Abstract

Introduction

Fractures of long bones unite without any complication except for 2%–10% which may lead to delayed or non-union of the fracture. Management of delayed union of fractures poses a great challenge for orthopaedic surgeons. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) is an autologous blood-derived biological agent, which delivers growth factors, cytokines, and bio-micro molecules at supraphysiologic concentrations at the site of tissue injury, thus potentiating the body's healing efforts. Various studies and research have proved the osteogenic activity of PRP. The growth factors present in the PRP induce the locally available resilient progenitor or stem cells and convert the atrophic environment into a trophic environment.

Materials and methods

We investigated the safety and efficacy of autologous PRP injection in the delayed union of long bone fractures. A total of 25 cases of delayed union of long bone fractures were augmented with 3 doses of autologous PRP at 3 weekly intervals and were followed up for 12 months. All the cases were documented with pre-and post-procedural and 12th -month visual analog score (VAS) and Warden's score.

Results

Out of 25 cases, 21 (84.00%) cases showed good union of fracture with adequate callus formation by 10–12 weeks with 3 doses of autologous PRP injections. The mean pre-procedural VAS and Warden's score at the final follow-up showed statistically significant results (p < 0.05). No other complications were noted due to autologous PRP application among the study participants during the study period except for 3 cases (2 cases of non-union, and 1 case of implant failure).

Conclusion

Results of the current study suggest that autologous injection of PRP might be a safe and effective therapeutic tool for the management of delayed union of long bone fractures.

Keywords: Orthobiologics, Platelet-rich plasma, Delayed union

1. Introduction

Long bone fractures typically heal without any complications; however, anywhere from 2% to 10% of cases can result in delayed or non-union of the fracture.1 The definition of delayed union of fractures are not properly defined in the literature. A delayed union is defined as the absence of radiographic progression of healing or the instability of a fracture upon clinical examination between 4 and 6 months after the initial injury.2,3 Management of delayed union of fractures poses a great challenge for orthopaedicians either to wait and watch or to manage non-surgically with functional cast brace, osteogenic stimulators (bone marrow augmentation, growth factor, or BMP injections), electrical or electromagnetic stimulation, or to manage surgically with bone grafting, bone substitutes, intramedullary nailing, plating, or Ilizarov techniques.2,4

Tissue Engineering and Regenerative Medicine (TERM) has revolutionized the era of the usage of biological substances to treat diseases in a minimally invasive way.5 On par with TERM, the usage of orthobiologics has increased substantially.6, 7, 8 In orthopaedics, the research trend is to prevent major morbidity and mortality and to have therapeutic solutions which enhance tissue regeneration. Molecular biology led to the identification of micromolecules and cytokines that can mediate cellular activities and molecular signaling to target a specific action in the desired site. TERM and orthobiologics use biological materials to regenerate the tissues both in-vitro and in-vivo.9,10 Orthobiologics focus on the concentration of the growth factors to induce the native resident progenitor or stem cells to exert the actions.11

Orthobiologics accelerate the treatment to enhance functional recovery. These orthobiologic substances possess osteoinductive, osteoconductive, and osteointegrative properties which help in osteogenesis.12 Platelet-rich plasma (PRP), a potent orthobiologic, offers an osteoinductive environment and enhances osteogenesis.13 PRP is defined as the volume of plasma in which the platelet concentration of more than 5 to 6 times the baseline, which offers a supraphysiological action.14 PRP is not only a biological scaffold but also contains exosomes with numerous growth factors and cytokines lodged within the alpha (α) granules of the platelets.15 When activated with either CaCl2, thrombin, or photoactivation, platelets release a cascade of growth factors (70% released within 10 min and nearly 100% released within 1 h) which enhances cell-to-cell and cell-to-extracellular matrix (ECM) interactions.16 Once a platelet plug or gel is formed, the growth factor burst is slowed down and acts as a biological scaffold to form a loose fibrin matrix which releases the potential growth factors over weeks.17 Since osteogenesis is a sustained process, the pulsatile release of growth factors is necessary to regenerate the bone tissue.

PRP's osteogenic activity has been demonstrated by some studies and lines of inquiry. The growth factors that are present in the PRP induce the locally available resilient progenitor or stem cells, which in turn transform the environment from atrophic to trophic.11 Platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF), transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β), insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1), epidermal growth factor (EGF), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) are the growth factors found in the PRP solution that stimulate osteogenesis.18,19 Among these growth factors, PDGF is the one that recruits endosteal osteoblasts and stimulates their proliferation, whereas TGF- is the one that encourages the maturation of both fibroblasts and osteoblasts.18 It has also been suggested that PRP has anti-microbial effects, which are properties that are highly desirable when infections are a concern in fracture unions.20 Our research focused on the effectiveness of autologous PRP injections in the treatment of delayed union of long bone fractures.

