Summary

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is an abundant mRNA modification affecting mRNA stability and protein expression. It is a highly dynamic process, and its outcomes during postnatal heart development are poorly understood. Here we studied m6A machinery in the left ventricular myocardium of Fisher344 male and female rats (postnatal days one to ninety; P1–P90) using Western Blot. A downward pattern of target protein levels (demethylases FTO and ALKBH5, methyltransferase METTL3, reader YTHDF2) was revealed in male and female rats during postnatal development. On P1, the FTO protein level was significantly higher in males compared to females.

Keywords: Epitranscriptomics, N6-methyladenosine, Postnatal development, Heart

Introduction

Epigenetic changes have significant importance during both heart development and the manifestation of heart diseases [1]. However, the role of epitranscriptomics, RNA epigenetics, has not yet been sufficiently explored in this area.

N6-methyladenosine (m6A) is the most prevalent internal chemical mark in mRNA. It is a dynamic and reversible modification that regulates RNA splicing, export from the nucleus, stability, and degradation [2]. The deposition of m6A methylation is mediated by proteins called “writers”. The most prominent one is methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3), the catalytic subunit of a multicomponent methyltransferase complex [3]. In contrast, fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) and alkB homolog 5 (ALKBH5) are “erasers” with the principal function of removing the m6A modification [4,5]. Besides m6A, FTO also demethylates m6Am, the main target of FTO in the cytosol, and N1-methyladenosine (m1A) in tRNA [6]. The biological functions of m6A are mediated by “readers” that bind to m6A-containing RNAs. YTH domain family 1–3 (YTHDF1-3) proteins are eminent m6A readers that all induce mRNA degradation [7]. The expression patterns of YTHDF paralogs differ across different cell types and tissues. Therefore, the dominant decay-inducing role is usually carried by the most abundant reader in particular cells. Importantly, YTHDF2 is often more highly expressed than YTHDF1 or YTHDF3 [7].

The m6A modification seems to have significant importance in the developing heart. Disruption in the proper functionality of m6A machinery proteins can lead to critical alterations in heart structure and function. For example, loss of enzymatic activity of FTO can lead to a ventricular septal defect, atrioventricular defect, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in humans [8]. Moreover, according to Su et al. [9], FTO levels drop in elderly murine hearts in response to acute myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury, while those in young hearts are unaffected. The function of ALKBH5 is linked with an improvement in cardiac function and regeneration after myocardial infarction in juvenile and adult mice [10]. Recent reports also show progressive alterations in m6A levels during heart development [10–13]. However, there is a lack of data regarding the detailed m6A machinery protein profiles in heart tissue during postnatal development and potential sex differences.

This pilot study aimed to investigate sex-specific changes in main m6A regulatory protein levels during postnatal development.

This study was conducted in accordance with the European Guidelines on Laboratory Animal Care. The use of animals was approved and supervised by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the Institute of Physiology of the Czech Academy of Sciences (No. 66/2021).

Animals

Fischer344 rats used for the experiments were bred and kept in the Faculty of Science of Charles University and sacrificed on postnatal days (P) 1, 4, 7, 10, 12, 14, 18, 21, 25, 28, and 90 with n = 4–12 in each group (Table 1). The higher number of individual samples in the early postnatal period was used because of their limited size. Rats were housed on a 12 h light/dark regime and were given unrestricted access to food and tap water.

Table 1.

The number of animals in pooled samples and concentration of total protein in samples of male and female rat hearts.

| Samples | Number of animals | Concentration (μg/μl) | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Males | |||

