Abstract

Haemophilus influenzae can utilize different protein-bound forms of heme for growth in vitro. A previous study from this laboratory indicated that nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae (NTHI) strain N182 expressed three outer membrane proteins, designated HgbA, HgbB, and HgbC, that bound hemoglobin or hemoglobin-haptoglobin and were encoded by open reading frames (ORFs) that contained a CCAA nucleotide repeat. Testing of mutants expressing the HgbA, HgbB, and HgbC proteins individually revealed that expression of any one of these proteins was sufficient to allow wild-type growth with hemoglobin. In contrast, mutants that expressed only HgbA or HgbC grew significantly better with hemoglobin-haptoglobin than did a mutant expressing only HgbB. Construction of an isogenic hgbA hgbB hgbC mutant revealed that the absence of these three gene products did not affect the ability of NTHI N182 to utilize hemoglobin as a source of heme, although this mutant was severely impaired in its ability to utilize hemoglobin-haptoglobin. The introduction of a tonB mutation into this triple mutant eliminated its ability to utilize hemoglobin, indicating that the pathway for hemoglobin utilization in the absence of HgbA, HgbB, and HgbC involved a TonB-dependent process. Inactivation in this triple mutant of the hxuC gene, which encodes a predicted TonB-dependent outer membrane protein previously shown to be involved in the utilization of free heme, resulted in loss of the ability to utilize hemoglobin. The results of this study reinforce the redundant nature of the heme acquisition systems expressed by H. influenzae.

One of the primary phenotypic traits that distinguishes Haemophilus influenzae from the vast majority of other gram-negative bacteria is its absolute requirement for exogenously supplied heme for aerobic growth (8). H. influenzae lacks several genes which encode enzymes (8) necessary for the conversion of δ-aminolevulinic acid to protoporphyrin IX, the immediate biosynthetic precursor of heme (10, 11, 31, 35). In contrast to other bacteria that can utilize heme as a source of iron, H. influenzae requires the protoporphyrin component of heme (8). At least in vitro, free heme can satisfy the porphyrin requirements (11) and, in part, the iron requirements (7) of this organism.

Heme acquisition by H. influenzae growing in vivo is a much more complicated situation. The vast majority of heme in the body is contained within cells, either in hemoglobin or bound, in covalent or noncovalent fashion, to various cytochromes and enzymes. Heme released from human cells will be immediately bound by either albumin (Kd, 10−8 M) or hemopexin, a serum glycoprotein that binds heme avidly (Kd, 10−13 M) (16, 28). In practical terms, all circulating heme will be complexed to hemopexin under normal physiologic conditions because this glycoprotein has a much greater affinity for heme than does albumin. A similar situation exists for hemoglobin in that while free hemoglobin can be utilized readily by H. influenzae growing in vitro, the small amount of circulating free hemoglobin (i.e., that not present in erythrocytes) is tightly complexed (Kd, ∼10−23 M) by the serum protein haptoglobin (2). However, it has been well established that H. influenzae can readily utilize many protein-bound forms of heme, including hemoglobin-haptoglobin (30).

A previous study from our laboratory identified three outer membrane proteins of nontypeable H. influenzae (NTHI) strain N182 which had in common the facts that they were encoded by open reading frames (ORFs) that contained a tetranucleotide repeat (i.e., CCAA) and yielded fusion proteins that bound hemoglobin or hemoglobin-haptoglobin in vitro (3). Two of these proteins, HgbA and HgbB, were shown to exhibit phase variation. Additional data from this previous study and work from another laboratory (21, 22, 24, 25) indicated that individual H. influenzae strains likely possess a family of phase-variable TonB-dependent proteins which are involved in the utilization of heme contained in hemoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin.

Construction of an isogenic mutant unable to express any of the three hemoglobin-binding proteins expressed by H. influenzae type b strain HI689 did not eliminate the ability of this strain to utilize hemoglobin (22). This finding indicated the existence of an alternative mechanism(s) in H. influenzae for the acquisition of heme from hemoglobin. In the present study, we used mutant analysis to prove that this alternative system is TonB dependent. In addition, we have identified the outer membrane protein involved in this alternative hemoglobin utilization system as the HxuC outer membrane protein previously implicated in the utilization of very low levels of free heme by H. influenzae growing in vitro (6). Finally, we determined the relative abilities of the individual HgbA, HgbB, and HgbC outer membrane proteins to allow utilization of both hemoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin by H. influenzae.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and growth conditions.

The wild-type NTHI strain N182 (5) and H. influenzae Rd strain DB117 (29) have been described previously. These two strains as well as the mutant NTHI strains constructed in this study are described in Table 1. All H. influenzae strains were cultured routinely in brain heart infusion medium (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) with NAD (10 μg/ml) (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) (BHI) and hemin chloride at a final concentration of 10 μg/ml (BHI-10 Hm). For solidified media, hemin chloride was used at a final concentration of 10 or 50 μg/ml (BHI-50 Hm). NTHI strains were also grown in BHI with human hemoglobin (Sigma). The final concentration of hemoglobin was 3 μg/ml (BHI-3 Hg) for broth media and 100 μg/ml (BHI-100 Hg) for solidified media. Human haptoglobin (Calbiochem-Novabiochem, San Diego, Calif.) was loaded with human hemoglobin and purified by column chromatography. NTHI strains were grown on solidified BHI medium onto which human hemoglobin-haptoglobin (20 μg/ml) was spread (BHI-20 Hg-Hpt) or in BHI broth containing human hemoglobin-haptoglobin (2.5 μg/ml) (BHI-2.5 Hg-Hpt). These concentrations of hemoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin were determined empirically to allow growth of the wild-type N182 strain in broth and on solidified media; these concentrations were at most twofold greater than the concentration of each compound found to be limiting for growth of this wild-type strain. All broth cultures were incubated at 37°C with aeration; agar-solidified media were incubated at 37°C in an atmosphere of 95% air–5% CO2. H. influenzae media were supplemented when needed with tetracycline (5 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (0.5 μg/ml), erythromycin (5 μg/ml), kanamycin (30 μg/ml), or spectinomycin (150 μg/ml). Escherichia coli strain DH5α and recombinants derived from it were grown at 37°C on Luria-Bertani medium (26) supplemented with tetracycline (15 μg/ml), chloramphenicol (30 μg/ml), erythromycin (200 μg/ml), kanamycin (30 μg/ml), or spectinomycin (150 μg/ml) as needed.

TABLE 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Description | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| H. influenzae | ||

| DB117 | H. influenzae Rd strain, rec-1 | 29 |

| N182 | Wild-type NTHI strain | 5 |

| N182.11 | Isogenic N182 hgbA mutant containing an Ω chloramphenicol resistance cartridge inserted at the XhoI site in the hgbA gene | This study |

| N182.12 | Isogenic N182 hgbB mutant containing an erythromycin resistance cartridge inserted at the NcoI site in the hgbB gene | This study |

| N182.13 | Isogenic N182 hgbC mutant containing a kanamycin resistance cartridge inserted at the XhoI site in the hgbC gene | This study |

| N182.14 | Isogenic N182 hgbA hgbB mutant | This study |

| N182.15 | Isogenic N182 hgbA hgbC mutant | This study |

| N182.16 | Isogenic N182 hgbB hgbC mutant | This study |

| N182.17 | Isogenic N182 hgbA hgbB hgbC mutant | This study |

| N182.18 | Isogenic N182 hgbA hgbC mutant constructed by introducing the hgbA mutation into N182.13 | This study |

| N182.100 | Isogenic N182 mutant containing a spectinomycin resistance cartridge inserted at the SspI site in the hxuC gene | This study |

