Abstract

This study provides the first definitive evidence that the gram-negative bacterium Plesiomonas shigelloides adheres to and enters eukaryotic intestinal host cells in vitro. P. shigelloides is increasingly regarded as an emerging enteric pathogen and has been implicated in intestinal and extraintestinal infections in humans. However, the establishment of its true role in enteric disease has been hindered by inadequacies in experimental design, deficiencies in clinical diagnosis, and the lack of an appropriate animal model. In this investigation, an in vitro system was used to evaluate plesiomonad pathogenesis. Differentiated epithelium-derived Caco-2 cell monolayers inoculated apically with 12 isolates of P. shigelloides from clinical (intestinal) origins were examined at high resolution using transmission electron microscopy. Bacterial cells were observed adhering to intact microvilli and to the plasma membrane on both the apical and the basal surfaces of the monolayer. The bacteria entered the Caco-2 cells and were observed enclosed in single and multiple membrane-bound vacuoles within the host cell cytoplasm. This observation suggests that initial uptake may occur through a phagocytic-like process, as has been documented for many other enteropathogens. P. shigelloides also was noted free in the cytosol of Caco-2 cells, suggesting escape from cytoplasmic vacuoles. Differences in invasion phenotypes were revealed, suggesting the possibility that, like Escherichia coli, P. shigelloides comprises different pathogenic phenotypes.

Diarrhea is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in populations in developing countries and is a substantial health issue throughout the world (39). Despite the frequency and the severity of disease, mechanisms of pathogenesis for many of the causative agents have been poorly characterized. Indeed, new and emerging causative agents continue to be identified. Diarrheal diseases most often are caused by gram-negative bacteria belonging to the families Enterobacteriaceae and Vibrionaceae (11). However, a number of notable gram-positive enteropathogens, as well as protozoal and viral etiological agents, are of considerable concern (11, 19).

Plesiomonas shigelloides historically has been considered of little enteropathogenic significance due to the lack of clearly demonstrated virulence factors, such as enterotoxins, cytotoxins, or invasive abilities (2, 6, 15, 16, 18, 20, 25, 26, 33). However, recent epidemiological evidence has strongly implicated P. shigelloides as a significant cause of diarrheal disease; in Japan, it is considered to rank third (at 5.6%) as a cause of traveler's diarrhea (35).

The genus Plesiomonas traditionally has been placed within the family Vibrionaceae based on phenetic classification (34) and, thus, is considered closely related to Vibrio cholerae and Aeromonas spp. Both phylogenetic analyses and antigenic profiling, however, indicate a closer relationship with members of the family Enterobacteriaceae (31). The genus presently consists of a single species, P. shigelloides. It is a gram-negative, non-endospore-forming, rod-shaped bacterium, reported to be motile by virtue two to five polar flagella (34).

P. shigelloides has been considered an opportunistic pathogen in the immunocompromised host and has been isolated from a wide variety of sources, including soil, surface water, food, wild and domestic animals, and diarrheic and asymptomatic humans (5, 7, 8, 9, 16, 20). It is presumed that the consumption of or exposure to contaminated water sources or food derived from such sources serves as the prime mechanism for the transmission of P. shigelloides diarrheal disease (1, 4, 37).

The gastrointestinal form of plesiomonad infections in humans has been classified into three main groups: a secretory gastroenteritis, a cholera-like illness clinically resembling V. cholerae infection, and a diarrheal form clinically resembling shigellosis (9). The last has symptoms which appear indicative of an invasive infection yet, to date, there is no conclusive evidence that P. shigelloides can invade eukaryotic cells.

The few published studies investigating the invasive capabilities of P. shigelloides have been inconclusive (2, 6, 15, 25, 33), and recognition of this organism as an enteropathogen has been hindered by inadequacies in experimental design and the lack of an animal model. Experimental data used in an attempt to resolve the pathogenic potential of P. shigelloides have relied strongly on light microscopy studies and the use of nongastrointestinal cell lines (2, 6, 15, 25, 33). Clearly, there are some deficiencies in this approach. The resolution of light microscopy is not sufficient to definitively determine whether bacterial cells have invaded or merely have adhered to host cell surfaces. Moreover, the use of nongastrointestinal cell lines raises questions as to the validation of effects in the gastrointestinal tract. Additionally, only one these studies (2) included the type strain, therefore compromising interlaboratory standardization.

Despite the lack of experimental evidence of invasiveness, blood and mucus found in diarrheal stools from P. shigelloides intestinal infections are strongly suggestive of an invasion process. In order to determine the virulence mechanisms of potential enteropathogens such as P. shigelloides, an in vitro invasion assay that uses intestinal cells should provide more relevant data with respect to enteroinvasiveness than should assays with cell types not normally encountered in the intestinal tract. Further examination of well-characterized P. shigelloides isolates, including the type strain and clinical isolates associated with diarrhea, would be a rational approach to determining the pathogenic potential of this organism.

Given the conflicting data reported by other investigators regarding the pathogenic potential of P. shigelloides and the lack of a suitable animal model, we examined the ability of this organism to interact with the human colon carcinoma-derived cell line Caco-2 in vitro. Specifically, we investigated morphological changes to host cells during attachment and penetration of bacteria and examined ultrastructural features associated with bacteria found in the host cell cytoplasm.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Caco-2 cells.

The human epithelial cell line Caco-2 (ATCC HTB37) was grown at 37°C in Eagle's minimal essential medium (EMEM) (Sigma) with nonessential amino acids and supplemented with 20% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Commonwealth Serum Laboratories) in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Confluent differentiated growth was obtained in 25-cm2 tissue culture flasks (Nunclon) and 21-cm2 petri dishes (Nunclon) as required. Caco-2 cells were present at approximately 4.0 × 106 cells per flask or dish at confluence.

Bacterial isolates.

