Abstract

Background

eHealth tools such as patient portals and personal health records, also known as patient-centered digital health records, can engage and empower individuals with chronic health conditions. Patients who are highly engaged in their care have improved disease knowledge, self-management skills, and clinical outcomes.

Objective

We aimed to systematically review the effects of patient-centered digital health records on clinical and patient-reported outcomes, health care utilization, and satisfaction among patients with chronic conditions and to assess the feasibility and acceptability of their use.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, Cochrane, CINAHL, Embase, and PsycINFO databases between January 2000 and December 2021. PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines were followed. Eligible studies were those evaluating digital health records intended for nonhospitalized adult or pediatric patients with a chronic condition. Patients with a high disease burden were a subgroup of interest. Primary outcomes included clinical and patient-reported health outcomes and health care utilization. Secondary outcomes included satisfaction, feasibility, and acceptability. Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal tools were used for quality assessment. Two reviewers screened titles, abstracts, and full texts. Associations between health record use and outcomes were categorized as beneficial, neutral or clinically nonrelevant, or undesired.

Results

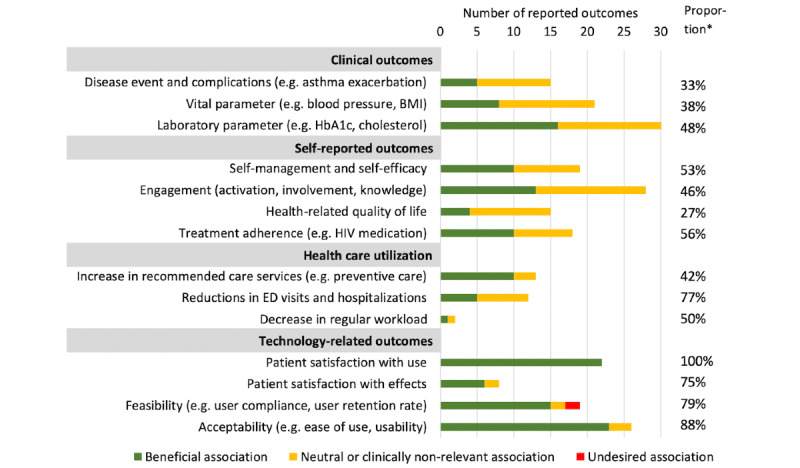

Of the 7716 unique publications examined, 81 (1%) met the eligibility criteria, with a total of 1,639,556 participants across all studies. The most commonly studied diseases included diabetes mellitus (37/81, 46%), cardiopulmonary conditions (21/81, 26%), and hematology-oncology conditions (14/81, 17%). One-third (24/81, 30%) of the studies were randomized controlled trials. Of the 81 studies that met the eligibility criteria, 16 (20%) were of high methodological quality. Reported outcomes varied across studies. The benefits of patient-centered digital health records were most frequently reported in the category health care utilization on the “use of recommended care services” (10/13, 77%), on the patient-reported outcomes “disease knowledge” (7/10, 70%), “patient engagement” (13/28, 56%), “treatment adherence” (10/18, 56%), and “self-management and self-efficacy” (10/19, 53%), and on the clinical outcome “laboratory parameters,” including HbA1c and low-density lipoprotein (LDL; 16/33, 48%). Beneficial effects on “health-related quality of life” were seen in only 27% (4/15) of studies. Patient satisfaction (28/30, 93%), feasibility (15/19, 97%), and acceptability (23/26, 88%) were positively evaluated. More beneficial effects were reported for digital health records that predominantly focus on active features. Beneficial effects were less frequently observed among patients with a high disease burden and among high-quality studies. No unfavorable effects were observed.

Conclusions

The use of patient-centered digital health records in nonhospitalized individuals with chronic health conditions is potentially associated with considerable beneficial effects on health care utilization, treatment adherence, and self-management or self-efficacy. However, for firm conclusions, more studies of high methodological quality are required.

Trial Registration

PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) CRD42020213285; https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=213285

Keywords: telemedicine, health records, personal, electronic health records, outcome assessment, health care

Introduction

Background

The prevalence and disease burden of chronic health conditions is on the rise. The World Health Organization predicts that by 2030, chronic noncommunicable health conditions will account for >50% of the total disease burden [1,2]. In particular, cardiovascular conditions, cancer, respiratory conditions, and diabetes have the highest morbidity and mortality [1]. Currently, 60% of the US population has at least 1 chronic condition and 42% of the population has multiple chronic conditions [3]. This results in a high individual disease burden owing to the large impact on social participation and required patient self-management skills. Self-management refers to a person’s ability to manage the clinical, psychosocial, and societal aspects of their illness and its care [4]. In contrast, self-efficacy is a person’s belief that he or she can successfully execute this behavior [4]. Apart from a high individual disease burden, the prevalence of chronic conditions imposes a high macroeconomic burden [5]. Furthermore, an increasing shortage of health care providers is expected, among others in the United States [6] and Europe [7,8]. In combination with the increased pressure put on health systems by unexpected events such as the COVID-19 pandemic, this shortage threatens the delivery of essential health services [9]. To preserve the access to care for all patients, new technologies are increasingly being developed and adopted, including patient-centered digital health records.

Such patient-centered digital health records can significantly help engage and empower patients with a chronic health condition [10-13]. Patient-centered digital health records enable patients to take on a more active role in their care by allowing them to view parts of their medical records, such as medication lists, laboratory and imaging results, allergies, and correspondence. Other common features include secure messaging, requesting prescription refills, video consultation, paying bills, and managing appointments. Examples of patient-centered digital health records include patient portals and personal health records (PHRs). Patient-centered digital health records differ in the volume and detail of the provided medical data, functionalities, and level of patient control, as shown in Textbox 1. Highly engaged patients are reported to have increased disease knowledge, better self-management, more self-efficacy, and improved clinical outcomes [14-16]. The effects of using patient-centered digital health records may be most substantial for patients with chronic conditions. Many self-management skills are required, and their potential gains are the highest. Not only patients but the entire health care system might benefit from an increased adoption of patient-centered digital health records.

Proposed taxonomy of patient-centered digital health records [10,17-21].

Electronic health record (EHR): a digital version of a health care provider’s paper chart, used by health care professionals alone. Patients cannot access data in an EHR. An EHR might contain data from one health care institution or from multiple institutions. Its scope can range from regional, to national, or international.

Patient portal: the patient-facing interface of an EHR that enables people to view sections of their medical record. This might include access to test results, medication lists, or therapeutic instructions. Health care providers or health care offices determine what health information is accessible for patients. Patient portals often have additional features such as patient-professional messaging, requesting prescription refills, scheduling appointments, or communicating patient-reported outcomes. By definition, patient portals are “tethered,” in which “tethered” refers to a patient portal’s connection to an EHR. Occasionally, a patient portal is referred to as a tethered personal health record (PHR).

PHR: a PHR is similar to a patient portal and can have similar features. However, the main difference is that contents are managed and maintained by individuals, not health care providers. People can access, manage, and share their health information, and that of others for whom they are authorized, such as parents or caretakers. Health information from different health care institutions may reside in a single patient-managed PHR. In general, PHRs are not tethered unless otherwise specified. Few tethered PHRs currently exist but are increasingly being developed [22].

Patient-centered digital health records: an umbrella term referring to patient portals, tethered PHRs, and part of the untethered PHRs. Patient-centered digital health records enable a 2-way exchange of health information between patients and the health care system and provide patients with the ability to view, download, or transmit their health information on the web. This health information is updated at regular intervals. In addition, it enables communication between patients and the health care system, either by adding or editing health information, exchanging patient-reported outcomes, or by using communication tools such as messaging. Additional functionalities are often present.

“Electronic medical record” is an outdated term [21]. It can be considered a professional-centered EHR with limited functionalities.

Currently, huge investments of time and resources are made in patient-centered digital health records. However, limited insight exists in how the use of patient-centered digital health records by patients with a broad range of chronic conditions affects clinical and patient-reported outcomes and health care utilization. Moreover, we lack an overview of their effects on patient satisfaction, and the feasibility and acceptability of their use by people with chronic conditions. Previous systematic reviews focused on one health condition [23], focused on one type of digital health record [24-27], investigated a select set of health outcomes [24,26,28], or are now obsolete in this rapidly changing technological landscape [23,25,27].

Objectives

Therefore, in this systematic review, we summarized the available evidence on patient-centered digital health records. Our primary objective was to assess how patient-centered digital health records for nonhospitalized patients with chronic conditions affect clinical and patient-reported health outcomes and health care utilization. Our secondary objective was to evaluate patient satisfaction with and feasibility and acceptability of using patient-centered digital health records. Results of this systematic review may help guide future development and implementation.

Methods

The protocol for this study was registered in the International PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) Register of Systematic Reviews (CRD42020213285) [29]. The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines were followed [30].

