Abstract

Introduction

The occurrence of oral candidiasis (OC) is expected in patients with COVID-19, especially those with moderate to severe forms of infection who are hospitalized and may be on long-term use of broad-spectrum antibiotics or prolonged corticosteroid therapy. We aimed to characterize clinical conditions, the prevalence profile of Candida species, and outcomes of COVID-19 patients with OC.

Methods

In this observational study, oral samples were obtained from COVID-19 patients suspected of OC admitted to Razi teaching hospital. Patients with OC were monitored daily until discharge from the hospital. Species identification was performed by a two-step multiplex assay named YEAST PLEX, which identifies 17 clinically important uncommon to common yeast strains.

Results

Among the 4133 patients admitted with COVID-19, 120 (2.90%) suffered from OC. The onset of signs and symptoms of OC in patients was, on average (2.92 ± 3.596 days) with a range (of 1-29 days). The most common OC presentation was white or yellow macules on the buccal surface or the tongue. In (39.16%) of patients suffering from OC multiple Candida strains (with two or more Candida spp.) were identified. The most common Candida species were C. albicans (60.57%), followed by C. glabrata (17.14%), C. tropicalis (11.42%), C. kefyr (10.83%) and C. krusei (3.42%). Notably, OC caused by multiple Candida strains was more predominant in patients under corticosteroid therapy (P <0.0001), broad-spectrum antibiotics therapy (P = 0.028), and those who used nasal corticosteroid spray (P <0.0001). The majority of patients who recovered from OC at the time of discharge were patients with OC by single Candida species (P = 0.049).

Discussion

Use of corticosteroids and antimicrobial therapy in COVID-19 patients increases risk of OC by multiple Candida strains.

Keywords: Oral candidiasis, COVID-19, Candida species, Corticosteroid, Antibiotic

Introduction

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an ongoing pandemic with global confirmed cases rising once again. In Iran, a country that started COVID-19 vaccination in February 2021, is now (August 2022) involved in the 7th wave of this infection. Bacterial and fungal co-infections are among the assorted factors that lead to comorbidity and mortality in COVID-19 patients (Gangneux et al., 2020; Macauley and Epelbaum, 2021). Most of these patients have risk factors making them prone to fungal infections, such as hospitalization in the intensive care unit (ICU), high prescription rates of broad-spectrum antibiotics, corticosteroid therapy, use of various catheters, underlying diseases, and immunodeficiencies. Among the opportunistic fungal infections, (e.g., Aspergillosis, Mucormycosis, and Candidiasis) the most common fungal co-infections during previous influenza pandemic outbreaks are now the most common fungal co-infections in COVID-19 patients (Meijer et al., 2020; Salehi et al., 2020; Fortarezza et al., 2021; Kayaaslan et al., 2021; Kayaaslan et al., 2022; Vaseghi et al., 2022).

Due to the undefined standard treatment for COVID-19, side effects of medications, aggressive treatment methods, and combinations of treatment regimens, especially those requiring long-term treatment that suppresses the immune system, some oral disorders such as ulcers, blisters, necrotizing gingivitis, salivary gland alterations, white and erythematous plaques, gustatory dysfunction and oral candidiasis (OC) are widely reported in these patients (Brandini et al., 2021).

Oral candidiasis may be the possible cause of these oral disorders due to excessive colonization of Candida species and tissue invasion. As a result of this infection, the patient’s quality of life is also affected due to discomfort and local pain, change in the sense of taste, burning sensation in the mouth, and difficulty breathing and swallowing. It also affects the absorption of liquids and foods consumed by the patients. In addition, OC can progress and involve the esophagus and digestive tract, especially as it can become invasive and spread throughout the bloodstream, causing systemic infections. Timely and accurate diagnosis of OC and accurate identification of its etiological factors in patients suffering from COVID-19 are important to optimize and improve effective treatment (Salehi et al., 2020).

