Abstract

Helicobacter pylori infection of the stomach epithelium is characterized by an infiltration of polymorphonuclear and mononuclear cells. These immune cells contribute to mucosal damage which may eventually lead to gastritis, peptic ulcer, gastric cancer, and/or MALT-associated gastric lymphoma. Here we show that H. pylori inhibits its own uptake, as well as in trans the phagocytosis of Neisseria gonorrhoeae, by human and murine macrophages. This antiphagocytic activity is dependent on the presence of the cag pathogenicity island in the H. pylori genome. We demonstrate that H. pylori also expresses its antiphagocytic activity towards the myelomonocytic cell line JOSKM, thus providing a potent model for the study of the interaction between H. pylori and phagocytes. Our data were obtained using laser confocal microscopy and flow cytometry after quenching the fluorescence of labeled extracellular bacteria. The antiphagocytic activity of H. pylori may explain the persistence of H. pylori and its pathological consequences. The use of cell lines and flow cytometry will hopefully facilitate progress in our understanding of the immune escape of these persistent bacteria.

Helicobacter pylori is a microaerophilic bacterium colonizing the epithelium of the stomach of more than 50% of the population worldwide (7, 22). This gram-negative bacterium is associated with the development of gastritis, gastric and duodenal ulcer, and gastric carcinoma (37, 39). A strong infiltration of mononuclear cells and polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs) is associated with H. pylori infection, and despite a specific and unspecific immune response, H. pylori can persist for decades in the gastric epithelium (8, 11). The accumulation of phagocytic cells is correlated with the severity of the induced tissue injuries and the development of gastritis (19, 41). In a previous study, we and colleagues demonstrated that H. pylori is able to inhibit its own uptake in human monocytes and neutrophils by an active process inhibiting the global function of these professional phagocytes by involving components of the type IV secretion system. The antiphagocytic mechanism is dependent on the presence of the cag pathogenicity island (PAI) in the H. pylori genome, and only the type I strains of H. pylori, which contain the PAI, are able to inhibit their uptake by monocytes and PMNs (28). This is consistent with the observation that type I strains are more often found in patients with peptic ulcers and induce a stronger inflammatory response and tissue damage than less virulent type II strains (30, 35). However, CagA, which is translocated and phosphorylated into the host cells by a mechanism dependent on the type IV secretion system (4, 5, 24, 34, 36), is not involved in the antiphagocytic mechanism of H. pylori (28). Furthermore, extracellular adherent H. pylori is able to induce and survive the extracellular release of toxic oxygen metabolites (29). Together, these bacterial properties would be likely to increase the tissue injury induced during an H. pylori infection.

In histological sections of gastric mucosa from patients infected with H. pylori, an accumulation of lymphocytes, neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages can be detected (17). Several studies found that H. pylori was not taken up or killed by professional phagocytes unless complement or H. pylori-specific antibodies were present (2, 3, 6, 18, 23, 26). In light of previous findings of impaired ingestion of H. pylori by monocytes and neutrophils (28), we were interested in assessing the role of macrophages, the most efficient phagocytic cells, in host protection against H. pylori infection. Other pathogens also inhibit their uptake or the uptake of other nonrelated prey by professional phagocytes including macrophages. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli (EPEC) (13), Yersinia species (10, 20, 21), and Pseudomonas aeruginosa (12) use type III secretion mechanisms to insert effector proteins into the host cells (20), leading to an impairment of the general phagocytosis pathway.

In this study, we used confocal laser scanning microscopy to assess the ingestion of H. pylori by human macrophages. We showed that H. pylori is able to inhibit its uptake into macrophages. Further, analysis using flow cytometry allowed us to develop a powerful assay system for the interaction between H. pylori and professional phagocytes. Taken together our data suggest a broad inhibition of the phagocytic functions of the professional phagocytic cells present at the site of infection.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and culture conditions.

H. pylori P12 is a clinical isolate obtained from a patient with duodenal ulcer (Hamburg, Germany) (33). PAI is a mutant from P12 lacking the PAI, obtained from R. Haas (München, Germany) (40). The H. pylori strains were grown on horse blood agar plates supplemented with vancomycin (10 μg/liter), nystatin (1 μg/liter), and trimethroprim (5 μg/liter). S plates were incubated at 37°C in a microaerophilic atmosphere (generated by CampyGen; Oxoid, Basingstoke, England) and were subcultured every 2 days.

Neisseria gonorrhoeae strain N303 is a pilus-negative mutant which constitutively expresses the heparan sulfate receptor-specific Opa50 (14). N. gonorrhoeae was grown on gonococcal agar plates and subcultured daily.

Cells and culture.

JOSKM cells (25) were originally derived from a patient with chronic myelogenous leukemia in blast crisis and were obtained from the German Collection of Microorganisms, Braunschweig, Germany (DSM ACC30) (15). JOSKM cells were grown as suspensions in RPMI 1640 (Gibco BRL, Paisley, Scotland) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS; Roche, Mannheim, Germany) and 2 mM l-glutamine at 37°C in 5% CO2. Cells were subcultured every 2 days. Differentiation of the cells was initiated by adding retinoic acid (100 nM) to cultures with a density of 5 × 105 cells/ml 2 days before infection. Before differentiation, JOSKM exhibited immature monoblastoid characteristics. After treatment with retinoic acid, the cells differentiate to the monocyte/macrophage lineage (15, 25). Before infection, 5 × 105 cells in 0.5 ml of RPMI 1640 were added either on glass coverslips for confocal laser scanning microscopic analysis or in 1-ml Eppendorf tubes for fluorescence-activated cell sorter (FACS) analysis.

