Abstract

The recent isolation of a lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-deficient mutant of Neisseria meningitidis has allowed us to explore the roles of other gram-negative cell wall components in the host response to infection. The experiments in this study were designed to examine the ability of this mutant strain to activate cells. Although it was clearly less potent than the parental strain, we found the LPS-deficient mutant to be a capable inducer of the inflammatory response in monocytic cells, inducing a response similar to that seen with Staphylococcus aureus. Cellular activation by the LPS mutant was related to expression of CD14, a high-affinity receptor for LPS and other microbial products, as well as Toll-like receptor 2, a member of the Toll family of receptors recently implicated in host responses to gram-positive bacteria. In contrast to the parental strain, the synthetic LPS antagonist E5564 did not inhibit the LPS-deficient mutant. We conclude that even in the absence of LPS, the gram-negative cell wall remains a potent inflammatory stimulant, utilizing signaling pathways independent of those involved in LPS signaling.

A common and serious consequence of overwhelming bacterial infections is the development of septic shock and associated organ failure. The pathogenesis of the shock is presumed to be secondary to excessive stimulation of host cells by microbial constituents, which are potent activators of inflammatory cytokine synthesis. While activation of cytokine synthesis is an important component of the innate immune response to infection, excessive cytokine production is likely an important mechanism of lethal septic shock. Various components of the bacterial cell wall are capable of activating this proinflammatory response. In the case of sepsis due to gram-negative bacteria, excessive stimulation of host cells by bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is considered to be key to the development of the shock. Other important cell wall components, such as peptidoglycan, lipoteichoic acid, lipoarabinomannan, and lipoproteins, are believed to play a role in other bacterial species, along with secreted toxins and superantigens. Finally, certain unmethylated bacterial DNA sequences have been found to have costimulatory activity.

The cellular receptors for bacterial lipopolysaccharide include CD14, a glycosylphosphatidylinositol-linked membrane protein on macrophages and monocytes (18, 60, 63) and, to a lesser extent, on polymorphonuclear neutrophils (2, 32). One of the earliest cell-mediated events following endotoxin release from gram-negative bacteria appears to involve the transfer of LPS to CD14. In addition to being a high-affinity receptor for LPS, CD14 also binds several other microbial products, including mycobacterial lipoarabinomannan (41, 47), peptidoglycan (10, 56, 57) and other cell wall components of Staphylococcus aureus (26, 27), streptococcal rhamnose glucose polymers (51), mannuronic acid polymers (11), and yeast W-1 antigen (37).

The important role of CD14 in LPS responses is validated by the observation that CD14 knockout mice are resistant to lethal endotoxin shock after LPS or bacterial challenge (16, 17). However, because CD14 is glycosylphosphatidylinositol anchored, it is not believed to directly transduce a signal for cellular activation. Toll-like receptors have now been implicated in LPS signaling and are thought to play a role as transmembrane signal transducers. Specifically, the defects in the LPS-hyporesponsive C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice have been identified as Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) defects (40). TLR4 knockout mice have been genetically engineered and confirm that expression of TLR4 regulates LPS responsiveness (21). In contrast to TLR4, TLR2 appears to play a broader role in recognition of a variety of bacteria and bacterial antigens, including gram-positive bacteria, spirochetes, mycobacteria, and mycoplasmas (1, 13, 20, 24, 31, 33, 48, 62).

The roles played by other components of the gram-negative bacterial cell wall in the pathogenesis of sepsis have been difficult to evaluate because of the presence of endotoxin (LPS) in the membrane. The basic LPS structure consists of a hydrophilic heteropolysaccharide covalently bound to a lipid component known as lipid A. The lipid A core of LPS appears to be conserved among the family of gram-negative bacteria and is the portion of the LPS molecule responsible for the biological toxicity of endotoxin (reviewed in reference 43). LPS is an extremely potent toxin, and macrophage activation typically begins at concentrations of LPS as low as 1 pg/ml. Previous attempts to engineer LPS-deficient strains of Escherichia coli failed, suggesting that LPS was required for viability of gram-negative bacteria. However, Steeghs and colleagues isolated an endotoxin-deficient strain of Neisseria meningitidis by inactivating the UDP-GlcNAc acyltransferase encoded by lpxA, creating a block in the first step of lipid A biosynthesis (53). While this lpxA mutant strain completely lacks endotoxin, it still expresses the immunodominant outer membrane proteins in normal amounts (53).