Literature Search

A medical librarian (MB) conducted the original literature search using the following databases: MEDLINE, Cochrane Library, CINAHL, Embase, and PsycINFO. All original studies published between January 1, 2000, and December 1, 2020, were assessed. A search update in MEDLINE was performed for all studies published between December 1, 2020, and December 31, 2021. Multimedia Appendix 1 presents the full search strategy. Articles published before 2000 were excluded because of the rapidly changing field of digital health technology [30].

Eligibility Criteria

Patient-centered digital health records were defined as mobile health (mHealth) or eHealth technologies that enable a 2-way exchange of health information between patients and the health care system, such as patient portals, PHRs, or mHealth apps with a health record functionality. A patient-centered digital health record provides patients with the ability to view, download, or transmit their health information on the web. This health information was updated at regular intervals. In addition, a patient-centered digital health record allows for communication between patients and the health care system, either by adding or editing health information, exchanging patient-reported outcomes, or by using communication tools such as messaging. Several other functionalities are common, but were not considered essential; for example, appointment scheduling, requesting prescription refill, viewing educational material, using decision support tools, and using connected wearables. Exclusion criteria were nondigital health records, digital health records intended for hospitalized patients, and digital health records that are not accessible to patients, such as the clinician-facing components of the electronic health record (EHR).

Studies

Studies investigating patient-centered digital health records intended for nonhospitalized patients with a chronic health condition were included. Only studies published in English were included. Eligible studies included randomized controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-experimental studies, nonexperimental observational studies (including cohort and cross-sectional studies), and pilot or feasibility studies. Of mixed methods studies, only nonqualitative parts were used for data extraction. Studies that only described health care providers’ experiences were excluded.

Participants

Studies on patients with a chronic health condition of all age groups were considered. Chronic conditions included all diseases with a moderate to high disease burden and moderate to high impact on daily life. Consequently, these conditions demand considerable self-management skills from patients to manage the clinical, psychosocial, and societal aspects of chronic condition and its care. The selection of chronic conditions included in our search strategy was based on the Charlson Comorbidity Index, other literature, and clinical expertise [31,32]. Diseases included cancer, arthritis, HIV, AIDS, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic heart conditions, hematologic disease, chronic kidney disease, celiac disease, inflammatory bowel disease, cystic fibrosis, diabetes mellitus, and multiple sclerosis (MS).

Outcomes

Studies were required to report at least one primary or secondary outcome. Primary outcomes were clinical outcomes (including disease events and complications, vital parameters, and laboratory parameters), patient-reported outcomes (including self-management and self-efficacy, patient engagement, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), stress and anxiety, and treatment adherence), and health care utilization (including the number of emergency department [ED] visits and hospitalizations, the use of preventive or recommended care services by patients, and regular workload for health care professionals). Secondary outcomes included technology-related outcomes (including patient satisfaction, feasibility, and acceptability). Definitions and examples of these 13 outcomes are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Definitions and examples of all health outcomes included in this systematic review.

| Included study outcomes | Definitions and examples | |

| Clinical outcomes | ||

|

|

Disease events and complications |

|

|

|

Vital parameters |

|

|

|

Laboratory parameters |

|

| Patient-reported outcomes | ||

|

|

Self-management and self-efficacy |

|

|

|

Patient engagement |

|

|

|

Health-related quality of life |

|

|

|

Treatment adherence |

|

| Health care utilization: >all types of encounters between patients and health care providers, including EDd visits, hospitalizations, outpatient clinic appointments, and telephone calls | ||

|

|

ED visits and hospitalizations |

|

|

|

Recommended care services |

|

|

|

Regular workload |

|

| Technology-related outcomes | ||

|

|

Patient satisfaction |

|

|

|

Feasibility |

|

|

|

Acceptability |

|

aHbA1c: glycated hemoglobin.

bLDL: low-density lipoprotein.

ceGFR: estimated glomerular filtration rate.

dED: emergency department.

Data Extraction

Two independent reviewers (MB and SB) assessed titles, abstracts, and full texts for eligibility. Disagreements were resolved by discussion, if necessary, with a third reviewer (SG).

A modified, electronic version of the standardized Cochrane data extraction form [39] was used to extract the following data items: first author’s name; publication year; study design; disease or diseases studied; study aim; country and setting; participants’ age and sex; sample size; inclusion and exclusion criteria; follow-up duration; description, features, and purpose of the patient-centered digital health record and (if applicable) of the comparator; size and description of the control group (if applicable); device used; description of health outcomes and results; and main study findings.

Quality Appraisal

For quality appraisal, Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) critical appraisal tools for RCTs, cross-sectional studies, cohort studies, and quasi-experimental studies were used [40]. JBI tools were modified to better suit the assessment of digital health record studies. Several items were added, including adequate patient-centered digital health record descriptions and selection bias measures, as presented in Multimedia Appendix 2. As the JBI tools differed in the number of items, all scores were converted to a 15-point scale. Articles with a score of ³12 were considered of “high quality,” between 8.5 and 11.9 of “medium quality,” and <8.5 of “low quality.”

Data Synthesis

Associations between patient-centered digital health record use and health outcomes were categorized in 3 groups: “beneficial,” “neutral or clinically nonrelevant,” or “undesired.” Categorizations were determined by our interpretation of study findings, based on meaningful clinical effects and statistical significance (P<.05), and could therefore differ from the authors’ conclusions. Statistical significance was considered relevant only if the effect size were clinically significant. If available, minimal clinically important differences were used to assess effect sizes. The summarization of effects was based on the vote-counting method, as no meta-analysis could be performed. The findings were summarized for all conditions, grouped by disease category (diabetes mellitus, cardiopulmonary diseases, hematology-oncology diseases, and other diseases), and grouped according to outcome type (clinical outcomes, patient-reported outcomes, health care utilization, and technology-related outcomes).

Subgroup Analyses

Several subgroup analyses were performed. The first subgroup included conditions with a high disease burden. These included conditions with either impaired social participation or that require a high level of self-management skills. Impaired social participation was defined as being unable to participate in work or school or engage with friends and family as desired because of the condition or its treatment. High self-management skills are defined as recurrent actions demanded from patients to prevent or treat the disease or its consequences, including high disease-related knowledge needed to actively engage in decision-making. This subgroup was determined based on clinical expertise of the study team. Second, we assessed 2 subgroups: patient-centered digital health records that predominantly offered passive features and those that predominantly offered active features. Passive features are those through which the patient receives information but does not actively add information. Active features are those in which the patient performs an action and actively engages with the digital health record. The third subgroup of interest included studies with high methodological quality. A sensitivity analysis was performed to investigate whether our results were influenced by poor quality studies. Finally, the subgroups of interest were studies that included older participants (mean age >55 years), a high number of female participants (>45%), or a racially diverse population (<50% White participants).

Results

Overview

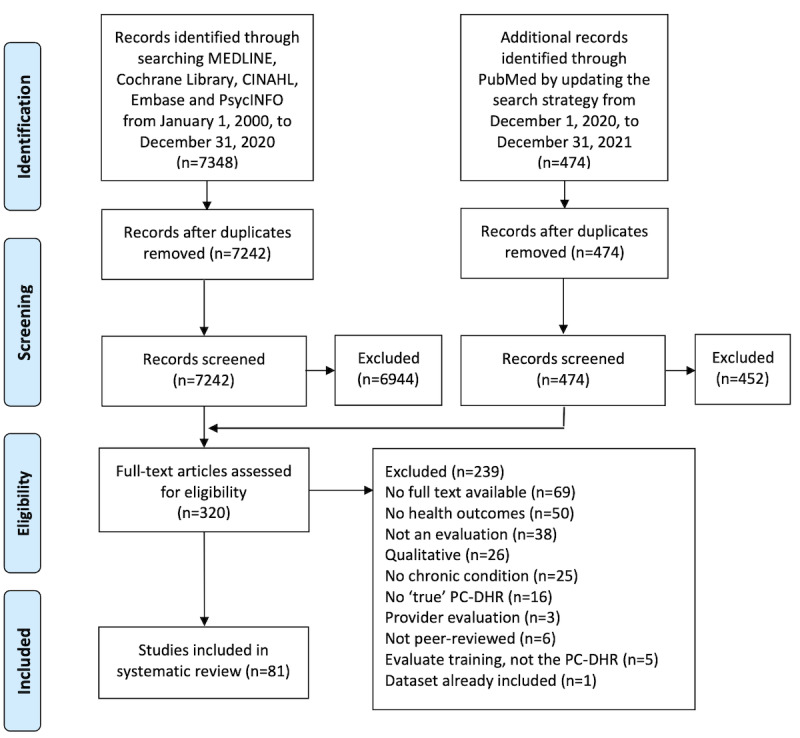

The search yielded 7716 unique publications. After screening the titles and abstracts, 320 full-text articles were retrieved. A total of 81 articles met the inclusion criteria. No non-English articles that met the inclusion criteria were identified. Figure 1 shows the study PRISMA flowchart. In total, 1,639,556 participants were included in the studies of this systematic review. Most (74/81, 91%) studies included only adult participants. Of the total 1,369,913 participants, 99% (n=1,629,660) were adults. Nine studies included children or their parents, with a total number of 9297 children and 599 parents. Sample sizes of studies varied from 10 to 267,208 participants. Furthermore, 46% (747,370/1,639,556) of the participants were female. Of the 81 included studies, health literacy was reported by 7 (9%) studies and insurance status by 15 (20%) studies. Race distribution was reported by 74% (60/81) of studies, of which 47 (78%) studies included a population of which more than half were White and 26 (43%) studies of which >75% were White.

