Abstract

This paper is the fifth in a five-part series on statistical methodology for performance assessment of multi-parametric quantitative imaging biomarkers (mpQIBs) for radiomic analysis. Radiomics is the process of extracting visually imperceptible features from radiographic medical images using data-driven algorithms. We refer to the radiomic features as data-driven imaging markers (DIMs), which are quantitative measures discovered under a data-driven framework from images beyond visual recognition but evident as patterns of disease processes irrespective of whether or not ground truth exists for the true value of the DIM. This paper aims to set guidelines on how to build machine learning models using DIMs in radiomics and to apply and report them appropriately. We provide a list of recommendations, named RANDAM (an abbreviation of “Radiomic ANalysis and DAta Modeling”), for analysis, modeling, and reporting in a radiomic study to make machine learning analyses in radiomics more reproducible. RANDAM contains five main components to use in reporting radiomics studies: design, data preparation, data analysis and modeling, reporting, and material availability. Real case studies in lung cancer research are presented along with simulation studies to compare different feature selection methods and several validation strategies.

Keywords: data-driven imaging markers, radiomics, machine learning, prediction, reporting

1. Introduction

Metrology concepts, algorithm comparisons, and technical performance of conventional quantitative imaging biomarkers (QIBs) have been well-studied 1-4. The Quantitative Imaging Biomarkers Alliance (QIBA) working group, under the direction of Radiological Society of North America (RSNA), has established standardized terminology for use of QIBs in research and clinical practice4. QIBA aims to improve the value and practicality of QIBs by reducing variability across devices, patients, and time. However, QIBA has heretofore devoted relatively little attention to the exponentially growing field of radiomics. The need for standardization of the radiomics process remains critical for establishing reproducibility and clinical utility. However, the generalizability and scalability of large-scale radiomics data are challenges.

Radiomics has been defined as “the conversion of images to higher-dimensional data and the subsequent mining of these data for improved decision support” 5. The potential of radiomics to improve clinical decision support is well-known 6. In radiomics, a large number of features is extracted from radiographic medical images using data-driven algorithms 7, 8 with the hope that patterns will emerge to help inform clinical decisions despite a lack of complete biological understanding. The process begins with the acquisition of medical images from single or multiple modalities in which regions of interest (ROIs) have been segmented and processed using appropriate algorithms. Quantitative radiomic features are then extracted from these ROIs and placed into a database along with other clinical or genomic data. Investigators can then use the database to develop diagnostic or prognostic prediction models for outcomes of interest. A major difference between radiomics and many other efforts in translating quantitative imaging into clinical knowledge is that an objective truth basis (reference standard) is not involved in the extraction and selection of radiomic features.

Recent studies have shown that radiomics can improve or outperform existing methods in disease diagnosis or prognosis prediction in many medical application fields 9, 10. The use of radiomic features potentially enhances the existing data available to clinicians for better clinical decision-making. Sun et al. 11 demonstrated the clinical potential of radiomics as a powerful tool for personalized therapy in the emerging field of immuno-oncology. Aerts et al. 12 showed that radiomic features may be associated with biological gene sets, such as cell cycle phase, DNA recombination, regulation of immune system process, etc. In magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), data-driven imaging markers (DIMs) have been shown to be able to predict various mutations of genes such as TP53, EGFR, and MGMT methylation 13, 14.

As defined by Kessler et al. 4, a QIB is ‘an objective characteristic derived from an in vivo image measured on a ratio or interval scale as indicators of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or a response to a therapeutic intervention.‘ To distinguish radiomic features from conventional QIBs, here we refer to the former as data-driven imaging markers (DIMs), which are quantitative measures discovered under a data-driven framework from images that are beyond visual recognition but evident as patterns irrespective of a ground truth basis. Table 1 lists the differences between multi-parametric image biomarkers and DIMs.

Table 1:

The differences between multiparametric imaging biomarkers and data-driven imaging markers

| Multiparametric image biomarkers | Data-driven image markers | |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Multiple objective characteristics derived from an in vivo image measured on a ratio or interval scale as an indicator of a normal biological process, a pathogenic process, or a response to a therapeutic intervention. | A large number of features derived from radiographic medical images using data-driven algorithms to identify patterns that emerge which may relate to clinical outcomes despite a lack of mechanistic association with a biological or pathogenic process. |

| Dimension | Low | High |

| Reference (or true) value of the measurand | Comparison with reference standard available | Comparison with reference standard not available |

| Biological Plausibility | Link to biology and biological-plausibility drives development/exploration | No a priori hypothesis made about the clinical relevance of extracted features |

| Clinical Use | Validated QIBs can be prospectively incorporated in RCTs based on biological rationale | Lack of biological rationale and limit the use in RCTs; mainly exploited in retrospective and prospective observation Studies |

| Model Development | A variety of methods may be used in model development (linear, regression, data-driven, AI-based) | A variety of methods may be used in model development (linear, regression, data-driven, AI-based) |

| Feature selection | May or may not | Feature selection is critical |

| Model Validation | Needed | Needed |

| Reproducibility and Repeatability (scaled and unscaled metrics) | Unscaled metrics of reproducibility important to define the precision of the model outcomes | Repeatability is used as a criterion for selecting eligible features |

| Pre-screening of Variables | Not needed; reproducibility of model inputs may be used as part of criteria to select input variables | Feature reduction is typically needed |

Most previously reported radiomic studies have been based on the extraction of features from a single imaging modality such as computed tomography (CT), T1- or T2-weighted MRI, or positron emission tomography (PET). However, in medical practice and research, imaging techniques from multiple modalities are being used more and more to obtain a set of features that form multi-modality, multiparametric DIMs. For example, it is recognized that the most complete picture of a prostate cancer patient is achieved with T2-weighted, diffusion weighted, dynamic contrast enhanced, and MR spectroscopy images 15. The multiple features are extracted from multimodal images, often providing more complete information about the tissue than from a single specific point of view 16-18.

