Abstract

Medical detection dogs have potential to be used to screen asymptomatic patients in crowded areas at risk of epidemics such as the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. However, the fact that SARS-CoV-2 detection dogs are in direct contact with infected people or materials raises important concerns due to the zoonotic potential of the virus. No study has yet recommended a safety protocol to ensure the health of SARS- CoV-2 detection dogs during training and working in public areas. This study sought to identify suitable decontamination methods to obtain nonpathogenic face mask samples while working with SARS-CoV-2 detection dogs and to investigate whether dogs were able to adapt themselves to other decontamination procedures once they were trained for a specific odor. The present study was designed as a four-phase study: (a) Method development, (b) Testing of decon- tamination methods, (c) Testing of training methodology, and (d) Real life scenario. Surgical face masks were used as scent samples. In total, 3 dogs were trained. The practical use of 3 different decontam- ination procedures (storage, heating, and UV-C light) while training SARS-CoV-2 detection dogs were tested. The dog trained for the task alerted to the samples inactivated by the storage method with a sensitivity of100 % and specificity of 98.28 %. In the last phase of this study, one dog of 2 dogs trained, alerted to the samples inactivated by the UV-C light with a sensitivity of 91.30% and specificity of 97.16% while the other dog detected the sample with a sensitivity of 96.00% and specificity of 97.65 %.

Keywords: Decontamination, Face mask, Medical detection dog, SARS-CoV-2, Zoonotic potential

Introduction

Medical detection dogs have drawn the attention of researchers because of their potential role in screening asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 patients in public places (Williams and Pembroke, 1989; Pirrone et al., 2017; Dickey et al., 2021). Studies report that dogs can detect SARS-CoV-2 from human secretions with greater sensitivity and specificity than do routine diagnostic methods such as RT-PCR and rapid COVID-19 Ag test (Grandjean et al., 2020; Essler et al., 2021; Jendrny et al., 2021). While these results are promising, some health and welfare concerns about people and animals have also emerged (D'Aniello et al., 2021). One of the main concerns about SARS-CoV-2 detection dogs is that different animal species, including dogs, may be infected with this virus, which has a zoonotic potential (Frutos et al., 2020; Shi et al., 2020; Sia et al., 2020). Furthermore, some animal species displayed clinical symptoms in a laboratory environment or in isolation, which brings serious concerns about public health (Shi et al., 2020). Recently, after it SARS-CoV-2 was transmitted from minks to humans (Munnink et al., 2021), millions of minks were culled by the Danish Government. This incident leads to controversial discussions about public health and animal welfare aspects, as well as some concerns about the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission from contaminated materials to dogs and humans (Frutos and Devaux, 2020).

Only a few studies have addressed the precautions needed in order to protect the health of dogs and handlers when training SARS-CoV-2 detection dogs (Essler et al., 2021; Jendrny et al., 2021). There are currently no studies that provide an applicable method for sterilization of training aids or use of these dogs in public areas. Some researchers used sweat swabs as training materials since sweat samples were considered safe for the purpose (Grandjean et al., 2020). However, considering the high mutation rate of SARS-CoV-2 (Nguyen, 2022) and findings of infected sweat glands in humans with SARS-CoV-2 (Liu et al., 2020), serious safety risks may arise for the dogs and handlers during such training where infected samples are used. Due to these concerns, recent studies on SARS-CoV-2 detection dogs mainly focused on alternative samples such as urine (Essler et al., 2021) and used decontamination methods such as chemical or heat inactivation (Essler et al., 2021; Jendrny et al., 2021). However, none of these methods seems to be ideal.

Face-mask sampling is suggested as a noninvasive and accurate method which can be used for the diagnosis of SARS-CoV-2 infection (Williams et al., 2020). So far, only one study has used face masks as a training material (Eskandari et al., 2021) although wearing face masks became a normal human behavior in the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic. Face masks have the potential to be good sample candidates for bio-detection dogs as the masks trap respiratory droplets containing infectious agents as well as volatile organic compounds (VOCs) which are specific to the ongoing infection (Chua et al., 2020).

When using face masks (breath samples) in medical detection dog training, it is important to consider tuberculosis, which is a zoonotic infection caused by the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex (MTBC). Tuberculosis is currently accepted as a global health concern with 10 million cases of tuberculosis recorded in 2019 and being the most common infectious pathogen-related cause of mortality in the human population (Chakaya et al., 2021). Although people are the natural reservoir hosts of M. tuberculosis which is one of the most prevalent and pathologic species of MTBC, animals can get infected by this agent and become sources of infection for humans (Une and Mori, 2007; Posthaus et al., 2011). The agent can be transmitted through the breath and respiratory droplets, just like the SARS-CoV-2 virus (Williams et al., 2020). It is well known that the incidences of dog and human tuberculosis are closely related. For instance, in one study, half of the dogs owned by people who had M. tuberculosis tested positive for the infection (Posthaus et. al., 2011). Although it is uncommon, there have further been reports of M. tuberculosis transmission from dogs to humans (Erwin et al., 2004; Posthaus et al., 2011; Pesciaroli et al., 2014). In previous studies, a co-infection of SARS-CoV-2 and M. tuberculosis has been shown in humans, and both agents could contaminate face-masks with respiratory droplets during coughing (Shah et al., 2022). Although there is no study on the transmission of infectious agents to dogs while sniffing, one should consider that there is a risk for the detection dogs to inhale tuberculosis agents from infected face masks in particular in training conditions where the same masks are used several times. Thus, it is of critical importance to inactivate possible tuberculosis agents in materials including respiratory samples while training detection dogs. It is also significant to know whether these samples from human patients contain any pathogenic mycobacteria. We investigated the possible existence of the MTBC and M. tuberculosis in breath samples of humans used in training of medical detection dogs.

Infection detection dogs for SARS-CoV-2 are assumed to smell the infectious specific VOC profiles released by the cells and pathogens in the body fluids and breath of patients (Dickey and Junqueira, 2021). The VOC profile of the infected sample can change due to several factors, such as environmental odors, sampling procedure, and the sterilization method used for decontaminating the samples (Sakr et al., 2022). Thus, finding a decontamination method which would not change the VOC profiles (odor of the samples) and would be applicable to the field is of great importance. Furthermore, dogs have to be trained and tested in different environments to avoid the context-shift effect and to be prepared for real-life scenarios so that they can be used as early warning detectors in case of disease outbreaks (D'Aniello et al., 2021). All those factors should be taken into account while working with infection detection dogs in order to avoid any false association of the dog's response with the scent. This study aimed to test different decontamination methods to obtain virus free face mask samples while working with SARS-CoV-2 detection dogs.

