatives (ArCF2R) via selective C(sp3)–F and C–C bond activation under mild conditions. Since ArCF2R compounds can be obtained from available ArCF3 compounds via selective single C(sp3)–F bond cleavage, we questioned whether the aryldifluoromethyl radical (ArCF2) generated photocatalytically in combination with Lewis acid activation could be captured by the unactivated olefins on the tertiary alcohol 1 and trigger the distal migration of the heteroaryl group via the cyclic intermediate 1v followed by oxidation and deprotonation to give the corresponding α,α-difluorobenzylic ketones (Fig. 1c). Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, the sequential activation of an inert C(sp3)–F/C–C bond-triggered multiple-cascade process for the divergent construction of complex skeletons has not been reported. Herein, we report the development of such a transformation that involves tandem C(sp3)–F and C–C bond functionalization via visible-light photoredox catalysis together with Lewis acid activation.

Results

Reaction optimization

We commenced our investigation by choosing 1-(benzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)-1-phenylpent-4-en-1-ol (1a) and 4-trifluoromethylbenzonitrile (2a) as model substrates to test the reaction conditions. To our delight, by using fac-Ir(ppy)3 [for Ir(III)/Ir(II), Ered = −2.19 V vs. saturated calomel electrode (SCE)]14 as the photocatalyst, bis(pinacolato)diboron (B2pin2) and 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine (TMP) as additives, and 1,2-dichloroethane (DCE) as the solvent, the desired heteroaryl-migrated product 3a was obtained in 84% yield (Table 1, entry 1). X-ray diffraction analysis of the heteroaryl-migrated product of 3a confirmed the structural assignment of the reaction products (for details, see the Supplementary Fig. 2). Other transition-metal photocatalysts (PC1–PC8), including Ir(ppy)2(dtbbpy)PF6 (PC1), Ir[{dF(CF3)ppy}2(dtbbpy)]PF6 (PC2), and Ir(dmppy)2(dtbbpy)PF6 (PC3), were not suitable for this transformation (Table 1, entry 2). It should be noted that the combination of B2pin2 and TMP was indispensable for this reaction, a lower reaction efficiency was observed in the absence of either B2pin2 or TMP (Table 1, entries 3 and 4). The effect of the solvent was also explored. Compared to DCE, the use of THF (Tetrahydrofuran), DMPU (1,3-Dimethyl-Tetrahydropyrimidin-2(1H)-one), and MeOH as solvents resulted in lower yields (Table 1, entries 5–7). However, the addition of 0.2 mL of water led to a decrease in reaction yield (Table 1, entry 8). Furthermore, the Ir catalyst and blue-light irradiation were crucial to this transformation, as evidenced by the dramatic decrease in efficiency when the reaction was carried out without either the Ir catalyst or blue-light irradiation (Table 1, entries 9 and 10). Finally, under the optimum conditions, the reaction of 1a (2.0 equiv), 2a (1.0 equiv), fac-Ir(ppy)3 (1.0 mol%), B2pin2 (3.0 equiv), and TMP (3.0 equiv) in DCE at 25 °C under irradiation from a 50-W blue-light-emitting diode (455 nm) for 24 h provided the desired product 3a in 84% isolated yield.

Table 1.

Optimization of the reaction conditionsa.

| Entry | Deviation from the standard conditions | Yield (%)b |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | None | 84 |

| 2 | PC2–PC8 as the catalyst instead of fac-Ir(ppy)3 | N.D. |

| 3 | Quinuclidine as the amine | 17 |

| 4 | HBpin as the F−Scavengers | 42 |

| 5 | THF as the solvent instead of DCE | 66 |

| 6 | DMPU as the solvent instead of DCE | 50 |

| 7 | MeOH as the solvent instead of DCE | 48 |

| 8 | 0.2 mL H2O as an additive | 30 |

| 9 | Without fac-Ir(ppy)3 | N.R. |

| 10 | Without light | N.R. |

aStandard conditions: 1a (2.0 eq., 0.2 mmol), 2a (1.0 eq., 0.1 mmol), fac-Ir (ppy)3 (1.0 mol%), TMP (3.0 eq., 0.3 mmol), B2Pin2 (3.0 eq., 0.3 mmol), DCE 1.0 mL, 25 °C, N2, 455 nm, 24 h.

bIsolated yield is based on 2a. N.R. no reaction, N.D. not detected.

