Abstract

The mouth may provide an accessible model for studying bacterial interactions with human cells in vivo. Using fluorescent in situ hybridization and laser scanning confocal microscopy, we found that human buccal epithelial cells from 23 of 24 subjects were infected with intracellular bacteria, including the periodontal pathogens Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis, as well as other species which have yet to be identified. Buccal cell invasion may allow fastidious anaerobes to establish themselves in aerobic sites that otherwise present an unfavorable environment. Exfoliated buccal epithelial cells might provide a protected route for bacterial transmission between different oral sites within and between hosts.

Cellular microbiology is an emerging field which focuses on interactions between host and bacterial cells, such as intracellular invasion (15). Interactions can take place across the spectrum of pathogenicity, from acute infection to harmless commensalism. However, they may be particularly important for persistent infections with commensal organisms that become opportunistic pathogens when their environment changes. The mouth provides an excellent model for the study of persistent infections in humans. Oral bacteria are generally difficult to eradicate (24), and oral tissues are readily accessible. Periodontitis refers to inflammatory disease leading to destruction of the supporting structures of the teeth. Susceptibility appears to be related to patient genotype and to behavioral factors such as smoking (26, 29, 37). However, increased risk is consistently associated with several bacterial species. These include Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Porphyromonas gingivalis, Bacteroides forsythus, Fusobacterium nucleatum, and Prevotella intermedia (21, 43). A major objective of periodontal treatment is to eliminate pathogens below the gumline by removing bacterial biofilms from tooth roots. However, persistent infection often occurs, even when mechanical debridement is supplemented by local antibiotic therapy (31, 42). This may have adverse implications for general health. Bacteremia is induced by activities such as tooth brushing. Periodontal pathogens have been detected in atherosclerotic plaques (V. I. Harazthy, J. J. Zambon, M. Trevisan, R. Shah. M. Zeid, and R. J. Genco, Abstr. 76th Int. Assoc. Dent. Res., abstr. 273, 1998), and accumulating evidence suggests that periodontitis and periodontal pathogens are risk factors for cardiovascular disease, stroke, and low birth weight (9, 10, 32).

The anaerobic gingival crevice is considered the primary habitat for periodontal pathogens, but they also have been detected on the cheeks, tongue, and tonsils (6, 16, 25, 30, 39). Mucosal bacteria are less numerous than those in the gingival crevice, but they are thought to provide a source for re-infection following treatment (30, 31, 40, 42). Since periodontal pathogens are fastidious anaerobes, it is not clear how they survive at more-aerobic mucosal sites. One mechanism for survival might be invasion of mucosal cells. A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis both invade oral cells in tissue culture (19, 22, 27). Evidence for tissue invasion also has been seen in gingival biopsy specimens (3, 35). Invaded gingival cells are thought to provide a protected environment for these microbes.

We tested the hypothesis that periodontal pathogens can exist and grow within mucosal cells at sites remote from the gingival crevice. Bacteria associated with buccal epithelial cells were located by fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) with probes to conserved and variable regions in the ribosomal 16S subunit. This method is widely used for bacterial identification in environmental microbiology (1). Signal strength is a function of ribosomal content, so rRNA FISH favors detection of growing bacteria (1). Laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM) was used to determine whether fluorescent bacteria were intracellular. That combination of methods previously has been used to visualize Legionella invasion of a protozoan species (23). This study is the first to use them to demonstrate what appears to be an intracellular microbial community within buccal epithelial cells.

General parameters of the FISH protocol first were optimized with suspensions of P. gingivalis, A. actinomycetemcomitans, or Fusobacterium nucleatum. The latter was used as a control for nonspecific binding. A. actinomycetemcomitans ATCC 29524, A. actinomycetemcomitans SUNY 465 (from Mark C. Herzberg), and F. nucleatum ATCC 10953 from frozen stocks plated on supplemented blood agar were inoculated in Todd-Hewitt broth (THB); P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 was grown in THB supplemented with hemin (5 μg/ml) and menadione (0.5 μg/ml). All cultures were incubated at 37°C in an anaerobic chamber. Pure bacterial cultures to be used for FISH optimization were grown to log phase, to maximize the number of ribosomes (1).

Probes for species-specific variable regions of A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis 16S rRNA were complementary to species-specific primers for an established multiplex PCR used to detect A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, and B. forsythus (38). Primer specificity previously had been confirmed by evaluating the multiplex assay with a series of different oral species (38). There was no FISH probe for B. forsythus, since it had not previously been reported to invade cells. Probe EUB338, which hybridizes with a region conserved in all eubacteria (41), was used as a positive control. The complementary strand to EUB338 (EubC) was used as a negative control (41). Since the complementary strand might evoke weak signals from chromosomal DNA, an Archaea-specific sequence was used as a second negative control (1). Sequences are given in Table 1. Probes were obtained as conjugates to the green fluorescent dye Oregon green 488 (Oligos Etc., Wilsonville, Oreg.).

TABLE 1.