Materials and Methods

Phase I: Method Development

Sample Collection: Ethical approvals were obtained from the Local Ethics Committee on Animal Experiments of Ankara University (2020-16-142) and from the Ethical Committee for Non-Invasive Medical Treatments of Duzce University (2020/158).

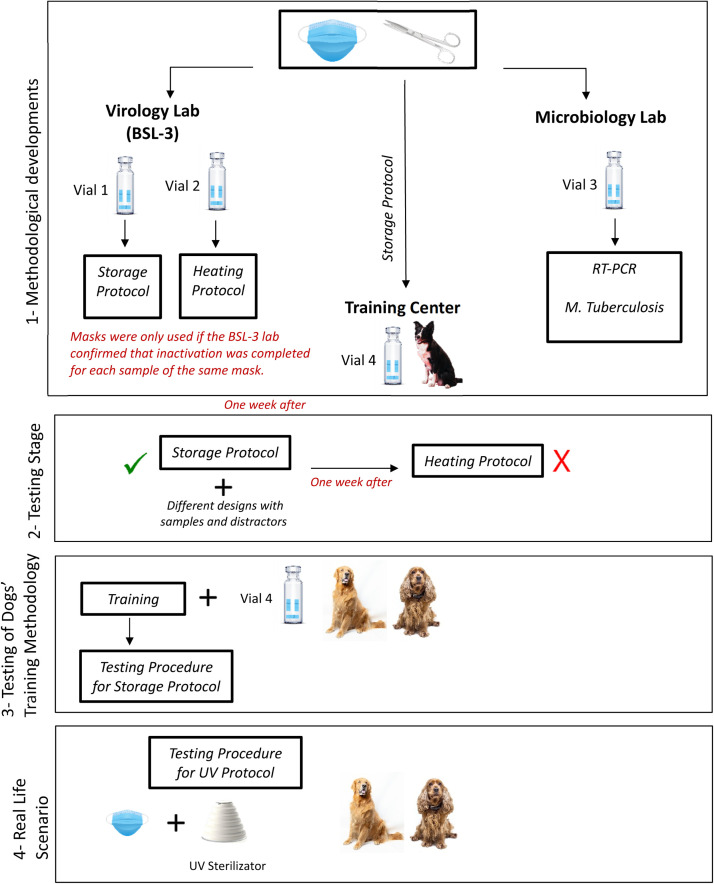

Standard disposable surgical face masks with three layers of protection were collected from patients who were RT-PCR positive and negative for SARS-CoV-2. Before the mask collection, each individual was informed about the protocol, and they signed informed consent. Each patient's demographic information and medical history were taken (Table 2). The patients had to wear face masks for at least 4 hours before the sample collection. Before the masks were collected, the patient was asked to take 10 deep breaths. The mouth region of the mask was cut into 4 equal pieces and placed into 4 glass vials, each of which had a 20 ml capacity. Vials were labeled Vial 1, 2, 3, and 4, written on the vials together with the patient number. All vials were sealed with a manual vial crimper to prevent any gas transfer to the environment. In order to avoid any false positive detection associated with the hospital odors, unused masks kept in the same environment with the patients were also collected into vials as control samples. Vials 1 and 2 were sent to the BSL-3 laboratory, while Vial 3 was sent to the microbiology laboratory. Vial 4 was sent directly to the dog training center (Figure 1 ). Training samples were used only if the samples at the BSL-3 laboratory were confirmed to be virus free.

Table 2.

Demographic information of patients

| Patient number | Gender (Male:M, Female: F) | Age (years) | PCR Result | Chronical Disease | On medication for SARS-Cov | On medication for other reasons | Duration of drug use for SARS-CoV-2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | M | 54 | + | DM | + | + | 7 d |

| 2. | F | 80 | + | H | + | + | 3 d |

| 3. | F | 75 | + | DM | + | + | 9 d |

| 4. | F | 74 | + | H | + | + | 6 d |

| 5. | F | 37 | + | - | + | - | 3 d |

| 6. | M | 29 | + | - | + | - | 3 d |

| 7. | M | 50 | + | DM, H | + | + | 2 d |

| 8. | M | 42 | + | - | + | - | 2 d |

| 9. | M | 78 | + | - | + | - | 5 d |

| 10. | M | 49 | + | - | + | - | 3 d |

| 11. | M | 69 | + | DM | + | + | 5 d |

| 12. | M | 82 | + | H | + | + | 2 d |

| 13. | F | 67 | + | DM | + | + | 2 d |

| 14. | F | 65 | + | DM | + | + | 5 d |

| 15. | F | 72 | + | - | + | - | 3 d |

| 16. | M | 53 | + | H | + | + | 6 d |

| 17. | M | 78 | + | - | + | - | 4 d |

| 18. | F | 88 | + | CVE | + | + | 7 d |

| 19. | F | 85 | + | DM | + | + | 2 d |

| 20. | M | 61 | + | - | + | - | 4 d |

| 21. | F | 80 | + | DM | + | + | 5 d |

| 22. | M | 39 | + | - | + | 4 d | |

| 23. | M | 59 | + | H | + | - | 3 d |

| 24. | M | 52 | + | - | + | - | 6 d |

| 25. | M | 71 | + | H | + | + | 5 d |

| 26. | M | 77 | + | H | + | + | 4 d |

| 27. | M | 66 | + | - | + | - | 2 d |

| 28. | M | 83 | + | - | - | - | - |

| 29. | F | 32 | + | - | - | - | - |

*Abbreviations: DM: Diabetes Mellitus, H: Hypertension, CVE: Cerebrovascular event, d: days

Figure 1.

Protocol of the methodological development and testing stages.

Decontamination Methods: Two different decontamination procedures were used.

Sample Storage Procedure: The storage procedure was used as the primary decontamination method. All masks in Group 1 were exposed to this procedure. Vials were kept at an ambient temperature (15-20°C). The virus load of the samples was tested on a daily basis until the samples were confirmed to be SARS-CoV-2-free. The storage procedure lasted minimum of 7 days and maximum of 10 days.

Heat Inactivation Procedure: The masks in vials 2 were exposed to 60°C for 90 minutes. The virus load of the masks was analyzed after the heat inactivation, and all masks were confirmed to be SARS-CoV-2-free.

