Abstract

The expression of protein A (spa) is repressed by global regulatory loci sarA and agr. Although SarA may directly bind to the spa promoter to downregulate spa expression, the mechanism by which agr represses spa expression is not clearly understood. In searching for SarA homologs in the partially released genome, we found a SarA homolog, encoding a 250-amino-acid protein designated SarS, upstream of the spa gene. The expression of sarS was almost undetectable in parental strain RN6390 but was highly expressed in agr and sarA mutants, strains normally expressing high level of protein A. Interestingly, protein A expression was decreased in a sarS mutant as detected in an immunoblot but returned to near-parental levels in a complemented sarS mutant. Transcriptional fusion studies with a 158- and a 491-bp spa promoter fragment linked to the xylE reporter gene disclosed that the transcription of the spa promoter was also downregulated in the sarS mutant compared with the parental strain. Interestingly, the enhancement in spa expression in an agr mutant returned to a near-parental level in the agr sarS double mutant but not in the sarA sarS double mutant. Correlating with this divergent finding is the observation that enhanced sarS expression in an agr mutant was repressed by the sarA locus supplied in trans but not in a sarA mutant expressing RNAIII from a plasmid. Gel shift studies also revealed the specific binding of SarS to the 158-bp spa promoter. Taken together, these data indicated that the agr locus probably mediates spa repression by suppressing the transcription of sarS, an activator of spa expression. However, the pathway by which the sarA locus downregulates spa expression is sarS independent.

Staphylococcus aureus is a versatile human pathogen that can cause a variety of infections ranging from minor wound infections, pneumonia, and endocarditis to sepsis (3). The ability of S. aureus to cause a multitude of diseases has been ascribed to the array of extracellular and cell wall virulence determinants produced by this microorganism (27). The regulation of many of these virulence determinants is controlled by global regulatory loci such as sarA (previously designated as sar), agr, sae, and rot (8, 13–16, 23). These regulatory elements, in turn, exert transcriptional control of target virulence genes.

The global regulatory locus agr encodes a two-component quorum-sensing system that originates from the generation of two divergent transcripts, RNAII and RNAIII. RNAIII is the effector molecule of the agr response, which entails upregulation of extracellular protein production (e.g., alpha-toxin) and downregulation of cell wall-associated protein synthesis (e.g., protein A and fibronectin-binding proteins) during the postexponential phase (16). The RNAII transcript encodes a four-gene operon, agrBDCA, with AgrC and AgrA corresponding to the sensor and the activator proteins of a two-component regulatory system (16). Additionally, AgrD encodes a 46-residue peptide which undergoes processing to form a quorum-sensing cyclic octapeptide, probably with the aid of the agrB gene product. Upon extracellular accumulation of a critical concentration of the cyclic octapeptide, the sensor protein AgrC will become phosphorylated (19), thus leading to a second phosphorylation step of AgrA. Phosphorylated AgrA will activate the transcription of RNAIII, the agr regulatory molecule, to modulate target gene transcription (15, 23, 26).

In contrast to agr, the sarA locus upregulates the synthesis of selected extracellular (e.g., α and β hemolysins) and cell wall proteins (e.g., fibronectin-binding protein A). Like the agr locus, the sarA locus also represses the transcription of the protein A gene (spa) (7). The sarA locus, contained within a 1.2-kb fragment, is composed of three overlapping transcripts, all encoding the major 372-bp sarA gene (1). DNA-binding studies revealed that SarA, the major sarA regulatory molecule, binds to several target gene promoters, including those of agr, hla (α hemolysin gene), and spa. Accordingly, the binding of SarA to a conserved binding site present in many target gene promoters leads to an upregulation in agr and hla transcription, as well as to a downregulation in spa transcription, thus implicating SarA to be a regulatory molecule that modulates target genes via both agr-dependent and agr-independent pathways (9).

Considering the fact that both sarA and agr repress spa transcription, it seems reasonable to predict the existence of regulatory element(s) that counteracts this mode of regulation (i.e., activating spa). In searching for SarA homolog(s) in the S. aureus genome (The Institute for Genome Research [TIGR]), we came upon an open reading frame (ORF) upstream of the spa gene that shares homology with SarA. Transcriptional analysis indicated that the expression of this gene, designated sarS for a gene supplemental to SarA, is enhanced in sarA and agr mutants, while the transcription of sarA and agr loci is unaltered in a sarS mutant. Inactivation of this gene leads to a decrease in protein A expression on immunoblots. Transcriptional analyses of sarA sarS and agr sarS double mutants indicated that the agr locus likely downregulates spa transcription by repressing sarS expression, whereas the sarA locus probably suppresses protein A expression via a different mechanism. Gel shift analysis revealed that purified SarS binds to the spa promoter in a dose-dependent fashion. In contrast to the suppressive effect of sarA and agr, these data suggested that sarS activates protein A synthesis. The fact that sarS is repressible by agr and not vice versa hints at the possibility that agr may exert its effect on spa by repressing sarS expression.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, and growth media.

The bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table 1. CYGP, O3GL media (25), and tryptic soy broth were used for the growth of S. aureus strains, while Luria-Bertani medium was used to cultivate Escherichia coli. Antibiotics were used at the following concentrations: erythromycin at 5 μg/ml, kanamycin at 75 μg/ml, tetracycline at 5 μg/ml, and ampicillin at 50 μg/ml.

TABLE 1.

Strains and plasmids used in this study

| Strain or plasmid | Source or reference | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| S. aureus | ||

| RN4220 | 25 | A mutant of 8325-4 that accepts foreign DNA |

| RN6390 | 25 | Laboratory strain that maintains its hemolytic pattern when propagated on sheep erythrocyte agar (parental strain) |

| RN6911 | 26 | An agr mutant of RN6390 with a Δagr::tetM mutation |

| PC1839 | 4 | 8325-4 with a sarA::kan mutation |

| ALC184 | 7 | sarA mutant of RN6390 with pRN6735 and pI524 |

| ALC865 | 7 | RN6911 (agr mutant) with pALC862 |

| ALC1016 | This study | RN6390 with pALC1014 |

| ALC1342 | This study | A sarA mutant in which the sarA gene (nt 586 to 1107) (1) has been replaced by an ermC gene |

