Abstract

Non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis is an uncommon entity that tends to be related to malignancy or rheumatological disorders. The diagnosis is complex and requires a high index of suspicion. It commonly causes recurrent emboli; however, coronary embolism remains an infrequently reported entity. Herein we report a unique case of sequential pulmonary embolism, ST-elevation myocardial infarction (MI), and stroke associated with multi-valvular non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis. The cornerstone of management is treating the underlying cause and anticoagulation therapy. Surgical treatment should be considered in patients with acute heart failure secondary to valvular dysfunction and recurrent thromboembolism despite proper anticoagulation. We have performed an extensive literature search and found nine cases of established antemortem diagnosis of myocardial infarction secondary to non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis, and we reviewed them according to cause, treatment, and outcome.

Keywords: marantic endocarditis, trousseau’s syndrome, stroke, pulmonary embolism, hypercoagulability of malignancy, percutaneous aspiration thrombectomy, coronary embolism, non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis, acute myocardial infarction

Introduction

Cancer is a known cause of hypercoagulability, which can present clinically in various ways, including migratory superficial thrombophlebitis (Trousseau's syndrome), superficial and deep venous thromboembolism, arterial thrombosis, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), and non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis.

Non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE) is a rare entity and tends to be related to malignancy or rheumatologic disorders [1]. NBTE is vegetation on cardiac structures, particularly the valves, consisting of fibrin and platelet aggregates without the presence of an infectious agent. We report a rare case of multivalvular non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis complicated with pulmonary embolism, acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (MI), and stroke. We also reviewed cases of established antemortem diagnosis of myocardial infarction secondary to non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis according to cause, treatment, and outcome.

Case presentation

A 47-year-old woman with a prior history of smoking and psoriasis treated with Enbrel 50 mg once a week but otherwise healthy presented in July 2021 to our health care center with deep venous thrombosis and pulmonary embolism (PE). Anticoagulation therapy was started. Her workup revealed lung adenocarcinoma in the left upper lobe with metastasis to the left hilum, bilateral mediastinal lymph node, and suspected spread to both lungs with no distant metastasis. Due to the impression of a significant illness, she got one cycle of chemotherapy (Cisplatin & Pemetrexed). Later, next-generation sequencing (NGS) testing showed a common pathogenic mutation in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) exon 21 (L858R) and high PLD1. The treatment was changed (according to national guidelines) to targeted therapy with 3rd generation EGFR inhibitor osimertinib at a dose of 80 mg per day.

Four months later, in December 2021, she was readmitted again with new PE and vaginal bleeding despite continued anticoagulation. Her laboratory tests demonstrated disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC). Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) demonstrated vegetation on the septal and the anterior leaflets of the tricuspid valve with severe tricuspid regurgitation (TR) and severe pulmonary hypertension (Figure 1A). IVC filter was inserted. Due to the worsening of her clinical condition with a manifestation of a coagulation disorder, her biological treatment was discontinued, and she was started again on chemotherapy regimen with carboplatin and paclitaxel along with continued treatment of the DIC. Within three weeks, she showed clinical improvement and resolution in terms of DIC parameters. Three months later, TTE demonstrated the disappearance of the vegetation with mild TR and resolution of pulmonary hypertension (Figure 1B). Laboratory workup excluded signs of DIC.

Figure 1. Transthoracic echocardiography.

(A) 4-chambers view showing vegetations on the septal and anterior leaflet of the tricuspid valve (blue arrows). (B) Same view after three months demonstrating the disappearance of the vegetations.

In May 2022, the patient presented with worsening leg pain, and laboratory tests again showed evidence of DIC. She was readmitted for evaluation. Two days later, an electrocardiogram (ECG) was performed due to acute-onset chest pain and showed sinus rhythm with anterior ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (Figure 2). The patient rapidly deteriorated to ventricular fibrillation. She was successfully resuscitated with multiple defibrillator shocks. She was intubated and spontaneous circulation was restored. She was rushed to the cardiac catheterization laboratory, where an urgent coronary angiogram was performed and revealed abrupt occlusion of the proximal part of the left anterior descending artery. She was treated successfully with the implantation of a drug-eluting stent (Video 1) (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Electrocardiogram.

