Abstract

Lung diseases continue to draw considerable attention from biomedical and public health care agencies. The lung with the largest epithelial surface area is continuously exposed to the external environment during exchanging gas. Therefore, the chances of respiratory disorders and lung infections are overgrowing. This review has covered promising and opportunistic etiologic agents responsible for lung infections. These pathogens infect the lungs either directly or indirectly. However, it is difficult to intervene in lung diseases using available oral or parenteral antimicrobial formulations. Many pieces of research have been done in the last two decades to improve inhalable antimicrobial formulations. However, very few have been approved for human use. This review article discusses the approved inhalable antimicrobial agents (AMAs) and identifies why pulmonary delivery is explored. Additionally, the basic anatomy of the respiratory system linked with barriers to AMA delivery has been discussed here. This review opens several new scopes for researchers to work on pulmonary medicines for specific diseases and bring more respiratory medication to market.

Keywords: Etiological agents, Antimicrobial agents, Infection, Lung, Pulmonary delivery, Barrier, Inhalable drug

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Targeting lungs through oral administration of AMAs is a big challenge.

-

•

Lung infection etiological agents are considerably higher than the effective pulmonary treatment available.

-

•

Many potential barriers are responsible for ineffective delivery of AMAs through pulmonary administration.

-

•

Extensive research is needed to bring more drugs to the market for pulmonary administration.

Etiological agents, Antimicrobial agents, Infection, Lung, Pulmonary delivery, Barrier, Inhalable drug.

1. Introduction

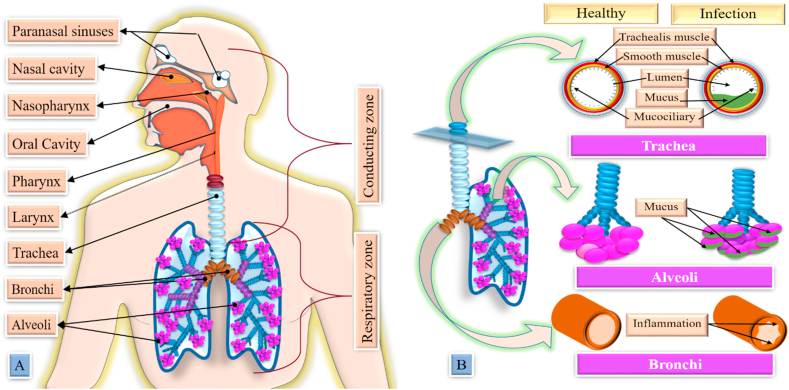

The rising incidence of lung disease has become a concern worldwide. The causative agents for these infections are bacteria, viruses, parasites, fungi, etc. Targeting antimicrobial agents (AMAs) to the lungs is essential to treat these microorganisms. However, the pulmonary route is challenging due to the nature of lung tissue. The lung has a large surface area that contains a thin epithelium layer that helps to expose AMA to lung tissue [1]. Compared to parenteral or oral administration, pulmonary delivery of AMAs poses substantial benefits for managing lower airway infections. Treating bacterial infections proves difficult due to the rapid development of drug resistance. This pulmonary delivery offers the local application of AMA to enhance drug concentrations at the infected site while minimizing systemic exposure, which leads to the development of resistance and toxicity [2]. Bypassing drug metabolism and preventing the first-pass metabolism are exciting possibilities for using the pulmonary delivery of AMA [3]. Moreover, this therapy improves patients’ compliance [4]. However, a less number of inhalable AMA formulations have reached the marketplace. This paper focuses on opportunistic etiological agents that play a vital role in lung infections and their available conventional treatments. In response to this enormous burden of respiratory diseases and causative agents, very few AMAs have been approved for pulmonary delivery, which has been discussed here. This paper explains the anatomical barriers and challenges AMAs face in the respiratory tract to bring more pulmonary medication to market.

2. Etiological agents responsible for lung infections

There are numerous causing agents (Figure 1) accountable for lung infections. The disease initiation involves direct or thorough travel to the lungs from the infection site.

Figure 1.

Different types of etiological agents are responsible for lung disease. Bacteria, fungi, parasites, and viruses are the main causative agents for lung infections. Four gram-positive bacteria, thirteen gram-negative bacteria, and two acid-fast staining bacteria cause lung infections. Ten fungal microorganisms and fourteen parasites have been identified in lung infection. Last but not least, twelve viruses are shorted here, which are found to be responsible for lung infections. The red ink highlighted organisms show a higher incidence of lung infections.

2.1. Gram-positive bacteria

In bacteriology, gram-positive bacteria show purple color under a microscope during Gram staining, whereas gram-negative bacteria do not. Staphylococci, Streptococci, Mycobacterium, clostridium, actinomyces, etc., are examples of gram-positive bacteria. Few bacteria cause lung infection, but the incidence is significantly high (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of lung infections causing bacteria and their management.

| Class | Organism | Characteristics | Recommended medicine |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gram-positive bacteria | Staphylococcus aureus | 1. A vital pathogen for CF 2. Colonizes mainly the mucous membranes of the anus, perineum, nose, and throat |

Cephalosporins (cefazolin), β-lactam antibiotics (oxacillin or nafcillin), glycopeptide antibiotics (vancomycin), cyclic lipopeptides (daptomycin), and lipoglycopeptide |

| MSSA | 1. The chances of MRSA increase with exposure to hospitals and antibiotic 2. Prevalence of this organism increase with all S. aureus |

Vancomycin, daptomycin, teicoplanin, telavancin, oxazolidinones, and tigecycline | |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 1. Responsible for the majority of community-acquired pneumonia 2. Significant cause of morbidity and mortality |

Amoxicillin, cephalosporins, ofloxacin and vancomycin. | |

| Bacillus anthracis | 1. Mostly used for biological warfare 2. Inhalational anthrax is denoted as the most life-threatening |

Penicillin G, linezolid and carbapenems, ciprofloxacin, Dichlorophen, oxiconazole, suloctidil, hexestrol, and bithionol | |

| Acid-fast staining bacteria | Mycobacterium tuberculosis | 1. One-third of the world population is infected with this microorganism 2. Mainly progresses in patients with impaired immunity |

Rifampicin, isoniazide, Ethambutol, pyrazinamide, Prothionamide, Ethionamide, etc. |

| Nontuberculous mycobacteria | 1. NTM are environmental microorganisms and can cause chronic lung infection 2. NTM is only dangerous to individuals with defective lung structures or immunosuppressed. |

Azithromycin or clarithromycin with rifampicin and ethambutol. Injectable amikacin or streptomycin. Rifampicin, ethambutol, isoniazid, or moxifloxacin, and injectable aminoglycoside (clarithromycin-resistant MAC) |

|

| Gram-negative bacteria | Achromobacter xylosoxidans | 1. Non-fermenting gram-negative rod that mainly causes healthcare-associated infection 2. This pathogen is widely resistant to many antibiotics and complicating treatment options |

Ceftazidime, tobramycin, and colistin, ceftazidime, carbapenems, piperacillin-tazobactam, and sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim |

| Burkholderia cepacia complex | 1. This gram-negative bacteria comprises 18 distinct species. 2. These species are less common, and their clinical associations are less well defined. |

Ceftazidime, meropenem, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, doripenem, doxycycline, minocycline, tobramycin, poly (acetyl arginyl) glucosamine, ceftazidime, and meropenem | |

| Chlamydia psittaci | 1. Transmitted to humans by any bird, and there have been rare reports of human-to-human transmission 2. Initially, replicate in respiratory epithelial cells is followed by spreading throughout the body |

Doxycycline And Tetracycline Hydrochloride | |

| Chlamydia psittaci | 1. Can infect individuals of all ages 2. It can persist in the host for months to years without showing any symptoms. |

Macrolides, tetracycline, and quinolones | |

| Francisella tularensis | 1. Inhalation of F. tularensis bacilli is responsible for the slow progression of pneumonia with a lower fatality rate. 2. This microorganism can infect many cell-like phagocytic cells, including macrophages and dendritic cells. |

Doxycycline and oral fluoroquinolone (ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, and levofloxacin) | |

| Haemophilus influenzae | 1. This organism is mainly prevalent in children and less common in adults. 2. This organism is associated with frequent exacerbations of bronchiectasis |

Dexamethasone, ceftazidime, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, fluoroquinolones, azithromycin, and amoxicillin/clavulanate. | |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 1. Accounts for a higher proportion of pneumonia acquired in hospitals. 2. This microorganism is a notable pulmonary pathogen leading to severe pneumonia and sepsis |

