Abstract

Streptococcal protective antigen (Spa) is a newly described surface protein of group A streptococci that was recently shown to evoke protective antibodies (J. B. Dale, E. Y. Chiang, S. Liu, H. S. Courtney, and D. L. Hasty, J. Clin. Investig. 103:1261–1268, 1999). In this study, we have determined the complete sequence of the spa gene from type 18 streptococci. Purified, recombinant Spa protein evoked antibodies that were bactericidal against type 18 streptococci, confirming the presence of protective epitopes. Sera from patients with acute rheumatic fever contained antibodies against recombinant Spa, indicating that the Spa protein is expressed in vivo and is immunogenic in humans. To determine the role of Spa in the virulence of group A streptococci, we created a series of insertional mutants that were (i) Spa negative and M18 positive, (ii) Spa positive and M18 negative, and (iii) Spa negative and M18 negative. The mutants and the parent M18 strain (18-282) were used in assays to determine resistance to phagocytosis, growth in human blood, and mouse virulence. The results show that Spa is a virulence determinant of group A streptococci and that expression of both Spa and M18 is required for optimal virulence of type 18 streptococci.

Group A streptococci (GAS) are major human pathogens that cause a wide variety of illnesses, ranging from uncomplicated pharyngitis and pyoderma to life-threatening infections such as necrotizing fasciitis and toxic shock syndrome (23). The virulence of GAS is determined in part by their ability to resist opsonization by complement and phagocytic killing by neutrophils (14). It has been known for many years that these virulence characteristics are mediated in large part by the M protein on the surface of the organisms (16). In addition, the M proteins contain protective epitopes that elicit opsonic antibodies that promote phagocytic killing in the immune host (16). Previous studies have shown that insertional inactivation of the emm gene in some GAS serotypes results in an avirulent phenotype (7, 19).

In a recent study of type 18 streptococci, we found that inactivation of the emm 18 gene had only a minor effect on the ability of the mutant to grow in human blood and on the 50% lethal dose (LD50) in mice compared to the M-positive parent strain (10). We used the M-negative mutant to identify a new surface protein, streptococcal protective antigen (Spa), that was distinct from M protein and contained protective epitopes which elicited bactericidal antibodies (10). The present study was undertaken to determine whether Spa functions as a virulence determinant of type 18 streptococci. Using a series of M-negative and Spa-negative mutants, we show that both of these surface proteins contribute to the virulence of type 18 streptococci. In addition, we have cloned and sequenced the complete spa gene, which allowed a direct comparison of its structure to that of emm genes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The parent type 18 streptococcal strain 87-282 (designated 18-282) and its M-negative mutant, M18Ω, have been described previously (10, 11). Escherichia coli strain DH5α was used for all molecular cloning experiments except with plasmid pQE-30, which was maintained in E. coli M15.

Cloning, expression, and purification of recombinant Spa (rSpa).

The first 636 bp of spa18, encoding the NH2-terminal half of the mature Spa protein, were amplified by PCR and ligated into the expression vector pQE-30 (Qiagen Inc., Valencia, Calif.) containing a six-histidine tag. The resulting construct was used to transform E. coli M15, and clones were selected for ampicillin resistance and screened for expression of Spa protein by a colony blot assay with anti-Spa rabbit serum (10). One colony was selected for high-level expression and purification of the six-histidine-tagged Spa protein as described by the manufacturer (The QIA Expressionist; Qiagen). Eluted proteins were dialyzed against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; 0.05 M NaH2PO4, 0.15 M NaCl [pH 7.4]), and purity was assessed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The recombinant protein migrated as a single band with an apparent molecular mass of 24 kDa.

Preparation of antisera.

The purified rSpa fragment (200 μg) was mixed with the adjuvant Rehydragel (aluminum hydroxide low-viscosity gel; Reheis, Inc., Berkeley Heights, N.J.) and injected intramuscularly into New Zealand White rabbits. Booster injections were given at 4 and 8 weeks, and sera were collected at 0, 4, 6, 8, 9, and 10 weeks. Methods for preparation of antisera against purified native Spa (anti-Spa), a synthetic peptide copying the NH2-terminal 23 amino acids of Spa (anti-Spa [1–23]), and recombinant M18 (anti-rM18) have been described previously (10).

PCR, cloning, and sequencing of spa18.

