Abstract

Over-the-top platforms are increasingly being accepted by the younger generation. This study examines the different modes of watching films that have emerged due to the proliferation of over-the-top platforms, smartphones, and 5G technologies during the pandemic period in China. Using survey data, we examine the perception and behavior of 592 respondents. The top five factors in increasing over-the-top platforms to watch movies include easy access, various genres, no time to visit a cinema, pandemic, and new films. Findings also show that users tend to use smartphones to access over-the-top platforms. Bilibili, Tencent Video, and iQIYI are China's most popular over-the-top platforms among viewers. Increasing cinema ticket prices, pandemics, lack of quality content, and film stories are significant challenges for the cinema industry in the near future. These results suggest that the film industry should maintain the quality of the movies, especially those released on the cinema screen. These findings also designate significant substitution between the over-the-top platform and cinema and recommend that competition authorities widen market definitions. The cinema environment and IMAX/3D appear to have little incentive to degrade over-the-top platforms, despite over-the-top's films contributing to declining box office revenue.

Keywords: Chinese film industry, cinema theatres, over-the-top, paid movies, moviegoers

Introduction

The over-the-top (OTT) media industry is driving the growth of online entertainment. OTT platforms are a result of the development of digital media (Menon, 2022; Mulla, 2022). A paradigm change from the traditional broadcasting media has been brought about by the rise of services that provide media content over the open Internet. OTT platforms have interrupted consumers’ film-watching behavior via technology, innovation, and personal adaptations (Sahu et al., 2021). According to Gonçalves et al. (2014), “over-the-top is video distribution using the Internet Protocol over a public network, i.e., the Internet with unmanaged Quality of Service (QoS)” (p.7). OTT platform has significantly replaced linear television and cable/satellite in the recent decade (Nogueira et al., 2018; Yousaf et al., 2021).

Since COVID-19 emerged, cinema theatre has struggled to cope with the constant disruption caused by increasing consumer video demands and shifting viewing habits to the OTT (Yaqoub et al., 2022a). People have enjoyed watching movies in the cinema for over a 100 years. Film production, distribution, and viewers-watching habits have all been impacted by COVID. New media, technologies, and media culture expansion are poised to shape and transform the cinema industry's future at the beginning of the 21st century (Safiranita et al., 2021; Tefertiller, 2020). Over the past couple of years, COVID-19 has accelerated this digital change in the film and entertainment industry, and the OTT platforms have taken a prominent place in viewers’ lives. Stay-at-home has fueled the wave of home entertainment. OTT platforms are gradually disrupting the cinema, filmmaking, and distribution industries worldwide. People can now binge and watch content online that matches their interests anytime on their gadgets. In 2020, the number of subscribers of OTT services grew by more than 50% in the United States of America (Rizzo and FitzGerald, 2020), also seeing an increment among the Chinese audience (Yaqoub et al., 2022b). After achieving massive success in TV shows, films, and web series, OTT platforms started to generate their content instead of relying on others’ movies and shows. OTT platform Netflix, which started streaming in 2007, has become a significant filmmaking source and has now made or worked on more than 500 shows (Sherman, 2021). Home entertainment is expanding, accounting for 79% of the almost $100 billion worldwide video entertainment industry in 2021. According to MPA (2022) report, the cinematic market represented just 21% of the total. It shows that digital entertainment exceeded threefold the box office worldwide.

The years 2020–2021 were watershed moments for the OTT platforms landscape worldwide. Consumers sought amusement at home; when movie theatres shut down, live entertainment events were mainly canceled, and restricted travel and eating choices. However, when people gain confidence in their ability to reengage with the pre-pandemic entertainment options under the new normal, their dependency and habits on OTT platforms are continued. OTT platforms are used by about 2 billion people worldwide (Cramer-Flood, 2022), with a user penetration rate of around 40.9% (Statista Research Department, 2022). The digital technologies of the internet and smartphone are reshaping film viewing habits in China. The Chinese OTT streaming platforms have been around since YouTube (2005). China is a potential cinematic industry standing at a transition state in OTT platforms, driving the Chinese film industry's modern transformation. Concomitantly, these platforms are used by the domestic audience using smartphones, which have improved dramatically due to the cheaper costs and data bundles (Zhao, 2016). Likewise, the general public has access to their favorite content on several OTT platforms and spends more than two hours daily (Dasgupta and Grover, 2019). Digital platforms, where there has been a significant change in the consumer touch-point, will provide much reliability in the future. Chinese production houses have also moved to these OTT platforms to release their films and web series.

The new generations, Generation Z (Gen Z), and Millennials, also known as Gen Y, shifted from conventional broadcasts and cinema toward intelligent devices (Dasgupta and Grover, 2019; Marne, 2021; Valecha, 2017). Millennials were born between the years 1981 and 1996 (26–41 years in 2022). Generation Z was born between the years 1997 and 2012 (aged between 10 and –25 years in 2022). Digital video services are quickly expanding and gaining traction worldwide since their emergence. Chinese millennials and Gen Z are drawn to OTT platforms because of the availability of international content and video on demand (VOD) (Maoyan Entertainment, 2021). Consumers can now watch films on their digital devices, such as smartphones, laptops, and tablets, whenever and wherever they want due to the growth of OTT services. Cheaper bandwidth, Internet of things (IoT), 4K, artificial intelligence (AI), and uninterruptible 5G connections have significantly aided OTT platforms’ cutting-edge development (Xia, 2022). Globally COVID-19 outbreak seems to be an accelerator for the media and entertainment industry shifting from cinema to OTT platforms. Even though coronavirus had been well contained in China after the first wave, the cinema industry still seemed in an age of risk due to continuous emerging pandemic threats and lockdowns (Morrison et al., 2022). The popularity of OTT platforms is increasing, especially among the active and significant portion of cinemagoers, mainly university and college students.

China has seen a substantial increase in OTT users since the breakout of COVID-19. The pandemic significantly influenced the film and entertainment industry in February 2020 and has emerged as a threat to the cinema theatre business. Due to the nationwide lockdown, people were confined to their houses and had few other possibilities for amusement. There were no movie theatres open. As a result, people started to watch films, TV series, shows, and web series on OTT platforms, which helped keep viewers glued and entertained (Chatterjee and Pal, 2020; Yang, 2022).

The primary purpose of our study is to determine the factors, development, and challenges that play a crucial role in shifting the audience from cinema theatre to OTT platforms after the first wave of coronavirus in China. Explore how digital technologies and developing factors transform film and entertainment industry consumer behavior. Analyze why the audience prefers to watch the movie on OTT platforms rather than other media. To identify the factors which are the leading causes of cinema downfall in the current ecosystem of OTT platforms. The central statement of this research problem is how people watch movies on OTT platforms and how much they like to visit the cinema in China. In this article, we provide insight into whether OTT platforms are a meaningful substitute for cinema theatres by empirically studying the perception and behavior of film lovers.

Literature review

Over the past few years, the phenomenon of audience research in film, drama, and television studies has gotten more attention (Mulla, 2022; Nayak and Biswal, 2021; Su, 2021). The authors conducted a systematic review of the literature to understand better the study topic and the larger body of existing knowledge (Yaqoub et al., 2022b). According to Mulla (2022), the ecosystem for OTT platforms is still in its early stages. The fast expansion, digitalization, and intelligence have made it increasingly important for marketers, producers, filmmakers, and distributors to understand who regularly visits the cinema or watches video content on OTT platforms. In addition, Table 1 summarizes the key factors that drive the audience to consume OTT content.

Table 1.

Factors influencing the choice of over-the-top (OTT) content.

| Factors influencing the choice of OTT content | Citing literature | |

|---|---|---|

| Push factors | Risk of infection | Kim (2021) |

| Government restrictions | Abulibdeh and Mansour (2021) | |

| Cost of cinema tickets | Kim (2021), Donar and Aydan (2022) | |

| Pull factors | Cost/subscription charges | Koul et al. (2021), Bhullar and Chaudhary (2020), Gupta and Singharia (2021) |

| Wider content | Bhattacharyya et al. (2021), Koul et al. (2021), Kim et al. (2021) | |

| Ease of access/flexibility | Mulla (2022), Menon (2022), Nagaraj et al. (2021), Massad (2018) | |

| Local language content | Nagaraj et al. (2021), Koul et al. (2021) | |

| Access to global content | Nagaraj et al. (2021), Kwon et al. (2021) | |

| Interactive applications | Shin and Park (2021), Nagaraj et al. (2021) |

COVID-19 transformed how millennial and centennial audiences consume entertainment content, resulting in their adoption of OTT platforms as an alternative (Camilleri and Falzon, 2021; Koul et al., 2021). The change was a result of various push and pull factors. Fear of infection (Kim, 2021), restrictions on mobility imposed by local government authorities (Abulibdeh and Mansour, 2022), and increasing cinema ticket prices (Donar and Aydan, 2022) are all pushing factors. These factors forced people to stay at home and brought a change in entertainment content consumption. On the other hand, pull factors like reasonable pricing, the content of choice, and accessibility helped the viewers to continue consuming the OTT content (Mulla, 2022). Moreover, the OTT service is perceived to be more attractive than traditional media because of its accessibility across time and space, allowing freedom of choice for users to watch the desired content (Shin and Park, 2021).