Confirmation of SARS-CoV-2 Decontamination in Facemasks: Since SARS-CoV-2 is a BSL-3 pathogen, all biological assays with live SARS-CoV-2 were performed in a certified Physical Containment Level 3 (PC3) Laboratory. Vero E6 (ATCC CRL-1586) cell lines containing an abundance of ACE2 (angiotensin-converting enzyme 2) receptors were also used to detect the decontamination status of test materials. The presence and absence of the viral load in the decontaminated face mask was detected by three blind passages in the Vero E6 cell. The face mask samples collected from patients and subsequently decontaminated by one of the protocols were used in the study. Decontaminated face masks were incubated in air-tight tubes containing viral culture media (viral stock) for 24 hours before Vero cell inoculation. The day before inoculation, 20,000 cells were seeded per well in 24-well cell culture plates and then incubated overnight at 37°C in a humidified, 5% CO2 atmosphere-enriched chamber. On the day of inoculation (when the cell's confluency reached approximately 90%), undiluted viral stock (unknown viral load on masks) was inoculated onto Vero cells in 24-well plates in quadruplicate. The culture is checked for cytopathic effect (CPE) daily, which should be obvious 3-4 days postinoculation (dpi). This protocol was repeated three times, and the samples with no SARS-CoV-2 indicative CPE after the third passage were accepted as SARS-CoV-2-free.

Mycobacterial Investigation (Confirmation of Mycobacterium-Free Masks): Face masks worn by humans and to be used as training samples for dogs were submitted in the vials labeled as Vial 3 to the microbiology laboratory. This was done to reduce the possibility that handlers or dogs would be exposed to TB during training. Following steps were performed for microbial investigation:

Bacterial strains and DNA: Mycobacterium tuberculosis DNA was obtained from National Tuberculosis Reference Laboratory, Public Health Institution of Turkey. Mycobacterium smegmatis strain was obtained from culture collection of Department of Microbiology, Faculty of Veterinary Medicine, Ankara University. M. tuberculosis DNA was used as a positive control in PCR tests, while M. smegmatis was used as a control in bacterial culture performed to confirm inactivation of face mask samples.

Inactivation of face mask samples: Face mask samples in Vials were heat-inactivated by boiling in a water bath for 20 min at 80°C. Bacterial culture was performed in Middlebrook 7H9 broth for confirmation of inactivation (Sabiiti et al., 2019).

DNA extraction from face mask samples: Samples in the form of a small square (square side length is taken as 2 cm approximately) were cut from the center of the face mask samples. These samples were cut into small pieces using a double scalpel in a sterile petri dish. These pieces were added to a sterile eppendorf tube. One hundred eighty micro liter of buffer ATL was added to the samples, and the proteinase K step was incubated at 56°C for 1 h. DNA was purified per manufacturer's [QIAamp DNA Mini Kit (QIAGEN, Germany)] recommendations through a spin column.

Multiplex PCR investigation of gene targets: Multiplex-PCR was performed in a final volume of 20 µl PCR mix containing 10 µl of Multiplex PCR buffer, 0.6 µl of 10 µM concentration of each primers (Table 1 ), 5 µl of extracted DNA and molecular grade water. Presence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and M. tuberculosis were investigated by multiplex PCR using Phusion U Multiplex PCR Master Mix (Thermo Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions. PCR amplification controls were 1 cycle of pre-denaturation by incubation for 30 seconds at 98°C; 30 cycles of denaturation for 10 seconds at 98°C; primer annealing for 30 seconds at 60°C; extension for 30 seconds at 72°C; followed by 1 cycle of final extension for 10 min at 72°C. PCR products were checked on 1.5% (wt/vol) agarose gels.

Table 1.

Primers used for the investigation of presence of M. tuberculosis and MTC in face masks (Chae et al., 2017)

| Primer Sequences | Target organisms | Target gene | Amplicon size (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5’-ATGCCCAAGAGAGAAGCGAATACA-3’ | M. tuberculosis complex | rv0577 | 705 |

| 5’-AATGTCAGCCGGTTCCGCAA-3’ | |||

| 5’-GTGTAGGTCAGCCCCATCC-3’ | M. tuberculosis | RD9 | 369 |

| 5’-GTAAGCGCGTGGTGTGGA-3’ |

Animal Study

Dog: A 3-year-old uncastrated male border collie (Zippo) was trained in this phase. Zippo had no previous history of scent-work training.

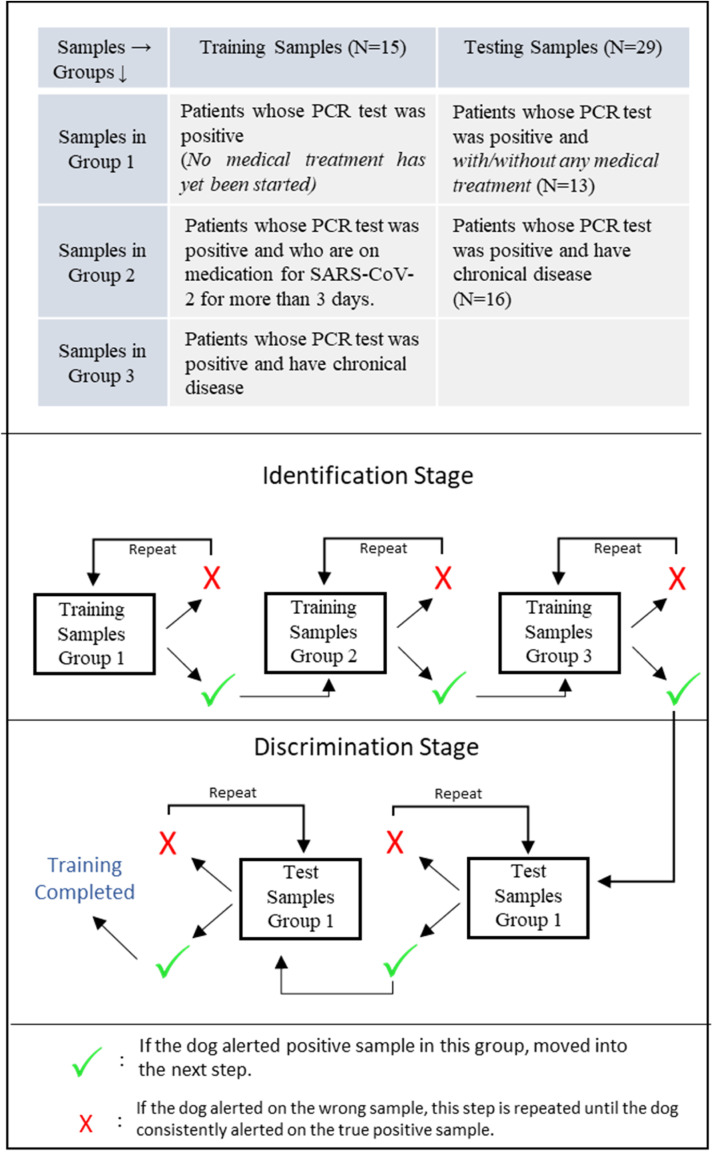

Training Protocol: Mask samples in Group 4 were kept in vials at an ambient temperature until the virology and microbiology teams informed the handler that the samples were safe to be used. Positive samples (n = 15) were divided into 3 groups considering the history of chronic disease and medical treatment of patients (Figure 2 ). The training, which was conducted in an indoor training area, lasted 10 weeks in total. The positive reinforcement method, in which a ball was used as a reward, was used for training. The following stages were conducted:

Figure 2.

