Abstract

Bacteriophage (phage) therapy in combination with antibiotic treatment serves as a potential strategy to overcome the continued rise in antibiotic resistance across bacterial pathogens. Understanding the impacts of evolutionary and ecological processes to the phage‐antibiotic‐resistance dynamic could advance the development of such combinatorial therapy. We tested whether the acquisition of mutations conferring phage resistance may have antagonistically pleiotropic consequences for antibiotic resistance. First, to determine the robustness of phage resistance across different phage strains, we infected resistant Escherichia coli cultures with phage that were not previously encountered. We found that phage‐resistant E. coli mutants that gained resistance to a single phage strain maintain resistance to other phages with overlapping adsorption methods. Mutations underlying the phage‐resistant phenotype affects lipopolysaccharide (LPS) structure and/or synthesis. Because LPS is implicated in both phage infection and antibiotic response, we then determined whether phage‐resistant trade‐offs exist when challenged with different classes of antibiotics. We found that only 1 out of the 4 phage‐resistant E. coli mutants yielded trade‐offs between phage and antibiotic resistance. Surprisingly, when challenged with novobiocin, we uncovered evidence of synergistic pleiotropy for some mutants allowing for greater antibiotic resistance, even though antibiotic resistance was never selected for. Our results highlight the importance of understanding the role of selective pressures and pleiotropic interactions in the bacterial response to phage‐antibiotic combinatorial therapy.

Keywords: bacteriophage, Escherichia coli, lipopolysaccharide, pleiotropy, trade‐offs

We describe how exposure to bacteriophages results in the evolution of E. coli phage‐resistance, and this resistance is conferred to related phages that the bacteria were never exposed. Evolved phage‐resistance may come at a cost of antibiotic resistance, but the interactions are mutation and antibiotic context‐dependent.

1. INTRODUCTION

The discovery and distribution of antibiotics has drastically reduced mortality due to infectious disease over the last 80 years. The widespread and oftentimes inappropriate use of antibiotics has led to the evolution of multidrug resistant (MDR) pathogenic bacteria. More than 2.8 million antibiotic‐resistant infections occur in the United States each year resulting in more than 35,000 deaths (Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021). If measures are not taken to curb the antibiotic resistance trajectory, worldwide MDR infection mortality may exceed 10 million by 2050 (O'Neill, 2014), which demands prompt development of alternatives to antibiotic usage. Bacteriophage (phage) therapy was utilized before the discovery and widespread distribution of penicillin, and with the emergence of MDR bacteria, the interest in phage therapy has sparked again (Lin et al., 2017), with the understanding that phage resistance could also arise in pathogenic bacterial populations. Studies investigating a combinatorial approach of phages and antibiotics have provided promising outcomes (Aslam et al., 2019; Tagliaferri et al., 2019); however, the interactions between evolutionary factors involved in phage and antibiotic resistance and their role in bacterial evolution remain unsettled due to their synergistic nature. Previous work has identified such interactions between phage resistance and antibiotic resistance, but the nature of the effect is dependent on the specific genotypes of bacteria and phage studied (Burmeister & Turner, 2020; German & Misra, 2001; Scanlan et al., 2015). Better understanding the impacts of evolutionary and ecological processes to the phage‐antibiotic‐resistance dynamic could advance the development of combinatorial therapy to combat MDR bacterial infections.

Specificity toward bacterial hosts offers a unique advantage of phage therapy over antibiotic therapy. A more targeted therapeutic approach could reduce negative impacts on commensal flora (Ganeshan & Hosseinidoust, 2019), and could relieve selective pressures for antibiotic resistance to arise in bacteria not targeted by the treatment. Such host specificity comes from interactions between phage proteins and host cell receptors. Bacteriophages initiate the infection of host cells through adsorption where interactions between binding proteins of the bacteriophage and bacterial cell surface receptors help recognize a sensitive host to inject genetic material (Bertozzi Silva et al., 2016). Researchers have identified several bacterial cell surface receptors involved in the adsorption process. In Gram‐negative bacteria, lipopolysaccharide (LPS), outer membrane proteins, pili, and flagella are typical receptors for phage attachment and entry. On the other hand, in Gram‐positive bacteria, common receptors include peptidoglycan, teichoic acids, and polysaccharides exposed on the bacteria's surface (Dowah & Clokie, 2018). Many bacterial strains evolve phage resistance through developing mechanisms to prevent this adsorption (Rostøl & Marraffini, 2019), and while clinicians could theoretically allow phage to co‐evolve in tandem with their bacterial hosts within a patient, the unpredictability of phage “winning” the co‐evolutionary battle is of concern. Therefore, researchers have turned toward a combinatorial strategy of antibiotics and phage to combat MDR infections.