2. Materials and methods

Ethical considerations: We performed this study after obtaining institutional ethical committee approval from the School of Medical Sciences and Research & Sharda Hospital, Sharda University dated 30.10.2019 [SU/SMS&R/76-A/2019/66].

Study area: Department of Orthopaedics, School of Medical Sciences and Research, Sharda University.

Study design and sample size: A quasi experimental study with a total of 25 cases with delayed union of long bone fractures has been recruited by convenient sampling technique for the study.

Study duration: June 2019 to May 2021.

Study participants: Patients with clinical and radiological signs of delayed union of long bone fractures, age greater than 18 years, and who gave consent for augmentation of delayed union of long bone fractures with autologous PRP injections as per our protocol were included in the study. Patients with a platelet count of less than 1,50,000 per mm³ of blood, age less than 18 years, on medicines known to influence platelet function, local or systemic infections, pseudoarthrosis, pathological fractures, old neglected fractures, fractures with implant failure, and open fractures were excluded from the study.

Study protocol: Patients with the established delayed union at 12–16 weeks of long bone fracture in adults were augmented with 3 doses of autologous PRP injection with each dose being administered at an interval of 3 weeks as per our protocol. Autologous PRP was prepared by differential centrifugation technique. A total of 40 ml of venous blood was subjected to a soft spin of 3000 rpm for 15 min and plasma along with buffy coat was subjected to a hard spin of 5000 rpm for 15 min. The resultant column which contains PRP solution (bottom 1/3rd of the tube) was withdrawn and activated with calcium chloride before injecting into the fracture site. Under c-arm guidance, the delayed union site was localized and an autologous PRP solution is infiltrated. After administering an autologous PRP injection at the fracture site, an external stabilization was given as per the routine management of fractures.

Study outcomes and data collection: During every follow-up [at the end of 1st 3 weeks, 2nd 3 weeks, 3rd 3 weeks, 6th month, and 12th month], the signs of fracture union were analyzed with a plain radiograph. Four cortical union was taken as the union of the fracture. The pain was assessed by a visual analog scale both pre- and post-procedure at every follow-up till 1 year. The results were evaluated using a radiographic scoring system with four possible outcomes after every follow-up until one year by Warden et al.21

Data analysis: The statistical analysis with repeated measures of outcomes was made using repeated measures ANOVA test based on the nature of the variable analyzed. We used IBM SSPS for Windows (Version 25.0, IBM Corp, Chicago, IL, USA) for statistical analysis.

3. Results

The demographic analysis and primary treatment data were tabulated in Table 1. The major incidence of delayed union of fracture was observed after the treatment of long bone fractures by closed reduction with intramedullary nail fixation.

Table 1.

Demographic details of the study population (n = 25).

| Demographic details | Data/No of cases | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Mean age | 40 ± 10 years |

