Abstract

Organic diradicaloids usually display an open-shell singlet ground state with significant singlet diradical character (y0) which endow them with intriguing physiochemical properties and wide applications. In this study, we present the design of an open-shell nitrogen-centered diradicaloid which can reversibly respond to multiple stimuli and display the tunable diradical character and chemo-physical properties. 1a was successfully synthesized through a simple and high-yielding two-step synthetic strategy. Both experimental and calculated results indicated that 1a displayed an open-shell singlet ground state with small singlet-triplet energy gap (ΔES−T = −2.311 kcal mol−1) and a modest diradical character (y0 = 0.60). Interestingly, 1a was demonstrated to undergo reversible Lewis acid-base reaction to form acid-base adducts, which was proven to effectively tune the ground-state electronic structures of 1a as well as its diradical character and spin density distributions. Based on this, we succeeded in devising a photoresponsive system based on 1a and a commercially available photoacid merocyanine (MEH). We believe that our studies including the molecular design methodology and the stimuli-responsive organic diradicaloid system will open up a new way to develop organic diradicaloids with tunable properties and even intelligent-responsive diradicaloid-based materials.

Subject terms: Photochemistry, Organic molecules in materials science

The electronic structures and open-shell diradical character of organic diradicaloids endow them with potentially useful optical, electronic and magnetic properties. Here, an open-shell nitrogen-centered diradicaloid is reported and shown to readily react with Lewis and Brønsted acids to form acid-base adducts, allowing for tuning of ground-state electronic structure, diradical character and spin density distribution.

Introduction

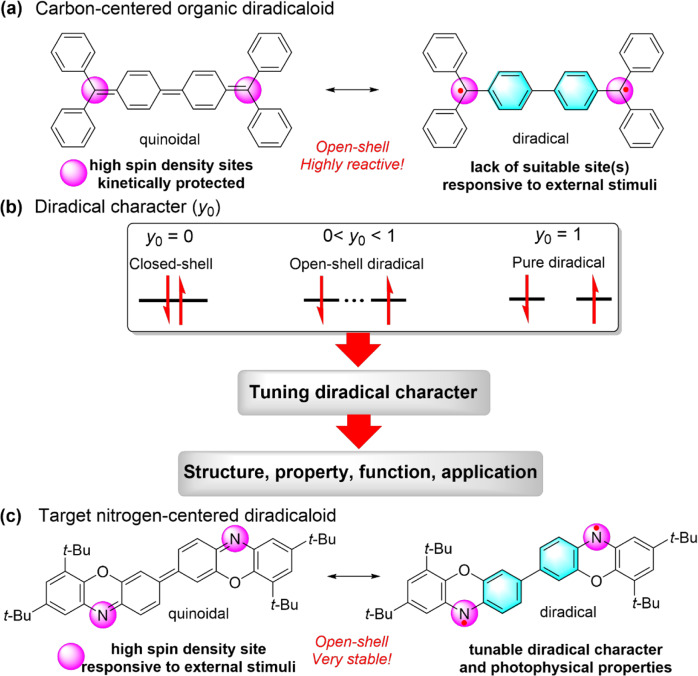

Organic diradicaloids refer to a special kind of molecules with two electrons occupying two quasi-degenerate orbitals, and can be represented by two characteristic resonance structures between closed-shell quinoidal and pure open-shell (diradical) forms1,2. A great number of studies have demonstrated that many organic diradicaloids, such as the most famous Chichibabin’s hydrocarbon (Fig. 1a), display an open-shell singlet ground state with significant singlet diradical character (y0). The unique electronic structures and open-shell diradical character usually endows organic diradicaloids with intriguing properties such as small energy gap with long absorption wavelength3, ambipolar transport characteristics4–6, distinct magnetic behavior7, and special chemical reactivity8,9. Therefore, tuning the diradical character is crucially important because the magnitude of diradical character not only dictates the chemical reactivity, magnetic behavior and photophysical properties of diradicaloids but also determines their functions and applications, especially optoelectronic and spintronic applications (Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1. Design principle of this study.

a Classical carbon-centered organic diradicaloid of Chichibabin’s hydrocarbon and its two characteristic resonance structures. b Diradical character (y0) of organic diradicaloids. c Target nitrogen-centered diradicaloid.

Numerous reports in the literature have successfully demonstrated that many internal factors such as the quinoidal conjugation length10,11, fusion motifs of aromatic rings12–15, planarity of molecules16, incorporation of heteroatoms17–19 and so on could effectively influence or control their ground-state electronic structures and diradical characters20–22. Recently, a few of reports have disclosed that some external stimuli, particularly heat, could exert a significant effect on the diradical characters of organic diradicaloids as well as their magnetic behavior and photophysical properties23–29. For example, Dou and co-workers succeeded in the dynamic modulation of the diradical character based on a family of boron-containing organic diradicaloids by Lewis acid-base coordination23,30–33. However, the examples of tuning the diradical character of organic diradicaloids via external stimuli are still very conservative compared with internal factors. This is largely due to the fact that most organic diradicaloids are π-conjugated polycyclic hydrocarbons containing only carbon and hydrogen atoms, thus lacking the suitable site(s) responsible for external stimuli. In addition, the sites with higher spin density (the most reactive sites) in most organic diradicaloids are normally kinetically protected because of the stability concerns34–38, which also makes the response to external stimuli more difficult. In this scenario, we speculate that varying the chemical environment of sites with high radical density in the organic diradicaloid can more effectively influence its ground-state electronic structures (Fig. 1). In addition, reversibly tuning the diradical character of organic diradicaloids with multiple external stimuli still remains a great challenge and has not yet been realized thus far.

Herein we report the de novo design and synthesis of an open-shell organic diradicaloid molecule 1a, and the general molecular design concept is based on the following considerations (Fig. 1c): (a) target molecule 1a can be conceptually considered as a nitrogen-centered diradicaloid, wherein significant spin density is expected on the two bare aminyl nitrogen atoms in its open-shell resonance form; (b) replacement of the carbon radical center with the electronegative and Lewis basic aminyl radical is essential to improving the stability of 1a as well as the occurrence of the Lewis acid-base reaction39–41; (c) moreover, the tert-butyl groups at both ends of 1a not only improve its solubility but also effectively protect the adjacent reactive positions of carbon bearing some spin densities (vide infra). The systematical studies revealed that 1a displayed an open-shell singlet ground state with small singlet-triplet energy gap (ΔES−T = −2.311 kcal mol−1) and a medium diradical character (y0 = 0.60). Moreover, based on this rational molecular design, 1a was demonstrated to readily undergo the Lewis acid-base reaction with the Lewis acid, Brønsted acid and photoacid to form acid-base adducts, which was accompanied by the significant changes in both photophysical and magnetic properties. Therefore, this work provides a convenient synthesis along with the characterizations of an open-shell organic diradicaloid with tunable and responsive electronic properties and diradical character for the first time to the best of our knowledge.

