Abstract

Background

Germline mutations of breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1 and BRCA2 (gBRCA1/2) are associated with elevated risk of breast cancer in young women in Asia. BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins contribute to genomic stability through homologous recombination (HR)-mediated double-strand DNA break repair in cooperation with other HR-related proteins. In this study, we analyzed the targeted sequencing data of Korean breast cancer patients with gBRCA1/2 mutations to investigate the alterations in HR-related genes and their clinical implications.

Materials and methods

Data of the breast cancer patients with pathogenic gBRCA1/2 mutations and qualified targeted next-generation sequencing, SNUH FiRST cancer panel, were analyzed. Single nucleotide polymorphisms, small insertions, and deletions were analyzed with functional annotations using ANNOVAR. HR-related genes were defined as ABL1, ATM, ATR, BARD1, BRCA1, BRCA2, CDKN1A, CDKN2A, CHEK1, CHEK2, FANCA, FANCD2, FANCG, FANCI, FANCL, KDR, MUTYH, PALB2, POLE, POLQ, RAD50, RAD51, RAD51D, RAD54L, and TP53. Mismatch-repair genes were MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6. Clinical data were analyzed with cox proportional hazard models and survival analyses.

Results

Fifty-five Korean breast cancer patients with known gBRCA1/2 mutations and qualified targeted NGS data were analyzed. Ethnically distinct mutations in gBRCA1/2 genes were noted, with higher frequencies of Val1833Ser (14.8%), Glu1210Arg (11.1%), and Tyr130Ter (11.1%) in gBRCA1 and Arg2494Ter (25.0%) and Lys467Ter (14.3%) in gBRCA2. Considering subtypes, gBRCA1 mutations were associated with triple-negative breast cancers (TNBC), while gBRCA2 mutations were more likely hormone receptor-positive breast cancers. At least one missense mutation of HR-related genes was observed in 44 cases (80.0%). The most frequently co-mutated gene was TP53 (38.1%). In patients with gBRCA1/2 mutations, however, genetic variations of TP53 occurred in locations different from the known hotspots of those with sporadic breast cancers. The patients with both gBRCA1/2 and TP53 mutations were more likely to have TNBC, high Ki-67 values, and increased genetic mutations, especially of HR-related genes. Survival benefit was observed in the TP53 mutants of patients with gBRCA2 mutations, compared to those with TP53 wild types.

Conclusion

Our study showed genetic heterogeneity of breast cancer patients with gBRCA1 and gBRCA2 mutations in the Korean populations. Further studies on precision medicine are needed for tailored treatments of patients with genetic diversity among different ethnic groups.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40246-022-00447-3.

Keywords: BRCA, P53, Breast cancer, NGS, Signature 3

Introduction

Germline mutations of breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1 and BRCA2 (gBRCA1/2) are associated with an elevated lifetime risk of cancer in multiple organs including breast, ovary, colon, prostate, and pancreas [1–3]. Breast cancer in patients with gBRCA1/2 mutations accounts for 1–4% of all breast cancer, but the prevalence increases up to 8–30% in familial or early-onset breast cancer [4–7]. Especially in the Asian populations, gBRCA1/2-associated breast cancer are known to develop in younger age, with higher incidence of germline BRCA2 (gBRCA2) mutation than germline BRCA1 (gBRCA1) when compared to other ethnicities [6, 8, 9].

BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins act as tumor suppressors that has distinct role in homologous recombination (HR)-mediated double-strand DNA break repair (DDR) [10, 11]. In response to DNA damage, BRCA1 and BRCA2 proteins interact with a numbers of other proteins including BARD1, PALB2, and RAD51 to maintain genomic integrity [12–16]. Tumors with deficiency or mutations in these genes, known as homologous recombination deficiency (HRD), are considered sensitive to poly(adenosine diphosphate [ADP]–ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors that stall replication fork and lead to synthetic lethality [17].

HRD is identified as a potential prognostic and predictive biomarker across multiple cancer types [18–21], and currently, multiple methods to measure HRD are developed [22–24]. While these methods utilizing whole-genome and whole-exome sequencing techniques are expected to harbor in-depth information about the HR-related gene mutations, its application is still expensive, laborious, and time-consuming for most of the patients in clinical settings [25]. Alternatively, targeted sequencing provides genetic mutations and is useful to identify therapeutic biomarkers. In this study, we analyzed the targeted sequencing data of Korean breast cancer patients with gBRCA1/2 mutations to investigate the alterations in HR-related genes and their clinical implications.

Materials and methods

Study design and subjects

This is a retrospective cohort study of the breast cancer patients with pathogenic gBRCA1/2 mutations from October 2015 to December 2020 at Seoul National University Hospital, Seoul, Korea. The patients with breast cancer of age 20 years or older who had gBRCA1/2 mutation and SNUH FiRST cancer panel, a targeted next-generation sequencing (NGS) platform, were included. Pathologic diagnosis and immunohistochemistry (IHC) on estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), and human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) status were confirmed by the pathologic reports of surgical and percutaneous biopsies. ER or PR ≥ 1% in IHC were considered hormone receptor-positive. HER2-positive was defined according to the manufacturer’s criteria and ASCO/CAP 2018 guideline.

Genetic sequencing

Genomic DNA was isolated from peripheral blood leukocytes and were tested for pathogenic gBRCA1/2 mutation by direct Sanger sequencing. Patients with equivocal variants and variants of unknown significance were excluded from analyses.

DNA was extracted from breast cancer and was subjected to targeted NGS platform named SNUH FiRST Cancer Panel. SNUH FiRST panel included 214 genes (version 3.0), 215 genes (version 3.1), and 216 genes (version 3.2) including microsatellite status with five microsatellite markers (D2S123, D5S346, D17S250, BAT25, and BAT26).

