Abstract

Sepsis is a major health issue with mortality exceeding 30% and few treatment options. We found that high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) abundance was reduced by 45% in septic patients compared to that in nonseptic patients. Furthermore, HDL-C abundance in nonsurviving septic patients was substantially lower than in those patients who survived. We therefore hypothesized that replenishing HDL might be a therapeutic approach for treating sepsis and found that supplementing HDL with synthetic HDL (sHDL) provided protection against sepsis in mice. In mice subjected to cecal ligation and puncture (CLP), infusing the sHDL ETC-642 increased plasma HDL-C amounts and improved the 7-day survival rate. Septic mice treated with sHDL showed improved kidney function and reduced inflammation, as indicated by marked decreases in the plasma concentrations of blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and the cytokines interleukin-6 (IL-6) and IL-10, respectively. We found that sHDL inhibited the ability of the endotoxins LPS and LPA to activate inflammatory pathways in RAW264.7 cells and HEK-Blue cells expressing the receptors TLR4 or TLR2 and NF-κB reporters. In addition, sHDL inhibited the activation of HUVECs by LPS, LTA, and TNF-α. Together, these data indicate that sHDL treatment protects mice from sepsis in multiple ways and that it might be an effective therapy for patients with sepsis.

INTRODUCTION

Sepsis is a major health issue with a mortality rate exceeding 30% (1). So far, therapeutic interventions focused on blocking specific components of the inflammatory or coagulation pathways have had little effect on patient survival. Given that multiple factors contribute to sepsis pathogenesis, we propose that targeting an endogenous factor with multiprotective effects may present a novel approach for sepsis therapy.

Exogenous high-density lipoprotein (HDL) or its synthetic analogs are potential candidates for sepsis treatment. First, endogenous HDL has a broad spectrum of activity highly pertinent to combating sepsis, including neutralization of endotoxin (2-4), suppression of inflammatory signaling in immune effector cells (5, 6), and inhibition of endothelial cell (EC) activation (7). Second, HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) abundance is markedly reduced in septic patients and correlates with a poor prognosis (8, 9). Third and consistent with clinical evidence, we previously showed that HDL deficiency increases susceptibility to cecal ligation and puncture (CLP)–induced septic death in experiments with apolipoprotein A-I (ApoA-I)–null mice as an HDL-deficient model (10). Furthermore, increasing HDL abundance by overexpressing ApoA-I improves survival in mice after CLP (10). On the basis of these clinical and experimental findings, we hypothesized that a decrease in HDL abundance is a risk factor for sepsis mortality and that increasing circulating HDL amounts may present an effective sepsis therapy (11).

To test our hypothesis, we used a new generation of synthetic HDL (sHDL), ETC-642, which consists of a 22–amino acid ApoA-I mimetic peptide (ESP24218 or 22A) and phospholipids. ETC-642 was previously developed for the treatment of cardiovascular disease (12) and, specifically, was optimized to effectively remove and eliminate excess cholesterol from atheromas. ETC-642 presents an advantageous opportunity for the rapid translation of this therapeutic as an acute sepsis treatment. Unlike other investigational therapies, ETC-642 is safe at large doses (1 to 30 mg/kg) and is capable of increasing circulating HDL-C abundance in patients in several single- and multiple-dose clinical trials (13, 14). With established manufacturing, completed toxicology evaluation, and available clinical safety data, ETC-642 could progress to clinical evaluation in patients with septic shock. In addition, the use of synthetic peptides and lipids circumvents toxicity-related concerns associated with reconstituted HDLs (rHDLs) made from human plasma-purified ApoA-I due to residual endotoxin and other host-related impurities. Moreover, generating peptide-based sHDL eliminates the demand for the massive quantities of human plasma required to produce rHDL in large scale.

In this study, we demonstrated that the administration of sHDL after the onset of CLP-induced sepsis both increased effective HDL-C concentrations and was protective against septic death. We further demonstrated that, in contrast to earlier approaches that block the inflammatory pathway or simply neutralize lipopolysaccharide (LPS), sHDL therapy provided multiple protective mechanisms through promoting the detoxification of LPS and lipoteichoic acid (LTA), suppressing inflammatory signaling in macrophage-like cells, and inhibiting the activation of ECs. Together, our findings support the further development of sHDL therapy for the effective treatment of sepsis.

RESULTS

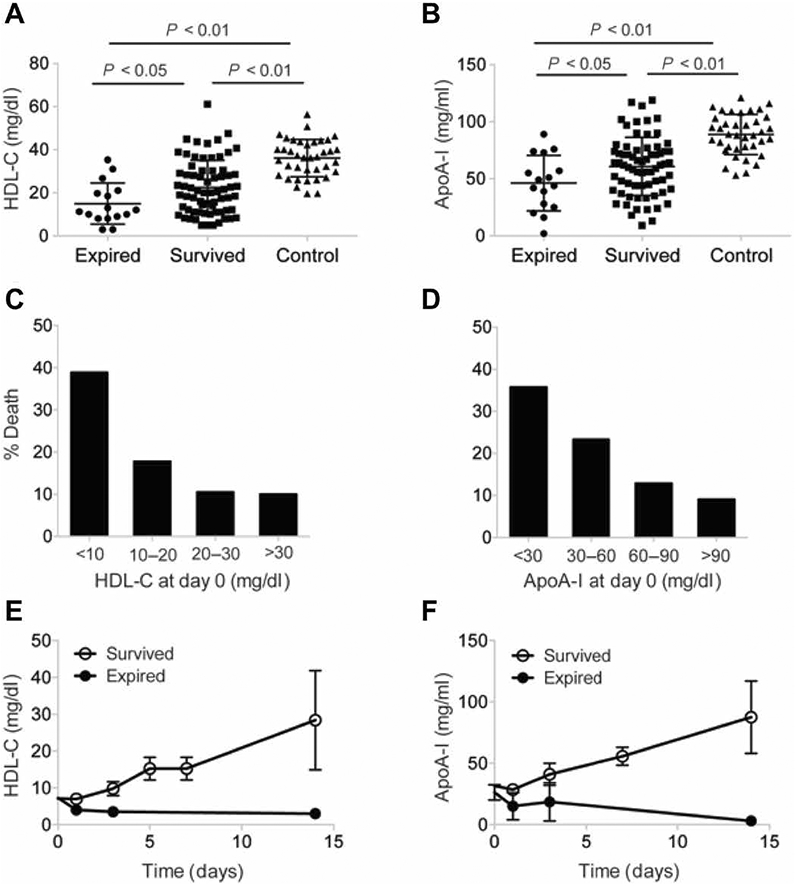

HDL abundance is reduced in septic patients

To better understand the role of HDL in sepsis, a clinical observational study was conducted in 123 patients admitted to the University of Michigan Hospital Intensive Care Unit (ICU). For analysis, patients were divided into three groups: nonsepsis controls (n = 38), sepsis survivors (n = 69), and patients who had not survived sepsis (n = 16, also termed “sepsis expired”). Plasma HDL-C amounts at the time of admission to the ICU (day 0) and for the duration of ICU stay were measured (Fig. 1A). We found that HDL-C amounts were markedly lower in patients with sepsis than in nonsepsis controls on day 0, with sepsis-expired individuals having significantly reduced amounts of HDL-C (15 ± 10 mg/dl) than those of both sepsis survivors (23 ± 13 mg/dl; P < 0.05) and nonsepsis controls (36 ± 9 mg/dl; P < 0.01). A similar trend was observed for ApoA-I amounts (Fig. 1B), which also differed significantly between sepsis-expired (46 ± 25 mg/ml), sepsis survivors (61 ± 26 mg/ml; P < 0.05), and nonsepsis controls (89 ± 18 mg/ml; P < 0.01). Because ApoA-I abundance is an indirect measure of both HDL function and the number of circulating HDL particles, we hypothesized that a decrease in ApoA-I abundance would confer a temporary loss in the anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, and antithrombotic functions of HDL and that this might contribute to the vascular dysfunction observed in patients with sepsis.

Fig. 1. Septic patients have less HDL compared to nonseptic patients, which is associated with poor survival.

(A to F) Patients admitted to the University of Michigan Hospital ICU were divided into three groups: nonsepsis controls (n = 38), sepsis survivors (n = 69), and patients who had not survived sepsis (n = 16, also termed sepsis expired). Plasma HDL-C (A) and ApoA-I (B) amounts at the time of admission to the ICU (day 0) and for the duration of the ICU stay were measured. (C and D) Incidence of death in patients with different amounts of HDL-C (C) and ApoA-I (D). (E and F) Changes in HDL-C (E) and ApoA-I (F) amounts in expired and survived sepsis patients during the ICU stay. Statistical significance was determined by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

Low HDL abundance correlates with a poor prognosis

Given the marked alterations in HDL-C and ApoA-I amounts observed in septic patients, we next sought to explore the relationship between HDL-C and survival among septic patients. We found that patients entering the ICU with a plasma HDL-C concentration of <10 mg/dl had about a twofold increase in mortality compared to those with an HDL-C concentration of >10 mg/dl (Fig. 1C), suggesting that decreased HDL-C abundance may be a predictive factor for sepsis-related mortality. The amounts of ApoA-I also correlated with survival (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, among the patients with HDL-C concentrations of <10 mg/dl, the amounts of ApoA-I and HDL-C remained low until death, whereas they gradually increased in the patients who recovered (Fig. 1, E and F), suggesting that restoring the amounts of HDL-C and ApoA-I may have a protective effect in sepsis. Together, these data support the notion that HDL administration might increase patient survival by restoring depleted endogenous HDL and its essential functions.