Evaluation of substrate scope

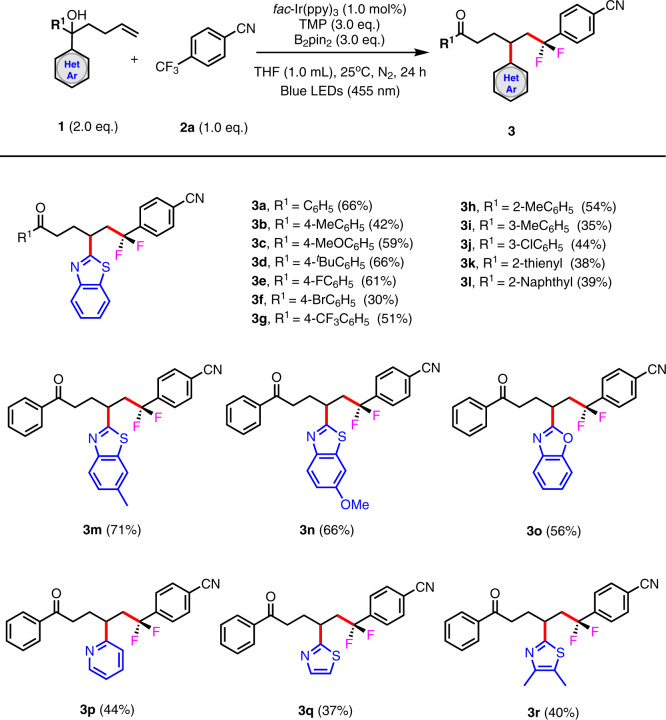

With the optimized reaction conditions in hand, we expanded the scope of this defluoroalkylation–distal functionalization strategy. First, different substituted benzothiazole tertiary alcohols 1 were investigated as substrates to react with 4-trifluoromethylbenzonitrile (2a) (Fig. 2). Notably, the electronic character of the aryl group (R1) did not have a strong effect on the reaction outcome, a range of substituents including electron-neutral (Me, tBu), electron-donating (MeO), and electron-withdrawing (F, Br, and CF3) substituents on the para-positions of the aromatic rings were well tolerated and resulted in the corresponding products with yields ranging from 30 to 66% (3b–3g). Meanwhile, substituents on the ortho- and meta-positions of the aromatic rings were also compatible under the optimized reaction conditions (54% yield for 3h, 35% yield for 3i, and 44% yield for 3j). In addition to phenyl derivatives, other aryl groups such as thienyl (1k) and naphthyl (1l) groups were suitable for this intramolecular heteroaryl migration, although lower yields were obtained (3k and 3l). Subsequently, we turned our attention to the generality of the migrating groups. A variety of N-containing heteroaryl groups were tested for their migratory aptitude (1m–1r). The N-containing heteroaryl groups could also be extended to benzoxazole (1o), pyridine (1p), and thiazole (1q and 1r), although with slightly decreased yields (3o–3r).

Fig. 2. Scope of heteroaryl-substituted tertiary alcohols as substrates.

Reaction conditions: 1 (2.0 eq., 0.2 mmol), 2a (1.0 eq., 0.1 mmol), fac-Ir(ppy)3 (1.0 mol%), TMP (3.0 eq., 0.3 mmol), B2Pin2 (3.0 eq., 0.3 mmol), THF 1.0 mL, 25°C, N2, 455 nm, 24 h. Isolated yield is based on 2a.