The murine macrophage cell line J774a (ATCC TIB-67) (27) was grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with heat-inactivated (HI) FCS and 2 mM l-glutamine at 37°C and 5% CO2 and was subcultured every 2 days. Before infection, 5 × 105 cells were allowed to adhere for at least 1 h on glass coverslips at 37°C in 5% CO2 and the cells were covered with 0.5 ml of RPMI 1640.

Peripheral venous blood of healthy donors was collected into citrate-containing tubes. Mononuclear cells were freshly isolated from the blood using Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient centrifugation (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Freiburg, Germany). The mononuclear fraction was collected, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and allowed to adhere for 1 h on glass coverslips at 37°C in 5% CO2. The nonadherent lymphocytes were removed, and the remaining attached monocytes were resuspended in 0.5 ml of RPMI 1640 before bacterial infection or in 0.5 ml of RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% HI FCS for the indicated times to differentiate the monocytes into macrophages.

Bacterial infection experiments for confocal laser scanning microscopic analysis.

H. pylori and N. gonorrhoeae were resuspended from agar plates in PBS and added to cells on glass coverslips to obtain a bacterium-to-cell ratio of 100:1 for 2 h. In the case of coinfection experiments, the cells were infected with H. pylori for 2 h before the addition of N. gonorrhoeae for two additional hours. In these cases the uptake of N. gonorrhoeae was assessed. To quantify the number of extracellular and intracellular bacteria per cell, we used immunofluorescence staining and confocal laser scanning microscopy as already described (28). Briefly, after infection on glass coverslips, the infected cells were fixed in 3.7% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C. The extracellular bacteria were stained using either rabbit anti-N. gonorrhoeae MS11 antiserum diluted 1/100 in PBS containing 10% FCS (PBS-FCS) or rabbit anti-H. pylori antiserum (NatuTec, Frankfurt, Germany) diluted 1/20 in PBS-FCS for 1 h at room temperature. Samples were then washed and stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Sigma ImmunoChemicals, St. Louis, Mo.) diluted 1/100 in PBS-FCS for 45 min. To permeabilize the cells, the samples were incubated for 15 min in 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. The samples were then incubated with rabbit anti-N. gonorrhoeae MS11 antiserum or rabbit anti-H. pylori antiserum for 1 h. Then the samples were incubated for 45 min with a mixture containing Cy5-conjugated goat anti-rabbit antibody diluted 1/100 in PBS-FCS and Texas red-conjugated phalloidin (Sigma ImmunoChemicals) diluted 1/100 in PBS-FCS to stain the actin of the cells. After washing, the coverslips were mounted in glycerol medium (Sigma Immunochemicals), sealed with nail varnish, and viewed with a Leica TCS 4D confocal laser scanning microscope (Leica Lasertechnik, Heidelberg, Germany) equipped with an argon-krypton mixed gas laser. To quantify the bacterial adherence and uptake, 50 randomly selected infected phagocytic cells were screened from the bottom to the top to determine the number of cells containing at least one intracellular bacterium.

Bacterial infection experiments for FACS analysis.

To quantify the amount of phagocytosis, we also used FACS technology. N. gonorrhoeae isolates were resuspended from agar plates in PBS and stained before infection by incubating the bacteria with TAMRA (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) for 30 min at room temperature in the dark. The labeled bacteria were washed twice in PBS before being used at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 100. In the case of coinfection experiments, H. pylori cells were resuspended from agar plates in PBS and added to cells on Eppendorf tubes to obtain a bacterium-to-cell ratio of 100:1 for 2 h. The cells were then infected with the TAMRA-labeled N. gonorrhoeae for two additional hours. In these cases the uptake of N. gonorrhoeae was assessed. To block phagocytosis, cells were incubated when indicated with cytochalasin D (10 μg/ml) 30 min at 37°C before infection. After the 2- or 4-h infection, the fluorescence of the infected cells was assessed by FACS analysis. Cells were gated using forward and side light scatter to discriminate between eukaryotic cells and bacteria. The mean fluorescence of the infected cells was then determined by using the excitation and emission filters appropriate for the TAMRA dye employed; red fluorescent emission of the infected JOSKM population was monitored by use of the FL2 channel by counting at least 10,000 cells. To quench the fluorescence of the extracellular bacteria, 0.2% trypan blue (Sigma ImmunoChemicals) was added to each tube, and the mean fluorescence was immediately counted. The difference in mean fluorescence between the untreated sample and the sample treated with trypan blue was considered to be phagocytosis. As a control for the efficiency of the quenching technique, the mean fluorescence of the labeled bacteria without the host cell was measured before and after the addition of trypan blue. All measurements were done on a FACS Calibur (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.) equipped with an argon laser operating at an excitation wavelength of 488/630 nm.