Recently, Steeghs and colleagues reported that the immunogenicity of the outer membrane proteins of this mutant meningococcus was poor, consistent with earlier observations that LPS functioned as an adjuvant (52). In this study, we describe the proinflammatory activity of the LPS-deficient meningococcus in terms of activating translocation of the transcription factor NF-κB and release of tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α). Although whole bacteria and bacterial lysates from the LPS-deficient strain were less potent than the parental strain, they still retained stimulatory activity. Furthermore, we found that TLR2, and not TLR4, was essential for the cellular responses. The data demonstrate that gram-negative bacteria can utilize multiple Toll-like receptors to activate cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), Ham's F-12 medium, RPMI 1640, and trypsin-EDTA were obtained from Bio-Whittaker (Walkersville, Md.). MCDB-131 medium and G418 were purchased from Gibco-BRL Life Sciences (Gaithersburg, Md.). Hygromycin B was purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, Calif.), puromycin and mouse immunoglobulin G were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, Mo.), fetal calf serum (LPS concentration of less than 10 pg/ml) was purchased from Summit Biotechnology (Greeley, Colo.), and ciprofloxacin was purchased from Miles Pharmaceuticals (West Haven, Conn.). Purified monoclonal antibody 3C10, an anti-human CD14 antibody, was a gift from Terje Espevik (Norweigan University of Science and Technology, Trondheim). RQ1 RNase-Free DNase was obtained from Promega (Madison, WI). LPS from N. meningitidis strain H44/76 was a gift from K. Bryn (The National Institute of Public Health, Oslo, Norway) (4). Rhodobacter sphaeroides diphosphoryl lipid A was a gift from Nilo Qureshi (University of Wisconsin, Madison). Compound E5564 (patent reference number WO-9639411-A1) was prepared at Eisai Research Institute (Andover, Mass.). Lipids were prepared as 1-mg/ml dispersed sonicates in pyrogen-free PBS and stored at −20°C. Prior to use, the suspensions were thawed and sonicated for 3 min in a water bath sonicator (Laboratory Supplies, Hicksville, N.Y.) before dilution to the final concentration.

Bacterial preparations.

The N. meningitidis lpxA mutant (53) and the parental strain (H44/76) were grown overnight on chocolate agar. The next day, colonies were scraped, resuspended in PBS to an optical density at 600 nm of 1 (or 109 CFU/ml), and stored at 4°C until ready for use. Membrane particulates were prepared using a French press at 18,000 lb/in2. Unbroken cells were removed by centrifugation at 8,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C and stored at −20°C. Membranes were prepared from the lysates by ultracentrifugation at 150,000 × g for 1 h at 4°C. The membrane pellet was resuspended in PBS and stored at 4°C. Protein concentrations for both were determined using the Bio-Rad (Hercules, Calif.) protein assay agent with a bovine serum albumin standard. Endotoxin contamination of mutant lysates and membranes was 0.21 and 0.39 endotoxin unit/μg protein, respectively, by the Limulus amebocyte lysate pyrochrome assay (Cape Cod Associates) (12 endotoxin units ∼ 1 ng of LPS).

Cell lines.

The CHO/CD14.ELAM.Tac reporter cell line (clone 3E10) expresses inducible membrane CD25 (Tac antigen) under control of a region from the human E-selection (ELAM-1) promoter containing nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) binding sites; this promoter element is absolutely dependent upon NF-κB (9). Cell lines were grown as adherent monolayers in Ham's F-12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum, 10 μg of ciprofloxacin per ml, and 400 U of hygromycin B per ml at 37°C in 5% CO2 and passaged twice a week to maintain logarithmic growth. CHO/CD14 reporter cells expressing TLRs were engineered by stable transfection with the cDNA for human TLR2 or TLR4 as described previously (31, 62). The TLR-expressing cell lines were maintained in additional selection antibiotics (for 3E10/TLR2, 0.5 mg of G418 per ml, for 3E10/TLR4, 50 μg of puromycin per ml).

Isolation and stimulation of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs).

Whole blood was collected into syringes containing 75 U of heparin sodium/ml of blood and then gently layered over Histopaque (Sigma) at a ratio of 2.5:1. The layered blood and medium were centrifuged at room temperature at 400 × g for 30 min, and mononuclear cells were recovered from the plasma-medium interface. The cells were washed twice in RPMI 1640 with 10% heat-inactivated human serum and plated in 96-well dishes at a density of 106 cells per well. When appropriate, LPS antagonists or the anti-CD14 monoclonal antibody (MAb) was added to the cell suspension immediately before plating. Serial dilutions of stimulus (LPS, bacteria, or bacterial lysates) were then added to the wells, and the cells were incubated overnight at 37°C with 5% CO2. The next day, plates were centrifuged at 400 × g for 5 min at 4°C, after which cell culture supernatants were collected. Cells from all experimental conditions were plated in duplicate.

Supernatants were assayed for TNF-α by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using anti-TNF-α MAb clone 6H11 (10 μg/ml) (29) as the capture antibody and anti-TNF-α–peroxidase (POD) MAb, Fab fragments, clone 195 (Roche Molecular Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.), as the detection antibody. ELISA was carried out according to the manufacturer's protocol for the POD-conjugated antibody. The optical density was measured using a Bio-Kinetics microplate reader (Bio-Tek Instruments, Winooski, Vt.) and compared to a standard curve generated using recombinant TNF-α (Roche Molecular Biochemicals).

Flow cytometry analysis.

Cells were plated at a density of 105/well in 24-well dishes. The following day, the cells were stimulated as indicated below in Ham's F12 medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (total volume of 0.25 ml/well). Subsequently, the cells were harvested with trypsin-EDTA, and labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-CD25 (Becton Dickinson Immunocytometry Systems, San Jose, Calif.) in PBS–1% FBS for 30 min on ice. After labeling, the cells were washed once, resuspended in PBS–1% FBS, and analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACScan microfluorimeter (Becton Dickinson).

RESULTS

LPS-deficient N. meningitidis activates TNF-α release from PBMCs.

