Abstract

Neutrophils are thought to be involved in many infectious diseases and have been found in high numbers in the corneas of patients with Acanthamoeba keratitis. Using a Chinese hamster model of keratitis, conjunctival neutrophil migration was manipulated to determine the importance of neutrophils in this disease. Inhibition of neutrophil recruitment was achieved by subconjunctival injection with an antibody against macrophage inflammatory protein 2 (MIP-2), a powerful chemotactic factor for neutrophils which is secreted by the cornea. In other experiments, neutrophils were depleted by intraperitoneal injection of anti-Chinese hamster neutrophil antibody. The inhibition of neutrophils to the cornea resulted in an earlier onset and more severe infection compared to controls. Anti-MIP-2 antibody treatment produced an almost 35% reduction of myeloperoxidase activity in the cornea 6 days postinfection, while levels of endogenous MIP-2 secretion increased significantly. Recruitment of neutrophils into the cornea via intrastromal injections of recombinant MIP-2 generated an initially intense inflammation that resulted in the rapid resolution of the corneal infection. The profound exacerbation of Acanthamoeba keratitis seen when neutrophil migration was inhibited, combined with the rapid clearing of the disease in the presence of increased neutrophils, strongly suggests that neutrophils play an important role in combating Acanthamoeba infections in the cornea.

The two major infectious diseases of the cornea that lead to blindness in North America, herpes simplex virus keratitis (HSVK) and Pseudomonas keratitis, are immune mediated (26, 30, 38). In both HSVK and Pseudomonas keratitis, the pathogenesis is dependent on CD4+ T cells, yet corneal lesions are heavily infiltrated with neutrophils (13, 15). These neutrophils are recruited to the cornea in response to the chemokine macrophage inflammatory protein 2 (MIP-2), which is secreted by corneal cells (12, 50). MIP-2 seems to play a dominant role in neutrophil recruitment, as neutralizing antibodies produce a sharp decrease in neutrophil infiltration and significantly reduce the corneal opacity in HSVK in BALB/c mice (23, 34, 39, 48–50).

Acanthamoeba keratitis is a vision-threatening corneal infection caused by a free-living, pathogenic amoeba (22, 45). Characteristic disease symptoms include a ring-like opaque infiltrate underlying an epithelial ulcer along with a disproportionately higher degree of pain than with other forms of keratitis (1, 21, 31). Treatment of this disease is very demanding, consisting of hourly topical applications of brolene, polyhexamethylene biguanide, or chlorhexidine for several weeks. Even with such regimented therapies, patients often require corneal transplants, which can in turn become reinfected by dormant amoebae (1).

Many Acanthamoeba species are ubiquitous in nature and can be readily isolated from swimming pools, hot tubs, freshwater, soil, dust, drinking fountains, eyewash stations, air, and the nasopharyngeal mucosa of healthy persons (2, 5, 6, 14, 19, 29, 32, 44, 46). Despite the wide distribution of the amoebae, this disease is largely restricted to the wearers of contact lenses who have experienced some sort of trauma to the corneal epithelium (2, 7, 36, 41, 45).

Although the precise mechanism by which Acanthamoeba infects the cornea is unknown, it is believed that corneal trauma is a prerequisite (27, 41). Upon abrasion, the corneal epithelium expresses elevated concentrations of mannose-glycoprotein, to which the amoebae can adhere with high affinity (25, 51). Subsequently, the amoebae penetrate and destroy the corneal epithelium and gain entry into the underlying stroma, which is primarily a collagenous matrix (11, 18, 28, 51). Once in the stroma, the amoebae secrete a collagenase that dissolves the collagenous matrix (11, 24).

Histological evaluation of Acanthamoeba keratitis lesions in both human and experimental animals revealed large numbers of neutrophils in the cornea (8, 9, 16, 20). Moreover, it has been reported that the most severe stromal necrosis in Acanthamoeba lesions is mediated by proteases released by neutrophils rather than the effects of the amoebae (1, 22). In vitro studies show that neutrophils do not exert significant activity against Acanthamoeba trophozoites unless they are activated by T-cell cytokines (37). In fact, it is possible that infiltrating neutrophils exacerbate the pathogenesis of corneal disease in a manner similar to that described for HSVK (50). MIP-2 has been shown to be the primary chemotactic factor for neutrophil infiltration in rat lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation models as well playing a role in many aspects of wound healing in mice (40, 47).

In this study, therefore, we tested the hypothesis that corneal infections with Acanthamoeba trophozoites would induce the production of MIP-2, which would in turn promote the recruitment of neutrophils to the infected cornea. We further predicted that inhibiting neutrophil recruitment would mitigate the clinical features of Acanthamoeba keratitis in a manner similar to the aforementioned findings with HSVK and Pseudomonas keratitis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Chinese hamsters were purchased from Cytogen Research and Development. All animals used were from 4 to 6 weeks of age, and all corneas were examined before experimentation to exclude animals with preexisting corneal defects. Animals were handled in accordance with the Association of Research in Vision and Ophthalmology “Statement on the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research” (http://www.arvo.org/animalst.htm).

Amoebae.

Acanthamoeba castellanii ATCC 30868, originally isolated from a human cornea, was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, Va. Amoebae were grown as axenic cultures in peptone-yeast extract-glucose at 35°C with constant agitation (44).

Contact lens preparation.

Contact lenses were prepared from Spectra/Por dialysis membrane tubing (Spectrum Medical Industries, Los Angeles, Calif.) using a 3-mm trephine and heat sterilized. Lenses were placed in sterile 96-well microtiter plates (Costar, Cambridge, Mass.) and incubated with 3 × 106 A. castellanii trophozoites at 35°C for 24 h. Attachment of amoebae to the lenses was verified microscopically before infection (28).

In vivo corneal infections.