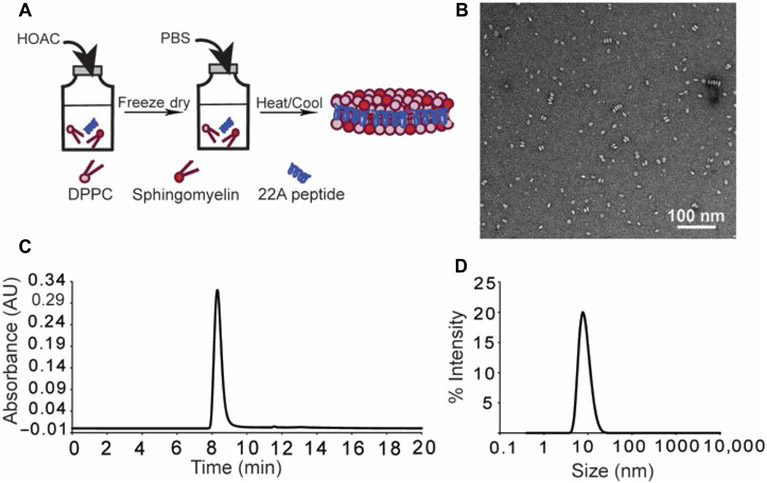

sHDL preparation results in pure and homogenous peptide-lipid nanodiscs

On the basis of the clinical correlation between increased HDL-C and ApoA-I concentrations and greater survival, we tested the ability of infused sHDL to improve survival in a CLP model. We used ETC-642, a peptide-based, sHDL product with well-documented human safety and established clinical manufacturing. ETC-642 was prepared by a colyophilization technique (Fig. 2A) with the 22–amino acid ApoA-I mimetic peptide (22A), 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC), and sphingomyelin (SM) (15-17). We produced homogeneous sHDL nanoparticles as seen by transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (Fig. 2B), whose purity was >99% as evidenced by gel permeation chromatography (GPC) (Fig. 2C) and which had a size range of 10.4 ± 3.3 nm with low polydispersity [PDI (polydispersity index) = 0.1] as measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) (Fig. 2D).

Fig. 2. sHDL preparation and characterization.

(A) Schematic of the sHDL preparation procedure. (B) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) imaging of nanosized, discoidal sHDL particles. (C) Gel permeation chromatography (GPC) analysis of the purity sHDL particles. Purity was >99%. (D) Dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis of the size distribution of sHDL particles (10.4 ± 3.3 nm) with a PDI of 0.1.

sHDL restores HDL abundance and protects against CLP-induced death in mice

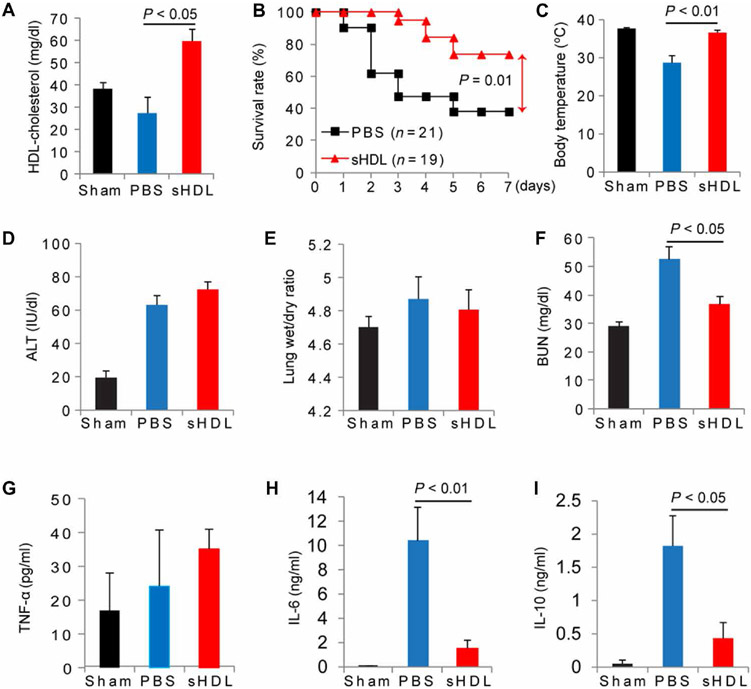

We next set out to test our central hypothesis that infusion of sHDL could restore HDL-C abundance and HDL function and improve survival in septic mice. C57BL/6 mice subjected to CLP (21-gauge needle, 2/3 ligation) were administered sHDL (7.5 mg/kg) or saline 2 hours after CLP was performed and were monitored for survival for 7 days. As expected, the HDL-C concentrations in mice treated with sHDL were significantly increased (59.2 ± 5.3 mg/dl) compared to those in saline-treated controls (26.5 ± 7.1 mg/dl; P < 0.05) 18 hours after CLP (Fig. 3A), showing the ability of sHDL to efflux cholesterol in vivo and restore endogenous amounts of HDL-C. Furthermore, sHDL (n = 21) improved the 7-day survival rate nearly twofold (P < 0.01) compared to that of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)–treated controls (n = 19) (Fig. 3B). We also found that sHDL moderately improved survival rates in mice when they were treated 6 hours after CLP (fig. S1).

Fig. 3. sHDL protects mice from CLP-induced death and attenuates CLP-induced organ injury and inflammatory cytokine production.

(A to I) B6 mice were subjected to CLP (with a 21-gauge needle, 2/3 ligation) or a sham procedure as a control. Two hours after CLP, the mice were treated intravenously with 100 μl of PBS or sHDL (7.5 mg protein/kg body weight). Plasma and lung samples were collected 18 hours after CLP was performed, and HDL was prepared by sequential ultracentrifugation. Plasma (1.5 ml) from five mice was used to make a single HDL preparation. (A) Analysis of HDL-C concentrations in the indicated mice (plasma was collected from 15 mice in each group). (B) Analysis of the 7-day survival rates of the indicated mice (n = 19 to 21). Survival was analyzed by the log-rank test and Kaplan-Meier plots. (C) Analysis of body temperature in the indicated mice at 16 hours after CLP (n = 7 or 8 per group). The extent of CLP-induced organ injury was determined by quantifying the plasma ALT concentration (D), the lung wet/dry ratio (E), and the plasma BUN concentration (F). The plasma concentrations of the cytokines TNF-α (G), IL-6 (H), and IL-10 (I) were quantified with ELISA (n = 6, 15, and 16 for sham-, PBS-, and CLP-treated mice, respectively). Data are means ± SEM and were analyzed by one-way ANOVA.

sHDL attenuates CLP-induced organ injury and suppresses inflammatory cytokine production

To better understand the extent of sHDL-mediated protection in sepsis, we monitored several physiological factors common to the disease, including decreased body temperature, increased organ damage, and increased plasma cytokine concentrations 18 hours after CLP. sHDL therapy restored normal body temperature 16 hours after treatment to 36.6 ± 1.5°C (n = 8) compared to that of PBS-treated mice (n = 7), whose body temperature remained low at 28.7 ± 0.7°C (P < 0.01) (Fig. 3C). In addition, we assessed organ injury of the liver [by measuring alanine transaminase (ALT) abundance], the lungs (by measuring the lung wet/dry ratio), and the kidneys [by measuring blood urea nitrogen (BUN)] (Fig. 3, D to F). No differences in ALT or lung wet/dry ratios were observed. However, sHDL administration significantly protected kidney function (P < 0.05), as indicated by a reduction in BUN abundance in sHDL-treated (36.62 ± 2.82 mg/dl; n = 16) mice as compared to that in PBS-treated controls (52.63 ± 4.51 mg/dl; n = 15). Cytokine concentrations in the plasma were measured, and although sHDL did not reduce the circulating concentrations of tumor necrosis factor–α (TNF-α; Fig. 3G) or interleukin-1β (IL-1β; fig. S2), it reduced the plasma concentrations of both IL-6 (0.964 ± 0.296 ng/ml for the sHDL group versus 9.364 ± 3.637 ng/ml for the PBS group; P < 0.01) (Fig. 3H) and IL-10 levels (0.432 ± 0.235 ng/ml for the sHDL group versus 1.182 ± 0.450 ng/ml for the PBS group; P < 0.05) (Fig. 3I). We found that sHDL had no effect on bacterial load (fig. S3).

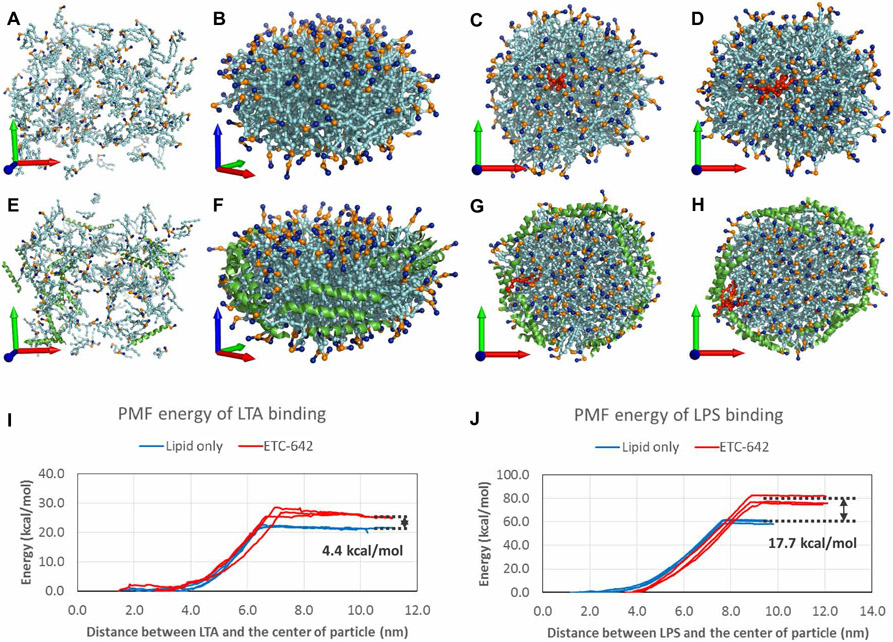

Modeling of the binding of sHDL to endotoxins

Although our in vivo results suggest that sHDL is effective in protecting against sepsis, the lack of a clear mechanism warranted additional in vitro studies. Although the ability of both liposomes and HDL to bind to and neutralize LPS is known (3, 18), we questioned whether sHDL had a higher affinity than liposomes for LPS, and whether this was also true for LTA, a cell wall component of Gram-positive bacteria. The energetics of LPS and LTA binding were estimated computationally through coarse-grained (CG) molecular dynamics simulation using both the lipid-only (Fig. 4, A to D) and self-assembled (Fig. 4, E and F) sHDL nanoparticles. These simulations suggest that the sHDL peptides are arranged in parallel around the edge of lipid bilayer (Fig. 4, F to H), similar to the parallel alignment of ApoA-I proteins in the double-belt model of native HDL. The calculated potential of mean force (PMF) energies showed that sHDL assembled particles efficiently bind to both LTA and LPS with binding free energies of around 30 and 80 kcal/mol, respectively. We also showed that assembled sHDL nanoparticles had higher affinity for LTA and LPS relative to that for lipid alone by 4.4 (Fig. 4I) and 17.7 kcal/mol (Fig. 4J), respectively. We also directly measured the binding enthalpies of LPS to sHDL and phospholipids by isothermal titration calorimetry to be −39.94 and −23.63 kcal/mol, indicating stronger binding of LPS to the sHDL nanoparticle than to its lipid-only equivalent (table S2).