| Range | 29–63 years | |

| Sex | Males | 19 (76.00%) |

| Females | 6 (24.00%) | |

| Mode of injury | Road traffic accident | 17 (68.00%) |

| Fall from height | 7 (28.00%) | |

| Trauma secondary to assault | 1 (4.00%) | |

| Primary treatment | Plating | 7 (36.84%) |

| Nailing | 12 (63.15%) | |

| Conservative management | 6 (24.00%) | |

| Site of delayed union of fracture | Femur | 7 (28.00%) |

| Humerus | 4 (16.00%) | |

| Tibia | 14 (56.00%) | |

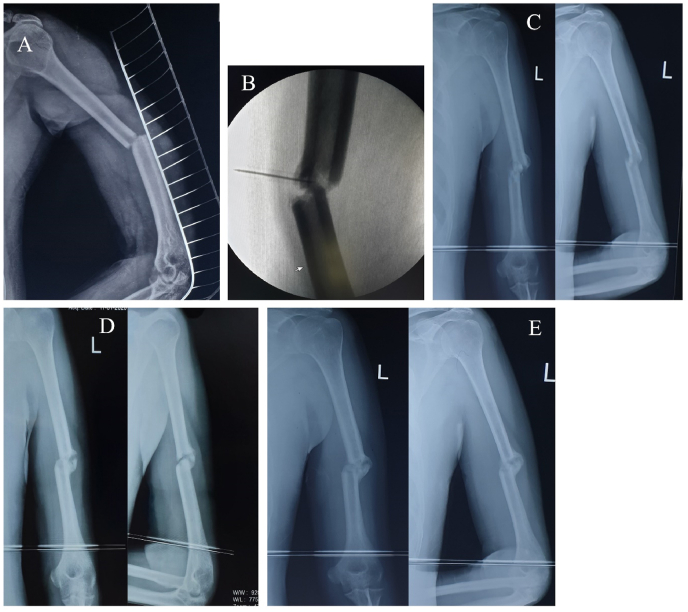

In every sitting, all the patients received 7–8 ml of autologous PRP at the site of delayed union of fracture with mean platelet counts of 2.13 × 106 platelets. Out of 25 cases, 21 (84.00%) cases showed good union of fracture with adequate callus formation by 10–12 weeks with 3 doses of autologous PRP injections. The mean time between surgical treatment and diagnosis of delayed bone union followed by PRP administration was 3.05 months. A total of 3 (12.00%) cases (2 cases of non-union and 1 case of implant failure) failed to unite by 3 doses of autologous PRP injection and hence converted to revision surgery along with bone grafting. One case with delayed union of midshaft right femur fracture was lost in our follow-up. No other complications were noted due to autologous PRP application among the study participants during the study period. The mean pre-procedural VAS score in our series was 6.12 ± 1.32 which was reduced to 1.31 ± 0.10 in the final follow-up in the 12th month. At the end of the 2nd and 3rd three weeks and 6th and 12th-month follow-up, the mean VAS score was statistically significant (p < 0.05) as mentioned in Table 2 and Fig. 1. The mean pre-procedural Warden's score was 0.93 which improved to 3.81 in the final follow-up in the 12th month. At the end of the 2nd and 3rd three weeks and 6th and 12th-month follow-up, the mean Warden's score was statistically significant (p < 0.05) as mentioned in Table 3 and Fig. 1. An illustrative case of management of distal femur delayed union with a retrograde nail and middle third humerus delayed union with autologous PRP injection and final follow-up have been depicted in Fig. 2, Fig. 3.

Table 2.

Mean VAS score among the study population (n = 25).

| Time scale | Mean VAS score | F value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre procedure | 6.12 ± 1.32 | 1.23 | 1.045 |

| At the end of 1st three weeks | 5.64 ± 1.91 | 1.65 | 0.637 |

| At the end of 2nd three weeks | 4.01 ± 0.73 | 2.16 | 0.041 |

| At the end of 3rd three weeks | 2.76 ± 0.37 | 1.34 | 0.027 |

| At the end of 6th month | 2.19 ± 0.10 | 8.78 | <0.001 |

| At the end of 12th month | 1.31 ± 0.10 | 9.23 | <0.001 |

Fig. 1.

Improvement in the mean VAS Score and Warden's Score among the study population (n = 25).

Table 3.

Mean Warden's score among the study population (n = 25).

| Time scale | Mean Warden's score | F value | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pre procedure | 0.93 | 2.56 | 0.881 |

| At the end of 1st three weeks | 1.32 | 1.23 | 0.062 |

| At the end of 2nd three weeks | 2.18 | 10.52 | <0.001 |

| At the end of 3rd three weeks | 3.01 | 8.30 | <0.001 |

| At the end of 6th month | 3.23 | 9.14 | <0.001 |

| At the end of 12th month | 3.81 | 11.84 | <0.001 |

Fig. 2.

Illustrative case of management of distal femur delayed union with retrograde nail A: Pre-intervention status of delayed union at 4 months post fixation; B: Image-guidance autologous PRP injection; C: Follow-up at 3 weeks post PRP; D: Follow-up at 6 weeks post PRP; E: Follow-up at 9 weeks post PRP.

Fig. 3.

Illustrative case of management of delayed union of mid-shaft humerus managed conservatively in a poly-trauma patient. A: Pre-intervention status of delayed union at 3 months of conservative care; B: Image-guidance autologous PRP injection; C: Follow-up at 3 weeks post PRP; D: Follow-up at 6 weeks post PRP; E: Follow-up at 9 weeks post PRP.

4. Discussion

The concept of delayed union of fractures are not fully understood due to the paucity of the time interval to define the delayed union of fractures. Marsh et al. defined delayed union of fracture as the cessation of periosteal response before the fracture united.22 Freeland et al. emphasized on time, location, and configuration of fracture on the particular bone and particular age group to define delayed union of fracture.23 Partial bridging of callus across the fracture site with an open medullary canal defines delayed union of fracture but the progress of fracture union happens at a slower pace than expected.24 Such delayed union of fracture pose a greater challenge for orthopaedic surgeons to intervene surgically.