Figure 1.

PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram. PC-DHR: patient-centered digital health record.

Study Characteristics

Study characteristics are presented in Tables 2-5 (36 studies are listed in Table 2; 11 studies are listed in Table 3, 14 studies are listed in Table 4, and 20 studies are listed in Table 5). Most investigated conditions were type 1 or 2 diabetes mellitus (37/81, 46%), cardiovascular conditions (14/81, 17%), and malignancies (11/81, 14%). Studies were mostly conducted in the following countries: United States (58/81, 72%), the Netherlands (7/81, 9%), Canada (5/81, 6%), and United Kingdom (3/81, 4%). In addition, 30% (24/81) of the studies were RCTs, 27% (22/81) were cross-sectional studies, 20% (16/81) were retrospective observational cohort studies, and 23% (18/81) were quasi-experimental studies, including pretest-posttest and feasibility studies. One study was a secondary data analysis of the intervention group in an RCT. Of the 55 studies that reported follow-up durations, 6 (7%) studies had a follow-up of less than a month, 25 (31%) studies between 1 and 6 months, 14 (17%) studied between 7 and 12 months, and 10 (12%) studies of >12 months.

Table 2.

Study characteristics of studies investigating diabetes mellitus (of 37 studies investigating diabetes mellitus, 36 are listed in Table 2).a

| Author, year | Country, setting | Study population, disease, controlled? | Burdenb | Study design | Sample size | Age (years)c, mean (SD) | Genderc (female), n (%) | Racec (White), n (%) |

| Bailey et al [41], 2019 | United States, 2 academic hospitals | Adults with DMd, on high-risk medication | − | Pilot or feasibility | 100 | 56 (11) | 57 (57) | 48 (48) |

| Boogerd et al [42], 2017 | Netherlands, 7 medical centers | Parents of children <13 years with DM type 1 | + | Pilot or feasibility | Ie=54, Cf=51 | 9.1 (2.7): Children | 30 (56) | NRg |

| Byczkowski et al [43], 2014 | United States, 1 academic hospital | Parents of children with DM (or CFh or JIAi) | ± | Cross-sectional | I=126, C=89 | 11 (NR) | 69 (54.8) | 115 (91.3) |

| Chung et al [44], 2017 | United States, outpatient care organization | Adults with DM | − | Cohort | I=12,485, C=2831 | 56 (12) | 5493 (44) | 5119 (41) |

| Conway et al [45], 2019 | United Kingdom, Scotland’s health system | Patients with DM | − | Cross-sectional | 1095 | 58 (12) | 405 (36.99) | 873 (78.73) |

| Devkota et al [46], 2016 | United States, 6 PCPsj | Patients with DM type 2 | − | Cohort | I=409, C=1101 | 58 (12)k | 235 (57.5) | 250 (61.1) |

| Dixon et al [47], 2016 | United States, 3 community centers | Adults with DM type 2 | − | Pilot or feasibility | 96 | 53 (11) | 56 (58) | 47 (49) |

| Graetz et al [48], 2018 | United States, integrated health system | Adults with DM | − | Cross-sectional | 267,208 | NR | 127,458 (47.7) | 116,770 (43.7) |

| Graetz et al [49], 2020 | United States, integrated health system | Adults with DM with at least 1 oral drug | − | Cross-sectional | 111,463 | 64 (13) | 51,545 (46.24) | 45,205 (40.56) |

| Grant et al [50], 2008 | United States, 11 PCPs | Adults with DM using medication | − | RCTl | I=126, C=118 | 59 (10) | 54 (42.9) | 117 (92.9) |

| Lau et al [51], 2014 | Canada, 1 academic hospital | Adults with DM | − | Cohort | I=50, C=107 | 55 (14) | 22 (44) | NR |

| Lyles et al [52], 2016 | United States, integrated health system | Adults with DM type 2 using statins | − | Cohort | I=8705, C=9055 | 61 (11)k | 4013 (46.1) | 3134 (36)k |

| Martinez et al [53], 2021 | United States, 4 medical centers | Adults with DM type 2 using medication | − | Pilot or feasibility | 60 | 58 (13) | 33 (55) | 41 (68) |

| McCarrier et al [54], 2009 | United States, 1 diabetes clinic | Adults <50 years with uncontrolled DM type 1 | + | RCT | I=41, C=36 | 57 (8) | 15 (37) | 39 (95) |

| Osborn et al [55], 2013 | United States, 1 academic hospital | Adults with DM type 2 using medication | − | Cross-sectional | I=62, C=13 | 57 (8) | 39 (63) | 46 (74) |

| Price-Haywood and Luo [56], 2017 | United States, integrated health system | Adults with DM or HTm | − | Cohort | I=10,497, C=90,522 | NR | 6205 (59.11) | 8055 (76.74) |

| Price-Haywood et al [57], 2018 | United States, integrated health system | Adults with DM or HT | − | Cohort | I=11,138, C=89,880 | 58 (13) | 6,204 (55.7) | NR |

| Quinn et al [58], 2018 | United States, 26 PCPs | Adults <65 years with DM type 2 | − | RCT | I=82, C=25 | 54 (8) | 39 (48) | 51 (62) |

| Reed et al [59], 2015 | United States, integrated health system | Adults with DM, HT, CADn, asthma, or CHFo | ± | Cross-sectional | 1041 | NR | 587 (56.4) | 618 (59.4) |

| Reed et al [60], 2019 | United States, integrated health system | Adults with DM+HT, CAD, asthma, or CHF | ± | Cross-sectional | 165,477 | NR | 79,594 (48.1) | NR (60.9) |

| Reed et al [61], 2019 | United States, integrated health system | Adults with DM, asthma, HT, CAD, CHF or CV event risk | ± | Cross-sectional | I=1392, C=407 | NR | 719 (51.7) | 816 (58.6) |

| Riippa et al [62], 2014 | Finland, 10 PCPs | Adults with DM, HT or HCp | − | RCT | I=80, C=57 | 61 (9) | 45 (56) | NR |

| Riippa et al [63], 2015 | Finland, 10 PCPs | Adults with DM, HT or HC | − | RCT | I=80, C=57 | 61 (9) | 45 (56) | NR |

| Robinson et al [64], 2020 | United States, 1 veteran hospital | Veterans with uncontrolled DM type 2 | − | Cross-sectional | I=446, C=754 | 66 (8) | 28 (6.3) | 384 (86.1) |

| Ronda et al [65], 2014 | Netherlands, 62 PCPs+1 hospital | Adults with DM | − | Cross-sectional | I=413, C=758 | 64 (12) | 154 (37.3) | 383 (93.6) |

| Ronda et al [66], 2015 | Netherlands, 62 PCPs+1 hospital | Adults with DM | − | Cross-sectional | I=413, C=219 | 59 (13) | 154 (37.3) | 383 (93.6) |

| Sabo et al [67], 2021 | United States, 21 practices | Adults with DM type 2 | − | Cohort | I=189, C=148 | 61 (13) | 75 (40.9) | 113 (72.9) |

| Sarkar et al [68], 2014 | United States, integrated health system | Adults with DM | − | Cohort | I=8705, C=9055 | 61 (11)k | 4013 (46.1) | 5072 (58.27) |

| Seo et al [69], 2020 | South Korea, 1 academic hospital | Patients with DM | − | Cohort | I=133, C=7320 | 54 (10) | 23 (17.3) | NR |

| Sharit et al [70], 2018 | United States, 1 veterans center | Overweight veterans with prediabetes | − | Pilot or feasibility | 38 | 58 (8) | 9 (24) | 8 (21)k |

| Shimada et al [71], 2016 | United States, Veteran registry | Veterans with uncontrolled DM, HT or LDLq | − | Cohort | I=50,482, C=61,204 | 61 (10) | 2060 (4.08) | 35,761 (70.84) |

| Tenforde et al [72], 2012 | United States, 1 community hospital | Adults <75 years with DM | − | Cohort | I=4036, C=6710 | 59 (10) | 1857 (46)k | 3,390 (84)k |

| van Vugt et al [73], 2016 | Netherlands, 52 PCPs | Patients with DM type 2 | − | RCT | I=66, C=66 | 68 (10) | 54 (41) | 91 (69) |

| Vo et al [74], 2019 | United States, integrated health system | Adults <80 years with DM type 2 | − | RCT | I=673, C=603 | 61 (10) | 296 (44) | 394 (58.5) |

| Wald et al [75], 2009 | United States, 230 PCPs | Patients with DM type 2 | − | RCT | 126 | 59 (NR) | 53 (42.1) | 117 (92.9) |

| Zocchi et al [76], 2021 | United States, nationwide | Patients with DM type 2, partly uncontrolled | − | Cohort | 95,043 | 63 (10) | 4,339 (4.57) | 68,954 (72.55) |

aAll studies are listed in Tables 2-5 and are reported in the disease category of the condition that is most prominently investigated. The study by Druss et al [77] is therefore listed in Table 5.

bIf conditions are considered to have a high disease burden or demand high self-management skills, a positive sign is shown. Otherwise, a sign is indicated. A ± sign indicates that multiple diseases have been studied, and only some of the diseases were considered to have a high disease burden.

cIf available, age (years), gender, and race were reported by digital health record users (“the intervention group”).

dDM: diabetes mellitus.

eI: intervention.

fC: control.

gNR: not reported.

hCF: cystic fibrosis.

iJIA: juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

jPCP: primary care practice.

kPresented numbers were estimated based on the data provided in the original articles.

lRCT: randomized controlled trial.

mHT: hypertension.

nCAD: coronary artery disease.

oCHF: congestive heart failure.

pHC: hypercholesterolemia.

qLDL: low-density lipoprotein.