Pleiotropy occurs when a single gene influences multiple traits on a phenotypic level (Paaby & Rockman, 2013). Synergistic pleiotropy occurs when a single gene or mutation improves two or more traits, whereas antagonistic pleiotropy occurs when beneficial effects on a focal trait are accompanied by deleterious effects on others (Cooper & Lenski, 2000; Magwire et al., 2010; Wenger et al., 2011). Trade‐offs resulting from antagonistic pleiotropic interactions have traditionally been used to explain the biological phenomena of senescence (Hughes et al., 2002; Promislow, 2004; Williams, 1957), but could also be applied to other study areas, such as niche expansion (Duffy et al., 2006; Kassen, 2002; MacLean et al., 2004; Orr, 2000; Remold, 2012), and niche construction (Chisholm et al., 2018). Evolutionary interactions between antibiotic resistance and phage resistance can be pleiotropic in effect oftentimes resulting in bacterial trade‐offs. Phage entry mechanisms use the same structures employed in other bacterial processes, therefore, mutations in these mechanisms to avoid phage infection could impact these bacterial processes, such as antibiotic response (Burmeister & Turner, 2020). By understanding the evolutionary trade‐offs between phage and antibiotic challenge to MDR bacteria, we could theorize that targeted phage therapy of MDR bacteria could be employed until phage resistance arises. Many studies have shown the occurrence of synergistic pleiotropy when microbes are exposed to differing yet simultaneous (or fluctuating) selective pressures (Burmeister & Turner, 2020; Hall et al., 2019; McGee et al., 2016; Moulton‐Brown & Friman, 2018; Sackman & Rokyta, 2019). Therefore, we theorize that phage and antibiotic therapy in sequence, not simultaneously, to avoid the occurrence of phage‐antibiotic‐resistant phenotypes. If we predict that phage‐resistance comes at a cost of antibiotic resistance, it would be beneficial to begin with phage therapy until the infection either clears or phage‐resistance arises followed by a subsequent antibiotic challenge to the more susceptible bacteria to clear the pathogen from the human host.

We selected for phage resistant mutations to arise in Escherichia coli strain C cultures by exposing wild‐type E. coli to four different, but closely related, lytic bacteriophage strains in the Microviridae family. Phage‐resistant mutations arose in response to infection for each phage strain in each E. coli culture. We then infected the phage‐resistant E. coli with phages it was not previously exposed to determine whether mutations conferred a correlated response to selection. We hypothesize that resistance to one phage that utilizes specific cell surface receptors for adsorption would confer resistance to other phages with overlapping adsorption methods. We then challenged phage‐resistant E. coli mutants with 8 different antibiotics to determine interactions between phage‐resistance and antibiotic‐resistance phenotypes to determine the prevalence of antagonistic pleiotropy. We conducted full‐genome sequencing of each E. coli culture to identify mutations that could be attributed to the phage‐ and antibiotic‐resistant phenotypes.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Bacterial growth and conditions

We grew bacteria in lysogeny broth (LB) with 10 g tryptone, 5 g yeast extract, and 10 g/L NaCl supplemented with 2 mM CaCl2. LB plates included 15 g/L agar, or 7.5 g/L for top agar. For liquid cultures, overnight incubation was performed at 200 rpm shaking at 37°C. For agar cultures, overnight incubation was performed in a cabinet incubator at 37°C.

2.2. Bacteriophage and bacterial strains

All assays were conducted with Escherichia coli strain C and 4 bacteriophage strains, ID8, NC28, WA11, and WA13. The phages are all members of the Microviridae family, and are closely related: ID8 (G4‐like clade), NC28 and WA13 (WA13‐like clade), and WA11 (ΦX174‐like clade) (Rokyta et al., 2006). These phage strains are characterized by a circular, single‐stranded DNA genome of roughly 5 kilobases encoding 11 genes with nonenveloped, tailless capsids, icosahedral geometry. All of these phage strains grow in laboratory conditions in Escherichia coli C cultures at 37°C. Further genetic characterization and phenotypic assays have been conducted on these phage strains (McGee et al., 2016; Rokyta et al., 2006;2009).