Fig. 4. Modeling of the binding of sHDL to endotoxins.

(A) The initial state of the lipid-only particle. All of the lipids (cyan) are randomly distributed. The positively charged choline head and the negatively charged phosphoric acid groups are colored in blue and gold, respectively. The x, y, and z axes of the coordination system are showed by red, green, and blue arrows, respectively. (B) The final state of the lipid-only particle: its self-assembly to a discoid nanodisc in a 3-μs simulation. The hydrophilic surface of the nanodisc is aligned with the xy plane. (C and D) The proposed positions of insertion of LTA (C) and LPS (D) into the lipid-only particle are shown in a ball-and-stick style and colored in red. (E) The initial state of the sHDL particle. The 22A peptides are shown in cartoon style and colored in green. (F) The sHDL particle also forms a nanodisc with all of the peptides arranged around the lipid. (G and H) The LTA (G) and LPS (H) molecules can also be inserted into the sHDL particle; however, they favorably localize near the 22A peptides. (I and J) The PMF-calculated binding free energies of the binding of (I) LTA and (J) LPS with the lipid-only (blue) or sHDL particles (red).

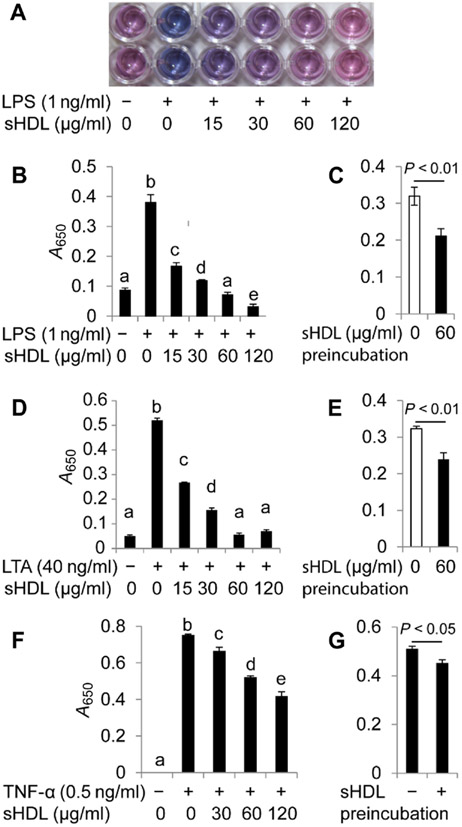

sHDL suppresses LPS/LTA/TNF-α–induced NF-κB activation

Next, we investigated the mechanism underlying the anti-inflammatory effect of sHDL. To do this, we used HEK-Blue cells that were stably transfected to express either human Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), TLR2, or the TNF-α receptor and a nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) reporter. Cells were challenged with the corresponding receptor ligands (LPS for TLR4, LTA for TLR2, or TNF-α) in the presence or absence of various concentrations of sHDL (Fig. 5, A to G). In all cases, we observed a dose-dependent decrease in NF-κB activation with increasing sHDL concentrations, with maximal sHDL treatments inhibiting NF-κB activation by about 95% (Fig. 5B), 85% (Fig. 5D), and 50% (Fig. 5F) for the LPS:TLR4, LTA:TLR2, and TNF-α models, respectively. We also compared the LPS-neutralizing capacity of sHDL to that of the clinically available therapy, polymyxin B, by measuring TNF-α concentrations in the culture medium of cells challenged with LPS and treated with different concentrations of sHDL or polymyxin B (fig. S4). Although polymyxin B completely inhibited TNF-α release at all of the concentrations used, its unfavorable safety profile with severe nephrotoxicity and neurotoxicity limits its clinical application. On the other hand, sHDL has favorable documented safety in humans (19).

Fig. 5. sHDL suppresses the LPS-, LTA-, and TNF-α–induced activation of NF-κB.

(A to G) HEK-Blue cells expressing TLR4, TLR2, or TNF receptor were cultured to 70% confluency and treated with LPS (A and B), LTA (D), or TNF-α (F) in the presence of sHDL for 16 hours. Alternatively, the cells were pretreated with sHDL (60 μg/ml) for 6 hours and then stimulated with the corresponding ligands (C, E, and G). Samples (100 μl) of the cell culture medium were mixed with 100 μl of HEK-Blue. Detection and the activation of the NF-κB reporter were quantified by measuring absorption at 650 nm (A650). Data are from three independent experiments and were analyzed by one-way ANOVA (B, D, and F) or Student’s t test (C, E, and G). Significant differences with P < 0.05 (B, D, and F) are denoted by different letters (that is, bars with different letters denote significant differences, whereas bars with the same letter are not statistically different).

Although the LPS-binding capability of HDL was previously described (3, 18), other studies suggest that HDL may also exert various anti-inflammatory properties through cellular signaling pathways (17, 20, 21). To assess whether the observed inhibition of inflammation was solely due to endotoxin binding, neutralization, or both, we performed a series of experiments in which we pretreated TLR4- and TLR2-expressing HEK-Blue cells with sHDL (60 μg/ml) for 6 hours and then challenged the cells with the appropriate ligands in the absence of sHDL. Although the extent of NF-κB inhibition was less than that of cells challenged in the presence of sHDL, pretreatment with sHDL still reduced NF-κB activation by >30% in the LPS:TLR4 model (P < 0.01; Fig. 5C), >25% in the LTA:TLR2 model (P < 0.01; Fig. 5E), and >10% in the TNF-α model (P < 0.05; Fig. 5G). This suggests that the physical binding of LPS, LTA, and TNF-α by sHDL is not the only mechanism by which sHDL exerts protection in sepsis or inflammation.

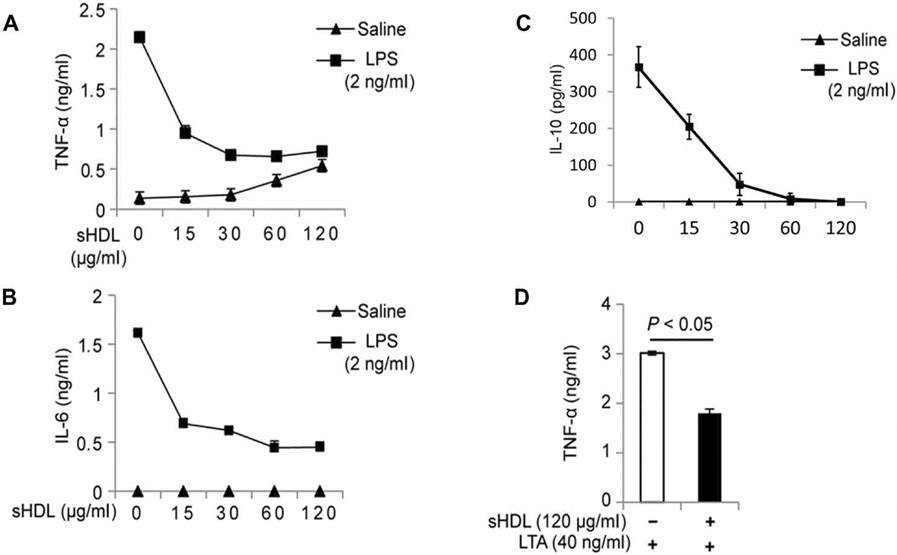

sHDL suppresses LPS- and LTA-induced cytokine production by RAW264.7 cells

Whereas it was evident that sHDL conferred protection against TLR4- and TLR2-induced NF-κB activation in human embryonic kidney (HEK) cells, we wanted to confirm that this inhibition was also applicable in macrophages, the major immune cells involved in the onset and progression of sepsis. Here, we used the secretion of the cytokines TNF-α and IL-6 into the cell culture medium as our end point. In RAW264.7 cells (a mouse monocyte/macrophage cell line) challenged with LPS (2 ng/ml), coincubation with sHDL resulted in greater than twofold reduction in both TNF-α (Fig. 6A) and IL-6 (Fig. 6B) production compared to that by PBS-treated controls (P < 0.01). In cells challenged with LTA (40 ng/ml), incubation in the presence of sHDL (120 μg/ml) reduced TNF-α production by >50% (P < 0.05; Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6. sHDL suppresses LPS- and LTA-induced cytokine production by RAW264.7 cells.

(A to D) RAW264.7 cells were cultured to 70% confluency and treated with the indicated concentrations of LPS (A to C) or LTA (D) in the presence of the indicated concentrations of sHDL for 16 hours. As a negative control for LPS and LTA, cells were treated with saline. The concentrations of TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10 that were secreted by the cells into the culture medium were measured by ELISA. Data are means ± SD of three independent experiments.

