Abstract

Cell therapies and regenerative medicine interventions require an adequate source of therapeutic cells. Here, we demonstrate that constructing in vivo osteo-organoids by implanting bone morphogenetic protein–2–loaded scaffolds into the internal muscle pocket near the femur of mice supports the growth and subsequent harvest of therapeutically useful cells including hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs), mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), lymphocytes, and myeloid cells. Profiling of the in vivo osteo-organoid maturation process delineated three stages—fibroproliferation, osteochondral differentiation, and marrow generation—each of which entailed obvious changes in the organoid structure and cell type distribution. The MSCs harvested from the osteochondral differentiation stage mitigated carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)–induced chronic liver fibrosis in mice, while HSPCs and immune cells harvested during the marrow generation stage rapidly and effectively reconstituted the impaired peripheral and solid immune organs of irradiated mice. These findings demonstrate the therapeutic potentials of in vivo osteo-organoid–derived cells in cell therapies.

A BMP-2-triggered in vivo osteo-organoid possesses specific cellular components at different developmental stages.

INTRODUCTION

Cell therapy has achieved marked advances in addressing tumors, hematopoietic system injury, solid organ injury, and autoimmune diseases, but it is still limited to the insufficient supply of therapeutic cells, such as hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs), mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), and immune cells (1–4). Considering the high risk and low efficiency in directed differentiation from human pluripotent stem cells or the direct conversion from somatic cells, expanding stem cells and immune cells in vitro currently remains the mainstream approach (5–8). Large-scale in vitro cell expansion is still a time-consuming and expensive method for harvesting therapeutic cells and typically produces only one type of therapeutic cells (3, 4, 9, 10). Harvesting therapeutic cells that contain stem cells and mature immune cells may provide a consistent therapeutic effect and could be a beneficial complement for the current cell therapy methods.Activating the residual regenerative capacity of adult mammals to harvest therapeutic cells in vivo via bioactive materials become a promising strategy (11, 12).

Recent studies have reported multiple types of methods to induce ectopic bone by biomaterial-triggered endochondral ossification (11–15), which we call in vivo osteo-organoid because it undergoes a developmental process in vivo. The in vivo osteo-organoid has been applied to elucidate the mechanism of hematopoiesis and bone metastatic processes (16–23). It can also be used as a source of bone graft. A recent case report confirmed the clinical translation capacity of in vivo osteo-organoid strategy in addressing large maxillary defect (24). We have previously confirmed that the bone morphogenetic protein–2 (BMP-2)–loaded scaffold–induced in vivo osteo-organoid at different developmental stages could serve as a robust osteogenic tissue for critical bone defect repair (25, 26). This in vivo osteo-organoid also exhibited a more juvenile phenotype than the native bone marrow (BM) in old mice and harbored large amounts of cells, such as MSCs and immune cells (26). However, the therapeutic potentials and cell composition characteristics of the cells from the in vivo osteo-organoid induced by a BMP-2–loaded scaffold at different developmental stages remain little understood and need further clarification.

Here, we demonstrate a cell-free strategy to consistently harvest abundant and high-quality autologous cells by constructing an in vivo osteo-organoid using a BMP-2–loaded gelatin scaffold. This in vivo osteo-organoid serves as an adaptive niche for the successive aggregation of stem cells and immune cells, which develops during three successive stages: fibroproliferation, osteochondral differentiation, and marrow generation. We therapeutically applied osteochondral-stage cells from the in vivo osteo-organoid to successfully treat hepatic injuries, and an irradiation damage repair assay demonstrated that marrow generation–stage cells can rapidly and stably reconstitute the experimentally impaired immune system. Assessment of the osteo-organoids using high-parameter flow cytometry and profiling with a high-throughput protein array supported the detailed developmental characterization of cells and cytokines during the three stages. This high-resolution data can support further customization and modification of cells from the implanted in vivo osteo-organoids, for example, with specific bioactive factors to meet the specific demands of diverse cell therapy applications.

RESULTS

In vivo biomimetic development of osteo-organoid

Our goal in the present study was to explore an in vivo strategy for harvesting high-quality autologous cells for cell therapy applications. Inspired by some observations made during our previous work with BMP-2–loaded gelatin scaffolds to harvest osteogenic tissues for the repair of critical bone defects, we speculated that the cells generated during the development of the osteo-organoid from the implanted scaffold likely have distinct properties and thus therapeutic capacities at different developmental stages. Pursuing this, we implanted 24 of low (10 μg)–, intermediate (30 μg)–, or high (50 μg)–dosage BMP-2–loaded gelatin scaffolds into the internal muscle pocket near the femur of mice, respectively (fig. S1A).

Initial profiling using dual-energy x-ray imaging confirmed that successful development of osteo-organoid did not alter the overall bone mineral density (BMD) or native femur BMD of the scaffold-recipient mice, regardless of the BMP-2 concentration used (fig. S1, A to C). Obvious bone generation was evident within 2 weeks of the implantation; no newly formed bone was detected for the phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) control group (fig. S1A). The BMD values stabilized in the 30- and 50-μg groups by 3 weeks after the implantation (fig. S1D), and the BMD value was highest for the mice that received the high-dosage BMP-2 scaffold (fig. S1D). The eventually diminishing BMD values detected for the 10-μg group suggested that the 10-μg BMP-2 dose was insufficient to sustain osteo-organoid development (fig. S1D). Consistent with the in vivo x-ray data, macroscopic imaging and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining of osteo-organoids excised at weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, and 12 after implantation showed BMP-2 dosage–dependent bone volume and development (fig. S1, E and F). We choose 30-μg BMP-2 as the suitable dosage for the following experiments by comprehensively considering the volume and BMD of osteo-organoid, as well as the cost for constructing an osteo-organoid.

Blood analyses detected no differences in the number of white blood cells (WBCs) or red blood cells (RBCs) among any of the groups (fig. S2, A to C). We did detect an increase in the platelet number in the BMP-treated group on postimplantation days 7 and 14, but this increase was no longer evident by day 28 (fig. S2D). Moreover, blood serum analyses detected no differences in the levels of chemokines, inflammatory factors, or cytokines among any of the groups (fig. S2E). We also measured the concentration of the same factors in the native BM and found no difference between the nontreated group and the BMP-treated groups (fig. S2F). These results support that the implantation of the BMP-2–loaded scaffold and the subsequent in vivo development of the osteo-organoid are apparently safe and do not alter hematopoietic homeostasis in the host.

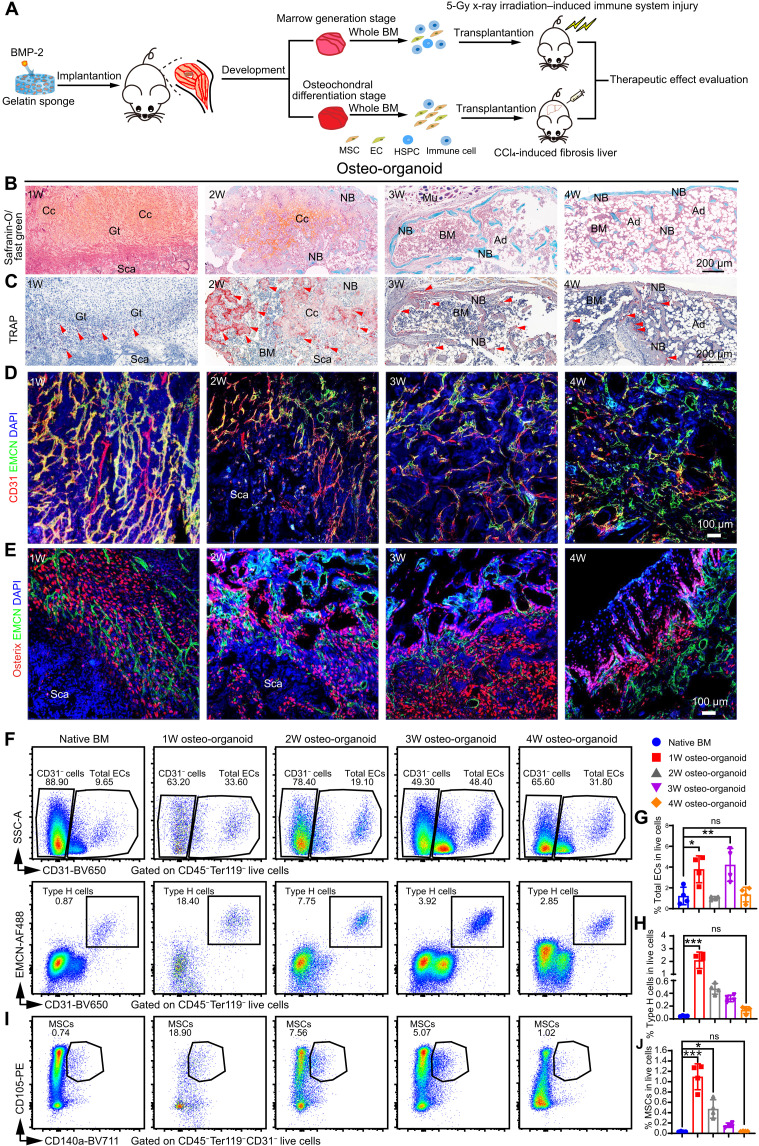

We next used histology techniques and flow cytometry to profile a time series of in vivo osteo-organoid development (Fig. 1A). Briefly, our safranin-O/fast green staining and tartrate-resistant acid phosphatase (TRAP) staining (Fig. 1, B and C) showed a successive, three-stage maturation sequence for the osteo-organoids: commencing with fibroproliferation (implantation through about week 1), followed by osteochondral differentiation (about weeks 1 to 2), and later marrow generation (from about week 2). In detail, the implanted scaffold was initially surrounded by a thick fibrous tissue characterized by the presence of macrophage-lineage TRAP+ mononuclear cells at the junction between the scaffold and the fibrous tissue, a few immature chondrocytes, as well as abundant Osterix+ osteoprogenitor cells and type H blood vessels [positive for CD31 and endomucin (EMCN)] (Fig. 1, D and E). Type H vessels have been reported to couple angiogenesis to osteogenesis in bone (27). During the subsequent osteochondral differentiation stage, the recruited Osterix+ osteoprogenitors underwent endochondral differentiation coupled with type H vessels (Fig. 1, D and E). Meanwhile, osteoclast–triggered bone resorption became extremely active at this stage, which benefitted the marrow generation in osteo-organoid (Fig. 1, D and E). By the marrow generation stage, the osteo-organoid marrow cavity gradually enlarged with the aid of osteoclasts, and many cells aggregated into the osteo-organoid marrow. The osteo-organoid became mature, which exhibited as the balance of osteogenic and bone resorption activities, as well as the steady proportions of endothelial cells (ECs) and MSCs, since week 3 after implantation.