|

| |||

| P1 | 11 | 5.39 | 0.96 |

| P4 | 10 | 8.35 | 1.46 |

| P7 | 4 | 10.81 | 0.06 |

| P10 | 4 | 10.09 | 0.40 |

| P12 | 5 | 10.62 | 1.25 |

| P14 | 4 | 10.58 | 1.76 |

| P18 | 5 | 12.07 | 0.13 |

| P21 | 5 | 11.27 | 0.30 |

| P25 | 5 | 11.92 | 0.40 |

| P28 | 5 | 11.78 | 0.86 |

| P90 | 4 | 13.23 | 1.85 |

|

| |||

| Females | |||

|

| |||

| P1 | 9 | 6.43 | 0.87 |

| P4 | 12 | 11.82 | 1.92 |

| P7 | 6 | 11.54 | 2.52 |

| P10 | 6 | 10.18 | 1.58 |

| P12 | 4 | 10.75 | 0.60 |

| P14 | 5 | 10.47 | 1.76 |

| P18 | 5 | 10.82 | 1.87 |

| P21 | 5 | 10.32 | 1.44 |

| P25 | 5 | 11.73 | 2.15 |

| P28 | 5 | 12.37 | 0.96 |

| P90 | 5 | 11.86 | 1.44 |

P – postnatal day; SD – standard deviation

Tissue processing

Hearts were dissected into the right ventricle (RV) and left ventricle (LV) with septum and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Due to the limited size of the early postnatal LVs, all samples were grouped considering their age and sex and homogenized in eight volumes of ice-cold homogenization buffer (12.5 mM Tris, 2.5 mM EGTA, 250 mM sucrose, 6 mM β-mercaptoethanol, pH 7.4) with the addition of the protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Switzerland) as described previously [14]. The protein concentration (Table 1) was measured using the Bradford assay (Bio-Rad, USA). Protein concentration was significantly lower at P1 compared to other days in both sexes. In males, the protein concentration increased gradually from P1 to P7, while in females there was a dramatic change between P1 and P4. The differences in protein concentration indicate significant changes in the ratio of dry mass to water in heart tissue in the early postnatal period. Our observation is in agreement with the already reported rapid postnatal decline in water content in heart tissue [15].

Immunoblotting

Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE electrophoresis (10% gels) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes (BioRad, USA; 1620177). The membranes were blocked using 5 % dry low-fat milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (TBST) for 1 h at room temperature and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against: FTO [5-2H10] (Abcam, UK; ab92821, 1:1,000), ALKBH5 [EPR18958] (Abcam, UK; ab195377, 1:1,500), METTL3 [EPR18810] (Abcam, UK; ab195352, 1:1,000), YTHDF2 (Invitrogen, USA; PA5-70853, 1:1,000). The membranes were subsequently incubated for 1 h at room temperature with secondary anti-rabbit (Bio-Rad, USA; 170-6515, 1:10,000) or anti-mouse (Invitrogen, USA; 31432, 1:10,000) antibodies. The chemiluminescence was measured by ChemiDoc™ System (Bio-Rad, USA). Ponceau S staining (Sigma-Aldrich, USA; P7170) was used as a loading control. It was shown as an effective way of normalization of samples of different developmental phases [16]. Both male and female protein levels were expressed as fold change over the corresponding P90 male signal (equal to 1). Female protein levels were recalculated to relevant P90 male signals to enable the quantification of sex-dependent differences.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8 (GraphPad Software, Inc.). One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used for the assessment of the statistical significance within sex. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used for the assessment of the statistical significance of sex differences. The data were obtained from at least three experiments and are displayed as means ± standard deviation (SD). Results were recognized as statistically significant when P < 0.05 (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001).

Protein level profiles of m6A machinery during postnatal development in male and female hearts