RESULTS

H. pylori resists phagocytosis by human macrophages.

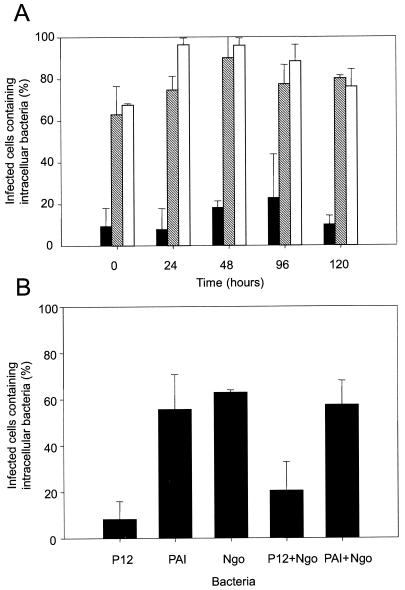

We and colleagues have previously shown that H. pylori is able to inhibit its uptake by freshly isolated neutrophils and monocytes (28). Since macrophages are known to be even more efficient than monocytes at phagocytosing foreign particles, we quantified the uptake of H. pylori by human-derived macrophages using immunofluorescent staining and confocal laser microscopic analysis. Monocytes were incubated for 1, 2, 4, and 5 days in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% HI FCS to differentiate them into macrophages. The monocytes and macrophages were then infected with H. pylori or N. gonorrhoeae for 2 h at 37°C. N. gonorrhoeae N303 strains expressing the heparan sulfate receptor-specific Opa50 adhesin (9) were found to be efficiently engulfed by macrophages at all stages of differentiation (Fig. 1A and 2A), with the percentages of infected cells containing intracellular bacteria ranging between 68 and 96%. H. pylori adhered to monocytes and to derived macrophages to the same extent as N. gonorrhoeae (data not shown), yet in the case of both monocytes and macrophages, the uptake of N. gonorrhoeae was significantly higher than the uptake of H. pylori type I strain P12 (Fig. 1A). The differential state of monocytes to macrophages did not play a role either in the adherence (not shown) or in the uptake of the type I strain of H. pylori, with the percentage of cells containing intracellular bacteria staying low and constant (below 23%) between 0 and 5 days of incubation in medium containing FCS (Fig. 1A and 2B). Together these data show that the antiphagocytic activity of H. pylori can be extended to human macrophages.

FIG. 1.

(A) H. pylori interaction with human macrophages. Human monocytes were differentiated into macrophages by incubating them for 0, 24, 48, 96, or 120 h (0, 1, 2, 4, or 5 days) in RPMI with HI FCS. The macrophages were infected with H. pylori P12 (black fill), H. pylori cag PAI (hatched), or N. gonorrhoeae N303 (white fill) for 2 h at 37°C. Samples were fluorescently immunostained for confocal laser-scanning microscopic analysis. The percentage of infected cells containing at least one intracellular bacterium was determined (percent infected cells containing intracellular bacteria). Results are the mean of at least three independent experiments. (B) Bacterial uptake by J774a cells. The murine J774a macrophage cells were infected with either H. pylori P12, PAI, or N. gonorrhoeae N303 alone or were infected with either H. pylori P12 or PAI for 2 h before the addition of N. gonorrhoeae N303. In these cases the uptake of N303 was assessed. The bacterial uptake was determined by using laser confocal microscopy. The percentage of infected cells containing at least one intracellular bacterium was determined. Results are the mean of at least three independent experiments.

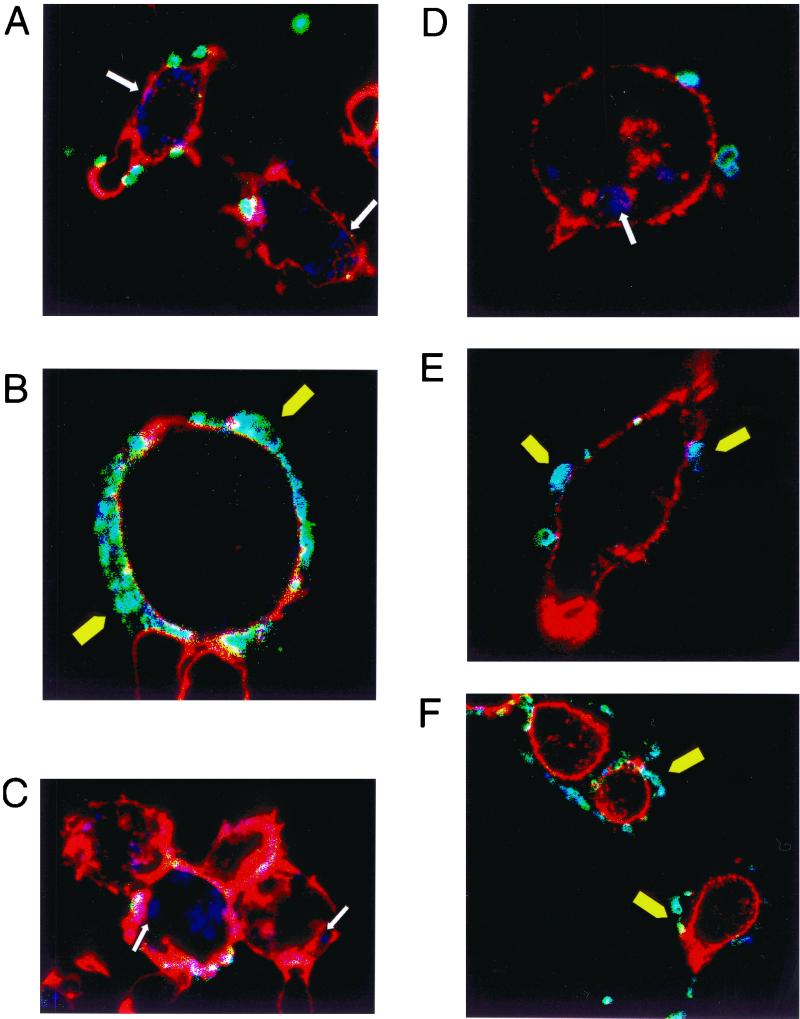

FIG. 2.