2.3. Isolating phage‐resistant E. coli

Independent Escherichia coli C cultures were grown from isolated colonies. We infected cultures of Escherichia coli C with 4 bacteriophage strains, ID8, NC28, WA11, and WA13, until resistant bacterial colonies emerged to each phage. E. coli C cultures were grown in LB broth at 37°C to approximately 108 CFU/ml. E. coli was mixed with ~106 phage (one phage strain per culture) in top agar and grown at 37°C for 24 h. Individual bacterial colonies were picked from the plate from within the lytic zone. Each colony was confirmed as phage‐resistant E. coli to their respective phage via spot assay (see spot assay methods below). We archived freezer stocks of each mutant in 20% glycerol, stored at −80°C.

2.4. Phage infectivity spot assays

We tested whether each phage‐resistant E. coli C mutant was susceptible to infection by other bacteriophages to which it was not previously exposed. We acquired isolates of phage‐resistant E. coli mutants to each of the four phages, ID8, NC28, WA11, and WA13, and plated lawns with 100 μl of each bacterial culture. We conducted spot tests by adding ~2000 virions of each phage in 2 μl droplets to each bacterial lawn and incubating at 37°C for 24 h (Carlson, 2005). Clear zones indicating viral lysis of bacterial cells were scored as (2) complete clearing, no turbidity; (1) partial clearing, opaque or turbidity; and (0) no clearing. All assays were conducted in triplicate on each plate and across triplicate plates.

2.5. Antibiotic assays

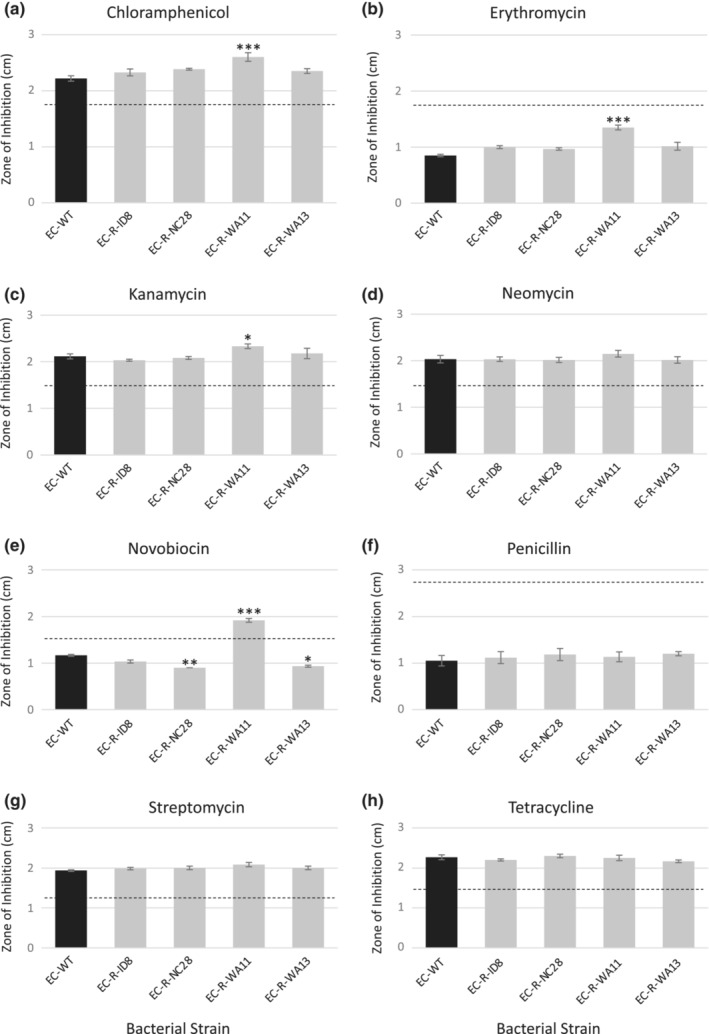

Kirby‐Baur tests were conducted for each phage‐resistant E. coli C and WT E. coli C. Bacterial lawns were inoculated with 100 μl of each bacterial mutant. The antibiotics challenged on each bacterial mutant were chloramphenicol, erythromycin, streptomycin, kanamycin, penicillin, neomycin, novobiocin, and tetracycline. Three antibiotic discs of each antibiotic tested were placed onto two replicate bacterial mutant plates for a total of six replicates for each antibiotic assay (Carolina #805081). Plates were incubated at 37°C for 24 h. At 24 h, the diameter of the zone of inhibition was measured for each antibiotic disc. Estimates for the level of antibiotic resistance as indicated by dashed lines in Figure 1, which were determined based on the provided information from BD BBL™ Sensi‐Disc™ Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test Disc kit.

FIGURE 1.