Although Candida albicans is the predominant Candida species found in patients with OC, there is an increasing incidence of oral colonization and infections caused by non-albicans Candida species. Management of candidiasis by non-albicans Candida species is challenging due to the resistance pattern of these species to common antifungal agents. Some of these species, including the emergence of multidrug-resistant C. auris, are sporadically reported in all continents and cause outbreaks in some cases, presenting a serious global health threat. Also, fluconazole resistance is common in non-albicans Candida species such as C. glabrata, and C. krusei, which are now frequently identified as human pathogens, making treatment of these infections arduous (Laudenbach and Epstein, 2009; Aslani et al., 2018; Saris et al., 2018; Ahangarkani et al., 2020; Arastehfar et al., 2020; Carolus et al., 2021; Chatzimoschou et al., 2021). Moreover, candidiasis caused by mixed Candida strains is of great clinical importance, since susceptibility to antifungals differs dramatically among Candida species. Limited data on the characterization of OC and the Candida species profile in patients with COVID-19 are available. This study characterizes clinical conditions, the prevalence profile of Candida species, and outcomes of COVID-19 patients with OC.

Patients and methods

Study design and population

This observational cross-sectional study was conducted from March 2021 to March 2022. Census method was performed for sampling. The study involved hospitalized COVID-19 patients over 18 years old who were admitted to Razi teaching hospital (A COVID-19 referral center in Mazandaran province in the north of Iran). The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Mazandaran University of Medical Science (IR.MAZUMS.REC.1400. 8977), Sari, Iran. In this study, all applied methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The Census method was performed for sampling. The study population consisted of all confirmed COVID-19 patients with proven OC. The definitive diagnosis of COVID-19 infection was based on the positive results of real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR (RT-PCR) assay for severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) on nasopharyngeal swabs. Oral candidiasis was confirmed by the direct microscopic identification of Candida in the oral samples and isolation in culture. Patients with OC were monitored daily until discharge from the hospital. The following information was collected at enrolment: demographic characteristics, i.e. age and sex; signs and symptoms of COVID-19; medications; the outcome of COVID-19; signs and symptoms of an oral infection; comorbidities, oral hygiene; medications, and outcomes of OC.

Clinical specimens

In this study, 208 oral samples were aseptically obtained from patients with suspected OC. Specimens were obtained by sterile cotton swabs moistened with normal saline that were placed on the tongue, buccal mucosa, and labial sulcus with rapid rotational movements for ~20 seconds, sealed, and transported in sterile tubes on the same day of collection, to the microbiology laboratory of the hospital and were examined initially in 10% KOH, followed by inoculation on Sabouraud dextrose agar supplemented with 0.5% chloramphenicol, Difco, USA) and CHROMagar Candida medium (CHROMagar Company, Paris, France) to ensure purity and incubated at 37°C for 24 h. The plates were examined daily for yeast or yeast-like growth. Plates without mycological growth were discarded after 10 days of incubation and considered negative.

Fungal identification

Genomic DNA was extracted from 2 to 3-day-old cultures grown on Sabouraud dextrose agar by using an Ultra Clean Microbial DNA Isolation Kit (Mo Bio Laboratories, Carlsbad, CA USA), according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and stored at–20°C prior to use. A two-step multiplex polymerase chain reaction assay named YEAST PLEX that identifies 17 clinically important common to uncommon yeasts (Candida albicans, Candida dubliniensis, Candida parapsilosis, Candida auris, Candida glabrata, Candida kefyr, Candida krusei, Candida tropicalis, Candida guilliermondii, Candida rugosa, Candida intermedia, Candida lusitaniae, Candida norvegensis, Cryptococcus neoformans, Rhodotorula mucilaginosa, Trichosporon spp. and Saccharomyces cerevisiae) was used according to the instructions as previously described (Aboutalebian et al., 2022). It is notable that the specificity of YEAST PLEX was tested using several reference strains belonging to 17 species and DNA samples of clinically significant non‐target bacteria, parasites, fungi and human genomic DNA. Moreover, the YEAST PLEX method has the ability to identify mixed yeast colonies (Aboutalebian et al., 2022).Sequencing of internal transcribed spacer (ITS) rDNA using primers ITS5 and ITS4 was conducted for strains that weren’t identified by YEAST PLEX multiplex PCR.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the SPSS package (version 16.0; Windows, Chicago, IL, USA). The count data are presented as case numbers and percentages. The percentage values in bar graphs were rounded to the nearest whole number. Differences between groups were determined by the Chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test, with P < 0.05 considered to be statistically significant. In cases with a statically significant difference, adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were reported.