Fig. 1. The maturation of in vivo osteo-organoid subsequently undergoes the fibroproliferation, osteochondral differentiation, and marrow generation stages.

(A) Experimental scheme. BMP-2–loaded gelatin sponges (30 μg) were implanted into the internal muscle pocket near the femur of mice to generate the osteo-organoids. EC, endothelial cell. (B and C) Safranin-O–stained (B) and TRAP-stained (C) sections of osteo-organoids at the indicated time points. 1W, 1-week. (D and E) Immunofluorescence staining of type H blood vessels (EMCN+CD31+, yellow) (D) and Osterix+ osteogenic precursor cells (red) (E) in osteo-organoid at the indicated time points. CD31-positive cells and Osterix-positive cells are shown in red, EMCN-positive cells are shown in green, and 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) is shown in blue (nucleus). Granulation tissue (Gt), scaffolds (Sca), chondrocytes (Cc), muscle (Mu), BM, new bone (NB), and adipocytes (Ad) are shown. Red arrowheads indicate TRAP+ cells (C). Scale bars, 200 μm. n = 4 biological replicates. (F to J) Representative flow cytometry profiles (F and I) and quantitative analysis (G, H, and J) of total EC (CD45−Ter119−CD31+), type H blood cell (CD45−Ter119−CD31hiEMCNhi) subsets, and MSCs (CD45−Ter119−CD31−CD140a+CD105+) in the native BM and the osteo-organoid at weeks 1, 2, 3, and 4 after implantation. n = 4 biological replicates. Data are presented as means ± SD. Statistical differences among groups were identified by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001; ns denotes no significant difference. PE, phycoerythrin. "SSC-A" stands for "side scatter-area".

Consistent with the histological data, the flow cytometric data of total ECs (CD45−Ter119−CD31+), type H (CD45−Ter119−CD31hiEMCNhi) cells, and mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs; CD45−Ter119−CD31−CD140a+CD105+) in the osteo-organoid also varied greatly at different developmental stages. Specifically, the proportion of total ECs (3.790 ± 1.295), type H cells (2.095 ± 0.643), and MSCs (1.095 ± 0.251) in the 1-week osteo-organoid group increased 3.11-, 46.30-, and 32.44-fold compared to that in the native BM (1.220 ± 0.841, 0.045 ± 0.007, 0.034 ± 0.007, respectively) (Fig. 1, F to J, and fig. S3). With the maturation of osteo-organoid, the cell number in the 2-week osteo-organoid group increased, and the proportion of type H cells (0.470 ± 0.083) and MSCs (0.473 ± 0.178) in the 2-week osteo-organoid group still increased 10.39- and 14.00-fold compared to that in the native BM (Fig. 1, F to J). The proportion of blood vessels and MSCs in the osteo-organoid gradually decreased to the native BM level at the latter developmental stages (Fig. 1, F to J). Together, the BMP-2–loaded scaffold–triggered in vivo osteo-organoid underwent three typical developmental stages and became mature since week 3 after implantation.

Production of HSPCs by the in vivo osteo-organoids

HSPCs are widely used in treatments for hematopoietic injury, but they are still limited to their rare number in the native BM (9). We profiled the proliferation dynamics of HSPCs in the osteo-organoids by quantifying the number (fig. S4) and cell cycle (fig. S6A) of total cells and HSPCs at different developmental stages. Consistent with the previously observed development of the osteo-organoids, the number of total osteo-organoid cells increased rapidly during the fibroproliferation and osteochondral differentiation stages and subsequently remained stable at the marrow generation stage since week 3 after implantation (Fig. 2, A and B). To further evaluate the capacity of osteo-organoid for long-term production of therapeutic cells, we quantified the cell number in the osteo-organoid at week 12 after implantation and found that the total cell number in the 12-week osteo-organoids remained stable and was still 1.97-fold higher than that in the native BM (Fig. 2B and fig. S5). Moreover, to evaluate the cell cycle status of live cells in the osteo-organoid since the marrow generation stage, we conducted flow cytometry incorporated with Hoechst33342 staining. The proportions of live cells at the S + G2-M phase in the 3-week and 4-week osteo-organoid were much lower than that in the native BM, whereas the proportion in the 12-week osteo-organoid increased to the native BM level (17.30 ± 1.94 versus 16.78 ± 0.71; fig. S6B).

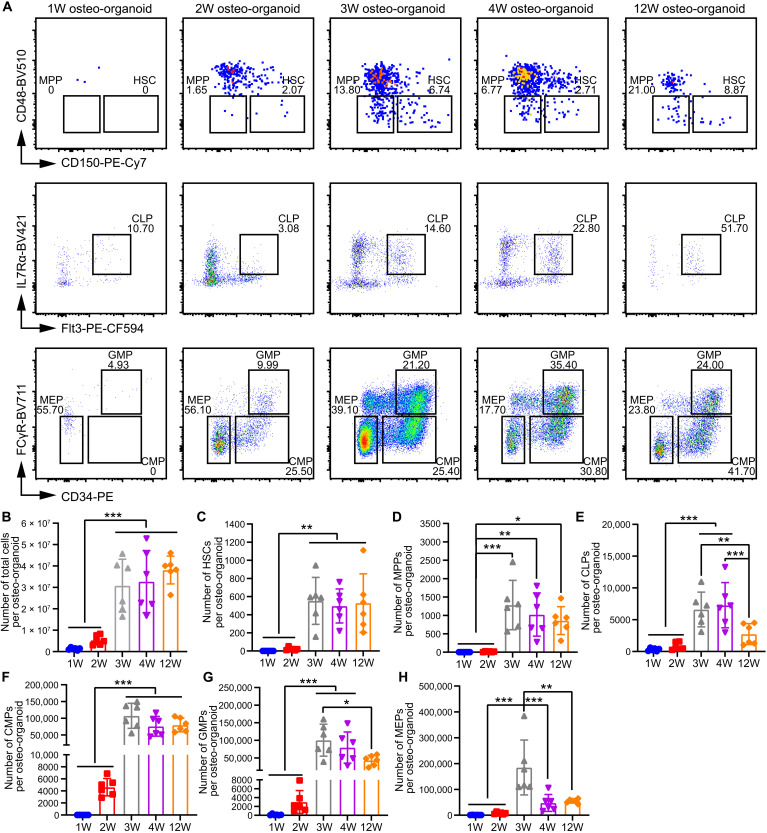

Fig. 2. The number of HSPCs in osteo-organoid becomes stable starting from the marrow generation stage.

(A) Representative flow cytometric plots of HSPCs in the native BM and the osteo-organoid at weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, and 12 after implantation. (B to H) Absolute numbers of total cells (B), HSCs (Lin−c-kit+Sca-1+CD48−CD150+) (C), MPPs (Lin−c-kit+Sca-1+CD48−CD150−) (D), CLPs (Lin−c-kitlowSca-1lowFlt3+IL7Rα+) (E), CMPs (Lin−c-kit+Sca-1−CD34+FCγR−) (F), GMPs (Lin−c-kit+Sca-1−CD34+FCγR+) (G), and MEPs (Lin−c-kit+Sca-1−CD34−FCγR−) (H) in the osteo-organoid at weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, and 12 after implantation and in the native BM. n = 6 biological replicates. Data are presented as means ± SD. Statistical differences among groups were identified by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs; Lin−c-kit+Sca- 1+CD48−CD150+) could differentiate into subsequent hematopoietic progenitors: multipotent progenitors (MPPs; Lin−c-kit+Sca-1+CD48−CD150−), common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs; Lin−c-kitlowSca-1lowFlt3+IL7Rα+), common myeloid progenitors (CMPs; Lin−c-kit+Sca-1−CD34+FCγR−), granulocyte-monocyte progenitors (GMPs; Lin−c-kit+Sca-1−CD34+FCγR+), and megakaryocyte-erythroid progenitors (MEPs; Lin−c-kit+Sca-1−CD34−FCγR−). We found that all types of HSPC subsets existed in the osteo-organoid, and the number of HSPCs in the osteo-organoid stayed at a relatively low level during the fibroproliferation and osteochondral differentiation stages, before increasing markedly during the marrow generation stage by the third week. This trend in HSPC development can be interpreted to reflect the maturation of the marrow region of the osteo-organoid (Fig. 2, C to H). Specifically, starting from week 3 after implantation, the number of HSCs was around 500, while the number of MPPs was around 1000 (Fig. 2, C and D). The number of CLPs, CMPs, GMPs, and MEPs in the osteo-organoid at week 12 after implantation was around 2750, 80,000, 43,000, and 55,000, respectively (Fig. 2, E to H). Together, these results support that the osteo-organoids can consistently produce HSPCs for cell therapy.

