Abstract

Lead (Pb) is considered to be a major environmental pollutant and occupational health hazard worldwide which may lead to neuroinflammation. However, an effective treatment for Pb-induced neuroinflammation remains elusive. The aim of this study was to investigate the mechanisms of Pb-induced neuroinflammation, and the therapeutic effect of sodium para-aminosalicylic acid (PAS-Na, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug) in rat cerebral cortex. The results indicated that Pb exposure induced pathological damage in cerebral cortex, accompanied by increased levels of inflammatory factors tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β). Moreover, Pb decreased the expression of silencing information regulator 2 related enzyme 1 (SIRT1) and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), and increased the levels of high mobile group box 1 (HMGB1) expression and p65 nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) phosphorylation. PAS-Na treatment ameliorated Pb-induced histopathological changes in rat cerebral cortex. Moreover, PAS-Na reduced the Pb-induced increase of TNF-α and IL-1β levels concomitant with a significant increase in SIRT1 and BDNF levels, and a decrease in HMGB1 and the phosphorylation of p65 NF-κB expression. Thus, PAS-Na may exert anti-inflammatory effects by mediating the SIRT1/HMGB1/NF-κB pathway and BDNF expression. In conclusion, in this novel study PAS-Na was shown to possess an anti-inflammatory effect on cortical neuroinflammation, establishing its efficacy as a potential treatment for Pb exposures.

Keywords: Lead, PAS-Na, SIRT1/HMGB1/NF-κB pathway, BDNF, Neuroinflammation

1. Introduction

Lead (Pb) is one of the most common non-essential toxic heavy metals in global environmental pollutants and can enter the human body through various sources and pathways, such as the air, food, dust, soil and water, etc [1]. Pb toxicity can affect multiple organ systems, such as the cardiovascular, urinary, nerve, bone, blood, immune, respiratory, gastrointestinal, reproductive and endocrine systems [2]. In particular, Pb readily crosses the blood–brain barrier and accumulates in neurons and glial cells, causing central nervous system (CNS) damage [3]. Occupational exposure to Pb has been shown to be associated with longitudinal decline in cognitive function and may increase the risk for developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Parkinson’s disease (PD) [4]. Moreover, low-level environmental Pb exposure can lead to intellectual deficits in children [5]. The current safe reference level of blood Pb set by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is 5 μg/dL, while levels of blood Pb below 3 μg/dL have been shown to elicit diminished cognitive function and maladaptive behavior in humans and animal models [6]. Moreover, Pb can accumulate and concentrate in the brain[7–9]. Studies have shown that the accumulation of Pb in cerebral cortex impairs cortical neuronal function and then affects cognitive function [10]. Although studies on Pb neurotoxicity have been carried out for decades, the precise mechanisms of Pb neurotoxicity have yet to be fully characterized.

Currently, the mechanism of Pb-induced neurotoxicity has been considered to be related to oxidative stress [11], apoptosis [12], autophagy dysregulation [11], epigenetic changes [13], neuroinflammation [14], to name a few. In particular, neuroinflammation causes neural cell death and irreversible damage to peripheral neurons, which is inseparable from the occurrence and development of AD [15]. Several lines of evidence using genetic and pharmacological manipulations indicate that the potent inflammatory cytokine like interleukin-1 beta (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) exacerbates both amyloid beta (Aβ) and tau pathologies in AD [15, 16]. According to epidemiological investigations, serum levels of inflammatory factors such as IL-1β, TNF-α, IL-6 and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in individuals exposed to Pb are higher than those in individuals without exposure [17, 18]. Moreover, the increase in intracellular inflammatory factors IL-1β and TNF-α induced by Pb exposure were thought to be related to Pb-induced cognitive impairment in animals [14, 19]. Therefore, inhibiting excessive neuroinflammation caused by Pb exposure might afford an effective means for antagonizing Pb neurotoxicity.

It is well known that silencing information regulator 2 related enzyme 1 (sirtuin1, SIRT1), a nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+)-dependent enzymes that plays a critical regulatory role in a variety of physiological and pathological processes, including autophagy, energy metabolism, apoptosis, oxidative stress, inflammatory response and cellular aging [20, 21]. Recent studies have established the protective effects of SIRT1 in neuroinflammation-related CNS diseases [21]. Of note, SIRT1 mediates the deacetylation of high mobile group box 1 (HMGB1), which is considered to be the central component of late inflammatory response proteins. The release of HMGB1 is triggered directly by the nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway upon its nuclear translocation. In response, cells release large numbers of inflammatory cytokines initiating a cascade amplification of inflammatory responses [22]. Pb exposure has been shown to down-regulate the expression of SIRT1 phosphorylation, and reduce the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), which plays an important role in regulating neuronal synapses growth, development, differentiation and plasticity in the cerebral hippocampus, leading to cognitive impairment in animals [23, 24]. However, whether Pb-induced neurotoxicity is caused by the SIRT1-mediated HMGB1/NF-κB inflammation pathway has yet to be determined.

Sodium para-aminosalicylic acid (PAS-Na) is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug used as an anti-tuberculosis drug in the early clinical stage, which can cross the blood-brain barrier to exert therapeutic effects. After the 1970s, in vivo studies and clinical studies have shown that para-aminosalicylic acid (PAS) as well as its salicylates PAS-Na has the effect of preventing and treating manganese poisoning in animals and manganesm patients [25–27]. In vivo findings suggest that PAS-Na alleviated Mn-induced neurotoxicity by inhibiting inflammation, oxidative stress, cells apoptosis and restoration of amino acid neurotransmitter homeostasis [25, 28, 29]. Furthermore, results of in vitro study showed that PAS-Na can inhibit manganese-induced pyroptosis, inflammatory response and oxidative stress in cells [25, 30]. In addition, we found that PAS-Na shows efficacy against Pb-induced pathological changes in hippocampal ultrastructure, showing for the first time, the potential of PAS-Na to afford protective effect against Pb-induced neuronal damage [31]. Moreover, PAS-Na has been found to ameliorate Pb-induced hippocampal neurons and PC12 cells apoptosis by inhibiting the activation of IP3R-Ca2+-ASK1-p38 signaling pathway and enhancing glutathione levels, respectively [32, 33]. In our recently in vivo study, we found that PAS-Na ameliorated Pb-induced cognitive impairment of rats by reducing inflammatory factor IL-1β levels through the ERK1/2-p90RSK/NF-κB pathway in the hippocampus [14]. However, whether PAS-Na affects Pb-induced neuroinflammation in the cerebral cortex has yet to be determined. Therefore, this study employed both in vivo and in vitro experiments to investigate whether PAS-Na can suppress Pb-induced inflammation in the cerebral cortex through the SIRT1/HMGB1/NF-κB pathway.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals and experimental design

Eight-week-old specific pathogen-free grade male Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats were purchased from Experimental Animal Center of Guangxi Medical University. All animal procedures were performed strictly accordance with international animal care guidelines standards. All experimental operations have been authorized by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Guangxi Medical University [Approval ID: SCXK (Gui) 2014–0002].

All rats were housed under a constant environment with adequate temperature (22 ± 2 °C), 45–65% humidity and a light/dark cycle of 12h/12h. Animals access to water and food ad libitum. After adaption for one week, the animals were randomly divided into 6 groups (n=12): control, Pb-treated, Pb+ Low (L)-PAS, Pb+ Medium (M)-PAS, Pb+ High (H)-PAS and PAS-Na control (C-PAS) groups. The rats in Pb-treated, Pb+ (L, M, H)-PAS groups received intraperitoneally (i.p.) injection with 6 mg/kg lead acetate (Sigma, USA) once a day, 5 days per week for 4 weeks, while rats in the control and C-PAS group were i.p. injected with sterile physiological saline. Next, rats in Pb+ (L, M, H)-PAS and C-PAS) groups received back subcutaneous(s.c.) injection of 100, 200, 300 and 300 mg/kg PAS-Na (Sigma, USA), respectively, once a day, 5 days per week for 3 weeks, while control and Pb-treated groups received back s.c. injection with the same volume of sterile physiological saline. The Pb exposure dose selected for the in vivo experiments was based on a previous study that intraperitoneal injection of 6 mg/kg lead acetate in rats for 5 weeks resulted in ultrastructural damage in the hippocampus [31]. The treatment dose and duration of PAS-Na were chosen because 100, 200 or 300 mg/kg PAS-Na treatment for 3 or 6 weeks significantly attenuated Pb-induced hippocampal injury and reduced manganese-induced NLRP3 inflammasome-dependent pyroptosis [25, 31]. At the end of the experiment, the rats were anesthetized by i.p. injection of 10% chloral hydrate (3.5 ml/kg) and sacrificed. The brain tissue was dissected on ice, and the cerebral cortices were collected and stored at − 80 °C.