(A) Confocal picture of 5-day-derived macrophages infected with N303. (B) Confocal picture of 4-day-derived macrophages infected with P12. (C) Confocal picture of 2-day-derived macrophages infected with PAI. (D) Confocal picture of a J774a cell infected with N303. (E and F) Confocal pictures of J774a cells infected with P12 followed by an infection with N303; only the gonococci are stained. White arrow shows intracellular bacteria; yellow arrowheads show extracellular bacteria.

The antiphagocytic activity of H. pylori was dependent on the presence of the PAI in the H. pylori genome since the PAI mutant was efficiently engulfed by monocytes and macrophages (63 and 80% of infected cells contained intracellular bacteria for monocytes and for 5-day-derived macrophages, respectively) (Fig. 1A and 2C).

H. pylori resists phagocytosis by J774 murine macrophages.

Large amounts of homogenous monocyte or macrophage populations are usually difficult to obtain for in vitro studies. Therefore the use of a cell line to quantify bacterial uptake allowed us to reduce factors of variability like differences in the blood donors or in cell preparation. Thus the murine macrophage cell line J774a was used in infection experiments with H. pylori and N. gonorrhoeae. Uptake of H. pylori P12 by the murine J774a cell line was inhibited, with 8% of infected cells containing intracellular bacteria after a 2-h infection (Fig. 1B). As for human macrophages, N. gonorrhoeae bacteria were readily ingested by the cells, with 63% of cells containing intracellular gonococci (Fig. 1B and 2D). Comparable with human monocytes and macrophages, this antiphagocytic activity was PAI dependent, and 56% of the cells infected with the PAI mutant of H. pylori contained intracellular bacteria. H. pylori type I strains broadly inhibited the phagocytic activity of the J774a cells, since 2 h of incubation with H. pylori P12 also inhibited the uptake of coinfecting N. gonorrhoeae. The percentage of cells containing intracellular N. gonorrhoeae decreased from 63% in the absence of H. pylori to 21% when the cells were first incubated 2 h with P12 before the addition for two additional hours of N303 (Fig. 1B, 2E, and 2F). The mutant lacking the PAI was unable to inhibit its own uptake, and also the phagocytosis of N. gonorrhoeae was not affected when the cells were previously infected with PAI before the addition of N. gonorrhoeae (57% of cells contained intracellular gonococci after coinfection with the PAI mutant) (Fig. 1B). Together these data show that H. pylori is able to broadly inhibit the phagocytic activity of human and murine macrophages by a mechanism involving the PAI in the H. pylori genome.

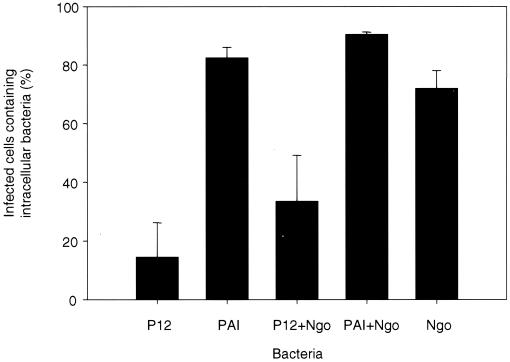

JOSKM as a model system for H. pylori phagocytosis.

As noted previously, the use of defined cell line models to study the interaction between H. pylori and phagocytic cells decreases the risk of variability obtained with freshly isolated cells. Furthermore, the number of available cells is thereby significantly increased. In order to determine if the human myelomonocytic cell line JOSKM would render a suitable model for the interaction of H. pylori with human phagocytic cells, JOSKM cells were infected for 2 h with N. gonorrhoeae or H. pylori or 2 h with H. pylori followed by a 2-h infection with N. gonorrhoeae. As was seen for human monocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages, H. pylori inhibits the phagocytic capacity of the JOSKM cells in a cag PAI-dependent manner (Fig. 3). P12 inhibits phagocytosis of itself (15% of cells containing intracellular bacteria) and of N. gonorrhoeae (72 and 34% of cells contained intracellular N. gonorrhoeae in the absence and in the presence of H. pylori, respectively). The cag PAI mutant was ingested by the JOSKM cells (83% of cells contained intracellular bacteria), and the phagocytosis of N. gonorrhoeae was not affected by the presence of the cag PAI mutant, with the percentage of cells containing intracellular N. gonorrhoeae being 72 and 91% in the absence and in the presence of the PAI mutant, respectively. The antiphagocytic activity of H. pylori therefore is similar for JOSKM and monocytes/macrophages, and the JOSKM cell line thus represents a suitable model for studying interactions between H. pylori and human phagocytes.

FIG. 3.

H. pylori inhibits phagocytosis by JOSKM cells. JOSKM cells were infected with either H. pylori P12, PAI, or N. gonorrhoeae N303 alone or were infected with either H. pylori P12 or PAI for 2 h before the addition of N. gonorrhoeae N303. In these cases the uptake of N303 was assessed. The bacterial uptake was determined by using laser confocal microscopy. The percentage of infected cells containing at least one intracellular bacterium was determined. Results are the mean of at least three independent experiments.

FACS as a reliable technique for uptake quantification.