The concept of TERM emphasizes composite tissue engineering with scaffolds and growth factors with osseous induction, conduction, and integration. PRP, a potent orthobiologic, is an ideal blood product that enhances bone regeneration in a minimally invasive environment.25,26 Osseous healing is regulated by the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the inflammatory phase, which subsequently modulates soft callus and hard callus and finally leads to bone remodeling. PRP contains 94% platelets and 6% other cells namely neutrophils, macrophages/monocytes, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and primitive mesenchymal stem cells.27, 28, 29 Apart from the abovementioned compositions of PRP, recent studies have reported that PRP contains extracellular vesicles (exosomes, microvesicles, and apoptotic bodies) as well,30, 31, 32 they are nanosized vesicles secreted into extracellular spaces and capable of carrying biologically active biomaterials such as lipids, proteins, nucleic acids.33, 34, 35 Growth factors help in migration, differentiation, and proliferation of cells, biosynthesis of ECM, and enhanced tissue repair and regeneration.36 Out of all growth factors from PRP, TGF-β1 and -β2 offer connective tissue healing & osseous regeneration, promote ECM production, stimulate the synthesis of type 1 collagen & fibronectin, mitogenesis of preosteoblasts, induction of bone matrix deposition, and inhibit osteoclast formation and bone resorption.37, 38, 39, 40, 41 VEGF acts as a mitogen of endothelial cells and stimulates neoangiogenesis and vasculogenesis which can activate related intracellular and extracellular molecular-signaling pathways to enhance bone regeneration.

According to the findings of several preclinical studies, the utilization of PRP causes osteoblast-like cells to adhere to one another, migrate, and proliferate. PRP works to recruit more progenitor cells by stimulating osteoblast activity and the release of cytokines in the surrounding environment. The osteoblastic response is dose-dependently influenced by the platelet concentration in the PRP solution. Researchers have found that using PRP reduces the amount of time needed for osseous wounds to heal in clinical studies. PRP is known to contain IL-1Ra, which, in turn, reduces the amount of substance P in the body; as a result, pain transmission is inhibited. There is a correlation between increased levels of hepatocyte growth factor in PRP and decreased levels of COX-1, COX-2, and PGE2.42, 43, 44 PRP induces the differentiation and maturation of osteoblasts in MSC culture, in addition to stimulating the proliferation of human MSCs and osteoblasts, enhancing the expression of BMP-2 and mRNA, and promoting BMP-2 production.

Regarding the osteogenic potential of PRP, there is evidence in the literature that demonstrates controversial results, both positive influence45, 46, 47, 48 and negative influence.49, 50, 51, 52 Numerous studies have shed light on the utilization of PRP for bone regeneration, whether in conjunction with bone grafts or scaffolds or independently of them.53, 54, 55, 56 The use of PRP in conjunction with bone grafts has been shown in several studies to result in significantly improved osseous regeneration in comparison to the use of bone grafts alone in the treatment of osseous defects.53,54,57 Because Jacobson et al. demonstrated a linear relationship between the concentration of platelets and the available cytokines, regenerative medicine specialists are drawn to the use of PRP in the bony defect site to speed up osteogenesis.58 Gianakos et al. reported that 89% of studies reported histological and histomorphometric improvement in earlier osseous healing and significant bone area increment on CT. Based on these findings, the researchers concluded that PRP offers a variety of beneficial effects on osteogenesis in long bones in animal models.59 In their meta-analysis, An et al. suggested that a combination of PRP and autologous bone grafting proved to be effective in delayed or non-union of long bone fractures when compared with the fractures fixed along with autologous bone grafting.60 The studies have shown that exosomes derived from PRP alleviate knee osteoarthritis via the Wnt/-catenin signaling pathway in chondrocytes31 and protected the cartilage in subtalar osteoarthritis.61 As a result, extracellular vesicles in the PRP may also play a role in the study that is currently being conducted. Two different groups of fractures to the shaft of the femur were treated by Singh et al. with intramedullary nailing with or without PRP injection. It was concluded that the effect of PRP was observed during the initial phase of fracture management and not during the later phase of fracture management because a statistical difference was observed between the two groups at the end of the 2nd, 3rd, 4th, and 5th month follow-up but it was not observed during the final follow-up. In the beginning stages of the treatment, PRP functions as an artificial hematoma by producing growth factors.62 Healing rate and bone union time are the most important factors that determine the outcome of the treatment of delayed union and non-union of fractures with PRP. In their meta-analysis, Li et al. recommended that local administration of PRP should be used in cases of delayed union of fractures because it would shorten the treatment period and increase the healing rate. They emphasized that PRP accelerates the healing process of fractures.63 In cases of non-union that were treated with autologous platelet-rich plasma, Say et al. reported that inadequate union of the fracture occurred.64 Golos et al. reported 81.8% of delayed union of fracture cases were successfully united with PRP injection.65