Results

Molecular synthesis and characterization

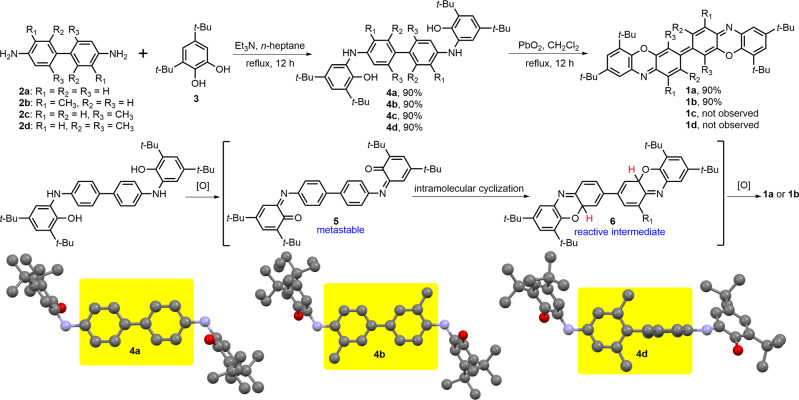

The prevalent strategies for preparing organic diradicaloids usually require multistep synthesis strategies, strict air-free conditions, and tedious purification processes. In contrast, as shown in Fig. 2, diradicaloid 1a can be simply and efficiently synthesized in two steps involving a facile condensation reaction between benzidine 2a and two equivalent amounts of 3,5-di-tert-butyl catechol 3, and a cascade reaction in the presence of lead (IV) oxide, without any purification by column chromatography. The cascade reaction sequence might consist of an oxidation reaction, an intramolecular cyclization42 and a subsequent oxidative aromatization step, accompanied by the generation of unstable quinone imines 5 and a highly reactive dihydro intermediate 6. The scope of the substituted benzidine substrates was surveyed and the preliminary results indicated that the substrate scope of this cascade reaction was restricted to benzidine 2a and 3,3’-dimethylbenzidine 2b, e.g., all attempts to synthesize diradicaloids 1c and 1d were unsuccessful (for details see the Supplementary Information (SI), Synthesis and characterization section). X-ray single-crystal analyses revealed the distinct conformations of the condensation products, namely, 4a and 4b were planar while 4d was highly twisted (Supplementary Data 5, Data 6 and Data 7). Therefore, we speculated that diradicaloids 1c and 1d might be highly reactive because of their twisted structures which was supported by the simulations (Supplementary Fig. 25). As a result, the highly twisted structure led to a higher diradical character of 1d, which was up to 0.977 (Table 7). The resultant diradicaloids 1a and 1b were very stable and thoroughly characterized by 1H NMR, HR-MS measurements and X-ray crystallographic analysis (vide infra). Because 1a and 1b are expected to display similar properties, we focus on the investigation of 1a to avoid redundancy.

Fig. 2. Two-step synthesis protocol for the preparation of the target nitrogen-centered diradicaloid without the need for column chromatography purification.

Synthesis of 1a and 1b and the proposed cascade reaction sequence. The single crystal structures of the condensation products 4a, 4b and 4d are shown.

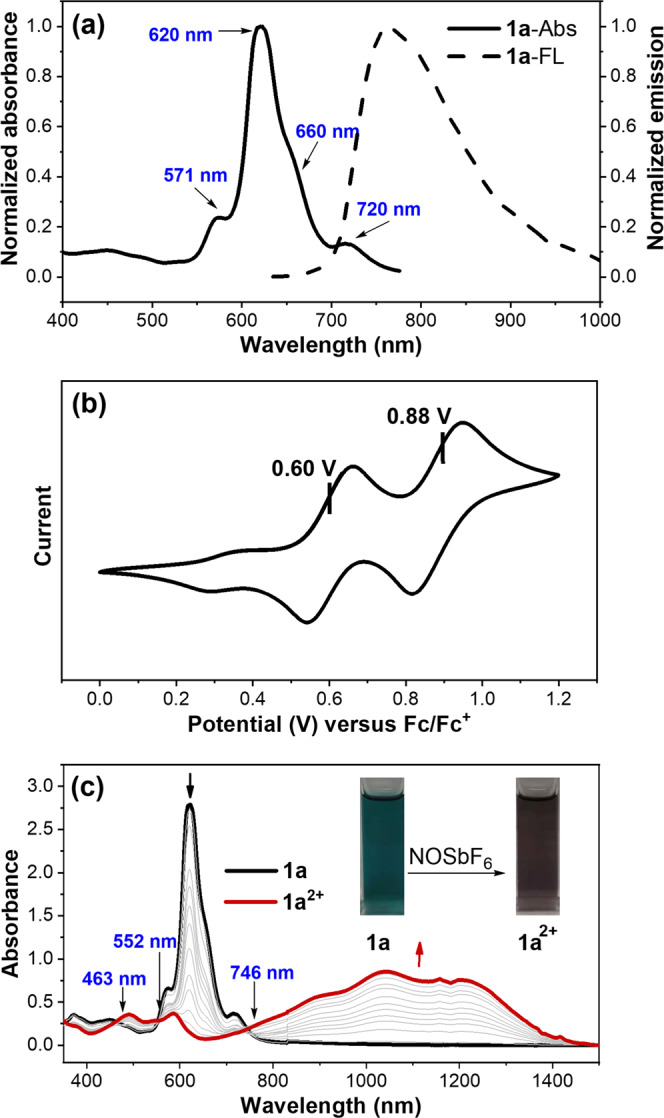

Photophysical and electrochemical properties

The UV-vis-NIR absorption spectrum of 1a featured four main bands from the far-red to near-infrared region with maxima at 571, 620, 660, and 720 nm, resulting in its extensive green color (Fig. 3a). Notably, the weak, longest-wavelength absorption band is the characteristic of the open-shell singlet diradicaloids mainly due to their double-excitation nature (HOMO,HOMO → LUMO,LUMO)43. The absorption profile of 1a was also very similar to some other representative open-shell diradicaloids, such as quinoidal oligothiophenes44–46, zethrenes47–50, teranthene51, bisphenalenyls52–54 and so on55, further indicating its intrinsic open-shell diradical character. When we surveyed its luminescent property, an interesting observation was that 1a unexpectedly exhibited near infrared fluorescence (Fig. 3a), which is obviously different from the nonemissive nature of most open-shell diradicaloids. The near-infrared fluorescence quantum yield of 1a was estimated to be approximately ~4% by the absolute integrating sphere method (Supplementary Fig. 4). Recently, organic radicals, typical monoradicals, have emerged as increasingly important promising luminescent materials for practical applications, while luminescent diradicals are very rare48,56–61. Therefore, to the best of our knowledge, 1a might be the first example of emissive open-shell organic diradicaloid with substantial fluorescence quantum yield.

Fig. 3. Photophysical and electrochemical properties of 1a.

a Normalized absorption and emission spectrum of 1a. b Cyclic voltammogram of 1a in DCM with 0.1 M Bu4NPF6 as the supporting electrolyte, Ag/AgCl as the reference electrode, and a Pt wire as the counter electrode and a scan rate at 20 mV/s. c Absorption titration for the chemical oxidation of 1a using NOSbF6 as oxidant. Inserted are the photos of the solutions.

The electrochemical property of 1a was investigated by performing cyclic voltammetry (CV) in a dry DCM solution (Fig. 3b and Supplementary methods). 1a exhibited two reversible oxidation waves with halfwave potentials (E1/2) of 0.60 and 0.88 V (vs. Fc/Fc+). The HOMO energy level was then estimated to be −5.31 eV based on the onset potential of the first oxidation wave. It is important to note that no reduction wave was observed, which is in contrast to the electrochemical amphoteric redox behavior of most organic diradicaloids. The high-lying HOMO energy level and unobserved reduction wave might be indicative of the highly electron-rich nature of 1a, and thus making it possible to serve as a Lewis base. The two reversible and well-separated oxidation waves of 1a implied that its radical cation 1a•+ and dication 1a2+ species were theoretically stable and accessible. However, the UV-vis-NIR absorption titration for the chemical oxidation of 1a revealed the exclusive generation of dication species 1a2+ as demonstrated by the presence of the isosbestic points (Fig. 3c). Similarly, during the chemical oxidation of 1a and crystal growing process, single crystals of 1a2+ always formed when the oxidation compound precipitated out, even with the addition of less than one equivalent of NOSbF6 (vide infra). Thus, this finding provided accumulating evidence that only the dication species was accessible when 1a underwent chemical oxidation although it displayed two reversible oxidation waves.