| ALC1794 | 9 | RN6390 with pALC1639 |

| ALC1927 | This study | A sarS mutant of RN6390 with an ermC gene into the EcoRI site of the sarS gene |

| ALC2009 | This study | ALC1927 complemented with pALC2010 |

| ALC2033 | This study | RN6390 with Δagr::tetM and sarS::ermC mutations |

| ALC2034 | This study | ALC1927 (sarS mutant) with pALC1639 |

| ALC2057 | This study | RN6390 with a sarA::kan mutation |

| ALC2067 | This study | RN6390 with sarS::ermC and sarA::kan mutations |

| ALC2115 | This study | ALC1927 (sarS mutant) with pALC1014 |

| E. coli | ||

| XL1-Blue | 21 | A host strain for cloning |

| BL21 | 21 | A host strain for the pET14b expression vector |

| Plasmids | ||

| pCR2.1 | Invitrogen | E. coli cloning vector for direct cloning of PCR products |

| pUC18 | 21 | E. coli cloning vector |

| pCL52.2 | 17 | A temperature-sensitive E. coli-S. aureus shuttle vector |

| pET14b | Novagen | Expression vector for E. coli |

| pI524 | 16 | S. aureus plasmid containing a β-lactamase repressor |

| pLC4 | 31 | A shuttle plasmid containing a promoterless xylE reporter gene |

| pRN6735 | 16 | A derivative of pC194 containing the bla promoter and two-thirds of the blaZ gene followed by a 1.5-kb RNAIII fragment lacking its promoter |

| pSK236 | 12 | A shuttle vector containing pUC19 at the HindIII site of pC194 |

| pALC672 | This study | pCR2.1 with a 161-bp sarA P3 promoter fragment |

| pALC862 | 7 | pSK236 containing the entire sarA locus with the sarA ORF and the triple promoter system |

| pALC1014 | This study | pLC4 containing a 158-bp spa promoter fragment (nt 17 to 174) (20) |

| pALC1639 | 9 | pLC4 (transcriptional fusion vector) with a 491-bp spa promoter fragment (nt 1 to 174 plus 319 bp upstream) (20) |

| pALC1883 | This study | pUC18 containing a 1.8-kb sarS fragment (nt 2925 to 1082 in contig 6207) |

| pALC1889 | This study | Temperature-sensitive shuttle plasmid pCL52.2 containing the ermC gene at the EcoRI site (nt 2616 to 2621) of the 1.8-kb sarS fragment |

| pALC2010 | This study | Shuttle plasmid pSK236 containing a 1.2-kb sarS fragment (nt 3459 to 2189 of contig 6207) |

| pALC2040 | This study | pCR2.1 with a 1,562-bp spa structural gene (nt 219 to 1780) (20). |

| pALC2043 | This study | pET14b containing the 750-bp sarS gene at the XhoI/BamHI site |

Genetic manipulations in E. coli and S. aureus.

Based on homology with sarA, the sarS gene was identified in contig 6207 in the TIGR S. aureus genome database (www.TIGR.org). To construct a sarS mutant, part of the sarS gene, together with a part of flanking sequence, was amplified by PCR with the primers 5′-AGTTTTATGTTATAAACAATCGGA-3′ and 5′-GTTGTTTCTTGTTATTTTACGAA-3′, using chromosomal DNA from strain RN6390 as the template. The 1.8-kb PCR fragment (nucleotides [nt] 2925 to 1082 in contig 6207) was cloned into pUC18 in E. coli. Taking advantage of an internal EcoRI site (nt 2616 to 2621) in the middle of the sarS coding region (nt 3098 to 2346), we cloned a ∼1.4-kb ermC fragment into this site. The fragment containing an ermC insertion into the sarS gene was cloned into the temperature-sensitive shuttle vector pCL52.2 (18), which was then transformed into RN4220 by electroporation (28), followed by transduction into RN6390 with phage φ11 as described elsewhere (8). Transductants were selected at 30°C on erythromycin- and tetracycline-containing plates.

S. aureus RN6390 harboring the recombinant pCL52.2 was grown overnight at 30°C in liquid medium in the presence of erythromycin, diluted 1:1,000 in fresh media, and propagated at 42°C, a nonpermissive temperature for the replication of pCL52.2. This cycle was repeated four times, and the cells were replicate plated onto O3GL plates containing erythromycin and erythromycin-tetracycline to select for tetracycline-sensitive but erythromycin-resistant colonies, representing mutants with double-crossovers. The mutations were confirmed by Southern hybridization with sarS and ermC probes. One clone, designated ALC1927, was selected for further study.

To complement the sarS mutation in ALC1927, we introduced a 1.2-kb PCR fragment (nt 2925 to 1082 in contig 6207) encompassing the sarS gene into the shuttle plasmid pSK236. The recombinant shuttle plasmid was first electroporated into RN4220 and then into the sarS mutant ALC1927 (8). The presence of the recombinant plasmid was confirmed by restriction mapping. The presence of the sarS transcript in the complemented mutant was confirmed by Northern blots with a sarS probe.

For the construction of the sarA sarS double mutant, we introduced the sarA::kan mutation into sarS mutant ALC1927 via a 80α lysate of a sarA insertion mutant PC1839 (with a sarA::kan mutation). As an additional control, we used a sarA deletion mutant (ALC1342) in which the sarA gene has been replaced by the ermC gene. Because of the ermC insertion, we were not able to construct a sarA sarS mutation in the ALC1342 background. Likewise, an agr sarS mutant was constructed by infecting the sarS mutant with a φ11 lysate of the agr mutant RN6911. The authenticity of these double mutants was confirmed by Southern and Northern blots with sarA and agr probes (data not shown).

Analysis of hla and spa expression in the sarS mutant and its isogenic parents.

To assess the phenotypes of the sarS mutant, we first evaluated the expression of α hemolysin and protein A, two well-known virulence determinants in S. aureus. To determine α-hemolysin expression, equivalent amounts of extracellular proteins that had been harvested at stationary phase and concentrated by 10% trichloroacetic acid precipitation were blotted onto nitrocellulose, probed with rabbit anti-α-hemolysin antibody (a gift from B. Menzies, Nashville, Tenn.) diluted 1:2,000, and then treated with the F(ab)2 fragment of goat anti-rabbit alkaline phosphatase conjugate (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, Pa.) as described previously (5). Reactive bands were visualized as described by Blake et al. (2).