In our study, a total of 84% of the study population have achieved the union of fracture with a dose of autologous PRP injections every 3 weeks for 3 doses. The mean pre-procedural VAS and Warden's score at the final follow-up showed statistically significant results (p < 0.05). The union of the fracture depends upon the time and duration of PRP injection, and the exact site of PRP instillation by peppering technique across the fracture site. Additional external support in the form of a slab, cast, or any form of immobilization has to be given as the administration of PRP treats the fracture on a molecular basis which is also a determinant for the fracture union.

In the management of delayed union of long bone fractures with autologous PRP, both fracture factors and PRP-related factors are responsible for the outcome of the management. The usage of allogenic PRP raises a question in which the immunogenicity of allogenic PRP has not been investigated so far in the literature. There is no consensus on the optimal dose of PRP to be injected for osseous regeneration. The lack of standard protocols in isolation, preparation, and standardization of PRP explains the inconsistent results in the literature for bone healing. Plachokova et al. demonstrated 10-fold more platelet concentration in human-derived PRP than in animals. They showed the release of an enormous amount of growth factors from human-derived PRP when activated.66 The sustained need for growth factors in the bone defect explains the absolute necessity for the usage of either biological or synthetic scaffolds for osseous regeneration.

5. Limitations

Our study has certain limitations such as small sample size, the type of PRP [leucocyte-rich PRP or leucocyte-poor PRP] utilized, the preparatory method of PRP, and a quasi experimental study. The clinical evidences of PRP in delayed union of fractures are very limited in the literature. Hence, we recommend large randomized, blinded controlled studies in the future to further validate the results of our study and generate strong recommendations to validate their daily use in clinical practice.

6. Conclusion

Results of the current study suggest that autologous PRP might be a safe and effective therapeutic tool for the management of delayed union of long bone fractures. However, comparative studies are needed to further validate the results of our study.

Funding sources

Nil.

Institutional ethical committee approval

School of Medical Sciences and Research & Sharda Hospital, Sharda University dated 30.10.2019 – SU/SMS&R/76-A/2019/66.

Author statement

-

(I)

Conception and design: Sudhir Kumar; Madhan Jeyaraman

-

(II)

Administrative support: Rajni Ranjan; Rakesh Kumar

-

(III)

Provision of study materials or patients: Arunabh Arora; Madhan Jeyaraman

-

(IV)

Collection and assembly of data: Arunabh Arora; Madhan Jeyaraman

-

(V)

Data analysis and interpretation: Madhan Jeyaraman; Arulkumar Nallakumarasamy

-

(VI)

Manuscript writing: All authors

All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding statement

All the authors declare that no funding was received for this study.

Declaration of competing interest

Nil.

Acknowledgments

Nil.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jor.2022.12.013.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article.