Sequences of probes for FISH of bacterial rRNAa

| Probe | Position (bp) | Sequence | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| A. actinomycetemcomitans specific | 889–911 | 5′ CAC CAG GGC TAA ACC CCA AT 3′ | 37 |

| P. gingivalis specific | 1054–1078 | 5′ GGT TTT CAC CAT CAG TCA TCT ACA 3′ | 37 |

| EUB338 (universal for eubacteria) | 338–355 | 5′ GCT GCC TCC CGT AGG AGT 3′ | 40 |

| EUB338 complement (negative control) | 338–355 | 5′ ACT CCT ACG GGA GGC AGC 3′ | 40 |

| Archaea-specific (negative control) | 915–934 | 5′ GTG CTC CCC CGC CAA TTC CT 3′ | 1 |

References and base pair positions are relative to the E. coli rRNA sequence.

For optimization experiments, washed log-phase P. gingivalis, A. actinomycetemcomitans, or F. nucleatum suspensions in phosphate-buffered saline were fixed in 3.7% formalin, permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100, and collected on 0.2-μm-pore-size aluminum oxide membranes held in a filtration manifold (20). The aluminium oxide membranes were supported on 0.025-μm-pore-size cellulose acetate membranes. Bacteria were washed in 0.05 M phosphate buffer with 1% Nonidet and incubated for 2 h in the manifold with 50 μg of an oligonucleotide probe per ml in hybridization buffer containing 0.02 M Tris HCl, 6X SSC (1X SSC is 0.15 M NaCl plus 0.015 M sodium citrate), 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, and 0.01% polyadenylic acid. Test strains were hybridized with a different probe in each well of the filtration manifold. After hybridization, bacteria were washed twice for 20 min in 0.02 M Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate. Hybridization and wash buffers were prewarmed to temperatures ranging from 50° to 65°C and were used in different combinations. Hybridization and washing temperatures were maintained by placing the manifold in a hybridization oven. A thermistor was placed within a well of the manifold so that temperatures could be monitored directly. Bacteria were counterstained for DNA with 1 mM blue-fluorescing 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI). Prolong anti-fade reagent (Molecular Probes, Eugene, Oreg.) was drawn through the membranes, which then were mounted on glass slides under sealed coverslips.

For FISH of bacteria collected from suspensions, membranes were viewed under a 100× oil immersion objective with a conventional epifluorescence microscope coupled to a video camera. The minimum exposure setting needed to detect green fluorescent bacteria on the monitor was taken as a measure of probe signal strength.

Experiments were run at different hybridization and wash temperatures to determine conditions which maximized the signal from universal or species-specific probes relative to background from negative controls (not shown). Optimal results for all strains were obtained at a hybridization temperature of 50°C and a wash temperature of 60°C (Table 2). Under those conditions, brightly fluorescent P. gingivalis was seen only with the universal or P. gingivalis-specific probes (Fig. 1A), A. actinomycetemcomitans was seen only with the universal or A. actinomycetemcomitans-specific probes, and F. nucleatum was seen only with the universal probe. Negative controls showed only background fluorescence.

TABLE 2.

Results for FISH of bacterial suspensions and invaded KB cells at optimal hybridization and wash temperatures of 50 and 60°C, respectively

| Group and target | Detection with probe for:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A. actinomycetem- comitans | P. gingivalis | EUB338 | EubC | Archaea | |

| Bacterial suspension | |||||

| A. actinomycetemcomitans ATCC 29524 | + | − | + | − | − |

| A. actinomycetemcomitans SUNY 465 | + | − | + | − | − |

| P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 | − | + | + | − | − |

| F. nucleatum ATCC 10953 | − | − | + | − | − |

| KB cells in tissue culture | |||||

| Salmonella serovar Typhimurium ATCC 14028 | − | − | + | − | − |

| P. gingivalis ATCC 33277 | − | + | + | − | − |

| A. actinomycetemcomitans SUNY 465a | |||||

Invasion not confirmed by antibiotic protection.

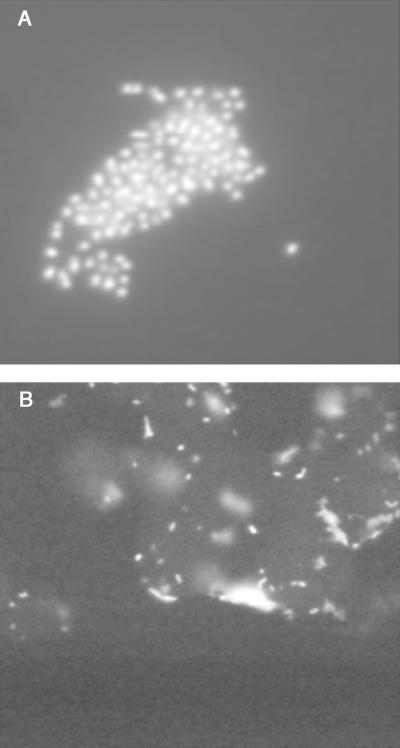

FIG. 1.

Examples of results from optimization experiments. (A) FISH of bacteria collected from suspension. The panel shows a cluster of brightly fluorescing P. gingivalis cells hybridized with the P. gingivalis-specific probe under optimal temperature conditions. (B) demonstrates FISH of tissue culture invasion. It shows a clump of KB cells from a culture that was positive for Salmonella serovar Typhimurium invasion by the antibiotic protection assay. Brightly fluorescent cell-associated bacteria were seen only with the EUB338 probe, as in this case. The KB cells are faintly visible due to autofluorescence and/or background from the oligonucleotide probe. Magnification, ×1000.