The NGS data with either mean coverage were less than 100X or the proportion of bases with coverage above 50X were less than 80% were regarded as disqualified and were excluded. Adaptor sequences and low-quality reads of targeted sequencing data were trimmed with fastp [26]. Trimmed reads were aligned with reference genome UCSC hg19, using BWA (version 0.7.17) [27]. Preprocessing was performed using MarkDuplicates, BaseRecalibrator, and ApplyBQSR function of GATK best practices (version 4.1.7.0) [28, 29]. After calling single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP) and small insertions and deletions (INDEL) using Tumor-only mode Mutect2 in the preprocessed BAM file, the GATK FilterMutectCalls function was performed. For both SNP and INDEL, variants satisfying allele depth ≥ 3, total depth ≥ 10, minimum allele depth in both strands > 1, and variable allele frequency (VAF) > 0.2 remained. The strand bias test was conducted by using a Fisher’s exact test, leaving only variants that met the criteria of p value > 1 × 10–6 for SNP and p value > 1 × 10–20 for INDEL. Functional annotation of the variants was performed using ANNOVAR (version 20,191,024) [30]. Among variants located within the exon or splicing region, variants satisfying minor allele frequency (MAF) ≤ 0.01 in the population databases (Exome aggregation consortium—East Asian, 1000 Genomes project—East Asian, gnomAD—East Asian, NHLBI ESP6500) were used in the downstream analysis [31–34]. Among single nucleotide polymorphisms, silent mutations were excluded. The TP53 Database R20, July 2019 version was used [35]. R package maftools was used to draw the heatmap of HR-related gene mutations and lollipop plots for TP53 amino acid changes [36].

Following list of genes were considered as HR-related genes: ABL1, ATM, ATR, BARD1, BRCA1, BRCA2, CDKN1A, CDKN2A, CHEK1, CHEK2, FANCA, FANCD2, FANCG, FANCI, FANCL, KDR, MUTYH, PALB2, POLE, POLQ, RAD50, RAD51, RAD51D, RAD54L, and TP53 [11, 37]. Mismatch-repair (MMR) genes were defined as MLH1, MSH2, and MSH6.

Statistical analyses

Categorical variables were summarized with the frequencies in number and rates in percentages. Continuous variables were represented with the median values and ranges. Differences were assessed using Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables and Pearson’s χ2 or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables. Multivariable Cox-proportional hazard models were constructed to find risk factors for survivals and correlation among covariates.

Overall survival (OS) was defined as the time from diagnosis of breast cancer to death of any cause. The OS curves were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. If patients survived without death, the survival was censored at the latest date of follow-up when no death was confirmed. Log-rank test p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Data and statistical analyses were performed in R version 4.1.3 and RStudio version 2022.02.0 with R packages survminer and survival [38].

Results

Patient characteristics

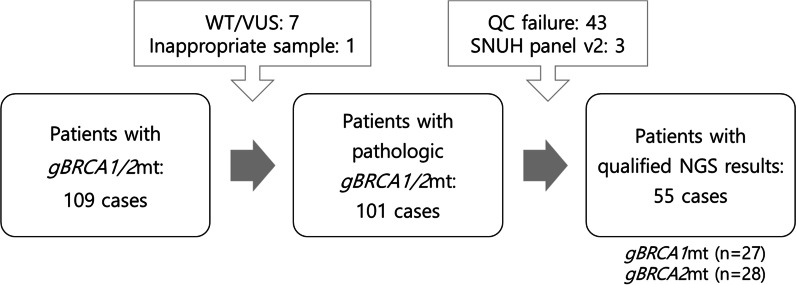

Among 109 breast cancer patients with known gBRCA1/2 mutations and targeted NGS data, 7 patients who had silent mutations or variance of unknown significance were excluded. One patient was excluded because NGS was done from uterine adenosarcoma. Forty-six cases failed in quality assurance of NGS. Eventually, 55 patients with pathogenic gBRCA1/2 mutations with qualified NGS data were included in the study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Enrollment of the breast cancer patients with pathogenic gBRCA1/2 mutations

All patients were of Korean ethnicity, and one male patient was included. The median age of all patients at the diagnosis of breast cancer was 42 years old, and majority of the patients were in premenopausal or perimenopausal state (39 of 55, 70.9%). Family history of breast cancer was found in 34 patients (61.8%). Thirteen patients (23.6%) had bilateral breast cancer, and 4 patients (7.3%) also suffered from ovarian cancer. Half of the patients (28 of 55, 50.9%) underwent prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and 8 patients (14.5%) had prophylactic mastectomy. Most patients (50 of 55, 90.9%) had early breast cancer, and five de novo stage IV patients were included. The most common subtype was hormone receptor-positive, HER2-negative breast cancer (28 of 55, 50.9%), followed by triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC, 23 of 55, 41.8%), and hormone receptor-positive, HER2-positive breast cancer (2 of 55, 3.6%). Median Ki-67 value was 10.0. The baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Median (range) | All patients | gBRCA1 | gBRCA2 | p value (gBRCA1 vs. gBRCA2) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