References

- 1.Volpin G., Shtarker H. In: European Surgical Orthopaedics and Traumatology: The EFORT Textbook. Bentley G., editor. Springer; 2014. Management of delayed union, non-union and mal-union of long bone fractures; pp. 241–266. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boer FC den, Patka P., Bakker F.C., Haarman H.J.T.M. Current concepts of fracture healing, delayed unions, and nonunions. Osteosynth Trauma Care. 2002;10(1):1–7. doi: 10.1055/s-2002-30627. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Polyzois V.D., Papakostas I., Stamatis E.D., Zgonis T., Beris A.E. Current concepts in delayed bone union and non-union. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2006;23(2):445–453. doi: 10.1016/j.cpm.2006.01.005. viii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sharrard W. A double-blind trial of pulsed electromagnetic fields for delayed union of tibial fractures. J Bone Joint Surg. 1990;72-B(3):347–355. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.72B3.2187877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Han F., Wang J., Ding L., et al. Tissue engineering and regenerative medicine: achievements, future, and sustainability in asia. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2020;8:83. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2020.00083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cengiz I.F., Pereira H., de Girolamo L., et al. Orthopaedic regenerative tissue engineering en route to the holy grail: disequilibrium between the demand and the supply in the operating room. J Exp Orthop. 2018;5:14. doi: 10.1186/s40634-018-0133-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tatara A.M., Mikos A.G. Tissue engineering in orthopaedics. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(13):1132–1139. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.16.00299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sezgin E.A., Atik O.Ş. Are orthobiologics the next chapter in clinical orthopedics? A literature review. Eklem Hastalik Cerrahisi. 2018;29(2):110–116. doi: 10.5606/ehc.2018.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh P., Gupta A., Qayoom I., Singh S., Kumar A. Orthobiologics with phytobioactive cues: a paradigm in bone regeneration. Biomed Pharmacother. 2020;130 doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCullen S.D., Chow A.G., Stevens M.M. In vivo tissue engineering of musculoskeletal tissues. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2011;22(5):715–720. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qian Y., Han Q., Chen W., et al. Platelet-rich plasma derived growth factors contribute to stem cell differentiation in musculoskeletal regeneration. Front Chem. 2017;5:89. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2017.00089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gómez-Barrena E., Rosset P., Lozano D., Stanovici J., Ermthaller C., Gerbhard F. Bone fracture healing: cell therapy in delayed unions and nonunions. Bone. 2015;70:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2014.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alsousou J., Thompson M., Hulley P., Noble A., Willett K. The biology of platelet-rich plasma and its application in trauma and orthopaedic surgery. The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery British. 2009;91-B(8):987–996. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.91B8.22546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hussain N., Johal H., Bhandari M. An evidence-based evaluation on the use of platelet rich plasma in orthopedics – a review of the literature. SICOT-J. 2017;3:57. doi: 10.1051/sicotj/2017036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahmad Z., Howard D., Brooks R.A., et al. The role of platelet rich plasma in musculoskeletal science. JRSM Short Rep. 2012;3(6):40. doi: 10.1258/shorts.2011.011148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Foster T.E., Puskas B.L., Mandelbaum B.R., Gerhardt M.B., Rodeo S.A. Platelet-rich plasma: from basic science to clinical applications. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(11):2259–2272. doi: 10.1177/0363546509349921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez I.A., Growney Kalaf E.A., Bowlin G.L., Sell S.A. Platelet-rich plasma in bone regeneration: engineering the delivery for improved clinical efficacy. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/392398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lubkowska A., Dolegowska B., Banfi G. Growth factor content in PRP and their applicability in medicine. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2012;26(2 Suppl 1):3S–22S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Masuki H., Okudera T., Watanebe T., et al. Growth factor and pro-inflammatory cytokine contents in platelet-rich plasma (PRP), plasma rich in growth factors (PRGF), advanced platelet-rich fibrin (A-PRF), and concentrated growth factors (CGF) International Journal of Implant Dentistry. 2016;2(1):19. doi: 10.1186/s40729-016-0052-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Badade P.S., Mahale S.A., Panjwani A.A., Vaidya P.D., Warang A.D. Antimicrobial effect of platelet-rich plasma and platelet-rich fibrin. Indian J Dent Res. 2016;27(3):300–304. doi: 10.4103/0970-9290.186231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warden S.J., Komatsu D.E., Rydberg J., Bond J.L., Hassett S.M. Recombinant human parathyroid hormone (PTH 1-34) and low-intensity pulsed ultrasound have contrasting additive effects during fracture healing. Bone. 2009;44(3):485–494. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2008.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marsh D. Concepts of fracture union, delayed union, and nonunion. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;(355 Suppl):S22–S30. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199810001-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Freeland A.E., Jabaley M.E., Hughes J.L. In: Stable Fixation of the Hand and Wrist. Freeland A.E., Jabaley M.E., Hughes J.L., editors. Springer; 1986. Delayed union, nonunion, and pseudarthrosis; pp. 167–178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ducharme N.G., Nixon A.J. Equine Fracture Repair. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2019. Delayed union, nonunion, and malunion; pp. 835–850. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dhillon M.S., Behera P., Patel S., Shetty V. Orthobiologics and platelet rich plasma. Int J Oceans Oceanogr. 2014;48(1):1–9. doi: 10.4103/0019-5413.125477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dimitriou R., Jones E., McGonagle D., Giannoudis P.V. Bone regeneration: current concepts and future directions. BMC Med. 2011;9(1):66. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-9-66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Woodell-May J.E., Ridderman D.N., Swift M.J., Higgins J. Producing accurate platelet counts for platelet rich plasma: validation of a hematology analyzer and preparation techniques for counting. J Craniofac Surg. 2005;16(5):749–756. doi: 10.1097/01.scs.0000180007.30115.fa. discussion 757-759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andia I., Abate M. Platelet-rich plasma: combinational treatment modalities for musculoskeletal conditions. Front Med. 2018;12(2):139–152. doi: 10.1007/s11684-017-0551-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lana J.F.S.D., da Fonseca L.F., Macedo R. da R., et al. Platelet-rich plasma vs bone marrow aspirate concentrate: an overview of mechanisms of action and orthobiologic synergistic effects. World J Stem Cell. 2021;13(2):155–167. doi: 10.4252/wjsc.v13.i2.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang W., Jiang H., Kong Y. Exosomes derived from platelet-rich plasma activate YAP and promote the fibrogenic activity of Müller cells via the PI3K/Akt pathway. Exp Eye Res. 2020;193 doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2020.107973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu X., Wang L., Ma C., Wang G., Zhang Y., Sun S. Exosomes derived from platelet-rich plasma present a novel potential in alleviating knee osteoarthritis by promoting proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis of chondrocyte via Wnt/β-catenin signaling pathway. J Orthop Surg Res. 2019;14(1):470. doi: 10.1186/s13018-019-1529-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Guo S.C., Tao S.C., Yin W.J., Qi X., Yuan T., Zhang C.Q. Exosomes derived from platelet-rich plasma promote the re-epithelization of chronic cutaneous wounds via activation of YAP in a diabetic rat model. Theranostics. 2017;7(1):81–96. doi: 10.7150/thno.16803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gangadaran P., Ahn B.C. Extracellular vesicle- and extracellular vesicle mimetics-based drug delivery systems: new perspectives, challenges, and clinical developments. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(5):E442. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics12050442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rajendran R.L., Gangadaran P., Kwack M.H., et al. Human fibroblast-derived extracellular vesicles promote hair growth in cultured human hair follicles. FEBS Lett. 2021;595(7):942–953. doi: 10.1002/1873-3468.14050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gangadaran P., Rajendran R.L., Oh J.M., et al. Identification of angiogenic cargo in extracellular vesicles secreted from human adipose tissue-derived stem cells and induction of angiogenesis in vitro and in vivo. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(4):495. doi: 10.3390/pharmaceutics13040495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pavlovic V., Ciric M., Jovanovic V., Stojanovic P. Platelet Rich Plasma: a short overview of certain bioactive components. Open Med. 2016;11(1):242–247. doi: 10.1515/med-2016-0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davis V.L., Abukabda A.B., Radio N.M., et al. Platelet-rich preparations to improve healing. Part I: workable options for every size practice. J Oral Implantol. 2014;40(4):500–510. doi: 10.1563/AAID-JOI-D-12-00104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gurtner G.C., Werner S., Barrandon Y., Longaker M.T. Wound repair and regeneration. Nature. 2008;453(7193):314–321. doi: 10.1038/nature07039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bonewald L.F., Mundy G.R. Role of transforming growth factor-beta in bone remodeling. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;250:261–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wrotniak M., Bielecki T., Gaździk T.S. Current opinion about using the platelet-rich gel in orthopaedics and trauma surgery. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2007;9(3):227–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simpson A.H.R.W., Mills L., Noble B. The role of growth factors and related agents in accelerating fracture healing. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88(6):701–705. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B6.17524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhang J., Middleton K.K., Fu F.H., Im H.J., Wang J.H.C. HGF mediates the anti-inflammatory effects of PRP on injured tendons. PLoS One. 2013;8(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bendinelli P., Matteucci E., Dogliotti G., et al. Molecular basis of anti-inflammatory action of platelet-rich plasma on human chondrocytes: mechanisms of NF-κB inhibition via HGF. J Cell Physiol. 2010;225(3):757–766. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang Y., Xing F., Luo R., Duan X. Platelet-rich plasma for bone fracture treatment: a systematic review of current evidence in preclinical and clinical studies. Front Med. 2021;8:1224. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.676033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anitua E. Plasma rich in growth factors: preliminary results of use in the preparation of future sites for implants. Int J Oral Maxillofac Implants. 1999;14(4):529–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marx R.E., Carlson E.R., Eichstaedt R.M., Schimmele S.R., Strauss J.E., Georgeff K.R. Platelet-rich plasma: growth factor enhancement for bone grafts. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 1998;85(6):638–646. doi: 10.1016/s1079-2104(98)90029-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schlegel K.A., Donath K., Rupprecht S., et al. De novo bone formation using bovine collagen and platelet-rich plasma. Biomaterials. 2004;25(23):5387–5393. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2003.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thorwarth M., Rupprecht S., Falk S., Felszeghy E., Wiltfang J., Schlegel K.A. Expression of bone matrix proteins during de novo bone formation using a bovine collagen and platelet-rich plasma (prp)--an immunohistochemical analysis. Biomaterials. 2005;26(15):2575–2584. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Raghoebar G.M., Schortinghuis J., Liem R.S.B., Ruben J.L., van der Wal J.E., Vissink A. Does platelet-rich plasma promote remodeling of autologous bone grafts used for augmentation of the maxillary sinus floor? Clin Oral Implants Res. 2005;16(3):349–356. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0501.2005.01115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Aghaloo T.L., Moy P.K., Freymiller E.G. Investigation of platelet-rich plasma in rabbit cranial defects: a pilot study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2002;60(10):1176–1181. doi: 10.1053/joms.2002.34994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fuerst G., Gruber R., Tangl S., Sanroman F., Watzek G. Effects of fibrin sealant protein concentrate with and without platelet-released growth factors on bony healing of cortical mandibular defects. An experimental study in minipigs. Clin Oral Implants Res. 2004;15(3):301–307. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-0501.2003.01007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fuerst G., Reinhard G., Tangl S., Mittlböck M., Sanroman F., Watzek G. Effect of platelet-released growth factors and collagen type I on osseous regeneration of mandibular defects. A pilot study in minipigs. J Clin Periodontol. 2004;31(9):784–790. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2004.00561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang Y.D., Wang G., Sun Y., Zhang C.Q. Combination of platelet-rich plasma with degradable bioactive borate glass for segmental bone defect repair. Acta Orthop Belg. 2011;77(1):110–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hakimi M., Jungbluth P., Sager M., et al. Combined use of platelet-rich plasma and autologous bone grafts in the treatment of long bone defects in mini-pigs. Injury. 2010;41(7):717–723. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2009.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Yamada Y., Ueda M., Naiki T., Takahashi M., Hata K.I., Nagasaka T. Autogenous injectable bone for regeneration with mesenchymal stem cells and platelet-rich plasma: tissue-engineered bone regeneration. Tissue Eng. 2004;10(5-6):955–964. doi: 10.1089/1076327041348284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Han B., Woodell-May J., Ponticiello M., Yang Z., Nimni M. The effect of thrombin activation of platelet-rich plasma on demineralized bone matrix osteoinductivity. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(6):1459–1470. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kanthan S.R., Kavitha G., Addi S., Choon D.S.K., Kamarul T. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) enhances bone healing in non-united critical-sized defects: a preliminary study involving rabbit models. Injury. 2011;42(8):782–789. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2011.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jacobson M., Fufa D., Abreu E.L., Kevy S., Murray M.M. Platelets, but not erythrocytes, significantly affect cytokine release and scaffold contraction in a provisional scaffold model. Wound Repair Regen. 2008;16(3):370–378. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2008.00376.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gianakos A., Zambrana L., Savage-Elliott I., Lane J.M., Kennedy J.G. Platelet-rich plasma in the animal long-bone model: an analysis of basic science evidence. Orthopedics. 2015;38(12):e1079–e1090. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20151120-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.An W., Ye P., Zhu T., Li Z., Sun J. Platelet-rich plasma combined with autologous grafting in the treatment of long bone delayed union or non-union: a meta-analysis. Front Surg. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2021.621559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang Y., Wang X., Chen J., et al. Exosomes derived from platelet-rich plasma administration in site mediate cartilage protection in subtalar osteoarthritis. J Nanobiotechnol. 2022;20(1):56. doi: 10.1186/s12951-022-01245-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Singh R., Rohilla R., Gawande J., Kumar Sehgal P. To evaluate the role of platelet-rich plasma in healing of acute diaphyseal fractures of the femur. Chin J Traumatol. 2017;20(1):39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cjtee.2016.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li S., Xing F., Luo R., Liu M. Clinical effectiveness of platelet-rich plasma for long-bone delayed union and nonunion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Med. 2021;8 doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.771252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Say F., Türkeli E., Bülbül M. Is platelet-rich plasma injection an effective choice in cases of non-union? Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech. 2014;81(5):340–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Gołos J., Waliński T., Piekarczyk P., Kwiatkowski K. Results of the use of platelet rich plasma in the treatment of delayed union of long bones. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil. 2014;16(4):397–406. doi: 10.5604/15093492.1119617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Plachokova A.S., van den Dolder J., van den Beucken JJJP, Jansen J.A. Bone regenerative properties of rat, goat and human platelet-rich plasma. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2009;38(8):861–869. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.