Among all the pull factors influencing the choice of OTT over other entertainment media are affordable prices (Bhullar and Chaudhary, 2020), availability of a wide range of content (Bhattacharyya et al., 2022), ease of access to content through any device or at any time (Mulla, 2022), availability of both local and global content (Nagaraj et al., 2021) and interactive nature of platforms (Shin and Park, 2021) are frequently cited factors in the literature.

After reading the previous literature, the writers found research gaps. The literature finding reveals that cinemagoing, OTT use, and audience satisfaction in the Chinese environment, including Gen Y and Z, should be explored. The gap in these substantial research efforts and studies was that very few had considered the Chinese audience for OTT platforms and cinema while defining the study scope. Second, altered conditions and technology have made comparative analysis popular. Literature review studies don’t compare OTT and cinema theatre. This study weighs the critical aspects according to their relevance as regarded by the audience when utilizing OTT platforms or cinemagoing, discovering links between the different factors and exhibiting comparative insights from today's Chinese youth viewer's perspective. Additionally, it could provide a suggestion for using OTT platforms. Since the pandemic outbreak, we believe that examining OTT platform users and moviegoers will give a better and deeper understanding of the Chinese box office in general and OTT platforms in particular.

Theoretical background

The U&G theory framework (Blumler and Katz, 1974) has been used in earlier literature to understand the social and psychological motivations behind the use of traditional media (Babrow, 1987; Theocharis et al., 2021; Wang et al., 2021) as well as other media choices like OTT platforms (Hellweg, 2021; Latora, 2020; Tolba and Zoghaib, 2022) and other user-generated media (Bolton et al., 2013). Due to these assertions, the U&G theory has been extensively employed in media-related research. It suggests varied intentions to continue using any medium or media depending on consumers’ motivation, activity, and selection criteria (Bano et al., 2019; Katz et al., 1973; Quan-Haase and Young, 2010). Menon (2022) claims that eight key U&G factors—convenient navigability, binge-watching, entertainment, relaxation, social interaction, companionship, voyeurism, and information seeking—affect the decision to subscribe to and continue using any medium. Five of the eight motives are comparable to earlier research (entertaining, relaxing, socializing, and informing). These include entertainment and affection U&G, which should also be the case of OTT platform preference since content provides users satisfaction and exposes them to knowledge debated in social groups.

Binge viewing results from this feeling of fulfillment and is particularly common among younger OTT platform users (Lim, 2021). Young consumers may continue using OTT platforms in light of their psychological makeup and viewing preferences, but the Niche hypothesis suggests that conventional forms of entertainment may survive with OTT (Chen, 2019; Chen, 2019). According to 2016 Taiwanese research, although OTT and conventional TV have similarities in enjoyment and ease of use for the niche overlap, OTT outperforms them on every other metric for the width of the niche. In developing nations, there is a significant likelihood that both conventional and OTT platforms will coexist (Kim, 2019).

Methodology

Both qualitative and quantitative research methods were utilized to investigate the challenges and prospects of existing cinema and OTT platforms in the new normal to assess how young Chinese people use OTT platforms and their cinemagoing experiences (Berman, 2017; Chen, 2019; Creswell and Creswell, 2017; Dishaw and Strong, 1999; El-Mashaleh et al., 2006; Snelson, 2016). In the past, several researchers have used this study design and stated that it is effective in evaluating the audience of OTT platforms and cinemagoers (Austin, 1986; Kim et al., 2016; Lee and Cho, 2021; Patnaik et al., 2021; Rao, 2007; Seo, 2020; Shin and Park, 2021; Sowbarnika and Jayanthi, 2021).

The data has been collected online through an electronic questionnaire designed using Questionnaire Star (问卷星) (https://www.wjx.cn/) (Song et al., 2019; Yaqoub et al., 2022b). The study's participants have various education, gender, economic, social, and cultural backgrounds from university and college students (Gen Y and Z) of Mainland China. This population was selected because they are relatively the most considerable moviegoers or users of OTT services and are well educated (Bhattacharyya et al., 2021; Maoyan Entertainment, 2021; Marne, 2021; Shah et al., 2020; Thomala, 2022a). Since there was no sampling frame available for the present cross-sectional study, respondents were chosen using a non-probability framework (purposive and snowball sampling techniques). These techniques allowed the researchers to access the target respondents, resulting in more accurate and consistent findings (Denzin and Lincoln, 2011; Frost, 2021; Kwateng et al., 2021). The data were collected in both Chinese and English languages together. First, we wrote the questionnaire in English and later transcribed it into the Chinese language, thematically and conceptually examined by bilingual experts. After consultations, the questions were meticulously crafted.

Over 690 responses were obtained using WeChat (a well-known Chinese multi-purpose social media app) and retrieved through the internet, and only 592 valid filled questionnaires were used for analysis. In Table 2, we reported descriptive statistics of the sample.

Table 2.

Description of respondents.

| Variable | Sample data |

|---|---|

| Education | PhD: 32 (5.4%) Master: 198 (33.4%) Undergraduate: 274 (46.3%) Secondary school or below: 88 (14.9%) |

| Monthly consumption during school | ≤1000 RMBa: 82 (13.9%) 1100–1500 RMB: 235 (39.7%) 1600–2000RMB: 147 (24.8%) ≥ 2100 RMB: 128 (21.6%) |

| Age | ≤ 20 years: 98 (16.6%) 21–25 years: 352 (59.5%) 26–30 years: 73 (12.3%) 31–35 years: 41 (6.9%) ≥ 36 years: 28 (4.7%) |

| Gender | Male: 287 (48.5%) Female: 305 (51.5%) |

RMB (Ren Min Bi) is the official currency of the People’s Republic of China.

Notes: N = 592.

Source: Authors’ compilation.

The table also illustrates that the participants had diverse education, age, gender, and monthly consumption (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2022). The questionnaire of the present survey consists of close-ended and open-ended question items. We have used SPSS 25 statistical software and SPSSAU for the data analysis and visualization of structured questionnaires.

Most respondents are undergraduate/master-level students (46.3% and 33.4%). During school, most of the responders’ monthly consumption is between 1000 and 2000RMB (150–300USD) (64.5%), and the majority, 59.5%, are between the ages of 20 and 25 years. Overall, our sample consisted of 51.5% females (Maoyan Entertainment, 2021).

This survey research took 23 days, from 12 April to 4 May 2021, for data collection. The reasons for selecting this time frame were convenient to access and distribute the questionnaire among the university and college students. Second, the out-of-province quota system allows students from any of China's provinces to enroll in any university/college, regardless of where the institution is located. We got together with the faculty members and requested their assistance in sending our electronic questionnaire to the students in the various parts of China where they teach. We also sent a personal appeal to students located in various regions, asking them to fill out the survey and share it with their friends/classmates. Third, this research population may cover about three-fourths as Maoyan Entertainment (2021) reported about 80% of moviegoers are under the age of 34 years.

Findings

OTT platforms

Because of the diversity of material, OTT platforms have become very popular among Chinese viewers. To support this assertion, we objectively analyzed user behavior. The results indicate that viewers significantly prefer to expose to OTT platforms. Findings reveal most respondents, 64.7% (61.3% male and 67.9% female), very frequently/frequently, 22.5% (23% male and 22% female) somewhat, are using the OTT platforms. In comparison, 12.8% (15.7% male and 10.2% female) admitted that they seldom or did not use any OTT platforms recently (Figure 1). Regarding gender, there were no significant group differences (sex: χ² = 6.753, df = 4, p = 0.1).

Figure 1.

Over-the-top (OTT) watching habits.

Notes: N = 592, χ² = 6.753, df = 4, p = 0.1*.

Source: Authors’ compilation.

