Abstract

The protective effects of intranasal administration of amphotericin B (AmB), human SP-A, SP-D and a 60-kDa fragment of SP-D (rSP-D) were examined in a murine model of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA). The untreated group of IPA mice showed no survival at 7 days postinfection. Treatment with AmB, SP-D, and rSP-D increased the survival rate to 80, 60, and 80%, respectively, suggesting that SP-D (and rSP-D) can protect immunosuppressed mice from an otherwise fatal challenge with Aspergillus fumigatus conidia.

Aspergillus spp. are increasingly recognized as major fungal pathogens in immunocompromised or neutropenic patients, and Aspergillus fumigatus is responsible for nearly 90% of cases of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis (IPA) (7). As the incidence of AIDS, aplastic anemia, and organ transplantation increases and the use of chronic glucocorticoid treatment and aggressive antineoplastic chemotherapy regimes becomes more frequent, the number of patients susceptible to Aspergillus infection is rising. In immunocompromised or neutropenic patients, IPA, the most common form of the disease, is characterized by hyphal invasion and destruction of pulmonary tissue. Dissemination of Aspergillus infection to other organs occurs in approximately 20% of IPA cases (4). In spite of correct diagnosis and treatment, IPA results in patient mortality of greater than 80%. The mortality rate among bone marrow transplantation patients can be as high as 95% (26). Early empirical treatment with antifungal drugs, such as amphotericin B (AmB), reduces the mortality rate. However, AmB is considered highly nephrotoxic (18) and has often been found inadequate for complete elimination of the infection in the immunosuppressed subjects. Because invasive aspergillosis is extremely rare in immunocompetent individuals, therapy aimed at strengthening the host's immune response to the organisms offers a promising new approach in the treatment of this disease.

Host defense against Aspergillus infections is considered to be mediated by macrophages, neutrophils, and polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs) (6, 16, 23, 24, 25, 28). The respiratory tract appears to be the portal of entry in most cases of IPA (3). Therefore, there has been an extensive search for molecules in the lung which can selectively enhance the contribution of the innate immune mechanism of phagocytes against Aspergillus infection. Lung surfactant proteins SP-A and SP-D have potent chemotactic activity for various subsets of mononuclear leukocytes and have been shown to enhance phagocytosis and production of superoxide anion by macrophages and neutrophils (29). SP-A and SP-D, which belong to a family of proteins called collectins, are also known to interact with carbohydrate structures present on the surfaces of a wide range of pathogens, such as viruses, bacteria, and fungi, via their carbohydrate recognition domains (CRDs) and to enhance phagocytosis and killing by neutrophils and macrophages (22, 29). Collectins are composed of subunits, each of which contains a collagen-like triple-helical region, followed by an α-helical, trimerizing neck region and three CRDs at its C-terminal end. Six of these trimeric subunits make up the overall structure of SP-A, while SP-D is composed of a cruciform structure with four arms of equal lengths (10). Mice deficient in SP-A were observed to be less effective in clearing Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa and were more susceptible to lung inflammation and splenic dissemination of group B streptococci (13–15).

We have previously shown that SP-A and SP-D can bind and agglutinate A. fumigatus conidia in vitro and enhance killing of conidia by human neutrophils and macrophages via phagocytosis and superoxide anion production (17). In this study, we examined the therapeutic effect of intranasal administration of human SP-A, SP-D, and a recombinant fragment of human SP-D composed of the trimeric α-helical coiled-coil neck region and three CRDs of human SP-D (rSP-D), in a murine model of IPA. The 60-kDa rSP-D fragment, which lacks the collagen-like region present in the intact SP-D molecule, is readily produced in large amounts in Escherichia coli, and the results of this study show that it may be very suitable for use as an antifungal agent, perhaps by its addition to surfactant mixtures already in clinical use.