Table 5.

Study characteristics of studies investigating other diseases (of 21 studies investigating other diseases, 20 are listed in Table 5). Diseases include kidney disease (n=3, 15%), mental health disorders (n=3, 15%), multiple sclerosis (n=2, 10%), inflammatory bowel disease (n=2, 10%), rheumatologic conditions (n=2, 10%), and others (n=8, 40%).a

| Author, year | Country, setting | Study population, disease, controlled? | Burdenb | Study design | Sample size | Age (years)c, mean (SD) | Genderc (female), n (%) | Racec (White), n (%) |

| Anand et al [103], 2017 | Thailand, HIV clinic | MSMd and transgender women with HIV, partly uncontrolled | + | RCTe | 186 | 30 (10)f | 7 (4) | 0 (0) |

| Bidmead and Marshall [104], 2016 | United Kingdom, 1 community hospital | Patients with IBDg | + | Cross-sectional | 60 | NRh | NR | NR |

| Crouch et al [105], 2015 | United States, 1 HIV clinic | Veterans with HIV, partly uncontrolled | + | Cross-sectional | Ii=20, Cj=20 | 43 (11) | 1 (5) | 19 (95) |

| Druss et al [106], 2014 | United States, 1 mental health center | Patients with a mental disorder+chronic condition | + | RCT | I=85, C=85 | 49 (7) | 42 (49) | 13 (15) |

| Druss et al [77], 2020 | United States, 2 mental health centers | Patients with a mental disorder+DMk, HTl, or HCm | + | RCT | I=156, C=155 | 51 (6.5) | 95 (61) | 29 (19) |

| Jhamb et al [107], 2015 | United States, 4 nephrology clinics | Adults visiting nephrology clinics, partly uncontrolled | + | Cross-sectional | 1098 | 58 (16) | 549 (50) | 952 (86.7) |

| Kahn et al [108], 2010 | United States, HIV clinic | Patients with HIV or AIDS | + | Pilot or feasibility | 136 | NR | 15 (11)f | 106 (78)f |

| Keith McInnes et al [109], 2013 | United States, 8 Veteran hospitals | Veterans with HIV, partly uncontrolled | + | Cross-sectional | 1871 | NR | 51 (2.73) | 342 (18.28) |

| Keith McInnes et al [110], 2017 | United States, Veterans care system | Veterans with HIV+detectable viral load, partly uncontrolled | + | Cohort | 3374 | NR | 128 (3.79) | 1130 (33.49) |

| Kiberd et al [111], 2018 | Canada, dialysis clinic | Adult with home dialysis | + | Pilot or feasibility | 41 | 57 (2) | 13 (48) | NR |

| Lee et al [112], 2017 | South Korea, 1 surgery department | Patients with cleft lip or cleft palate surgery | − | Pilot or feasibility | 50 | 36 (NR) | 33 (66) | NR |

| Miller et al [113], 2011 | United States, MSn clinic | Patients with MS | + | RCT | I=104, C=102 | 48 (9) | 73 (71.6) | 80 (78.4) |

| Navaneethanet al [114], 2017 | United States, multiple health centers | Adults with chronic kidney disease, partly uncontrolled | + | RCT | I=152, C=57 | 68 (NR)f | 79 (52) | 117 (77) |

| Plimpton [115], 2020 | United States, HIV clinic | Women with HIV, partly uncontrolled | + | Pilot or feasibility | 22 | 41 (11) | 22 (100) | 7 (32) |

| Reich et al [116], 2019 | United States, 1 community hospital | Adults with IBDo | + | RCT | I=64, C=63 | 42 (16) | 28 (46) | 48 (77) |

| Scott Nielsen et al [117], 2012 | United States, 1 academic center | Adults with MS | + | Cross-sectional | I=120, C=120 | 45 (11) | 90 (75) | 115 (95.8) |

| Son and Nahm [118], 2019 | United States, online senior community | Patients >49 years with 1 or more chronic conditions | ± | Secondary data analysis | 272 | 70 (9) | 191 (70.2) | 213 (78.3) |

| Tom et al [119], 2012 | United States, integrated health system | Parents of children age <6 years with 1 or more chronic conditions | ± | Cross-sectional | I=166, C=90 | 3 (1) | 66 (39.8) | 113 (68.1) |

| van den Heuvel et al [120], 2018 | Netherlands, 3 hospitals | Adults with bipolar disorder | + | Cross-sectional | 39 | 45 (11) | 44 (67) | NR |

| van der Vaart et al [121], 2014 | Netherlands, 1 hospital | Patients with rheumatoid arthritis | + | Cross-sectional | 214 | 62 (13) | 140 (65.4) | NR |

aAll studies are listed in Tables 2-5 and are reported in the disease category of the condition that is most prominently investigated. The study by Byczkowski et al [43] is therefore listed in Table 2.

bIf conditions are considered to have a high disease burden or demand high self-management skills, a positive sign is shown. Otherwise, a sign is indicated. A ± sign indicates that multiple diseases have been studied, and only some of the diseases were considered to have a high disease burden.

cIf available, age (years), gender, and race were reported by digital health record users (“the intervention group”).

dMSM: men who have sex with men.

eRCT: randomized controlled trial.

fPresented numbers were estimated based on the data provided in the original articles.

gIBD: inflammatory bowel disease.

hNR: not reported.

iI: intervention.

jC: control.

kDM: diabetes mellitus.

lHT: hypertension.

mHC: hypercholesterolemia.

nMS: multiple sclerosis.

oIBD: inflammatory bowel disease.

Table 3.

Study characteristics of studies investigating cardiopulmonary diseases (of 21 studies investigating cardiopulmonary diseases, 11 are listed in Table 3).a

| Author, year | Country, setting | Study population, disease, controlled? | Burdenb | Study design | Sample size | Age (years)c, mean (SD) | Genderc (female), n (%) | Racec (White), n (%) |

| Aberger et al [78], 2014 | United States, renal transplant clinic | Postrenal transplant patients with HTd | + | Pilot or feasibility | 66 | 54 (NRe) | 34 (52)f | 48 (72)f |

| Ahmed et al [79], 2016 | Canada, 2 academic hospitals | Adults with asthma using medication | + | RCTg | Ih=49, Ci=51 | NR | 32 (68) | NR |

| Apter et al [80], 2019 | United States, multicenter hospitals | Adults with asthma using prednisone | + | RCT | I=151, C=150 | 49 (13) | 270 (89.7) | 4 (1.3) |

| Fiks et al [81], 2015 | United States, 3 PCPsj | Children aged 6-12 years with asthma, partly uncontrolled | + | RCT | I=30, C=30 | 8.3 (1.9) | 26 (87) among parents | 13 (43) |

| Fiks et al [82], 2016 | United States, 20 PCPs | Children aged 6-12 years with asthma, partly uncontrolled | + | Pilot or feasibility | I=237, C=8896 | NR | 101 (42.8) | 144 (61.5) |

| Kogut et al [83], 2014 | United States, 1 community hospital | Adults aged >49 years with cardiopulmonary disorders | ± | Pilot or feasibility | 30 | NR | 14 (47) | NR |

| Kim et al [84], 2019 | South Korea, 1 academic hospital | Patients with obstructive sleep apnea | − | RCT | I=30, C=13 | 43 (10)f | NR (15) | NR |

| Lau et al [85], 2015 | Australia, nationwide | Adults with asthma | + | RCT | I=154, C=176 | 40 (14) | 124 (80.5) | NR |

| Manard et al [86], 2016 | United States, PCP registry | Adults with uncontrolled HT | − | Cohort | I=400, C=1171 | 61 (12) | 262 (65.5) | 72 |

| Toscos et al [87], 2020 | United States, 1 community hospital | Patients with nonvalvular AFk with OACl | + | RCT | I=76, C=77 | 71 (9) | 60 (37.5) | 153 (99.4) |

| Wagner et al [88], 2012 | United States, 24 PCPs | Patients with hypertension, partly uncontrolled | − | RCT | I=193, C=250 | 55 (12) | 145 (75.1) | 96 (50.5) |

aAll studies are listed in Tables 2-5 and are reported in the disease category of the condition that is most prominently investigated. The studies by Price-Haywood and Luo [56], Price-Haywood et al [57], Reed et al [59], Reed et al [60], Reed et al [61], Riippa et al [62], Riippa et al [63], Shimada et al [71] are listed in Table 2. The study by Martinez Nicolás et al [89] is listed in Table 4. The study by Druss et al [77] is therefore listed in Table 5.

bIf conditions are considered to have a high disease burden or demand high self-management skills, a positive sign is shown. Otherwise, a sign is indicated. A ± sign indicates that multiple diseases have been studied, and only some of the diseases were considered to have a high disease burden.

cIf available, age (years), gender, and race were reported by digital health record users (“the intervention group”).

dHT: hypertension.

eNR: not reported.

fPresented numbers were estimated based on the data provided in the original articles.

gRCT: randomized controlled trial.

hI: intervention.

iC: control.

jPCP: primary care practice.

kAF: atrial fibrillation.

lOAC: oral anticoagulant drug.