2.2. Determination of Pb levels in cortex

Approximately 50 mg of the cortex was weighed and digested in 4 mL of 65% nitric acid (Merck ppb, USA) in 180 ◦ C for 15 min using a high-throughput closed microwave digestion instrument (CEM, USA). After the digested samples were cooled to room temperature, they were placed on a graphite heating plate (Botong Chemical Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) to evaporate until about 0.5–1 mL of liquid remained. Then the samples were made up to 5ml with double distilled water. Pb concentrations of cerebral cortex were determined by electrothermal atomic absorption spectrometry (AAnalyst800, PerkinElmer, USA) with ICE 3000 spectrometers (Thermo Fisher, USA) using a Zeeman background correction. The parameters were set as follows: analysis wavelength 283.3 nm, slit 0.7 nm and carrier gas argon (Ar).

2.3. Primary cortical neurons culture and treatments

Primary cortical neurons were cultured based on a previously published protocol [34]. Briefly, cerebral hemispheres were removed from rat fetuses (embryonic day 18). The superficial vessels and the meninges of cortical tissues were carefully isolated. Then, the cortex was chopped and digested in papain (Worthington, USA) for 30 min in 37°C. The dissociated neurons were collected and resuspended in the culture medium containing 84% MEM (Gibco, USA), 10% horse serum (Hyclone, USA), 5% glucose (Sigma-Aldrich, USA), 1% Glutamax (Gibco, USA). The resuspended cell were plated in poly-L-lysine-coated culture flasks at a density of 3~5 × 105 cells/cm2 and cultured at 5% CO2 cell incubator in 37°C. After 2–4h, the medium was replaced as the neurobasal medium (Gibco, USA) supplememted with 2% B-27 (Gibco, USA), 1% Glutamax (Gibco, USA) and 0.5% 100 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin (Solarbio, Beijing, China). Routinely, half of the volume of the medium was changed every 3 days. The cortical neurons were mature at 7 days and used for experiments. To obtain PAS-Na treatment models, the primary cortical neurons were exposed to 50 μM lead acetate for 24 h, then the neurons were treated with 100, 200 or 400 μM PAS-Na for another 24 h. The Pb exposure dose and duration was selected according to our previous work that 50 μM Pb exposure for 24 h significantly increased hippocampal neuronal apoptosis in vitro [32]. The SIRT1 inhibitor EX527 (MCE, USA) was added into the wells 2 h before Pb treatment.

2.4. Histopathological staining

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining procedure was performed to observe morphological and cellular changes in cerebral cortex. The specific operation steps of histopathological staining refer to our previous research [14].

2.5. Immunohistochemistry

The cortical tissue sections were placed in 60 °C oven for 2 h and then deparaffinized in xylene and dehydrated through graded concentrations of ethanol. Sections antigen retrieval in 0.01 M citrate buffer for 15 min. After blocking of endogenous peroxidase activity with 3% hydrogen peroxide, the non-specific binding was blocked with 5% goat serum for 1 h at room temperature. Then the slices incubated with primary antibodies of SIRT1(1:400, CST, USA, #9475) and NF-κB (1:1600, CST, USA, #3033) overnight at 4 °C. Sections were washed with TBST three times and incubated with an anti-rabbit polyclonal antibody for 20 min at room temperature. Next, the sections were stained with diaminobenzidine (DAB) and counterstained with hematoxylin. Finally, the sections were sealed by neutral gum. Images were captured with an EVOS Cell Imaging System.

2.6. Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence staining was used for the assessment of the changes of BDNF expression in cortical neurons. The immunofluorescence staining method and sample processing described previously were used [25]. For primary cultured cortical neurons, anti-BDNF (1:500, Abcam, UK, ab108319) and Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:1000, CST, USA, #4412) was used to mark neurons. To determine the levels of BDNF expression in cortical tissue sections, we double-labeled sections of cerebral cortex. The slices were incubated with primary antibodies of BDNF (1:200, Servicebio, China, GB11559) at 4 °C overnight. Then the sections were incubated with Cy3- conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (1:300, Servicebio, China, GB21303) for 1 h at room temperature. Finally, nuclei were counterstained with DAPI. Images were obtained with an EVOS Cell Imaging System.

2.7. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)

For the primary cortical neurons, cell lysates were mechanically collected and stored at −80°C. Total protein of cortical tissues was extracted according to previous studies [25]. The levels of IL-1β and TNF-α were measured by ELISA kits (Elabscience, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and then normalized by total protein with BCA Protein Assay Kit (Beyotime, China).

2.8. Western blotting

Total proteins of primary cortical neurons and cortex tissues were extracted using RIPA lyses buffer (CWBIO, China) containing protease inhibitor (Roche, USA) and phosphatase inhibitor (Roche, USA). Protein quantification was performed with an BCA Protein Assay kit (Beyotime, China).The protein samples (40 μg) were separated on 8% or 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels and electrophoretically transferred into polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (PVDF, 0.22 μm, Roche, USA). After blocking with 5% bovine serum albumin (Beyotime, China) for 1h at room temperature, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies overnight at 4 °C, including rabbit anti-SIRT1 (1:1000, CST, USA, #9475), HMGB1 (1:10000, Abcam, UK, ab79823), NF-κB P65 (1:1000, CST, USA, #8242), NF-κB P-P65 (1:1000 CST, USA, #3033), GAPDH (1:1000, CST, USA, #5174). Then, the membranes were incubated with anti- rabbit IgG (1:5000, CST, USA, #7074) for 1h at room temperature. Membranes were detected using the super enhanced chemiluminescent detection kit (Millipore, USA) and quantified with Image J software.

2.9. Statistical analysis

All data were presented as mean ± SD, and statistical analysis was carried out by SPSS 23.0. First, homogeneity analysis of variance was performed on the data. When the data were consistent with homogeneity of variance, one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used, and (LSD) tests was carried out for multiple comparisons. If the data does not conform to homogeneity of variance, Welch test was used, and games-Howell test was used for subsequent multiple comparisons. All experiments were independently repeated for a minimum of three times. P values < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