| N182.114 | Isogenic N182 hgbA hgbB hxuC mutant | This study |

| N182.115 | Isogenic N182 hgbA hgbC hxuC mutant | This study |

| N182.116 | Isogenic N182 hgbB hgbC hxuC mutant | This study |

| N182.117 | Isogenic N182 hgbA hgbB hgbC hxuC mutant | This study |

| N182.217 | Isogenic N182 hgbA hgbB hgbC mutant with a spectinomycin resistance cartridge inserted into the SspI site in the tonB gene | This study |

| N182.317 | Isogenic N182 hgbA hgbB hgbC mutant with a spectinomycin resistance cartridge inserted into the ScaI site in the tdhA gene | This study |

| E. coli DH5α | Host strain used for cloning experiments | 26 |

| Plasmids | ||

| pLDC300 | Previously designated pHgbA-FP; expresses β-lactamase–HgbA fusion protein | 3 |

| pLDC400 | Previously designated pHgbB-FP; expresses β-lactamase–HgbB fusion protein | 3 |

| pLDC500 | Previously designated pHgbC-FP; expresses β-lactamase–HgbC fusion protein | 3 |

| pLDC301 | pLDC300 with an Ω chloramphenicol resistance cartridge inserted at the XhoI site in the partial hgbA ORF | This study |

| pLDC401 | pLDC400 with an erythromycin resistance cartridge inserted at the NcoI site in the partial hgbB ORF | This study |

| pLDC501 | pLDC500 with a kanamycin resistance cartridge inserted at the XhoI site in the partial hgbC ORF | This study |

| pLDC600 | pCR-Blunt II-TOPO containing the N182 tonB gene | This study |

| pLDC601 | pLDC600 with a spectinomycin resistance cartridge inserted into the SspI site in the tonB ORF | This study |

| pLDC700 | pCR-Blunt II-TOPO containing a 2-kb incomplete N182 hxuC ORF | This study |

| pLDC701 | pLDC700 with a spectinomycin resistance cartridge inserted into the SspI site in the partial hxuC ORF | This study |

| pLDC800 | pCR-Blunt II-TOPO containing a 1.8-kb incomplete N182 tdhA ORF | This study |

| pLDC801 | pLDC800 with a spectinomycin resistance cartridge inserted into the ScaI site in the partial tdhA ORF | This study |

| pGJB103 | Cloning vector capable of replication in E. coli and H. influenzae | 1 |

| pHXUC-1 | pGJB103 containing the 2.4-kb N182 hxuC gene | This study |

Recombinant DNA methods.

Standard recombinant DNA methods including restriction enzyme digestions, alkaline phosphatase reactions, ligation reactions, Klenow fragment fill-in reactions, agarose gel electrophoresis, and plasmid purification were performed as described previously (26) or according to the manufacturer's instructions. Restriction enzymes and Klenow fragment were purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, Mass). Shrimp alkaline phosphatase was purchased from U.S. Biochemical (Cleveland, Ohio). T4 DNA ligase was purchased from GIBCO-BRL (Bethesda, Md.). Plasmid DNA was prepared with the Wizard Plus Miniprep DNA purification system (Promega, Madison, Wis.). Chromosomal DNA was isolated by the method of Marmur (19).

PCR.

PCR was performed with a GeneAmp XL PCR kit (Perkin-Elmer Corp., Foster City, Calif.) or Pfu DNA polymerase kit (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.). PCR products generated for nucleotide sequence analysis were purified by agarose gel electrophoresis. The Wizard PCR DNA purification system (Promega) was used to extract the DNA from the gel according to the manufacturer's directions.

Plasmid construction.

The recombinant plasmids pHgbA-FP, pHgbB-FP, and pHgbC-FP have been described elsewhere (3) and were designated pLDC300, pLDC400, and pLDC500, respectively, in this study (Table 1). Plasmid pLDC301 was constructed by ligation of a blunt-ended 3.8-kb BamHI fragment containing the chloramphenicol resistance gene from pHP-45 Ω Cm (9) into a blunt-ended XhoI site in the partial hgbA ORF within pLDC300. Plasmid pLDC401 was constructed by ligation of a blunt-ended 1.1-kb ClaI-HindIII fragment containing the erythromycin resistance gene from pIM13 (20) into the blunt-ended NcoI site within the partial hgbB ORF in pLDC400. Plasmid pLDC501 was constructed by ligation of a blunt-ended 1.3-kb EcoRI fragment containing the kanamycin resistance gene (Pharmacia, Piscataway, N.J.) into the blunt-ended XhoI site within the partial hgbC ORF in pLDC500.

The NTHI N182 hxuC gene was amplified by PCR from chromosomal DNA using the oligonucleotide primers 5′-AACTGCAGCTTATTTAGTCCAATTTTTGCAGG-3′ and 5′-AA CTGCAGCAATAACAGAATAACGAGGTCTC-3′; the underlined sequence indicates the addition of a PstI site. The 2.4-kb PCR product was digested to completion with PstI and then ligated into the PstI site in pGJB103. This ligation reaction was used to electroporate H. influenzae strain DB117 as described elsewhere (17); one of the tetracycline-resistant transformants was used as the source of plasmid pHXUC-1. Both pHXUC-1 and pGJB103 were used to electroporate various NTHI strains which were subsequently used in complementation analysis.

The NTHI N182 tonB gene was amplified by PCR using primers 5′-CCAAGAATCTACTCCCTCCCAGTC-3′ and 5′-GCTGAACCACCAATGGATG-3′; this 1-kb fragment was cloned into the pCR-Blunt II-TOPO vector with the Zero Blunt TOPO PCR Cloning Kit (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.) and designated pLDC600. A 1.2-kb EcoRV fragment from pSPECR (34) containing a spectinomycin resistance gene cartridge was inserted into the SspI site in the tonB gene; this plasmid was designated pLDC601. An incomplete hxuC ORF was amplified by PCR from N182 chromosomal DNA using the primers 5′-AGTCATTGATGGCGTGAG-3′ and 5′-CGGTTCAATGATCCAGTATC-3′; this 2-kb DNA fragment was cloned into the pCR-Blunt II-TOPO vector, and the resultant plasmid was designated pLDC700. The spectinomycin resistance cartridge described above was introduced in the SspI site in the partial hxuC ORF, and this plasmid was designated pLDC701.

The oligonucleotide primers 5′-GAAAACCAGAAAATAGGTGG-3′ and 5′-GGAATTCCGATAAAGCCCGATTAGATTC-3′ were used in PCR together with NTHI strain N182 chromosomal DNA to produce a 1.8-kb product containing a partial ORF whose predicted protein was most similar to the TdhA protein of H. ducreyi (32). This fragment was cloned into the pCR-Blunt II-TOPO vector and was designated pLDC800. The 1.2-kb EcoRV fragment containing the spectinomycin resistance gene described above was inserted at the ScaI site in the partial tdhA ORF in pLDC800; this new construct was designated pLDC801.

Construction of isogenic N182 mutants.

Construction of isogenic mutants of NTHI strain N182 was accomplished by allelic exchange. Plasmids pLDC301 and pLDC401 were digested with PstI, and pLDC501 was digested with AlwNI; these digestion mixtures were used to transform various NTHI strains by the Mrv method of Herriott et al. (13). The tonB mutation was introduced into the NTHI strain N182.17 by transforming it with a SmaI digest of pLDC601. The hxuC mutation was introduced into NTHI strains by transforming these strains with a SmaI digest of pLDC701. The mutated tdhA gene was introduced into NTHI strain N182.17 by transforming this mutant with a SmaI digest of pLDC801.

Nucleotide sequence analysis.