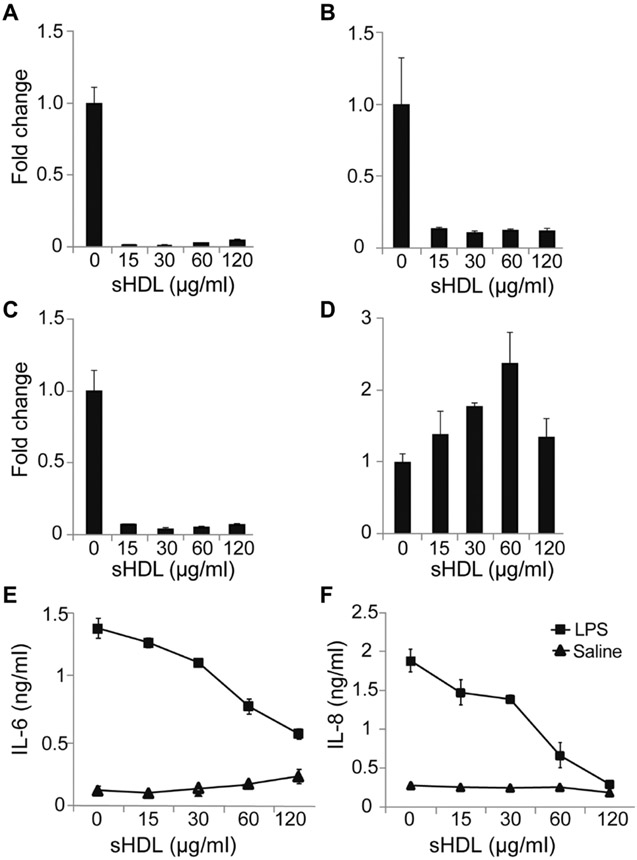

sHDL suppresses the LPS-induced activation of HUVECs

In addition to macrophages, sepsis also manifests as a disorder of the endothelium (11, 21-23). We hypothesized that the decrease in HDL-C and ApoA-I concentrations observed in septic patients is a major contributor to vascular dysfunction. Thus, we next assessed the effect of sHDL on protection against EC activation in vitro. Characteristic inflammatory markers in ECs include the expression of cell adhesion molecules, a reduction in endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) abundance, and the induction of proinflammatory cytokine release. Here, we used human umbilical vein ECs (HUVECs) activated with LPS (1 μg/ml) as our cell model and examined the ability of sHDL to reduce the abundances of mRNAs encoding the cell adhesion molecules vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1), intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), and E-selectin; to increase NOS3 mRNA abundance; and decrease the production of IL-6 and IL-8. As expected, the amounts of mRNAs encoding ICAM-1 (Fig. 7A), VCAM-1 (Fig. 7B), and E-selectin (Fig. 7C) were reduced >10-fold in HUVECs challenged with LPS in the presence of sHDL compared to those in HUVECs treated with LPS (P < 0.01). In addition, sHDL at concentrations of 30 and 60 μg/ml resulted in an increase in NOS3 mRNA abundance of 1.8- and 2.4-fold, respectively (P < 0.05; Fig. 7D). There was no significant change in NOS3 mRNA abundance in cells treated with sHDL at 15 and 120 μg/ml compared to that in LPS-treated controls. In addition, sHDL at all concentrations (15 to 120 μg/ml) suppressed the LPS-induced production of IL-6 (Fig. 7E) and IL-8 (Fig. 7F) by >4- and >50-fold compared to that by PBS-treated controls, respectively (P < 0.01).

Fig. 7. sHDL inhibits the LPS- and TNF-α–induced activation of HUVECs and inflammatory cytokine production.

(A to F) HUVECs were treated with LPS (100 μg/ml) in the presence of either sHDL (15, 30, 60, or 120 μg/ml peptide) or PBS for 16 hours. (A to D) The fold changes in the relative abundances of mRNAs encoding VCAM-1 (A), ICAM-1 (B), E-selectin (ELSE) (C), and eNOS (NOS3) (D) normalized to that of GAPDH mRNA were determined by RT-qPCR analysis. (E and F) The concentrations of the cytokines IL-6 (E) and IL-8 (F) secreted by the indicated cells into the culture medium were measured by ELISA. Data are means ± SD of three independent experiments.

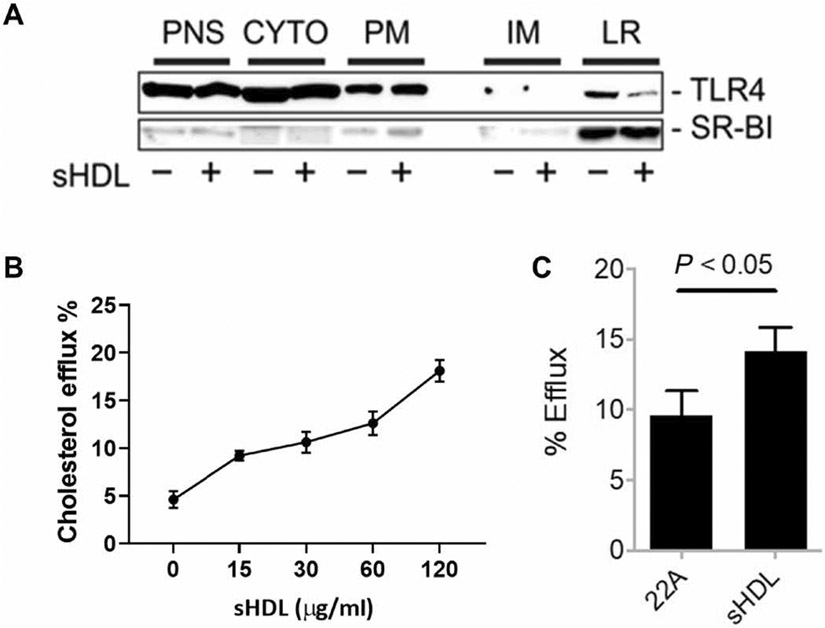

sHDL promotes the efflux of membrane cholesterol, which reduces TLR abundance in lipid rafts and suppresses TLR4 signaling in RAW264.7 cells

HDL has other anti-inflammatory properties independent of endotoxin binding (24, 25). This was evident through our finding that TLR4–NF-κB signaling was still significantly reduced in cells that are treated with sHDL and LPS separately (Fig. 5, C and E). TLR4 is located in lipid rafts, plasma membrane microdomains that are rich in cholesterol. We speculated that sHDL reduced lipid raft cholesterol abundance, which led to suppression of TLR4–NF-κB signaling. To examine whether sHDL suppressed the localization of TLR4 to lipid rafts, we preincubated RAW264.7 cells with or without sHDL (60 μg/ml) for 6 hours. The sHDL was then removed, and the cells were incubated for 10 min with or without LPS. The cells were then fractionated, and TLR4 and scavenger receptor class B type I (SR-BI; a marker protein in lipid rafts) in different fractions were analyzed by Western blotting. In cells treated with sHDL, the amount of TLR4 in the lipid rafts was markedly reduced compared to that in vehicle-treated cells (Fig. 8A). To confirm these findings, we also tested the cholesterol efflux activity of sHDL in experiments with [3H]-cholesterol–loaded cells and found that sHDL could efflux cholesterol in a dose-dependent manner, with about 20% of total [3H]-cholesterol effluxed to sHDL after 4 hours of incubation (Fig. 8B). The efflux activity of the 22A peptide was also tested, but this had significantly less activity compared to that of intact sHDL particles (Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8. sHDL suppresses the targeting of TLR4 to lipid rafts.

(A) RAW264.7 cells were treated for 14 hours with LPS (2 ng/ml) in the presence or absence of sHDL (60 μg/ml). The cells were then subjected to subcellular fractionation, and the post-nuclear supernatant (PNS), cytosol (CYTO), plasma membrane (PM), intracellular membrane (IM), and lipid raft (LR) fractions were analyzed by Western blotting with antibodies against TLR4 and the lipid raft marker SR-BI. Western blots are representative of two independent experiments. (B) RAW264.7 cells were treated for 4 hours with the indicated concentrations of sHDL, and the percentage cholesterol efflux was then determined as described in Materials and Methods. Data are means ± SD of three independent experiments. (C) RAW264.7 cells were treated for 6 hours with sHDL or 22A peptide (each at 15 μg/ml) before cholesterol efflux was determined. Data are means ± SD of three independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

Here, we showed that septic patients have a significant decrease in their HDL-C abundance compared to that of nonseptic ICU patients. Together with our previous studies of HDL-deficient mice (10, 26), these findings suggest that a decrease in HDL abundance is a risk factor for sepsis and that increasing HDL abundance may offer a viable therapeutic strategy against sepsis. To test this hypothesis, we used ETC-642, a new generation of sHDL, and showed that it increased 7-day survival in CLP-challenged mice, suggesting that sHDL treatment is a viable therapeutic strategy for sepsis. We also provided evidence supporting our hypothesis that sHDL protects against sepsis through multiple protective mechanisms, not only by neutralizing endotoxins (both LPS and LTA) but also by suppressing inflammatory signaling in both macrophages and ECs. Together, our in vitro and in vivo findings suggest that peptide-based sHDL may be an effective and clinically translatable therapy for sepsis. Moreover, the previously established clinical manufacturing, as well as animal and human safety of ETC-642, greatly increases our ability to rapidly test its protective ability in patients.