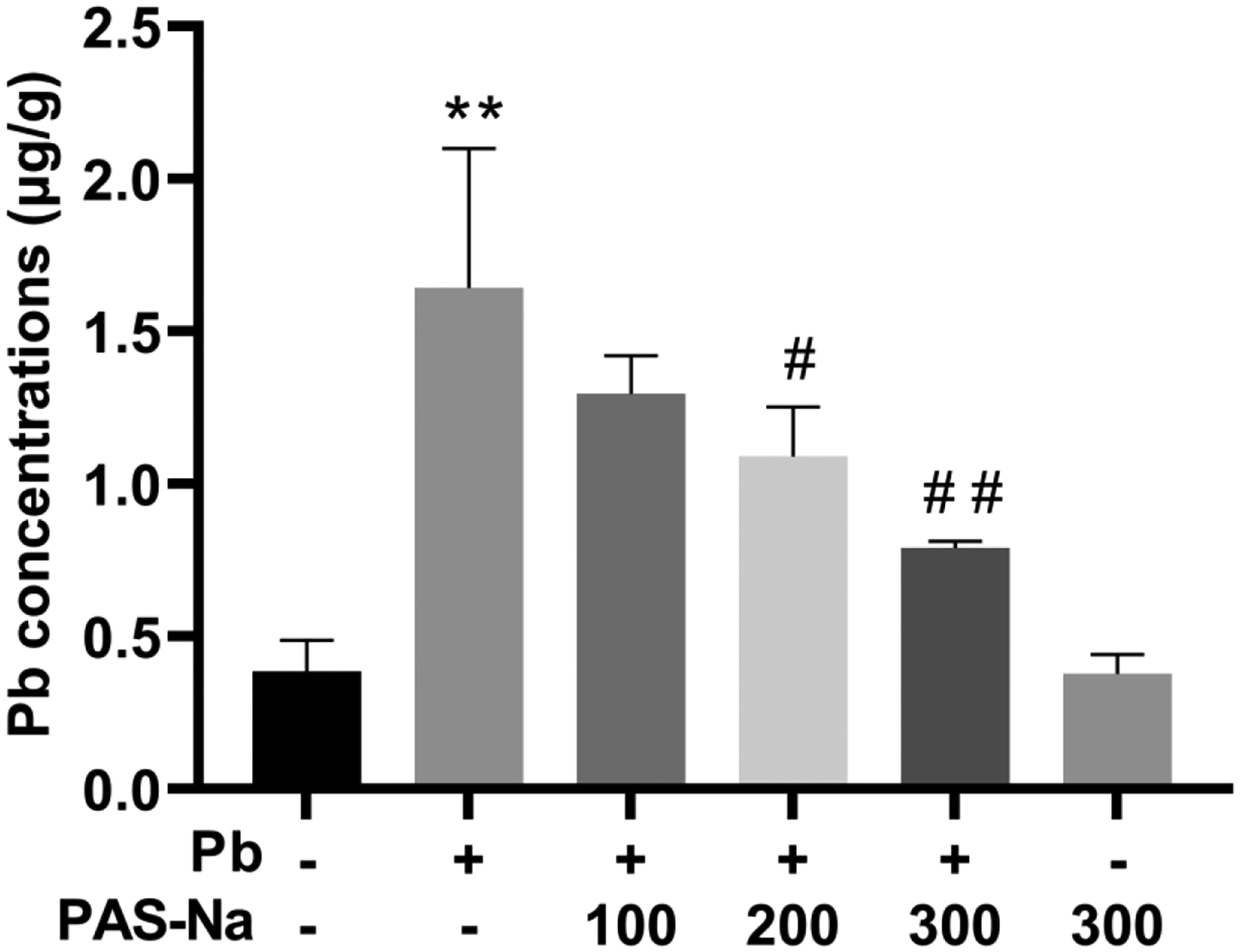

3.1. Effect of PAS-Na on the Pb levels in the cortex of rats

After Pb exposure for 4 weeks, the concentrations of Pb were significantly increased in cerebral cortex of Pb-exposed rats compared to the control group (p<0.01, Fig. 1). Notably, compared with the Pb-exposed group, PAS-Na treatment for 3 weeks reduced the cortical Pb levels in a dose-dependent manner. Both 200 and 300 mg/kg PAS-Na treatment significantly decreased the elevated levels of Pb in Pb-exposed rats (Fig. 1). PAS-Na treatment alone had no effect on Pb levels in cortex.

Fig. 1.

Effect of PAS-Na on the Pb levels in the cortex of rats. The Pb concentrations in cortex were determined by electrothermal atomic absorption spectrometry (n = 4 per group). Values are presented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01: compared to the control group; #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01: compared to Pb-treated group.

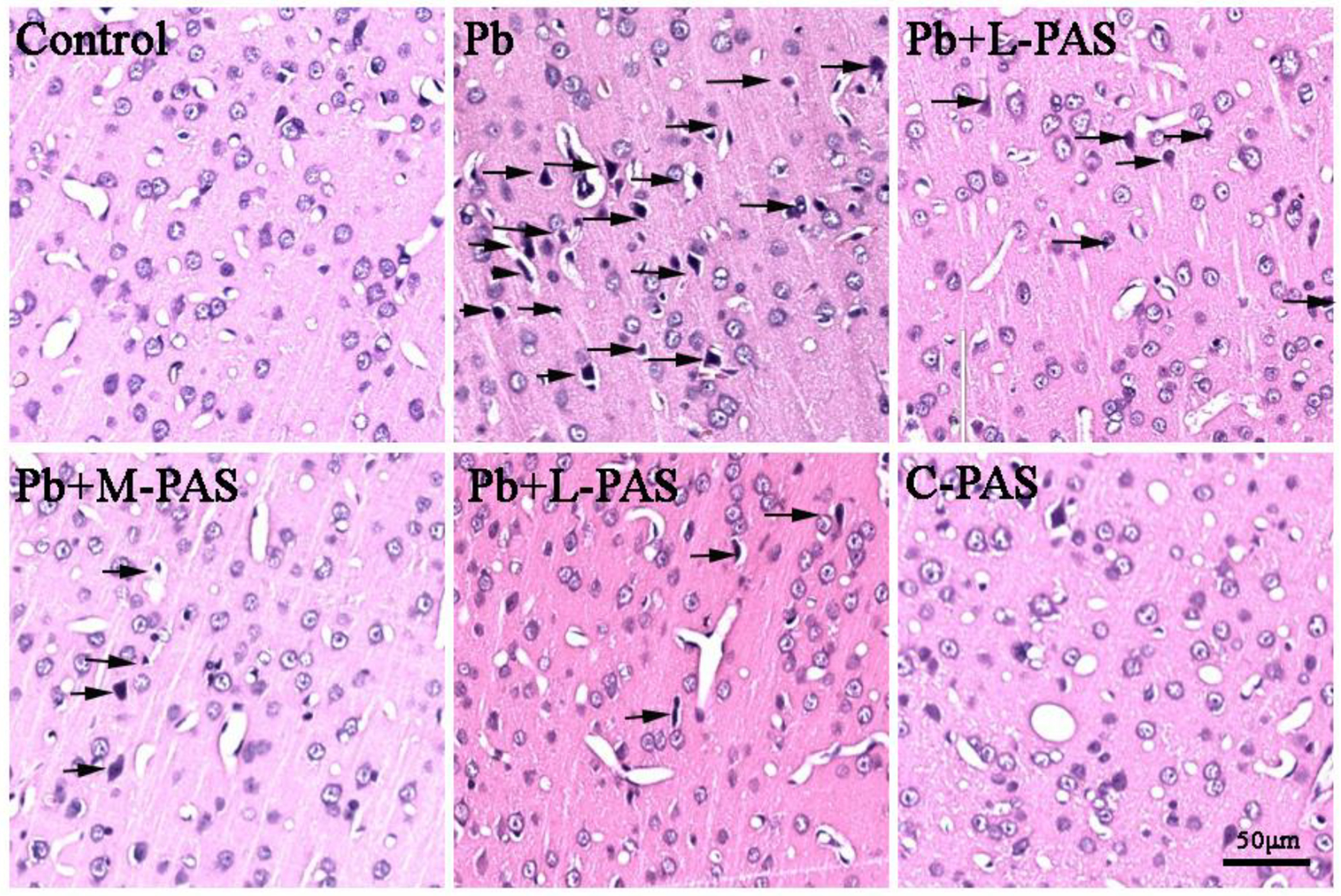

3.2. PAS-Na ameliorated histopathological changes in the cortex of Pb-exposed rat

The pathological changes in cortical tissues upon Pb exposure are shown in Fig. 2. In the control and C-PAS groups, the morphology of neurons was normal, absent nuclear pyknosis and degeneration, and the tissue was intact and regular. However, in the Pb-treated group, the neuronal morphology was disordered and loosely arranged, concomitant with densely stained nuclei, pyknosis, and triangular, rhombic or irregular nuclear morphology. In the L-, M-, H-PAS-Na treatment groups, cell morphology and arrangement were regular, and the number of cells with pyknosis was lesser than that in the Pb-treated group.

Fig. 2.

PAS-Na ameliorated histopathological changes in Pb-exposed rat cortex. The cortical sections were stained by HE. Arrow indicates degenerating neuron with nuclei densely stained, pyknosis, and showing triangular, rhombic or irregular nuclei morphology. Scale bar: 50 μm.