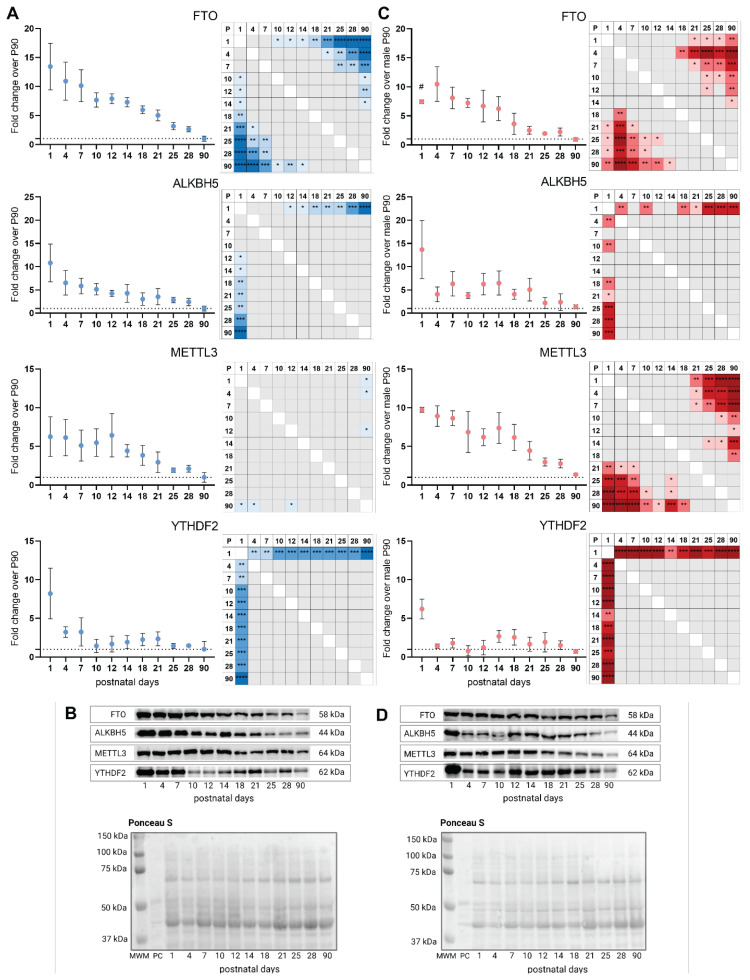

To investigate protein levels during postnatal development, we performed a western blot of LV tissue lysates collected from rats on postnatal days 1, 4, 7, 10, 12, 14, 18, 21, 25, 28, and 90. We examined the erasers (FTO, ALKBH5), writer (METTL3), and reader (YTHDF2) proteins of m6A modification. YTHDF2 was chosen because of its highest expression among the paralogs in male LV (with the lowest Cq value indicating the highest gene abundance of Ythdf2 (25.20 ± 0.47) compared to Ythdf1 (25.91 ± 0.25) and Ythdf3 (25.59 ± 0.64)). Firstly, we revealed that the abundance profile of all target proteins had a decreasing pattern during postnatal development (P1–P90) (Fig. 1). ALKBH5 and YTHDF2 declined dramatically between P1–P4 with further indistinct changes in protein levels. FTO and METTL3 protein expression dropped gradually throughout the investigated period. Concerning sex-related differences, it was found that the FTO level is significantly higher (by 40.6 ± 21.4 %) at P1 in males compared to females.

Fig. 1.

The protein levels of the m6A regulators in male and female rat hearts. A) Immunoblot analysis and multiple comparisons of the immunoblotting data of fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO), alkB homolog 5 (ALKBH5), methyltransferase-like 3 (METTL3), and YTHDF2 (YTH domain family 2) in LV tissue homogenates from P1–P90 male rats. B) Representative western blot membranes displaying FTO, ALKBH5, METTL3, and YTHDF2 protein levels in LV tissue homogenates from P1–P90 male rats and the representative total protein Ponceau S staining. C) Immunoblot analysis and multiple comparisons of the immunoblotting data of FTO, ALKBH5, METTL3 and YTHDF2 in LV tissue homogenates from P1–P90 female rats. D) Representative western blot membranes displaying FTO, ALKBH5, METTL3, and YTHDF2 protein levels in LV tissue homogenates from P1–P90 female rats and the representative total protein Ponceau S staining. Homogenates were pooled with n = 4–12 in each group (details in Table 1). All the protein expression levels were normalized to Ponceau S staining. Both male and female protein levels were expressed as fold change over the corresponding P90 male signal (equal to 1). Experiments were performed independently three times. Protein loading was 15 μg. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 (One-way ANOVA; Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). #P < 0.01 compared to corresponding P1 males (Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test). MWM – molecular weight marker, P – postnatal day, PC – positive control (rat brain).