The previous research examined users’ options to switch between a variety of OTT services and devices (Hayes, 2020; Hess et al., 2011; Kelly, 2022; Stoll, 2021). Since one service cannot provide all material, OTT customers choose to sign up for many platforms (Ovum Market Study, 2021). During the present research, it was found that the respondents aged <31 years frequently jump between different OTT platforms (60%). The participants aged between 31 and 35 years somewhat (39%) and >35 years old did not jump among the OTT platforms (25%). Overall, results show that only 14.7% of respondents do not jump from one OTT platform to another for desired films or do not use OTT platforms. The statistics also show that in 21–25 years, users more frequently move from one platform to another for desired content (Figure 2). In terms of age, there were no significant group differences (age: χ² = 12.046, df = 8, p = 0.1). These statistical findings show that Gen Z uses more than one OTT platform and frequently jumps to find and watch their desired content, in line with a previous study (Media Smart, 2021). These findings also confirm that over a third of Tencent Video's active users were under the age of 24 years, and more than 75% were less than the age of 40 years (Thomala, 2022c).

Figure 2.

Jumping among platforms.

Notes: N = 592, χ² = 12.046, df = 8, p = 0.1*.

Source: Authors’ compilation.

The amount of time the typical individual spends watching digital media is rising. Due to the development of more recent and advanced technology, desktop computers are no longer the only way for people to access the World Wide Web. Ultimately, there is a growing divide between mobile and desktop use (Bouchrika, 2022). Users regularly view online movies on laptops and desktop computers (Bentley et al., 2019). With the internet and technological revolution, cutting-edge gadgets have become essential components of people's daily routines. A growing reliance on privately held infrastructure and platforms has become the new normal.

Regarding the use of devices for accessing the OTT platforms, the results align with previous studies (Chatterjee and Gupta, 2017; Cheng and Mitomo, 2017; Williams et al., 2020). Most of the respondents from all groups of average monthly consumption used a smartphone (70%) to access the OTT platforms. The users of Tablet majority belong to the consumers whose average monthly consumption is more than 2000RMB, while desktop computer users are in the minority, with only approx.—11% of the sample. Above 50% (1100–2000RMB) of users stated they use laptops to access OTT platforms. Big-screen LCD TV users differ between 20% and 37% (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Devices used during access to the over-the-top (OTT) platforms.

Notes: N = 592.

Source: Authors’ compilation.

A wide range of genres and the rapid development of streaming entertainment have forced traditional rivals to compete in new ways. According to Paolo Pescatore, a tech analyst at P.P. Foresight, the one with his content will be ahead in this competition (Sherman, 2021). As seen (Table 3), we surveyed the primary factors and reasons for increasing OTT platforms among movie lovers. It indicates that gender-based group differences do not significantly impact these nine items, including ease of access, work pressure, health threats, 5G, pandemic, innovation, old films, new movies, and documentaries (p > 0.05).

Table 3.

Factors of increasing diffusion of over-the-top (OTT) platforms (N = 592).

| Itemsa | Gender | Total | χ² | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||||

| Easy to access | 75.6 | 76.1 | 75.8 | ① | .897 | .486 |

| No time to visit a cinema | 58.2 | 65.6 | 62.0 | ③ | 3.423 | .039* |

| Work pressure | 20.6 | 19.3 | 19.9 | .136 | .395 | |

| Health threats | 5.9 | 4.6 | 5.2 | .530 | .293 | |

| 5G | 27.5 | 30.5 | 29.1 | .631 | .241 | |

| Pandemic | 51.2 | 54.1 | 52.7 | ④ | .492 | .268 |

| Various genres | 60.6 | 71.8 | 66.4 | ② | 8.276 | .003** |

| Expensive cinema tickets | 28.2 | 38.0 | 33.3 | ⑨ | 6.409 | .007** |

| Innovation | 26.8 | 24.6 | 25.7 | .388 | .298 | |

| Web series | 40.1 | 55.1 | 47.8 | ⑧ | 13.355 | .000** |

| Old films | 49.8 | 52.8 | 51.4 | ⑥ | .519 | .262 |

| New movies | 54.0 | 49.5 | 51.7 | ⑤ | 1.198 | .156 |

| TV serials | 35.2 | 62.3 | 49.2 | ⑦ | 43.460 | .000** |

| Documentaries | 35.2 | 31.1 | 33.1 | ⑩ | 1.092 | .169 |

| Cartoon | 38.0 | 23.0 | 30.2 | 15.831 | .000** | |

Notes: aData are based on (multiple responses), evaluated in %.

Source: Authors’ compilation.

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

In addition, six items; no time to visit a cinema (χ² = 4.516, p = 0.039 < 0.05), various genres (χ² = 4.516, p = 0.003 < 0.01), expensive cinema tickets (χ² = 4.516, p = 0.007 < 0.01), web series (χ² = 4.516, p = 0.000 < 0.01), TV serials (χ² = 4.516, p = 0.000 < 0.01), and cartoon (χ² = 4.516, p = 0.000 < 0.01) have noticed significant differences regarding gender. These findings align with the previous research (Dasgupta and Grover, 2019).

Easy to access, various genres, no time to visit a cinema, pandemic, new movies, old films, TV serials, web series, expensive cinema tickets, and documentaries are simultaneously the top 10 factors that are significantly impacting the penetration of OTT platforms (GT staff reporters, 2022). Over 10% of respondents said that there are different reasons (anytime, anywhere, fragmented time, a hardly good movie in the cinema, favorite idols, convenience, and laziness) for the popularity of OTT platforms. According to previous studies, the present study finding also shows the results (Parikh, 2020; Patnaik et al., 2021; Sowbarnika and Jayanthi, 2021).

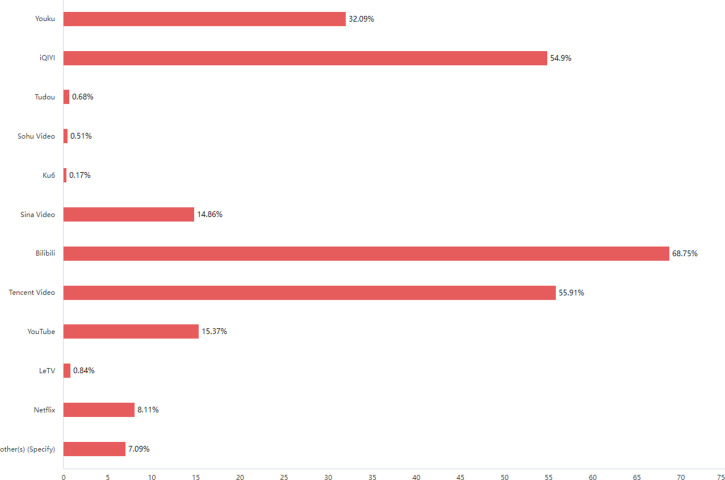

In the multiple-choice question, this research found that most OTT platform users preferred Bilibili (68.75%); users of Bilibili are 86% under the age of 35 (Shreya, 2022). Tencent Video (55.91%), followed by iQIYI (54.9%), Youku (32.09%), YouTube (15.37%), Sina Video (14.86%), and Netflix (8.11%) in the decreasing order of their preference (Wang and Lobato, 2019). About 7% of respondents use different platforms for video content like Mango TV, Amazon Prime, Renrent Video, Web version, Watermelon Video, and TV Encyclopedia. In addition, 1.76% use LeTV 0.84%, Tudou 0.68%, Sohu Video 0.51%, and only 0.17% watch videos on Ku6 (Figure 4). Over 50% of users simultaneously utilize three OTT services (Sadana and Sharma, 2021).

Figure 4.

Users of over-the-top (OTT) platforms.

Notes: N = 592.

Source: Authors’ compilation.

Survey also reveals that 27% (male 32.75% and female 21.64%) watched more than three, 16.2% watched two, and 14.5% watched (decreasing order) only one online paid film on the OTT platforms. 33.6% stated that they had not viewed any movie since last month. On average, two-thirds of the respondents said they watched at least one paid movie during the previous month. There was a significant gap in the number of films seen by males and females compared to the cohort as a whole sample (χ² = 12.150, df = 4, p = 0.016 < 0.05) (Table 4).

Table 4.

