Abstract

Trypanosoma cruzi, the causative agent of Chagas' disease, is known to be susceptible to nitric oxide (NO)-dependent killing by gamma interferon-activated macrophages. Mice deficient for inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) are highly susceptible to T. cruzi, and inhibition of iNOS from the beginning of infection was reported to lead to an increase in trypomastigotes in the blood and to high mortality. In the present study, we investigated whether NO production is essential for the control of T. cruzi in all phases of the infection. BALB/c mice were treated at different time intervals after T. cruzi infection with an iNOS inhibitor, aminoguanidine or l-N6-(1-iminoethyl)-lysine (L-NIL). Treatment initiated with the beginning of the infection resulted in 100% mortality by day 16 postinfection (p.i.). If treatment was started later during the acute phase at the peak of parasitemia (day 20 p.i.), all the mice survived. Parasitemia was cleared and tissue amastigotes became undetectable in these mice even in the presence of the iNOS inhibitor L-NIL. Inhibition of iNOS in the chronic phase of the infection, i.e., from day 60 to day 120 p.i., with L-NIL did not result in a reappearance of parasitemia. These data suggest that while NO is essential for T. cruzi control in the early phase of acute infection, it is dispensable in the late acute and chronic phase, revealing a fundamental difference in control mechanisms compared to those in infections by other members of the order Kinetoplastida, e.g., Leishmania major.

Trypanosoma cruzi is an obligate intracellular protozoan parasite of mammals and the etiologic agent of Chagas' disease. The parasite infects a variety of host cell types, including macrophages; intracellular replication as amastigotes is followed by the release of trypomastigotes that can reach the bloodstream before infecting other host cells. The acute phase is characterized by a large increase in parasite replication, and trypomastigotes are observed in the blood of infected mice. After control of the acute phase in immunocompetent mice, the infection turns into a chronic phase (starting around day 21 postinfection [p.i.]) where parasites are no longer detectable by light microscopy in the bloodstream but form inflammatory nests in various tissues, a process associated with chagasic pathology, in which antiparasite cytotoxic T lymphocytes or autoimmune mechanisms may play a role (14, 21, 29).

Several cell subsets of both the innate and the specific immune system were reported to be required for survival during the acute phase of the infection in murine T. cruzi infection, such as NK cells (4), CD4+ (20, 27) and CD8+ T cells (20, 26, 28), and B cells (11). Two essential mediators of resistance to T. cruzi have been found to be gamma interferon (IFN-γ) (1, 10, 12, 18, 23, 31) and nitric oxide (NO) (10, 17, 33), which has direct strong cytotoxic effects on T. cruzi (6, 33). IFN-γ is thought to be the most important inducer of the inducible NO synthase (iNOS) for increased NO production by macrophages (2, 8, 9) and thus essential for mediation of NO-dependent parasite control during acute infection.

There have been several reports that effector cell pathways essential for T. cruzi control during acute infection are dispensable during chronic infection (4, 16, 26). In this study, we found that this also applies for NO production during the chronic and also during the late acute phase; both phases are characterized by control through the adaptive immune system and not through NK cells (4). We show that there is only a narrow time window during acute infection where NO is indispensable.

(This study formed part of a Ph.D. thesis by M.S. at the Faculty of Biology, University of Hamburg.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and parasites.

Six- to eight-week-old IFN-γ knockout (KO) BALB/c mice and wild-type BALB/c littermates as well as C57BL/6 mice maintained under specific-pathogen-free conditions were used for the experiments.

Tulahuen strain T. cruzi blood trypomastigotes were routinely maintained by weekly intraperitoneal infection of BALB/c mice (7, 13). Blood was collected from mice by orbital puncture under anesthesia in tubes containing EDTA. Blood (10 μl) was diluted in 40 μl of Tris-ammonium chloride to lyse erythrocytes. Trypomastigotes were microscopically counted in a hemocytometer. For intraperitoneal infection of mice, the number of trypomastigotes was adjusted by dilution in phosphate-buffered saline.

Treatment with L-NIL and AG and determination of nitrite.

l-N6-(1-iminoethyl)-lysine (L-NIL) (Alexis, Grünwald, Federal Republic of Germany) and aminoguanidine (AG) (Sigma, Munich, Federal Republic of Germany) were dissolved at 3 mM and 90 mM, respectively, in drinking water, which was the only source for fluid intake of mice during the duration of blockade experiments. That the mice actually continued drinking normally was verified by recording of their weight twice a week. Production of NO in serum was assessed by determination of NO2− and NO3− in mouse sera (Griess reaction) as described elsewhere (19).

