Abstract

In regions where malaria is endemic, inhabitants remain susceptible to repeated reinfection as they develop and maintain clinical immunity. This immunity includes responses to surface-exposed antigens on Plasmodium sp.-infected erythrocytes. Some of these parasite-encoded antigens may be diverse and phenotypically variable, and the ability to respond to this diversity and variability is an important component of acquired immunity. Characterizing the relative specificities of antibody responses during the acquisition of immunity and in hyperimmune individuals is thus an important adjunct to vaccine research. This is logistically difficult to do in the field but is relatively easily carried out in animal models. Infections in inbred mice with rodent malaria parasite Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi AS represent a good model for Plasmodium falciparum in humans. This model has been used in the present study in a comparative analysis of cross-reactive and specific immune responses in rodent malaria. CBA/Ca mice were rendered hyperimmune to P. chabaudi chabaudi (AS or CB lines) or Plasmodium berghei (KSP-11 line) by repeated infection with homologous parasites. Serum from P. chabaudi chabaudi AS hyperimmune mice reacted with antigens released from disrupted P. chabaudi chabaudi AS-infected erythrocytes, but P. chabaudi chabaudi CB and P. berghei KSP-11 hyperimmune serum also contained cross-reactive antibodies to these antigens. However, antibody activity directed against antigens exposed at the surfaces of intact P. chabaudi chabaudi-infected erythrocytes was mainly parasite species specific and, to a lesser extent, parasite line specific. Importantly, this response included opsonizing antibodies, which bound to infected erythrocytes, leading to their phagocytosis and destruction by macrophages. The results are discussed in the context of the role that antibodies to both variable and invariant antigens may play in protective immunity in the face of continuous susceptibility to reinfection.

Plasmodium sp. parasites demonstrate inter- and intraspecies behavioral, biochemical, genetic, and antigenic differences (17, 19). Host populations are thus infected with a range of genetically variant parasites. Furthermore, during an infection with Plasmodium falciparum in a single host, a repertoire of parasite variants (32, 37), which are antigenically distinct at the infected-erythrocyte surface, may be produced. In spite of this diversity, it is well established that people living in areas where malaria is endemic gradually develop naturally acquired immunity to the disease, a fact that has encouraged research on the development of a vaccine. However, semi-immune individuals remain susceptible to reinfection, and it may take many infections over several years before a level of immunity capable of preventing clinical disease is reached. Immunity involves both cell-mediated and humoral responses (10). The latter may develop partly through the acquisition of a repertoire of specific protective antibodies directed against polymorphic antigens sequentially expressed by antigenically distinct parasite variants. The finding that protective immunity can be passively transferred to children by immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibodies from immune adults is consistent with this suggestion (6, 26, 35). PfEMP1 (P. falciparum erythrocyte membrane protein 1) is one such polymorphic antigen exposed on the surfaces of infected erythrocytes. Antibody responses to this antigen in adults remain predominantly variant specific (32) and may be linked to protective immunity (4). However, defining the true importance of such antigens and the specific antibody responses directed to them in a natural infection is problematic. It is difficult to fully characterize either the parasite population(s) infecting individuals and populations or the immune status of those affected (29).

Inbred naive CBA/Ca mice infected with a cloned population of Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi AS experience a pattern of infection similar to that seen with P. falciparum in nonimmune humans. Initially the parasitemia is high and acute, but then partial resolution of the infection occurs and the infection goes chronic. This generally low-level, chronic phase is interspersed with recrudescences of parasitemia consisting of antigenically variant parasites (28). For these and other reasons discussed elsewhere (9, 17, 30, 31) this host-parasite combination is a useful model for certain aspects of P. falciparum infection in humans. In P. chabaudi, termination of the initial acute phase of a primary infection (crisis) is mediated by immunity consisting of both cell-mediated and antibody responses (23, 39). In P. chabaudi chabaudi AS infections the antibody-mediated part of this response is directed at parasite line-specific epitopes predominantly exposed on the surfaces of trophozoite- or schizont-infected erythrocytes (18, 30, 36). These antibodies enhance the phagocytosis and destruction of infected erythrocytes in vitro (30). Opsonizing antibodies with a similar specificity have been associated with protection in P. falciparum infections (11, 12). Full resolution of a primary P. chabaudi chabaudi AS infection renders mice relatively resistant to reinfection with the same parasite line, but they remain susceptible to reinfection with heterologous parasites (17). After six or seven further injections with large numbers of P. chabaudi chabaudi AS-parasitized erythrocytes, the resulting hyperimmune mice are refractory to further challenge with homologous parasites but remain susceptible to heterologous challenge (19; W. Jarra and K. N. Brown, unpublished results). This situation is similar to that seen in protective (hyper-) immunity in humans.