Results

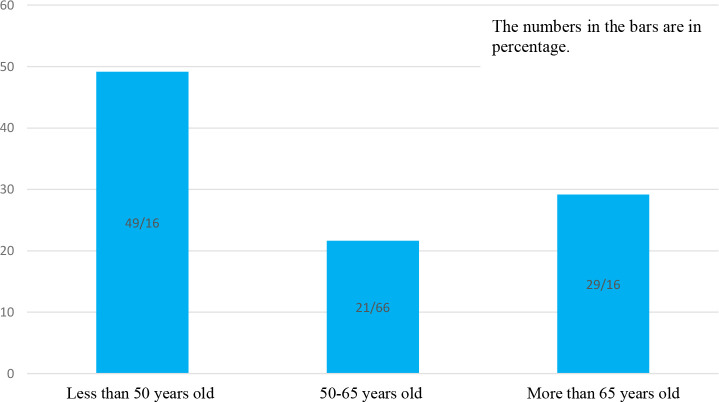

Among the 4133 patients with COVID-19 admitted during this study, 120 (2.90%) suffered from OC. Demographic characteristics, comorbidities, and clinical features of patients are shown in Table 1 . Based on age group patients were distributed in three groups including 49.16% (n=59) less 50 years old, 21.66% (n=26) in the range 50-65 years and 29.16% (n=35) more than 65 years old which are illustrated in Figure 1 .The mean age of the patients was 56.55 ± 15.56 years in the range of (24-96 years old) (n=64; 53.3%) of patients were female and (n=56; 46.7%) were male. The majority of patients had multiple underlying disorders. The most common underlying diseases were diabetes (n=35; 29.2%), hypertension (n=31; 25.8%), and cardiovascular disease (n=26; 21.7%). Also, hyperglycemia during time of admission was seen in (n=17; 14.2%) patients. The most common symptoms were dyspnea (70%), myalgia (65.8%), and fever (55.8%). The most common concomitant medications in patients were Enoxaparin 82.5% and Remdesivir 71.7%. In total, 8.3% of patients were admitted to the ICU, all requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. The average hospitalization stay of patients was 8.22 ± 3.95 days.

Table 1.

Demographic Features, Comorbidities, Sign and Symptoms, Medication and Outcomes of COVID-19 Patients with Oral Candidiasis.

| Demographic | Age (Mean SD)(range) years | 56.55 ± 15.56 (24-96) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage | Number | ||

| Gender; Male/Female | 56/64 | 46.67/53.3 | |

| Diabetes | 35 | 29.16 | |

| Hypertension | 31 | 25.8 | |

| Cardiovascular disease | 26 | 21.7 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 22 | 18.3 | |

| Hypothyroidism | 11 | 9.2 | |

| Cerebral vascular accident | 4 | 3.3 | |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 4 | 3.3 | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 3 | 2.5 | |

| Cancer | 3 | 2.5 | |

| Asthma | 2 | 1.7 | |

| Chronic liver disease | 2 | 1.7 | |

| Sign and symptoms | Dyspnea | 84 | 70 |

| Myalgia | 79 | 65.8 | |

| Fever | 67 | 55.8 | |

| No appetite | 52 | 43.3 | |

| Cough | 51 | 42.5 | |

| Chills | 36 | 30 | |

| Productive cough | 33 | 27.5 | |

| Headache | 30 | 25 | |

| Nausea/vomiting | 28 | 23.3 | |

| Diarrhea | 18 | 15 | |

| Chest Pain | 17 | 14.2 | |

| Sore Throat | 15 | 12.5 | |

| Sweating | 13 | 10.8 | |

| C-reactive protein positive | 78 | 65 | |

| Lymphopenia | 41 | 34.2 | |

| Anemia | 41 | 34.2 | |

| Leukopenai | 28 | 23.3 | |

| Thrombocytopenia | 12 | 10 | |

| Neutropenia | 2 | 1.7 | |

| Nsaids | 120 | 100 | |

| Medications for COVID-19 | All Corticosteroid therapy | 107 | 89.16 |

| IV corticosteroid therapy | 104 | 86.66 | |

| Enoxaparin | 99 | 82.5 | |

| Antiviral therapy | 86 | 71.7 | |

| Broad spectrum antibiotics | 66 | 55 | |

| Spray corticosteroid therapy | 36 | 30 | |

| Outcomes | ICU admission | 10 | 8.3 |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 10 | 8.3 | |

| Non-invasive mechanical ventilation | 105 | 87.5 | |

| Duration of hospitalization (days): Mean ± SD | 8.22 ± 3.95 | ||

| All-cause mortality | 1 | 0.8 | |

Figure 1.

Age Distribution of COVID-19 Patients with Oral Candidiasis.