VIP (paid) film on over-the-top (OTT) platforms (N = 592).

| 1 | 2 | 3 | More than 3 | None | Subtotal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 43 (14.98%) | 47 (16.38%) | 21 (7.32%) | 94 (32.75%) | 82 (28.57%) | 287 |

| Female | 43 (14.10%) | 49 (16.07%) | 30 (9.84%) | 66 (21.64%) | 117 (38.36%) | 305 |

| 86 (14.5%) | 96 (16.2%) | 51 (8.6%) | 160 (27.0%) | 199 (33.6%) |

Notes: χ² = 12.150, df = 4, p = 0.016 < 0.05.

Source: Authors’ compilation.

Cinema

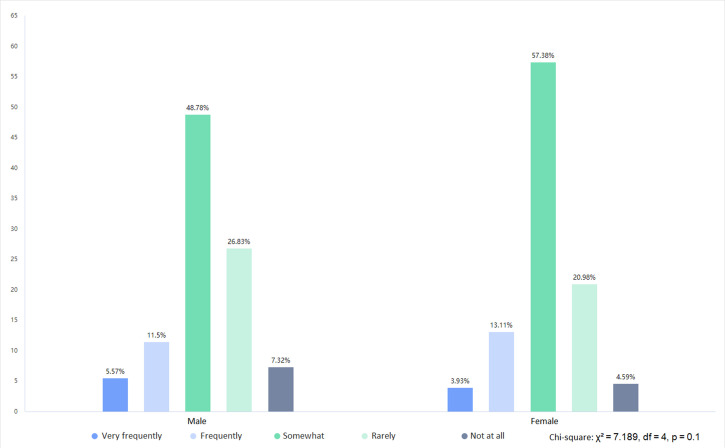

Chinese moviegoers were hesitant to attend theatres; thus, it had not yet fully returned to its pre-pandemic level (Thomala, 2022b). Our study reveals that most respondents, 53.21% (48.78% males and 57.38% females), “somewhat” visit the cinema theatre. Overall, about 4.73% (5.57% males and 3.93% females) of respondents very frequently and 12.33% (11.5% males and 13.11% females) often watch movies in the cinema.

Among respondents, 23.82% rarely, and only 5.91%, never visited the cinema for films (Figure 5). In terms of gender, there was no significant group split (χ² = 7.189, df = 4, p = 0.1).

Figure 5.

Frequency of visiting the cinema to watch a movie.

Notes: N = 592.

Source: Authors’ compilation.

Table 5 is based on the data to find how much respondents enjoy a cinema environment in China. It was discovered that the respondents relished the moviegoing experience—22.3% “very much” and 45.27% “much.” It was also found that only 3.72% of respondents did not feel satisfied with the environment. Overall, most moviegoers enjoyed a lot of cinema atmosphere (mean = 2.22; SD = .964).

Table 5.

Cinema environment (N = 592).

| Mean | SD | Max. | Min. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cinema environment | 2.22 | .964 | 5 | 1 |

Source: Authors’ compilation.

According to Figure 6, about 77.3% (50% very much and 29% much) of movie lovers consider that they will continue watching movies in the cinema even though they are not frequent cinemagoers. In comparison, only 1.5% said they might not watch movies in the cinema in the next 5 years. Females are more hopeful about watching movies in cinema than males (χ² = 10.156, df = 4, p = 0.038).

Figure 6.

Cinema's future.

Notes: N = 592, χ² = 10.156, df = 4, p = 0.038*.

Source: Authors’ compilation.

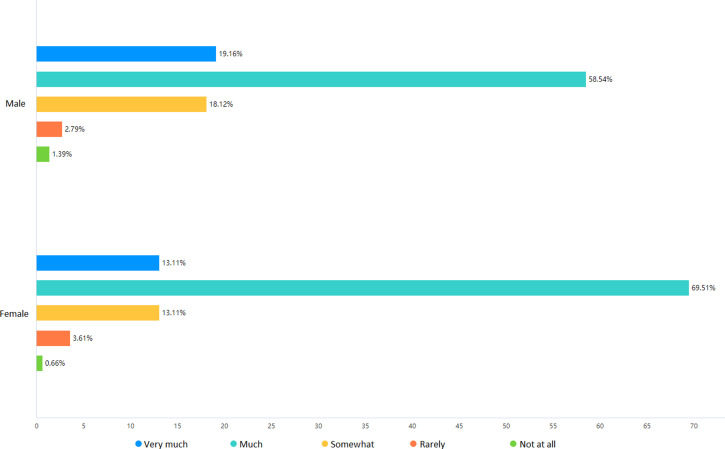

In response to the satisfaction toward cinema facilities, 16% (19.16% male and 13.11% female) said very much, 64% (58.54% male and 69.51% female) much, 15% (18.12% male and 13.11% female) somewhat, 3.21% (2.79% male and 3.61% female) hardly satisfied, while only 1% (1.39% male and 0.66% female) of the audience said they are not satisfied with cinema facilities. It reveals that moviegoers at Chinese cinemas are well satisfied (mean: 2.09, SD: .727). No discernible correlation was seen between the male and female (r = .009, p = 0.822) (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Cinema facilities.

Notes: N = 592.

Source: Authors’ compilation.

As seen ( Table 6), we also surveyed the main factors and reasons for cinemagoing. Findings revealed no significant effects of gender on educational purpose, catharsis, enjoyment, peer pressure, holidays, and self, a total of six items (p > 0.05), meaning that gender differences do not significantly impact these six items. In addition, three items; Interest (χ² = 4.482, p = 0.021 < 0.05), IMDB rating (χ² = 3.439, p = 0.040 < 0.05), and Boyfriend/girlfriend (χ² = 17.826, p = 0.000 < 0.01) have obvious significant differences regarding gender. These findings align with the previous studies (Husna and Dewi, 2021; Puthiyakath and Goswami, 2021; Testoni et al., 2021).

Table 6.

Factors of cinemagoing (N = 592).

| Itemsa | Gender | Total | χ² | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |||||

| Educational purpose | 20.2 | 18.4 | 19.3 | .325 | .321 | |

| Interest | 69.0 | 76.7 | 73.0 | ② | 4.482 | .021* |

| Catharsis | 27.2 | 22.0 | 24.5 | 2.171 | .084 | |

| Enjoyment | 81.5 | 82.0 | 81.8 | ① | .019 | .488 |

| IMDB rating | 20.6 | 14.8 | 17.6 | 3.439 | .040* | |

| Peer pressure | 13.6 | 10.8 | 12.2 | 1.061 | .183 | |

| Holidays | 64.5 | 70.2 | 67.4 | ③ | 2.189 | .082 |

| Self | 53.3 | 60.0 | 56.8 | ④ | 2.696 | .059 |

| Boyfriend/girlfriend | 46.7 | 29.8 | 38.0 | ⑤ | 17.826 | .000* |

Notes: aData are based on (multiple responses), evaluated in %. Bold values signify the difference regarding gender (male and female).

Source: Authors’ compilation.

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

The percentage comparison difference shows that enjoyment, Interest, Holidays, Self, and Boyfriend/girlfriend are the top five factors that significantly impact cinemagoing (Parikh, 2020; Patnaik et al., 2021; Sowbarnika and Jayanthi, 2021). Some other reasons also mentioned by the responders include liking a particular movie theme, or story, relieving stress, plot, subject, new film, bored to pass the time, and social activities.

Today, producers and directors’ endeavor to include content that will pique the attention of most viewers in the film story, as most moviegoers like drama, humor, action, and suspense. Chi-square test was used to compare the preference of males and females in movie genres. In comedy and suspense, there was no distinction between males and females. In addition, the results indicated that there is significant difference between male and female on the five genres: drama (χ² = 14.446, p = 0.000 < 0.01), action (χ² = 27.063, p = 0.000 < 0.01), thriller (χ² = 6.361, p = 0.008 < 0.01), adventure (χ² = 17.126, p = 0.000 < 0.05), and horror (χ² = 7.114, p = 0.005 < 0.01).

Most film stories based on drama, comedy, and action are very successful at the box office. Further, the data reveals that most moviegoers, 71% (70% male and 72% female), 63% (55% male and 70% female), and 63% (73% male and 52% female), respectively, prefer to watch comedy, drama, and action-based story content. Moreover, the moviegoers, 288 (42.35%), 246 (36.18%), 66 (24.41%), and 124 (18.24%) like to watch correspondently adventure, suspense, thriller, and horror film in the cinema. Among the respondents, 8% (7%male and 9%female) said they prefer to watch cartoons, literature, and art, thought-provoking content, sci-fi movie (among the other contents, the majority said science fiction movies), documentary films, and romantic genres (Navarro, 2021; Thomala, 2021; Ying, 2022) (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Genres of movies.

Notes: N = 592.