We then determined whether FISH could detect bacteria in a defined invasion model, using the KB oral cell line in tissue culture. Invasion was confirmed with a standard antibiotic protection invasion assay carried out as described by Meyer et al. (27). Briefly, confluent monolayers of the KB oral epithelial cell line (from Mark C. Herzberg) were incubated with 1.5 × 107 cells of either Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium ATCC 14028 (grown overnight in THB), P. gingivalis, or A. actinomycetemcomitans SUNY 465 per well for 90 min. The Salmonella strain was used as a positive control for invasion. Plates were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline, and extracellular bacteria were killed by incubation with gentamicin (100 μg/ml) for 90 min. Cells were collected from tissue culture plates by trypsinization. A portion of cells was lysed, and the lysate was plated to verify bacterial invasion (not shown). The remainder of cells were used for FISH.

FISH and conventional epifluorescence microscopy for KB cells were done as described above, at temperatures found to be optimal for bacterial suspensions. Nonidet was replaced with 1% GAPAL-CA630 (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.). DAPI was replaced by phalloidin conjugated with red-fluorescing ALEXAFLUOR 594 (Molecular Probes) as a counterstain for host cell actin. The universal probe revealed many brightly fluorescent Salmonellae associated with KB cells (Fig. 1B). Nonspecific background was greatly reduced in the tissue culture model relative to free bacterial suspensions, and no fluorescent bacteria were visible with any other probe (Table 2). The P. gingivalis strain used here was less invasive than Salmonella strain ATCC 14028 (not shown). However, when the tissue culture experiment was repeated with P. gingivalis, cell-associated P. gingivalis was seen only with the universal or P. gingivalis-specific probes (Table 2). Background again was reduced. We also attempted to run tissue culture experiments with A. actinomycetemcomitans, but we were unable to confirm invasion of KB cells by that species with the antibiotic protection assay.

Tissue culture studies were followed by collection of cheek epithelial cells. Informed consent was obtained according to a protocol approved by the University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board, after the nature and possible consequences of the studies were explained to a convenience sample of 24 adults including 13 males and 11 females. All were dentate except for one male with complete dentures. Cells were obtained from mucosa of both cheeks with sterile cytological brushes. A portion of each sample underwent FISH as described for KB cells. The remaining cells were assayed with an established three-species multiplex PCR (38), to verify the presence or absence of A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis. The multiplex PCR also detected B. forsythus.

The multiplex PCR protocol is fully described by Tran and Rudney (38). Briefly, DNA was extracted with QiAmp kits (Qiagen, Valencia, Calif.) using the protocol recommended by the manufacturer for buccal epithelial cells. Purified DNA was amplified in a multiplex reaction containing a single reverse primer for a universally conserved region of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene and three different forward primers directed toward 16S rRNA gene variable regions specific to A. actinomycetemcomitans, P. gingivalis, and B. forsythus. Those primers were designed to anneal to different locations along the 16S rRNA gene so that three amplicons of distinct sizes would be produced if all three species were present in the sample. The presence or absence of the species was determined by electrophoresis in ethidium bromide-stained agarose gels.

Laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM) was used to determine whether bacteria detected by FISH were inside buccal epithelial cells from human subjects. Three-dimensional reconstructions were the “gold standard” for determining if bacteria were intracellular. To reconstruct a single buccal epithelial cell hybridized with the EUB338 probe, image files acquired using Laser Sharp 3.1 software (Bio-Rad, Hercules, Calif.) on a single-photon MRC-1024 laser scanning confocal microscope (Bio-Rad) with a 60× oil immersion objective were separated into TIFF files using Confocal Assistant, version 3.07 (T. Brelje, Minneapolis, Minn.). z planes from each file then became individual TIFF images. These images were opened in Photoshop, version 5.5 (Adobe, San Jose, Calif.) to crop out adjacent cells and to outline only one cell using batch processing to automate cropping and selection functions. By limiting the analysis to a single host cell, an interpretable reconstruction could be obtained. Processed TIFF files then were opened as a stack in Velocity (version 3.1; Minnesota Datametrics, St. Paul, Minn.) for three-dimensional reconstruction. A threshold was chosen for each z plane (a cutoff point was determined by eye so that all pixel values brighter than that point were chosen for reconstruction information) at a similar point, being careful not to include too much image information on the cell z planes, and allowing for ample background (black values). Thresholding by eye introduces a range of potential settings, introducing the desire to bias the results favorably. By intentionally including as little cell area as possible at each z plane, this potential source of bias was minimized.