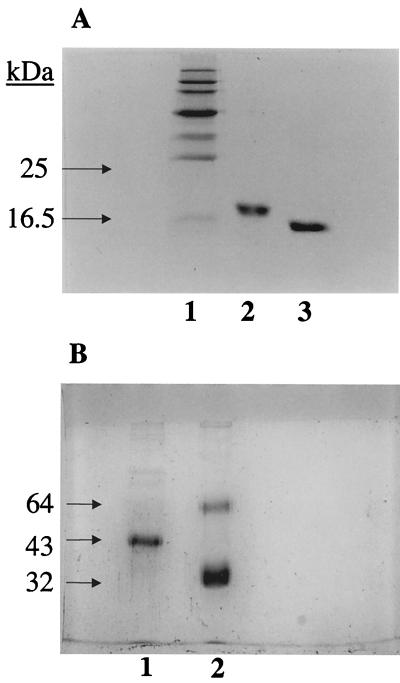

Spores from A. fumigatus (strain 285 isolated from the sputum of an allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis patient) were harvested and suspended in sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to make challenge concentrations of 108 spores/50 μl, as described earlier (2). The spore viability of challenge inoculum was assessed by plating 106 and 107 dilutions on Sabouraud dextrose agar plates. Native human SP-A and SP-D were purified from lung lavage fluid, which was obtained from alveolar proteinosis patients, as previously described (27). Both protein preparations were judged to be pure by Coomassie-stained sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (Fig. 1B), Western blotting, and amino acid composition. No contamination with immunoglobulin G (IgG), immunoglobulin M (IgM), and immunoglobulin E (IgE) antibodies was detected in the preparations by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using anti-human IgG, anti-human IgM, and anti-human IgE peroxidase conjugates, respectively. SP-A and SP-D preparations were evaluated for the presence of endotoxin using the QCL-1000 Limulus amoebocyte lysate system (BioWhittaker, Walkersville, Md.) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The assay was linear over a range of 0.1 to 1.0 EU per ml (10 EU = 1 ng of endotoxin). The amount of endotoxin present in purified SP-A was observed to be 16 pg of endotoxin per μg of SP-A, and for purified SP-D it was found to be 56 pg of endotoxin per μg of SP-D. Intratracheal administration of 10 ng of lipopolysaccharide (endotoxin) per kg of body weight to rabbits has been reported not to significantly increase tumor necrosis factor alpha production or lung PMN accumulation (this dose is equivalent to 200 pg of lipopolysaccharide per mouse [11]). The SP-A and SP-D preparations were also examined for their activities against A. fumigatus conidia by an in vitro killing assay and a conidia agglutination assay, as previously described (17, 27).

FIG. 1.

(A) SDS-PAGE (15%, wt/vol) analysis of purified preparations of rSP-D under reducing as well as nonreducing conditions (Coomassie stained). A recombinant fragment composed of the trimeric, α-helical coiled-coil neck region and three CRDs of human SP-D (rSP-D) was expressed in E. coli in the inclusion bodies and purified. The recombinant protein behaved as a homotrimer of ∼60 kDa when examined by gel filtration chromatography and chemical cross-linking (data not shown). Under reducing conditions (lane 2), the protein ran as a monomer of ∼18 kDa. No higher oligomers were seen when rSP-D was run under nonreducing conditions (lane 3), showing that the trimerization was not a result of aberrant disulfide bridges between CRD regions. rSP-D was also assessed for correct folding using circular dichroism, disulfide mapping, and the determination of its crystallographic structure in complex with maltose in the carbohydrate-binding pockets (Shrive et al., unpublished data). (B) SDS-PAGE (10%, wt/vol) analysis of purified preparations of SP-D and SP-A under reducing conditions (Coomassie stained). The majority of SP-D is composed of a 43-kDa polypeptide chain, with faint bands corresponding to dimers and trimers of the 43-kDa chain (lane 1; also confirmed by immunoblotting). Two bands are seen (lane 2), a major band corresponding to the 32-kDa polypeptide chain of SP-A, together with a proportion of nonreducible dimers (64 kDa). Traces of higher oligomers and some aggregates (confirmed by immunoblotting) can also be seen. The nonreduced preparations of SP-D and SP-A behaved on SDS-PAGE as described previously (27). All of the SP-A preparation was composed of octadecamers, as judged from gel filtration and electron microscopy studies. The exact proportions of the SP-D preparation in the form of dodecamers and higher oligomers was not established.