Source: Authors’ compilation.

*p < 0.05 **p < 0.01.

Usually, the release of new domestic and imported films is considered the driving force to pull moviegoers to the cinema. Pearson's r data analysis reveals a moderate positive correlation, r = .589, between domestic new releases (M = 2.92, SD = .865) and imported new releases (M = 2.92, SD = .837). Overall, in our study findings, more than half of the respondents stated that new domestic or foreign blockbuster movies somewhat drive them to watch on the cinema screen (Table 7).

Table 7.

Determine the correlations between domestic and imported new movie releases in China.

| Mean ± SD | Domestic new release | Imported new release | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Domestic new release | 2.92 + .865 | Pearson correlation | 1 | .589** |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | .000 | |||

| N | 592 | 592 | ||

| Imported new release | 2.92 + .837 | Pearson correlation | .589** | 1 |

| Sig. (two-tailed) | .000 | |||

| N | 592 | 592 |

Source: Authors’ compilation.

**p < 0.01.

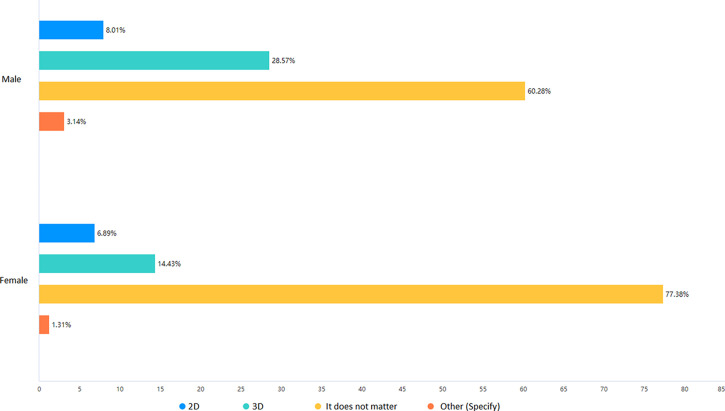

In response to the item about the preference for the cinema screen, 69% (male 60% and female 77%) of viewers stated that the cinema screen does not matter, 21% (male 27% and female 14%) respondents prefer to watch the movie on the 3D, 7% respondents said they watch the film on 2D. In comparison, about 2% of moviegoers said they prefer to watch on other like, IMAX giant screens (Figure 9). On the aspect of movie screen preference, there was a significant difference between male and female responders (χ² = 22.652, df = 3, p = 0.00 < 0.01).

Figure 9.

Cinema screen.

Notes: N = 592, χ² = 22.652, df = 3, p = 0.00*.

Source: Authors’ compilation.

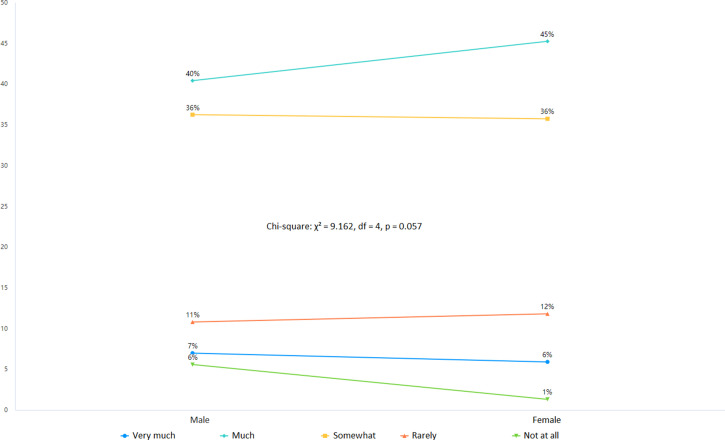

China has overtaken the crown of worldwide box office revenue since 2020 (Brzeski, 2022; Shah et al., 2020). Both male and female movie lovers are much satisfied with the cinematic power of the Chinese film industry (40% male and 45% female). More than one-third of the participants showed somewhat satisfaction, while only 3% of respondents were not satisfied with the cinematic power of the Chinese film industry (Figure 10). No significant difference was found between gender perception toward cinematic power (χ² = 9.162, df = 4, p = 0.057 > 0.05).

Figure 10.

Satisfaction toward cinematic power of the Chinese film industry.

Notes: N = 592.

Source: Authors’ compilation.

Researchers usually use close-ended question items during the survey because it is more convenient and easier to get in-depth feedback. We also put an open-ended question item (optional) to check and make more significant results. Using the “words cloud,” findings reveal that increasing cinema ticket prices, pandemics, and quality content are the three biggest challenges for the cinema industry in the near future.

Regarding revenue, China and the United States are still the world's two largest movie markets. Following a meteoric rise in 2020, Global OTT video revenue increased by 22.8% in 2021 to reach US$79.1 billion (PWC, 2022). China's rigorous “COVID-zero” attitude to the pandemic hampered moviegoing when more than 70 Chinese cities, including Shenzhen and Chengdu, imposed partial or complete lockdowns in reaction to omicron flare-ups. Large-scale new releases have eschewed theatrical release schedules during the shutdown to push material directly to OTT platforms because theaters were shut down. Artisan Gateway currently forecasts China's box office to finish 2022 with approximately $5.2 billion (RMB 35 billion) in total revenue. Many analysts expect North American ticket revenue to top $7.5 billion this year.

Compared to China's box office, we discovered that OTT had grown 48% since the COVID-19 outbreak, while Chinese box office revenue has fallen 21%. Chinese moviegoers also decreased (−25%) despite a 17.5% rise in the number of screens (Liu, 2022; Liu and Lu, 2020; MPA, 2022; PwC China, 2020, 2022; Xinhua News Agency, 2019). The findings indicate positive causal linkages exist with OTT, but hostile causal relations exist with China's box office revenue. The pandemic has had a considerable influence on moviegoers, compelling many to forego going to the theater in favor of staying at home and watching their favorite content on OTT platforms. Overall, the revenue from Chinese OTT platforms and the box office in China had an antagonistic relationship (Table 8).

Table 8.

Comparison between the revenue of over-the-top (OTT) platforms and box office in China.

| Year | OTT Platform | Cinema | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Revenue (billion) | Online video users (million)a | Per capita viewing time | Revenue (billion) | Attendances (billion) | Cinema screen | |

| 2019 | US$7.7** | 850 (Mar. 2020) | +49 minutes (+18%)

|

US$9.2** | 1.727 | 69,787 |

| 2021 | US$11.4** (+48%)

|

975 (14.70%)

|

US$7.3B* (−21%)

|

1.3 (−25%)

|

82,000 (+17.5%)

|

|

Active users of smart devices annual growth of 33.6% in 2022 (China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC), 2022).

China has the fastest rate of OTT video growth globally (12.2%) (PWC Hong Kong, 2020).

[Global level position: *first, **second are compared to North America].

Increase;

Increase;  Decrease.

Decrease.

To

watch VOD increased 49 min. after the outbreak.

To

watch VOD increased 49 min. after the outbreak.

Source: Authors’ compilation.

Discussion

Research implications

The study provides insights into consumers’ choices about viewing cinema after the COVID-19 pandemic under the new normal. COVID-19 pandemic affected consumer behavior toward entertainment content (Kim, 2021). This effect not only changed the medium of consuming content but also influenced the quality of the content (Nagaraj et al., 2021). The study's results highlight the reduction in box-office revenue in China after the pandemic, resulting in increased subscribers for OTT services. Though the box office revenue decrease is subjected to many factors, the impact of the seismic shift of consumers to OTT services cannot be neglected. These findings coincide with a Korean study by Kim (2021), which found a strong negative impact of the pandemic on movie demand. Moviegoers preferred to stay at home watching OTT content to practice social distancing.

The study's findings observed the shift in consumer behavior toward cinema. The gender differences in terms of exposure and choice of OTT platforms seem blurred from the study's findings. Nagaraj et al. (2021) have similar results among Indian consumers where gender has no significant influence on the choice of platform and OTT subscription. Gender influences can still be seen in the number of movies watched and genres preferred by male and female consumers. However, there is a clear shift in the younger generation toward consuming OTT content. Literature also confirms that millennials are keener to adopt OTT services (Mulla, 2022), and the probability of subscription to OTT services reduces with the age of customers (Nagaraj et al., 2021). This shift can also be attributed to the change in technology and devices. As smartphones and privately held infrastructure increased, users could exercise freedom of choosing the content per their individual preferences.