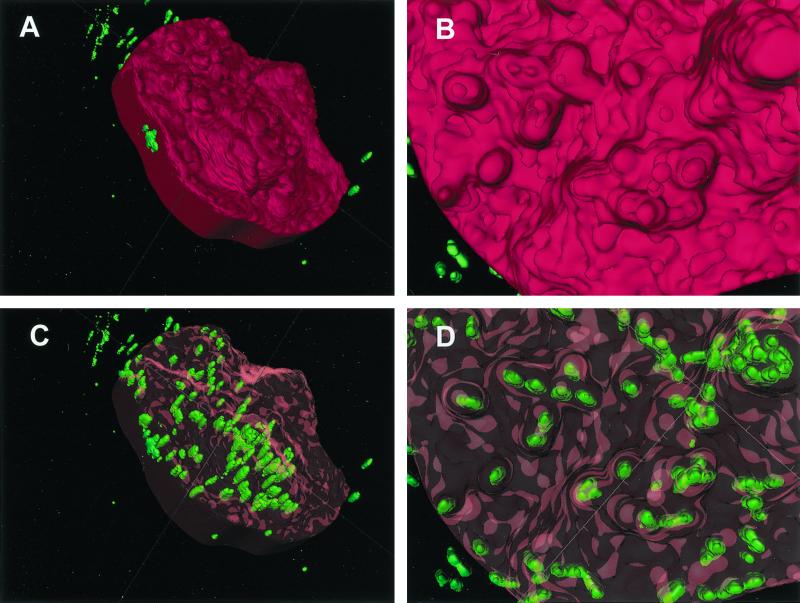

Fluorescent intracellular bacteria were clearly visible in the reconstruction (Fig. 2). They often were arranged in clusters of various sizes, although single bacteria also appeared to be present. Many clusters and single bacteria were positioned close to projections in the host cell surface; those projections sometimes approximated the shape of the underlying bacteria.

FIG. 2.

Three-dimensional reconstruction of a buccal epithelial cell from a single subject, hybridized with the EUB338 probe. (A) Surface contour of the target cell, with the surface rendered opaque in red. Editing of an adjoining cell out of this image accounts for the regular border on the left side. Green bacteria which appear to be extracellular were in fact contained within the cells that were edited out. (B) A close-up view of the opaque host cell surface reveals a very irregular contour. (C) The surface of the target cell is rendered transparent with red highlights. This reveals clusters of green bacteria which appear to be intracellular, since they cannot be seen otherwise. The elongated appearance of the bacterial cells may be an artifact of poorer resolution along the z axis. According to the scoring system described in the text, this cell would be consistent with a ranking of >100 bacteria. (D) The close-up transparent view shows that some surface protuberances were associated with bacterial clusters. However, bacteria in those clusters seemed to be located below the surface.

Procedures were the same for three-dimensional reconstructions of two cells from the same subject as above hybridized to either the P. gingivalis- or A. actinomycetemcomitans-specific probes, except that a multi-photon MRC-1024 laser scanning confocal microscope was used to acquire images and processed TIFF files then were opened with 3-D Doctor (version 3.0.3C; Able Software, Lexington, Mass.) to generate reconstructions.

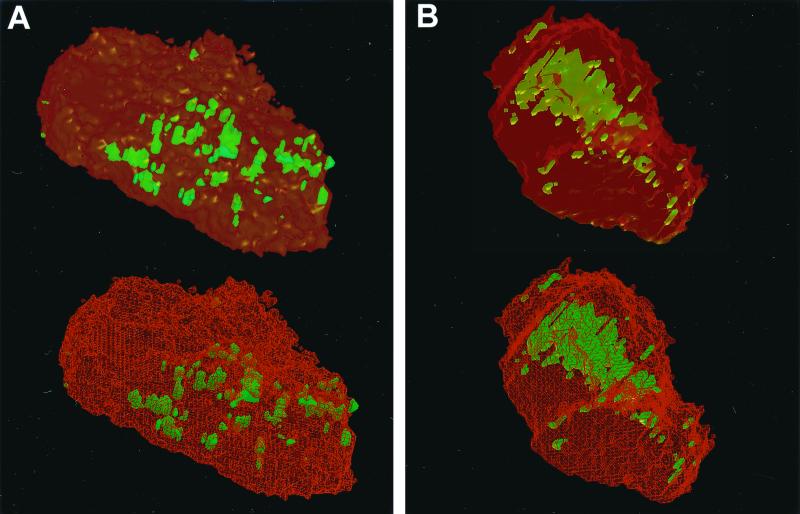

In the second reconstruction, some fluorescent P. gingivalis appeared to be on the surface or protruding through it, while larger clusters were intracellular (Fig. 3A). All bacteria labeled by the A. actinomycetemcomitans-specific probe in the third reconstruction were intracellular. Most were arranged within a large central cluster (Fig. 3B).

FIG. 3.

Three-dimensional reconstructions of two cells from the same subject as in Fig. 2 hybridized to species-specific probes. (A) Interior views of a cell hybridized to the P. gingivalis-specific probe. Adjoining cells have been edited out of the image. The surface is shown in transparent (top) and wireframe (bottom) formats. The transparent format is similar to that used in Fig. 2C and D. The wireframe format shows the cell surface as a scaffold in red. A relatively small number of green bacteria were close to or on the cell surface. They are not covered by red scaffolding in the wireframe view. It was clear that large masses of bacteria were contained within the cell from the fact that they were covered by the red scaffold in the wireframe view. According to the scoring system described in the text, this cell would be ranked as having 20 to 100 bacteria (recognizing that the number of bacteria in large clusters cannot be estimated precisely). (B) Cell hybridized to the A. actinomycetemcomitans-specific probe, shown in transparent (top) and wireframe (bottom) formats. In this example, all green bacteria were intracellular. This is apparent from their position beneath the red scaffold in the wireframe view. There was a massive cluster in the center of the cell. According to the scoring system described in the text, this cell would be ranked as having 20 to 100 bacteria (although the number of bacteria in the large central cluster is difficult to estimate).