To further expand the scope of this transformation, we examined the other reaction partner, electron-deficient Ar–CF3 systems, using benzothiazole-substituted tertiary alcohol 1a as the trapping reagent. As shown in Fig. 3, the para-cyano-substituted benzotrifluorides were good substrates for this reaction, regardless of some electron-withdrawing (F and Cl) substitutions located on the ortho- or meta-positions of the aromatic rings (77% yield for 4a, 82% yield for 4b, and 84% yield for 4c). In contrast to the para-cyano-substituted benzotrifluorides, the ortho- and meta-cyano-substituted benzotrifluorides were not compatible with this migration process, and low chemical efficiency was observed (4e and 4f). The trifluoromethylaromatics bear some other electron-withdrawing groups in addition to the cyano group, including sulfonyl and ester groups. 4-Trifluoromethylbenzenesulfonyl protected acyclic secondary amines, synthetically useful heterocycles (morpholine, glycine derivative), also proved to be appropriate substrates, affording the migrated products in moderate to good yields (4g–4k). Methyl 4-(trifluoromethyl)benzoate (1n) exhibited low reactivity, giving the desired product in less than 15% yield (4n). Pyridine substrates with trifluoromethyl groups at the 2- or 3-positions did not give rise to the corresponding pyridine-migrated products (4o–4q).

Fig. 3. Substrate scope for Ar-CF3 systems.

Reaction conditions: 1a (2.0 eq., 0.2 mmol), 2 (1.0 eq., 0.1 mmol), fac-Ir(ppy)3 (1.0 mol%), TMP (3.0 eq., 0.3 mmol), B2Pin2 (3.0 eq., 0.3 mmol), DCE 1.0 mL, 25 °C, N2, 455 nm, 24 h. Isolated yield is based on 2.