Acanthamoeba keratitis was induced as described previously (17, 42). Briefly, the Chinese hamsters were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg; Fort Dodge Laboratories, Fort Dodge, Iowa) injected peritoneally. Prior to manipulation, the corneas were anesthetized with Alcain (Alcon Laboratories, Fort Worth, Tex.), a topical anesthetic. Approximately 25% of the cornea was abraded using a sterile cotton applicator, and then amoeba-laden lenses were placed onto the center of the cornea. The eyelids were then closed by tarsorrhaphy using 6-0 Ethilon sutures (Ethicon, Somerville, N.J.). The contact lenses were removed 3 to 4 days postinfection, and the corneas were visually inspected for severity of disease. Visual inspections were recorded daily during the times indicated. The infections were scored on a scale of 0 to 5 based on the following parameters: corneal infiltration, corneal neovascularization, and corneal ulceration. The pathology was recorded as 0 (no pathology), 1 (<10% of the cornea involved), 2 (10 to 25% involved), 3, (25 to 50% involved) 4, (50 to 75% involved), and 5 (75 to 100% involved), as described previously (17). Any animals receiving a score of at least 1.0 for any parameter were scored as infected. In Chinese hamsters, Acanthamoeba keratitis resolves at approximately day 21. At this time, there is a conspicuous absence of corneal opacity, edema, epithelial defects, and stromal necrosis and inflammation. Histological examination of eyes termed resolved have never shown any evidence of trophozoites nor cysts.

MIP-2 and myeloperoxidase (MPO) assays.

Corneas were removed from infected Chinese hamsters at designated times. All pieces of the limbus were removed, and the corneas were either immediately used or flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −70°C until tested.

For the detection of MIP-2, corneas were homogenized in 0.5 ml of RPMI 1640 and centrifuged at 10,000 × g for clarification, and protein levels were determined using a Quantikine M mouse MIP-2 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.). Corneas were removed on days 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6 postinfection (n = 3 for each time point). The data are expressed as total picograms of MIP-2 per cornea.

MPO activity was determined by the method of Bradley et al. (3). Animals were injected with recombinant MIP-2 (rMIP-2), anti-MIP-2, or control immunoglobulin G (IgG) as described below. Briefly, corneas from days 2 and 6 postinfection were individually homogenized in 0.5 ml of hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (0.5% in 50 mM phosphate buffer [pH 6.0]). The homogenate was then subjected to three freeze-thaw cycles and centrifuged at 40,000 × g for 20 min. After centrifugation, 0.2 ml of the supernatant was combined with 1.8 ml of 50 mM phosphate buffer (pH 6.0) containing 0.167 mg of o-dianisidine hydrochloride per ml and 0.0005% hydrogen peroxide. The change in absorbance was measured spectrophotometrically at 460 nm. One unit of MPO activity is defined as the amount degrading 1 μM peroxide per min at 25°C. Corneas were removed on days 2 and 6 postinfection (n = 3 for each treatment group on each day). The data are expressed as total units of MPO per cornea.

Anti-MIP-2 and rMIP-2 inoculations.

Goat anti-mouse MIP-2 antibody and mouse rMIP-2 were purchased from R&D Systems. All animals were treated simultaneously with injections and topical applications.

Anti-MIP-2 was administered via subconjunctival injection 4 h prior to infection. A solution of 3.33 μg of antibody in 40 μl of phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was injected encircling the entire subconjunctiva. Identical concentrations of antibody were then applied topically (under the lens) using sterile gel-loading pipette tips at 24, 48, and 72 h postinfection. Goat IgG (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) controls were administered as above at identical concentrations. In several in vivo experiments, the goat IgG was shown not to react with Acanthamoeba trophozoites nor to inhibit their binding to corneal epithelial cells (data not shown). Infections were performed in triplicate (n = 6 for each group).

rMIP-2 was administered via intracorneal injection. The corneal surface was first punctured with a 30-gauge stainless steel needle, and then the rMIP-2 was injected using a drawn glass needle attached to a syringe dispenser. A 1-μl solution of rMIP-2 in PBS containing 100 μg/μl was injected just prior to infection. Identical concentrations of protein were applied topically (under the lens) at 24, 48, and 72 h postinfection. Control animals were injected with 1 μl of PBS. Infections were performed twice (n = 8 in for each group).

Histological examination.

Infected eyes were removed and stored in 10% Carson's formalin for 24 h. Specimens were then embedded in paraffin, cut into 4-μm sections using a Reichert Histostat rotary microtome (Reichert Scientific Instruments, Buffalo, N.Y.), and placed on polysine hydrobromide-precoated slides (Polysciences, Warrington, Pa.). Sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin, covered with a coverslip, and examined by light microscopy. Pictures were taken by camera-enhanced light microscopy (BX50; Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan).

Production of anti-Chinese hamster neutrophil antisera.

For antibody production, two Chinese hamsters were injected with 2.5 ml of 3.0% thioglycolate intraperitoneally. Four hours after injection, hamsters were sacrificed and the peritoneal cavity was washed with 10 ml of Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS). The peritoneal exudate was layered onto 3 ml of Histopaque and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 15 min. The neutrophils were collected, suspended in 1 ml of HBSS, and immediately used for antibody generation. The initial injection of 106 neutrophils was mixed 1:1 with Freund's complete adjuvant (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) and administered intramuscularly into a New Zealand White rabbit. Additional injections were performed without adjuvant once a week for 6 weeks. Blood was collected from the ear veins of the rabbit starting 4 weeks after the initial injection. For serum preparation, blood was allowed to clot overnight at 4°C. Serum was then removed from the clot and centrifuged at 2,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. Control serum was collected from a naive rabbit by ear vein and processed as stated above. All sera were stored at −20°C.

Serum absorption.