Twelve isolates of P. shigelloides, including the type strain (ATCC 14029), were examined. Table 1 outlines information pertinent to isolates. Isolates were stored on a bead recovery system in the culture collection of the Microbiology Section, Queensland University of Technology. To confirm the identity of each test isolate prior to experimental assays, biochemical tests (arginine dihydrolase, lysine decarboxylase, ornithine decarboxylase, oxidase, and catalase) were performed according to standard methods (34). Gram reactions and colony morphologies on inositol brilliant green bile salts medium were determined. Additionally, to assess the surface morphology of P. shigelloides, bacterial cells were negatively stained (in duplicate) with 1% uranyl acetate and examined using a JEOL 1200EX transmission electron microscope.

TABLE 1.

Details of P. shigelloides isolates used in this study

| Isolate | Serovara | Source (all human) | Supplier | Geographical location |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATCC 14029 | U | Infection | American Type Culture Collection | Type strain |

| 0958 | O17:H2 | Feces | E. Aldova | Croatia |

| 0967 | O90:H2 | Feces | E. Aldova | Czech Republic |

| 0968 | 035:H11 | Feces | E. Aldova | Czech Republic |

| 0977 | O17:H11 | Feces | E. Aldova | Czech Republic |

| 0981 | O36:H34 | Gallbladder | E. Aldova | Czech Republic |

| Ps12 | U | Feces | M. Janda | United States |

| Ps13 | U | Feces | M. Janda | United States |

| Ps18 | U | Feces | M. Janda | United States |

| Ps22 | U | Feces | M. Tandy | Australia |

| Ps23 | U | Feces | M. Tandy | Australia |

| Ps28 | U | Feces | M. Tandy | Australia |

U, unknown serogroup (not tested).

Bacterial controls used in assays were Escherichia coli (ATCC 25922), Listeria monocytogenes (UQM278/88), and Shigella flexneri (NCTC 9722/CSL/70).

Bacterial adhesion and invasion assays. (i) Light microscopy.

Caco-2 cells were grown to confluence on 13-mm-diameter glass coverslips placed in 21-cm2 petri dishes with 8 ml of EMEM supplemented with 20% FBS. Caco-2 cell monolayers were inoculated 7 days postconfluence with 12 isolates of P. shigelloides (20 μl of a suspension of 107 cells per ml in nutrient broth). Bacterial cells were added to the Caco-2 cells in the form of a medium change with fresh EMEM supplemented with 1% FBS. After incubation at 37°C in 5% CO2, a coverslip was removed for each isolate at time 0 and at 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, and 24 h postinfection and fixed in 100% methanol for 10 min. The cells on the coverslip were stained with Giemsa stain (Sigma) and then mounted (cell side down) on microscope slides. Stained coverslips were examined by light microscopy using a photomicroscope (Carl Zeiss). Representative photographs of bacterial interactions with Caco-2 cells were taken with a Jenaval camera using Ilford Pan F film. Concurrently, control organisms were used to infect Caco-2 cell monolayers in the same manner as that described for P. shigelloides. Uninfected Caco-2 cells were sampled at corresponding time to assess morphological changes occurring over the time course of the assay.

(ii) Transmission electron microscopy.

Caco-2 cells were grown to confluence in 25-cm2 tissue culture flasks and inoculated 7 days postconfluence with 20 μl of bacterial suspensions (107 cells per ml in nutrient broth) of 12 P. shigelloides isolates and the control organisms as described for light microscopy assays. Samples of each isolate (each sample being the entire contents of one tissue culture flask) were fixed with 3% glutaraldehyde (ProSciTech) fixative (in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer; pH 7.3) at time 0 and at 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, and 12 h postinfection. Samples of uninfected Caco-2 cells were taken at corresponding times. After fixation for 1 h at room temperature, cells were scraped off tissue culture flasks, washed in buffer, postfixed in 1% osmium tetroxide, and embedded in Spurr epoxy resin according to standard procedures (29). Ultrathin sections (50 to 100 nm) were cut, and uranyl acetate and lead citrate stains were applied prior to examination and photography with a JEOL 1200EX transmission electron microscope.

RESULTS

Light microscopy of P. shigelloides-infected Caco-2 cell monolayers.

Throughout the duration of the infection assays (i.e., 24 h), the cellular morphology of uninfected Caco-2 cells did not change. Caco-2 cells within the confluent monolayers were tightly packed, each with a distinguishable nucleus and a prominent cytoplasm. The cells had a high nucleus/cytoplasm ratio.

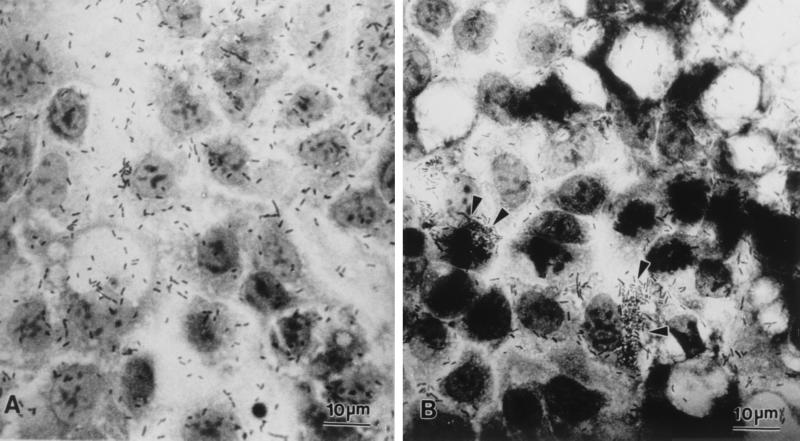

At 2 h postinfection, differences among the 12 isolates of P. shigelloides were noted with respect to bacterial cell distribution relative to host Caco-2 cells. Host cell-Plesiomonas interactions were initially of two types: bacterial cells interacted in a nondiscriminatory fashion and were diffusely distributed across the Caco-2 cell monolayer (Fig. 1A) or bacterial cells formed clusters which were frequently observed near host cell junctions while central regions of Caco-2 cells usually remained relatively free of bacteria (Fig. 1B). By 4 h postinfection, clumping of bacterial cells at the periphery of Caco-2 cells and especially in the vicinity of host cell junctions became more prominent. This pattern was observed with the majority of P. shigelloides isolates examined (ATCC 14029, 0967, 0968, 0981, Ps12, Ps13, Ps18, and Ps22).