To evaluate protein A production, cell wall-associated proteins were extracted from an equivalent number of S. aureus cells (from overnight cultures) with lysostaphin in a hypertonic medium (30% raffinose) to stabilize the protoplasts as described previously (7). Equivalent volumes (1 to 2 μl each) of cell wall protein extracts from 25 ml of cells (109 CFU/ml) were resolved on 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels, blotted onto nitrocellulose, and probed with chicken anti-staphylococcal protein A antibody (Accurate Chemicals, Westbury, N.Y.) at a 1:3,000 dilution. Bound antibody was detected with a 1:5,000 dilution of F(ab)2 fragment of rabbit anti-chicken immunoglobulin G conjugated to alkaline phosphatase (Jackson Immunoresearch), followed by the addition of developing substrates (2). The intensity of the protein A band was quantitated by densitometric software (SigmaGel; Jandel Scientific). The data are presented as densitometric units.

Isolation of RNA and Northern blot hybridization.

Overnight cultures of S. aureus were diluted 1:50 in CYGP and grown to mid-log (optical density at 650 nm [OD650] = 0.7), late-log (OD650 = 1.1), and early-postexponential (OD650 = 1.7) phases. The cells were pelleted and processed with a FastRNA isolation kit (Bio 101, Vista, Calif.) in combination with 0.1-mm-diameter zirconia-silica beads in a FastPrep reciprocating shaker (Bio 101) as described earlier (6). Ten or twenty micrograms of each sample was electrophoresed through a 1.5% agarose–0.66 M formaldehyde gel in morpholinepropanesulfonic acid (MOPS) running buffer (20 mM MOPS, 10 mM sodium acetate, 2 mM EDTA; pH 7.0). Blotting of RNA onto Hybond N+ membranes (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.) was performed with the Turboblotter alkaline transfer system (Schleicher & Schuell, Keene, N.H.). For the detection of specific transcripts (agr, sarA, sarS, spa, and hla), gel-purified DNA probes were radiolabeled with [α-32P]dCTP by the random-primed method (Ready-To-Go Labeling Kit; Pharmacia) and hybridized under high-stringency conditions (5). The blots were subsequently washed and autoradiographed.

Preparation of cell extracts for detection of SarA.

Cell extracts were prepared for strains RN6390 and the corresponding sarS mutant. After pelleting, the cells were resuspended in 1 ml of TEG buffer (25 mM Tris, 5 mM EGTA; pH 8), and cell extracts were prepared from lysostaphin-treated cells as described earlier (11). Cell extracts were immunoblotted onto nitrocellulose membranes as described above. For the detection of SarA, monoclonal antibody 1D1 (1:2,500 dilution) was incubated with the immunoblot for 3 h, followed by another h of incubation with a 1:10,000 dilution of goat anti-mouse alkaline phosphatase conjugate (Jackson Immunoresearch). Reactive bands were detected by developing substrates as described previously (2).

Transcriptional fusion studies of spa promoter linked to the xylE reporter gene.

A 158-bp (nt 17 to 174) (20) and a 491-bp spa promoter fragment (9) with flanking EcoRI and HindIII sites were amplified by PCR using genomic DNA of S. aureus RN6390 as the template and cloned into the TA cloning vector pCR2.1 (Invitrogen, San Diego, Calif.). The EcoRI-HindIII fragments containing the spa promoter were then cloned into shuttle plasmid pLC4 (31), generating transcriptional fusions to the xylE reporter gene. The orientation and authenticity of the promoter fragments were confirmed by restriction analysis and DNA sequencing. The recombinant plasmids were first introduced into S. aureus RN4220 by electroporation, according to the protocol of Schenk and Laddaga (28). Plasmids purified from RN4220 transformants were then electroporated into RN6390 and its isogenic sarS mutant.

For enzymatic assays of the xylE gene product, overnight cultures were diluted 1:50 or 1:100 in 250 ml of TSB containing appropriate antibiotics and shaken at 37°C and 200 rpm. Starting after 3 h of growth, 10 to 50 ml of cell culture corresponding to different OD600 values was serially removed, centrifuged, and washed twice with 1 ml of ice-cold 20 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.2). The pellets were resuspended in 500 μl of 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) containing 10% acetone and 25 μg of lysostaphin per ml, incubated for 15 min at 37°C, and then kept on ice for 5 min. Extracts were centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 50 min at 4°C to pellet cellular debris. The XylE (catechol 2,3-dioxygenase) assays were determined spectrophotometrically at 30°C in a total volume of 3 ml of 100 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) containing 100 μl of cell extract and 0.2 mM catechol as described earlier (31). The reactions were allowed to proceed for 25 min with an OD375 reading taken at the 25-min time point. One milliunit is equivalent to the formation of 1.0 nmol of 2-hydroxymuconic semialdehyde per min at 30°C. The specific activity is defined as a milliunit per milligram of cellular protein (31).

Overexpression and purification of SarS in a pET vector.

The 750-bp sarS gene was amplified by PCR using the following oligonucleotides: 5′-GCCG(CTCGAG)ATGAAATATAATAACCA-3′ and 5′-GCACTTTA(GGATCC)AGCACAC-3′. The PCR product was digested with XhoI and BamHI (restriction sites are indicated in parentheses), ligated into the expression vector pET14b (Novagen, Madison, Wis.), and transformed into the E. coli BL21(DE3).pLys.S. The resulting plasmid (pALC2043; see Table 1) contained the entire sarS coding region in frame with a N-terminal His tag. Recombinant protein expression was induced by adding ITPG (isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside; final concentration, 1 mM) to a growing culture (30°C) at OD600 of 0.5. At 3 h after induction, the cells were harvested, resuspended in binding buffer (5 mM imidazole, 0.5 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl; pH 7.9), and sonicated on ice. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 15 min, and the clarified supernatant was purified on a nickel affinity column (Novagen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The protein was eluted with the elution buffer (1 M imidazole, 0.5 M NaCl, 20 mM Tris-HCl; pH 7.9), followed by dialysis in the same buffer lacking the imidazole. The authenticity of the purified SarS protein was confirmed by N-terminal sequencing, and the size of the recombinant protein was verified by sodium dodecyl sulfate-gels stained with Coomassie blue.

Gel shift assays.