Anti-Chinese hamster antiserum was absorbed as described by Sekiya et al. (35). Briefly, neutrophils were harvested by peritoneal lavage as described above and diluted to 2 × 107 cells/ml in HBSS supplemented with 0.1% bovine serum albumin (BSA). Additionally, spleen, thymus, and mesenteric lymph nodes were removed, strained through a sterile Falcon cell strainer (Becton Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, N.J.), and suspended in HBSS supplemented with 0.1% BSA at 2 × 107 cells/ml. Antiserum was absorbed extensively with hamster spleen, thymus, and mesenteric lymph node cells to remove antibodies against Chinese hamster histocompatibility and lymphoid antigens. The mixtures were then centrifuged at 1,700 × g for 10 min, and the antiserum was removed and tested for cytotoxicity (see below).

Complement-mediated cytotoxicity assay.

The cytolytic component of the absorbed antineutrophil serum was tested in a modified cytotoxicity assay (10). Antiserum was heat inactivated at 56°C for 1 h and diluted 1:50, 1:100, and 1:200 in HBSS supplemented with 0.1% BSA. Chinese hamster splenocytes, thymocytes, lymph node cells, and neutrophils were incubated for 1 h at 37°C in either antiserum or normal serum. Antiserum was removed by centrifugation, and the cells were then washed in HBSS-BSA. The cells were incubated in 1 ml of Low-Tox H rabbit complement (Accurate Chemical Co., Westbury, N.Y.) diluted 1:10 in HBSS-BSA and allowed to incubate for 30 min at 37°C. All cells were then washed three times and resuspended in 0.1 ml of HBSS-BSA, and cell viability was determined by trypan blue exclusion. The cytotoxic index was as [S (%) − SP (%)/100 − SP (%)] × 100, where S (%) is the percentage of cells that were stained in the presence of antiserum and complement and SP (%) is the percentage of cells spontaneously stained with complement alone.

Anti-Chinese hamster antibody inoculations.

The experiments were performed in two groups. Group 1 was administered 0.5 ml of absorbed serum injected intraperitoneally daily on days −3, −2, −1, 0, 1, 2, and 3 of infection. Group 2 was administered twice-daily injections of 0.5 ml of absorbed serum intraperitoneally along with topical applications of bacitracin (to prevent bacterial infection) for 14 days after infection. Infections were performed as described earlier (n = 6 for each group of animals in both experiments).

Statistics.

Statistical analyses of MIP-2 and MPO assays were performed using unpaired Student's t tests; results are presented as means ± standard errors (SE). Clinical severity scores were analyzed by the Mann-Whitney test.

RESULTS

Induction of MIP-2 production in infected Chinese hamster corneas and its role in recruiting neutrophils.

The presence of MIP-2 has been established in murine corneas infected with HSVK and Pseudomonas keratitis and in rat lipopolysaccharide inflammatory studies (33, 40, 50). However, before beginning in vivo studies in Chinese hamsters, it was important to determine whether and to what degree MIP-2 is produced in the Chinese hamster cornea. Infected corneas were removed on days 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6 postinfection and assessed for the presence of MIP-2 by ELISA.

Three days after infection, the corneas displayed a 2.6-fold increase in MIP-2 production (Fig. 1). This increase in production was sustained during the remaining days that were tested.

FIG. 1.

MIP-2 ELISA of Chinese hamster corneas infected with Acanthamoeba. Corneas were removed from three hamsters at the indicated times postinfection. Corneal lysates were individually prepared and assayed for MIP-2. The bars show means ± SE of three hamster corneas per time point. ∗∗∗, significantly different from uninfected control corneas (P < 0.001).

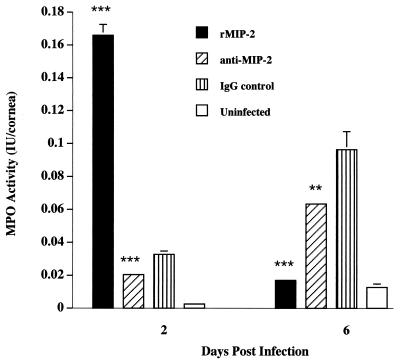

Corneas from similarly treated animals were examined to determine if the increased expression of MIP-2 induced the migration and accumulation of neutrophils. MPO is an enzyme specific for neutrophils and is an accurate reflection of the neutrophil content in tissues (4). The MPO assay was used to determine if rMIP-2 could stimulate neutrophil recruitment into corneas infected with Acanthamoeba trophozoites and if neutralization of endogenously produced MIP-2 would affect neutrophil infiltration in response to corneal infection.

The results indicated that intracorneal injection of rMIP-2 induced a fivefold increase in the MPO activity in infected hamsters compared to control hamsters treated with control IgG on day 2 postinfection (Fig. 2). However, by day 6, the MPO activity of the rMIP-2-treated group returned to baseline levels. These results demonstrate that MIP-2 is a potent chemoattractant for neutrophils in the Chinese hamster model.

FIG. 2.

MPO assay of Chinese hamster corneas infected with Acanthamoeba. Hamster corneas were injected with rMIP-2, anti-MIP-2, or control IgG and infected with Acanthamoeba trophozoites. Corneas were removed on days 2 and 6, and corneal lysates were individually prepared and assayed for MPO activity. Each bar represents the mean ± SE of three corneas per treatment on both days. ∗∗ and ∗∗∗, significantly different from IgG-treated corneas (P < 0.010 and P < 0.001, respectively).

To assess whether endogenous levels of MIP-2 were specifically responsible for recruiting neutrophils, animals were treated with anti-MIP-2 via subconjunctival injection and compared to similarly treated IgG control animals (Fig. 2). The efficacy of MIP-2 in inducing neutrophil infiltration was apparent, as there was a 30% decrease in the MPO activity in corneas from hamsters treated with anti-MIP-2 compared to the IgG group. Thus, a significant portion of neutrophil recruitment in Acanthamoeba keratitis is attributed to locally produced MIP-2.

In vivo effects of anti-MIP-2 and rMIP-2 treated animals.