In order to further investigate the specificity of immune responses operating in such situations, we examined the specificity of antibody binding to P. chabaudi chabaudi AS-infected erythrocytes in the sera of mice hyperimmune to either the AS or CB lines of P. chabaudi chabaudi or Plasmodium berghei KSP-11. The highest levels of antibody binding were seen with P. chabaudi chabaudi AS hyperimmune serum although cross-reactive antibodies were evident in the other sera. Antibody binding to the surface of intact P. chabaudi chabaudi AS-infected erythrocyte was predominantly parasite line specific. Furthermore, a direct correlation between the amount of antibody binding to infected erythrocytes and the phagocytosis and destruction of these cells by macrophages in vitro was established.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Parasites and mice.

CBA/Ca mice, P. chabaudi chabaudi (AS and CB lines), and P. berghei (KSP-11 line) parasites were maintained and prepared as previously described (17). The parasites were originally supplied as cloned lines by D. Walliker (WHO Registry of Standard Malaria Parasites, Institute of Cell, Animal and Population Biology, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom). The erythrocytic stage of P. chabaudi chabaudi has a 24-h synchronous cycle of development. Thus, to obtain infected erythrocytes containing mature parasites, blood containing mainly trophozoites was harvested and the parasites were allowed to develop further by incubation for 2 h in culture medium (RPMI 1640, 25 mM HEPES, 25 μg of gentamicin ml−1, 2 mM glutamine, 2 mM CaCl2, 10% fetal calf serum [FCS]) at 37°C. Noninfected blood was always treated similarly as a control.

Preparation of HIS.

Primary infections were initiated in groups of mice by intraperitoneal injection of 5 × 104 infected erythrocytes of either the AS or CB lines of P. chabaudi chabaudi or the KSP-11 line of P. berghei. Parasitemia was assessed by microscopy on Giemsa-stained blood smears. When parasitemia was undetectable or barely detectable (with P. berghei KSP-11) after full resolution of this primary infection, which usually occurred about 2 to 3 months after the initial inoculation, surviving mice were injected six to eight times intraperitoneally, at approximately monthly intervals, with between 4 × 107 and 2 × 108 homologous infected erythrocytes. Hyperimmune serum (HIS) was harvested 10 to 12 days after the final infection. Normal serum (NS) was obtained from age- and weight-matched uninfected adult CBA/Ca mice.

Surface immunofluorescence antibody assay.

Antibody binding to the surfaces of infected erythrocytes was assayed as previously described (30). Infected erythrocytes and noninfected erythrocytes were obtained from CBA/Ca infected and noninfected mice, respectively, and washed three times in Krebs's buffered saline containing 0.2% glucose (KGS) (17) and 1% bovine serum albumin (KGS-BSA) by centrifugation at 1,000 × g. After 2 h in culture medium, these cells were incubated for 30 to 60 min at 37°C with plasma or serum samples diluted 1:4 to 1:10 in KGS-BSA for the individual experiments described in Results. These cells were then washed twice by resuspension in ice-cold KGS-BSA as described above. A solution containing fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-mouse IgG antibody (Sigma) diluted in KGS-BSA was used to resuspend the cell pellet, and the mixture was incubated for a further 15 to 30 min at 37°C. The cells were washed twice more as described above. In some experiments, parasite DNA in infected cells was stained with ethidium bromide to allow distinction between infected and uninfected cells. In these cases the washed cell pellet was incubated for 3 to 5 min with 50 μl of buffer containing ethidium bromide (1 μg · ml−1) and the cells were then washed twice as described above before resuspension in 1 ml of KGS-BSA. Samples were analyzed in a Becton-Dickinson FACStar Plus fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS).

ELISA.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were performed as previously described (30). To obtain the parasite antigen, P. chabaudi chabaudi AS trophozoite stage parasites were harvested from CBA/Ca mice at 40% parasitemia. The blood was passed through a column containing CF11 cellulose powder (Whatman, Maidstone, United Kingdom) to remove leukocytes, and, after two washes in KGS by centrifugation, the cell pellet was resuspended in KGS containing 0.05% saponin to lyse erythrocyte membranes. After centrifugation (at 18,000 × g) the pellet was solubilized with 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, containing 1% (wt/vol) Triton X-100 and 5 mM EDTA, and after a second centrifugation (at 200,000 × g) for 5 min at 4°C, the supernatant was retained. Each well of a 96-well microtiter plate was coated with an appropriate amount of the detergent-soluble antigen diluted in coating buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0). After overnight incubation at 4°C the plates were washed with Tris-HCl-buffered saline containing 0.05% (vol/vol) Tween 20 and any uncoated sites were blocked with BLOTTO (Tris-HCl-buffered saline containing 0.05% Tween 20 and 5% [wt/vol] dried milk). Serial dilutions in BLOTTO of either NS or serum from mice hyperimmune to P. chabaudi chabaudi AS (AS-HIS), P. chabaudi chabaudi CB (CB-HIS), or P. berghei KSP-11 (PBK-HIS) were then added. After incubation at room temperature for 2 h the plates were washed as described above. An anti-mouse Ig affinity-purified biotin-conjugated antibody (The Binding Site Co., Birmingham, United Kingdom) was added, and the plates were incubated at room temperature for 45 min. In some experiments this step was performed with biotin-conjugated antibodies specific for either mouse IgG1 or IgG2a. After six washes, exposure to streptavidin-conjugated alkaline phosphatase (Sigma) was performed, followed by six more washes and incubation with substrate buffer (10 mM diethanolamine [pH 9.5], 0.5 mM MgCl2) for 30 min. After exposure to the substrate p-nitrophenyl phosphate (Sigma), color development was measured using a Titertek Multiskan MCC 340 reader with a 405-nm filter. All samples were tested in triplicate. Background values for antibody binding were obtained from plates coated only with buffer (without antigen). These values were subtracted from the values obtained for binding to extracts from infected or uninfected erythrocytes.

