Abstract

Campylobacter fetus bacteria, isolated from both mammals and reptiles, may be either subsp. fetus or subsp. venerealis and either serotype A or serotype B. Surface layer proteins, expressed and secreted by genes in the sap locus, play an important role in C. fetus virulence. To assess whether the sap locus represents a pathogenicity island and to gain further insights into C. fetus evolution, we examined several C. fetus genes in 18 isolates. All of the isolates had 5 to 9 sapA or sapB homologs. One strain (85-387) possessed both sapA and sapB homologs, suggesting a recombinational event in the sap locus between sapA and sapB strains. When we amplified and analyzed nucleotide sequences from portions of housekeeping gene recA (501 bp) and sapD (450 bp), a part of the 6-kb sap invertible element, the phylogenies of the genes were highly parallel. Among the 15 isolates from mammals, serotype A and serotype B strains generally had consistent positions. The fact that the serotype A C. fetus subsp. fetus and subsp. venerealis strains were on the same branch suggests that their differentiation occurred after the type A-type B split. Isolates from mammals and reptiles formed two distinct tight phylogenetic clusters that were well separated. Sequence analysis of 16S rRNA showed that the reptile strains form a distinct phylotype between mammalian C. fetus and Campylobacter hyointestinalis. The phylogenies and sequence results showing that sapD and recA have similar G + C contents and substitution rates suggest that the sap locus is not a pathogenicity island but rather is an ancient constituent of the C. fetus genome, integral to its biology.

Members of the genus Campylobacter are microaerophilic, nonfermentative bacteria, of which Campylobacter fetus is the type species (40). C. fetus has been isolated from a wide range of hosts, including cattle, sheep, other ungulates, swine, humans, poultry, and reptiles (41). C. fetus causes infertility and infectious abortion in sheep and cattle and may cause both diarrheal and extraintestinal infections in human hosts (3, 21, 39, 40, 43). The species C. fetus is currently subdivided into C. fetus subsp. fetus and C. fetus subsp. venerealis, based on their habitats, biological properties, and genome sizes and the diseases they produce (22, 28, 38, 40, 43).

C. fetus strains are either serotype A or serotype B (13, 30, 35). C. fetus subsp. venerealis strains are serotype A, whereas C. fetus subsp. fetus cells may be either serotype A or serotype B (30, 35). These serotypes are associated with differences in both lipopolysaccharide (LPS) structure and type of surface layer protein (SLP) (13, 20, 30, 33–35, 48). The C. fetus SLPs, which act as capsules to resist C3b binding and undergo antigenic variation to protect against antibody-mediated opsonization, are important virulence factors allowing both persistence and systemic infection (5, 6, 8, 10, 11, 29, 32, 47). Our previous studies have shown that the SLPs produced by strains isolated from reptiles (see below) are antigenically cross-reactive with SLPs isolated from mammals (46), and a reptile strain was found to be the cause of an acute diarrheal illness in a child (24). This observation suggests that reptile strains produce SLPs that also serve as important virulence factors, similar to those for the SLPs from strains isolated from mammals. C. fetus cells possess a unique sap promoter that allows expression of the full complement of sap homologs that encode these SLPs (9, 45). The sap locus (including all the sap homologs, the sap promoter, and sapC, -D, -E, and -F on an invertible element) is tightly clustered on the C. fetus chromosome in a region of <93 kb, representing <8% of the genome (9, 44, 45).

In this study, we investigated the evolutionary relationships between the two C. fetus subspecies among strains originating from different hosts. We hypothesized that the sap locus might represent a pathogenicity island (23) which entered the C. fetus genome after the species was formed. To test this hypothesis, we compared sapD, a gene that is conserved in the invertible sap element (44), and recA, a widely conserved housekeeping gene (16). Based on differences observed in these phylogenetic analyses, we examined the 16S rRNA genes of six C. fetus strains to better understand the position of C. fetus in relation to other Campylobacter spp.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains.

The 18 C. fetus strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. Three isolates were C. fetus subsp. venerealis. The other 15 isolates were C. fetus subsp. fetus; 9 were serogroup A (6 mammal and 3 reptile) and 6 were serogroup B. The three reptile strains were isolated from turtles after one had been found to be the cause of an acute diarrheal illness in a child (24). Strains 99-256 (ATCC 33561) and 99-257 (ATCC 19438) are from the American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va.; the other 16 strains had been collected and identified as C. fetus in the Vanderbilt University Campylobacter laboratory using standard criteria (9, 18, 21, 40).