FIG. 1.

Light micrographs demonstrating genetic interactions of P. shigelloides with Caco-2 cell monolayers. Interactions initially were of two types: bacterial cells distributed uniformly across the Caco-2 cell monolayer (A) or clumped at host cell junctions (arrowheads) (B).

At 8 h postinfection, a confluent monolayer of Caco-2 cells was no longer seen covering the coverslip; the Caco-2 cell monolayer appeared disrupted, with a decrease in the number of cells constituting the monolayer. Individual cells, well separated from adjacent cells, were noted with the majority of P. shigelloides isolates examined. The Caco-2 cells that were present had condensed nuclei and a shrunken cytoplasm and often appeared apoptotic.

However, Caco-2 cells had become highly vacuolated by 8 h postinfection with several P. shigelloides isolates (Ps12, Ps13, and Ps22). High concentrations of bacteria were noted at junctions between Caco-2 cells, on top of the Caco-2 cell monolayer, and apparently within vacuoles in the Caco-2 cell cytoplasm. Bacterial cells were observed surrounding individual Caco-2 cells and possibly localized between cells. It appeared that infection with these isolates of P. shigelloides caused detachment of Caco-2 cells from the monolayer and, ultimately, death of these host cells.

At 16 to 24 h postinfection with most P. shigelloides isolates (ATCC 14029, 0958, 0967, 0968, 0977, 0981, Ps12, Ps13, Ps18, Ps22, and Ps23), the Caco-2 cell monolayer had completely degenerated and detached from the coverslip, leaving only bacterial cells. However, some nuclear remnants of Caco-2 cells remained in some samples, and bacterial cells were heavily concentrated around them.

Bacteria used as controls in this study were noted to interact with Caco-2 cells, as has been described in previous reports (12, 27). Throughout the duration of the infection, S. flexneri (NCTC 9722/CSL/70) showed a nondiscriminatory pattern, where the bacterial cells were observed diffusely distributed across the Caco-2 cells monolayer. E. coli (ATCC 25922) and L. monocytogenes (UQM278/88) showed a diffuse distribution of bacteria across the Caco-2 cell monolayer during the early stages of infection, but from 4 h postinfection on, large groups of bacteria surrounded individual Caco-2 cells. By 16 h postinfection, the Caco-2 cell monolayer was disrupted, leaving nuclear remnants of Caco-2 cells with bacterial cells heavily concentrated around them.

Transmission electron microscopy of P. shigelloides isolates.

Negative staining of P. shigelloides isolates revealed bacteria with variations in cell size and flagellum morphology. The sizes of bacterial cells varied within and among isolates and ranged from 1.5 to 8.0 μm in length. Flagella were present on all 12 P. shigelloides isolates examined. The number of flagella per cell ranged from one to seven; the majority of isolates, including the type strain, possessed two to five flagella. Fimbria-like structures were not noted on any cells for any of the isolates, nor was a glycocalyx observed.

Transmission electron microscopy of P. shigelloides-infected Caco-2 cell monolayers.

Apical surfaces of uninfected (negative control) Caco-2 cells displayed microvilli and, in general, well-defined brush borders (Fig. 2A). However, irregularities in the distribution and in the shape of microvilli were observed. Tight junctions were noted between cells (Fig. 2A), reflecting the polarized nature of this cell line. Interdigitations between adjacent cells were observed, but the plasma membranes frequently were well separated, with considerable intervening space that often could be mistaken for large vacuoles (Fig. 2A). Some mitotic cells and a few necrotic cells were noted in all samples. The cellular morphology of uninfected Caco-2 cells remained unaltered over the 12 h assay period.

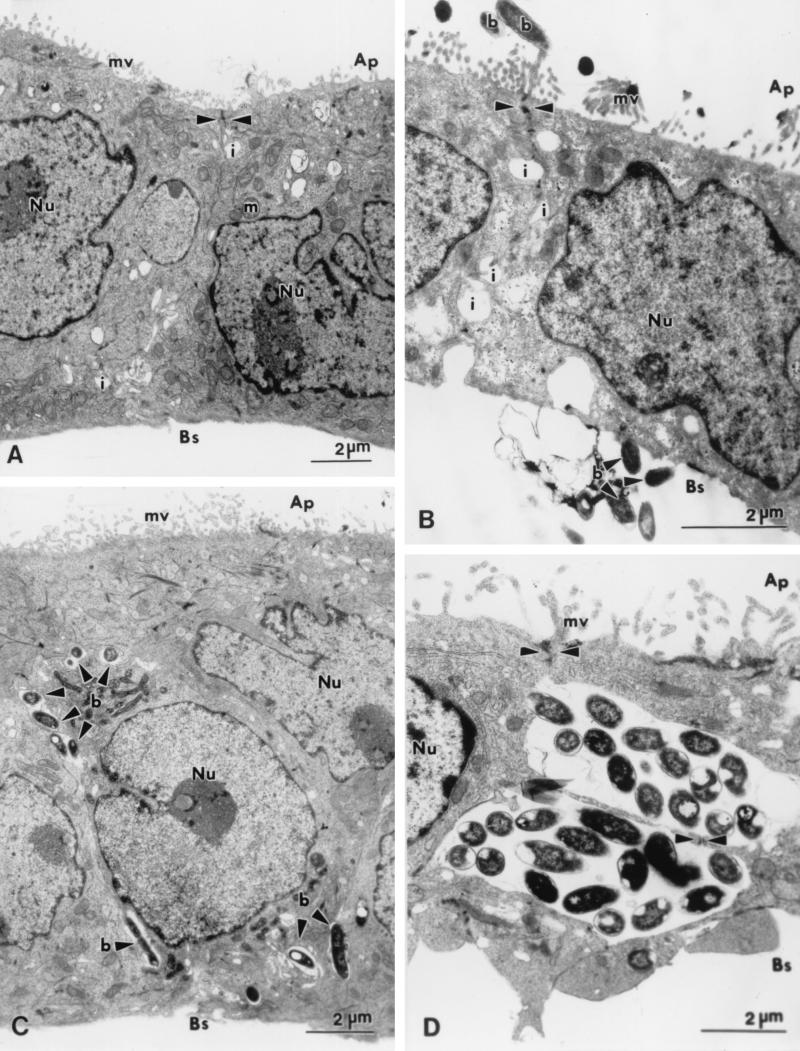

FIG. 2.