A recombinant homotrimeric fragment composed of eight Gly-X-Y repeats of the collagen region, α-helical coiled-coil neck region, and CRDs of human SP-D (rSP-D) was expressed in Escherichia coli in the inclusion bodies and purified by a procedure involving denaturation-renaturation, ion-exchange, affinity, and gel-filtration chromatography. The recombinant preparation was judged to be pure by Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1A), immunoblotting, and amino-terminal sequencing. The purified recombinant protein was assessed for correct folding using disulfide mapping and by analysis of its crystallographic structure in complex with maltose in the carbohydrate-binding pockets (A. K. Shrive, T. J. Greenhough, P. Strong, U. Kishore, and K. B. M. Reid, unpublished data). rSP-D was also examined for its binding to simple sugars, phospholipids, and maltosyl-bovine serum albumin as described previously (12). The amount of endotoxin present in the rSP-D preparations was estimated, as described above for native SP-A and SP-D preparations, and was found to be 42 pg of endotoxin per μg of rSP-D.

A 4.16-mg/ml solution of AmB (one 50-mg vial of Fungizone; Sarabhai Chemicals, Ahmedabad, India) was prepared in 10 ml of USP (U.S. Pharmacopeia) water for injection plus 2 ml of 5% (wt/vol) dextrose water for injection. The 4.16-mg/ml solution of AmB was diluted to 2.692 mg/ml by addition of sterile PBS prior to administration to the mice. The AmB and dextrose solutions were stored in sterile bottles at 4°C in the dark and mixed immediately prior to use.

Male BALB/c mice (National Institute of Nutrition, Hyderabad, India), weighing 20 to 22 g each, were housed in polycarbonate shoebox cages bedded with material from dried corncobs. They ate a standard laboratory rodent diet and had water ad libitum. Mice were immunosuppressed by three intradermal injections of 2.5 mg of hydrocortisone acetate (Wycort) per mouse per day (125 mg per kg of body weight) 1 day before, the day of, and the day after spore challenge, as described by Allen et al. (2). Ten groups of 5 mice each were selected. On the day of spore challenge, mice were lightly anesthesized with ether and 108 spores of A. fumigatus in 50 μl of sterile PBS were administered intranasally in the groups of IPA mice, while 50 μl of PBS alone was administered to the untreated control mice. The groups of untreated control and untreated IPA mice received 50 μl of PBS alone intranasally on days 1, 2, and 3. The IPA mice showed 100% mortality at 7 days postinfection and high levels of CFU (107 CFU/g of lung tissue). Lung sections of the IPA mice showed dense growth of fungal hyphae (results not included).

All preparations for treatment were administered intranasally in 50 μl of PBS per mouse. The AmB-treated control and IPA mice received AmB (134.6 μg) only on day 1. AmB was administered only on day 1, in view of an earlier study by Allen et al. (2) which showed that a single dose of 134.6 μg of AmB per mouse administered 1 day after the spore challenge was protective for the IPA mice. The AmB group served as the positive control for the study. The SP-A-treated control and IPA mice received 3 μg of SP-A in 50 μl of PBS per mouse on days 1, 2, and 3. SP-D (1 μg in 50 μl of PBS per mouse) was given to the SP-D-treated control and IPA mouse groups on days 1, 2, and 3. Similarly, the rSP-D-treated control and IPA mice received rSP-D (4 μg in 50 μl of PBS per mouse) on days 1, 2, and 3. The selected doses of SP-A and SP-D were based on the physiological concentrations of these proteins reported in rodent lung lavage fluid: the SP-A concentration in the rat lavage has been reported to be 7.3 ± 0.8 μg/ml, and the SP-D concentration in the lavage from the C57BL/6 strain of mice 6 to 8 weeks of age was observed to be 552 ng/ml (21, 30). For human lung lavage, the SP-A concentration ranges from 1 to 10 μg/ml, and the SP-D concentration varies between 300 and 600 ng/ml (19, 20). A higher dose of rSP-D was chosen for treatment, as compared to native SP-D, since it required ∼4.5 μg of rSP-D per ml to kill conidia in vitro, as compared to a concentration of 1 μg of native SP-D per ml to bring about similar effects (T. Madan, P. Strong, M. Singh, A. C. Willis, P. U. Sarma, K. B. M. Reid, and U. Kishore, unpublished data). SP-A, SP-D, and rSP-D were administered on 3 consecutive days in view of their protein nature and hence rapid degradation and clearance from the respiratory tract. For all of the groups of mice, survival was monitored for 15 days, and the survival percentage was calculated for each group. The Fisher exact test was used to evaluate the statistical significance of the differences observed in survival percentages of various groups.