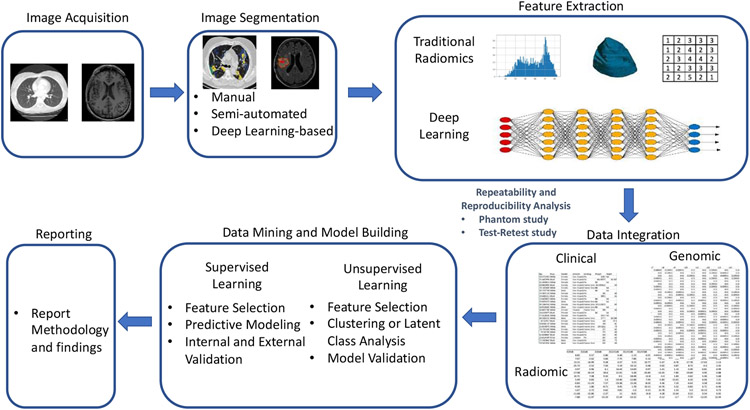

The workflow of a typical radiomics study can be briefly described as follows (Figure 1). A radiomics study starts with image acquisition. In routine clinical acquisition there are a variety of image techniques in use. Different vendors offer various image reconstruction methods that can be customized depending on the need. Segmentation of images into ROIs such as tumors is the second step in radiomics analysis. Manual segmentation by human experts is considered the gold standard, yet it is very time-consuming. Many semi-automatic and automatic segmentation methods have been developed across various image modalities and for different organs. The key aspect of radiomics is the extraction of high dimensional features to quantitatively describe attributes of these ROIs. These quantitative imaging features are data-driven descriptors extracted from the images by certain mathematical or statistical algorithms that exhibit different levels of complexities and properties. Non-radiomic features, such as clinical demographic data and patients’ genomic data, can be combined with radiomic features and the prediction target (outcome) to create a single dataset for the next stage of model building. The radiomic models could be unsupervised or supervised (developed from unlabeled or labeled data) depending on the study design. Both types of models include the steps of feature selection, model building and validation. Finally, the model outputs are reported transparently so that risk of bias and potential usefulness of models can be adequately assessed.

Figure 1:

A workflow of a typical radiomics study.

Radiomics investigators conduct studies of the repeatability or reproducibility of radiomic features to quantify the closeness of agreement of repeated measures of the features taken under the same or varying conditions, respectively. Inter-scanner and inter-vendor variability can be evaluated through phantom studies to characterize technical variation due to these factors. Organ motion, expansion, and shrinkage of the ROIs are potential additional sources of variability. A test-retest clinical study can be conducted to account for these sources of variability when measuring the stability of derived radiomic features. Balagurunathan et al. 19 identified repeatable radiomic features through a test-retest analysis in a lung computed tomographic (CT) image study. Traverso et al. 20 presented a systematic review of repeatability and reproducibility of radiomic features. They showed that first-order features (i.e., features that describe the distribution of individual voxel values without concern for spatial relationships) were overall more reproducible than shape metrics and textural features. Repeatability and reproducibility can be sensitive at various degrees to pre-analytical and analytical sources of variation such as image acquisition, reconstruction and preprocessing, and software used to extract radiomic features.

Reporting quality could be improved regarding details of image preprocessing, feature extraction software, and the statistical metric used to identify stable features. The Image Biomarker Standardization Initiative (IBSI) has recently defined reporting guidelines that indicate the elements that should be reported to facilitate the radiomic process 21 22. These are partially based on the works by 7, 20, 23, 24, and include eight topics: Patient information, image acquisition, reconstruction, registration, processing, segmentation, feature computation, and machine learning analysis. However, the recommendations for machine learning analysis in radiomics were relatively simplistic and only suggested following the Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis Or Diagnosis (TRIPOD) statement 25, 26 for reporting diagnostic and prognostic modeling. Although some aspects of the TRIPOD statement are applicable, there are many differences between building a machine learning model and a conventional regression model in radiomics. Yusuf et al. 27 recently conducted a systematic review assessing the reporting quality of studies validating models based on machine learning for clinical diagnosis. They showed that a large proportion of the qualified papers in their review lacked adequate details, making it difficult to replicate, assess, and interpret study findings.

Our paper aims to set guidelines on building machine learning models using DIMs in radiomics and correctly applying and reporting results. In Section 2, we review essential components of a radiomic study and discuss critical statistical analysis issues in those components. Section 3 presents checklist recommendations for reporting radiomic analysis and data modeling. Section 4 shows real case radiomic studies in lung cancer. Concluding remarks are given in Section 5.

2. Essential components of a radiomic study

In practice, radiomics is usually applied as a discovery tool rather than as an approach to measuring a specific quantity. Consequently, the measurement target may be articulated after, rather than before, radiomics experimentation. This has significant implications for statistically rigorous approaches to validation, as this is a departure from the paradigm developed for QIBs. When an apparently interesting or significant association is made by radiomics to a health outcome, a testable hypothesis must be formed explicitly linking the radiomics feature to the observed effect. Much has been written regarding radiomics, but for the QIBA methodology to be applicable 1-4, 28, 29, disciplined methodology needs to be followed. The following sections provide recommendations for such methodology.

2.1. Background and rationale

As with any scientific discipline, the overall scope of the research project and the potential impact should be assessed by reviewing relevant scientific literature. The choice of an imaging protocol, the ROIs and a prediction target should be clearly documented. Investigators should ensure that study participants are representative of the intended patient population and the DIMs are sufficiently represented in a sample so that the results can be reasonably generalized to the population of interest. The target patient population should be specified together with the role of the DIMs in clinical care.