Electrocardiogram showing sinus rhythm with ST-segment elevation in anterior precordial leads (arrows).

Video 1. Coronary angiogram.

Injection to the left coronary system in the cranial right anterior oblique (RAO) view showing abrupt occlusion of the left anterior descending artery with otherwise normal arteries.

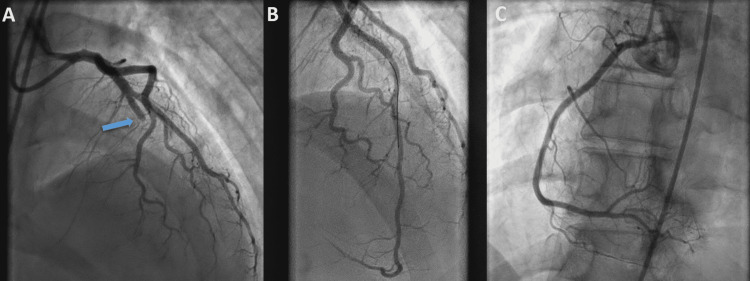

Figure 3. Coronary angiography.

Abrupt occlusion of the middle part of the left anterior descending artery (arrow) causing ST-elevation myocardial infarction (A) with complete revascularization after percutaneous coronary intervention (B). (C) Right coronary angiogram showing a normal artery.

The patient was admitted to the cardiac intensive care unit on mechanical respiratory support. Transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) showed a severely decreased left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), a large eccentric jet of mitral regurgitation (MR), and a small oscillating mass on the posterior leaflet of the mitral valve (Figure 4). There was no evidence of intracardiac thrombus, and there was no evidence of intracardiac shunt after agitated saline injection, excluding paradoxical emboli. Subsequent transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) confirmed severe MR and showed an independently oscillating mobile vegetation measuring 10x12x5 mm (Figure 5) (Video 2) and normal tricuspid valve. No thrombus was seen in the left atrial appendage. Due to her general condition and hemodynamic instability, she was not a candidate for surgical intervention after a multidisciplinary discussion. After weaning from sedation, she woke up with notable right hemiparesis and aphasia. Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed signs of acute infarctions in the left frontoparietal and right parietal hemispheres, more prominent on the left side, secondary to an embolic event (Figures 6, 7).

Figure 4. Transthoracic echocardiography.

(A) Small mass seen on the posterior leaflet of the mitral valve (white arrow) in parasternal long-axis view. (B) Color Doppler echocardiogram in the same view with an eccentric jet of severe mitral regurgitation.

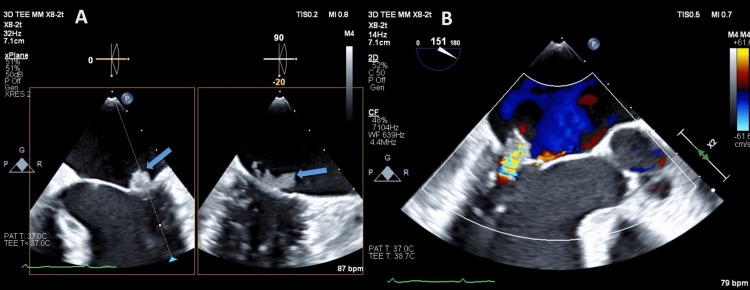

Figure 5. Transesophageal echocardiogram.

(A) Vegetation on the posterior mitral leaflet (arrow) and with an X-Plane view. (B) Color Doppler transesophageal echocardiogram showing severe mitral regurgitation.

Video 2. Transesophageal echocardiogram.

Mid-esophageal view at 0 degrees and X-plane showing the mitral valve with a notable mobile mass attached to posterior leaflet consistent with vegetation.

Figure 6. Magnetic resonance imaging.