Proposed mechanism

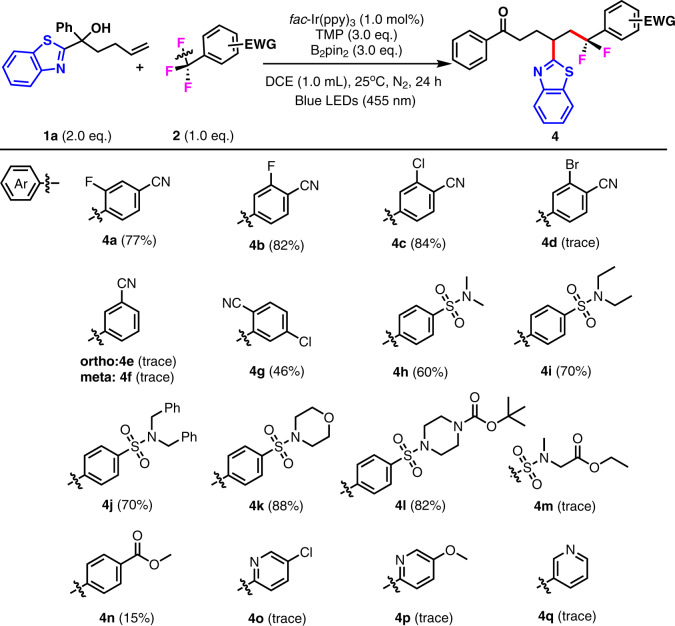

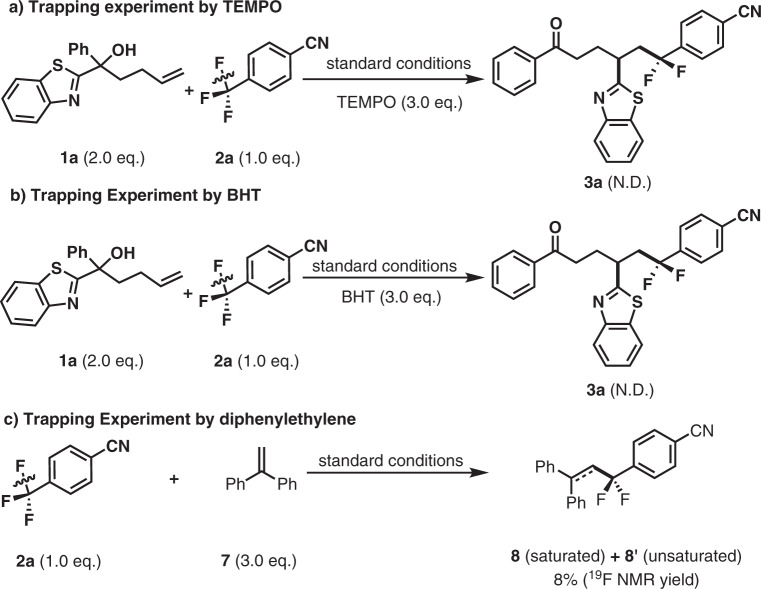

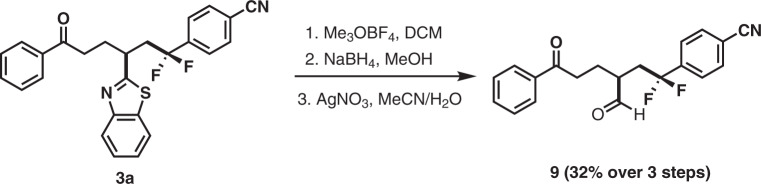

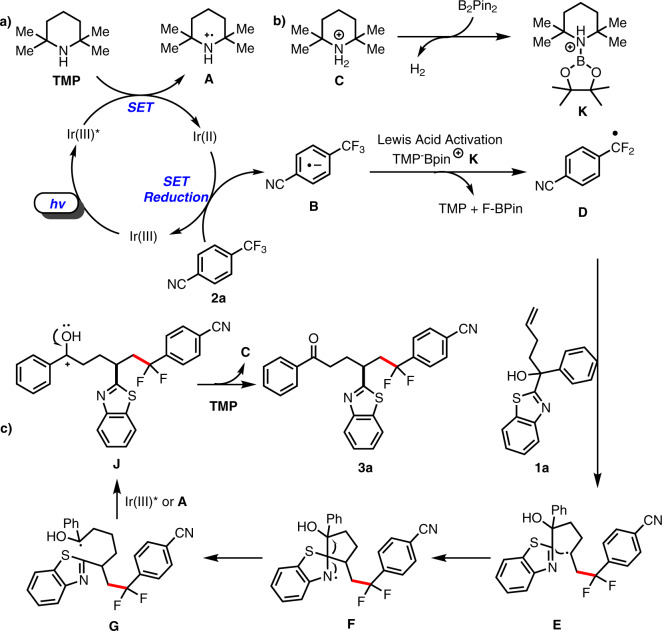

Several control experiments were performed to gain insight into the mechanistic details of this defluoroalkylation–distal functionalization system (Fig. 4). First, the radical trapping agent 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl (TEMPO) or butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) was added under the standard reaction conditions with benzothiazole-substituted alkene 1a and 4-trifluoromethylbenzonitrile (2a) (Fig. 4a, b). As expected, the desired product 3a was obtained only in a trace amount accompanied by the corresponding trapping adducts 5a and 6. This indicates that the aryldifluoromethyl radical is involved in this transformation (for details, see the Supplementary Figs. 3–5). Using diphenylethylene 7 as trapping reagent, the CF2-adduct 8 was detected by HRMS (Fig. 4c). Next, TMP (0.3 mmol) and B2Pin2 (0.3 mmol) were mixed and dissolved in CD2Cl2. A new boron species (11B NMR, δ = 24.26 ppm in CD2Cl2) was observed at a relatively low concentration (for details, see the Supplementary Fig. 8). Based on previous reports21, we assumed that the barium cation K was generated in situ from the reaction of TMP with B2Pin2, which might abstract an F anion from the radical anion B. Based on the Stern–Volmer relationship, we determined that 4-trifluoromethylbenzonitrile quenched excited fac-*Ir(ppy)3 (for details, see the Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12). We also demonstrated the further elaboration of an aryl migrated product (Fig. 5).

Fig. 4. Mechanistic studies.

Standard conditions: fac-Ir(ppy)3 (1.0 mol%), TMP (3.0 eq., 0.3 mmol), B2Pin2 (3.0 eq., 0.3 mmol), THF 1.0 mL, 25 °C, N2, 455 nm, 24 h. a Trapping experiment by TEMPO. b Trapping experiment by BHT. c Trapping experiment by diphenylethylene.

Fig. 5. Further elaboration of 3a.

