1. Introduction

The promotion of exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) during the first six months of life is a central component of child survival and development strategies due to the indisputable nutritional and immunological benefits of breastmilk (Betran et al., 2001; Black et al., 2008; Jones et al., 2003; Lu & Costello, 2000; Victora et al., 2008; Victora et al., 2016; Victora et al., 1987). Compared to providing infants with breastmilk substitutes in addition to breastmilk (referred to as mixed feeding), EBF is associated with reduced infectious morbidity, diarrhea- and pneumonia-related mortality, and all-cause mortality (Betran et al., 2001; Black et al., 2008). EBF has also been associated with improvements in early cognitive development and intelligence scores during adolescence, demonstrating a dose-response effect of improved cognition with greater breastfeeding duration (Eickmann et al., 2007; Horta et al., 2015; Koh, 2017; Kramer et al., 2008). Given that intelligence is associated with economic productivity in adulthood, early introduction of infant formula may jeopardize both child health in the short term as well as economic well-being over the long term (Rollins et al., 2016).

Epidemiologic studies aiming to explain suboptimal breastfeeding behaviors have centered on discrete, individual-level determinants. Maternal socio-demographic characteristics that have been associated with lower likelihood of EBF include higher educational achievement, older age, and primiparity (Hruschka et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2014; Matias et al., 2012; Oliveira et al., 2017; Patil et al., 2015). Maternal employment outside of the home has been identified as a key barrier to EBF, especially in low-resource settings where women often work in the informal sector and therefore lack access to workplace protections and maternity leave (Brauner-Otto et al., 2019; Ogunlesi, 2010; Olayemi et al., 2007; Perez-Escamilla et al., 1995; Safari et al., 2013; Seid et al., 2013; Setegn et al., 2012; Yeneabat et al., 2014). A number of maternal psychological factors have also been positively associated with EBF, including breastfeeding intentions, self-efficacy in one’s ability to breastfeed, and greater levels of knowledge of EBF duration, benefits, and/or best practices (Babakazo et al., 2015; Egata et al., 2013; Maonga et al., 2016; Perez-Escamilla et al., 1995; Seid et al., 2013).

While this focus on individual-level determinants may help to identify target groups for intervention planning, it obscures the influence of the social, economic, and institutional factors that create the context for infant feeding. The political economy of health perspective conceptualizes illness and unhealthy behaviors as the result of power relations and social orders (Minkler et al., 1994). Health disparities are rooted in the unequal distribution of resources among different groups in society, which ultimately restricts individual agency (Navarro, 2009; Restivo, 2005). From this perspective, poor infant health outcomes are the consequence of a spectrum of political, economic, and health systems factors acting alone or in combination. At the most proximate level, the primary biomedical causes of infant morbidity—malnutrition and enteric infections—result from infants’ dietary adequacy and their ingestion of fecal pathogens (Guerrant et al., 2008; Millard, 1994). Exposure to these risk factors are determined by a set of caregiving practices that include breastfeeding (initiation, exclusivity, and overall duration), complementary feeding (quality of foods, dietary diversity, and frequency of feeding), and hygiene behaviors (hand-washing with soap and food hygiene, among others) (Stewart et al., 2013). Caregiving practices are often constrained by aspects of the immediate environment and living conditions, such as food insecurity or the household availability of safe water. This immediate context is shaped by broader “macro-level structures”—such as food prices, investments in water and sanitation infrastructure, and resource allocation for healthcare services—that ultimately determine what is possible for caregivers to achieve (Minkler et al., 1994).

Infant formula producers are a tangible link between larger political and economic interests and suboptimal breastfeeding practices in resource-poor settings. With sales of breastmilk substitutes stagnating in high-income countries, the formula industry has recently focused on “emerging markets” in low- and middle-income countries (Piwoz & Huffman, 2015). In 2014, global sales of formula amounted to $44.8 billion, and this number continues to rise (Rollins et al., 2016). This market growth has accompanied increased investments in formula marketing activities, which likely exceed governmental funding for breastfeeding promotion (Lutter, 2013). In addition to direct-to-consumer marketing through television advertisements, home visits, and social media, the health system commonly markets formula brands (Piwoz & Huffman, 2015). Substantial evidence indicates that formula manufacturers and distributors incentivize health providers through gifts featuring company logos, travel stipends, and free formula, which give rise to product promotion within the health services setting (Bueno-Gutierrez & Chantry, 2015; Save the Children, 2013a, b; Hernandez-Cordero et al., 2018; Ministerio de Salud Pública, 2012; Taylor, 1998).

Formula companies also make targeted efforts to influence local infant feeding policies. In response to international efforts to regulate industry activities, industry lobbyists have marketed directly to policy makers. The International Code of Marketing of Breastmilk Substitutes (referred to as “the Code”) was established in 1981 to provide a framework for restricting commercial formula promotion through the health system and by healthcare providers in addition to its direct promotion to mothers (WHO, 1981). The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative was launched in 1991 to motivate birthing facilities to implement 10 key interventions to support breastfeeding that complement the Code (Saadeh & Akre, 1996; WHO/UNICEF, 1991). Given that national adoption of the Code is voluntary, formula companies have aimed to deter or weaken its legislation in several low- and middle-income countries (Brady, 2012; Save the Children, 2013a; Hernandez-Cordero et al., 2018; Kean, 2014; Perez-Escamilla et al., 2012; Robinson et al., 2018).

In Peru, challenges to optimal breastfeeding practices remain, despite high levels of regulatory policy implementation. The Code was enacted into Peruvian law in 1982, almost immediately after its original publication, making Peru a leading country in its adoption. Currently, Peru is one of only eight of the 35 WHO Member States in the Americas region that has enacted legislation on all provisions of the Code (WHO, 2018). Throughout the country, 91 (36%) of hospitals received baby-friendly accreditation during the 1990s (Lutter et al., 2011). Rates of EBF for infants under six months of age increased markedly during the 1980s and 1990s following this legislation, along with concerted efforts from the Ministry of Health to train health workers to support breastfeeding (INEI, 1988, 1992).

Nonetheless, progress has slowed since 2000, according to Peru’s Demographic and Health Surveys. The percentage of infants under two months of age exclusively breastfed increased from 52.2% to 74.7% between 1992 and 2000, yet fell to 70.6% in 2014 (INEI, 1992, 2001, 2015). Median duration of any breastfeeding has also reverted to lower levels, increasing by 5.4 months between 1986 and 2000 (from 16.3 to 21.7 months of age), but then declining to 20.8 months in 2014 (INEI, 1988, 2001, 2015). In turn, rates of mixed feeding continue to rise, especially during the first two months of life (from 17.2% in 2004 to 25.1% in 2014) (INEI, 2006, 2015). Such changes are most pronounced in urban and peri-urban areas. In metropolitan Lima, which consists of 50 districts, including multiple peri-urban settlements, median EBF duration was 0.7 months in 2014, as compared to the country-level figure of 4.6 months (INEI, 2015).

In light of these downwards trends, the current study contextualizes Peruvian women’s infant feeding practices within a broader framework that includes formula marketing activities and the delivery of healthcare services. We examine health sector influences on decisions surrounding infant feeding in a shantytown community outside of Lima, Peru. The information conveyed during health facility visits competes with advice that women receive from a number of other actors, including male partners, elders, and members of one’s social network. When confronted with different and often contradictory messages, individuals’ interpretations are often determined by the information sources’ underlying traits, in addition to or in place of reflection on the message content itself (McCroskey & Teven, 1999; Pornpitakpan, 2004). Source credibility theory, as described by McCroskey and Teven (1999), posits that these traits include the source’s perceived trustworthiness, expertise, and “goodwill” or caring nature. The measurement of these dimensions may facilitate an understanding of how the advice offered by health providers shape mothers’ infant feeding practices.

The political economy of health perspective and source credibility theory offer valuable tools for critically analyzing infant feeding trends among vulnerable families in peri-urban Peru. Guided by these frameworks, this study employed quantitative and qualitative methods to (1) characterize patterns of mixed feeding during infants’ first two months of life, and (2) evaluate how interactions among health providers, formula company representatives, and mothers shape those practices.

2. Method

2.1. Study Site

This research was conducted in the district of Villa El Salvador, a vast shantytown (pueblo joven) outside of Lima, Peru. First settled in the 1970s by migrants from the Andean highlands seeking refuge from Lima’s crowded living conditions, Villa El Salvador has emerged as a largely self-sufficient district with a current population of approximately 380,000 (INEI, 2007). This study was nested within a newborn cohort study, led by Johns Hopkins University in collaboration with Universidad Peruana Cayetano Heredia, which aims to characterize the epidemiology of norovirus and sapovirus in children. The study began in 2016 and is being undertaken in four of the district’s 10 sectors, which include well established communities, as well as young, provisional settlements. The cohort study provided the longitudinal data on infant feeding practices used in our analyses; semi-structured questionnaires and in-depth interviews (IDIs) were conducted for the present study.