HDL plays essential roles in vascular ECs and immunity, and a marked decrease in plasma HDL-C concentration during sepsis results in a loss of these functions. Consistent with the previous findings of Chien et al. (8), we observed that HDL-C abundance was markedly reduced in septic patients and that patients with an HDL-C concentration of <10 mg/dl had nearly double the incidence of mortality compared to those with greater HDL-C abundance. It was also evident that, in survivors, HDL-C abundance slowly increased over 14 days, whereas nonsurvivors exhibited no such increase (Fig. 1). In 2014, Al-Zaidawi (27) reported similar data, whereby patients with an HDL-C concentration of <15 mg/dl had a significantly increased risk of developing sepsis, and those who eventually died from sepsis all had an HDL-C concentration of <5 mg/dl in the 1 or 2 days preceding death. Trinder et al. (28) identified that carriers of a gain-of-function genetic variant in the cholesterol ester transfer protein gene, rs1800777, exhibit an exacerbated decrease in HDL-C concentration under septic conditions when compared to noncarriers, and consequently, they had reduced overall survival rates. This allele and the accompanying reduction in HDL-C abundance were also determined to increase sepsis-associated acute kidney injury and compromised renal function (29, 30). Thus, increasing circulating HDL in patients with sepsis presenting with low HDL-C abundance remains an attractive therapeutic strategy.

Despite overwhelming evidence, the exploitation of HDL for use as a sepsis therapy has been somewhat abandoned since about 2010. Numerous earlier efforts were made to test the feasibility of first-generation rHDL/sHDL or naked ApoA-I as a sepsis therapy. Findings from studies of endotoxemia animal models were encouraging and showed that rHDL and sHDL could improve survival in LPS-challenged animals (4, 21, 31-36). Using rHDL made of human ApoA-I, Quezado et al. (37) reported that the administration of rHDL suppressed inflammatory cytokine production in a Gram-negative bacterial infection model but failed to improve survival, likely because of the toxicity and impurity of the rHDL product. Studies with the ApoA-I mimetic peptide 4F showed that peptide treatment could increase HDL-C abundance and improve 2- and 4-day survival in CLP-treated rats (20, 38). However, despite these findings, studies using first-generation rHDL or ApoA-I peptides suffered from a lack of clinical translatability, limited by poor purity, contamination, toxicity, and short circulation times (20, 37, 39, 40). This may explain the need for greater doses of rHDL to show efficacy, ranging from 45 to 500 mg/kg in various animal models (4, 34, 35, 41-44), whereas highly pure second-generation sHDL, in this case, ETC-642, is effective in many aspects at doses as little as 7.5 mg/kg in mice. Thus, the synthetic-based approach of sHDL development enables greater control and flexibility over the production process and results in a cheaper, purer, and user-defined end product.

Several sepsis therapies have reached clinical trials over the past 20 years, yet for one reason or another, they have all failed. One issue with past therapeutic approaches is that they only targeted one element of an incredibly complex and dynamic disease. Such examples include TNF receptor agonists and LPS- and TNF-neutralizing antibodies, among others (45). Given the multifaceted nature of the disease, sHDL offers a wider range of protection through its multiple mechanisms of action. Whereas we and others have documented the inherent ability of HDL to neutralize and detoxify endotoxin (3, 4, 18), in the current study, we also showed that HDL exerted other anti-inflammatory properties, such as inhibition of EC activation and modulation of lipid rafts, which is consistent with other reports showing the anti-inflammatory properties of HDL in models of cardiovascular disease (17, 24, 25, 46, 47). The immunosuppressive effects of sHDL did not compromise bacterial clearance because no changes in bacterial load were observed in blood or spleen between control and sHDL-treated septic mice. HDL therapy also provides a level of patient selection, a factor that has been considerably challenging given the high patient heterogeneity in sepsis. Given the cardioprotective and immune-regulating properties of HDL and that a breakdown in the function of vascular ECs is a major contributor to mortality in sepsis, it is worth considering whether sHDL can prevent or reverse endothelial dysfunction in septicemia.

Whereas our findings using ETC-642 as a sepsis therapy are encouraging, there is even greater potential in the optimization of second-generation sHDLs for sepsis-specific purposes. ETC-642 was previously developed for the treatment of cardiovascular disease and was optimized primarily for its ability to efflux cholesterol. However, we previously showed that the phospholipid composition of sHDL can substantially alter its overall function, that is, cytokine inhibition, efflux capacity, and others (48). Given these data, there is great potential to tailor sHDL composition to enhance its overall efficacy in sepsis. We also hypothesize that dosing regimen optimization is critical to the success of sHDL therapy in sepsis. Whereas the current study used a one-time bolus administration of ETC-642 at a low dose, efforts to improve clinical outcome by exploring alternative dosing regimens are underway.

One limitation of the current study is the difficulty in matching the septic condition in mice to that observed in humans. The present study used sHDL treatment in the absence of antibiotics, largely because of the fact that the substantial increase in the survival rate of mice administered antibiotics leads to the need for a large number of animals to show statistical significance (>200 per group). However, given the high incidence of antibiotic resistance in septic patients, the therapeutic potential of sHDL is still relevant. In addition, the onset of sepsis occurs much more rapidly in CLP mice than in humans. Whereas the bulk of our experiments showed the efficacy of sHDL when it was administered 2 hours after the induction of CLP, we also showed that sHDL given 6 hours after CLP moderately increased the 7-day survival rate in mice. Thus, our study shows proof of concept for the therapeutic potential of sHDL. Together, our findings reveal that second-generation sHDL particles are a promising avenue toward the treatment of sepsis. Although future work is needed to build upon this platform and maximize the potential benefit, we have demonstrated efficacy against sepsis with a clinically translatable therapeutic with considerable adaptability and broadly applicable applications in inflammatory disease models.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

The 22A peptide (PVLDLFRELLNELLEALKQKLK) was synthesized by GenScript, and purity was determined to be >95% by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis. Egg SM and DPPC were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids and Nippon Oil and Fat. LPS (Escherichia coli O111:B4) and fluorescent LPS (E. coli 055:B5; Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. LPS (E. coli K12) was purchased from InvivoGen. The serum against SR-BI was custom-made by Sigma-Genosys with a 15–amino acid long peptide derived from the C terminus of human SR-BI. The specificity of the antibody was verified by Western blotting analysis of SR-BI–null tissues (26). Antibody against TLR4 was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (catalog no. sc-293072). All other reagents were obtained from commercial suppliers and were of analytical grade or higher.

Patients

Patients were recruited at the University of Michigan Medical ICU at the time of admission, between September 2001 and April 2004. Sepsis was defined as described by the American-European Sepsis Consensus Conference. Before entry into the study, an informed consent was properly obtained from the patient or the patient’s legally acceptable representative. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, MI. At the time of entry, a complete medical/sepsis history and a physical examination were obtained from each patient. The following data were recorded: APACHE III (Acute Physiology, Age, Chronic Health Evaluation) score; results of chest x-ray; electrocardiogram; ventilator parameters, positive culture; antigenic or nucleic acid assay results from any suspected source of sepsis; urinary output; and administration of neuromuscular blocking agents, antibiotics, vasopressors, and sedatives during the preceding 24 hours. The APACHE III score was assigned once per day by a trained nurse at the ICU unit on the basis of the previous 24 hours of evaluation. From the laboratory studies, we recorded arterial blood gases; most recent pulmonary artery systolic, diastolic, and wedge pressure (where available); blood profile; serum electrolytes; glucose; bilirubin; and albumin.

Patient inclusion and exclusion criteria

For the patients with sepsis, we enrolled individuals of both sex and aged ≥18 years who had at least two signs of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS). SIRS was defined by core, rectal, axillary, or oral temperature of ≥38°C or otherwise unexplained core or rectal temperature of ≤36°C; heart rate of ≥90 beats per minute; respiratory rate of ≥20 per minute or PaCO2 of ≤32 mmHg or the patient was on a ventilator; and white blood cells ≥ 12,000/mm3 or ≤ 4000/mm3 or ≥ 10% immature neutrophils (bands). The source of sepsis was documented by culture, Gram stain, or nucleic acid assay of blood or a normally sterile body fluid positive for a pathogenic microorganism that constituted the reason for systemic therapy with anti-infectives; chest radiography consistent with a diagnosis of pneumonia that constituted the reason for systemic therapy with anti-infectives; clearly verifiable focus of infection identified, for example, perforated bowel with the presence of free air or bowel contents in the abdomen found at surgery; and/or wound with purulent drainage. We also enrolled patients with septic shock [hypotension despite adequate fluid resuscitation (systolic blood pressure of ≤90 mmHg and mean arterial blood pressure of ≤65 mmHg) and need for vasopressors] or with organ dysfunction/hypoperfusion as a result of sepsis (for example, pulmonary dysfunction, PaO2/FIO2 < 250 or < 200 in the presence of pneumonia or other localizing lung disease; metabolic acidosis, pH ≤ 7.30 or increased plasma lactate concentration; oliguria, urine output of <0.5 ml/kg per hour for a minimum of two consecutive hours in the presence of adequate fluid resuscitation; thrombocytopenia, platelet count of <100,000 cells/mm3 without other causes of thrombocytopenia; and acute alteration in mental status). Patients were excluded for the following criteria: pregnancy confirmed by urine or serum test; substantial liver disease as defined by fulfillment of Child-Pugh Grade C or known esophageal varices; HIV infection with CD4+ T cell count of <200; prednisone therapy of >20 mg/day (or equivalent) and cytotoxic therapy within 3 weeks before screening; confirmed, clinically evident acute pancreatitis; extracorporeal support of gas exchange at the time of study entry; or receipt of an investigational drug within 30 days before study enrollment. For the nonseptic control group, we enrolled individuals of either sex and age of >18 years admitted to the ICU for disorders other than sepsis, who did not have any of the exclusion criteria outlined earlier.

Patient characteristics

A total of 124 patients from the Critical Care Medicine Unit at the University of Michigan Medical Center were recruited in this study, of which 85 were patients with sepsis and 38 were without sepsis. The demographic characteristics of the enrolled patients are presented in table S1.