TP53 wild type (N = 15) |

TP53 mutant (N = 12) |

p value |

TP53 wild type (N = 19) |

TP53 mutant (N = 9) |

p value | |||

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 54 (98.2%) | 15 (100.0%) | 12 (100.0%) | 1.000 | 18 (94.7%) | 9 (100.0%) | 1.000 | 1.000 |

| Male | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (5.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||||

| Age at diagnosis | 42.0 (27–71) | 45.0 (29–67) | 39.5 (28–55) | 0.406 | 39.0 (27–57) | 45.0 (27–71) | 0.941 | 0.980 |

| Family history | 34 (61.8%) | 10 (66.7%) | 7 (58.3%) | 0.964 | 9 (47.4%) | 8 (88.9%) | 0.092 | 1.000 |

| Bilateral breast cancer | 13 (23.6%) | 4 (26.7%) | 2 (16.7%) | 0.877 | 2 (10.5%) | 5 (55.6%) | 0.035 | 1.000 |

| Ovarian cancer | 4 (7.3%) | 2 (13.3%) | 1 (8.3%) | 1.000 | 1 (5.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1.000 | 0.577 |

| Menopausal state | 0.044 | 0.534 | 0.404 | |||||

| Pre- or perimenopausal | 39 (70.9%) | 9 (60.0%) | 12 (100.0%) | 13 (68.4%) | 5 (55.6%) | |||

| Postmenopausal | 15 (27.3%) | 6 (40.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (26.3%) | 4 (44.4%) | |||

| Male | 1 (1.8%) | 1 (5.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||||

| Prophylactic BSO | 28 (50.9%) | 8 (53.3%) | 6 (50.0%) | 1.000 | 11 (57.9%) | 3 (33.3%) | 0.418 | 1.000 |

| Prophylactic mastectomy | 8 (14.5%) | 4 (26.7%) | 2 (16.7%) | 0.877 | 1 (5.3%) | 1 (11.1%) | 1.000 | 0.229 |

| TNM stage at diagnosis | 0.921 | 0.080 | 0.192 | |||||

| I | 6 (10.9%) | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (8.3%) | 1 (5.3%) | 3 (33.3%) | |||

| II | 28 (50.9%) | 7 (46.7%) | 4 (33.3%) | 11 (57.9%) | 6 (66.7%) | |||

| III | 16 (29.1%) | 5 (33.3%) | 5 (41.7%) | 6 (31.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| IV | 5 (9.1%) | 2 (13.3%) | 2 (16.7%) | 1 (5.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| Node positive | 37 (67.3%) | 10 (66.7%) | 9 (75.0%) | 0.962 | 16 (84.2%) | 2 (22.2%) | 0.006 | 0.847 |

| Subtypes | 0.218 | 0.185 | 0.006 | |||||

| Hormone receptor + HER2- | 28 (50.9%) | 7 (46.6%) | 2 (16.7%) | 11 (78.9%) | 4 (44.4%) | |||

| Hormone receptor + HER2 + | 2 (3.6%) | 0 ( 0.0%) | 0 ( 0.0%) | 1 ( 5.3%) | 1 (11.1%) | |||

| TNBC | 25 (45.5%) | 8 (53.3%) | 10 (83.3%) | 3 (15.8%) | 4 (44.4%) | |||

| Ki-67 | 10.0 (1–90) | 10.0 (1–70) | 40.0 (10–90) | 0.006 | 5.0 (1–30) | 10.0 (2–20) | 0.120 | 0.036 |

| Relapse | 23 (41.8%) | 6 (40.0%) | 3 (25.0%) | 0.681 | 8 (42.1%) | 6 (66.7%) | 0.418 | 0.327 |

| Local | 3 (5.5%) | 1 (6.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (10.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| Contralateral | 11 (20.0%) | 2 (13.3%) | 2 (16.7%) | 2 (10.5%) | 5 (55.6%) | |||

| Distant metastasis | 16 (29.1%) | 3 (25.0%) | 5 (33.3%) | 1 (11.1%) | 7 (36.8%) | |||

| Death | 7 (12.7%) | 1 (6.7%) | 1 (8.3%) | 1.000 | 5 (26.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.242 | 0.449 |

gBRCA1 germline BRCA1, gBRCA2 germline BRCA2, BSO bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy

Pathogenic gBRCA1/2 mutation

There were 27 patients with pathogenic mutations in gBRCA1, and 28 patients with deleterious gBRCA2 mutations. The only male patient had nonsense mutation in gBRCA2 (p.Ile332PhefsTer17). While TNBC (n = 18, 66.7%) was significantly dominant in the patients with pathogenic gBRCA1 mutations, hormone receptor-positive breast cancer accounted for the 75% of the patients with pathogenic gBRCA2 mutations. In the gBRCA1 mutation group, patients had more TNBC compared to those in gBRCA2 mutation group (66.7% vs. 25.0%, p = 0.006). Median age, family history of breast cancer, prevalence of bilateral breast cancer were similar in both groups (Table 1).

In our study, 27 patients with pathogenic gBRCA1 mutations and 28 patients with gBRCA2 mutations were included. The most common variant was Val1833Ser (4 of 27, 14.8%), Glu1210Arg (3 of 27, 11.1%), and Tyr130Ter (3 of 27, 11.1%). Leu1780Pro, Lys307Ser, Trp1815Ter were also found in 7.4% of the patients, respectively. Among gBRCA2 mutations, Arg2494Ter (7 of 28, 25.0%) and Lys467Ter (4 of 28, 14.3%) were the most common. All mutations found in the patients are listed in Additional file 1: Table 1.

Of the 50 patients who were initially diagnosed as stage I-III, 23 patients (46.0%) experienced relapse. Three patients (6.0%) experienced local recurrence, and eleven patients (22.0%) suffered from recurrent or de novo early breast cancer in contralateral side. Two patients experienced distant metastases after local relapse, and eventually, eleven patients (22.0%) had distant metastases. Death occurred in 7 patients (12.7%). There was no difference of local or distant relapse rates between gBRCA1 and gBRCA2 mutants. Relapse-free survival of the stage I–III patients was not different between those with gBRCA1 and gBRCA2 mutations (median RFS 138 months vs. 112 months, p = 0.89). Overall survival of the patients with gBRCA1 mutation was also not significantly different from those with gBRCA2 mutation (median OS 290 months vs. not reached, p = 0.41) (Additional file 1: Fig. 1).