Selected DNA fragments and PCR products were sequenced with a model 373A automated DNA sequencer (PE Biosystems, Foster City, Calif.). Chromosomal DNA from the isogenic hgbB mutant N182.12 was used in a PCR to determine the number of CCAA tetranucleotide repeats in the hgbC ORF. The PCR product was generated with the primers 5′-TTCCACAACACTGTGACGC-3′ and 5′-ATTTCACCCTCGCTACCAG-3′; only the CCAA repeat region was sequenced in this PCR product. DNA sequence information was analyzed by using the Mac Vector analysis package (version 6.5; Oxford Molecular Group, Campbell, Calif.).

Preparation of outer membrane vesicles and sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis.

Outer membrane vesicles were prepared from broth-grown NTHI cells as described elsewhere (12). Whole-cell lysates were generated from NTHI N182 and its isogenic mutants as previously described (23). Western blot analysis was accomplished using the N182 HgbA-specific monoclonal antibody (MAb) 17H3, the N182 HbgB-specific MAb 4B3, the N182 HgbC-reactive MAb 12A2 (3), and polyclonal mouse HxuC antiserum. To obtain this polyclonal antiserum to the N182 HxuC protein, the synthetic peptide RETRFKQTAPSNNEVENELTNK was covalently bound to keyhole limpet hemocyanin (Sigma) and used to immunize mice. The sequence of this peptide corresponds to amino acid residues 238 to 259 of the N182 HxuC protein.

Evaluation of the ability of NTHI strains to utilize heme sources.

N182 and its isogenic mutants were initially tested for the ability to form individual colonies on solidified medium. Prior to inoculation of the test medium, each strain was passaged twice on BHI-100 Hg except for the hgbA hgbC hxuC mutant N182.115, the hgbA hgbB hgbC hxuC mutant N182.117, and the hgbA hgbB hgbC tonB mutant N182.217. These latter three strains were unable to form single colonies with hemoglobin as the sole source of heme and therefore were passaged twice on BHI-50 Hm. All strains were then streaked for single colony isolation on BHI-50 Hm, BHI-10 Hm, BHI-100 Hg, and BHI-20 Hg-Hpt plates. Recombinant strains containing plasmids were grown on solidified media containing tetracycline. This experiment was performed at least twice with all strains listed in Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Growth of wild-type and mutant NTHI strains with different heme sources

| Strain | Colony developmenta on:

|

Protein expression

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BHI-50 Hm | BHI-10 Hm | BHI-100 Hg | BHI-20 Hg-Hpt | HgbA | HgbB | HgbC | HxuC | |

| N182 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | + | + | + | + |

| N182.11 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | − | + | + | + |

| N182.12 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | + | − | − | + |

| N182.13 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | + | + | − | + |

| N182.14 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | − | − | + | + |

| N182.15 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | − | + | − | + |

| N182.16 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | + | − | − | + |

| N182.17 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | − | − | − | + |

| N182.217 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | − | − | − | + |

| N182.114 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | − | − | + | − |

| N182.115 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | − | + | − | − |

| N182.116 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | + | − | − | − |

| N182.117 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | − | − | − | − |

| N182.100 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | + | + | + | − |

| N182.100(pGJB103) | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | + | + | + | − |

| N182.100(pHXUC-1) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | + | + | + | + |

| N182.115(pGJB103) | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | − | + | − | − |

| N182.115(pHXUC-1) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2 | − | + | − | + |

| N182.117(pGJB103) | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | − | − | − | − |

| N182.117(pHXUC-1) | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | − | − | − | + |

Bacterial growth was scored after 24 h of incubation as 3 (single colonies in the tertiary part of the streak pattern), 2 (single colonies in the secondary part of the streak pattern), 1 (single colonies or a haze in the primary part of the streak pattern), or 0 (no growth).

The rate and extent of growth of wild-type, mutant, and recombinant NTHI strains was assessed in a broth medium consisting of BHI supplemented with various heme sources. Each strain was passaged twice on BHI-50 Hm agar plates. Cells from the second passage were then starved for heme by inoculating them into 10 ml of BHI in a 16- by 150-mm glass culture tube held in an ice-water slurry in a large bucket (4). This bucket was placed in an environmental room at 37°C for 14 to 16 h; the use of the ice slurry delayed the start of growth for several hours. The next morning, the 10-ml culture was transferred into a 500-ml flask and agitated at 37°C for 3 h. The cells were then collected by centrifugation at 1,668 × g for 5 min at room temperature and suspended in 1 ml of BHI. Portions (30 to 50 μl) of this suspension were inoculated into 500-ml flasks containing 10 ml of BHI, BHI-10 Hm, BHI-3 Hg, and BHI-2.5 Hg-Hpt to obtain a final suspension that yielded a reading of 30 to 35 Klett units in a Klett-Summerson colorimeter (Klett Mfg. Co., New York, N.Y.). These cultures were incubated at 37°C with agitation, and the rate and extent of growth were measured turbidimetrically.

Detection of hemoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin binding activity. (i) Membrane-based assay.

Each strain was passaged twice on BHI-100 Hg agar plates and then inoculated into a 500-ml flask containing 10 ml of BHI to a final concentration that yielded a Klett reading of 100. Each flask was incubated for 6 h at 37°C with agitation. The cells were then collected by centrifugation as described immediately above, suspended in 1 ml of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and then centrifuged again. The final cell pellet was suspended in 0.5 ml of PBS and then diluted with PBS to obtain a final suspension that yielded a Klett reading of 200. A total of 200 μl (in 50-μl portions) was added to each of two wells in a Minifold I dot blot apparatus (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, N.H.). The nitrocellulose membranes containing these cells were dried at room temperature for 15 min and then incubated in PBS containing 0.5% (vol/vol) Tween 20 (PBS-T) and 3% (wt/vol) skim milk for 1 h at room temperature. The membranes were then incubated with radioiodinated hemoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin (18) overnight at 4°C in the same buffer. The membranes were washed three times in PBS-T, dried, and processed for autoradiography.

(ii) Liquid phase assay.

The cells were passaged twice on BHI-100 Hg or BHI-50 Hm agar plates and were then inoculated into BHI as described above. After the 6-h incubation period, the cells were washed as described above except that the final suspension of cells was adjusted to 100 Klett units in PBS containing 1% (wt/vol) bovine serum albumin (BSA). A 1.5-ml volume of this suspension was centrifuged, and then the pellet was suspended in 150 μl of PBS-BSA. All assays were performed in triplicate at 4°C. A 50-μl portion of this suspension (5 × 108 CFU) was mixed with radioiodinated hemoglobin, and a 5-μl portion of this suspension (5 × 107 CFU) was mixed with radioiodinated hemoglobin-haptoglobin in a 96-well Multiscreen filtration plate (Millipore). PBS-BSA was added to final volume of 150 μl. This plate was incubated on a rocker platform for 15 min, at which time the plate was placed on the vacuum apparatus and the liquid was removed by application of vacuum. The cells were washed four times with 200 μl of PBS-BSA, and suspended in 200 μl of PBS-BSA, and transferred to a glass tube, and the associated radioactivity was measured in a gamma counter. Background binding of hemoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin to the wells was measured and subtracted from the experimental values.

Determination of the concentration of free heme in hemoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin.