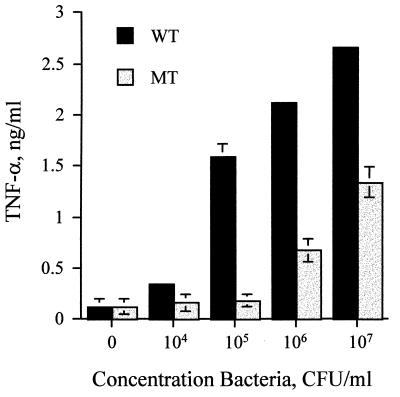

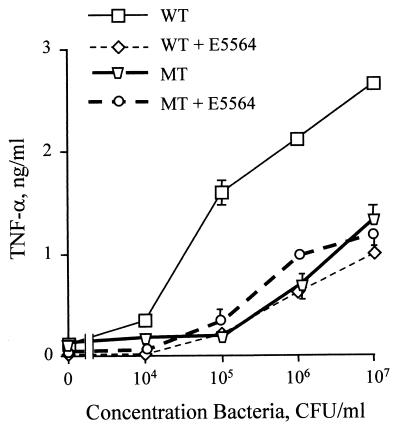

In order to test the proinflammatory activity of the LPS-deficient N. meningitidis, PBMCs were incubated with increasing concentrations of bacteria and the supernatant was assayed for TNF-α. The mutant bacterial strain was significantly less potent than the parental strain, requiring approximately 100-fold more bacteria to achieve equivalent amounts of TNF-α release (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

LPS-deficient N. meningitidis activates TNF-α release from PBMCs. PBMCs were stimulated with bacterial suspensions from both the wild-type (WT) and LPS-deficient mutant (MT) strains. Supernatant was collected after 18 h and assayed for TNF-α by ELISA. These results are representative of those from at least four independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

Proinflammatory activity of the LPS-deficient mutant is retained in bacterial membranes.

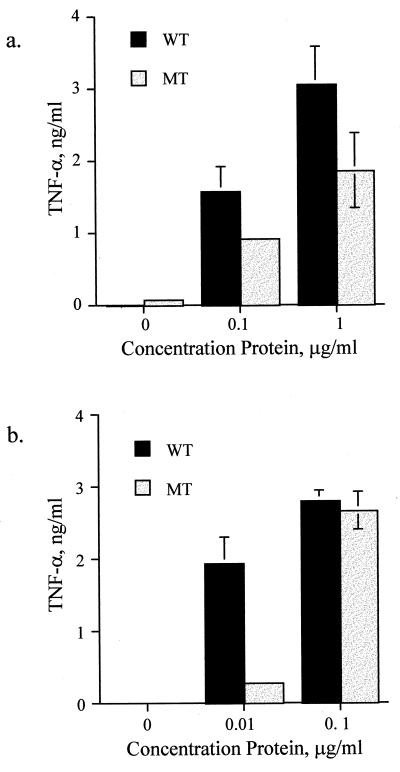

Because of the concern that the two bacterial suspensions might not be equivalent in concentration when measured by optical density, we prepared bacterial membrane particulates from suspension cultures and equalized them for protein concentration. When these lysates were tested for their ability to activate PBMCs, we found that the proinflammatory activity was preserved (Fig. 2a). Although it remained less potent than the parental line, the dose-response difference was not as great as that observed with the whole bacteria.

FIG. 2.

LPS-deficient N. meningitidis activates TNF-α release from PBMCs. PBMCs were stimulated with lysates (a) or membrane preparations (b) from both the wild-type (WT) and LPS-deficient mutant (MT) strains. Supernatant was collected after 18 h and assayed for TNF-α by ELISA. These results are representative of those from at least two independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

Because the crude membrane particulates contain both intracellular and membrane proteins, as well as bacterial DNA, we attempted to further purify our preparations. First, the suspension was subjected to DNase treatment. This failed to eradicate the stimulatory activity, suggesting that the source was not bacterial DNA (data not shown). Similarly, boiling the preparations had no effect on their activity (data not shown). Outer membranes were then purified from the lysates by differential centrifugation. When tested in our assay, the membrane preparations from both bacterial strains were found to be remarkably potent inducers of TNF, saturating release of TNF-α at a dose of only 0.1 μg/ml (Fig. 2b). This suggested that the active factor for both strains was concentrated in the membranes.

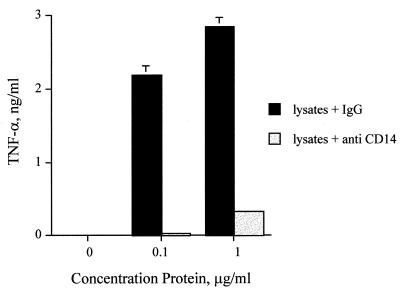

Cellular activation by LPS-deficient N. meningitidis requires CD14 expression.

In addition to being a high-affinity receptor for LPS (60), CD14 also binds several other microbial products, including peptidoglycan (10, 15, 56), other cell wall components of S. aureus (26, 27), and Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins (49, 59). In order to determine if CD14 was required for cellular activation by the lpxA mutant meningococcus, we stimulated PBMCs in the presence or absence of the anti-human CD14 MAb 3C10. We found that the CD14 antibody completely blocked TNF-α release from PBMCs for the LPS-deficient meningococcus (Fig. 3). Similar inhibition was observed when PBMCs were stimulated with the parental strain (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

LPS-deficient N. meningitidis is blocked by anti-CD14 MAb. PBMCs were stimulated with bacterial lysates from the LPS-deficient bacteria, in the presence of either 5μg of anti-CD14 MAb 3C10 per ml or control mouse immunoglobulin G (IgG). Supernatant was collected after 18 h and assayed for TNF-α by ELISA. These results are representative of those from two independent experiments. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

LPS-deficient N. meningitidis requires TLR2 expression for cellular activation.