Targeted NGS and HR-related genes

Tissues were obtained from primary breast lesions, lymph nodes, lung, liver, and soft tissue for the targeted NGS. Most of the samples (45 of 55, 81.8%) were obtained from the breast primary lesion. About half (26 of 55, 47.3%) were obtained after lines of chemotherapy treatments. Median tumor proportion was 70%.

In the targeted NGS of 55 patients, 348 mutations were observed: 269 nonsynonymous single nucleotide variations (SNV), 30 nonsense mutations, 12 non-frameshift insertion or deletion, 4 non-frameshift substitutions, 25 frameshift insertions or deletions, and 8 splicings. There were 29 somatic BRCA2 mutations and 26 somatic BRCA1 mutations, including 3 cases without detected mutations in either BRCA1 or BRCA2 and 3 cases with mutations in both genes.

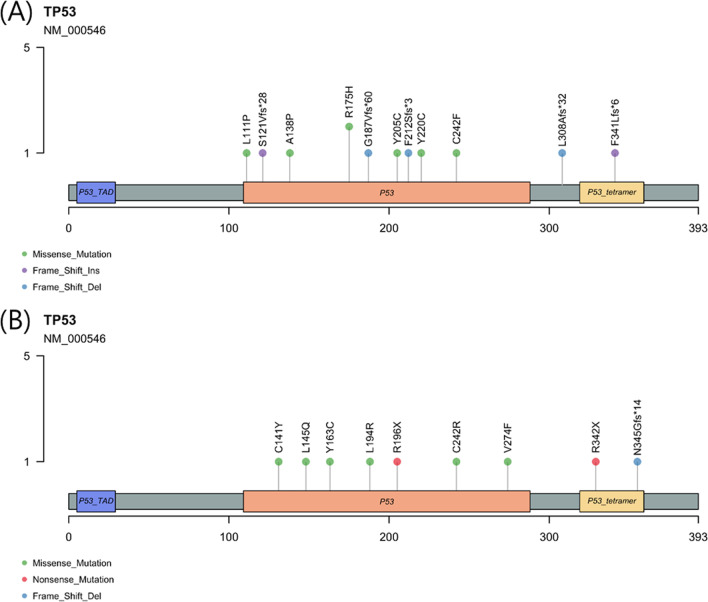

The most frequently co-mutated gene was TP53 (21 of 55, 38.1%). In the NGS analysis, mutations in TP53 gene included 6 frameshift insertion or deletion, 2 truncating mutations, and 13 nonsynonymous SNVs. Nonsynonymous SNVs mainly occurred in DNA-binding domain, while frameshift indels and stopgains occurred in oligomerization domain which interacts with other HR-related genes. Among the missense SNVs, five codons were located at DNA-binding grooves and two were at zinc binding sites (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

TP53 mutations in A gBRCA1 mutants and B gBRCA2 mutants

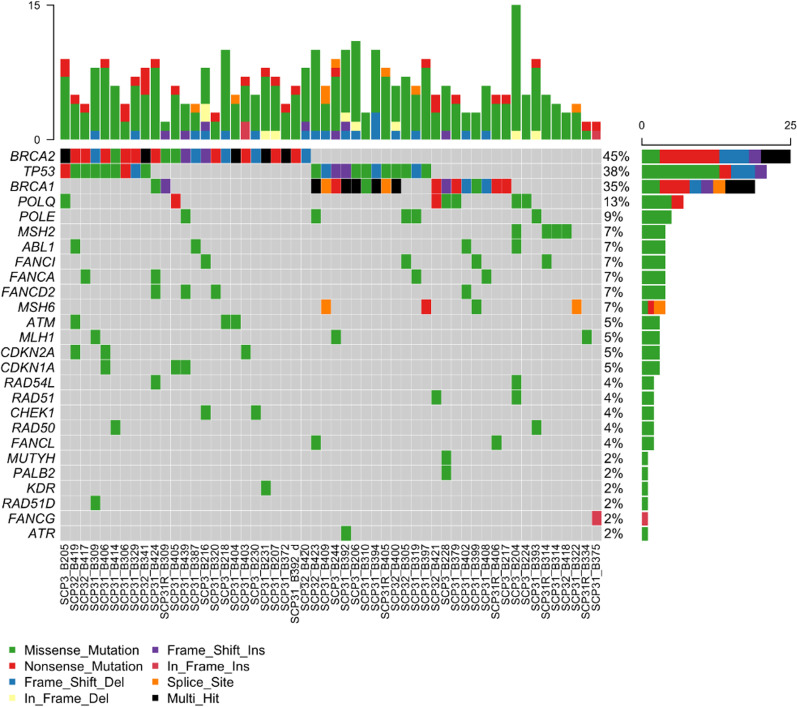

Among the HR-related genes, the most frequently mutated genes following TP53 were POLE (7 of 55, 12.7%), ABL1 (4 of 55, 7.3%), and FA-related genes, including FANCA, FANCD2, and FANCI (4 of 55, 7.3%, respectively). ATM was found exclusively in 3 patients with gBRCA2. PALB2 was observed in one patient with gBRCA1 mutation. At least one missense mutation in HR-related genes was observed in 44 cases (80.0%). One patient with gBRCA1 mutation had somatic mutation in BER-related gene, MUTYH. Somatic mutations in the mismatch-repair genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6) were also observed in 5–7% of the patients with gBRCA1/2 mutations (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Heatmap of HR-related gene mutations