Phagocytosis assay.

Macrophages were obtained from CBA/Ca mice by peritoneal lavage with 3 ml of ice-cold RPMI 1640 medium containing 5 U of heparin ml−1. An erythrocyte-free leukocyte preparation of 1 × 106 to 2 × 106 cells ml−1 was usually obtained, and 1-ml aliquots were added to Leighton tissue culture tubes (Wheaton) containing coverslips. The tubes were gassed with 7% CO2–5% O2–88% N2 and incubated for 1 to 2 h at 37°C. Cells nonadherent to the coverslips were removed by careful washing of the coverslips in situ with 1 ml of RPMI 1640 medium.

RPMI 1640 (1 ml) containing 10% (vol/vol) FCS was added to the tubes, which were then regassed and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. During this period washed infected erythrocytes from P. chabaudi chabaudi AS-infected mice and erythrocytes from uninfected mice were prepared in RPMI 1640–10% FCS. These cells were incubated at 37°C for 1 h with the different HIS samples, or with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) as a control, in a G24 environmental incubator (Edison) and shaken at 70 to 80 rpm. The cells were then pelleted by centrifugation, washed three times with RPMI 1640–10% FCS, and resuspended in the same medium, and 1 ml of cell suspension (∼108 cells) was added to each Leighton tube as appropriate. After a further incubation of 1 h at 37°C, nonadherent and noningested erythrocytes were removed from the macrophage-coated coverslips by gentle aspiration and by washing the coverslips three times with PBS. Noningested but adherent erythrocytes were then lysed by a brief (20-s) treatment with cold water, followed by an additional wash with PBS. The number of macrophages containing phagocytosed infected erythrocytes and the number containing uninfected erythrocytes were then determined semiquantitatively by microscopy and quantitatively by luminometry. Adherent cells on the coverslips were fixed with methanol and stained with Giemsa's reagent prior to examination by microscopy. The results are presented as the phagocytic index, i.e., the percentage of macrophages containing infected or uninfected erythrocytes, and the number of internalized cells that the macrophages contained (1, 2 or 3, 4 to 6, or >6). To fully quantify phagocytosis, adherent macrophages were solubilized in 400 μl of 0.5 M NaOH containing 0.025% (vol/vol) Triton X-100. Ingested erythrocyte hemoglobin and parasite-derived hemozoin were then measured by a luminescence method (38). The protoheme of the ingested hemoglobin catalyzes the production of chemiluminescence by luminol (5-amino-2,3-dihydro-1,4-phthalazinedione; Sigma Chemical Co.) and tert-butylhydroperoxide (Sigma Chemical Co.) at alkaline pH according to the reaction luminol + 2 tert-butylhydroperoxide → aminophthalic acid + N2 + 2 butanol + light. The amount of emitted light is proportional to the heme concentration and thus to the numbers of ingested cells.

In these experiments, chemiluminescence was elicited by injecting 100 μl of a tert-butylhydroperoxide–EDTA solution (containing 3.7 mM tert-butylhydroperoxide and 3 mM EDTA dissolved in 0.1 M NaOH) into a test tube containing 5 μl of solubilized macrophages in 100 μl of alkaline luminol-EDTA solution (containing 1 mg of luminol ml−1 and 3 mM EDTA dissolved in 0.1 M NaOH). Injection of tert-butylhydroperoxide triggered photon emission and counting. Since light emission reached its maximum after less than 1 s and did not decrease until 2.5 s, the integrated photon counting time was set at 2 s. Chemiluminescence was measured on a Clinilumat luminometer (Berthold Instruments; LB9502). Reagent luminescence and eigen luminescence due to macrophage heme-containing proteins were predetermined using the appropriate controls and subtracted from the results obtained with the experimental samples.

Statistical analysis.

Data were analyzed using Student's t test to compare paired results, with P values of <0.05 considered to be significant.

RESULTS

IgG in hyperimmune serum raised by P. chabaudi AS infection binds to surface antigens of intact P. chabaudi chabaudi AS-infected erythrocytes.