Blood sampling and analysis

Blood samples (15 to 20 ml) were taken in heparinized tubes within 24 hours of admission, as well as at 1, 3, 7, and 14 days after entry. Plasma was separated by centrifugation at 4°C, aliquoted, and stored at −80°C before analysis. HDL cholesterol (Roche kit, 3030067), total cholesterol (Roche kit, 450061), triglycerides (Roche kit, 1488899), ApoA-I [Wako kit (Richmond, VA), 991-27201], and aspartate aminotransferase (Roche kit, 450064) were analyzed on a Hitachi 912 clinical chemistry autoanalyzer (Roche Diagnostics Corporation).

sHDL preparation

Discoidal ETC-642 sHDL nanoparticles were made by colyophilization followed by thermal cycling as described previously (16, 49). Briefly, 22A peptide and phospholipids were combined and dissolved in glacial acetic acid at a 22A:SM:DPPC ratio of 1:1:1 by weight (17). The resulting solution underwent rapid freezing in liquid nitrogen, which was followed by freeze-drying overnight to remove the acid. The lyophilized powder was reconstituted in 1× PBS to the desired final peptide concentration and vortexed to completely dissolve, forming a cloudy white suspension. The resulting solution was subjected to three heat-cool cycles, each cycle consisting of 10 min of heating at 55°C and 10 min of cooling at room temperature, at which point, a clear solution was formed. The pH of the final sHDL solution was adjusted to 7.4 with NaOH and was then passed through a 0.2-μm sterile filter.

sHDL characterization

The quality of the ETC-642 sHDL particles was assessed with the following analytical techniques. Size distribution was determined by DLS on a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZSP, and particle purity was determined by GPC with ultraviolet detection at 220 nm with a Tosoh TSKgel G3000SWxl column (Tosoh Bioscience) on a Waters HPLC, as previously described (50). TEM images were obtained as previously described (48) by diluting samples with 1% uranyl acetate negative stain solution. Images were acquired on a JEM 1200EX electron microscope (JEOL) equipped with an AMT XR-60 digital camera (Advanced Microscopy Techniques Corp.). Endotoxin concentrations in the final sterile formulations were determined with the Pyrotell Limulus Amebocyte Lysate Assay (Associates of Cape Cod Inc., no. GP5003).

Cell culture

Primary HUVECs from pooled donors (Lonza, C2519AS) were cultured in tissue culture vessels coated with 0.2% gelatin type B (Sigma-Aldrich) containing Clonetics EGM-2 Complete Media (Lonza). Cells between passages three to five were used in all experiments. RAW264.7 murine macrophages (American Type Culture Collection, TIB-71) were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). HEK-Blue cells, which stably express CD14, MD2, a NF-κB reporter, and TLR4 or TLR2, were obtained from InvivoGen. The cells were cultured in 96-well plates in complete DMEM containing 10% Endo-low FBS to 70% confluency and were treated with LPS or LTA for 16 hours. Cell culture medium (100 μl) was then mixed with 100 μl of HEK-Blue Detection Medium and incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. LPS and LTA activate TLR4 and TLR2, respectively, resulting in induction of NF-κB reporter expression, which catalyzes the conversion of the HEK-Blue Detection Medium to a blue color, which was quantified by measuring the absorption at 650 nm. All incubations were performed in a 37°C incubator under 5% CO2 atmospheric conditions.

In vivo efficacy analysis

We chose the CLP model as a more physiologically relevant model of abdominal sepsis, as compared to the administration of LPS or bacteria. CLP (21-gauge needle, 2/3 ligation) was performed on 10- to 12-week-old male C57BL/6J mice as described previously (26). Female mice were excluded because of the substantial effects of female sex hormones on cell-mediated immune responses, rendering them less susceptible to sepsis (51). Two hours after CLP, the mice were treated with 100 μl of PBS or sHDL at 7.5 mg peptide/kg body weight (intravenously). Survival was monitored for a 7-day period. Eighteen hours after CLP, body temperature was recorded, and the plasma and lungs were harvested. HDL was isolated from the plasma by sequential ultracentrifugation as previously described (1.5 ml of plasma from five mice was used to make one HDL preparation) (52, 53), and the total HDL cholesterol was measured with a Wako Diagnostics kit. Organ injury was determined by quantifying the amount of plasma alanine amino transferase (ALT), the lung wet/dry ratio, and plasma BUN amounts. The amounts of the cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-10 in the plasma were quantified by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; BioLegend or eBioscience).

Analysis of NF-κB expression in HEK-Blue cells

HEK-Blue cells expressing TLR4, TLR2, or the TNF-α receptor and an NF-κB reporter were used to assess ligand-stimulated NF-κB activation. The cells were cultured to 70% confluency and treated with LPS (K12, 1 ng/ml), LTA (40 ng/ml), or TNF-α (0.5 ng/ml) in the presence of sHDL for 16 hours. Alternatively, cells were pretreated with sHDL (60 μg/ml) for 6 hours, which was followed by stimulation with LPS, LTA, or TNF-α. The culture medium (100 μl) was mixed with 100 μl of HEK-Blue Detection, and the activation of the NF-κB reporter was quantified by measuring absorption at 650 nm.

Analysis of cytokine production by RAW264.7 cells

RAW264.7 cells were cultured to 70% confluency and treated with LPS (K12, 2 ng/ml) or LTA (40 ng/ml) in the presence of sHDL (0, 15, 30, 60, or 120 μg peptide/ml) for 16 hours. The concentrations of TNF-α and IL-6 secreted by the cells into the cell culture medium were measured by ELISA.

Analysis of cytokine production by HUVECs

HUVECs were seeded into 96-well plates and grown to 90% confluency. Cells were washed twice with 1× PBS and incubated with LPS (K12, 100 ng/ml) or TNF-α (1 ng/ml) in the presence of sHDL (peptide, 15, 30, 60, or 120 μg/ml) or matching concentrations of the 22A peptide, SM-DPPC liposomes, or PBS for 16 hours. The concentrations of the cytokines IL-6 and IL-8 secreted by the cells into the culture medium were quantified by ELISA.

Gene expression analysis

HUVECs were seeded into 96-well plates and grown to 90% confluency. Cells were treated with LPS (100 μg/ml) in the presence of either sHDL (peptide, 15, 30, 60, or 120 μg/ml) or matching concentrations of 22A peptide, SM-DPPC liposomes, or PBS for 16 hours. After incubation, the cells were washed twice in PBS and cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation buffer (50 mM tris, 150 mM NaCl, 1% SDS, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, and 1% Triton X-100) containing cOmplete EDTA-free protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche). Total RNA was extracted with an RNeasy Mini kit (QIAGEN) and reverse-transcribed to cDNA with an iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). Gene expression was determined by reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) analysis with a StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems) with TaqMan Gene Expression assays for ICAM-1 (Hs00164932_m1), VCAM-1 (Hs01003372_m1), eNOS (NOS3, Hs01574659_m1), and E-selectin (SELE, Hs00174057_m1) (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Data were normalized relative to the abundance of endogenous glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH; Hs03929097_g1), and the fold change in gene expression was calculated with the ΔΔCT method.

Isolation of lipid rafts

Lipid rafts and other subcellular fractions were isolated with the OptiPrep method as previously described (54). We used SR-BI as a marker protein in lipid rafts. TLR4 and SR-BI in each fraction were analyzed by Western blotting.

Determination of total cellular cholesterol

Total cellular cholesterol was determined by treating RAW264.7 cells with sHDL (60 μg/ml) or vehicle for 12 hours. Cells were then scraped and collected, and cholesterol was extracted and quantified with a Wako total cholesterol reagent kit (Wako Diagnostics).

Analysis of cholesterol efflux

Cholesterol efflux studies were performed with RAW264.7 cells. Briefly, the cells were cultured in DMEM containing 10% FBS and 1% penicillin-streptomycin in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. Cells were incubated with 1 μCi/ml [3H] cholesterol (PerkinElmer) in DMEM containing fatty acid–free bovine serum albumin (FAFA; 1 mg/ml) and the ACAT inhibitor Sandoz 58-035 (5 μg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich) overnight. Cells were then washed twice with PBS and equilibrated in fresh DMEM containing FAFA (1 mg/ml) and Sandoz 58-035 (5 μg/ml) for 24 hours. Then, 0.5 mM 8-Br-cAMP (8-bromoadenosine 3′,5′-cyclic monophosphate) was added into the medium to induce ABCA1/ABCG1 expression for 20 hours. The cells were then washed twice with PBS, and sHDL was added at peptide concentrations ranging from 15 to 120 μg/ml in DMEM/BSA. After either 4 or 6 hours of incubation, the culture medium was collected and centrifuged at 7000g for 3 min to remove any floating cells. Last, the remaining cells were lysed with 0.5 ml of 0.1% SDS and 0.1 M NaOH. Radioactive counts in the medium and cell fractions were measured by liquid scintillation counting (PerkinElmer), and the percentage of cholesterol effluxed was calculated by dividing the count for the medium by the sum of the counts for the medium and the cells and then multiplying this number by 100%.

Isothermal titration calorimetry

Microcalorimetric measurements of the binding of sHDL to LPS were performed on a VP isothermal titration calorimeter (MicroCal Inc.) at 37°C. Typically, 20 consecutive 15-μl aliquots of sHDL at a concentration of 0.4 mM (1.05 mg/ml) were injected into the cell (1.5 ml) filled with 2 μM (0.03 mg/ml) LPS solution. Both sHDL and LPS solutions were degassed under vacuum immediately before use. Injections were made at 400-s intervals. A constant stirring speed of 310 rpm was maintained during the experiment to ensure proper mixing after each injection. Data were analyzed using the software available for uptake assay.