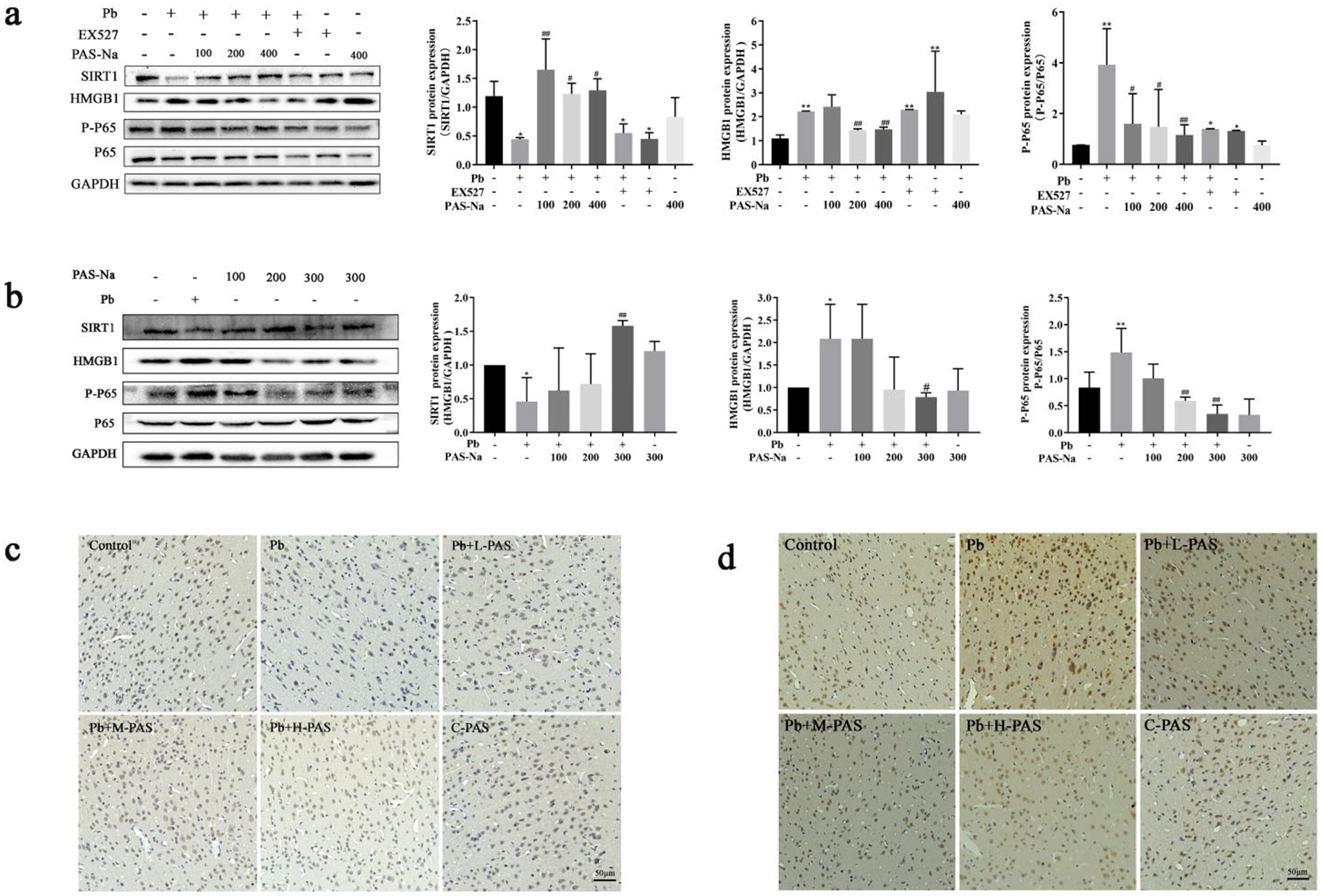

3.3. Effects of PAS-Na on SIRT1/HMGB1/NF-κB signaling pathway in Pb-exposed rats cortex

As shown in Fig. 3a, compared with the control group, the level of SIRT1 was significantly decreased, while the levels of HMGB1 and p-p65 were significantly increased in the Pb-exposed cortical neurons (p<0.05). To examine whether the reduction in SIRT1 affects the expression of HMGB1 and p65, we pretreated primary cortical neurons with EX527, a specific inhibitor of SIRT1. As shown in Fig. 3a, EX527 significantly reduced SIRT1 expression and enhanced HMGB1 and p-p65 levels compared to the control group, suggesting that SIRT1 mediated the expression of HMGB1 and p65 NF-κB in cortical neurons. Importantly, we found that PAS-Na treatment significantly increased protein levels of SIRT1 and reduced the expressions of HMGB1 and p-p65 in Pb-treated cortical neurons (p<0.05, Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

Effects of PAS-Na on SIRT1/HMGB1/NF-κB signaling pathway in Pb-exposed rat cortex. a Primary cortical neurons were exposed to 50 μM lead acetate for 24 h, follow by 100, 200 or 400 μM PAS-Na treatment for 24 h. b-d Rats were treated with 6 mg/kg lead acetate for 4 weeks, followed by 100, 200 or 300 mg/kg PAS-Na treatment for 3 weeks. The protein levels of SIRT1, HMGB1, p65 NF-κB were detected by western blotting (a, b). Immunohistochemical results of SIRT1 (c) and NF-κB (d) in the cerebral cortex of rats. Scale bar: 50 μm. Values are presented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01: compared to the control group; #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01: compared to Pb-treated group.

Next, we tested the levels of SIRT1, HMGB1 and p-p65 in the cerebral cortex of Pb-exposed rats. Western blotting analyses showed that the expression of SIRT1 was significantly decreased in Pb-exposed rats’ cortex, while HMGB1 and p-p65 expression levels were increased compared to the control group (p<0.05, Fig, 3b). After PAS-Na treatment for 3 weeks, 300 mg/kg PAS-Na significantly increased the expression of SIRT1 and decreased the levels of HMGB1 compared to the Pb-exposed group (p<0.05). Moreover, 200 and 300 mg/kg PAS-Na significantly reduced the Pb-induced phosphorylation of p65 (p<0.05, Fig, 3b). In addition, immunohistochemical staining showed that the number of SIRT1 positive cells in the cortex of Pb-exposed rats was significantly lower than in the control group (p<0.05, Fig. 3c). After 3 weeks of PAS-Na treatment, the number of SIRT1 positive cells was increased in Pb-exposed rat cortex (p<0.05). As shown in Fig. 3d, the number of NF-κB positive cells in Pb-exposed rat cortex was higher than the control group(p<0.05), and PAS-Na treatment significantly reduced the number of NF-κB positive cells in the cortex of Pb-exposed rats.

3.4. PAS-Na ameliorated Pb-induced reduction of BDNF in cortex of rats

BDNF, a conserved member of the neurotrophin family, is known to play critical roles in nervous system development [35, 36]. It has been reported that SIRT1 deficiency downregulated the expression of BDNF by limiting the level of microRNA-134 to modulate neurons synaptic plasticity [36]. To investigated the neurotoxic effect of Pb on BDNF and the intervention effect of PAS-Na, we used immunofluorescence to detect BDNF levels in cerebral cortex both in vitro and in vivo. As shown in Fig. 4a, Pb exposure significantly decreased BDNF expression in cortical neurons, which was significantly enhanced by PAS-Na treatment (p<0.05). In vivo, we observed that BDNF levels in Pb-exposed cortex was significantly reduced compared to the control group (Fig. 4b). However, the expressions of BDNF in L, M-PAS-Na treatment group were significantly increased in the cortex compared with the Pb-exposed group (Fig. 4b).

Fig. 4.

PAS-Na ameliorated Pb-induced reduction of BDNF in cortex of rats. a BDNF immunofluorescence (green) in cortical neurons. b BDNF immunofluorescence (red) in cortex tissues counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar: 50 μm. Values are presented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01: compared to the control group; #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01: compared to Pb-treated group.

