Abstract

Erythrocytes express the Duffy antigen receptor for chemokines. Endotoxin injection into humans induced high levels of interleukin-8 (IL-8), growth-related oncogene α, and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 in circulating erythrocytes. IL-8 was also recovered from mononuclear and polymorphonuclear cells. Cell-associated chemokines may more accurately reflect their production than plasma concentrations.

Chemokines can be classified into several families which target either granulocytes (CXC chemokines) or mononuclear cells (CC chemokines) (1, 7). The Duffy antigen receptor for chemokines (DARC), present on the surface of erythrocytes, is a promiscuous chemokine receptor binding a number of CXC and CC chemokines (5, 10) and has been proposed to function as a sink receptor for chemokines present in the circulation (3). Indeed, erythrocyte-bound interleukin-8 (IL-8), the prototypic CXC chemokine, could be detected in humans after administration of IL-1 or IL-2 long after IL-8 had disappeared from plasma (13, 14). Furthermore, patients with sepsis demonstrated high levels of cell-associated IL-8 in their circulation (8, 9), which could be located not only in erythrocytes but also in mononuclear and polymorphonuclear cell fractions (8). Together these data suggest that besides DARC, surface receptors on leukocytes may contribute to the occurrence of cell-associated chemokines, and that measurement of cell-associated chemokines may provide more accurate information on the extent of chemokine production than plasma concentrations. Knowledge of the in vivo induction of cell-associated chemokines other than IL-8 is highly limited. Like IL-8, growth-related oncogene α (GRO-α), a CXC chemokine, and monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1), a CC chemokine, can bind to DARC (1, 7). In the present study, we sequentially measured the concentrations of IL-8, GRO-α, and MCP-1 in plasma and cell fractions isolated from peripheral blood of healthy humans intravenously injected with lipopolysaccharide (LPS). The induction of these chemokines was compared with the levels of macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP-1β), a CC chemokine that does not bind to DARC.

Eight healthy subjects (mean age ± standard error [SE], 24 ± 1 years) were studied after intravenous administration of LPS (lot G from Escherichia coli; U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention Inc., Rockville, Md.) at a dose of 4 ng/kg of body weight. Written informed consent was obtained from all study participants, and the study was approved by the ethics and research committees of the Academic Medical Center. Blood was collected before LPS administration and 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 24 h thereafter. EDTA plasma was obtained by centrifugation at 1,500 × g for 20 min. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), polymorphonuclear cells (PMNs), and red blood cells (RBCs) were isolated from blood drawn before and 2, 4, 6 and 24 h after LPS injection, as follows. Heparinized blood was layered on an equal volume of Polymorphprep (Nycomed Pharma AS, Oslo, Norway) and centrifuged at 500 × g for 30 mins at 20°C. The harvested PBMC, PMN, and RBC fractions were diluted 1:2 in 0.5 N RPMI 1640 (BioWhittaker, Verviers, Belgium) in order to restore normal osmolality and then spun at 400 × g for 10 min at 20°C. RBCs contaminating PBMC and PMN fractions were lysed using ice-cold isotonic NH4Cl solution (155 mM NH4Cl, 10 mM KHCO3, 0.1 mM EDTA [pH 7.4]) for 10 min. The cell fractions were spun again at 400 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and the pellet was resuspended in 1 N RPMI 1640 containing 5% normal human serum (BioWhittaker) to the original blood volume. Purity of the cell fractions was checked using a 0.1% eosin stain and was found to be above 99%. All three cell fractions were spun at 400 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Next, RBCs were lysed using 30 ml of ice-cold isotonic NH4Cl solution (as described above); PBMC and PMN fractions were lysed by a 15-min incubation with ice-cold lysis buffer containing 300 mM NaCl, 30 mM Tris, 2 mM MgCl2, 2 mM CaCl2, 1% Triton X-100, and pepstatin A, leupeptin, and aprotinin (all 20 ng/ml; pH 7.4). Lysed fractions were resuspended in 1 N RPMI 1640. Leukocyte counts and differentials were assessed by a Stekker analyzer (counter STKS; Coulter Counter, Bedfordshire, United Kingdom). Chemokine concentrations were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) according to the instructions of the manufacturers (for IL-8, Central Laboratory of The Netherlands Red Cross Blood Transfusion Service, Amsterdam, The Netherlands; for GRO-α and MIP-1β, R&D Systems, Abingdon, United Kingdom; for MCP-1, PharMingen, San Diego, Calif.). Detection limits were 1.7 pg/ml (IL-8), 14.3 pg/ml (GRO-α), 1.1 pg/ml (MCP-1), and 15.6 pg/ml (MIP-1β). In separate experiments we determined that neither of the lysis buffers influenced the ELISA results (data not shown). Values are given as mean ± SE. Changes of parameters in time were tested using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Dunnet's post hoc test. Two-sample comparisons were done by paired Student's t test. α for all tests was set at 0.05.