The corresponding aldehyde 9 can be obtained over 3 steps (32%, the isolated yield is based on 3a).

To understand the effect of the length of the tethered alkyl chain on the ipso-heteroaryl migration, a range of benzothiazole-substituted tertiary alcohols 1 with different chain lengths were applied in the reaction under the standard conditions (Table 2). Among the tested tertiary alcohols, only bishomoallylic alcohol (1a, n = 2) and trishomoallylic alcohol (1t, n = 3) afforded the corresponding heteroaryl-migrated products (3a and 3t, respectively), indicating that this radical-induced heteroaryl migration process might involve cyclic transition states. The migration process prefers the thermodynamically favored five- and six-membered cyclic transition states (n = 2 and 3) over the four- and seven-membered cyclic transition states (n = 1 and 4).

Table 2.

Effect of chain length on reaction efficiencya.

| Compounds | 3r (n = 0) | 3s (n = 1) | 3a (n = 2) | 3t (n = 3) | 3u (n = 4) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TS ring size | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| Yield (%) | 0 | 0 | 84 | 59 | 0 |

aCited yields are for the isolated material following chromatography. Reaction conditions: 1 (2.0 eq., 0.2 mmol), 2a (1.0 eq., 0.1 mmol), fac-Ir(ppy)3 (1.0 mol%), TMP (3.0 eq., 0.3 mmol), B2Pin2 (3.0 eq., 0.3 mmol), DCE 1.0 mL, 25 °C, N2, 455 nm, 24 h.

Based on the above reuslts suggesting the trapping of intermediates and related reports in the literature, we propose the following tentative mechanism for the reaction (Fig. 6). Under visible light, Ir(ppy)3 is excited to Ir(ppy)3* [E1/2 IV/III* = −1.73 V vs. SCE in MeCN]28. Subsequently, a reduced iridium complex (Ir2+) is generated along with the the TMP radical cation A via quenching reduction. The reduced Ir2+ acts as a reductant to reduce 4-trifluoromethylbenzonitrile (2a) to the corresponding aryldifluoromethyl radical D, and Ir3+ is regenerated via SET. At the same time, the Lewis-acidic barium cation K is produced by the reaction between the protonated TMP species C and B2Pin2, which abstracts F− from B to give the aryldifluoromethyl radical D. The benzothiazole-substituted tertiary alcohol 1 captures D to form the alkyl radical intermediate E, which is intercepted by the C=N double bond of the heteroaryl group via a five-membered cyclic transition state to give the spiro-bicyclic N-centered radical intermediate F. The amino radical triggers C–C bond cleavage, and the resultant ring opening of the spiro structure generates the thermodynamically favored ketyl radical G. The single-electron oxidation of G to the cationic intermediate J and the subsequent deprotonation afford the final product 3a.

Fig. 6. Plausible mechanism.

a A proposed photocatalytic cycle. b The production of Lewis-acidic barium cation K. c The C–C bond cleavage and the ring opening of the spiro structure.

In summary, we have demonstrated a novel and efficient method for the selective cleavage of C(sp3)–F and C–C bonds toward the defluoroalkylation of trifluoromethylaromatic substrates with unactivated alkenes via distal heteroaryl migration. The inert C(sp3)–F and C–C bonds are readily cleaved in sequence based on the combination of visible-light photocatalysis and Lewis acid activation. A range of α,α-difluorobenzylic ketones was obtained with complete selectivity in moderate to good yields. The reaction features mild conditions and broad functional-group tolerance. Further studies on radical cascade reactions for the construction of difluoromethylated derivatives and other high-value product classes are currently ongoing in our laboratory.

Methods

General information

For more details, see Supplementary Fig. 1 and the Supplementary Methods.

X-ray crystallography structure of compounds 3a

For the CIF see Supplementary Data 1. For more details, see Supplementary Fig. 2 and Table 1.

Detailed optimization of the reaction conditions

Mechanistic investigation

Fluorescence quenching experiment

Synthesis and characterization

See Supplementary Methods (general information about chemicals and analytical methods, synthetic procedures, product derivation, 1H and 13C NMR data, and HRMS data), Supplementary Figs. 17–105 (1H and 13C NMR spctra).