Antibiotic challenge against phage‐resistant Escherichia coli C mutants. Phage‐resistant mutants were challenged with antibiotic discs and compared with wild‐type E. coli C. the phages include ID8 (G4‐like clade), NC28 and WA13 (WA13‐like clade), and WA11 (ΦX174‐like clade). Dashed lines indicate the threshold for antibiotic resistance based on the BD BBL antibiotic susceptibility test disc kit. Antibiotics used include (a) chloramphenicol, (b) erythromycin, (c) kanamycin, (d) neomycin, (e) novobiocin, (f) penicillin, (g) streptomycin, (h) tetracycline. Assays were conducted with six replicates and statistical tests were done through pairwise contrasts with Dunnett test to correct for multiple comparisons. Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

2.6. Genome sequence analysis

DNA was extracted from bacterial cultures using the Qiagen DNeasy Ultraclean Microbial Kit (12224–50). DNA samples were sent to the at IU Center for Genomics and Bioinformatics where the Nanopore barcoded DNA library was prepared and sequenced with a Nanopore Flow Cell. Reads were assembled with Canu (Koren et al., 2017), assembled contigs were circularized with Circulator, and VarScan was then used to call the SNPs compared with the wild‐type E. coli C strain (Koboldt et al., 2012).

2.7. Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were conducted in R (R Core Team, 2021). A one‐way ANOVA was used to determine the overall effects of antibiotic, resistance, and the interaction on the response variable, zone of inhibition. The emmeans package allows for post hoc comparisons between groups after a fitting a model (Lenth, 2019). These subsequent pairwise contrasts were conducted to compare the zone of inhibition of E. coli WT (control group) to each phage‐resistant E. coli mutant (treatment group) for each antibiotic. This set of comparisons can be requested via trt.vs.ctrl. A Dunnett's test was used to correct for multiple comparisons, which is the default multiple comparisons adjustment used by the emmeans package.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Phage‐Resistance carryover due to a correlated response to selection

To determine whether phage resistance toward one strain of Microviridae bacteriophage conferred resistance to other related phages, we challenged each phage‐resistant E. coli mutant to bacteriophages that were not previously encountered. We hypothesized that resistance to one phage that utilizes specific cell surface receptors for adsorption would confer resistance to other phages with overlapping adsorption methods. We found that bacteria exposed to one phage strain developed resistance to not only that strain but also other related strains that it had not been previously exposed (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Phage infectivity spot assays

| Phage ID8 | Phage NC28 | Phage WA11 | Phage WA13 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli Wild‐type | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| E. coli‐R‐ID8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| E. coli‐R‐NC28 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| E. coli‐R‐WA11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| E. coli‐R‐WA13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Note: Spot assays to determine phage infectivity were conducted on wild‐type and phage‐resistant E. coli cultures. Clear zones indicating viral lysis of bacterial cells were scored as (2) complete clearing, no turbidity; (1) partial clearing, opaque or turbidity; and (0) no clearing. Virus infectivity only occurred on wild‐type E. coli C, indicated by lysis zones on the agar plate. For the phage‐resistance E. coli strains, phage infectivity was inhibited for all phage strains.

To determine the underlying genetic factors contributing to the phage‐resistant phenotype, E. coli mutants were sequenced using next‐generation sequencing technology and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) differing from wild‐type E. coli strain C were identified (Table 2). All 4 phage‐resistant E. coli strains (EC‐R‐ID8, EC‐R‐NC28, EC‐R‐WA11, and EC‐R‐WA13) contained mutations that affect lipopolysaccharide (LPS) structure and/or synthesis. LPS covers the surface of the outer membrane in Gram‐negative bacteria. Each LPS molecule contains lipid A, core oligosaccharides, and, in some bacteria, a highly variable O‐antigen component. All four E. coli phage‐resistant strains contained a non‐synonymous point mutation, L544F (TTG → TTT), in the yciM gene. yciM contributes to cell wall integrity by regulating LPS biosynthesis. The yciM gene encodes a tetratricopeptide repeat that regulates the biosynthesis of lipid A, an essential component of Gram‐negative LPS structure (Bateman et al., 2021; Mahalakshmi et al., 2014). In addition to the yciM mutation, strains EC‐R‐ID8 and EC‐R‐WA13 both had a nonsense point mutation, Q18* (CAG → TAG) in the rfaH gene. The rfaH protein interacts with the RNA polymerase and works to inhibit Rho‐dependent transcriptional termination (Svetlov et al., 2007). By inhibiting transcriptional termination, operons involved with LPS synthesis are expressed. Therefore, the Q18* (CAG → TAG) would impair LPS synthesis, which could result in lack of receptors for phage absorption. Lastly, in addition to the yciM mutation, strain EC‐R‐WA11 also had the point mutation H160L (CAC → CTC) located in the rfaP gene. The rfaP protein is involved in the pathway for LPS core biosynthesis as part of the bacterial outer membrane (Bateman et al., 2021; Pagnout et al., 2019). Mutations in the LPS structure and synthesis may have disabled all strains that use LPS as a receptor for absorption mechanisms from gaining entry to the host cell. This resistance carryover would be of concern for the implementation of phage therapy as resistance developed toward one phage strain could impact the effectiveness of an entire bacteriophage family. In order to plan effectively, a phage arsenal would need to contain phages that can target the same pathogenic host cell, but utilize different absorption mechanisms.