Third-fourth generation cephalosporin, aminoglycoside, carbapenem, polymyxin class, tigecycline, and fosfomycin | |

| Legionella pneumophila | 1. Resides in surface or drinking water and is transmitted to humans by aerosols. 2. Destructive alveolar inflammation is produced by recruiting neutrophils, monocytes, and bacterial enzymes |

β-Lactams, macrolides, rifampicin, fluoroquinolones, and omadacycline | |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | 1. This pathogen spreads from person to person by respiratory droplets. 2, It produces hydrogen peroxides and superoxide, damaging respiratory epithelial cells. |

macrolides, tetracycline, streptogramins, fluoroquinolones, omadacycline, lefamulin, nafithromycin, zoliflodacin, and solithromycin | |

| Moraxella catarrhalis | 1. The bacteria are transmitted exclusively between humans by direct and indirect contact. 2. It causes both upper (children) and lower (adult) respiratory tract infection |

Ampicillin, penicillin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, azithromycin, clarithromycin, extended-spectrum cephalosporin, tetracycline, trimethoprim-sulfa, and fluoroquinolones | |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | 1. This microorganism interrupts lower and upper airway homeostasis by damaging the epithelium cells. 2. No adequate remedy has been developed yet to manage this microorganism |

carbapenems (meropenem, imipenem), aminoglycosides (tobramycin, netilmicin, gentamicin, amikacin), fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin), cephalosporins (cefepime, ceftazidime), β-lactam inhibitors (piperacillin, ticarcillin), polymyxins (polymyxin A and polymyxin B) and fosfomycin | |

| Stenotrophomonas maltophilia | 1. It is a multi-drug resistant microorganism associated with several infections 2. This microorganism is intrinsically and adaptively resistant to many antibiotics. |

Levofloxacin, ticarcillin-clavulanate, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, doxycycline, fluoroquinolones, minocycline, and tigecycline | |

| Yersinia pestis | 1. The infection is usually transmitted to humans through a flea bite from a flea fed on an infected rat and then on a human. 2. The disease begins with bronchiolitis and alveolitis, progressing to a lobular and eventual lobar consolidation. |

Tetracycline, streptomycin, fluoroquinolones, chloramphenicol, gentamicin, and sulphonamides |

CF-Cystic fibrosis; MSSA-Methicillin-Susceptible S. aureus; MAC- Mycobacterium avium complex.

2.1.1. Staphylococcus aureus

Staphylococcus aureus is a gram-positive microorganism recognized as an important pathogen for cystic fibrosis (CF). The role of S. aureus in CF and the appropriate clinical response to its detection is challenging. The commonness of this microorganism among pediatric CF has become a growing concern. This microorganism colonizes mainly the mucous membranes of the anus, perineum, nose, and throat. This colonization is more frequently acquired by hospitalized patients and immediate contact persons in healthcare settings. 70–90% of the general population are the transient carriers of this microorganism. Asymptomatic carriage is a major reservoir of persistent infection spreading in the community [5]. The rising incidence of S. aureus infections leads to drug resistance. S. aureus causes lower lung function, higher airway inflammation, and mortality when detected together with P. aeruginosa [6]. S. aureus in adults with CF demonstrates a lower chance of mortality, better lung function, and lower risk of exacerbation. Several studies revealed the coinfections of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa in chronic airway diseases. During infancy, S. aureus is the key colonizing bacteria in CF lungs and declines at a later age. Additionally, the chances of P. aeruginosa increase with increasing age. The competitive interaction of these two pathogens is influenced by their survival, antibiotic susceptibility, and disease propagation [7]. Therefore, S. aureus pathogenesis is either more in children or in the absence of P. aeruginosa. The pathogenesis of S. aureus may be high for specific subtypes like methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) or small-colony variants (SCVs) of S. aureus [8]. Several antibiotics are recommended for the treatment of S. aureus infection, including cephalosporins (cefazolin), β-lactam antibiotics (oxacillin or nafcillin), glycopeptide antibiotics (vancomycin), cyclic lipopeptides (daptomycin), and lipoglycopeptide.

Methicillin-Susceptible S. aureus (MSSA) is identified either by resistance to β-lactams or by the carriage of the mecA gene [9]. Its prevalence has increased simultaneously with all S. aureus and methicillin-susceptible S. aureus (MSSA). The chances of MRSA increase with exposure to hospitals and antibiotics [10]. Staphylococcal small colony variants (SCVs) are slow-growing antibiotic-resistant variants that are difficult to detect with traditional cultures. A study found CSVs associated with lower lung function and higher rates of preceding antibiotic treatment. MRSA and SCVs cause worse outcomes in patients with pre-existing diseases and higher antibiotic treatment burdens [8]. Treatment with oxacillin, cloxacillin, flucloxacillin, and nafcillin are prolonged in MSSA. However, optimum treatment therapy is still unresolved [11]. The treatment of MRSA requires early initiation of antimicrobial therapy. Vancomycin is the first choice of treatment. Daptomycin is also equally effective, but it is a costly alternative. Ceftaroline also demonstrates promising activity in MRSA. Antibiotics like teicoplanin, telavancin, oxazolidinones, and tigecycline are also recommended in single or combination. Although a wide range of antibiotics is available for treatment often fail due to poor control of foci [12].

2.1.2. Streptococcus pneumoniae

Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus) is a gram-positive bacterium. This microorganism is responsible for the majority of community-acquired pneumonia. It is a commensal microorganism in the human respiratory tract. Acute pulmonary infection is often characterized by a higher bacterial load of S. pneumoniae in the lung. A substantial influx of polymorphonuclear cells has been observed in this infection, followed by a risk of systemic spread. It is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality globally, causing more deaths than other infectious diseases [13]. After entering the lower respiratory tract initiates pneumonia by escaping the mucous defense and gradually proceeding to the alveolus [14]. Oral amoxicillin is generally recommended as a first-line antimicrobial agent. However, the course varies from five to seven days based on the illness severity. The American Thoracic Society and Disease Society of America recommend macrolide therapy for community-acquired pneumonia without having the chance of drug-resistant S. Pneumoniae. British Infection Association recommends cephalosporins and penicillin-based agents in community-acquired pneumonia. In the case of highly resistant S. pneumoniae, ofloxacin and vancomycin are used as alternatives. β-lactam with fluoroquinolone or macrolide is recommended as the first-line in intensive care unit (ICU) patients [15].

2.1.3. Bacillus anthracis

Bacillus anthracis is the agent of anthrax, a common disease of livestock. It occasionally infects humans through direct or indirect contact with the infected animal. It is the only obligate pathogen within the genus Bacillus. This microorganism is one of the most likely agents used for biological warfare as its spores are highly resilient to degradation and easy to produce. The clinical syndromes of this infection depend on the entry route of B. anthracis. Inhalational anthrax (entering through the respiratory system) is denoted as the most life-threatening form of the disease and causes severe hemorrhagic mediastinitis (inflammation of the mediastinum) [16]. This pathogen produces exotoxin and progresses to toxemia that severely compromises pulmonary function. Pulmonary parenchymal changes, serosanguineous fluid in alveolar spaces, or mononuclear cells have been detected in a few patients. The lymph node parenchyma generally is teeming with intact and fragmented gram-positive bacilli [17]. This microorganism is susceptible to many antibiotics, but early detection and management may eradicate the bacteria. Penicillin G is generally used for naturally occurring anthrax. The WHO has recommended a combination of penicillin with fluoroquinolone or macrolide in severe cases. In gastrointestinal anthrax, a combination of penicillin with an aminoglycoside is recommended [18]. Managing this microorganism is complicated due to the lack of efficient treatment. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has recommended a combination therapy of linezolid and carbapenems to treat late anthrax. In a study, meropenem or linezolid with or without ciprofloxacin could not protect from anthrax-meningitis mainly due to poor penetration to the blood-brain barrier [19]. One group of researchers screened 1586 clinically approved drugs to treat B. anthracis [20]. Dichlorophen, oxiconazole, suloctidil, hexestrol, and bithionol effectively inhibited this microorganism. These drugs have demonstrated broad-spectrum activity against gram-positive and -negative bacterial strains. Out of which, hexestrol exhibits superior inhibition across all strains.

2.2. Acid-fast staining bacteria

These bacteria undergo staining but resist decolorization by acids. Acid fastness is the inherent property of this class of bacteria. Acid-fast staining bacteria cause tuberculosis and certain other infections (Table 1).