X-ray crystallographic analysis

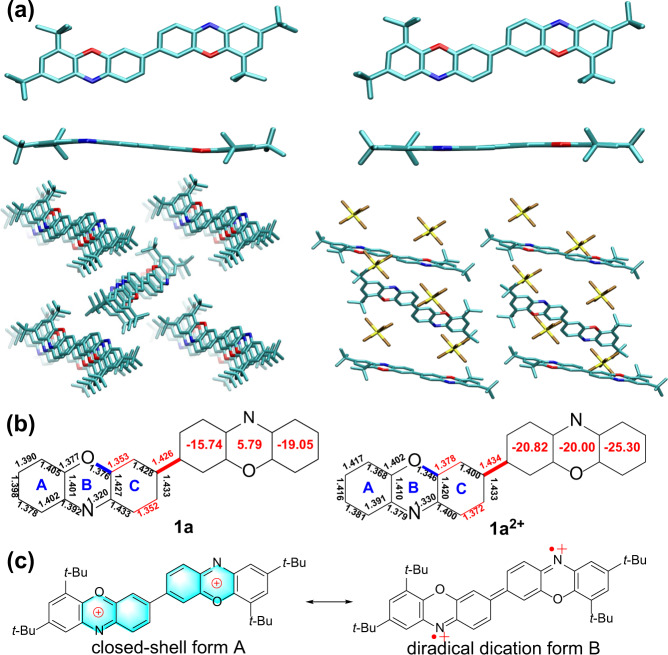

Single crystals of 1a and 1a2+, suitable for X-ray crystallography analysis, were successfully grown and analyzed (Supplementary Data 2, Data 3 and Supplementary methods). We found only the trans isomer of 1a formed, due to its lower energy compared with cis isomer 1a’ (Supplementary Fig. 26)62. The molecular geometry of 1a was slightly bent with dihedral angle nearly 171.6°, mainly due to the lone pairs of electrons on the oxygen and nitrogen atoms. In addition, 1a adopted 1D columnar packing along the a axis with offset face-to-face π–π stacking (~3.7 Å) and the adjacent π-stacks were connected through C − H⋅⋅⋅H − C interactions (~2.50 Å) (Fig. 4a). Therefore, the crystal packing effects might also account for the favorable trans isomer observed in the solid state. Bond length analysis was performed to better analyze the ground-state molecular geometry of 1a (Fig. 4b). A large bond length alternation (BLA) was observed for the central bridged benzene ring (ring C) in 1a (~0.078 Å), which was much larger than that of the Chichibabin’s hydrocarbon (~0.052 Å)63, indicating its dominant quinoidal structure at a low temperature (100 K). However, the bond length for the central C-C bond (highlighted in bold red in Fig. 4b) in 1a was determined to be approximately 1.426 Å, which was longer than that of a double bond (1.34 Å) and slightly shorter than the typical biphenyl single bond (1.48 Å), suggesting the nonnegligible contribution of the diradical resonance form to the ground state. Single crystals of 1b were also successfully obtained, and detailed structural information, such as its planarity and bond length analysis, was quite similar to that of 1a (Supplementary Figs. 8 and 9, Supplementary Data 4, Supplementary Table 1), therefore, the analysis of its crystal will not be covered again here.

Fig. 4. Single crystal structures of 1a and 1a2+.

Single crystal structures including top view, side view and packing modes (a), selected bond lengths (b) of 1a and 1a2+, and resonance structures of 1a2+ (c). The red numbers in the rings denote the calculated NICS(1)ZZ values.

The chemical oxidation of 1a resulted in a highly symmetrical molecule bearing two SbF6- counteranions, clearly confirming the formation of 1a2+. 1a2+ was essentially planar with a dihedral angle of ~180°, indicating an electronic structure that was distinct from that of neutral 1a (Fig. 4a). No intermolecular π–π stacking was observed for 1a2+, probably due to the potential coulomb repulsion between the two positively charged molecules. Regarding the ground-state geometry of 1a2+, it raised the obvious question: what’s the major resonance contributor of 1a between the closed-shell form A and diradical dication form B (Fig. 4c)? Bond length analysis illustrated that 1a2+ showed a smaller BLA (~0.038 Å) than neutral 1a. Moreover, the bond length for the central C-C bond (highlighted in bold red in Fig. 4b) in 1a2+ was measured to be ~1.434 Å, which was longer than that of 1a. More significantly, the C-O (highlighted in bold blue in Fig. 4b) bond length decreased from 1.376 Å in 1a to 1.346 Å in 1a2+, likely suggesting that the latter displayed partial double-bond characteristics. The above bond length analysis results of 1a2+ basically elucidated that the closed-shell form A might dominate its ground-state, which was also consistent with its sharp NMR peaks and unobserved EPR signal (vide infra). Specifically, because the quinoidal benzidine unit intrinsically tended to recover the aromaticity of the two benzenoid rings, 1a was thus prone to the two-electron oxidation process rather than the one-electron oxidation process, thereby leading to the exclusive formation of dication 1a2+64,65.

Magnetic properties

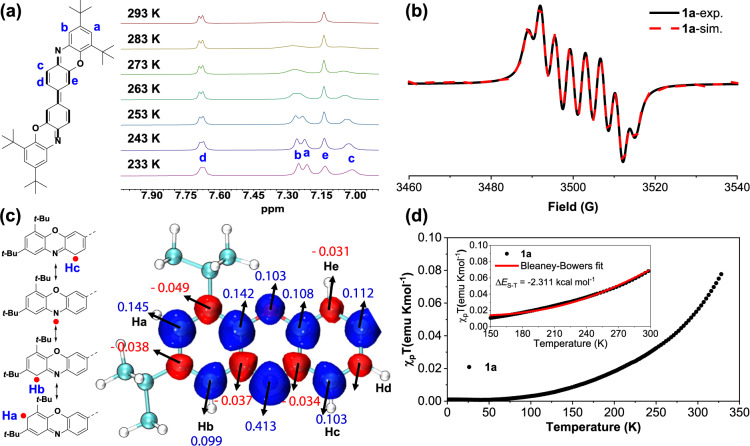

Variable temperature (VT) 1H NMR spectra of 1a were recorded in CD2Cl2 (Fig. 5a and Supplementary methods). The resonances of all the protons were successfully assigned to the structure of 1a based on through-space correlations by 1D and 2D NOESY experiments at 233 K (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary methods). As expected, significant signal broadening was observed for 1a even at room temperature mainly due to the presence of thermally populated triplet species caused by the small singlet-triplet energy gap ∆ES-T, further confirming that 1a displayed an open-shell singlet ground state. The VT NMR spectra of 1a showed a progressive sharpening of some resonances in both aromatic and aliphatic regions when the temperature was gradually lowered to 233 K (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 2). In contrast, the intensity of the aromatic protons of d and e exhibited only a small temperature dependence from 293 to 233 K. We deduced that the spin densities of 1a were mainly delocalized on the N atoms as well as the ortho and para carbon atoms, which could be depicted by its multiple resonance structures (Fig. 5c). According to the spin density calculations (Fig. 5c), in addition to the obvious spin density of the N atom, the alternating spin densities of the outermost two benzene rings and the quinoidal benzidine unit were also observed, thus providing support for our hypothesis. As a result, the protons on or around the carbons with high spin density were subject to a more obvious paramagnetic environment, leading to the more obvious broadening of a, b and c protons than that of d and e.

Fig. 5. Magnetic properties of 1a.

a VT 1H NMR spectra (aromatic region) of 1a in CD2Cl2 and assignment of all aromatic protons. b EPR spectrum of 1a in CH2Cl2 solution measured at room temperature and its simulation. c The typical resonance forms of 1a and its calculated spin density distributions. For clarity, only one-half of 1a is shown. d χT–T plot for the powder of 1a in SQUID measurement. The inset shows the best fitting plots (red solid line) obtained with the Bleaney-Bowers equation. χp = χmol-χd, χd: diamagnetic susceptibility (χd of 1a: ~ −425 × 10−6 emu mol−1).