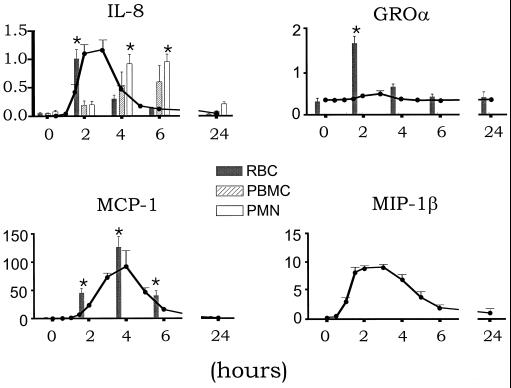

LPS administration induced profound changes in peripheral blood cell fractions. Table 1 lists blood cell counts at the time points cell fractions were isolated for chemokine measurements. Intravenous injection of LPS was associated with transient increases in the plasma concentrations of all four chemokines measured, peaking after 3 h (IL-8, 1.17 ± 0.17 ng/ml; GRO-α, 0.36 ± 0.04 ng/ml; MIP-1β, 9.18 ± 0.48 ng/ml) or 4 h (MCP-1, 92.07 ± 28.11 ng/ml) (all P < 0.05) (Fig. 1). LPS further induced a transient increase in IL-8 associated with RBCs, PBMCs, and PMNs (Fig. 1 and Table 2). At 2 h after LPS injection, IL-8 mainly was recovered from RBCs. At 4 and 6 h after LPS administration, when plasma IL-8 concentrations were rapidly decreasing, IL-8 predominantly was associated with PMNs. PBMC- and PMN-associated IL-8 both peaked at 6 h after LPS treatment, at which time point the cell-associated IL-8 concentrations were significantly higher than plasma IL-8 levels (PBMC, 0.59 ± 0.29, PMN, 0.94 ± 0.14; plasma, 0.12 ± 0.03 ng/ml; P < 0.005 for the difference between PBMC or PMN and plasma). In contrast, GRO-α and MCP-1 virtually exclusively circulated in association with RBCs. Indeed, RBC-associated GRO-α peaked at 2 h (1.62 ± 0.16 ng/ml), at which time point plasma GRO-α levels were 0.33 ± 0.03 ng/ml (P < 0.001 versus RBC). The appearance of RBC-associated MCP-1 in the circulation followed similar kinetics as the release of MCP-1 in plasma, although RBC MCP-1 tended to be higher than plasma MCP-1 at 2, 4, and 6 h after LPS administration. RBC MCP-1 peaked after 4 h (127.47 ± 19.69 ng/ml). GRO-α and MCP-1 remained low and unchanged in PBMC and PMN fractions (virtually all measured values in cell lysates were below the detection limit of the assays, i.e., <0.28 ng/ml for GRO-α and <0.02 ng/ml for MCP-1). MIP-1β, which was measured as a non-DARC binding chemokine, remained very low or undetectable in all cell fractions after LPS administration.

TABLE 1.

Cell fractions in peripheral blood before and after LPS injectiona

| Time (h) | RBCs (1012/liter) | Leukocytes (109/liter) | PMNs (109/liter) | Monocytes (109/liter) | Lymphocytes (109/liter) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 5.6 ± 0.7 | 3.5 ± 0.2 | 0.5 ± 0.03 | 1.7 ± 0.2 |

| 2 | 6.2 ± 0.5 | 5.9 ± 0.7 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 0.1 ± 0.02∗ | 0.9 ± 0.2∗ |

| 4 | 4.7 ± 0.6 | 7.9 ± 0.7∗ | 7.5 ± 0.2∗ | 0.1 ± 0.02∗ | 0.3 ± 0.02∗ |

| 6 | 5.6 ± 0.7 | 11.4 ± 0.9∗ | 10.7 ± 0.1∗ | 0.3 ± 0.02∗ | 0.5 ± 0.1∗ |

| 24 | 5.3 ± 0.4 | 8.0 ± 0.8∗ | 5.6 ± 0.2 | 0.6 ± 0.1 | 1.8 ± 0.2 |

| P | NS | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Data are means ± SE for eight healthy subjects injected intravenously with LPS at time zero. P values reflect significance for changes in time (ANOVA). Asterisks indicate P < 0.05 versus time zero by Dunnet's post hoc test. NS, nonsignificant.