2.2.1. Mycobacterium tuberculosis

Tuberculosis continues to be a significant worldwide epidemic. Approximately one-third of the world population is infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis [21]. M. tuberculosis is the most lethal mycobacterial species. It is an indisputable pathogen that is accountable for many deaths worldwide. M. tuberculosis is an obligate-aerobic, non-motile, non-spore-forming, catalase-negative, and facultative intracellular bacteria. Primary tuberculosis occurs in patients without previous exposure or with the loss of acquired immunity [22]. It mainly progresses in patients with impaired immunity. The disease passes through progressive phases of exudation, recruitment of macrophages, T lymphocytes, and granuloma formation, followed by repair with granulation tissue, fibrosis, and mineralization. Secondary or reinfection-reactivation tuberculosis, referred to as post-primary tuberculosis, occurs in patients with previous immunity to the microorganism and accounts for most clinical cases of tuberculosis [23]. Most cases of active tuberculosis in adults with normal immunity progress into a latent infection, whereas reinfection with a new strain derived from the environment occurs in immunocompromised patients. The most common form of post-primary tuberculosis in adults involves the apices of the upper lobes, producing granulomatous lesions with greater caseation, often with cavities, variable degrees of fibrosis, and retraction of the parenchyma [8]. Several first-line [24] and second-line [25] drugs are available to treat tuberculosis. The World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended adopting a Directly Observed Treatment Short-course (DOTS) strategy to improve treatment adherence. In pulmonary and extra-pulmonary tuberculosis, rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol are prescribed in the intensive phase, followed by rifampicin and isoniazid in the maintenance phase. The previously reported article explains the list of drugs in different resistance cases well [26]. All these drugs are mainly available in the market in oral form. Although the lungs are the primary site of action, a tiny fraction reaches to lungs from conventional administration [27]. Therefore, there is an emerging need to deliver drugs to the lungs directly.

2.2.2. Nontuberculous mycobacteria

The incidence and number of deaths from non-tuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) disease have steadily increased globally. NTM is only dangerous to individuals with defective lung structures or immunosuppressed. NTM are now commonly infecting seemingly immune-competent children and adults at increasing rates through pulmonary infection. It is of concern as the pathology of NTM is challenging to treat and is resistant to drugs [28]. NTM are environmental microorganisms and can easily be found in soil and water that can cause chronic lung infection. The rate of NTM infection is increasing in patients with CF. This microorganism is not transmissible from person to person or reactive to latent infection like Mycobacterium tuberculosis [29]. Out of 150 identified NTM species, only a few have been reported to cause pulmonary disease. The majority (95%) of NTM isolated from CF patients is Mycobacterium avium complex (MAC) (M. intracellulare and four M. avium subspecies) and M. abscessus complex (MABSC) (subspecies abscessus, massiliense, and bolletii) [30]. In most instances, patients with NTM infection develop chronic lung disease and other risk factors, such as AIDS, alcoholism, or diabetes. Significant heterogeneity is observed in susceptibility to standard anti-TB drugs. Thus, macrolides and injectable aminoglycosides are generally prescribed for NTM disease. Despite available guidelines, the treatment is mainly empirical. In nodular or bronchiectasis MAC lung disease, combinational therapy like azithromycin or clarithromycin with rifampicin and ethambutol is recommended as initial therapy. The addition of injectable amikacin or streptomycin is included with the standard treatment. In the clarithromycin-resistant MAC case, rifampicin, ethambutol, isoniazid, or moxifloxacin, and injectable aminoglycoside are given. M. abscessus is resistant to all front-line anti-TB drugs. Thus oral macrolides with two parenteral drugs are the primary choice. According to the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) guidelines, amikacin, imipenem, or cefotaxime are used to treat M. abscessus infection.

2.3. Gram-negative bacteria

The high rate of respiratory infections is due to gram-negative bacteria, which can be found in all environments on Earth that support life. These pathogens are among the most significant public health problems in the world due to their high resistance to antibiotics (Table 1). The most common pneumonia causing microorganisms is Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Pneumonia causing a few more organisms are Chlamydia species, Francisella tularensis, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Legionella pneumophila, and Mycoplasma pneumoniae.

2.3.1. Achromobacter xylosoxidans

Achromobacter xylosoxidans is an aerobic, motile, oxidase-positive, non-fermenting gram-negative rod that mainly causes healthcare-associated infection [31]. As for P. aeruginosa and Burkholderia cepacia complex (BCC), A. xylosoxidans can be dominant and detected in CF patients at the end stage. The most clinically significant species of Achromobacter are xylosoxidans and denitrificans [32]. This pathogen is widely resistant to many antibiotics and complicating treatment options [33]. This species may cause frequent infection and is one of CF patients' most promising causes of post-lung transplant infections. Due to the lack of standard treatment for Achromobacter infections, antibiotics are given in systemic and/or inhalation. Inhalation therapy with ceftazidime, tobramycin, and colistin improved Achromobacter clearance compared to systemic treatment of these drugs in CF patients [34]. β-lactam antibiotics gave favorable clinical outcomes, including ceftazidime, carbapenems, piperacillin-tazobactam, and sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim [35].

2.3.2. Burkholderia cepacia complex

Burkholderia cepacia complex (BCC) is a group of gram-negative bacteria comprising 18 distinct species. B. cenocepacia and B. multivorans are the two most common and most common CF-associated. Often, B. gladioli are discussed with BCC because of similar infections [36]. But these species are less common, and their clinical associations are less well defined. B. cenocepacia is associated with more rapid lung function than B. multivorans. Similarly, subsequent mortality has been seen with B. cenocepacia than B. multivorans. Both are transmissible between persons with CF. The essential phenotypic modifications are the variation of the lipopolysaccharide (LPS) structure at the level of the O-antigen (OAg) presence, influencing adherence, colonization, and the ability to evade the host defense mechanisms [37]. Treatment against BCC often varies case-by-case, depending on the clinical response and susceptibility data. Ceftazidime, meropenem, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and doripenem are generally prescribed in the empiric treatment for BCC. Doxycycline and minocycline are the oral alternatives to this empiric treatment [38]. BCC can resist antibiotics and develop adverse environmental conditions that make them impossible to eradicate from CF lungs. Therefore, antimicrobial therapy is limited due to broad-spectrum antimicrobial resistance. Different drugs like tobramycin, poly (acetyl arginyl) glucosamine, ceftazidime, and meropenem with distinct mechanisms of action have been tested to treat these bacteria. It has been suggested that combining these drugs may facilitate a better way of treating BCC [39].

2.3.3. Chlamydia species

Chlamydia psittaci can be carried and transmitted to humans by any bird (pet or wild), not just by the Psittacidae family of birds, such as parrots, parakeets, and macaws. Although respiratory symptoms are usually the result of transmission from birds to humans, there have been rare reports of human-to-human transmission [40]. After inhalation, the microorganism establishes infection in the epithelial cells of the respiratory tract. Initial replication in respiratory epithelial cells is followed by the spread of bacteria throughout the body, affecting multiple organs (heart, liver, gastrointestinal tract) [41]. C. psittaci can cause morbidity with low mortality. Intentional aerosolization would lead to various cases of nonspecific “atypical pneumonia” with cough, fever, and headache [42]. Oral administration of doxycycline and tetracycline hydrochloride is effective against human psittacosis. In the contra-indicated case with tetracycline, azithromycin and erythromycin have been recommended as alternatives [43].

Chlamydia pneumoniae is a mysterious clinical pathogen that causes acute human respiratory disease. C. pneumoniae is an obligate intracellular bacterium causing respiratory infections such as acute pneumonia, bronchitis, sinusitis, and pharyngitis [44]. This disease is also known as community-acquired pneumonia and can infect individuals of all ages. 10% of community-acquired pneumonia cases are happened due to C. pneumoniae. It can penetrate mucosal epithelial cells and replicates gradually. It can be detected in atherosclerotic lesions, potentially linking the bacterium to atherosclerotic processes. However, it is not seen in undamaged vasculature [45]. It can persist in the host for months to years without showing any symptoms. C. pneumoniae can enter a non-replicative persistent state within host cells, forming morphologically aberrant inclusions. Nowadays, the reported cases of C. pneumonia are less than previously. This change is mainly influenced by changing epidemiological characteristics and newer diagnostic methods [46]. Antibiotics like macrolides, tetracycline, and quinolones treat this microorganism [47].