To determine if the recombinant SarS protein binds to the spa promoter, DNA fragment (158 bp) was end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP by using T4 polynucleotide kinase. Labeled fragments were incubated at room temperature for 15 min with the indicated amount of purified protein in 25 μl of binding buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 0.1 mM EDTA; 75 mM NaCl; 1 mM dithiothreitol; 10% glycerol) containing 0.5 μg of calf thymus DNA. The reaction mixtures were analyzed by nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. The band shifts were detected by exposing dried gels to film.

RESULTS

Identification of the sarS gene.

Predicated upon the SarA protein sequence, we ran the BlastP program against the TIGR S. aureus genomic database. One of the matches is located upstream of the spa gene (contig 6207, with the coding region from nt 3098 to 2349). An identical gene, designated sarS, was also found in contig 773 at the University of Oklahoma genome database. This gene, preceded by a typical Shine-Dalgarno sequence (AGGAGA) located 7 bp upstream of the initiation codon, contains a 750-bp ORF encoding a 29.9-kDa protein with a deduced pI of 9.36. A putative transcription terminal signal corresponding to a 13-bp inverted repeats (nt 2345 to 2301 in contig 6207) is located 10 bp downstream of the TAA stop codon. About 33.2% of the residues are charged. Like that of SarA, the relatively small size, a predominance of charged residues, and a basic pI of SarS are features consistent with regulatory proteins in prokaryotes (29). An alignment of SarS with SarA revealed that SarS has two regions of identity with SarA, with the first region (residues 1 to 125) having 28.3% identity and the second region having 34.5% identity (Fig. 1). The extent of homology is relatively global in nature. A survey of the GenBank database indicated that SarS is identical to the SarHI homolog recently reported by Tegmark et al. (30). Interestingly, SarS is also homologous to SarR (22), a recently described SarA homolog that downregulates SarA protein expression.

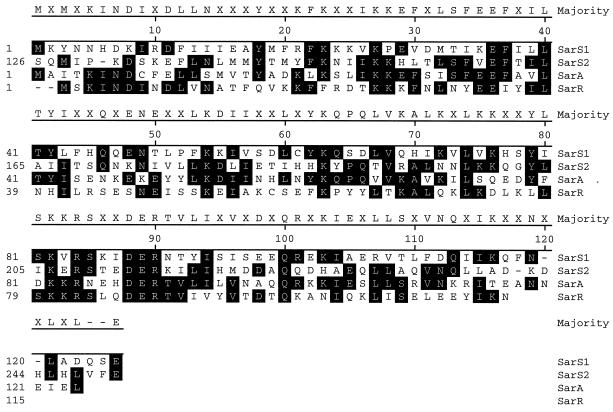

FIG. 1.

Sequence alignment of SarS, SarA, and SarR. SarS is 250 residues long. Based on regional homology, SarS can be divided into two domains (S1 and S2) of 125 residues each. The homology with SarA is higher with the C-terminal domain (34.5%) than with the N-terminal domain (28.3%). The consensus residues are in black boxes. The consensus residue, designated as the majority at each position, is assigned when at least half of the residues have the same amino acid.

Expression of sarS in RN6390 and its isogenic sarA and agr mutants.

To assess the role of sarS within the sarA/agr regulatory cascade and its mode of control on virulence gene expression, we proceeded to construct a sarS mutant by inserting an ermC gene into the EcoRI site within the sarS gene in strain RN6390 (see Materials and Methods), thus resulting in a truncation of 91 residues from the C terminus. PCR with an ermC (5′-ATGGTCTATTTCAATGGCAGTTAC) primer and a sarS primer (5′-AGGCTTTGGATGAAGCCGTTAC) outside the construct yielded a fragment consistent with the insertion of ermC into the sarS gene. Subsequent sequencing of the PCR product has verified the disruption of the sarS gene in the mutant. This was also corroborated with Southern blots with selected ermC and sarS probes (data not shown).

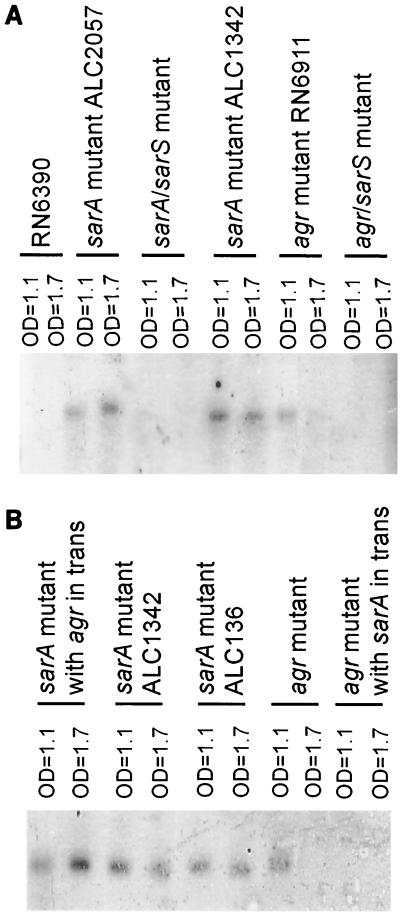

A Northern blot with a sarS probe (nt 3098 to 2349 in contig 6207), encompassing only the sarS coding region, revealed that the sarS gene is poorly transcribed in the parental strain RN6390, thus rendering the absence of the sarS gene difficult to decipher in the sarS mutant. Interestingly, the transcription of the sarS gene, sizing at 930 nt, was more prominent in both agr and sarA mutants of RN6390 (Fig. 2A). In particular, in the sarA mutant, the sarS transcript was detected at late exponential phase (OD650 = 1.1 using an 18-mm borosilicate glass tube) and was maximally transcribed during the postexponential phase (OD650 = 1.7). The transcription of sarS was also increased in the agr mutant, but the magnitude of the increase was less than that of the sarA mutant (Fig. 2A). In contrast to the sarA mutant, the agr mutant expressed the sarS transcript maximally during the late exponential phase. To assess the relative contributions of sarA and agr to sarS repression, we assayed the sarS transcript level in an agr mutant complemented with a plasmid carrying the entire sarA locus (5), as well as in a sarA mutant complemented with a fragment encoding RNAIII, the agr regulatory molecule. Remarkably, the transcription of sarS, augmented in an agr mutant, was repressed in the agr mutant clone expressing sarA in trans (Fig. 2B). However, we were not able to detect transcriptional repression of sarS in a sarA mutant expressing RNAIII of agr, thus implying a differential role for sarA and agr in repressing sarS transcription.