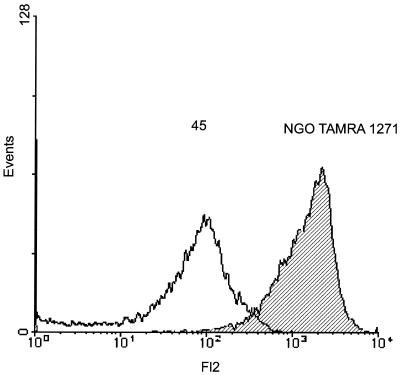

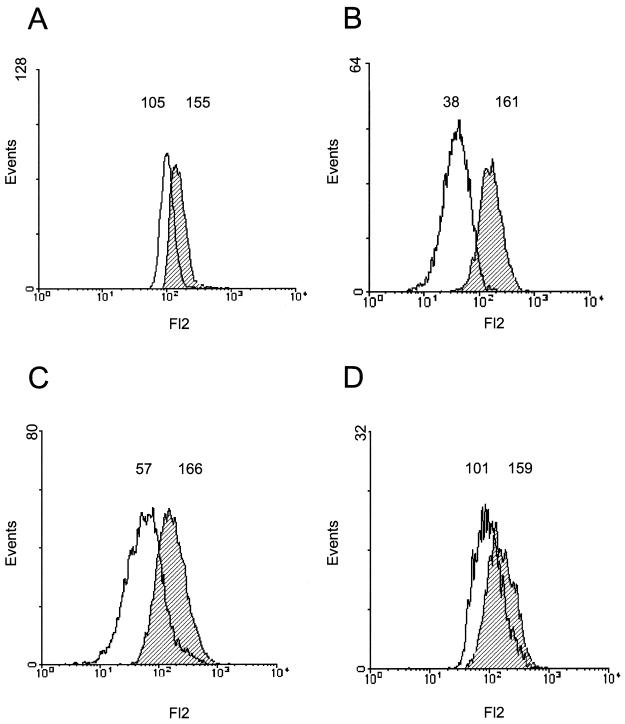

With the homogenous cell line JOSKM model we used the flow cytometry technique to further confirm our data. In preliminary experiments where H. pylori or N. gonorrhoeae was stained with TAMRA before infection, the results of uptake obtained by confocal laser microscopy were very similar to those obtained using our standard immunofluorescence staining, showing that the staining with TAMRA was very stable (data not shown). The bacteria were therefore stained with TAMRA before infection and were then used to infect JOSKM for 2 h in Eppendorf tubes. After infection, the cells were viewed on a FACS and the fluorescence of only the eukaryotic cells was taken into account. The mean fluorescence obtained after quenching the extracellular bacteria by trypan blue was considered as the percentage of phagocytosis by the cells. As a control for the staining and quenching procedure, N. gonorrhoeae isolates were stained with TAMRA and the mean fluorescence of the bacteria in the absence and in the presence of trypan blue was counted (Fig. 4). First, the fluorescence pattern of the labeled bacteria showed that almost all bacteria were stained by this method (Fig. 4). Second, after the addition of trypan blue the mean fluorescence of the bacteria decreased by 92% ± 8% (n = 3), showing that trypan blue was able to quench almost all the fluorescence from the bacteria.

FIG. 4.

Quenching of TAMRA fluorescent bacteria by trypan blue. N. gonorrhoeae N303 isolates were stained by incubating them 30 min with TAMRA in the dark. After washing, the fluorescence of the labeled bacteria was determined by flow cytometry (hatched) and the mean fluorescence of the labeled bacteria was calculated at 1,271. Trypan blue was then added to the bacteria and the fluorescence was again measured (black line). The mean fluorescence after addition of the dye was calculated at 45. The reduction in the mean fluorescence corresponds to a quenching of 97% of the initial fluorescence. This is a representative experiment of at least three different experiments with similar results.

When the cells were incubated with N. gonorrhoeae, the percent of phagocytosis (decrease in the mean fluorescence after the trypan blue addition) was 76% (Fig. 5 and Table 1). As expected, when the cells were infected with N. gonorrhoeae in the presence of cytochalasin D, there was a drastic decrease in the number of JOSKM containing fluorescent particles after the addition of trypan blue (33% of initial fluorescence), confirming the role of cytochalasin D in the inhibition of the ingestion phase of particles (42). H. pylori also reduced the phagocytosis of coincubated N. gonorrhoeae, with the neisserial phagocytosis reducing up to 32% after infection with H. pylori. This phenomenon was also PAI dependent since after infection with the PAI mutant, the phagocytosis of N. gonorrhoeae remained high and comparable with that without the addition of the PAI mutant (69 and 76%, respectively) (Fig. 5 and Table 1). In conclusion, the antiphagocytic activity of H. pylori can also be assessed by FACS analysis, which gives results similar to those of confocal laser-scanning microscopic analysis (Fig. 3).

FIG. 5.

Inhibition of phagocytosis by H. pylori assessed by fluorescence-quenched cell sorting. JOSKM cells were infected with TAMRA-labeled N. gonorrhoeae N303 in the absence (A) or in the presence (B) of cytochalasin D for 2 h or with H. pylori P12 (C) or PAI (D) for 2 h before the addition of TAMRA-labeled N. gonorrhoeae N303 for 2 h. The fluorescence of the infected JOSKM cells was assessed by flow cytometry (hatched). In all cases the uptake of N303 was assessed by quenching the fluorescence of extracellular bacteria by the addition of trypan blue. The reduction in the mean fluorescence after addition of the dye (black line) corresponds to the phagocytosis of the bacteria. This is a representative experiment of at least three different experiments with similar results. The reduction in the mean fluorescence after the trypan blue addition (phagocytosis) was as follows: (A) N303, 68%; (B) N303 + cytochalasin D, 24%; (C) P12 + N303, 34%; (D) PAI + N303, 64%.