The sequence of a 636-bp fragment of spa18 had been determined as described previously (10). At the 3′ end of this fragment, a 21-bp sequence (TCTCTTTCAGAGTCAGCAACA) was later found to be an inverted repeat of an upstream sequence. When used as a single primer with type 18 chromosomal DNA, the result was a PCR product of 1,191 bp, which was ligated into pCR2.1-TOPO (Invitrogen Corp., San Diego, Calif.). DNA sequencing was performed by automated techniques at the University of Tennessee Molecular Resources Center, using primers from the 5′ and 3′ flanking ends of the plasmid. The amplicon was found to contain the original 636-bp fragment as well as 550 bp of unique 5′ sequence. A search of the GenBank database showed considerable homology of this region with the signal sequence and 5′ noncoding region of the Streptococcus equi emm gene (GenBank accession no. U73162). Hypothesizing that there would be homologies between the C termini, we constructed a reverse primer from the 3′ noncoding region of the S. equi emm gene (GCCTAGACTGATGAGCCC) for use in combination with a forward primer derived from the 5′ region of the original 636-bp spa18 fragment (GATTCAGTAAGTGGATTAGAGGTGCA). This pair of primers amplified a 1,670-bp product that was ligated into pCR2.1-TOPO. This amplicon was sequenced as described above, using primers from flanking regions of known spa18 sequence.

DNA techniques.

Plasmid DNA was purified with miniprep kits from Qiagen. Chromosomal DNA was prepared from GAS as described by Caparon and Scott (4). Restriction endonucleases and ligases were used as described in the manufacturers' protocols.

The spa18 gene in GAS strain 18-282 and its M-negative mutant M18Ω was insertionally inactivated by a method similar to that described previously (10). Briefly, a BamHI-HindIII 578-bp fragment from the 5′ end of spa18 was ligated into the multiple cloning site of pUC19. The erythromycin resistance (erm) gene from plasmid pNZerm (20) was also ligated into the same cloning site to provide an additional selective marker. The erm gene and its promoter were amplified from pNZerm, using primers containing either EcoRI or BamHI at the 5′ end to facilitate ligation. This new recombinant plasmid was designated pUC19ermspa and was introduced into 18-282 and M18Ω by electroporation.

Southern blot analysis was performed on chromosomal DNA that had been digested with PstI, subjected to 1% agarose gel electrophoresis, and transferred to positively charged nylon membranes (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany), where it was immobilized by UV irradiation. A fragment of pUC19 was labeled with digoxigenin and used as a probe as instructed by the manufacturer (Boehringer Mannheim).

Western blots.

Bacteria were grown overnight in Todd-Hewitt broth (Difco, Detroit Mich.) supplemented with 1% yeast extract, washed twice in PBS, and lysed in Laemmli sample buffer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.). The lysates were centrifuged to remove insoluble debris, subjected to SDS-PAGE on a 12% polyacrylamide gel, and electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Bio-Rad). The membranes were blocked with 3% horse serum (Life Technologies, Grand Island, N.Y.) in Tris-buffered saline (0.05 M Tris, 0.15 M NaCl [pH 7.5]); immunoblotting was performed with anti-rM18 or anti-rSpa diluted 1:100 in Tris-buffered saline, and blots were incubated for 2 h. Bands were identified with peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulins (ICN Biomedicals, Aurora, Ohis), diluted 1:200 in PBS with 1% horse serum and incubated for 2 h. Horseradish peroxidase color development reagent (Bio-Rad) was used as the substrate.

Opsonization and bactericidal assays.

In vitro opsonization and bactericidal assays were performed as previously described (2). Briefly, opsonization assays were performed with whole, heparinized (10 U/ml), nonimmune human blood. A standard inoculum of streptococci, grown to log phase, was added to 0.05 ml of test antiserum and 0.2 ml of blood. For opsonization assays, the number of streptococcal CFU per leukocyte in the mixture was approximately 10. The tubes were rotated end-over-end for 45 min at 37°C. Smears were then made on glass slides and stained with modified Wright's stain (Sigma Diagnostics, St. Louis, Mo.). Opsonization was quantitated by counting 50 consecutive neutrophils per slide and calculating the percentage with associated streptococci (percent opsonization). Bactericidal assays were performed similarly (2) except that fewer bacteria were added to 0.1 ml of test antisera and 0.35 ml of blood, and the mixture was rotated for 3 h at 37°C. Then 0.1-ml aliquots of this mixture were added to melted sheep's blood agar, pour plates were prepared, and viable organisms (CFU) were counted after overnight incubation at 37°C.

Determination of LD50.

Lethality of GAS strains 18-282, M18Ω, 18Spa− (M positive, Spa negative), and 18ΩSpa−(M negative, Spa negative) in the murine model was assessed after intraperitoneal challenge infections of Swiss white mice. Four groups of five mice each were challenged with 10-fold-increasing amounts of exponential growth-phase organisms of each strain. Deaths were recorded for 7 days after challenge infections, and the LD50 was determined by the method of Reed and Muench (22).

ELISAs.