The price of OTT services in terms of subscription charges compared to movie tickets and the freedom to choose content are the most critical factors for choosing OTT services (Koul et al., 2021; Mulla, 2022; Nagaraj et al., 2021). Though the pandemic impacted moviegoing habits, the diffusion of OTT services will continue due to price, quality of content, convenience and freedom of choice.

Managerial implications

The study provides an understanding of Chinese consumers’ moviegoing choices after the pandemic. The trends in the behavior of consumers are alarming for cinema at the global level. The diffusion of handheld devices, availability of faster internet and easy access to global content fueled the growth of OTT subscribers. During the pandemic, consumers found it safe and convenient to subscribe to OTT content. However, this shift seems to continue even after the pandemic, due to improved content on OTT platforms in terms of quality and quantity. The switching between platforms will be influenced by subscription charges and the type of content. As per the study's findings, gender differences between the choice of media and content are insignificant, and the segmentation strategies with gender as a base need to be revisited.

Conclusion

Quarantine and self-loneliness have influenced many aspects of people's lives and leisure activities. This study is a special effort to examine how movie lovers perceived the cinema and OTT platforms when COVID was well under control after the first wave in China. The COVID-19 pandemic is still working as a catalyst that accelerated the adaptation process to the OTT platforms. Over the past decade, the growth of OTT platforms has resulted in unique content consumption patterns in China. The present study found that two-thirds frequently use OTT platforms for video content. As can be observed, the top five primary causes of the growing number of OTT platforms to view movies regularly are the convenience of access, variety of genres, lack of time to attend a theatre, epidemic, and new films. Bilibili, followed by Tencent Video and iQIYI, is China's most popular OTT platform. Two-thirds of respondents viewed at least one paid movie on OTT platforms, compared to every sixth person who usually went to the film. Even though majority is not frequent cinemagoers, but most enjoy the cinema environment and will continue seeing the movie on the screen. Enjoyment, Interest, Holidays, Self, and Boyfriend/girlfriend are among the top five factors that significantly impact cinemagoing habits. Most movie lovers watch comedy, drama, and action-based film stories. New domestic and foreign films have a significant influence on moviegoers. Most moviegoers are numb about the type of cinema screens when they go to the movies; they do not bother about what kind of cinema screen. Movie lovers are also satisfied with the cinematic power of the Chinese film industry after the first wave of coronavirus. Our study also reveals that cinema ticket prices, pandemics, and quality content are the biggest challenges for the cinema industry in the current scenario. Most Chinese cinephiles agree that the Chinese film industry is paying enough attention to cinema's sustainable transformation initiative.

Originality and worth

The present study examines why people use OTT platforms but also recognizes the reason for decreasing moviegoers’ numbers after the first wave of the COVID-19. In China, the current research landscape is significantly fragmented between OTT platforms and movie theaters by examining movie lovers. This exploratory research provides valuable guidance for OTT subscription service providers, cinema owners, and film producers. The reality is that the cinema is going through the most challenging and demanding time in its history. Draw attention to the disruption of OTT platforms and film industries so that rising movie ticket costs and emerging pandemic threats get more significant consideration.

The study gives academics a modern view of the main elements that entice moviegoers to see a film and allows the theatre, film, and OTT industries to evaluate their strategies. Viewers will have to make tough choices because they no longer subscribe to pay all VOD-based OTT platforms, including music and games streaming services. OTT platforms establish themselves as digital storefront, even though they cannot fully replace traditional movie theatres. Although the number of people using OTT services is expected to grow in the future, the value of cinema and the cinematic experience will never diminish.

Study limitations and future scope

This research also has limits and issues do not address, and future researchers’ options are explored in light of these restrictions. In contrast, this preliminary study provides a valuable framework with evidence for studying the audience's use of OTT platforms and visiting the cinema in China. Despite using a nationwide sample (Tefertiller, 2020), this study's generalizability is restricted since it used a purposive and snowball sampling techniques. China's Zero-COVID policy made it difficult to collect data via stratified sampling. In addition, based on the incitements in the study, researchers in China and other countries may draw better profiles of the actual evolution of public liking, preferences, interests, and issues if they use a larger and more representative sample. Finally, adding India to the study would be intriguing compared to China.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to appreciate the known and unknown respondents for contributing to data gathering in China, particularly in Mainland China, by filling out our e-questionnaire and sharing it with their circle of friends to reach the target population. We also value the constructive comments and suggestions provided by Professor Pengfei Fu on the initial draft.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Muhammad Yaqoub https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4188-0273

Contributor Information

Muhammad Yaqoub, Fujian Normal University, China.

Zhang Jingwu, Fujian Normal University, China.

Suhas Suresh Ambekar, Symbiosis Centre for Management and Human Resource Development (SCMHRD), Symbiosis International (Deemed University), India.

References

- Abulibdeh A, Mansour S. (2022) Assessment of the effects of human mobility restrictions on COVID-19 prevalence in the global south. The Professional Geographer 74(1): 16–30. [Google Scholar]

- Austin BA. (1986) Motivations for movie attendance. Communication Quarterly 34(2): 115–126. [Google Scholar]

- Babrow AS. (1987) Student motives for watching soap operas. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 31(3): 309–321. [Google Scholar]

- Bano S, Cisheng W, Khan AN, et al. (2019) Whatsapp use and student’s psychological well-being: role of social capital and social integration. Children and Youth Services Review 103: 200–208. [Google Scholar]

- Bentley F, Silverman M, Bica M. (2019) Exploring online video watching behaviors. In: TVX 2019 - Proceedings of the 2019 ACM International Conference on Interactive Experiences for TV and Online Video June 4–6, Manchester, UK. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 108–117. 10.1145/3317697.3323355. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berman EA. (2017) An exploratory sequential mixed methods approach to understanding Researchers’ data management practices at UVM: integrated findings to develop research data services. Journal of EScience Librarianship 6(1): e1104. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya SS, Goswami S, Mehta R, et al. (2022) Examining the factors influencing adoption of over the top (OTT) services among Indian consumers. Journal of Science and Technology Policy Management 16: 652–682. [Google Scholar]

- Bhullar A, Chaudhary R. (2020) Key factors influencing users’ adoption towards OTT media platform: an empirical analysis. International Journal of Advanced Science and Technology 29(11s): 942–956. [Google Scholar]

- Blumler JG, Katz E. (1974) The Uses of Mass Communications: Current Perspectives on Gratifications Research. Beverly Hills: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton RN, Parasuraman A, Hoefnagels A, et al. (2013) Understanding Generation Y and their use of social media: a review and research agenda. Journal of Service Management 24(3): 245–267. [Google Scholar]

- Bouchrika I. (2022) Mobile vs desktop usage statistics for 2021/2022. Research.Com. Available at:https://research.com/software/mobile-vs-desktop-usage.

- Brzeski P. (2022) china retains global box office crown with $7.3B in 2021, down 26 percent from 2019 – The Hollywood reporter. Elisabeth D. Rabishaw; Victoria Gold. Available at:https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/movies/movie-news/china-tops-global-box-office-2021-1235069251/.

- Camilleri MA, Falzon L. (2021) Understanding motivations to use online streaming services: integrating the technology acceptance model (TAM) and the uses and gratifications theory (UGT). Spanish Journal of Marketing - ESIC 25(2): 217–238. [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee A, Gupta D. (2017) A study on the factors influencing the adoption/ usage of wearable gadgets. In: 2017 2nd IEEE International Conference on Recent Trends in Electronics, Information & Communication Technology (RTEICT), May 19–20, Bangalore, India. New York City: IEEE, pp. 1632–1635. 10.1109/RTEICT.2017.8256875. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chatterjee M, Pal S. (2020) Globalization propelled technology often ends up in its micro-localization: cinema viewing in the time of OTT. Global Media Journal-Indian Edition 12(1): 22. [Google Scholar]

- Chen CM. (2019) Evaluating the efficiency change and productivity progress of the top global telecom operators since OTT’s prevalence. Telecommunications Policy 43(7): 101805. [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y-NK. (2019) Competitions between OTT TV platforms and traditional television in Taiwan: a Niche analysis. Telecommunications Policy 43(9): 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng JW, Mitomo H. (2017) The underlying factors of the perceived usefulness of using smart wearable devices for disaster applications. Telematics and Informatics 34(2): 528–539. [Google Scholar]

- China Internet Network Information Center (CNNIC) (2022) The 50th statistical report on China’s internet development. Available at:https://www.cnnic.com.cn/IDR/.

- Cramer-Flood E. (2022) Worldwide subscription ott users forecast 2022. Available at:https://www.emarketer.com/content/worldwide-subscription-ott-users-forecast-2022.