Sample groups used in training of the dogs and testing of the sample storage protocol.

Stage 1 (Scent box acclimatization): Only one box used in this stage. A beef-scented dog toy was placed in the scent box. The handler marked a correct response with a clicker as soon as the dog placed his nose in the scent box and then delivered the reward ball. This stage was considered complete when the dog put his nose into the hole without any hesitation.

Stage 2 (Nose-work training): The dog was asked to find the beef-scented toy, which had been placed into one out of 10 boxes. This stage was considered complete when the dog identified the beef-scented box in five consecutive sessions. The location of the beef-scented box changed in each session.

Stage 3 (Identification-1): The same procedure as in the scent box acclimatization (stage 1) was conducted except that a positive mask was placed instead of the scented toy.

Stage 4 (Identification-2): The same procedure as in the nose work training (stage 2) was conducted except that a positive mask was placed instead of the scented toy in this step. The dog was searching 9 boxes instead of 10 boxes since the box which had been used for searching the scented toy was excluded in this step in order to avoid any association with the scent. Positive masks used in the identification steps belonged to patients with SARS-CoV-2 symptoms and PCR-positive results. No medical treatment had yet started for those patients (Figure 2).

Stage 5 (Discrimination): In the discrimination step, one box was always filled with a PCR-positive patients’ mask, whereas others were filled with either control samples, distractors, or both of them. A randomized mix design was used in this step. Namely, different positive masks belonged to different patients with/without a medical history of chronic diseases, and different kinds of control masks and distractors were introduced to dogs in a randomized order. This aimed to eliminate the possibility of the dog choosing the box by chance or unintentional cues. The dog had to stand still with his nose in the hole for five seconds before the handler marked the response with a clicker. The toy was given to the dog as soon as the clicker was activated. After each trial, the dog was led out of the room. The boxes were ventilated and the sample types, as well as locations, were changed. The dog was considered successful if he marked the positive sample in 20 consecutive trials in which the distractors were used.

Control samples were defined as follows: Unused mask, unused mask from the same environment with the patient, empty vial, masks from healthy patients, and masks belonged to healthy patients with seasonal allergy. All control samples were presented in glass vials. Different clothes such as gloves, scarfs and hats of healthy people were used as distractors.

Phase II. Testing of decontamination methods

One week following the completion of the training period, the testing protocol was initiated. The testing protocol lasted 10 days. Four different test trials per day were conducted. Each test trial included 5 consecutive sample presentations. A single-blinded randomized controlled trial design was used; the handler was blinded to the location of the samples. The experimenter, who was unseen by the dog, was standing at the corner of the room during the trials for approval/non approval of the positive sample after the dog's choice.

II.a. Testing of the Sample Storage Protocol: The same indoor training area was used in this step. In total, 200 randomized mask sample presentations were conducted with the dog. In total, 29 different positive masks were used (Figure 2). In each trial, the dog was expected to find the SARS-CoV-2 positive mask in one of the 9 boxes (Figure 2). One positive mask was always present in one of the scent boxes. The same procedure was applied as in stage 5 except that the handler was blinded to the location and status of the samples. Randomized designs with controlled samples and distractors were used in this step.

II.b. Testing of the Heating Protocol: This procedure was carried out to evaluate the ability of the dog to generalize the smell specific to samples exposed to the storage procedure in samples that were heat-treated. One week after the testing of the storage protocol, the heating protocol was tested. Three consecutive sessions were conducted in this step.

Phase III. Testing of the Dog Training Methodology

This phase was conducted in order to test the methodology in different dogs and, further, to assess the dogs’ diagnostic performances in different contexts, such as indoor and outdoor environments.

Dogs: A Labrador retriever (4 years old, female) and an English cocker spaniel (3 years old, female), belonging to the Republic of Turkey Ministry of Interior Gendarmerie Commando Special Operations, were trained. The Labrador retriever (Röfle) was an experienced bomb detection dog whereas the English cocker spaniel (Fırfır) had no previous history of basic obedience training or scent work.

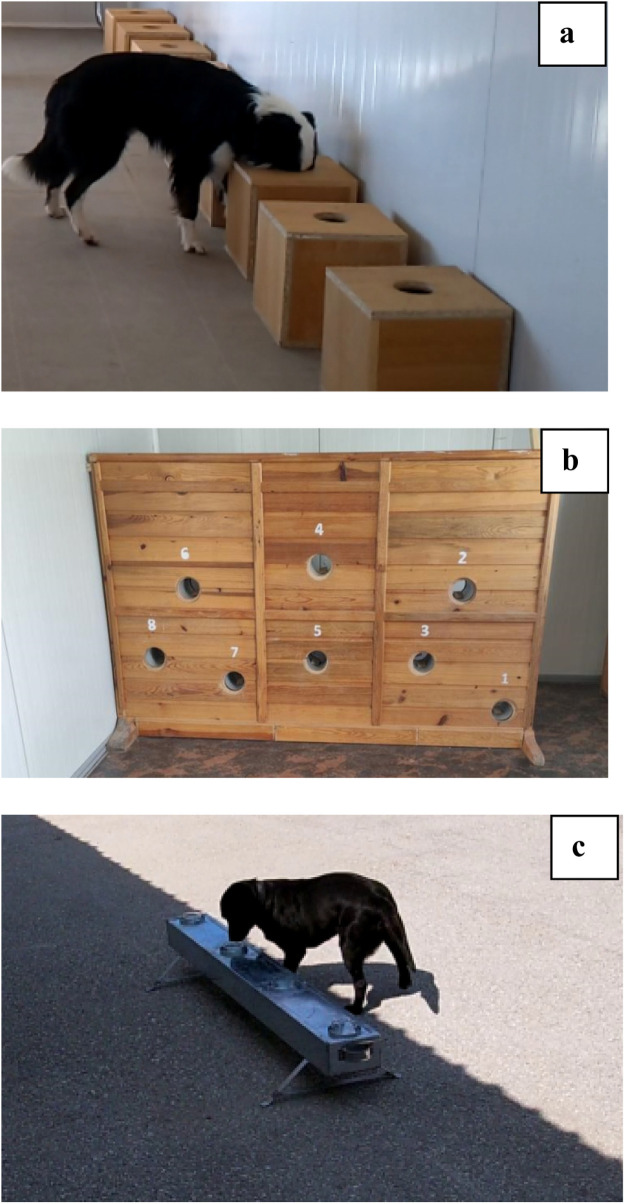

Dog training: The same training samples, which were decontaminated by storage procedure (as in the First Stage) were used for the training of Röfle and Fırfır. The training samples were used in a randomized order during the training. Different scent platforms were used in this phase of the study (Figure 3 ). The scent identification was performed in an indoor environment. After the scent identification was successfully completed, scent discrimination training started. The discrimination work started with wooden scent boxes as in the first phase. When the dog was able to successfully alert to the positive sample among others for 5 consecutive randomized trials, the scent platform was changed to the portable aluminum scent platform. The dogs were trained on the portable scent platform in indoor and/or outdoor environments for discrimination work in the presence of various sounds and people. Dogs were found to be successful after they found the randomly placed positive samples in 20 consecutive trials in which the distractors and control samples were used.