FIG. 2.

(A) Northern blot of the sarS transcripts in sarA, agr, sarA sarS, and agr sarS mutants. A total of 20 μg of cellular RNA was loaded onto each lane. The intensity of the 16S and 23S RNA band was found to be equivalent among lanes prior to transfer to Hybond N+ membrane. The blot was probed with a 750-bp sarS fragment (nt 2349 to 3098 in contig 6207) labeled with [α-32P]dCTP, washed, and autoradiographed. Both sarA and sarA sarS mutants contained the sarA::kan mutation. The sarA deletion mutant ALC1342 in which the sarA gene has been replaced by an ermC gene was used as an additional control. (B) Northern blot of the sarS transcript in sarA mutant (ALC136) and agr mutant with agr and sarA provided in trans, respectively. The sarA mutant was complemented with pRN6735, yielding ALC184. The plasmid pRN6735 was basally transcribed, yielding a low level of RNAIII transcript (data not shown) even in the presence of a repressor plasmid pI524. The agr mutant RN6911 was complemented with pALC862, a recombinant pSK236 containing the entire sarA locus.

We also examined the transcription of sarA and agr loci in the sarS mutant. Northern analysis of RNAII and RNAIII did not reveal any differences between the parental strain and the isogenic sarS mutant (data not shown). Likewise, the expression of three sarA transcripts (designated sarA P1, P3, and P2 transcripts) was similar between the two isogenic strains. Since SarA is encoded by these transcripts (1), we also probed for SarA expression in an immunoblot of the cell extracts of the isogenic pair (25 μg of protein in each lane) with 1D1 anti-SarA monoclonal antibody (10). Our data showed that the expression of SarA was comparable between RN6390 and its isogenic sarS mutant (data not shown). Collectively, these data implied that the transcription of sarS is repressed by the sarA and agr gene products and not vice versa.

Assessment of hla and spa in a sarS mutant of S. aureus.

Cognizant of the fact that both α-hemolysin and protein A are regulated by sarA and agr, two regulatory loci capable of repressing sarS expression, we proceeded to evaluate hla and spa expression in the sarS mutant. In an immunoblot in which equivalent amounts of extracellular proteins were blotted onto nitrocellulose and probed with rabbit anti-α-hemolysin antibody (1:2,500 dilution), we found that α-hemolysin was synthesized in the sarS mutant at a level similar to that of the parental strain. Northern blotting with an hla probe also confirmed comparable levels of gene expression between the two strains (data not shown).

To ascertain the effect of a sarS mutation on spa expression, we first assayed for transcriptional activity of 491-bp (9) and 158-bp (20) spa promoter fragments linked to the xylE reporter gene in the isogenic sarS strains. Based on XylE assays, the activity of the 491-bp spa promoter fragment was lower in the sarS mutant (29.6 ± 0.06 and 24.0 ± 0.28 mU /mg of cellular proteins at OD650 values of 1.1 and 1.7, respectively) than in its isogenic parent (53.4 ± 0.06 and 74 ± 1.3 MU/mg of cellular proteins for OD650 values of 1.1 and 1.7, respectively). A similar expression pattern was also observed with the 158-bp spa promoter fragment, but the magnitude of the XylE activity was much less in both isogenic strains (data not shown). We next probed an immunoblot, containing equivalent amounts of cell wall protein extracts of the mutant and complemented mutant, with affinity-purified chicken anti-protein A antibody (1:3,000 dilution). As displayed in Fig. 3, the expression of protein A was higher in the parental strain than in the sarS mutant. However, upon complementation with a plasmid expressing the sarS gene, the expression of protein A was increased to near parental level. These data implicated sarS to be involved in the upregulation of spa expression in S. aureus.

FIG. 3.

Immunoblot of equivalent amounts of cell wall extracts of RN6390, sarS mutant, and complemented mutant. The blot was probed with affinity-purified chicken anti-protein A antibody at a 1:3,000 dilution, followed by the addition of the appropriate conjugate and substrate. The portion of the blot labeled “5X” represents five times as much cell wall extracts as the lanes labeled as “1X.” Purified protein A (0.1 μg) was used as a positive control.

Analysis of spa transcription in agr, sarA, agr sarS, and sarA sarS mutants.