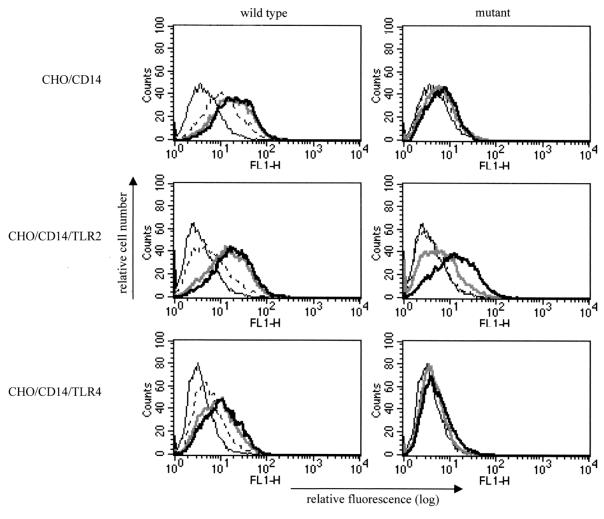

Recently, TLR-4 has been described as an essential receptor for responses to LPS (7, 21, 38). In contrast, TLR2 expression has been reported to confer responsiveness to gram-positive bacteria, peptidoglycan, and lipoteichoic acid (48, 62). Likewise, bacterial lipoproteins have also been reported to utilize TLR2 (1, 5, 20, 31, 55). In addition to LPS, the gram-negative cell wall contains numerous components, such as peptidoglycan and lipoproteins, which could account for the activity of the mutant meningococcus. Thus, we hypothesized that the LPS-deficient meningococcus would require TLR2 for cellular activation, while the parental strain, which expresses LPS, would utilize TLR4 in addition to TLR2.

In order to test this hypothesis, we first took advantage of the observation that CHO-K1 fibroblasts lack functional TLR2 (19) and therefore do not respond to peptidoglycan or lipoproteins unless transfected with TLR2 (31, 62). We previously constructed human TLR2- and human TLR4-expressing reporter cell lines in a CHO-K1 background that expressed CD14 constitutively and contained an inducible NF-κB-dependent promoter driving expression of surface CD25 (9, 31, 62). We exposed the CHO/CD14, CHO/CD14/TLR2, and CHO/CD14/TLR4 reporter cell lines to bacteria and bacterial lysates and quantified the induction of proinflammatory activity by measuring upregulation of CD25 expression. The parental meningococcus was a potent activator of the CHO/CD14 reporter, increasing the mean fluorescence by threefold over that of the unstimulated cells, while the LPS-deficient meningococcus was inactive (Fig. 4, top row). However, when transfected with human TLR2, the reporter cells acquired responsiveness to low doses of the LPS-deficient bacterial preparations, although the dose-response shift for the LPS mutant remained less potent than that for the parental strain (Fig. 4, middle row). In contrast to the case for TLR2, we found that expression of TLR4 was not sufficient for sensitive responses to the LPS-deficient meningococcus. Neither CHO/CD14 cells, which express native hamster TLR4, nor CHO/CD14/TLR4 cells, which overexpress human TLR4, could be activated by the mutant strain (Fig. 4, bottom row).

FIG. 4.

LPS-deficient N. meningitidis requires TLR2 for cellular activation. CHO/CD14, CHO/CD14/TLR2, and CHO/CD14/TLR4 reporter cells were stimulated with increasing concentrations of bacterial lysates from either the wild-type line or the LPS-deficient mutant N. meningitidis and assayed for upregulation of the NF-κB-driven CD25 reporter. Shown are fluorescence-activated cell sorter histograms for the indicated cell lines from 10,000 events counted. The vertical axis represents the relative cell number, while the horizontal axis represents the intensity of fluorescence staining for the CD25 reporter. The concentrations of stimulant used are as follows: thin black line, unstimulated; dashed line, 0.01 μg of protein per ml; thick gray line, 0.1 μg/ml; thick black line, 1 μg/ml.

LPS-deficient N. meningitidis is not inhibited by the TLR4 antagonist E5564.

One interesting aspect of LPS-induced signaling is that there are lipid A-like molecules that inhibit the proinflammatory effects of endotoxin. For example, the biologically derived lipid A analog lipid IVA (also known as compound Ia or 406) and R. sphaeroides lipid A are potent LPS antagonists in LPS-responsive human cells (14, 25, 54). Several chemically stable and homogenous analogs of these LPS antagonists have been successfully synthesized and have been observed to inhibit LPS both in vitro and in experimental animal models of sepsis (8, 22). The target of these receptor antagonists is now believed to be TLR4 (30, 39).

In order to determine if the specific LPS antagonists would have any effect on the activity observed with the mutant strain, we preincubated the PBMCs with a 1-mg/ml concentration of the synthetic lipid A analog E5564 prior to stimulation with whole bacteria or bacterial lysates. This compound has been previously shown to be a potent inhibitor of LPS (22) and was able to significantly inhibit the wild-type meningococcus while having no effect on the LPS-deficient mutant bacterium (Fig. 5) or its bacterial lysates (data not shown). A second LPS antagonist, R. sphaeroides lipid A, also had no effect on the mutant meningococcus. It was interesting that in the presence of the LPS antagonist, the activity of the wild-type strain was nearly identical to that of the LPS mutant, confirming that the other components of the gram-negative membrane were activating the PBMCs in a TLR4-independent manner.