Coarse-grained (CG) model of sHDL nanoparticles

The atomistic initial model of 22A was constructed with an α-helical secondary structure with PyMOL (55). The atomistic model was then transformed to a CG model by applying the MARTINI v2.2 force field for protein (56, 57). For the CG model of solvent molecules, four water molecules were represented as a single CG bead. Ions in the CG model were represented as charged CG beads with their first hydration shell implicitly included (57). The parameters for the SM and DPPC lipids in the CG model were adopted from the MARTINI force field for lipids (58). The CG parameter for LTA was generated on the basis of the parameter of galactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG) from the MARTINI force field for glycolipids (31, 32). An additional Qa bead was added to represent the additional phosphate group found on LTA. Bond and angle parameters for the new Qa bead were adopted from the parameters of phosphatidylinositol in the MARTINI force field for glycolipids. Parameterization for LPS was generated by iteratively fitting the CG model with an all-atomistic model, according to a protocol similar to that of López et al. (31). The initial model simulation system for sHDL (S1) was constructed with a random distribution of 20 sHDL peptides, 75 polyphosphatidyl cholines (PPCS) molecules, and 75 DPPC molecules, following the 1:3.75:3.75 molar ratio of corresponding components in the sHDL particle. A total of 20 α-helical peptides (equivalent number of α helices for two ApoA-I lipoproteins in the double-belt model) and 150 lipids in the system is approximated to the composition of reported models of discoidal HDL particles (33, 59-61). The initial model simulation system for the lipid-only particle (S0, control) was also constructed with a random distribution of 75 PPCS molecules and 75 DPPC molecules, without the addition of sHDL peptides. CG beads of water and ions (0.15 M NaCl) were added to both systems for the simulation of the physiological environment. Simulations totaling 3 μs with a 30-fs integration at a temperature of 323 K were performed for each system with GROMACS v4.6 (62). A temperature of 323 K in the CG simulation was used to reproduce the results of the all-atom simulation at temperatures ranging from 300 to 315 K (58, 63, 64).

Binding model and free energy calculation for the binding of sHDL with LPS and LTA

To simulate the binding conformation of LTA or LPS with the sHDL particle, one LTA or LPS molecule was randomly added into solvent of the two previously equilibrated simulation systems, that is, S0 and S1. The combined four systems were termed S0-LTA, S0-LPS, S1-LTA, and S1-LPS, respectively. Solvent beads that over-lapped with LTA or LPS were removed, whereas the charge introduced by LTA or LPS was naturalized by adding counter ions (Na+) in each of the four systems. Then, simulations totaling 1 μs with a 30-fs integration time step at 323 K were performed for each system with GROMACS v4.6 (62). The PMF was calculated with the pull code and weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM) (65, 66), implemented in GROMACS v4.6, to estimate the binding free energy of LTA or LPS with the sHDL particle. On the basis of the previously equilibrated LTA or LPS binding simulation systems, the reaction coordinates of LTA or LPS binding with sHDL were obtained by pulling the center of mass (COM) for LTA or LPS 8 nm away from the COM for the sHDL particle in 80-ns simulations with a time step of 30 fs. Then, 40 sampling windows were subjected to an additional 10-ns equilibration (30-fs time step) and 10-ns umbrella sampling (5-fs time step) based on the reaction coordinates with an interval of 0.2 nm. The binding free energy of LTA or LPS with the lipid-only particle was also estimated in the same way. Three independent PMF calculations were performed for each system to average the fluctuations.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± SEM or means ± SD as indicated in the figure legends. Statistical significance in experiments comparing two groups was determined by two-tailed Student’s t test. Comparison of more than two groups was evaluated by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), which was followed by Tukey’s post hoc analysis. Means were considered to be statistically significantly different where P < 0.05. Survival was analyzed by the log-rank test and Kaplan-Meier plots using SPSS software. Unless otherwise specified in the figure legends, all other experimental data were statistically evaluated with GraphPad Prism software.

Supplementary Material

Funding:

This publication was made possible by NIH R01GM113832 (to X.-A.L. and A.S.); NIH R01GM121796, NIH R35GM141478, and VA 1I01BX004639 (to X.-A.L.); AHA 13SDG17230049 (to A.S.); NIH T32-HL125242 (to E.E.M. and M.V.F.); T32 GM008353 (to E.M.); and T32 GM007767 (to M.V.F.). The contents of this manuscript are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIGMS, NIH, VA, or AHA.

Footnotes

Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data associated with this study are available in the main text or the Supplementary Materials.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche J-D, Coopersmith CM, Hotchkiss RS, Levy MM, Marshall JC, Martin GS, Opal SM, Rubenfeld GD, van der Poll T, Vincent J-L, Angus DC, The third international consensus definitions for sepsis and septic shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA 315, 801–810 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brandenburg K, Jürgens G, Andrä J, Lindner B, Koch MHJ, Blume A, Garidel P, Biophysical characterization of the interaction of high-density lipoprotein (HDL) with endotoxins. Eur. J. Biochem 269, 5972–5981 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levels JHM, Abraham PR, van den Ende A, van Deventer SJH, Distribution and kinetics of lipoprotein-bound endotoxin. Infect. Immun 69, 2821–2828 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levine DM, Parker TS, Donnelly TM, Walsh A, Rubin AL, In vivo protection against endotoxin by plasma high density lipoprotein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 90, 12040–12044 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Nardo D, Labzin LI, Kono H, Seki R, Schmidt SV, Beyer M, Xu D, Zimmer S, Lahrmann C, Schildberg FA, Vogelhuber J, Kraut M, Ulas T, Kerksiek A, Krebs W, Bode N, Grebe A, Fitzgerald ML, Hernandez NJ, Williams BRG, Knolle P, Kneilling M, Rocken M, Lutjohann D, Wright SD, Schultze JL, Latz E, High-density lipoprotein mediates anti-inflammatory reprogramming of macrophages via the transcriptional regulator ATF3. Nat. Immunol 15, 152–160 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harris HW, Johnson JA, Wigmore SJ, Endogenous lipoproteins impact the response to endotoxin in humans. Crit. Care Med 30, 23–31 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mineo C, Deguchi H, Griffin JH, Shaul PW, Endothelial and antithrombotic actions of HDL. Circ. Res 98, 1352–1364 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chien J-YM, Jerng J-SM, Yu C-JM, Yang P-CM, Low serum level of high-density lipoprotein cholesterol is a poor prognostic factor for severe sepsis. Crit. Care Med 33, 1688–1693 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsai MH, Peng YS, Chen YC, Lien JM, Tian YC, Fang JT, Weng HH, Chen PC, Yang CW, Wu CS, Low serum concentration of apolipoprotein A-I is an indicator of poor prognosis in cirrhotic patients with severe sepsis. J. Hepatol 50, 906–915 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo L, Ai J, Zheng Z, Howatt DA, Daugherty A, Huang B, Li XA, High density lipoprotein protects against polymicrobe-induced sepsis in mice. J. Biol. Chem 288, 17947–17953 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Morin EE, Guo L, Schwendeman A, Li X-A, HDL in sepsis—Risk factor and therapeutic approach. Front. Pharmacol 6, 244 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dassuex J-L, Sekul R, Bittner K, Cornut I, Metz G, Dufourcq J, Apolipoprotein A-I agonists and their use to treat dyslipidemic disorders, US Patent 6004925 (1999).