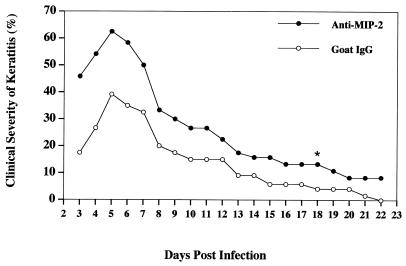

The functional capabilities of rMIP-2 and anti-MIP-2 at recruiting and inhibiting neutrophils, respectively, suggest that it would be possible to manipulate the clinical symptoms of the disease by altering the levels of neutrophil migration. To test this hypothesis, animals were treated with either anti-MIP-2 and goat IgG or rMIP-2 and PBS and infected as described above. The results shown in Fig. 3, typical for all three experiments involving anti-MIP-2, show that animals treated with anti-MIP-2 had a more severe and prolonged infection than control IgG-treated animals. At the peak of infection (day 6), the severity of corneal involvement in the anti-MIP-2-treated groups was significantly greater (P < 0.001) than in the IgG control group. Moreover, over 80% of the anti-MIP-2 treated animals still demonstrated evidence of corneal disease at day 18, compared to a 16% incidence of infection in the IgG animals.

FIG. 3.

In vivo effect of anti-MIP-2 treatment on the severity of Acanthamoeba keratitis in Chinese hamsters. Animals were subconjunctivally administered either anti-MIP-2 antibody or control IgG 4 h before infection. Identical concentrations of anti-MIP-2 and control IgG were administered topically on days 1 to 3 postinfection. Infected lenses were removed after 3 days, and corneas were scored for clinical severity for the period indicated. On day 18 (∗), five of six anti-MIP-2-treated animals but only one of six control animals still demonstrated evidence of disease. Each graph line represents the mean severity of six animals for the observed times. The results shown are representative of three separate experiments.

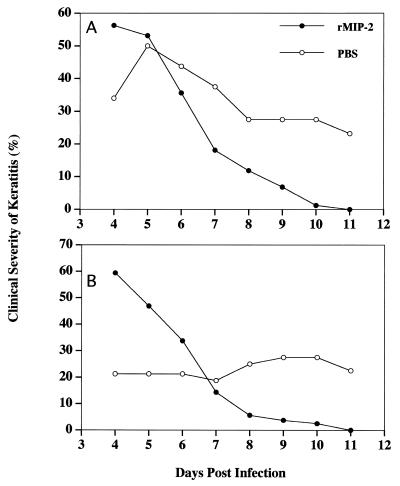

In contrast, rMIP-2-treated animals displayed a more severe clinical infection during the initial onset of the disease, yet the disease cleared rapidly (Fig. 4). In two independent experiments, intracorneal administration of rMIP-2 resulted in a much milder clinical course of Acanthamoeba keratitis and a rapid acceleration of the resolution of corneal disease.

FIG. 4.

In vivo effect of rMIP-2 treatment on the course of Acanthamoeba keratitis in Chinese hamsters. Animals were injected intracorneally with either rMIP-2 or PBS prior to infection. Identical concentrations of rMIP-2 and PBS were administered on days 1 to 3 postinfection. Infected lenses were removed after 4 days, and corneas were scored for clinical severity for the observation times indicated. The two graphs represent two separate experiments (n = 8 for each treatment group per experiment).