Table 4.

Study characteristics of studies investigating hematological and oncological diseases (n=14).

| Author, year | Country, setting | Study population, disease, controlled? | Burdena | Study design | Sample size | Age (years)b, mean (SD) | Genderb (female), n (%) | Racec (White), n (%) |

| Cahill et al [90], 2014 | United States, cancer center | Adults with glioma | + | Cross-sectional | 186 | 44 (13) | 87 (46.8) | 149 (86.1) |

| Chiche et al [91], 2012 | France, 1 community hospital | Adults with ITPc | ± | RCTd | Ie=28, Cf=15 | 48 (15)g | 21 (75) | NRh |

| Collins et al [92], 2003 | United Kingdom, hemophilia centers | Patients with hemophilia >11 years | + | Pilot or feasibility | 10 | NR | NR | NR |

| Coquet et al [93], 2020 | United States, cancer center | Patients with cancer+chemotherapy | + | Cohort | I=3223, C=3223 | 59 (15) | 1,554 (49.78) | 1,804 (49.68) |

| Groen et al [94], 2017 | Netherlands, cancer center | Patients with lung cancer | + | Pilot or feasibility | 37 | 60 (8) | 16 (47) | 37 (100) |

| Hall et al [95],2014 | United States, Cancer Center | Patients with resection for CRCi or ECj | + | Pilot or feasibility | 49 | 59 (12)g | 37 (76) | 48 (98) |

| Hong et al [96], 2016 | United States, academic pediatric hospital | Children aged 13-17 years with cancer or a blood disorder+parents | + | Cross-sectional | 46 | 15 (1.2)g | 10 (63) among children | NR |

| Kidwell et al [97], 2019 | United States, multicenter hospitals | Patients aged 13-24 years with sickle cell disease | + | Pilot or feasibility | 44 | 19 (NR) | 24 (55) | 0 (0) |

| Martinez Nicolás et al [89], 2019 | Spain, 4 community hospitals | Patients with COPDk, CHFl, or hematologic malignancy | + | Pilot or feasibility | 577,121 | 42 (23) | 319,725g (55) | NR |

| O’Hea et al [98], 2021 | United States, cancer centers | Adult women with nonmetastatic breast cancer ending treatment | + | RCT | I=100, C=100 | 61 (11) | 100 (100) | 85 (85) |

| Pai et al [99], 2013 | Canada, cancer center | Adult men with prostate cancer | + | Cross-sectional | 17 | 64 (7)g | 0 (0) | 16 (95) |

| Tarver et al [100], 2019 | United States, academic hospital | Patients with colorectal cancer | + | Cross-sectional | 22 | 58 (10) | 10 (45) | NR |

| Wiljer et al [101], 2010 | Canada, breast cancer registry | Patients with breast cancer | + | Pilot or feasibility | 311 | NR | 303 (99.7) | NR |

| Williamson et al [102], 2017 | United States, pediatric cancer center | Pediatric cancer survivors | + | Cohort | 56 | NR | 27 (48) | 49 (88) |

aIf conditions are considered to have a high disease burden or demand high self-management skills, a positive sign is shown. Otherwise, a sign is indicated. A ± sign indicates that multiple diseases have been studied, and only some of the diseases were considered to have a high disease burden.

bIf available, age (years), gender, and race were reported by digital health record users (“the intervention group”).

cITP: idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura.

dRCT: randomized controlled trial.

eI: intervention.

fC: control.

gPresented numbers were estimated based on the data provided in the original articles.

hNR: not reported.

iCRC: colorectal cancer.

jEC: endometrial cancer.

kCOPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

lCHF: congestive heart failure.

Explanations of the patient-centered digital health records investigated in each study are presented in Tables 6-9. Patient-centered digital health records range from a pilot patient portal enabling patients to view a limited set of their medical data to comprehensive PHRs, offering extensive data access and enabling appointment scheduling and prescription refill requests. A minority (12/81, 15%) of studies specifically evaluated ≥1 digital health record features such as secure messaging or a medication adherence module. In addition, 15% (12/81) of studies used a hybrid approach to assess a combination of a digital health record with a connected device, or with training, coaching, or face-to-face visits.

Table 6.

Patient-centered digital health record descriptions for disease category diabetes mellitus (of 37 studies investigating diabetes mellitus, 36 are listed in Table 6).a

| Author, year | Name | Type | What is evaluated?b | Passive features | Active features | Focusc | ||||||

| Bailey et al [41], 2019 | Electronic Medication Complete Communication | PPd | Adherence module alone | View health information (medical summary), read after-visit summary, read educational material | Report medication concerns, monitor medication use | Active | ||||||

| Boogerd et al [42], 2017 | Sugarspace | PP | PP | View treatment goals, read educational material | Parent-professional communication, peer support | Active | ||||||

| Byczkowski et al [43], 2014 | In-house developed | PP | PP | View health information (including laboratory results, medication), view appointments, read disease-specific information | Messaging, upload documents, receive reminders | Passive | ||||||

| Chung et al [44], 2017 | Not reported | PP | Messaging | View health information | Messaging | Active | ||||||

| Conway et al [45], 2019 | My Diabetes My Way | Tethered PHRe | PHR | View health information from primary and secondary care (including clinical parameters, medication, and correspondence), read educational material | Report self-measurements | Passive | ||||||

| Devkota et al [46], 2016 | MyChart | PP | PP | View health information (including laboratory results, diagnoses, medication, vital signs), read educational material | Messaging, request prescription refills, schedule appointments, pay bills | Passive | ||||||

| Dixon et al [47], 2016 | CareWeb | PP | Medication module alone | View health information (including measurements, medication) | Report barriers to medication adherence | Passive | ||||||

| Graetz et al [48], 2018 and Graetz et al [49], 2020 | “Kaiser Permanente portal” | PP | PP | View health information (including laboratory results) | Messaging, schedule appointments, request prescription refills, pay bills | Active | ||||||

| Grant et al [50], 2008 | Not reported | PP | PP | View health information (including medication, laboratory results) | Edit medication lists, messaging, report adherence barriers or adverse effects | Active | ||||||

| Lau et al [121], 2014 | BCDiabetes | PP | PP | View health information (including laboratory results), view care plan, read educational material | Messaging, use a journal | Passive | ||||||

| Lyles et al [52], 2016 | “Kaiser Permanente portal” | PP | Medication module alone | View health information (including medical history, laboratory results, and visit summaries) | Messaging, schedule appointments, request prescription refills | Active | ||||||

| Martinez et al [53], 2021 | My Diabetes Care, part of My Health at Vanderbilt | PP | Diabetes module | View health information (including laboratory results and vaccinations), visualize information, read educational material | Messaging, peer support, decision support tools | Active | ||||||

| McCarrier et al [54], 2009 | Living with Diabetes Intervention | PP | PP+case manager | View health information (including correspondence, action plans, and laboratory results), read diabetes-related information | Upload blood glucose readings, use a journal | Active | ||||||

| Osborn et al [55], 2013 | My Health At Vanderbilt | PP | PP | View health information (including vital signs, laboratory results, and medication), read educational information | Messaging, manage appointments, use health screening tools, pay bills | Passive | ||||||

| Price-Haywood and Luo [56], 2017 and Price-Haywood et al [57], 2018 | MyOchsner | PP | PP | View health information (including an after-visit summary, allergies, and laboratory results) | Messaging, request prescription refills, schedule appointments | Passive | ||||||

| Quinn et al [58], 2018 | Not reported | PP | PP | View self-reported health information (including medication and measurements), read educational material | Messaging, report self-measurements and medication changes, receive automated feedback | Active | ||||||

| Reed et al [59], 2015 | “Kaiser Permanente portal” | PP | Messaging alone | View health information (including laboratory results and correspondence) | Messaging, request prescription refills, schedule appointments | Active | ||||||