An aliquot of the sample of hemoglobin (and hemoglobin-haptoglobin) solution used for the broth growth assays was diluted to 3.0 ml in 0.1 M potassium phosphate (pH 7.4), and the absorbance spectrum was recorded using an Aminco-Chance DW2 spectrophotometer adapted with the Olis spectroscopy operating system. An extinction coefficient of 169 mM−1 cm−1 at 405 nm was used to calculate the concentration of methemoglobin. A few crystals of sodium dithionite were added to reduce methemoglobin, and the sample was gassed for 1 min with a stream of carbon monoxide. The spectrum was recorded, and an extinction coefficient of 192 mM−1 cm−1 was used to determine the concentration of carbon monoxyhemoglobin (14). The concentration of total heme in the sample was determined by diluting an aliquot with 0.6 M NaOH followed by an equal volume of pyridine to give final concentrations of 0.2 M NaOH and 20% pyridine, respectively. The pyridine-treated sample was divided into two cuvettes, and the base line of equal absorbance was recorded. A few crystals of sodium dithionite were added to the contents of the sample cuvette, and the difference spectrum of the reduced hemochromogen minus the oxidized hemochromogen was recorded. The concentration of total heme in the sample was calculated from the difference in absorbance at 557 nm relative to 575 nm, using an extinction of 32.4 mM−1 cm−1 (27). The concentration of free heme in the sample was calculated as the difference in concentration of total heme (determined by the pyridine hemochromogen method) minus the concentration of hemoglobin (determined as carbon monoxyhemoglobin).

RESULTS

Construction and characterization of isogenic mutants.

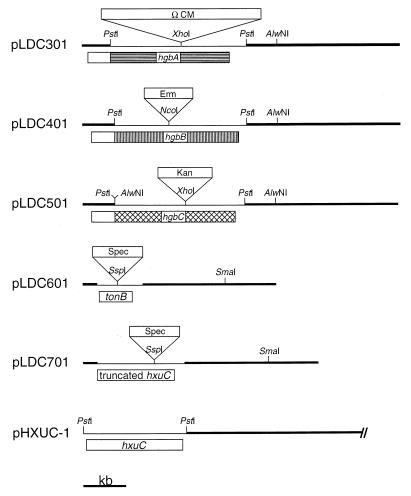

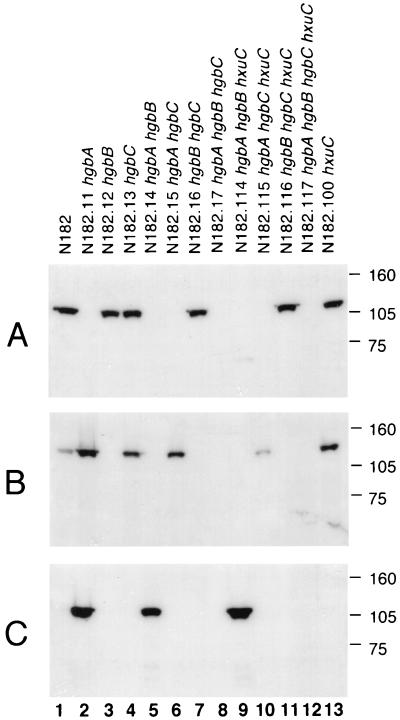

To determine which of the hgbA, hgbB, and hgbC gene products were involved in the utilization of hemoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin, the appropriate NTHI strain N182 mutants were constructed as described in Materials and Methods. These included strains with a mutation in only a single gene (hgbA, hgbB, or hgbC), strains with two mutations (hgbA hgbB, hgbA hgbC, and hgbB hgbC), and a strain with three mutations (hgbA hgbB hgbC) (Table 1 and Fig. 1). The proper construction of each mutant was confirmed by Southern blot analysis (data not shown). Western blot analysis was used to detect expression of the individual gene products by each strain. The hgbA mutant N182.11 did not express detectable HgbA protein but did express both HgbB and HgbC (Fig. 2, lane 2). The hgbB mutant N182.12 expressed HgbA and, as expected, did not express HgbB (Fig. 2, lane 3). This hgbB mutant also did not express HgbC (Fig. 2C, lane 3), and nucleotide sequence analysis revealed that the number of CCAA nucleotide repeats in the hgbC ORF of this mutant had apparently been altered by slipped-strand mispairing and would not allow expression of HgbC. The hgbC mutant N182.13 expressed both HgbA and HgbB but not HgbC (Fig. 2, lane 4). It should be noted that the wild-type strain N182 did not express detectable HgbC protein (Fig. 2, lane 1); little or no expression of HgbC by unselected populations of N182 has been previously described (3).

FIG. 1.

Restriction maps of the various wild-type and mutated H. influenzae genes used in this study. Plasmid pLDC301 is pLDC300 with an Ω chloramphenicol resistance cartridge inserted into the XhoI site within the hgbA ORF, pLDC401 is pLDC400 with an erythromycin resistance cartridge inserted into the NcoI site within the hgbB ORF, and pLDC501 is pLDC500 with a kanamycin resistance cartridge inserted into the XhoI site within the hgbC ORF. Plasmid pLDC601 is pLDC600 with a spectinomycin resistance cartridge inserted into the SspI site within the NTHI N182 tonB gene. Plasmid pLDC701 is pLDC700 with a spectinomycin resistance cartridge inserted into the SspI site within the truncated hxuC ORF. Plasmid pHXUC-1 is pGJB103 containing the NTHI N182 hxuC gene; only the relevant region of pHXUC-1 is depicted. A kilobase size marker is shown at the bottom.

FIG. 2.

Western blot-based detection of the HgbA, HgbB, and HgbC proteins in wild-type strain N182 and related mutants. Equivalent amounts of whole-cell lysate from these strains were probed with the HgbA-specific MAb 17H3 (A), the HgbB-specific MAb 4B3 (B), and the HgbC-reactive MAb 12A2 (C). Molecular markers (in kilodaltons) are shown at the right.

Each of the mutants carrying two mutations expressed only a single hgb gene product, with the hgbA hgbB mutant N182.14 expressing only HgbC (Fig. 2, lane 5), the hgbA hgbC mutant N182.15 expressing only HgbB (Fig. 2, lane 6), and the hgbB hgbC mutant N182.16 expressing only HgbA (Fig. 2, lane 7). As expected, the hgbA hgbB hgbC mutant N182.17 did not express any of the Hgb proteins (Fig. 2, lane 8).

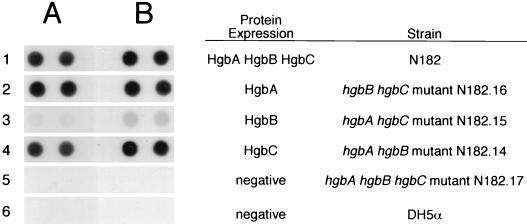

Binding of hemoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin.

It was previously shown that NTHI strain N182 HgbA, HgbB, and HgbC fusion proteins would bind hemoglobin, with the HgbA and HgbC fusion proteins apparently binding more hemoglobin than the HgbB fusion protein (3). The construction in the present study of N182 mutants expressing only HgbA, HgbB, or HgbC provided the opportunity to assess binding of these heme compounds by the different Hgb proteins in their native background.

The hgbB hgbC mutant expressing only the HgbA protein (Fig. 3, row 2) and the hgbA hgbB mutant expressing only HgbC (Fig. 3, row 4) both bound hemoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin. The hgbA hgbC mutant expressing only HgbB bound hemoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin weakly (Fig. 3B, row 3). The wild-type parent strain (Fig. 3, row 1) bound both heme compounds, whereas the hgbA hgbB hgbC mutant (Fig. 3, row 5) bound neither compound. E. coli DH5α (Fig. 3, row 6), used here as a negative control, did not bind either hemoglobin or hemoglobin-haptoglobin.

FIG. 3.

Binding of hemoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin by wild-type and mutant NTHI strains. Cells (2 × 108 to 4 × 108 CFU) were spotted in duplicate on nitrocellulose and incubated with radioiodinated hemoglobin (A) or hemoglobin-haptoglobin (B). Protein expression was determined by Western blot analysis of lysates of these same cells, using the MAbs described in the legend to Fig. 2 to detect HgbA, HgbB, and HgbC. Expression of HgbC by wild-type strain N182 was very low, as described before for unselected populations of N182 cells (3).