Figure 3.

Scent platforms used in this study (a: Wooden scent boxes, b: Vertical scent platform, c: Aluminum scent platform).

Phase IV: Real-life scenario

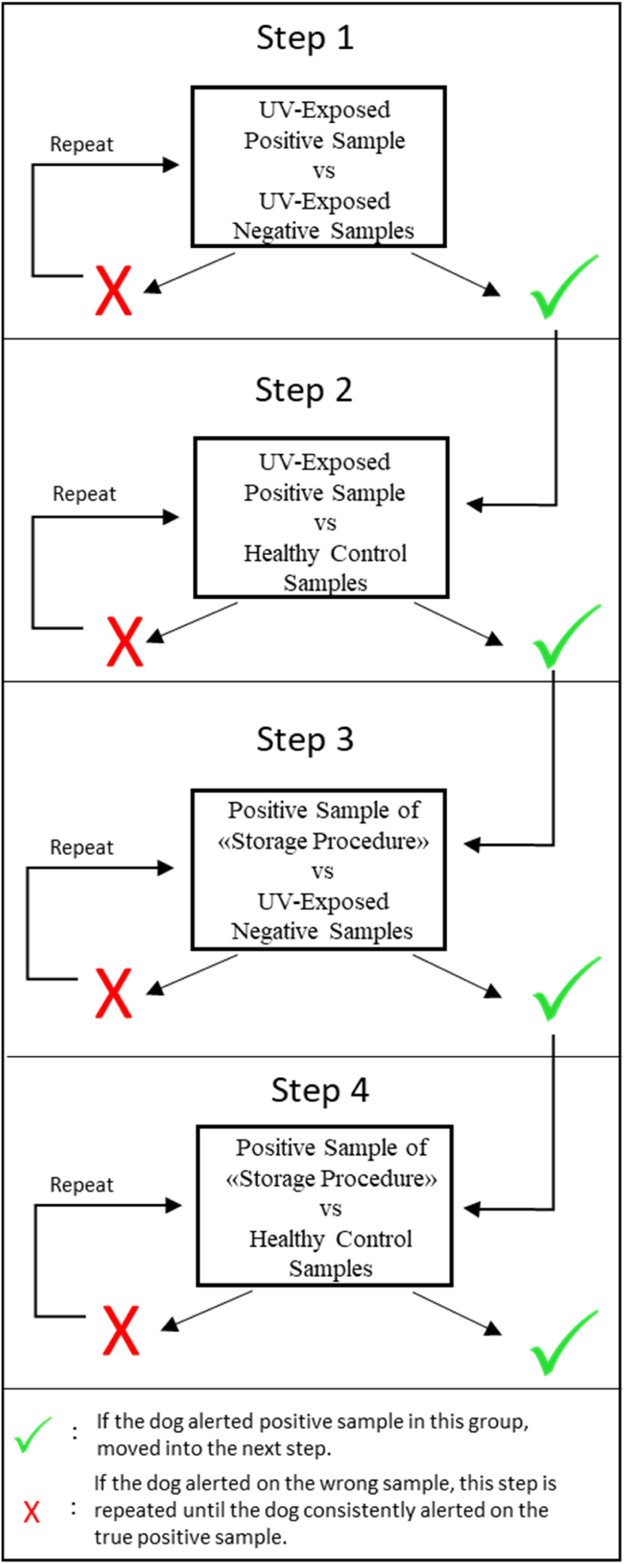

Testing usability of UV-light as a decontamination method: Since the storage procedure was not practical for contemporaneous public screening, UV LED technology-based decontamination method was used in this phase of the study. Because the effectiveness of UV-C light in inactivating SARS-CoV-2 has already been demonstrated in various studies (Hitchman, 2020), no further testing of this method's inactivation performance was performed.

A SINED UV portable sterilizer (Mahaton Fold Tableware Sterilizor) consisting of a top emitter of UV-C light was used to inactivate the masks. The Sterilizer featured a 10mW high-power, deep UV LED lamp for disinfection of surfaces. In order to test the possible effect of UV light on the scent, the training samples were exposed to UV light for 90 seconds. Four consecutive test trials were conducted for each dog (Figure 4 ) previously trained on the samples that were not UVC sterilized. Since no hesitation and/or false alert was detected in dogs, training sessions with UV-exposed masks were initiated. In total, 621 UV-exposed face masks were introduced to the dogs within a one-month period in different indoor and outdoor environments for preparing the dogs for a real-life scenario.

Figure 4.

Test trials for testing the usability of UV-light as a decontamination method.

Testing the dogs’ performances in a real-life scenario: Two dogs were brought to the novel outdoor area at the Ministry Department to demonstrate a real-life scenario. Staff (n = 43) had to give a PCR test regularly according to SARS-CoV-2 regulations. Thus, all the masks collected from the staff were negative samples. The UV-exposed face masks of the staff working at the Ministry Departments were tested by the dogs. In total, 43 consecutive trials were conducted with the dogs to test their performances in real-life scenarios. In each presentation, one unknown mask, two controls and one positive sample were presented to the dogs.

Statistical Analysis: The statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 22.0. The accuracy (Acc = TP + TN / TP + TN + FP + FN), sensitivity (Se = TP / [TP + FN]) and specificity (Sp = TN / [TN + FP]) were calculated according to Trevethan (2017).

Results

Phase I: Methodological Development

Storage and heating procedures: Investigation of virus load in the face masks confirmed that the masks were SARS-CoV-2 free after both decontamination procedures. Both decontamination procedures were found to be successful in obtaining non-pathogenic face masks.

Microbiological investigation of face masks: In the cultivated samples, there was no evidence of mycobacterial growth. PCR analysis revealed no evidence of MTBC or M. tuberculosis DNA in face mask samples. Thus, before the training, it was established that all masks were Mycobacterium free.

Phase II: Testing of Decontamination Methods

Storage procedure: In total, 200 randomized sample presentations were conducted during the first testing phase. The detection accuracy of Zippo was calculated as 98.73% with a sensitivity of 100% (95% CI: 86.77%-100%) and specificity of 98.28% (95% Confidence Interval (CI): 95.04%-99.64%). Positive Predictive Value (PPV) and Negative Predictive Value (NPV) were assessed as 95.44% and 100%, respectively (Table 3 ).