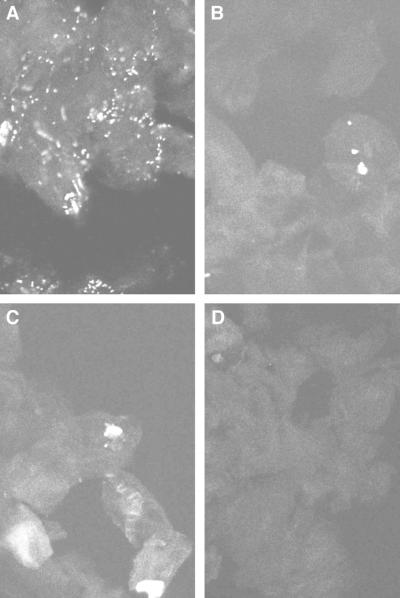

The three-dimensional reconstructions suggested that intracellular bacteria could be localized by visual examination of z-axis sections. For routine confocal analysis of buccal epithelial cells from all 24 subjects, image files acquired using Laser Sharp 3.1 software (Bio-Rad) on a single-photon MRC-1024 laser scanning confocal microscope (Bio-Rad) were separated into TIFF files using Confocal Assistant, version 3.07. z planes from each file then became individual TIFF images (Fig. 4). For each probe, subjects were ranked along a semiquantitative scale based on estimated numbers of fluorescent intracellular bacteria within the stack of images for a field. The ranks used were 0, 1 to 20, 20 to 100, or >100. Friedman's two-way analysis of variance and Wilcoxon paired tests were used to compare ranks for each probe within subjects (alpha = 0.05).

FIG. 4.

z-Axis sections of buccal cells from a single subject, hybridized with four different probes. This person is representative of the most common scoring pattern among the sample population (9 of 24 subjects). Many fluorescent intracellular bacteria could be seen with the EUB338 probe, and this field was scored as showing >100 bacteria (A). Much smaller numbers of bacteria were detected with the A. actinomycetemcomitans-specific probe (B), or P. gingivalis-specific probe (C), with the signal appearing to come from bacteria in clusters. Both of those fields were ranked as showing 1 to 20 bacteria. No bacteria at all could be seen with the negative control probe complementary to the EUB338 probe (D). Magnification, ×600.

Buccal epithelial cells with intracellular bacteria were detected in 23 persons. All of those people were positive for the universal, A. actinomycetemcomitans-specific, and P. gingivalis-specific probes. Cells with labeled bacteria were interspersed with cells that gave no signal. No intracellular bacteria were seen with either negative control probe (Fig. 4). Only the edentulous subject was negative for all five probes.

The subject used for the three-dimensional reconstructions (Fig. 2 and 3) had generally high numbers of intracellular bacteria, with scores of >100 for the EUB338 probe, and 20 to 100 for the A. actinomycetemcomitans-specific and P. gingivalis-specific probes. Figure 4 shows z-plane images for a single subject representative of the most common scoring pattern, with a universal probe score >100 and scores of 1 to 20 for both species-specific probes (9 of 24 persons). As with the three-dimensional reconstructions, the strongest signals for species-specific probes were obtained from what appeared to be clusters of bacteria.

The modal value for the EUB338 probe was significantly higher (P < 0.001) than the modes for either species-specific probe, which were not different from each other. The universal probe revealed >100 bacteria in 18 of 24 subjects. Modal values were 1 to 20 bacteria for both species-specific probes (Table 3). Species-specific probe scores were never higher than the universal probe score.

TABLE 3.

Intracellular bacteria per field for each species-specific and universal probe

| Rank | No. of subjects with given rank when probe specific for the following was used:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| A. actinomycetemcomitans | P. gingivalis | EUB338 | |

| 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 1–20 | 14ab | 17ab | 1 |

| 20–100 | 8 | 6 | 4 |

| >100 | 1 | 0 | 18ac |

| Total | 24 | 24 | 24 |

Modal value for the probe.

A. actinomycetemcomitans- and P. gingivalis-specific modes not significantly different from each other by Wilcoxon paired test (alpha = 0.05).

The EUB338 mode is significantly different from A. actinomycetemcomitans- and P. gingivalis-specific modes by Wilcoxon paired tests (P < 0.001).

FISH appeared to be more sensitive than the multiplex PCR, since five and nine subjects were negative by PCR for A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis respectively. Four and eight of those subjects were positive for 1 to 20 or 20 to 100 bacteria by FISH (Table 4). Only the edentulous subject was negative by both FISH and PCR. Although we did not use a FISH probe for B. forsythus, the multiplex PCR detected it in 18 buccal samples.

TABLE 4.