Transmission electron micrographs illustrating the locations of P. shigelloides in relation to polarized Caco-2 cell monolayers. (A) Uninfected Caco-2 cells showing epithelial differentiation, with a brush border of microvilli (mv) at the apical surface and tight junctions (arrowheads) between adjacent cells. Interdigitations (i), often appearing morphologically similar to vacuoles, are seen between cells. (B) Adherent bacterial cells (b) in association with both the apical microvilli and the basal plasma membrane. (C) Bacteria (b) between adjacent Caco-2 cells. Tight junctions (arrowheads) and interdigitations are seen between adjacent Caco-2 cells. (D) Numerous bacterial cells are observed within interdigitations between adjacent cells. Tight junctions and desmosomes (arrowheads) appear intact. Ap, apical surface; Bs, basal surface; m, mitochondrion; Nu, nucleus.

In the early stages of infection, Caco-2 cells infected apically with P. shigelloides were morphologically indistinguishable from uninfected cells; there were also no apparent differences among cells infected with different isolates. From 3 h postinfection on, bacteria were intimately attached to both the apical and the basal Caco-2 cell surfaces (Fig. 2B and 3B). When large numbers of bacteria were adherent to the cell surface, extensive areas of cell cytoplasm, enclosed by plasma membrane but bereft of organelles and microvilli, appeared to extrude from some cells (Fig. 3C). Bacterial adherence to both the plasma membrane and microvilli was often observed in the vicinity of tight junctions (Fig. 2B and 3A). Cells of most isolates of P. shigelloides interacted more with the intact microvilli at the apical surface of the Caco-2 cell monolayer than with the basolateral surface. However, in contrast, cells of one isolate (Ps12) interacted more with the basal surface of the monolayer. Notably, cells of isolates 0977 and 0958 did not interact with either the basal or the apical surface; these were the only isolates examined which did not show any close association with the Caco-2 cell monolayer at this time.

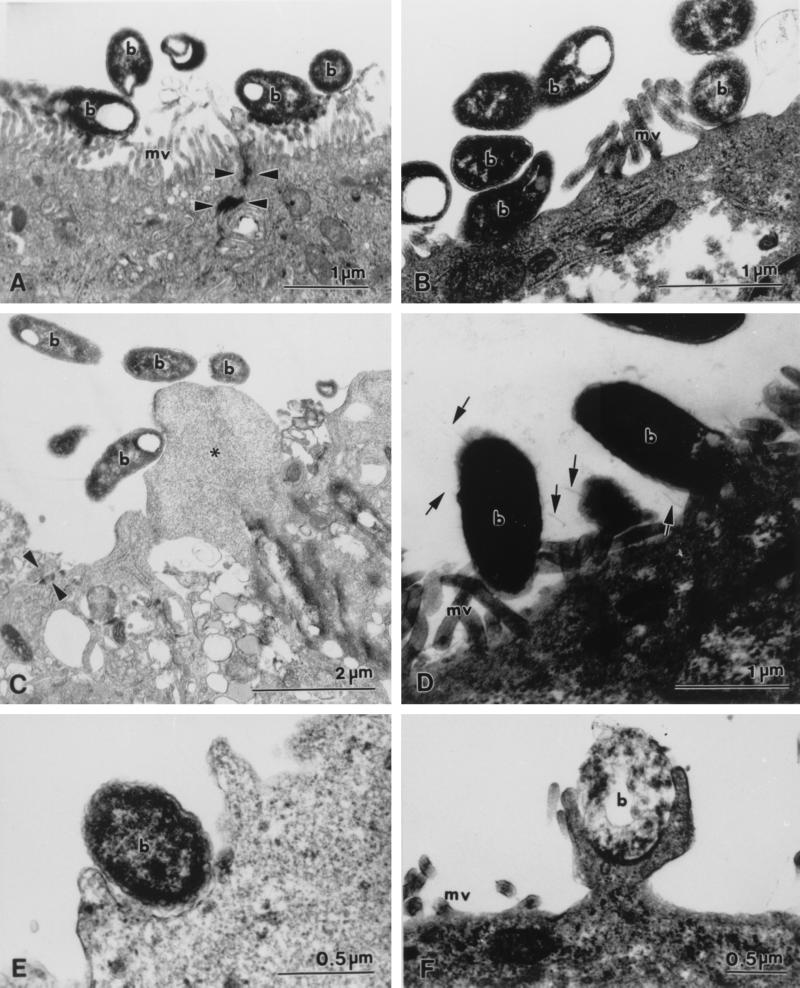

FIG. 3.

Transmission electron micrographs illustrating interactions of P. shigelloides with Caco-2 cells. (A) Bacterial cells (b) adhering to microvilli (mv) at the apical surface of Caco-2 cells. Tight junctions (arrowheads) appear intact. (B) Bacterial cells (b) adhering directly to the apical plasma membrane. (C) Bacterial cells (b) adhering to a cytoplasmic protrusion (asterisk) devoid of organelles. Tight junctions (arrowheads) appear intact. (D) Fimbria-like extensions (arrows) in association with bacterial cells (b) and a Caco-2 cell. (E and F) Pseudopod-like extensions of the Caco-2 cell cytoplasm surrounding bacteria (b).

Fimbria-like extensions were observed for several isolates (ATCC 14029 and 0981) in association with both the bacterial cell and the Caco-2 cell plasma membrane (Fig. 3D). These structures were approximately 500 nm in length and 5 to 10 nm in width.