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the C. fetus strain studied

| Strain no. (in Fig. 1–3) | Strain designation | C. fetus subspecies | Animal source (site) | Serotypea | sap typeb | Major SLP (kDa)c | No. of sap homologs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 80-109 | fetus | Human (blood) | A | A | 127 | 8 |

| 2 | 82-40 | fetus | Human (blood) | A | A | 97 | 8 |

| 3 | 83-94 | fetus | Human (NA) | NA | A | 97 | 5 |

| 4 | 84-32d | fetus | Bovine (vagina) | A | A | 97 | 8 |

| 5 | 84-86 | fetus | Human (blood) | A | A | 97 | 8 |

| 6 | 84-92 | fetus | Bovine (feces) | A | A | 97 | 7 |

| 7 | 85-388 | fetus | Reptile (feces) | A | A | 97 | 9 |

| 8 | 85-389 | fetus | Reptile (feces) | A | A | 149 | 8 |

| 9 | 84-112 | venerealis | Bovine (genital) | A | A | 149 | 8 |

| 10 | 99-256 | venerealis | Bovine (vagina) | NA | A | 97 | 8 |

| 11 | 99-257 | venerealis | Human (blood) | NA | A | 97 | 7 |

| 12 | 85-387 | fetus | Reptile (feces) | NA | A/B | 97 | 8 |

| 13 | 84-87 | fetus | Human (blood) | B | B | 97 | 8 |

| 14 | 84-90 | fetus | Bovine (feces) | B | B | ND | 7 |

| 15 | 84-91 | fetus | Human (blood) | B | B | 97 | 8 |

| 16 | 84-94 | fetus | Human (blood) | B | B | 127 | 8 |

| 17 | 84-104 | fetus | Monkey (blood) | B | B | 97 | 7 |

| 18 | 84-107 | fetus | Human (blood) | B | B | 97 | 7 |

Immunoblot assay.

C. fetus cells were harvested from 48-h plate cultures, protein concentrations were assayed using the Pierce bicinchoninic acid protein reagent assay (Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, Ill.), and 1-μg protein samples were assayed by electrophoresis on a 7% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel. S-layer proteins were detected with polyclonal rabbit serum (1:10,000 dilution) against the C. fetus strain 82-40LP 97-kDa SLP, as described previously (33). The secondary antibody (1:2,000 dilution) was goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G–alkaline phosphatase (Boehringer Mannheim Biochemicals, Indianapolis, Ind.).

PCR.

The PCR primers used in this study are listed in Table 2. To determine whether a strain was a sapA or sapB type, chromosomal DNA from the selected strains was amplified with SAF01 and SAR01 or with SBF01 and SBR01, respectively. To amplify recA or sapD, the primers RAF01 and RAR01 or SDF01 and SD01, respectively, were used. The 16S rRNA cistrons were amplified with bacterial universal primers F24 and F25. The products of PCR amplification were examined by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels. DNA was stained with ethidium bromide and visualized under short-wavelength UV light.

TABLE 2.

PCR and sequencing primers

| Primer designation | Gene | Position | Orientation | Sequence (5′→3′)a |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F24 | 16S rRNA | 9–27 | Forward | AGTTTGATYMTGGCTCAG |

| F22 | 16S rRNA | 344–358 | Reverse | RCTGCTGCCTCCCGT |

| F23 | 16S rRNA | 344–359 | Forward | ACGGGAGGCAGCAGY |

| F15 | 16S rRNA | 519–533 | Reverse | TTACCGCGGCTGCTG |

| F16 | 16S rRNA | 789–806 | Forward | TAGATACCCYGGTAGTCC |

| F17 | 16S rRNA | 907–926 | Reverse | CCGTCWATTCMTTTGAGTTT |

| F18 | 16S rRNA | 1099–1113 | Forward | GCAACGAGCGCAACC |

| F20 | 16S rRNA | 1226–1242 | Reverse | CCATTGTARCACGTGTG |

| F25 | 16S rRNA | 1525–1541 | Reverse | AAGGAGGTGWTCCARCC |

| SAF01 | sapA | 0–19 | Forward | ATGTTAAACAAAACAGATGT |

| SAR01 | sapA | 513–531 | Reverse | ATCAAGATCACTAGCACTA |

| SBF01 | sapB | 19–40 | Forward | TTCAGAGCTATTTATAGTTC |

| SBR01 | sapB | 504–524 | Reverse | TCAACACTACTACTATTACTA |

| RAF01 | recA | 12–41 | Forward | ATAAGAAAAAAAGCCTAGACC |

| RAR01 | recA | 607–625 | Reverse | TAGTTTCAGGAGTGCCATA |

| SDF01 | sapD | 825–844 | Forward | AGCTGGATCAATACTATTAG |

| SDR01 | sapD | 1348–1367 | Reverse | CCGTCCGGAAGTCTTAG |

R = A or G; M = A or C; W = A or T; Y = C or T.

Southern hybridization.

C. fetus chromosomal DNA was prepared using the Wizard genomic DNA purification kit (Promega, Madison, Wisc.), digested with HindIII, electrophoresed on a 0.7% agarose gel, and transferred to a nylon membrane (MSI, Westborough, Mass.). The membranes were hybridized with DNA probes labeled using the Renaissance nonradioactive chemiluminescence kit supplied by NEN Research Products (Boston, Mass.). The probes were the PCR products specific for either the sapA 5′ conserved region, which was amplified using primers SAF01 and SAR01, or for the sapB 5′ conserved region, which was amplified using primers SBF01 and SBR01 (Table 2).