The presence or absence of bacteria in buccal cell samples from 24 persons as determined by FISH and multiplex PCR

| Bacterium and presence and/or absence data | No. of subjects |

|---|---|

| A. actinomycetemcomitans | |

| Present by FISH, present by PCR | 19 |

| Present by FISH, absent by PCR | 4 |

| Absent by FISH, present by PCR | 0 |

| Absent by FISH, absent by PCR | 1 |

| P. gingivalis | |

| Present by FISH, present by PCR | 15 |

| Present by FISH, absent by PCR | 8 |

| Absent by FISH, present by PCR | 0 |

| Absent by FISH, absent by PCR | 1 |

Our findings from three-dimensional reconstruction and z-axis sectioning support the hypothesis that periodontal pathogens can exist and grow within mucosal cells at sites remote from the gingival crevice. Both A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis grow within cells in tissue culture, and our z-plane FISH images are similar to pictures obtained by immunofluorescence microscopy of cells invaded in vitro (19, 22, 27). FISH with rRNA probes favors detection of bacteria containing large number of ribosomes (1). Bacteria in buccal epithelial cells thus are likely to have been alive. Intracellular bacteria close to the host cell surface have been observed by immunofluorescence microscopy in tissue culture models of A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis invasion, and that also was seen in the three-dimensional reconstructions shown in Fig. 2 and 3. Both species invade by coopting elements of the cytoskeleton, and A. actinomycetemcomitans also has been shown to exploit host cell microtubules to create protrusions it uses for cell-to-cell exchange (19, 22, 27, 28, 36). P. gingivalis has been observed to form aggregates on endothelial cell surfaces during the process of invasion, and those aggregates persist as bacteria are internalized within autophagosomes (34). In that respect, it is interesting that most of the bacteria detected by both our species-specific probes appeared to be in clusters.

The rapid turnover of cells on mucosal surfaces may deter the establishment of large microbial populations, and low numbers of A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis cells in fact were seen with species-specific probes. It is not yet clear whether those two species are able to maintain themselves in the absence of a gingival crevice. Previous studies done by microbial culture have reported that A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis disappear from the mouth when all teeth are removed (7, 8). The negative results for the edentulous subject are interesting in that respect. One also might expect these organisms to be absent before teeth erupt, but P. gingivalis has been detected by PCR on the mucosa of predentate infants (25). Differences in the sensitivity of detection between culture and PCR may account for those conflicting findings. However, culture-based studies of A. actinomycetemcomitans in periodontally healthy adults found that this species could be detected on mucosae of persons who were negative for subgingival colonization (30). The possibility that mucosal populations are self-sustaining thus cannot be ruled out.

A. actinomycetemcomitans and P. gingivalis have displayed properties in tissue culture models that might indicate a potential for mucosal persistence. A. actinomycetemcomitans readily transfers itself between KB cells (27). In the mouth, this might act as a mechanism for evading elimination by exfoliation. P. gingivalis persists intracellularly for many days in tissue culture (22). In an invasion experiment where artificial layers of epithelial cells were created in vitro, intracellular P. gingivalis cells first were detected by electron microscopy in the outermost layers. As time progressed, bacteria also appeared within cells in deeper layers. Thus, P. gingivalis also may avoid exfoliation by moving from cell to cell (33).

A certain amount of loss to exfoliation might be beneficial to mucosal intracellular microbes, since it would allow their transmission within and between hosts. Bacteria inside shed cells should be protected from extracellular oxygen in saliva, salivary agglutinins, and salivary antimicrobial proteins during transit. Some shed cells might by chance pass close enough to the gingival crevice for intracellular bacteria to transfer there. This could contribute to reinfection after periodontal treatment. Oral bacteria appear to be transmitted to new hosts mainly by saliva exchange between parents, children, and spouses (2, 40). Some of that transmission might involve the exchange of infected exfoliated cells. Further studies are needed to investigate this potential mechanism for bacterial persistence and spread.

Significantly larger numbers of intracellular bacteria were seen with the universal probe, which suggests that multiple oral species are invasive. It will be important to identify all intracellular species. Recent studies have shown invasion of cultured endothelial cells by P. gingivalis and also P. intermedia, so mucosal invaders may be potential agents of systemic as well as oral pathology (9, 11). Potential mucosal invaders may include P. intermedia and F. nucleatum. Both those species have been cultured from mucosae of predentate, dentate, and edentulous subjects (8, 12, 13), and both recently have been shown to invade epithelial cells in vitro (11, 14). B. forsythus has shown only a weak tendency to invade cells in tissue culture (14). However, our frequent detection of B. forsythus by PCR may indicate that further investigation in buccal cells is warranted. Streptococcus pyogenes and Streptococcus pneumoniae can invade cultured epithelial cells (4, 5), and the possibility that related oral streptococci may share this property also should be considered. It is becoming ever more apparent from rRNA-based studies that many oral species have never been cultured (18). Species that have not been grown cannot be tested for invasion in tissue culture. However, it still might be possible to detect them by FISH of mucosal cells.