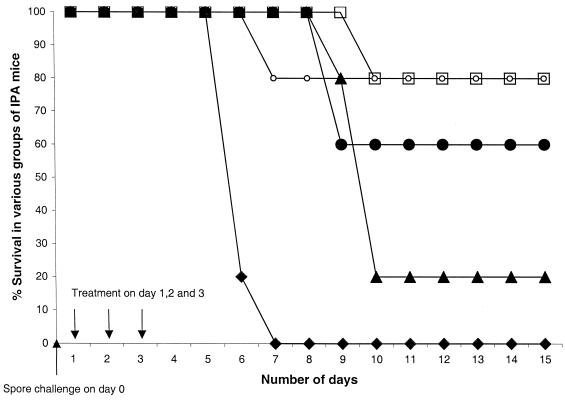

The percentages of mice surviving after the challenge with A. fumigatus spores are shown in Fig. 2. All of the control mice, which received no spores and were treated with PBS, AmB, SP-A, SP-D, or rSP-D, showed 100% survival. The untreated IPA mice showed 100% mortality by the 7th day, while all other groups of IPA mice had survivors even after the 15th day. Survival in the AmB-treated IPA mice and the rSP-D-treated groups of IPA mice was the same (80% survival) and was significantly different from that of untreated IPA mice (P < 0.025). The SP-D-treated group of IPA mice also had more survivors (60% survival) than the untreated group of IPA mice (P < 0.0850). Survival in the SP-A-treated group of IPA mice (20%) was higher than in the untreated group of IPA mice (P < 0.500) but was reduced compared to survival in the AmB-, rSP-D-, and SP-D-treated groups of IPA mice.

FIG. 2.

Percent survival of the IPA mice over 15 days after challenge with 108 spores of A. fumigatus on day 0 and subsequent treatment with PBS, AmB, SP-A, SP-D, and rSP-D on day 1: ⧫, untreated IPA mice; ○, AmB-treated IPA mice; ▴, SP-A-treated IPA mice; ●, SP-D-treated IPA mice; □, rSP-D-treated IPA mice. There were five mice in each group, and there were no deaths in any of the control groups (given PBS, SP-A, SP-D, or rSP-D), which had been immunosuppressed but not infected with A. fumigatus.

The mortality rates observed in the untreated IPA mice (100%) and the AmB-treated group of IPA mice (20%) were similar to those reported by Allen et al. (2). One plausible reason for the difference observed in the mortality rates of SP-A-treated IPA mice and SP-D-treated IPA mice may be different in vivo activities shown by SP-A and SP-D, as suggested in a recent study (binding of human SP-A but not human SP-D to A. fumigatus conidia is inhibited in the presence of hydrophobic surfactant components [1]). The molar ratio of amounts of rSP-D and SP-D administered per mouse was approximately 9.625, which may explain the differences observed in their efficacies. We are further evaluating the effects of higher doses of SP-A, SP-D, and rSP-D in IPA mice with respect to the interleukin profile, fungal load, and histopathology of lung tissue of treated IPA mice. It is also worthwhile to mention that the beneficial effects of treatment with SP-D and rSP-D were obtained using BALB/c mice exposed to conidia from a clinical isolate of A. fumigatus. It is possible that these effects may show variability when different strains of mice or of fungal pathogens are used.