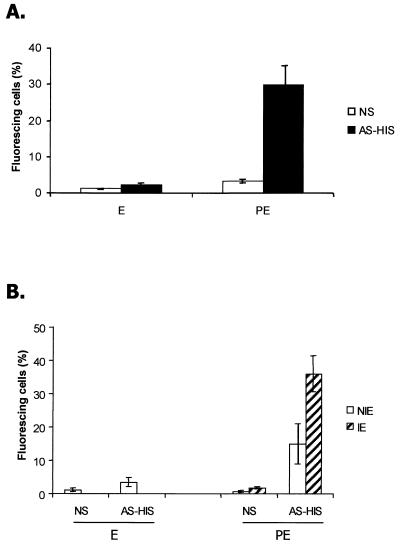

Infected erythrocytes were harvested from heavily infected mice at 2 to 3 days postinfection and processed as described in Materials and Methods to yield parasites that were predominantly mature trophozoites and schizonts. Erythrocytes from infected or noninfected mice were incubated with NS or AS-HIS, and antibody binding was detected using fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated anti-mouse IgG and FACS analysis. Anti-mouse IgG was used since the IgG fraction of AS-HIS obtained by fractionation on protein G was the only fraction showing significant binding to the surfaces of parasitized erythrocytes (data not shown). Thirty-three percent of cells from the infected population and incubated with AS-HIS had surface-bound IgG, while only 1.9% of cells bound IgG from NS (Fig. 1A), and this difference was statistically significant (P < 0.01). Only low levels of IgG binding were detectable in noninfected erythrocytes incubated with NS or AS-HIS (Fig. 1A). In some experiments infected erythrocytes were prelabeled with IgG from AS-HIS and counterstained with ethidium bromide and the double-stained cells were then examined by FACS. In these experiments it was observed that (i) significantly higher (P < 0.01) numbers of infected cells than uninfected cells bound IgG and (ii) the numbers of uninfected erythrocytes within the population of cells from infected mice that bound IgG were significantly higher than (P < 0.01) the number of IgG-labeled erythrocytes in the cell population from uninfected mice (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

immunofluorescence analysis of AS-HIS: IgG antibody binding to the surfaces of intact P. chabaudi chabaudi AS-infected erythrocytes. (A) Erythrocytes from a noninfected mouse (E) and parasitized erythrocytes (PE) containing mature parasites were incubated with NS or AS-HIS, and the numbers of cells with IgG bound to the surface were quantified in triplicate samples by FACS analysis. (B) Infected (IE) and uninfected (NIE) erythrocytes in mice infected with P. chabaudi chabaudi AS were differentiated by staining parasite DNA with ethidium bromide. Erythrocytes from uninfected mice (E) and the infected-erythrocyte population (PE) were incubated with either NS or AS-HIS. Each bar represents the percentage of cells within a window of positive fluorescence; the window for no or background fluorescence was predetermined by incubating identical samples with KGS without the primary antibody, followed by the secondary antibody. All data are the means of three independent experiments ± standard deviations.

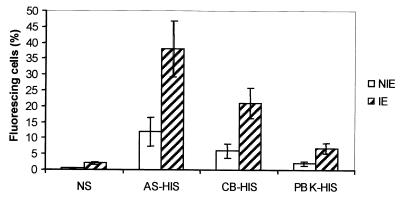

Comparison of the relative binding efficiencies to P. chabaudi chabaudi AS surface antigens of IgG from homologous and heterologous HIS.

Infected erythrocytes from P. chabaudi chabaudi AS-infected mice were preincubated with AS-HIS, CB-HIS, PBK-HIS, or NS, and the percentage of cells that bound IgG on their surfaces was determined. As shown in Fig. 2, significantly higher numbers of cells bound IgG from AS-HIS (35%) than from either PBK-HIS (7%; P < 0.01) or CB-HIS (20%; P < 0.05). Preincubation of P. chabaudi chabaudi AS-infected erythrocytes with NS produced a background level of antibody binding similar to that produced by PBK-HIS but significantly less (P < 0.01) than that produced with CB-HIS (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Immunofluorescence analysis of AS-HIS, CB-HIS, and PBK-HIS: relative binding efficiencies of IgG to surface antigens of intact P. chabaudi chabaudi AS. Erythrocytes containing mature parasites were incubated with NS, AS-HIS, CB-HIS, or PBK-HIS, and antibody binding to the cell surface was quantified in duplicate samples by FACS analysis. Infected (IE) and uninfected (NIE) erythrocytes were differentiated by staining parasite DNA with ethidium bromide. Each bar represents the proportion of cells within a window of positive fluorescence predetermined by incubating parasitized erythrocytes with KGS alone followed by the secondary antibody. All data are means of three independent experiments ± standard deviations.

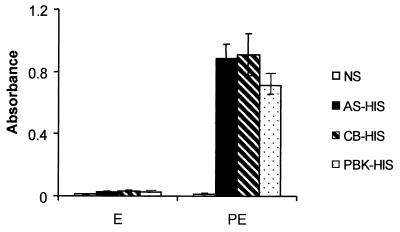

Binding of IgG to P. chabaudi chabaudi AS-infected erythrocytes: the relative binding efficiencies of antibodies from homologous and heterologous HIS.