Microtiter wells (Nunc-Immuno modules; Nalge Nunc International, Roskilde, Denmark) were coated with recombinant NH2-terminal peptides of Spa, M1.0, M2, M3, M5, M6, M12, M18, M19, and M24 (5 μg/ml in 0.05 M carbonate [pH 9.6]). The recombinant M protein peptides contained the NH2-terminal 30 to 50 amino acids of the mature M proteins that were repeated in the form of a dimer. Wells without peptide but containing all other reagents served as negative controls. The enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) were performed using human sera from patients with acute rheumatic fever that were obtained as part of an epidemiological investigation of streptococcal sequelae conducted in Saudi Arabia in the 1980s. The sera were serially diluted in PBS (pH 7.4) with 0.05% Tween 20, added to the wells, and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. The wells were washed with 0.15% saline–Tween 20; a 1:2,000 dilution of peroxidase-conjugated goat immunoglobulin G (IgG) to human immunoglobulins (IgG, IgA, and IgM) (ICN Biomedicals) was added and incubated at 37°C for 2 h. After washing, 5-aminosalicylic acid was added, and the A450 was recorded after 15 min by an MR 600 microplate reader (Dynatech Laboratories Inc., Chantilly, Va.). Positive controls were performed by a similar method, although rabbit sera raised against recombinant M proteins and Spa protein were used as the first antibody and peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin (ICN Biomedicals) was used as the second antibody. Antibody levels were graded as specified in the footnote to Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Spa and M type-specific antibodies in human serum, as determined by ELISA

| Seruma | Antibody levelb

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spa | M1 | M2 | M3 | M5 | M6 | M12 | M18 | M19 | |

| 1 | +++ | + | |||||||

| 2 | + | + | |||||||

| 3 | +++ | + | |||||||

| 4 | + | ||||||||

| 5 | |||||||||

| 6 | + | + | +++ | ++++ | + | +++ | |||

| 7 | +++ | +++ | + | ||||||

| 8 | + | ++ | +++ | + | |||||

| 9 | ++++ | + | ++ | + | + | ||||

| 10 | ++ | ||||||||

| 11 | ++++ | ||||||||

| 12 | ++++ | ||||||||

| 13 | + | ++++ | ++ | +++ | |||||

| 14 | +++ | ||||||||

| 15 | + | ++ | |||||||

| 16 | + | ||||||||

| 17 | ++ | ||||||||

| 18 | |||||||||

| 19 | ++++ | ||||||||

| 20 | +++ | ++ | |||||||

The sera of 20 patients with a history of acute rheumatic fever were tested by ELISA for the presence of antibodies against rSpa and recombinant N-terminal fragments of M proteins.

Scored on the basis of absorbance at 450 nm as + (>0.2≤0.4), ++ (>0.4≤0.7), +++ (>0.7≤1.0), and ++++ (>1.0). None of the sera reacted with M24.

Assays for tissue cross-reactive antibodies.

Rabbit antiserum raised against the recombinant NH2-terminal half of Spa (anti-rSpa) was tested for the presence of tissue cross-reactive antibodies by indirect immunofluorescence tests (9) using frozen sections (4 μm) of human myocardium, kidney, basal ganglia, and cerebral cortex. The sections were placed on gelatin-coated slides and fixed with 1% paraformaldehyde for 10 min. The slides were washed with PBS, incubated with anti-rSpa diluted 1:5 in PBS for 30 min at room temperature, and washed thoroughly in PBS. The sections were then incubated with fluorescein-conjugated goat IgG to rabbit IgG (Cappel, West Chester, Pa.) at a dilution of 1:40 in PBS for 30 min at room temperature. After washing, the slides were mounted in Gelvatol and examined in a fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss Inc., New York, N.Y.). Rabbit antisera known to cross-react with human myocardium, kidney, and brain were used as positive controls (3, 9, 15).

Indirect immunofluorescence assays of C3 binding to streptococci.

Patterns of C3 binding to the surface of type 18 streptococci and the mutant strains were determined by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy by methods previously described (11). Briefly, bacteria grown to mid-log phase were incubated in either fresh human serum or plasma, washed, and then incubated with fluorescein-labeled goat anti-human C3 (Cappel). Photographs were made using a Nikon PCM2000 confocal laser scanning microscope in the Integrated Microscopy Center at the University of Memphis.

GenBank accession number.

The previous GenBank entry (accession no. AFO86813) containing the partial sequence of spa has been updated to include the complete sequence.

RESULTS

DNA and amino acid sequences of Spa.

No homology was found between the spa18 sequence and current entries in the type 1 streptococcal genome sequence database (http://www.genome.ou.edu/strep.html). The predicted amino acid sequence of Spa demonstrates features similar to other streptococcal surface proteins, including a 37-residue signal peptide, an LPSTGE anchor motif (13), and a hydrophilic tail. The calculated molecular mass of the native protein is 58.9 kDa, and analysis of the secondary structure showed a high alpha-helical potential. Contrary to the amino acid sequence of other M-like proteins, Spa does not contain a proline-rich C terminus or internal tandem repeats.