The EPR study of 1a provided more direct evidence of the presence of radical species both in the solution and solid state (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 5). The solution of 1a displayed a weak EPR signal mainly due to the relatively low spin concentration of its dilute solution. Nevertheless, its solution-state EPR spectrum exhibited a well-resolved octet hyperfine structure, mainly stemming from the hyperfine interactions of the N and multiple H nuclei based on the simulations. Specifically, the simulated spectrum satisfactorily agreed with the experimentally observed spectrum, yielding simulated hyperfine coupling constants (hfccs) of 7.408 G (AN), and 3.777 G, 2.853 G and 2.688 G, corresponding to three proton hyperfine couplings, and a g-value of 2.0024, which was consistent with the aforementioned calculated spin density maps and VT NMR results. 1a also displayed three broad EPR lines in the solid state with enhanced intensity compared with that in solution because of the increased spin concentration (Supplementary Fig. 5). The forbidden half-field transition of 1a was not observed, mainly because the concentration of the thermally populated triplet species was relatively low, and this was the common phenomenon in many diradicaloids with small to moderate diradical character47–50,66–73. In contrast to 1a, 1a2+ was EPR silent and showed well-resolved sharp peaks in the 1H NMR spectrum at room temperature (Supplementary Figs. 6 and 7), which was consistent with its inferred closed-shell form A (Fig. 4c). Nucleus independent chemical shift (NICS) calculations were then conducted to clarify the difference between neutral 1a and dication 1a2+ regarding their aromaticity (Fig. 4b). The obviously negative NICS value of ring C and small positive value of ring B in 1a suggested the significant aromaticity of the central bridged benzene ring but very weak antiaromaticity of the phenoxazine ring, further supporting its nonnegligible contribution of the diradical resonance form to the ground state (Fig. 4b). Compared to 1a, the NICS values for central phenoxazine ring B and ring C in 1a2+ became more negative, indicating that the oxidation process could increase the aromaticity of dication 1a2+, consistent with its highly planar structure and the proposed closed-shell form A based on X-ray crystallographic analysis.

The magnetic property of 1a was further investigated by the superconducting quantum interference device (SQUID) magnetometer (Fig. 5d and Supplementary methods). SQUID measurement of the solid of 1a showed a very small χpT value of approximately 0.07 emu Kmol-1 at 300 K. This is very common among most reported open-shell diradicaloids with moderate diradical character, in which a small quantity of thermally excited triplet species account for their paramagnetic property. 1a exhibited very weak antiferromagnetic behavior, and a magnetic susceptibility enhancement was observed with increasing temperature. The singlet-triplet energy gap (∆ES-T or 2 J/kB) of 1a was then determined to be approximately ~−2.311 kcal mol−1 by fitting the susceptibility data using the Bleaney-Bowers equation (Supplementary methods)74. Thus, 1a was arguably an open-shell diradicaloid, and a thermally excited triplet state was accessible at room temperature due to its relatively small ∆ES-T. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations at the CAM-B3LYP-D3(BJ)/def2-TZVP level were further conducted to elucidate the ground-state electronic structure of 1a (Supplementary Fig. 28 and Supplementary Table 6). The electronic structure was analyzed using Multiwfn75. The results showed that 1a favored an open-shell singlet ground state with a medium singlet diradical character (y0 = 0.55). The open-shell singlet diradical state was estimated to be 2.10 and 10.22 kcal mol-1 lower than the triplet diradical and closed-shell states, respectively. Thus, the calculation results were in good agreement with the featured open-shell electronic absorption, X-ray crystallographic analysis and magnetic measurements of 1a, all of which proved that it had an open-shell singlet ground state.

Acid-base stimuli-responsive properties

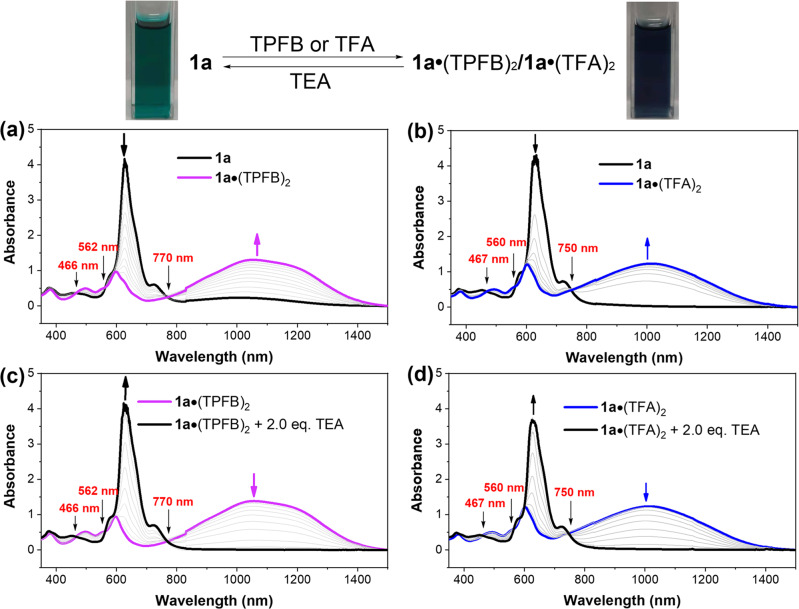

As mentioned above, 1a, consisting of electron-rich nitrogen centers, is anticipated to act as a Lewis base and undergo reversible acid-base reactions (Fig. 6a). UV-vis-NIR absorption spectrophotometric titrations between 1a and Lewis acid tris(pentafluorophenyl)borane (TPFB) or Brønsted acid trifluoroacetic acid (TFA) proved the intrinsic Lewis basicity of 1a, thereby permitting the Lewis acid-base adduct approach to tuning its diradical character. Upon the addition of TPFB to 1a, an obvious decrease in the intensity of its maximum absorption between 600 and 700 nm was observed, accompanied by the emergence of a weak absorption band at 600 nm and a new broad long-wavelength absorption in the range of 700–1400 nm (Fig. 6b). In addition, saturation of the absorbance at a nearly 2:1 molar ratio of TPFB to 1a was observed. This was concomitant with a set of isosbestic points at 463, 560, 770 nm, suggesting the formation of the Lewis acid-base adduct of 1a•(TPFB)2. A similar spectral change was observed when titrating 1a with TFA, yielding the acid-base adduct 1a•(TFA)2, which resembled 1a•(TPFB)2 in the absorption profile (Fig. 6b). Thus, both Lewis acid and Brønsted acid produced similar effects on the photophysical properties of 1a after the formation of acid-base adducts. Similar to the oxidation process, the intermediate of the 1:1 acid-base adduct was not observed, which might be desirable to recover more aromaticity. Titration of a 1a with a weaker acid (glacial acetic acid (AA)) also indicated that no mono-protonated species formed during this acid-base reaction (Supplementary Fig. 20). Interestingly, the acid-base adducts could almost completely be restored to 1a after the addition of two equivalents of a stronger Lewis base triethylamine (TEA), indicating that this Lewis acid-base adduct approach was highly reversible (Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 20).

Fig. 6. UV–vis–NIR absorption changes of 1a in the reversible Lewis acid-base reaction.

a Schematic illustration of the reversible Lewis acid-base reaction between 1a and corresponding acids. b Absorption spectral changes during the titration of 1a with TPFB (left) and TFA (right). c Absorption spectral changes during the titration of 1a•(TPFB)2 (left) and 1a•(TFA)2 (right) with TEA.

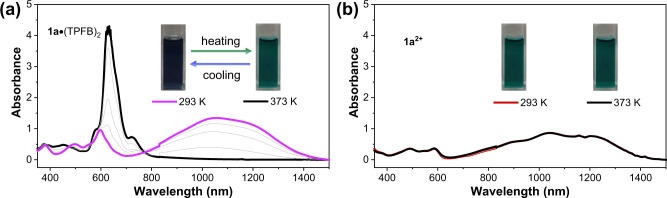

One may argue that the dication species 1a2+ and the acid-base adducts more or less resembled each other in their UV-vis-NIR absorption profiles. However, by comparing and contrasting the UV data, the detailed absorption characteristics, especially the fine structures in the UV-vis-NIR absorption spectra, between 1a2+ and both acid-base adducts were different (Supplementary Fig. 14, highlight in shaded region). In addition, their solution also displayed distinct color that 1a2+ was dark brown while the acid-base adducts were dark blue. Therefore, their distinct UV data clearly implied that 1a2+ and the acid-base adducts exhibited completely different electronic structures. Moreover, variable temperature (293 K to 373 K) UV-vis-NIR absorption of 1a•(TPFB)2 and 1a2+ indicated that the former could undergo reversible dissociation while the latter exhibited no response to temperature (Fig. 7)32,76. Specifically, the acid-base adduct 1a•(TPFB)2 dissociated into free 1a progressively with increasing temperature, accompanied by an obvious color change from original dark blue at room temperature to blue color at a higher temperature. This intrinsic temperature-dependent photophysical behavior of 1a•(TPFB)2 suggested that the reaction between 1a and TPFB was simple Lewis acid-base reaction while the oxidation reaction was not involved77.