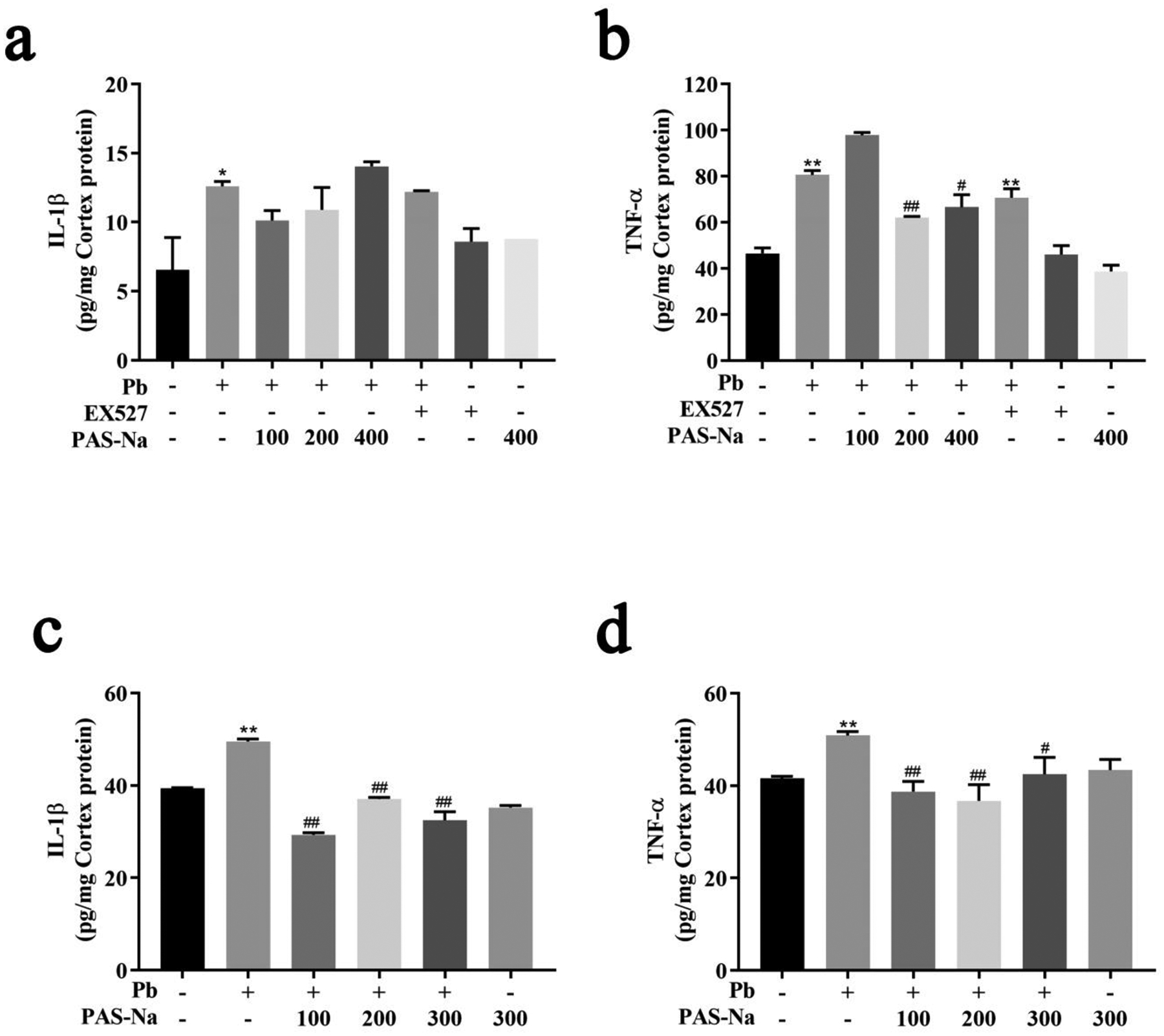

3.5. PAS-Na attenuated Pb-induced increase of inflammatory cytokines in cerebral cortex of rats.

To evaluate whether PAS-Na can reduce the levels of inflammatory cytokines in Pb-exposed rat cortex, we measured the levels of TNF-α and IL-1β using ELISA. Pb exposure up-regulated the levels of TNF-α and IL-1β in cortical neurons compare to the control group (p<0.05, Fig. 5a, b). After treatment with 100, 200 and 400 μM PAS-Na for 24 h, the levels of TNF-α were significantly decreased in cortical neurons compared to the Pb-exposed group (p<0.05). Concomitantly, the levels of TNF-α and IL-1β were significantly increased in cerebral cortex of Pb-exposed rats (p<0.05, Fig. 5c, d). Treatment with 100, 200 and 300 mg/kg PAS-Na significantly reduced inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β levels in Pb-exposed rat cortex (p<0.05, Fig. 5c, d).

Fig. 5.

PAS-Na attenuated Pb-induced increase of inflammatory cytokines in cerebral cortex of rats.

a, b Inflammatory cytokines TNF-α (a) and IL-1β (b) levels in cortical neurons. c, d Inflammatory cytokines TNF-α (c) and IL-1β (d) levels in cortex tissues. Values are presented as mean ± SD. *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01: compared to the control group; #p < 0.05 and ##p < 0.01: compared to Pb-treated group.

4. Discussion

Environmental heavy metal contamination, including Pb, continues to pose persistent human health risk [3]. Numerous studies have shown that Pb, even at low blood concentrations causes damage to cortical neurons and affect cerebral cortical-related functions, including deficits in cognitive, attention, intelligence and motor skills [7, 9, 37]. MRI data have shown that blood Pb concentration was inversely correlated with cerebral cortical volume [7–9]. Children with higher blood Pb levels exhibited smaller cortical volumes and cortical surface areas, displaying lower cognitive test scores [9]. Rodent studies have found that Pb exposure can induce oxidative stress, energy metabolism disturbance and abnormal inflammatory response in cerebral cortex [19, 38, 39]. In this study, our results in behavior (data not shown) were in accordance with the previous study that Pb exposure caused rats learning and memory impairments in the Morris water maze test, which was improved by PAS-NA treatment [14]. Furthermore, we found that Pb exposure induced cerebral cortex pathological damages and inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β releases. PAS-Na treatment, however, ameliorated the Pb-induced the pathological changes in cortical tissues and the increased levels of TNF-α and IL-1β through SIRT1/HMGB1/NF-κB pathway.

Neuroinflammation generally refers to an inflammatory response within the CNS that can be caused by various pathological insults, including infection, trauma, ischemia and various toxins [40]. Pb has been shown to induce neuroinflammation by stimulating nerve cells to release pro-inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α [17, 39]. Individuals exposed to Pb exhibit higher serum levels of TNF-α and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor than non-exposed humans [18]. Studies in rodent mammals discovered that Pb can accelerate the brain inflammatory process by affecting the expression and activity of enzymes involved in the inflammatory process (eg, cyclooxygenase 2, caspase 1, nitrogen oxide synthase), increasing expressions of inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, TGF-β1, IL-16, IL-18, and IL-10) in the brain [41]. Furthermore, Pb exposure induced a significant increase in microglial activation, upregulating the release of cytokines including TNF-a, IL-1β, iNOS in microglial cultures alone as well as neuronal injury in the co-culture with hippocampal neurons [42]. Although microglia are considered to be a major source of proinflammatory cytokines [43], our experiments found that the levels of potent proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β increased sharply in primary cortical neurons of Pb-exposure rats, demonstrating that Pb can induce neuronal inflammation. Importantly, PAS-Na treatment significantly reduced TNF-α and IL-1β levels in cortical tissues, demonstrating the potential of PAS-Na for the treatment of brain inflammation. In our previous animal experiments, PAS-Na has been found to mitigate manganese-induced increases in IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and prostaglandins E2 levels in the brain [26]. In addition, PAS-Na was found to ameliorate the pathological changes of hippocampus and the high levels of IL-1β induced by Pb [14]. Collectively, PAS-Na, a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug, merits further investigations into its efficacy and potential to mitigate neurodegeneration associated with neuroinflammation.

SIRT1 plays an important regulatory role in neuroinflammation. For example, an in vivo study demonstrated that SIRT1 downregulated the level of NF-κB expression and then decreased the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-1β, while SIRT1 inhibitor EX527 abolished the anti-inflammatory effect of BML-111 (a drug that can inhibit neutrophil recruitment and peripheral inflammation) on sepsis [44]. Activation of SIRT1 by melatonin has been shown to prevent lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced NLRP3 inflammasome expressions in mouse N9 microglial cells and hippocampus of depressive-like behavior mice [45]. Notably, SIRT1 may have a protective effect against Pb-induced toxicity. Li et al. [46] have demonstrated that allicin exerts protective effects against Pb-induced bone loss by activating SIRT1/FoxO1 pathway and anti-oxidative stress. The upregulation of SIRT1 by SRT1720 (a SIRT1 activator) has also been shown to alleviate Pb-induced hepatic lipid accumulation in HepG2 cells [47]. However, few studies have addressed the relationship between SIRT1 and Pb-induced neuroinflammatory responses.

Our experiments found that Pb exposure inhibited SIRT1 expression and elevated TNF-α and IL-1β levels in the rat cerebral cortex both in vivo and in vitro. In vitro experiments, western blot analysis found that the expression of SIRT1 was significantly decreased, while the expressions of P-P65 and HMGB1 were elevated in the EX527 (SIRT1 inhibitor) group, suggesting that the expression of HMGB1 and P-P65 in rat cerebral cortex was regulated by SIRT1. HMGB1 plays an important role in the regulation of inflammation in the brain [48]. Under pathological conditions, HMGB1 is released into the extracellular space from cellular nuclei, causing activation of microglia, thereby participating in the neuroinflammation [49]. The level of HMGB1 release is regulated by SIRT1, and HMGB1 leads to the activation of NF-κB, which augments the release of various pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α and IL-1β), ultimately leading to CNS inflammation [22, 50]. Herein, our results have established that Pb exposure inhibited the expression of SIRT1 protein and promoted the expression of HMGB1 and P-P65 NF-κB, leading to increased levels of inflammatory mediators such as TNF-α and IL-1β in primary cortical neurons and rats cerebral cortex. These results demonstrate that the SIRT1/HMGB1/NF-κB pathway plays a pivotal mediating role in Pb-induced neuroinflammation in rat cortex.

BDNF is a critical factor for neuronal development and synaptic plasticity and hopes to achieve as potential treatments in CNS disorders [51]. A number of studies have reported that Pb exposure reduces BDNF gene and protein expression, and it may also alter the transport of BDNF vesicles to the releasing site, resulting in reduced extracellular mature BDNF concentrations [24, 52]. BDNF may serve as a conduit between inflammation and Pb-induced neurodegeneration. It has been reported that maternal Pb exposure decreases the levels of BDNF and tyrosine receptor-kinase protein B in the offspring rat pups and retards brain development with concomitant increase in oxidative stress, and inflammatory response [24]. The relationship between BDNF and the inflammatory response is thought to be associated with increased NF-κB expression [53]. Reduction of pre-synaptic BDNF signaling activates the kinases IKKα and IKKβ, which then phosphorylates and degrades IκBα (the NF-κB inhibitory unit), and induces NF-κB release [53]. In the present study, Pb exposure significantly decreased the expression of BDNF in rat cortical tissue and primary neurons, accompanied by an increase in the expression of p-p65 NF-κB, suggesting that BDNF/NF-κB may serve as a signaling pathway in mediating Pb-induced cortical inflammation. In addition, several studies found that SIRT1 can mediate the expression of BDNF in neurons [23, 36]. Chen et al. [23] have reported that Pb exposure downregulated the expression of SIRT1, CREB phosphorylation and BDNF to impair cognitive function in rats. In agreement, our study found that Pb exposure reduced SIRT1 and BDNF expression. However, whether Pb affects the inflammatory process by mediating SIRT1 to regulate BDNF expression needs further study.