For HSPC subsets in the osteo-organoids, we also conducted cell cycle analysis from the marrow generation stage (fig. S6A). We found that the proportions of LKS− cells (Lin−c-kit+Sca-1−) at the S + G2-M phase in the 3-week and 4-week osteo-organoid were much lower than that in the native BM (26.53 ± 0.66 and 22.70 ± 2.23 versus 30.85 ± 1.19; fig. S6C), whereas the proportions of LKS+ cells (Lin−c-kit+Sca-1+) at the S + G2-M phase in the 3-week and 4-week osteo-organoid were much higher than that in the native BM (24.30 ± 2.326 and 25.47 ± 5.04 versus 17.25 ± 0.83; fig. S6D). The proportions of LKS− and LKS+ cells at the S + G2-M phase in the 12-week osteo-organoid were much higher than that in the native BM (fig. S6, C and D). We further found that the proportions of MPPs and HSCs at the S + G2-M phase in the osteo-organoid were similar to those in the native BM, except the proportion of MPPs at the S + G2-M phase in the 4-week osteo-organoid and the proportion of HSCs at the S + G2-M phase in the 12-week osteo-organoid (fig. S6, E and F). Together, the cell cycle status of cells in the osteo-organoid was similar to that in the native BM in which the proportions of HSCs and MPPs at the S + G2-M phase were much lower than the proportions of subsequent HSPCs at the S + G2-M phase, such as LKS− and LKS+ cells.

Composition of immune cells in the osteo-organoid at different developmental stages

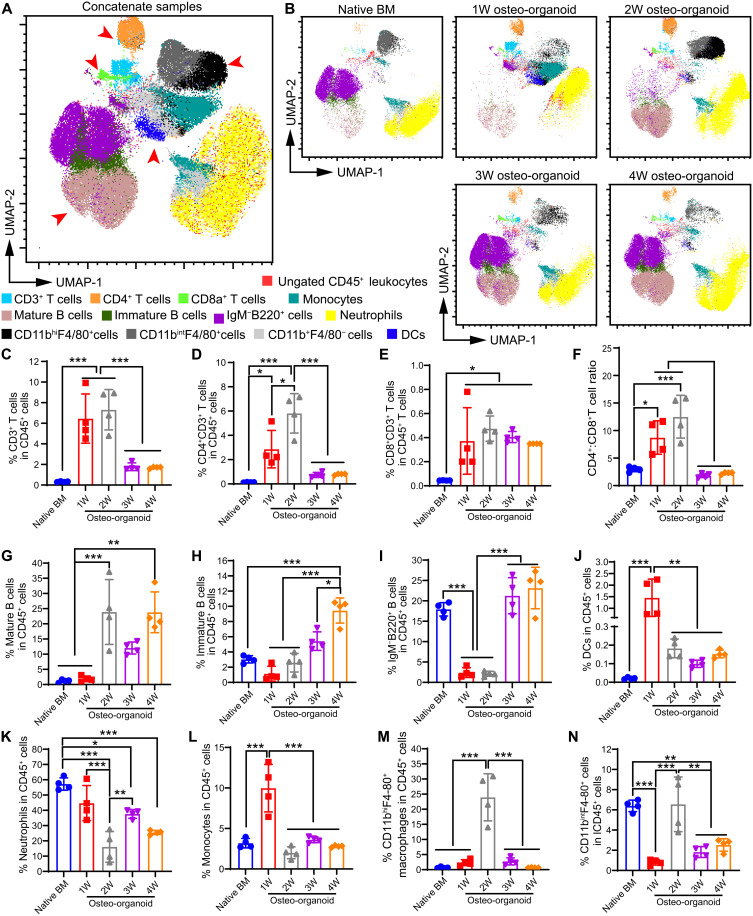

Immune cells are essential in preventing infection, hypoimmunity, and hematopoietic disease (28, 29). Whole-BM transplantation could rapidly reconstitute the immune system of irradiated recipients, which requires the BM to harbor HSPCs and multiple types of immune cells (30, 31). Similar to our analysis of HSPCs in the in vivo osteo-organoids, we used flow cytometry to quantify the compositions of immune cells in osteo-organoids at different developmental stages and in native BM (fig. S7). A uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) plot of concatenated samples showed major clusters including CD3+ T, B220+ B, and CD11b+ myeloid cells (Fig. 3A). The UMAP plots of the osteo-organoid group exhibited distinct immune cell composition relative to the native BM group at different developmental stages, such as the proportions of CD3+ T cells, mature B cells (CD45+CD3−B220hi), and dendritic cells (DCs; CD45+CD3−B220−IgM−CD11b+Ly6C−Ly6G−F4/80−MHC-II+CD11c+) (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3. Osteo-organoid exhibits distinct immune cell composition at different developmental stages.

(A and B) Flow cytometric analysis of cells isolated from the native BM and the osteo-organoid at weeks 1, 2, 3, and 4 after implantation. The CD45+ populations were then clustered via UMAP for visualization. UMAP plots of concatenate samples (A) and separate samples (B) from all five groups are presented. (C to N) Flow cytometric proportions of CD3+ T cells (C), CD4+CD3+ helper T cells (D), CD4+CD3+ effector T cells (E), CD4+:CD8+ T cell (F), mature B cells (CD45+CD3−B220hi) (G), immature B cells (CD45+CD3−IgM+B220+) (H), IgM+B220+ B cells (I), DCs (CD45+CD3−B220hiIgM−CD11b+Ly6C−Ly6G−F4/80−MHC-II+CD11c+) (J), neutrophils (CD45+CD3−IgM−B220−CD11b+Ly6G+Ly6Cint) (K), monocytes (CD45+CD3−IgM−B220−CD11b+Ly6G−Ly6C+) (L), CD11bhiF4/80+ macrophages (M), and CD11bintF4/80+ myeloid cells (N) from the osteo-organoid at weeks 1, 2, 3, and 4 after implantation and the native BM. n = 4 biological replicates. Data are presented as means ± SD. Statistical differences among groups were identified by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

In detail, we detected that the osteo-organoid at the fibroproliferation and osteochondral differentiation stages had an obviously elevated proportion of CD3+ T cells, CD4+CD3+ helper T cell subsets, and CD4+CD3+ effector T cell subsets compared to that in the native BM (Fig. 3, C to E). The CD4+:CD8+ T cell ratio usually reflects the degree of immunosuppression status (32). We found that the CD4+:CD8+ T cell ratio was significantly higher than that in the native BM, which confirmed that a highly immunosuppressive microenvironment was created during the fibroproliferation and osteochondral differentiation stages (Fig. 3F). This immunosuppressive microenvironment was no longer evident at the marrow generation stage starting from postimplantation week 3 (Fig. 3F).

The proportion of B cell subsets, including mature B cells, immature B cells (CD45+CD3−IgM+B220int), and IgM−B220int B cells, markedly increased during the development of osteo-organoid and was stabilized at the marrow generation stage (Fig. 3, G to I). The proportion of DCs in the osteo-organoid markedly increased at the fibroproliferation stage and was stabilized at the subsequent developmental stages (Fig. 3J). The proportion of neutrophils (CD45+CD3−IgM−B220−CD11b+Ly6G+Ly6Cint) in the osteo-organoid gradually decreased since the fibroproliferation stage and was stabilized at the marrow generation stages (Fig. 3K). The proportion of monocytes (CD45+CD3−IgM−B220−CD11b+Ly6G−Ly6C+) in the osteo-organoids was highest at the fibroproliferation stage, whereas the proportion of CD11bhiF4/80+ macrophages and CD11bintF4/80+ myeloid cells in the osteo-organoids was highest at the osteochondral differentiation stage, respectively (Fig. 3, L to N). The proportion of all these myeloid cells was stabilized at the marrow generation stages (Fig. 3, L to N). Consistent with the trend of neutrophils in the osteo-organoid, the proportion of Ter119+ erythrocytes decreased since the fibroproliferation stage and was stabilized at the marrow generation stages (fig. S8). Moreover, the extremely high proportions of Ter119+ erythrocytes, as well as abundant blood vessels, in the fibroproliferation stage accelerated the maturation of osteo-organoid. Together, the flow cytometry data confirmed that the development of osteo-organoid underwent an immunosuppressive microenvironment at the fibroproliferation and osteochondral differentiation stages and that the osteo-organoid stably harbored multiple types of immune cells at the final marrow generation stage.