Within Peru’s public health system, low-income populations receive health services through a government-sponsored insurance program. Antenatal, postnatal, and well-baby services are delivered through community health posts staffed primarily by nurses and one doctor per facility. Larger public health centers (Centros Materno-Infantiles) also provide these services to some communities, along with delivery care for low-risk pregnancies. Government-funded hospitals provide delivery care for low-risk, high-risk, and emergency cases. Services are also provided by private clinics and facilities run by EsSalud, an agency that provides health insurance to formal-sector workers and their families.

2.2. Participants and Sample Selection

Primary study participants were mothers enrolled in the broader cohort study (N=299) by March 2017. This cohort was selected through population-based screening in which field workers visited each house in the study communities to ask if anyone in the household was pregnant or had a child under 28 days of age. Cohort study enrollment took place from January 2016 through May 2017; women and their children were enrolled in a staggered fashion, approximately 20–25 dyads per months, to control for seasonality. Very low birth weight (<1500 g) newborns and those with a severe chronic, congenital, or neonatal disease were not eligible for inclusion in the cohort study; aside from these exclusion criteria, study participants were representative of the study site’s general population. During the two-year follow-up period for each child, field workers conducted daily surveillance via home visits and collected weekly stool, monthly saliva, and twice-yearly blood samples from the children.

For the present study, all cohort study participants with a child at least 60 days old upon initiation of data collection in March 2017 were eligible to participate. By that time, 41 of the original 299 cohort study participants had been lost to follow-up. Of the remaining 258 participants, 218 met the inclusion criteria, as 40 participants had children less than 60 days of age. An additional four participants were excluded from our analyses because data on infant birthweight were missing (i.e., not recorded in child’s health card and mother could not recall it) (Figure 1). Enrollment characteristics of the 44 cohort study participants who were excluded from our analysis but not lost to follow-up were comparable to those included, based on t-tests and Fisher’s exact tests with a p-value cutoff of 0.05.

Fig. 1.

CONSORT diagram of mothers recruited for study activities.

A sub-set of 29 mothers was recruited for IDIs. Cohort study participants who were currently practicing mixed feeding were eligible for participation in the IDIs and were identified through weekly reviews of the field workers’ documentation of feeding practices in their surveillance records starting in March 2017. Interview participants were then selected purposively to ensure that they represented the four geographical sectors and the range of socioeconomic groups engaged in the cohort study; a minimum of five participants were recruited from each sector. Field workers recruited IDI participants during home visits by explaining that a member of the research team wanted to learn more about their experiences with infant feeding and describing the interview procedures. A sample size of 29 mothers enabled us to arrive at a rich understanding of the decision-making processes of interest while also reaching theoretical saturation on key themes (Sandelowski, 1995).

In addition, we recruited seven local health providers working in antenatal, postnatal, and/or well-baby care settings to serve as key informants, given their relevance to the topics of interest. Based on questionnaire data, we determined that cohort study participants most commonly sought antenatal, postnatal, and well-baby services from the four community health posts located in the study site’s four sectors as well as two larger public health centers located directly outside of the study site. We recruited at least one provider from each of these facilities. After receiving formal authorization from the Regional Health Directorate, the first author and field supervisor spoke with the head of each facility to obtain approval and identify the specific nurses or doctors who were familiar with the study topics. Interviews were then scheduled directly with those individuals. The health facilities included in the study were not certified as baby-friendly at the time of data collection.

2.3. Data Collection

Semi-structured questionnaires and IDIs were conducted concurrently with the ongoing cohort study procedures from March through October 2017. Data were collected by the cohort study’s field workers and the first author. Prior to joining the field team, all field workers underwent a one-month training on data collection procedures for the cohort study and general research standards. Field workers were provided with additional training on the instruments used for the present study, which included careful review of the Manual of Operations, mock interviews, and field testing. All data collection instruments developed for the present study were informed by preliminary fieldwork and reviewed by field workers to ensure their cultural relevance.

Infant feeding surveillance.

To characterize infant feeding practices, we drew on data collected through the cohort study’s daily surveillance activities. Trained field workers conduct home visits six days per week to record gastrointestinal and respiratory symptoms, number and consistency of bowel movements, and breastfeeding status over the past 24 hours, based on caregiver self-report. The presence of “exclusive breastfeeding” was defined as the consumption of only breastmilk with no other food or liquid, including water, over the prior 24-hour period, with the exception of oral medicines or drops. The presence of “mixed feeding” was defined as the intake of formula or other milks in addition to breastmilk and without any other food or liquid during the previous day. “Complementary feeding” was defined as the consumption of solid or semi-solid foods with or without breastmilk, formula, or other milks. Field workers documented this information manually in a daily log that was digitally entered at the end of each month.

Semi-structured questionnaires.

Two semi-structured questionnaires were administered cross-sectionally during the field workers’ home visits. The first of these questionnaires gathered relevant socio-demographic data including parity, civil status, maternal employment status, and birthweight (abstracted from the child’s health card when available or otherwise based on recall). The second questionnaire assessed childbirth delivery mode (vaginal, cesarean), the types of health facilities visited for delivery and well-baby care, and information sources related to infant feeding, including whether a mother had been recommended formula use by a health provider or a member of one’s social network (family members, friends, or neighbors). If the participant reported having received a formula recommendation from a health provider, then the field worker asked several follow-up questions, including the type of provider, whether it was a verbal recommendation only or accompanied by a written prescription, and the health facility where the exchange(s) took place. Participants who mentioned a written prescription were asked to produce it, if possible and were asked the age of their infant at the time of receiving the prescription. Other socio-demographic factors were captured upon cohort study enrollment, including maternal age, education, household characteristics, assets, and food insecurity based on the United States Agency for International Development’s Household Food Insecurity Access Scale.

In-depth interviews.

IDIs explored mothers’ experiences and decision-making processes surrounding infant feeding. Topics included breastfeeding challenges, perceptions of formula, and the extent and content of guidance surrounding infant feeding offered by health providers, family members, and social networks. Questions extended to participants’ general impressions of the care provided at local health facilities to understand factors likely to constrain or encourage EBF.

Questions also evaluated mothers’ perceptions of different information sources, drawing on elements of source credibility theory. In addition to open-ended questions surrounding mothers’ attitudes towards various information sources on infant feeding, a locally adapted version of a validated source credibility scale was administered during the IDIs (McCroskey & Teven, 1999). Mothers were asked to specify up to five individuals that had provided information or advice on breastfeeding and/or formula use, and to provide their level of agreement with six statements capturing trustworthiness, expertise, and caring on a 10-point Likert scale for each one.

IDIs with health providers were used to explore their perspectives on the factors contributing to infant feeding trends among study communities, the relevant messages and materials that they provide to patients, and their opinions of the challenges facing low-income mothers. Providers were also asked about the obstacles they encounter to providing optimal care and counseling, and how such issues might be addressed.

All interviews were conducted in Spanish by the first author, a trained and experienced qualitative researcher, in women’s homes or in a private room at the health facility. The interviewer was often accompanied by a field worker who helped to clarify questions as needed and recorded field notes. The interviewer used guides to loosely steer the interviews, and follow-up probes encouraged explanations and storytelling. Interviews lasted between 18 and 62 minutes and were digitally recorded with participants’ consent; otherwise, detailed notes were taken.

2.4. Data Management and Analysis

Statistical analyses.

Infant feeding surveillance and questionnaire data were double-entered by trained personnel and compared for consistency. Data analyses were performed using Stata Statistical Software version 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, Texas, USA). Distributions of variables were characterized by frequency, or by mean and standard deviation. Non-normal distributions were characterized by median and IQR. An economic wealth index was constructed from household characteristics and assets data collected during cohort study enrollment; factor scores were derived from factor analysis of nine parameters.

For all quantitative analyses, our outcome of interest was whether infants received any mixed feeding during the first 60 days of life versus being exclusively breastfed. We focused our analysis on this time period based on initial examinations of surveillance data, which indicated that mixed feeding rates rose during the first 60 days of life and stabilized thereafter. The primary predictor variable of interest was whether a mother had received a recommendation for formula from any health provider following her child’s birth. We also examined receipt of a prescription for formula from a health provider as a predictor variable in univariate analyses but did not include it in multivariate analyses due to its close correlation with receiving a formula recommendation. The latter was selected for inclusion in the model as it is a more general descriptor of health providers’ interactions with mothers surrounding formula use. We selected additional predictor variables based on factors that the existing literature and our qualitative findings suggested were associated with infant feeding practices (Adugna et al., 2017; Chandhiok et al., 2015; Dearden et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2014; Matias et al., 2012; Oliveira et al., 2017; Tampah-Naah & Kumi-Kyereme, 2013; Yeneabat et al., 2014). These included maternal age, education, marital status, parity, and employment, as well as infant birthweight, mode and site of delivery, household wealth, and whether a mother had been recommended formula use by a member of one’s social network.