The poor binding ability of the HgbB protein and the apparent lack of binding of hemoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin obtained with the hgbA hgbB hgbC mutant could have been the result of the use of dried cells in this binding assay. Therefore, the binding assays were repeated with cells suspended in liquid. The results were very similar to those obtained with the dried cells in that the mutant expressing only HgbB bound much less hemoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin than did the wild-type parent strain or the mutants expressing only HgbA or HgbC (Table 2). Again, the hgbA hgbB hgbC mutant did not bind either compound (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Binding of radiolabeled hemoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin to wild-type and mutant strains

| Passage in the presence of: | Strain | cpm associated with cells

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin | Hemoglobin-haptoglobin | ||

| Hemoglobina | N182 | 12,506 ± 3,551 | 3,746 ± 1,686 |

| N182.14 | 14,363 ± 1,892 | 4,163 ± 318 | |

| N182.15 | 558 ± 326 | 503 ± 111 | |

| N182.16 | 12,668 ± 987 | 3,218 ± 331 | |

| N182.17 | 114 ± 28 | 59 ± 59 | |

| DH5α | 39 ± 27 | 1 ± 2 | |

| Hemeb | N182 | 14,382 ± 3,715 | 3,991 ± 1,841 |

| N182.17 | 47 ± 39 | 7 ± 9 | |

| N182.117 | 20 ± 1 | 12 ± 17 | |

Bacterial strains (for genotypes, see Table 1) were passaged twice on solidified medium containing hemoglobin (100 μg/ml) prior to heme starvation.

Bacterial strains were passaged twice on solidified medium containing heme (50 μg/ml) prior to heme starvation.

The fact that the hgbA hgbC mutant (which expressed only HgbB) bound hemoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin to a much lesser extent than did the hgbA hgbB and hgbB hgbC mutants (Fig. 3) raised the possibility that the hgbB gene in this construct might contain a new mutation that reduced the ability of the encoded protein to bind these compounds. Alternatively, this construct might have contained a second-site mutation that impeded the interaction between HgbB and these heme carriers. To eliminate the first possibility, the nucleotide sequence of the hgbB gene in the hgbA hgbC mutant was determined and found to be identical to that in the wild-type N182 parent strain. To address the second possibility, another hgbA hgbC mutant was constructed by introducing the hgbA mutation into the hgbC mutant. The resultant second hgbA hgbC mutant, N182.18, displayed the same very weak binding of both hemoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin (data not shown) as did the original hgbA hgbC mutant N182.15.

Utilization of heme compounds by wild-type and mutant NTHI strains.

Preliminary testing of the ability of the wild-type and hgb mutant NTHI strains to utilize free heme, hemoglobin, and hemoglobin-haptoglobin involved assessment of colony development on solidified agar media. The wild-type strain and all of the mutants described above were able to readily form individual colonies when inoculated onto media containing free heme at final concentrations of 50 and 10 μg/ml (Table 3). Similarly, the wild-type strain (Fig. 4A and Table 3) and all of these mutants, including the hgbA hgbB hgbC triple mutant (Fig. 4B and Table 3), readily formed individual colonies when hemoglobin (100 μg/ml) was used as the heme source. The hgbA hgbB hgbC triple mutant, however, was impaired in the ability to form colonies on media containing hemoglobin-haptoglobin (Fig. 4F) compared to the wild-type strain (Fig. 4E).

FIG. 4.

Growth of wild-type and mutant NTHI strains on agar plates containing hemoglobin or hemoglobin-haptoglobin as the sole source of heme. The indicated strains were streaked onto BHI-100 Hg or BHI-20 Hg-Hpt agar plates as indicated and incubated for 24 h.

The finding that the hgbA hgbB hgbC triple mutant still utilized hemoglobin despite its apparent inability to bind this compound in the dot blot assay (Fig. 3A, row 5) indicated that this mutant possessed an additional mechanism for the acquisition of heme from hemoglobin. A previous study from this laboratory (15) showed that utilization of hemoglobin by H. influenzae was dependent on the activity of the TonB protein. To determine whether this additional, unidentified mechanism was TonB dependent, the tonB gene from NTHI strain N182 was amplified by PCR, inactivated by insertion of a spectinomycin resistance cartridge, and used to construct a hgbA hgbB hgbC tonB mutant (N182.217). Inactivation of the tonB gene in this mutant was confirmed by its inability to utilize low levels of free heme (10 μg/ml) for growth on solidified media while still being able to utilize free heme at a much higher concentration (50 μg/ml) (15) (Table 3). The hgbA hgbB hgbC tonB mutant was also unable to form individual colonies with hemoglobin as the sole source of heme (Fig. 4C), a finding which indicated that the growth of the hgbA hgbB hgbC mutant with hemoglobin (Fig. 4B) was a TonB-dependent process.

Identification of the TonB-dependent protein involved in hemoglobin utilization by the triple mutant.

Examination of the H. influenzae Rd genome (10) revealed the presence of several genes encoding predicted products which were likely to be TonB-dependent outer membrane proteins. Some of these gene products had already been determined to function in specific processes (e.g., transferrin binding protein I encoded by ORF HI0994), whereas others (e.g., the predicted protein encoded by ORF HI0113) did not have a proven function. To determine whether one of these proteins was involved in the utilization of hemoglobin by the hgbA hgbB hgbC mutant, we focused on two classes of these genes. The first, as exemplified by HI0113, encoded a predicted protein product that was most similar to a protein (TdhA) proposed to be involved in heme utilization by another organism, H. ducreyi (32). The second class of genes, as exemplified by hxuC, encoded proteins known to be involved in the utilization of free heme by H. influenzae (6). Inactivation of the tdhA homolog in the hgbA hgbB hgbC triple mutant did not affect the ability of this strain to utilize hemoglobin (data not shown). In contrast, inactivation of the hxuC gene in this same triple mutant eliminated its ability to utilize hemoglobin (Fig. 4D and Table 3).

The HxuC outer membrane protein of H. influenzae has previously been shown to be essential for the growth of this organism in the presence of very low concentrations of free heme (6). This fact raised the possibility that the hemoglobin used in these experiments was contaminated with free heme (i.e., heme in excess of that contained in hemoglobin) and that the observed growth of the hgbA hgbB hgbC mutant with hemoglobin was actually the result of the utilization of free heme via the HxuC protein. To address this possibility, the amount of free heme in both the hemoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin preparations was determined by spectrophotometric methods as described in Materials and Methods. The amount of free heme detected in the hemoglobin preparation was such that the BHI-3 Hg medium would contain free heme at a final concentration of less than 0.0125 μg/ml; there was no free heme detected in the hemoglobin-haptoglobin preparation. Wild-type NTHI strain N182 was not able to grow in BHI medium containing free heme at a final concentration of 0.0125 μg/ml (data not shown).

Effect of the hxuC mutation on utilization and binding of hemoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin.

The hxuC mutation was also introduced into wild-type strain N182 and the three double mutants which expressed only a single Hgb protein; all four of these strains still expressed their Hgb proteins (Fig. 2, lanes 9 to 11 and 13). The presence or absence of HxuC in each strain described below was confirmed by Western blot analysis using polyclonal mouse HxuC antiserum to probe proteins present in outer membrane vesicles prepared from NTHI cells grown in BHI-10 Hm or BHI-3 Hg broth (Table 3). The presence of only the hxuC mutation in the wild-type N182 strain eliminated the ability of this strain to utilize low levels of free heme (Table 3) as would have been predicted by a previous study (6). Introduction of the hxuC mutation into the hgbA hgbB and hgbB hgbC mutants did not affect the ability of these two strains to utilize either hemoglobin or hemoglobin-haptoglobin (Table 3). In contrast, elimination of the ability to express the HxuC protein in the hgbA hgbC double mutant reduced significantly its ability to utilize hemoglobin but did not have an apparent effect on hemoglobin-haptoglobin utilization (Table 3). Again, the hgbA hgbB hgbC hxuC mutant was unable to utilize hemoglobin (Table 3 and Fig. 4D).