FIG. 1.

Mean ± SE plasma- and blood cell-associated IL-8, GRO-α, MCP-1, and MIP-1β in healthy subjects after administration of endotoxin. RBC (grey bars)-, PBMC (hatched bars)-, and PMN (white bars)-associated chemokines are plotted against their plasma concentrations (continuous line). All concentrations are given in nanograms per milliliter; cell-associated chemokines were measured in lysates of cells that were resuspended to the original blood volume in RPMI 1640 after their isolation from peripheral blood. Plasma concentrations were measured prior to endotoxin injection (time zero) and during a follow-up of 24 h. Chemokines associated with blood cells were measured in cell lysates isolated prior to endotoxin injection and 2, 4, 6, and 24 h thereafter. Asterisks indicate significant difference from time zero. For reasons of clarity, significance for concentrations in plasma at individual time points is not presented. Plasma levels of all four chemokines increased significantly (IL-8, MCP-1, and MIP-1β, P < 0.001; GRO-α, P < 0.05). No MIP-1β was recovered from cell fractions.

TABLE 2.

Chemokine concentrations in blood cell fractionsa

| Time (h) | Concn (pg/106cells)

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-8 in:

|

GRO-α in RBCs | MCP-1 in RBCs | |||

| RBCs | PBMCs | PMNs | |||

| 0 | 0.02 ± 0.01 | 14.09 ± 4.19 | 15.72 ± 5.68 | 0.06 ± 0.00 | 0.46 ± 0.12 |

| 2 | 0.31 ± 0.07∗ | 193.51 ± 73.27∗ | 40.54 ± 10.96 | 0.23 ± 0.20 | 13.47 ± 3.23∗ |

| 4 | 0.18 ± 0.10∗ | 1,076.15 ± 483.28∗ | 121.35 ± 22.42∗ | 0.17 ± 0.10 | 84.93 ± 48.49∗ |

| 6 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 872.74 ± 371.27∗ | 89.71 ± 14.93∗ | 0.07 ± 0.10 | 15.81 ± 4.32∗ |

| 24 | 0.01 ± 0.00 | 29.57 ± 7.15 | 34.51 ± 3.91 | 0.07 ± 0.10 | 0.36 ± 0.05 |

| P | <0.005 | <0.001 | <0.005 | NS | <0.001 |

Data are means ± SE for eight healthy subjects injected intravenously with LPS at time zero. P values reflect significance for changes in time (ANOVA). Asterisks indicate P < 0.05 versus time zero by Dunnet's post hoc test. NS, nonsignificant.