2.2. Sample size determination

Sample sizes are often limited simply by the amount of data available, especially if the radiomic analyses are based on retrospectively-acquired data. Sample size determination is highly recommended for radiomics studies. Use of features that do have an objective truth basis can be considered to mitigate this, but lacking such, Cui and Gong 30 investigated the effect of machine learning methods and sample size on individualized behavioral prediction with neuroimaging functional connectivity features. The actual required sample size is context specific and depends on many factors, such as the outcome distribution in the study population, the number of radiomic predictors, and the expected predictive performance of the model.

When pilot data are not available, sample size determination could be based on characteristics of the statistical or machine learning model, allowed classification error upon generalization, and acceptable confidence in that error. For example, Baum and Haussler 31 showed the sample size determination for neural networks. For use with single hidden-layer feedforward neural networks with p nodes and w weights, a network trained on n samples with the rate 1 − ε/2 of the sample correctly classified, would approach a classification accuracy of 1 − ε on a test set, with the condition that .

A simple rule-based on “events-per-variable” (EPV) has been popular as a rule-of-thumb sample size estimation in clinical prediction model building. For logistic regression, the number of events is given by the size of the smallest of the outcome categories, and for Cox regression it is given by the number of uncensored events. The rule states that the EPV should at least be greater than 10 32-34. Later, Harrell 35 recommended a more stringent rule that EPV > 15. The rule oversimplifies the problem because many other quantities such as the correlation structure of variables may influence the sample size. However, this rule-of-thumb is easy to assess and can roughly inform the sample size of a validated prediction model.

When data from a pilot study are available, more accurate sample size estimation methods are available. Recently, Riley et al. 36, 37 proposed rigorous statistical algorithms to estimate the minimum sample size for developing a multivariable prediction model. For continuous outcomes, the minimum sample size should meet the four criteria: (a) a global shrinkage factor, S ≥ 0.9; (b) the absolute difference in the apparent and adjusted R-squared is less than or equal to 0.05; (c) precise estimation (a margin of error ≤ 10% of the true value) of the residual standard deviation; and (d) precise estimation of the mean predicted outcome value. For binary or time-to-event outcomes, the minimum sample size should meet the three criteria: (a) S ≥ 0.9; (b) the absolute difference of ≤ 0.05 in the apparent and adjusted Nagelkerke's R-squared (a generalization of R-squared to general regression models)38; (c) precise estimation of the estimate of the overall risk in the population. Here the global shrinkage factor, S, is a measure of overfitting. S can be estimated using bootstrapping or via a closed-form solution. We refer to Riley et al. 36, 37 for technical details. The number of subjects that meets all criteria for the specific type of outcome provides the minimum sample size required for model development for that outcome.

Another popular sample size estimation method for machine learning models is the learning curve fitting method. Through an empirical study, one obtains data points (nj, ej) that describes how the error rate of a model classifier (ej) is related to the size of the training sample (nj), where j = 1, … , m with m being the total number of instances. The classification accuracy as a function of training set size, called the learning curve, is usually well characterized by inverse power-laws: 39

where the parameter α is called the learning rate, α is called the decay rate, and b is the minimum error rate achievable.

2.3. Image acquisition and segmentation

The variations in image acquisition protocols and scanner parameters can introduce biases that are not due to underlying biologic effects. When possible, a standardized image acquisition protocol should be implemented on a pretested measurement device and kept consistent throughout the course of the study to eliminate unnecessary confounding variability 40, 41. There is often a consideration between tight control of the image acquisition protocol and the generalizability of the extracted radiomic features. A very tightly controlled study may be more inclined to pick up very real, but possibly not biologically relevant, signals. Meanwhile, a study considering a broader range of input images may struggle to discern the signal, but if such a signal is found, the results will be more generally applicable. Nevertheless, a standardized imaging protocol is critical to achieving a high-quality and reproducible radiomic study. Lambin et al. 7 provided excellent examples of how protocols should be planned and reported.

Image segmentation is a critical step since ROIs define the region in which radiomic features are calculated. Segmentation can be done manually (by experts), semi-automatically (using conventional image segmentation algorithms), or fully automatically (using recent popular deep learning methods). Manual and semi-automated segmentation may suffer from observer bias. Automated image segmentation using deep learning is quickly emerging and many algorithms have been developed 42, 43; however, their generalizability is a major limitation 44 A recommendation for standardized image segmentation may be found in the IBSI reference manual 21, which provides a guide to reducing measurement errors in segmentation.

2.4. Feature extraction

Feature extraction refers to the calculation of features that are used to quantify the characteristics within a segmented ROI. These features often include traditional engineered features (for example, intensity, shape, volume, and texture features) and deep learning features (for example, features generated utilizing a convolutional neural network) 45, 46. As identification of radiomic features is based on a hypothesis-free approach, there is no a priori hypothesis made about the clinical relevance of the features. Features without explicit definitions extracted by deep learning methods are considered as having a higher level of feature abstraction. Although deep learning has recently achieved impressive successes in several radiomic studies, a theoretical foundation is yet to be established. Choosing an appropriate and reliable deep learning network architecture still remains challenging. Since many different mathematical formulas and statistical/machine learning methods exist to calculate radiomic features, adherence to the IBSI guidelines is recommended.