Determination of IFN-γ in serum.

IFN-γ concentrations in sera of mice were determined by specific two-site enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays using standard protocols. The antibody pairs for capture and detection (biotinylated) were purchased from Pharmingen (Hamburg, Federal Republic of Germany) in the combination recommended. Recombinant IFN-γ (Pharmingen) was used as a standard. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays were developed after incubation with streptavidin-peroxidase complex (1:10,000; Boehringer, Mannheim, Federal Republic of Germany), using 3,5,3′,5′-tetramethylbenzidine as substrate (dissolved [6 mg/ml] in dimethyl sulfoxide; Roth, Karlsruhe, Federal Republic of Germany). Sensitivity was 5 pg/ml.

PCR.

DNA was purified from blood samples using the QIAamp blood mini DNA kit from Qiagen (Hilden, Federal Republic of Germany). Two oligonucleotides (T1, 5′ GAC GGC AAG AAC GCC AAG GCA 3′; T2, 5′ TCA CGC GCT CTC CGG CAC GTT GTC 3′) derived from T. cruzi cDNA sequence coding for a 24-kDa protein were used as described elsewhere (15).

Histology.

Previously described protocols for histology were followed (5). Complete hearts and complete femoral muscles from each animal were fixed in 70% ethanol and embedded in paraffin using standard methods. Sections (4 μm thick) were prepared from each tissue. Tissue sections were first stained in hematoxylin (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) for 20 min and rinsed in tap water for 30 min, and this was followed by counterstaining with 1% (wt/vol) eosin (Merck) for 3 min. The tissue sections were analyzed with a light microscope at a magnification of ×1,000. For quantification of amastigote pseudocysts, two sections from each tissue of each animal were examined by an investigator who was not aware if the mice had received NO-blocking treatment before.

RESULTS

NO is produced early in infection during trypomastigote parasitemia.

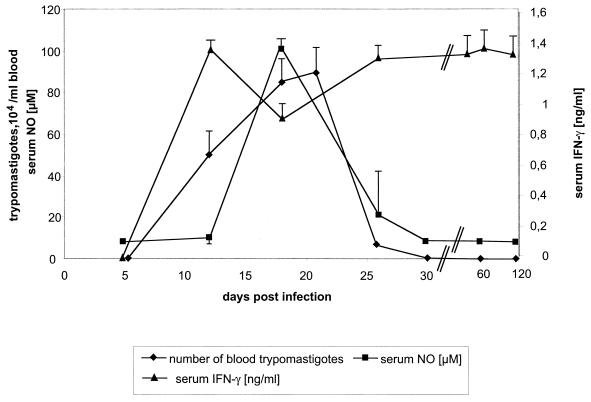

When infected with sublethal doses of 10 or 100 trypomastigotes, BALB/c mice developed peak parasitemia within 15 to 20 days p.i. (Fig. 1), consistent with the acute phase of T. cruzi infection. A high amount of IFN-γ was observed in the serum from 10 days p.i., and it was followed by the appearance of NO (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Parasitemia, serum NO, and serum IFN-γ of BALB/c mice infected with the T. cruzi Tulahuen strain. The mice were infected with 100 blood-derived trypomastigotes. The data are representative of five independent experiments using four animals per group and experiment. The arithmetic means ± standard deviations (error bars) are given. Interestingly, IFN-γ remains highly elevated during the chronic phase of infection. Consistent results were obtained when the inoculation dose was 10 trypomastigotes per mouse.

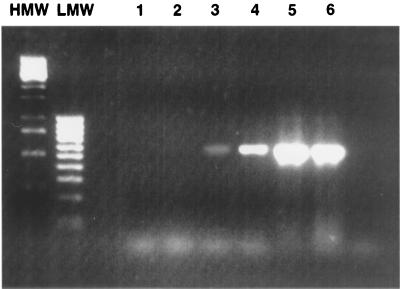

After 30 days p.i. mice developed the chronic phase of infection with no trypomastigote forms found in the blood (Fig. 1). Consistent with this, NO production decreased to levels undetectable in serum (Fig. 1). However, T. cruzi DNA was detected by PCR in the blood of BALB/c mice during both the acute and the chronic phases of T. cruzi infection (Fig. 2). T. cruzi DNA detectable in blood from the chronic phase was correlated with viable trypomastigotes since transfusion of those blood aliquots led to fulminant infection, with high parasitemia and death in IFN-γ KO mice (not shown). Interestingly, IFN-γ in the serum of wild-type BALB/c mice remained elevated in the chronic phase of infection (Fig. 1).