After calculating descriptive statistics, we conducted regression analyses to assess whether a formula recommendation from a health provider was associated with mixed feeding and conducted survival analyses to characterize time of ceasing EBF and assess its relationship with such formula recommendations. We calculated the unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios of mixed feeding through univariate and multivariate logistic regression models using the variables described above. In addition, given that other studies have posited that formula use is driven by women’s employment, we conducted a sub-analysis stratified by working and non-working women (Ogunlesi, 2010; Olayemi et al., 2007; Safari et al., 2013; Seid et al., 2013; Setegn et al., 2012; Yeneabat et al., 2014). We also examined these relationships with the frequency of formula use (total number of days with mixed feeding and days with formula consumption only) during the first 60 days of life by fitting log-linear regression models using a robust estimator of variance (Huber, 1967; White, 1980).

Survival analyses consisted of plotting Kaplan-Meier curves and fitting adjusted and unadjusted Cox proportional hazards models. Given the left censoring of the data resulting from variation of age at cohort study enrollment, number of days of surveillance for each child was used as the unit of exposure. Age in days was the unit of analysis, and mixed feeding was treated as a one-time failure event; therefore, children did not contribute to the risk set following their first departure from EBF.

Qualitative data analysis.

Native Spanish speakers transcribed the qualitative interview recordings verbatim, and the first author coded the transcripts directly from Spanish using ATLAS.ti version 7.0 (2012) qualitative data management software (Scientific Software Development, Berlin, Germany). The codebook consisted of both a priori codes, which drew from the PEH and Source Credibility Theory, as well as emergent codes for themes and relationships drawn from the text. The initial coding scheme was reviewed and refined by two members of the research team experienced in qualitative methods (ETB and PJW), and final codes were applied to all transcripts by the first author. Following the approach to content analysis described by Graneheim and Lundman (2004), the three researchers organized codes into categories and then into broader themes, which were eventually used to develop a conceptual model (Graneheim & Lundman, 2004). Later-stage interviews were used as respondent validation, or “member-checking,” in which preliminary analyses were presented to participants to increase the credibility of the findings (Schwandt, 2001).

2.5. Ethical Considerations and Approval

The research protocol was approved by the institutional review board at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health (Baltimore, MD) and the ethics committee at Asociación Benéfica PRISMA (Lima, Peru), the local collaborating institution. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, or from the infant’s grandmother if the mother was less than 18 years old (N=4); oral assent was obtained concurrently from these participants. Separate consent was sought for the audio-recording of interviews. We identified participants by codes in the analysis, and researchers made a commitment to protect the confidentiality and anonymity of all responses.

3. Results

We compared relevant qualitative and quantitative findings to understand the relationships among health sector factors and infant feeding practices. Below, we begin with an overview of participant characteristics and infant feeding practices during the first 60 days of life. Next, we present the results of our quantitative analyses examining factors associated with mixed feeding practices. Finally, we discuss our qualitative findings related to experiences and interactions in the health services setting, drawing on exemplary quotations when appropriate. Descriptive statistics are integrated throughout to elucidate the frequency of certain experiences.

3.1. Participant Characteristics

A total of 214 mothers participated in questionnaires and provided surveillance data, with a recruitment rate of 100%. The majority had completed secondary schooling, were multiparous, and had a stable partner (Table 2). Most participants were between 20 and 30 years of age, with an average age of 27.9-years old (SD = 6.4; range, 13 to 44 years). Twenty-seven percent of women worked outside of the home, typically in the informal sector, before their infant reached six months of age. The majority of all households possessed a land title, indicating that the state officially recognized their property and was therefore more likely to invest in water and sanitation infrastructure; 173 (80.8%) of homes had an in-home piped water connection. Half of all households were moderately or severely food insecure.

Table 2.

Characteristics of participating mother-infant dyads (N=214).1

| Characteristic | N (%) or Mean (SD) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Maternal characteristics | |

| Maternal age (years) | |

| <20 | 18 (8.4) |

| 20–30 | 121 (56.5) |

| 31–40 | 68 (31.8) |

| >40 | 7 (3.3) |

| Maternal educational attainment | |

| Incomplete primary school (<6 years) | 18 (8.4) |

| Incomplete secondary school (6–11 years) | 62 (29.0) |

| Complete secondary school (12 years) | 134 (62.6) |

| Civil status | |

| Has stable partner | 182 (85.1) |

| Single mother | 32 (15.0) |

| Maternal employment outside of home when infant < 6 months of age | |

| No | 156 (72.9) |

| Yes | 58 (27.1) |

| Parity | |

| Multiparous | 156 (72.9) |

| Primiparous | 58 (27.1) |

| Infant characteristics | |

| Infant sex | |

| Male | 111 (51.9) |

| Female | 103 (48.1) |

| Infant birthweight in grams | 3434 (548) |

| Age at enrollment in days (median, interquartile range) | 12 (7, 21) |

| Birth and health facility utilization | |

| Mode of delivery | |

| Vaginal | 152 (71.0) |

| Cesarean | 62 (29.0) |

| Site of birth | |

| Public hospital | 100 (46.7) |

| Public health center | 62 (29.0) |

| EsSalud hospital | 41 (19.2) |

| Private clinic | 11 (5.1) |

| Site of well-baby care | |

| Community health post | 135 (63.1) |

| Public health center | 37 (17.3) |

| EsSalud hospital | 24 (11.2) |

| Private clinic | 11 (5.1) |

| Public hospital | 4 (1.9) |

| Did not seek services | 3 (1.4) |

| Household characteristics | |

| Property ownership | |

| With land title | 153 (71.5) |

| Without land title | 61 (28.5) |

| Food insecurity access | |

| Food secure | 68 (31.8) |

| Mildly food insecure | 39 (18.2) |

| Moderately food insecure | 53 (24.8) |

| Severely food insecure | 54 (25.2) |

| Source of drinking water2 | |

| In-home connection to piped water | 173 (80.8) |

| No in-home connection to piped water | 41 (19.2) |

Column percentages.

Source of drinking water is one of the nine parameters that contributed to the construction of the economic wealth index used in the regression analyses.

Approximately three-quarters (75.7%) of women gave birth in a public hospital or public health center, with most of the remaining deliveries taking place at an EsSalud hospital, and 62 (29.0%) had a cesarean delivery. Infants weighed an average of 3434 g (SD = 548 g) at birth, with 4.2% classified as low birth weight (LBW; < 2500 g), and 51.9% of infants were male. Community health posts were the most common site for postnatal care (63.1%). At enrollment into the cohort study, the median infant age was 12 days (SD = 8.6); and 75.0% of all infants were enrolled prior to reaching 21 days of age.

Seventy-three mothers (34.1%) received verbal recommendations for formula use from a health provider. Of these 73 mothers, 51 (69.9%) also received a written prescription for a formula brand. Thus, formula prescriptions were given to 23.8% of the study population. Questionnaire data revealed that recommendations and prescriptions for formula were provided at both public and private health facilities. More than half of all recommendations (58.9%) and prescriptions (56.9%) came from a public facility (hospital, health center, or health post). Doctors provided the majority (90.4% and 98.0%, respectively) (Table 3). Twenty prescriptions (39.2%) were provided directly after delivery before the mother-infant dyad had been discharged from the hospital, and another 10 (19.6%) were provided during the first week of the infant’s life (Table 3).

Table 3.

Sources and timing of recommendations and prescriptions for formula use.1

| Variable | Verbal recommendation (N=73) N (%) | Written prescription (N=51) N (%) |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Health facility | ||

| Public hospital | 23 (31.5) | 22(43.1) |

| Public health center | 14 (19.2) | 5 (9.8) |

| Community health post | 6 (8.2) | 2 (3.9) |

| Private clinic | 20 (27.4) | 9 (17.6) |

| EsSalud hospital | 10 (13.7) | 9 (17.6) |

| Missing | 0 | 4 (7.8) |

| Type of provider | ||

| Doctor/pediatrician | 66 (90.4) | 50 (98.0) |

| Nurse | 4 (5.5) | - |

| Obstetrician | 2 (2.7) | 1 (2.0) |

| Nutritionist | 1 (1.4) | - |

| Age of infant2 | ||

| Newborn (before hospital discharge) | 20 (39.2) | |

| After discharge through 1 week of age | 10 (19.6) | |

| > 1 week through 1 month of age | 7 (13.7) | |

| > 1 month through 2 months of age | 6 (11.8) | |

| > 2 months of age | 7 (13.7) | |

| Missing | 1 (2.0) | |

Column percentages

These data were not collected for formula recommendations.