2.5. Feature preprocessing

After feature extraction, several data preparation steps are often needed, which include data transformations and standardization, and handling of missing data and outliers. Radiomic features may be combined with patients’ clinical and demographic data, as well as genomic data if available. Additional data normalization steps like variable transformation and standardization can be critical and necessary due to the intrinsic differences in range, scale, and statistical distributions of radiomic features. Data normalization is also important when the data come from multiple sources or centers. Batch effects from different sources could confound the results of subsequent analyses. “Combine Batches” (ComBat) has recently been applied in radiomics studies as a harmonization method. ComBat is a statistical method initially developed to remove the batch effects in gene array analysis 47 Orlhac et al. 48 showed that ComBat successfully realigned feature distributions computed from different CT imaging protocols and recommended that it be employed in multicenter radiomic studies. The ComBat batch adjustment approach assumes that batch effects represent non-biological but systematic shifts in the mean of radiomic features within a processing batch (for example, an image scanner). Using an empirical Bayes procedure under a regression model, ComBat estimates the batch effect parameters and uses it to adjust the data for batch effects. We refer to Johnson et al. 47 for the model technical details.

A normalization method such as ComBat is necessary to disentangle feature values with confounding batch effects. The adjusted feature values can be then used for feature selection. However, in practice, batch effect correction may be infeasible. Features will be evaluated one subject at a time, usually without recourse to the batch used to measure them. Thus, batch effect normalization might not be practical for a commercial diagnostic device, where data normalization may need to be performed for a single subject. Instead, a reference database may be required to facilitate normalization 49.

Radiomic studies may have missing data, especially among clinical variables of patients. Techniques used to handle missing values should be evaluated and reported. Many machine learning methods for the subsequent prediction model building require complete observations for each case. The statistical power will be reduced by removing the cases with missing values. If data missingness restricts the number of usable samples, imputation methods can be applied in cases where data are missing at random. In particular, MissForest 50, a method of nonparametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data, and Multiple Imputation by Chained Equations (MICE) 51 have been shown as the two most reliable imputation methods in practice 52.

2.6. Feature selection

Feature selection refers to the process of selecting a subset of features for use in model building. Many radiomics studies involve a retrospective analysis to examine or identify radiomic features that have diagnostic or prognostic value. These studies provided a proof-of-concept for further investigation of radiomic features as DIMs. However, the number of extracted radiomic features is often very large. Feature selection is critical to avoid overfitting in prediction modeling.

Under a supervised learning framework, feature selection may be started with a univariable analysis. The significant features are identified based on a univariable test or model, such as t-test, Mann–Whitney U test, and logistic regression. In this analysis, it is important that the p-values must be corrected for multiple testing using a false discovery rate (FDR) or family-wise error rate (FWER) controlling methods, such as the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure 53 and Holm's step-down procedure 54. Then, one can consider to remove redundant features through a correlation analysis. Specifically, one computes the correlation matrix of the features. The absolute values of correlation coefficients greater than a pre-specified threshold (say, 0.90) are considered to be highly redundant. Two common approaches can be used to deal with the redundant features. If the correlation of two features exceeds the threshold, one looks at the mean absolute correlation of each feature and removes the feature with the largest mean absolute correlation 55. The other method calculates a single descriptor from the highly correlated variables. Dimensionality reduction techniques, such as principal component analysis, non-negative matrix factorization, and projection pursuit can also be used to obtain the single descriptor.

The remaining features serve as candidate variables in a multivariable machine learning model. Modern feature selection techniques, including lasso 56 and its variants, random forests 57, and boosting 58, can be used for further radiomic feature selection for the final model. The TRIPOD statement is the dominant guideline for building clinical prediction models. It emphasizes that using automated predictor selection strategies, such as Akaike information criterion (AIC), Bayesian information criterion (BIC), and p-value methods, during the multivariable modeling may yield overfitted and optimistic models, particularly when the sample size is small. Penalized regression methods have been shown to be a powerful tool for selecting a subset of important predictors and thus have played a central role in high-dimensional statistical modeling 59, 60.

Let (x1, y1), …, (xn, yn) be n independent and identically distributed random vectors, where yi is the response of interest and xi = (xi1, … , xip)T is the p-dimensional predictor. Assume that β = (β1, … , βp)T is a vector of the parameters of interest and Ln(β) is a loss function, for instance, the negative log-likelihood function. is a natural estimate of β. Under the penalization framework, feature selection and estimation of β are achieved simultaneously through computing , the estimate of β, which minimizes the penalized loss function

Here penλ(β) is the penalty function depending on the tuning parameter λ > 0. The goal of penalized regression is to obtain the subset of predictors that minimizes prediction error for a response variable. By imposing the constraint penλ(·) on the model parameters that causes regression coefficients for some variables to shrink toward zero, the penalized regression performs both feature selection and regularization in order to enhance the prediction accuracy and interpretability of the resulting model 60-62.

The least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (lasso) penalty, defined as , is the one of the most well-known penalty functions 56. Studies have shown its satisfactory selection performance in identifying a small number of representative predictors 59, 60. However, feature selection using lasso can be inconsistent under certain conditions 63, which motivated the development of many alternative penalties. When there is a group of highly correlated variables, lasso tends to select one variable from a group and ignore the others. To overcome the limitation, the elastic net adds a quadratic term to the penalty: 64. A non-concave penalty function, referred to as the smoothly clipped absolute deviation (SCAD) penalty, was proposed by Fan and Li 65, which corresponds to a quadratic spline function with knots at λ and αλ for some α > 2. The SCAD penalty is continuously differentiable on λ ∈ (−∞, 0) ∪ (0, ∞) but singular at λ = 0 with its derivatives zero outside the range [−αλ, αλ]. This property results in a sparse set of solution and approximately unbiased coefficients for large coefficients. The minimax concave penalty (MCP) is another alternative to get less biased regression coefficients in sparse models 66. Many other penalization methods have been developed to solve different problems in practice; see more discussion in Wu and Ma 67