The differences in antibody binding observed in the surface immunofluorescence assay could be due to differences in the levels of IgG isotype in the different sera under analysis. To exclude this possibility, the capacities of these sera to react with common antigens in a detergent extract of infected erythrocytes were analyzed by ELISA. None of the hyperimmune sera contained antibodies that reacted with the lysate of uninfected erythrocytes, and the reactivity of NS with the parasitized erythrocyte lysate was equally low (Fig. 3). In contrast, all three hyperimmune sera reacted strongly with antigens in the infected-erythrocyte lysate and at a level significantly above the reactivity shown by NS (P < 0.01 in all cases). There was no apparent difference in the relative levels of IgG1 and IgG2a from the different HIS samples that bound to the parasite antigen (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

ELISA analysis of IgG binding to antigens released into P. chabaudi chabaudi AS lysates. Shown is a comparison of AS-HIS, CB-HIS, and PBK-HIS. HIS and NS were tested against detergent extracts of erythrocytes from either noninfected mice (E) or P. chabaudi chabaudi AS-infected mice (PE). Total antibody binding was determined by measuring the mean absorbance obtained with the chromagenic substrate. All data are means of three independent experiments ± standard deviations.

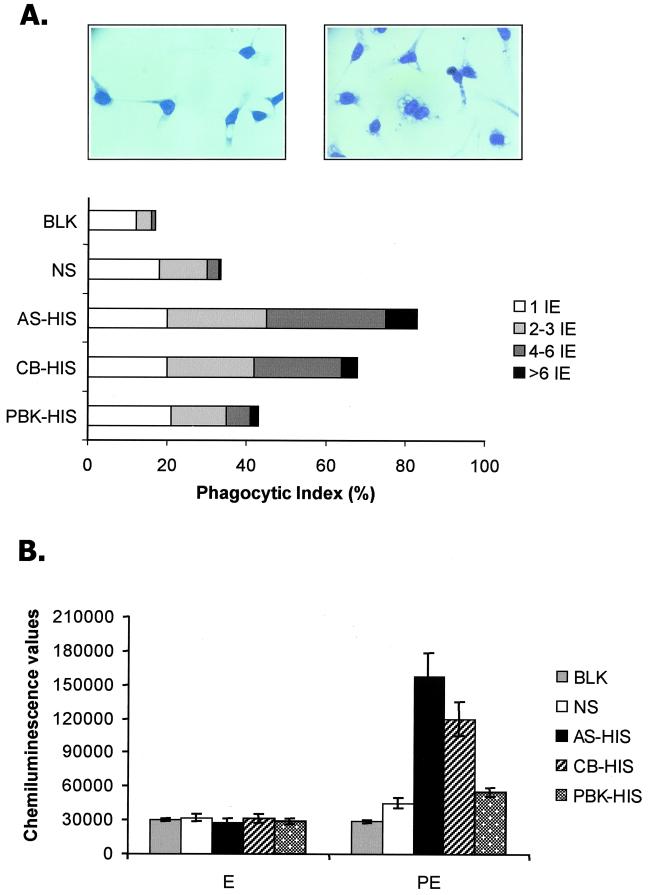

Phagocytosis of P. chabaudi chabaudi AS-infected erythrocytes by macrophages: the relative opsonizing activities of IgG from homologous and heterologous HIS.

The antibody binding assays described above do not identify a potential functional role for antibody binding to antigens exposed at the infected-erythrocyte surface. However, opsonizing antibody activity can enhance the uptake and destruction of infected erythrocytes by macrophages in vitro and might be a correlate of protective antibody activity in vivo. More than 80% of the macrophages exposed to infected erythrocytes preincubated with AS-HIS had phagocytosed infected erythrocytes, and, of these, approximately 40% contained four or more infected erythrocytes (Fig. 4A). Although a similar level of phagocytosis was observed with P. chabaudi chabaudi AS-infected erythrocytes preincubated with CB-HIS (70%), much lower levels were observed for PBK-HIS-, NS-, or KGS (control)-treated target cells (40, 35, and 20%, respectively) (Fig. 4A). In each case when infected erythrocytes were preincubated with heterologous HIS, individual macrophages contained, on average, fewer internalized infected cells than AS-HIS-preincubated cells (Fig. 4A). There was no significant difference in the percentage of phagocytic macrophages between cells preincubated with AS-HIS and those preincubated with CB-HIS. However, this difference became significant when AS-HIS was compared with either PbK-HIS, NS, or KGS (P > 0.01).

FIG. 4.

Phagocytosis of P. chabaudi chabaudi AS-infected erythrocytes by macrophages. Shown are the relative opsonizing efficiencies of IgG from homologous or heterologous HIS. P. chabaudi chabaudi AS-infected erythrocytes containing mature parasites were incubated with AS-HIS, CB-HIS, PBK-HIS, NS, or KGS and then exposed to macrophages in vitro. (A) Percentages of macrophages with internalized infected erythrocytes (phagocytic indices) and numbers of cells internalized by individual macrophages (left, NS; right, AS-HIS); (B) chemiluminescence values produced by the presence of ingested-erythrocyte hemoglobin or parasite-derived heme as detected by a luminescence method.