FIG. 5.

LPS-deficient N. meningitidis is not blocked by the LPS antagonist E5564. PBMCs were stimulated with increasing concentrations of bacteria from the wild-type (WT) or LPS-deficient (MT) strain in the presence and absence of the LPS antagonist E5564. Supernatant was collected after 18 h assayed for TNF-α by ELISA. These results are representative of those from two independent experiments. Similar results were found using another antagonist, R. sphaeroides lipid A (data not shown). Error bars indicate standard deviations.

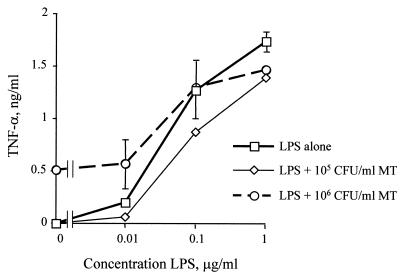

Proinflammatory effects of LPS and bacterial membrane are not synergistic.

Because it appeared that the bacterial membrane was utilizing a different Toll receptor (TLR2) than bacterial LPS (TLR4), we wanted to determine if the two stimuli might be capable of acting synergistically. We therefore stimulated PBMCs with increasing concentrations of bacterial lysates from the LPS mutant meningococcus in the presence or absence of LPS purified from the parental H44/76 N. meningitidis strain. We were unable to find any evidence of synergy in terms of TNF-α release when LPS was combined with bacterial membrane preparations (Fig. 6). In fact, the effects were additive only at the lower dose of LPS used. Similar results were found when the CHO/CD14/TLR2 reporter line was examined (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

The combined effects of LPS and the bacterial membrane are not synergistic. PBMCs were stimulated with increasing concentrations of LPS derived from N. meningitidis strain H44/76 in the presence or absence of the LPS-deficient bacteria (MT). Supernatant was collected after 18 h and assayed for TNF-α by ELISA. There was no evidence of synergy when the LPS was combined with preparations of bacteria, although at the lower doses of LPS the effects were additive. Comparable results were observed when the reporter line 3E10/TLR2 was stimulated in a similar manner. Error bars indicate standard deviations.

DISCUSSION

The inflammatory response to bacterial infections plays an important role in the detection and elimination of invading microorganisms. Cells of the innate immune system are the first line of defense in detection and clearance of bacteria. Their ability to sense invading pathogens by virtue of nonclonal pattern recognition receptors that interact with microbial structures is an essential step in alerting the host cell to the danger of invading pathogens (34). Moreover, the innate immune system helps coordinate the adaptive immune response through release of soluble factors and costimulatory signals provide by antigen-presenting cells (12).

The innate immune responses of insects, plants, and vertebrates are remarkably similar in their molecular components. In Drosophila, the immune response to fungal infection is dependent on Toll, a type I transmembrane receptor that shares homology to components of the interleukin-1 signaling pathway (3). Toll was initially identified as a receptor involved in embryonic development, where it controls dorsoventral polarization (3, 36). It was later demonstrated that Toll and the related molecule 18-Wheeler control important antimicrobial responses against both fungi and bacteria in the adult fly (28, 58). Mammalian homologs of Toll have been cloned and designated TLRs (6, 35, 44). At least 10 such receptors have been identified, and two of them, TLR2 and TLR4, have been implicated in cellular responses to microbial pathogens. While both TLR2 (24, 61) and TLR4 (38, 40) were initially implicated in LPS responses (7, 21, 38, 40, 42), the overwhelming evidence to date suggests that these two receptors have different roles in the recognition of pathogens. TLR4 is required for sensitive responses to LPS (7, 21, 38, 40, 42), while TLR2 has a broader role as a pattern recognition receptor for a variety of microbes and microbial structures (1, 13, 20, 24, 31, 33, 48, 62). While individual bacterial components might preferentially signal through specific receptors, our data demonstrate that gram-negative bacteria in fact utilize multiple Toll-like receptors to activate cells. Thus, while TLR4 may be the dominant receptor for purified LPS preparations, it is likely that during gram-negative infections, multiple receptors are capable of recognizing bacteria and signaling activation of the proinflammatory cascade.

The particular ligand or ligands that are responsible for the activity that we observed in the LPS-deficient meningococcus are unclear at this time. While the crude French press lysates would contain all intracellular proteins, the ability of the activating factor(s) to be concentrated during differential centrifugation suggests that it is closely associated with the bacterial membrane. This would include proteins and lipoproteins, peptidoglycan, porins, and a variety of phospholipids that have been shown in other settings to be potent activators of the inflammatory response. Any one of these could account for the cellular activation induced by the lpxA mutant. Since several of these microbial components, including peptidoglycan (48, 62) and lipoproteins (1, 20, 31), have been linked to TLR2, we cannot determine from our data if one of them is the dominant player. In addition, while by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis analysis and whole-cell ELISA the mutant and parental strains appear to have similar major outer membrane proteins (53), there could be proteins expressed differentially in the membrane of the LPS-deficient strain that are not detected by these methods. For example, others have reported that lipid A mutations disturb the outer membrane biosynthesis, leading to changes in the phospholipid (23) and fatty acid (45, 46) contents and localization of porins (50). Clearly, further biochemical analysis of the outer membrane will be required before more can be concluded.

