Abstract

Background

The high number of mutations and consequent structure modifications in a Receptor-Binding Domain (RBD) of the spike protein of the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 increased concerns about evading neutralization by antibodies induced by previous infection or vaccination. Thus, developing novel drugs with potent inhibitory activity can be considered an alternative for treating this highly transmissible variant. Considering that Urtica dioica agglutinin (UDA) displays antiviral activity against SARS-CoV-2, the potency of this lectin to inhibit the Receptor Binding Domain of the Omicron variant (RBDOmic) was examined in this study.

Purpose

This study examines how UDA inhibits the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2 by blocking its RBD, using a combination of in silico and experimental methods.

Methods

To investigate the interaction between UDA and RBDOmic, the CLUSPRO 2.0 web server was used to dock the RBDOmic-UDA complex, and molecular dynamics simulations were performed by the Gromacs 2020.2 software to confirm the stability of the selected docked complex. Finally, the binding affinity (ΔG) of the simulation was calculated using MM-PBSA. In addition, ELISA and Western blot tests were used to examine UDA's binding to RBDOmic.

Results

Based on the docking results, UDA forms five hydrogen bonds with the RBDOmic active site, which contains mutated residues Tyr501, Arg498, Arg493, and His505. According to MD simulations, the UDA-RBDOmic complex is stable over 100 ns, and its average binding energy during the simulation is -87.201 kJ/mol. Also, the ELISA test showed that UDA significantly binds to RBDOmic, and by increasing the concentration of UDA protein, the attachment to RBDOmic became stronger. In Western blotting, RBDOmic was able to attach to and detect UDA.

Conclusion

This study indicates that UDA interaction with RBDOmic prevents virus attachment to Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and, therefore, its entry into the host cell. Altogether, UDA exhibited a significant suppression effect on the Omicron variant and can be considered a new candidate to improve protection against severe infection of this variant.

Keywords: Omicron, RBD, UDA, Molecular docking, Molecular dynamics, ELISA

List of abbreviations: ACE2, Human angiotensin-converting enzyme-2; ELISA, DAD, Diode Array Detector, Enzyme-Linked ImmunoSorbent Assay; H-Bond, Hydrogen bond; Ni-NTA, Nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid; OD, Optical Density; PBS, Phosphate Buffered Saline; PDB, Protein data bank; RBD, Receptor binding domain; RBDOmic, RBD of Omicron Variant; Rg, Radius of gyration; RMSD, Root-mean-square deviation; RMSF, Root-mean-square fluctuation; RT, Room temperature; SARS-CoV-2, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2; SDS-PAGE, Sodium dodecyl-sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis; SP Sephadex, Sulfopropyl Sephadex; TMB, 3,3′5,5′-Tetramethylbenzidine; UDA, Urtica dioica agglutinin

Graphical abstract

Introduction

As COVID-19 continues its inexorable march, taking millions of lives and causing more than half a billion confirmed cases worldwide, the current prevention and treatment strategies against this infectious disease are still not precise enough, mainly due to its high mutation rate. Furthermore, there have been reports of warning humoral post-vaccination response (Notarte et al., 2022a, Notarte et al., 2022b). Omicron is the fifth SARS-CoV-2 variant of concern which has various subvariants harboring different mutations in the RBD of the spike protein leading to evading RBD-targeting neutralizing antibodies or vaccination strategies (Sun et al., 2022). Omicron new subvariants have been reported to multiply 70 times faster than the delta strain in the bronchi, resulting in the pandemic phenomenon (Mohapatra et al., 2022). Increased transmissibility and immune evasion of new subvariants of Omicron emphasize the necessity for additional therapeutic approaches to ending the devastating COVID-19 pandemic. The binding of coronaviruses with specific receptors on the surface of host cells determines the spread of the virus. In addition, these receptors are one of the most important targets for developing antiviral drugs. SARS-CoV-2 has a single-stranded RNA that encodes the four main structural regions of the virus, including the spike glycoprotein (S), membrane protein (M), envelope (E), and nucleocapsid (N). This virus enters the host cell through the spike protein. The most important part of the spike is the region called RBD, which is responsible for binding to the ACE2 Receptor.

Natural proteins have recently been noticed due to their bio-accessibility and bioavailability, less toxicity, and ease of production, compared to industrial drugs (de Leon et al., 2021; Fernandez et al., 2021; Quimque et al., 2021; Brogi et al., 2022).

Urtica dioica l. (Urticaceae) is a dioecious, herbaceous, perennial plant, 1 to 2 m (3 to 7 ft) tall in the summer and dying down to the ground in winter. U. dioica agglutinin (UDA) is used in different countries for therapeutic effects on various diseases, including neuronal and digestive systems, as well as cardiovascular and immune diseases (Dhouibi et al., 2020). Past research has shown that UDA has the ability to inhibit various viruses (Taheri et al., 2022), while its pure extract has little toxicity in the in vitro phase (Keyaerts et al., 2007). Also, in vivo studies indicate that UDA is able to inhibit SARS-CoV by inhibiting the binding function to the host cell (Kumaki et al., 2011). Therefore, UDA is a suitable drug candidate to inhibit different strains of this virus. Upreti et al. (2021) have applied the bioinformatics approach for screening a series of bioactive chemical compounds from Himalayan stinging nettle as potent inhibitors of SARS-CoV-2.