(A) Diffusion magnetic resonance imaging demonstrating infarct areas in the left frontoparietal lobe (Blue arrow). (B) Patchy infarct areas in the left and right parietal lobes (red arrow).

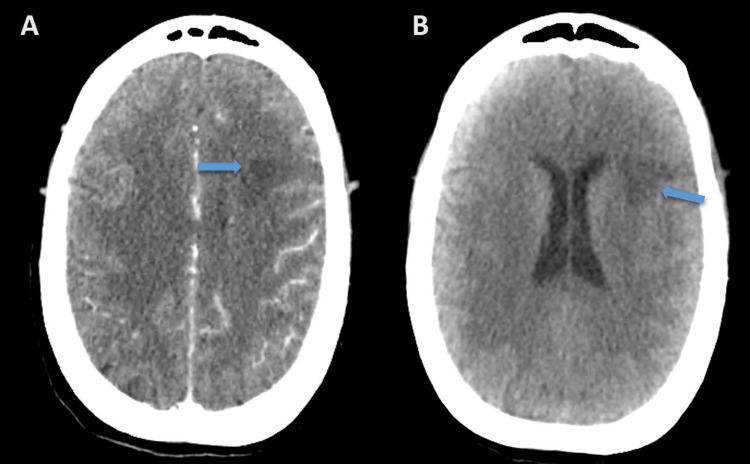

Figure 7. Computed tomography.

The transverse view that demonstrates hypodense areas of encephalomalacia consistence of infarction (arrows) with (A) and without (B) contrast media.

She was empirically treated with antibiotic therapy with a diagnosis of aspiration pneumonia and suspected infective endocarditis (IE).

Physical examination and laboratory tests revealed no peripheral signs of infective endocarditis, and the patient remained afebrile throughout her hospitalization. Blood cultures were sterile, including two sets drawn before antibiotics administration. Throughout her admission, the patient gradually improved neurologically and thus was transferred to the oncology ward.

Unfortunately, her clinical condition deteriorated over the next few days. She developed DIC followed by acute respiratory distress requiring intubation and mechanical ventilation. She went into asystolic cardiac arrest and despite prolonged resuscitation efforts, she passed away with her family at her side. PE or recurrent coronary embolism were thought to be the mechanisms involved in her deterioration.

Discussion

Malignancy is a known cause of hypercoagulability, which can present clinically in various ways, including migratory superficial thrombophlebitis (Trousseau's syndrome), superficial and deep venous thromboembolism, arterial thrombosis, DIC, and non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis (NBTE).

NBTE is a rare condition and tends to be related to malignancy or rheumatologic and autoimmune disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus [1]. NBTE is a vegetation on cardiac structures, particularly the valves, consisting of fibrin and platelet aggregates without the presence of an infectious agent [1]. Zeigler described the deposition of fibrin on cardiac valves and called it thromboendocarditis in 1888 [2]. In 1936, Gross and Friedberg first used the term 'non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis' [3].

Recurrent emboli are common in both IE and NBTE, occurring in up to 50% of patients and typically affecting the central nervous system [2]. Despite frequent systemic embolic phenomena, coronary embolism remains an infrequently reported entity.

In our patient, factors suggesting an embolic source for her coronary event include the lack of atherosclerotic plaque and collateral vessels and the abrupt occlusion of the artery, without evidence of a spontaneous dissection (a common cause of MI in young females), while the other coronary arteries were angiographically normal.

The pathogenesis of NBTE is not fully understood; several mechanisms play a role. The primary factor is local damage mediated by elevated circulating cytokines, a malignancy-associated hypercoagulable state, and subsequent platelet aggregation on subendothelial connective tissue. The preexisting valvular lesion, if present, significantly further enhances this process [1].

Roux et al. [4] in the largest case series of 1210 patients with infective endocarditis, reported that 2.2% developed an acute coronary syndrome (ACS). ACS is mainly caused by coronary embolism and, to less extent, mechanical compression of the vegetation. Coronary embolisms are more frequently observed in patients with aortic valve involvement, most probably due to the proximity between the aortic vegetations and coronary Ostia [4]. To our knowledge, robust data on ACS in NBTE is unavailable.