At 4 h postinfection, five P. shigelloides isolates (0981, Ps13, Ps18, 0967, and 0968) were noted in membrane-bound inclusions within Caco-2 cells. These membrane-bound vacuoles often were comprised of multiple membranes, although single-membrane-bound vacuoles also were seen. Caco-2 cells containing internalized bacteria usually retained their well-defined brush borders. Bacteria were seen closely apposed to Caco-2 cell plasma membranes, both at the apical (microvillus) (Fig. 3B) surface and at the basal surface. Pseudopod-like extensions of cellular cytoplasm often appeared to be engulfing bacteria (Fig. 3E and F); this process occurred at both the apical and the basal surfaces. Bacteria were noted between Caco-2 cells in the monolayer, although desmosomes and tight junctions appeared intact and the plasma membranes of the cells were closely apposed immediately adjacent to the bacteria (Fig. 2C and D).

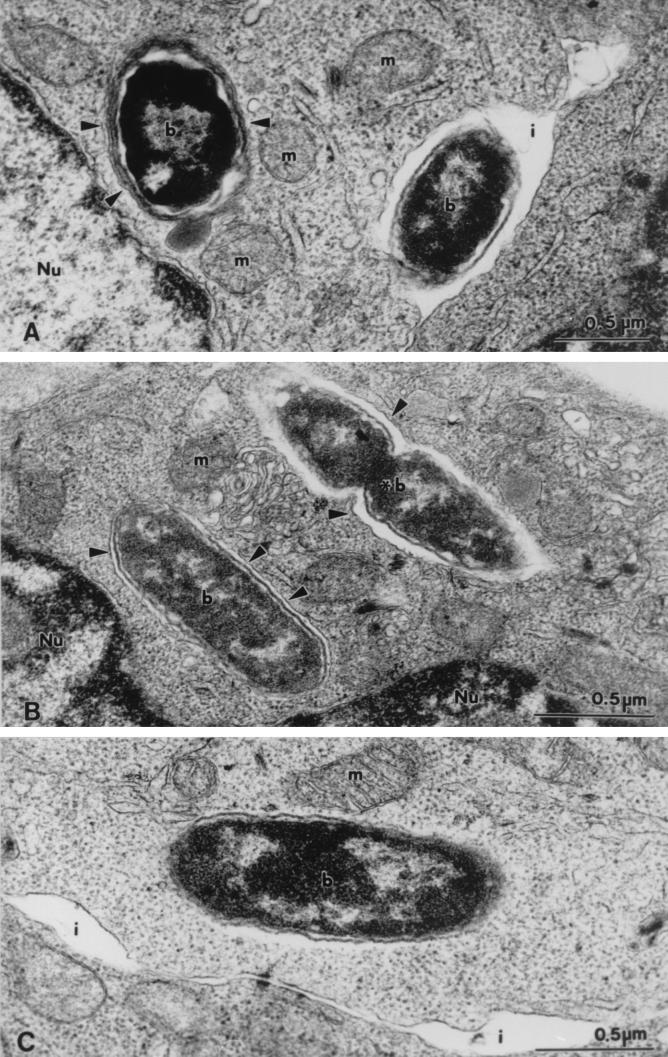

Bacteria were observed to have penetrated Caco-2 cells by 6 to 8 h postinfection for 10 (ATCC 14029, 0967, 0968, 0977, 0981, Ps12, Ps13, Ps18, Ps22, and Ps23) of the 12 isolates of P. shigelloides examined. Caco-2 cells containing large numbers of bacteria within the cytoplasm appeared necrotic. However, at this time, infected Caco-2 cells generally appeared intact and morphologically comparable to those at earlier times. In intact cells infected with P. shigelloides, bacteria were present within single- and multiple-membrane-bound vacuoles in the cytoplasm (Fig. 4A and B). All bacterial cultures, with the exception of isolate Ps23, showed no signs of degeneration within these vacuoles, appearing morphologically indistinguishable from bacteria in the original culture. Indeed, profiles of dividing bacteria were noted within some vacuoles (Fig. 4B). Conversely, some cells of isolate Ps23 found within membrane-bound vacuoles appeared morphologically altered. Cells of several bacterial isolates (ATCC 14029, Ps13, Ps23, and 0981) also appeared free in the cytosol of some Caco-2 cells, apparently devoid of surrounding vacuolar membranes (Fig. 4C).

FIG. 4.

Transmission electron micrographs of P. shigelloides (type strain) within Caco-2 cells. (A) Bacteria (b) within a multiple-membrane-bound vacuole (arrowheads). A bacterial cell also is seen in the interdigital space (i) between adjacent cells. (B) Intracellular bacteria (b) within single-membrane-bound vacuoles (arrowheads). Note the profile of a dividing bacterium (asterisk). (C) Bacterial cell (b) free in the Caco-2 cell cytosol, devoid of surrounding vacuolar membranes. m, mitochondrion; Nu, nucleus.

By 12 h postinfection with all isolates of P. shigelloides assayed, Caco-2 cells showed ultrastructural changes indicative of cellular degeneration and death. Extremely large numbers of bacteria were present in the culture medium. This finding was particularly evident with P. shigelloides isolates ATCC 14029, 0981, 0958, 0967, 0968, and Ps18. Entire Caco-2 cell monolayers had lifted from the culture flask and were suspended in the culture medium. Cellular degeneration also was noted in samples where culture medium was changed at 8 h postinfection to remove most bacteria remaining free in the medium and to supply fresh nutrient medium (data not shown). Numerous bacteria were present within the degenerated cell cytoplasm and, while many bacteria appeared enclosed in membranous structures, the ultrastructural preservation was not sufficient to definitively determine this effect. In contrast, uninfected Caco-2 cells remained intact at this time, and their morphology did not change over the 12-h assay period.

Throughout the time course of infection and with all P. shigelloides isolates used in this study, some Caco-2 cells remained uninfected, while others had large numbers of internally and externally associated bacteria. A clustering effect occurred; Caco-2 cells appeared to be infected by clusters of bacteria rather than an individual bacterium.