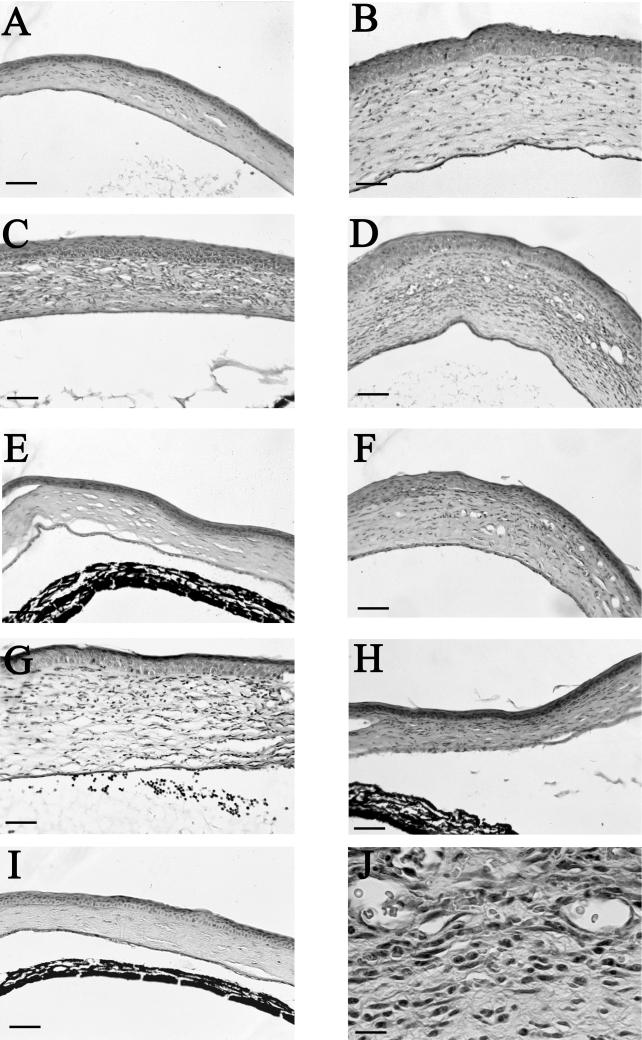

The histopathological features of the corneas from the various treatment groups mirrored the clinical observations and the MPO assays. Corneas removed from control animals exhibited mild corneal infections on day 3, peak infections on day 6, and the beginning of resolution on day 9 (Fig. 5A, C, and E). Corneas in the anti-MIP-2-treated groups displayed extensive pathological symptoms that exceeded those in the normal IgG treatment group at all time points examined. Corneas removed from anti-MIP-2-treated animals on day 3 displayed little polymorphonuclear cell (PMN) involvement, yet stromal thickening was present (Fig. 5B). By day 6, anti-MIP-2-treated animals exhibited severe corneal infections including increased vascularization and stromal destruction (Fig. 5D). Histological examination and MPO assays showed little migration of neutrophils (Fig. 5J). On day 9, corneal infections were still more severe than in control animals (Fig. 5F). In contrast, corneas treated with rMIP-2 were heavily infiltrated with neutrophils and displayed intense stromal thickening immediately on day 3 (Fig. 5B). The neutrophil infiltration was present both in the stroma and in the anterior chamber. Six days postinfection, the number of neutrophils in the stroma had declined and the anterior chamber was clear of neutrophils; by day 9, the corneas had returned to normal, with little microscopic evidence of corneal inflammation (Fig. 5H and I). Histological examination of eyes injected either intracorneally with PBS or subconjunctivally with goat IgG failed to show a significant increase in neutrophil migration compared to untreated contols (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Photomicrographs of corneas from Chinese hamsters untreated, treated with anti-MIP-2 antibody or rMIP-2, and challenged with amoeba-laden contact lenses. Eyes were removed from untreated (A, C, and E), anti-MIP-2-treated (B, D, F, and J), and rMIP-2-treated (G to I) animals on days 3, 6, and 9 postinfection. Untreated corneas displayed mild corneal swelling and few PMN at day 3 postinfection (A). On day 6, extensive corneal swelling and neutrophils were present in the stroma (C). By day 9, the corneal edema and swelling had subsided (E). Anti-MIP-2-treated corneas on day 3 displayed significant corneal swelling, edema, and plasma cells, with few macrophages and PMN in the stroma (B). At day 6, the extensive corneal swelling persisted while general stromal inflammation increased (B). At higher magnification, the cornea reveals a high preponderance of mononuclear cells (J). Note the persistence of stromal swelling and edema on day 9 postinfection (F). rMIP-2-treated animals displayed the greatest stromal swelling and PMN infiltration at day 3 in both the stroma and anterior chamber (G). By day 6, PMN infiltration and corneal swelling were significantly reduced (H). The stromal swelling and edema had subsided by day 9 postinfection (I). A to I, bars = 70 μm; J, bar = 25 μm.

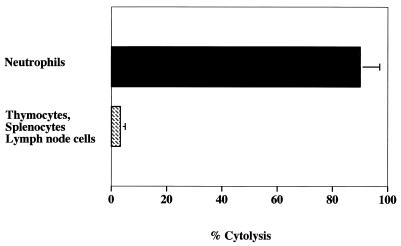

Antibody-mediated complement lysis of Chinese hamster neutrophils.

A cytolytic antibody to Chinese hamsters was generated as a tool for depleting neutrophils and confirming the role of neutrophils in Acanthamoeba keratitis. A rabbit polyclonal antibody was generated by repeated intramuscular injections of Chinese hamster neutrophils as described in Materials and Methods. The antiserum was exhaustively absorbed with Chinese hamster spleen, thymus, and lymph node cells. In the presence of complement, the anti-Chinese hamster neutrophil antiserum (1:50) produced 85% lysis of Chinese hamster neutrophils without demonstrating measurable toxicity to splenocytes, thymocytes, or lymph node cells (Fig. 6). Similar results were seen at 1:100 and 1:200 dilutions (data not shown).

FIG. 6.

Cytolytic activity of absorbed anti-Chinese hamster neutrophil antibody on neutrophils, thymocytes, splenocytes, and lymph node cells. Neutrophils were harvested by peritoneal lavage. Neutrophils, thymocytes, splenocytes, and lymph node cells (2 × 106) were incubated with 1:50 diluted absorbed antiserum. Cytotoxicity was assessed by trypan blue exclusion. Each bar shows the mean ± SE of triplicate counts.

In vivo effects of anti-Chinese hamster neutrophil antiserum on the severity of Acanthamoeba keratitis.

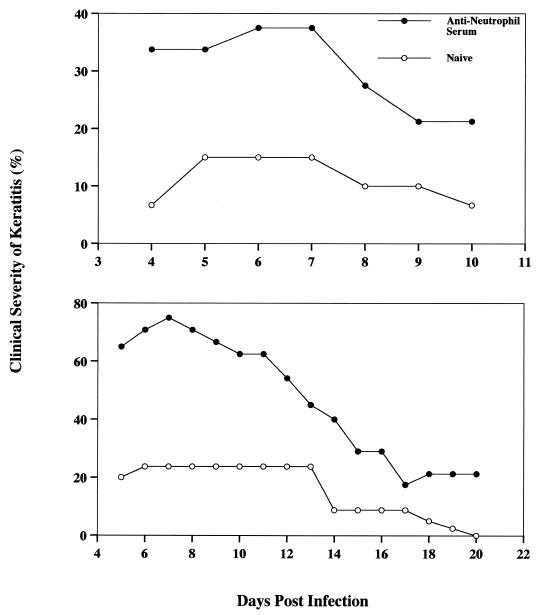

Having confirmed the potency of the rabbit anti-Chinese hamster neutrophil antiserum in vitro, we next examined the effect of neutrophil depletion on the clinical course of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Chinese hamsters were injected intraperitoneally with 1 ml of either antineutrophil antiserum or normal rabbit serum 3 days before corneal infection. Antiserum injections resulted in a 60% decrease of differential leukocytes in peripheral blood without reducing lymphocyte or monocyte counts after 5 h (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 7, animals treated with single daily injections developed infections that were over twice as severe as those in control animals. The experiment was terminated after day 10 because some animals in the anti neutrophil-treated group began to show symptoms of bacterium-induced keratitis. Corneas displaying bacterial infections were swabbed and cultured on blood agar plates (Remel, Lenexa, Kans.) for confirmation of bacterial keratitis and ascertained to be infected with Staphylococcus. Since neutrophil regeneration is extremely rapid, a second experiment was performed using two daily injections of antineutrophil antiserum along with topical applications of bacitracin to prevent bacterial growth. As before, treatment with the antiserum exacerbated the severity of the corneal infections (Fig. 7). In this case, the severity was approximately three times higher than in the normal rabbit serum controls. Although corneal infections resolved in all of the control hamsters, keratitis persisted throughout the entire observation period in the antineutrophil-treated animals.