CaNa2-EDTA is often used as a therapeutic agent for Pb poisoning in clinical treatment, owing its chelating metal properties. However, CaNa2-EDTA cannot cross the blood-brain barrier, limiting its therapeutic effect in the brain [54]. PAS-Na and its major metabolite N-acetyl-para-aminosalicylic acid can readily cross the blood-brain barrier into brain [55–57], which make they may be able to chelate Pb in the brain because their structures contain carboxyl and hydroxyl groups. In addition, PAS-NA has anti-inflammatory properties and has been shown to reduce levels of inflammatory factors in several in vitro and in vivo studies. Li et al. [26] have reported that PAS-Na decreased manganese-induced high levels of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1β and prostaglandins E2 through MAPK pathway and COX-2 in the brain. PAS-Na was also found to inhibit manganese-induced inflammation by inhibiting NLRP3-CASP1 inflammasome pathway, NF-κB activation and oxidative stress [25]. Recently, PAS-Na has been shown to reduce Pb-induced elevation of IL-1β levels in rat hippocampus through ERK1/2-p90RSK/NF-κB pathway [14]. In the present study, we found that PAS-Na reduced the Pb-induced increase of TNF-α and IL-1β levels in the cerebral cortex by regulating the SIRT1/HMGB1/NF-κB pathway and BDNF levels. Overall, PAS-Na shows efficacy in treating brain inflammation, but further research is needed.

5. Conclusion

The present study demonstrated that Pb exposure leads to cerebral cortex pathological damage, which may be due to the neuroinflammation induced by Pb. Pb decreased the levels of SIRT1 and BDNF, while increasing the levels of HMGB1 and NF-κB, accompanied with increased levels of TNF-α and IL-1β in the cortex. PAS-Na treatment ameliorated Pb-induced cortical pathological damage, exerting anti-inflammatory effects by mediating the SIRT1/HMGB1/NF-κB pathway and BDNF expression. Nonetheless, the therapeutic effect of PAS-Na on brain neuroinflammation requires additional experimentation.

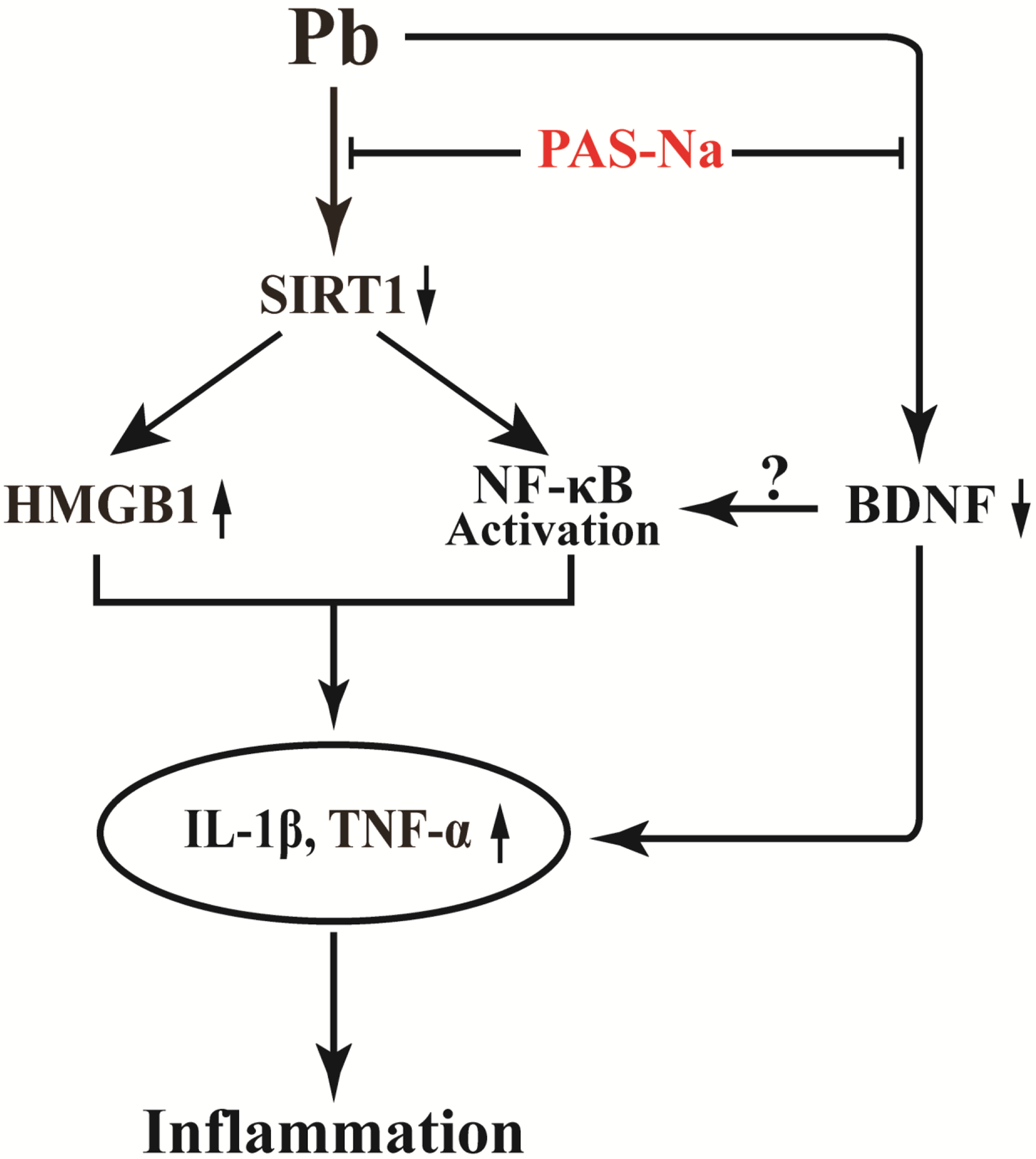

Fig. 6.

Schema of the mechanisms by which PAS-Na protects Pb-induced neuroinflammation.

Acknowledgements

The author thanked Dr. Yan Li from Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region Institute for the Prevention and Treatment of Occupational Disease for her help in the detection of cerebral cortex Pb levels.

Funding

Funding support was provided by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC 81773476).

Footnotes

Competing Interests

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Ethics Approval and Consent to participate

All animal procedures performed in this study were performed strictly according to the international standards of animal care guidelines and have been approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Guangxi Medical University [Approval ID: SCXK (Gui) 2014–0002].

Consent for publish

The paper has been approved by all authors for publication.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