Table 3.

Diagnostic and sample detection performance of Zippo during testing the Sample Storage Protocol-Phase 1

| Diagnostic Performance | Value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 100.00% | 86.77% to 100.00% |

| Specificity | 98.28% | 95.04% to 99.64% |

| Positive Predictive Value (*) | 95.44% | 87.20% to 98.47% |

| Negative Predictive Value (*) | 100.00% | |

| Accuracy (*) | 98.73% | 96.03% to 99.79% |

| Sample Detection Performance | ||

| True Positive | 26 | |

| False Positive | 3 | |

| True Negative | 171 | |

| False Negative | 0 | |

Heating procedure: While testing the performance of Zippo with the heating protocol, the dog alerted the heated sample after smelling all boxes several times. The dog behaved in a confused manner until targeting the heated mask in the box in the first session. He smelled the target and the nearby boxes constantly and displayed hyperventilation before finally alerting to the heated sample. He found the mask in his second trial without any hesitation. He also targeted the heated sample when the control sample (heated vial) was presented in a different box. Considering the reaction of the dog, no further steps were conducted in order to avoid any disassociation with the possibly changed odor after the heating procedure.

Phase III: Testing the methodology with other dogs

Training success: The training methodology was found to be applicable to the infection detection dog training as both dogs successfully completed the training steps within 1 month period.

Phase IV: Real-Life Scenario

Testing usability of UV-light as a decontamination method: In total, 621 sample presentations were conducted for both dogs. The diagnostic accuracy of Firfir was calculated as 95.61% with a sensitivity of 91.30% (95% CI: 71.96%-98.93%) and specificity of 97.16% (95% CI: 95.49%-98.34%). PPV and NPV were assessed as 92.05% and 96.87%, respectively (Table 4 ). The diagnostic accuracy of Rofle was calculated as 95.59% with a sensitivity of 96.00% (95% CI: 79.65%-99.90%) and specificity of 97.65% (95% CI: 96.09%-98.71%). PPV and NPV were assessed as 93.64% and 98.54%, respectively (Table 4).

Table 4.

Diagnostic and Sample Detection Performance of Firfir and Rofle during testing usability of UV-light as a decontamination method- Phase IV

| Dogs’ Name → | Firfir |

Rofle |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diagnostic Performance ↓ | Value | 95% CI | Value | 95% CI |

| Sensitivity | 91.30% | 71.96% to 98.93% | 96.00% | 79.65% to 99.90% |

| Specificity | 97.16% | 95.49% to 98.34% | 97.65% | 96.09% to 98.71% |

| Positive Predictive Value (*) | 92.05% | 87.70% to 94.95% | 93.64% | 89.72% to 96.14% |

| Negative Predictive Value (*) | 96.87% | 89.18% to 99.15% | 98.54% | 90.84% to 99.78% |

| Accuracy (*) | 95.61% | 93.68% to 97.08% | 97.21% | 95.59% to 98.36% |

| Sample Detection Performance | Firfir | Rofle | ||

| True Positive | 21 | 24 | ||

| False Positive | 17 | 14 | ||

| True Negative | 581 | 582 | ||

| False Negative | 2 | 1 | ||

Testing the performances of the dogs in real life: In total, 43 sample presentations were conducted for each dog in a public place. The diagnostic accuracy of the dogs was calculated as 100%, with 100% sensitivity (95% CI: 91.78%-100%) and 100% specificity (95% CI: 91.78%-100%).

Discussion

This study was conducted as a 4-phase study. The main objective was to investigate the effectiveness of different decontamination methods to obtain nonpathogenic samples which can be used in SARS-CoV-2 detection dog work. Although some studies claimed that decontamination is not necessary for SARS-CoV-2 detection dog training (Grandjean et al., 2020; Eskandari et al., 2021), most researchers highlighted the significance of safety concerns since there is a potential risk for transmission from infected material to the dog and/or handler (De Souza Barbossa et al., 2022; Essler et al., 2022). In the first phase of this study, two different decontamination procedures, storage and heating, were conducted to obtain virus-free samples. Although both procedures were found to be effective in decontaminating the face masks, the storage procedure was found to be more usable in training than the heating procedure. In medical detection dog training, diseases are assumed to be detected by smelling the disease-specific odor from the body fluids and/or breath samples of the patients (Schmidt and Podmore, 2015; Jendrny et al., 2021). Odor identification is suggested to be related to VOCs released as a result of metabolic changes in the body and act as a fingerprint of the disease (Abd El Qader et al., 2015). In this study, all face masks including breath samples of the patients were collected in air-tight sealed glass vials that are normally used in chemical analysis. As this is a standard methodology for VOC analysis (Soini et al., 2010), one can presume that VOC profiles would not change in the storage procedure. Thus, this procedure does not cause any change in VOC (odor profiles), at least within the limits of what the dog can perceive. Even though it has been reported that the odor profiles were maintained after heat inactivation (Essler et al., 2021), in our study, the dog hesitated to alert the heated sample in the first trial. Considering the success rate and alerting speed of the dog during the storage procedure, his hesitation after the heating procedure seemed to be related to odor change. After recognizing the odor sample, the dog could easily alert the heated sample in the second trial which suggested that he formed a generalization to the heated sample after the first trial. This finding supports the idea that once the dogs are trained for a specific odor, they are able to adapt to other inactivation procedures (Essler et al., 2021). In this study, the training methodology was tested with different dogs with different handlers in different training environments. All dogs successfully completed the training within the one-month period, which confirms the applicability of the methodology to the SARS-CoV-2 detection dog training.

In the last phase of this study, a different decontamination procedure (UV-inactivation) was carried out. The performances of two dogs, which had been trained with the masks exposed to storage procedure, were tested with UV-exposed face masks. In contrast to the heating procedure test, both dogs showed no hesitation and/or confused reaction in the first trial. The diagnostic accuracy of both dogs was measured as “excellent” considering the diagnostic criteria by Šimundić (2009) after one month of training for real-life scenarios. To our knowledge, this constitutes the first example of an application of a fast decontamination method for samples presented to infection detection dogs. This study demonstrated that UV-exposed face masks can be used as safe and non-invasive samples while using medical detection dogs for detecting infectious diseases. Since the effectiveness of UV light in inactivating SARS-CoV-2 was already shown in different studies (Hitchman, 2020; Heilingloh et al., 2020), no further examination was conducted to test the inactivation performance of this method. Further research, however, investigating the effect of different UV-light types, different application times, and different sample materials on inactivation would be beneficial.