NBTE should be considered in all cases of DIC and malignancy with systemic emboli. Once suspected, TTE should be performed. The cornerstone of the management of NBTE is treating the underlying cause. Initiation of empirical antibiotic treatment after obtaining blood cultures should be considered. Anticoagulation is warranted if there are no contraindications [1]. Low molecular weight heparin is the suggested treatment for NBTE in the American College of Chest Physicians guidelines [5]. In curable cancers, coagulopathy should be corrected, and a multidisciplinary approach regarding the need and timing of surgery should be considered. No consensus surgical guidelines exist in the management of NBTE. Surgery should be considered in patients with acute heart failure secondary to valvular dysfunction and patients with recurrent thromboembolism despite proper anticoagulation therapy. The decision of surgical intervention in stable patients without complications is complex and requires multidisciplinary discussion.

The patient described in our case was diagnosed with NBTE of the tricuspid valve and pulmonary embolism a few months before her current admission. She was successfully treated with anticoagulation and chemotherapy with the disappearance of the vegetation after three months.

Because of the low incidence of coronary embolism in both IE and NBTE, the data in the literature regarding its management are scarce. Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) should be performed in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) secondary to NBTE. According to the 2017 European Society of Cardiology Clinical Practice Guidelines, routine thrombus aspiration in embolic STEMI is not recommended [6].

A review of the literature revealed many case reports of embolic myocardial infarction in autopsy or clinical circumstances, but only nine cases were found with an established antemortem diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction secondary to NBTE.

Table 1 summarizes these nine cases. Two out of nine patients presented with NSTEMI, and the others were with STEMI.

Table 1. Cases with established antemortem diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction secondary to non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis.

The table summarizes the cases of established antemortem diagnosis of acute myocardial infarction secondary to non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis.

STEMI: S-T segment elevation myocardial infarction, NSTEMI: non-S-T segment elevation myocardial infarction, M: male, F: female, LAD: left anterior descending artery, PLA: postero-lateral artery, PDA: posterior descending artery, RCA: right coronary artery, OM: obtuse marginal, APLA: antiphospholipid syndrome, RA: rheumatic arthritis, SLE: systemic lupus erythematosus.

| Author | Age | Sex | Survival | Type | Artery | Valve affected | Intervention | Other systemic emboli | Underlying cause |

| Gray et al. [7] | 66 | M | No | NSTEMI | PLA and PDA | Mitral | Aspiration | No | Lung cancer |

| Trovato et al. [8] | 29 | M | Yes | STEMI | LAD | Aortic | Balloon | No | APLA |

| Garcia et al. [9] | 46 | F | Yes | STEMI | Distal PLA | Aortic | No intervention | Right anterior and posterior tibial arteries | RA |

| Patel and Elzweig [10] | 66 | F | No | NSTEMI | No culprit | Mitral and aortic | No intervention | Stroke | Pancreatic cancer |

| Kocabay et al. [11] | 26 | M | Yes | STEMI | Distal PDA and distal PLA | Mitral | Balloon | No | SLE |

| Boris et al. [12] | 74 | M | Yes | STEMI | Distal RCA | Mitral and aortic | Aspiration | Subclinical stroke | Biliary adenocarcinoma |

| Tiong et al. [13] | 57 | F | No | STEMI | Distal OM | Aortic | Aspiration | No | Cervical adenocarcinoma |

| Ferlan et al. [14] | 43 | F | Yes | STEMI | Distal PDA | Mitral | No intervention | Stroke | Gastric adenocarcinoma |

| Nagano et al. [15] | 29 | M | Yes | STEMI | Proximal LAD | Aortic | Aspiration and stent | No | Burger's syndrome |

Six of these had survived. In three patients, the mitral valve was involved, in four the aortic valve was involved, and in two patients, both valves were affected. Three of them were treated with aspiration only, two with a balloon, one with stent implantation, and in three patients, no intervention was done due to the distal position of the lesion. In five patients, there was underlying malignancy; in the others, there was evidence of rheumatological diseases (systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, antiphospholipid syndrome, and Burger’s syndrome). In four patients, embolic stroke and other systemic emboli were reported. Surgical removal was done only in two patients.