Uncategorized References

- 1.Mitra A, Chatterjee S, Kataki S, Rastogi RP, and Gupta DK, (2021) Bacterial Tolerance Strategies against Lead Toxicity and Their Relevance in Bioremediation Application. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 28(12): p. 14271–14284. 10.1007/s11356-021-12583-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mitra P, Sharma S, Purohit P, and Sharma P, (2017) Clinical and Molecular Aspects of Lead Toxicity: An Update. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 54(7–8): p. 506–528. 10.1080/10408363.2017.1408562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hon KL, Fung CK, and Leung AK, (2017) Childhood Lead Poisoning: An Overview. Hong Kong Med J. 23(6): p. 616–21. 10.12809/hkmj176214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schwartz BS, Stewart WF, Bolla KI, Simon PD, Bandeen-Roche K, Gordon PB, Links JM, and Todd AC, (2000) Past Adult Lead Exposure Is Associated with Longitudinal Decline in Cognitive Function. Neurology. 55(8): p. 1144–50. 10.1212/wnl.55.8.1144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lanphear BP, Hornung R, Khoury J, Yolton K, Baghurst P, Bellinger DC, Canfield RL, Dietrich KN, Bornschein R, Greene T, Rothenberg SJ, Needleman HL, Schnaas L, Wasserman G, Graziano J, and Roberts R, (2005) Low-Level Environmental Lead Exposure and Children’s Intellectual Function: An International Pooled Analysis. Environ Health Perspect. 113(7): p. 894–9. 10.1289/ehp.7688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rocha A and Trujillo KA, (2019) Neurotoxicity of Low-Level Lead Exposure: History, Mechanisms of Action, and Behavioral Effects in Humans and Preclinical Models. Neurotoxicology. 73: p. 58–80. 10.1016/j.neuro.2019.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cecil KM, Brubaker CJ, Adler CM, Dietrich KN, Altaye M, Egelhoff JC, Wessel S, Elangovan I, Hornung R, Jarvis K, and Lanphear BP, (2008) Decreased Brain Volume in Adults with Childhood Lead Exposure. PLoS Med. 5(5): p. e112. 10.1371/journal.pmed.0050112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Reuben A, Elliott ML, Abraham WC, Broadbent J, Houts RM, Ireland D, Knodt AR, Poulton R, Ramrakha S, Hariri AR, Caspi A, and Moffitt TE, (2020) Association of Childhood Lead Exposure with Mri Measurements of Structural Brain Integrity in Midlife. Jama. 324(19): p. 1970–1979. 10.1001/jama.2020.19998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marshall AT, Betts S, Kan EC, McConnell R, Lanphear BP, and Sowell ER, (2020) Association of Lead-Exposure Risk and Family Income with Childhood Brain Outcomes. Nat Med. 26(1): p. 91–97. 10.1038/s41591-019-0713-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leão LKR, Bittencourt LO, Oliveira ACA, Nascimento PC, Ferreira MKM, Miranda GHN, Ferreira RO, Eiró-Quirino L, Puty B, Dionizio A, Cartágenes SC, Freire MAM, Buzalaf MAR, Crespo-Lopez ME, Maia CSF, and Lima RR, (2021) Lead-Induced Motor Dysfunction Is Associated with Oxidative Stress, Proteome Modulation, and Neurodegeneration in Motor Cortex of Rats. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2021: p. 5595047. 10.1155/2021/5595047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ji X, Wang B, Paudel YN, Li Z, Zhang S, Mou L, Liu K, and Jin M, (2021) Protective Effect of Chlorogenic Acid and Its Analogues on Lead-Induced Developmental Neurotoxicity through Modulating Oxidative Stress and Autophagy. Front Mol Biosci. 8: p. 655549. 10.3389/fmolb.2021.655549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu F, Wang Z, Wei Y, Liu R, Jiang C, Gong C, Liu Y, and Yan B, (2021) The Leading Role of Adsorbed Lead in Pm(2.5)-Induced Hippocampal Neuronal Apoptosis and Synaptic Damage. J Hazard Mater. 416: p. 125867. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.125867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hernández-Coro A, Sánchez-Hernández BE, Montes S, Martínez-Lazcano JC, González-Guevara E, and Pérez-Severiano F, (2021) Alterations in Gene Expression Due to Chronic Lead Exposure Induce Behavioral Changes. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 126: p. 361–367. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lu LL, Zhang YW, Li ZC, Fang YY, Wang LL, Zhao YS, Li SJ, Ou SY, Aschner M, and Jiang YM, (2021) Therapeutic Effects of Sodium Para-Aminosalicylic Acid on Cognitive Deficits and Activated Erk1/2-P90(Rsk)/Nf-Kb Inflammatory Pathway in Pb-Exposed Rats. Biol Trace Elem Res. 10.1007/s12011-021-02874-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hou Y, Wei Y, Lautrup S, Yang B, Wang Y, Cordonnier S, Mattson MP, Croteau DL, and Bohr VA, (2021) Nad(+) Supplementation Reduces Neuroinflammation and Cell Senescence in a Transgenic Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease Via Cgas-Sting. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 118(37). 10.1073/pnas.2011226118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ghosh S, Wu MD, Shaftel SS, Kyrkanides S, LaFerla FM, Olschowka JA, and O’Banion MK, (2013) Sustained Interleukin-1β Overexpression Exacerbates Tau Pathology Despite Reduced Amyloid Burden in an Alzheimer’s Mouse Model. J Neurosci. 33(11): p. 5053–64. 10.1523/jneurosci.4361-12.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Machoń-Grecka A, Dobrakowski M, Boroń M, Lisowska G, Kasperczyk A, and Kasperczyk S, (2017) The Influence of Occupational Chronic Lead Exposure on the Levels of Selected Pro-Inflammatory Cytokines and Angiogenic Factors. Hum Exp Toxicol. 36(5): p. 467–473. 10.1177/0960327117703688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Di Lorenzo L, Vacca A, Corfiati M, Lovreglio P, and Soleo L, (2007) Evaluation of Tumor Necrosis Factor-Alpha and Granulocyte Colony-Stimulating Factor Serum Levels in Lead-Exposed Smoker Workers. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 20(2): p. 239–47. 10.1177/039463200702000204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li N, Liu F, Song L, Zhang P, Qiao M, Zhao Q, and Li W, (2014) The Effects of Early Life Pb Exposure on the Expression of Il1-B, Tnf-A and Aβ in Cerebral Cortex of Mouse Pups. J Trace Elem Med Biol. 28(1): p. 100–4. 10.1016/j.jtemb.2013.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen C, Zhou M, Ge Y, and Wang X, (2020) Sirt1 and Aging Related Signaling Pathways. Mech Ageing Dev. 187: p. 111215. 10.1016/j.mad.2020.111215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jiao F and Gong Z, (2020) The Beneficial Roles of Sirt1 in Neuroinflammation-Related Diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020: p. 6782872. 10.1155/2020/6782872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen X, Chen C, Fan S, Wu S, Yang F, Fang Z, Fu H, and Li Y, (2018) Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acid Attenuates the Inflammatory Response by Modulating Microglia Polarization through Sirt1-Mediated Deacetylation of the Hmgb1/Nf-Kb Pathway Following Experimental Traumatic Brain Injury. J Neuroinflammation. 15(1): p. 116. 10.1186/s12974-018-1151-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen F, Zhou CC, Yang Y, Liu JW, and Yan CH, (2019) Gm1 Ameliorates Lead-Induced Cognitive Deficits and Brain Damage through Activating the Sirt1/Creb/Bdnf Pathway in the Developing Male Rat Hippocampus. Biol Trace Elem Res. 190(2): p. 425–436. 10.1007/s12011-018-1569-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hossain S, Bhowmick S, Jahan S, Rozario L, Sarkar M, Islam S, Basunia MA, Rahman A, Choudhury BK, and Shahjalal H, (2016) Maternal Lead Exposure Decreases the Levels of Brain Development and Cognition-Related Proteins with Concomitant Upsurges of Oxidative Stress, Inflammatory Response and Apoptosis in the Offspring Rats. Neurotoxicology. 56: p. 150–158. 10.1016/j.neuro.2016.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peng DJ, Li J, Deng Y, Zhu X, Zhao L, Zhang Y, Li Z, Ou S, Li S, and Jiang Y, (2020) Sodium Para-Aminosalicylic Acid Inhibits Manganese-Induced Nlrp3 Inflammasome-Dependent Pyroptosis by Inhibiting Nf-Kb Pathway Activation and Oxidative Stress. J Neuroinflammation. 17(1): p. 343. 10.1186/s12974-020-02018-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li SJ, Qin WX, Peng DJ, Yuan ZX, He SN, Luo YN, Aschner M, Jiang YM, Liang DY, Xie BY, and Xu F, (2018) Sodium P-Aminosalicylic Acid Inhibits Sub-Chronic Manganese-Induced Neuroinflammation in Rats by Modulating Mapk and Cox-2. Neurotoxicology. 64: p. 219–229. 10.1016/j.neuro.2017.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ky SQ, Deng HS, Xie PY, and Hu W, (1992) A Report of Two Cases of Chronic Serious Manganese Poisoning Treated with Sodium Para-Aminosalicylic Acid. Br J Ind Med. 49(1): p. 66–9. 10.1136/oem.49.1.