TABLE 1.

FACS analysis of H. pylori phagocytosis inhibitiona

| Strain(s) | Phagocytosis (%)b |

|---|---|

| N303 | 76 ± 8 |

| N303 + cytochalasin D | 37 ± 14 |

| P12 + N303 | 35 ± 11 |

| PAI + N303 | 69 ± 4 |

JOSKM cells were incubated with TAMRA-labeled N303 with or without cytochalasin D. Alternatively, JOSKM cells were infected with H. pylori P12 or PAI followed by an infection with TAMRA-labeled N303. The mean fluorescence of the JOSKM-infected cells was determined before and after the addition of trypan blue, which inhibited the fluorescence of extracellular attached bacteria.

The percentage of fluorescence reduction after addition of the dye corresponds to the phagocytosis of N303. Results are the means ± the standard deviations of at least three different experiments.

DISCUSSION

One of the first steps in a host response during a bacterial infection is the recognition and ingestion of the pathogen by professional phagocytes, such as neutrophils, macrophages, and monocytes. Following an H. pylori infection, there are accumulation and activation of these cells as a result of a chemotactic response induced by H. pylori, which lead to an immune response against H. pylori (41). The ability of H. pylori to actively inhibit its uptake by all the professional phagocytes present at a site of infection is therefore a fascinating feature which may help explain how the bacteria are able to survive and to chronically colonize the gastric mucosa.

In the present study we demonstrated that H. pylori broadly inhibits the phagocytic functions of human and murine macrophages and of a monocytic cell line, JOSKM, by a mechanism dependent on the H. pylori cag PAI. The adherence and antiphagocytic activity of H. pylori was independent of the maturation stage of the macrophages and remained unchanged for monocytes differentiated for up to 5 days under a FCS-induced condition. We found that the normally efficient engulfment of N. gonorrhoeae by macrophages is impaired by H. pylori infection, showing that H. pylori prevents the global phagocytic activity of these normally very efficient phagocytic cells. Our findings also demonstrate that the previously described antiphagocytic activity of H. pylori on neutrophils and monocytes (28) has to be extended to murine and human macrophages.

Recently, Allen et al. (1) showed that type I H. pylori strains can influence their mode of uptake in macrophages. Interestingly, they observed that the bacteria are taken up by these cells yet the uptake of the bacteria and the maturation of the resulting phagosomes are delayed. The differences in the techniques used to quantify the bacterial uptake make it difficult to compare their data with our current findings. In their study the uptake is quantified by looking at actin-associated bacteria. However, it may be possible that, like EPEC (13, 31), H. pylori colocalizes with actin without being ingested. Furthermore, for fluorescence studies an MOI of 25 was used, and we and colleagues have shown previously that at a lower MOI the efficiency of the antiphagocytic activity is decreased though detectable (28). In order to unambiguously exclude any bias associated with the counting by eye of fluorescent bacteria, we developed a novel phagocytosis assay based on automated sorting of fluorescent cells. This now provides an unbiased, statistically reliable demonstration of the antiphagocytic properties of H. pylori.

The resistance to phagocytosis of H. pylori that we describe has similarities with the antiphagocytic capacity of virulent Yersinia species (10, 21, 32), EPEC (13), and P. aeruginosa (12). However, these species use components of type III secretion systems in order to inhibit their uptake into neutrophils and macrophages. We and coworkers have previously shown that H. pylori inhibits its uptake by involving components of the type IV secretion system (28). Here we show that the inhibition of uptake by macrophages is again PAI dependent. Mutants with total deletion in the PAI were readily ingested by monocytes and macrophages. This observation correlated with the results obtained by Allen and collaborators in macrophages (1) and with our previous data on monocytes and neutrophils (28). Thus, H. pylori has developed survival methods which may play a central role in the immune escape of this persistent pathogen and in the pathology or complications which result from H. pylori infection.

Differentiated JOSKM internalize gonococci to the same extent as primary monocytes from human blood (15). JOSKM cells are therefore an appropriate model for the interaction between N. gonorrhoeae and phagocytic cells (15). Our previous experiments have relied on freshly isolated human blood cells; here we compare this highly variable material with two permanent cell lines, the murine macrophage cell line J774a and the myelomonocytic cell line JOSKM. We showed here that H. pylori has the same antiphagocytic activity in these cell lines as in freshly isolated monocytes, macrophages, or PMNs. The in vitro differentiated human myelomonocytic JOSKM cells and the murine macrophage cell line J774a thus provide suitable models for the study of a variety of aspects of H. pylori-phagocyte interaction.