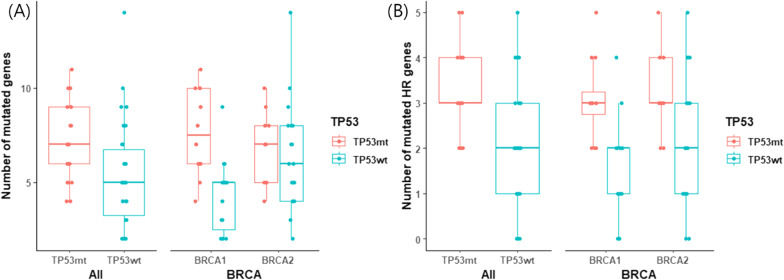

A total number of mutated genes were significantly higher in the tumors with TP53 mutations (mean 7.38 vs. 5.35, p = 0.003) (Fig. 4). In further analysis, only the number of the mutations in HR-related genes was significantly different (3.14 vs. 1.94, p < 0.001), but not that of the non-HR-related genes (4.24 vs. 3.41, p = 0.135) (Fig. 4, Additional file 1: Fig. 2). MMR genes were also not affected by the TP53 mutations (0.190 vs. 0.206, p = 0.901). Both gBRCA1- and gBRCA2-mutated tumors showed higher prevalence HR-related gene mutations in TP53 mutants compared to TP53 wild types (3.08 vs. 1.67, p = 0.003 in gBRCA1, 3.22 vs. 2.16, p = 0.041 in gBRCA2, respectively).

Fig. 4.

Number of mutated genes by TP53 mutation status A of all genes and B of HR-related genes

Clinical significance of TP53 co-mutation

The patients who had both TP53 mutation and gBRCA1/2 mutation were significantly associated with TNBC (p = 0.028) and higher Ki-67 (p = 0.001). Among the patients who had gBRCA1, the median age at the diagnosis of breast cancer was 39.5 years in those with concurrent mutation in TP53, compared to 45 years without TP53. The patients also had significantly more premenopausal status and higher Ki-67 values (p = 0.044, 0.006, respectively). Contrastingly, in the patients who had gBRCA2 and TP53 co-mutations, the median age was 45 years compared to 39 years without mutations in TP53. In these patients, the incidence of bilateral breast cancer and node-negative diseases was significantly higher than that with wild type TP53 (p = 0.035 and 0.006, respectively) (Table 1).

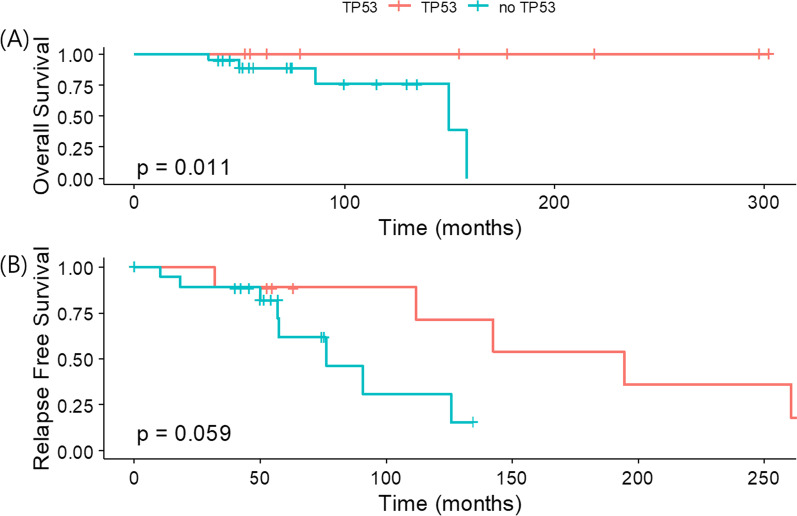

Interestingly, these gBRCA2-related patients with TP53 co-mutation also showed superior overall survival to those without TP53 mutations (p = 0.011) (Fig. 5). After the exclusion of de novo stage IV breast cancer in the gBRCA2 group, the relapse-free survival was numerically longer in those with TP53 co-mutation compared to TP53 wild types. Mutation status of TP53 did not affect the survival of patients with gBRCA1 mutations (Additional file 1: Fig. 3). Unfortunately, due to small number of deaths and total cases, none of other factors including age, family history of breast cancer, TNM staging, PR-positivity, or Ki-67 was significant in Cox-proportional hazard models (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Survivals of patients with gBRCA2mt by TP53 mutation status A overall survival and B relapse-free survival

Discussion

Clinical and genetic characteristics of breast cancer patients with pathogenic gBRCA1/2 mutations were investigated in the present study. In consistence with previous reports, about half of our patients were diagnosed before age 40, and majority were premenopausal [4, 39]. These patients also presented with other high risk features, such as family history of breast cancer, co-occurrence of contralateral breast or ovarian cancer, and high Ki-67 index [5, 7, 40]. Carriers of gBRCA1 mutations had higher prevalence of triple-negative breast cancers (TNBC), while majority of gBRCA2 mutations were associated with hormone receptor-positive breast cancers [41, 42]. However, TNM staging, histologic grade of the tumor, and lymph node metastases were not statistically different between gBRCA1-mutated and gBRCA2-mutated patients.

Previously noted gBRCA1/2 mutations in Korean ethnicity were consistently detected in our patients. The most common mutation of BRCA2, p.Arg2494X, was also detected in 12–15% of Koreans with gBRCA1/2 mutations in other studies and suggested as a founder mutation [43, 44]. Among BRCA1 variants, p.Val1833Serfs, p.Tyr130Ter, Glu1210Argfs, and p.Trp1815Ter had been frequently observed also in Asian populations [44–46]. Moreover, there were two cases of BRCA1 p.Leu1780Pro, which was also recently identified as a novel pathogenic variant [47]. None of the known or suspected founder mutations of Ashkenazi Jews [48], Caucasians [49], North African [50], Hispanic [51], or Mexican populations [52] were observed. Interestingly, the Greek founder mutation BRCA1, p.Val1833Met and one of our common variants p.Val1833Serfs had different amino acid change in same location [53]. These results highlight the ethnical differences among gBRCA1/2 mutations.