The therapeutic effect of rSP-D observed in this study is consistent with the recently observed anti-Aspergillus activity of this truncated form of SP-D. rSP-D binds to A. fumigatus conidia in a calcium-, dose-, and carbohydrate-dependent manner and enhances the phagocytosis and killing of conidia by PMNs threefold when used at a concentration of 4.5 μg/ml (Madan et al., unpublished data). These in vitro results and the observations made in this study suggest that even a truncated form of SP-D lacking the collagen region is sufficient to participate in the clearance of A. fumigatus. Hickling et al. (8) have recently shown that rSP-D can inhibit respiratory syncytial virus infectivity in cell culture, giving 100% inhibition of replication. Intranasal administration of rSP-D to respiratory syncytial virus-infected mice appeared to inhibit viral replication in the lungs, reducing viral load to 80%. Several recent reports indicate that the CRD regions of SP-D may fulfill other functions, such as chemotaxis and binding to a putative receptor (gp340), besides binding carbohydrate (5, 9). It appears that rSP-D could potentially be used for the treatment of A. fumigatus infections in human patients as an adjunctive therapy.

Acknowledgments

The present work was in part funded by the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research, India (T. Madan and P. U. Sarma), the Medical Research Council, United Kingdom (K. B. M. Reid), the European Commission (ECEC-QLK-2000-00325) (U. Kishore and K. B. M. Reid), and the British Lung Foundation (K. B. M. Reid).