FIG. 2.

Detection of T. cruzi DNA in the blood of acute and chronically infected mice. Lanes 1 and 2, 10 and 100 μl of blood from uninfected mice, respectively; lanes 3 and 4, 10 and 100 μl of blood from chronically infected mice at day 90 p.i., respectively; lanes 5 and 6, 10 and 100 μl of blood from acutely infected mice at day 14 p.i. The data are representative of four independent experiments. HMW and LMW, high- and low-molecular-weight markers, respectively.

NO is essential for control of parasitemia and for survival in the early acute phase of infection.

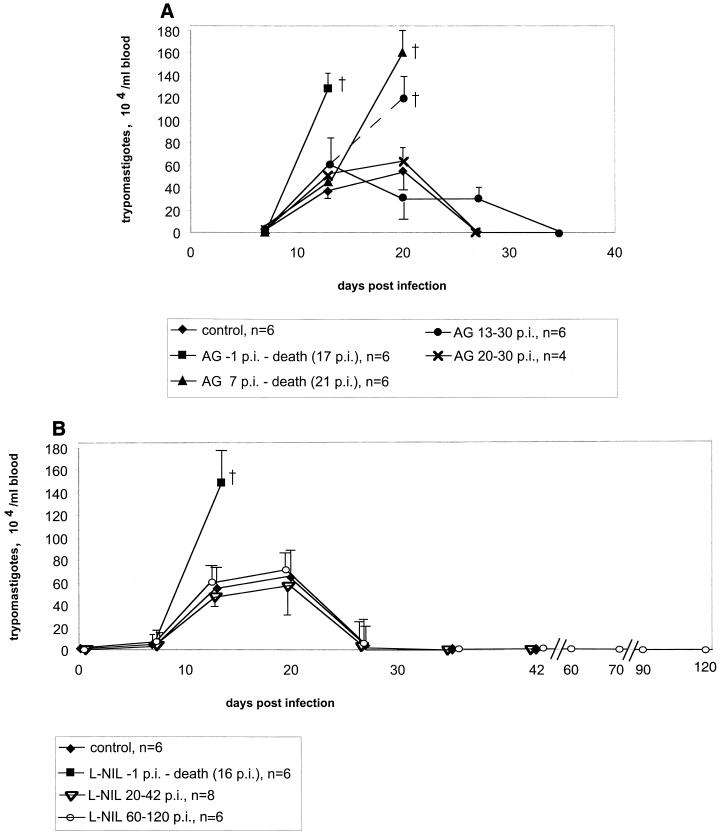

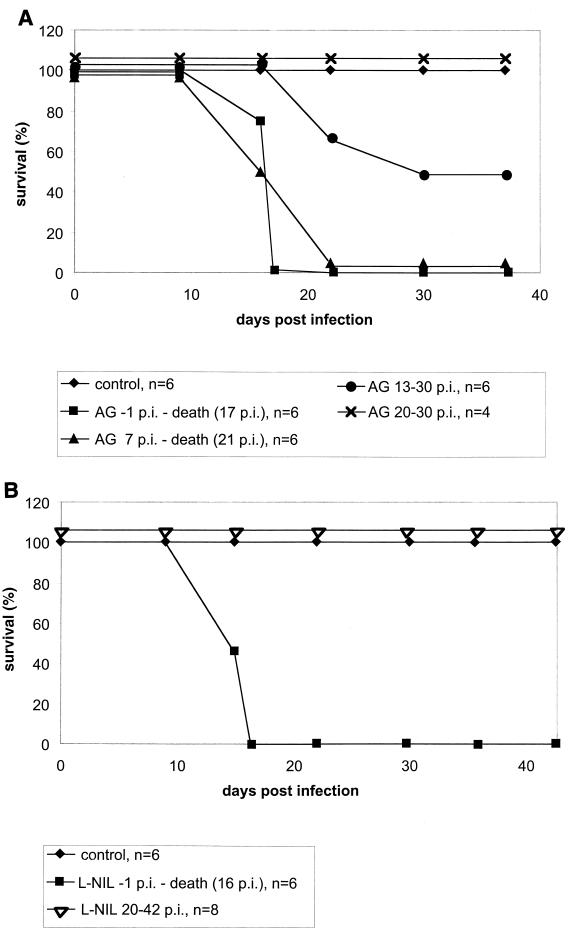

Administration of AG or L-NIL starting 1 day before the infection led to a high parasitemia (Fig. 3) and to 100% mortality of mice by day 17 p.i. (Fig. 4). The efficacies of AG and L-NIL were equivalent in this trial. When NO production was blocked by AG from day 7 p.i., the development of high parasitemia was delayed by 8 days (i.e., for the time span treatment was delayed; i.e., day −1 versus day 7 [Fig. 3A]), but mortality was still 100% (Fig. 4A). NO synthase inhibition from day 13 p.i. by AG resulted in only 50% mortality (Fig. 4A); in this group, those animals that died developed high parasitemia before death while those animals that survived eventually controlled their parasitemia (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 3.

Parasitemia of BALB/c mice infected with 100 blood-derived trypomastigotes of the Tulahuen strain. The treatment with AG (A) or L-NIL (B) was done as indicated in the figure. (A) For each time point, the arithmetic means ± standard deviations (error bars) for groups of four to six animals are given. The data are representative of three independent experiments (except for treatment from day 20 to 30 p.i., which was done two times). The values for the group receiving AG from days 13 to 30 p.i. are split at day 20 into the resistant (solid lines) and susceptible (dotted lines) subgroups. (B) For each time point, the means ± standard deviations (error bars) for groups of eight animals are given.

FIG. 4.