FIG. 7.

In vivo effect of anti-Chinese hamster neutrophil antibody treatment on severity of Acanthamoeba keratitis in Chinese hamsters. Hamsters (n = 6 for each group) were administered peritoneal injections of either antineutrophil antiserum or naive rabbit serum 3 days pre- or post-infection either once (top) or twice (bottom) daily. Infected lenses were removed 4 days postinfection, and corneas were evaluated for clinical severity for the observation times indicated. Animals were given single daily injections of anti-Chinese hamster neutrophil antiserum (top). The experiment was terminated at day 10 due to the emergence of bacterial keratitis in the antiserum group. Animals were given twice-daily injections of anti-Chinese hamster neutrophil antiserum (bottom). Bacitracin was administered topically for 14 days to prevent bacterial keratitis.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to determine the role of neutrophils in Acanthamoeba keratitis by selective inhibition of neutrophil migration in the cornea through anti-MIP-2 antibody treatment and by elimination of neutrophils by anti-hamster neutrophil antiserum treatment. Moreover, the contribution of MIP-2 in migration of neutrophils into the cornea of Chinese hamsters infected with Acanthamoeba was examined. The results showed that high levels of MIP-2 were initially produced 3 days postinfection and maintained during the time points evaluated (day 6). The production of MIP-2 correlated with the migration of neutrophils as shown by histology, clinical examination, and MPO activity. Yan et al. (50) reported that MIP-2 is the predominant chemokine that stimulates the accumulation of the neutrophils in the mouse cornea after herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. Our results showed that the kinetics of MIP-2 production are different from those reported with herpesvirus infection and may be related to differences in the immune responses to the pathogens. Repeated subconjunctival injections of anti-MIP-2 antibody had a profound effect on Acanthamoeba keratitis. Instead of mitigating corneal disease as it does in HSVK, anti-MIP-2 treatments resulted in more severe keratitis and a prolonged course of infection. The increased severity of Acanthamoeba keratitis in anti-MIP-2-treated hamsters was due to a significant decrease in neutrophil infiltration, as demonstrated by MPO assays on the corneal buttons from infected hamsters treated with anti-MIP-2 but not in hamsters treated with an IgG control antibody. The profound exacerbation of Acanthamoeba keratitis in hamsters treated with mouse anti-MIP-2 antibody suggests that neutrophils play an important role in controlling corneal infection with Acanthamoeba trophozoites.

If neutrophils are important in the resolution of Acanthamoeba keratitis, then depletion of the host neutrophil population should exacerbate corneal disease. By contrast, if neutrophils contribute to the pathogenesis of Acanthamoeba keratitis, one would expect neutrophil depletion to mitigate corneal disease. Again, depletion of neutrophils with anti-Chinese hamster neutrophil antibody resulted in more severe keratitis, as well as prolonged and more chronic keratitis. The most likely explanation for the exacerbation of Acanthamoeba keratitis in Chinese hamsters treated with either anti-MIP-2 antibody or antineutrophil antibody is that neutrophils act as a first line of defense and destroy significant numbers of the amoebae. Therefore, the absence of neutrophils in the cornea may allow invasion of Acanthamoeba into the cornea, which induces more severe keratitis. In this regard, in vitro studies demonstrated that neutrophils are capable of killing Acanthamoeba trophozoites (37). Unlike HSVK and Pseudomonas keratitis, where the inhibited migration of neutrophils by anti-mouse MIP-2 antibody ameliorated the clinical symptoms, neutrophils seem to be important in resolving Acanthamoeba keratitis (33, 50).

The more severe keratitis in anti-MIP-2 and antineutrophil antibody-treated hamsters suggested that neutrophils clearly have a protective role in Acanthamoeba keratitis. We suspected that if we induced neutrophil migration into the cornea prior to infection with Acanthamoeba trophozoites, animals would experience milder keratitis. Injection of recombinant mouse MIP-2 into the cornea resulted in an initial increase in corneal inflammation but ultimately caused a more rapid resolution of keratitis than in PBS-treated hamsters. Moreover, induction of neutrophil infiltration was confirmed histologically and by MPO assay. The initial intense inflammation would be expected with a large population of neutrophils degranulating into the local tissue. This increase in MPO, as well as other neutrophil products, may be responsible for the killing of the trophozoites, thus limiting the course of the disease in corneas of animals treated with rMIP-2 compared with those of PBS-treated animals. We suspect that other phagocytic cells, such as macrophages, influence the incidence and severity of Acanthamoeba keratitis in MIP-2-treated animals. In contrast with our findings, other blinding infectious diseases such as HSVK and Pseudomonas keratitis have a much milder course of the disease after anti-MIP or antineutrophil treatment (33, 50). These findings are important because HSVK and Pseudomonas keratitis are immune-mediated diseases whereas Acanthamoeba keratitis is not. We previously showed that depletion of conjunctival macrophages using liposomes containing the macrophagicidal drug dichloromethylene diphosphate exacerbated the severity and chronicity of Acanthamoeba keratitis in Chinese hamsters (43). By contrast, activation of the adaptive immune response in the form of Acanthamoeba-specific delayed-type hypersensitivity and anti-Acanthamoeba IgG serum antibodies fails to alter the incidence, severity, or chronicity of Acanthamoeba keratitis in either the pig or Chinese hamster model of the disease (27). These results, along with present findings demonstrating the importance of neutrophils, indicate that the innate immune system plays an important role in controlling Acanthamoeba keratitis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant EY09756 from the National Institutes of Health, NIAID molecular microbiology training grant AI07520, and an unrestricted grant from Research to Prevent Blindness, Inc., New York, N.Y.