Because LPS is such a potent stimulant, the roles of other components of the gram-negative cell wall in cellular activation have largely been ignored. Moreover, the study of these factors has always been hampered by LPS contamination in the preparations. The availability of this lpxA mutant should be a useful tool for the study of these cell wall components and the examination of their role in the activation of the acute inflammatory response during gram-negative infections.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI46613 (to R.R.I.), AI38515 (to R.R.I. and D.T.G.), and GM54060 (to D.T.G.).

REFERENCES

- 1.Aliprantis A O, Yang R B, Mark M R, Suggett S, Devaux B, Radolf J D, Klimpel G R, Godowski P, Zychlinsky A. Cell activation and apoptosis by bacterial lipoproteins through toll- like receptor-2. Science. 1999;285:736–739. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5428.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ball E D, Graziano R F, Shen L, Fanger M W. Monoclonal antibodies to novel myeloid antigens reveal human neutrophil heterogeneity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:5374–5378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.17.5374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belvin M P, Anderson K V. A conserved signaling pathway: the Drosophila toll-dorsal pathway. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1996;12:393–416. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brandtzaeg P, Bryn K, Kierulf P, Ovstebo R, Namork E, Aase B, Jantzen E. Meningococcal endotoxin in lethal septic shock plasma studied by gas chromatography, mass-spectrometry, ultracentrifugation, and electron microscopy. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:816–823. doi: 10.1172/JCI115660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brightbill H D, Libraty D H, Krutzik S R, Yang R B, Belisle J T, Bleharski J R, Maitland M, Norgard M V, Plevy S E, Smale S T, Brennan P J, Bloom B R, Godowski P J, Modlin R L. Host defense mechanisms triggered by microbial lipoproteins through toll-like receptors. Science. 1999;285:732–736. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5428.732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaudhary P M, Ferguson C, Nguyen V, Nguyen O, Massa H F, Eby M, Jasmin A, Trask B J, Hood L, Nelson P S. Cloning and characterization of two Toll/Interleukin-1 receptor-like genes TIL3 and TIL4: evidence for a multi-gene receptor family in humans. Blood. 1998;91:4020–4027. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chow J C, Young D W, Golenbock D T, Christ W J, Gusovsky F. Toll-like receptor-4 mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced signal transduction. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10689–10692. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christ W, Asano O, Robidoux A L, Perez M, Wang Y, Dubuc G R, Gavin W E, Hawkins L D, McGuinness P D, Mullarkey M A, Lewis M D, Kishi Y, Kawata T, Bristol J R, Rose J R, Rossignol D P, Kobayashi S, Hishinuma I, Kimura A, Asakawa N, Katayama K, Yamatsu I. E5531, a pure endotoxin antagonist of high potency. Science. 1995;268:80–83. doi: 10.1126/science.7701344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delude R L, Yoshimura A, Ingalls R R, Golenbock D T. Construction of a lipopolysaccharide reporter cell line and its use in identifying mutants defective in endotoxin, but not TNF-alpha, signal transduction. J Immunol. 1998;161:3001–3009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dziarski R, Tapping R I, Tobias P S. Binding of bacterial peptidoglycan to CD14. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:8680–8690. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.8680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Espevik T, Otterlei M, Skjak B G, Ryan L, Wright S D, Sundan A. The involvement of CD14 in stimulation of cytokine production by uronic acid polymers. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:255. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830230140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fearon D T, Locksley R M. The instructive role of innate immunity in the acquired immune response. Science. 1996;272:50–53. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5258.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flo T H, Halaas O, Lien E, Ryan L, Teti G, Golenbock D T, Sundan A, Espevik T. Human toll-like receptor 2 mediates monocyte activation by Listeria monocytogenes, but not by group B streptococci or lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 2000;164:2064–2069. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.4.2064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golenbock D T, Hampton R Y, Qureshi N, Takayama K, Raetz C R H. Lipid A-like molecules that antagonize the effects of endotoxins on human monocytes. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:19490–19498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupta D, Kirkland T N, Viriyakosol S, Dziarski R. CD14 is a cell-activating receptor for bacterial peptidoglycan. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:23310. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.38.23310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haziot A, Ferrero E, Kontgen F, Hijiya N, Yamamoto S, Silver J, Stewart C L, Goyert S M. Resistance to endotoxin shock and reduced dissemination of Gram-negative bacteria in CD14-deficient mice. Immunity. 1996;4:407–414. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80254-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haziot A, Ferrero E, Lin X Y, Stewart C L, Goyert S M. CD14-deficient mice are exquisitely insensitive to the effects of LPS. Prog Clin Biol Res. 1995;392:349–351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Haziot A A, Chen S, Ferrero E, Low M G, Silber R, Goyert S M. The monocyte differentiation antigen, CD14, is anchored to the cell membrane by a phosphatidylinositol linkage. J Immunol. 1988;141:547–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heine H, Kirschning C J, Lien E, Monks B G, Rothe M, Golenbock D T. Cutting edge: cells that carry A null allele for toll-like receptor 2 are capable of responding to endotoxin. J Immunol. 1999;162:6971–6975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hirschfeld M, Kirschning C J, Schwandner R, Wesche H, Weis J H, Wooten R M, Weis J J. Cutting edge: inflammatory signaling by Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins is mediated by toll-like receptor 2. J Immunol. 