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen M J, Harbeck R, Smith B, Voelker D R, Mason R J. Binding of rat and human surfactant proteins A and D to Aspergillus fumigatus conidia. Infect Immun. 1999;67:4563–4569. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.9.4563-4569.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Allen S D, Sorensen K N, Nejdl M J, Durrant C, Profitt R T. Prophylactic efficacy of aerosolised liposomal (AmBiosoma) and non-liposomal (Fungizone) amphotericin B in murine pulmonary aspergillosis. J Antimicrob Chemother. 1994;34:1001–1013. doi: 10.1093/jac/34.6.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bardana E., Jr The clinical spectrum of aspergillosis. II. Classification and description of saprophyte, allergic, and invasive variants of human disease. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 1981;13:85–159. doi: 10.3109/10408368009106445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bodey G P, Vartivarian S. Aspergillosis. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1989;8:413–437. doi: 10.1007/BF01964057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cai G-J, Griffin G L, Senior R M, Longmore W J, Moxley M A. Recombinant SP-D carbohydrate recognition domain is a chemoattractant for human neutrophils. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:L131–L136. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.1.L131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chilvers E R, Spreadbury C L, Cohen J. Bronchoalveolar lavage in an immunosuppressed rabbit model of invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Mycopathology. 1989;108:163–171. doi: 10.1007/BF00436221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Denning D W, Stevens D A. Antifungal and surgical treatment of invasive aspergillosis. Rev Infect Dis. 1990;12:1147–1201. doi: 10.1093/clinids/12.6.1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hickling T P, Bright H, Wing K, Gower D, Martin S L, Sim R B, Malhotra R. A recombinant trimeric surfactant protein D carbohydrate recognition domain inhibits respiratory syncytial virus infection in vitro and in vivo. Eur J Immunol. 1999;29:3478–3484. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-4141(199911)29:11<3478::AID-IMMU3478>3.0.CO;2-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Holmskov U, Lawson P, Teisner B, Tornoe I, Willis A C, Morgan C, Koch C, Reid K B M. Isolation and characterization of a new member of scavenger receptor superfamily, glycoprotein-340 (gp-340) as a lung surfactant protein D binding molecule. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:13743–13749. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.21.13743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hoppe H J, Reid K B M. Collectins—soluble proteins containing collagenous regions and lectin domains—and their roles in innate immunity. Protein Sci. 1994;3:1143–1158. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560030801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishii Y, Wang Y, Haziot A, del Vecchio P J, Goyert S M, Malik A B. Lipopolysaccharide binding protein and CD14 interaction induces tumor necrosis factor-alpha generation and neutrophil sequestration in lungs after intratracheal endotoxin. Circ Res. 1993;73:15–23. doi: 10.1161/01.res.73.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kishore U, Wang J Y, Hoppe H J, Reid K B M. The α-helical neck region of human lung surfactant protein D is essential for the binding of the carbohydrate recognition domains to lipopolysaccharides and phospholipids. Biochem J. 1996;318:505–511. doi: 10.1042/bj3180505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Korfhagen T R, Bruno M D, Ross G F, Huelsman K M, Ikegami M, Jobe A H, Wert S E, Stripp B R, Morris R E, Glasser S W, Bachurski C J, Iwamoto H S, Whitsett J A. Altered surfactant function and structure in SP-A gene targeted mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:9594–9599. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.18.9594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Korfhagen T R, LeVine A M, Whitsett J A. Surfactant protein A (SP-A) gene targeted mice. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1408:296–302. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(98)00075-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LeVine A M, Kurak K E, Bruno M D, Stark J M, Whitsett J A, Korfhagen T R. Surfactant protein A-deficient mice are susceptible to Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1998;19:700–708. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.19.4.3254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levitz S M, Selsted M E, Ganz T, Lehrer R I, Diamond R D. In vitro killing of spores and hyphae of Aspergillus fumigatus and Rhizopus oryzae by rabbit neutrophil cationic peptides and bronchoalveolar macrophages. J Infect Dis. 1986;154:483–489. doi: 10.1093/infdis/154.3.483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Madan T, Eggleton P, Kishore U, Strong P, Aggarwal S S, Sarma P U, Reid K B M. Binding of pulmonary surfactant protein A and D to Aspergillus fumigatus conidia enhances phagocytosis and killing by human neutrophils and macrophages. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3171–3179. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.8.3171-3179.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maddux M S, Barriere S L. A review of complications of amphotericin B therapy: recommendations for prevention and management. Drug Intell Clin Pharm. 1980;14:177–189. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miyamura K, Malhotra R, Hoppe H J, Reid K B M, Phizackerley P J, Macpherson P, Lopez Bernal A. Surfactant proteins A (SP-A) and D (SP-D): levels in human amniotic fluid and localization in the fetal membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1210:303–307. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(94)90233-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Postle A D, Mander A, Reid K B M, Wang J Y, Wright S M, Moustaki M, Warner J O. Deficient hydrophilic lung surfactant proteins A and D with normal surfactant phospholipid molecular species in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;20:90–98. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.20.1.3253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reading P C, Morey L S, Crouch E C, Anders E M. Collection-mediated antiviral host defense of the lung: evidence from influenza virus infection of mice. J Virol. 1997;71:8204–8214. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8204-8212.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reid K B M. Interaction of surfactant protein D with pathogens, allergens and phagocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1408:290–295. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4439(98)00074-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rollides E, Holmes A, Blake C, Pizzo P A, Walsh T J. Defective antifungal activity of monocyte-derived macrophages from HIV-infected children against Aspergillus fumigatus. J Infect Dis. 1993;168:1562–1565. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.6.1562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rollides E, Holmes A, Blake C, Pizzo P A, Walsh T J. Impairment of neutrophil antifungal activity against hyphae of Aspergillus fumigatus in HIV-infected children. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:905–911. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.4.905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schaffner A, Douglas H, Braude A. Selective protection against conidia by mononuclear and against mycelia by polymorphonuclear phagocytes in resistance to Aspergillus: observations on these two lines of defence in vivo and in vitro with human and mouse phagocytes. J Clin Investig. 1982;69:617–631. doi: 10.1172/JCI110489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sternberg S. The emerging fungal threat. Science. 1994;266:1632–1634. doi: 10.1126/science.7702654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Strong P, Kishore U, Morgan C, Bernal A L, Singh M, Reid K B M. A novel method of purifying lung surfactant proteins A and D from the lung lavage of alveolar proteinosis patients and pooled amniotic fluid. J Immunol Methods. 1998;220:139–149. doi: 10.1016/s0022-1759(98)00160-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Waldorf A R, Levitz S M, Diamond R D. In vivo bronchoalveolar macrophage defense against Rhizopus oryzae and Aspergillus fumigatus. J Infect Dis. 1984;150:752–760. doi: 10.1093/infdis/150.5.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wright J R. Immunomodulatory functions of surfactant. Physiol Rev. 1997;77:931–962. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1997.77.4.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Young S L, Ho Y S, Silbajoris R A. Surfactant apoprotein in adult rat lung compartments is increased by dexamethasone. Am J Physiol. 1991;260:L161–L167. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1991.260.2.L161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]