A search of GenBank entries revealed considerable homology between Spa and the M protein of S. equi (Fig. 1). The homology is most apparent in the leader peptides and the C-terminal halves of the proteins. There is no significant sequence homology in the NH2-terminal halves of the mature proteins.

FIG. 1.

Alignment of the complete sequences of spa18 and the emm gene of S. equi. The arrow indicates the end of the leader peptide and the start of the mature protein, which was previously determined by amino acid sequence analysis (10). The LPSTGE motif is underlined. The GenBank accession number for the S. equi emm gene is U73162, and that for spa is AF086813.

Characterization of the Spa-negative mutants of strains 18-282 and M18Ω.

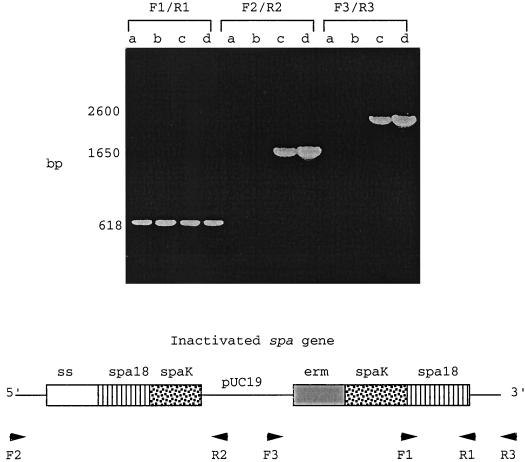

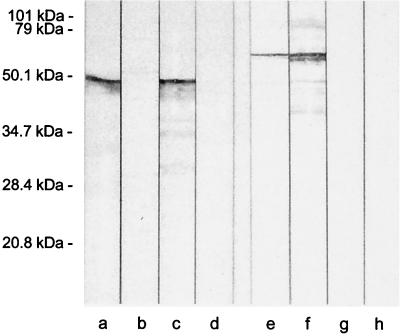

Inactivation of the spa gene in strain 18-282 and its M-negative mutant M18Ω was achieved by integrational plasmid mutagenesis using pUC19ermspa. Interruption of spa18 was confirmed by PCR analysis of chromosomal DNA obtained from the Spa-negative mutants created from 18-282 and M18Ω, designated 18Spa− and 18ΩSpa−. Three sets of primer pairs were used, with one primer in each pair annealing to pUC19 and the other primer in the pair annealing to spa18. Amplicons generated with 18Spa− and 18ΩSpa− DNA exhibited a size consistent with the proposed integration (Fig. 2). No amplification products were found with 18-282 or M18Ω. Southern blot analysis of PstI digested chromosomal DNA from 18Spa− and 18ΩSpa− with a digoxigenin-labeled probe of pUC19 detected a single copy of the insert (data not shown), indicating that integration occurred at a single site. To demonstrate that the spa18 gene was not expressed in strains 18Spa− and 18ΩSpa−, we carried out Western blot analyses (Fig. 3) using extracts of whole bacteria from those two strains as well as 18-282 and M18Ω and rabbit antisera against purified rM18 and rSpa. Anti-rM18 reacted with multiple proteins extracted from strains 18-282 and 18Spa−, the largest of which had a molecular mass of ∼50 kDa (Fig. 3, lanes a and c). The other reactive proteins seen on the immunoblot likely represent degradation products of M18 produced during the extraction process. There was no reaction of anti-rM18 with the extracts from M18Ω and M18ΩSpa− (lanes b and d). Anti-rSpa reacted with two closely related proteins extracted from 18-282 and M18Ω (lanes e and f). The largest of these two proteins had a molecular mass of ∼59 kDa, which is consistent with the mass of the native Spa protein predicted from the amino acid sequence. There was no reaction of anti-rSpa with the extracts from 18Spa− and 18ΩSpa− (lanes f and h). These results, taken together with the PCR and Southern blot analyses, indicate that the spa18 gene was insertionally inactivated in strains 18Spa− and 18ΩSpa−.

FIG. 2.

PCR analysis confirming insertional inactivation of spa by pUC19ermspa. Chromosomal DNA extracted from 18-282 (lane a), M18Ω (lane b), 18Spa− (lane c), and 18ΩSpa− (lane d) was subjected to PCR analysis. The annealing locations of primers F1, F2, F3, R1, R2, and R3 are shown (diagram is not to scale). Primer pair F1/R1 amplified a single product from the uninterrupted 3′ end of spa in all four strains. Primer pairs F2/R2 and F3/R3 annealed to both spa and pUC19, resulting in PCR products of appropriate size only with 18Spa− and 18ΩSpa−. ss, signal sequence; erm, erythromycin resistance gene.