Penalized feature selection has been criticized in that it suffers from the pitfall of not being stable in real applications 68. Bach 69 proposed a bootstrap lasso algorithm and showed that the feature selection results using lasso could be enhanced through bootstrapping. Meinshausen and Buhlmann 70 introduced a stability selection method based on subsampling in combination with high dimensional penalized selection algorithms. The method provides finite sample family-wise error control and improved selection and estimation. Recently, a general framework for controlling the FDR when performing feature selection, named the knockoff filter, was proposed and extensively investigated 71, 72. The basic idea is to construct extra variables, called “knockoff variables,” which have certain similar correlation structure as existing variables and allow for FDR control when existing feature selection methods, such as lasso, are applied. The main advantages of the knockoff over competing methods are that it achieves exact FDR control in finite sample settings, no matter the number of variables or size of regression coefficients.

For unsupervised learning, the goal of feature selection is to find the smallest feature subset that best uncovers underlying clusters. Two issues are involved in developing a feature selection algorithm for unlabeled data: the need for finding the number of clusters in conjunction with feature selection, and the need for normalizing the bias of feature selection criteria with respect to dimension. Many methods have been developed to solve the problems, see for example, Dy and Brodley 73 and Fop and Murphy 74. Nevertheless, the stability of feature selection is essential for the success and reproducibility of the final model. Feature selection should be accompanied by stability investigation 68. In the supplementary document, we present a simulation study to compare several modern feature selection techniques and show the importance of feature selection stability.

2.7. Model Training and Evaluation

Once feature selection is finalized, radiomic models can be built using a wide range of statistical or machine learning modeling methods. The choice of modeling technique affects prediction performance; hence, multiple-modeling methodology implementations are sometimes advocated 7. The key aspect is that, when reported, the model should be entirely reproducible.

In a machine learning analysis, it is common to use three datasets: (1) a training set, a portion of the primary data set used to fit the model; (2) an internal validation set, a portion of the primary data used to evaluate the model fit while tuning model hyperparameters; and (3) an external testing set, a dataset used to evaluate the model after it has been fully developed. Data in the test set should not have been used during any part of model development in order to avoid bias in the model performance evaluation.

We note that “validation” and “testing” are sometimes used interchangeably in the statistical and clinical literature, but we emphasize the difference between validation and test sets in building machine learning models in radiomics, as these three sets have unambiguous definitions in the machine learning field. An external testing set may be a partition of the original data; however, we prefer that it is from a completely separate data source, as a fully independent dataset can identify biases that have arisen during the selection of the study population used in model development.

When an external testing data set is not available, model evaluation may be limited to a training set and an internal validation set. For the analysis of internal validation, held-out data may be used in large sample scenarios. Bootstrapping, k-fold cross-validation (CV), and repeated k-fold CV are commonly used in practice for internal validation of medium- and small-sized data. Bootstrap validation involves sampling from the N data points N times with replacement to form a training set to which the model is fit. The model is then applied to the data points not selected during the bootstrap sampling to obtain an estimate of its performance. Average performance is obtained over many bootstrap samples 75-77. In k-fold CV, the data are randomly divided into k blocks of roughly equal size. Each of the blocks is left out in turn and the other k-1 blocks are used to train the model. The held-out block is then predicted and these predictions are summarized into certain type of performance measure. Repeated k-fold CV involves repeating the k-fold CV procedure multiple times and summarizing the mean result across all folds from all runs.

The k-fold CV or repeated k-fold CV procedure performs hyperparameter tuning and estimates the performance of a model at the same time. The model performance results could be over-optimistic because information may “leak” into the model and overfit the data. The magnitude of the effect mostly depends on the sample size and the stability of the model 78. In recent years, another technique called the nested CV has emerged as one of the popular methods for model validation 79. It is relatively straightforward as it merely is a nesting of two k-fold CV loops: the inner loop is responsible for the hyperparameter tuning, and the outer loop is responsible for estimating the model accuracy. The nested CV offers a solution for small sample cases that shows a low bias of model performance measures in practice where reserving data for an independent test set is not feasible. In the supplementary document, we present a simulation study to compare these internal validation methods. From our simulation and experiences, we suggest that the training and testing datasets in a radiomics study are selected and maintained to be appropriately independent of each other. All potential sources of dependence need to be considered and addressed to assure independence, for example, image acquisition, multi-site effects, and patient characteristics. All steps of model building in radiomics need to be cross-validated or independently validated before the model is applied to the testing set 80, 81. When an independent test set is not available, the nested CV is recommended as the method for internal validation.

The prediction model’s performance is generally evaluated using the area under the (receiver operating characteristic) curve (AUC, also known as the C-index) and Brier score 82. Other performance metrics like accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and Matthews’ correlation coefficient (MCC) could also be supplied 83. Finally, calibration is an important component of a prediction model in the claim, because the main concern for any patient is whether the risk given by a model is close to his or her true risk. Calibration could be displayed graphically in a calibration plot 84.

2.8. Reproducibility and Repeatability in Radiomics

The definitions of reproducibility and repeatability in radiomics can follow the definitions of reproducibility and repeatability in an QIB analysis defined in Raunig et al.2 Reproducibility represents the measurement precision under reproducibility conditions of measurement, which are derived from a set of conditions that includes different locations, operators, measuring systems, and replicate measurements on the same or similar objects. Repeatability represents the measurement precision under repeatability conditions of measurement, which are derived from a set of conditions that includes the same measurement procedure, same operators, same measuring system, same operating conditions and same physical location, and replicate measurements on the same or similar experimental units over a short period of time.