Sequencing.

After the 501-bp recA fragments, the 450-bp sapD fragments, and the 16S rRNA cistrons were amplified, the PCR products were purified using the QiaQuik PCR purification kit (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, Calif.). Purified DNA from PCR was sequenced using an ABI prime cycle-sequencing kit (BigDye terminator cycle sequencing kit with AmpliTaq DNA polymerase FS; The Perkin-Elmer Corp., Norwalk, Conn.), and reactions were run on an ABI 377 DNA sequencer. The recA and sapD sequences were determined on both strands using the same primers used for their PCR amplification. For 16S rRNA sequencing, primers F15-F18, F20, and F22-F25 (Table 2) were used.

Data analysis.

Multiple nucleotide alignments were created using the Genetics Computer Group (GCG) program (Wisconsin Package version 9.1; GCG, Madison, Wisc.). Phylograms based on recA and sapD nucleotide sequences were generated using both parsimony and distance matrix methods, using PAUP 4.0b2, and the phylograms were displayed using Treeview and PAUP 3.1 (D. L. Swofford. 1993. PAUP: phylogenetic analysis using parsimony, version 3.1. Illinois Natural Survey, Champaign, Ill.) 16S rRNA sequence data were entered into RNA, a program for data entry, editing, sequence alignment, secondary structure comparison, similarity matrix generation, and dendrogram construction for 16S rRNA, written in Microsoft QuickBasic for use with PC computers, and were aligned as previously described (31). The 16S database contains over 1,000 sequences obtained at the Forsythe laboratory and over 500 obtained from GenBank (27). Similarity matrices were constructed from the aligned sequences by using only those sequence positions for which 90% of the strains had data. The similarity matrices were corrected for multiple base changes at single positions by the method of Jukes and Cantor (26). Phylogenetic trees were constructed using the neighbor-joining method of Saitou and Nei (37).

RESULTS

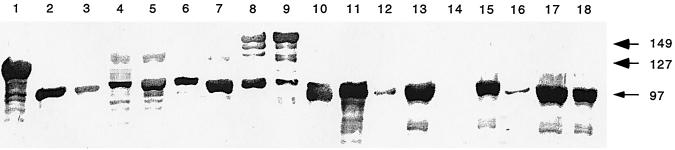

Characterization of the C. fetus S-layer proteins.

To characterize the 18 C. fetus strains in terms of their SLP expression, we performed immunoblotting with polyclonal antiserum raised to the 97-kDa S-layer protein from type A strain 82-40LP (46). These immunoblots indicated that the wild-type C. fetus strains contain different high-mass SLPs ranging from 97 to 149 kDa, as expected (Table 1 and Fig. 1). One type B strain (84-90) is SLP−, which may reflect in vitro deletion of the secretion apparatus and unique promoter, as has been described for type A strains (45).

FIG. 1.

Identification of SLP in whole-cell preparations of 18 C. fetus strains by immunoblotting with polyclonal rabbit serum against the 97-kDa SLP from type A C. fetus strain 82-40. See Table 1 for strain characteristics. The lane numbers representing the strains correspond to the “strain numbers” in Table 1.

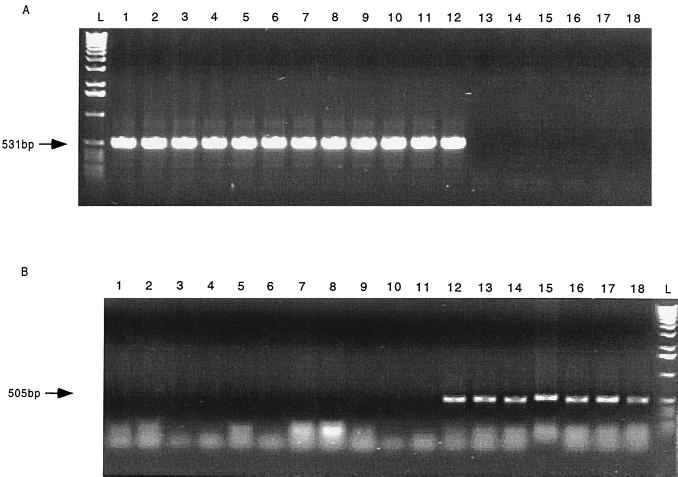

Typing of strains.