2.3.4. Francisella tularensis

Francisella tularensis is a pathogenic species of gram-negative coccobacillus, an anaerobic bacterium. It is non-spore-forming, non-motile, and the causative agent of tularemia, the pneumonic form of which is often lethal without treatment [48]. Inhalation of F. tularensis bacilli is responsible for the slow progression of pneumonia with a lower fatality rate than inhalation of anthrax or plague. Initially, hemorrhagic and ulcerative bronchiolitis occurs, followed by fibrinous lobular pneumonia with many macrophages. Necrosis then supervenes and evolves into a granulomatous reaction [8]. This microorganism can infect many cell types, but the primary targets appear to be phagocytic cells, including macrophages and dendritic cells (DCs). Targeting these cell types for replication and dissemination has multiple benefits for the bacteria. First, sequestration in the intracellular compartment allows the microorganism to escape exposure to numerous components present in the host serum, including complements and antibodies. Second, macrophages and DCs are pivotal cells for host defense. Macrophages kill microorganisms by invading through phagocytosis and present antigens to respond to T cells [49]. F. tularensis is classified as a category A biological warfare threatening agent. The most commonly prescribed antibiotics are doxycycline and oral fluoroquinolone (ciprofloxacin, ofloxacin, and levofloxacin). Often antibiotic therapy fails to treat this tularemia infection. The failure chances are more in fluoroquinolones than the doxycycline. Thus there is a need for effective novel treatments for F. tularensis [50, 51].

2.3.5. Haemophilus influenzae

Haemophilus influenzae is a small, non-motile, non-spore-forming, gram-negative pleomorphic rod that can be encapsulated or unencapsulated [52]. Haemophilus influenza is often the first microorganism detected in CF respiratory culture and is mainly prevalent in children and less common in adults. This microorganism is the most common bacteria and is associated with frequent exacerbations of bronchiectasis [53]. However, it is associated with adverse outcomes in chronic respiratory infections like non-CF bronchiectasis, COPD, etc. [54]. In susceptible cases, third-generation cephalosporin is the initial choice of antibiotics. Antibiotic resistance is a growing concern in this case. Several reports demonstrated drug resistance to ampicillin and macrolide like erythromycin. However, the culture specimens have not been found resistant to fluoroquinolones. The commonly prescribed antibiotics in Haemophilus influenzae B are ceftazidime, cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, fluoroquinolones, and azithromycin via the parenteral route. Dexamethasone is also recommended as adjunctive treatment as it reduces the cerebral edema associated with inflammation of the meninges. In non-encapsulated H. influenzae, amoxicillin high dose is the first choice. A combination of amoxicillin/clavulanate is also recommended as a choice. Surgical drainage is also employed in the complicated cases like subdural and pleural effusion [55].

2.3.6. Klebsiella pneumoniae

Klebsiella pneumoniae belongs to the Enterobacteriaceae family and is described as a gram-negative, encapsulate, and non-motile bacterium. Virulence of the bacterium is provided by many factors that can lead to infection and antibiotic resistance [56]. Klebsiella pneumoniae (Friedlander's bacillus) is a rare cause of community-acquired pneumonia but accounts for a higher proportion of pneumonia acquired in hospitals. Patients are more likely to be treated with antibiotics that permit this bacterium to dominate the pharyngeal flora [57]. This microorganism is a notable pulmonary pathogen leading to severe pneumonia and sepsis, mainly in immunocompromised patients. Klebsiella pneumoniae generally occurs in immunocompromised patients due to age, ethanol abuse, or diabetes mellitus. It is common for ventilator-associated pneumonia [58]. In the current regimens, third-fourth generation cephalosporin as monotherapy is prescribed. Additionally, respiratory quinolone is recommended as monotherapy or in conjunction with an aminoglycoside. In penicillin-allergic patients, aztreonam or a respiratory quinolone is prescribed. Carbapenem is given worldwide to treat nosocomial infection and extended-spectrum beta-lactamase cases. However, carbapenem-resistant cases are gradually increasing. In such a case, combining antibiotic options, including polymyxin class, aminoglycosides, tigecycline, and fosfomycin are available [56].

2.3.7. Legionella pneumophila

Legionella infections are caused mainly by Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1 and 13 [59]. Legionella bacterium is a small, aerobic, waterborne, gram-negative, unencapsulated bacillus non-motile, oxidase, and catalase-positive. It resides in surface or drinking water and is transmitted to humans by aerosols. This pathogen is often spread through air cooling systems that use water as a cooler [60]. The bacteria multiply intracellularly in alveolar macrophages. Destructive alveolar inflammation is produced by recruiting neutrophils, monocytes, and bacterial enzymes. Direct inoculation in surgical wounds is possible with contaminated tap water. The bacterium binds to respiratory epithelial cells and alveolar macrophages, after which it enters the cell. Once it has gained entry into the cell, it inhibits phagosome-lysosome fusion, followed by promoting its proliferation. L. pneumophila causes community-acquired and nosocomial pneumonia and should be considered a pathogen in patients with atypical pneumonia [61]. The treatment against Legionella bacterium is based on empirical decisions rather than a proper routine susceptibility test. β-Lactams are the first-line treatment for community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP). Other antibiotics, like macrolides, rifampicin, and fluoroquinolones are less effective in intracellular pathogens. Both azithromycin and levofloxacin are effective against this pathogen [62]. Omadacycline in oral and intravenous form has been approved in CABP, including legionella. In a phase 3 study, omadacycline was found as safe with moxifloxacin in the treatment of CABP [63].

2.3.8. Mycoplasma pneumoniae

M. pneumoniae is a serious and common cause of community-acquired pneumonia in children and adults. M. pneumoniae lacks a rigid cell wall, allowing it to alter its size and shape to suit its surrounding conditions. It is resistant to AMA, which works by targeting the cell wall. This pathogen spreads from person to person by respiratory droplets. It is generally an extracellular pathogen that develops a specific attachment organelle for close association with host cells [64]. This close association prevents the mucociliary clearance mechanism in the host respiratory tract. M. pneumoniae produces hydrogen peroxides and superoxide. Gradually, it damages the respiratory epithelial cells at the base of the cilia. Afterward, it activates the innate immune response and produces local cytotoxic effects [65]. The selection of antibiotics is restricted in this type of infection, and choosing those antibiotics that inhibit protein synthesis of the bacterial ribosome. These antibiotics are macrolides, tetracycline, and streptogramins. Azithromycin is the first choice due to its better tolerance and longer half-life. Ketolides and macrolides serve synergistic activity of anti-inflammatory and bacteriostatic action. Fluoroquinolones are also employed to treat this infection due to their inhibitory DNA replication property. These class drugs are also equally effective as macrolides. Due to the increasing cases of macrolide-resistance, several new antimicrobial agents are developed, and they are omadacycline, lefamulin, nafithromycin, zoliflodacin, and solithromycin [66].

2.3.9. Moraxella catarrhalis

Moraxella catarrhalis is a gram-negative diplococcus that physiologically colonizes the healthy mucosal tissues of the human upper respiratory tract. The bacteria are transmitted exclusively between humans by direct and indirect contact. Risk factors include bacterial load, crowding, winter season, daycare attendance, length of stay in a medical institution, and respiratory therapy [67]. In children, M. catarrhalis causes upper respiratory tract infections (otitis media), whereas, in adults, the pathogen causes lower respiratory tract infections in previously compromised airways [68]. M catarrhalis has been shown to have increased cell adhesion and pro-inflammatory responses when cold shock (26 °C for 3 h) occurs. Physiologically, this may occur with prolonged exposure to cold air temperatures, resulting in cold-like symptoms [69]. Long-acting penicillin can clear the infection. Due to excessive production of β-lactamase, M. catarrhalis more frequently resistant to ampicillin and penicillin. In susceptibility cases, a wide range of antimicrobial agents like amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, azithromycin, clarithromycin, extended-spectrum cephalosporin, tetracycline, trimethoprim-sulfa, and fluoroquinolones are included in this treatment [70].

2.3.10. Pseudomonas aeruginosa

Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an encapsulated, rod-shaped, gram-negative bacterium responsible for acute distress syndrome and acute lung injury. This microorganism is also detected in nosocomial pneumonia or hospital-acquired pneumonia (pneumonia happens after hospitalization and is not pre-incubated at the time of hospitalization), specifically in long-term ventilated patients. No adequate remedy has been developed yet to manage this microorganism, resulting in higher morbidity in chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases (COPD) [71]. The complication in P. aeruginosa-associated lung infection happens due to biofilm formation, which is generally a structural consortium of this microorganism composed of DNA, protein, and polysaccharides. This microorganism interrupts lower and upper airway homeostasis by damaging the epithelium cells and intervening in the adaptive and innate immune response [72]. A wide range of antibiotics is generally prescribed to treat this pathogen, including carbapenems (meropenem, imipenem), aminoglycosides (tobramycin, netilmicin, gentamicin, amikacin), fluoroquinolones (levofloxacin, ciprofloxacin), cephalosporins (cefepime, ceftazidime), β-lactam inhibitors (piperacillin, ticarcillin), polymyxins (polymyxin A and polymyxin B) and fosfomycin. Often a single antibiotic may initiate drug resistance against several antibiotics using the overexpression of efflux systems. In most cases, quinolones have significantly triggered cross-resistance in different classes, including β-lactam and aminoglycoside [73]. Polymyxins are considered the only choice in drug resistance cases of P. aeruginosa. Ceftolozane-tazobactam and ceftazidime-avibactam also found to be effected in this case. In monotherapy, antipseudomonal β-lactams like ceftazidime, piperacillin-tazobactam, cefepime, and aztreonam are effective in multi/extremely-multi drug resistance cases [74].