The hgbA hgbB hgbC mutant was previously shown to be unable to bind either hemoglobin or hemoglobin-haptoglobin (Table 2). The presence of the hxuC mutation in this same strain did not alter the binding ability of this strain (Table 2) such that both the hgbA hgbB hgbC mutant and the hgbA hgbB hgbC hxuC mutant failed to bind either compound. This latter set of results suggests that HxuC does not bind either hemoglobin or hemoglobin-haptoglobin, at least under the in vitro assay conditions used in this study.

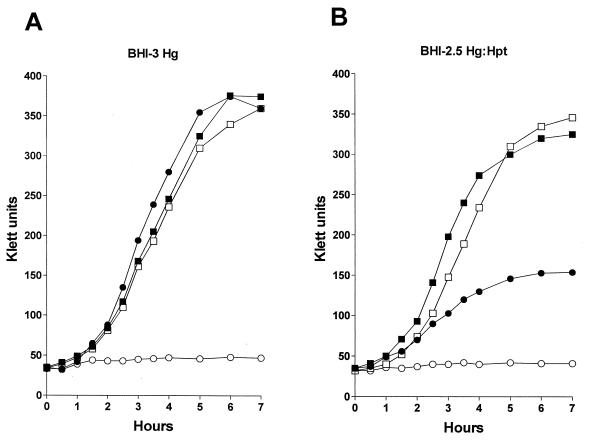

Growth of wild-type and mutant strains in broth.

A more quantitative assessment of the role of these various proteins in hemoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin utilization was obtained by measuring the rate and extent of growth of these strains in a liquid medium. Representative growth curves are depicted in Fig. 5 and 6. In the first set of experiments, wild-type strain N182, the hxuC mutant, the hgbA hgbB hgbC triple mutant, and the hgbA hgbB hgbC hxuC quadruple mutant were tested for their relative abilities to utilize hemoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin. Each inoculum was starved for heme (see Materials and Methods) prior to inoculation into the test media. All four strains grew at the same rate and to the same extent in the presence of excess heme (10 μg/ml) (data not shown). Similarly, all four strains failed to grow in the absence of a heme source (data not shown).

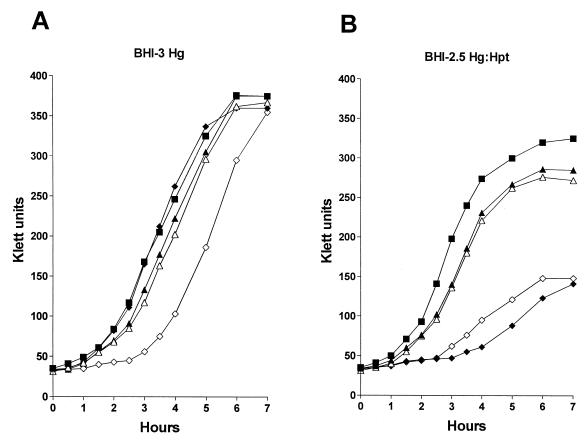

FIG. 5.

Growth of wild-type and mutant NTHI strains in broth containing hemoglobin or hemoglobin-haptoglobin. Wild-type strain N182 (■), the hgbA hgbB hgbC triple mutant N182.17 (●), the hxuC mutant N182.100 (□), and the hgbA hgbB hgbC hxuC quadruple mutant N182.117 (○) were starved for heme as described in Materials and Methods and then inoculated into either BHI-3 Hg (A) or BHI-2.5 Hg-Hpt (B).

FIG. 6.

Growth of wild-type and mutant NTHI strains in broth containing hemoglobin or hemoglobin-haptoglobin. Wild-type strain N182 (■), the hgbB hgbC mutant N182.16 (▴), the hgbB hgbC hxuC mutant N182.116 (▵), the hgbA hgbC mutant N182.15 (⧫), and the hgbA hgbC hxuC mutant N182.115 (◊) were starved for heme as described in Materials and Methods and then inoculated into either BHI-3 Hg (A) or BHI-2.5 Hg-Hpt (B).

The hgbA hgbB hgbC triple mutant grew similarly to the wild-type parent strain and the hxuC mutant with hemoglobin, whereas the hgbA hgbB hgbC hxuC quadruple mutant was unable to grow with hemoglobin (Fig. 5A). Both the wild-type strain and the hxuC mutant grew well with hemoglobin-haptoglobin in broth. However, the hgbA hgbB hgbC mutant grew much more slowly and to a lesser extent in broth with hemoglobin-haptoglobin (Fig. 5B); this same triple mutant was unable to form colonies on solidified media containing hemoglobin-haptoglobin (Table 3). As occurred with hemoglobin, the hgbA hgbB hgbC hxuC quadruple mutant failed to grow with hemoglobin-haptoglobin in broth (Fig. 5B).

Ability of individual Hgb proteins to allow utilization of heme compounds.

Mutants expressing only HgbA, HgbB, or HgbC were tested for their abilities to utilize both hemoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin. The hgbB hgbC mutant that expressed only HgbA grew at a rate and to a final density virtually identical to that of the wild-type strain with hemoglobin; the introduction of an hxuC mutation into this mutant had no obvious effect on its growth with hemoglobin (Fig. 6A). With hemoglobin-haptoglobin, both the hgbB hgbC mutant and the hgbB hgbC hxuC mutant grew nearly as well as the wild-type parent strain (Fig. 6B). The hgbA hgbC mutant that expressed only HgbB grew similarly to the wild-type strain with hemoglobin (Fig. 6A); introduction of the hxuC mutation into this mutant resulted in an increased lag period before the start of exponential growth (Fig. 6A). With hemoglobin-haptoglobin, both the hgbA hgbC and the hgbA hgbC hxuC mutants exhibited a significantly reduced growth ability (Fig. 6B). Testing of the hgbA hgbB and hgbA hgbB hxuC mutants (which expressed only HgbC) revealed that they grew at rates very similar to those of the wild-type parent strain with both heme sources described above (data not shown).

Complementation analysis.

In the various mutants described above, the mutation in the hxuC gene involved the insertion of a spectinomycin resistance cartridge, which could have exerted a polar effect on expression of the downstream hxuB and hxuA genes (6). The HxuB and HxuA gene products have been shown to be essential for utilization of heme contained in heme-hemopexin complexes by H. influenzae (4, 6).

To eliminate the possibility that polar effects on hxuB or hxuA expression could have resulted in the inability of the hgbA hgbB hgbC hxuC mutant to utilize hemoglobin, the wild-type N182 hxuC gene was cloned into pGJB103 for complementation analysis. Introduction of the recombinant plasmid pHXUC-1 into the hgbA hgbB hgbC hxuC mutant restored its ability to utilize hemoglobin but not hemoglobin-haptoglobin on solidified media (Table 3). This complemented mutant also was able to utilize low levels of free heme (Table 3), thus confirming expression of the HxuC protein in this construct. The presence of the pGJB103 vector alone in this same mutant strain had no effect on its ability to utilize either hemoglobin or hemoglobin-haptoglobin on solidified media (Table 3).