TABLE 2.

Genome analysis of resistant E. coli mutants compared with wild‐type E. coli C.

| Bacterial strain | Nucleotide position | Nucleotide substitution | Amino acid substitution | Gene | Gene function |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EC‐R‐ID8 | 2,531,684 | C → A | L544F (TTG → TTT) | yciM | Lipopolysaccharide synthesis |

| 4,485,909 | C → T | Q18* (CAG → TAG) | rfaH | Lipopolysaccharide synthesis | |

| EC‐R‐NC28 | 2,531,684 | C → A | L544F (TTG → TTT) | yciM | Lipopolysaccharide synthesis |

| EC‐R‐WA11 | 75,889 | A → T | H160L (CAC → CTC) | rfaP | Lipopolysaccharide core heptose(I) kinase |

| 2,531,684 | C → A | L544F (TTG → TTT) | yciM | Lipopolysaccharide synthesis | |

| EC‐R‐WA13 | 2,531,684 | C → A | L544F (TTG → TTT) | yciM | Lipopolysaccharide synthesis |

| 4,485,909 | C → T | Q18* (CAG → TAG) | rfaH | Lipopolysaccharide synthesis |

3.2. Phage‐antibiotic‐resistance trade‐offs and pay‐offs

We then determined whether phage‐resistant trade‐offs exist when challenged with different classes of antibiotics. Antibiotics used include chloramphenicol, erythromycin, kanamycin, neomycin, novobiocin, penicillin, streptomycin, and tetracycline, allowing us to test across different mechanisms of action and differences in inherent susceptibility to the antibiotic (indicated by dashed lines in Figure 1). A larger zone of inhibition around the antibiotic disc indicates more susceptibility to the antibiotic. Only 1 out of the 4 phage‐resistant E. coli strains yielded trade‐offs between phage and antibiotic resistance. The strain where trade‐offs were detected, EC‐R‐WA11, exhibited loss in antibiotic resistance across 4 of the 8 antibiotics tested. EC‐R‐WA11, with mutations in both the yciM and rfaP genes, resulted in greater antibiotic susceptibility to chloramphenicol (p < .0001), erythromycin (p < .0001), kanamycin (p = .04), novobiocin (p < .0001) compared with wild‐type (Figure 1). Phage‐resistance due to mutations in LPS structure have been previously identified and determined to increase sensitivity to antibiotics, particularly in the rfa operons.

RfaP mutations often result in severely truncated LPS core regions, and this phenotype has been shown to be hypersensitive to hydrophobic antibiotics, such as chloramphenicol, kanamycin, erythromycin, and novobiocin (Chang et al., 2010; Pagnout et al., 2019). RfaP proteins catalyze the phosphorylation of heptose I in the bacterial outer membrane. When rfaP is absent or inhibited, lack of phosphorylation of heptose I results in greater permeability of the membrane allowing for entry of hydrophobic antibiotics into the cell (Yethon et al., 1998). Once inside the cell, chloramphenicol, kanamycin, and erythromycin inhibit bacterial protein synthesis. Novobiocin inhibits DNA gyrase in bacteria, but has been shown to exhibit poor bacteriocidal activity against Gram‐negative pathogens (Gellert et al., 1976). In fact, novobiocin has been proposed to be used in combination with polymyxins, such as colistin, due to their synergistic activity against bacteria (Mandler et al., 2018). Polymyxins disrupts the outer membrane of Gram‐negative bacteria, and novobiocin further impacts the bacterial outer membrane by binding to LptB, which is an ATPase that powers LPS transport to deliver LPS to the cell surface. Researchers found that novobiocin‐polymyxin together are more potent than novobiocin alone (Mandler et al., 2018). Therefore, the synergy we uncovered here may be due to mutated LPS structure as a result of phage infection followed by lack of LPS maintenance as a result of novobiocin binding to LptB.