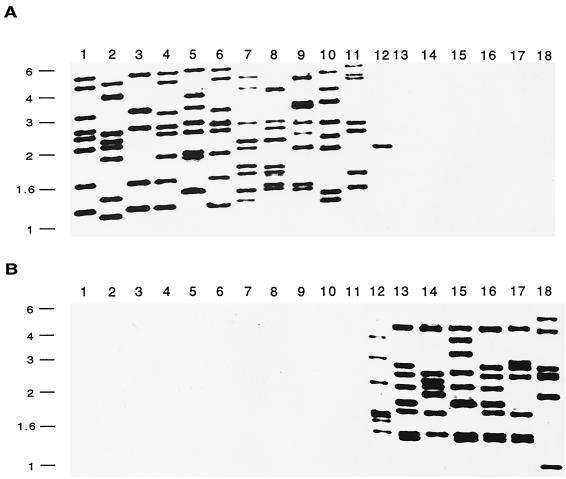

All C. fetus strains possess either sapA or sapB homologs (13), and each of the two families (sapA and sapB) of homologs share a unique 552-bp sequence that makes up their 5′-conserved regions (13). PCR, using primers based on the sapA and sapB 5′-conserved regions (7, 13), showed that 6 of the 18 strains are sapA types, 11 are sapB types, and strain 85-387, isolated from a turtle, has both types (Table 1; Fig. 2). Southern hybridization, using the sapA and sapB 5′-conserved regions as the type-specific probes (Fig. 2), confirmed the results of PCR, and it also showed that there are 5 to 9 sap homologs in each of the 18 strains studied (Table 1 and Fig. 3). Strain 85-387 possesses seven sapB homologs and one sapA homolog, thus representing an A/B chimera.

FIG. 2.

PCR to detect the sap type of the 18 C. fetus strains by using 5′-conserved-region primers from sapA (panel A) or sapB (panel B). L represents the 1-kb ladder. See Table 1 for strain characteristics. (The lane numbers correspond to the strain numbers in Table 1.)

FIG. 3.

Southern hybridization of HindIII digestions of chromosomal DNA from 18 C. fetus strains with probes to the 5′-sapA (panel A) or -sapB (panel B)-conserved regions. See Table 1 for strain characteristics. (The lane numbers correspond to the strain numbers shown in Table 1.) The positions of molecular size markers (in kilobases) are indicated to the left of each panel.

Patterns of divergence between strains.

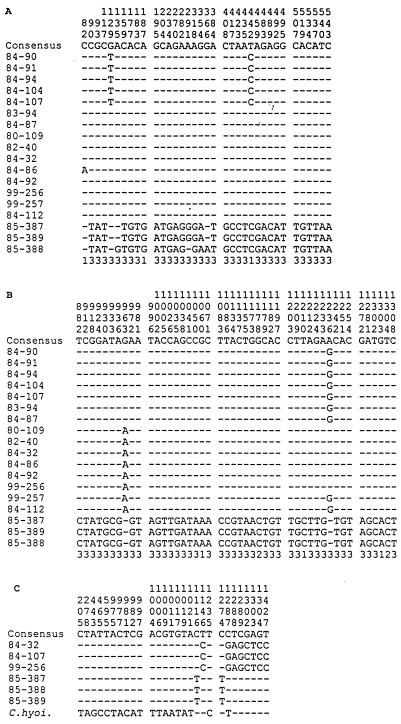

The polymorphic sites within recA and sapD of the 18 C. fetus strains and the 16S rRNA of the six C. fetus strains studied are shown in Fig. 4. There were 36 polymorphic sites within the 501 bp of recA that were sequenced in all 18 strains (Fig. 4A). Only 36 sites were polymorphic, and the overall substitution rate was 0.10. Synonymous substitutions predominated, with Ka/Ks = 0.01, where Ka is the nonsynonymous substitution rate and Ks is the synonymous substitution rate. Within the 450 bp of sapD (Fig. 4B), there were 46 sites showing any polymorphism, and the overall substitution rate was 0.17. Synonymous substitutions also predominated, with Ka/Ks = 0.03. The mean (plus or minus the standard deviation) G + C content of the 18 recA sequences was 40.8% ± 0.3%, similar to the 40.6% ± 0.3% content of the 18 sapD sequences.

FIG. 4.

Polymorphic sites within the recA (panel A), sapD (panel B), and 16S rRNA (panel C) gene sequences. Numbering (vertical format) of the polymorphic sites of recA and sapD is from the first base position of each gene. The numbering of 16S rRNA sequences corresponds to the base positions of E. coli. For panels A and B, the position of the site within the codon is shown below. Nearly all (90.2%) of the 82 polymorphic sites for recA and sapD are in the third codon position.

In six C. fetus strains studied, there were 28 polymorphic sites in essentially complete 16S rRNA sequences (bases 28 to 1524 using the Escherichia coli numbering) compared with Campylobacter hyointestinalis, a species similar to C. fetus (Fig. 4C). The 16S rRNA sequences from sapA strain 84-32, sapB strain 84-107, and C. fetus subsp. venerealis 99-256 were identical. The three reptile strains showed identical 16S rRNA sequences, but they differed from the other C. fetus strains by 10 bases and from C. hyointestinalis by 19 bases.

Phylogenetic relationships inferred from recA, sapD, and 16S rRNA.