Oral candidiasis clinical manifestations, comorbidities, oral hygiene, and healthcare-associated factors for higher risk of OC in patients are illustrated in Table 2 . The onset of signs and symptoms of OC in patients was on average (2.92 ± 3.596 days) with a range of 1-29 days.

Table 2.

Oral candidiasis clinical manifestations, comorbidities, social state, and healthcare-associated factors of patients with oral candidiasis caused by single or multiple Candida strains.

| Variables | Total | Single Candida strains N (%) | Multiple Candida strains N (%) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic | ||||

| Age (>65 years) | 35 | 21 (28.76) | 14 (29.78) | 0.904 |

| Gender; Male/Female | 56/64 | 36/37 (49.31/50.68) | 20/27 (46.51/62.98) | 0.469 |

| The onset of signs and symptoms (day) | 4.92 ± 3.596 | 5.25 ± 4.235 | 4.4 ± 2.223 | 0.212 |

| Oral Candidiasis Presentation | ||||

| White or yellow macule on the buccal surface | 79 | 47 (64.38) | 32 (68.08) | 0.676 |

| White or yellow macule on the tongue | 62 | 39 (53.42) | 23 (48.93) | 0.631 |

| Xerostomia | 39 | 25 (34.24) | 14 (29.78) | 0.611 |

| White or yellow macule on the soft palate | 33 | 18 (24.65) | 15 (31.91) | 0.385 |

| Irritation | 26 | 15 (20.54) | 11 (23.4) | 0.711 |

| Atrophy of tongue | 14 | 7 (9.58) | 7 (14.89) | 0.377 |

| Erythematous patch on the tongue | 10 | 5 (6.84) | 5 (10.63) | 0.464 |

| White or yellow macule on the gums | 8 | 6 (8.21) | 2 (4.25) | 0.395 |

| White or yellow macule on the lips | 4 | 1 (1.36) | 3 (6.38) | 0.135 |

| Perioral fissures | 1 | 1 (1.36) | 0 (0) | 0.420 |

| White or yellow macule on the pharynx | 1 | 0 (0) | 1 (2.12) | 0.211 |

| Oral Hygiene and Social Status | ||||

| No mouth washing | 100 | 61 (83.56) | 39 (82.97) | 0.933 |

| No teeth brushing | 77 | 48 (65.75) | 29 (61.7) | 0.651 |

| Decayed teeth | 57 | 40 (54.79) | 17 (36.17) | 0.046 |

| Missing teeth | 52 | 36 (49.31) | 16 (34.04) | 0.099 |

| Dentures | 40 | 19 (26.02) | 21 (44.68) | 0.034 |

| Smoking | 16 | 10 (13.69) | 6 (12.76) | 0.883 |

| Underlying Diseases | ||||

| Diabetes mellitus | 35 | 22 (30.13) | 13 (27.65) | 0.771 |

| hypertension | 31 | 18 (24.65) | 13 (27.65) | 0.714 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 26 | 14 (19.17) | 12 (25.53) | 0.410 |

| Healthcare Associated Factors | ||||

| Corticosteroid therapy duration (day) | 4.44 ± 4.82 | 1.137 ± 0.732 | 7.978 ± 5.289 | <0.0001 |

| Corticosteroid therapy | 107 | 60 (82.19) | 47 (100) | 0.028 |

| IV Corticosteroid therapy | 104 | 57 (78.08) | 47 (100) | <0.0001 |

| Antiviral therapy | 86 | 54 (73.97) | 32 (68.08) | 0.537 |

| Nasal tube oxygen therapy | 74 | 47 (64.38) | 27 (57.44) | 0.446 |

| Mask oxygen therapy | 70 | 46 (63.01) | 24 (51.06) | 0.195 |

| Broad spectrum antibiotics | 66 | 23 (31.08) | 43 (93.47)) | <0.0001 |

| Spray Corticosteroid therapy | 36 | 7 (9.6) | 29 (61.7) | <0.0001 |

| ICU admission | 10 | 5 (6.84) | 5 (10.63) | 0.464 |

| Mechanical ventilation | 10 | 5 (6.84) | 5 (10.63) | 0.464 |

| Treatment and Outcome of Oral Candidiasis | ||||

| Nystatin Suspension | 102 | 66 (90.4) | 36 (76.6) | 0.039 |

| Mouthwash contain nystatin | 14 | 7 (9.58) | 7 (14.89) | 0.396 |

| Fluconazole Infusion | 2 | 0 (0) | 2 (4.25) | 1.000 |

| No treatment | 2 | 2 (2.72) | 0 (0) | 0.268 |

| Cured at discharge time | 103 | 59 (80.82) | 20 (42.6) | <0.0001 |

| Not cured at discharge time | 17 | 14 (18.91) | 27 (57.4) | |

Significance is shown in boldface.