Bacteria used as controls in this study were noted to interact with Caco-2 cells, as described in previously published work (12, 27, 38). E. coli (ATCC 25922) did not invade Caco-2 cells, although some bacterial cells were observed adhering to the microvilli and plasma membranes of Caco-2 cells. S. flexneri (NCTC 9722/CSL/70) was observed at the apical and basal Caco-2 cell membranes, and small numbers of intracellular bacteria were seen. Some separation of adjacent Caco-2 cells was noted. L. monocytogenes (UQM278/88) was observed both free in the host cell cytosol and enclosed within membrane-bound vesicles; the main portal of entry appeared to be the apical surface of the Caco-2 cell monolayer.

DISCUSSION

Despite considerable clinical and epidemiological data implying a role for P. shigelloides in gastrointestinal tract infections, the true pathogenic status of this bacterium remains controversial, primarily due to the lack of a suitable animal model and conflicting results from published in vitro virulence assays examining invasiveness and toxin production. The present study has clarified the pathogenic potential of P. shigelloides by focusing on its interactions with eukaryotic host cells and by using an in vitro model more appropriate than those used in previous studies.

Our study has conclusively demonstrated that isolates of P. shigelloides derived from clinical samples and including the type strain (ATCC 14029) are capable of adhering to and entering the human colon carcinoma cell line Caco-2. We present the first transmission electron microscopic documentation of these interactions. The Caco-2 cell line is recognized as the best current in vitro model for studying bacterial interactions (such as adherence and uptake) with the intestinal epithelium (12, 38). Under standard laboratory conditions, this cell line differentiates into well-polarized enterocyte-like cells that are covered by apical microvilli and that are joined by electron-dense tight junctions morphologically identical to those seen between intestinal cells in vivo (30). A number of characteristic enteric cellular markers and enzymes are known to be expressed by this cell line (30). In accordance with these data, we believe that the Caco-2 cell line is eminently suitable for elucidating potential interactions of P. shigelloides with enterocytes, particularly in the absence of an animal model.

Previous studies attempting to ascertain the invasive abilities of P. shigelloides have utilized in vitro model systems with cell lines derived from nonenteric origins (namely, HeLa, derived from human cervical carcinoma, and HEp-2, derived from human carcinoma of the larynx) (2, 6, 15, 25, 26). Bacterial adherence is usually tissue specific, and invasion or internalization may occur only if host cells possess specific receptors mediating such processes (32). These data raise concerns regarding results and conclusions drawn from previous studies, as the cell lines chosen were not representative of the target cells in vivo.

For example, Binns et al. (6) reported that 5 of 16 isolates assayed invaded HeLa cells by a mechanism comparable to that of Shigella sonnei; Herrington et al. (15) did not note invasion with any of five isolates investigated; Olsvik et al. (25) reported that 3 of 11 isolates tested initially demonstrated invasiveness for HeLa cells, but these results could not be confirmed in a duplicate study; and Abbott et al. (2) assayed 16 isolates, including the type strain, but did not find invasion of the HEp-2 cell line.

Additionally, previous studies have relied solely on light microscopy for the evaluation of P. shigelloides invasion. As light microscopy has low resolving power, it is difficult to distinguish between invading or internalized bacterial cells and those that merely have adhered to the host cell surface. To compensate for this problem, after 90 min of exposure to an inoculum of P. shigelloides, the non-membrane-permeating antibiotics gentamicin and kanamycin have been incorporated into assays (2, 6, 15, 25), as they have been used commonly to remove other extracellular bacteria. In conjunction with light microscopy, this technique is assumed to allow only intracellular bacteria to be retained and observed. However, such studies are based on the assumption that P. shigelloides will have entered host cells within 90 min after inoculation. In our study, with transmission electron microscopy, 5 of 12 clinical isolates of P. shigelloides were not observed within the host cell cytoplasm until at least 4 h after inoculation. Therefore, previous studies may have not provided sufficient time for P. shigelloides to be internalized prior to the addition of gentamicin or kanamycin.

Additionally, there is considerable controversy associated with the use of gentamicin for the demonstration of bacterial internalization; there is substantial evidence that gentamicin may adversely affect intracellular bacteria as well as extracellular bacteria (10, 24) and thus may not allow a valid assessment of events. By using transmission electron microscopy, we have eliminated the need to use gentamicin, have achieved high resolution, and thus have provided a more accurate representation of P. shigelloides infection than has been achieved previously.

In several previous studies (2, 6, 15, 25), analysis of the internalization process was assessed using short infection periods, with samples taken over a 3-h time course. Our study suggests that internalization may not have been completed within this time, as we did not note bacteria within Caco-2 cells until at least 4 h postinfection.

As a preliminary strategy and to gain an overall appreciation of the generic interaction of P. shigelloides with Caco-2 cells, light microscopy of Giemsa-stained preparations was performed in this study. In the early stages of infection, light microscopy revealed morphological differences in the interactions of isolates with Caco-2 cell monolayers. Some isolates adhered preferentially at junctions between Caco-2 cells; in contrast, other isolates were uniformly distributed across the monolayer. However, at later times, isolates that were initially uniformly distributed across the monolayer became associated with regions adjacent to cellular junctions. Transmission electron microscopy was adopted to resolve questions of specific interactions and intracellular localization.

Adherence to host cells is a fundamental step in bacterial infection, and many enteropathogens possess surface structures, such as fimbriae, flagella, or a glycocalyx, that facilitate adherence to host cell epithelial surfaces (32). Flagella were noted on all P. shigelloides isolates used in our study, but it is not known if these structures have a role in adherence, as has been suggested for Aeromonas spp. (36). A glycocalyx was not detected on any P. shigelloides isolates in this study, although there is one report (citing unpublished data) of a glycocalyx revealed by transmission electron microscopy (7).

Fimbria-like structures were observed associated with P. shigelloides for the first time in this study. We speculate that these structures may play a role in P. shigelloides adherence to epithelial cells and that stimuli from host cells are required for their expression; they were noted only when bacteria were in close association with host cells and were never resolved in the absence of host cells. It has been documented that Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium requires the presence of host cells to induce the formation of bacterial surface appendages to facilitate adherence (13). Appendages with similar functions may be induced during interactions of P. shigelloides with host cells.