This study met important criteria for success in transferring the methodology to the field by providing a number and diversity of samples during testing (Elliker et al., 2014). The dogs trained in this study were able to discriminate between positive and negative samples collected from the same hospital environment. Thus, the possibility of disassociation of the hospital odor was eliminated. All of the dogs were also able to alert samples belonging to patients from different groups, including patients with chronic diseases (diabetes mellitus, hypertension, et cetera) who were taking medication. Although these kinds of diseases may change the odor of the body fluids and breath, they do not seem to interfere with the detection success of the dog. During the testing procedure, the dogs did not give false alerts to any of the samples collected from individuals with chronic diseases. These findings also show that the dogs can be trained by face-mask belonging to SARS-CoV-2 patients regardless of their disease states or other medical conditions. Although field studies with SARS-CoV-2 dogs were already conducted (Gupta et al., 2021; Sakr et al., 2021), those studies had certain limitations. The dogs either worked in close contact with humans by sniffing their armpits (Sakr et al., 2021) which may not be the desired method in particular for fearful people or they sniffed body secretions such as urine which may not be practical to be collected in the field. In this study, detection rates of the dogs during training and testing were seemingly high. Thus, one may suggest that face masks are good training samples that can easily be collected from patients in the hospital and also from people in public places such as schools, airports, and concerts.

In this study, the presence of M. tuberculosis and other M. tuberculosis complex members in the mask samples was investigated by the PCR and neither of these agents were found in any of the mask samples. Despite the fact that M. tuberculosis was not discovered in any of the masks used in this study, it can be crucial to test breath samples for Mycobacterium and use only free samples when training detection dogs, particularly in countries of South-East Asia, Africa, and the Western Pacific considering the high prevalence of the disease in those regions (Chakaya et al., 2021). If breath samples are taken, it is also important to routinely test the dogs for tuberculosis.

Although results of this study are promising, one should be careful to interpret the data obtained from this study. The main limitation of this study was that since it was a pilot study, it had a small sample size. Therefore, further studies with larger sample size are necessary to generalize the results of this study. The other limitation was that the inactivation of viruses with the UV-C method was not tested within the frame of this study. Future studies investigating the efficacy of different application times of the same method and different UV-systems on virus inactivation are needed to apply this technique for decontamination in the field.

Conclusions

This study shows that decontaminated face masks can be used to train SARS-CoV-2 detection dogs. Storage and UV light can be used to inactivate viruses in samples before training. UV light can also be used as a fast inactivation method in the field. The findings of this study are important to attract attention to safety practices while training dogs to detect infectious diseases which have zoonotic potential.

Authorship statement

The idea for the paper was conceived by Y.S.D. The design for sample collection and introduction were planned and applied by Y.S.D, G.K., A.D.H., H.O., M.A., N.I., H.C., F.E, I.S., and A.O. The inactivation procedure for SARS-CoV-2 was planned and applied by Y.S.D, B. S., G.K., A.D.H., H.O., E.O., D.A. and A. O. The inactivation procedure for M. tuberculosis was planned by B.S, B. B., and I.S. The analysis for M. tuberculosis was conducted by B.S and B. B. The training procedure was designed by Y.S.D, G.G.P., B.S., S.I., D.A., and T.O. The experiments with dogs were performed by B.S., G.K., T.O, H.O., and D.A., and supervised by Y.S.D. The data were analyzed by Y.S.D, E.O., and S.I. The paper (original draft) was written by Y.S.D, B.S., G.K., H.O., and B.S. The paper was reviewed and edited by A.D.H., G.G.P, and A.O. The final article was approved by all authors.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Turkish Scientific and Technological Research Council (Project number: 128O198). The authors express their gratitude to the Republic of Turkey Ministry of Interior Gendarmerie Commando Special Operations Command for their technical support. Authors are thankful to Yusuf Ziyaddin Cavlak (Gendarmerie Commando Special Public Security Commander Brigadier), Faruk Kasar (Gendarmerie Commando Special Public Security Deputy Commander), Mehmet Gördü (Gendarmerie Senior Sergeant Canine Unit Company Commander), Hakan Gül (Gendarmerie Sergeant, Dog handler), Cansu Koru and Simge Yazan for their valuable inputs and support to this study.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Abd El Qader A., Lieberman D., Shemer Avni Y., Svobodin N., Lazarovitch T., Sagi O., Zeiri Y. Volatile organic compounds generated by cultures of bacteria and viruses associated with respiratory infections. Biomed Chromatogr. 2015;29(12):1783–1790. doi: 10.1002/bmc.3494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chae H., Han S.J., Kim S.-Y., Ki C.-S., Huh H.J., Yong D., Koh W.-J., Shin S.J. Development of a one-step multiplex PCR assay for differential detection of major Mycobacterium species. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2017;55:2736–2751. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00549-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakaya J., Khan M., Ntoumi F., Aklillu E., Fatima R., Mwaba P., Kapata N., Mfinanga S., Hasnain S.E., Katoto P.D.M.C., et al. Global Tuberculosis Report 2020–Reflections on the Global TB burden, treatment and prevention efforts. Int J Infect Dis. 2021;113:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2021.02.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua M.H., Cheng W., Goh S.S., Kong J., Li B., Lim J.Y., Mao L., Wang S., Xue K., Yang L. Face masks in the new COVID-19 normal: materials, testing, and perspectives. Research. 2020;2020:1–40. doi: 10.34133/2020/7286735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Aniello B., Pinelli C., Varcamonti M., Rendine M., Lombardi P., Scandurra A. COVID sniffer dogs: technical and ethical concerns. Front. Vet. Sci. 2021;8:1–5. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.669712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza Barbosa A.B., Kmetiuk L.B., de Carvalho O.V., Brandão A.P.D., Doline F.R., Lopes S.R.R.S., Meira D.A., de Souza E.M., da Silva Trindade E., Baura V., Barbosa D.S. Infection of SARS-CoV-2 in domestic dogs associated with owner viral load. Res. Vet. Sci. 2022;153:61–65. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2022.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickey T., Junqueira H. Toward the use of medical scent detection dogs for COVID-19 screening. Int. J. Osteopath. Med. 2021;121:141–148. doi: 10.1515/jom-2020-0222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliker K.R., Sommerville B.A., Broom D.M., Neal D.E., Armstrong S., Williams H.C. Key considerations for the experimental training and evaluation of cancer odour detection dogs: lessons learnt from a double-blind, controlled trial of prostate cancer detection. BMC Urol. 2014;14:1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2490-14-22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erwin P.C., Bemis D.A., Mawby D.I., McCombs S.B., Sheeler L.L., Himelright I.M., Halford S.K., Diem L., Metchock B., Jones T.F., Thomsen B.V. Mycobacterium tuberculosis transmission from human to canine. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2004;10(12):2258. doi: 10.3201/eid1012.040094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskandari E., Ahmadi Marzaleh M., Roudgari H., Hamidi Farahani R., Nezami-Asl A., Laripour R., Aliyazdi H., Dabbagh Moghaddam A., Zibaseresht R., Akbarialiabad H. Sniffer dogs as a screening/diagnostic tool for COVID-19: a proof of concept study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021;21:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-05939-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Essler J.L., Kane S.A., Nolan P., Akaho E.H., Berna A.Z., Deangelo A., Berk R.A., Kaynaroglu P., Plymouth V.L., Frank I.D. Discrimination of SARS-CoV-2. infected patient samples by detection dogs: a proof of concept study. PLoS One. 2021;16 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0250158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frutos R., Devaux C. Mass culling of minks to protect the COVID-19 vaccines: is it rational? New Microbes New Infect. 2020;38 doi: 10.1016/j.nmni.2020.100816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean D., Sarkis R., Lecoq-Julien C., Benard A., Roger V., Levesque E., Bernes-Luciani E., Maestracci B., Morvan P., Gully E. Can the detection dog alert on COVID-19 positive persons by sniffing axillary sweat samples? A proof-of-concept study. PLoS One. 2020;15 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0243122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta P., Pushkala K. Corona (Sars-Cov2) and dogs: foes and friends. Cell Tissue Res. 2021;21(1):7025–7028. [Google Scholar]