White or yellow macules were present on the buccal surface (n=79; 65%), the tongue (n=62; 51.66%), soft palate (n=33; 27.5%), gums (n=8; 6.66%), lips (n=4; 3.33%) and on the pharynx (n=1; 0.83%). Other presentations included, xerostomia (n=39; 32.5%), irritation (n=26; 21.66%), atrophy of the tongue (n=14; 11.66%), erythematous patches on the tongue (n=10; 8.33%) and perioral fissures (n=1; 0.83%). A majority of patients did not observe oral hygiene (n=100; 83.33% mouthwash, n=77; 64.16% teeth brushing) before OC presentation. Also n=57; 47.5% patients had at least one decayed and tooth (n=40; 33.33%) had dentures. Moreover, n=16; 13.33% of patients were cigarette smokers. Healthcare-associated factors for higher risk of OC were: corticosteroids (n=102; 85%), nasal tube oxygen therapy (n=74; 61.66%), oxygen mask (n=70; 58.33%), broad-spectrum antibiotics (n=66; 55%) and corticosteroid spray use (n=36; 30%). Nystatin suspension (n=102; 85%), mouthwash containing nystatin (n=14; 11.66%), and fluconazole (n=2; 1.66%) were administrated for patients, while (n=2; 1.66%) didn’t receive antifungal therapy. Oral candidiasis was cured in (n=103; 85.83%) of patients at discharge, while (n=17; 14.16%) of patients were not cured at time of discharge.

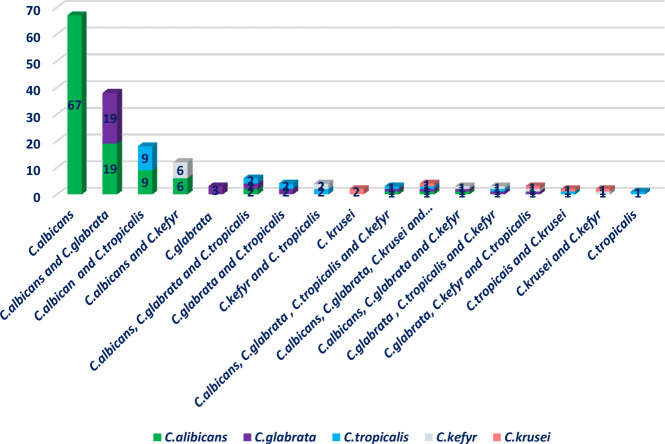

In total, n=47; 39.16% of patients suffered from OC caused by multiple Candida strains (with 2 or more Candida spp.). Distribution of Candida species causing OC based on single or multiple Candida strains is illustrated in Figure 2 .

Figure 2.

Distribution of Candida species causing oral candidiasis based on single or multi-Candida species.

In this study, 175 strains of Candida species isolated from 120 patients were diagnosed as causative agents of oral candidiasis. The most common Candida species were C. albicans (n = 106; 60.57%), followed by C. glabrata (n = 30; 17.14%), C. tropicalis (n = 20; 11.42%), C. kefyr (n = 13; 10.83%) and C. krusei (n = 6; 3.42%). Oral candidiasis clinical manifestations, comorbidities, and healthcare-associated factors were not significantly different between patients infected by single Candida species vs multiple Candida strains. Oral candidiasis caused by single Candida strains was significantly higher in patients with decayed teeth (OR 2.17, 95% CI 1–4.707, P = 0.046). In addition, OC caused by multiple Candida strains was considerably more in patients with dentures (OR 1.171, 95% CI 0.986–1.391, P = 0.034). Significantly, OC caused by multiple Candida strains was more predominant in patients under corticosteroid therapy (OR 4.185, 95% CI 1.047–17.714, P <0.0001), broad-spectrum antibiotics (OR 4.078, 95% CI 2.238–7.429, P = 0.028), and those using inhaled corticosteroid sprays (OR 2.361, 95% CI 1.63–3.419, P <0.0001). Notably, the majority of patients which recovered from OC at the time of discharge from the hospital were patients with candidiasis by single Candida species (OR 3.005, 95% CI 0.912–9.895, P = 0.049). Also, the frequency of Candida species causing OC in patients undergoing corticosteroid and antibiotic therapy versus non-users is shown in Table 3 .