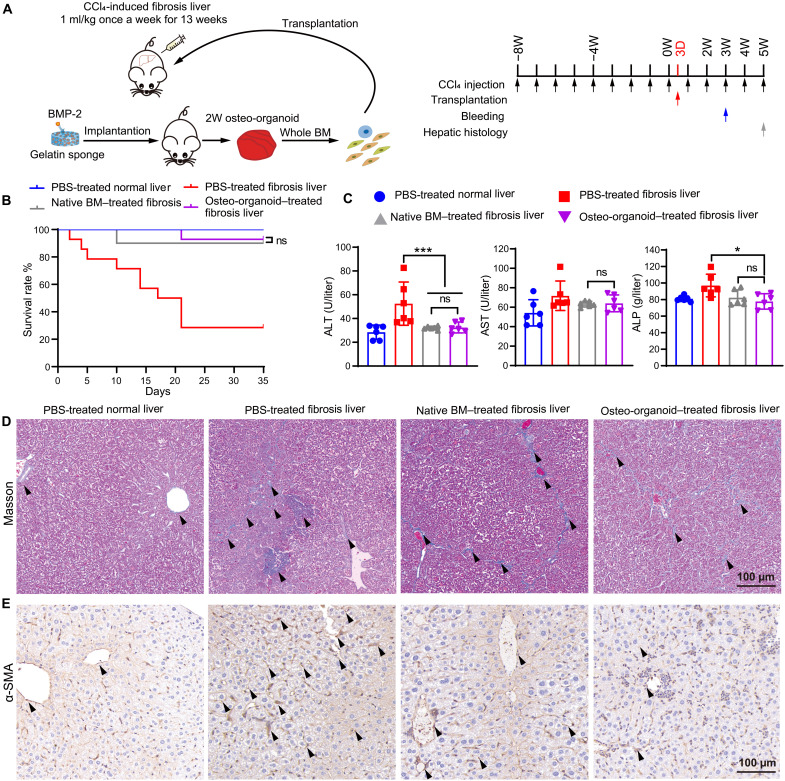

Osteo-organoid–derived cells reduce CCl4-induced liver fibrosis in mice

MSC-based cell therapy for treating chronic liver fibrosis has been seen as an effective therapeutic strategy (33, 34). To further characterize the therapeutic potentials and functions of the osteo-organoid–derived cells, we created a chronic fibrosis liver model and transplanted the 2-week osteo-organoid–derived cells, which were abundant in MSCs, into the liver fibrosis mice (Figs. 1J and 4A). The mortality data confirmed that the transplantation of both native BM cells and osteo-organoid–derived cells reduced the mortality of mice but showed no significant difference between the two groups (Fig. 4B). In the meantime, we observed that the values of typical hepatic function–associated proteins in the native BM–treated group were similar to that in the osteo-organoid–treated fibrosis liver group at week 3 (Fig. 4C). The alanine transaminase (ALT), aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) secretion almost restored to the normal level in the native BM–treated group and osteo-organoid–treated fibrosis liver group at week 3 after transplantation compared to those in the PBS-treated normal liver group. Together, these data confirm that the osteo-organoid–derived cells achieved a similar therapeutic effect in repairing the hepatic injuries compared to the native BM cells and that both cells recover partial functions of damaged liver tissue.

Fig. 4. Osteo-organoid–derived cells mitigate liver fibrosis in mice.

(A) Experimental scheme of fibrosis liver tissue model. BMP-2–loaded scaffolds (30 μg) were implanted into the internal muscle pocket near the femur of mice for 2 weeks to generate the osteo-organoids (donors). Specifically, wild-type (WT) mice in the PBS-treated normal liver group received no CCl4 intraperitoneal injection and transplanted with PBS. WT mice in the PBS-treated fibrosis liver, native BM–treated fibrosis liver, and osteo-organoid–treated fibrosis liver groups received CCl4 intraperitoneal injection once per week for 13 weeks and transplanted with PBS, native BM cells, or osteo-organoid–derived cells 3 days after the start time point, respectively. (B) The mortality of mice in each group. n = 10 to 14 biological replicates. (C) All WT mice in the three groups were bled for determining the value of ALT, AST, and ALP 3 weeks after the start time point. n = 6 biological replicates. (D and E) Masson staining (D) and α-SMA (E) immunostaining of liver tissue in recipient mice 5 weeks after the start time point. Black arrowheads indicate the deposited collagen. Scale bars, 100 μm. Data are presented as means ± SD. *P < 0.05, and ***P < 0.001. Survival benefit was determined using a log-rank test (B). Statistical differences among groups were identified by one-way ANOVA, followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests (C).

Histological images confirmed that the damaged hepatic tissue became reconstituted at week 5 after treatment (Fig. 4, D and E). Masson staining and α–smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) staining of liver tissue from four groups at week 5 confirmed that the structure of hepatic lobules began to recover with the decrease in relative majority portal tract expansion in both the native BM–treated and osteo-organoid–treated groups. There was nearly no discernible normal lobular architecture in the PBS-treated fibrosis liver group, which presented a quantity of collagen fibers and depositions in shown in Fig. 4 (D and E). Together, these staining images demonstrated that both the native BM cells and osteo-organoid–derived cells functionally repaired the hepatic injuries and reconstituted the damaged liver tissue.

Osteo-organoid–derived cells reconstitute the immune system in sublethally irradiated mice

HSC transplantation is an effective approach in treating irradiation-induced immune system injury (35, 36). The rapid recovery of WBCs is essential for the recipients to resist infection after transplantation (32). To determine whether the osteo-organoid–derived cells could reconstitute the damaged immune system, we transplanted the cells derived from in vivo osteo-organoid (incubated for 12 weeks) into sublethally irradiated mice (Fig. 5A). Hematological data revealed that the number of WBC in the 5–gray (Gy) osteo-organoid–treated group at week 4 after transplantation increased significantly compared to that in the native BM–treated group (Fig. 5B). The number of RBC restored to the normal level both in the 5-Gy osteo-organoid–treated and native BM–treated groups as early as the second week after transplantation (Fig. 5C). The number of platelet (PLT) both in the 5-Gy osteo-organoid–treated and native BM–treated groups at week 2 after transplantation also increased significantly compared to that in the PBS-treated group (Fig. 5D). Together, these data confirmed that the osteo-organoid–derived cells had a stronger capacity in promoting the recovery of WBC compared to the native BM cells.

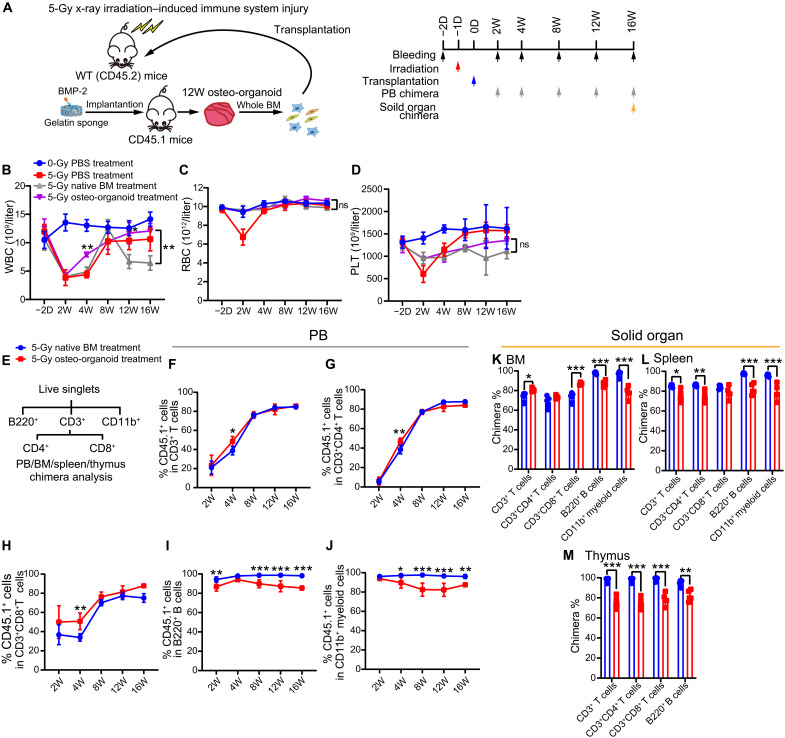

Fig. 5. Osteo-organoid–derived cells restore the peripheral immune system and solid immune organ in sublethally irradiated mice.

(A) Experimental scheme. BMP-2–containing gelatin sponges (30 μg) were implanted into the internal muscle pocket near the femur of mice for 12 weeks to generate the osteo-organoids (donors, CD45.1). Specifically, WT mice in the 0-Gy PBS-treated group received no irradiation and transplanted with PBS. WT mice in the 5-Gy PBS-treated, 5-Gy native BM–treated, and 5-Gy osteo-organoid–treated groups received 5-Gy irradiation 1 day before transplantation and transplanted with PBS, native BM cells, or osteo-organoid–derived cells, respectively. (B to D) PB cells from the four groups were analyzed at indicated time points. n = 4 to 5 biological replicates. (E) Typical gating strategy of chimera analysis for PB, BM, spleen, and thymus in recipient mice. (F to J) PB chimerism in the 5-Gy native BM–treated and 5-Gy osteo-organoid–treated groups was analyzed at the indicated time points. n = 4 to 5 biological replicates. (K to M) BM, spleen, and thymus chimerism in the 5-Gy native BM–treated and 5-Gy osteo-organoid–treated groups was analyzed at 16 weeks after transplantation. n = 4 to 5 biological replicates. Data are presented as means ± SD. Statistical differences among groups were identified by two-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test (B to D and F to M). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

We then measured the chimera of native BM cells and osteo-organoid–derived cells in the blood, BM, spleen, and thymus of recipients to evaluate the contribution of transplanted cells in the reconstituted immune system of irradiated mice (fig. S9). For peripheral blood (PB) chimera, we found that the donor-derived CD3+ T cells, B220+ B cells, and CD11b+ myeloid cells maintained high chimerism (typically above 80%) at the last time point both in the 5-Gy osteo-organoid–treated and native BM–treated groups (Fig. 5, E to J). Consistent with the hematological data, the osteo-organoid–derived cells exhibited a stronger reconstitution capacity compared to the native BM–derived cells in T cell subset chimera (Fig. 5, F to H). In general, the donor-derived CD3+ T cell subsets achieved a stable chimera 8 weeks after transplantation, whereas the donor-derived B220+ B cell and CD11b+ myeloid cell subset achieved a stable chimera as early as 2 weeks after transplantation (Fig. 5, F to J). Together, these data confirmed that the donor osteo-organoid–derived cells accelerated the recovery of T cell subsets in PB compared to the donor native BM cells.

For the chimera of recipients’ BM, the donor osteo-organoid–derived cells showed a higher T cell chimera and a lower B cell and myeloid cell chimera, compared to the donor native BM cells, at the end time point (Fig. 5K). Donor cells in both 5-Gy osteo-organoid–treated and 5-Gy native BM–treated groups exhibited high T cell, B cell, and myeloid cell chimera (typically above 80%) in recipients’ spleen and thymus (Fig. 5, L and M). Together, these data confirmed that both the osteo-organoid–derived cells and native BM cells stably reconstituted the impaired immune system in solid organ of irradiated mice and that the osteo-organoid–derived cells showed an enhanced T cell reconstitution capacity compared to the native BM cells in recipients’ BM.