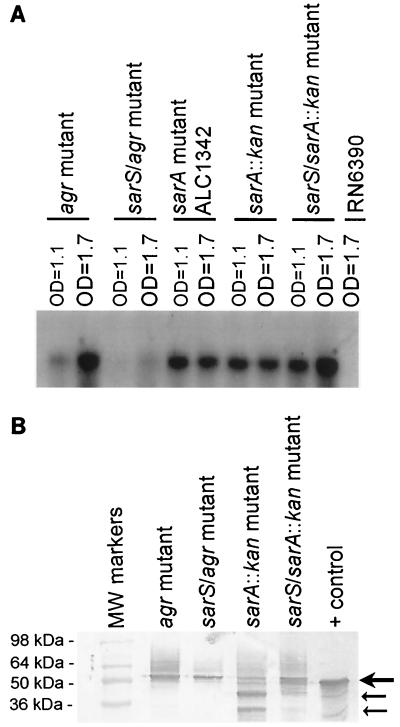

Since both sarA and agr repress sarS (see above) and spa transcription (7), we wanted to assess the relative contribution of sarS, as mediated by sarA and agr, in spa repression. For this purpose, we compared spa transcription of the sarA sarS and agr sarS double mutants to single sarA and agr mutants in the RN6390 background. In a previous study of the effect of agr and sarA on spa transcription (7), we chose strain RN6390 since this strain has a low basal level of spa transcription that can be accentuated by selective mutations. As shown in Fig. 4A, the transcription of spa, while enhanced in an agr mutant, was significantly reduced in the agr sarS double mutant, thus demonstrating that agr likely mediates spa repression by downregulating sarS. On the contrary, the upregulation in spa expression in a sarA mutant (sarA::kan) was maintained in the sarS-sarA::kan double mutant. As an additional control, the sarA deletion mutant ALC1342 also expressed a high level of spa transcription. A similar expression pattern was also observed in an immunoblot of cell wall protein A for these strains (Fig. 4B), demonstrating repression in protein A expression in the agr sarS mutant (175 densitometric units) compared with the single agr mutant (264 densitometric units). However, the contribution of sarS to the sarA mutant (i.e., the sarA sarS double mutant) was more difficult to decipher since there were two major protein A bands of lower molecular size in the sarA mutant (corresponding to densitometric units of 314 and 131 for the upper and lower bands, respectively) compared with the sarS sarA double mutant (346 densitometric units). The lower protein A bands may have been attributable to enhanced proteolytic activity in the sarA mutant, as has been previously reported (4, 8). Nevertheless, in comparing the intensity of the protein A band between the double sarS sarA mutant (346 densitometric U) and the agr mutant (264 densitometric U), we surmised that the expression of protein A in the double mutant was not significantly lower than in the single sarA mutant (two bands at 314 and 131 densitometric U). Unlike the single sarA mutant, the sarS sarA double mutant did not exhibit a protein A band of smaller molecular size. Whether sarS plays a role in modulating proteolytic activity in the sarA mutant remains to be determined. Nevertheless, these data collectively supported the notion that the agr locus, in distinction to the sarA locus, likely mediates spa repression via a sarS-dependent pathway.

FIG. 4.

(A) Northern blot of the spa transcript in agr, sarA, sarS agr, and sarS sarA mutants. The sarA and the sarS sarA mutants had the sarA::kan mutation. A total of 10 μg of RNA was applied to each lane. The blot was probed with a 1,562-bp spa fragment (nt 219 to 1780) (20). The parental strain RN6390 was a low protein A producer, with a very reduced level of spa transcription (7). The sarA deletion mutant ALC1342 served as a positive control. (B) Immunoblot of cell wall extracts of agr, sarA, sarS agr, and sarS sarA mutants probed with chicken anti-protein A antibody. Equivalent amount of cell wall extracts was applied to each lane. The positive control is purified protein A (0.1 μg). The big arrow points to intact protein A, while the two smaller arrows highlight degraded protein A fragments in the sarA::kan mutant (ALC2057).

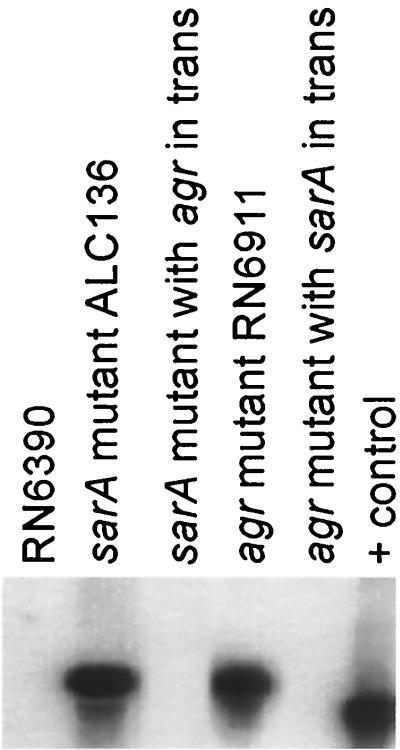

To corroborate the view that agr and sarA mediate spa repression via different pathways, we determined spa transcription in an agr mutant complemented with a shuttle plasmid carrying the entire sarA locus in trans, as well as in a sarA mutant with a plasmid expressing RNAIII. Although this approach represented a higher gene dosage than at the physiologic level, the result of this experiment, coupled with those of sarS expression, provide additional evidence for the regulatory linkage between agr and spa, using SarS as an intermediary. Accordingly, the transcription of spa in an agr mutant with sarA provided in trans (Fig. 5), as with the expression of sarS (Fig. 2B), was repressed compared to the agr mutant control. In contrast, a sarA mutant with agr expressed in trans, while maintaining an elevated level of sarS transcription compared with the parent (Fig. 2B), was still able to repress spa transcription (Fig. 5). Taken together, our results clearly indicated that sarA and agr repress spa transcription via divergent pathways, with agr being dependent on sarS, while the effect of sarA on spa is sarS independent.

FIG. 5.

Northern blot of the spa transcript in sarA and agr mutants, with agr and sarA provided in trans, respectively. The strains used in this blot are identical to those in Fig. 2B. The positive control is a plasmid (pCR2.1) carrying a 1,562-bp spa fragment (nt 219 to 1780) (20).

Gel shift assay of SarS with the spa promoter fragment.

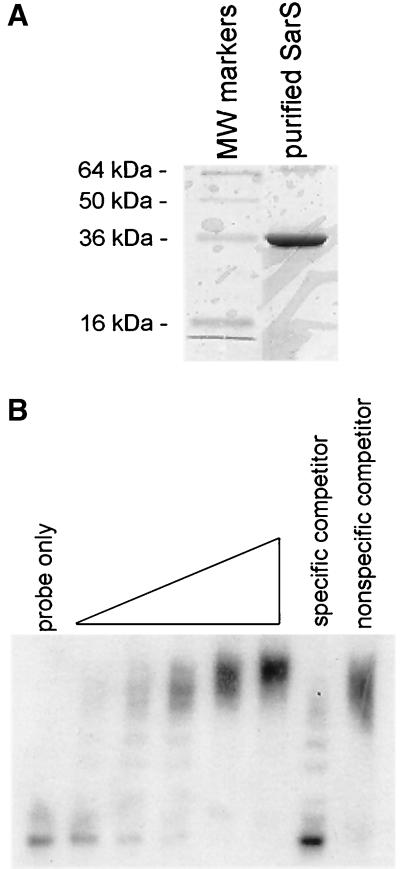

Recognizing that the sarS gene product may be an activator of protein A synthesis, we proceeded to evaluate the binding of the SarS protein to the spa promoter. For this experiment, we cloned the sarS gene into the pET14b expression vector (Novagen, Madison, Wis.) in E. coli BL21. SarS was then overexpressed in inducing conditions with 1 mM IPTG and purified with a nickel affinity column from the crude cell lysate according to the manufacturer's instructions. SarS, as eluted from the column, was essentially homogeneous (>95%) (Fig. 6A). Using purified SarS protein, we conducted gel shift assays of SarS with a 158-bp spa promoter fragment (nt 17 to 174) (20). As displayed in Fig. 6B, SarS was able to retard the mobility of the spa promoter fragment in a dose-dependent fashion. Notably, the laddering pattern in the gel shift assay is consistent with either multimers of SarS binding to the spa promoter or multiple binding sites on the spa promoter or both. In competition assays with unlabeled spa promoter fragment, the gel retarding activity of SarS was abolished, thus demonstrating the specificity of the binding.