| Reed et al [60], 2019 (1) and Reed et al [61], 2019 | “Kaiser Permanente portal” | PP | PP | View health information from primary care and secondary care (including laboratory results and visit summaries) | Messaging, request prescription refills, schedule visits | Passive | ||||||

| Riippa et al [62], 2014 and Riippa et al [63], 2015 | Not reported | PP | PP | View health information (including diagnoses, laboratory results, vaccinations, and medication), view care plan, read educational material | Messaging | Passive | ||||||

| Robinson et al [64], 2020 | My HealtheVet | PP | Messaging alone | View health information (including medication and correspondence), view appointments | Messaging, request prescription refills, receive reminders, upload notes and measurements, use a journal | Passive | ||||||

| Ronda et al [65], 2014 and Ronda et al [66], 2015 | Digitaal logboek | PP | PP | View diabetes-specific health information (including laboratory results, diagnoses, and medication), view treatment goals, view appointments | Messaging, upload self-measurements | Passive | ||||||

| Sabo et al [67], 2021 | Diabetes Engagement and Activation Platform | PP | PP | View health information (including medication and self-reported glucose measurements) | Report diet, physical activity, blood glucose measurements, complications, mental health and goals, receive alerts | Active | ||||||

| Sarkar et al [68], 2014 | “Kaiser Permanente portal” | PP | PP | View health information (including medical history, laboratory results, and visit summaries), view appointments | Messaging, request prescription refills | Passive | ||||||

| Seo et al [69], 2020 | My Chart in My Hand | Tethered PHR | PHR+sugar function | View health information (including laboratory results, medication, allergies, diagnoses) | Edit information, schedule appointment; sugar function: log treatment, food intake, and exercise | Active | ||||||

| Sharit et al [70], 2018 | My HealtheVet | PP | Track Health module+wearable | View health information (including medication and correspondence), view appointments | Messaging, request prescription refills, receive reminders; track Health module: record diet and activity, upload data from connected accelerometer | Active | ||||||

| Shimada et al [71], 2016 | My HealtheVet | PP | Messaging, prescription refills | View health information (including medication and correspondence), view appointments | Messaging, request prescription refills, receive reminders, upload notes and self-measurements, use a journal | Active | ||||||

| Tenforde et al [72], 2012 | MyChart | PP | PP | View health information (including diagnoses and laboratory results), read diabetes educational material | Messaging, view glucometer readings, receive reminders | Passive | ||||||

| van Vugt et al [73], 2016 | e-Vita | Tethered PHR | PHR+personal coach | View health information (measurements), read diabetes education | Messaging, self-management support program for personal goal setting and evaluation | Active | ||||||

| Vo et al [74], 2019 | “Kaiser Permanente portal” | PP | PP+PreVisit Prioritization messaging | View health information (including medical history, laboratory results, and visit summaries), view appointments | PreVisit Prioritization messaging to report priorities before a clinic visit, request prescription refills | Active | ||||||

| Wald et al [75], 2009 | Patient Gateway | Tethered PHR | PHR | View health information (including medication, allergies, and laboratory results) | Suggest corrections, report care concerns, ask for referrals, create care plans before visits | Active | ||||||

| Zocchi et al [76], 2021 | My HealtheVet | PP | PP | View health information (including medication, laboratory results, imaging, and correspondence) | Messaging, requesting prescription refills, download health information | Active | ||||||

aAll studies are listed once in Tables 2-5 and are reported in the disease category of the condition that is most prominently investigated. We have included only the functionalities that the authors have reported in their articles. We have applied the taxonomy as presented in Textbox 1 on the information provided by the authors. Therefore, our classification of patient-centered digital health records might not correspond with the term used by the authors.

bIn this column, we indicated whether authors evaluated the complete patient-centered digital health record, or only part of it.

cBy definition, patient-centered digital health records have both passive and active features. In this column, we indicate whether patient-centered digital health records predominantly offer passive or active features. In passive features, patients receive information but do not actively add it. In terms of active features, patients perform an action and actively engage with the portal.

dPP: patient portal.

ePHR: personal health record.

Table 9.

Patient-centered digital health record descriptions for disease category other diseases (of 21 studies investigating other diseases, 20 are listed in Table 9).a

| Author, year | Name | Type | What is evaluated?b | Passive features | Active features | Focusc | ||||||

| Anand et al [103], 2017 | Adam’s Love | PPd | PP | View health information (HIV test results), receive appointment reminders | Schedule HIV test appointments, use e-counseling, receive appointment reminders | Active | ||||||

| Bidmead et al [104], 2016 | Patients Know Best | Tethered PHRe | PHR | View health information (including medication, laboratory results, and correspondence), read educational material | Communication with health care providers, upload and share health information | Active | ||||||

| Crouch et al [105], 2015 | My HealtheVet | PP | PP | View health information (including laboratory results and correspondence) | Messaging, request prescription refills | Passive | ||||||

| Druss et al [106], 2014 | MyHealthRecord | PP | PP+training | View health information (including diagnoses, measurements, laboratory results, medication, and allergies), view treatment goals | Prompts remind patients of routine preventive service | Passive | ||||||

| Druss et al [77], 2020 | Not reported | PP | PP+training | View health information (including medication, allergies, measurements, and laboratory results) | Formulate long-term goals, that are translated into action plans with progress tracking | Active | ||||||

| Jhamb et al [107], 2015 | Not reported | PP | PP | View health information (including diagnoses, allergies, immunizations, and laboratory results) | Messaging, schedule appointments, request prescription refills | Passive | ||||||

| Kahn et al [108], 2010 | MyHERO | PP | PP | View health information (including diagnoses, medication, laboratory results, and allergies), view appointments, read information on interpreting test results | Upload notes and self-measurements | Passive | ||||||

| Keith McInnes et al [109], 2013 and Keith McInnes et al [110], 2017 | My HealtheVet | PP | PP | View health information (including medication and correspondence), view appointments | Messaging, request prescription refills, receive reminders, upload notes and self-measurements, use a journal | Passive | ||||||

| Kiberd et al [111], 2018 | RelayHealth | PP | PP | View health information (including test results and medication) | Messaging | Active | ||||||

| Lee et al [112], 2017 | CoPHR | PP | PP | View health information (including diagnoses, laboratory results, medication, allergies, vital signs, and correspondence), view appointments, view treatment plan, read educational information | Manage and edit appointments and health information | Passive | ||||||

| Miller et al [113], 2011 | Mellen Center Care Online | Untethered PHR | PHR | Review previously entered symptoms and HRQoLf | Messaging, report symptoms and HRQoL and evaluate changes, preparation for appointments | Active | ||||||

| Navaneethan et al [114], 2017 | MyChart | PP | PP+part of users received training | View health information (including medication and laboratory results), read educational material | Messaging, schedule appointments, request prescription refills | Passive | ||||||

| Plimpton [115] 2020 | Not reported | PP | PP | View health information | Messaging | Passive | ||||||

| Reich et al [116], 2019 | MyChart | PP | PP | View health information (including laboratory results, diagnoses, medication, and vital signs) | Messaging | Passive | ||||||

| Scott Nielsen et al [117], 2012 | PatientSite10 | PP | PP | View health information (including laboratory results, and imaging), read educational material | Messaging, schedule appointments, request prescription refills, upload self-measurements, pay bills | Active | ||||||

| Son and Nahm [118], 2019 | MyChart | PP | PP+training | View health information (including medication and laboratory results), read educational material | Messaging, schedule appointments, request prescription refills | Passive | ||||||

| Tom et al [119], 2012 | MyGroupHealth | PP | PP | View health information (including diagnoses, medication, and test results), read after-visit summaries, proxy access | Messaging, schedule appointments | Passive | ||||||

| van den Heuvel et al [120], 2018 | “PHR-BD” | Tethered PHR | Tethered PHR+mood chart | View health information (including diagnoses, laboratory results, medication, and correspondence), read educational material | Messaging, report symptoms in a mood chart, view personal crisis plan | Active | ||||||

| van der Vaart et al [121], 2014 | Not reported | PP | PP | View health information (including diagnoses, medication, and laboratory results), read educational material | Report and monitor HRQoL outcomes | Active | ||||||

aAll studies are listed once in Tables 2-5 and are reported in the disease category of the condition that is most prominently investigated. We have included only the functionalities that the authors have reported in their articles. We have applied the taxonomy as presented in Textbox 1 on the information provided by the authors. Therefore, our classification of patient-centered digital health records might not correspond with the term used by the authors.

bIn this column, we indicated whether authors evaluated the complete patient-centered digital health record, or only part of it.

cBy definition, patient-centered digital health records have both passive and active features. In this column, we indicate whether patient-centered digital health records predominantly offer passive or active features. In passive features, patients receive information but do not actively add it. In terms of active features, patients perform an action and actively engage with the portal.

dPP: patient portal.

ePHR: personal health record.

fHRQoL: health-related quality of life.

Table 7.