- Creswell JW, Creswell JD. (2017) Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. 5th ed.Washington, DC: Sage Publications Inc. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/research-design/book255675. [Google Scholar]

- Dasgupta S, Grover P. (2019) Understanding adoption factors of over-the-top video services among millennial consumers. International Journal of Computer Engineering & Technology (IJCET) 10(1): 61–71. http://www.iaeme.com/. [Google Scholar]

- Denzin NK, Lincoln YS. (2011) The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research. 4th ed.New York: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Dishaw MT, Strong DM. (1999) Extending the technology acceptance model with task–technology fit constructs. Information & Management 36(1): 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Donar GB, Aydan S. (2022) Association of COVID-19 with lifestyle behaviours and socio-economic variables in Turkey: an analysis of Google Trends. The International Journal of Health Planning and Management 37(1): 281–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Mashaleh M, O’Brien WJ, Minchin RE. (2006) Firm performance and information technology utilization in the construction industry. Journal of Construction Engineering and Management 132(5): 499–507. [Google Scholar]

- Frost N. (2021) Qualitative Research Methods in Psychology: Combining Core Approaches 2e. 2nd ed.London: McGraw-Hill Education. [Google Scholar]

- Gonçalves V, Evens T, Alves AP, et al. (2014) Power and control strategies in online video services. In: 25th European Regional Conference of the International Telecommunications Society (ITS): “Disruptive Innovation in the ICT Industries: Challenges for European Policy and Business,”Brussels, Belgium, 22nd–25th June, 2014. Calgary: International Telecommunications Society (ITS). https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/101438. [Google Scholar]

- GT staff reporters. (2022). As another well-known cinema closes, moviegoers still have hope for future. Global Times. https://www.globaltimes.cn/page/202204/1259666.shtml.

- Gupta G, Singharia K. (2021) Consumption of OTT Media streaming in COVID-19 lockdown: insights from PLS analysis. Vision 25(1): 36–46. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes D. (2020) More than half of U.S. households now subscribe to multiple streaming services, study finds. Deadline. https://deadline.com/2020/08/more-than-half-of-u-s-households-now-subscribe-to-multiple-streaming-services-study-1203025747/.

- Hellweg A. (2021) VoD watching: an experience sampling study on motivations and perceived stress. In University of Twente. Netherlands: University of Twente, pp. 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hess J, Ley B, Ogonowski C, et al. (2011) Jumping between devices and services: Towards an integrated concept for social TV. In: EuroITV’11 - Proceedings of the 9th European Interactive TV Conference,June 29 – July 1,Lisbon, Portugal. New York, NY: Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 11–20. ; 10.1145/2000119.2000122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Husna F, Dewi RS. (2021) Islamic education movie: character learning through nussa-Rara movie. International Journal of Islamic Educational Psychology (IJIEP) 2(1): 36–52. [Google Scholar]

- Katz E, Blumler JG, Gurevitch M. (1973) Uses and gratifications research. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 37: 509–523. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly H. (2022) How to watch multiple streaming services for less. The Washington Post. Available at:https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2022/06/28/streaming-tv-tips/.

- Kim IK. (2021) The impact of social distancing on box-office revenue: evidence from the COVID-19 pandemic. Quantitative Marketing and Economics 19(1): 93–125. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. (2019) Korean popular cinema and television in the twenty-first century: Parallax views on national/transnational disjunctures. Journal of Popular Film and Television 47(1): 2–8. [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Kim S, Nam C. (2016) Competitive dynamics in the Korean video platform market: traditional pay TV platforms vs. OTT platforms. Telematics and Informatics 33(2): 711–721. [Google Scholar]

- Kim S, Lee C, Lee J, et al. (2021) Over-the-top bundled services in the Korean broadcasting and telecommunications market: consumer preference analysis using a mixed logit model. Telematics and Informatics 61: 101599. [Google Scholar]

- Koul S, Ambekar SS, Hudnurkar M. (2021) Determination and ranking of factors that are important in selecting an over-the-top video platform service among millennial consumers. International Journal of Innovation Science 13(1): 53–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kwateng KO, Yobanta AL, Amanor K. (2021) Hedonic and utilitarian perspective of mobile phones purchase intention. Journal of Contemporary Marketing Science 4(1): 44–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon Y, Park J, Son JY. (2021) Accurately or accidentally? Recommendation agent and search experience in over-the-top (OTT) services. Internet Research 31(2): 562–586. [Google Scholar]

- Latora MM. (2020) Netflix and Kill: A Framing and Uses and Gratifications Comparative Analysis of Serial Killer Representations in the Media. Normal, Illinois.: Illinois State University. [Google Scholar]

- Lee JS, Cho J. (2021) Determinants of continuance intention for over-the-top services. Social Behavior and Personality 49(12): 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lim C. (2021) Examining factors affecting local IPTV users’ intention to subscribe to global OTT service through their local IPTV service. In: 23rd Biennial Conference of the International Telecommunications Society (ITS): “Digital Societies and Industrial Transformations: Policies, Markets, and Technologies in a Post-Covid World,” Online Conference, Gothenburg, Sweden, 21st–23rd June, 2021. Calgary: International Telecommunications Society (ITS). https://www.econstor.eu/handle/10419/238036. [Google Scholar]

- Liu H. (2022) Analysis report on the development of Chinese film industry in 2021. Contemporary Cinema 2: 17–26. [Google Scholar]

- Liu H, Lu J. (2020) The report of Chinese film industry development in 2019. Contemporary Cinema 2: 15–26. Maoyan Entertainment (2021) Maoyan: China’s box office revenue surpassed RMB20 Billion in 2020 to become world’s largest movie market amid pandemic. Available at:https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/maoyan-chinas-box-office-revenue-surpassed-rmb20-billion-in-2020-to-become-worlds-largest-movie-market-amid-pandemic-301200097.html. [Google Scholar]

- Marne Y. (2021) Gen-Z preferences in the direction of OTT platforms replace television? Navrachana University.

- Massad VJ. (2018) Understanding the cord-cutters: an adoption/self-efficacy approach. International Journal on Media Management 20(3): 216–237. [Google Scholar]

- Media Smart (2021) India CTV report 2021: Mapping connected TV viewership in India and the opportunities for brands. Available at:https://www.agencyreporter.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Mapping-Connected-TV-Viewership-in-India.pdf.

- Menon D. (2022) Purchase and continuation intentions of over -the -top (OTT) video streaming platform subscriptions: a uses and gratification theory perspective. Telematics and Informatics Reports 5: 100006. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison JS, Kennedy S, Huang Y. (2022) China’s zero-Covid: What should the west do? Center for Strategic and International Studies. https://www.csis.org/analysis/chinas-zero-covid-what-should-west-do.

- MPA (2022) 2021 THEME report - Motion picture association. Available at:https://www.motionpictures.org/research-docs/2021-theme-report/.

- Mulla T. (2022) Assessing the factors influencing the adoption of over-the-top streaming platforms: a literature review from 2007 to 2021. Telematics and Informatics 69: 101797. [Google Scholar]

- Nagaraj S, Singh S, Yasa VR. (2021) Factors affecting consumers’ willingness to subscribe to over-the-top (OTT) video streaming services in India. Technology in Society 65: 101534. [Google Scholar]

- National Bureau of Statistics of China (2022) Households’ income and consumption expenditure in 2021. Available at:http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/PressRelease/202201/t20220118_1826649.html.

- Navarro JG. (2021) Favorite movie genres in the U.S. by gender 2018. Statista. Available at:https://www.statista.com/statistics/254115/favorite-movie-genres-in-the-us/.

- Nayak SC, Biswal SK. (2021) OTT Media streaming in COVID-19 lockdown: the Indian experience. Media Watch 12(3): 440–450. [Google Scholar]

- Nogueira J, Guardalben L, Cardoso B, et al. (2018) Catch-up TV forecasting: enabling next-generation over-the-top multimedia TV services. Multimedia Tools and Applications 77(12): 14527–14555. [Google Scholar]

- Ovum Market Study (2021) Bundle OTT service makes Indians spend more on their mobile and broadband subscriptions. Amdocs. Available at:https://www.amdocs.com/sites/default/files/ovum-ott-study-infographic-jan21.pdf.