Mothers participating in the IDIs were distributed evenly across the wealth quartiles observed in the larger study population, with the exception that a smaller percentage of IDI participants (5 out of 29, or 17.2%) were found in the lowest quartile, and the majority had official property rights. Only one of the purposively selected mothers refused to take part in the interview due to scheduling concerns, for a recruitment rate of 96.7%.

Of the seven health providers that participated in IDIs, four worked at community health posts and three worked at the larger public health centers. Four of the seven providers were nurses and three were doctors; six providers were female. The recruitment rate for health providers was 77.8%, as one nurse and one doctor declined study participation upon being approached by the study team.

3.2. Infant Feeding Practices

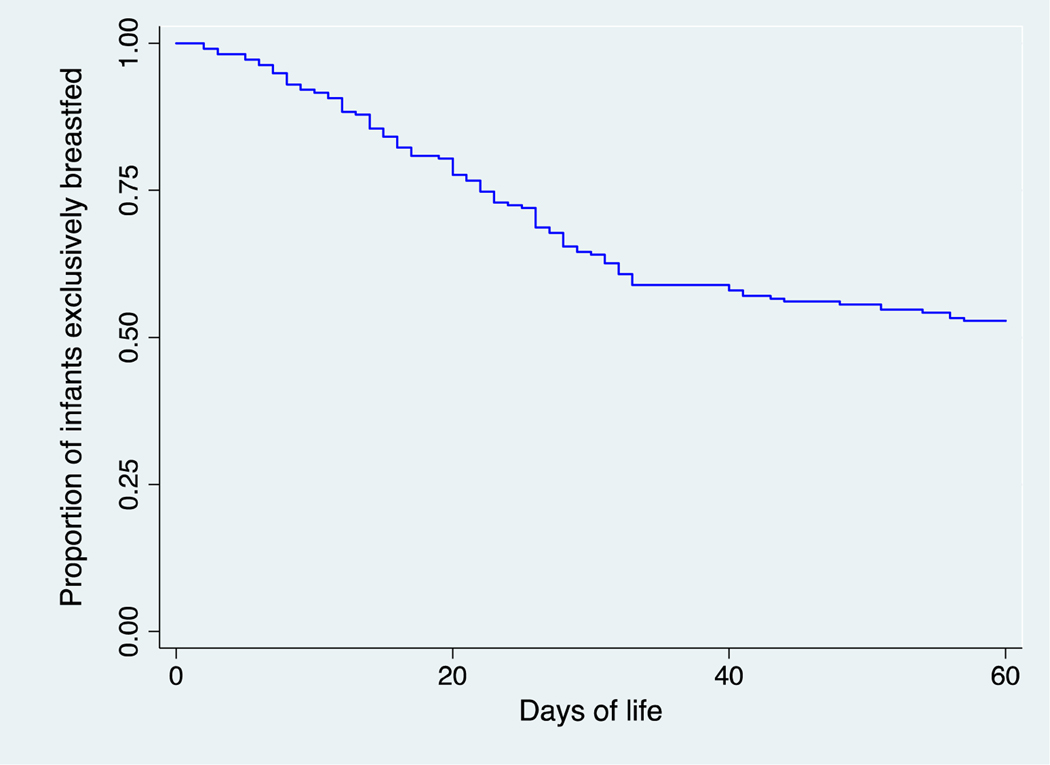

By 60 days of age, 101 (47.2%) infants had any mixed feeding (Figure 2a). Among those 101 infants, the median age upon first exposure to formula was 22 days. Once initiated, mixed feeding was adopted in most cases: the median percentage of days consuming formula was 59.2%, with half of those 101 infants consuming formula on 19.0% to 93.1% of days during the first 60 days of life. Formula use was an isolated event for only five infants (2.3% of the study population). Feeding with only formula as opposed to mixed feeding was rare: only four infants displayed this practice during the first 60 days of life. In these four cases, the infant initially received mixed feeding or EBF (for a minimum of 21 days and a maximum of 54 days) before the mother switched to formula only. Of the nine LBW infants in our study population, five practiced mixed feeding during the first 60 days of life; these infants consumed formula on an average of 58.5% of days.

Fig. 2a.

Overall Kaplan-Meier survival curve for time until first occurrence of mixed feeding.

3.3. Factors Associated with Mixed Feeding

Table 4 presents the associations of predictor variables with any mixed feeding during the first 60 days of life. The first column documents the independent relationship of each variable with the likelihood of any mixed feeding rather than EBF during the first 60 days of an infant’s life. This outcome was significantly associated (p<0.05) with a health provider having recommended use, a health provider having prescribed use, single motherhood, and maternal employment in the unadjusted analysis (Table 4). The magnitude of association was greatest for a health provider’s formula recommendation (OR = 8.8; 95% CI = 4.5 to 17.2). The association was similar among mothers who received a written prescription accompanying the verbal recommendation, and those who received only the verbal recommendation (OR = 7.3; CI = 3.4 to 15.7; and OR = 7.9; CI = 2.7 to 22.9, respectively; not shown in Table 4). No association was found for other socio-demographic characteristics such as maternal age, education, parity, wealth, infant birthweight, delivery mode, or site of birth, aside from a reduced likelihood of mixed feeding among infants born at a public health center as compared to the reference group of a public hospital. Receiving a recommendation for formula use from a member of one’s social network was also not significantly associated with likelihood of mixed feeding.

Table 4.

Associations between variables of interest and any mixed feeding from birth to 60 days of age, unadjusted and adjusted odds ratios.

| Characteristic | Unadjusted odds ratios | Adjusted odds ratios | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| OR (95% CI) | p | OR (95% CI) | p | |

|

| ||||

| Maternal age (5-year change) | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3) | 0.420 | 1.4 (1.0 to 1.9) | 0.029 |

| Maternal educational attainment | ||||

| Incomplete primary school (<6 years) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Incomplete secondary school (6-11 years) | 0.6 (0.2 to 1.7) | 0.309 | 0.2 (0.1 to 0.9) | 0.034 |

| Complete secondary school (12 years) | 0.8 (0.3 to 2.0) | 0.575 | 0.4 (0.1 to 1.3) | 0.132 |

| Civil status | ||||

| Stable partner | Ref | Ref | ||

| Single mother | 2.9 (1.3 to 6.4) | 0.010 | 1.5 (0.6 to 4.1) | 0.389 |

| Parity | ||||

| Multiparous | Ref | Ref | ||

| Primiparous | 1.4 (0.8 to 2.6) | 0.275 | 2.2 (0.9 to 5.4) | 0.070 |

| Maternal employment outside of home when infant < 6 months of age | ||||

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 3.9 (2.0 to 7.4) | <0.001 | 3.2 (1.5 to 6.8) | 0.002 |

| Infant birthweight in grams | 0.98 (0.6 to 1.6) | 0.932 | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.5) | 0.438 |

| Household wealth | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.3) | 0.938 | 0.8 (0.6 to 1.2) | 0.278 |

| Mode of delivery | ||||

| Vaginal | Ref | Ref | ||

| Cesarean | 1.7 (0.9 to 3.1) | 0.085 | 1.5 (0.7 to 3.1) | 0.274 |

| Site of birth | ||||

| Public hospital | Ref | |||

| Public health center | 0.5 (0.2 to 0.9) | 0.023 | ||

| EsSalud hospital | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.5) | 0.409 | ||

| Private clinic | 1.0 (0.3 to 3.7) | 0.973 | ||

| Health provider recommended formula | ||||

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 8.8 (4.5 to 17.2) | <0.001 | 10.2 (4.8 to 21.6) | <0.001 |

| Health provider prescribed formulaa | ||||

| No | Ref | |||

| Yes | 7.3 (3.4 to 15.7) | <0.001 | ||

| Member of social network recommended formula | ||||

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 1.4 (0.8 to 2.4) | 0.252 | 1.5 (0.8 to 3.0) | 0.235 |

This variable was not included in the multivariable analysis due to its close correlation with formula being recommended by a health provider.

The second column of Table 4 displays the predictor variables that remained in our multivariate model. The association between mixed feeding and a health provider’s formula recommendation remained significant and increased in magnitude in the multivariate model. Regression results (Table 4) indicated that mothers who received a recommendation for formula from a health provider were 10 times more likely to practice mixed feeding, even after adjusting for other potential influences (OR = 10.2; CI = 4.8 to 21.6). Sub-analyses revealed that the increase in this association in the multivariate model was the result of negative confounding by parity and the mother having received a formula recommendation from a member of her social network.