In each sample, there were many cells in which bacteria could not be detected. Those cells either contained no bacteria or else contained bacteria that could not be seen by rRNA FISH because they were dead or inactive. Differences in the ability of subpopulations of mucosal cells to mount a defense by producing antimicrobial peptides or cytokines might influence their susceptibility or resistance to invasion (15). A recent study suggests an example. Exposure to F. nucleatum increased expression of the antimicrobial peptide human beta-defensin-2 by primary cultures of gingival epithelial cells. However, immunohistochemistry suggested that this increase was limited to a subset of the cells in culture (17). Further studies may help to clarify the role of host cell response in the process of mucosal invasion.

Subjects in this study were natives of nine different countries, which suggests that mucosal colonization may be widespread in humans. Much more needs to be learned about the distribution of intracellular bacteria in persons of various ages and clinical conditions. Individual differences in the extent of invasion could be discerned in our findings. Such differences likewise need to be explored, to see how they may affect risks for oral and systemic diseases.

Acknowledgments

This study was a project of the Minnesota Oral Health Clinical Research Center, supported by Public Health Service grant P30 DE 09737 from the National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR), with additional support from NIDCR grant R01 DE 07233.

We thank M. C. Herzberg, B. L. Pihlstrom, C. F. Schachtele, and G. R. Germaine for comments on the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amann R I, Ludwig W, Schleifer K H. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiol Rev. 1995;59:143–169. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.1.143-169.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Asikainen S, Chen C, Slots J. Likelihood of transmitting Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and Porphyromonas gingivalis in families with periodontitis. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1996;11:387–394. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1996.tb00200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Christersson L A. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans and localized juvenile periodontitis. Clinical, microbiologic and histologic studies. Swed Dent J Suppl. 1993;90:1–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cleary P P, LaPenta D, Vessela R, Lam H, Cue D. A globally disseminated M1 subclone of group A streptococci differs from other subclones by 70 kilobases of prophage DNA and capacity for high-frequency intracellular invasion. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5592–5597. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5592-5597.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cundell D R, Gerard N P, Gerard C, Idanpaan-Heikkila I, Tuomanen E I. Streptococcus pneumoniae anchor to activated human cells by the receptor for platelet-activating factor. Nature. 1995;377:435–438. doi: 10.1038/377435a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dahlen G, Manji F, Baelum V, Fejerskov O. Putative periodontopathogens in “diseased” and “non-diseased” persons exhibiting poor oral hygiene. J Clin Periodontol. 1992;19:35–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1992.tb01146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danser M M, Timmerman M F, van Winkelhoff A J, van der Velden U. The effect of periodontal treatment on periodontal bacteria on the oral mucous membranes. J Periodontol. 1996;67:478–485. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.5.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Danser M M, van Winkelhoff A J, van der Velden U. Periodontal bacteria colonizing oral mucous membranes in edentulous patients wearing dental implants. J Periodontol. 1997;68:209–216. doi: 10.1902/jop.1997.68.3.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deshpande R G, Khan M B, Attardo Genco C. Invasion of aortic and heart endothelial cells by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5337–5343. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.11.5337-5343.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dorn B R, Dunn W A, Jr, Progulske-Fox A. Invasion of human coronary artery cells by periodontal pathogens. Infect Immun. 1999;67:5792–5798. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.11.5792-5798.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dorn B R, Leung K L, Progulske-Fox A. Invasion of human oral epithelial cells by Prevotella intermedia. Infect Immun. 1998;66:6054–6057. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.6054-6057.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frisken K W, Higgins T, Palmer J M. The incidence of periodontopathic microorganisms in young children. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1990;5:43–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1990.tb00225.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frisken K W, Tagg J R, Laws A J, Orr M B. Suspected periodontopathic microorganisms and their oral habitats in young children. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1987;2:60–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1987.tb00291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han Y W, Shi W, Huang G T-J, Kinder Haake S, Park N-H, Kuramitsu H, Genco R J. Interactions between periodontal bacteria and human oral epithelial cells: Fusobacterium nucleatum adheres to and invades epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 2000;68:3140–3146. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.6.3140-3146.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henderson B, Wilson M, McNab R, Lax A J. Cellular microbiology: bacteria-host interactions in health and disease. Chichester, United Kingdom: Wiley; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Holtta P, Alaluusua S, Saarela M, Asikainen S. Isolation frequency and serotype distribution of mutans streptococci and Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, and clinical periodontal status in Finnish and Vietnamese children. Scand J Dent Res. 1994;102:113–119. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1994.tb01165.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Krisanaprakornkit S, Kimball J R, Weinberg A, Darveau R P, Bainbridge B W, Dale B A. Inducible expression of human β-defensin 2 by Fusobacterium nucleatum in oral epithelial cells: multiple signaling pathways and role of commensal bacteria in innate immunity and the epithelial barrier. Infect Immun. 2000;68:2907–2915. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.5.2907-2915.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kroes I, Lepp P W, Relman D A. Bacterial diversity within the human subgingival crevice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14547–14552. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.25.14547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lamont R J, Chan A, Belton C M, Izutsu K T, Vasel D, Weinberg A. Porphyromonas gingivalis invasion of gingival epithelial cells. Infect Immun. 