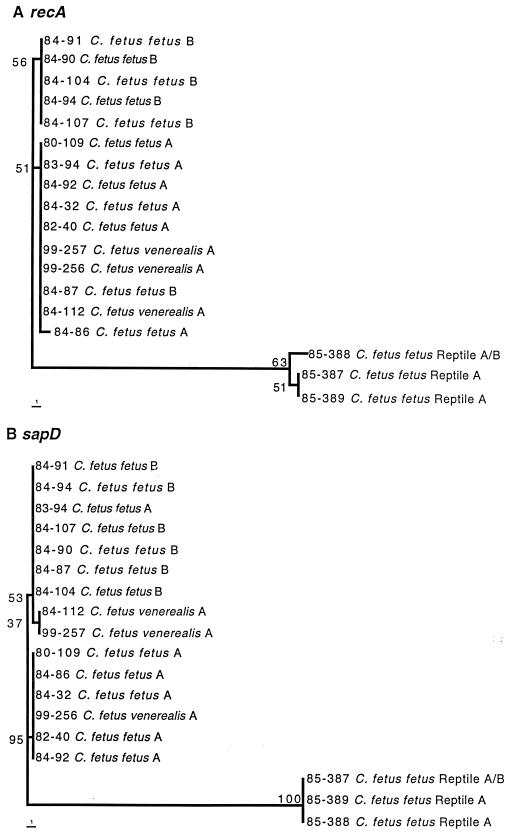

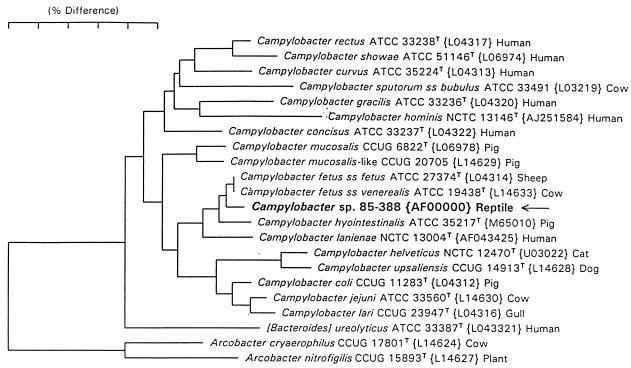

The phylogeny of recA (Fig. 5A) showed that the isolates from mammals and reptiles formed two tight clusters that were far removed from each other. Among the isolates from mammals, the major distinction was between the serotype A and serotype B strains, but there were only two nucleotide differences (Fig. 4). The only exception, strain 84-87, a type B strain, was identical to the type A consensus sequence. The type A C. fetus subsp. fetus and subsp. venerealis strains are on the same branch, suggesting that their differentiation occurred after the type A-type B split. The phylogeny of sapD is almost identical to that for recA, with only one or two nucleotide differences between type A and type B mammalian strains. Strain 83-94 (type A) was the exception, with a type B sapD sequence (Fig. 5B). The dendrograms for 16S rRNA (Fig. 6) indicated that the reptile strains (as exemplified by strain 85-388) appear to form a distinct phylotype between C. fetus and C. hyointestinalis.

FIG. 5.

Phylogenetic trees constructed from the nucleotide sequences of recA (panel A) and sapD (panel B) using the PAUP 4.0b2 neighbor-joining method, based on Kimura's two-parameter model distance matrices. Bootstrap values (based on 500 replicates) are represented at each node, and the branch length index is represented below each tree.

FIG. 6.

Phylogenetic tree showing the placement of strains isolated from reptiles (based on strain 85-388) on the basis of 16S rRNA sequence data analysis. The scale bar represents a 5% difference in nucleotide sequence, as determined by measuring the lengths of the horizontal lines connecting any two species. The positions of mammalian C. fetus are all identical whether subsp. fetus or venerealis or type A or type B, but the three strains isolated from reptiles occupy a different position.

DISCUSSION

C. fetus strains have been characterized on the basis of the source from which they were isolated, the biochemical properties defining the subspecies, and their serotype, but the work reported here indicated that the most fundamental difference among C. fetus strains is reflected by whether they were isolated from a mammal or a reptile. Using PCR, Southern hybridization, and LPS typing, the three reptile strains were shown to be type A, and earlier studies showed that reptile strains produced SLPs that are antigenically cross-reactive with SLPs in mammals (46). However, based on the recA, sapD, and 16S rRNA sequences, the reptile isolates are highly different from the C. fetus strains isolated from mammals. The reptile strains appear to form a distinct phylotype of C. fetus, but for each of the three genes studied, sequence differences of the magnitude found could indicate that they represent different species or different subspecies. The taxonomic relatedness of the reptilian, and mammalian C. fetus isolates may be resolved by additional studies, although the decision about whether to separate them into different species may be arbitrary.