Fig. 7. Variable temperature UV-vis-NIR absorption of acid-base adducts and dications.

Variable temperature absorption of (a) 1a•(TPFB)2 and (b) 1a2+ in C2H2Cl4 (14 μM).

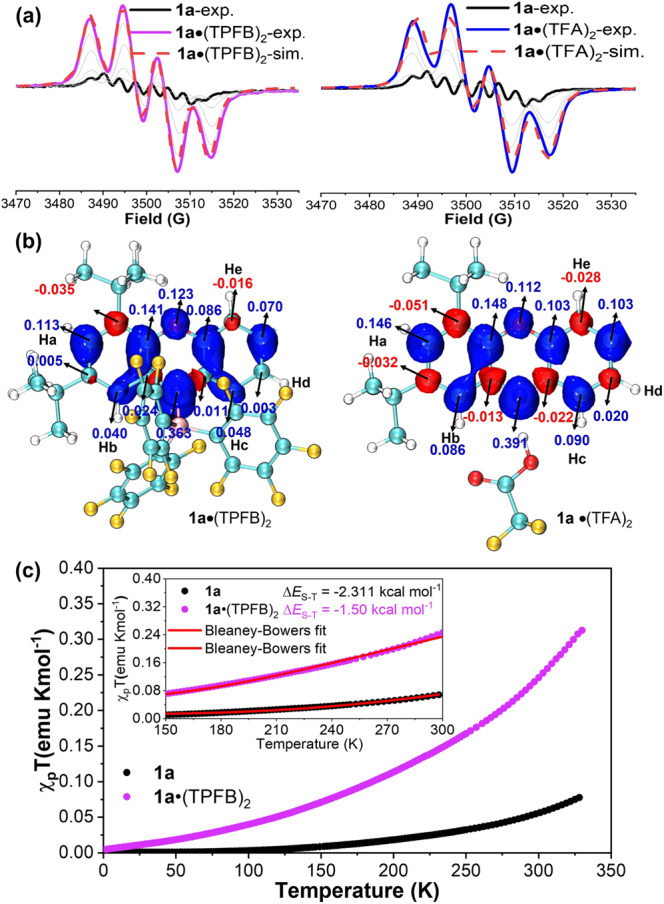

The magnetic properties of 1a also changed significantly upon the addition of acids. The EPR signal intensity of pristine 1a progressively increased with increasing acid concentration and then reached a saturation point when nearly two equivalent amounts of TFA or TPFB were added (Fig. 8a). The EPR spectral changes for both titrants were very similar, and the resultant acid-base adducts 1a•(TPFB)2 and 1a•(TFA)2 resembled each other in their EPR patterns. Thus, the EPR titration results also supported the formation of acid-base adducts in a 2:1 molar ratio, which was consistent with the absorption titration data. In addition, another notable change in the EPR titration spectra was the distinct hyperfine splitting patterns between 1a and the acid-base adducts. Theoretical calculations demystified that the characteristic quartet hyperfine splitting patterns of the acid-base adducts originated from the distinct spin density distributions after 1a coordinated with acid, i.e., the spin densities on the carbons linked to Hb and Hc diminished significantly (Fig. 8b). Therefore, the EPR spectra could be roughly simulated based on their calculated spin density distributions (Fig. 8a, b), wherein the four-line splitting of both 1a•(TFA)2 and 1a•(TPFB)2 occurred mainly due to the isotropic 14N hyperfine coupling and proton (Ha, Hb and Hc) superhyperfine splitting. Moreover, the EPR profile could spring back to its original shape and intensity after the addition of two equivalents of TEA, indicating that 1a•(TFA)2 and 1a•(TPFB)2 can be fully converted back to 1a (Supplementary Fig. 16), agreeing well with the observed absorption titration results. Therefore, the delocalization of spin density of 1a could also be reversibly regulated by the reversible acid-base reaction, during which both 1a and its acid-base adducts remained inherent stability.

Fig. 8. Magnetic property changes of 1a in the reversible Lewis acid-base reaction.

a EPR spectral changes during the titration of 1a with TPFB (left) and TFA (right), and EPR simulation of 1a•(TPFB)2 and 1a•(TFA)2. b Calculated spin density distributions of 1a•(TPFB)2 (left) and 1a•(TFA)2 (right). For clarity, only one-half of molecule is shown. c Comparison of χT–T plot for 1a and 1a•(TPFB)2. The inset shows the best fitting plots (red solid line) and singlet-triplet energy gap obtained with the Bleaney-Bowers equation. χp = χmol-χd, χd: diamagnetic susceptibility (χd of 1a: ~ −425 × 10−6 emu mol-1, χd of 1a•(TPFB)2: ~ −846 × 10-6 emu mol-1).

The observed enhanced EPR signal intensity was a clue that the diradical character of 1a might undergo significant changes before and after acid stimulation. Interestingly, the NMR line broadening effect of 1a became more pronounced when acid was added, indicating an increased amount of paramagnetic species after acid stimulation (Supplementary Figs. 17 and 18). Specifically, taking 1a•(TPFB)2 as an example, the VT NMR spectroscopy experiments indicated that 1a•(TPFB)2 displayed broad signals even at a low temperature (Supplementary Fig. 17), in contrast to the relatively sharp peaks of 1a. To understand in more detail the differences in the change in magnetic properties, SQUID measurement of a powdered sample of 1a•(TPFB)2 at a temperature gradient ranging from 2 to 330 K was obtained and compared with that of 1a (Fig. 8c and Supplementary Table 5). As expected, the magnetic susceptibility (χpT) of 1a•(TPFB)2 increased to 0.25 emu Kmol−1 at 300 K, which was significantly larger than that of 1a. This larger magnetic susceptibility might account for the enhanced EPR signal intensity and more obvious NMR line broadening of 1a•(TPFB)2. The singlet-triplet energy gap (∆ES-T) of 1a•(TPFB)2 was then estimated to be −1.50 kcal mol−1 by fitting the data using the Bleaney-Bowers equation, which was smaller than that of 1a. In addition, DFT calculations predicted that the acid-base adducts of 1a•(TFA)2 and 1a•(TPFB)2 both showed an open-shell singlet diradical ground state with ∆ES-T values of −1.98 and −0.78 kcal mol−1, respectively, which were smaller than that of 1a (Supplementary Table 6, Supplementary Data 1). The diradical character of 1a•(TFA)2 and 1a•(TPFB)2 were calculated to be 0.64 and 0.78, respectively, which was larger than that of 1a (Supplementary Table 7, Supplementary Data 1). Therefore, the different values of ∆ES-T and y0 perfectly illustrated the fact that the population of thermally excited triplet species was even more favorable after 1a formed acid-base adducts in the presence of acid stimulation, thus directly affecting their magnetic properties.

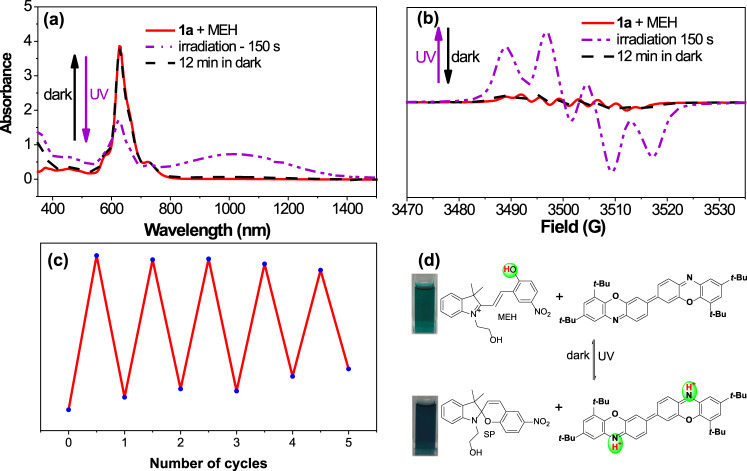

Light-controlled reversible modulation of UV-vis-NIR absorption and diradical character