The phagocytosis of particles is an essential step in the host defense against microorganisms, and an efficient method to differentiate between attachment and internalization is therefore essential. Electron microscopy and confocal laser-scanning microscopy are useful tools to view particle uptake; however, many serial sections are required to analyze an entire cell and these techniques are limited by the number of available cells for in vitro analysis. Therefore, besides confocal laser-scanning microscopy, we assessed the interaction of H. pylori with JOSKM cells using flow cytometry (FACS) by quenching the fluorescence of extracellular, previously labeled bacteria. The FACS technique allowed us to count at least 10,000 cells per sample as opposed to 50 to 100 per sample in the case of confocal laser microscopic analysis. The quenching experiment has been used successfully by other workers to differentiate between intra- and extracellular bacteria (16, 38). In the present study we showed that trypan blue can abolish the fluorescence from TAMRA-conjugated microorganisms. Viable phagocytes were not stained by the trypan blue dye, indicating no penetration through the cell membrane. Flow cytometry and confocal laser microscopy are powerful tools for analyzing bacterium-host cell interactions, in particular when using fluorophores, which do not affect the viability of the bacteria or leukocytes. The described method is very sensitive for assaying the ingestion phase, as only ingested particles are fluorescent after the addition of the dye. Then the percentage of cells with fluorescent particles after addition of the dye expresses the percentage of ingesting phagocytes. The use of cell lines and flow cytometry analysis to assess the phagocytosis of H. pylori confirmed our data and will hopefully help to further elucidate the interaction between H. pylori and phagocytic cells.

The techniques that we have developed will enable us to learn more about the properties of bacterial defense of H. pylori and, in particular, to try to identify the factors responsible for the antiphagocytic activity of H. pylori. The ability of H. pylori to inhibit phagocytosis likely plays an essential role in the immune escape of this important pathogen and may explain the development of gastric-related diseases following chronic H. pylori infections.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank A. Walduck for critical reading of the manuscript. The help of V. Brinkmann in the quenching procedure is also greatly appreciated.