The drug's effect on the virus is accomplished at the nanometer scale and nanoseconds interval. Therefore, the investigation must be performed at the atomic scale to study the drug's inhibitory effect on the virus (Hadi et al., 2019). Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulation is a computer-based strategy used to analyze the physical movements of molecules and atoms. MD's approach can answer several questions and unveil mechanisms at the nanoscale. Many researchers have applied MD simulations for the drug's inhibitory effect on the virus (Sabzian-Molaei et al., 2022).

Due to the fact that UDA is a suitable candidate for inhibiting the Omicron strain of SARS-CoV-2 and that recently different sub-lineages of this strain, including BA.2.12.1, BA.4, and BA.5 have started to spread, investigating the mechanism of UDA's effect on the receptors of this virus strain is of significant importance. Therefore, in this article, the effect of UDA on the RBDOmic is investigated by molecular dynamics simulation and experimental study.

Materials and methods

Preparation of chemicals and reagents

The RBDOmic gene was cloned in the pET22a vector and then transferred to E.coli BL21 (DE3) as an expression system, and the RBDOmic protein was extracted by ultra-sonication, then purified by Ni-NTA column. The purified protein was evaluated by SDS-PAGE acrylamide gel 15%.

Purification of UDA

During the winter, stinging nettle rhizomes were collected from the north of Iran. The UDA was purified by affinity chromatography on chitin column and ion-exchange chromatography on SP-Sephadex according to the previously described method; UDA purity analysis was evaluated using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography on the Reverse Phase column (HPLC) and SDS-PAGE (Sabzian-Molaei et al., 2022).

Preparation of proteins

The Crystal structure of RBDOmic and ACE2 (resolution: 3.2 Å, ID: 7t9l) and UDA (resolution: 1.9 Å, ID: 1enm) in PDB format was obtained from Protein Data Bank (https://www.rcsb.org/). And RBDOmic was considered as the target receptor.

Molecular docking

Molecular docking for UDA-RBDOmic and UDA-ACE2 was performed separately using the ClusPro 2.0 webserver https://cluspro.bu.edu/publications.php. This tool allows docked complexes and their clusters to be screened by considering protein properties. The best docking modes obtained from Cluspro were visualized by PyMOL (Schrodinger, 2010). PIPER docking algorithm was used to select the best complexes based on two factors: the first factor was the lowest energy, which follows the formula for calculating the interaction energy between two proteins: E = w1 Erep + w2 Eattr + w3 Elec + w4 EDARS. Here, Erep and Eattr represent the repulsive and attractive contributions to the van der Waals interaction energy. EDARS is a pairwise structure-based potential constructed by the Decoys as Reference State (DARS) method. The terms w1, w2, w3, and w4 account for the weight of each term that allows for optimization.

The second factor was the ability of extensive connections to the target protein binding site. Finally, the selected models were analyzed using LigPlot+.

Molecular dynamics

After the evaluation of the molecular docking results, molecular dynamics simulation studies were performed for binding analysis and the stability of the selected complexes obtained from the docking, so two simulations were performed for free RBDOmic, UDA-RBDOmic, and ACE2-RBDOmic complexes. MD simulations were performed using GROMACS 2018 software under the Amber99sb.ildn force field for 100 ns. SPC216 water molecules were selected. The simulations were done in cubic boxes with a minimum distance between the protein and the wall of 1.0 nm. The system was neutralized before minimization by adding an appropriate number of chlorine or sodium atoms. The time step parameter was set to 0.002 ps. The v-rescale algorithm was used to keep the temperature constant, and the Berendsen algorithm was used to keep the pressure constant. First, NVT (constant volume and pressure) was performed to stabilize the temperature at 300 K for 1 ns, and then NPT (constant pressure and temperature) was performed to stabilize the pressure at 1 bar for 1 ns. Finally, a 100 ns simulation was run (Quimque et al., 2021).

The analyses of Root mean square deviation (RMSD), the radius of gyration (Rg), the intermolecular hydrogen bond profile of complexes, distance fluctuation plot (mindist), contact map, and hydrogen bond occupancy were conducted and the outputs were studied.

Binding affinity calculation

The free binding energy of the best-docked model was calculated after 100 ns of molecular dynamics simulation, as well as the ACE2-RBDOmic crystallographic structure (ID: 7t9l) in PRODIGY. This is an online protein binding energy prediction server for calculating ΔG (kcal/mol) affinity binding and complex stability, focusing on affinity prediction in biological complexes (https://bianca.science.uu.nl/prodigy/). Furthermore, in order to calculate the free binding energy of UDA-RBDOmic during the simulation, MM-PBSA (Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area) was performed using the g_mmpbsa tool (every one ns of 100 ns simulation).