NO mediates survival of mice only during a small window in the early phase of the acute infection with T. cruzi Tulahuen. BALB/c mice were infected with 100 blood-derived trypomastigotes, and the treatment with AG (A) or L-NIL (B) in the drinking water was started as indicated. For each time point, the arithmetic means for four to six (A) or eight (B) animals are given. The data in panel A are representative of three independent experiments (except for treatment from day 20 to 30 p.i., which was done two times); in panel B, one experiment per group was performed. Note that in all animal groups, baseline survival at the beginning of the experiment was 100%. The lines are drawn not overlapping for clarity.

NO is dispensable for survival as well as blood and tissue parasite burden in the late acute phase of infection.

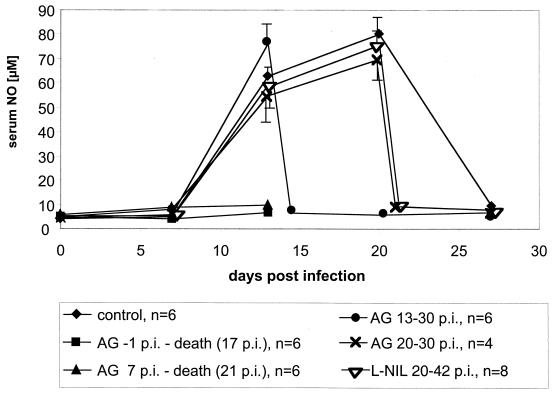

The above results suggested that NO is indispensable at a time during early T. cruzi infection (day 1 to 20) when the adaptive immune system is not yet effective but that it may become dispensable at later times. To gain further evidence for the existence of such a time window where NO is essential, NO synthase activity was blocked during the time when the adaptive immune system in this model is known to be involved in the control of the parasites (26) but the innate, NK-derived IFN-γ-dependent defense mechanisms are no longer essential (4), i.e., from day 20 p.i. on. Note that at this time, parasitemia is not yet under control since blood trypomastigote levels do not drop before 22 days p.i. (Fig. 1). NO in mouse serum has similar kinetics (Fig. 5).

FIG. 5.

NO in the serum of BALB/c mice infected with 100 blood-derived trypomastigotes of the Tulahuen strain. The treatment with AG or L-NIL was started as indicated in the figure. For each time point, the arithmetic mean ± standard deviation (error bar) for four, six, or eight animals is given. The data are representative of three independent experiments (except for treatment from days 20 to 30 p.i. which was done two times, and with L-NIL, which was done once).

NO synthase inhibition was carried out (i) with AG from day 20 p.i. (Fig. 5) to the time when there were no more trypomastigotes detectable in blood smears (day 30 p.i.) or (ii) with L-NIL from day 20 p.i. until day 42 p.i. This treatment led to an immediate drop in serum NO levels (Fig. 5). However, the parasitemia, which in this experiment was at its peak at day 20 p.i. (Fig. 3), declined to levels below the detection limit in blood smears in spite of either inhibitor, AG or L-NIL (Fig. 3B).