FIG. 6.

(A) Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of SarS purified from the pET14b expression vector. About 5 μg of purified SarS protein was applied to the lane. The gel was stained with Coomassie blue. (B) Gel shift assay of purified SarS with a 158-bp spa promoter fragment (nt 17 to 174) (20). The spa promoter fragment was end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP. About 25,000 cpm was used in each lane. Increasing concentrations of purified SarS (0.125, 0.25, 0.5, 1, and 2 μg of SarS) were used in the lanes. The specific competitor was the cold unlabeled 158-bp spa promoter. The nonspecific competitor was a 161-bp sarA P3 promoter fragment (nt 365 to 525) (1).

DISCUSSION

In prior studies with sarA and agr in S. aureus, it was observed that both of these regulatory loci play important roles in repressing spa transcription during the postexponential phase. Thus, the synthesis of protein A occurs primarily during the exponential phase and is repressed postexponentially. Predicated upon this observation, it seems reasonable to hypothesize that an activator of protein A synthesis likely exists within the staphylococcal genome. In searching the partially released genome for homologs of SarA, the major sarA regulatory molecule, we found an ORF encoding a SarA homolog (SarS) upstream of spa. In contrast to SarA (124 residues), the longer SarS protein (250 residues) can be divided into two SarA-homologous domains of 125 residues each. The C-terminal domain of SarS appears to share a high degree of similarity with SarA (34.5 identity versus 28.3% for the N-terminal domain). The SarS protein, like SarA, has a basic pI and a high percentage of charged residues (33.2 versus 33% for SarA), features consistent with DNA-binding proteins in prokaryotes. Indeed, gel shift studies of purified SarS with a 158-bp spa promoter fragment supported the notion that SarS is likely a DNA-binding protein, modulating the transcription of the spa gene.

In searching the literature, we found that SarS is identical to SarH1 recently reported by Tegmark et al. (30). Using a fragment encompassing only the 750-bp sarS coding region as a probe, we were only able to detect a single 930-nt sarS transcript as opposed to the three transcriptional units (1.0, 1.5, and 2.9 kb) described in those earlier studies. This transcript likely corresponds to the most prominent transcript reported by Tegmark et al. (30). It is not immediately apparent why such differences in transcription exist between our studies and theirs. We surmise that the hybridization (65°C) and washing (60°C with 0.1× SSC [1× SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate]) conditions in our Northern blot studies might be more stringent. It is also plausible that the larger but weaker bands in their study may be cross-hybridizing bands. Alternatively, the smaller 1.5-kb band may be a processed product from the larger 2.9-kb transcript. In any event, in the absence of additional primer extension data (for the 2.9-kb transcript) and transcriptional fusion studies of the putative promoters for the 1.5- and 2.9-kb transcripts, it is not certain if other promoters are part of the sarS operon.

Despite differences in sarS transcriptional patterns between the two studies, we confirmed that sarS is repressed by sarA and agr. However, the mode of sarS repression, as revealed by our data, differed between the two global regulatory loci. More specifically, inactivation of sarA yielded a higher level of sarS expression on Northern blots than that of the agr mutant (Fig. 2A). Additional Northern blot studies divulged that the elevated sarS level in an agr mutant can be repressed by a plasmid supplying sarA in trans. In contrast, the sarS level remained high in a sarA mutant even when a plasmid encoding RNAIII was present. More importantly, despite a dissimilarity in the sarS level, spa transcription was repressed in the agr mutant with sarA supplied in trans as well as in the sarA mutant expressing RNAIII from a plasmid source. Although the gene dosage (i.e., sarA or RNAIII) in these studies is not provided at the single-copy level, we contend that the expression of sarA or agr from multiple-copy plasmid would still permit us to decipher the putative interactive pathway, in particular in a situation where the putative gene (e.g., sarS) is expressed at such a low level that it may easily be missed by routine Northern blot analysis. Thus, a persistently high sarS level in the sarA mutant expressing RNAIII in trans (Fig. 2B), coupled with an effective repression of spa (Fig. 5), hinted at the differential roles in spa regulation between sarA and agr.

Several lines of experimental evidence suggested a role for sarS as an activator of protein A synthesis. First, in complementation studies of the sarS mutant, we showed by immunoblots that the diminution in protein A synthesis was restored by a shuttle plasmid carrying sarS. Second, we confirmed by transcriptional fusion studies of a spa promoter linked to the xylE reporter gene that spa promoter activity was indeed reduced in a sarS mutant. Third, gel shift studies have validated the notion that SarS can bind directly to the spa promoter in a dose-dependent fashion. Fourth, we extended our observation by Northern analyses that the upregulation in spa transcription in an agr mutant, presumably mediated by a derepression of sarS, was abolished in an agr sarS double mutant, thus implicating the role of sarS in activating spa transcription in an agr mutant. However, contrary to the data of Tegmark et al., we found that spa transcription in a sarA sarS double mutant, as with a single sarA mutant, remained elevated. Thus, despite the experimental observation that sarS is derepressed in a sarA mutant, the continued augmentation in spa transcription in a sarA sarS double mutant implied that the sarA locus likely represses protein A synthesis via a SarS-independent pathway. In this regard, our recent finding that SarA, the major sarA regulatory molecule, can directly bind to a consensus recognition sequence upstream of spa promoter to downregulate spa transcription would provide an explanation for an alternative mechanism for direct SarA-mediated spa repression (9). Alternatively, other intermediate factor(s) controlled by sarA or other factors that act in conjunction with SarS may play a role in sarA-mediated spa repression. It is also plausible that these “controlling factors” may be mediated via agr, since RNAIII supplied in trans in a significant gene dosage in a sarA mutant could also suppress spa transcription (Fig. 5). Nonetheless, we are left to offer an explanation for the high level of sarS expression in a sarA mutant. Perhaps, it may be reasonable to interpret the upregulation in sarS in terms of hla repression, since Tegmark et al. found that a sarA sarH1 (i.e., sarA sarS) mutant, as opposed to a single sarA mutant, exhibited an upregulation in hla transcription.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Simon Foster for strain PC1839 and Tom Kirn for assisting with protein alignment. Access to the S. aureus genome database at TIGR and at the University of Oklahoma is gratefully acknowledged.