General procedure for the synthesis of 3a

1-(benzo[d]thiazol-2-yl)-1-phenylpent-4-en-1-ol 1a (0.2 mmol, 59.0 mg, 2.0 eq.), 4-(Trifluoromethyl)benzonitrile 2a (0.1 mmol, 17.1 mg, 1.0 eq.), and fac-Ir(ppy)3 (0.001 mmol, 0.7 mg, 1.0 mol%) were added into a 25 mL snap vial equipped with a stirring bar. The vial was purged with N2 for three times via syringe needle. Then TMP (0.3 mmol, 42.3 mg, 51 μL, 3.0 eq.), dry THF (1.0 mL) and B2pin2 (0.3 mmol, 76.2 mg, 3.0 eq.) were added sequentially by syringes. Then the reaction mixture was irradiated through the bottom side of the vial by Blue LEDs at 25 °C. All the reaction was stopped, the mixture was transferred into a separating funnel and diluted by DCM (30 mL). The organic layer was washed by H2O (10 mL × 2) and brine (10 mL), dried over anhydrous Na2SO4, and then concentrated under reduced pressure. The resulting residue was purified by flashed column chromatography to obtain the desired product.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant nos. 21702103, 21522604, U1463201, and 21402240); the youth in Jiangsu Province Natural Science Fund (Grant nos. BK20150031, BK20130913, and BY2014005-03).

Author contributions

X.Y. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. K.Z. perpared the substrate scope 1f and 1g. Y.C. perpared the substrate scope 1a–1e. L.Q. modified the supporting information. Q.S. and X.D. modified the paper. L.C. and N.Z. checked the format of the paper. G.L. and K.G. provided the money and laboratory platform. J.Q. designed the project and wrote the original draft. All of the authors discussed the results and commented on the paper.

Data availability

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition number CCDC 1867225 (3a). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information (Supplementary Data 1—crystallographic information file for compound 3a). All relevant data are also available from the authors.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jiang-Kai Qiu, Email: qiujiangkai@njtech.edu.cn.

Kai Guo, Email: guok@njtech.edu.cn.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information is available for this paper at 10.1038/s42004-020-00354-5.