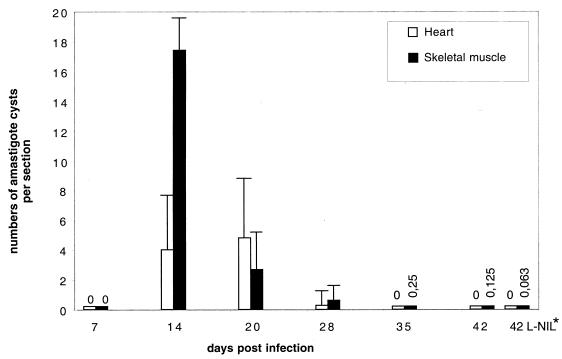

Importantly, NO depletion between day 20 and day 42 p.i. by L-NIL did not also affect the parasite burden in the hearts and skeletal muscles: the eight mice which had been treated with L-NIL from days 20 to 42 p.i. had been infected together with 24 control BALB/c mice which remained untreated. At weekly intervals, four mice of the untreated group were sacrificed, and amastigote pseudocysts in hearts and skeletal muscles were counted by histology. The number of pseudocysts peaked between days 14 and 20 and was reduced to one or zero per eight tissue sections (two sections from each animal per time point [Fig. 6]). The subgroup of eight mice which were treated with L-NIL from days 20 to 42 p.i. was sacrificed at day 42 p.i.; two sections were counted from each tissue per animal. The results revealed that the amastigote pseudocyst number had also declined to levels equivalent to those of untreated animals (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Quantification of amastigote pseudocysts from hearts and skeletal muscles of BALB/c mice infected with 100 blood-derived trypomastigotes. Tissues were subjected to histological analysis as described in Materials and Methods. Amastigote pseudocysts were counted with a light microscope at a magnification of ×1,000. Two sections of different parts of each tissue from each animal were completely analyzed. Thirty-two animals were used for this experiment. At each time point from day 7 until day 42 p.i., four animals were sacrificed and tissues were analyzed. The arithmetic means + standard deviations (error bars) are given. ∗, eight animals which had been infected in the same experimental series were given L-NIL from days 20 to 42 p.i. and were sacrificed at day 42 p.i.

NO inhibition does not affect the chronic phase of T. cruzi infection.

Inhibition of NO production by either AG or L-NIL during the chronic phase (days 60 to 120 p.i.) did not lead to mortality or reappearance of parasitemia (Table 1; Fig. 3B).

TABLE 1.

Summarya of effects of NOS2 inhibition on parasite loads and mortality during acute and chronic T. cruzi infection

| No inhibitor | NOS2 inhibition (days p.i.) | Exacerbation of parasitesab | Mortalitya |

|---|---|---|---|

| AG | −1–17 | 18/18 | 18/18 |

| 7–21 | 18/18 | 18/18 | |

| 13–30 | 7/14 | 7/14 | |

| 20–30 | 0/8 | 0/8 | |

| 60–120 | 0/10 | 0/10 | |

| L-NIL | −1–16 | 6/6 | 6/6 |

| 7–21 | NDc | ND | |

| 13–30 | ND | ND | |

| 20–42 | 0/8 | 0/8 | |

| 60–120 | 0/8 | 0/8 |

Animals from all experiments are listed. Results are give as no. of animals showing characteristic/total no. of animals.

Exacerbation was defined as significantly elevated parasitemia (>x̄ ± 3 standard deviations) after T. cruzi infection.

ND, not determined

DISCUSSION

The results generated in this study allow a more precise view of the trypanocidal role of NO in the control of murine T. cruzi infection. The essentiality of iNOS induction for parasite control has been demonstrated using enzyme blockers (17) or iNOS KO mice (10); the latter mice had much higher parasite loads in blood and tissue, which were associated with extreme susceptibility (100% mortality after application of only 15 blood forms/mouse [10]). NO activity was linked to trypanocidal action of macrophages given that IFN-γ rendered infected macrophages capable of inhibiting intracellular replication of T. cruzi in vitro by a mechanism that involves the production of NO (8). Recently, more molecular pathways of NO action on the parasites have been elucidated (30, 32). By depletion studies as well as gene KO (10, 17), IFN-γ as well as a variety of cells that produce this cytokine (NK [4], γδ [22], CD4+ [20, 27] and CD8+ T cells [26, 28]) was shown to be essential for protection against T. cruzi. However, the consensus of these studies is that depletion of any of these cell subsets affects only the early, acute phase of infection while it does not lead to a reversion of parasitemia if depletion is initiated after blood stage trypomastigotes have disappeared from the blood (3, 12, 26).