This work was supported by a grant of the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie to T.F.M.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen L H, Schlesinger L S, Kang B. Virulent strains of Helicobacter pylori demonstrate delayed phagocytosis and stimulate homotypic phagosome fusion in macrophages. J Exp Med. 2000;191:115–127. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.1.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersen L P, Gaarsle K. IgG Subclass antibodies against Helicobacter pylori heat stabile antigens in normal persons and in dyspeptic patients. APMIS. 1992;100:747–751. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen L P, Raskov H, Elsborg L, Holck S, Justesen T, Hansen B F, Nielsen C M, Gaarslev K. Prevalence of antibodies against heat stable antigens from Helicobacter pylori in patients with dyspeptic symptoms and normal persons. APMIS. 1992;100:779–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Asahi M, Azuma T, Ito S, Ito Y, Suto H, Nagai Y, Tsubokawa M, Tohyama Y, Maeda S, Omata M, Suzuki T, Sasakawa C. Helicobacter pylori CagA protein can be tyrosine phosphorylated in gastric epithelial cells. J Exp Med. 2000;191:593–602. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.4.593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Backert S, Ziska E, Brinkmann V, Zimmy-Arndt U, Fauconnier A, Jungblut P R, Naumann M, Meyer T F. Translocation of the Helicobacter pylori CagA protein in gastric epithelial cells by a type IV secretion apparatus encoded in the cag pathogenicity island. Cell Microbiol. 2000;2:165–171. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2000.00043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bernatowska E, Jose P, Davies H, Stephenson M, Webster D. Interaction of campylobacter species with antibody, complement and phagocytes. Gut. 1989;30:906–911. doi: 10.1136/gut.30.7.906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blaser M J, Parsonnet J. Parasitism by the “slow” bacterium Helicobacter pylori leads to altered gastric homeostasis and neoplasia. J Clin Investig. 1994;94:4–8. doi: 10.1172/JCI117336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crabtree J E. Immune and inflammatory responses to Helicobacter pylori infection. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1996;31:3–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dehio C, Gray-Owen S D, Meyer T F. The role of neisserial Opa proteins in interactions with host cells. Trends Microbiol. 1998;6:489–495. doi: 10.1016/s0966-842x(98)01365-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fallman M, Andersson K, Hakansson S, Magnusson K E, Stendahl O, Wolf-Watz H. Yersinia pseudotuberculosis inhibits Fc receptor-mediated phagocytosis in J774 cells. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3117–3124. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.8.3117-3124.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fiocca R, Luinetti O, Villani L, Chiaravalli A M, Capella C, Solcia E. Epithelial cytotoxicity, immune responses, and inflammatory components of Helicobacter pylori gastritis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1994;29:11–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frithz-Lindsten E, Du Y, Rosqvist R, Forsberg A. Intracellular targeting of exoenzyme S of Pseudomonas aeruginosa via type III-dependent translocation induces phagocytosis resistance, cytotoxicity and disruption of actin microfilaments. Mol Microbiol. 1997;25:1125–1139. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.5411905.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goosney D L, Celli J, Kenny B, Finlay B B. Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli inhibits phagocytosis. Infect Immun. 1999;67:490–495. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.2.490-495.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gray-Owen S D, Lorenzen D, Dehio C, Meyer T F. Differential Opa specificities for CD66 receptors influence tissue interactions and cellular response to Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol Microbiol. 1997;26:971–980. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.6342006.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hauck C R, Lorenzen D, Saas J, Meyer T F. An in vitro-differentiated human cell line as a model system to study the interaction of Neisseria gonorrhoeae with phagocytic cells. Infect Immun. 1997;65:1863–1869. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.5.1863-1869.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hed J. The extinction of fluorescence by crystal violet and its use to differentiate between attached and ingested microorganisms in phagocytes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;1:357–361. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kazi J I, Sinniah R, Jaffrey N A, Alam S M, Zaman V, Zuberi S J, Kazi A M. Cellular and humoral immune response in Campylobacter pylori-associated chronic gastritis. J Pathol. 1989;159:231–237. doi: 10.1002/path.1711590310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kist M, Spiegelhalder C, Moriki T, Schaefer H E. Interaction of Helicobacter pylori (strain 151) and Campylobacter coli with human peripheral polymorphonuclear granulocytes. Zentbl Bakteriol. 1993;280:58–72. doi: 10.1016/s0934-8840(11)80941-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kozol R, Domanowski A, Jaszwski R, Czanko R, McCurdy B, Prasad M, Fromm B, Calzada R. Neutrophil chemotaxis in gastric mucosa a signal to response comparison. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36:1277–1280. doi: 10.1007/BF01307522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee C A. Type III secretion systems: machines to deliver bacterial proteins into eukaryotic cells? Trends Microbiol. 1997;5:148–156. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(97)01029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lian C J, Hwang W S, Pai C H. Plasmid-mediated resistance to phagocytosis in Yersinia enterocolitica. Infect Immun. 1987;55:1176–1183. doi: 10.1128/iai.55.5.1176-1183.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marshall B J, Warren J R. Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach of patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration. Lancet. 1983;i:1311–1314. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)91816-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McKinlay A W, Young A, Russell R I, Gemmell C G. Opsonic requirements of Helicobacter pylori. J Med Microbiol. 1993;38:209–215. doi: 10.1099/00222615-38-3-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Odenbreit S, Püls J, Sedlmaier B, Gerland E, Fischer W, Haas R. Translocation of Helicobacter pylori CagA into gastric epithelial cells by type IV secretion. Science. 2000;287:1497–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohta M, Furukawa Y, Ide C, Akiyama N, Utakoji T, Miura Y, Saito M. Establishment and characterization of four human monocytoid leukemia cell lines (JOSK-I, -S, -M and -K) with capabilities of monocyte-macrophage lineage differentiation and constitutive production of interleukin 1. Cancer Res. 1986;46:3067–3074. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pruul H, Lee P C, Goodwin C S, McDonald P J. Interaction of Campylobacter pyloridis with human immune defence mechanisms. J Med Microbiol. 1987;23:233–238. doi: 10.1099/00222615-23-3-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ralph P, Nakoinz I. Phagocytosis and cytolysis by a macrophage tumour and its cloned cell line. Nature. 1975;257:393–394. doi: 10.1038/257393a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ramarao N, Gray-Owen S D, Backert S, Meyer T F. Helicobacter pylori inhibits phagocytosis by professional phagocytes involving type IV secretion components. Mol Microbiol. 2000;37:1389–1404. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02089.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ramarao N, Gray-Owen S D, Meyer T F. Helicobacter pylori induces but survives the extracellular release of oxygen radicals from professional phagocytes by using its catalase activity. Mol Microbiol. 2000;38:103–113. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.02114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rappuoli R, Lange C, Censini S, Covacci A. Pathogenicity island mediates Helicobacter pylori interaction with the host. Folia Microbiol. 1998;43:275–278. doi: 10.1007/BF02818612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rosenshine I, Ruschkowski S, Stein M, Reinscheid D J, Mills S D, Finlay B B. A pathogenic bacterium triggers epithelial signals to form a functional bacterial receptor that mediates actin pseudopod formation. EMBO J. 1996;15:2613–2624. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rosqvist R, Bolin I, Wolf W H. Inhibition of phagocytosis in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis: a virulence plasmid-encoded ability involving the Yop2b protein. Infect Immun. 1988;56:2139–2143. doi: 10.1128/iai.56.8.2139-2143.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Schmitt W, Haas R. Genetic analysis of the Helicobacter pylori vacuolating cytotoxin: structural similarities with the IgA protease type of exported protein. Mol Microbiol. 1994;12:307–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1994.tb01019.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Segal E D, Cha J, Lo J, Falkow S, Tompkins L S. Altered states: involvement of phosphorylated CagA in the induction of host cellular growth changes by Helicobacter pylori. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14559–14564. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Segal E D, Lange C, Covacci A, Tompkins L S, Falkow S. Induction of host signal transduction pathways by Helicobacter pylori. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7595–7599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stein M, Rappuoli R, Covacci A. Tyrosine phosphorylation of the Helicobacter pylori CagA antigen after cag-driven host cell translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:1263–1268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.3.1263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tytgat G N. No Helicobacter pylori, no Helicobacter pylori-associated peptic ulcer disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1995;9:39–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.1995.tb00782.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Amersfoort E S, Van Strijp J A G. Evaluation of a flow cytometric fluorescence quenching assay of phagocytosis of sensitized sheep erythrocytes by polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Cytometry. 1994;17:294–301. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990170404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wallace J L. Possible mechanisms and mediators of gastritis associated with Helicobacter pylori infection. Scand J Gastroenterol. 1991;26:65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wessler S, Höcker M, Fischer W, Wang T C, Rosewicz S, Haas R, Wiedenmann B, Meyer T F, Naumann M. Helicobacter pylori activates the histidine decarboxylase promoter through a mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway independent of pathogenicity island-encoded virulence factors. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:3629–3636. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoshida N, Granger D N, Evans D J J, Evans D G, Graham D Y, Anderson D C, Wolf R E, Kvietys P R. Mechanisms involved in Helicobacter pylori-induced inflammation. Gastroenterology. 1993;105:1431–1440. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90148-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zigmond S H, Hirsch J G. Effects of cytochalasin B on polymorphonuclear leukocyte lokomotion, phagocytosis, and glycolysis. Exp Cell Res. 1972;73:383–393. doi: 10.1016/0014-4827(72)90062-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]