We thank Robert Lausch, George Stewart, and Kathleen Alford for assistance with the MPO assay, Elizabeth Mayhew for histology, Darrell Conger and William Anderson for photographic services, and Steve Fisher and Al Molai for technical assistance with graphic arts.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alizadeh H, Niederkorn J Y, McCulley J. Acanthamoeba keratitis. In: Pepose J S, Holland G N, Wilhelmus K R, editors. Ocular infection and immunity. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 1996. pp. 1062–1071. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auran J D, Starr M B, Jacobiec F A. Acanthamoeba keratitis. Cornea. 1987;6:2–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bradley P, Christensen R, Rothstein G. Cellular and extracellular myeloperoxidase in pyrogenic inflammation. Blood. 1982;60:618–625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradley P P, Priebat D A, Christensen R D, Rothstein G. Measurement of cutaneous inflammation: estimation of neutrophil content with an enzyme marker. J Investig Dermatol. 1982;78:206–209. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12506462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown T J, Cursons R T M, Keys E A. Amoeba from antarctic soil and water. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1982;44:491–493. doi: 10.1128/aem.44.2.491-493.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cerva L, Serbus C, Skocil V. Isolation of limax amoeba from the nasal mucosa of man. Folia Parasitol. 1973;20:97–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centers for Disease Control. Acanthamoeba keratitis in soft-contact-lens wearers–United States. Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 1987;36:397–398. , 403–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Garner A. Pathology of Acanthamoeba infection. In: Cavanagh H D, editor. The cornea: Transactions of the World Congress on the Cornea III. New York, N.Y: Raven Press; 1988. pp. 535–539. [Google Scholar]