- 13.Khan M, Lalwani ND, Drake SL, Crockatt JG, Dasseux JLH, Single-dose intravenous infusion of ETC-642, a 22-Mer ApoA-I analogue and phospholipids complex, elevates HDL-C in atherosclerosis patients. Circulation 108, 563–564 (2002). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Miles J, Khan M, Painchaud C, Lalwani N, Drake S, Dasseux JL, Single-dose tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and cholesterol mobilization in HDL-C fraction following intravenous administration of ETC-642, a 22-mer ApoA-I analogue and phospholipids complex, in atherosclerosis patients. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 24, E19 (2004).14766740 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kuai R, Li D, Chen YE, Moon JJ, Schwendeman A, High-density lipoproteins: Nature’s multifunctional nanoparticles. ACS Nano 10, 3015–3041 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li D, Gordon S, Schwendeman A, Remaley AT, Apolipoprotein Mimetics in the Management of Human Disease (Springer, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Di Bartolo BA, Nicholls SJ, Bao S, Rye K-A, Heather AK, Barter PJ, Bursill C, The apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptide ETC-642 exhibits anti-inflammatory properties that are comparable to high density lipoproteins. Atherosclerosis 217, 395–400 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levels JHM, Abraham PR, van Barreveld EP, Meijers JCM, van Deventer SJH, Distribution and kinetics of lipoprotein-bound lipoteichoic acid. Infect. Immun 71, 3280–3284 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miles J, Khan M, Painchaud C, Lalwani N, Drake S, Dasseux J, in Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004), vol. 24, pp. E19–E19.14766740 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang Z, Datta G, Zhang Y, Miller AP, Mochon P, Chen YF, Chatham J, Anantharamaiah GM, White CR, Apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptide treatment inhibits inflammatory responses and improves survival in septic rats. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol 297, H866–H873 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dai L, Datta G, Zhang Z, Gupta H, Patel R, Honavar J, Modi S, Wyss JM, Palgunachari M, Anantharamaiah GM, White CR, The apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptide 4F prevents defects in vascular function in endotoxemic rats. J. Lipid Res 51, 2695–2705 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hack CE, Zeerleder S, The endothelium in sepsis: Source of and a target for inflammation. Crit. Care Med 29, S21–S27 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee WL, Slutsky AS, Sepsis and endothelial permeability. N. Engl. J. Med 363, 689–691 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu X, Owen JS, Wilson MD, Li H, Griffiths GL, Thomas MJ, Hiltbold EM, Fessler MB, Parks JS, Macrophage ABCA1 reduces MyD88-dependent Toll-like receptor trafficking to lipid rafts by reduction of lipid raft cholesterol. J. Lipid Res 51, 3196–3206 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang S.-h., Yuan S.-g., Peng D.-q., Zhao S.-p., HDL and ApoA-I inhibit antigen presentation-mediated T cell activation by disrupting lipid rafts in antigen presenting cells. Atherosclerosis 225, 105–114 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Guo L, Song Z, Li M, Wu Q, Wang D, Feng H, Bernard P, Daugherty A, Huang B, Li X-A, Scavenger receptor BI protects against septic death through its role in modulating inflammatory response. J. Biol. Chem 284, 19826–19834 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Al-Zaidawi S, Presepsis biomarker: High-density lipoprotein. Crit. Care 18, P77–P77 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Trinder M, Genga KR, Kong HJ, Blauw LL, Lo C, Li X, Cirstea M, Wang Y, Rensen PCN, Russell JA, Walley KR, Boyd JH, Brunham LR, Cholesteryl ester transfer protein influences high-density lipoprotein levels and survival in sepsis. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med 199, 854–862 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roveran Genga K, Lo C, Cirstea M, Zhou G, Walley KR, Russell JA, Levin A, Boyd JH, Two-year follow-up of patients with septic shock presenting with low HDL: The effect upon acute kidney injury, death and estimated glomerular filtration rate. J. Intern. Med 281, 518–529 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Genga KR, Trinder M, Kong HJ, Li X, Leung AKK, Shimada T, Walley KR, Russell JA, Francis GA, Brunham LR, Boyd JH, CETP genetic variant rs1800777 (allele A) is associated with abnormally low HDL-C levels and increased risk of AKI during sepsis. Sci. Rep 8, 16764 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.López CA, Sovova Z, van Eerden FJ, de Vries AH, Marrink SJ, Martini force field parameters for glycolipids. J. Chem. Theory Comput 9, 1694–1708 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.López CA, Rzepiela AJ, De Vries AH, Dijkhuizen L, Hünenberger PH, Marrink SJ, Martini coarse-grained force field: Extension to carbohydrates. J. Chem. Theory Comput 5, 3195–3210 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Denisov IG, Grinkova YV, Lazarides AA, Sligar SG, Directed self-assembly of monodisperse phospholipid bilayer Nanodiscs with controlled size. J. Am. Chem. Soc 126, 3477–3487 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hubsch AP, Powell FS, Lerch PG, Doran JE, A reconstituted, apolipoprotein A-I containing lipoprotein reduces tumor necrosis factor release and attenuates shock in endotoxemic rabbits. Circ. Shock 40, 14–23 (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cue JI, DiPiro JT, Brunner LJ, Doran JE, Blankenship ME, Mansberger AR, Hawkins ML, Reconstituted high density lipoprotein inhibits physiologic and tumor necrosis factor alpha responses to lipopolysaccharide in rabbits. Arch. Surg 129, 193–197 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang L, Chen W-Z, Wu M-P, Apolipoprotein A-I inhibits chemotaxis, adhesion, activation of THP-1 cells and improves the plasma HDL inflammatory index. Cytokine 49, 194–200 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Quezado ZM, Natanson C, Banks SM, Alling DW, Koev CA, Danner RL, Elin RJ, Hosseini JM, Parker TS, Levine DM, Therapeutic trial of reconstituted human high-density lipoprotein in a canine model of gram-negative septic shock. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther 272, 604–611 (1995). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moreira RS, Irigoyen M, Sanches TR, Volpini RA, Camara NO, Malheiros DM, Shimizu MHM, Seguro AC, Andrade L, Apolipoprotein A-I mimetic peptide 4F attenuates kidney injury, heart injury, and endothelial dysfunction in sepsis. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol 307, R514–R524 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tardif J, Grégoire J, L’Allier PL, Ibrahim R, Lespérance J, Heinonen TM, Kouz S, Berry C, Basser R, Lavoie M-A, Guertin M-C, Rodés-Cabau J; Effect of rHDL on Atherosclerosis-Safety and Efficacy (ERASE) Investigators, Effects of reconstituted high-density lipoprotein infusions on coronary atherosclerosis: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 297, 1675–1682 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DiPiro JT, Cue JI, Richards CS, Hawkins ML, Doran JE, Mansberger AR Jr., Pharmacokinetics of reconstituted human high-density lipoprotein in pigs after hemorrhagic shock with resuscitation. Crit. Care Med 24, 440–444 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cockerill GW, McDonald MC, Mota-Filipe H, Cuzzocrea S, Miller NE, Thiemermann C, High density lipoproteins reduce organ injury and organ dysfunction in a rat model of hemorrhagic shock. FASEB J. 15, 1941–1952 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Casas AT, Hubsch AP, Doran JE, Effects of reconstituted high-density lipoprotein in persistent gram-negative bacteremia. Am. Surg 62, 350–355 (1996). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen Y, Schwendeman A, Guo Y, Zhang J, Yuan W, Morin E, Compositions and methods for treating cardiovascular related disorders, U.S. Provisional Patent Application No. 62/138,193 (2015).

- 44.McDonald MC, Dhadly P, Cockerill GW, Cuzzocrea S, Mota-Filipe H, Hinds CJ, Miller NE, Thiemermann C, Reconstituted high-density lipoprotein attenuates organ injury and adhesion molecule expression in a rodent model of endotoxic shock. Shock 20, 551–557 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fink MP, Warren HS, Strategies to improve drug development for sepsis. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov 13, 741–758 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Navab M, Imes SS, Hama SY, Hough GP, Ross LA, Bork RW, Valente AJ, Berliner JA, Drinkwater DC, Laks H, Monocyte transmigration induced by modification of low density lipoprotein in cocultures of human aortic wall cells is due to induction of monocyte chemotactic protein 1 synthesis and is abolished by high density lipoprotein. J. Clin. Invest 88, 2039–2046 (1991). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rye K-A, Bursill CA, Lambert G, Tabet F, Barter PJ, The metabolism and anti-atherogenic properties of HDL. J. Lipid Res 50(suppl), S195–S200 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schwendeman A, Sviridov DO, Yuan W, Guo Y, Morin EE, Yuan Y, Stonik J, Freeman L, Ossoli A, Thacker S, Killion S, Pryor M, Chen YE, Turner S, Remaley AT, The effect of phospholipid composition of reconstituted HDL on its cholesterol efflux and anti-inflammatory properties. J. Lipid Res 56, 1727–1737 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith CK, Seto NL, Vivekanandan-Giri A, Yuan W, Playford MP, Manna Z, Hasni SA, Kuai R, Mehta NN, Schwendeman A, Pennathur S, Kaplan MJ, Lupus high-density lipoprotein induces proinflammatory responses in macrophages by binding lectin-like oxidised low-density lipoprotein receptor 1 and failing to promote activating transcription factor 3 activity. Ann. Rheum. Dis 76, 602–611 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang J, Li D, Drake L, Yuan W, Deschaine S, Morin EE, Ackermann R, Olsen K, Smith DE, Schwendeman A, Influence of route of administration and lipidation of apolipoprotein A-I peptide on pharmacokinetics and cholesterol mobilization. J. Lipid Res 58, 124–136 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Angele MK, Pratschke S, Hubbard WJ, Chaudry IH, Gender differences in sepsis: Cardiovascular and immunological aspects. Virulence 5, 12–19 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coetzee GA, Strachan AF, van der Westhuyzen DR, Hoppe HC, Jeenah MS, de Beer FC, Serum amyloid A-containing human high density lipoprotein 3. Density, size, and apolipoprotein composition. J. Biol. Chem 261, 9644–9651 (1986). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.de Beer MC, Ji A, Jahangiri A, Vaughan AM, de Beer FC, van der Westhuyzen DR, Webb NR, ATP binding cassette G1-dependent cholesterol efflux during inflammation. J. Lipid Res 52, 345–353 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smart EJ, Ying YS, Mineo C, Anderson RG, A detergent-free method for purifying caveolae membrane from tissue culture cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 92, 10104–10108 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schrodinger LLC (2010).

- 56.Monticelli L, Kandasamy SK, Periole X, Larson RG, Tieleman DP, Marrink S-J, The MARTINI coarse-grained force field: Extension to proteins. J. Chem. Theory Comput 4, 819–834 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Marrink SJ, Risselada HJ, Yefimov S, Tieleman DP, de Vries AH, The MARTINI force field: Coarse grained model for biomolecular simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 111, 7812–7824 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Marrink SJ, De Vries AH, Mark AE, Coarse grained model for semiquantitative lipid simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 750–760 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Segrest JP, Jones MK, Klon AE, Sheldahl CJ, Hellinger M, De Loof H, Harvey SC, A detailed molecular belt model for apolipoprotein A-I in discoidal high density lipoprotein. J. Biol. Chem 274, 31755–31758 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shih AY, Denisov IG, Phillips JC, Sligar SG, Schulten K, Molecular dynamics simulations of discoidal bilayers assembled from truncated human lipoproteins. Biophys. J 88, 548–556 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Klon AE, Segrest JP, Harvey SC, Molecular dynamics simulations on discoidal HDL particles suggest a mechanism for rotation in the apo A-I belt model. J. Mol. Biol 324, 703–721 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Pronk S, Páll S, Schulz R, Larsson P, Bjelkmar P, Apostolov R, Shirts MR, Smith JC, Kasson PM, van der Spoel D, Hess B, Lindahl E, GROMACS 4.5: A high-throughput and highly parallel open source molecular simulation toolkit. Bioinformatics 29, 845–854 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Shih AY, Arkhipov A, Freddolino PL, Schulten K, Coarse grained protein-lipid model with application to lipoprotein particles. J. Phys. Chem. B 110, 3674–3684 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shih AY, Freddolino PL, Arkhipov A, Schulten K, Assembly of lipoprotein particles revealed by coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations. J. Struct. Biol 157, 579–592 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kumar S, Rosenberg JM, Bouzida D, Swendsen RH, Kollman PA, The weighted histogram analysis method for free-energy calculations on biomolecules. I. The method. J. Comput. Chem 13, 1011–1021 (1992). [Google Scholar]

- 66.Hub JS, De Groot BL, Van Der Spoel D, g_wham—A free weighted histogram analysis implementation including robust error and autocorrelation estimates. J. Chem. Theory Comput 6, 3713–3720 (2010). [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.