1999;163:2382–2386. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hoshino K, Takeuchi O, Kawai T, Sanjo H, Ogawa T, Takeda Y, Takeda K, Akira S. Cutting edge: Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4)-deficient mice are hyporesponsive to lipopolysaccharide: evidence for TLR4 as the Lps gene product. J Immunol. 1999;162:3749–3752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ingalls R R, Monks B G, Savedra R, Jr, Christ W J, Delude R L, Medvedev A E, Espevik T, Golenbock D T. CD11/CD18 and CD14 share a common lipid A signaling pathway. J Immunol. 1998;161:5413–5420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karow M, Fayet O, Georgopoulos C. The lethal phenotype caused by null mutations in the Escherichia coli htrB gene is suppressed by mutations in the accBC operon, encoding two subunits of acetyl coenzyme A carboxylase. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:7407–7418. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.22.7407-7418.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kirschning C J, Wesche H, Ayres T M, Rothe M. Human Toll-like receptor 2 confers responsiveness to bacterial lipopoysaccharide. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2091–2097. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kovach N L, Yee E, Munford R S, Raetz C R H, Harlan J H. Lipid IVA inhibits synthesis and release of tumor necrosis factor induced by lipopolysaccharide in human whole blood ex vivo. J Exp Med. 1990;172:77–84. doi: 10.1084/jem.172.1.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kusunoki T, Hailman E, Juan T S, Lichenstein H S, Wright S D. Molecules from Staphylococcus aureus that bind CD14 and stimulate innate immune responses. J Exp Med. 1995;182:1673–1682. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.6.1673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kusunoki T, Wright S D. Chemical characteristics of Staphylococcus aureus molecules that have CD14-dependent cell-stimulating activity. J Immunol. 1996;157:5112–5117. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lemaitre B, Nicolas E, Michaut L, Reichhart J M, Hoffmann J A. The dorsoventral regulatory gene cassette spatzle/Toll/cactus controls the potent antifungal response in Drosophila adults. Cell. 1996;86:973–983. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liabakk N B, Nustad K, Espevik T. A rapid and sensitive immunoassay for tumor necrosis factor using magnetic monodisperse polymer particles. J Immunol Methods. 1990;134:253–259. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(90)90387-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lien E, Means T K, Heine H, Yoshimura A, Kusumoto S, Fukase K, Fenton M J, Oikawa M, Qureshi N, Monks B, Finberg R W, Ingalls R R, Golenbock D T. Toll-like receptor 4 imparts ligand-specific recognition of bacterial lipopolysaccharide. J Clin Invest. 2000;105:497–504. doi: 10.1172/JCI8541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lien E, Sellati T J, Yoshimura A, Flo T H, Rawadi G, Finberg R W, Carroll J D, Espevik T, Ingalls R R, Radolf J D, Golenbock D T. Toll-like receptor 2 functions as a pattern recognition receptor for diverse bacterial products. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:33419–33425. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.47.33419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lynn W A, Raetz C R, Qureshi N, Golenbock D T. Lipopolysaccharide-induced stimulation of CD11b/CD18 expression on neutrophils. Evidence of specific receptor-based response and inhibition by lipid A-based antagonists. J Immunol. 1991;147:3072–3079. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Means T K, Wang S, Lien E, Yoshimura A, Golenbock D T, Fenton M J. Human toll-like receptors mediate cellular activation by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Immunol. 1999;163:3920–3927. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Medzhitov R, Janeway C A., Jr Innate immunity: the virtues of a nonclonal system of recognition. Cell. 1997;91:295–298. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80412-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Medzhitov R, Preston-Hurlburt P, Janeway C A., Jr A human homologue of the Drosophila Toll protein signals activation of adaptive immunity. Nature. 1997;388:394–397. doi: 10.1038/41131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Morisato D, Anderson K V. Signaling pathways that establish the dorsal-ventral pattern of the Drosophila embryo. Annu Rev Genet. 1995;29:371–399. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.29.120195.002103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Newman S L, Chaturvedi S, Klein B S. The WI-1 antigen of Blastomyces dermatitidis yeasts mediates binding to human macrophage CD11b/CD18 (CR3) and CD14. J Immunol. 1995;154:753–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Poltorak A, He X, Smirnova I, Liu M-Y, Van Huffel C, Du X, Birdwell D, Alejos A, Silva M, Galanos C, Freudenberg M, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Layton B, Beutler B. Defective LPS signaling in C3H/HeJ and C57BL/10ScCr mice: mutations in Tlr4 gene. Science. 1998;282:2085–2088. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poltorak A, Ricciardi-Castagnoli P, Citterio S, Beutler B. Physical contact between lipopolysaccharide and toll-like receptor 4 revealed by genetic complementation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:2163–2167. doi: 10.1073/pnas.040565397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Poltorak A, Smirnova I, He X, Liu M-Y, Van Huffel C, Birdwell D, Alejos A, Silva M, Du X, Thompson P, Chan E K L, Ledesma J, Roe B, Clifton S, Vogel S N, Beutler B. Genetic and physical mapping of the Lps locus: identification of the Toll-4 receptor as a candidate gene in the critical region. Blood Cells Molecules Dis. 1998;24:340–355. doi: 10.1006/bcmd.1998.0201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pugin J, Heumann D, Tomasz A, Kravchenko V V, Akamatsu Y, Nishijima M, Glauser M P, Tobias P S, Ulevitch R J. CD14 is a pattern recognition receptor. Immunity. 1994;1:509. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90093-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Qureshi S T, Lariviere L, Leveque G, Clermont S, Moore K J, Gros P, Malo D. Endotoxin-tolerant mice have mutations in Toll-like receptor 4 (Tlr4) J Exp Med. 1999;189:615–625. doi: 10.1084/jem.189.4.615. . (Erratum, 189:1518.