The lack of reproducibility of radiomic studies is considered a major challenge for this field. A standardized feature computation is essential for reproducible radiomics. IBSI recently conducted a study dedicated to standardizing commonly used radiomic features 21. Twenty-five research teams found agreement for calculation of 169 of 174 radiomics features derived from a digital phantom and a CT scan of a patient with lung cancer. Among these 169 standardized radiomics features, excellent reproducibility was achieved for 166 with CT, 164 with PET, and 164 with MRI. From that work, IBSI established reference values for 169 commonly used features and proposed a standard radiomics image processing scheme. IBSI suggested that a new radiomic study should state if the software used to extract the set of radiomic features can reproduce the IBSI feature reference values for the digital phantom and for one or more image processing configurations using the radiomics CT phantom. Reviewers may request that the researchers provide evidence of IBSI compliance for the analysis. In addition to standardized feature computation, the need for standardization and harmonization related to image acquisition, reconstruction, and segmentation remains for reproducible radiomics.

A test-retest repeatability analysis is also critical in radiomics since it ensures that the features obtained in one sitting are both representative and stable over time. It is critical to statistically characterize individual features as being repeatable, non-redundant, and having a large biological range that could be predictive of radiological diagnosis or prognosis. We suggest investigators could follow the three-step process proposed by Balagurunathan et al. 19 to identify the repeatable features using a test-retest study:

Step 1: Evaluate the agreement of extracted features between the test and retest experiments. Assessing agreement is commonly based on the scaled measure, concordance correlation coefficient (CCC) or the unscaled measure such as mean squared deviation (MSD), coverage probability (CP) and total deviation index (TDI). The CCC 85 is defined as

where μ1, , μ2, are the mean and variance of the feature for Test 1 and Test 2, respectively, and ρ is the correlation coefficient between Test 1 and Test 2.

The MSD is defined as the expectation of the squared difference of two readings, which can be expressed as . Here, σ12 is the covariance of the feature between Test 1 and Test 2. One uses an upper limit of MSD value, MSDu, to define satisfactory agreement as MSD ≤ MSDu. In practice, MSDu may not be known. If d0 is an acceptable difference between two tests, one may set 86.

CP is defined as the probability that the absolute difference between any two tests is less than d0. On the other hand, if we set π0 as the predetermined CP, we can find d0 so that the probability of absolute difference less than this boundary is π0. This boundary is called TDI.

Step 2: On a selected set of highly repeatable features (for example, CCC > 0.9), the next step is to select the features with a large inter-patient variability. It is expected that features will be more useful if they have a large biological range, which can be expressed as a dynamic range (DR). The DR for a feature is defined as the inverse of the average difference between measurements divided by the entire range of observed values in the test-retest sample:

where x1i and x2i (i = 1, … , m) are the feature value of the ith sample for Test 1 and Test 2, respectively and xmax and xmin are the maximum and minimum on the entire sample set {x11, … , x1m, x21, … , x2m}. Note that DR ∈ [0,1], where values close to 1 indicate large biological range relative to repeatability.

Step 3: The final step is to eliminate redundancies. The coefficients of determination R2 between the features that pass the thresholds in Step 1 and Step 2 are computed. It is equivalent to the square of the Pearson correlation coefficient in a simple linear regression. Features are grouped according to R2; for example, a group may consist of features such that the R2 between any two features is at least 0.9. A representative feature, typically the one with the highest DR, is identified from each group.

It should be noted that there has been heterogeneity in statistical metrics and cutoff values in repeatability and reproducibility analysis of radiomics. Traverso et al. 20 conducted a systematic review. The metrics encountered were intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) in 14 studies, CCC in 7 studies, Spearman rank correlation in 5 studies, and various descriptive measures of difference among the remaining 9 studies. The specific cutoff values used to segregate stable from unstable features were not always stated. When stated, the threshold values were highly study-dependent. This led to differences in the individual features that were deemed repeatable or reproducible, and there was no universal consensus. The differences in the metric choice made establishing a universal consensus difficult. Further investigation is needed in this line of research.

3. A Checklist for Reporting Radiomic Analysis and Data Modeling

Although data analysis and modeling strategies in a radiomic study may vary considerably depending on the problems, specific standards could enhance the validity and generalizability of a study. Reproducibility standards for machine learning in biology have been discussed 87, 88, but recommendations for machine learning analyses in radiomics are absent. Based on the discussion in Section 2, we provide a list of recommendations for analysis, modeling, and reporting in a radiomic study to make machine learning analyses in radiomics more reproducible in Table 2. We name the checklist the RANDAM (an abbreviation of “Radiomic ANalysis and DAta Modeling”) list. It includes five main components: design, data preparation, data analysis and modeling, reporting, and material availability. Table 2 includes many commonly-used statistical terms such as retrospective, prospective, cross-sectional, cohort, case series, prognostic, diagnostic, and intended use, etc. We refer to De et al. 89 for the formal definitions of those terms.

Table 2:

The Checklist for Radiomic ANalysis and DAta Modeling (RANDAM).

| Topic | Checklist item | |

|---|---|---|

| Design | Study purpose and endpoints | Definition of

|

| Sample size determination |

|

|

| Data Preparation | Radiomic quantification | Details of

Adherence to the IBSI guidelines is recommended. |

| Feature preprocessing |

|

|

| Missing data |

|

|

| Data Analysis and Modeling | Feature (pre-)screening |

|

| Model building | For supervised modeling

For unsupervised modeling

|

|

| Model validation |

|

|

| Model testing |

|

|

| Repeatability and/or reproducibility analysis |

|

|

| Reporting † |

|

|

| Material Availability |

|

|

At the design stage of a radiomic study, we recommend that investigators define the research questions, specify the study type and purpose, and clarify the intended use of results. We suggest that investigators perform a sample size estimation analysis and describe the rationale for why the proposed sample size is sufficient. In the data preparation component, adherence to the IBSI guidelines is recommended to perform image acquisition, reconstruction, registration, processing, segmentation, and feature computation.