While BRCA genes are known as the strongest drivers of the breast cancers, 35 of the 93 known driver mutations were also observed in these patients [54]. The most frequently co-mutated gene was TP53, which usually undergo missense mutations in DNA-binding domains and nonsense or deletions in other domains [40, 55]. In our study, only one-third of the TP53 mutations were found in major grooves or zinc binding site of the DNA-binding domain [56]. Of all, only ten cases were included in 73 codon hotspots defined by Walker et al. [57, 58], and two cases of TP53 p.R175H were observed in our patients among six well-known hotspot codons (R175, R213, G245, R248, R273, and R282) that account for a quarter of all TP53 mutations. All in all, the codon distribution and types of TP53 mutations of gBRCA1/2 mutants had discrepancy from those in known hotspots of sporadic breast cancers [59].

TP53 acts as a tumor suppressor gene, and its mutations were strongly associated with increased chromosomal instability and higher HRD score [60]. In patients with TP53 mutations in addition to gBRCA1/2 mutations, the total number of mutated genes, especially of HR-related genes, increased. In gBRCA1 mutants, mutation of non-HR-related genes also increased, probably due to its tendency toward more frequent structural rearrangements than gBRCA2 [61].

TP53 mutations are associated with breast cancer with younger age, higher grade, advanced stages, hormone receptor negativity, enrichment of mutational signature 3, and with a high HRD index [54, 62]. In our study, the tumors with TP53 mutation were also more likely to be TNBC and have high Ki-67 values. On the other hand, age and staging at initial diagnosis of the patients with TP53 mutations were not significantly different from those with TP53 wild types. High rate of TP53 mutations observed from younger ages and early stages of the patients with gBRCA1/2 mutations implied the effect of DNA-repair deficiency and its selective pressure on tumor suppressor genes [57, 63].

The role of TP53 variants in the breast patients with pathogenic gBRCA1/2 mutation had been controversial. In our study, the improvement of overall survival was observed only in the patients with gBRCA2 mutations, despite the similar pathological complete remission rates after neoadjuvant chemotherapies, relapse rates, and de novo stage IV diseases. Those with wild-type TP53 and gBRCA2 mutation had numerically higher rate of distant metastases and deaths. As for subtypes of breast cancer, TP53 mutation has been reported to be more prevalent in basal-like subtypes [63–65]. Consistently, tumors with TP53 mutants (44.4%) were more likely to be ER-negative than those with wild-type TP53 (15.8%) in the present study. Previous study showed that, Asians were more likely to have TP53 mutations among ER-positive breast cancers than Caucasians, and TP53 mutations were associated with poor survival in ER-positive breast cancer [63]. Another study has shown that the neoadjuvant chemotherapies, regardless of the pathological complete remission rates, were more effective in the patients with TP53 mutations than wild types [66]. Taken together, one possible explanation is that initially luminal-like gBRCA2-mutated breast cancer are affected by TP53 co-mutation to become closer to basal-like entities, and more sensitive to neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy that led to less distant metastases and deaths.

Our study has limitations that arise from the retrospective design utilizing the targeted NGS for clinical purpose. Genetic mutations not targeted in the panels were difficult to be observed, including large deletions, rearrangements, chromosomal abnormalities, and methylations. Moreover, targeted NGS was done for clinical purposes and the paired biopsy with non-neoplastic tissues was difficult to be done. Small number of the patients due to the rarity of gBRCA1/2 mutations were another limitations in obtaining statistical significance. Still, our study holds its value in delineating the rare breast cancer entity with gBRCA1/2 and concomitant somatic mutations, especially in the Asian populations.

Conclusion

Our study showed genetic heterogeneity of pathogenic mutations in gBRCA1 and gBRCA2 in the Korean populations. Patterns of TP53 mutations in concomitant gBRCA1/2 mutations were distinct from those in sporadic breast cancers. Co-mutation of gBRCA1/2 and TP53 genes was associated with TNBC, high Ki-67, and higher number of mutated genes related to HR pathways. Further studies are needed to clarify the association between genetic diversity among different ethnic groups and clinical circumstances to develop treatment strategies that could lead to better survivals.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Figure S1: Survivals of patients with gBRCA1mt and gBRCA2mt (A) overall survival and (B) relapse-free survival. Figure S2: Number of mutated non-HR-related genes by TP53 mutation status. Figure S3: Survivals of gBRCA1 patients by TP53 mutation status (A) overall survival and (B) relapse-free survival. Table S1: Germline BRCA1/2 mutations

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

KHL and SAI conceptualized the study and set methodology. JK, KJ, and HJ analyzed the data. JK, JMB, MGS, TYK, DWL, GuW, SP, KHL, and SAI performed data collection. JK, KJ, HJ, KK, HY, KHL, and SAI performed formal analysis and interpretation. JK and KJ wrote the original manuscript with the help of all authors. KHL and SAI supervised the study. All authors reviewed and provided final approval of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant of the Korea Health Technology R&D Project through the Korea Health Industry Development Institute (KHIDI), funded by the Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (Grant No. HI14C1277).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

The study was approved by the Seoul National University Hospital (SNUH) Institutional Review Board (IRB No. H1509-047-702). Written informed consents were obtained from all participants before study. Clinical data were anonymized and de-identified before analysis.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Jinyong Kim and Kyeonghun Jeong have contributed equally to this work

Contributor Information

Kyung-Hun Lee, Email: kyunghunlee@snu.ac.kr.

Seock-Ah Im, Email: moisa@snu.ac.kr.