Adherence of P. shigelloides was observed at both the apical and the basal surfaces of Caco-2 cell monolayers in this study. At the apical surface, adherence occurred both directly on the plasma membrane and on microvilli. There was no apparent destruction of the microvillus structure, nor was there evidence of attaching and effacing lesions like those formed during enteropathogenic E. coli adherence (23).

The Caco-2 cell line, like enteric epithelial cells in vivo, forms a continuous monolayer. Cells are connected by highly specialized junction complexes, including tight junctions, desmosomes, and interdigitating cytoplasmic processes (interdigitations), where the lateral membranes of adjacent cells are elaborately interconnected. These structures effectively prevent bacterial movement between adjacent cells and, subsequently, to underlying regions or tissues. Hence, bacterial cells cannot readily gain access to the basal surface of epithelial cells. However, in this study, isolates of P. shigelloides were observed adhering to the basal surface of Caco-2 cell monolayers, and bacterial profiles frequently were observed within interdigitations between Caco-2 cells. Adherence at the apical surface often was observed near cellular junctions. These results suggest that P. shigelloides may travel between cells, through the interdigitations, to gain access to the basal surface of Caco-2 cell monolayers. This route has been suggested for S. flexneri (22) but has not been documented commonly. Access to deeper tissues and capillaries in vivo would allow P. shigelloides to spread to the various extraintestinal sites reported clinically (21). Other enteropathogens, including V. cholerae and Clostridium difficile, have been shown to produce toxins that disrupt tight junctions (28). However, in this study, tight junctions between adjacent Caco-2 cells appeared morphologically intact after infection with P. shigelloides.

Our study is the first to conclusively demonstrate the ability of P. shigelloides to enter and survive in cultured cells of human intestinal origin. The presence of profiles of dividing bacteria within Caco-2 cells indicates that bacterial replication may occur within host cells. Our data suggest that P. shigelloides enters these cells via a phagocytic-like process, as isolates of P. shigelloides were observed within membrane-bound pseudopod-like cytoplasmic extensions and were present within membrane-bound cytoplasmic vacuoles. It is important to note that Caco-2 cells, like their in vivo enteric cell counterparts, are nonphagocytic; hence, bacterial uptake must occur through bacterial signaling mechanisms and manipulation of normal host cell processes.

In this study, P. shigelloides was observed within single-membrane-bound structures, which may correspond to the initial stage of phagocytic uptake. Additionally, bacteria were observed within multiple-membrane-bound vacuoles. The presence of morphologically intact and, occasionally, dividing bacterial cells within these vacuoles suggests that P. shigelloides prevents completion of the normal phagocytic pathway or is capable of resisting the action of lysosomal enzymes. However, further studies are needed to clarify this notion and to determine the origins of the vacuolar membranes.

P. shigelloides was observed free within the Caco-2 cell cytosol, suggesting escape from the intravacuolar compartment. Several other enteropathogenic bacterial species, such as S. flexneri and L. monocytogenes, are known to produce hemolysins that partially degrade phagocytic vacuolar membranes, allowing bacteria to enter the host cell cytosol (3). P. shigelloides may use a similar mechanism to escape from the intravacuolar compartment, as beta-hemolytic activities have been identified previously for a number of P. shigelloides isolates (17).

Although the results of this study must be interpreted cautiously with respect to plesiomonad infections of enterocytes in vivo, the in vitro data conclusively show that isolates of P. shigelloides interact with cells of enteric origin and that such interactions subsequently lead to internalization of the bacteria. Differences in initial patterns of association with Caco-2 cells, consequences of interactions, and the temporal occurrence of internalization events were noted in this study, suggesting that there may be different pathogenic phenotypes for P. shigelloides. Such differences have been clearly established for other enteropathogens, such as E. coli and Campylobacter spp. (14, 23). Such differences would explain the diverse clinical spectrum associated with P. shigelloides infections (7, 9, 16, 20) and also might account for some of the conflicting data from previous experimental assays.

Future research examining the interactions of P. shigelloides and eukaryotic host cells should focus on the mechanisms of these interactions, particularly with respect to molecular signaling. Knowledge obtained from investigating microbe-host cell interactions not only assists in clarifying how different pathogens manipulate host cell processes to initiate disease but also enhances understanding of normal and pathogenic host cell mechanisms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported in part by a Queensland University of Technology (QUT) researcher development grant (9800318, to D. Stenzel and M. O'Brien) and a QUT postgraduate research award (to C. Theodoropoulos).