Similar results were obtained when the N182 hxuC gene was provided in trans in the hgbA hgbC hxuC mutant which had a greatly reduced ability to utilize hemoglobin (Table 3). The presence of pHXUC-1 in this mutant resulted in wild-type development of individual colonies with hemoglobin as the sole source of heme but again did not affect the inability of this mutant to utilize hemoglobin-haptoglobin on solidified media (Table 3). Again, the presence of the wild-type hxuC gene in this complemented mutant allowed it to grow with low levels of free heme (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

Among gram-negative bacterial pathogens, utilization of hemoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin as sources of either heme or iron has generally been shown to involve outer membrane proteins that have in common the fact that they appear to be members of the TonB-dependent protein family (33). H. influenzae is no exception to this rule but is different from most of these other organisms in its expression of several outer membrane proteins with very similar amino acid sequences which function in the acquisition of heme from hemoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin. Each of the two H. influenzae strains (N182 and HI689) studied to date in this regard was shown to possess three ORFs encoding what are likely TonB-dependent outer membrane proteins which can bind hemoglobin or hemoglobin-haptoglobin. Expression of these proteins in both of these H. influenzae strains undergoes phase variation (3, 25).

The first objective of this study was to confirm the phenotype of an isogenic H. influenzae mutant unable to express any of the hemoglobin-binding outer membrane proteins encoded by ORFs containing the CCAA nucleotide repeat. In H. influenzae type b HI689, three ORFs (hbpA, hbpB, and hbpC) that contained CCAA repeats were shown to express hemoglobin-binding proteins with a high degree of similarity to the HgbA, HgbB, and HgbC proteins from NTHI strain N182. Morton et al. (22) reported that a hbpA hbpB hbpC triple mutant was still able to grow like the wild type with hemoglobin except when the hemoglobin concentration was reduced to a growth-limiting concentration. We similarly constructed an isogenic hgbA hgbB hgbC mutant from NTHI strain N182 and showed that this triple mutant still grew at the same rate and to the same extent as the wild-type parent strain with hemoglobin as the sole source of heme. The concentration of hemoglobin used in our study was just above the growth-limiting concentration for NTHI strain N182. This finding, which confirmed the results of Morton et al. (22) for a similar H. influenzae type b mutant, indicated that NTHI N182 can utilize hemoglobin independent of the expression of the protein products of the hgbA, hgbB, and hgbC genes. However, the introduction of a tonB mutation into this triple mutant rendered it unable to utilize hemoglobin (Table 3 and Fig. 4). This latter finding confirmed that this alternative hemoglobin utilization system in NTHI strain N182 still involved a TonB-dependent process.

Analysis of various additional mutants revealed that inactivation of expression of the HxuC protein in the N182 hgbA hgbB hgbC mutant resulted in the loss of the ability to utilize hemoglobin (Table 3; Fig. 4 and 5). Previous work from our laboratory indicated that hxuC was the first gene in the hxuCBA locus and encodes an outer membrane protein required for the utilization of very low levels of free heme by H. influenzae (6). The other two gene products of this locus are involved in the ability of H. influenzae to utilize heme bound to the serum protein hemopexin. More specifically, the HxuB outer membrane protein appears to be required for secretion of the soluble HxuA protein into culture supernatant fluid, where it binds heme-hemopexin complexes (4–6). The phenotype of an hxuC mutant was evidenced as an inability to utilize very low concentrations of free heme for aerobic growth in vitro (6), and there was no indication that the hxuC mutation had affected the ability of H. influenzae to utilize hemoglobin.

It should be noted that the N182 hgbA hbgB hgbC triple mutant lost the ability to bind hemoglobin (or hemoglobin-haptoglobin) at detectable levels in the binding assay used in this study (Fig. 3). The presence of the HxuC protein in this mutant, while allowing utilization of hemoglobin, did not permit detectable binding of hemoglobin in two different assay systems (Fig. 3 and Table 2). We confirmed that HxuC is expressed by this triple mutant when it is grown with hemoglobin, but the level of HxuC expression was not greater than that observed with the wild-type parent strain grown with hemoglobin (data not shown). Therefore, if HxuC is able to bind hemoglobin, then this activity was not detected in the binding assays used in this study. How HxuC facilitates the acquisition of heme from hemoglobin in the hgbA hgbB hgbC triple mutant is not apparent. At this time, we also cannot eliminate the possibility that a second gene product acting in concert with HxuC is involved in obtaining heme from hemoglobin.

It should also be noted that the N182 hgbA hgbB hgbC triple mutant was significantly impaired in its ability to grow in broth with hemoglobin-haptoglobin (Fig. 5B) and was unable to form individual colonies when grown on solidified medium with hemoglobin-haptoglobin (Table 3) even though this mutant could grow like the wild type with hemoglobin in liquid and on solid media. The modest growth response of this triple mutant in broth with hemoglobin-haptoglobin did involve the HxuC protein, however, because the hgbA hgbB hgbC hxuC quadruple mutant was unable to grow in broth with hemoglobin-haptoglobin (Fig. 5B).

We also investigated the relative abilities of the individual HgbA, HgbB, and HgbC proteins to allow H. influenzae to bind and utilize both hemoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin. Mutants expressing only HgbA or HgbC grew as well as the wild-type parent strain with hemoglobin (Table 3). In addition, the mutants expressing either HgbA or HgbC appeared to bind hemoglobin (and hemoglobin-haptoglobin) at a level equivalent to that obtained with the wild-type parent strain (Fig. 3 and Table 2). The mutant expressing only HgbB grew similarly to the wild type with hemoglobin but bound hemoglobin (and hemoglobin-haptoglobin) poorly relative to the mutants expressing only HgbA or HgbC. In addition, introduction of the hxuC mutation into this strain expressing only HgbB adversely affected its ability to utilize hemoglobin (Table 3 and Fig. 6A), whereas the presence of the hxuC mutation had no detectable effect on hemoglobin utilization by the strains expressing only HgbA (Fig. 6A) or HgbC (data not shown). Therefore, based on these in vitro studies, HgbB appears to be less efficient than HgbA and HgbC in its ability to allow H. influenzae to obtain heme from hemoglobin.

Expression of only HgbA (in the hgbB hgbC mutant) and only HgbC (in the hgbA hgbB mutant) limited slightly the ability of H. influenzae to utilize hemoglobin-haptoglobin (Fig. 6B and data not shown). In contrast, expression of only HgbB (by the hgbA hgbC mutant) had a significant deleterious effect on the ability of H. influenzae to utilize hemoglobin-haptoglobin (Fig. 6B). Inactivation of the hxuC gene in all three of these strains did not alter significantly their rate or extent of growth (Fig. 6B), suggesting that the observed growth responses with hemoglobin-haptoglobin did not involve the HxuC protein

In summary, we have shown that NTHI strain N182 can utilize hemoglobin either by means of the phase-variable HgbA, HgbB, and HgbC proteins or via the HxuC protein. In contrast, utilization of the heme in hemoglobin-haptoglobin occurs optimally in the presence of all three of the Hgb proteins, and lack of expression of these proteins severely inhibits the growth of NTHI strain N182 with this heme compound. In this latter situation, the very limited growth of the hgbA hgbB hgbC mutant in broth with hemoglobin-haptoglobin again involved the HxuC protein (Fig. 5B). These data reinforce the redundant nature of the heme acquisition systems expressed by H. influenzae.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by Public Health Service grant AI17621 to E.J.H.