In some experiments, the extent of phagocytosis was quantified by determining the level of intracellular hemoglobin by a chemiluminescence method where the level of hemoglobin correlated with the numbers of internalized erythrocytes. Thus, preincubation of infected erythrocytes with AS-HIS resulted in a significantly enhanced chemiluminescence signal compared to that resulting from incubation with either NS (P > 0.01), CB-HIS (P > 0.05), PBK-HIS (P > 0.01), or the PBS control (Fig. 4B). There was no significant difference between the internalization of infected cells preincubated with PBK-HIS and that of infected cells preincubated with NS (Fig. 4B).

DISCUSSION

It is important to recognize and investigate the role played by diversification and expansion of malaria parasite antigen pools in the efficacy and specificity of the immunity induced and in immune evasion. Both specific and cross-reactive immune responses have been identified in a wide range of malaria infections including those of humans (17, 20, 30, 33). However, in many cases infections are not clonal, and the phenotype of the infecting parasites, the history of infections experienced, and the true immune status of the host cannot be determined readily (29). Using P. chabaudi chabaudi- infected erythrocytes as the target, we have analyzed the binding and specificity of antibodies generated in mice repeatedly infected with homologous blood stage parasites of the AS and CB lines of P. chabaudi chabaudi and with P. berghei KSP-11. As demonstrated by ELISA analysis, such an immunization regimen results in the induction of strong cross-reactive antibody responses to internal antigens of P. chabaudi chabaudi AS-infected erythrocytes. This finding is in agreement with previous results, as cross-reactive antibodies are also found in acute-phase plasma taken from P. chabaudi chabaudi AS-infected mice undergoing crisis and in the serum from animals which had recovered from a single or multiple reinfection episodes (19, 30). In contrast, antibody responses in HIS to antigens on the surface of the infected erythrocyte are largely parasite species and, to a lesser extent, parasite line specific, as demonstrated here by surface immunofluorescence and the phagocytosis assay. The cross-reactivity of antibodies induced in CB hyperimmune mice correlated with the higher level of phagocytosis observed in vitro when cells preincubated with CB-HIS were compared to those preincubated with PBK-HIS or NS. Such cross-reactivity between the AS and CB parasite lines was not observed for antibodies in serum harvested during crisis (30). This difference might reflect the appearance, due to longer or greater exposure to parasite antigens, of a response capable of recognizing invariant or shared epitopes, thus transcending parasite variant and line antigenic differences.

Antibody binding to the surfaces of noninfected erythrocytes in infected blood was significantly higher than binding to noninfected erythrocytes from normal mice. This difference could be explained by the adherence of parasite-derived antigens (during schizont rupture) to, or their interaction with, the surfaces of neighboring noninfected erythrocytes. It is also known that erythrocytes infected with Plasmodium show not only changes in their membranes due to the presence of parasite proteins but also modification of naturally occurring host cell proteins, such as band 3 (1, 40). Whether band-3 modification occurs only in infected erythrocytes or also in some noninfected erythrocytes during malaria infections is not known. The fact that noninfected erythrocytes can be recognized by an antibody of a malaria infection might reflect the in vivo clearance of both infected and noninfected erythrocytes, increasing the risk of anemia in malaria infections. However, in the present study, when infected blood was incubated with HIS and exposed to macrophages, little or no phagocytosis of noninfected erythrocytes was observed (results not shown).

The immune mechanisms by which malaria parasites are neutralized or eliminated and the identity of the protective antigens involved have been extensively studied (10, 15, 22). The relative contributions of these antigens to the triggering of cell- and antibody-mediated protective immune responses and the relative specificities of these responses have yet to be fully determined.

Antibodies in HIS bind to antigens exposed at the surfaces of P. chabaudi chabaudi AS-infected erythrocytes as well as to antigens only exposed in disrupted target cells. Surface-exposed antigens in P. falciparum might include PfEMP-1, Pf332, PfAARP1 (asparagine- and aspartate-rich protein 1), and rifins (3, 5, 8, 14, 21, 24). Several of these antigens are coded for by multigene families, giving them the potential for extensive diversity and variability. At present it is not known if homologues of these antigens for P. chabaudi chabaudi exist. Antigens of the merozoite apical complex (e.g., AMA-1, RAP1, and RAP2) or proteins exposed on the merozoite surface in developing schizonts (e.g., MSP-1) also induce strong antibody responses in a number of malaria infections. In the present study it is possible that one or several of these (internal) antigens are recognized by the antibody in the ELISA. Certainly homologues of MSP-1 and AMA-1 in P. chabaudi chabaudi have been characterized (25, 27). However, these antigens are not encoded by multigene families and are not considered to be clonally variable, and the immune responses they induce are often specific for the immunizing parasite line (7, 16, 34).