The association between mixed feeding and mothers’ employment outside of the home also remained significant but decreased slightly in magnitude in the adjusted model (OR = 3.2; CI = 1.5 to 6.8); the association with civil status was no longer significant. The association of mixed feeding with maternal educational attainment of six to 11 schoolyears became significant in the adjusted model, indicating that the least educated group of mothers was approximately five times more likely to practice mixed feeding as compared to those who completed primary school; yet no significant difference in likelihood of mixed feeding was seen between the lowest and highest education strata. Similar inferences were drawn from the log-linear regression models in which frequency of formula during the first 60 days was most significantly associated with a health provider’s formula recommendation.

Examining the association between predictor variables and time to ceasing EBF (first occurrence of mixed feeding) yielded similar findings. Kaplan-Meier plots (Figures 2a and 2b) show the estimated proportion of infants of a given age who are exclusively breastfed, both overall and disaggregated by whether or not their mother received a recommendation for formula from a health provider. As these plots demonstrate, EBF rates decline substantially faster over time among infants whose mothers were recommended formula. Table 5 presents the Cox proportional hazard model estimates, with the univariate analyses in the first column and the multivariate analyses in the second column. The estimates indicate that the relationship between a mother receiving a formula recommendation and the hazard of ceasing EBF persists even after adjusting for other variables that demonstrated a significant association in the unadjusted analyses (Table 5). Receiving a formula recommendation from a health provider was associated with a 360% greater hazard of ceasing EBF in the univariate model, and a 420% greater hazard of ceasing EBF in the multivariate model (Hazard Ratio (HR) = 3.6, CI = 2.6 to 5.2, and HR = 4.2, CI = 2.7 to 6.5, respectively).

Fig. 2b.

Kaplan-Meier survival curve stratified by mother’s receipt of a recommendation for formula from a health provider.

Table 5.

Associations between variables of interest and hazard of ending exclusive breastfeeding from birth to 60 days of age, unadjusted and adjusted hazard ratios

| Characteristic | Unadjusted hazard ratios | Adjusted hazard ratios | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| HR (95% CI) | p | HR (95% CI) | p | |

|

| ||||

| Maternal age (5-year change) | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.2) | 0.693 | 1.3 (1.1 to 1.6) | 0.005 |

| Maternal educational attainment | ||||

| Incomplete primary school (<6 years) | Ref | Ref | ||

| Incomplete secondary school (6-11 years) | 0.6 (0.3 to 1.4) | 0.280 | 0.3 (0.1 to 0.6) | 0.001 |

| Complete secondary school (12 years) | 1.0 (0.5 to 1.8) | 0.890 | 0.4 (0.2 to 0.9) | 0.029 |

| Civil status | ||||

| Stable partner | Ref | Ref | ||

| Single mother | 2.0 (1.3 to 3.1) | 0.002 | 1.4 (0.9 to 2.4) | 0.149 |

| Parity | ||||

| Multiparous | Ref | Ref | ||

| Primiparous | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.9) | 0.140 | 1.8 (1.1 to 2.9) | 0.023 |

| Maternal employment outside of home when infant < 6 months of age | ||||

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 2.4 (1.7 to 3.5) | <0.001 | 1.8 (1.2 to 2.8) | 0.007 |

| Infant birthweight in grams | 1.0 (0.7 to 1.4) | 0.977 | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.7) | 0.405 |

| Household wealth | 1.1 (0.9 to 1.3) | 0.340 | 0.9 (0.7 to 1.1) | 0.155 |

| Mode of delivery | ||||

| Vaginal | Ref | Ref | ||

| Cesarean | 1.4 (0.9 to 2.0) | 0.095 | 1.3 (0.8 to 2.0) | 0.298 |

| Site of birth | ||||

| Public hospital | Ref | |||

| Public health center | 0.6 (0.4 to 1.0) | 0.033 | ||

| EsSalud hospital | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.3) | 0.382 | ||

| Private clinic | 0.9 (0.4 to 2.0) | 0.863 | ||

| Health provider recommended formula | ||||

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 3.6 (2.6 to 5.2) | <0.001 | 4.2 (2.7 to 6.5) | <0.001 |

| Health provider prescribed formulaa | ||||

| No | Ref | |||

| Yes | 3.0 (2.1 to 4.3) | <0.001 | ||

| Member of social network recommended formula | ||||

| No | Ref | Ref | ||

| Yes | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | 0.510 | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.3) | 0.075 |

This variable was not included in the multivariable analysis due to its close correlation with formula being recommended by a health provider.

The sub-analysis stratifying on maternal employment indicated that a health provider’s recommendation for formula strongly predicted mixed feeding among both working and non-working women, even after controlling for civil status and maternal age (Supplementary Table 1). The magnitude of the association was greater among nonworking women as compared to working women (OR = 10.5; CI = 4.6 to 23.8; and OR = 4.0; CI = 1.1 to 15.1, respectively), yet this difference was not statistically significant.

3.4. Impact of Health Providers’ Recommendations and Prescriptions on Maternal Attitudes

Our qualitative interviews revealed that knowledge of the indispensable benefits of breastmilk for child development and disease resistance was widespread among mothers. As one mother explained, “Breastmilk is the best to prevent them from suffering from infections, from diarrhea, from any sickness—it protects them.” Nevertheless, formula was often viewed as a helpful addition. The majority of the 29 interviewed mothers used the reflexive verb “to help me” (ayudarme) when describing advice that they had received from health providers, or spoke of formula as a necessary “complement” (complemento) or “reinforcement” (resfuerzo) to breastmilk.

Participants recalled having received recommendations or prescriptions for a specific formula brand without prompting during their clinical encounters. In six cases, formula was presented as an option for a new mother directly following delivery if challenges with breastfeeding were to emerge or if her breastmilk did not “fill up” the infant. One mother recalled that, after giving birth in a public hospital, “[The doctor] gave me the prescription in case the baby didn’t want anything with my breast…he said, ‘In case you don’t have milk, you’re going to have to give this to him, because he’ll cry from hunger.’”

In the household setting, infants’ behaviors reinforced messages that mothers received in health facilities. An infant’s unsettled temperament was commonly perceived as hunger, which in turn was ascribed to a poor breastmilk supply and interpreted as the need for formula.

After five days, I began to give her NAN milk, because she was crying too much. I thought, “Why is she crying?” Could it be because she was not accustomed, or could it be because she was scared—no. If she was crying, it was because she was hungry. She didn’t fill up with my breast. (33-year-old mother, incomplete secondary school education)

Two nurses commented on the consequences of doctors recommending formula to mothers directly after delivery. One health post nurse emphasized that the most important moment for conveying the value of EBF was at birth; therefore, “if the mamá does not have that idea when she is discharged from the hospital, she’s going to end up giving some kind of formula.” She explained that receiving a formula prescription from a doctor at this critical point made it appealing since “the doctor—by hierarchy—is at the top and is the one authorized to explain everything.”

Doctors would also present formula as a necessary measure for growth amidst concerns about an infant’s weight. Formula was prescribed to five of the nine mothers of LBW babies before hospital discharge. At other times, doctors recommended formula after a child lost weight. For example, after her two-week-old daughter lost weight when she became sick with a cough and vomiting, one 20-year-old mother explained that she saw a pediatrician at a private clinic: “She had already lost 200 grams. I wanted her to gain weight and they recommended a formula…[the doctor] told me that I should give it to her so that it could help her gain weight. That they were vitamins.”

Following the introduction of formula, three mothers recalled a sense of relief when a health provider reported that their infant had gained weight.

She began to gain weight quickly, and I was feeding her with the bottle and my breast, mixed. And when she went to be weighed, they told me, “Her weight is good, her height is good.” So, I said to myself, “Ok, I’ll have to keep giving her formula…that’s how it happened and from there, it was alright—she began to get fatter and fatter, and now she’s huge. Look! (21-year-old mother, incomplete secondary school education)

Observable changes like this one served to validate health providers’ depiction of formula as a “help,” reinforcing the perceived need for it. In contrast, risks associated with formula were seldom conveyed during clinical encounters. Participants rarely mentioned the downsides of formula use, aside from one participant citing a fear that it could cause allergies. Five mothers reported the practice of starting a feeding episode with formula and then subsequently breastfeeding.