References

- 1.Couch FJ, Nathanson KL, Offit K. Two decades after BRCA: setting paradigms in personalized cancer care and prevention. Science. 2014;343(6178):1466–1470. doi: 10.1126/science.1251827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.King MC. "The race" to clone BRCA1. Science. 2014;343(6178):1462–1465. doi: 10.1126/science.1251900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riaz N, et al. Pan-cancer analysis of bi-allelic alterations in homologous recombination DNA repair genes. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):857. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-00921-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Han SH, et al. Mutation analysis of BRCA1 and BRCA2 from 793 Korean patients with sporadic breast cancer. Clin Genet. 2006;70(6):496–501. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00717.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim E-K, Park SY, Kim S-W. Clinicopathological characteristics of BRCA-associated breast cancer in Asian patients. J Pathol Transl Med. 2020;54(4):265–275. doi: 10.4132/jptm.2020.04.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kim H, Choi DH. Distribution of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in asian patients with breast cancer. J Breast Cancer. 2013;16(4):357–365. doi: 10.4048/jbc.2013.16.4.357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lang G-T, et al. The spectrum of BRCA mutations and characteristics of BRCA-associated breast cancers in China: Screening of 2,991 patients and 1,043 controls by next-generation sequencing. Int J Cancer. 2017;141(1):129–142. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abubakar M, et al. Clinicopathological and epidemiological significance of breast cancer subtype reclassification based on p53 immunohistochemical expression. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2019;5(1):20. doi: 10.1038/s41523-019-0117-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kurian AW, et al. Lifetime risks of specific breast cancer subtypes among women in four racial/ethnic groups. Breast Cancer Res. 2010;12(6):R99. doi: 10.1186/bcr2780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lord CJ, Ashworth A. The DNA damage response and cancer therapy. Nature. 2012;481(7381):287–294. doi: 10.1038/nature10760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Prakash R, et al. Homologous recombination and human health: the roles of BRCA1, BRCA2, and associated proteins. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015;7(4):a016600. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scully R, et al. Association of BRCA1 with Rad51 in mitotic and meiotic cells. Cell. 1997;88(2):265–275. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81847-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sharan SK, et al. Embryonic lethality and radiation hypersensitivity mediated by Rad51 in mice lacking Brca2. Nature. 1997;386(6627):804–810. doi: 10.1038/386804a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu LC, et al. Identification of a RING protein that can interact in vivo with the BRCA1 gene product. Nat Genet. 1996;14(4):430–440. doi: 10.1038/ng1296-430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xia B, et al. Control of BRCA2 cellular and clinical functions by a nuclear partner, PALB2. Mol Cell. 2006;22(6):719–729. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zelensky A, Kanaar R, Wyman C. Mediators of homologous DNA pairing. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6(12):a016451. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lord CJ, Ashworth A. PARP inhibitors: synthetic lethality in the clinic. Science. 2017;355(6330):1152–1158. doi: 10.1126/science.aam7344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Bono J, et al. Olaparib for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(22):2091–2102. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1911440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.González-Martín A, et al. Niraparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(25):2391–2402. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1910962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heeke AL, et al. Prevalence of homologous recombination-related gene mutations across multiple cancer types. JCO Precis Oncol. 2018;2:1–13. doi: 10.1200/PO.17.00286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Robson M, et al. BRCA-associated breast cancer in young women. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(5):1642–1649. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.5.1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davies H, et al. HRDetect is a predictor of BRCA1 and BRCA2 deficiency based on mutational signatures. Nat Med. 2017;23(4):517–525. doi: 10.1038/nm.4292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Telli ML, et al. Homologous recombination deficiency (HRD) status predicts response to standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy in patients with triple-negative or BRCA1/2 mutation-associated breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2018;168(3):625–630. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4624-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Watkins JA, et al. Genomic scars as biomarkers of homologous recombination deficiency and drug response in breast and ovarian cancers. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16(3):211. doi: 10.1186/bcr3670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Christofyllakis K, et al. Cost-effectiveness of precision cancer medicine-current challenges in the use of next generation sequencing for comprehensive tumour genomic profiling and the role of clinical utility frameworks (Review) Mol Clin Oncol. 2022;16(1):21. doi: 10.3892/mco.2021.2453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen S, et al. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(17):i884–i890. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010;26(5):589–595. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DePristo MA, et al. A framework for variation discovery and genotyping using next-generation DNA sequencing data. Nat Genet. 2011;43(5):491. doi: 10.1038/ng.806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van der Auwera GA, O'Connor BD, Safari AORMC. Genomics in the cloud : using Docker, GATK, and WDL in Terra. 1. Sebastopol: O'Reilly Media; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang K, Li M, Hakonarson H. ANNOVAR: functional annotation of genetic variants from high-throughput sequencing data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(16):e164. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lek M, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536(7616):285–291. doi: 10.1038/nature19057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Genomes Project C et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526(7571):68–74. doi: 10.1038/nature15393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karczewski KJ, et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. 2020;581(7809):434–443. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fu WQ, et al. Analysis of 6,515 exomes reveals the recent origin of most human protein-coding variants. Nature. 2013;493(7431):216–220. doi: 10.1038/nature11690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bouaoun L, et al. TP53 variations in human cancers: new lessons from the IARC TP53 database and genomics data. Hum Mutat. 2016;37(9):865–876. doi: 10.1002/humu.23035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mayakonda A, et al. Maftools: efficient and comprehensive analysis of somatic variants in cancer. Genome Res. 2018;28(11):1747–1756. doi: 10.1101/gr.239244.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bishop AJ, Schiestl RH. Homologous recombination and its role in carcinogenesis. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2002;2(2):75–85. doi: 10.1155/S1110724302204052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kassambara A, Biecek KMP, Fabian S. Survminer: drawing survival curves using ‘ggplot2’ 2021. Available from: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=survminer.