2.3.11. Stenotrophomonas maltophilia

Stenotrophomonas maltophilia is an aerobic, gram-negative pathogen that frequently attacks, particularly common among adolescents and young adults [75]. It is a multi-drug resistant microorganism associated with several infections, including pneumonia, bacteremia, meningitis, and nosocomial infection, especially in immunocompromised patients. This microorganism is intrinsically and adaptively resistant to many antibiotics. For this reason, S. maltophilia has few pathogenic mechanisms and predominantly results in colonization rather than infection. If the infection does occur, invasive medical devices are usually the vehicles through which the microorganism bypasses typical host defense [76]. The administration of proper drugs is often delayed due to late detection. S. maltophilia is susceptible to several antibiotics like levofloxacin, ticarcillin-clavulanate, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, and doxycycline [77]. Trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole is traditionally used in the treatment of S. maltophilia. Fluoroquinolones are generally recommended as an alternative. However, the use of levofloxacin is limited due to the drug resistance, drug interaction, and safety profile. Additional antimicrobial agents like minocycline and tigecycline are high susceptibility rates [78].

2.3.12. Yersinia pestis

Yersinia pestis is a gram-negative, non-motile, rod-shaped coccobacillus bacterium with no spores. The natural host for this microorganism is a rat. The infection is usually transmitted to humans through a flea bite from a flea fed on an infected rat and then on a human. The disease begins with bronchiolitis and alveolitis, progressing to a lobular and eventual lobar consolidation. A serosanguineous intra-alveolar fluid accumulation with variable fibrin deposits, a fibrinopurulent phase, and necrotizing lesion have been detected in the histopathological study [8]. A complex set of virulence determinants play critical roles in the molecular strategies that Y. pestis employs to subvert the human immune system, allowing unrestricted bacterial replication in the lungs (pneumonic plague) [79]. There are three types of plague disease: bubonic, pneumonic, and septicemic. Pneumonic plague is more likely associated with an aerosolized release of Y. pestis [80]. FDA has approved different treatments, including tetracycline, streptomycin, and fluoroquinolones. Chloramphenicol, gentamicin, and sulphonamides are also suggested as effective therapies. CDC updates treatment and prevention for the plague from time to time [81].

2.4. Fungus

Fungi are commonly detected in respiratory samples, creating clinical uncertainty (CF patients). Fungi can travel along with dust and can survive in the environment. Thousands of conidia are inhaled by humans every day. Many of them create respiratory tract infections (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of lung infections causing fungus and their management.

| Organism | Characteristics | Recommended medicine |

|---|---|---|

| Histoplasma capsulatum | 1. It is associated with bird or bat droppings. 2. It can spread to various organs through blood |

Mainly with Itraconazole, fluconazole, and amphotericin B. Sometimes moxifloxacin, linezolid, azithromycin, levofloxacin, and hydroxychloroquine |

| Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasii | 1. Coccidioidal infections are caused due to airborne transmission 2. It is not contagious but spreads to other body parts like bone, joints, and skin resulting in an extrapulmonary infection. |

Fluconazole, voriconazole, itraconazole, and amphotericin B |

| Pneumocystis jirovecii | 1. Commonly affects immunocompromised patients and can be severely life-threatening in some cases. 2. This microorganism primarily resides in the lungs' alveoli and concentrates mainly in the lower respiratory tract in higher concentrations than upper respiratory tract specimens |

Co-trimoxazole (trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole) |

| Aspergillus fumigatus | 1. This organism is almost ubiquitous in the environment and is the primary cause of the disease 2. Inhaled conidia are engulfed by alveolar macrophages and killed in a phagocyte oxidase-dependent fashion |

Voriconazole andAmphotericin B |

| Cryptococcus neoformans | 1. This microorganism can produce harmless colonies in the airways, leading to meningitis or disseminated disease. 2. Complicates reticuloendothelial malignancy, organ transplantation, corticosteroid treatment, or sarcoidosis |

Amphotericin B |

| Scedosporium prolificans and S. apiospermum | 1. S. apiospermum causes severe disease in immunocompromised patients with a higher mortality rate 2. One of the critical clinical manifestations of this infection is pneumonia. |

Amphotericin B, voriconazole |

| Blastomyces dermatitidis | 1. It attacks immunocompromised and normal immunity persons 2. It can also spread to other common sites like skin and bone and causes extrapulmonary disease |

Itraconazole, Ketoconazole and fluconazole |

| Sporothrix schenckii | 1. This organism is not a primary pathogen in the pulmonary system 2. The microorganism can produce cavitary disease in the form of a single lesion. |

Amphotericin B, caspofungin, Itraconazole, fluconazole and ketoconazole |

| Penicilliosis marneffei | 1. This fungus can infect humans in relatively rare circumstances. 2. It can produce a disseminated infection in healthy and immunocompromised hosts |

Amphotericin B and itraconazole |

| C. pneumonia | 1. It is rare and often noticed in immunocompromised patients admitted to the intensive care unit. 2. This microorganism is aspirating from a heavily colonized or infected oropharynx |

Azole antifungal agents, amphotericin B, and echinocandin |

2.4.1. Histoplasma capsulatum

Pulmonary histoplasmosis (Darling’s disease) is a fungal mycosis of the lung. The causative pathogen for this disease is Histoplasma capsulatum. Most often, it is associated with bird or bat droppings. Spores are produced from the mycelia of H. capsulatum. Upon inhalation, they are deposited in the alveoli. These spores can germinate into the yeast at normal body temperature. Gradually, it becomes parasitic, multiplies, and travels to hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes. Through blood circulation, it can spread to various organs. After 10–14 days of exposure, cellular immunity develops and is clear from macrophages. Any defects in cellular immunity result in a progressive disseminated form of an infection that can be lethal [82]. It survives as a saprophyte and frequently attacks the immunocompromised person (cancer, tuberculosis, HIV, etc.). Humans are infected with this fungus by inhaling air-containing spores. Initially, this infection is asymptomatic. Thus, the common tendency of patients is to ignore the common cold and mild flu-like symptoms. The severity of the disease and associated symptoms depend on the inoculum size. In such cases, non-productive cough, high fever, headache, and chest pain are observed. The commencement of effective antimicrobial treatment might reduce mortality and morbidity in the asymptomatic carrier [83]. Antifungal drugs like itraconazole, fluconazole, and amphotericin B have been used to treat histoplasmosis. Sometimes moxifloxacin, linezolid, azithromycin, levofloxacin, and hydroxychloroquine are administered as empirical therapy [84].

2.4.2. Coccidioides species

Coccidioidomycosis (San Joaquin Valley or Valley fever) is one type of pulmonary infection caused by inhalation of Coccidioides immitis and Coccidioides posadasii. The majority of coccidioidal infections are caused due to airborne transmission. After pulmonary inhalation, single spore deposits in bronchioles gradually transform into spherules. Within 48–72 h, they become filled with hundreds to thousands and initiate tissue inflammation. Through an autolysis process, they thin their cell walls. In the inflammation phase, macrophages engulf some endospores due to the body’s immune system. If these spores are not clear, they progress to the chronic inflammation phase [85]. Neutrophils and eosinophils are attracted to the local region when spherules rupture and release endospores. Mainly, T-helper-2-lymphocytes (Th2) work on abolishing Coccidioides species. However, Th2 deficiency of dysfunction has been detected in patients with disseminated disease [86]. In a few cases, they are not contagious. Therefore, the chances of human-to-human spreading are less. Sometimes, the spherule spreads to other body parts like bone, joints, and skin resulting in an extra-pulmonary infection. The choice of drugs, route, and duration of therapy depends on the severity and location of the infection. Initially, fluconazole prescribes due to an excellent safety record [87], followed by voriconazole and itraconazole. Lipid formulations of amphotericin B are also preferred due to their effective penetrability.