Table 3.

Frequency of Candida species causing oral candidiasis in Patients Undergoing Treatment with Systemic corticosteroids and antibiotics versus Non-Users.

| Species | Corticosteroid Users (n=107) | P value | Antibiotics users(n=66) | P value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | 0.014 | Yes | No | <0.0001 | |

| C. albicans | 55 (51.40) | 12 (11.21) | 17 (25.75) | 50 | ||

| C.glabrata | 3 (2.80) | 0 | 3 (4.54) | 0 | ||

| C.krusei | 2 (1.86) | 0 | 2 (3.03) | 0 | ||

| C.tropicalis | 1 (0.09) | 0 | 1 (1.51) | 0 | ||

| Multi Candida species | 46 (42.99) | 1 | 43 (65.15) | 4 | ||

Significance is shown in boldface.

Discussion

Oral candidiasis is unusual in healthy adults. People at higher risk for getting OC include neonates and individuals with at least one of the risk factors, such as wearing dentures, diabetes, cancer, HIV/AIDS, taking antibiotics or corticosteroids, taking medications that cause dry mouth, and smoking. The occurrence of OC should be anticipated in patients with COVID-19, especially those with moderate to severe forms of infection who are hospitalized and may be on long-term use of broad-spectrum antibiotics or prolonged corticosteroid therapy.

In the current study, during one year, 2.9% of 4133 patients admitted to the COVID-19 referral center in the north of Iran suffered from OC at time of admission. Consistent with other studies, C. albicans was the predominant, isolated species in these patients (Aslani et al., 2018; Salehi et al., 2020). However, it is interesting that 39.16% of these patients suffered from OC caused by two or more Candida spp. The compromising host immune status that affects the natural defenses that suppress the growth of invading pathogens results in multiple Candida species infections. Also, it has been seen in immunocompromised patients that the frequency of infections involving mixed fungal genera would be similar to that of disorders involving mixed fungal species due to severe immunosuppression, which accelerates colonization of Candida strains and boosts the ability of independent pathogens to penetrate tissue Soll, 2022.

In this study, 89% of patients were under corticosteroid therapy, and 55% used broad-spectrum antibiotics. It was found that corticosteroid therapy and use of broad-spectrum antibiotics were significantly higher in patients with OC caused by two or more Candida spp. In addition, the duration of corticosteroid therapy was greater in these patients compared to patients with OC caused by one Candida species. Similar to our findings, Xia et al. reported corticosteroid therapy caused an increased prevalence of OC by non-albicans strains (Xiao et al., 2020). Moreover, Nambiar et al. noted that the development of OC in COVID-19 patients could be due to prolonged mechanical ventilation in the ICU and the long-term use of broad-spectrum antibiotics. (Nambiar et al., 2021). It is noted that the possibility of a potential of OC caused by empirical broad‐spectrum antibiotics prescription in a mild or moderate form of COVID‐19 case should also be considered (Riad et al., 2022). Ahmed et al., in a review article, reported a direct correlation between the development of candidiasis with the use of antibiotics and corticosteroids in COVID-19 patients (Ahmed et al., 2022).

The profile of Candida species causing OC in our patients did not changed during the COVID-19 pandemic, and albeit of antibiotics overuse and corticosteroids in patients, emerging uncommon Candida species was not observed in our study (Aslani et al., 2018; Shokohi et al., 2018; Arastehfar et al., 2020). Candida glabrata, C. tropicalis, C. kefyr and C. krusei were the most prominent non-albicans Candida species isolated from patients with OC caused by multiple Candida species. Notably, these non-albicans Candida species are intrinsically azole resistant or low susceptibility to azole antifungals (Shokohi et al., 2018; Ahangarkani et al., 2019; Ahangarkani et al., 2020). Colonization of oral mucosa with C. glabrata is common in cancer patients (Aslani et al., 2018). The prevalence of C. glabrata in our study was higher compared to the Khalil et al. study in Egypt and Salehi’s study in Iran. However, C. tropicalis prevalence was consistent with the study by Khalil et al., and the prevalence of C. krusei was similar to the findings of Salehi’s study (Salehi et al., 2020; Khalil et al., 2022).