We show here that this also applies to NO-mediated parasite control: while there was a strong exacerbation of parasitemia, with 100% mortality in animals treated from the beginning of infection with NO-synthase inhibitor L-NIL or AG (Table 1; Fig. 3), it was impossible to render animals parasitemic by long-term (60 days) AG or L-NIL application if started at day 60 p.i. (Table 1; Fig. 3). In addition, it was impossible to increase parasite loads both in blood and in tissue by NO blockade after day 20 p.i.; in contrast, tissue and blood parasite levels declined in the presence of either NOS inhibitor (Fig. 3).

This is in contrast to murine infection with another kinetoplastid, Leishmania major. Here it was shown that in chronic infection (123 days p.i.), L-NIL application led to a reactivation of cutaneous lesions in C57BL/6 mice which became significant after only 17 days of treatment (24). In our own laboratory, we extended these findings when treating C57BL/6 mice with L-NIL towards the end of the acute phase of L. major infection, i.e., at a time when the footpad swelling is already declining: we observed a fast reactivation of cutaneous lesions in these mice which became significant as early as 10 days following the initiation of L-NIL administration (data not shown). This is in strong contrast to the further decline of T. cruzi parasite loads in blood and tissue at the end of the acute phase under L-NIL treatment (days 20 to 42 p.i.).

Thus, comparison of these two infections strongly suggests that fundamental differences in the control of chronic T. cruzi and L. major infections exist. A potential reason for this discrepancy is that L. major resides in macrophages which control infection by NO whereas T. cruzi also invades other types of cells which do not express iNOS.

A main novel finding of our study is that NO is not even essential for the whole period of acute infection: blood parasite levels, in our experimental system, did not decline before day 22 p.i. In untreated mice, the levels of NO reaction products in the serum fell concomitantly with blood parasite loads (Fig. 1), and NO synthase inhibition during that period did not block clearance of parasites from blood (Fig. 3). Consistently, NO synthase inhibition, if initiated from day 20 p.i., did not affect survival, in contrast to earlier inhibition, i.e., from day −1 or day 7 p.i. (Fig. 4). When treatment was started at day 13 p.i., mortality was only 50% (Fig. 4). This reflects a decreasing need for NO in parasitemia control from day 7 p.i. (essential) to day 20 p.i. (dispensable). Importantly, tissue amastigotes, after day 20 p.i., are also controlled by mechanisms other than NO, since L-NIL treatment did not prevent the reduction of pseudocysts in hearts and skeletal muscles, so that equivalent low levels of amastigotes were found both in the presence and in the absence of L-NIL at day 42 p.i. (Fig. 6).

The question of whether AG is as potent an NO synthesis blocker as is L-NIL may be raised. AG was shown to be indeed inferior to L-NIL on a molar ratio in vitro (25). However, these authors did not compare the two inhibitors in vivo, in contrast to us, and we adapted the molarity of the inhibitors for our in vivo study to equipotent levels. We always got consistent results with AG and L-NIL (Table 1; Fig. 3 and 4).

Our data fit very well to earlier observations that IFN-γ itself is not needed during the whole acute phase of T. cruzi infection: IFN-γ neutralization did not alter the parasite load of mice if applied later than day 11 p.i. (4). It was also shown that this early IFN-γ production is dependent on the presence of NK cells in T. cruzi infection (4). In contrast, if T. cruzi-infected mice are depleted of CD8+ T cells, parasitemia is unaltered compared to that in control infected mice until day 21 p.i., but thereafter, blood parasite loads rise quickly and mice die from infection (26). Mice lacking CD8+ T cells through gene KO also die around day 28 (i.e., later than in our study when NO production was blocked) despite elevated IFN-γ (28).