FIG. 3.

Western blot analysis of stationary-phase whole cell extracts of 18-282 (lanes a and e), M18Ω (lanes b and f), 18Spa− (lanes c and g), and 18ΩSpa− (lanes d and h) reacted with antisera against rM18 (lanes a to d) and rSpa (lanes e to h).

Relative contributions of Spa and M18 in resistance to opsonization and phagocytosis.

To determine the role of Spa in resistance to phagocytosis, we performed in vitro opsonophagocytosis assays using 18-282, M18Ω, 18Spa−, and the double mutant 18ΩSpa− (Table 1). In nonimmune blood containing preimmune rabbit serum, the parent 18-282, M18Ω, and 18Spa− were equally resistant to phagocytosis, whereas the double mutant 18ΩSpa− was not resistant to phagocytosis. The organisms were also rotated in blood in the presence of either anti-rSpa or anti-rM18 to determine whether each strain was opsonized by the appropriate antiserum predicted by the phenotype. Parent strain 18-282 and mutant M18Ω were opsonized by anti-rSpa, while mutant 18Spa− was not (Table 1). Anti-rM18 opsonized only the parent and 18Spa− strains, not the M18Ω strain.

TABLE 1.

Association of 18-282, M18Ω, 18Spa−, and 18ΩSpa− with neutrophils and opsonization by anti-rSpa and anti-rM18

| Antiserum | % of neutrophils with associated streptococcia

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18-282 | M18Ω | 18Spa− | 18ΩSpa− | |

| Preimmune | 2 | 6 | 2 | 98 |

| Anti-rSpa | 96 | 98 | 0 | 94 |

| Anti-rM18 | 100 | 10 | 100 | 100 |

A standard inoculum of streptococci grown to early log phase were added to 0.05 ml of test antiserum and incubated for 15 min at 37°C; 0.2 ml of nonimmune, heparinized human blood was added and rotated end-over-end for 45 min at 37°C. Following rotation, smears were made on glass slides and stained with modified Wright's stain. The percentage of neutrophils associated with streptococci was calculated by counting 50 consecutive neutrophils. Assays were performed at least three different times, and the results presented are representative of all experiments.

These results were confirmed by quantitating the growth of the organisms after rotation in whole, human blood containing either preimmune or immune rabbit serum (Table 2). After a 3-h rotation, the parent strain grew to 9.1 generations, while the M18Ω and 18Spa− mutants grew to 8.8 and 7.4 generations, respectively. The double mutant grew to only 4.5 generations. Again the bactericidal effect of anti-rM18 or anti-rSpa was consistent with the surface phenotype expected for each strain (Table 2). Taken together, these results show that Spa and M18 contribute to the ability of type 18 streptococci to resist phagocytosis in human blood. In addition, antibodies against either of these surface proteins are opsonic and able to promote phagocytic killing. When both Spa and M18 are inactivated, the organisms grow considerably less well in nonimmune blood, demonstrating that both surface proteins play a role in survival in blood in vitro of type 18 streptococci.

TABLE 2.

Bactericidal activity of anti-rM18 and anti-rSpa against 18-282, M18Ω, and Spa-negative mutants

| Antiserum | CFU surviving 3-h rotationa

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18-282 [9] | M18Ω [10] | 18Spa− [14] | 18ΩSpa− [14] | |

| Preimmune | 5,280 (9.1) | 4,640 (8.8) | 2,500 (7.4) | 340 (4.5) |

| Anti-rM18 | 10 | 4,440 | 0 | 110 |

| Anti-rSpa | 700 | 0 | 2,320 | 140 |

Indirect bactericidal assays were performed by adding a standard inoculum of streptococci to 0.1 ml of test antiserum and incubating the mixture for 15 min at 37°C; 0.35 ml of whole, heparinized, nonimmune human blood was then added and rotated end-over-end for 3 h. Aliquots of 0.1 ml were then added to melted sheep's blood agar, and pour plates were prepared. Viable organisms were quantitated after overnight incubation at 37°C. Numbers in brackets are inocula (CFU); number in parentheses are generations of growth following the 3-h rotation. The experiment was performed three times with similar results. The data presented are from one representative experiment.

Mouse virulence studies.

To further define the role of Spa as a virulence determinant, mouse virulence studies were performed by determining the LD50 following intraperitoneal injection of 10-fold-increasing inocula of each strain. The LD50 of 18-282 was 2.8 × 105, that of M18Ω was 1.1 × 106, that of M18Spa− was 4.4 × 106, and that of M18ΩSpa− was 1.1 × 107. Organisms were recovered from the spleens of mice that did not survive the challenge infection. M18Ω retained its resistance to kanamycin, the selective marker associated with insertional inactivation of the emm 18 gene (10), while 18Spa− remained resistant to erythromycin and 18ΩSpa− continued to be resistant to both antibiotics. This demonstrated that the mutant phenotypes were stable in vivo. These results, taken together with those of the opsonization and bactericidal assays, indicate that the expression of Spa contributes to the virulence of type 18 streptococci.