3.5. Formula Industry Representatives’ Engagement with Health Providers

Our interviews with doctors and nurses revealed that industry representatives regularly visit hospitals and public health centers, despite nationwide legislation prohibiting such activities. Table 6 presents quotations from study participants depicting representatives’ activities and their effects on health providers. Five of the seven interviewed health providers described how the representatives would discuss their products and provide them with formula samples and promotional items like calendars. According to both doctors and nurses, the representatives would frequently offer incentivizing gifts such as free or subsidized courses, conferences, and trips. Health providers would often distribute gifted samples of powdered formula to patients. Four mothers recalled receiving free formula or vouchers from doctors, and another two mothers recalled that a doctor had sold them the formula samples at a discounted price during their health visits. However, some health providers reported discarding the brochures and gifted formula. Two others reported distributing it exclusively to mothers with infants above one year of age or those whom they perceived as truly needing it, such as HIV-positive mothers or those on psychiatric medications. In two cases, nurses acknowledged the discordance between governmental policies and industry contacts with health providers. One health center nurse recounted how the health center where she worked failed to be certified as baby-friendly during the most recent evaluation because formula advertising materials were observed in the facility. Another nurse from a health post placed the blame for formula companies’ activities on higher-level authorities who should be enforcing the policies.

Table 6.

Qualitative themes and illustrative quotations regarding formula industry representatives’ engagement with health providers.

| Themes | Illustrative quotations | Frequency of reporting |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Industry representatives leave formula samples and promotional items at health facilities | “They enter the offices, they walk around and come in when there’s an opportunity and leave their brochures.” (Health center nurse) | 5 health providers |

| “The medical visitors, just like they do with samples of medications, they also leave formula—different formulas for newborns, for six months to one year, and for preschoolers. They leave them for us to distribute. They come here [to the health center] but they aren’t too many. In [the major hospital] there is a ton.” (Health center doctor) | ||

| Industry representatives offer incentivizing gifts to health providers | I know that they give them [the doctors] a bonus for every sale. Not necessarily in cash, but they give them courses, scientific trips. Enfamil comes here, NAN comes…they orient us and talk to us and all that. (Health center nurse) | 3 health providers |

| Health providers offer free formula samples, vouchers, or sell formula to mothers at a discounted price |

“‘It’s something like 60 soles,’ [the doctor] told me. I said, ‘alright, we’ll save up.’ We were leaving and then the doctor said, ‘Come darling, don’t go. Here I have a little container.’ So, I left there happy, with my milk and everything and I told her, ‘thank you, thank you so much!’ I left there happy.”

(38-year-old mother, complete secondary school education) |

6 mothers |

|

“He recommended formula, and said that if my daughter was drinking Enfamil, that he would sell it to me at half the price—at 30 soles. From what would cost me 61, he was going to give it to me for 30.”

(31-year old mother, compete secondary school education) | ||

| Nurses aware of discordance of industry presence and regulatory policies | “Sometimes I say, ‘What a pity,’ because if we are the ones promoting breastfeeding, how can it be that I receive a course, receive a gift, receive a suitcase, some pens, just for simply promoting their milk? We have 10 important steps to promote breastfeeding and among them is saying ‘no’ to the formulas.” (Health center nurse) | 2 health providers |

| “I think the Ministry of Health or the directorate, the leadership, they aren’t prohibiting that they [formula company representatives] enter. Because if the guard at the door said, ‘don’t enter,’ they would not enter.” (Health post nurse) | ||

3.6. Insufficient Counseling Weakens Nurses’ Promotion of Breastfeeding

Nearly all interviewed mothers recalled that the nurses attending to them after childbirth and during well-baby visits strongly promoted EBF and discouraged formula use. However, mothers were critical of the lack of interpersonal counseling on how to breastfeed; more than half recounted that nurses would say “breast, breast, breast” or otherwise command EBF without providing further instructions or explanations.

These interactions bred frustration and a sense of helplessness following delivery, especially among first-time mothers. As one teenage mother recalled her experience in the hospital, “The nurses weren’t helping me…no, they didn’t say anything. ‘You have to breastfeed’ and that’s it. They told me, ‘You’re young, you have to do it.’” Experiences like this one motivated one mother of twins to suggest,

They [the nurses] should incentivize breastfeeding more, as it’s said, with practice, not just talking and telling us things, but rather teach us how…they should teach you, “Here’s the right way to breastfeed.” If it was like that in every hospital, the formula companies would go bankrupt! (30year-old mother, complete secondary school education)

The lack of personalized guidance on breastfeeding was also noted during well-baby services, which were most commonly sought at community health posts or public health centers (Table 2). Sixteen participants commented on the long lines, waiting times, and/or limited hours of operation (9:00 am to 1:00 pm) at the health posts, and described rushed visits in which nurses prioritized vaccinations and anthropometry without leaving any time for discussion. Nurses were often perceived as impatient and disrespectful during these clinical encounters, as mothers complained that some attend their patients “grudgingly” (de malas ganas) and “treat you like nothing” (te tratan como cualquier cosa).

Interviewed nurses, for their part, expressed awareness of flaws in the well-baby care provided, and attributed these issues to inefficiencies and shortages within the health system. The government-sponsored insurance program requires nurses to fill out individual paper forms for each service provided during the visit, which demands a significant amount of time during each work day. As one health center nurse explained, “It’s because of the bureaucracy here of all the papers…we would be able to give better care if we didn’t have to fill out so much for SIS [the government-subsidized insurance program].” Another nurse pointed out that she could not provide adequate demonstrations of breastfeeding techniques at her health post due to limited personnel and the lack of enabling resources like mannequins, which are present at hospitals.

In the context of perceived inattention and disrespect from nurses, mothers consistently expressed lower levels of trust in nurses as compared to doctors. Based on responses to the adapted source credibility scale exercise (N=29), doctors received an average score of 54.2 out of a possible 60, whereas nurses received an average score of 41.7. Doctors received higher average scores for each of the six attributes captured, with their highest average scores corresponding to the attributes of “intelligence” and “sincerity.” Given their high levels of trust in doctors’ authority, many mothers were disposed to adhere to their advice regarding a child’s health:

As it is said, to be healthy, we have to do what the doctor teaches us, because if I don’t, how does that serve me? He teaches me something and I do it for my children, so that they are healthy, so that they don’t become ill. (41-year-old mother, incomplete secondary school education)

4. Discussion

This study employed mixed methods to provide a comprehensive picture of the relationships between health sector factors and mothers’ infant feeding decisions. The integration of quantitative and qualitative methods allowed for an understanding of population-level trends as well as intimate individual experiences. Ultimately, this study design provides more complete and valid results than reliance on individual methods alone (Creswell et al., 2011).