The sequence data in this study were consistent with the hypothesis that C. fetus is an ancient organism once carried by an ancestral vertebrate host. According to this hypothesis, the ancestral host carried an ancestral C. fetus strain and, as that host evolved to differentiate into reptiles or mammals, the C. fetus strains carried by the host continued to evolve but in isolation from each other. The deep differences within common loci between C. fetus strains isolated from mammals and reptiles suggest that their last common ancestor may have lived before these animals diverged, approximately 200 million years ago. However, the data do not completely rule out the alternative possibility that C. fetus was acquired after mammals and reptiles diverged and that its presence in the two types of hosts reflects interspecies (horizontal) transmission.

The source of isolates, genome size, and the degree of tolerance to glycine have been the major differentiating features between C. fetus subsp. fetus and C. fetus subsp. venerealis (21, 38, 39, 41). C. fetus subsp. fetus causes sporadic epizootic abortion in cattle and sheep and is involved in human infections, producing both acute intestinal illness and systemic diseases (5). C. fetus subsp. fetus strains have been isolated from many animal species, including cattle, sheep, other ungulates, poultry, swine, and reptiles (40). In contrast, strains of C. fetus subsp. venerealis cause enzootic infertility in cattle and rarely have been associated with human infections (38). The genome sizes of C. fetus subsp. fetus and C. fetus subsp. venerealis are 1.1 Mb and 1.3 Mb, respectively (38). Although classically C. fetus subsp. fetus strains but not C. fetus subsp. venerealis strains tolerate more than 1% glycine, such results are not easily reproducible (21, 41). The two subspecies cannot be differentiated on the basis of serotype (35), SLP type (13, 48), fluorescent-antibody assay (28), fatty acid content (4), or DNA-DNA homology studies (1). All subsp. venerealis isolates are LPS type A, whereas subsp. fetus may be type A or B (30, 35). The observation that subsp. venerealis strains could not be distinguished from type A mammalian subsp. fetus strains on the basis of sapD, recA, and 16S rRNA sequences indicates that these organisms are very closely related. If they are not identical, their differentiation must have been relatively recent.

C. fetus cells may exist as either of two defined serogroups (type A or type B) based on their LPS composition (13, 30, 35). The LPS types, defined structurally and antigenically (30, 35), are consistent with the C. fetus serotyping scheme developed more than 30 years ago (2). Reattachment of native SLP and the recombinant sapA and sapB products to cells of the homologous LPS type, but not to the heterologous LPS type, has indicated that the conserved sapA- and sapB-encoded N termini are critical for LPS-binding specificity (13, 48). Thus, the serotype (A or B), LPS type (A or B), and SLP type (A or B) of a C. fetus strain are consistent with one another. Among C. fetus isolates from mammals, the most significant phylogenetic dichotomy is between type A and B strains, as indicated by both sapD and recA analyses.

Using PCR and Southern hybridizations based on the sapA and sapB 5′-conserved regions, we found 5 to 9 sap homologs in each strain. Each strain shows a different sap profile, which is due to DNA rearrangements in the sap locus (15, 16, 36; Z.-C. Tu, K. C. Ray, S. A. Thompson, and M. J. Blaser, submitted for publication). Surprisingly, we found one (reptile) strain (85-387) with one sapA and seven sapB homologs. The coexistence of sapA and sapB homologs in the same strain provides, for the first time, evidence of intraspecies recombination involving the C. fetus sap locus. Although considerable horizontal interspecies and intraspecies gene transfer has occurred in prokaryotes (17, 19, 25, 42), how this might occur in C. fetus cells that have an S layer and are not naturally competent is not immediately apparent. The dichotomy between type A and type B strains involves both LPS structure (30, 35) and SLP sequence and structure (33, 48) and thus involves differences in at least two different genetic loci. The occurrence of recombination might explain why the type A-B dichotomy is not perfectly reproduced in the sapD and recA phylogenies (Fig. 5).

The finding that the sap genes are critical for C. fetus virulence and that pulse-field gel electrophoresis studies indicate that these genes are clustered on the chromosome (12) suggests the possibility that the genes exist as a single locus representing a “pathogenicity island” (23). Mapping studies indicate that most if not all of the genes are contiguous (14; Z.-C. Tu and M. J. Blaser, unpublished data). Pathogenicity islands have entered bacterial genomes after their development as particular species, and consequently markers of their evolution and phylogeny differ from those of “housekeeping” genes (23). However, the conservation of sapD and the sapA homologs in all C. fetus strains and the similar G + C content, substitution rate, and phylogeny in relation to recA suggest that the sap locus is not a pathogenicity island but represents an ancient and highly conserved constituent of the C. fetus genome. The striking sequence identity between sapA and sapB (13) further supports a highly conserved function in the sap locus. Our previous studies have shown that sap DNA inversion plays an important role in C. fetus virulence via high-frequency RecA-dependent (16) and low-frequency RecA-independent mechanisms (36); this redundancy of mechanisms indicates the importance of sap inversion to C. fetus. In total, both the earlier and present data suggest that C. fetus is an ancient organism whose highly conserved features permit maintenance of its niche(s) on mucosal surfaces of vertebrate hosts.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