Surprisingly, the other 3 phage‐resistant mutants (EC‐R‐ID8, EC‐R‐NC28, EC‐R‐WA13) gained antibiotic resistance to novobiocin compared with wild‐type E. coli, with only strains EC‐R‐NC28 and EC‐R‐WA13 being significantly more resistant (p = .007 and .02, respectively; Figure 1). Therefore, a mutation in yciM alone, or the combination of yciM and rfaH mutants, result in a pay‐off due to synergistic pleiotropy in which mutations conferring phage resistance also allows for greater antibiotic resistance, even though antibiotic resistance was never selected for. This finding was unexpected due to susceptibility of LPS mutants with defects in the basal core to hydrophobic antibiotics, such as novobiocin. However, other LPS mutants, in particular mutations not affecting the core polysaccharide, have been found to maintain the permeability barrier that can still inhibit novobiocin entry into the cell (Nobre et al., 2015). It is possible that the yciM and rfaH mutants make entry across the outer membrane even more difficult for novobiocin, resulting in greater phage and antibiotic resistance.

Limitations of this study include isolating a single phage‐resistant colony per bacteriophage infection. Future studies should evaluate additional colonies that arose due to bacteriophage infection to examine different paths to phage resistance.

4. CONCLUSIONS

Understanding the evolutionary implications of phage‐antibiotic‐resistance dynamics is crucial for advancing treatment against MDR bacteria. Here we show that a resistance carryover across bacteriophages that are closely related and use the same method of entry into a bacterial cell. To implement phage therapy effectively, we need to consider the development of phages that can target the same pathogenic host cell, but utilize different absorption mechanisms. Additionally, our results highlight the importance of understanding the role of selective pressures and pleiotropic interactions in the bacterial response to phage‐antibiotic combinatorial therapy. More work is needed to understand these complicated evolutionary responses, in particular to avoid the evolution of multidrug and multi‐phage resistant pathogens.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Lindsey W. McGee: Conceptualization (lead); formal analysis (equal); funding acquisition (lead); writing – original draft (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Yazid Barhoush: Investigation (equal); writing – original draft (equal); writing – review and editing (equal). Rafaella Shima: Formal analysis (equal); methodology (equal); writing – original draft (equal). Miette Hennessy: Investigation (equal); methodology (equal); writing – original draft (equal); writing – review and editing (equal).

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Earlham College for start‐up funding and support through the endowed Stephensen Fund. Thank you to Drenushe Krasniqi and Skylar Lhatso‐Suppan for their laboratory work collecting preliminary data. We would also like to thank Dr. Darin Rokyta at Florida State University for providing bacteriophage strains. We would like to thank the reviewers for the time and effort to review the manuscript and for the valuable comments and suggestions.

McGee, L. W. , Barhoush, Y. , Shima, R. , & Hennessy, M. (2023). Phage‐resistant mutations impact bacteria susceptibility to future phage infections and antibiotic response. Ecology and Evolution, 13, e9712. 10.1002/ece3.9712

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Any data not made available directly in the manuscript are available at Science Data Bank and NCBI. Bacterial genome data are available in the NCBI BioSample database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/biosample/) under accession numbers SAMN31581070, SAMN31581071, SAMN31581072, SAMN31581073, SAMN31581074.

REFERENCES

- Aslam, S. , Courtwright, A. M. , Koval, C. , Lehman, S. M. , Morales, S. , Furr, C. L. L. , Rosas, F. , Brownstein, M. J. , Fackler, J. R. , Sisson, B. M. , & Biswas, B. (2019). Early clinical experience of bacteriophage therapy in 3 lung transplant recipients. American Journal of Transplantation, 19(9), 2631–2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman, A. , Martin, M. J. , Orchard, S. , Magrane, M. , Agivetova, R. , Ahmad, S. , Alpi, E. , Bowler‐Barnett, E. H. , Britto, R. , Bursteinas, B. , Bye‐A‐Jee, H. , Coetzee, R. , Cukura, A. , Da Silva, A. , Denny, P. , Dogan, T. , Ebenezer, T. , Fan, J. , Castro, L. G. , … UniProt Consortium . (2021). UniProt: The universal protein knowledgebase in 2021. Nucleic Acids Research, 49(D1), D480–D489. 10.1093/nar/gkaa1100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertozzi Silva, J. , Storms, Z. , & Sauvageau, D. (2016). Host receptors for bacteriophage adsorption. In FEMS microbiology letters (Vol. 363). Oxford University Press. 10.1093/femsle/fnw002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burmeister, A. R. , & Turner, P. E. (2020). Trading‐off and trading‐up in the world of bacteria–phage evolution. Current Biology, 30(19), R1120–R1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, K. (2005). Appendix: Working with bacteriophages. In Bacteriophages: Biology and applications (pp. 437–494). CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention . (2021). Antimicrobial Resistance. https://www.cdc.gov/drugresistance/about.html [Google Scholar]