As OC is an indirect indicator of cell-mediated immunodeficiency and has a high predictive value for invasive candidiasis in immunocompromised patients, and the lack of fungal identification methods to species level in low-income countries such as Iran, invasive candidiasis caused by these species in patients exposed to high-risk medications such as patients with moderate to severe form of COVID-19 is noteworthy. The current study has some limitations. Since this observational study was performed on COVID-19 patients with OC, ideally, to obtain insights into the epidemiological status, it was better to compare COVID-19 patients with OC with a control group, such as COVID-19 patients without any co-fungal infection. Moreover, the occurrence of OC in patients with a mild and moderate form of COVID-19 should be investigated. Furthermore, several OC caused by multiple Candida species were observed, antifungal susceptibility testing should be performed for all isolates deemed clinically significant. Also, this study endorses the involvement of dental practitioners among the treatment teams dealing with COVID‐19 patients.

Conclusion

Although the profile of Candida species causing OC in our patients did not changed during the COVID-19 pandemic, overconsumption of corticosteroids and antimicrobial therapy in COVID-19 patients could result in OC by multiple Candida strains.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Mazandaran University of Medical Science (IR.MAZUMS.REC.1400. 8977), Sari, Iran and was performed in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author contributions

FB, MR, FA and AK designed the project, collected data, wrote and performed the critical review of the manuscript. FB, MR, AK, RA-N, NN, AA, AH, LA, SK, KA, AD, ZD and FA contributed to clinical data collection. AA and FA carried out statistical interpretation. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants and staffs of this study at Razi teaching hospital affiliated to Mazandaran University of medical sciences.