Patient-centered digital health record descriptions for disease category cardiopulmonary diseases (of 21 studies investigating cardiopulmonary diseases, 11 are listed in Table 7).a

| Author, year | Name | Type | What is evaluated?b | Passive features | Active features | Focusc | ||||||

| Aberger et al [78], 2014 | Good Health Gateway | PPd | PP+BPe cuff | View BP measurements, view treatment goals | Communicate self-reported adherence, receive automated and tailored feedback | Active | ||||||

| Ahmed et al [79], 2016 | My Asthma Portal | PP | PP | View health information (including medication and diagnoses), read general and tailored asthma information | Monitor and receive feedback on self-management practices | Passive | ||||||

| Apter et al [80], 2019 | MyChart | PP | PP | View health information (including laboratory results, vaccinations, and medication), view appointments | Messaging, request prescription refills, schedule appointments | Passive | ||||||

| Fiks et al [81], 2015 and Fiks et al [82], 2016 | MyAsthma | PP | PP | View care plan, read educational material | Report symptoms, treatment adherence, concerns and side effects | Active | ||||||

| Kim et al [84], 2019 | MyHealthKeeper | Tethered PHRf | PHR+activity tracker | View previously uploaded self-reported data | Upload self-reported data (eg, diet, sleep, weight, BP, step count), connect with wearables, receive feedback from health care providers | Active | ||||||

| Kogut et al [83], 2014 | ER-Card | Untethered PHR | PHR+home visits by pharmacists | View patient-reported medication list | Pharmacists view and review patient-reported medication lists, and discuss potential concerns in home visits | Active | ||||||

| Lau et al [85], 2015 | Healthy.me | Untethered PHR | PP+extra feature | View Asthma Action Plan, read educational content | Schedule appointments, peer support, self-report medication, use a journal | Passive | ||||||

| Manard et al [86], 2016 | Not reported | PP | PP+BP cuff | View health information (including laboratory results, vital signs, and diagnoses) | Messaging, request prescription refills, upload measurements from connected BP cuff | Passive | ||||||

| Toscos et al [87], 2020 | MyChart | PP | PP+smart pill bottle | View health information (including laboratory results, vaccinations, and medication), view appointments | Messaging, request prescription refills, schedule appointments Smart Pill Bottle: a device that sends notifications when a user opens or fails to open the lid, based on the dose schedule | Active | ||||||

| Wagner et al, 2012 [88] | MyHealthLink | Tethered PHR | PHR | View health information (including diagnoses, medication, and allergies), read educational material | Messaging, goal setting, upload self-measurements (including BP) | Active | ||||||

aAll studies are listed once in Tables 2-5 and are reported in the disease category of the condition that is most prominently investigated. We have included only the functionalities that the authors have reported in their articles. We have applied the taxonomy as presented in Textbox 1 on the information provided by the authors. Therefore, our classification of patient-centered digital health records might not correspond with the term used by the authors.

bIn this column, we indicated whether authors evaluated the complete patient-centered digital health record, or only part of it.

cBy definition, patient-centered digital health records have both passive and active features. In this column, we indicate whether patient-centered digital health records predominantly offer passive or active features. In passive features, patients receive information but do not actively add it. In terms of active features, patients perform an action and actively engage with the portal.

dPP: patient portal.

eBP: blood pressure.

fPHR: personal health record.

Table 8.

Patient-centered digital health record descriptions for disease category hematological and oncological diseases (n=14).a

| Author, year | Name | Type | What is evaluated?b | Passive features | Active features | Focusc | ||||||

| Cahill et al [90], 2014 | MyMDAnderson | Tethered PHRd | PHR | View health information (including correspondence, operative reports, laboratory results, and imaging), read education material | Messaging, request prescription refills, schedule appointments | Passive | ||||||

| Chiche et al [91], 2012 | Sanoia | PPe | PP+ITPf features | View health information (including allergies, vaccinations, medication, and test results), ITP-specific educational material, read emergency protocols | Messaging | Passive | ||||||

| Collins et al [92], 2003 | Advoy | PP | PP | View health information (treatment regimen), read educational material | Registration of symptoms and medication use, automated alerts are sent to professionals | Active | ||||||

| Coquet et al [93], 2020 | MyHealth portal | PP | Email use | View health information (including laboratory results) | Messaging, schedule appointments, request prescription refills, pay bills | Active | ||||||

| Groen et al [94], 2017 | MyAVL | PP | PP | View health information (including laboratory results, lung function, and correspondence), view appointments, read personalized information | Upload patient-reported outcomes, receive tailored physical activity advice | Active | ||||||

| Hall et al [95], 2014 | MyFoxChase | PP | Genetic screening | View health information (including laboratory results), view appointments, read educational material | Messaging, receive alerts if genetic screening results are available | Passive | ||||||

| Hong et al [96], 2016 | MyChart | PP | PP | View health information (including laboratory results, medication, allergies) | Messaging, schedule appointments, request prescription refills, use a journal | Passive | ||||||

| Kidwell et al [97], 2019 | MyChart | PP | PP | View health information (including laboratory results, medication, diagnoses, and allergies), view appointments, read information about sickle cell disease | Messaging | Passive | ||||||

| Martinez Nicolás et al [89], 2019 | Not reported | PP | PP | View health information (including laboratory results, imaging, and medication) | Messaging, teleconsulting, schedule appointments, upload glucose measurements | Active | ||||||

| O’Hea et al [98], 2021 | Polaris Oncology Survivorship Transition | PP | PP | View health information (including diagnoses, operative reports, and medication), view appointments, read educational material | Request a referral | Passive | ||||||

| Pai et al [99], 2013 | PROVIDER | Tethered PHR | PHR | View health information (including laboratory results, medication, pathology, imaging, and correspondence), read educational material | Messaging, use decision support tools, fill in questionnaires | Passive | ||||||

| Tarver et al [100], 2019 | OpenMRS | Tethered PHR | PHR+extra feature | View health information (including treatment history, diagnoses, and care plan), view a treatment summary, read educational material | Messaging, peer support | Passive | ||||||

| Wiljer et al [101], 2010 | InfoWell | Tethered PHR | PHR | View health information (including medication, laboratory results, imaging, and pathology), view appointments | Patients can organize and upload care information | Passive | ||||||

| Williamson et al [102], 2017 | SurvivorLink | Untethered PHR | PHR | Read educational material | Upload health documents and share these with professionals | Active | ||||||

aAll studies are listed once in Tables 2-5 and are reported in the disease category of the condition that is most prominently investigated. We have included only the functionalities that the authors have reported in their articles. We have applied the taxonomy as presented in Textbox 1 on the information provided by the authors. Therefore, our classification of patient-centered digital health records might not correspond with the term used by the authors.

bIn this column, we indicated whether authors evaluated the complete patient-centered digital health record, or only part of it.

cBy definition, patient-centered digital health records have both passive and active features. In this column, we indicate whether patient-centered digital health records predominantly offer passive or active features. In passive features, patients receive information but do not actively add it. In terms of active features, patients perform an action and actively engage with the portal.

dPHR: personal health record.

ePP: patient portal.

fITP: idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura.

Outcomes

An overview of reported associations for each health outcome is shown in Figure 2. The proportions of beneficial effects reported per health outcome are presented in Multimedia Appendices 3 and 4. For high-quality studies, proportions are presented in Multimedia Appendix 3. An overview of study conclusions and associated outcomes is presented in Tables 10-13. Studies were grouped according to disease group.

Figure 2.

Health outcomes associated with patient-centered digital health record use. Associations refer to meaningful clinical effects or statistical significance. If studies report multiple health outcome within 1 category, each health outcome is included separately. *The proportion of health outcomes for which beneficial effects were reported. ED: emergency department.

Table 10.