Our present study provides insights into the dynamics of m6A eraser, writer, and reader protein levels through postnatal development from P1 to P90 in rat left ventricles of both sexes. We showed that all proteins revealed a downward expression pattern with either a dramatic drop during the first critical period from P1 to P4 (ALKBH5 and YTHDF2) or a gradual decline till adulthood (FTO, METTL3). The decreasing patterns of METTL3 and ALKBH5 levels correspond to previously published reports [10,12]. Han et al. [10] utilized a mouse model and analyzed hearts at P1, P7, and P10. They showed the downregulation of protein and gene levels of ALKBH5 throughout this early developmental period. Also, Yang et al. [12] found a higher protein expression of ALKBH5 and METTL3 at P0 than at P7 in the rat heart, while the FTO level remained unchanged. In contrast, Yang et al. [13] found that the METTL3 level in mouse hearts is higher at P7 and P28 compared to P1. FTO protein level revealed a similar decreasing pattern as was observed in our study, its level at P1 was higher than at P7 and P28 [13]. Utilizing the porcine model, Ferenc et al. [17] showed differences in FTO expression between neonatal samples and adult ones in other tissues: skeletal muscle along with the thyroid gland and adipose tissue displayed the higher FTO signal in the neonatal period.

Interestingly, we observed that the FTO protein level in males is higher than in females at P1. The sex-dependent differences provoked by Fto level disruption were found in several reports. For example, sex-specific changes in body weight were observed upon overexpression of Fto in mice, with females showing a slightly higher weight gain than males [18]. At the time of weaning, both male and female Fto knockout mice were about 65 % the weight of wild-type and heterozygous littermates. Nevertheless, Fto knockout male mice displayed persistent weight loss throughout their life, while female Fto knockout tended to make up the weight deficit by adulthood [19]. It may suggest a more significant role of FTO during the embryonic and early neonatal period in males that is in line with our data, where at P1 FTO level was higher in male samples than in female ones.

In conclusion, this study thoroughly assessed the protein levels of m6A machinery in rat LVs of both sexes during postnatal development. A downward pattern of all target protein levels was revealed in both sexes. Moreover, the FTO protein level was significantly higher in males compared to females on P1.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the Charles University Grant Agency (grant number 1076119) and the Czech Science Foundation (grant number 19-04790Y).