- Chang, V. , Chen, L. Y. , Wang, A. , & Yuan, X. (2010). The effect of lipopolysaccharide core structure defects on transformation efficiency in isogenic Escherichia coli BW25113 rfaG, rfaP, and rfaC mutants. Journal of Microbiology and Immunology, 14, 101–107. [Google Scholar]

- Chisholm, R. H. , Connelly, B. D. , Kerr, B. , & Tanaka, M. M. (2018). The role of pleiotropy in the evolutionary maintenance of positive niche construction. The American Naturalist, 192(1), 35–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, V. S. , & Lenski, R. E. (2000). The population genetics of ecological specialization in evolving Escherichia coli populations. Nature, 407(6805), 736–739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowah, A. S. , & Clokie, M. R. (2018). Review of the nature, diversity and structure of bacteriophage receptor binding proteins that target gram‐positive bacteria. Biophysical Reviews, 10(2), 535–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, S. , Turner, P. E. , & Burch, C. L. (2006). Pleiotropic costs of niche expansion in the RNA bacteriophage Φ6. Genetics, 172(2), 751–757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganeshan, S. D. , & Hosseinidoust, Z. (2019). Phage therapy with a focus on the human microbiota. Antibiotics (Basel, Switzerland), 8(3), 131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gellert, M. , O'Dea, M. H. , Itoh, T. , & Tomizawa, J. I. (1976). Novobiocin and coumermycin inhibit DNA supercoiling catalyzed by DNA gyrase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 73(12), 4474–4478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- German, G. J. , & Misra, R. (2001). The TolC protein of Escherichia coli serves as a cell‐surface receptor for the newly characterized TLS bacteriophage. Journal of Molecular Biology, 308(4), 579–585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall, A. E. , Karkare, K. , Cooper, V. S. , Bank, C. , Cooper, T. F. , & Moore, F. B. G. (2019). Environment changes epistasis to alter trade‐offs along alternative evolutionary paths. Evolution, 73(10), 2094–2105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, K. A. , Alipaz, J. A. , Drnevich, J. M. , & Reynolds, R. M. (2002). A test of evolutionary theories of aging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 99(22), 14286–14291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kassen, R. (2002). The experimental evolution of specialists, generalists, and the maintenance of diversity. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 15(2), 173–190. [Google Scholar]

- Koboldt, D. C. , Zhang, Q. , Larson, D. E. , Shen, D. , McLellan, M. D. , Lin, L. , Miller, C. A. , Mardis, E. R. , Ding, L. , & Wilson, R. K. (2012). VarScan 2: Somatic mutation and copy number alteration discovery in cancer by exome sequencing. Genome Research, 22(3), 568–576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koren, S. , Walenz, B. P. , Berlin, K. , Miller, J. R. , Bergman, N. H. , & Phillippy, A. M. (2017). Canu: Scalable and accurate long‐read assembly via adaptive k‐mer weighting and repeat separation. Genome Research, 27(5), 722–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenth, R. (2019). Emmeans: Estimated marginal means, aka least‐squares means. R package version 1.4.1. Retrieved June 29, 2020 at https://cran.r‐project.org/package=emmeans