Profile of cytokine expression during the development of osteo-organoid

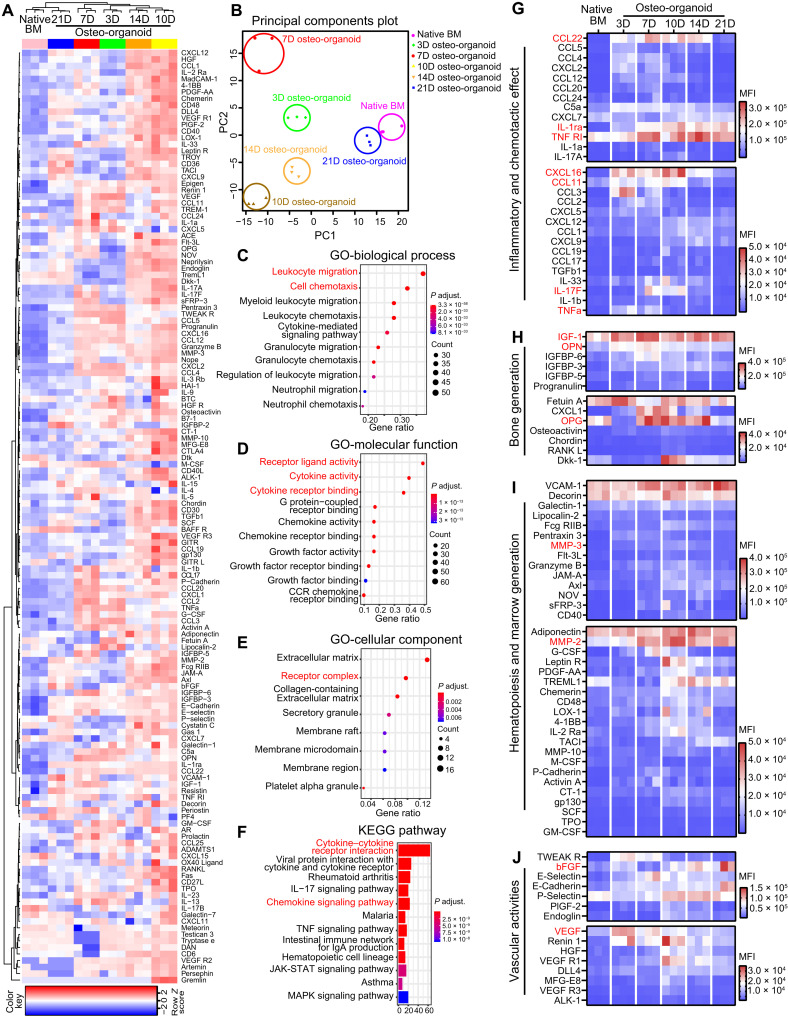

The development of in vivo osteo-organoid is a rapid and dynamic process, and the basic law of cytokine expression during this process still remains largely unknown. To illustrate the dynamic process of secreted cytokines during the osteo-organoid development and further provide informative cues on developing a more effective osteo-organoid–based cell therapy strategy, we screened the proteins in osteo-organoid at different developmental stages via a high-throughput protein array. We identified 143 differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) among the osteo-organoid at days 3, 7,10, 14, and 21 after implantation, as well as in the native BM group. The subsequent hierarchical clustering analysis showed that the expression of most DEPs in the osteo-organoid was highly elevated at the fibroproliferation and osteochondral differentiation stages, and then the expression of DEPs in the osteo-organoid gradually decreased to the native BM level, which proved the maturation of osteo-organoid at the marrow generation stage since day 21 after implantation (Fig. 6A). The principal components analysis (PCA) also confirmed that the protein expression profile in the osteo-organoid at day 21 after implantation was most similar to that in the native BM (Fig. 6B). The protein expression profile, as well as the histological imaging and flow cytometric data, confirmed that the osteo-organoids are able to stably produce therapeutic cells, such as HSPCs and immune cells, at the marrow generation stage since day 21 after implantation.

Fig. 6. Cytokines with varied expression levels regulate the recruitment and differentiation of different cell populations during osteo-organoid development.

(A) Heatmap representing the results of the protein array analysis performed on the supernatant of the native BM and the osteo-organoid at days 3, 7, 10, 14, and 21 after implantation. DEPs among all six groups are hierarchically clustered. (B) PCA was performed among all six groups. (C to E) Enriched GO terms of associated biological processes (C), molecular functions (D), and cellular components (E) from all DEPs are shown. (F) KEGG pathway analysis for all DEPs. (G to J) Representative protein expression of associated inflammatory and chemotactic effect (G), bone generation (H), hematopoiesis and marrow generation (I), and vascular activities (J) in native BM and the osteo-organoid. n = 3 biological replicates. MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

The gene ontology (GO) analysis and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis enriched on leukocyte migration– and cell chemotaxis–associated terms (Fig. 6, C to F). At the fibroproliferation and osteochondral differentiation stages, elevated expression of chemokines in the osteo-organoid—such as C-C motif chemokine ligand 22 (CCL22), C-X-C motif chemokine ligand 16 (CXCL16), and CCL11—facilitated the recruitment of MSCs and immune cells and benefited the harvest of therapeutic MSCs (Fig. 6G). An excessively inflammatory microenvironment has been widely reported for its adverse effects to bone regeneration and repair (37, 38). Consistent with the elevated CD4+:CD8+ T cell ratio at the initial developmental stages, the elevated expression of inflammatory cytokines including tumor necrosis factor–α (TNF-α) and interleukin-17F (IL-17F) was accompanied by a continuously high expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines including IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra) and soluble TNF receptor 1 (TNF R1), which contributed to creating a regeneration-friendly immunosuppressive microenvironment (Fig. 6G).

Moreover, the elevated expression of osteochondral differentiation–associated osteogenic, bone matrix–degradative, and angiogenic cytokines—such as insulin-like growth factors (IGF-1), osteopontin (OPN), osteoprotegerin (OPG), matrix metalloproteinase–3 (MMP-3), MMP-2, basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)—promoted the maturation of osteo-organoid (Fig. 6, H to J). The homeostasis of cytokine expression in the osteo-organoid at the marrow generation stage further guaranteed the stable production of therapeutic cells. Together, these results confirm that a series of subsequently expressed cytokines regulate the maturation and homeostasis of osteo-organoid and that the cell migration–related pathways and typical chemotactic factors, such as CCL22 and CXCL16, deserve further investigation.

DISCUSSION

Achieving a large number of therapeutic cells, especially stem and immune cells, for cell therapies remains a profound unmet demand (3–5). Despite much progress, the medical utility of induced pluripotent stem cells and direct transdifferentiated stem cells is still limited by the low efficiency of reprogramming and concerns about potential tumorigenicity (39, 40). In the present study, we generated a functional in vivo osteo-organoid, which harbors abundant stem and immune cells, based on endochondral ossification as triggered by a simple BMP-2–loaded gelatin scaffold implant. We detected three distinct osteo-organoid developmental stages: fibroproliferation, osteochondral differentiation, and marrow generation. We further demonstrated the therapeutic capacity of cells harvested from the osteo-organoid at the osteochondral differentiation stage in rescuing mice from CCl4-induced fatal liver fibrosis and used marrow generation–stage cells to successfully reconstitute the impaired immune system of irradiated recipient mice.

This in vivo osteo-organoid strategy is distinct conceptually and in practice from other strategies (1, 41–43), as it supports in vivo generation and harvest of large numbers of diverse therapeutically autologous cells at different developmental stages. The cell number and cell composition dynamically change with the maturation of osteo-organoid. This in vivo osteo-organoid has similar cell types to native BM, including abundant MSCs during the osteochondral differentiation stage and both HSPCs and immune cells during the marrow generation stage. We therapeutically applied the MSCs to a chronic liver fibrosis model and successfully mitigated liver fibrosis symptoms. We applied the HSPCs and immune cells for the reconstitution of an impaired hematopoietic system.

By controlling the incubation and cell harvest timing, our osteo-organoid strategy can be used to produce cells appropriate for treating different diseases. This contrasts with typical current practices, wherein MSCs, HSPCs, and multiple types of immune cells are produced in vitro from donor progenitor cells over several weeks, with complex cell culture requirements. By providing therapeutic cells in vivo without the need for ex vivo culture, adopting the osteo-organoid strategy with a BMP-2–loaded scaffold could markedly simplify the acquisition of therapeutic cells. Because BMP-2 has been widely used clinically, this kind of BMP-2–loaded scaffold could be designed as an off-the-shelf and clinical-grade product for further clinical use.

Our work provides a useful resource to understand the details and features on histological structure, cell composition, and cytokine expression profile of the BMP-2–loaded scaffold–triggered in vivo osteo-organoid at different developmental stages. In general, given the histologic data and high-throughput protein array data, the most active bone generation and resorption activities at the osteochondral differentiation stage were accompanied with a series of highly expressed cytokines. Until 3 weeks after implantation, the in vivo osteo-organoid has formed a marrow-like architecture, and the cell number and cell composition of in vivo osteo-organoid became stable. The development of osteo-organoid exhibited an immunosuppressive microenvironment at the fibroproliferation and osteochondral differentiation stages, which relied on the high CD4+:CD8+ T cell ratio and the negative feedback regulatory mechanisms: The high expression of inflammatory TNF-α, IL-1a, and IL-1b was accompanied with the high expression of anti-inflammatory IL-1ra and TNF R1.