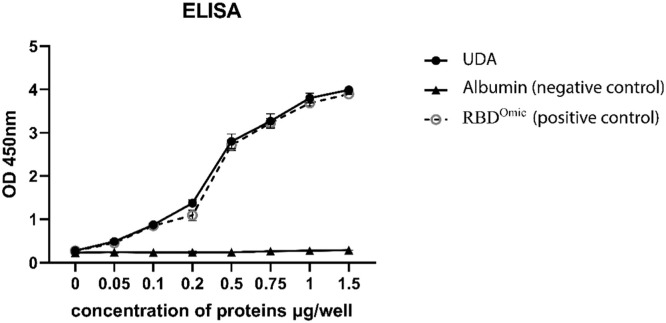

Attachment study by ELISA

The ELISA test was performed to evaluate the binding of UDA to RBDOmic, using different concentrations of the UDA protein (0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5 μg) and albumin as a negative control. Moreover, different concentrations (0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.5 μg) of RBDOmic were coated in the ELISA as positive control and then incubated at 37 °C for 1 h It was blocked with 4% skim milk and washed with PBS afterward. Next, RBDOmic protein was added at a concentration of 0.5 μg per well, incubated at room temperature for 1 h, and washed with PBS. Subsequently, the rabbit antibody anti-His-HRP- conjugated was added, and after 1 h of incubation at room temperature, TMB as a chromogen was used, and the OD was reported in 450 nm by an ELISA reader.

Western blotting

First, UDA was run on SDS-PAGE gel 15% and then transferred to the nitrocellulose membrane by wet method Western blotting; then the membrane was blocked by skim milk 4%, and RBDOmic protein was added at 0.5 μg/ml and incubated for 1 h in RT. Subsequently, the membrane was washed with PBS, and Rabbit anti-HIS-HRP conjugated was added afterward and incubated in RT for 1 h, then washed with PBS and developed by DAB.

Results

Structure of RBDOmic

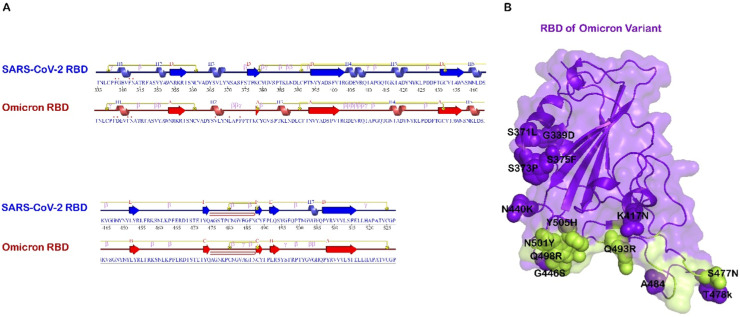

The difference between the amino acid sequence of RBDOmic and RBD of SARS-CoV-2 is in 15 residues (Fig. 1 ). These residues are N501Y, G496S, Y505H, Q493R, T478K, S477N, Q498R, G446S, N440K, S373P, S375F, S371l, E484A, G339D, and K417N.

Fig. 1.

A. Secondary structure comparison of SARS-CoV-2 (PDB ID: 6lzg) and Omicron variant (PDB ID 7t9l) in the receptor-binding domain (RBD) Using PDBSUM. B. Omicron-RBD, the mutation is shown with spheres, and the binding site is marked green.

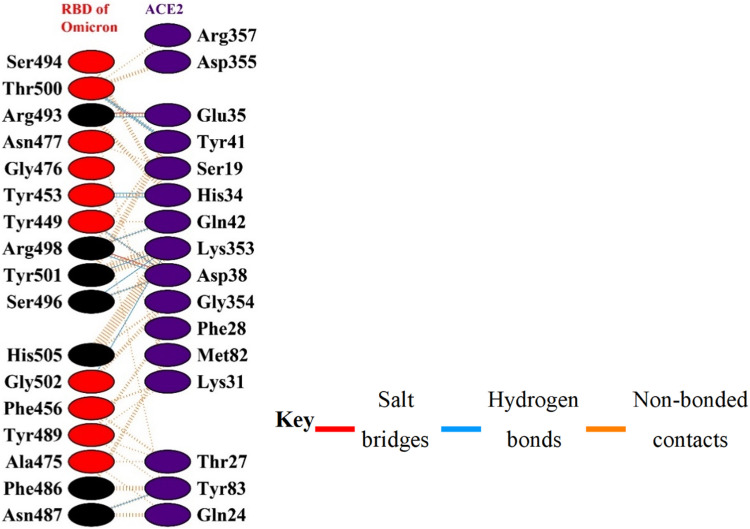

RBDOmic residues that interact with ACE2 include Ser494, Arg493, Asn477, His505, Gly502, Ser496, Tyr501, Thr500, Arg498, Tyr449, Gly476, Ala475, Asn487, Phe456, Tyr489, Phe486, and Tyr453 (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Interacting residues between receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant (RBDOmic) and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). Mutations on RBDOmic are shown in black color.

Docking of uda and rbd of S-protein of omicron variant

UDA bound to the RBDOmic protein is shown in Fig. 3 , which is observed to bind to the ACE2 and RBDOmic binding sites.

Fig. 3.

Docked UDA–RBDOmic complex, receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant (RBDOmic), Urtica dioica Agglutinin (UDA), and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) are shown in blue, red, and green, respectively.