- Lin, D. M. , Koskella, B. , & Lin, H. C. (2017). Phage therapy: An alternative to antibiotics in the age of multi‐drug resistance. World Journal of Gastrointestinal Pharmacology and Therapeutics, 8(3), 162–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean, R. C. , Bell, G. , & Rainey, P. B. (2004). The evolution of a pleiotropic fitness tradeoff in Pseudomonas fluorescens. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 101(21), 8072–8077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magwire, M. M. , Yamamoto, A. , Carbone, M. A. , Roshina, N. V. , Symonenko, A. V. , Pasyukova, E. G. , Morozova, T. V. , & Mackay, T. F. (2010). Quantitative and molecular genetic analyses of mutations increasing drosophila life span. PLoS Genetics, 6(7), e1001037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahalakshmi, S. , Sunayana, M. R. , SaiSree, L. , & Reddy, M. (2014). yciM is an essential gene required for regulation of lipopolysaccharide synthesis in Escherichia coli . Molecular Microbiology, 91(1), 145–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mandler, M. D. , Baidin, V. , Lee, J. , Pahil, K. S. , Owens, T. W. , & Kahne, D. (2018). Novobiocin enhances polymyxin activity by stimulating lipopolysaccharide transport. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 140(22), 6749–6753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee, L. W. , Sackman, A. M. , Morrison, A. J. , Pierce, J. , Anisman, J. , & Rokyta, D. R. (2016). Synergistic pleiotropy overrides the costs of complexity in viral adaptation. Genetics, 202(1), 285–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulton‐Brown, C. E. , & Friman, V. P. (2018). Rapid evolution of generalized resistance mechanisms can constrain the efficacy of phage–antibiotic treatments. Evolutionary Applications, 11(9), 1630–1641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nobre, T. M. , Martynowycz, M. W. , Andreev, K. , Kuzmenko, I. , Nikaido, H. , & Gidalevitz, D. (2015). Modification of salmonella lipopolysaccharides prevents the outer membrane penetration of novobiocin. Biophysical Journal, 109(12), 2537–2545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Neill, J. (2014). Review on Antimicrobial Resistance Antimicrobial Resistance: Tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations. Review on Antimicrobial Resistance. [Google Scholar]

- Orr, H. A. (2000). Adaptation and the cost of complexity. Evolution, 54(1), 13–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paaby, A. B. , & Rockman, M. V. (2013). The many faces of pleiotropy. Trends in Genetics, 29(2), 66–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagnout, C. , Sohm, B. , Razafitianamaharavo, A. , Caillet, C. , Offroy, M. , Leduc, M. , Gendre, H. , Jomini, S. , Beaussart, A. , Bauda, P. , & Duval, J. F. (2019). Pleiotropic effects of rfa‐gene mutations on Escherichia coli envelope properties. Scientific Reports, 9(1), 1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Promislow, D. E. (2004). Protein networks, pleiotropy and the evolution of senescence. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 271(1545), 1225–1234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team . (2021). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; https://www.R‐project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- Remold, S. (2012). Understanding specialism when the jack of all trades can be the master of all. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 279(1749), 4861–4869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rokyta, D. R. , Abdo, Z. , & Wichman, H. A. (2009). The genetics of adaptation for eight microvirid bacteriophages. Journal of Molecular Evolution, 69(3), 229–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rokyta, D. R. , Burch, C. L. , Caudle, S. B. , & Wichman, H. A. (2006). Horizontal gene transfer and the evolution of microvirid coliphage genomes. Journal of Bacteriology, 188(3), 1134–1142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rostøl, J. T. , & Marraffini, L. (2019). (Ph) ighting phages: How bacteria resist their parasites. Cell Host & Microbe, 25(2), 184–194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackman, A. M. , & Rokyta, D. R. (2019). No cost of complexity in bacteriophages adapting to a complex environment. Genetics, 212(1), 267–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan, P. D. , Buckling, A. , & Hall, A. R. (2015). Experimental evolution and bacterial resistance:(co) evolutionary costs and trade‐offs as opportunities in phage therapy research. Bacteriophage, 5(2), e1050153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svetlov, V. , Belogurov, G. A. , Shabrova, E. , Vassylyev, D. G. , & Artsimovitch, I. (2007). Allosteric control of the RNA polymerase by the elongation factor RfaH. Nucleic Acids Research, 35(17), 5694–5705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tagliaferri, T. L. , Jansen, M. , & Horz, H. P. (2019). Fighting pathogenic bacteria on two fronts: Phages and antibiotics as combined strategy. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology, 9, 22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenger, J. W. , Piotrowski, J. , Nagarajan, S. , Chiotti, K. , Sherlock, G. , & Rosenzweig, F. (2011). Hunger artists: Yeast adapted to carbon limitation show trade‐offs under carbon sufficiency. PLoS Genetics, 7(8), e1002202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, G. C. (1957). Pleiotropy, natural selection, and the evolution of senescence: Evolution 11, 398–411. Science of Aging Knowledge Environment, 2001(1), cp13. [Google Scholar]

- Yethon, J. A. , Heinrichs, D. E. , Monteiro, M. A. , Perry, M. B. , & Whitfield, C. (1998). Involvement of waaY, waaQ, and waaP in the modification of Escherichia coli Lipopolysaccharide and their role in the formation of a stable outer membrane. Journal of Biological Chemistry, 273(41), 26310–26316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Any data not made available directly in the manuscript are available at Science Data Bank and NCBI. Bacterial genome data are available in the NCBI BioSample database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/biosample/) under accession numbers SAMN31581070, SAMN31581071, SAMN31581072, SAMN31581073, SAMN31581074.