Taking all these results into account, it appears that NO is essential for the parasite control during the first 2 weeks of infection, i.e., a time when NK cells are known to control the parasite load through IFN-γ production (4). It is, however, dispensable thereafter in late acute infection, i.e., during the period when blood parasite levels decrease under the control of CD8+ T cells (26). Thus, the synopsis of the results suggests a cascade of events where NK cells, by their production of IFN-γ, activate effector cells, most likely macrophages, to induce NOS2 and to exert control of early parasite replication. After 2 weeks p.i., this mechanism is gradually replaced by the action of the adaptive immune system in which CD8+ T cells (20, 26, 28), and apparently CD4+ T cells (20, 27) and B cells (11) producing neutralizing antibodies, act in concert to further limit parasite replication in an NO-independent way.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Financial support from the German Research Society and the Volkswagen Foundation is acknowledged (grant Ho/2009-1 and grant I/71544).

We thank Christiane Steeg and Sebastian Graefe for advice and Yvonne Richter for help with the animal maintenance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abrahamsohn I A, da Silva A P, Coffman R L. Effects of interleukin-4 deprivation and treatment on resistance to Trypanosoma cruzi. Infect Immun. 2000;68:1975–1979. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.4.1975-1979.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aliberti J C, Machado F S, Souto J T, Campanelli A P, Teixeira M M, Gazzinelli R T, Silva J S. β-Chemokines enhance parasite uptake and promote nitric oxide-dependent microbiostatic activity in murine inflammatory macrophages infected with Trypanosoma cruzi. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4819–4826. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4819-4826.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cardillo F, Falcao R P, Rossi M A, Mengel J. An age-related gamma delta T cell suppressor activity correlates with the outcome of autoimmunity in experimental Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Eur J Immunol. 1993;23:2597–2605. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830231033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cardillo F, Voltarelli J C, Reed S G, Silva J S. Regulation of Trypanosoma cruzi infection in mice by gamma interferon and interleukin 10: role of NK cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:128–134. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.128-134.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Diego J A, Palau M T, Gamallo C, Penin P. Relationships between histopathological findings and phylogenetic divergence in Trypanosoma cruzi. Trop Med Int Health. 1998;3:222–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.1998.tb00275.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Denicola A, Rubbo H, Rodriguez D, Radi R. Peroxynitrite-mediated cytotoxicity to Trypanosoma cruzi. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1993;304:279–286. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1993.1350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frosch S, Kraus S, Fleischer B. Trypanosoma cruzi is a potent inducer of interleukin-12 production in macrophages. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1996;185:189–193. doi: 10.1007/s004300050030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gazzinelli R T, Oswald I P, Hieny S, James S L, Sher A. The microbicidal activity of interferon-gamma-treated macrophages against Trypanosoma cruzi involves an L-arginine-dependent, nitrogen oxide-mediated mechanism inhibitable by interleukin-10 and transforming growth factor-beta. Eur J Immunol. 1992;22:2501–2506. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830221006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golden J M, Tarleton R L. Trypanosoma cruzi: cytokine effects on macrophage trypanocidal activity. Exp Parasitol. 1991;72:391–402. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(91)90085-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hölscher C, Kohler G, Muller U, Mossmann H, Schaub G A, Brombacher F. Defective nitric oxide effector functions lead to extreme susceptibility of Trypanosoma cruzi-infected mice deficient in gamma interferon receptor or inducible nitric oxide synthase. Infect Immun. 1998;66:1208–1215. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.3.1208-1215.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar S, Tarleton R L. The relative contribution of antibody production and CD8+ T cell function to immune control of Trypanosoma cruzi. Parasite Immunol. 1998;20:207–216. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3024.1998.00154.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCabe R E, Meagher S G, Mullins B T. Endogenous interferon-gamma, macrophage activation, and murine host defense against acute infection with Trypanosoma cruzi. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:912–915. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.4.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meyer Zum Büschenfelde C, Cramer S, Trumpfheller C, Fleischer B, Frosch S. Trypanosoma cruzi induces strong IL-12 and IL-18 gene expression in vivo: correlation with interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma) production. Clin Exp Immunol. 1997;110:378–385. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1997.4471463.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Minoprio P, el Cheikh M C, Murphy E, Hontebeyrie-Joskowicz M, Coffman R, Coutinho A, O'Garra A. Xid-associated resistance to experimental Chagas' disease is IFN-gamma dependent. J Immunol. 