We thank Sheryl Lumbley and Jo Latimer for technical assistance. We thank Jeffrey Weiser for providing the erythromycin resistance cartridge and Terrence Stull for sending the spectinomycin resistance cartridge. Finally, we thank the other members of this laboratory for their helpful comments and suggestions regarding the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barcak G J, Chandler M S, Redfield R J, Tomb J-F. Genetic systems in Haemophilus influenzae. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:321–342. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04016-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bowman B H, Barnett D R, Lum J B, Yang F. Haptoglobin. Methods Enzymol. 1988;163:452–474. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(88)63043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cope L D, Hrkal Z, Hansen E J. Detection of phase variation in expression of proteins involved in hemoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin binding by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4092–4101. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.7.4092-4101.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cope L D, Thomas S E, Hrkal Z, Hansen E J. Binding of heme-hemopexin complexes by soluble HxuA protein allows utilization of this complexed heme by Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4511–4516. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4511-4516.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cope L D, Thomas S E, Latimer J L, Slaughter C A, Muller-Eberhard U, Hansen E J. The 100 kDa heme:hemopexin-binding protein of Haemophilus influenzae: structure and localization. Mol Microbiol. 1994;13:863–873. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb00478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cope L D, Yogev R, Muller-Eberhard U, Hansen E J. A gene cluster involved in the utilization of both free heme and heme:hemopexin by Haemophilus influenzae type b. J Bacteriol. 1995;177:2644–2653. doi: 10.1128/jb.177.10.2644-2653.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coulton J W, Pang J C S. Transport of hemin by Haemophilus influenzae type b. Curr Microbiol. 1983;9:93–98. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Evans N M, Smith D D, Wicken A J. Haemin and nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide requirements of Haemophilus influenzae and Haemophilus parainfluenzae. J Med Microbiol. 1974;7:359–365. doi: 10.1099/00222615-7-3-359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fellay R, Frey J, Krisch H M. Interposon mutagenesis of soil and water bacteria: a family of DNA fragments designed for in vitro insertional mutagenesis of Gram negative bacteria. Gene. 1987;52:147–152. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(87)90041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fleischmann R D, Adams M D, White O, Clayton R A, Kirkness E F, Kerlavage A R, Bult C J, Tomb J-F, Dougherty B A, Merrick J M, McKenney K, Sutton G, FitzHugh W, Fields C, Gocayne J D, Scott J, Shirley R, Liu L-I, Glodek A, Kelley J M, Weidman J F, Phillips C A, Spriggs T, Hedblom E, Cotton M D, Utterback R C, Hanna M C, Nguyen D T, Saudek D M, Brandon R C, Fine L D, Fritchman J L, Fuhrmann J L, Geoghagen N S M, Gnehm C L, McDonald L A, Small K V, Fraser C M, Smith H O, Venter J C. Whole-genome random sequencing and assembly of Haemophilus influenzae Rd. Science. 1995;269:496–512. doi: 10.1126/science.7542800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Granick S, Gilder H. The porphyrin requirements of Haemophilus influenzae and some functions of the vinyl and propionic acid side chains of heme. J Gen Physiol. 1946;30:1–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hansen E J, Gonzales F R, Chamberlain N R, Norgard M V, Miller E E, Cope L D, Pelzel S E, Gaddy B, Clausell A. Cloning of the gene encoding the major outer membrane protein of Haemophilus influenzae type b. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2709–2716. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.10.2709-2716.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Herriott R M, Meyer E M, Vogt M J. Defined non-growth media for stage II development of competence in Haemophilus influenzae. J Bacteriol. 1970;101:517–524. doi: 10.1128/jb.101.2.517-524.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho C. Specific spectroscopic properties of hemoglobins. In: Antonini E, Rossi-Bernardi L, Chiancone E, editors. Hemoglobins. New York, N.Y: Academic Press; 1981. pp. 175–261. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jarosik G P, Sanders J D, Cope L D, Muller-Eberhard U, Hansen E J. A functional tonB gene is required for both utilization of heme and virulence expression by Haemophilus influenzae type b. Infect Immun. 1994;62:2470–2477. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.6.2470-2477.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Koskelo P, Muller-Eberhard U. Interaction of porphyrins with proteins. Semin Hematol. 1977;14:253–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lafontaine E R, Cope L D, Aebi C, Latimer J L, McCracken G H, Jr, Hansen E J. The UspA1 protein and a second type of UspA2 protein mediate adherence of Moraxella catarrhalis to human epithelial cells in vitro. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:1364–1373. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.5.1364-1373.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maciver I, Latimer J L, Liem H H, Muller-Eberhard U, Hrkal Z, Hansen E J. Identification of an outer membrane protein involved in utilization of hemoglobin-haptoglobin complexes by nontypeable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3703–3712. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.9.3703-3712.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marmur J. A procedure for the isolation of deoxyribonucleic acid from microorganisms. J Mol Biol. 1961;3:208–218. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Monod M, Denoya C, Dubnau D. Sequence and properties of pIM13, a macrolide-lincosamide-streptogramin B resistance plasmid from Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1986;167:138–147. doi: 10.1128/jb.167.1.138-147.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morton D J, Stull T L. Distribution of a family of Haemophilus influenzae genes containing CCAA nucleotide repeating units. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1999;174:303–309. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1999.tb13583.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morton D J, Whitby P W, Jin H, Ren Z, Stull T L. Effect of multiple mutations in the hemoglobin- and hemoglobin-haptoglobin-binding proteins, HgpA, HgpB, and HgpC, of Haemophilus influenzae type b. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2729–2739. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2729-2739.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patrick C C, Kimura A, Jackson M A, Hermanstorfer L, Hood A, McCracken G H, Jr, Hansen E J. Antigenic characterization of the oligosaccharide portion of the lipooligosaccharide of nontypable Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1987;55:2902–2911. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.12.2902-2911.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ren Z, Jin H, Morton D J, Stull T L. hgpB, a gene encoding a second Haemophilus influenzae hemoglobin- and hemoglobin-haptoglobin-binding protein. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4733–4741. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.10.4733-4741.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ren Z, Jin H, Whitby P W, Morton D J, Stull T L. Role of CCAA nucleotide repeats in regulation of hemoglobin and hemoglobin-haptoglobin binding protein genes of Haemophilus influenzae. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:5865–5870. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.18.5865-5870.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sambrook J, Fritsch E F, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schenkman J B, Jansson I. Spectral analyses of cytochromes P450. In: Phillips I R, Shephard E A, editors. Cytochrome P450 protocols. Totowa, N.J: Humana Press; 1998. pp. 25–33. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seery V L, Muller-Eberhard U. Binding of porphyrins to rabbit hemopexin and albumin. J Biol Chem. 1973;248:3796–3800. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Setlow J K, Brown D C, Boling M E, Mattingly A, Gordon M P. Repair of deoxyribonucleic acid in Haemophilus influenzae. J Bacteriol. 1968;95:546–558. doi: 10.1128/jb.95.2.546-558.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stull T L. Protein sources of heme for Haemophilus influenzae. Infect Immun. 1987;55:148–153. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.1.148-153.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tatusov R L, Mushegian A R, Bork P, Brown N P, Hayes W S, Borodovsky M, Rudd K E, Koonin E V. Metabolism and evolution of Haemophilus influenzae deduced from a whole-genome comparison with Escherichia coli. Curr Biol. 1996;6:279–291. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(02)00478-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thomas C E, Olsen B, Elkins C. Cloning and characterization of TdhA, a locus encoding a TonB-dependent heme receptor from Haemophilus ducreyi. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4254–4262. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4254-4262.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wandersman C, Stojiljkovic I. Bacterial heme sources: the role of heme, hemoprotein receptors and hemophores. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2000;3:215–220. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(00)00078-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whitby P W, Morton D J, Stull T L. Construction of antibiotic resistance cassettes with multiple paired restriction sites for insertional mutagenesis of Haemophilus influenzae. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1998;158:57–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1998.tb12800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.White D C, Granick S. Hemin biosynthesis in Haemophilus. J Bacteriol. 1963;85:842–850. doi: 10.1128/jb.85.4.842-850.1963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]