- Heilingloh C.S., Aufderhorst U.W., Schipper L., Dittmer U., Witzke O., Yang D., Zheng X., Sutter K., Trilling M., Alt M., Krawczyk A. Susceptibility of SARS-CoV-2 to UV irradiation. Am. J. Infect. Control. 2020;48(10):1273–1275. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2020.07.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hitchman M.L. A new perspective of the chemistry and kinetics of inactivation of COVID-19 coronavirus aerosols. Future Virol. 2020;15:823–835. doi: 10.2217/fvl-2020-0326. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jendrny P., Twele F., Meller S., Schulz C., Von Köckritz-Blickwede M., Osterhaus A.D.M.E., Ebbers H., Ebbers J., Pilchová V., Pink I. Scent dog identification of SARS-CoV-2 infections in different body fluids. BMC Infect. Dis. 2021;21:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s12879-021-06411-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Li Y., Liu L., Hu X., Wang X., Hu H., Hu Z., Zhou Y., Wang M. Infection of human sweat glands by SARS-CoV-2. Cell Discov. 2020;6(1):1–3. doi: 10.1038/s41421-020-00229-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munnink O.B.B., Sikkema R.S., Nieuwenhuijse D.F., Molenaar R.J., Munger E., Molenkamp R., van der Spek P.Tolsma, Rietveld A., Brouwer M., et al. Transmission of SARS-CoV-2 on mink farms between humans and mink and back to humans. Science. 2021;371(6525):172–177. doi: 10.1126/science.abe5901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen K.V. Containing the spread of COVID-19 virus facing to its high mutation rate: approach to intervention using a nonspecific way of blocking its entry into the cells. Nucleo. Nucleot. Nucl. 2022;41(8):778–814. doi: 10.1080/15257770.2022.2071937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pesciaroli M., Alvarez J., Boniotti M., Cagiola M., Di Marco V., Marianelli C., Pacciarini M., Pasquali P. Tuberculosis in domestic animal species. Res. Vet. Sci. 2014;97:S78–S85. doi: 10.1016/j.rvsc.2014.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirrone F., lbertini M. Olfactory detection of cancer by trained sniffer dogs: a systematic review of the literature. J. Vet. Behav. 2017;19:105–117. doi: 10.1016/j.jveb.2017.03.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Posthaus H., Bodmer T., Alves L., Oevermann A., Schiller I., Rhodes S.G., Zimmerli S. Accidental infection of veterinary personnel with Mycobacterium tuberculosis at necropsy: a case study. Vet. Microbiol. 2011;149(3-4):374–380. doi: 10.1016/j.vetmic.2010.11.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabiiti W., Azam K., Esmeraldo E., Bhatt N., Rachow A., Gillespie S.H. Heat inactivation renders sputum safe and preserves Mycobacterium tuberculosis RNA for downstream molecular tests. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2019;57:e01778-18. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01778-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakr R., Ghsoub C., Rbeiz C., Lattouf V., Riachy R., Haddad C., Zoghbi M. COVID-19 detection by dogs: from physiology to field application—a review article. Postgrad Med J. 2022;98(1157):212–218. doi: 10.1136/postgradmedj-2020-139410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt K., Podmore I. Current challenges in volatile organic compounds analysis as potential biomarkers of cancer. J Biomark. 2015;2015:1–16. doi: 10.1155/2015/981458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah T., Shah Z., Yasmeen N., Baloch Z., Xia X. Pathogenesis of SARS-CoV-2 and Mycobacterium tuberculosis coinfection. Front. Immunol. 2022;13 doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.909011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi J., Wen Z., Zhong G., Yang H., Wang C., Huang B., Liu R., He X., Shuai L., Sun Z. Susceptibility of ferrets, cats, dogs, and other domesticated animals to SARS–coronavirus 2. Science. 2020;368:1016–1020. doi: 10.1126/science.abb7015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sia S.F., Yan L.-M., Chin A.W., Fung K., Choy K.-T., Wong A.Y., Kaewpreedee P., Perera R.A., Poon L.L., Nicholls J.M. Pathogenesis and transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in golden hamsters. Nature. 2020;583:834–838. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2342-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Šimundić A.M. Measures of diagnostic accuracy: basic definitions. EJIFCC. 2009;19(4):203. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soini H.A., Klouckova I., Wiesler D., Oberzaucher E., Grammer K., Dixon S.J., Xu Y., Brereton R.G., Penn D.J., Novotny M.V. Analysis of volatile organic compounds in human saliva by a static sorptive extraction method and gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. J. Chem. Ecol. 2010;36:1035–1042. doi: 10.1007/s10886-010-9846-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevethan R. Sensitivity, specificity, and predictive values: foundations, pliabilities, and pitfalls in research and practice. Public Health Front. 2017;5:307. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2017.00307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Une Y., Mori T. Tuberculosis as a zoonosis from a veterinary perspective. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2007;30:415–425. doi: 10.1016/j.cimid.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams C.M., Abdulwhhab M., Birring S.S., De Kock E., Garton N.J., Townsend E., Pareek M., Al-Taie A., Pan J., Ganatra R., Stoltz A.C., Haldar P., Barer M. Exhaled Mycobacterium tuberculosis output and detection of subclinical disease by face-mask sampling: prospective observational studies. Lancet. 2020;20:607–617. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30707-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams H., Pembroke A. Sniffer dogs in the melanoma clinic? Lancet. 1989;333(8640):734. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(89)92257-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]