This research was supported in part by grant R01 A124145 from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Basden E H, II, Tourtellotte M E, Plastridge W N, Tucker J S. Genetic relationship among bacteria classified as vibrios. J Bacteriol. 1968;95:439–443. doi: 10.1128/jb.95.2.439-443.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berg R L, Jutila J W, Firehammer B D. A revised classification of Vibrio fetus. Am J Vet Res. 1971;32:11–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Blaser M J. Campylobacter fetus—emerging infection and model system for bacterial pathogenesis at mucosal surfaces. Clin Infect Dis. 1998;27:256–258. doi: 10.1086/514655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blaser M J, Moss C M, Weaver R E. Cellular fatty acid composition of Campylobacter fetus. J Clin Microbiol. 1980;11:448–451. doi: 10.1128/jcm.11.5.448-451.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blaser M J, Smith P F, Hopkins J A, Heinzer I, Bryner J H, Wang W L. Pathogenesis of Campylobacter fetus infections: serum resistance associated with high-molecular-weight surface proteins. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:696–706. doi: 10.1093/infdis/155.4.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blaser M J, Smith P F, Repine J E, Joiner K A. Pathogenesis of Campylobacter fetus infections: failure of encapsulated Campylobacter fetus to bind C3b explains serum and phagocytosis resistance. J Clin Investig. 1988;81:1434–1444. doi: 10.1172/JCI113474. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blaser M J, Gotschlich E C. Surface array protein of Campylobacter fetus. Cloning and gene structure. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:14529–14535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blaser M J, Pei Z. Pathogenesis of Campylobacter fetus infections: critical role of the high molecular weight S-layer proteins in virulence. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:696–706. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.2.372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blaser M J, Wang E, Tummuru M K, Washburn R, Fujimoto S, Labigne A. High frequency S-layer protein variation in Campylobacter fetus revealed by sapA mutagenesis. Mol Microbiol. 1994;14:453–462. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb02180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dubreuil J D, Logan S M, Cubbage S, Eidhin D N, McCubbin W D, Kay C M, Beveridge T J, Ferris F G, Trust T J. Structural and biochemical analyses of a surface array protein of Campylobacter fetus. J Bacteriol. 1988;170:4165–4173. doi: 10.1128/jb.170.9.4165-4173.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dubreuil J D, Kostrzynska M, Austin J W, Trust T J. Antigenic differences among Campylobacter fetus S-layer proteins. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5035–5043. doi: 10.1128/jb.172.9.5035-5043.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dworkin J, Tummuru M K, Blaser M J. A lipopolysaccharide-binding domain of the Campylobacter fetus S-layer protein resides within the conserved N terminus of a family of silent and divergent homologs. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:1734–1741. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.7.1734-1741.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dworkin J, Tummuru M K, Blaser M J. Segmental conservation of sapA sequences in type B Campylobacter fetus cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:15093–15101. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.25.15093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dworkin J, Blaser M J. Nested DNA inversion as a paradigm of programmed gene rearrangement. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:985–990. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.3.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dworkin J, Blaser M J. Molecular mechanisms of Campylobacter fetus surface layer protein expression. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:433–440. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6151958.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dworkin J, Shedd O L, Blaser M J. Nested DNA inversion of Campylobacter fetus S-layer genes is recA dependent. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:7523–7529. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7523-7529.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dykhuizen D E, Green L. Recombination in Escherichia coli and the definition of biological species. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:7257–7268. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.22.7257-7268.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elazhary M. An assay of isolation and identification for some animal Vibrio fetus. Am J Vet Res. 1968;32:649–653. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Feil E, Zhou J J, Smith J M, Spratt G G. A comparison of the nucleotide sequences of the adk and recA genes of pathogenic and commensal Neisseria species: evidence for extensive interspecies recombination within adk. J Mol Evol. 1996;43:631–640. doi: 10.1007/BF02202111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fogg G C, Yang L Y, Wang E, Blaser M J. Surface array proteins of Campylobacter fetus block lectin-mediated binding to type A lipopolysaccharide. Infect Immun. 1990;58:2738–2744. doi: 10.1128/iai.58.9.2738-2744.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garcia M M, Eaglesome M D, Rigby C. Campylobacters important in veterinary medicine. Vet Bull. 1983;53:793–818. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grogono-Thomas R, Dworkin J, Blaser M J, Newell D G. Roles of the surface layer proteins of Campylobacter fetus subsp. fetus in ovine abortion. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1687–1691. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.3.1687-1691.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hacker J, Blum-Oehler G, Muhldorfer I, Tschape H. Pathogenicity islands of virulent bacteria: structure, function and impact on microbial evolution. Mol Microbiol. 1997;23:1089–1097. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3101672.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harvey S, Greenwood M C. Isolation of Campylobacter fetus from a pet turtle. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;21:260–261. doi: 10.1128/jcm.21.2.260-261.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jain R, Rivera M C, Lake J A. Horizontal gene transfer among genomes: the complexity hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:3801–3806. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jukes T H, Cantor C R. Evolution of protein molecules. In: Munro H N, editor. Mammalian protein metabolism. Vol. 3. New York, N.Y: Academic Press, Inc.; 1969. pp. 21–132. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maidak B L, Cole J R, Lilbum T G, Parker C T, Jr, Saxman P R, Stredwick J M, Garrity G M, Li B, Olsen G J, Pramanik S R, Schmidt T M, Tiedje J M. A new version of the RDP (Ribosomal Database Project) Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:173–174. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Marsh H, Firehammer B D. Serological relationships of twenty-three ovine and three bovine strains of Vibrio fetus. Am J Vet Res. 1953;14:396–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCoy E C, Doyle D, Burda K, Corbeil L B, Winter A J. Superficial antigens of Campylobacter (Vibrio) fetus: characterization of an antiphagocytic component. Infect Immun. 1975;11:517–525. doi: 10.1128/iai.11.3.517-525.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moran A P, O'Malley D T, Kosunen T U, Helander I M. Biochemical characterization of Campylobacter fetus lipopolysaccharides. Infect Immun. 1994;62:3922–3929. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.9.3922-3929.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paster B J, Dewhirst F E. Phylogeny of campylobacters, wolinellas, Bacteroides gracilis, and Bacteroides ureolyticus by 16S ribosomal ribonucleic acid sequencing. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1988;38:56–62. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pei Z, Blaser M J. Pathogenesis of Campylobacter fetus infections: role of surface array proteins in virulence in a mouse model. J Clin Investig. 1990;85:1036–1043. doi: 10.1172/JCI114533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pei Z R, Ellison T D, Lewis R V, Blaser M J. Purification and characterization of a family of high molecular weight surface-array proteins from Campylobacter fetus. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:6414–6420. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pérez-Pérez G I, Blaser M J. Lipopolysaccharide characteristics of pathogenic campylobacters. Infect Immun. 1985;47:353–359. doi: 10.1128/iai.47.2.353-359.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pérez-Pérez G I, Blaser M J, Bryner J H. Lipopolysaccharide structures of Campylobacter fetus are related to heat-stable serogroups. Infect Immun. 1986;51:209–212. doi: 10.21236/ada265573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ray K C, Tu Z C, Grogono-Thomas R, Newell D G, Thompson S A, Blaser M J. Campylobacter fetus sap inversion occurs in the absence of RecA function. Infect Immun. 2000;68:5663–5667. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.10.5663-5667.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Saitou N, Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salama S M, Garcia M M, Taylor D E. Differentiation of the subspecies of Campylobacter fetus by genomic sizing. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:446–450. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-3-446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Skirrow M B. Campylobacter and Helicobacter infections of man and animals. In: Parker M T, Collier L H, editors. Principles of bacteriology, virology and immunity. 8th ed. Vol. 2. London, England: Edward Arnold; 1990. pp. 531–545. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Smibert R M. The genus Campylobacter. In: Star M P, Stolp H, Truper H G, Balows A, Schlegel H G, editors. The prokaryotes: a handbook on habitats, isolation, and identification of bacteria. New York, N.Y: Springer-Verlag; 1981. pp. 609–617. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Smibert R M. Genus Campylobacter. In: Krieg N R, Holt H G, editors. Bergey's manual of systemic bacteriology. Vol. 1. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Wilkins Co.; 1984. pp. 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Smith N H, Holmes E C, Donovan G M, Carpenter G A, Spratt B G. Networks and groups within the genus Neisseria: analysis of argF, recA, rho, and 16S rRNA sequences from human Neisseria species. Mol Biol Evol. 1999;16:773–783. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a026162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thompson S A, Blaser M J. Pathogenesis of Campylobacter fetus infections. In: Nachamkin I, Blaser M J, editors. Campylobacter. 2nd ed. Washington, D.C.: American Society for Microbiology; 2000. pp. 321–347. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thompson S A, Shedd O L, Ray K C, Beings M H, Jorgensen J P, Blaser M J. Campylobacter fetus surface layer proteins are transported by a type I secretion system. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6450–6458. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.24.6450-6458.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tummuru M K, Blaser M J. Characterization of the Campylobacter fetus sapA promoter: evidence that the sapA promoter is deleted in spontaneous mutant strains. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:5916–5922. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.18.5916-5922.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang E, Garcia M M, Blake M S, Pei Z H, Blaser M J. Shift in S-layer protein expression responsible for antigenic variation in Campylobacter fetus J. Bacteriol. 1993;175:4979–4984. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.16.4979-4984.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Winter A J, McCoy E C, Fullmer C S, Burda K, Bier P J. Microcapsule of Campylobacter fetus: chemical and physical characterization. Infect Immun. 1978;22:963–971. doi: 10.1128/iai.22.3.963-971.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang L Y, Pei Z H, Fujimoto S, Blaser M J. Reattachment of surface array proteins to Campylobacter fetus cells. J Bacteriol. 1992;174:1258–1267. doi: 10.1128/jb.174.4.1258-1267.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]