2.4.3. Pneumocystis jirovecii

Pneumocystis carinii Pneumonia (PCP) is now referred to as Pneumocystis jirovecii Pneumonia, a fungal infection most commonly affects immunocompromised patients and can be severely life-threatening in some cases. P. jirovecii is most frequently detected in AIDS-defining diseases. It is also detected in non-HIV immunocompromised patients with a deficiency in adaptive immunity or who take prolonged high-dose systemic glucocorticoids [88]. Structurally, P. jirovecii is a thick-walled cyst. This microorganism primarily resides in the lungs' alveoli and concentrates mainly in the lower respiratory tract in higher concentrations than upper respiratory tract specimens [89]. Torpid infections may occur in patients with acute or chronic bronchopulmonary disease, primarily infected infants, pregnant women, and healthcare workers in contact with infected patients. These colonized patients and patients with Pneumocystis pneumonia represent sources of infection in both the community and hospitals [90]. Co-trimoxazole (trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole) is mainly given through the mouth or vein.

2.4.4. Aspergillus species

Aspergillus mold is the most common fungal species that can sporulate with released airborne conidia. Humans and animals continuously inhale numerous conidia of this fungus. Aspergillus fumigatus is almost ubiquitous in the environment and is the primary cause of the disease, followed by Aspergillus flavus, Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus terreus, Aspergillus nidulans, and several species of Fumigati that morphologically looks like A. fumigatus [91]. They are small enough to reach the airways and pulmonary alveoli. Inhaled conidia are engulfed by alveolar macrophages and killed in a phagocyte oxidase-dependent fashion. However, the incomplete killing of conidia results in germination and tissue invasion. One of the most well-clinical syndromes of fungal colonization in airways is allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (ABPA) caused by A. fumigatus. ABPA is associated with worse lung function [92]. The most effective treatment is observed with voriconazole. Amphotericin B can be an alternative option.

2.4.5. Cryptococcus

Cryptococcosis is a disease state caused by lung exposure to Cryptococcus. Cryptococcus neoformans (Subtype of Cryptococcus) distribute widely, mainly in soil and avian habitats [93]. C. neoformans is a ubiquitous and facultative intracellular yeast. This microorganism can produce harmless colonies in the airways, leading to meningitis or disseminated disease. Cryptococcosis infection's chances mainly occur in persons with defective cell-mediated immunity, and life-threatening situations occur in HIV-infected patients. This microorganism complicates reticuloendothelial malignancy, organ transplantation, corticosteroid treatment, or sarcoidosis [94]. Both symptomatic and asymptomatic infections have been observed in this type of infection. Pulmonary injury patterns include single or multiple large nodules, segmental or diffuse infiltrates, cavitary lesions, and miliary nodules [8]. Generally, amphotericin B is recommended alone or in combination with flucytosine. Fluconazole can be an alternative option. However, amphotericin B has demonstrated better clinical improvement than intravenous or oral fluconazole due to the rapid onset of action.

2.4.6. Scedosporium species

Scedosporium species can be found abundantly in animal droppings, sewage, agricultural soil, and wastewater. Two species of this class, named S. prolificans and S. apiospermum (Pseudallescheria boydii), are rarely reported for human infections. Out of them, S. apiospermum causes severe disease in immunocompromised patients with a mortality rate of 58–100% [95]. In immunocompromised hosts, several conditions are reported, including eye, ear, central nervous system infections, etc. One of the critical clinical manifestations of this infection is pneumonia. P. boydii can grow and multiply in the lung, forming colonies without causing progressive disease [96]. Scedosporium species are generally resistant to amphotericin B. Whereas, S. prolificans stains are resistant to all available antifungal drugs. Voriconazole is a first-line treatment due to its strong in-vitro activity against Scedosporium species.

2.4.7. Blastomyces dermatitidis

Blastomycosis is a chronic granulomatous and suppurative infection produced by Blastomyces dermatitidis. This microorganism is a dimorphic fungus, growing in the environment as a mycelial form and mammalian tissue as a yeast form. This infection may occur in immunocompromised and normal immunity persons [97]. B. dermatitidis is inhaled into the lungs and causes pneumonitis. Initially, It is asymptomatic and undetectable, though severe, life-threatening complications like acute respiratory distress syndrome can occur [98, 99]. It can also spread to other common sites like skin and bone and causes extrapulmonary disease in approximately 25%–30% of patients. It shows the lung's hematogenous distribution, and the skin is the most common site of extra-pulmonary infection [100]. In the lung, pathologic manifestations include focal or diffuse infiltrates, rare lobar consolidation, miliary nodules, solitary nodules, and acute or organizing diffuse alveolar damage [8]. Pulmonary blastomycosis can occasionally persist in the chronic form where productive cough, hemoptysis, and weight loss can observe [101]. Itraconazole is the treatment of choice for all forms of the disease, except in severe, life-threatening cases. Itraconazole has relatively low toxicity and good efficacy, though it is important to remember that its absorption requires gastric acidity. Ketoconazole and fluconazole can be used as alternatives, but they possess lower efficacy. Remarkable side effects are also observed with ketoconazole administration [102].

2.4.8. Sporothrix schenckii

Sporotrichosis is a subacute or chronic infection caused by thermally dimorphic fungi of the genus Sporothrix. For a long time, sporotrichosis was known as rosebush mycosis or gardener's mycosis. The infection usually results from inoculating the agent on the skin or mucous membrane by trauma with contaminated plant material. However, zoonotic transmissions have been reported with less frequent inhaled fungal propagules and systemic mycosis [103]. The causative agent named Sporothrix schenckii mainly attacks the skin, subcutis, and lymphatic pathways. Rarely, S. schenckii is a primary pathogen in the pulmonary system. The characteristic infection involves suppurating subcutaneous nodules progressing proximally along lymphatic channels (lymphocutaneous sporotrichosis). The microorganism can produce cavitary disease in the form of a single lesion. Infection may be bilateral, apical, progressive, destructive, or clinically identified as a solitary pulmonary nodule [8]. A rare form of sporotrichosis appears to result from inhaling the microorganism. This form is characterized by chronic cavitary pneumonia that is clinically and radiographically indistinguishable from tuberculosis and histoplasmosis [104]. In treating S. schenckii, melanin pigment may be hampered due to concurrent administration of amphotericin B and caspofungin. Due to adverse effects, azole compounds were introduced. Itraconazole is used as a first-line treatment with considerable efficacy and safety in most cases of sporotrichosis. This drug demonstrated low toxicity and well-tolerance in long-term therapy [105]. Another drug, amphotericin B, is used to treat disseminated forms, particularly in immunocompromised subjects initially. Amphotericin B may be used after 12 weeks of pregnancy in pregnant women. However, this medication has been recommended for pulmonary and disseminated forms where treatment should be initiated priority. Fluconazole is less effective than itraconazole. It is prescribed to patients who do not tolerate or have drug interactions with itraconazole. Ketoconazole showed higher toxicity and has not demonstrated a good response [106].

2.4.9. Penicilliosis marneffei

Penicilliosis is mainly caused by the Penicillium marneffei, a zoonotic parasitic and pathogenic dimorphic fungus in bamboo rats. However, this fungus can infect humans in relatively rare circumstances. The most significant transmission route is through contact with P. marneffei spores in the soil during the rainy season or at a wound site [107]. P. marneffei can produce a disseminated infection in healthy and immunocompromised hosts [108]. This infection is often detected in HIV-infected persons in South-East Asia. Sometimes, lung mass was observed in chest radiography. However, no respiratory symptoms were observed in patients [109]. Amphotericin B and itraconazole successfully controlled this pulmonary penicilliosis.

2.4.10. Candida species

Candida microorganisms are yeasts that can produce pseudohyphae and are the most common invasive fungal pathogens in humans. Secondary Candida pneumonia is commonly detected in humans, but primary C. pneumoniae is rare and often noticed in immunocompromised patients admitted to the intensive care unit. Other species of this class: C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, and C. albicans are responsible for 95% of blood-stream infections. This route is equally accountable for the acquisition of C. pneumonia. However, a non-blood-borne route is also observed for pneumonia infection, where this microorganism is aspirating from a heavily colonized or infected oropharynx. In the case of aspiration, these microorganisms may be found in the airways associated with an alveolar filling pattern of bronchopneumonia [8]. Initiation of therapy depends on the form of candidiasis and anecdotal reports. In most cases, Azole antifungal agents, amphotericin B, and echinocandin antifungal agents are recommended.

2.5. Parasites

Protozoal infections are the most prevalent intestinal infections worldwide; they rarely involve the lungs and pleura. Pulmonary infections with free-living amoebas, Toxoplasma species, Babesia species, Cryptosporidium species, Leishmania species, and Microsporidia species have been well documented (Table 3).

Table 3.