References

- 1.Caputo CB, Stephan DW. Activation of alkyl C–F bonds by B(C6F5)3: stoichiometric and catalytic transformations. Organometallics. 2012;31:27–30. doi: 10.1021/om200885c. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O’Hagan D. Understanding organofluorine chemistry. An introduction to the C–F bond. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2008;37:308–319. doi: 10.1039/B711844A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lund H, Jensen NJ. Electroorganic preparations. XXXVI. Stepwise reduction of benzotrifluoride. Acta Chem. Scand. 1974;B 28b:263–265. doi: 10.3891/acta.chem.scand.28b-0263. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yamauchi Y, Fukuhara T, Hara S, Senboku H. Electrochemical carboxylation of α,α-difluorotoluene derivatives and its application to the synthesis of α-fluorinated nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Synlett. 2008;3:438–442. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Munoz SB, et al. Selective late-stage hydrodefluorination of trifluoromethylarenes: a facile access to difluoromethylarenes. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2017;16:2322–2326. doi: 10.1002/ejoc.201700396. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fuchibe K, Ohshima Y, Mitomi K, Alkiyama T. Low-valent niobium-catalyzed reduction of α, α, α-trifluorotoluenes. Org. Lett. 2007;9:1497–1499. doi: 10.1021/ol070249m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Amii H, Hatamoto Y, Seo M, Uneyama K. A new C-F bond-cleavage route for the synthesis of octafluoro[2.2]paracyclophane. J. Org. Chem. 2001;66:7216–7218. doi: 10.1021/jo015720i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stahl T, Klare HFT, Oestreich M. Main-group lewis acids for C–F bond activation. ACS Catal. 2013;3:1578–1587. doi: 10.1021/cs4003244. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forster F, Metsänen TT, Irran E, Hrobárik P, Oestreich M. Cooperative Al–H bond activation in DIBAL-H: catalytic generation of an alumenium-ion-like Lewis acid for hydrodefluorinative Friedel–Crafts alkylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:16334–16342. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b09444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Saito K, Umi T, Yamada T, Suga T, Akiyama T. Niobium(V)-catalyzed defluorinative triallylation of α, α, α-trifluorotoluene derivatives by triple C–F bond activation. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2017;15:1767–1770. doi: 10.1039/C6OB02825J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stahl T, Klare HFT, Oestreich M. C(sp3)–F bond activation of CF3‑substituted anilines with catalytically generated silicon cations: spectroscopic evidence for a hydride-bridged Ru–S dimer in the catalytic cycle. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:1248–1251. doi: 10.1021/ja311398j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshida S, Shimomori K, Kim Y, Hosoya T. Single C-F bond cleavage of trifluoromethylarenes with an ortho-Silyl group. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016;55:10406–10409. doi: 10.1002/anie.201604776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luo C, Bandar JS. Selective defluoroallylation of trifluoromethylarenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:14120–14125. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b07766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen K, Berg N, Gschwind R, König B. Selective single C(sp3)–F bond cleavage in trifluoromethylarenes: merging visible-light catalysis with Lewis acid activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:18444–18447. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b10755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vogt DB, Seath CP, Wang H, Jui NT. Selective C–F functionalization of unactivated trifluoromethylarenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:13203–13211. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b06004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang H, Jui NT. Catalytic defluoroalkylation of trifluoromethylaromatics with unactivated alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:163–166. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b12590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Souillart L, Cramer N. Catalytic C–C bond activations via oxidative addition to transition metals. Chem. Rev. 2015;115:9410–9464. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.5b00138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jia K, Zhang F, Huang H, Chen Y. Visible-light-induced alkoxyl radical generation enables selective C(sp3)–C(sp3) bond cleavage and functionalizations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:1514–1517. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b13066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wu Z, Wang D, Liu Y, Huan L, Zhu C. Chemo- and regioselective distal heteroaryl ipso-migration: a general protocol for heteroarylation of unactivated alkenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017;139:1388–1391. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b11234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu X, et al. Tertiary‐alcohol‐directed functionalization of remote C(sp3)–H bonds by sequential hydrogen atom and heteroaryl migrations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:1640–1644. doi: 10.1002/anie.201709025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang M, Wu Z, Zhang B, Zhu C. Azidoheteroarylation of unactivated olefins through distal heteroaryl migration. Org. Chem. Front. 2018;5:1896–1899. doi: 10.1039/C8QO00301G. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu J, Wu Z, Zhu C. Efficient docking–migration strategy for selective radical difluoromethylation of alkenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018;57:17156–17160. doi: 10.1002/anie.201811346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu X, Wu S, Zhu C. Radical-mediated difunctionalization of unactivated alkenes through distal migration of functional groups. Tetrahedron Lett. 2018;59:1328–1336. doi: 10.1016/j.tetlet.2018.02.053. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu X, Zhu C. Recent advances in radical‐mediated C—C bond fragmentation of non‐strained molecules. Chin. J. Chem. 2019;37:171–182. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sivagueu P, Wang Z, Zanoni G, Bi X. Cleavage of carbon–carbon bonds by radical reactions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019;48:2615–2656. doi: 10.1039/C8CS00386F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yu J, Wang D, Xu Y, Wu Z, Zhu C. Distal functional group migration for visible-light induced carbo-difluoroalkylation/monofluoroalkylation of unactivated alkenes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2018;360:744–750. doi: 10.1002/adsc.201701229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zheng M, et al. Electrochemical sulfonylation/heteroarylation of alkenes via distal heteroaryl ipso-migration. Org. Lett. 2018;20:7784–7789. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b03191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flamigni L, Barbieri A, Sabatini C, Barigelletti F. Photochemistry and photophysics of coordination compounds: iridium. Top. Curr. Chem. 2007;281:143–203. doi: 10.1007/128_2007_131. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition number CCDC 1867225 (3a). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. The data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information (Supplementary Data 1—crystallographic information file for compound 3a). All relevant data are also available from the authors.