1995;63:3878–3885. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.10.3878-3885.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lemke M J, McNamara C J, Leff L G. Comparison of methods for the concentration of bacterioplankton for in situ hybridization. J Microbiol Methods. 1997;29:23–29. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Machtei E E, Hausmann E, Dunford R, Grossi S, Ho A, Davis G, Chandler J, Zambon J, Genco R J. Longitudinal study of predictive factors for periodontal disease and tooth loss. J Clin Periodontol. 1999;26:374–380. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-051x.1999.260607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Madianos P N, Papapanou P N, Nannmark U, Dahlen G, Sandros J. Porphyromonas gingivalis FDC381 multiplies and persists within human oral epithelial cells in vitro. Infect Immun. 1996;64:660–664. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.2.660-664.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manz W, Amann R, Szewzyk R, Szewzyk U, Stenstrom T A, Hutzler P, Schleifer K H. In situ identification of Legionellaceae using 16S rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes and confocal laser scanning microscopy. Microbiolology. 1995;141:29–39. doi: 10.1099/00221287-141-1-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marsh P D. Microbial ecology of dental plaque and its significance in health and disease. Adv Dent Res. 1994;8:263–271. doi: 10.1177/08959374940080022001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McClellan D L, Griffen A L, Leys E J. Age and prevalence of Porphyromonas gingivalis in children. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2017–2019. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.8.2017-2019.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDevitt M J, Wang H Y, Knobelman C, Newman M G, di Giovine F S, Timms J, Duff G W, Kornman K S. Interleukin-1 genetic association with periodontitis in clinical practice. J Periodontol. 2000;71:156–163. doi: 10.1902/jop.2000.71.2.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meyer D H, Lippmann J E, Fives-Taylor P M. Invasion of epithelial cells by Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans: a dynamic, multistep process. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2988–2997. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.8.2988-2997.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meyer D H, Rose J E, Lippmann J E, Fives-Taylor P M. Microtubules are associated with intracellular movement and spread of the periodontopathogen Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Infect Immun. 1999;67:6518–6525. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.12.6518-6525.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Michalowicz B S. Genetic and inheritance considerations in periodontal disease. Curr Opin Periodontol. 1993;1993:11–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Muller H P, Zoller L, Eger T, Hoffmann S, Lobinsky D. Natural distribution of oral Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in young men with minimal periodontal disease. J Periodont Res. 1996;31:373–380. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1996.tb00506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nieminen A, Siren E, Wolf J, Asikainen S. Prognostic criteria for the efficiency of non-surgical periodontal therapy in advanced periodontitis. J Clin Periodontol. 1995;22:153–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1995.tb00127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Offenbacher S, Madianos P N, Champagne C M, Southerland J H, Paquette D W, Williams R C, Slade G, Beck J D. Periodontitis-atherosclerosis syndrome: an expanded model of pathogenesis. J Periodont Res. 1999;34:346–352. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1999.tb02264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Papapanou P N, Sandros J, Lindberg K, Duncan M J, Niederman R, Nannmark U. Porphyromonas gingivalis may multiply and advance within stratified human junctional epithelium in vitro. J Periodont Res. 1994;29:374–375. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1994.tb01237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Progulske-Fox A, Kozarov E, Dorn B, Dunn W, Jr, Burks J, Wu Y. Porphyromonas gingivalis virulence factors and invasion of cells of the cardiovascular system. J Periodont Res. 1999;34:393–399. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.1999.tb02272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saglie F R. Scanning electron microscope and intragingival microorganisms in periodontal diseases. Scan Microsc. 1988;2:1535–1540. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sandros J, Madianos P N, Papapanou P N. Cellular events concurrent with Porphyromonas gingivalis invasion of oral epithelium in vitro. Eur J Oral Sci. 1996;104:363–371. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.1996.tb00093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stoltenberg J L, Osborn J B, Pihlstrom B L, Herzberg M C, Aeppli D M, Wolff L F, Fischer G E. Association between cigarette smoking, bacterial pathogens, and periodontal status. J Periodontol. 1993;64:1225–1230. doi: 10.1902/jop.1993.64.12.1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tran S D, Rudney J D. Improved multiplex PCR using conserved and species-specific 16S rRNA gene primers for simultaneous detection of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans, Bacteroides forsythus, and Porphyromonas gingivalis. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:3504–3508. doi: 10.1128/jcm.37.11.3504-3508.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Van Steenbergen T J, Petit M D, Scholte L H, van der Velden U, de Graaff J. Transmission of Porphyromonas gingivalis between spouses. J Clin Periodontol. 1993;20:340–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1993.tb00370.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Von Troil-Linden B, Saarela M, Matto J, Alaluusua S, Jousimiessomer H, Asikainen S. Source of suspected periodontal pathogens re-emerging after periodontal treatment. J Clin Periodontol. 1996;23:601–607. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051x.1996.tb01831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wallner G, Amann R, Beisker W. Optimizing fluorescent in situ hybridization with rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes for flow cytometric identification of microorganisms. Cytometry. 1993;14:136–143. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990140205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wong M Y, Lu C L, Liu C M, Hou L T. Microbiological response of localized sites with recurrent periodontitis in maintenance patients treated with tetracycline fibers. J Periodontol. 1999;70:861–868. doi: 10.1902/jop.1999.70.8.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zambon J J. Periodontal diseases: microbial factors. Ann Periodontol. 1996;1:879–925. doi: 10.1902/annals.1996.1.1.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]