- Parikh N. (2020) The emergence of OTT platforms during the pandemic and its future scope. Navrachana University. Available at:http://27.109.7.66:8080/xmlui/bitstream/handle/123456789/619/Nandani-THE%20EMERGENCE%20OF%20OTT%20PLATFORMS%20DURING%20THE%20PANDEMIC%20AND%20ITS%20FUTURE%20SCOPE%20-%20Bhargav%20pancholi.pdf?sequence=1.

- Patnaik R, Shah R, More U. (2021) Rise of OTT platforms: effect of the C-19 pandemic. PalArch’s Journal of Archaeology of Egypt / Egyptology 18(7): 2277–2287. [Google Scholar]

- Puthiyakath HH, Goswami MP. (2021) Is over the top video platform the game changer over traditional TV channels in India? A niche analysis. Asia Pacific Media Educator 31(1): 133–150. [Google Scholar]

- PWC (2022) Global entertainment & media 2022–2026 perspectives report. Available at:https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/industries/tmt/media/outlook/outlook-perspectives.html.

- PwC China (2020) Global entertainment and media outlook 2020-2024: China summary. In PwC China. Available at:https://www.pwccn.com/en/industries/telecommunications-media-and-technology/publications/china-entertainment-and-media-outlook-2020-2024.html.

- PwC China (2022) PwC China: Mainland China edition: Global entertainment & media outlook 2022–2026. Available at:https://www.pwccn.com/en/industries/telecommunications-media-and-technology/publications/entertainment-and-media-outlook-2022-2026.html.

- PWC Hong Kong (2020) Global M&E outlook 2020-2024: Hong Kong summary. Available at:https://www.iabhongkong.com/sites/default/files/2020-12/china-entertainment-and-media-outlook-2020-2024.pdf.

- Quan-Haase A, Young AL. (2010) Uses and gratifications of social Media: a comparison of Facebook and instant messaging. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society 30(5): 350–361. [Google Scholar]

- Rao S. (2007) The globalization of Bollywood: an ethnography of non-elite audiences in India. The Communication Review 10(1): 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo L, FitzGerald D. (2020, December 30). Forget the streaming wars—pandemic-stricken 2020 lifted Netflix and others. The Wall Street Journal. Available at:https://www.wsj.com/articles/forget-the-streaming-warspandemic-stricken-2020-lifted-netflix-and-others-11609338780.

- Sadana M, Sharma D. (2021) How over-the-top (OTT) platforms engage young consumers over traditional pay television service? An analysis of changing consumer preferences and gamification. Young Consumers 22(3): 348–367. [Google Scholar]

- Safiranita T, Muttaqin Z, Sukarsa DE, et al. (2021) The role of over the top (OTT) service on utilization of telecommunication infrastructure based on Indonesian tax and non-tax policy. Journal of Southwest Jiaotong University 56(5): 67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Sahu G, Gaur L, Singh G. (2021) Applying niche and gratification theory approach to examine the users’ indulgence towards over-the-top platforms and conventional TV. Telematics and Informatics 65: 101713. [Google Scholar]

- Seo C. (2020) A study on the OTT evaluation factors using AHP. The Journal of Information Systems 29(4): 193–208. [Google Scholar]

- Shah MH, Yaqoub M, Jingwu Z. (2020) Post-pandemic impacts of COVID-19 on film industry worldwide and in China. Global Media Journal - Pakistan Edition 8(2): 28–44. [Google Scholar]

- Sherman N. (2021) Netflix: Four things which have driven its success. BBC. Available at:https://www.bbc.com/news/business-55723926.

- Shin S, Park J. (2021) Factors affecting users’ satisfaction and dissatisfaction of OTT services in South Korea. Telecommunications Policy 45(9): 102203. [Google Scholar]

- Shreya (2022) 8 Chinese streaming platforms to amplify your business. AdChina.Io. Available at:https://www.adchina.io/8-chinese-streaming-platforms-to-amplify-your-business/.

- Snelson CL. (2016) Qualitative and mixed methods social Media research: a review of the literature. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 15(1): 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Song C, Liu W, Liu Z, et al. (2019) User abnormal behavior recommendation via multilayer network. PLOS ONE 14(12): e0224684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sowbarnika S, Jayanthi M. (2021) Initial viewing motivation sets towards TV and OTT. International Journal of Management (IJM) 12(3): 1189–1196. [Google Scholar]

- Statista Research Department (2022) Global: penetration rate of OTT videos 2017-2026. Available at:https://www.statista.com/forecasts/1207877/ott-video-penetration-rate-worldwide.

- Stoll J. (2021) SVOD service multiple subscriptions in the U.S. 2020. Statista. Available at:https://www.statista.com/statistics/778912/video-streaming-service-multiple-subscriptions/.

- Su W. (2021) From visual pleasure to global imagination: Chinese youth’s reception of hollywood films. Asian Journal of Communication 31(6): 520–535. [Google Scholar]

- Tefertiller A. (2020) Cable cord-cutting and streaming adoption: advertising avoidance and technology acceptance in television innovation. Telematics and Informatics 51: 101416. [Google Scholar]

- Testoni I, Rossi E, Pompele S, et al. (2021) Catharsis through cinema: an Italian qualitative study on watching tragedies to mitigate the fear of COVID-19. Frontiers in Psychiatry 12: 622174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Theocharis Y, Cardenal A, Jin S, et al. (2021) Does the platform matter? Social media and COVID-19 conspiracy theory beliefs in 17 countries. New Media and Society: 1–26. 10.1177/14614448211045666/ASSET/IMAGES/LARGE/10.1177_14614448211045666-FIG4.JPEG. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomala LL. (2021) Distribution of box office revenue in China from 2018 to 2020, by genre. Statista. Available at:https://www.statista.com/statistics/1237229/china-box-office-revenue-share-genre/.

- Thomala LL. (2022a) China: moviegoer age distribution 2021. Statista. Available at:https://www.statista.com/statistics/1061081/china-cinema-audience-age-distribution/.

- Thomala LL. (2022b) Annual growth of moviegoer number in China 2010-2021. Statista. Available at:https://www.statista.com/statistics/476811/china-cinema-audience-size-annual-growth/.

- Thomala LL. (2022c) China: Tencent Video user age distribution 2022. Statista. Available at:https://www.statista.com/statistics/1321184/china-tencent-video-user-age-distribution/.

- Tolba AA, Zoghaib SZ. (2022) Understanding the binge-watching phenomenon on netflix and its association with depression and loneliness in Egyptian adults. Media Watch 13(3): 264–279. [Google Scholar]

- Valecha P. (2017) Multi-screening behavior of young Indians and its implications for programmers and advertisers. Media Watch 8(1-Special Issue): 75–85 [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Teo TSH, Dwivedi Y, et al. (2021) Mobile services use and citizen satisfaction in government: integrating social benefits and uses and gratifications theory. Information Technology and People 34(4): 1313–1337. [Google Scholar]

- Wang WY, Lobato R. (2019) Chinese Video streaming services in the context of global platform studies. Chinese Journal of Communication 12(3): 356–371. [Google Scholar]

- Williams SP, Thondhlana G, Kua HW. (2020) Electricity use behaviour in a high-income neighbourhood in johannesburg, South Africa. Sustainability 12(11): 4571. [Google Scholar]

- Xia J. (2022) China 5G: opportunities and challenges. Telecommunications Policy 46: 102295. [Google Scholar]

- Xinhua News Agency (2019) 2019 Chinese films showed a “report card”: 64.266 billion yuan box office record high. http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2019-12/31/content_5465531.htm.

- Yang L. (2022) Analysis of the main reasons for continuous payment of OTT platform users in China. Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Social Development and Media Communication (SDMC 2021) 631: 1270–1273. [Google Scholar]

- Yaqoub M, Jingwu Z, Xuyao Z, et al. (2022a) Future of video streaming platforms and mainstream cinema: a case study of fujian province, China. Journal of Peace, Development and Communication 6(2): 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Yaqoub M, Khan MK, Tanveer A. (2022b) Digital disruption: rising use of video services among Chinese netizens. Pakistan Journal of International Affairs (PJIA) 5(1): 34–54. [Google Scholar]

- Ying X. (2022) Promote the diversified development of Chinese film themes and genres. Literature and Art Journal o4: 1. [Google Scholar]

- Yousaf A, Mishra A, Taheri B, et al. (2021) A cross-country analysis of the determinants of customer recommendation intentions for over-the-top (OTT) platforms. Information & Management 58(8): 103543. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao EJ. (2016) Getting connected in China: Taming the mobile screen. In Handbook of Cultural and Creative Industries in China. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd, pp. 396–411. 10.4337/9781782549864.00039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]