Conclusions and health outcomes: all studies investigating diabetes (n=37), of which 8 (22%) are of high methodological quality.a

| Author, year | Participants | Comparison | Main conclusion | Study design | Clinical | Patient reported | Care utilization | Technology | Qualityb |

| Boogerd et al [42], 2017 | Parents of children with DMc type 1 | PPd users versus PP nonusers | Patient portal use is not associated with less parental stress. The more stress, the more parents use the portal. | QEe |

|

|

—f |

|

|

| Lau et al [51], 2014 | Patients with DM | Pretest PP nonuse versus posttest PP use | Patient portal use is associated with improved glycemic control. | Cohort |

|

— | — | — |

|

| Lyles et al [52], 2016 | Adults with DM type 2 using statins, registered for PP | Prescription refill use versus no refill use | Requesting prescription refills is associated with improved statin adherence. | Cohort | — |

|

— | — |

|

| McCarrier et al [54], 2009 | Adults aged <50 years with uncontrolled DM type 1 | Nurse-aided PP users versus PP nonusers | Patient portal use results in improved self-efficacy, but not in improved glycemic control. | RCTg |

|

|

— |

|

|

| Price-Haywood and Luo [56], 2017 | Adults with DM (or HTh) | PP users versus PP nonusers | Patient portal use is associated with more primary care visits and telephone encounters, but not with less hospitalizations or EDi visits. | Cohort |

|

— |

|

— |

|

| Sarkar et al [68], 2014 | Adults with DM, registered for PP | Recurrent prescription refill use versus occasional refill use versus no refill use | Recurrent use of prescription refills is associated with improvements in adherence and lipid control. | Cohort |

|

— | — | — |

|

| Shimada et al [71], 2016 | Veterans with uncontrolled DM, registered for PP | Messaging and prescription refills users versus PP users who use neither | Messaging or requesting prescription refills is associated with improved glycemic control. | Cohort |

|

— | — | — |

|

| van Vugt et al [73], 2016 | Patients with DM type 2, registered for PHRj | PHR+personal coach versus PHR use alone | PHR use does not result in improved glycemic control, self-care, distress, nor well-being, regardless of personal coaching. | RCT |

|

|

— |

|

|

| Dixon et al [47], 2016 | Adults with DM type 2 | Pretest PP nonusers versus posttest PP users | Patient portal use is associated with improved adherence, but not with changes in clinical outcomes nor care utilization. | QE |

|

|

|

— |

|

| Druss et al [77], 2020 | Patients with a mental disorder+DM, HT or HCk | PP users versus PP nonusers | Patient portal use does not result in clinically relevant improvements in perceived quality of care, patient activation nor HRQoLl. | RCT |

|

|

|

— |

|

| Graetz et al [49], 2020 | Adults with DM with at least 1 oral drug | PP users versus PP nonusers | Patient portal use is associated with small, likely irrelevant improvements in glycemic control and medication adherence. | Cross |

|

|

— | — |

|

| Grant et al [50], 2008 | Adults with DM using medication | Tethered PP use versus untethered PP use | Using a tethered patient portal results in increased patient participation, but not improved glycemic control. | RCT |

|

|

— | — |

|

| Reed et al [60], 2019 | Adults with DM+HT, asthma, CADm, or CHFn | PP users versus PP nonusers | Patient portal use is associated with more outpatient office visits, and with reduced ED visits and preventable hospitalizations. | Cross |

|

— |

|

— |

|

| Riippa et al [62], 2014 | Adults with DM, HT, or HC | PP users versus PP nonusers | Patient portal use does not result in clinically relevant improvements in patient activation, except among adults with low baseline activation. | RCT | — |

|

— | — |

|

| Riippa et al [63], 2015 | Adults with DM, HT, or HC | PP users versus PP nonusers | Patient portal use does not result in clinically relevant improvement in patient activation nor HRQoL. | RCT | — |

|

|

|

|

| Robinsonet al [64], 2020 | Veterans with uncontrolled DM type 2, registered for PP | Responders on team-initiated messages versus nonresponders | Responding on messages is associated with improved self-management and self-efficacy. | Cross | — |

|

— | — |

|

| Ronda et al [65], 2014 | Adults with DM | Recurrent PP users versus PP nonusers | Recurrent patient portal use is associated with better self-efficacy and knowledge. | Cross | — |

|

— |

|

|

| Ronda et al [66], 2015 | Adults with DM, registered for PP | Persistent users versus early quitters | Recurrent users believe the patient portal increases disease knowledge, and they find it useful. | Cross | — |

|

— |

|

|

| Sabo et al [67], 2021 | Adults with DM type 2, registered for PP | PP users versus PP nonusers | Patient portal use has minor, clinically irrelevant effects on BMI, and no effects on glycemic control nor blood pressure. | RCT |

|

— | — | — |

|

| Seo et al [69], 2020 | Patients with DM, registered for PHR | Continuous users versus noncontinuous users | Continuous use of a tethered PHR is associated with slightly improved glycemic control. Clinical implications are doubtful. | Cohort |

|

— | — | — |

|

| Sharit et al [70], 2018 | Overweight veterans with prediabetes | Pretest PP nonuse versus posttest PP use | Using an accelerometer-connected patient portal is associated with improvements in physical activity and blood pressure. | QE |

|

|

— |

|

|

| Tenforde et al [72], 2012 | Adults aged <75 years with DM | PP users versus PP nonusers | Patient portal use is associated with slightly improved diabetes control, lipid profile, and blood pressure. Clinical implications are doubtful. | Cohort |

|

— |

|

— |

|

| Vo et al [74], 2019 | Adults aged <80 years with DM type 2, registered for PP | Previsit message use versus no previsit message use | Sending previsit prioritization messages does not result in improved glycemic control, but does result in improved perceived shared-decision-making. | RCT |

|

|

— | — |

|

| Zocchi et al [76], 2021 | Patients with DM type 2, registered for PP | PP users | Among existing patient portal users with uncontrolled DM or high LDLo, increased use is associated with improved control. | Cohort |

|

— | — | — |

|

| Bailey et al [41], 2019 | Adults with DM, on high-risk medication | PP users | Patients are satisfied with the patient portal. | QE | — | — | — |

|

|

| Byczkowski et al [43], 2014 | Parents of children with DM (or CFp or JIAq) | PP users | Patients consider the patient portal to be useful in managing and understand their child’s disease. | Cross | — |

|

— |

|

|

| Chung et al [44], 2017 | Adults with DM, registered for PP | Message users versus message nonusers | Using secure messaging is associated with better glycemic control. | Cohort |

|

|

|

— |

|

| Conway et al [45], 2019 | Patients with DM, registered for PP | PP users | Patients believe the tethered diabetes PHR might improve their diabetes self-care. | Cross | — |

|

— |

|

|

| Devkota et al [46], 2016 | Patients with DM type 2 | PP users who read and write emails versus PP nonusers | Reading and writing emails is associated with improved glycemic control. | Cohort |

|

|

— | — |

|

| Graetz et al [48], 2018 | Adults with DM | PP users versus PP nonusers | Patient portal use is associated with improved adherence to medication and preventive care utilization. | Cross | — |

|

|

— |

|

| Martinez et al [53], 2021 | Adults with DM type 2 using medication, registered for PP | Pretest PP nonuse versus posttest PP use | Patient portal use results in clinically not relevant improvements in patient activation and self-efficacy. This is related to the very short follow-up period of the study. | QE | — |

|

— |

|

|

| Osborn et al [55], 2013 | Adults with DM type 2 using medication | PP users versus PP nonusers | Patient portal use is not associated with improved glycemic control, as compared with nonusers. However, among users, more frequent use is associated with improved glycemic control. | Cross |

|

— | — | — |

|

| Price-Haywood et al [57], 2018 | Adults with DM (or HT) | PP users versus PP nonusers | Messaging is associated with improved glycemic control. | Cohort |

|

— | — | — |

|

| Quinn et al [58], 2018 | Adults aged <65 years with DM type 2 | PP+extra module users versus PP users | Messaging is associated with better glycemic control. Note: glycemic parameters were predicted and not represent measurements. | RCT |

|

|

|||

| Reed et al [59], 2015 | Adults with DM, HT, asthma, CAD, or CHF, registered for PP | PP users | One-third of patients report that messaging in a patient portal results in less health care visits and improved overall health. | Cross | — |

|

|

— |

|

| Reed et al [61], 2019 | Adults with DM, asthma, HT, CAD, CHF, or CVr event risk | PP users versus PP nonusers | One-third of patients report that using the patient portal improves overall health. | Cross | — |

|

— |

|

|

| Wald et al [75], 2009 | Patients with DM type 2 | PHR users who created a previsit plan | Users who create a previsit care plan feel better prepared for visits. | RCT | — |

|

— |

|

|

aStudies are listed multiple times in Tables 10-13. Per disease category, the relevant subconclusion and health outcomes are described. Associations with health outcomes are color-coded as green for beneficial, yellow for neutral or clinically nonrelevant, or red for undesired. The half green and half yellow symbol implies that one study investigated multiple outcomes in one category and reported beneficial associations for some outcomes and neutral associations for others.

bQuality appraisal—green: high quality; yellow: medium quality; red: low quality.

cDM: diabetes mellitus.

dPP: patient portal.

eQE: quasi-experimental, including pretest-posttest studies and feasibility studies.

fThe study did not assess any health outcome in a certain category.

gRCT: randomized controlled trial.

hHT: hypertension.

iED: emergency department.

jPHR: personal health record.

kHC: hypercholesteremia.

lHRQoL: health-related quality of life.

mCAD: coronary artery disease.

nCHF: congestive heart failure.

oLDL: low-density lipoprotein.

pCF: cystic fibrosis.

qJIA: juvenile idiopathic arthritis.

rCV: cardiovascular.

Table 13.

Conclusions and health outcomes: studies investigating other diseases (n=21), of which 2 (10%) are of high methodological quality.a

| Author, year | Participants | Comparison | Conclusion | Study design | Clinical | Patient reported | Care utilization | Technology | Qualityb |

| Miller et al [113], 2011 | Patients with multiple sclerosis | PHRc use versus PHR that only enables messaging | Using an untethered PHR results in slightly improved HRQoLd, but not in improved self-efficacy, disease control nor health care utilization. | RCTe | — |

|

|

—f |

|