Conclusions

NBTE is a rare condition and requires a high index of suspicion. Herein we report a unique case of sequential pulmonary embolism, ST-elevation myocardial infarction, and stroke associated with multi-valvular NBTE. We describe an extensive literature review and found nine cases of established antemortem diagnosis of myocardial infarction secondary to NBTE. No established guidelines exist. Each situation requires a multidisciplinary approach to select the best treatment. Treatment of the underlying cause and anticoagulation are the cornerstones of the treatment.

The content published in Cureus is the result of clinical experience and/or research by independent individuals or organizations. Cureus is not responsible for the scientific accuracy or reliability of data or conclusions published herein. All content published within Cureus is intended only for educational, research and reference purposes. Additionally, articles published within Cureus should not be deemed a suitable substitute for the advice of a qualified health care professional. Do not disregard or avoid professional medical advice due to content published within Cureus.

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Human Ethics

Consent was obtained or waived by all participants in this study

References

- 1.Non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis. Asopa S, Patel A, Khan OA, Sharma R, Ohri SK. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2007;32:696–701. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2007.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis: a review. Lopez JA, Ross RS, Fishbein MC, Siegel RJ. Am Heart J. 1987;113:773–784. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(87)90719-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis: classification and general description. Gross L, Friedberg CK. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamainternalmedicine/article-abstract/542036 Arch Intern Med. 1936;58:620–640. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coronary events complicating infective endocarditis. Roux V, Salaun E, Tribouilloy C, et al. Heart. 2017;103:1906–1910. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-311624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy for valvular disease: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Whitlock RP, Sun JC, Fremes SE, Rubens FD, Teoh KH. Chest. 2012;141:0. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-2305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119–177. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis and coronary thrombectomy in a patient with metastatic small cell lung carcinoma. Gray KM, Nguyen B, Baker L, Ahmad M. BMJ Case Rep. 2021;14:0. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-239893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Coronary embolism in a young patient with nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis related to antiphospholipid syndrome. Trovato OC, Vadalà G, Sucato V, et al. Coron Artery Dis. 2021;32:471–472. doi: 10.1097/MCA.0000000000000930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rare association of non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis, myocardial infarction, and acute limb ischemia secondary to rheumatoid arthritis: comprehensive case series with literature review. Garcia RA, Guragai N, Vasudev R, Randhawa P, Habib MG. Cureus. 2021;13:0. doi: 10.7759/cureus.13319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Non-bacterial thrombotic endocarditis: a rare presentation and literature review. Patel MJ, Elzweig J. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:0. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-238585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Acute myocardial infarction due to Libman-Sacks endocarditis. Kocabay G, Alizade E, Pala S. J Emerg Med. 2013;45:91–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.01.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.ST-elevation myocardial infarction due to marantic endocarditis. Adjibodou B, Ayer A, Baeriswyl G, Cook S, Arroyo D. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338133188_ST-elevation_myocardial_infarction_due_to_marantic_endocarditis Cardiovasc Med. 2018;21:166–169. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis with ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated with percutaneous coronary aspiration thrombectomy. Tiong IS, Williams MJ, Perez DJ. Heart Lung Circ. 2013;22:386–389. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2012.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Primary coronary embolism as an unusual manifestation of nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis in a patient with gastric cancer. Ferlan G, Fiorella A, De Pasquale C, Tunzi F. Cardiol Res Pract. 2010;2010:319732. doi: 10.4061/2010/319732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Acute myocardial infarction and limb ischemia as manifestation of nonbacterial thrombotic endocarditis. Nagano N, Morin JF, Joyal D, Rudski L. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;137:1278–1280. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]