We thank J. Janda, M. Tandy, and E. Aldova for supplying the P. shigelloides isolates used in this study and M. Jones and T. Walsh for critically reviewing the manuscript. The technical assistance of staff within the QUT Microbiology Section is gratefully acknowledged.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbey S A, Emerinwe N P, Phill E M, Amadi E N. Ecological survey of Plesiomonas shigelloides. J Food Prot. 1993;55:444–446. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-56.5.444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abbott S L, Kokka R P, Janda J M. Laboratory investigations on the low pathogenic potential of Plesiomonas shigelloides. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:148–153. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.1.148-153.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andrews N W, Webster P. Phagolysosomal escape by intracellular pathogens. Parasitol Today. 1991;7:335–341. doi: 10.1016/0169-4758(91)90212-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arai T, Ikejima N, Itoh T, Sakai S, Shimada T, Sakazaki R. A survey of Plesiomonas shigelloides from aquatic environments, domestic animals, pets and humans. J Hyg. 1980;84:203–211. doi: 10.1017/s002217240002670x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bardon J. Evaluation of the pathogenicity of strains of Plesiomonas shigelloides isolated in animals. Vet Med. 1999;44:161–164. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Binns M M, Vaughan S, Sanyal S C, Timmis K N. Invasive ability of Plesiomonas shigelloides. Zentbl. Bakteriol. Hyg. Abt 1 Orig. Reihe A. 1984;257:343–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brenden R A, Miller M A, Janda J M. Clinical disease spectrum and pathogenic factors associated with Plesiomonas shigelloides infections in humans. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10:303–316. doi: 10.1093/clinids/10.2.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Buckley R, Clough E, Warnken W. Plesiomonas shigelloides in Australia. Ambio. 1998;27:253. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clark R B, Janda J M. Plesiomonas and human disease. Clin Microbiol Newsl. 1991;13:49–52. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Drevets D A, Canono B P, Lennen P J M, Campbell P A. Gentamicin kills intracellular Listeria monocytogenes. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2222–2228. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.6.2222-2228.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Duncan H E, Edberg S C. Host-microbe interaction in the gastrointestinal tract. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1995;21:85–100. doi: 10.3109/10408419509113535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gaillard J L, Berche P, Mournier J, Richard S, Sansonetti P J. In vitro model of penetration and intracellular growth of Listeria monocytogenes in the human enterocyte-like cell line Caco-2. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2822–2829. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.11.2822-2829.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ginnochio C C, Olmsted S B, Wells C L, Galan J E. Contact with epithelial cells induces the formation of surface appendages on Salmonella typhimurium. Cell. 1994;76:717–724. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90510-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harvey P, Battle T, Leach S. Different invasion phenotypes of Campylobacter isolates in Caco-2 cell monolayers. J Med Microbiol. 1999;48:461–469. doi: 10.1099/00222615-48-5-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herrington D A, Tzipori S, Robins-Browne R M, Tall B D, Levine M M. In vitro and in vivo pathogenicity of Plesiomonas shigelloides. Infect Immun. 1987;55:979–985. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.4.979-985.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holmberg S D, Farmer J J. Aeromonas hydrophila and Plesiomonas shigelloides as causes of intestinal infections. Rev Infect Dis. 1984;6:633–639. doi: 10.1093/clinids/6.5.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Janda J M, Abbott S L. Expression of hemolytic activity by Plesiomonas shigelloides. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1206–1208. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.5.1206-1208.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson W M, Lior H. Cytotoxicity and suckling mouse reactivity of Aeromonas hydrophila isolated from human sources. Can J Microbiol. 1981;27:1019–1027. doi: 10.1139/m81-159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ljungh A. Bacterial infections of the small intestine and colon. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 1998;14:33–44. doi: 10.1097/00001574-199901000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Miller M A, Koburger J A. Plesiomonas shigelloides: an opportunistic food- and waterborne pathogen. J Food Prot. 1985;48:449–457. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-48.5.449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miller M A, Brenden R A, Wong J D, Abbott S L, Kokka R P, Janda J M. Extraintestinal disease produced by Plesiomonas shigelloides: clinical characteristics and in vitro pathogenicity. J Diarrhoeal Dis Res. 1988;6:103–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mournier J, Vasselon T, Hellio R, Lesourd M, Sansonetti P J. Shigella flexneri enters human colonic Caco-2 epithelial cells through the basolateral pole. Infect Immun. 1992;60:237–248. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.1.237-248.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nataro J P, Kaper J B. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:142–201. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.1.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohya S, Yiong H, Tanabe Y, Arakawa A, Mitsuyama M. Killing mechanism of Listeria monocytogenes in activated macrophages as determined by an improved assay system. J Med Microbiol. 1998;47:211–215. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-3-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olsvik O, Wachsmuth K, Kay B, Birkness K A, Yi A, Sack B. Laboratory observations on Plesiomonas shigelloides strains isolated from children with diarrhea in Peru. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:886–889. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.5.886-889.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pitarangsi C, Echeverria P, Whitmine R, Tirapat C, Formal S, Dammin G J, Tingtalapong M. Enteropathogenicity of Aeromonas hydrophila and Plesiomonas shigelloides: prevalence among individuals with and without diarrhea in Thailand. Infect Immun. 1982;35:666–673. doi: 10.1128/iai.35.2.666-673.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Polotsky Y, Dragunsky K, Kharvkin T. Morphologic evaluation of the pathogenesis of bacterial enteric infections. Crit Rev Microbiol. 1994;20:161–208. doi: 10.3109/10408419409114553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Richard J F, Petit L, Gilbert M, Marvaud J C, Bouchaud C, Popoff M R. Bacterial toxins modifying the actin cytoskeleton. Int Microbiol. 1999;2:185–194. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robards A W, Wilson A J. Basic biological preparation techniques for TEM, section 5.1–5.6. In: Robards A W, Wilson A J, editors. Procedures in electron microscopy. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons Ltd.; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rousset M. The human colon carcinoma cell lines HT-29 and Caco-2: two in vitro models for the study of intestinal differentiation. Biochemie. 1986;68:1035–1040. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(86)80177-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruimey R, Breitmayer V, Elbaze P, Lafay B, Boussemart O, Gauthier M, Christen R. Phylogenetic analysis and assessment of the genera Vibrio, Photobacterium, Aeromonas and Plesiomonas deduced from small rRNA sequences. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1994;44:416–426. doi: 10.1099/00207713-44-3-416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sansonetti P J. Bacterial pathogens, from adherence to invasion: comparative strategies. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1993;182:223–232. doi: 10.1007/BF00579621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sanyal S C, Sarawath B, Sharma P. Enteropathogenicity of Plesiomonas shigelloides. J Med Microbiol. 1980;13:401–409. doi: 10.1099/00222615-13-3-401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schubert R H W. Genus IV. Plesiomonas Habs and Schubert 1962. In: Kreig N R, Holt J G, editors. Bergey's manual of systemic bacteriology. Baltimore, Md: Williams & Wilkins; 1984. pp. 548–550. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schubert R H W, Holz-Bremer A. Cell adhesion of Plesiomonas shigelloides. Z Hyg Umweltmed. 1999;202:383–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thornley J P, Shaw J G, Gryllos I A, Eley A. Virulence properties of clinically significant Aeromonas species: evidence for pathogenicity. Rev Med Microbiol. 1997;8:61–72. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tsukamoto T, Kinoshita Y, Shimada T, Sakazaki R. Two epidemics of diarrhoeal disease possibly caused by Plesiomonas shigelloides. J Hyg. 1978;80:275–280. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400053638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wells C L, van de Westerlo E A, Jechorek R P, Erlandsen S L. Intracellular survival of enteric bacteria in cultured human enterocytes. Shock. 1996;6:27–34. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199607000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.World Health Organization. World health report 2000. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2000. [Google Scholar]