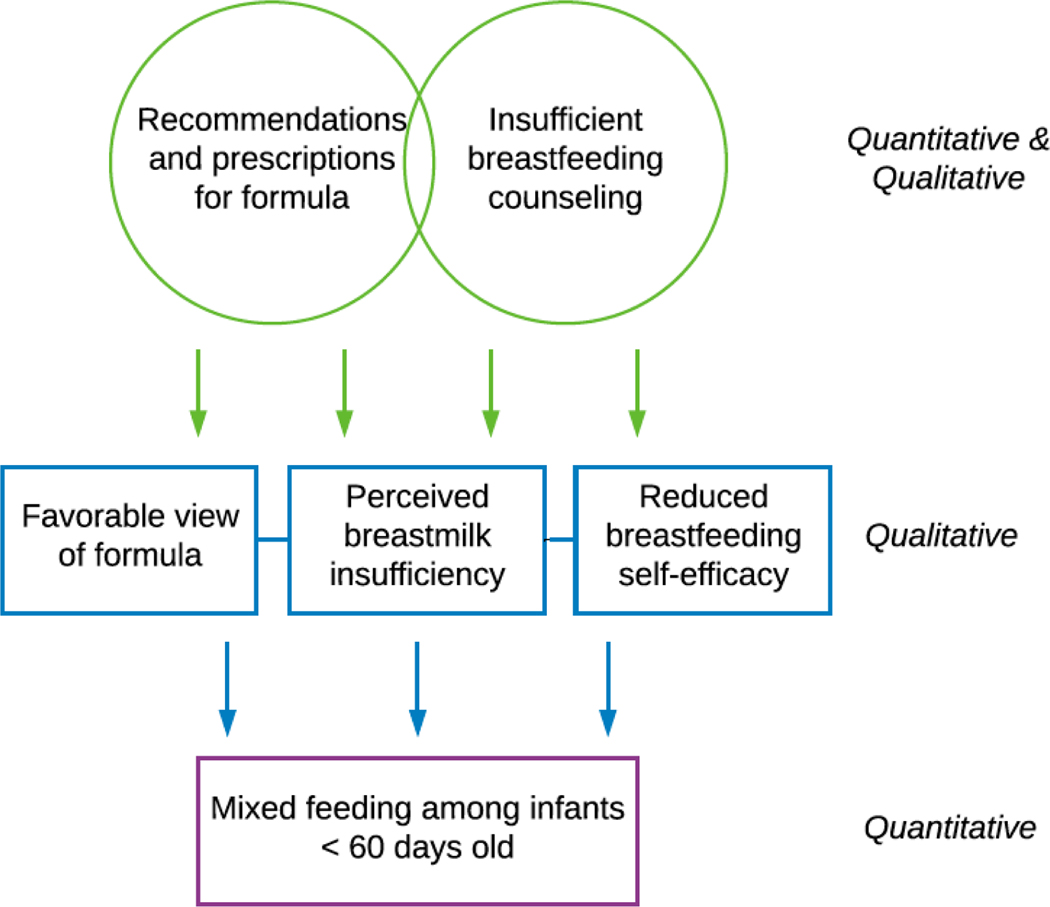

A conceptual model (Figure 3) was developed to summarize our findings, with the source of data identified for each component of the model. This model displays how two key factors—(1) health providers’ recommendations and prescriptions for formula use, ostensibly as a result of industry interference, and (2) weaknesses within breastfeeding promotion efforts—shape maternal attitudes surrounding breastfeeding and formula use. Specifically, health providers’ framing of formula as a “help” or “supplement” gives rise to a favorable view of it among mothers, while preemptive suggestions that a specific formula brand might be necessary if a breastfed infant does not “fill up” often translate to mothers’ perceived breastmilk insufficiency. At the same time, facility-based breastfeeding promotion is limited by the lack of personalized guidance coupled with unpleasant interactions with nurses. These experiences undermine mothers’ self-efficacy in their ability to exclusively breastfeed, while also exacerbating their perceptions of insufficient breastmilk. Together, these attitudes lead to decisions to begin mixed feeding and unnecessary formula use.

Figure 3.

Conceptual model of health sector influences on mixed feeding in Villa El Salvador, Peru.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to draw on daily surveillance data of infant feeding practices to demonstrate the consequences of providers’ formula recommendations. While most epidemiologic studies of barriers to breastfeeding employ cross-sectional questionnaires that rely on recall periods of several months, the richness of our longitudinal data allowed us to create a detailed profile of infant feeding practices during the first 60 days of life. Our data indicate that the first exposure to formula occurs at an early age and sets off a longer trend of mixed feeding in early life. Given the importance of initial formula use for subsequent feeding practices, we employed survival analysis to examine the predictor on age upon formula initiation (see Figures 2a and 2b). Our longitudinal data allowed us to assess this outcome variable along with several others, including a dichotomous indicator of any mixed feeding and a quantitative measure of frequency of formula use. All of these analyses add further validity to our conclusions.

Study findings suggest that the health facilities in our study zone tend not to be enabling environments for exclusive breastfeeding. A health provider’s recommendation for formula remained the strongest predictor of any mixed feeding—and even increased slightly in magnitude—after controlling for other variables that have been shown to influence infant feeding practices, attesting to the strong influence of health providers in this setting (see Table 4). Furthermore, our sub-analysis indicated that this association was significant among both working and non-working women (see Supplementary Table 1). These findings suggest that the widespread assumption that the rise in maternal employment is the key determinant of rising rates of formula use must be reconsidered. Further, the recommendations and prescriptions for formula that we observed cannot be attributed to high-risk infants, given that the cohort study excluded such participants. Nor can they be attributed to a mother’s physiologic inability to breastfeed, as none of our study participants practiced formula use only without mixed feeding preceding it. Globally, it is estimated that less than 5% of women are unable to produce adequate breastmilk to satisfy an infant’s needs, known as primary lactation insufficiency (Neifert, 2001).

Our findings align with those of several other studies that have shed light on the commercial promotion of formula within the health sector. Monitoring activities carried out by the Pan-American Health Organization (2011) found that 17 out of 29 health facilities surveyed in Lima received donations from formula companies, and that this practice was common in several other administrative regions of Peru (UNICEF/PAHO, 2011). There is also evidence of formula industry representatives providing gifts and products to health providers in Ecuador, Laos, Thailand, Bangladesh, South Africa, and China (Save the Children, 2013b; Ministerio de Salud Pública, 2012; Taylor, 1998). The practice of providers recommending formula to vulnerable mothers has been documented in Cambodia, Nepal, Pakistan, and the Philippines (Save the Children, 2013a; A. Pries, Huffman, S., Champeny, M.2014; A. M. Pries et al., 2016; Sobel et al., 2011). In disadvantaged urban and rural communities in the Philippines, Sobel and colleagues (2011) found that about 1/6 of their participants had received a recommendation for formula from their doctor, which had a 3.7-fold increase on the odds of formula use. Clearly, violations of the Code and their consequences for breastfeeding rates are a global concern.

Formula companies’ marketing activities and their interactions with health providers are key macro-level factors that constrain women’s decision-making agency and, ultimately, structure the proximate risks to child health. It has been argued that the availability of formula in health facilities, including formula giveaways upon hospital discharge or during well-baby care, supports women’s agency by increasing access to all feeding options and allowing them to choose one based on their own needs and preferences (Morain & Barnhill, 2018). However, a health provider’s gifting, recommendation, or prescription of a specific formula brand is not a neutral act; rather, it is perceived as an endorsement of that product (Walker, 2015). This point is evidenced by numerous studies demonstrating the associations of lower EBF rates with formula giveaways at hospitals (Frank et al., 1987; Rosenberg et al., 2008; Sadacharan et al., 2014; Snell et al., 1992). A doctor’s positive stance towards formula often proves particularly compelling due to the credibility and authority attributed to them, as illustrated by our qualitative findings.

These activities also have economic consequences for new mothers and their families. While health providers and mothers alike may perceive that a formula sample or voucher provides economic relief, mixed feeding may be more likely to exacerbate household socioeconomic vulnerabilities over the long term. The small formula samples are often the more expensive brands on the market. In the context of perceived endorsement from a doctor, households face the burden of purchasing this same expensive brand when the initial sample runs out. Given that 25.2% of our study participants are severely food insecure (see Table 2), these purchases may be a significant sacrifice for the household budget. As these are powders, they must also be mixed with water, and unsafe water and incomplete bottle disinfection increase the likelihood of pathogen transmission (Rothstein et al., 2019).

Furthermore, our study participants’ narratives revealed how several features of their clinical experiences weakened nurses’ capacity to encourage optimal breastfeeding. Nurses rarely offered technical or trouble-shooting advice for breastfeeding, and their perceived disrespectful and impatient attitudes eroded mothers’ trust in them. Similar behaviors among nursing staff have been observed in Niger and with Bangladeshi immigrants in the United Kingdom (Moussa Abba et al., 2010; Rayment et al., 2016). These types of interactions likely had motivational as well as practical consequences for new mothers, given that most mothers need practical support to learn how to breastfeed and overcome emerging challenges (McFadden et al., 2017; WHO/UNICEF, 2018). As highlighted in the Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative’s “ten steps to successful breastfeeding”, which have been demonstrated to improve breastfeeding outcomes, the WHO recommends nursing or technical staff employ direct observations to teach good positioning and attachment, and to counsel mothers on issues such as preventing nipple soreness and cracking (Perez-Escamilla et al., 2016; WHO/UNICEF, 2018). Our data suggest that the care provided to recently delivered mothers in peri-urban Lima is inconsistent with these guidelines. Coupled with the formula industry’s interference in the health sector, these circumstances undermine women’s access to the balanced, unbiased information necessary for making informed choices about infant feeding, which the United Nations has deemed a human right (United Nations Office of the High Comissioner for Human Rights, 2016).

The violations of the Code evidenced by our study reflect weaknesses in its implementation and enforcement. Although Peru is one of only 37 countries (out of a total of 199 countries for which data are available) that have fully enacted the Code’s recommendations, it has not passed any regulations to enforce or monitor it (WHO, 2013). The Baby-Friendly Hospital Initiative has faced similar implementation challenges: Only eight out of Peru’s 509 birthing facilities (1.6%) have been certified or re-certified as baby-friendly since 2008 (PAHO/WHO, 2016). Further research would provide data on the extent to which our findings are reflective of only the local context, or of regional or nation-wide issues related to implementation and regulation.

4.1. Limitations

This study faced several methodological limitations. Because our quantitative analysis focuses only on the first 60 days of life, we are not able to comment on the use of formula during the entire six-month period when EBF is recommended. However, several studies have indicated that feeding practices established during early infancy largely determine patterns throughout the first six months of life (Patil et al., 2015; Piwoz et al., 1994), and our own analyses indicated that mixed feeding rates stabilized at or before 60 days. In the logistic regression models, the confidence intervals associated with the primary predictor—a health provider’s recommendation for formula—are wide, indicating a lower level of certainty in the point estimates. This imprecision may have resulted in part from our relatively small sample size. The semi-structured questionnaires, including questions regarding formula recommendations and prescriptions from health providers, were administered cross-sectionally and therefore may have been subject to recall bias. Collecting these data through a more structured approach, such as leveraging the cohort study’s enrollment questionnaire for inquiring about information sources on breastfeeding and formula, may have been more effective; however, this approach was not feasible due to the timing of our nested research study. Data collected on mother’s employment status referred to the first six months of an infant’s life, rather than the first 60 days. Data on mother’s interactions with health providers were based on secondary report, and we did not observe the frequency of recommendations or prescriptions from health providers. Nevertheless, when possible, field workers confirmed the receipt of the formula prescription by asking mothers to show them the physical piece of paper during their home visits. Finally, there may have been unmeasured confounders, as many variables were not observed. Finally, the IDI sample of mothers was limited to those who were practicing mixed feeding; therefore, the qualitative data does not capture the healthcare experiences of women who continued to practice EBF.