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

There is no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Jarrell DK, Lennon ML, Jacot JG. Epigenetics and Mechanobiology in Heart Development and Congenital Heart Disease. Diseases. 2019;7(3) doi: 10.3390/diseases7030052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peer E, Rechavi G, Dominissini D. Epitranscriptomics: regulation of mRNA metabolism through modifications. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2017;41:93–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2017.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Liu J, Yue Y, Han D, Wang X, Fu Y, Zhang L, Jia G, Yu M, Lu Z, Deng X, Dai Q, Chen W, He C. A METTL3-METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat Chem Biol. 2014;10(2):93–95. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jia G, Fu Y, Zhao X, Dai Q, Zheng G, Yang Y, Yi C, Lindahl T, Pan T, Yang YG, He C. N6-methyladenosine in nuclear RNA is a major substrate of the obesity-associated FTO. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7(12):885–887. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zheng G, Dahl JA, Niu Y, Fedorcsak P, Huang CM, Li CJ, Vågbø CB, Shi Y, Wang WL, Song SH, Lu Z, Bosmans RP, Dai Q, Hao YJ, Yang X, Zhao WM, Tong WM, Wang XJ, Bogdan F, Furu K, Fu Y, Jia G, Zhao X, Liu J, Krokan HE, Klungland A, Yang YG, He C. ALKBH5 is a mammalian RNA demethylase that impacts RNA metabolism and mouse fertility. Mol Cell. 2013;49(1):18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wei J, Liu F, Lu Z, Fei Q, Ai Y, He PC, Shi H, Cui X, Su R, Klungland A, Jia G, Chen J, He C. Differential m(6)A, m(6)A(m), and m(1)A Demethylation Mediated by FTO in the Cell Nucleus and Cytoplasm. Mol Cell. 2018;71(6):973–985. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lasman L, Krupalnik V, Viukov S, Mor N, Aguilera-Castrejon A, Schneir D, Bayerl J, Mizrahi O, Peles S, Tawil S, Sathe S, Nachshon A, Shani T, Zerbib M, Kilimnik I, Aigner S, Shankar A, Mueller JR, Schwartz S, Stern-Ginossar N, Yeo GW, Geula S, Novershtern N, Hanna JH. Context-dependent functional compensation between Ythdf m(6)A reader proteins. Genes Dev. 2020;34(19–20):1373–1391. doi: 10.1101/gad.340695.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boissel S, Reish O, Proulx K, Kawagoe-Takaki H, Sedgwick B, Yeo GS, Meyre D, Golzio C, Molinari F, Kadhom N, Etchevers HC, Saudek V, Farooqi IS, Froguel P, Lindahl T, O’Rahilly S, Munnich A, Colleaux L. Loss-of-function mutation in the dioxygenase-encoding FTO gene causes severe growth retardation and multiple malformations. Am J Hum Genet. 2009;85(1):106–111. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Su X, Shen Y, Jin Y, Kim IM, Weintraub NL, Tang Y. Aging-Associated Differences in Epitranscriptomic m6A Regulation in Response to Acute Cardiac Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury in Female Mice. Front Pharmacol. 2021;12:654316. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.654316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Han Z, Wang X, Xu Z, Cao Y, Gong R, Yu Y, Yu Y, Guo X, Liu S, Yu M, Ma W, Zhao Y, Xu J, Li X, Li S, Xu Y, Song R, Xu B, Yang F, Bamba D, Sukhareva N, Lei H, Gao M, Zhang W, Zagidullin N, Zhang Y, Yang B, Pan Z, Cai B. ALKBH5 regulates cardiomyocyte proliferation and heart regeneration by demethylating the mRNA of YTHDF1. Theranostics. 2021;11(6):3000–3016. doi: 10.7150/thno.47354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gong R, Wang X, Li H, Liu S, Jiang Z, Zhao Y, Yu Y, Han Z, Yu Y, Dong C, Li S, Xu B, Zhang W, Wang N, Li X, Gao X, Yang F, Bamba D, Ma W, Liu Y, Cai B. Loss of m(6)A methyltransferase METTL3 promotes heart regeneration and repair after myocardial injury. Pharmacol Res. 2021;174:105845. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang C, Zhao K, Zhang J, Wu X, Sun W, Kong X, Shi J. Comprehensive Analysis of the Transcriptome-Wide m6A Methylome of Heart via MeRIP After Birth: Day 0 vs. Day 7. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:633631. doi: 10.3389/fcvm.2021.633631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang Y, Shen S, Cai Y, Zeng K, Liu K, Li S, Zeng L, Chen L, Tang J, Hu Z, Xia Z, Zhang L. Dynamic Patterns of N6-Methyladenosine Profiles of Messenger RNA Correlated with the Cardiomyocyte Regenerability during the Early Heart Development in Mice. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021;2021:5537804. doi: 10.1155/2021/5537804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Holzerová K, Hlaváčková M, Žurmanová J, Borchert G, Neckář J, Kolář F, Novák F, Nováková O. Involvement of PKCepsilon in cardioprotection induced by adaptation to chronic continuous hypoxia. Phys Res. 2015;64(2):191–201. doi: 10.33549/physiolres.932860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Solomon S, Wise P, Ratner A. Postnatal Changes of Water and Electrolytes of Rat Tissues. 1976;153(2):359–362. doi: 10.3181/00379727-153-39545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sander H, Wallace S, Plouse R, Tiwari S, Gomes AV. Ponceau S waste: Ponceau S staining for total protein normalization. Anal Biochem. 2019;575:44–53. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2019.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ferenc K, Pilzys T, Garbicz D, Marcinkowski M, Skorobogatov O, Dylewska M, Gajewski Z, Grzesiuk E, Zabielski R. Intracellular and tissue specific expression of FTO protein in pig: changes with age, energy intake and metabolic status. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):13029. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-69856-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Church C, Moir L, McMurray F, Girard C, Banks GT, Teboul L, Wells S, Brüning JC, Nolan PM, Ashcroft FM, Cox RD. Overexpression of Fto leads to increased food intake and results in obesity. Nat Genet. 2010;42(12):1086–1092. doi: 10.1038/ng.713. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.713. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gao X, Shin YH, Li M, Wang F, Tong Q, Zhang P. The fat mass and obesity associated gene FTO functions in the brain to regulate postnatal growth in mice. PLoS One. 2010;5(11):e14005. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0014005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]