- 9.He Y G, McCulley J P, Alizadeh H, Pidherny M S, Mellon J, Ubelaker J E, Stewart G L, Silvany R E, Niederkorn J Y. A pig model of Acanthamoeba keratitis: transmission via contaminated lenses. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33:126–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He Y G, Niederkorn J Y. Depletion of donor-derived Langerhans cells promotes corneal allograft survival. Cornea. 1996;15:82–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He Y G, Niederkorn J Y, McCulley J P, Stewart G L, Meyer D R, Silvany R E. In vivo and in vitro collagenolytic activity of Acanthamoeba castellanii. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990;31:2235–2240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kernacki K A, Barrett R P, Hobden J A, Hazlett L D. Macrophage inflammatory protein-2 is a mediator of polymorphonuclear neutrophil influx in occular bacterial infection. J Immunol. 2000;164:1037–1045. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.2.1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kernacki K A, Barrett R P, McClellan S A, Hazlett L D. Aging and PMN response to P. aeruginosa infection. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:3019–3025. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kingston D, Warhurst D C. Isolation of amoebae from the air. J Med Microbiol. 1969;2:27–36. doi: 10.1099/00222615-2-1-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwon B, Hazlett L D. Association of CD4+ T cell-dependent keratitis with genetic susceptibility to Pseudomonas aeruginosa keratitis. J Immunol. 1997;159:6283–6290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Larkin D F P, Easty D L. Experimental Acanthamoeba keratitis. II. Immunological evaluation. Br J Ophthalmol. 1991;75:421–424. doi: 10.1136/bjo.75.7.421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leher H, Kinoshita K, Alizadeh H, Zaragoza F L, He Y G, Niederkorn J Y. Impact of oral immunization with Acanthamoeba antigens on parasite adhesion and corneal infection. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:2337–2343. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Leher H F, Silvany R E, Alizadeh H, Huang J, Niederkorn J Y. Mannnose induces the release of cytopathic factors from Acanthamoeba castellanii. Infect Immun. 1998;66:5–10. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.1.5-10.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lyons T B, Kapur R. Limax amoeba in public swimming pools of Albany, Schenectady, and Ransselear Counties, New York: their concentrations, correlations, and significance. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1977;2:27. doi: 10.1128/aem.33.3.551-555.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mathers W D, Stevens G, Rodrigues M, Chan C C, Gold J, Visvesvara G S, Lemp M A, Zimmerman L Z. Immunopathology and electron microscopy of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1987;103:626–635. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)74321-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathers W D, Sutphin J E, Folberg R, Meier P A, Wenzel R P, Elgin R G. Outbreak of keratitis presumed to be caused by Acanthamoeba. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;121:207–208. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70577-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCulley J P, Alizadeh H, Niederkorn J Y. Acanthamoeba keratitis. CLAO J. 1995;21:73–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller M D, Krangel M S. Biology and biochemistry of the chemokines: a family of chemotactic and inflammatory cytokines. Crit Rev Immunol. 1992;12:17–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitro K, Bhagavathiamai A, Zhou O-M, Bobbett G, McKerrow J H, Chokshi R, Chokshi B, James E F. Partial characterization of the proteolytic secretions of Acanthamoeba polyphaga. Exp Parasitol. 1994;78:377–385. doi: 10.1006/expr.1994.1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morton L D, McLaughlin G L, Whiteley H E. Effects of temperature, amebic strain, and carbohydrates on Acanthamoeba adherence to corneal epithelium in vitro. Infect Immun. 1991;59:3819–3822. doi: 10.1128/iai.59.10.3819-3822.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niederkorn J Y. Immunological barriers in the eye. In: Goldie R, editor. The handbook of immunopharmacology. Immunopharmacology of epithelial barriers. London, England: Academic Press; 1994. pp. 241–254. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niederkorn J Y, Alizadeh H, Leher H F, McCulley J P. The immunobiology of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 1999;21:147–160. doi: 10.1007/BF00810247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Niederkorn J Y, Ubelaker J E, McCulley J P, Stewart G L, Meyer D R, Mellon J A, Silvany R E, He Y G, Pidherney M, Martin J H, Alizadeh H. Susceptibility of corneas from various animal species to in vitro binding and invasion by Acanthamoeba castellanii. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1992;33:104–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pazko-Kolva C, Yamamoto H, Shahamat M, Sawyer T K, Morris G, Colwell P R. Isolation of amoeba and Pseudomonas and Legionella spp. from eyewash stations. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1991;57:163–167. doi: 10.1128/aem.57.1.163-167.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pearlman E. Immunopathology of onchocerciasis: a role for eosinophils in onchocercal dermatitis and keratitis. Chem Immunol. 1997;66:26–40. doi: 10.1159/000058664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pettit D A, Williamson J, Cabral G A, Marciano-Cabral F. In vitro destruction of nerve cell cultures by Acanthamoeba spp.: a transmission and scanning electron microscopy study. J Parasitol. 1996;82:769–777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rivera F, Medina F, Ramirez P, Alcocer J, Vilaclara G, Robles E. Pathogenic and free-living protozoa cultured from the nasopharyngeal and oral regions of dental patients. Environ Res. 1984;33:428–440. doi: 10.1016/0013-9351(84)90040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rudner X L, Kernacki K A, Barrett R P, Hazlett L D. Prolonged elevation of IL-1 in Pseudomonas aeruginosa ocular infection regulates macrophage-inflammatory protein-2 production, polymorphonuclear neutrophil persistence, and corneal perforation. J Immunol. 2000;164:6576–6582. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schall T J, Bacon K B. Chemokine, leukocyte trafficking, and inflammation. Curr Opin Immunol. 1994;6:865–873. doi: 10.1016/0952-7915(94)90006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sekiya S, Gotoh S, Yamashita T, Watanabe T, Saitoh S, Sendo F. Selective depletion of rat neutrophils by in vivo administration of a monoclonal antibody. J Leukoc Biol. 1989;46:96–102. doi: 10.1002/jlb.46.2.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Stehr-Green J K, Baily T M, Visvesvara G S. The epidemiology of Acanthamoeba keratitis in the United States. Am J Ophthalmol. 1989;107:331–336. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(89)90654-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Stewart G L, Shupe K, Kim I, Silvany R E, Alizadeh H, McCulley J P, Niederkorn J Y. Antibody-dependent neutrophil-mediated killing of Acanthamoeba castellanii. Int J Parasitol. 1994;24:739–742. doi: 10.1016/0020-7519(94)90129-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Streilein J W, Dana M R, Ksander B R. Immunity causing blindness: five different paths to herpes stromal keratitis. Immunol Today. 1997;18:443–449. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)01114-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Thomas J, Gangappa S, Kanangat S, Rouse B T. On essential involvement of neutrophils in the immunopathological disease: herpetic stromal keratitis. J Immunol. 1997;158:1383–1391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vaddi K, Keller M, Newton R C. The chemokine factsbook. San Diego, Calif: Academic Press, Inc.; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Van Klink F, Alizadeh H, He Y G, Mellon J A, Silvany R E, McCulley J P, Niederkorn J Y. The role of contact lenses, trauma, and Langerhans cells in the Chinese hamster model of Acanthamoeba keratitis. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1993;34:1937–1944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Van Klink F, Leher H F, Jager M J, Alizadeh H, Taylor W, Niederkorn J Y. Systemic immune response to Acanthamoebia keratitis in the Chinese hamster. Ocular Immunol Inflamm. 1997;5:234–244. doi: 10.3109/09273949709085064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Van Klink F, Taylor W M, Alizadeh H, Jager M J, Van Rooijen N, Niederkorn J Y. The role of macrophages in Acanthamoeba keratitis. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:1271–1281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Visvesvara G S, Mirra S S, Brandt F H, Moss D M, Mathews H M, Martinez A J. Isolation of 2 strains of Acanthamoeba castellanii from human tissue and their pathogenicity and isoenzyme profiles. J Clin Microbiol. 1983;6:1405–1412. doi: 10.1128/jcm.18.6.1405-1412.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Visvesvara G S, Stehr-Green J K. Epidemiology of free-living amoeba infections. J Protozool. 1990;37:25s–33s. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1990.tb01142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang S S, Feldman H A. Isolation of Hartmannella species from human throats. N Engl J Med. 1967;277:1174–1179. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196711302772204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Watanabe K, Iida M, Takaishi K, Suzuki T, Hamada Y, Iizuka Y, Tsurufuji S. Chemoattractants for neutrophils in lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammatory exudate from rats are not interleukin-8 counterparts but gro-gene-product/melanoma-growth-stimulating-activity-related factors. Eur J Biochem. 1993;214:267–270. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb17920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wolpe S D, Davatelis G, Sherry B, Beutler B, Hesse D G, Nguyen H T, Moldawer L L, Nathan C F, Lowry S F, Cerami A. Macrophages secrete a novel heparin-binding protein with inflammatory and neutrophil chemokine properties. J Exp Med. 1988;167:570–581. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.2.570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wolpe S D, Sherry B, Juers D, Davatelis G, Yurt R W, Cerami A. Identification and characterization of macrophage inflammatory protein 2. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:612–616. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yan X T, Tumpey T M, Kunkel S L, Oakes J E, Lausch R N. Role of MIP-2 in neutrophil migration and tissue injury in herpes simplex virus-1-infected cornea. Investig Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:1854–1862. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yang Z T, Cao Z Y, Panjwani N. Pathogenesis of Acanthamoeba keratitis-carbohydrate-mediated host-parasite interactions. Infect Immun. 1997;65:439–445. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.439-445.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]