The component of data analysis and modeling generally includes five parts: feature screening to remove redundant features; supervised or unsupervised model building; model validation; and model testing. The model techniques used should be suitable to the available data and support the alleviation of known risks, such as overfitting and performance degradation. During the model building, stability investigation is recommended to go along with feature selection. Investigators should specify the validation method used. External validation is preferable; nested CV is recommended for small or moderate sample studies when an independent validation set is unavailable. Performance metrics of the final model should be reported based on internal or external validation. We suggest reporting multiple performance metrics, such as C-index and Brier score. Other performance metrics like accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and MCC could be also supplied. When interrogators perform the model test on an independent set, they should lock all estimated parameters. Repeatability and/or reproducibility analysis can be added if additional data are available.

When reporting results, essential components in a report include characteristics of the data used to train and test the model, model summary (parameter estimates and their confidence intervals if available), model performance for appropriate subgroups, the model’s intended use and acceptable inputs, and limitations of the model and clinical impacts.

Open science facilitates knowledge transfer and reproducibility of a radiomics study. Making code and data publicly available will be particularly helpful to readers, and is a crucial step to reuse and evaluation. The open models thus can be monitored in “real world” use with a focus on maintained or improved performance. We believe that, by meeting the RANDAM list of recommendations, the community of researchers applying machine learning methods in radiomics can ensure that their analyses are more trustworthy.

4. Case Studies

In this section, we present real radiomics studies in lung cancer. Lung cancer is one of the most common malignancies globally, with the highest number of deaths of all cancers in the United States 90. Lung cancer grows fast; however, patients may not notice any symptoms early on. Most patients diagnosed with lung cancer present when cancer has spread to regional or distant sites. At these later stages of lung cancer, treatment is not curative, whereas if detected early in its course, the chances of cure are high. For these reasons, early detection of lung cancer is paramount. The National Lung Screening Trial (NLST) showed that three annual rounds of low-dose chest computed tomography (LDCT) screening in a high-risk cohort reduced lung cancer mortality after 7 years by 20% in comparison to screening with chest radiography 91. As a result of this trial and subsequent modeling studies, lung cancer screening programs using LDCT imaging are currently being implemented in the U.S.

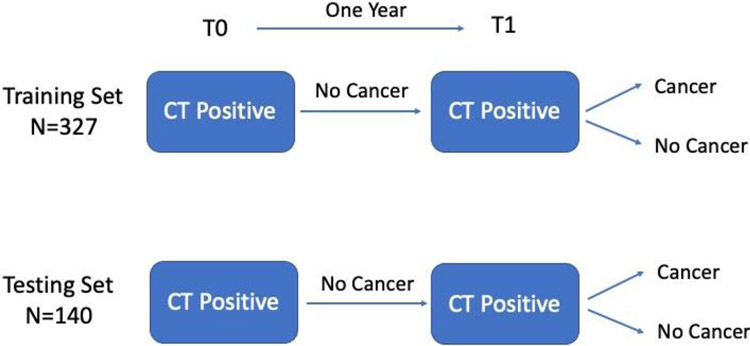

In the first example, LDCT scans from the NLST were utilized to generate radiomic features from baseline and follow-up screening intervals with the goal of building prediction models of lung cancer. The LDCT images were obtained through the National Cancer Institute Cancer Data Access System. A cohort of participants from the NLST were identified based on their screening history. All participants had a T0 positive screen (i.e., a nodule ≥ 4 mm or other clinically significant abnormality) that was not diagnosed as lung cancer. One year after T0 screen, the participants had another positive screen at T1. The participants then were diagnosed whether had a lung cancer. The details of the demographics and clinical characteristics are described in Hawkins et al. 92. The controls (i.e. negative cases) and lung cancer cases were frequency matched approximately 2:1 on age, sex, and smoking history. The data were randomly split into a training set (327 subjects) and a testing set (140 subjects). The study design is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2:

The study design of the lung cancer screening study.

Radiomic feature extraction was conducted by radiologists from the Moffitt Cancer Center. For each nodule of interest in the cohort, a 3D image segmentation using Definiens Developer XD software (Munich, Germany) 93 was performed. It is a semi-automated segmentation depending on the experts to locate the nodule, and the nodule is segmented by the Definiens software with a single-click segmentation approach. After segmentation, Definiens Developer XD extracts the radiomic features, including size, volume, location, gray level run-length matrix (GLRLM), gray level co-occurrence matrix (GLCM), pixel histogram, Laws, and wavelet features etc. for a total number of 219 extracted features. A complete list of the features can be found in Balagurunathan et al. 19.

The purpose of this study was to evaluate the effects of different modeling strategies using real radiomics features. For the full list of the candidate variables, we consider the 219 radiomics features at T1 and the 219 delta radiomic features (T1 – T0). We built 24 prediction models by considering the following factors:

Feature computations: (a) Raw features (b) features with appropriate transformation

Feature normalization: (a) No (b) Yes

Feature selection: (a) No feature selection (b) lasso (c) Stability selection

Model: (a) Logistic regression (b) Random Forests

We only focus on a workflow of separate steps on feature selection and final model building. Many machine learning and penalization approaches can simultaneously conduct feature selection and model estimation. A more comprehensive numerical study could be done to compare the unified modeling versus separate analysis in the future.