Summary of lung infections causing parasites and their management.

| Organism | Characteristics | Recommended medicine |

|---|---|---|

| B. divergens and B. microti | 1. The effect on the lung is a consequence of a systemic inflammatory response 2. Acute respiratory distress syndrome develops once the disease complicated |

Clindamycin and quinine sulfate |

| Cryptosporidium hominis and Cryptosporidium parvum | 1. Manifestations of this infection are asymptomatic shedding, acute watery diarrhea (approximately for two weeks), and persistent diarrhea 2. This microorganism targets the epithelium of the airways, gut, and biliary tract. |

Nitazoxanide, paromomycin, and indinavir |

| Dirofilaria immitis | 1. After being injected into the subcutis, this parasite travels into veins and gradually migrates to the heart 2. Parasites possibly grow in the right ventricle and are brushed into small pulmonary arteries |

Diethylcarbamazine and ivermectin |

| Entamoeba histolytica, E. dispar, and E. moshkovskii | 1. Amoebic dysentery becomes invasive in a small percentage of patients 2. The lungs may be affected by direct extension or hematogenous spread |

Metronidazole or tinidazole, paromomycin, iodoquinol, and diloxanide furoate |

| Echinococcus hatch, Echinococcus granulosus and Echinococcus multilocularis | 1. Echinococcosis is a zoonosis that occurs wherever sheep, dogs, or other canids and humans live in close contact. 2. In bronchi, cysts may rupture and cause coughs that eliminate the protoscolices (adult larva) or portions of the cyst wall |

Mebendazole and albendazole |

| Leishmania donovani | 1. transmitted to humans by several species of the Phlebotomus sandfly 2. Pulmonary leishmaniasis has been reported in HIV-infected patients and transplant recipients. |

Pentavalent antimonial derivatives, paromomycin, and liposomal amphotericin B |

| Microsporidia species | 1. microsporidiosis in humans can occur in both immune-competent and immune-compromised hosts. 2. Pulmonary microsporidiosis is often overlooked and characterized by a few non-specific symptoms like cough, fever, and dyspnoea. |

Albendazole (Albenza) and fumagillin |

| Paragonimus species | 1. target the lung and are acquired by ingesting freshwater crabs or crayfish infected with the metacercarial larvae 2. Pulmonary paragonimiasis can cause persistent hemoptysis. |

Triclabendazole, bithionol, niclofolan, praziquantel, and fenbendazole |

| P. falciparum, P. malariae, P. ovale, and P. vivax | 1. The disease is transmitted by the bite of the female Anopheles mosquito. 2. The clinical impact of malaria on the lung may range from mild to severe respiratory insufficiency. |

Antimalarial drugs |

| Schistosoma mansoni, Schistosoma haematobium, and Schistosoma japonicum | 1. eggs transmit to humans through snail-intermediate hosts and penetrate the skin of susceptible animals and people through the free-swimming cercaria 2. Pulmonary schistosomiasis comprises both acute and chronic forms. |

Praziquantel and artesunate |

| Strongyloides stercoralis | 1. This infection may persist as asymptomatic for years 2. It auto-infects the host body |

Ivermectin, albendazole |

| Toxoplasma gondii | 1. Infection occurs by ingesting oocysts or meat-containing live microorganisms 2. This infection is asymptomatic in some cases and is commonly detected in patients with AIDS |

Pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine/clindamycin, azithromycin, and doxycycline |

| Toxocara canis and Toxocara cati | 1. Children are more prone to infection via the fecal-oral route as they are more likely to consume Toxocara eggs. 2. The larvae cross the intestinal wall and travel to many organs, including the lungs. |

Albendazole, mebendazole |

| Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense and Trypanosoma brucei gambiense | 1. Protozoa transmitted to man by biting flies and bedbugs. 2. Pneumonitis is the most frequent lesion in the lungs, placenta membranes, and umbilical cord. |

Nifurtimox and benznidazole |

2.5.1. Babesias species

The Babesias are intraerythrocytic protozoa, of which there exist various species, fundamentally B. divergens and B. microti. Humans acquire the infection (babesiosis) characterized fundamentally by fever and hemolysis through tick bites. The factors for systemic infection are immunosuppression, advanced age, and antecedents of splenectomy. Babesiosis is quite a rare disease in which the effect on the lung is a consequence of a systemic inflammatory response. The clinical manifestations are fever, cough, and labored breathing, with noncardiogenic pulmonary edema being the most systematic development. Acute respiratory distress syndrome developed as a disease complication requiring mechanical ventilation due to respiratory failure and hypoxemia. The treatment of choice is the joint administration of clindamycin and quinine sulfate [110].

2.5.2. Cryptosporidium species

Ten species of intracellular coccidian protozoa are currently recognized. Cryptosporidium species have been found to infect mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish. The two species that most commonly infect humans are Cryptosporidium hominis and Cryptosporidium parvum. The former seems primarily limited to humans, and the latter has a wide range of hosts, including most major domestic livestock animal species [111]. The three main manifestations of this infection are asymptomatic shedding, acute watery diarrhea (approximately for two weeks), and persistent diarrhea for a few weeks [112]. Patients with AIDS have a more comprehensive range of disease severity and duration, including a fulminant cholera-like illness. In the lung, the microorganism targets the epithelium of the airways, just as it does the surface epithelium of the gut and biliary tract. Pulmonary cryptosporidiosis is primarily a case report event, most reports being from earlier phases of the AIDS epidemic [8]. Anti-parasitic drugs like nitazoxanide (FDA-approved treatment) can be helpful in cryptosporidiosis-associated diarrhea. However, this drug is not recommended for respiratory cryptosporidiosis. In some cases, paromomycin has been employed to treat respiratory cryptosporidiosis in AIDS patients. Indinavir (protease inhibitors) can be chosen as this drug interferes with cryptosporidium development. Supportive care and antiretroviral therapy are generally recommended without efficacious treatment of respiratory cryptosporidiosis [113].

2.5.3. Dirofilaria immitis

The zoonosis is caused by Dirofilaria immitis, a parasite of dogs. Human infection is determined by the prevalence of disease in the natural host and the extent to which humans are exposed to mosquito vectors. After being injected into the subcutis, this parasite travels into veins and gradually migrates to the heart. They generally die before they mature into adult worms. There was a misconception as Dirofilaria (heartworm) only resides in the heart. During infection, parasites possibly grow in the right ventricle and are brushed into small pulmonary arteries [114]. Gradually, they form the nidus in the arteries and cause thrombus. At this stage, Human D. immitis infection demonstrates an asymptomatic solitary pulmonary nodule in the lung periphery [8]. No specific antifilarial chemotherapy is indicated for human Dirofilaria infections yet. Thus, the various lesions (caused by worms) can be removed by surgery. No role for antiparasitic agents has been identified as effective in Dirofilaria infection during controlled trials. The antiparasitic treatment is most likely effective in arresting the worm and allowing its subsequent removal since only one infertile parasite is present [115]. Most patients are treated symptomatically with anti-inflammatory agents, including steroids. The worm has usually died long before extraction. Some authors suggested adding oral treatment with diethylcarbamazine (DEC). In some cases, oral ivermectin can be used [116]. Therapy with tetracyclines has been reported to damage D. immitis, even causing the death of adult worms [115].

2.5.4. Entamoeba species

Entamoeba is pseudopod-forming, anaerobic, protozoan parasites belongs to Entamoebidae family. Amoebic dysentery becomes invasive in a small percentage of patients [117]. After leaving the gut, the trophozoites travel to the liver. The lungs may be affected by direct extension or hematogenous spread [8]. Entamoeba histolytica causes most symptomatic diseases. Other species like E. dispar (non-pathogenic) and E. moshkovskii can cause similar infections. These microorganisms spread via the oral-fecal route. The infected cysts are often found in contaminated food and water. The chances of pleuropulmonary amebiasis (extraintestinal amebiasis) increase gradually. This is mainly occurring by inhalation of cysts of E. histolytica infected dust [118]. The first-line treatment has been initiated with metronidazole or tinidazole. Luminal agents like paromomycin, iodoquinol, and diloxanide furoate are also recommended for this infection.

2.5.5. Echinococcus species

Echinococcosis is a zoonosis that occurs wherever sheep, dogs, or other canids and humans live in close contact. Ingested eggs of the tapeworm Echinococcus hatch in the gut, releasing oncospheres, which invade the mucosa, enter the circulation, and travel to various sites, where they develop into hydatid cysts [119]. Unilocular slow-growing cysts in the lung are produced by Echinococcus granulosus. Echinococcus multilocularis proliferates by budding, producing an alveolar pattern of microvesicles. The outer fibrous layer of E. granulosus contains chronic inflammatory cells that interface with the alveolated parenchyma. In bronchi, cysts may rupture and cause coughs that eliminate the protoscolices (adult larva) or portions of the cyst wall. Abscesses (accumulation of pus) and granulomas (inflammation) may also form in the lung, pleura, and chest wall [8]. In Echinococcosis, four current treatment modalities are inadequate and controversial. Generally, treatment outcomes are improved when surgery or PAIR (puncture, aspiration, injection of proto scolicidal agent, and respiration) is combined with benzimidazole drugs given pre-and/or post-operation. Mebendazole and albendazole are the only anthelmintics effective against cystic echinococcosis. Albendazole and mebendazole are well tolerated but show different efficacy [120]. Albendazole chemotherapy was found to be the primary pharmacological treatment in CE management. Nevertheless, combined therapy with albendazole plus praziquantel resulted in higher scolicidal and anti-cyst activity [121].