1993;151:4200–4208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ouaissi A, Aguirre T, Plumas-Marty B, Piras M, Schoneck R, Gras-Masse H, Taibi A, Loyens M, Tartar A, Capron A, et al. Cloning and sequencing of a 24-kDa Trypanosoma cruzi specific antigen released in association with membrane vesicles and defined by a monoclonal antibody. Biol Cell. 1992;75:11–17. doi: 10.1016/0248-4900(92)90119-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Petray P, Castanos-Velez E, Grinstein S, Orn A, Rottenberg M E. Role of nitric oxide in resistance and histopathology during experimental infection with Trypanosoma cruzi. Immunol Lett. 1995;47:121–126. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(95)00083-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Petray P, Rottenberg M E, Grinstein S, Orn A. Release of nitric oxide during the experimental infection with Trypanosoma cruzi. Parasite Immunol. 1994;16:193–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1994.tb00340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reed S G. In vivo administration of recombinant IFN-gamma induces macrophage activation, and prevents acute disease, immune suppression, and death in experimental Trypanosoma cruzi infections. J Immunol. 1988;140:4342–4347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rockett K A, Awburn M M, Rockett E J, Cowden W B, Clark I A. Possible role of nitric oxide in malarial immunosuppression. Parasite Immunol. 1994;16:243–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1994.tb00346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rottenberg M E, Riarte A, Sporrong L, Altcheh J, Petray P, Ruiz A M, Wigzell H, Orn A. Outcome of infection with different strains of Trypanosoma cruzi in mice lacking CD4 and/or CD8. Immunol Lett. 1995;45:53–60. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(94)00221-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Russo M, Starobinas N, Minoprio P, Coutinho A, Hontebeyrie-Joskowicz M. Parasitic load increases and myocardial inflammation decreases in Trypanosoma cruzi-infected mice after inactivation of helper T cells. Ann Inst Pasteur Immunol. 1988;139:225–236. doi: 10.1016/0769-2625(88)90136-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Santos Lima E C, Minoprio P. Chagas' disease is attenuated in mice lacking γδ T cells. Infect Immun. 1996;64:215–221. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.1.215-221.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Silva J S, Morrissey P J, Grabstein K H, Mohler K M, Anderson D, Reed S G. Interleukin 10 and interferon gamma regulation of experimental Trypanosoma cruzi infection. J Exp Med. 1992;175:169–174. doi: 10.1084/jem.175.1.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stenger S, Donhauser N, Thüring H, Röllinghoff M, Bogdan C. Reactivation of latent leishmaniasis by inhibition of inducible nitric oxide synthase. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1501–1514. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.4.1501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stenger S, Thüring H, Röllinghoff M, Manning P, Bogdan C. L-N6-(1-iminoethyl)-lysine potently inhibits inducible nitric oxide synthase and is superior to NG-monomethyl-arginine in vitro and in vivo. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;294:703–712. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00618-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tarleton R L. Depletion of CD8+ T cells increases susceptibility and reverses vaccine-induced immunity in mice infected with Trypanosoma cruzi. J Immunol. 1990;144:717–724. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tarleton R L, Grusby M J, Postan M, Glimcher L H. Trypanosoma cruzi infection in MHC-deficient mice: further evidence for the role of both class I- and class II-restricted T cells in immune resistance and disease. Int Immunol. 1996;8:13–22. doi: 10.1093/intimm/8.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tarleton R L, Koller B H, Latour A, Postan M. Susceptibility of beta 2-microglobulin-deficient mice to Trypanosoma cruzi infection. Nature. 1992;356:338–340. doi: 10.1038/356338a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tarleton R L, Zhang L. Chagas disease etiology: autoimmunity or parasite persistence? Parasitol Today. 1999;15:94–99. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(99)01398-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Thomson L, Gadelha F R, Peluffo G, Vercesi A E, Radi R. Peroxynitrite affects Ca2+ transport in Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1999;98:81–91. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00149-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Torrico F, Heremans H, Rivera M T, Van Marck E, Billiau A, Carlier Y. Endogenous IFN-gamma is required for resistance to acute Trypanosoma cruzi infection in mice. J Immunol. 1991;146:3626–3632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Venturini G, Salvati L, Muolo M, Colasanti M, Gradoni L, Ascenzi P. Nitric oxide inhibits cruzipain, the major papain-like cysteine proteinase from Trypanosoma cruzi. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;270:437–441. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vespa G N, Cunha F Q, Silva J S. Nitric oxide is involved in control of Trypanosoma cruzi-induced parasitemia and directly kills the parasite in vitro. Infect Immun. 1994;62:5177–5182. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.5177-5182.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]