C3 binding to the surface of the M18 parent and mutant strains.

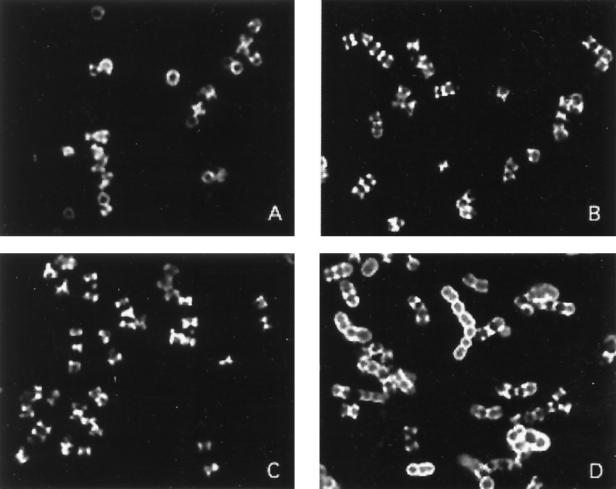

Indirect immunofluorescence assays were performed to assess the patterns of C3 deposition on the M18 parent and the M18-negative and Spa-negative mutants (Fig. 4). As shown in a previous study (11), the parent strain 18-282 incubated in nonimmune human plasma bound C3 mostly in a linear pattern (Fig. 4A), suggesting that the complement was binding to new cross walls. The M-negative (Fig. 4B) and Spa-negative (Fig. 4C) mutants similarly bound C3 as linear deposits. C3 deposition on the double mutant, however, was observed mostly in a circumferential pattern (Fig. 4D). Identical results were obtained when the bacterial strains were incubated in nonimmune human serum (data not shown). These data, taken together with the results of in vitro phagocytosis assays, indicate that both Spa and M protein confer upon type 18 streptococci the ability to resist opsonization by complement in nonimmune blood.

FIG. 4.

Immunofluorescence analysis of C3 binding to 18-282 (A), M18Ω (B), 18Spa− (C), and M18ΩSpa− (D) after incubation of each strain grown to early log phase in nonimmune human plasma.

Human immune response to Spa.

The human immune response to Spa was assessed using sera from patients known to have an antecedent streptococcal infection based on a documented history of acute rheumatic fever (Table 3). ELISAs were performed using a recombinant 212-residue NH2-terminal fragment as the solid-phase antigen. Of the 20 different sera examined, 10 demonstrated measurable levels of antibody directed against Spa. Antibodies against various recombinant N-terminal M protein fragments were assayed in parallel, and there was no obvious correlation between the presence of Spa antibodies and antibodies against particular type-specific M peptides (Table 3).

Tissue cross-reactivity of anti-rSpa.

Studies have shown that several streptococcal antigens, including M protein, contain epitopes that evoke antibodies that cross-react with myocardium (8), renal glomeruli (15), cartilage (1), and brain (3). To assess whether anti-rSpa cross-reacted with human tissues, indirect immunofluorescence assays were performed on frozen sections of human myocardium, kidney, basal ganglia, and cerebral cortex. None of these assays demonstrated evidence of cross-reactivity between anti-rSpa and human tissues.

DISCUSSION

The central role of M protein in the pathogenesis of GAS infection is well established. In most cases, bacteria expressing M protein are able to resist opsonization and phagocytosis when incubated in nonimmune blood, while M-negative strains are readily killed (16). Several groups have investigated the properties of M protein that confer resistance to phagocytosis. These properties include the ability of M proteins to bind plasma fibrinogen, which coats the bacterial surface and blocks activation of the alternate complement pathway (25). In addition, M protein and fibrinogen bind factor H, a potent regulator of the complement cascade, which prevents the generation of C3b (12).

The ability to confer resistance to phagocytosis has become part of the functional definition of an M protein. However, recent studies have demonstrated that GAS have evolved other antiphagocytic properties that vary from one serotype to another and augment the ability of the bacteria to evade the host immune response. These other determinants of resistance to phagocytosis include surface proteins encoded by the mrp and enn genes that bind IgG and IgA, which may mask the surface of the organism and prevent nonspecific immune recognition (17). Studies in which both the mrp and emm genes were insertionally inactivated clearly demonstrated that the expression of both proteins contributes to resistance to phagocytosis (21). All group A streptococci also express C5a peptidase, which specifically inactivates the potent chemoattractant C5a and reduces the influx of polymorphonuclear leukocytes (6). The gene encoding for C5a peptidase (scpA) as well as emm, mrp, and enn are all members of a genomic regulon under the influence of the upstream positive regulator mga (5). Another important virulence factor is the hyaluronate capsule, which for some serotypes appears to be the major determinant of resistance to phagocytosis (11, 18).