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Raetz C R H. Biochemistry of endotoxins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1990;59:129–170. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.59.070190.001021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rock F L, Hardiman G, Timans J C, Kastelein R A, Bazan J F. A family of human receptors structurally related to Drosophila Toll. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:588–593. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.2.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rottem S. The effect of lipid A on the fluidity and permeability properties of phospholipid dispersions. FEBS Lett. 1978;95:121–124. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(78)80065-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rottem S, Markowitz O, Razin S. Thermal regulation of the fatty acid composition of lipopolysaccharides and phospholipids of Proteus mirabilis. Eur J Biochem. 1978;85:445–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1978.tb12258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Savedra R J, Delude R L, Ingalls R R, Fenton M J, Golenbock D T. Mycobacterial lipoarabinomannan recognition requires a receptor which shares components of the endotoxin signaling system. J Immunol. 1996;157:2549–2554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schwandner R, Dziarski R, Wesche H, Rothe M, Kirschning C J. Peptidoglycan- and lipoteichoic acid-induced cell activation is mediated by toll-like receptor 2. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:17406–17409. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.25.17406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sellati T J, Bouis D A, Kitchens R L, Darveau R P, Pugin J, Ulevitch R J, Gangloff S C, Goyert S M, Norgard M V, Radolf J D. Treponema pallidum and Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins and synthetic lipopeptides activate monocytic cells via a CD14-dependent pathway distinct from that used by lipopolysaccharide. J Immunol. 1998;160:5455–5464. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sen K, Nikaido H. Lipopolysaccharide structure required for in vitro trimerization of Escherichia coli OmpF porin. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:926–928. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.926-928.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soell M, Lett E, Holveck F, Scholler M, Wachsmann D, Klein J P. Activation of human monocytes by streptococcal rhamnose glucose polymers is mediated by CD14 antigen, and mannan binding protein inhibits TNF-alpha release. J Immunol. 1995;154:851–860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Steeghs L, Kuipers B, Hamstra H J, Kersten G, van Alphen L, van der Ley P. Immunogenicity of outer membrane proteins in a lipopolysaccharide-deficient mutant of Neisseria meningitidis: influence of adjuvants on the immune response. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4988–4993. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.10.4988-4993.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Steeghs L, den Hartog R, den Boer A, Zomer B, Roholl P, van der Ley P. Meningitis bacterium is viable without endotoxin. Nature. 1998;392:449–450. doi: 10.1038/33046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takayama K, Qureshi N, Beutler B, Kirkland T N. Diphosphoryl lipid A from Rhodopseudomonas sphaeroides ATCC 17023 blocks induction of cachectin in macrophages by lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1989;57:1336–1338. doi: 10.1128/iai.57.4.1336-1338.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Takeuchi O, Kaufmann A, Grote K, Kawai T, Hoshino K, Morr M, Muhlradt P F, Akira S. Cutting edge: preferentially the R-stereoisomer of the mycoplasmal lipopeptide macrophage-activating lipopeptide-2 activates immune cells through a toll-like receptor 2- and MyD88-dependent signaling pathway. J Immunol. 2000;164:554–557. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Weidemann B, Brade H, Rietschel E T, Dziarski R, Bazil V, Kusumoto S, Flad H D, Ulmer A J. Soluble peptidoglycan-induced monokine production can be blocked by anti-CD14 monoclonal antibodies and by lipid A partial structures. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4709. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.4709-4715.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Weidemann B, Schletter J, Dziarski R, Kusumoto S, Stelter E T R F, Flad H-D, Ulmer A J. Specific binding of soluble peptidoglycan and muramyldipeptide to CD14 on human monocytes. Infect Immun. 1997;65:858. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.3.858-864.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Williams M J, Rodriguez A, Kimbrell D A, Eldon E D. The 18-wheeler mutation reveals complex antibacterial gene regulation in Drosophila host defense. EMBO J. 1997;16:6120–6130. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.20.6120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wooten R M, Morrison T B, Weis J H, Wright S D, Thieringer R, Weis J J. The role of CD14 in signaling mediated by outer membrane lipoproteins of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Immunol. 1998;160:5485–5492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wright S D, Ramos R A, Tobias P S, Ulevitch R J, Mathison J C. CD14, a receptor for complexes of lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and LPS binding protein. Science. 1990;249:1431–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.1698311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yang R-B, Mark M R, Gray A, Huang A, Xie M H, Zhang M, Goddard A, Wood W I, Gurney A L, Godowski P J. Toll-like receptor-2 mediates lipopolysaccharide-induced cellular signalling. Nature. 1998;395:284–288. doi: 10.1038/26239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yoshimura A, Lien E, Ingalls R R, Tuomanen E, Dziarski R, Golenbock D. Recognition of gram-positive bacterial cell wall components by the innate immune system occurs via toll-like receptor 2. J Immunol. 1999;163:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ziegler-Heitbrock H W, Ulevitch R J. CD14: cell surface receptor and differentiation marker. Immunol Today. 1993;14:121–125. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(93)90212-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]