2.5.6. Leishmania species

Leishmaniasis (Leishmania donovani infection) is transmitted to humans by several species of the Phlebotomus sandfly. Most Leishmania species are digenetic, i.e., they need two hosts to complete their life cycle. The parasite survives within the insect vector and proliferates in the alimentary tract extracellularly. The vertebrate host adopts an obligatory intracellular form that thrives inside phagolysosomes [122]. They are a group of vector-borne parasitic diseases with a high disease burden in the Indian sub-continent. The primary clinical forms are cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL), mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (MCL), and visceral leishmaniasis (VL). Many of these forms affect the viscera (lungs, larynx, gastrointestinal tract, etc.) and are considered opportunistic infections in AIDS patients. The infection of the mucosa of the larynx is another complication of leishmaniasis. They are caused by different species and subspecies of Leishmania [123]. Pulmonary leishmaniasis has been reported in HIV-infected patients and transplant recipients. The microorganism (L. donovani amastigotes) can be found in the alveoli and alveolar septa. Sometimes, pleural effusion is explicitly observed in immunocompetent patients. In VL, pulmonary symptoms depend on many factors like a bacterial infection, hypoalbuminemia, and vagal nerve compression [124]. Pentavalent antimonial derivatives are the primary choice in leishmaniasis. However, other substances such as paromomycin and liposomal amphotericin B are effective alternatives.

2.5.7. Microsporidia species

Microsporidiosis is a disease caused by infection with microscopic microorganisms called microsporidia which are found worldwide in vertebrates and invertebrates and can serve as hosts for these microorganisms. Microsporidia are eukaryotic parasites that grow within other host cells to produce infective spores. At the same time, microsporidiosis in humans can occur in both immune-competent and immune-compromised hosts. It has often been seen in the immune-suppressed population [125]. The microsporidia are obligate intracellular spore-forming protozoa. More than 140 genera and 1200 species are recognized, but only seven genera and a few species have been confirmed as human pathogens [126]. Pulmonary microsporidiosis has been observed in different countries, especially in immunocompromised patients with HIV [127, 128, 129]. Pulmonary microsporidiosis is often overlooked and characterized by a few non-specific symptoms like cough, fever, and dyspnoea. In the lung, these pathogens cause bronchitis or bronchiolitis (or both), usually in patients who also have intestinal infections or disease at other sites, especially the biliary tract [8]. The most commonly used medications for microsporidiosis include albendazole (Albenza) and fumagillin. Intravenous fluid administration and electrolyte repletion may be necessary for patients with diarrhea and dehydration. Dietary and nutritional regimens may also assist with chronic diarrhea. Finally, improving immune system function with antiretroviral therapy in HIV-infected individuals may also improve symptoms [130]. However, no specific treatment for pulmonary microsporidiosis has been framed yet.

2.5.8. Paragonimus species

Paragonimiasis is an infectious disease caused by Trematodes of the genus Paragonimus. Paragonimus species target the lung and are acquired by ingesting freshwater crabs or crayfish infected with the metacercarial larvae of the Paragonimus species. The disease manifestations are related to the migratory route. In most cases, Paragonimus westermani is involved in disease propagation. However, several other species also co-exist. An eosinophil-rich inflammatory reaction occurs in the infection site that evolves to form a fibrous pseudocyst or capsule containing worms, exudate, and debris. Rupturing the cysts within bronchioles may release eggs, resulting in cough and sputum formation. These eggs may become embedded in the parenchyma, producing nodular granulomatous lesions that progress to scars [8]. Pulmonary paragonimiasis can cause persistent hemoptysis. The diagnosis is often missed due to rare occurrences and is mainly endemic in North America, Asia, and Africa [131]. Triclabendazole was approved by the FDA in 2019 for fascioliasis. The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) recommends triclabendazole off-label for treating paragonimiasis. Older therapies (e.g., bithionol, niclofolan) have unacceptable adverse effect profiles compared with praziquantel despite their effectiveness (cure rates ≥90%) [132]. Most patients with paragonimiasis are cured by standard praziquantel treatment. However, several cases have been reported with unsatisfactory responses to the standard praziquantel treatment [133]. Treatment with fenbendazole improves clinical signs and chest radiography [134].

2.5.9. Plasmodium species

Plasmodium comprises the intracellular protozoa that are responsible for malaria. It is, therefore, one of the diseases with the highest morbidity and mortality. Four species of this genus affect humans: P. falciparum, P. malariae, P. ovale, and P. vivax. The disease is transmitted by the bite of the female Anopheles mosquito. In most cases, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) is observed in the infection with P. falciparum rather than other malaria species [135]. Pulmonary edema is the principal manifestation of the effects of malaria on the lung. The increased permeability of the alveolar capillaries appears by a mechanism where the plasmatic liquid fills the alveolar spaces. The clinical impact of malaria on the lung may range from mild (fever, cough, dyspnoea, expectoration, and thoracic pain) to severe respiratory insufficiency. The selection of an antimalarial therapy depends on a series of factors, like species type, the clinical state of a patient, and the parasite's susceptibility to the drugs. One noteworthy aspect is the pulmonary toxicity produced by using mefloquine, with the development of diffuse alveolar damage [110].

2.5.10. Schistosoma species

Schistosomiasis (also known as bilharzia) is an infectious disease caused by trematode parasites of the genus Schistosoma. Disease caused by this parasite results from the immunologic reactions to egg-derived antigens produced by adult worms and the mechanical effects of eggs trapped in blood vessel walls [136]. The public health burden of schistosomiasis is enormous. Different life cycles and disease manifestations are observed in three primary Schistosoma species: Schistosoma mansoni, Schistosoma haematobium, and Schistosoma japonicum. Their eggs transmit to humans through snail-intermediate hosts and penetrate the skin of susceptible animals and people through the free-swimming cercaria [137]. After egg deposition, they develop into adult worms and live in various human venous plexuses. Pulmonary schistosomiasis comprises both acute and chronic forms. Acute diseases like Katayama syndrome manifests with fever, chills, weight loss, gastrointestinal symptoms, myalgia, and urticaria in patients with no previous exposure to the parasite [138]. Acute larval pneumonitis and Loeffler-like eosinophilic pneumonia may be seen in this setting. Chronic pulmonary disease is usually secondary to severe hepatic involvement with portal hypertension. In this setting, the eggs of S. mansoni, and rarely S. japonicum or S. haematobium may be shunted through portosystemic collateral veins to the lungs. The eggs lodge in arterioles and provoke a characteristic granulomatous endarteritis with pulmonary symptoms and radiologic infiltrates [139]. Praziquantel is the primary choice of drug in treating all species of Schistosoma. This drug increases membrane permeability resulting in vacuolation of the tegument [140]. A single dose of metrifonate reduced egg excretion but was marginally better than the placebo at achieving cure in one month. Three trials were conducted with an antimalarial drug named artesunate. Substantial anti-schistosomal effects were observed in one of the three trials, which was at unclear risk of bias due to poor reporting of the trial methods [141].

2.5.11. Strongyloides stercoralis

Strongyloides is a human parasite caused by ingesting eggs of the nematode Strongyloides stercoralis in the small intestinal mucosa. These microorganisms are distinct among the helminths family as they can replicate within the human host. Concurrently, it auto-infects the host body. This infection may persist as asymptomatic for years. When the disease occurs, filariform larvae leave the gut and travel through the pulmonary vasculature. After penetrating the alveoli, they initiate hemorrhage and inflammation. Gradually, abscesses, eosinophilic pneumonia, and Loeffler syndrome are developed. When the elimination is interrupted, these larvae may develop into adult worms, producing eggs and rhabditiform larvae [8]. 1–2 days of ivermectin administration is recommended for a chronic and asymptomatic infection. Sometimes albendazole is co-administered with ivermectin for disseminated infections and hyper-infection syndrome. The treatment duration and administration route must be individualized to eliminate the parasite [142]. However, clinicians may prefer to defer treatment for Strongyloidiasis for infected pregnant patients until after the first trimester. Empiric corticosteroid used to treat wheezing is problematic because they may cause life-threatening hyperinfection [143].

2.5.12. Toxoplasma gondii