The success of the Lewis acid-base adduct approach in enhancing the diradical character of 1a further inspired us to investigate its photoresponsive properties by using a photoacid as an acid stimulus. Photoacids are often referred to as molecules that can release proton(s) upon light irradiation; they can regain a proton(s) in the dark or by heating, making this process reversible78,79. Therefore, the light-controlled reversible acid-base reaction between 1a and a suitable photoacid via intermolecular proton transfer is theoretically feasible, although 1a itself is non-photoresponsive80,81. A commercially available photoacid merocyanine (MEH) was selected for use in this study. When the mixed solution of 1a and MEH (mole ratio 1a: MEH = 1: 5) was illuminated with ultraviolet light at a wavelength of 365 nm, a continuous change in the UV-vis-NIR spectra was observed, and the trend together with the absorption characteristics resembled the experimental acid-titration results (Fig. 9a). After 150 s of irradiation, the new broad long-wavelength absorption from 700–1400 nm reached a maximum, and the color of the solution changed from green to dark blue. Interestingly, the absorption profile and the color returned to their original form when the irradiated mixture was kept in the dark for 12 min (Fig. 9a). Moreover, this photoswitching process displayed good stability over five cycles (Fig. 9c). Similarly, EPR spectroscopy was applied to monitor the photoswitching process in situ, and the distinct octet and quartet hyperfine splitting patterns could be reversibly switched many times without decomposition by alternating between UV irradiation and dark storage (Fig. 9b and Supplementary Fig. 21). The changes in intensity along with the corresponding changes in the hyperfine splitting pattern in the EPR spectra were all consistent with the titration experiment. The proposed working principle of the operation of this responsive system was that the photoacid MEH could transfer to a highly metastable form SP under irradiation and at the same time released a proton that then protonated the nitrogen atom of 1a; in the dark, the metastable form SP could recapture the proton, regenerating both the photoacid MEH and 1a (Fig. 9d). Therefore, the UV-vis-NIR absorption and diradical character of 1a could be well manipulated during this photoswitching process. To the best of our knowledge, this work is the first to realize the light-controlled reversible modulation of the photophysical and magnetic properties of an organic diradicaloid.

Fig. 9. Light-controlled reversible modulation of UV-vis-NIR absorption and diradical character.

UV-vis-NIR absorption (a) and EPR spectra (b) of a solution of 1a and MEH (mole ratio 1a: MEH = 1: 5) before irradiation (red line), after irradiation for 150 s (purple dotted line), and kept in the dark for 12 min after irradiation (black dotted line). c The reversible changes of the absorbance under cycles of irradiation and darkness. d Schematic illustration of the light-controlled reversible protonation and deprotonation process of 1a through the use of a photoacid (MEH).

Discussion

In summary, an open-shell nitrogen-centered diradicaloid 1a was successfully synthesized through a simple and high-yielding two-step synthesis protocol without the need for column chromatography. The ground-state electronic structure of 1a was systematically investigated by X-ray crystallographic analysis, VT NMR, EPR, and SQUID techniques along with DFT calculations, and all the data collectively suggested that 1a displayed an open-shell singlet ground state with a small singlet-triplet energy gap and a modest diradical character. Interestingly, the photophysical and magnetic properties of 1a changed dramatically in the presence of acidic stimulus, accompanied by a decrease in the singlet-triplet energy gap and an increase in diradical character. Detailed theoretical and experimental studies disclosed that the fundamental cause of the change in these properties was that the formation of the Lewis acid-base adduct prominently impacted the ground-state electronic structures of 1a as well as its diradical character and spin density distributions. Therefore, this work for the first time demonstrates a rare and interesting stimuli-responsive organic diradical system to the best of our knowledge that is capable of reversibly altering its photophysical properties and diradical character upon exposure to external stimuli. It is expected that our studies would not only provide a simple synthetic strategy to design open-shell diradicaloid but also shed some light on the development of the advanced organic diradicaloids and related materials with tunable stimuli-responsive electronic properties and diradical character.

Methods

All reagents and starting materials were obtained from commercial suppliers and used without further purification. All air-sensitive reactions were carried out under inert N2 atmosphere. The 1H NMR, 11B NMR, 13C NMR and 1D NOESY spectra were recorded in solution of CD2Cl2 and DMSO-d6 on Bruker 400 MHz, 500 MHz spectrometer. 2D NMR (NOESY) and variable temperature NMR were measured in solution of CD2Cl2 on Agilent DD2 600 MHz. UV-vis-NIR spectra were recorded in a quartz cell (light path 10 mm) on a Shimadzu UV2700 UV-visible spectrophotometer. Fluorescence spectra and photoluminescence quantum yields (Ф) were recorded on HORIBA Duetta. Cyclic voltammetry was recorded on a Bio-Logic SAS SP-150 spectrometer in anhydrous DCM containing n-Bu4NPF6 (0.1 M) as supporting electrolyte at a scan rate of 20 mV/s at room temperature. The CV cell has a glassy carbon electrode, a Pt wire counter electrode, and an Ag/Ag+ reference electrode. The potential was externally calibrated against the ferrocene/ferrocenium (Fc/Fc+) couple. The highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied molecular orbital (LUMO) energy levels were calculated based on the equations: EHOMO/LUMO = −(4.80 + Eonsetox/Eonsetred) eV. EPR spectra for radicals were obtained on Bruker EMX instrument EMXPLUS-10/12. EPR spectra simulation was conducted on the Bruker SpinFit software. For SQUID measurement, magnetic susceptibility of powder sample (30 mg) was measured in a polycarbonate capsule fitted in a plastic straw as a function of temperature in heating (2 K → 330 K) mode with 30 s of temperature stability at each temperature (1 K increment in a range 2–10 K, 2 K increment in a range 10–20 K, 5 K increment in a range 20–100 K, 10 K increment in a range 100–330 K,) at 1.0 T using a SQUID magnetometer (Quantum MPMS3). The data was corrected for both sample diamagnetism (Pascal’s constants) and the diamagnetism of the sample holder (polycarbonate capsule). The single crystals of this work were measured on Bruker Apex duo equipment with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54184 Å). The HR-ESI mass spectra were performed on Q Exactive Focus (Thermo Scientific, USA). The singlet-triplet energy gap (∆ES-T or 2 J/kB) was determined by fitting the susceptibility data using the Bleaney-Bowers equation,

where −2J is correlated to the excitation energy from the ground state to the first excited state, ρ is the content of paramagnetic impurities, T is the temperature, kB is Boltzmann constant, N is Avogadro constant.

Supplementary information

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Acknowledgements

X. S. acknowledges the financial support sponsored by the NSFC, China (No. 52003081), Shanghai Natural Science Foundation (22ZR1420600) and the Microscale Magnetic Resonance Platform of ECNU. This work was also supported by the Research Funds of Happiness Flower ECNU (2020JK2103).

Author contributions

X.S. and B.H. conceived the project, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript. B.H. and C.-W. Z. performed the most of experiments. H.K. carried out DFT calculation. X.-L.Z. conducted single crystal analyses. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Peer review

Peer review information

Communications Chemistry thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors on reasonable request, see author contributions for specific data sets. Experimental details, additional characterizations, computational details, and figures including synthetic route, UV−vis-NIR spectra, 1H and 13C NMR spectra, 1D and 2D NOESY NMR spectra, MS spectra, EPR spectra, spin density and spin population (PDF) are described in the Supplementary Information. Cartesian coordinates are deposited in Supplementary Data 1 file. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers CCDC 2132537 (4a), 2132539 (4b), 2132540 (4d), 2104545 (1a), 2104547 (1b), and 2132542 (1a2+). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. The CIF files of CCDC 2132537 (4a), 2132539 (4b), 2132540 (4d), 2104545 (1a), 2104547 (1b), and 2132542 (1a2+) are also included as Supplementary Data 2-Data 7.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s42004-022-00747-8.