We have developed a highly reproducible cell-free strategy to harvest abundant, therapeutically autologous stem cells and immune cells using BMP-2–loaded scaffolds. With this cell-free strategy, we activate the limited regenerative capacity of mammals and recruit multiple types of resident autologous cells into the osteo-organoid synchronously. For further clinical translation, we increase the number of osteo-organoid–derived therapeutic cells via controlling the BMP-2 dosage and scaffold volume. Moreover, we construct the osteo-organoid in the immediate family member of patients to avoid the potential transmission of an infectious pathogen between hosts belonging to different species on one hand and relevant ethical issues on the other hand. Together, the results suggest that the osteo-organoid–derived cells could be a promising cell source for cell therapies.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fabrication of scaffolds

Recombinant human BMP-2 (rhBMP-2) was provided by Shanghai Rebone Biomaterials Co. The scaffolds were prepared as described previously (44). Briefly, under sterile conditions, 10, 30, and 50 μl of rhBMP-2 solution (1.00 mg/ml), as well as 30 μl of PBS, were added onto a porous absorbable gelatin sponge (10 mm long, 5 mm wide, and 5 mm thick; Jiangxi Xiangen Co.), freeze-dried, and stored at −20°C. All kinds of gelatin scaffolds were cylindrically shaped and implanted into the muscle pouch of mice (20210506-01).

Animal and animal assays

Male C57BL/6 (CD45.2) mice and C57BL/6.SJL-Ptprca Pepcb/BoyJ (CD45.1) mice were purchased from the Experimental Animal Center of East China Normal University. All the mice used were 8 to 10 weeks old and maintained in the animal facility of Shanghai Jiao Tong University Animal Care and Use Committees. All the experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committees of Shanghai Jiao Tong University Animal Care and Use Committees (20210506-01).

For the implantation assay, we anesthetized the mice with 1% (w/v) pentobarbital sodium solution after shaving the hair on the legs with a shaver. Then, we sterilized the muscle pouch of the mice with 70% alcohol (Greagent). After these preparatory steps, we cut off the skin and muscle pouch with micro scissors, placed the scaffold into the muscle, and sutured the wound. The mice were placed onto a warm-up station until they revived. The induced tissue was removed at the indicated time points for subsequent series analysis.

To evaluate the systematic effect of scaffold implantation to PB and native BM, the PB from nontreated, PBS-treated, and BMP-treated groups was collected by retro-orbital puncture at the indicated time points and analyzed by pocH-100i (Sysmex). The blood serums from nontreated, PBS-treated, and BMP-treated groups and native BM supernatants from nontreated and BMP-treated groups at the indicated time point were collected and analyzed. Specifically, the PB was stored at 4°C for 2 hours and centrifuged at 3000g for 20 min. The serum was then pipetted carefully to the other empty tube and centrifuged at 3000g for 20 min to further remove the debris. The native BM from the nontreated and BMP-treated groups was crushed in 600 μl of Hanks’ balanced salt solution (HBSS) without Ca2+ and Mg2+ (Gibco) with a mortar and pestle at the indicated time points. The obtained supernatants were then centrifuged at 3000g for 20 min. The supernatant (400 μl) from each sample was pipetted for subsequent LEGENDplex bead–based quantitative analysis.

Immune system reconstitution assay

Immune system reconstitution assays were performed using the CD45.1/CD45.2 congenic system. Whole-marrow cells collected from two CD45.1+ osteo-organoids induced by a BMP-2–loaded scaffold for 3 months or two CD45.1+ femurs were transplanted into sublethally irradiated (5-Gy) CD45.2 recipients via retro-orbital sinus injection. The CD45.1/CD45.2 chimeric status of recipients’ PB was analyzed at 2, 4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks after transplantation.

Hematological analysis

For the analysis of recipients’ hematology in immune system reconstitution assays, the PB of recipients from 0-Gy PBS treatment, 5-Gy PBS treatment, 5-Gy native BM treatment, and 5-Gy osteo-organoid treatment was collected by retro-orbital puncture at 2 days before and 2, 4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks after transplantation. All blood samples were analyzed within 2 hours using a Sysmex hematological analyzer (pocH-100i).

Fibrosis liver repair assay

Carbon tetrachloride (CCl4)–induced fibrosis liver model was performed as previously reported (34). Specifically, mice were treated with CCl4 (1 ml/kg) dissolved in olive oil (1:1) once a week for 8 weeks. Three days (72 hours) after the eighth injection of CCl4, the whole-marrow cells (1 × 106/200 μl) collected from osteo-organoids induced by BMP-2–loaded scaffolds 2 weeks after implantation, or from native BM or same volume of PBS as a control (described also as PBS-treated fibrosis liver), were transplanted to CCl4-treated recipients. The normal mice treated with the same volume of PBS served as the PBS-treated normal group. The ALT, AST, and ALP of recipients’ PB were analyzed 3 weeks after transplantation using a BS-800M Modular System (Mindray). Live mice in all groups were euthanized 5 weeks after transplantation to assess the extent of liver fibrosis.

In vivo x-ray imaging

For evaluating the time- and dose-dependent effects of rhBMP-2, in vivo x-ray imaging was conducted by iNSiGHT VET DXA (OsteoSys) at weeks 1, 2, 3, 4, and 12 after the implantation. Prone images were obtained from each animal at each time point, and supine images were obtained from each animal at the last time point.

Antibodies and staining reagents

Antibodies used for flow cytometry and immunofluorescence staining are listed in table S1. For flow cytometry analysis, phycoerythrin (PE)–Cy7 anti-B220 (RA3-6B2), PE anti-CD45.1 (A20), fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) anti-CD45.2 (104), PerCp-Cy5.5 anti-CD8a (53-6.7), PE-Dazzle594 anti-CD4 (GK1.5), allophycocyanin (APC) anti-F4/80 (BM8), FITC anti-CD45 (30-F11), PE-Dazzle594 anti-Ter119 (Ter119), BV650 anti-Ly6G (1A8), PerCp-Cy5.5 anti-Ly6C (HK1.4), PE-Cy5 anti-CD8a (53-6.7), BV711 anti-CD4 (GK1.5), BV605 anti-CD11c (N418), PE-Cy5 anti-Ter119 (Ter119), PE anti-CD105 (MJ7/18), BV510 anti-CD48 (HM48-1), FITC anti-CD48 (HM48-1), PE-Cy7 anti-CD150 (TC15-12F12.2), PE anti-CD150 (TC15-12F12.2), AF700 anti–Sca-1 (D7), PE-Cy7 anti–Sca-1 (D7), PE-Cy5 anti–c-kit (2B8), and BV711 anti-CD16/32 (93) were purchased from BioLegend. V450 anti-CD3 (17A2), BV480 anti–major histocompatibility complex class II (MHC-II) (M5/114.15.2), BUV395 anti–immunoglobulin M (IgM) (R6-60.2), BV650 anti-CD31 (390), PerCp-Cy5.5 anti-lineage cocktail, and PE-CF594 anti-CD135 (A2F10.1) were purchased from BD Biosciences. AF700 anti-CD11b (M1/70), PE-Cy5 anti-CD45 (30-F11), bio-anti-CD140a (APA5), and bio-anti-CD34 (RAM34) were purchased from eBioscience. APC anti-CD3e (145-2C11) was purchased from Tonbo. PE-strep and SB780-strep secondary antibody were purchased from eBioscience. Hoechst33342 solution (H1399) was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific.

For immunofluorescence staining, rabbit anti-CD31 and rabbit anti-Osterix were purchased from Abcam, and rat anti-EMCN was purchased from Santa Cruz. AF488 anti-rat and AF555 anti-rabbit antibodies were purchased from Abcam. ProLong gold antifade reagent with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (8961S) was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (CST).

Flow cytometry

The mice were euthanized by cervical dislocation, and 70% (v/v) ethanol was sprayed to the anatomical position. The hindlimbs were carefully disconnected from the trunk, and the muscles were removed from femurs and osteo-organoid using micro scissors. Then, the bones were rubbed carefully to remove the attached soft tissue with a piece of gauze. Some of the samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde solution for 24 hours at room temperature (RT) for histology processing or micro–computed tomography scanning.

For HSPC and multiple-lineage cell staining, native femurs or osteo-organoids were then crushed in staining buffer (BioLegend) with a mortar and pestle. The cell suspensions were then centrifuged at 300g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was removed, and the cells were lysed using ammonium chloride (BD Biosciences). Then, the cells were washed with staining buffer (BioLegend) and filtered with a 40-μm cell strainer. The obtained single-cell suspensions were stained with an antibody cocktail for 30 min at 4°C. Last, the cells were washed and resuspended with staining buffer again and left for further flow cytometry analysis.

For live-cell and HSPC cell cycle analysis, the single-cell suspensions of native femurs or osteo-organoids were obtained just as the procedure above and were stained with an antibody cocktail for 30 min at 4°C. Last, the cells were washed and resuspended in Hoechst33342 solution (10 μg/ml) for 30 min and left for further flow cytometry analysis.

For MSC and EC staining, native femurs or osteo-organoids were also crushed in staining buffer (BioLegend) with a mortar and pestle. Whole native BM cells and osteo-organoid–harboring cells were subjected to enzymatic digestion at 37°C for 20 min, similar to the method by Yue et al. (45), to obtain single-cell suspensions. The supernatant was removed, and the cells were lysed using ammonium chloride (BD Biosciences). Then, the cells were washed with staining buffer (BioLegend) and filtered with a 40-μm cell strainer. The obtained single-cell suspensions were stained with an antibody cocktail for 30 min at 4°C. The cells were washed and stained with goat anti-rat AF488 and strep-SB780 secondary antibody for an additional 60 min at 4°C. Last, the cells were washed and resuspended with staining buffer once more and left for further flow cytometry analysis.

The PB of recipients was collected by retro-orbital puncture. RBCs were lysed using ammonium chloride (BD Biosciences), and then the cells were stained to analyze the CD45.1/CD45.2 chimerism of recipients.

Flow cytometric analyses were carried out using a Fortessa X-20 equipped with FACSDiva 8.1 software (all BD Biosciences) or a CytoFlex LX equipped with Cytoexpert 2.3 software (Beckman Coulter). Dead cells were excluded using a Live/Dead Fixable Far Red Dead Cell Stain Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) or a Zombie UV Fixable Viability Kit (BioLegend). Data were analyzed with FlowJo 10.6 (Tree Star). UMAP plot for CD45+ populations in multiple-lineage cells among native BM and 1- to 4-week osteo-organoids groups was conducted using the UMAP plugin of FlowJo. Specifically, CD45+ populations in each group were downsampled to 50,000 events. Then, all downsampled groups were concatenated for UMAP analysis.