Endotoxemia and gram-negative sepsis are characterized by elevated levels of chemokines in plasma (2, 4, 8, 9, 11, 12). Marie et al. found that in patients with sepsis, IL-8 bound to blood cells exceeds IL-8 concentrations in plasma (8). RBC-bound IL-8 was also found in patients who underwent cardiopulmonary bypass (6), as well as in patients treated with IL-1 and IL-2 (13, 14). We extend these findings by reporting the extent to which other chemokines present in the circulation are associated with different blood cells in the course of experimental endotoxemia. Our study design allowed us to study the kinetics of the appearance of IL-8 in plasma and in RBC, PMN, and PBMC fractions. Interestingly, RBC - associated IL-8 peaked early and transiently, after 2 h, while PMN- and PBMC-associated IL-8 reached a plateau after 4 to 6 h. We consider it unlikely that RBCs contaminating PMN and PBMC fractions contributed to a significant extent to IL-8 concentrations recovered from PMN and PBMC lysates, since very few RBCs contaminated leukocytes after separation by Polymorphprep and since MCP-1 could not be recovered in significant concentrations from PMN and PBMC fractions, whereas MCP-1 concentrations in the RBC fraction were more than 100-fold higher than RBC-associated IL-8 levels. Our study does not elucidate the mechanism by which IL-8 appears in the PMN and PBMC fractions. Patients with sepsis had IL-8 mRNA in circulating leukocytes (4), and in preliminary investigations we found IL-8 mRNA expression in PMNs after LPS injection, suggesting that at least some of the IL-8 recovered from PMNs is produced by these cells. Alternatively, IL-8 produced elsewhere could bind to IL-8 receptors present on PMNs and PBMCs, a possibility supported by the finding that recombinant IL-8 added to human whole blood rapidly associated with RBCs, PMNs, and PBMCs (8). If this would occur in vivo, the possibility that IL-8 bound by DARC on RBCs can be transferred to PMNs and/or PBMCs warrants further investigation. Our study further shows that during an inflammatory response besides IL-8, also GRO-α and MCP-1, like IL-8 DARC binding chemokines, circulate in association with RBCs to a significant extent.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the Dutch Kidney Foundation to D. P. Olszyna and from the Royal Dutch Academy of Arts and Sciences to T. van der Poll.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams D H, Lloyd A R. Chemokines: leucocyte recruitment and activation cytokines. Lancet. 1997;349:490–495. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)07524-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bossink A W, Paemen L, Jansen P M, Hack C E, Thijs L G, Van Damme J. Plasma levels of the chemokines monocyte chemotactic proteins-1 and -2 are elevated in human sepsis. Blood. 1995;86:3841–3847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Darbonne W C, Rice G C, Mohler M A, Apple T, Hebert C A, Valente A J, Baker J B. Red blood cells are a sink for interleukin 8, a leukocyte chemotaxin. J Clin Investig. 1991;88:1362–1369. doi: 10.1172/JCI115442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Friedland J S, Suputtamongkol Y, Remick D G, Chaowagul W, Strieter R M, Kunkel S L, White N J, Griffin G E. Prolonged elevation of interleukin-8 and interleukin-6 concentrations in plasma and of interleukin-8 mRNA levels during septicemic and localized Pseudomonas pseudomallei infection. Infect Immun. 1992;60:2402–2408. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.6.2402-2408.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Horuk R, Chitnis C E, Darbonne W C, Colby T J, Rybicki A, Hadley T J, Miller L H. A receptor for the malarial parasite Plasmodium vivax: the erythrocyte chemokine receptor. Science. 1993;261:1182–1184. doi: 10.1126/science.7689250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalfin R E, Engelman R M, Rousou J A, Flack III J E, Deaton D W, Kreutzer D L, Das D K. Induction of interleukin-8 expression during cardiopulmonary bypass. Circulation. 1993;88:11401–11406. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luster A D. Chemokines—chemotactic cytokines that mediate inflammation. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:436–445. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802123380706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marie C, Fitting C, Cheval C, Losser M R, Carlet J, Payen D, Foster K, Cavaillon J M. Presence of high levels of leukocyte-associated interleukin-8 upon cell activation and in patients with sepsis syndrome. Infect Immun. 1997;65:865–871. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.3.865-871.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marie C, Muret J, Fitting C, Losser M R, Payen D, Cavaillon J M. Reduced ex vivo interleukin-8 production by neutrophils in septic and nonseptic systemic inflammatory response syndrome. Blood. 1998;91:3439–3446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neote K, Darbonne W, Ogez J, Horuk R, Schall T J. Identification of a promiscuous inflammatory peptide receptor on the surface of red blood cells. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:12247–12249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olszyna D P, Prins J M, Dekkers P E, De Jonge E, Speelman P, Van Deventer S J, Van Der Poll T. Sequential measurements of chemokines in urosepsis and experimental endotoxemia. J Clin Immunol. 1999;19:399–405. doi: 10.1023/a:1020554817047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olszyna D P, Opal S M, Prins J M, Horn D L, Speelman P, van Deventer S J H, van der Poll T. Chemotactic activity of CXC chemokines interleukin (IL)-8, growth-related oncogene (GRO)a and epithelial cell-derived neutrophil-activating protein (ENA)-78 in urine of patients with urosepsis. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1731–1737. doi: 10.1086/317603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Olszyna D P, Prins J M, Dekkers P E, De Jonge E, Speelman P, van Deventer S J, van der Poll T. Sequential measurements of chemokines in urosepsis and experimental endotoxemia. J Clin Immunol. 1999;19:399–405. doi: 10.1023/a:1020554817047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olszyna D P, Opal S M, Prins J M, Horn D L, Speelman P, van Deventer S J H, van der Poll T. Chemotactic activity of CXC chemokines interleukin-8, growth-related oncogene-α and epithelial cell-derived neutrophil-activating protein-78 in urine of patients with urosepsis. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1731–1737. doi: 10.1086/317603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tilg H, Pape D, Trehu E, Shapiro L, Atkins M B, Dinarello C A, Mier J W. A method for the detection of erythrocyte-bound interleukin-8 in humans during interleukin-1 immunotherapy. J Immunol Methods. 1993;163:253–258. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(93)90129-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tilg H, Shapiro L, Atkins M B, Dinarello C A, Mier J W. Induction of circulating and erythrocyte-bound IL-8 by IL-2 immunotherapy and suppression of its in vitro production by IL-1 receptor antagonist and soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor (p75) chimera. J Immunol. 1993;151:3299–3307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]