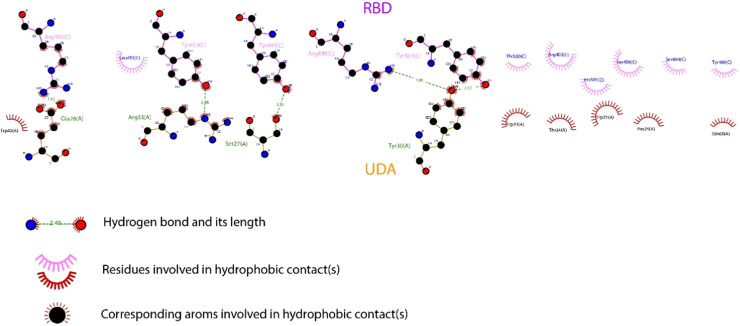

UDA forms five hydrogen bonds with important residues Tyr501, Arg498, Arg493, Tyr449, and Tyr453 and hydrophobic bonds with residues His505, Ser496, Thr500, Tyr489, and Ser494 of RBDOmic (Fig. 4 ). Among the mentioned residues, Tyr501, Arg498, Arg493, His505, Ser496, and Ser494 have undergone mutations in the Omicron variant.

Fig. 4.

LigPlot+ diagram of interactions between receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant (RBDOmic) and Urtica dioica Agglutinin (UDA).

Docking of uda and ACE2

According to Cluspro scoring, the top five docking models did not interact with the binding site of ACE2 (Fig. 5 ). Therefore, ACE2 is not considered an UDA target.

Fig. 5.

The top five docked complexes for UDA-ACE2 (UDA: Urtica dioica Agglutinin, ACE2: Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2).

Molecular dynamics simulation

According to docking results, we first performed the molecular dynamics simulation for free target protein (RBDOmc) to evaluate and analyze the stability of the protein. Then, simulations of RBDOmic-UDA and RBDOmic-ACE2 complexes were performed (each for 100 ns). RMSD and RMSF analyses were performed to observe the deviation of C atoms of the protein on its spine and fluctuations in protein residues throughout MD simulations. The RMSD diagram shows that the RBDOmic-UDA complex has undergone fewer fluctuations than the RBDOmic and RBDOmic-ACE2 complexes, which ultimately shows the significant structural stability of the RBDOmic-UDA complex (Fig. 6 ).

Fig. 6.

Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) plots for receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant (RBDOmic) and RBDOmic in ACE2-RBDOmic and UDA-RBDOmic complexes during 100 ns molecular dynamics simulations.

In addition to RMSD, the stability of the complex was determined by Rg, which defines the structural compactness of the protein. The Rg diagram does not show significant fluctuations during the simulation for complexes (Fig. 7 b).

Fig. 7.

A. The average number of H-bonds between Urtica dioica Agglutinin (UDA) and receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant (RBDOmic), and angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) and RBDOmic B. Radius of gyration for RBDOmic, ACE2-RBDOmic and UDA-RBDOmic during 100 ns molecular dynamics simulations.

Hydrogen bonds between the active site of RBDOmic and UDA were investigated by the h-gmx program, and the results showed the formation of stable and effective hydrogen bonds of UDA with RBDOmic. UDA can form hydrogen bonds with residues without leaving the active site during MD simulation like the RBDOmic-ACE2 complex (Fig. 7a).

The occupancy of hydrogen bonds between UDA and RBD was calculated during the simulation. There are ten hydrogen bonds between RBD residues and UDA.

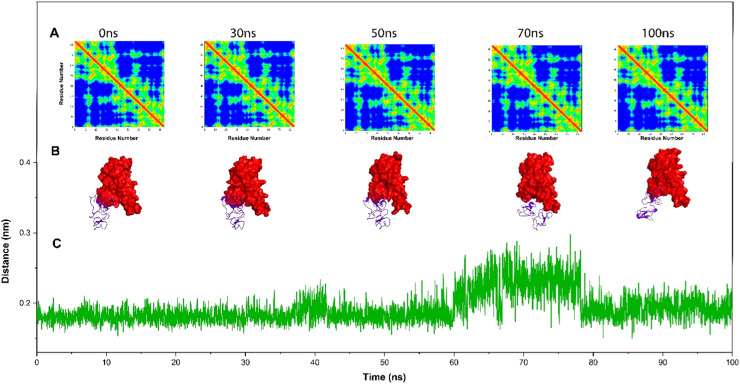

The distance graph from the central areas of the active sites of RBDOmic and UDA was examined during 100 ns of the simulation. It was observed that UDA maintains its distance from RBDOmic. Although the distance increases from 1.8 nm to 2.6 nm in the range of 78–62 ns, the UDA returns to its position. In order to confirm their stable connection, snapshots were taken at different simulation times. Also, the residual contact maps calculated using the mdmat tool in Gromacs revealed that most connections remained intact during various simulation times (Fig. 8 ).

Fig. 8.

A. Residual contact map between Urtica dioica Agglutinin (UDA) and receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant (RBDOmic) at 0, 30, 50, 70, and 100 ns of molecular dynamics simulations. B. Simulation snapshots at 0, 30, 50, 70, and 100 ns. C. Distance between UDA and RBDOmic during simulations.

The binding affinity (ΔG) of UDA-RBDOmic at 100 ns and ACE2-RBDOmic were calculated at −9.4 kcal/mol and −10.8 kcal/mol, and their dissociation constants Kd (M) at 27 °C were 1.3E-07 and 1.3E-08, respectively. The number of interfacial contacts (ICs) is shown in Table 2 . Furthermore, the binding free energy was calculated by MM-PBSA during the simulation. The results showed that the average binding energy for the UDA-RBDOmic complex is −87.201 kJ/mol. Various energy parameters were also calculated and displayed in Table 3 .

Table 1.

The occupancy of hydrogen bonds between UDA and RBDOmic in molecular dynamic simulations (above the threshold of 10%).

| Occupancy (%) | Atom number Acceptor)) | Atom number (Donor) | Acceptor | Donor | No. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21.6 | 348 | 3671 | GLU28 (OE1) | ARG493 (E21) | 1. |

| 76.5 | 265 | 3812 | TRP21 (O) | GLY502 (H) | 2. |

| 13.7 | 349 | 3668 | GLU28 (OE2) | ARG493 (E11) | 3. |

| 94.1 | 3789 | 284 | THR500 (O) | TRP23 (HE1) | 4. |

| 17.6 | 3789 | 20 | THR500 (O) | ARG2 (H11) | 5. |

| 98.9 | 3857 | 253 | HIS505 (O) | TRP21(HE1) | 6. |

| 41.2 | 349 | 3671 | GLU28 (OE2) | ARG493 (E21) | 7. |

| 17.6 | 348 | 3668 | GLU28 (OE1) | ARG493 (E11) | 8. |

| 10.1 | 3018 | 417 | TYR453 (OH) | ARG33 (NE) | 9. |

| 25.5 | 348 | 3665 | GLU28 (OE1) | ARG493 (HE) | 10. |

Table 2.

Comparison of the interactions between RBDOmic-UDA and RBDOmic-ACE2 (PDB ID: 7t9l).

| Type of contact | ACE2–RBDOmic complex | UDA–RBDOmic complex |

|---|---|---|

| charged–charged | 7 | 3 |

| charged–polar | 7 | 9 |

| charged–apolar | 18 | 17 |

| polar–polar | 5 | 1 |

| polar–apolar | 16 | 9 |

| apolar–apolar | 12 | 10 |

Table 3.

Binding free energy for RBDOmic-UDA and RBDOmic-ACE2 complexes.

| Type of energies (kJ/mol) | UDA-RBDOmic |

|---|---|

| ΔE van der waals | −307.970 +/- 43.882 |

| ΔE electrostatic | 48.484 +/- 17.641 |

| ΔE polar solvation | 190.859 +/- 32.036 |

| ΔE SASA | −18.393 +/- 5.633 |

| ΔG total (binding energy) | −87.201 +/- 9.589 |

ELISA

The ELISA test was done in triplicate and showed that the UDA protein could successfully bind to the RBDOmic protein. The negative control was albumin, which doesn't attach to the RBDOmic protein. By increasing the concentration of UDA protein, the attachment to RBDOmic became stronger. Also, recombinant RBDOmic protein with histidine tag was used as a positive control (Fig. 9 ).

Fig. 9.

ELISA result, the attachment of Urtica dioica Agglutinin (UDA) to receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant (RBDOmic). By increasing the concentration of UDA, the attachment was increased, and the RBDOmic didn't attach to the albumin protein (negative control). RBDOmic was used as a positive control.

Western blotting

In Western blotting, UDA was run on SDS-PAGE gel and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane, then RBDOmic HIS-tag protein was added, and finally, rabbit anti-HIS-HRP was used. If RBDOmic binds to UDA, the band must be observed based on the binding between the second antibody-HRP and nitrocellulose. The appearance of a band in the 8.5 kDa region indicates that RBDOmic could attach to the UDA protein and detect it (Fig. 10 ).

Fig. 10.

Western blotting of Urtica dioica Agglutinin (UDA) and receptor binding domain of SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant (RBDOmic). C+: Positive control with 8 kDa weight and histidine tags. UDA pro: UDA protein with 8.5 kDa weight and M: protein marker.

Discussion

Despite the discovery of an effective vaccine against COVID-19, new types of SARS-CoV-2 virus, including the Omicron strain, have emerged because RNA-positive SARS-CoV-2 has a high mutation rate (Guo et al., 2021). Omicron has the same structure as SARS-CoV-2, except for the change in its spike structure, which has made the effectiveness of vaccines against it become a significant challenge. Kumar et al. (2022) reported that the omicron variant was immune to host humoral immunity by antibodies. UDA is a small molecular plant monomeric peptide of 86 amino acids with a weight of 8.7 kD, which has the property of binding to N-acetylglucosamine. This lectin is very stable, so its activity is kept at pH 1.0 and 80 °C for up to 15 min. Kumaki et al. (2011) reported that UDA treatment of SARS-CoV infection in mice results in a significant therapeutic effect that protects mice from death and weight loss. They also investigated how UDA worked in vitro and reported that it specifically inhibited SARS-CoV virus replication when added just before but not after adsorption. These data suggest that UDA likely inhibits SARS-CoV-2 infection by targeting early stages of the replication cycle, i.e., adsorption or penetration. In other studies, according to the fact that UDA is a lectin and has the property of binding to glycans, they associated the inhibition of infection by UDA with the binding of UDA to the carbohydrates of the SARS-CoV family spike glycoprotein (Konozy et al., 2022; Lokhande et al., 2022). In our previous study, by removing the surface glycans of the RBD of SARS-CoV-2 and inhibiting RBD by UDA, it was hypothesized that the main reason for virus inhibition is not limited to the binding of UDA to glycans and that UDA has the ability to stably bind to the active site of SARS-CoV-2 RBD protein (Sabzian-Molaei et al., 2022). Also, UDA can be beneficial because its production time is much shorter, and its source plant is found worldwide.

In this research, the effect of the herbal protein UDA on RBDOmic has been investigated. In general, this virus enters the host cell with the help of a spike glycoprotein through ACE2. ACE2 enzyme is present in organs such as the lungs, heart, liver, brain, and bladder and may cause damage and side effects resulting from the attack of the virus (Verdecchia et al., 2020). Therefore, inhibition of ACE2 and RBD enzymes can be used to prevent the invasion of this virus into the cell and dampen the damage caused by it. In the recent SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, ACE2 receptors can be considered the entry door for the virus as the devil. In a mouse model of SARS infection, Yang et al. (2007) showed that the attack of the virus increases with overexpression of the ACE2 enzyme, so an anti-ACE2 enzyme antibody could block the attack of the SARS virus. However, ACE2 receptors also have several beneficial effects. The main protective function of the ACE2 enzyme is to degrade Angiotensin II into Angiotensin-1–7 (Turner et al., 2004). In experimental and clinical models of lung inflammation, Angiotensin-1–7 exerts anti-inflammatory effects with less penetration around the perivascular and peri‑bronchial areas and prevention of subsequent fibrosis (Verdecchia et al., 2020). Also, Angiotensin-1–7 plays an important role in the pro-thrombotic and pro-inflammatory processes (Liang et al., 2015). Catching pneumonia as a result of acute respiratory syndrome is one of the potential and fatal complications of SARS-CoV-2 (Verdecchia et al., 2020). Experimental studies show that the reduction of ACE2 receptor expression causes important lesions of pulmonary inflammation. As a result, a drug that inhibits ACE2 acts like a double-edged sword; while it prevents the virus from entering the host cell, it causes inflammatory complications and can lead to the patient's death during the treatment phase (Verdecchia et al., 2020). The results of our research show that UDA, as a safe herbal compound with low toxicity, only has an inhibitory effect on RBDOmic and does not inhibit ACE2. Therefore, it can be introduced as a suggested drug for the treatment of the Omicron variant of SARS-CoV-2, which needs further clinical investigations. In the Omicron variant, 30 mutations occur in the spike protein, half of which take place in the RBD, including N501Y, G496S, Y505H, Q493R, T478K, S477N, Q498R, G446S, N440K, S373P, S375F, S371l, S375F, S371l, E438, and G496. The results from this research show that UDA forms five hydrogen bonds with important residues Tyr501, Arg498, Arg493, Tyr449, and Tyr453 and hydrophobic bonds with residues including His505, Ser496, Thr500, Tyr489, and Ser494 of RBDOmic (Fig. 5). Among the mentioned residues, Tyr501, Arg498, Arg493, His505, Ser496, and Ser494 are mutated in the Omicron variant. Molecular dynamics simulations conducted in an aqueous environment for 100 ns demonstrated a rearrangement of the UDA and RBDOmic complex positions. According to the RMSD diagram, the RBDOmic-UDA complex shows fewer fluctuations than the RBDOmic, indicating that the complex is structurally stable. As shown by the distance plot, UDA does not detach from RBDOmic during the simulation (average 1.9 Å). Therefore, the UDA remains constant in RBDOmic during 100 ns, despite the distance increasing to 2.4 m during 62–78 ns. The snapshots taken during the simulation show that the UDA does not detach from the binding site, it only slightly changes its position and then returns to the previous position. It appears that an average of five hydrogen bonds are formed in 100 ns for RBDOmic-UDA, and hydrogen bonds, up to seventeen, have been observed. The residues connected during the simulation also retained their connections based on comparing residual contact maps. Therefore, RBDOmic-UDA complexes were stable in water. After the simulation, the binding energy of the UDA-RBDOmic complex was calculated at −9.4 kcal/mol, and for the RBDOmic-ACE2 complex, it was calculated at −10.8 kcal/mol. These results are comparable and close to each other. To validate our in-silico results, we used an ELISA assay. The absorbance of UDA-treated cells was significantly different from that of negative controls (albumin) in this study. In addition, as the concentration of UDA protein increased, binding to RBDOmic became stronger. Also, Western blot results showed that RBDOmic could bind to the UDA protein and detect it. Overall, UDA has the potential to inhibit the interaction between RBD of the Omicron variant and host cells.

Conclusion

After the emergence of the Omicron variant and the mutation in the RBD structure, the potential of UDA as a suitable drug for the new strain was aimed to find out. In this study, we investigated the interactions between mutated RBD of the Omicron strain and UDA. The results of docking UDA forms five hydrogen bonds with the RBDOmic active site, which contains mutated Tyr501, Arg498, Arg493, and His505. MD simulations show that the UDA-RBDOmic complex is stable during 100 ns, and the average binding energy is −87.201 kJ/mol. Additionally, the ELISA test indicated that UDA significantly binds to RBDOmic and that this attachment increased with increasing UDA concentration. Also, in Western blot tests, RBDOmic attached to and detected UDA. Overall, UDA suppressed the Omicron variant significantly and could therefore be considered a new remedy for preventing severe infections of this strain.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Conceptualization: HS, AH and AA. Supervision: HS and AA. Methodology, In silico investigation, software analysis and writing the initial draft of the manuscript: FS. Laboratory investigation: HG and FS. Validation: AA and SH. Review & Editing: AH, HS, FF, and AA. Funding acquisition: HS.

All data were generated in-house, and no paper mill was used. All authors agree to be accountable for all aspects of work ensuring integrity and accuracy.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Declaration of Competing Interest

We declare that we have no financial and personal relationships with other people or organizations that can inappropriately influence our work, there is no professional or other personal interest of any nature or kind in any product, service and/or company that could be construed as influencing the position presented in, or the review of, the manuscript entitled.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This research is partially supported by a grant and aid from Shahid Beheshti University to HS (Grant No: S/600/1159).

Acknowledgments

We thank all members of the laboratory of regenerative medicine & biomedical innovations for their helpful technical support and discussions during experiments. Some parts of the graphical abstract were obtained from Servier Medical Art ((http://smart.servier.com), licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/) and Vecteezy graphics: Free vector art via https://www.vecteezy.com; Vector illustration credit: https://www.vecteezy.com.

References

- Brogi S., Quimque M.T., Notarte K.I., Africa J.G., Hernandez J.B., Tan S.M., Calderone V., Macabeo A.P. Virtual combinatorial library screening of quinadoline B derivatives against SARS-CoV-2 RNA-dependent RNA polymerase. Computation. 2022;10:7. [Google Scholar]

- de Leon V.N.O., Manzano J.A.H., Pilapil D.Y.H., Fernandez R.A.T., Ching J.K.A.R., Quimque M.T.J., Agbay J.C.M., Notarte K.I.R., Macabeo A.P.G. Anti-HIV reverse transcriptase plant polyphenolic natural products with in silico inhibitory properties on seven non-structural proteins vital in SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis. J. Gen. Engin. Biotechnol. 2021;19:1–17. doi: 10.1186/s43141-021-00206-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhouibi R., Affes H., Salem M.B., Hammami S., Sahnoun Z., Zeghal K.M., Ksouda K. Screening of pharmacological uses of Urtica dioica and others benefits. Prog. Biophys. Mol. Biol. 2020;150:67–77. doi: 10.1016/j.pbiomolbio.2019.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez R.A., Quimque M.T., Notarte K.I., Manzano J.A., Pilapil IV D.Y., de Leon V.N., San Jose J.J., Villalobos O., Muralidharan N.H., Gromiha M.M. Myxobacterial depsipeptide chondramides interrupt SARS-CoV-2 entry by targeting its broad, cell tropic spike protein. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2021:1–12. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2021.1969281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo L., Bi W., Wang X., Xu W., Yan R., Zhang Y., Zhao K., Li Y., Zhang M., Cai X. Engineered trimeric ACE2 binds viral spike protein and locks it in “Three-up” conformation to potently inhibit SARS-CoV-2 infection. Cell Res. 2021;31:98–100. doi: 10.1038/s41422-020-00438-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hadi A., Rastgoo A., Bolhassani A., Haghighipour N. Effects of stretching on molecular transfer from cell membrane by forming pores. Soft Mater. 2019;17(4):391–399. [Google Scholar]

- Keyaerts E., Vijgen L., Pannecouque C., Van Damme E., Peumans W., Egberink H., Balzarini J., Van Ranst M. Plant lectins are potent inhibitors of coronaviruses by interfering with two targets in the viral replication cycle. Antiviral Res. 2007;75:179–187. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konozy E.H.E., Osman M.E.-f.M., Dirar A.I. Plant lectins as potent Anti-coronaviruses, Anti-inflammatory, antinociceptive and antiulcer agents. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 2022 doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2022.103301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaki Y., Wandersee M.K., Smith A.J., Zhou Y., Simmons G., Nelson N.M., Bailey K.W., Vest Z.G., Li J.K.-K, Chan P.K.-S. Inhibition of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus replication in a lethal SARS-CoV BALB/c mouse model by stinging nettle lectin, Urtica dioica agglutinin. Antiviral Res. 2011;90(1):22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.antiviral.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Thambiraja T.S., Karuppanan K., Subramaniam G. Omicron and Delta variant of SARS-CoV-2: a comparative computational study of spike protein. J. med. Virol. 2022;94(4):1641–1649. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang B., Wang X., Zhang N., Yang H., Bai R., Liu M., Bian Y., Xiao C., Yang Z. Angiotensin-(1-7) attenuates angiotensin II-induced ICAM-1, VCAM-1, and MCP-1 expression via the MAS receptor through suppression of P38 and NF-κB pathways in HUVECs. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 2015;35:2472–2482. doi: 10.1159/000374047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lokhande K.B., Apte G.R., Shrivastava A., Singh A., Pal J.K., Swamy K.V., Gupta R.K. Sensing the interactions between carbohydrate-binding agents and N-linked glycans of SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein using molecular docking and simulation studies. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2022;40(9):3880–3898. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2020.1851303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohapatra R.K., Tiwari R., Sarangi A.K., Sharma S.K., Khandia R., Saikumar G., Dhama K. Twin combination of Omicron and Delta variants triggering a tsunami wave of ever high surges in COVID-19 cases: a challenging global threat with a special focus on the Indian subcontinent. J. Med. Virol. 2022;94(5):1761–1765. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notarte K.I., Guerrero-Arguero I., Velasco J.V., Ver A.T., Santos de Oliveira M.H., Catahay J.A., Khan M.S.R., Pastrana A., Juszczyk G., Torrelles J.B. Characterization of the significant decline in humoral immune response six months post-SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccination: a systematic review. J. Med. Virol. 2022;94(7):2939–2961. doi: 10.1002/jmv.27688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Notarte K.I., Ver A.T., Velasco J.V., Pastrana A., Catahay J.A., Salvagno G.L., Yap E.P.H., Martinez-Sobrido L.B., Torrelles J., Lippi G. Effects of age, sex, serostatus, and underlying comorbidities on humoral response post-SARS-CoV-2 Pfizer-BioNTech mRNA vaccination: a systematic review. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 2022:1–18. doi: 10.1080/10408363.2022.2038539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quimque M.T., Notarte K.I., Letada A., Fernandez R.A., Pilapil IV D.Y.i., Pueblos K.R., Agbay J.C., Dahse H.-.M., Wenzel-Storjohann A., Tasdemir D. Potential cancer-and Alzheimer's Disease-targeting phosphodiesterase inhibitors from Uvaria alba: insights from in vitro and consensus virtual screening. ACS omega. 2021;6:8403–8417. doi: 10.1021/acsomega.1c00137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quimque M.T., Notarte K.I., Adviento X.A., Cabunoc M.H., de Leon V.N., FSL D.R., Lugtu E.J., Manzano J.A., Monton S.N., Muñoz J.E. Polyphenolic Natural Products Active In Silico against SARS-CoV-2 Spike Receptor Binding Domains and Non-Structural Proteins-A Review. Comb. Chem. High Throughput Screen. 2021 doi: 10.2174/1386207325666210917113207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabzian-Molaei F., Hosseini S., Bolhassani A., Eskandari V., Norouzi S., Hadi A. Antiviral Effect of Saffron Compounds on the GP120 of HIV-1: an In Silico Study. ChemistrySelect. 2022;7 [Google Scholar]

- Sabzian-Molaei F., Nasiri Khalili M.A., Sabzian-Molaei M., Shahsavarani H., Fattahpour A., Molaei Rad A., Hadi A. Urtica dioica Agglutinin: a plant protein candidate for inhibition of SARS-COV-2 receptor-binding domain for control of Covid19 Infection. PLoS One. 2022;17(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0268156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrödinger, L., 2010. The PyMOL molecular graphics system, version 1.3 r1. August.

- Sun Y., Lin W., Dong W., Xu J. Origin and evolutionary analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 Omicron variant. Int. J. Biosaf. Biosecurity. 2022;4(1):33–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jobb.2021.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taheri Y., Quispe C., Herrera-Bravo J., Sharifi-Rad J., Ezzat S.M., Merghany R.M., Shaheen S., Azmi L., Prakash Mishra A., Sener B., Kılıç M., Sen S., Acharya K., Nasiri A., Cruz-Martins N., Tsouh Fokou P.V., Ydyrys A., Bassygarayev Z., Daştan S.D., Alshehri M.M., Calina D., Cho W.C. Urtica dioica-derived phytochemicals for pharmacological and therapeutic applications. Evid.-based Complement. Altern. Med. 2022:2022. doi: 10.1155/2022/4024331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner A.J., Hiscox J.A., Hooper N.M. ACE2: from vasopeptidase to SARS virus receptor. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2004;25(6):291–294. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upreti S., Prusty J.S., Pandey S.C., Kumar A., Samant M. Identification of novel inhibitors of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2) receptor from Urtica dioica to combat coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Mol. Divers. 2021;25(3):1795–1809. doi: 10.1007/s11030-020-10159-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdecchia P., Cavallini C., Spanevello A., Angeli F. The pivotal link between ACE2 deficiency and SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur. J. Intern. Med. 2020;76:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2020.04.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang X.-h., Deng W., Tong Z., Liu Y.-x., Zhang L.-f., Zhu H., Gao H., Huang L., Liu Y.-l., Ma C.-m. Mice transgenic for human angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 provide a model for SARS coronavirus infection. Comp. Med. 2007;57:450–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]