Blood serum analysis

Blood serums from nontreatment, PBS treatment, and BMP treatment groups and supernatants from the nontreatment and BMP treatment groups were collected and analyzed to determine the level of inflammatory cytokines [CCL2, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), interferon-1β (IFN-1β), IFN-1γ, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, IL-12 (p70), IL-17A, IL-23, IL-27, and TNF-α], proinflammatory chemokine (CCL2, CCL3, CCL4, CCL5, CCL11, CCL17, CCL20, CXCL1, CXCL5, CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL13), and HSC-associated cytokines [IL-34, IL-5, M-CSF, thrombopoietin (TPO), IL-6, GM-CSF, IL-15, transforming growth factor–β1, IL-3, leukemia inhibitory factor, stem cell factor, erythropoietin (EPO), and CXCL12] by LEGENDplex bead–based quantitative analysis according to the manufacturer’s instructions (BioLegend).

Protein array analysis

The implanted BMP-2–loaded scaffolds were explanted at the given time points. Native femurs or explanted scaffolds were then crushed in 600 μl of HBSS without Ca2+ and Mg2+ (Gibco) with a mortar and pestle. Then, the obtained suspensions were centrifuged at 3000g for 20 min. We pipetted 400 μl of the supernatant from each sample for subsequent QAM-CAA-4000 protein array analysis (RayBiotech). We conducted the protein array analysis according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The mean fluorescence intensity was quantified with an Axon GenePix laser scanner equipped with a Cy3 wavelength (red channel). PCA plots were generated using the prcomp function in R. The ggfortify data package from R/Bioconductor was used. GO enrichment and KEGG pathway analysis were conducted with the cluster Profiler from R/Bioconductor, and proteins differentially expressed with an adjusted P value below 0.05 were used for analysis with Fisher’s exact test.

Histology/immunohistochemistry

Freshly explanted samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight and decalcified in 0.5 M EDTA solution for another 7 days. H&E staining, safranin-O staining, and TRAP staining were performed on paraffin sections (5 μm thick) using a standard protocol as previously reported (46). Last, the samples were examined using digital slide scanners (Pannoramic MIDI).

Immunofluorescence staining

The excised osteo-organoid and native bone were demineralized with 0.5 M EDTA solution for 7 days and incubated in 20% (w/v) sucrose with 2% polyvinyl pyrrolidone (Sigma-Aldrich) in PBS solution at 4°C overnight. All samples were placed on a shaker during incubation. The samples were transferred to a mold, embedded with optimum cutting temperature compound, and frozen in a −80°C freezer. The frozen tissue blocks were sectioned with a cryotome cryostat (at −20°C) to a thickness of 10 or 40 μm. For immunofluorescence staining, cells were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 at RT for 4 min, blocked with 10% (v/v) goat serum at RT for 30 min in PBS, and incubated with CD16/32 (1:100). The sections were stained with CD31 (1:100), EMCN (1:100), and Osterix (1:200) overnight at 4°C. As appropriate, secondary antibodies labeled with Alexa Fluor 555 (1:400) or Alexa Fluor 488 (1:400) were added, and the samples were mounted with ProLong gold antifade reagent with DAPI (CST). The mounted sections were imaged with a Nikon A1R.

Statistics

All quantitative data expressed as the means ± SD were analyzed with GraphPad Prism 9. Comparisons between two groups were identified by two-tailed Student’s t tests. Statistical differences among groups were identified by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), followed by Tukey’s multiple comparison tests or two-way ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni’s multiple comparison tests. Statistical significance was attained with a greater than 95% confidence level (P < 0.05). For protein array analysis, the raw data were normalized and adapted for subsequent analysis. The general statistics used for significance analysis were one-way ANOVA among all six groups. The limma data package from R/Bioconductor was used. DEPs were defined as those with adjusted P values (adjusted with the Benjamini-Hochberg method) of less than 0.05. The cluster heatmap was calculated with the heatmap.2 function, and the gplots data package from R/Bioconductor was used. Statistical differences among all six groups for specific protein were identified by one-way ANOVA, followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison tests, and the native BM group was set as the control column. Survival benefit was determined using a log-rank test; *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Acknowledgments

Our work on laser scanning confocal microscopy imaging was performed at East China University of Science and Technology (ECUST) with the aid of L. Zhou, Y. Xia, and C. Wang. Our flow cytometry work was performed at Shanghai Jiao Tong University School of Medicine (SHSMU) Flow Cytometry Core with the aid of R. Fu, X. Zhang, and C. Guo, as well as the National Center for Protein Science (Shanghai) with the aid of Y. Wang and Y. Yu. Our x-ray irradiation work was performed at the National Center for Protein Science (Shanghai) with the aid of C. Zheng and H. Chen. We thank X. Ma at East China Normal University (ECNU) Experimental Animal Center for the technical support with rodent surgery. We thank T. Shen at ECUST for the help in schematic design.

Funding: This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China for Innovative Research Groups (no. 51621002), the National Key R&D Program of China (no. 2018YFE0201500), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 31870953), the Foundation of Frontiers Science Center for Materiobiology and Dynamic Chemistry (no. JKVD1211002), Basic Science Center Program (no. T2288102), the Key Program of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (no. 32230059), the Wego Project of Chinese Academy of Sciences [no. (2020) 005], and the Project of National Facility for Translational Medicine (Shanghai) (TMSK-2021-134).

Author contributions: Conceptualization: K.D., Q.Z., C.L., and J.W. Methodology: K.D., Q.Z., S.D., Y.Y., F.Z., S.Z., Y.P., and D.L. Investigation: K.D., Q.Z., S.D., Y.Y., F.Z., S.Z., Y.P., and D.L. Visualization: K.D., Q.Z., and S.D. Funding acquisition: C.L. and J.W. Supervision: C.L. and J.W. Writing—original draft: K.D., Q.Z., C.L., and J.W. Writing—review and editing: K.D., Q.Z., C.L., and J.W.

Competing interests: C.L., K.D., S.D., Q.Z., and J.W. are inventors on two pending patents related to this work filed by East China University of Science and Technology (no. CN 111500533 A, filed 31 January 2019, published 13 August 2020; no. CN 111494711 A, filed 31 January 2019, published 13 August 2020). The authors declare that they have no other competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Figs. S1 to S9