Abbreviations

ICU, Intensive care unit; OC, Oral candidiasis; RT-PCR, Real-time reverse transcriptase-PCR; ITS, Internal transcribed spacer; OR, Odds ratios; CIs, Confidence intervals.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Aboutalebian S., Mahmoudi S., Charsizadeh A., Nikmanesh B., Hosseini M., Mirhendi H. (2022). Multiplex size marker (YEAST PLEX) for rapid and accurate identification of pathogenic yeasts. J. Clin. Lab. Anal. 36, e24370. doi: 10.1002/jcla.24370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahangarkani F., Badali H., Rezai M. S., Shokohi T., Abtahian Z., Mahmoodi Nesheli H., et al. (2019). Candidemia due to Candida guilliermondii in an immuno-compromised infant: a case report and review of literature. Curr. Med. Mycol. 5, 32–36. doi: 10.18502/cmm.5.1.535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahangarkani F., Shokohi T., Rezai M. S., Ilkit M., Mahmoodi Nesheli H., Karami H., et al. (2020). Epidemiological features of nosocomial candidaemia in neonates, infants and children: A multicentre study in Iran. Mycoses 63, 382–394. doi: 10.1111/myc.13053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed N., Mahmood M. S., Ullah M. A., Araf Y., Rahaman T. I., Moin A. T., et al. (2022). COVID-19-Associated candidiasis: Possible patho-mechanism, predisposing factors, and prevention strategies. Curr. Microbiol. 79, 127. doi: 10.1007/s00284-022-02824-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arastehfar A., Carvalho A., Nguyen M. H., Hedayati M. T., Netea M. G., Perlin D. S., et al. (2020). COVID-19-Associated candidiasis (CAC): An underestimated complication in the absence of immunological predispositions? J. Fungi (Basel) 6:211. doi: 10.3390/jof6040211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aslani N., Janbabaei G., Abastabar M., Meis J. F., Babaeian M., Khodavaisy S., et al. (2018). Identification of uncommon oral yeasts from cancer patients by MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. BMC Infect. Dis. 18, 24. doi: 10.1186/s12879-017-2916-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandini D. A., Takamiya A. S., Thakkar P., Schaller S., Rahat R., Naqvi A. R. (2021). Covid-19 and oral diseases: Crosstalk, synergy or association? Rev. Med. Virol. 31, e2226. doi: 10.1002/rmv.2226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carolus H., Jacobs S., Lobo Romero C., Deparis Q., Cuomo C. A., Meis J. F., et al. (2021). Diagnostic allele-specific PCR for the identification of Candida auris clades. J. Fungi (Basel) 7:754. doi: 10.3390/jof7090754 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatzimoschou A., Giampani A., Meis J. F., Roilides E. (2021). Activities of nine antifungal agents against candida auris biofilms. Mycoses 64, 381–384. doi: 10.1111/myc.13223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortarezza F., Boscolo A., Pezzuto F., Lunardi F., Jesús Acosta M., Giraudo C., et al. (2021). Proven COVID-19-associated pulmonary aspergillosis in patients with severe respiratory failure. Mycoses 64, 1223–1229. doi: 10.1111/myc.13342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gangneux J. P., Bougnoux M. E., Dannaoui E., Cornet M., Zahar J. R. (2020). Invasive fungal diseases during COVID-19: We should be prepared. J. Mycol. Med. 30, 100971. doi: 10.1016/j.mycmed.2020.100971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayaaslan B., Eser F., Kaya Kalem A., Bilgic Z., Asilturk D., Hasanoglu I., et al. (2021). Characteristics of candidemia in COVID-19 patients; increased incidence, earlier occurrence and higher mortality rates compared to non-COVID-19 patients. Mycoses 64, 1083–1091. doi: 10.1111/myc.13332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kayaaslan B., Kaya Kalem A., Asilturk D., Kaplan B., Dönertas G., Hasanoglu I., et al. (2022). Incidence and risk factors for COVID-19 associated candidemia (CAC) in ICU patients. Mycoses 65, 508–516. doi: 10.1111/myc.13431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khalil M., El-Ansary M. R. M., Bassyouni R. H., Mahmoud E. E., Ali I. A., Ahmed T. I., et al. (2022). Oropharyngeal candidiasis among Egyptian COVID-19 patients: Clinical characteristics, species identification, and antifungal susceptibility, with disease severity and fungal coinfection prediction models. Diagn. (Basel) 12:1719. doi: 10.3390/diagnostics12071719 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laudenbach J. M., Epstein J. B. (2009). Treatment strategies for oropharyngeal candidiasis. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 10, 1413–1421. doi: 10.1517/14656560902952854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macauley P., Epelbaum O. (2021). Epidemiology and mycology of candidaemia in non-oncological medical intensive care unit patients in a tertiary center in the united states: Overall analysis and comparison between non-COVID-19 and COVID-19 cases. Mycoses 64, 634–640. doi: 10.1111/myc.13258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer E. F. J., Dofferhoff A. S. M., Hoiting O., Buil J. B., Meis J. F. (2020). Azole-resistant COVID-19-Associated pulmonary aspergillosis in an immunocompetent host: A case report. J. Fungi (Basel) 6:79. doi: 10.3390/jof6020079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nambiar M., Varma S. R., Jaber M., Sreelatha S. V., Thomas B., Nair A. S. (2021). Mycotic infections - mucormycosis and oral candidiasis associated with covid-19: A significant and challenging association. J. Oral. Microbiol. 13, 1967699. doi: 10.1080/20002297.2021.1967699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riad A., Gad A., Hockova B., Klugar M. (2022). Oral candidiasis in non-severe COVID-19 patients: call for antibiotic stewardship. Oral. Surg. 15, 465–466. doi: 10.1111/ors.12561 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salehi M., Ahmadikia K., Mahmoudi S., Kalantari S., Jamalimoghadamsiahkali S., Izadi A., et al. (2020). Oropharyngeal candidiasis in hospitalised COVID-19 patients from Iran: Species identification and antifungal susceptibility pattern. Mycoses 63, 771–778. doi: 10.1111/myc.13137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saris K., Meis J. F., Voss A. (2018). Candida auris. Curr. Opin. Infect. Dis. 31, 334–340. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000469 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shokohi T., Aslani N., Ahangarkani F., Meyabadi M. F., Hagen F., Meis J. F., et al. (2018). Candida infanticola and candida spencermartinsiae yeasts: Possible emerging species in cancer patients. Microb. Pathog. 115, 353–357. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2017.12.069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soll D. R. (2002). “Mixed mycotic infections,” in Polymicrobial diseases. Eds. Brogden K. A., Guthmiller J. M. (Washington (DC: ASM Press; ). Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK2485/. Chapter 17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaseghi N., Sharifisooraki J., Khodadadi H., Nami S., Safari F., Ahangarkani F., et al. (2022). Global prevalence and subgroup analyses of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) associated candida auris infections (CACa): A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mycoses 65, 683–703. doi: 10.1111/myc.13471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J. L., Xu G. C., De Hoog S., Qiao J. J., Fang H., Li Y. L. (2020). Oral prevalence of candida species in patients undergoing systemic glucocorticoid therapy and the antifungal sensitivity of the isolates. Infect. Drug Resist. 13, 2601–2607. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S262311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.