- 39.Kwong A, et al. Clinical and pathological characteristics of Chinese patients with BRCA related breast cancer. HUGO J. 2009;3(1):63–76. doi: 10.1007/s11568-010-9136-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marcus JN, et al. Hereditary breast cancer: pathobiology, prognosis, and BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene linkage. Cancer. 1996;77(4):697–709. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960215)77:4<697::AID-CNCR16>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Talhouet S, et al. Clinical outcome of breast cancer in carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations according to molecular subtypes. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):7073. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-63759-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mavaddat N, et al. Pathology of breast and ovarian cancers among BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers: results from the consortium of investigators of modifiers of BRCA1/2 (CIMBA) Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2012;21(1):134–147. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-11-0775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Han SA, et al. The Korean Hereditary Breast Cancer (KOHBRA) Study: protocols and interim report. Clin Oncol. 2011;23(7):434–441. doi: 10.1016/j.clon.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Son BH, et al. Prevalence of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in non-familial breast cancer patients with high risks in Korea: the Korean Hereditary Breast Cancer (KOHBRA) Study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133(3):1143–1152. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2001-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kang E, et al. The prevalence and spectrum of BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Korean population: recent update of the Korean Hereditary Breast Cancer (KOHBRA) study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;151(1):157–168. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3377-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sugano K, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of germline BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Japanese patients suspected to have hereditary breast/ovarian cancer. Cancer Sci. 2008;99(10):1967–1976. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00944.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Park JS, et al. Identification of a novel BRCA1 pathogenic mutation in korean patients following reclassification of BRCA1 and BRCA2 variants according to the ACMG standards and guidelines using relevant ethnic controls. Cancer Res Treat. 2017;49(4):1012–1021. doi: 10.4143/crt.2016.433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levy-Lahad E, et al. Founder BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutations in Ashkenazi Jews in Israel: frequency and differential penetrance in ovarian cancer and in breast-ovarian cancer families. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;60(5):1059–1067. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bayraktar S, et al. Genotype-phenotype correlations by ethnicity and mutation location in BRCA mutation carriers. Breast J. 2015;21(3):260–267. doi: 10.1111/tbj.12392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.ElBiad O, et al. Prevalence of specific and recurrent/founder pathogenic variants in BRCA genes in breast and ovarian cancer in North Africa. BMC Cancer. 2022;22(1):208. doi: 10.1186/s12885-022-09181-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Weitzel JN, et al. Prevalence and type of BRCA mutations in Hispanics undergoing genetic cancer risk assessment in the Southwestern United States: a report from the clinical cancer genetics community research network. J Clin Oncol. 2012;31(2):210–216. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Weitzel JN, et al. Prevalence and type of BRCA mutations in Hispanics undergoing genetic cancer risk assessment in the southwestern United States: a report from the Clinical Cancer Genetics Community Research Network. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(2):210–216. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.41.0027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Papamentzelopoulou M, et al. Prevalence and founder effect of the BRCA1 p.(Val1833Met) variant in the Greek population, with further evidence for pathogenicity and risk modification. Cancer Genet. 2019;237:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergen.2019.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nik-Zainal S, et al. Landscape of somatic mutations in 560 breast cancer whole-genome sequences. Nature. 2016;534(7605):47–54. doi: 10.1038/nature17676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Olivier M, Hollstein M, Hainaut P. TP53 mutations in human cancers: origins, consequences, and clinical use. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2010;2(1):a001008. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cho Y, et al. Crystal structure of a p53 tumor suppressor-DNA complex: understanding tumorigenic mutations. Science. 1994;265(5170):346–355. doi: 10.1126/science.8023157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Greenblatt MS, et al. TP53 mutations in breast cancer associated with BRCA1 or BRCA2 germ-line mutations: distinctive spectrum and structural distribution. Can Res. 2001;61(10):4092–4097. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Walker DR, et al. Evolutionary conservation and somatic mutation hotspot maps of p53: correlation with p53 protein structural and functional features. Oncogene. 1999;18(1):211–218. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.de Andrade KC, et al. The TP53 database: transition from the International Agency for Research on Cancer to the US National Cancer Institute. Cell Death Differ. 2022;29(5):1071–1073. doi: 10.1038/s41418-022-00976-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Takamatsu S, et al. The utility of homologous recombination deficiency biomarkers across cancer types. medRxiv, 2021: p. 2021.02.18.21251882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Retracted]

- 61.Nones K, et al. Whole-genome sequencing reveals clinically relevant insights into the aetiology of familial breast cancers. Ann Oncol. 2019;30(7):1071–1079. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdz132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Olivier M, et al. The clinical value of somatic TP53 gene mutations in 1,794 patients with breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(4):1157–1167. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Silwal-Pandit L, et al. TP53 mutation spectrum in breast cancer is subtype specific and has distinct prognostic relevance. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(13):3569–3580. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ragu ME, et al. TP53 somatic mutations in Asian breast cancer are associated with subtype-specific effects. bioRxiv, 2022: p. 2022.03.31.486643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 65.Holstege H, et al. High incidence of protein-truncating TP53 mutations in BRCA1-related breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69(8):3625–3633. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bae SY, et al. Differences in prognosis by p53 expression after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in triple-negative breast cancer. Ann Surg Treat Res. 2020;98(6):291–298. doi: 10.4174/astr.2020.98.6.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Figure S1: Survivals of patients with gBRCA1mt and gBRCA2mt (A) overall survival and (B) relapse-free survival. Figure S2: Number of mutated non-HR-related genes by TP53 mutation status. Figure S3: Survivals of gBRCA1 patients by TP53 mutation status (A) overall survival and (B) relapse-free survival. Table S1: Germline BRCA1/2 mutations

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.