Table S1

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.R. Chen, L. Li, L. Feng, Y. Luo, M. Xu, K. W. Leong, R. Yao, Biomaterial-assisted scalable cell production for cell therapy. Biomaterials 230, 119627 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.R. Weissleder, M. J. Pittet, The expanding landscape of inflammatory cells affecting cancer therapy. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 4, 489–498 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.A. Trounson, C. McDonald, Stem cell therapies in clinical trials: Progress and challenges. Cell Stem Cell 17, 11–22 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.F. P. Barry, J. M. Murphy, Mesenchymal stem cells: Clinical applications and biological characterization. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 36, 568–584 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.A. S. Cheung, D. K. Y. Zhang, S. T. Koshy, D. J. Mooney, Scaffolds that mimic antigen-presenting cells enable ex vivo expansion of primary T cells. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 160–169 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.R. Sugimura, D. K. Jha, A. Han, C. Soria-Valles, E. L. Da Rocha, Y. F. Lu, J. A. Goettel, E. Serrao, R. G. Rowe, M. Malleshaiah, I. Wong, P. Sousa, T. N. Zhu, A. Ditadi, G. Keller, A. N. Engelman, S. B. Snapper, S. Doulatov, G. Q. Daley, Haematopoietic stem and progenitor cells from human pluripotent stem cells. Nature 545, 432–438 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.J. Riddell, R. Gazit, B. S. Garrison, G. Guo, A. Saadatpour, P. K. Mandal, W. Ebina, P. Volchkov, G. C. Yuan, S. H. Orkin, D. J. Rossi, Reprogramming committed murine blood cells to induced hematopoietic stem cells with defined factors. Cell 157, 549–564 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.L. T. Vo, G. Q. Daley, De novo generation of HSCs from somatic and pluripotent stem cell sources. Blood 125, 2641–2648 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.J. R. Passweg, H. Baldomero, P. Bader, C. Bonini, S. Cesaro, P. Dreger, R. F. Duarte, C. Dufour, J. Kuball, D. Farge-Bancel, A. Gennery, N. Kroger, F. Lanza, A. Nagler, A. Sureda, M. Mohty; for the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) , Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in Europe 2014: More than 40 000 transplants annually. Bone Marrow Transplant. 51, 786–792 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.B. A. David, P. Kubes, Exploring the complex role of chemokines and chemoattractants in vivo on leukocyte dynamics. Immunol. Rev. 289, 9–30 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.M. M. Stevens, R. P. Marini, D. Schaefer, J. Aronson, R. Langer, V. P. Shastri, In vivo engineering of organs: The bone bioreactor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 11450–11455 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.C. Scotti, E. Piccinini, H. Takizawa, A. Todorov, P. Bourgine, A. Papadimitropoulos, A. Barbero, M. G. Manz, I. Martin, Engineering of a functional bone organ through endochondral ossification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 3997–4002 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Y. R. Shih, H. Kang, V. Rao, Y. J. Chiu, S. K. Kwon, S. Varghese, In vivo engineering of bone tissues with hematopoietic functions and mixed chimerism. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114, 5419–5424 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.M. Darnell, A. O’Neil, A. Mao, L. Gu, L. L. Rubin, D. J. Mooney, Material microenvironmental properties couple to induce distinct transcriptional programs in mammalian stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E8368–E8377 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.C. Stüdle, Q. Vallmajó-Martín, A. Haumer, J. Guerrero, M. Centola, A. Mehrkens, D. J. Schaefer, M. Ehrbar, A. Barbero, I. Martin, Spatially confined induction of endochondral ossification by functionalized hydrogels for ectopic engineering of osteochondral tissues. Biomaterials 171, 219–229 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.B. Levi, J. S. Hyun, D. T. Montoro, D. D. Lo, C. K. F. Chan, S. Hu, N. Sun, M. Lee, M. Grova, A. J. Connolly, J. C. Wu, G. C. Gurtner, I. L. Weissman, D. C. Wan, M. T. Longaker, In vivo directed differentiation of pluripotent stem cells for skeletal regeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 20379–20384 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.R. A. Carpenter, J. G. Kwak, S. R. Peyton, J. Lee, Implantable pre-metastatic niches for the study of the microenvironmental regulation of disseminated human tumour cells. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2, 915–929 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.A. Reinisch, D. C. Hernandez, K. Schallmoser, R. Majeti, Generation and use of a humanized bone-marrow-ossicle niche for hematopoietic xenotransplantation into mice. Nat. Protoc. 12, 2169–2188 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.A. Reinisch, D. Thomas, M. R. Corces, X. Zhang, D. Gratzinger, W. J. Hong, K. Schallmoser, D. Strunk, R. Majeti, A humanized bone marrow ossicle xenotransplantation model enables improved engraftment of healthy and leukemic human hematopoietic cells. Nat. Med. 22, 812–821 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.B. M. Holzapfel, F. Wagner, L. Thibaudeau, J. P. Levesque, D. W. Hutmacher, Concise review: Humanized models of tumor immunology in the 21st century: Convergence of cancer research and tissue engineering. Stem Cells 33, 1696–1704 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.F. P. Seib, J. E. Berry, Y. Shiozawa, R. S. Taichman, D. L. Kaplan, Tissue engineering a surrogate niche for metastatic cancer cells. Biomaterials 51, 313–319 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.L. C. Martine, B. M. Holzapfel, J. A. McGovern, F. Wagner, V. M. Quent, P. Hesami, F. M. Wunner, C. Vaquette, E. M. De-Juan-Pardo, T. D. Brown, B. Nowlan, D. J. Wu, C. O. Hutmacher, D. Moi, T. Oussenko, E. Piccinini, P. W. Zandstra, R. Mazzieri, J. P. Lévesque, P. D. Dalton, A. V. Taubenberger, D. W. Hutmacher, Engineering a humanized bone organ model in mice to study bone metastases. Nat. Protoc. 12, 639–663 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.B. M. Holzapfel, D. W. Hutmacher, B. Nowlan, V. Barbier, L. Thibaudeau, C. Theodoropoulos, J. D. Hooper, D. Loessner, J. A. Clements, P. J. Russell, A. R. Pettit, I. G. Winkler, J. P. Levesque, Tissue engineered humanized bone supports human hematopoiesis in vivo. Biomaterials 61, 103–114 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.T. Ismail, A. Haumer, A. Lunger, R. Osinga, A. Kaempfen, F. Saxer, A. Wixmerten, S. Miot, F. Thieringer, J. Beinemann, C. Kunz, C. Jaquiéry, T. Weikert, F. Kaul, A. Scherberich, D. J. Schaefer, I. Martin, Case report: Reconstruction of a large maxillary defect with an engineered, vascularized, prefabricated bone graft. Front. Oncol. 11, 1–11 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.K. Dai, S. Deng, Y. Yu, F. Zhu, J. Wang, C. Liu, Construction of developmentally inspired periosteum-like tissue for bone regeneration. Bone Res. 10, 1 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.K. Dai, T. Shen, Y. Yu, S. Deng, L. Mao, J. Wang, C. Liu, Generation of rhBMP-2-induced juvenile ossicles in aged mice. Biomaterials 258, 120284 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.A. P. Kusumbe, S. K. Ramasamy, R. H. Adams, Coupling of angiogenesis and osteogenesis by a specific vessel subtype in bone. Nature 507, 323–328 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.M. J. Yousefzadeh, R. R. Flores, Y. Zhu, Z. C. Schmiechen, R. W. Brooks, C. E. Trussoni, Y. Cui, L. Angelini, K.-A. Lee, S. J. McGowan, A. L. Burrack, D. Wang, Q. Dong, A. Lu, T. Sano, R. D. O’Kelly, C. A. McGuckian, J. I. Kato, M. P. Bank, E. A. Wade, S. P. S. Pillai, J. Klug, W. C. Ladiges, C. E. Burd, S. E. Lewis, N. F. LaRusso, N. V. Vo, Y. Wang, E. E. Kelley, J. Huard, I. M. Stromnes, P. D. Robbins, L. J. Niedernhofer, An aged immune system drives senescence and ageing of solid organs. Nature 594, 100–105 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.D. McGonagle, A. V. Ramanan, C. Bridgewood, Immune cartography of macrophage activation syndrome in the COVID-19 era. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 17, 145–157 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.K. Nakamura, Enhancement of allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell engraftment and prevention of GvHD by intra-bone marrow bone marrow transplantation plus donor lymphocyte infusion. Stem Cells 22, 125–134 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Y. Z. Cui, H. Hisha, G. X. Yang, T. X. Fan, T. Jin, Q. Li, Z. Lian, S. Ikehara, Optimal protocol for total body irradiation for allogeneic bone marrow transplantation in mice. Bone Marrow Transplant. 30, 843–849 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.N. J. Shah, A. S. Mao, T. Y. Shih, M. D. Kerr, A. Sharda, T. M. Raimondo, J. C. Weaver, V. D. Vrbanac, M. Deruaz, A. M. Tager, D. J. Mooney, D. T. Scadden, An injectable bone marrow–like scaffold enhances T cell immunity after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Nat. Biotechnol. 37, 293–302 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Y. Watanabe, A. Tsuchiya, S. Seino, Y. Kawata, Y. Kojima, S. Ikarashi, P. J. Starkey Lewis, W. Y. Lu, J. Kikuta, H. Kawai, S. Yamagiwa, S. J. Forbes, M. Ishii, S. Terai, Mesenchymal stem cells and induced bone marrow-derived macrophages synergistically improve liver fibrosis in mice. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 8, 271–284 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.I. Sakaida, S. Terai, N. Yamamoto, K. Aoyama, T. Ishikawa, H. Nishina, K. Okita, Transplantation of bone marrow cells reduces CCl 4-induced liver fibrosis in mice. Hepatology 40, 1304–1311 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.D. Niederwieser, H. Baldomero, J. Szer, M. Gratwohl, M. Aljurf, Y. Atsuta, L. F. Bouzas, D. Confer, H. Greinix, M. Horowitz, M. Iida, J. Lipton, M. Mohty, N. Novitzky, J. Nunez, J. Passweg, M. C. Pasquini, Y. Kodera, J. Apperley, A. Seber, A. Gratwohl; for the Worldwide Network of Blood and Marrow Transplantation (WBMT) , Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation activity worldwide in 2012 and a SWOT analysis of the Worldwide Network for Blood and Marrow Transplantation Group including the global survey. Bone Marrow Transplant. 51, 778–785 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.M. Lv, Y. Chang, X. Huang, Update of the “Beijing Protocol” haplo-identical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 54, 703–707 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.A. Salhotra, H. N. Shah, B. Levi, M. T. Longaker, Mechanisms of bone development and repair. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 21, 696–711 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Y. Shu, Y. Yu, S. Zhang, J. Wang, Y. Xiao, C. Liu, The immunomodulatory role of sulfated chitosan in BMP-2-mediated bone regeneration. Biomater. Sci. 6, 2496–2507 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.S. Yamanaka, Pluripotent stem cell-based cell therapy—Promise and challenges. Cell Stem Cell 27, 523–531 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.J. Xu, Y. Du, H. Deng, Direct lineage reprogramming: Strategies, mechanisms, and applications. Cell Stem Cell 16, 119–134 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.P. E. Bourgine, T. Klein, A. M. Paczulla, T. Shimizu, L. Kunz, K. D. Kokkaliaris, D. L. Coutu, C. Lengerke, R. Skoda, T. Schroeder, I. Martin, In vitro biomimetic engineering of a human hematopoietic niche with functional properties. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115, E5688–E5695 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.A. García-García, T. Klein, G. Born, M. Hilpert, A. Scherberich, C. Lengerke, R. C. Skoda, P. E. Bourgine, I. Martin, Culturing patient-derived malignant hematopoietic stem cells in engineered and fully humanized 3D niches. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 118, e2114227118 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.V. Bunpetch, Z. Y. Zhang, X. Zhang, S. Han, P. Zongyou, H. Wu, O. Hong-Wei, Strategies for MSC expansion and MSC-based microtissue for bone regeneration. Biomaterials 196, 67–79 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.L. Cao, J. Wang, J. Hou, W. Xing, C. Liu, Vascularization and bone regeneration in a critical sized defect using 2-N,6-O-sulfated chitosan nanoparticles incorporating BMP-2. Biomaterials 35, 684–698 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.R. Yue, B. O. Zhou, I. S. Shimada, Z. Zhao, S. J. Morrison, Leptin receptor promotes adipogenesis and reduces osteogenesis by regulating mesenchymal stromal cells in adult bone marrow. Cell Stem Cell 18, 782–796 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.H. Xie, Z. Cui, L. Wang, Z. Xia, Y. Hu, L. Xian, C. Li, L. Xie, J. Crane, M. Wan, G. Zhen, Q. Bian, B. Yu, W. Chang, T. Qiu, M. Pickarski, L. T. Duong, J. J. Windle, X. Luo, E. Liao, X. Cao, PDGF-BB secreted by preosteoclasts induces angiogenesis during coupling with osteogenesis. Nat. Med. 20, 1270–1278 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figs. S1 to S9

Table S1