In studies comparing the mechanisms of resistance to phagocytosis of type 24 and type 18 streptococci, it was clearly shown that the type 24 organisms were almost completely dependent on M protein expression and its binding of fibrinogen for growth in blood, while type 18 streptococci bound fibrinogen in much lower quantities and were more dependent on capsule expression for complete resistance to phagocytosis (11). The role of M protein in type 18 streptococcal infections was further examined in experiments where the emm18 gene was insertionally inactivated, rendering the resultant mutant, M18Ω, phenotypically M protein negative (10). Interestingly, the parent strain and the M18Ω mutant were equally resistant to phagocytic killing in nonimmune blood, and both strains demonstrated comparable virulence in mice after intraperitoneal challenge infections. Treatment of the organisms with hyaluronidase to remove the capsule resulted in a significant but incomplete reduction in growth of both organisms in whole blood. Thus, type 18 streptococci express a virulence determinant in addition to M protein and hyaluronate capsule.

In this study, we have shown that the presence of Spa on the surface of type 18 streptococci contributes to virulence and resistance to opsonophagocytosis. This was achieved by insertionally inactivating the native spa gene in both the parent M18 and mutant M18Ω strains. The expression of M protein and/or Spa was associated with an antiphagocytic phenotype, while the double mutant lacking both determinants was readily phagocytosed. Patterns of C3 opsonization of each strain were consistent with the results of phagocytosis assays, indicating that M protein and Spa both prevent deposition of C3 on the mature cell wall in either nonimmune human plasma or serum. The results of the phagocytosis and opsonization assays were confirmed by showing that the double mutant grew less well in nonimmune blood and demonstrated reduced virulence in a mouse model of infection compared to that of the parent or the single mutant expressing either M protein or Spa. Interestingly, the double mutant was not totally avirulent in mice, suggesting that the capsule may play an important role for this strain in this animal model (18). Since all of the mutants used in this study expressed capsules of similar size, as determined by India ink preparations (unpublished data), the hyaluronate capsule may have contributed to the resistance to phagocytosis that was observed.

Spa fulfills the functional definition of an M protein in that it is both a virulence determinant and protective antigen. Structurally it shares some features with M proteins, including a signal peptide, a conserved gram-positive cell wall spanning sequence with an LPSTGE motif, and a predicted alpha-helical conformation throughout most of its length. Unlike M protein, however, Spa does not contain a proline rich C terminus or internal tandem repeats. The similarity between spa and the emm gene of S. equi was a very interesting finding. This group C streptococcus is an equine pathogen that causes a highly contagious upper respiratory tract infection known as strangles. The emm gene of S. equi encodes an M-like protein that is both a major virulence determinant and protective antigen of the organism (24). Although the C-terminal half of Spa is almost identical to the same region of the S. equi M protein, it is important to note that there is little similarity between the NH2-terminal halves of the mature proteins. This invites the speculation that the spa gene could have been acquired from S. equi (or vice versa) and has evolved under immunological and other environmental pressures into a unique surface protein. Alternatively, the ancestral gene may have been acquired by S. equi and group A streptococci from another organism and mutations or recombination occurred under the influence of different environmental pressures.

A critical question to address regarding the potential suitability of Spa as a vaccine candidate is its immunogenic potential and cross-reactivities. In this study, high-titer antibodies were generated in rabbits against a recombinant peptide copying the NH2-terminal half of Spa. In addition, this recombinant peptide was used as a solid-phase antigen to screen patients with a documented history of acute rheumatic fever by ELISA. Spa antibodies were detected in a significant number of human sera tested, indicating that the protein is expressed during infection and is immunogenic. Importantly, antibodies against the recombinant NH2-terminal half of Spa do not cross-react with human tissues. Since our previous studies have shown that antibodies against this fragment of Spa opsonize some heterologous serotypes of group A streptococci (10), studies are in progress to determine which serotypes may express conserved epitopes of this potentially important surface antigen.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant AI-10085 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (J.B.D.), Merit Review funds from the Department of Veterans Affairs (J.B.D., D.L.H., and H.S.C.), and research funds from ID Biomedical Corporation.