Internal validation involved repeated 10-fold CV applied on the training set, and external validation was applied on the testing set. We consider two metrics to assess the performance of the prediction models: the C-index and Brier Score. The C-index is interpreted as the probability that a randomly selected subject who experienced the outcome will have a higher predicted probability of having the outcome occur than a randomly selected subject who did not experience the outcome. It can also be interpreted as the rank correlation between predicted probabilities of the outcome occurring and the observed response. It is equal to the AUC and ranges from 0 to 1. The Brier Score, a metric between 0 to 1, measures the accuracy of probabilistic predictions. A lower Brier score indicates more accurate predictions. It is an improvement over the C-index to evaluate the performance of prediction models, because it captures both calibration and discrimination aspects 94.

From Table 3, we notice that, for the high-dimensional variable modeling, the machine learning technique, such as random forests, seems to perform better than conventional logistic regression. This is not surprising since the random forest is a nonlinear classifier and is robust to outliers. Feature selection is critical in model building. Models without feature selection result in overfitting, especially when using conventional logistic regression. The standard lasso is often unstable when selecting the variables. The subsampling-based stability selection seems to outperform to tether. Internal repeated CV is not enough to evaluate the “true” prediction performance of the model. For logistic regression, both C-index and Brier score in interval validation are too optimistic compared with external validation. For random forests, the metrics in internal validation are close to the ones in external validation, but internal validation is still slightly over-optimistic. Appropriate variable transformation seems useful to improve the prediction power. In this study, variable normalization seemed not to make a big difference in model building.

Table 3:

Assessing the prediction performance of the prediction models using T1 features and their delta features for the lung cancer study. NA is due to the fact that the logistic regression cannot converge in those cases of the high-dimensional variables.

| Feature selection |

Feature normalization |

Feature generation |

Method | # Features (# Reproducible features) |

Internal Repeated CV |

External Validation |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-index | Brier | C-index | Brier | |||||

| lasso | No | log-transform | logistic regression | 83 (9) | 0.891 | 0.000 | 0.756 | 0.232 |

| lasso | No | log-transform | random forest | 83 (9) | 0.864 | 0.053 | 0.859 | 0.100 |

| lasso | No | raw | logistic regression | 29 (7) | 0.908 | 0.075 | 0.752 | 0.160 |

| lasso | No | raw | random forest | 29 (7) | 0.887 | 0.033 | 0.810 | 0.121 |

| lasso | Yes | log-transform | logistic regression | 75 (10) | 0.885 | 0.000 | 0.792 | 0.215 |

| lasso | Yes | log-transform | random forest | 75 (10) | 0.865 | 0.076 | 0.859 | 0.097 |

| lasso | Yes | raw | logistic regression | 34 (9) | 0.911 | 0.058 | 0.778 | 0.173 |

| lasso | Yes | raw | random forest | 34 (9) | 0.894 | 0.046 | 0.822 | 0.107 |

| Stability | No | log-transform | logistic regression | 44 (10) | 0.916 | 0.041 | 0.810 | 0.142 |

| Stability | No | log-transform | random forest | 44 (10) | 0.879 | 0.082 | 0.827 | 0.094 |

| Stability | No | raw | logistic regression | 43 (10) | 0.909 | 0.049 | 0.752 | 0.187 |

| Stability | No | raw | random forest | 43 (10) | 0.878 | 0.087 | 0.775 | 0.112 |

| Stability | Yes | log-transform | logistic regression | 44 (10) | 0.916 | 0.041 | 0.810 | 0.142 |

| Stability | Yes | log-transform | random forest | 44 (10) | 0.879 | 0.082 | 0.827 | 0.094 |

| Stability | Yes | raw | logistic regression | 43 (10) | 0.909 | 0.049 | 0.752 | 0.187 |

| Stability | Yes | raw | random forest | 43 (10) | 0.877 | 0.087 | 0.775 | 0.112 |

| No | No | log-transform | logistic regression | 438 (46) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| No | No | log-transform | random forest | 438 (46) | 0.859 | 0.044 | 0.842 | 0.108 |

| No | No | raw | logistic regression | 438 (46) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| No | No | raw | random forest | 438 (46) | 0.855 | 0.035 | 0.853 | 0.104 |

| No | Yes | log-transform | logistic regression | 438 (46) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| No | Yes | log-transform | random forest | 438 (46) | 0.859 | 0.044 | 0.842 | 0.108 |

| No | Yes | raw | logistic regression | 438 (46) | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| No | Yes | raw | random forest | 438 (46) | 0.857 | 0.037 | 0.847 | 0.106 |

Balagurunathan et al. 95 conducted a test-retest study and identified 23 high repeatable features (CCC and DR > 0.9) among the 219 radiomics feature. In their study, the acquisition and processing parameters were fixed. Confounding was minimized by obtaining two separate CT scans from the same patient on the same machine using the same parameters, within 15 min of each other. The list of the repeatable features selected by different preprocessing and feature selection methods is provided in Table 4. We note that 8~10 repeatable features are stably selected no matter which method is applied.

Table 4:

The list of the repeatable features that are selected by different preprocessing and feature selection methods.

| Repeatable features | Feature selection: lasso | Feature selection: Stability | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No normalization | Normalized | No normalization | Normalized | |||||

| Log- transformed |

Raw | Log- transformed |

Raw | Log- transformed |

Raw | Log- transformed |

Raw | |

| Longest Diameter [mm] | D | D | D | D | D | D | D | D |

| Short Axis * Longest Diameter [mm] | D | D | ||||||

| Short Axis [mm] | X | XD | X | XD | X | XD | X | XD |

| Volume [cm_] | ||||||||

| Area (Pxl) | ||||||||

| Thickness (Pxl) | ||||||||

| Length (Pxl) | D | D | D | D | ||||

| Density | XD | XD | D | D | ||||

| