Abstract

The furthest extent of restorative proctectomy involves a colon to anal anastomosis in the deep pelvis. While the anastomosis can be challenging, it can allow the patient to avoid a permanent ostomy. Patient and surgeon preparation can improve patient outcomes. This article will describe the options, technical challenges, and anecdotal tips for coloanal anastomosis.

Keywords: colonanal anastomosis, handsewn anastomosis, colonic J pouch, stapled coloanal

Many patients prefer to push the limits of rectal resection and anastomosis in an effort to avoid permanent stoma. Restorative proctectomy is most commonly performed for low rectal cancer but can also be beneficial for patients with extrasphincteric complex fistulae or anastomotic leak following traditional low anterior resection. While there was once considered a 5-cm rule for the distal margin in rectal cancer, the safe distal resection margin has been reduced to 1 cm or less in low rectal tumors with the emergence of neoadjuvant multimodal therapy and tumor downstaging. 1 2 The reduction in distal resection margin has increased the boundaries for sphincter preservation in patients with tumors that were once determined to require an abdominoperineal resection (APR). With an increase in patients who could have sphincter preservation, there is a need to describe technique and options for restoration of intestinal continuity with a colon to anal anastomosis. The goal of this article is to highlight the details and nuances of coloanal anastomosis.

Patient Selection

While some patients may desire a coloanal anastomosis to avoid a permanent stoma, distal anastomosis is associated with a higher rate of incontinence and defecatory dysfunction. Incontinence following coloanal anastomosis ranges from 20 to 50%. 3 Therefore, the decision to perform a coloanal anastomosis must be individualized based on the patient's wishes, functional status, and extent of resection. To determine which patients can be offered a coloanal anastomosis, detailed evaluation of the tumor as well as assessment of the patient's overall function and bowel-specific function are required.

First and foremost, detailed evaluation of the tumor is necessary to see if coloanal anastomosis is technically feasible. Exam should focus on the distal and radial margins of the tumor and often requires exam under anesthesia to determine the distal aspect of the tumor in relationship to the dentate line. There must be a distal “landing zone” for the coloanastomosis for the sutures. The dentate line should be maintained during the resection and serves as the lowest possible extent of resection to avoid creating an ectropion, which will result in fecal soiling, bleeding, and pain. Radial margins can be evaluated with magnetic resonance imaging, although the depth of invasion of low tumors within the anal canal may be better visualized with endorectal ultrasound. Imaging should be coupled with physical exam findings. Since imaging is often less reliable with tumors that extend into the anal canal, the findings from the exam under anesthesia should be the primary guide for determining operative candidacy. On physical exam, involvement of the external anal sphincter is suggested by tethering of the tumor and the inability to lift the tumor off the underlying muscles with a digital exam. During the exam, a finger is placed at the edge of the tumor and pushed proximally to see if the tumor appears to lift off the underlying sphincter muscle. If the tumor involves the external anal sphincter, sphincter function will be severely compromised during oncologic resection. While involvement of the external anal sphincter is typically a contraindication for coloanal anastomosis, tumor involvement of the internal anal sphincter complex does not preclude coloanal anastomosis. With a transanal transabdominal approach with intersphincteric dissection, tumor involvement of the internal anal sphincter proximal to the level of the dentate line is resectable. Tumor involvement of the distal-most part of the internal anal sphincter (distal to the dentate line) or involvement of the external anal sphincter would be better served by APR.

In terms of general function, the patient must be able to tolerate major surgery and should have adequate mobility. Coloanal anastomosis is often performed with diverting stoma to counter the increased risk of anastomotic leak with low pelvic anastomosis. Consequently, the patient must undergo two major abdominal operations (resection with coloanal followed by ileostomy closure). Patients who could not tolerate a leak or two surgeries may be better served with a permanent stoma. Mobility should also be evaluated as patients will need adequate mobility to adapt to the functional changes that follow coloanal anastomosis. Patients who require substantial assistance to stand and ambulate will have significant difficulty during recovery as the bowel movements adapt with the absence of the rectum causing fecal urgency and bowel frequency.

Evaluation of fecal continence is critical to provide advice for the patient and set reasonable functional expectations. Since one of the main functions of the rectum is to store stool until a socially appropriate time, proctectomy with coloanal anastomosis inherently changes bowel function and increases the risk of incontinence either due to structural changes or neural damage from resection. Furthermore, the technique for transanal transabdominal proctectomy with coloanal anastomosis will decrease sphincter function from dilation of the anal canal during the transanal portion. If there is baseline fecal incontinence, fulminate fecal incontinence will likely result afterwards. Since large distal tumors often secrete mucous and blood that results in some fecal leakage, fecal incontinence scores should be assessed both in the office at present as well as historically 6 to 12 months ago when the tumor was likely smaller and less symptomatic.

Patient Expectations

Detailed discussion with the patient preoperatively sets expectations for postoperative success. During the visit prior to resection or ostomy reversal, time spent setting appropriate expectations will save substantial time postoperatively addressing possible patient dissatisfaction. Following proctectomy and coloanal anastomosis, expectations for fecal seepage and bleeding are discussed. Description of the anatomy and planned extent of resection are useful so the patients can see what will be removed and how intestinal continuity will be restored. The focus is to set expectations for a new normal that will require some time for the bowel to adapt. Prior to ostomy closure and restoration of intestinal continuity, patients are counseled regarding low anterior resection syndrome (LARS) and initial steps to manage it. Patients are reassured that bowel function will improve over time as the neorectum matures. For the first 6 weeks to 3 months after ostomy closure, there is an expectation for urgency, frequency, and leakage. Patients are encouraged to wear an absorptive pad or adult diaper temporarily, especially while sleeping. Changes in sexual function are also addressed and followed postoperatively.

Complications

Prior to performing any major surgery, possible complications of the surgery should be discussed with the patient and anticipated to minimize both the risk of complication as well as the possible impact of a complication. In addition to the usual risks of pelvic surgery, coloanal anastomosis carries an increased risk of anastomotic leak and LARS. Anastomotic leak occurs in nearly 15% of patients following coloanal anastomosis. 4 The more distal of an anastomosis, the higher the leak rate. The risk of leak is increased in patients with prior pelvic radiation. 5 Even with proximal fecal diversion, leak can result in anastomotic sinus formation or increased pelvic fibrosis leading to defecatory dysfunction.

While significant LARS occurs in over 40% of patients undergoing low anterior resection, 6 nearly all patients who have a coloanal anastomosis will have some degree of dysfunction. LARS is defined by at least one of the following with negative impact on quality of life: unpredictable bowel function, altered stool consistency, increased frequency, difficulty with complete evacuation, urgency, incontinence, or fecal soiling. 7 It has been easier to relay the risk of LARS to patients by discussing the innate function of the rectum as a reservoir. With the rectum removed, a new reservoir can be created out of the colon but it will never function as well as their native rectum and requires time to adjust and adapt.

Other risks that are discussed include changes to sexual function. Male patients are counseled regarding retrograde ejaculation and erectile dysfunction due to nerve injury from pelvic dissection. Female patients may have increased risk of infertility and dyspareunia from adhesions and nerve injury. 8

Patient Preparation

Preoperatively, patients meet with the enterostomal therapist to be marked for a stoma (most commonly a loop ileostomy) and be educated regarding stoma management. Dehydration prevention is highlighted and patients are encouraged to measure their own ostomy output even while inpatient after surgery. Preoperative mechanical and antibiotic bowel prep is given to all patients to decrease the risk of wound infection with possible benefit on ileus and anastomotic leak. 9 All patients are placed on an Enhanced Recovery After Surgery pathway. Patients with malnutrition can be evaluated for prehabilitation to improve recovery.

Operative Technique

Mobilization of the Colon

Mobilization of the colon is critical to allow for colon reach to the anus. The transverse colon mesentery is mobilized up and over the ligament of Treitz and the 4th portion of the duodenum to the left branch of the middle colic artery. High ligation of the inferior mesenteric vein (IMV) just at the inferior border of the pancreas and high ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery at the aorta are beneficial. Lastly, the left colic artery is divided and the IMV is divided a second time as it runs with the left colic artery near the bifurcation of the left colic artery and the superior rectal artery. Additional technique for mobilization is discussed later in this edition by Dr. Vargas.

Perfusion to the distal aspect of the colon must be assessed. This can be done via the marginal artery pulsatility, indocyanine green administration, or seeing pulsatile flow in the arterioles feeding the colon off of the marginal artery. Care should be taken to avoid creating a hematoma at the distal transection of the marginal artery as that will complicate the anastomotic creation and occupy valuable space in the deep pelvis.

Options for Coloanal Anastomosis

Common options for colon to anal anastomosis include straight end-to-end anastomosis (EEA), Baker-style side-to-end anastomosis (SEA), or a colonic J-pouch to anal anastomosis (CJPAA). Each has their role and limitations. Both Baker SEA and J-pouch have improved functional outcomes with decreased stool frequency and decreased need for antidiarrheal medication when compared with straight EEA. 10 Additionally, both SEA and CJPAA have been shown to have a lower anastomotic leak rate. 11 However, both require 3 to 5 cm more colonic mobilization. As a historical reference, transverse coloplasty was once popularized years ago to create a reservoir out of the colon with a straight EEA. However, coloplasty has been abandoned due to higher risk of leak with no functional improvement over a straight EEA. 12

Creation of a Neorectum

After proctectomy with planned coloanal anastomosis, the colon is advanced into the pelvis and will serve as the reservoir for stool. As above, there are three main types of neorectum: straight EEA, Baker SEA, and CJPAA.

End-to-End Coloanal Anastomosis

EEA is reserved when the pelvis is too narrow to allow for a SEA or J-pouch anastomosis. Straight EEA coloanal anastomoses have increased frequency, urgency, and incontinence when compared with colonic J-pouch. 13 Following proctectomy, attempts should be made to determine if the colon can be folded and fit into the pelvis to allow for a SEA or CJPAA. However, in some patients with a narrow pelvis and a large amount of central obesity, one limb of the colon and mesocolon is all that can fit into the pelvis. In those patients, straight EEA is the only possible option for restoration. Ideally, this can be anticipated and appropriate functional outcomes can be discussed with the patients preoperatively.

From a technical standpoint, care is taken to avoid any hematoma in the mesentery as the hematoma will make passage of the colon more challenging. The left colon should be completely mobilized. Pelvic hemostasis is also assured. In the stapled technique, the anvil head is placed at the end of the proximal colon conduit with a purse-string suture. The spike is deployed through the anal stump and the anvil can be grasped with a long Kelly clamp to advance into the pelvis. With a handsewn anastomosis, sutures are placed on the conduit to orient the direction of the colon and grasped transanally to pull the colon conduit into the pelvis from the transanal incision.

Side-to-End Coloanal Anastomosis

The side-to-end colorectal anastomosis was popularized in 1950 by Dr. Baker. 14 In a SEA, the side of the colon is attached to the proximal end of the rectal/anal stump. This form of anastomosis creates a small reservoir in the blind end of the colon that may contribute to decreased LARS after coloanal anastomosis. The size of the blind end of the SEA has been debated but is normally between 3 and 6 cm in length. 15 Some consider the SEA to have a lower leak rate than a straight EEA, possibly related to increased blood flow to the anastomosis since it is more proximal to the division of the mesentery. 16

The antimesenteric border of the colon is brought down into the pelvis and estimated which part of the proximal colon will reach best into the low pelvis. The location is marked and is ideally 3 to 6 cm away from the intended distal transection point. SEA is most commonly used for a stapled anastomosis. In terms of length, personal preference has been to bring out the anvil 6 cm away from the planned distal staple line. After imbricating the staple line at the tip of the blind end (∼1 cm) and then firing the EEA stapler (∼1.5 cm), the blind end measures roughly 4 cm. Many have suggested that bringing out the anvil 3 cm away from the staple line is desired. After imbrication and firing the stapler, a 1-cm blind end is left, raising the concern for ischemia of the tip of the colon from close staple lines.

If the colon has previously been divided, the staple line is removed and inspected for perfusion. If the colon has not previously been divided, a colotomy is made distal to the intended transection site to insert the anvil. The anvil can be placed with the spike first or with the anvil head first. Placement of the anvil head first prevents snagging the mucosa on the way in with the spike. The head is passed beyond the desired antimesenteric colotomy until the spike reaches the mark. The spike is then brought through the colon and the anvil is pulled until the head of the anvil completely opposes the colon wall. A 3–0 purse-string suture is then placed around the anvil to ensure that any torn serosa will be brought into the stapler. The colotomy at the distal end of the colon is then closed with a gastrointestinal anastomosis (GIA) stapler and oversewn with Lembert sutures. Similar to above the anvil is passed into the pelvis to meet the spike from the EEA stapler with a long Kelly clamp. Care is taken to maintain orientation of the anastomosis without twisting.

Colonic J-Pouch to Anal Anastomosis

A short colonic J-pouch for creation of a neorectum was first popularized in 1986. 17 A colonic J-pouch is shorter than the typical ileal pouch and normally measures 5 to 8 cm. The theoretical benefit of the colonic J-pouch is the creation of a larger reservoir that could mimic the rectum. When compared with a straight EEA, a CJPAA has a lower rate of overall major complications. 11

Creation of a colonic J-pouch involves folding the distal 6 to 8 cm of the colon onto the more proximal part. The folded colon can then be placed into the pelvis to ensure there is adequate reach and space within the pelvis. If the mesentery cannot reach, the mesentery can be lengthened by scoring the anterior and posterior peritoneum, ensuring division of the IMV and left colic artery, and unfolding the mesentery at the splenic flexure where the transverse colon mesentery can adhere to the descending colon mesentery. Once adequate mobility is ensured, stay sutures can be placed on the colon to set up the J-pouch. The location for colotomy is chosen on the antimesenteric side of the bowel approximately 6 to 8 cm proximal to the staple line. Personal preference is to make the colotomy in longitudinal fashion along the length of the bowel rather than transversely. Additionally, the colotomy is placed on the superior edge of the colon to preserve the lower edge for anastomosis ( Fig. 1 ). A GIA stapler between 50 and 80 mm is inserted into the colotomy with the shorter end of the GIA stapler placed into the distal end of the bowel to avoid making a large blind loop at the tip of the J-pouch ( Fig. 2 ). The laparoscopic GIA stapler can be very useful for J-pouch creation with a slimmer profile that results in a smaller colotomy. Care is taken to make sure the mesentery is excluded from the staple line. The transverse staple line at the tip of the J pouch is imbricated with suture and folded into the proximal limb to support the tip of the pouch and cover the staple line in case of a leak at the tip of the J-pouch. If a stapled anastomosis is desired, the anvil can be inserted and a purse-string suture (normally 3–0 monofilament) placed to cinch the bowel on the anvil. If a handsewn anastomosis is needed, marking sutures can be placed on the bowel to orient the bowel and to grasp to pull the colonic J-pouch into the pelvis ( Fig. 3 ).

Fig. 1.

Location for colotomy in colonic J-pouch creation is on the antimesenteric side in longitudinal fashion favoring the superior part of the bowel to preserve the inferior part of the bowel for the anastomosis.

Fig. 2.

Stapled colonic J-pouch anal anastomosis. Proximal colon conduit is mobilized and the site of the colotomy is marked (purple mark) ( A ). The colon is folded, colotomy made, and a gastrointestinal anastomosis (GIA) stapler inserted ( B ). The mesentery is excluded from the staple line. The end-to-end anastomosis (EEA) anvil is inserted into the colotomy and a purse-string suture used to close the defect around the anvil ( C ). The tip of the J-pouch is imbricated with Lembert sutures and tucked into the proximal bowel ( D ).

Fig. 3.

Handsewn colonic J-pouch anal anastomosis. The colon conduit is folded, colotomy made on the antimesenteric side ∼6–8 cm away from the distal end of the bowel, and a gastrointestinal anastomosis (GIA) stapler is inserted and fired to form a common channel ( A ). Sutures are placed to imbricate the tip of the J-pouch and fold the distant end to the proximal side ( B ). The anterior staple line can be oversewn for support ( C ). The colotomy is opened and orientation sutures are placed with white sutures superior and to the patients' left and purple sutures inferior and to the right ( D ). Orientation sutures are then grasped from the anus and brought down into the pelvis.

Anastomotic Technique

All three of the common types of coloanal anastomosis (EEA, SEA, or CJPAA) can be fashioned with a stapled anastomosis or a handsewn anastomosis. For any coloanal, the dissection from abdominal side progresses as low as possible, ideally into the anal canal. Posteriorly, dissection is continued down to below the level of the coccyx. Routine digital rectal exam during dissection can confirm adequate dissection from the abdomen. Anteriorly in a woman, the vagina can be lifted with a vaginal retractor to straighten the posterior wall of the vagina and make anterior dissection in the rectovaginal septum easier. Anteriorly in a male patient, Denonvilliers' fascia should be identified and preserved if possible to stay in the correct plane leading just posterior to the seminal vesicles and prostate. While anterior and posterior dissection can include some blunt dissection as the tissue planes are avascular, lateral dissection to connect the anterior and posterior dissection is performed with an energy device. Even if open operations, laparoscopic energy devices are preferred as they are commonly less bulky and allow better visualization in the deep pelvis.

Stapled Anastomosis

Stapled anastomosis can be either the traditional double-stapled anastomosis or a single-stapled anastomosis. In the double-stapled anastomosis, the tumor or pathology is dissected from the abdominal side and a transverse anastomosis (TA) stapler is placed distal to the pathology with a clear margin and used to seal the rectal or anal stump. As dissection progresses into the anal canal, there is limited mesorectum and the distal-most rectum is transected with a TA 30-mm stapler. An EEA stapler is then used to connect the colon to the anus. Extreme care must be taken with introduction of the EEA into the anus as it can easily disrupt the transverse staple line on the stump. In my practice, the anus is often dilated digitally with two digits to allow passage of the EEA stapler head. Rectal sizers are avoided as they can easily disrupt the transverse staple line. The EEA stapler is gently introduced and the spike is deployed just posterior to the transverse staple line. This can be done under direct visualization laparoscopically/robotically or done under palpation from above through an open incision. The anvil is then secured to the spike. The handle of the stapler is elevated while closing the stapler to drop the stapler head and avoid entrapment of anterior pelvic structures (vagina, prostate, etc.). Care should also be taken to avoid entrapment of the levator muscle laterally as this is believed to increase pelvic pain and defecatory dysfunction. The vagina (if applicable) is palpated to ensure that it is free of the stapler. The EEA stapler is closed and precompression is done routinely for at least 1 minute to improve staple formation. 18 Bowel orientation is confirmed prior to firing the stapler. The stapler is fired and removed and the stapler is inspected for two intact circumferential anastomotic donuts. Digital exam and leak testing are routinely done. Leak testing is typically done with a flexible endoscope to visualize the anastomosis, look for bleeding, evaluate for leak, and look at the configuration of the anastomosis to ensure there was no twisting. Oversewing of the anastomosis is not commonly done as it is too low in the pelvis to approach from above.

In a single-stapled EEA anastomosis, there is no transverse staple line. Purse-string sutures are placed proximally and distally. The distal purse-string suture should be full-thickness bites of the distal rectum but not trap any anal sphincter muscle. The purse-string suture should be placed at least 1.5 to 2 cm proximal to the dentate line as the stapler will consume over 1 cm of tissue in the anastomosis. The distal purse-string suture is tied over a red rubber catheter that is used to cover the spike of the EEA stapler and safely guide the spike through the center of the distal purse-string. Similar to above, the stapler is closed while aiming the head of the stapler posteriorly to avoid entrapment of the anterior pelvic structures. In a single-stapled coloanal, the distal aspect of the rectum/anal canal is approached via a transanal incision (details below). Due to the tissue required for a circular anastomosis with an EEA stapler, the single-staple technique is rarely used and is reserved for a select patent that would have a 1.5- to 2-cm distal margin of healthy tissue above the dentate and below the margin of the pathology. However, stapled coloanal anastomoses have good outcomes with decreased rate of stricture when compared with the handsewn technique. 19

Handsewn Technique

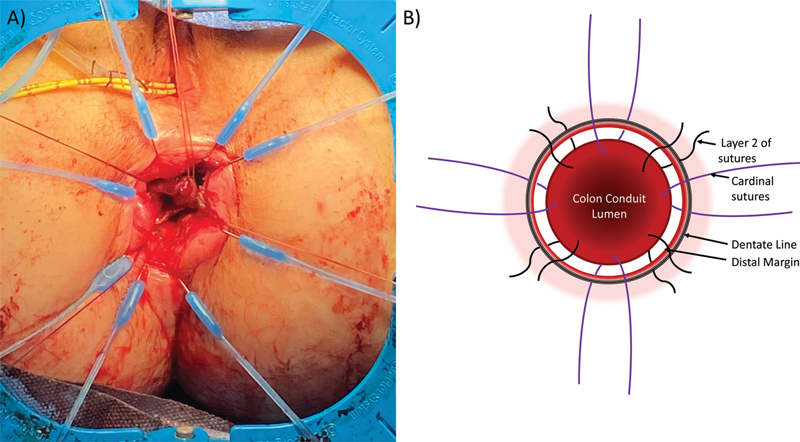

Handsewn coloanal anastomosis is ideal for the lowest of tumors/pathology. A transabdominal, transanal approach is taken with transection of the distal rectum or anal canal from the perineal side. In this scenario, the tumor or pathology can be well-visualized from a transanal approach and clear margins can be obtained. Often, if the margin is very close, frozen sections can be sent to pathology intraoperatively to guide the extent of the distal margin. The patient is most commonly placed in lithotomy position rather than flipping the patient prone. With lithotomy, care must be taken to ensure that the patient is low enough on the bed to maximize perineal exposure. The benefit of high lithotomy is that the transperineal dissection can be guided from the transabdominal side. However, some surgeons prefer to close the abdomen after the transperineal portion and flip the patient into the prone jackknife position for the perineal portion. In high lithotomy, the legs are elevated to flatten the perineum and increase exposure. The Lone Star retractor (CooperSurgical Inc, Trumbull, CT) is uniformly used to aid in exposure. The desired distal margin is marked with electrocautery circumferentially. Full-thickness transection of the distal rectum leads to the intersphincteric plane in the distal rectum. During full-thickness transection, cardinal sutures with 2–0 polyglactin sutures are placed in four locations on the distal bowel. Needles are left on the sutures as they will be used for the anastomosis. Sutures are tagged and placed on the Lone Star. After transection of the anal canal, the retraction hooks can be advanced to the distal transection margin to increase exposure. Dissection continues proximally in the intersphincteric plan until it connects with the dissection from above. It is often easiest to dissect posteriorly first as the dissection can be guided by the coccyx. Once connected posteriorly, dissection can wrap around on either side. For the anterior portion, care is taken to stay in the rectovaginal septum in a female patient and avoid the membranous urethra prior to its entrance into the prostate in male patients. The specimen can be everted out of the perineal incision to address most distal part of the anterior margin. Once the pathology is removed and the margins cleared, hemostasis is assured. Postoperative pelvic hematomas can easily be infected and will affect long-term function of the neorectum. The proximal colon is then passed down to the perineum. Orienting sutures should be placed on the proximal bowel to ensure that the colon does not twist on the way to the perineum. Personal preference is white sutures anteriorly and on the patient's left and colored sutures posteriorly and to the right. A ring clamp is advanced from the perineal dissection to grasp the sutures. As the sutures are pulled from the perineal incision, the colon is advanced into the pelvis. Once the distal aspect of the colon conduit is visualized, handsewn anastomosis is done.

The previously tagged cardinal sutures are passed through the colon conduit in full-thickness fashion, and the marking sutures placed previously in the colon are removed. Once the four cardinal sutures are in place, 3–0 absorbable sutures are then used for the remainder of the anastomosis. One suture is typically placed between each of the cardinal sutures to divide the anastomosis into eight parts ( Fig. 4 ). In each 1/8 of the anastomosis, one to three 3–0 absorbable sutures are placed depending on the distance. Since the anastomosis is already aligned with the previously placed sutures, the remainder of the sutures can be passed through both the proximal and distal aspect of the anastomosis in one pass making it more time efficient. In total, there are approximately 24 sutures placed, similar to Sir Alan Parks' original description in 1972. 20

Fig. 4.

Handsewn coloanal anastomosis. ( A ) Lone Star retractor placed for exposure with cardinal sutures at the four cardinal locations. ( B ) Illustration with cardinal sutures is placed superiorly, inferiorly, and laterally. Between the cardinal sutures, secondary sutures are placed to divide the anastomosis into 8 sections.

Personal Preferences

Stapled coloanal anastomoses are associated with decreased anastomotic leakage and stricture. 19 However, stapled anastomoses are limited in how low they can be used. Handsewn anastomosis is typically required for the most distal pathology as the dissection can start at the level of the dentate line. Trying to staple with an EEA stapler at the dentate line will result in an ectropion since the stapler requires a circumferential ring of distal tissue. In my practice, double-stapled EEA anastomosis is the preferred technique for any tumor that can be approached from the abdomen with a good margin. Double-stapled anastomosis is faster and has good functional outcomes. 21 In a double-stapled technique, there is limited benefit of a colonic J-pouch and is functionally similar to a SEA. SEA is a more time-efficient anastomosis and therefore preferred in the double-stapled technique.

If the pathology is too distal to allow a double-stapled technique with a TA stapler to come across the distal rectum in the anal canal, handsewn anastomosis is preferred. With a handsewn coloanal anastomosis, a short colonic J-pouch is preferred over a SEA for future ease of endoscopic surveillance. In a SEA coloanal anastomosis, the mesenteric side of the colon conduit directly opposes the anus. During surveillance endoscopy, the scope is inserted into the anus and directly into the colon wall. With a CJPAA, the scope can be inserted into a reservoir and then navigate into the blind end and the proximal end. For the stapler for the colonic J-pouch, the laparoscopic stapler has been useful because it requires a smaller colotomy and the staples extend closer to the tip of the device, leading to a smaller blind end of the pouch. Regarding suture selection, polyglactin suture is routinely used for handsewn coloanal rather than the longer lasting polydioxanone suture because the patients do not perceive the softer braided suture to the same extent as the firmer monofilament suture.

Post-anastomosis

Following anastomosis creation, the anastomosis is routinely inspected with endoscopy and leak testing is done. If there is a small leak, the leak is often not repaired but patients will be diverted for a longer period of time to allow closure of the leak. If the location of the leak can be localized at the time of the anastomosis assessment, it can be noted for closer inspection on follow-up exams prior to restoration of intestinal continuity. Large leaks will require revision of the anastomosis. Prior to ileostomy closure, gastrografin enema or computed tomography with rectal contrast is done to evaluate for leak and a flexible endoscopy is performed to visualize the anastomosis.

Fecal diversion with a diverting loop ileostomy is routinely used for coloanal anastomosis. The main reason for fecal diversion is that a leak can result in a permanent ostomy because there is limited, if any, distal remaining rectal mucosa to allow revision. Data does suggest that loop transverse colostomy may be more beneficial than loop ileostomy with lower rate of ileus and obstruction. 22 However, takedown of a loop ileostomy is often easier and more forgiving than a loop colostomy. If the ileum is injured during ileostomy closure, more ileum can easily be brought out to allow for a limited small bowel resection. The colon has more limited mobility and has a larger diameter and therefore makes colostomy closure more challenging.

Alternative Options

To avoid the morbidity of ostomy creation, two-stage Turnbull-Cutait coloanal pull-through was described in the early 1950s. 23 The procedure involves proctectomy with exteriorization of the proximal colon through the anus. The colon is mobilized so that the distal aspect can rest beyond the anal canal. Sutures can be placed from the skin of the anal margin to the colon to prevent accidental retraction. The second stage is resection of the distal colonic segment and delayed coloanal anastomosis 6 to 10 days afterwards. With the time interval between the two stages, scarring of the colon is thought to decrease the risk of anastomotic leak. In a 2020 randomized control trial, two-stage Turnbull-Cutait anastomosis had a 13% leak rate. 24 Most leaks were controlled with transanal drainage and did not require stoma creation. When compared with traditional primary coloanal anastomosis with fecal diversion, delayed coloanal anastomosis (Turnbull-Cutait procedure) had a significantly lower rate of pelvic sepsis with similar functional outcomes. 25

Low Anterior Resection Syndrome Management

Discussion should be had with all patients undergoing proctectomy regarding the inherent changes to expect in bowel function following resection. With the most recent definition of LARS, all patients following proctectomy will have some variation of LARS. 7 In our practice, initial management has been fiber and antimotility agents for stool bulking. Expectations are set for 6 to 8 weeks to start to notice improvement as the anastomosis and neorectum mature. If there is ongoing difficultly with LARS, routine use of retrograde enemas is recommended to help with bowel habits. Patients may have benefit from pelvic physical therapy and biofeedback. Lastly, if no improvement with conservative measures and there is a significant issue with incontinence and urgency, sacral nerve modulation is offered and has been beneficial anecdotally. 26

Conclusion

Patients who desire restoration of intestinal continuity following proctectomy must be educated regarding expectations postoperatively. Detailed exam and history highlight which patients would be good candidates for coloanal anastomosis and can allow adequate preparation time for the patient and the surgeon. Having a patient-specific plan prior to entering the operating room can decrease the risk of complications and maximize the chance of a good patient outcome.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest None declared.

References

- 1.On Behalf of the Clinical Practice Guidelines Committee of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons . You Y N, Hardiman K M, Bafford A. The American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons clinical practice guidelines for the management of rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2020;63(09):1191–1222. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kazi M, Bhamre R, DeSouza A. Long-term oncological outcomes of the sphincter preserving total mesorectal excision with varying distal resection margins. J Surg Oncol. 2021;123(08):1784–1791. doi: 10.1002/jso.26467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Benoist S, Panis Y, Boleslawski E, Hautefeuille P, Valleur P. Functional outcome after coloanal versus low colorectal anastomosis for rectal carcinoma. J Am Coll Surg. 1997;185(02):114–119. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(97)00016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trencheva K, Morrissey K P, Wells M. Identifying important predictors for anastomotic leak after colon and rectal resection: prospective study on 616 patients. Ann Surg. 2013;257(01):108–113. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318262a6cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Qin Q, Ma T, Deng Y. Impact of preoperative radiotherapy on anastomotic leakage and stenosis after rectal cancer resection: post hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Dis Colon Rectum. 2016;59(10):934–942. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Croese A D, Lonie J M, Trollope A F, Vangaveti V N, Ho Y H. A meta-analysis of the prevalence of low anterior resection syndrome and systematic review of risk factors. Int J Surg. 2018;56:234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.LARS International Collaborative Group . Keane C, Fearnhead N S, Bordeianou L G. International consensus definition of low anterior resection syndrome. Dis Colon Rectum. 2020;63(03):274–284. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giglia M D, Stein S L. Overlooked long-term complications of colorectal surgery. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2019;32(03):204–211. doi: 10.1055/s-0038-1677027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kiran R P, Murray A C, Chiuzan C, Estrada D, Forde K.Combined preoperative mechanical bowel preparation with oral antibiotics significantly reduces surgical site infection, anastomotic leak, and ileus after colorectal surgery Ann Surg 201526203416–425., discussion 423–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zaman S, Mohamedahmed A YY, Ayeni A A. Comparison of the colonic J-pouch versus straight (end-to-end) anastomosis following low anterior resection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2022;37(04):919–938. doi: 10.1007/s00384-022-04130-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown S, Margolin D A, Altom L K. Morbidity following coloanal anastomosis: a comparison of colonic J-pouch vs straight anastomosis. Dis Colon Rectum. 2018;61(02):156–161. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000000960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ho Y H, Brown S, Heah S M. Comparison of J-pouch and coloplasty pouch for low rectal cancers: a randomized, controlled trial investigating functional results and comparative anastomotic leak rates. Ann Surg. 2002;236(01):49–55. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200207000-00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown C J, Fenech D S, McLeod R S. Reconstructive techniques after rectal resection for rectal cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(02):CD006040. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006040.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baker J W. Low end to side rectosigmoidal anastomosis; description of technic. Arch Surg. 1950;61(01):143–157. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1950.01250020146016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsunoda A, Kamiyama G, Narita K, Watanabe M, Nakao K, Kusano M. Prospective randomized trial for determination of optimum size of side limb in low anterior resection with side-to-end anastomosis for rectal carcinoma. Dis Colon Rectum. 2009;52(09):1572–1577. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181a909d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brisinda G, Vanella S, Cadeddu F. End-to-end versus end-to-side stapled anastomoses after anterior resection for rectal cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2009;99(01):75–79. doi: 10.1002/jso.21182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lazorthes F, Fages P, Chiotasso P, Lemozy J, Bloom E. Resection of the rectum with construction of a colonic reservoir and colo-anal anastomosis for carcinoma of the rectum. Br J Surg. 1986;73(02):136–138. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800730222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakayama S, Hasegawa S, Nagayama S. The importance of precompression time for secure stapling with a linear stapler. Surg Endosc. 2011;25(07):2382–2386. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1527-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cong J C, Chen C S, Ma M X, Xia Z X, Liu D S, Zhang F Y. Laparoscopic intersphincteric resection for low rectal cancer: comparison of stapled and manual coloanal anastomosis. Colorectal Dis. 2014;16(05):353–358. doi: 10.1111/codi.12573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parks A G. Transanal technique in low rectal anastomosis. Proc R Soc Med. 1972;65(11):975–976. doi: 10.1177/003591577206501128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hou S, Wang Q, Zhao S, Liu F, Guo P, Ye Y. Safety and efficacy of side-to-end anastomosis versus colonic J-pouch anastomosis in sphincter-preserving resections: an updated meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World J Surg Oncol. 2021;19(01):130. doi: 10.1186/s12957-021-02243-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Law W L, Chu K W, Choi H K. Randomized clinical trial comparing loop ileostomy and loop transverse colostomy for faecal diversion following total mesorectal excision. Br J Surg. 2002;89(06):704–708. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2168.2002.02082.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Turnbull R B, Jr, Cuthbertson A. Abdominorectal pull-through resection for cancer and for Hirschsprung's disease. Delayed posterior colorectal anastomosis. Cleve Clin Q. 1961;28:109–115. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.28.2.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.TURNBULL-BCN Study Group . Biondo S, Trenti L, Espin E. Two-stage Turnbull-Cutait pull-through coloanal anastomosis for low rectal cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Surg. 2020;155(08):e201625. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2020.1625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hallet J, Milot H, Drolet S, Desrosiers E, Grégoire R C, Bouchard A. The clinical results of the Turnbull-Cutait delayed coloanal anastomosis: a systematic review. Tech Coloproctol. 2014;18(06):579–590. doi: 10.1007/s10151-014-1132-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramage L, Qiu S, Kontovounisios C, Tekkis P, Rasheed S, Tan E. A systematic review of sacral nerve stimulation for low anterior resection syndrome. Colorectal Dis. 2015;17(09):762–771. doi: 10.1111/codi.12968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]