For P. falciparum, it has been suggested that variant-specific antibodies against antigens (such as PfEMP-1) exposed at the infected-erythrocyte surface are important in the acquisition of immunity in children and in maintaining immunity throughout life (4). Others have proposed that (in adults) antibodies to nonvariable antigens are involved in strain-transcending immunity (2, 13). Antibodies against invariant epitopes on surface-exposed antigens of infected erythrocytes have been identified in adult serum (24). However, the antibody response to phenotypically variable parasite surface antigens (as measured by agglutination of infected cells) remains predominantly variant specific (32). This situation in humans infected with P. falciparum is similar to that shown here for P. chabaudi chabaudi AS infections in mice.

P. chabaudi chabaudi AS also undergoes antigenic variation, and antibody responses to variant-specific epitopes of antigens exposed at the surfaces of infected erythrocytes may also be important in protection (28, 30). The identification and characterization of the genes that code for these potentially important proteins in P. chabaudi chabaudi are being actively pursued.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Chris Atkins for help with the FACS analysis and Keiran O'Dea for valuable discussions.

Maria M. Mota was supported by “Programa Ciência” (BM2612/92), JNICT, Portugal.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aikawa M, Udeinya I J, Rabbege J, Dayan M, Leech J H, Howard R J, Miller L H. Structural alteration of the membrane of erythrocytes infected with Plasmodium falciparum. J Protozool. 1995;32:424–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1985.tb04038.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anita R, Nowak M A, Anderson R M. Antigenic variation and the within-host dynamics of parasites. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:985–989. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.3.985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barale J C, Candelle D, Attal-Bonnefoy G, Dehoux P, Bonnefoy S, Pereira da Silva L, Lansley G. Plasmodium falciparum AARP1, a giant protein containing repeated motifs rich in asparagin and aspartate residues, is associated with the infected erythrocyte membrane. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3003–3010. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3003-3010.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bull P C, Lowe B S, Kortok M, Molyneux C S, Newbold C I, Marsh K. Parasite antigens on the infected red cell surface are targets for naturally acquired immunity to malaria. Nat Med. 1998;4:358–360. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng Q, Cloonan N, Fisher K, Thompson J, Waine G, Lanzer M, Saul A. Stevor and rif are Plasmodium falciparum multicopy gene families which potentially encode variant antigens. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1998;97:161–176. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(98)00144-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cohen S, McGregor I A, Carrington S P. Gammaglobulin and acquired immunity to human malaria. Nature. 1961;192:733–737. doi: 10.1038/192733a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crewther P E, Matthew M L, Flegg R H, Anders R F. Protective immune responses to apical membrane antigen 1 of Plasmodium chabaudi involve recognition of strain-specific epitopes. Infect Immun. 1996;64:3310–3317. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.3310-3317.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandez V, Hommel M, Chen Q, Hagblom P, Wahlgren M. Small, clonally variant antigens expressed on the surface of the Plasmodium falciparum-infected erythrocyte are encoded by the rif gene family and are the target of human immune responses. J Exp Med. 1999;190:1393–1404. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.10.1393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gilks C F, Walliker D, Newbold C I. Relationships between sequestration, antigenic variation and chronic parasitism in Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi—a rodent malaria model. Parasite Immunol. 1990;12:45–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1990.tb00935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Good M F, Doolan D L. Immune effector mechanisms in malaria. Curr Opin Immunol. 1999;11:412–419. doi: 10.1016/S0952-7915(99)80069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Groux H, Gysin J. Opsonization as an effector mechanism in human protection against asexual blood stages of Plasmodium falciparum: functional role of IgG subclasses. Res Immunol. 1990;141:529–542. doi: 10.1016/0923-2494(90)90021-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Groux H, Perraut R, Garraud O, Poingt J P, Gysin J. Functional characterization of the antibody-mediated protection against blood stages of Plasmodium falciparum in the monkey Saimiri sciureus. Eur J Immunol. 1990;20:2317–2323. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830201022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta S, Snow R W, Donnelly C A, Marsh K, Newbold C I. Immunity to non-cerebral severe malaria is acquired after one or two infections. Nat Med. 1999;5:340–343. doi: 10.1038/6560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hinterberg, K., A. Scherf, J. Gysin, T. Toyoshima, M. Aikawa, J. C. Mazie, L. P. da Silva, and D. Mattei.Plasmodium falciparum: the Pf332 antigen is secreted from the parasite by a brefeldin A-dependent pathway and is translocated to the erythrocyte membrane via the Maurer's clefts. Exp. Parasitol. 79:279–291. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Holder A A. Malaria vaccines. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:1167–1169. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.4.1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holder A A, Freeman R R. Protective antigens of rodent and human bloodstage malaria. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B. 1984;307:171–177. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1984.0117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jarra W, Brown K N. Protective immunity to malaria: studies with cloned lines of Plasmodium chabaudi and P. berghei in CBA/Ca mice. I. The effectiveness and inter- and intra-species specificity of immunity induced by infection. Parasite Immunol. 1985;7:595–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1985.tb00103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jarra W, Brown K N. Protective immunity to malaria: studies with cloned lines of rodent malaria in CBA/Ca mice. IV. The specificity of mechanisms resulting in crisis and resolution of the primary acute phase parasitaemia of Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi and P. yoelii yoelii. Parasite Immunol. 