We appreciate the expert technical assistance of Sharon Frase, University of Memphis Integrated Microscopy Center, in obtaining images of C3 binding to streptococci using the confocal laser scanning microscope.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baird R W, Bronze M S, Kraus W, Hill H R, Veasey L G, Dale J B. Epitopes of group A streptococcal M protein shared with antigens of articular cartilage and synovium. J Immunol. 1991;146:3132–3137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beachey E H, Stollerman G H, Chiang E Y, Chiang T M, Seyer J M, Kang A H. Purification and properties of M protein extracted from group A streptococci with pepsin: covalent structure of the amino terminal region of the type 24 M antigen. J Exp Med. 1977;145:1469–1483. doi: 10.1084/jem.145.6.1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bronze M S, Dale J B. Epitopes of streptococcal M proteins that evoke antibodies that cross-react with human brain. J Immunol. 1993;151:2820–2828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caparon M G, Scott J R. Genetic manipulation of pathogenic streptococci. Methods Enzymol. 1991;204:556–586. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(91)04028-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Caparon M G, Scott J R. Identification of a gene that regulates expression of M protein, the major virulence determinant of group A streptococci. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:8677–8681. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.23.8677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cleary P P, Prahbu U, Dale J B, Wexler D E, Handley J. Streptococcal C5a peptidase is a highly specific endopeptidase. Infect Immun. 1992;60:5219–5223. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.12.5219-5223.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Courtney H S, Bronze M S, Dale J B, Hasty D L. Analysis of the role of M24 protein in streptococcal adhesion and colonization by use of omega-interposon mutagenesis. Infect Immun. 1994;62:4868–4873. doi: 10.1128/iai.62.11.4868-4873.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dale J B, Beachey E H. Epitopes of streptococcal M proteins shared with cardiac myosin. J Exp Med. 1985;162:583–591. doi: 10.1084/jem.162.2.583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dale J B, Beachey E H. Multiple heart-cross-reactive epitopes of streptococcal M proteins. J Exp Med. 1985;161:113–122. doi: 10.1084/jem.161.1.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dale J B, Chiang E Y, Liu S Y, Courtney H S, Hasty D L. New protective antigen of group A streptococci. J Clin Investig. 1999;103:1261–1268. doi: 10.1172/JCI5118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dale J B, Washburn R G, Marques M B, Wessels M R. Hyaluronate capsule and surface M protein in resistance to phagocytosis of group A streptococci. Infect Immun. 1996;64:1495–1501. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.5.1495-1501.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fischetti V A, Horstman R D, Pancholi V. Location of the complement factor H binding site on streptococcal M protein. Infect Immun. 1995;63:149–153. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.1.149-153.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fischetti V A, Pancholi V, Schneewind O. Conservation of a hexapeptide sequence in the anchor region of surface proteins of gram-positive cocci. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1603–1605. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb02072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jacks-Weis J, Kim Y, Cleary P P. Restricted deposition of C3 on M+ group A streptococci: correlation with resistance to phagocytosis. J Immunol. 1982;128:1897–1902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kraus W, Beachey E H. Renal autoimmune epitope of group A streptococci specified by M protein tetrapeptide Ile-Arg-Leu-Arg. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:4516–4520. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.12.4516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lancefield R C. Current knowledge of the type specific M antigens of group A streptococci. J Immunol. 1962;89:307–313. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindahl G, Stenberg L. Binding of IgA and/or IgG is a common property among clinical isolates of group A streptococci. Epidemiol Infect. 1990;105:87–93. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800047683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moses A E, Wessels M R, Zalcman K, Alberti S, Natanson-Yaron S, Menes T, Hanski E. Relative contributions of hyaluronic acid capsule and M protein to virulence in a mucoid strain of the group A Streptococcus. Infect Immun. 1997;65:64–71. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.1.64-71.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Perez-Casal J, Caparon M G, Scott J R. Introduction of the emm6 gene into an emm-deleted strain of Streptococcus pyogenes restores its ability to resist phagocytosis. Res Microbiol. 1992;143:549–558. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(92)90112-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Podbielski A, Peterson J A, Cleary P. Surface protein-CAT reporter fusions demonstrate differential gene expression in the vir regulon of Streptococcus pyogenes. Mol Microbiol. 1992;6:2253–2265. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1992.tb01401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Podbielski A, Schnitzler N, Beyhs P, Boyle M D P. M-related protein (Mrp) contributes to group A streptococcal resistance to phagocytosis by human granulocytes. Mol Microbiol. 1996;19:429–441. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.377910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reed L J, Muench H. A single method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am J Hyg. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevens D L. The flesh-eating bacterium: what's next? J Infect Dis. 1999;179(Suppl. 2):S366–S374. doi: 10.1086/513851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Timoney J F, Artiushin S C, Boschwitz J S. Comparison of the sequences and functions of Streptococcus equi M-like proteins SeM and SzPSe. Infect Immun. 1997;65:3600–3605. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.9.3600-3605.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Whitnack E, Beachey E H. Antiopsonic activity of fibrinogen bound to M protein on the surface of group A streptococci. J Clin Investig. 1982;69:1042–1048. doi: 10.1172/JCI110508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]