5. Conclusions

Limitations aside, our study offers compelling evidence that more than three decades after the Code’s adoption into Peruvian law, unethical violations may be common and continue to target vulnerable populations. Our findings reinforce previous studies indicating that legislation supporting the Code is a necessary but not sufficient step for controlling industry interference in the health sector (Perez-Escamilla et al., 2012; Robinson et al., 2018). As in most Latin American countries, Peru has not passed any regulations to enforce or monitor the legislation adopted in support of the Code (Lutter, 2013). Pérez-Escamilla et al.’s “breastfeeding gear model” indicates that several elements must be working in coordination to support and scale up breastfeeding programs (Perez-Escamilla et al., 2012), including political will and a well-established, functioning monitoring system that reports inappropriate practices and can impose appropriate sanctions against companies and disciplinary actions for health providers. More robust efforts such as these at the policy and institutional levels are needed to protect mothers and infants from the unethical promotion of formula and its negative sequalae.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Data collection methods, goals, and participants.

| Data collection method | Goal of method | No. of participants |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Daily feeding surveillance | Record daily infant feeding practices | 214 caregivers |

| Semi-structured questionnaire | Evaluate factors related to information sources, health facility utilization, and maternal and infant characteristics | 214 caregivers |

| In-depth interviews | Explore mothers’ decision-making processes surrounding infant feeding and related institutional factors; Explore health providers’ perspectives on infant feeding, advice given to patients, and engagement with formula companies |

29 mothers; 7 health providers |

Research highlights:

Describes rates of unnecessary formula use during infants’ first 60 days of life.

Demonstrates how formula companies market products directly to health providers.

Reveals how providers’ formula “prescriptions” lead to higher mixed feeding rates.

Describes how poor counseling from nurses hinders mothers’ ability to breastfeed.

Shows the need to improve monitoring of legislation to control formula marketing.

Acknowledgements:

The authors gratefully acknowledge the study participants of Villa El Salvador for their engagement and sharing of experiences which made this research possible. We thank Lilia Z. Cabrera for her assistance with data collection, as well as Mónica Pajuelo, Francesca Schiaffino, and Maya P. Ochoa for their input during data analysis. The authors also wish to acknowledge members of the field team including Blanca I. Delgado, Cristel M. Lizarraga, Nelly M. Briceño, Jessica Pachas, Flor de Maria Pizarro, Mercedes Margarita Escobar, Leyda Murga, Erika M. Falcon, Cynthia Arriaga Diaz, and Brigida Rosario Jimenez for their assistance and feedback during data collection, and Marco Varela, Giovanna Vivanco, Roxy K. Malasquez, and Pilar K. Sanchez for assistance with data entry and management.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the organizations that provided funding for this research. The study “Natural infection of norovirus and sapovirus in a birth cohort in a Peruvian peri-urban community” (R01AI108695) is funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. In addition, Jessica D. Rothstein received funding from the Fulbright-Fogarty Fellowship in Public Health (co-sponsored by the Fulbright Program and the Fogarty International Center at the National Institutes of Health), a Procter & Gamble Fellowship, and a Dissertation Enhancement Award from the Center for Qualitative Studies in Health and Medicine at Johns Hopkins University.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Adugna B, Tadele H, Reta F, & Berhan Y. (2017). Determinants of exclusive breastfeeding in infants less than six months of age in Hawassa, an urban setting, Ethiopia. Int Breastfeed J, 12, 45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babakazo P, Donnen P, Akilimali P, Ali NM, & Okitolonda E. (2015). Predictors of discontinuing exclusive breastfeeding before six months among mothers in Kinshasa: A prospective study. Int Breastfeed J, 10, 19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Betran AP, de Onis M, Lauer JA, & Villar J. (2001). Ecological study of effect of breast feeding on infant mortality in Latin America. BMJ, 323, 303–306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black RE, Allen LH, Bhutta ZA, Caulfield LE, de Onis M, Ezzati M, et al. (2008). Maternal and child undernutrition: Global and regional exposures and health consequences. Lancet, 371, 243–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady JP. (2012). Marketing breast milk substitutes: Problems and perils throughout the world. Arch Dis Child, 97, 529–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brauner-Otto S, Baird S, & Ghimire D. (2019). Maternal employment and child health in Nepal: The importance of job type and timing across the child’s first five years. Soc Sci Med, 224, 94–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bueno-Gutierrez D, & Chantry C. (2015). Using the socio-ecological framework to determine breastfeeding obstacles in a low-income population in Tijuana, Mexico: Healthcare services. Breastfeed Med, 10, 124–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandhiok N, Singh Kh J, Sahu D, Singh L, & Pandey A. (2015). Changes in exclusive breastfeeding practices and its determinants in India, 1992–2006: Analysis of national survey data. Int Breastfeed J, 10, 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JW, Klassen AC, Plano Clark. V.L., & Smith, K.C. (2011). Best Practices for Mixed Methods Research in the Health Sciences. Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health, Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research. [Google Scholar]

- Dearden KA, Quan le N, Do M, Marsh DR, Pachon H, Schroeder DG, et al. (2002). Work outside the home is the primary barrier to exclusive breastfeeding in rural Viet Nam: Insights from mothers who exclusively breastfed and worked. Food Nutr Bull, 23, 101–108. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egata G, Berhane Y, & Worku A. (2013). Predictors of non-exclusive breastfeeding at 6 months among rural mothers in east Ethiopia: A community-based analytical cross-sectional study. Int Breastfeed J, 8, 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eickmann SH, de Lira PI, Lima Mde C, Coutinho SB, Teixeira Mde L, & Ashworth A. (2007). Breast feeding and mental and motor development at 12 months in a low-income population in northeast Brazil. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol, 21, 129–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank DA, Wirtz SJ, Sorenson JR, & Heeren T. (1987). Commercial discharge packs and breast-feeding counseling: Effects on infant-feeding practices in a randomized trial. Pediatrics, 80, 845–854. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim UH, & Lundman B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Educ Today, 24, 105–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guerrant RL, Oria RB, Moore SR, Oria MO, & Lima AA. (2008). Malnutrition as an enteric infectious disease with long-term effects on child development. Nutr Rev, 66, 487–505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Cordero S, Lozada-Tequeanes AL, Shamah-Levy T, Lutter C, Gonzalez de Cosio T, SaturnoHernandez P, et al. (2018). Violations of the International Code of Marketing of Breast-milk Substitutes in Mexico. Matern Child Nutr, e12682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horta BL, Loret de Mola C, & Victora CG. (2015). Breastfeeding and intelligence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Paediatr, 104, 14–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hruschka DJ, Sellen DW, Stein AD, & Martorell R. (2003). Delayed onset of lactation and risk of ending full breast-feeding early in rural Guatemala. J Nutr, 133, 2592–2599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber PJ. (1967). The behavior of maximum likelihood estimates under nonstandard conditions. Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability pp. 221–233). Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- INEI. (1988). Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud Familiar (ENDES 1986). Lima, Peru: Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. [Google Scholar]

- INEI. (1992). Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud Familiar 1991/1992. Lima, Peru: Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. [Google Scholar]

- INEI. (2001). Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud Familiar 2000. Lima, Peru: Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. [Google Scholar]

- INEI. (2006). Perú: Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud Familiar: ENDES Continua 2004–2005. Lima, Peru: Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. [Google Scholar]

- INEI. (2007). XI Censo de Población y VI de Vivienda. Lima, Peru: Instituto Nacional de Estadistica e Informatica. [Google Scholar]

- INEI. (2015). Perú: Encuesta Demográfica y de Salud Familiar-ENDES 2014. Lima, Peru: Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática. [Google Scholar]

- Jones G, Steketee RW, Black RE, Bhutta ZA, Morris SS, & Bellagio Child Survival Study G. (2003). How many child deaths can we prevent this year? Lancet, 362, 65–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kean YJ. (2014). Breaking the Rules, Stretching the Rules 2014. IBFAN: International Code Documentation Centre. [Google Scholar]

- Koh K. (2017). Maternal breastfeeding and children’s cognitive development. Soc Sci Med, 187, 101–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]