1989;11:1–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1989.tb00644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jarra W, Hills L A, March J C, Brown K N. Protective immunity to malaria. Studies with cloned lines of Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi and P. berghei in CBA/Ca mice. II. The effectiveness and inter- or intra-species specificity of the passive transfer of immunity with serum. Parasite Immunol. 1986;8:239–254. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3024.1986.tb01036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jeffery G M. Epidemiological significance of repeated infections with homologous and heterologous strains and species of Plasmodium. Bull W H O. 1966;35:873–882. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kyes S A, Rowe J A, Kriek N, Newbold C I. Rifins: a second family of clonally variant proteins expressed on the surface of red cells infected with Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:9333–9338. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.16.9333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Langhorne J. The immune response to the blood stages of Plasmodium in animal models. Immunol Lett. 1994;41:99–102. doi: 10.1016/0165-2478(94)90115-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Langhorne J, Cross C, Seixas E, Li C, von der Weid T. A role for B cells in the development of T cell helper finction in a malaria infection in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1730–1734. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.4.1730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marsh K, Howard R J. Antigens induced on erythrocytes by P. falciparum: expression of diverse and conserved determinants. Science. 1986;231:150–153. doi: 10.1126/science.2417315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marshall V M, Peterson M G, Lew A M, Kemp D J. Structure of the apical membrane antigen I (AMA-1) of Plasmodium chabaudi. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1989;37:281–283. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(89)90160-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGregor I A, Carrington S P, Cohen S. Treatment of East African P. falciparum with West African human gammaglobulin. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1963;57:170–175. [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKean P G, O'Dea K, Brown K N. Nucleotide sequence analysis and epitope mapping of the merozoite surface protein 1 from Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi AS. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1993;62:199–209. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(93)90109-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McLean S A, Pearson C D, Phillips R S. Plasmodium chabaudi: antigenic variation during recrudescent parasitaemias in mice. Exp Parasitol. 1982;54:296–302. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(82)90038-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Miller L H, Good M F, Kaslow D C. The need for assays predictive of protection in development of malaria bloodstage vaccines. Parasitol Today. 1997;13:46–47. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(96)20063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mota M M, Brown K N, Holder A A, Jarra W. Acute Plasmodium chabaudi chabaudi malaria infection induces antibodies which bind to the surface of parasitized erythrocytes and promote their phagocytosis by macrophages in vitro. Infect Immun. 1998;66:4080–4086. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.9.4080-4086.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mota M M, Jarra W, Hirst L, Patnaik P, Holder A A. Plasmodium chabaudi infected erythrocytes adhere to CD36 and bind to microvascular endothelial cells in an organ specific way. Infect Immun. 2000;68:4135–4144. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.7.4135-4144.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Newbold C I, Pinches R, Roberts D J, Marsh K. Plasmodium falciparum: the human agglutinating antibody response to the infected red cell surface is predominantly variant specific. Exp Parasitol. 1992;75:281–292. doi: 10.1016/0014-4894(92)90213-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pazzaglia G, Woodward W E. An analysis of the relationship of host factors to clinical falciparum malaria by multiple regression techniques. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1982;31:202–210. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1982.31.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Renia L, Ling I T, Marussig M, Miltgen F, Holder A A, Mazier D. Immunization with a recombinant C-terminal fragment of Plasmodium yoelii merozoite surface protein 1 protects mice against homologous but not heterologous P. yoelii sporozoite challenge. Infect Immun. 1997;65:4419–4423. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4419-4423.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sabchareon A, Burnouf T, Ouattara D, Attanath P, Bouharoun-Taypun H, Chantavanich P, Foucault C, Chongsuphajaisiddhi T, Druilhe P. Parasitologic and clinical human response to immunoglobulin administration in falciparum malaria. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1991;45:297–308. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1991.45.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Snounou G, Jarra W, Viriyakosol S, Wood J C, Brown K N. Use of a DNA probe to analyse the dynamics of infection with rodent malaria parasites confirms that parasite clearance during crisis is predominantly strain- and species-specific. Mol Biochem Parasitol. 1989;37:37–46. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(89)90100-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Staalsoe T, Hviid L. The role of variant specific immunity in asymptomatic malaria infections: maintaining a fine balance. Parasitol Today. 1998;14:177–178. doi: 10.1016/s0169-4758(98)01228-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Turrini F, Ginsburg H, Bussolino F, Pescarmona G P, Serra M V, Arese P. Phagocytosis of Plasmodium falciparum infected human red blood cells by human monocytes: involvement of immune and non-immune determinants and dependence of parasite development stage. Blood. 1992;80:801. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Weidanz W P, Kemp J R, Batchelder J M, Cigel F K, Sandor M, Heyde H C. Plasticity of immune responses suppressing parasitemia during acute Plasmodium chabaudi malaria. J Immunol. 1999;162:7383–7388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winograd E, Greenan J R, Sherman I W. Expression of senescent antigen on erythrocytes infected with knobby variant of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:1931–1935. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.7.1931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]