This work was partially supported by NIH grant AI37142.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bayer M G, Heinrichs J H, Cheung A L. The molecular architecture of the sar locus in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1996;178:4563–4570. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.15.4563-4570.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blake M S, Johnston K H, Russell-Jones G J, Gotschlich E C. A rapid sensitive method for detection of alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-antibody on Western blots. Anal Biochem. 1984;136:175–179. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(84)90320-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boyce J M. Epidemiology and prevention of nosocomial infections. In: Crossley K B, Archer G L, editors. The staphylococci in human disease. New York, N.Y: Churchill Livingstone; 1997. pp. 309–329. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan P F, Foster S J. Role of SarA in virulence determinant production and environmental signal transduction in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:6232–6241. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.23.6232-6241.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheung A L, Bayer M G, Heinrichs J H. sar genetic determinants necessary for transcription of RNAII and RNAIII in the agr locus of Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1997;179:3963–3971. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.12.3963-3971.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheung A L, Eberhardt K, Fischetti V A. A method to isolate RNA from gram-positive bacteria and mycobacteria. Anal Biochem. 1994;222:511–514. doi: 10.1006/abio.1994.1528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheung, A. L., K. Eberhardt, and J. H. Heinrichs. 1997. Regulation of protein A synthesis by the sar and agr loci of Staphylococcus aureus. Infect. Immun. 2243–2249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Cheung A L, Koomey J M, Butler C A, Projan S J, Fischetti V A. Regulation of exoprotein expression in Staphylococcus aureus by a locus (sar) distinct from agr. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:6462–6466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chien C-T, Manna A C, Projan S J, Cheung A L. SarA, a global regulator of virulence determinants in Staphylococcus aureus, binds to a conserved motif essential for sar dependent gene regulation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:37169–37176. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chien Y T, Manna A C, Cheung A L. SarA level is a determinant of agr activation in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 1998;31:991–1001. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.01126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chien Y, Cheung A L. Molecular interactions between two global regulators, sar and agr, in Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem. 1998;237:2645–2652. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.5.2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Compagnone-Post P, Malyankar U, Khan S A. Role of host factors in the regulation of the enterotoxin B gene. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:1827–1830. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.5.1827-1830.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giraudo A T, Cheung A L, Nagel R. The sae locus of Staphylococcus aureus controls exoprotein synthesis at the transcriptional level. Arch Microbiol. 1997;168:53–58. doi: 10.1007/s002030050469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giraudo A T, Raspanti C G, Calzolari A, Nagel R. Characterization of a Tn551 mutant of Staphylococcus aureus defective in the production of several exoproteins. Can J Microbiol. 1996;40:677–681. doi: 10.1139/m94-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Janzon L, Arvidson S. The role of the δ-hemolysin gene (hld) in the regulation of virulence genes by the accessory gene regulator (agr) in Staphylococcus aureus. EMBO J. 1990;9:1391–1399. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb08254.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kornblum J, Kreiswirth B, Projan S J, Ross H, Novick R P. Agr: a polycistronic locus regulating exoprotein synthesis in Staphylococcus aureus. In: Novick R P, editor. Molecular biology of the staphylococci. New York, N.Y: VCH Publishers; 1990. pp. 373–402. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee C Y. Cloning of genes affecting capsule expression in Staphylococcus aureus strain M. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:1515–1522. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb00872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lin W S, Cunneen T, Lee C Y. Sequence analysis and molecular characterization of genes required for the biosynthesis of type 1 capsular polysaccharide in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:7005–7016. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.22.7005-7016.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lina G, Jarraud S, Ji G, Greenland T, Pedraza A, Etienne J, Novick R P, Vandenesch F. Transmembrane topology and histidine protein kinase activity of AgrC, the agr signal receptor in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 1998;28:655–662. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1998.00830.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Löfdahl S, Guss B, Uhlen M, Philipson L, Lindberg M. Gene for staphylococcal protein A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:697–701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.3.697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maniatis T, Fritsch E F, Sambrook J. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manna A, Cheung A L. Characterization of sarR, a modulator of sar expression in Staphylococcus aureus. Infect Immun. 2001;69:885–896. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.2.885-896.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McNamara P J, Milligan-Monroe K C, Khalili S, Proctor R A. Identification, cloning, and initial characterization of rot, a locus encoding a regulator of virulence factor expression in Staphylococcus aureus. J Bacteriol. 2000;182:3197–3203. doi: 10.1128/jb.182.11.3197-3203.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Novick R P, Projan S J, Kornblum J, Ross H F, Ji G, Kreiswirth B, Vandenesch F, Moghazeh S. The agr P2 operon: an autocatalytic sensory transduction system in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Gen Genet. 1995;248:446–458. doi: 10.1007/BF02191645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Novick R P. The staphylococcus as a molecular genetic system. In: Novick R P, editor. Molecular biology of the staphylococci. New York, N.Y: VCH Publishers; 1990. pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Novick R P, Ross H F, Projan S J, Kornblum J, Kreiswirth B, Moghazeh S. Synthesis of staphylococcal virulence factors is controlled by a regulatory RNA molecule. EMBO J. 1993;12:3967–3977. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb06074.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Projan S J, Novick R P. The molecular basis of pathogenicity. In: Crossley K B, Archer G L, editors. The staphylococci in human disease. New York, N.Y: Churchill Livingstone; 1997. pp. 55–81. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schenk S, Laddaga R A. Improved method for electroporation of Staphylococcus aureus. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1992;94:133–138. doi: 10.1016/0378-1097(92)90596-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smith I. Regulatory proteins that control late-growth development. In: Sonenshein A L, Hoch J A, Losick R, editors. Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacteria. Washington, D.C.: ASM Press; 1993. pp. 785–800. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tegmark K, Karlsson A, Arvidson S. Identification and characterization of SarH1, a new global regulator of virulence gene expression in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:398–409. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zukowski M M, Gaffney D G, Speck D, Kauffman M, Findeli A, Wisecup A, Lecocq J P. Chromogenic identification of genetic regulatory signals in Bacillus subtilis based on expression of a cloned Pseudomonas gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:1101–1105. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.4.1101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]