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Deng Y, Peng D, Yang C, Zhao L, Li J, Lu L, Zhu X, Li S, Aschner M, and Jiang Y, (2021) Preventive Treatment with Sodium Para-Aminosalicylic Acid Inhibits Manganese-Induced Apoptosis and Inflammation Via the Mapk Pathway in Rat Thalamus. Drug Chem Toxicol: p. 1–10. 10.1080/01480545.2021.2008127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li ZC, Wang F, Li SJ, Zhao L, Li JY, Deng Y, Zhu XJ, Zhang YW, Peng DJ, and Jiang YM, (2020) Sodium Para-Aminosalicylic Acid Reverses Changes of Glutamate Turnover in Manganese-Exposed Rats. Biol Trace Elem Res. 197(2): p. 544–554. 10.1007/s12011-019-02001-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li J, Deng Y, Peng D, Zhao L, Fang Y, Zhu X, Li S, Aschner M, Ou S, and Jiang Y, (2021) Sodium P-Aminosalicylic Acid Attenuates Manganese-Induced Neuroinflammation in Bv2 Microglia by Modulating Nf-Kb Pathway. Biol Trace Elem Res. 199(12): p. 4688–4699. 10.1007/s12011-021-02581-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Deng XF. ea, (2009) Efects of Sodium Para-Aminosalicylic Acid on Hippocampal Ultramicro-Structure of Subchronic Lead-Exposed Rats. J Toxicol. 23(03): p. 213–216. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li Z-c, Wang L-l, Zhao Y-s, Peng D-j, Chen J, Jiang S-y, Zhao L, Aschner M, Li S-j, and Jiang Y-m, (2022) Sodium Para-Aminosalicylic Acid Ameliorates Lead-Induced Hippocampal Neuronal Apoptosis by Suppressing the Activation of the Ip3r-Ca2+-Ask1-P38 Signaling Pathway. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety. 241: p. 113829. 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2022.113829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.al He, (2017) Effects of Sodium P-Aminosalicylate on Lead-Induced Apoptosis of Pc12 Cells in Vitro. Chin J Pharmacol Toxicol. 31(02): p. 159–164. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Roppongi RT, Champagne-Jorgensen KP, and Siddiqui TJ, (2017) Low-Density Primary Hippocampal Neuron Culture. J Vis Exp, (122). 10.3791/55000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhao J, Zhang Q, Zhang B, Xu T, Yin D, Gu W, and Bai J, (2020) Developmental Exposure to Lead at Environmentally Relevant Concentrations Impaired Neurobehavior and Nmdar-Dependent Bdnf Signaling in Zebrafish Larvae. Environ Pollut. 257: p. 113627. 10.1016/j.envpol.2019.113627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gao J, Wang WY, Mao YW, Gräff J, Guan JS, Pan L, Mak G, Kim D, Su SC, and Tsai LH, (2010) A Novel Pathway Regulates Memory and Plasticity Via Sirt1 and Mir-134. Nature. 466(7310): p. 1105–9. 10.1038/nature09271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang T, Zhang J, and Xu Y, (2020) Epigenetic Basis of Lead-Induced Neurological Disorders. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 17(13). 10.3390/ijerph17134878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Atuadu V, Benneth BA, Oyem J, Esom E, Mba C, Nebo K, Ezemeka G, and Anibeze C, (2020) Adansonia Digitata L. Leaf Extract Attenuates Lead-Induced Cortical Histoarchitectural Changes and Oxidative Stress in the Prefrontal Cortex of Adult Male Wistar Rats. Drug Metab Pers Ther. 10.1515/dmdi-2020-0116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chibowska K, Korbecki J, Gutowska I, Metryka E, Tarnowski M, Goschorska M, Barczak K, Chlubek D, and Baranowska-Bosiacka I, (2020) Pre- and Neonatal Exposure to Lead (Pb) Induces Neuroinflammation in the Forebrain Cortex, Hippocampus and Cerebellum of Rat Pups. Int J Mol Sci. 21(3). 10.3390/ijms21031083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leng F and Edison P, (2021) Neuroinflammation and Microglial Activation in Alzheimer Disease: Where Do We Go from Here? Nat Rev Neurol. 17(3): p. 157–172. 10.1038/s41582-020-00435-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chibowska K, Baranowska-Bosiacka I, Falkowska A, Gutowska I, Goschorska M, and Chlubek D, (2016) Effect of Lead (Pb) on Inflammatory Processes in the Brain. Int J Mol Sci. 17(12). 10.3390/ijms17122140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu MC, Liu XQ, Wang W, Shen XF, Che HL, Guo YY, Zhao MG, Chen JY, and Luo WJ, (2012) Involvement of Microglia Activation in the Lead Induced Long-Term Potentiation Impairment. PLoS One. 7(8): p. e43924. 10.1371/journal.pone.0043924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu L, He D, and Bai Y, (2016) Microglia-Mediated Inflammation and Neurodegenerative Disease. Mol Neurobiol. 53(10): p. 6709–6715. 10.1007/s12035-015-9593-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pan S, Wu Y, Pei L, Li S, Song L, Xia H, Wang Y, Yu Y, Yang X, Shu H, Zhang J, Yuan S, and Shang Y, (2018) Bml-111 Reduces Neuroinflammation and Cognitive Impairment in Mice with Sepsis Via the Sirt1/Nf-Kb Signaling Pathway. Front Cell Neurosci. 12: p. 267. 10.3389/fncel.2018.00267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arioz BI, Tastan B, Tarakcioglu E, Tufekci KU, Olcum M, Ersoy N, Bagriyanik A, Genc K, and Genc S, (2019) Melatonin Attenuates Lps-Induced Acute Depressive-Like Behaviors and Microglial Nlrp3 Inflammasome Activation through the Sirt1/Nrf2 Pathway. Front Immunol. 10: p. 1511. 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li D, Liang H, Li Y, Zhang J, Qiao L, and Luo H, (2021) Allicin Alleviates Lead-Induced Bone Loss by Preventing Oxidative Stress and Osteoclastogenesis Via Sirt1/Foxo1 Pathway in Mice. Biol Trace Elem Res. 199(1): p. 237–243. 10.1007/s12011-020-02136-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhao Y, Mao A, Zhang R, Guan S, and Lu J, (2022) Sirt1/Mtor Pathway-Mediated Autophagy Dysregulation Promotes Pb-Induced Hepatic Lipid Accumulation in Hepg2 Cells. Environ Toxicol. 37(3): p. 549–563. 10.1002/tox.23420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Okuma Y, Liu K, Wake H, Zhang J, Maruo T, Date I, Yoshino T, Ohtsuka A, Otani N, Tomura S, Shima K, Yamamoto Y, Yamamoto H, Takahashi HK, Mori S, and Nishibori M, (2012) Anti-High Mobility Group Box-1 Antibody Therapy for Traumatic Brain Injury. Ann Neurol. 72(3): p. 373–84. 10.1002/ana.23602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nakamura Y, Fukuta A, Miyashita K, Zhang FF, Wang D, Liu K, Wake H, Hisaoka-Nakashima K, Nishibori M, and Morioka N, (2021) Perineural High-Mobility Group Box 1 Induces Mechanical Hypersensitivity through Activation of Spinal Microglia: Involvement of Glutamate-Nmda Receptor Dependent Mechanism in Spinal Dorsal Horn. Biochem Pharmacol. 186: p. 114496. 10.1016/j.bcp.2021.114496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liu X, Lu B, Fu J, Zhu X, Song E, and Song Y, (2021) Amorphous Silica Nanoparticles Induce Inflammation Via Activation of Nlrp3 Inflammasome and Hmgb1/Tlr4/Myd88/Nf-Kb Signaling Pathway in Huvec Cells. J Hazard Mater. 404(Pt B): p. 124050. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wang CS, Kavalali ET, and Monteggia LM, (2022) Bdnf Signaling in Context: From Synaptic Regulation to Psychiatric Disorders. Cell. 185(1): p. 62–76. 10.1016/j.cell.2021.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Neal AP, Stansfield KH, Worley PF, Thompson RE, and Guilarte TR, (2010) Lead Exposure During Synaptogenesis Alters Vesicular Proteins and Impairs Vesicular Release: Potential Role of Nmda Receptor-Dependent Bdnf Signaling. Toxicol Sci. 116(1): p. 249–63. 10.1093/toxsci/kfq111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lima Giacobbo B, Doorduin J, Klein HC, Dierckx R, Bromberg E, and de Vries EFJ, (2019) Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor in Brain Disorders: Focus on Neuroinflammation. Mol Neurobiol. 56(5): p. 3295–3312. 10.1007/s12035-018-1283-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Patra RC, Swarup D, and Dwivedi SK, (2001) Antioxidant Effects of Alpha Tocopherol, Ascorbic Acid and L-Methionine on Lead Induced Oxidative Stress to the Liver, Kidney and Brain in Rats. Toxicology. 162(2): p. 81–8. 10.1016/s0300-483x(01)00345-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hong L, Jiang W, Zheng W, and Zeng S, (2011) Hplc Analysis of Para-Aminosalicylic Acid and Its Metabolite in Plasma, Cerebrospinal Fluid and Brain Tissues. J Pharm Biomed Anal. 54(5): p. 1101–9. 10.1016/j.jpba.2010.11.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hong L, Jiang W, Pan H, Jiang Y, Zeng S, and Zheng W, (2011) Brain Regional Pharmacokinetics of P-Aminosalicylic Acid and Its N-Acetylated Metabolite: Effectiveness in Chelating Brain Manganese. Drug Metab Dispos. 39(10): p. 1904–9. 10.1124/dmd.111.040915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zheng W, Jiang YM, Zhang Y, Jiang W, Wang X, and Cowan DM, (2009) Chelation Therapy of Manganese Intoxication with Para-Aminosalicylic Acid (Pas) in Sprague-Dawley Rats. Neurotoxicology. 30(2): p. 240–8. 10.1016/j.neuro.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.