References

- 1.Abe M. Diradicals. Chem. Rev. 2013;113:7011–7088. doi: 10.1021/cr400056a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Stuyver T, et al. Do Diradicals Behave Like Radicals? Chem. Rev. 2019;119:11291–11351. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zeng W, et al. Rylene Ribbons with Unusual Diradical Character. Chem. 2017;2:81–92. doi: 10.1016/j.chempr.2016.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jousselin-Oba T, et al. Modulating the ground state, stability and charge transport in OFETs of biradicaloid hexahydrodiindenopyrene derivatives and a proposed method to estimate the biradical character. Chem. Sci. 2020;11:12194–12205. doi: 10.1039/D0SC04583G. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang Y, Egap E. Open-shell organic semiconductors: an emerging class of materials with novel properties. Polym. J. 2018;50:603–614. doi: 10.1038/s41428-018-0070-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dong S, Li Z. Recent progress in open-shell organic conjugated materials and their aggregated states. J. Mater. Chem. C. 2022;10:2431–2449. doi: 10.1039/D1TC04598A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar S, Kumar Y, Keshri SK, Mukhopadhyay P. Recent Advances in Organic Radicals and Their Magnetism. Magnetochemistry. 2016;2:42. doi: 10.3390/magnetochemistry2040042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fu X, Zhao D. Cyclo-oligomerization of 6,12-Diethynyl Indeno[1,2-b]fluorenes via Diradical Intermediates. Org. Lett. 2015;17:5694–5697. doi: 10.1021/acs.orglett.5b03000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang X, Zhang D, Liao Y, Zhao D. Toward an Air-Stable Triradical with Strong Spin Coupling: Synthesis of Substituted Truxene-5,10,15-triyl. J. Org. Chem. 2020;85:5761–5770. doi: 10.1021/acs.joc.9b03077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu X, et al. Air- and Heat-Stable Planar Tri-p-quinodimethane with Distinct Biradical Characteristics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:16342–16345. doi: 10.1021/ja206060n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi X, et al. Antiaromatic bisindeno-[n]thienoacenes with small singlet biradical characters: syntheses, structures and chain length dependent physical properties. Chem. Sci. 2014;5:4490–4503. doi: 10.1039/C4SC01769B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi X, et al. Benzo-thia-fused [n]thienoacenequinodimethanes with small to moderate diradical characters: the role of pro-aromaticity versus anti-aromaticity. Chem. Sci. 2016;7:3036–3046. doi: 10.1039/C5SC04706D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hu P, et al. Toward Tetraradicaloid: The Effect of Fusion Mode on Radical Character and Chemical Reactivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:1065–1077. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b12532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barker JE, et al. Molecule Isomerism Modulates the Diradical Properties of Stable Singlet Diradicaloids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:1548–1555. doi: 10.1021/jacs.9b11898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hayashi H, et al. Monoradicals and Diradicals of Dibenzofluoreno[3,2-b]fluorene Isomers: Mechanisms of Electronic Delocalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:20444–20455. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c09588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zeng Z, et al. Stable Tetrabenzo-Chichibabin’s Hydrocarbons: Tunable Ground State and Unusual Transition between Their Closed-Shell and Open-Shell Resonance Forms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:14513–14525. doi: 10.1021/ja3050579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dressler JJ, et al. Thiophene and its sulfur inhibit indenoindenodibenzothiophene diradicals from low-energy lying thermal triplets. Nat. Chem. 2018;10:1134–1140. doi: 10.1038/s41557-018-0133-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang Z-Y, et al. A Stable Triplet-Ground-State Conjugated Diradical Based on a Diindenopyrazine Skeleton. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:4594–4598. doi: 10.1002/anie.202012989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong S, et al. Extended Bis(anthraoxa)quinodimethanes with Nine and Ten Consecutively Fused Six-Membered Rings: Neutral Diradicaloids and Charged Diradical Dianions/Dications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:62–66. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b10279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hsieh Y-C, et al. Zethrene and Dibenzozethrene: Masked Biradical Molecules? Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015;54:3069–3073. doi: 10.1002/anie.201410316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang C, et al. Stable Cross-Conjugated Tetrathiophene Diradical. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:11291–11295. doi: 10.1002/anie.201904153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dressler JJ, Haley MM. Learning how to fine-tune diradical properties by structure refinement. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2020;33:e4114. doi: 10.1002/poc.4114. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo J, Yang Y, Dou C, Wang Y. Boron-Containing Organic Diradicaloids: Dynamically Modulating Singlet Diradical Character by Lewis Acid-Base Coordination. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:18272–18279. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c08486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tian X, et al. Tuning Diradical Properties of Boron-Containing π-Systems by Structural Isomerism. Chem. Eur. J. 2022;28:e202200045. doi: 10.1002/chem.202200045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wei H, et al. A Stable N-Annulated Perylene-Bridged Bisphenoxyl Diradicaloid and the Corresponding Boron Trifluoride Complex. Chem. Eur. J. 2017;23:9419–9424. doi: 10.1002/chem.201701692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mutoh K, Toshimitsu S, Kobayashi Y, Abe J. Dynamic Spin-Spin Interaction Observed as Interconversion of Chemical Bonds in Stepwise Two-Photon Induced Photochromic Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021;143:13917–13928. doi: 10.1021/jacs.1c06775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y, et al. Temperature Tunable Self-Doping in Stable Diradicaloid Thin-Film Devices. Adv. Mater. 2015;27:7412–7419. doi: 10.1002/adma.201502404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo J, et al. Stable Quadruple Helical Tetraradicaloid with Thermally Induced Intramolecular Magnetic Switching. CCS Chem. 2022;4:95–103. doi: 10.31635/ccschem.021.202000658. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shen Y, et al. Normal & reversed spin mobility in a diradical by electron-vibration coupling. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:6262. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26368-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Osumi S, et al. Boron-doped nanographene: Lewis acidity, redox properties, and battery electrode performance. Chem. Sci. 2016;7:219–227. doi: 10.1039/C5SC02246K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kushida T, Yamaguchi S. Boracyclophanes: Modulation of the σ/π Character in Boron-Benzene Interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:8054–8058. doi: 10.1002/anie.201303830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Saito S, Matsuo K, Yamaguchi S. Polycyclic π-Electron System with Boron at Its Center. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:9130–9133. doi: 10.1021/ja3036042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yamaguchi S, Akiyama S, Tamao K. Colorimetric Fluoride Ion Sensing by Boron-Containing π-Electron Systems. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:11372–11375. doi: 10.1021/ja015957w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kubo T. Phenalenyl-based open-shell polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Chem. Rec. 2015;15:218–232. doi: 10.1002/tcr.201402065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun Z, Zeng Z, Wu J. Zethrenes, Extended p-Quinodimethanes, and Periacenes with a Singlet Biradical Ground State. Acc. Chem. Res. 2014;47:2582–2591. doi: 10.1021/ar5001692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kubo T. Recent Progress in Quinoidal Singlet Biradical Molecules. Chem. Lett. 2015;44:111–122. doi: 10.1246/cl.140997. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Fix AG, Chase DT, Haley MM. Indenofluorenes and Derivatives: Syntheses and Emerging Materials Applications. Top. Curr. Chem. 2012;349:159–195. doi: 10.1007/128_2012_376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kato K, Osuka A. Platforms for Stable Carbon-Centered Radicals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2019;58:8978–8986. doi: 10.1002/anie.201900307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zeng W, et al. Stable Nitrogen-Centered Bis(imino)rylene Diradicaloids. Chem. Eur. J. 2018;24:4944–4951. doi: 10.1002/chem.201706041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shimizu D, Furukawa K, Osuka A. Stable Subporphyrin meso-Aminyl Radicals without Resonance Stabilization by a Neighboring Heteroatom. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:7435–7439. doi: 10.1002/anie.201703097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hioe J, Šakić D, Vrček V, Zipse H. The stability of nitrogen-centered radicals. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2015;13:157–169. doi: 10.1039/C4OB01656D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ivakhnenko EP, et al. The carboxyl derivatives of 6,8-di-(tert.-butyl)phenoxazine: Synthesis, oxidation reactions and fluorescence. Tetrahedron. 2019;75:538–544. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2018.12.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Di Motta S, et al. Biradicaloid and Polyenic Character of Quinoidal Oligothiophenes Revealed by the Presence of a Low-Lying Double-Exciton State. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2010;1:3334–3339. doi: 10.1021/jz101400d. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Izumi T, et al. Synthesis and Spectroscopic Properties of a Series of β-Blocked Long Oligothiophenes up to the 96-mer: Revaluation of Effective Conjugation Length. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003;125:5286–5287. doi: 10.1021/ja034333i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Casado J, Ortiz RP, Navarrete JTL. Quinoidal oligothiophenes: new properties behind an unconventional electronic structure. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:5672–5686. doi: 10.1039/c2cs35079c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang C, Zhu X. Thieno[3,4-b]thiophene-Based Novel Small-Molecule Optoelectronic Materials. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017;50:1342–1350. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sun Z, Huang K-W, Wu J. Soluble and Stable Heptazethrenebis(dicarboximide) with a Singlet Open-Shell Ground State. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:11896–11899. doi: 10.1021/ja204501m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li Y, et al. Kinetically Blocked Stable Heptazethrene and Octazethrene: Closed-Shell or Open-Shell in the Ground State? J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:14913–14922. doi: 10.1021/ja304618v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sun Z, et al. Dibenzoheptazethrene Isomers with Different Biradical Characters: An Exercise of Clar’s Aromatic Sextet Rule in Singlet Biradicaloids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:18229–18236. doi: 10.1021/ja410279j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hu P, Wu J. Modern zethrene chemistry. Can. J. Chem. 2017;95:223–233. doi: 10.1139/cjc-2016-0568. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Konishi A, et al. Synthesis and Characterization of Teranthene: A Singlet Biradical Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbon Having Kekulé Structures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:11021–11023. doi: 10.1021/ja1049737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kubo T, et al. Synthesis, Intermolecular Interaction, and Semiconductive Behavior of a Delocalized Singlet Biradical Hydrocarbon. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:6564–6568. doi: 10.1002/anie.200502303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Shimizu A, et al. Alternating Covalent Bonding Interactions in a One-Dimensional Chain of a Phenalenyl-Based Singlet Biradical Molecule Having Kekulé Structures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:14421–14428. doi: 10.1021/ja1037287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wehrmann CM, Charlton RT, Chen MS. A Concise Synthetic Strategy for Accessing Ambient Stable Bisphenalenyls toward Achieving Electroactive Open-Shell π-Conjugated Materials. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019;141:3240–3248. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b13300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ajayakumar MR, et al. Toward Full Zigzag-Edged Nanographenes: peri-Tetracene and Its Corresponding Circumanthracene. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:6240–6244. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b03711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cui Z, Abdurahman A, Ai X, Li F. Stable Luminescent Radicals and Radical-Based LEDs with Doublet Emission. CCS Chem. 2020;2:1129–1145. doi: 10.31635/ccschem.020.202000210. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ai X, et al. Efficient radical-based light-emitting diodes with doublet emission. Nature. 2018;563:536–540. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0695-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guo H, et al. High stability and luminescence efficiency in donor-acceptor neutral radicals not following the Aufbau principle. Nat. Mater. 2019;18:977–984. doi: 10.1038/s41563-019-0433-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abdurahman A, et al. Understanding the luminescent nature of organic radicals for efficient doublet emitters and purered light-emitting diodes. Nat. Mater. 2020;19:1224–1229. doi: 10.1038/s41563-020-0705-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhu X, et al. Air- and Heat-Stable Planar Tri-p-quinodimethane with Distinct Biradical Characteristics. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:16342–16345. doi: 10.1021/ja206060n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ren L, et al. Developing Quinoidal Fluorophores with Unusually Strong Red/Near-Infrared Emission. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015;137:11294–11302. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b03899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Uchida K, et al. Biphenalenylidene: Isolation and Characterization of the Reactive Intermediate on the Decomposition Pathway of Phenalenyl Radical. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016;138:2399–2410. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b13033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Montgomery LK, Huffman JC, Jurczak EA, Grendze MP. The molecular structures of Thiele’s and Chichibabin’s hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1986;108:6004–6011. doi: 10.1021/ja00279a056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ni Y, et al. A Chichibabin’s Hydrocarbon-Based Molecular Cage: The Impact of Structural Rigidity on Dynamics, Stability, and Electronic Properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020;142:12730–12742. doi: 10.1021/jacs.0c04876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ni Y, et al. 3D global aromaticity in a fully conjugated diradicaloid cage at different oxidation states. Nat. Chem. 2020;12:242–248. doi: 10.1038/s41557-019-0399-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rudebusch GE, et al. Diindeno-fusion of an anthracene as a design strategy for stable organic biradicals. Nat. Chem. 2016;8:753–759. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Dressler JJ, et al. Synthesis of the Unknown Indeno[1,2-a]fluorene Regioisomer: Crystallographic Characterization of Its Dianion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017;56:15363–15367. doi: 10.1002/anie.201709282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Shimizu A, Tobe Y. Indeno[2,1-a]fluorene: An Air-Stable ortho-Quinodimethane Derivative. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:6906–6910. doi: 10.1002/anie.201101950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shimizu A, et al. Indeno[2,1-b]fluorene: A 20-π-Electron Hydrocarbon with Very Low-Energy Light Absorption. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52:6076–6079. doi: 10.1002/anie.201302091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yang X, Liu D, Miao Q. Heptagon-Embedded Pentacene: Synthesis, Structures, and Thin-Film Transistors of Dibenzo[d,d’]benzo[1,2-a:4,5-a’]dicycloheptenes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014;53:6786–6790. doi: 10.1002/anie.201403509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yang X, et al. Benzo[4,5]cyclohepta[1,2-b]fluorene: an isomeric motif for pentacene containing linearly fused five-, six- and seven-membered rings. Chem. Sci. 2016;7:6176–6181. doi: 10.1039/C6SC01795A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ravat P, et al. Dimethylcethrene: A Chiroptical Diradicaloid Photoswitch. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018;140:10839–10847. doi: 10.1021/jacs.8b05465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shen J-J, et al. A Stable [4,3]Peri-acene Diradicaloid: Synthesis, Structure, and Electronic Properties. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2021;60:4464–4469. doi: 10.1002/anie.202012328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bleaney B, Bowers KD. Anomalous paramagnetism of copper acetate. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A. 1952;214:451–465. doi: 10.1098/rspa.1952.0181. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Lu T, Chen F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyser. J. Comput. Chem. 2012;33:580–592. doi: 10.1002/jcc.22885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Matsuo K, Saito S, Yamaguchi S. Photodissociation of B−N Lewis Adducts: A Partially Fused Trinaphthylborane with Dual Fluorescence. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014;136:12580–12583. doi: 10.1021/ja506980p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zheng, X. et al. One-Electron Oxidation of an Organic Molecule by B(C6F5)3; Isolationand Structures of Stable Non-para-substituted Triarylamine Cation Radical and Bis(triarylamine) Dication Diradicaloid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 14912–14915 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 78.Liao Y. Design and Applications of Metastable-State Photoacids. Acc. Chem. Res. 2017;50:1956–1964. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kortekaas L, Browne WR. The evolution of spiropyran: fundamentals and progress of an extraordinarily versatile photochrome. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019;48:3406–3424. doi: 10.1039/C9CS00203K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kundu PK, et al. Light-controlled self-assembly of non-photoresponsive nanoparticles. Nat. Chem. 2015;7:646–652. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shi Q, Meng Z, Xiang J-F, Chen C-F. Efficient control of movement in non-photoresponsive molecular machines by a photo-induced proton-transfer strategy. Chem. Commun. 2018;54:3536–3539. doi: 10.1039/C8CC01570H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Additional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the authors on reasonable request, see author contributions for specific data sets. Experimental details, additional characterizations, computational details, and figures including synthetic route, UV−vis-NIR spectra, 1H and 13C NMR spectra, 1D and 2D NOESY NMR spectra, MS spectra, EPR spectra, spin density and spin population (PDF) are described in the Supplementary Information. Cartesian coordinates are deposited in Supplementary Data 1 file. The X-ray crystallographic coordinates for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers CCDC 2132537 (4a), 2132539 (4b), 2132540 (4d), 2104545 (1a), 2104547 (1b), and 2132542 (1a2+). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. The CIF files of CCDC 2132537 (4a), 2132539 (4b), 2132540 (4d), 2104545 (1a), 2104547 (1b), and 2132542 (1a2+) are also included as Supplementary Data 2-Data 7.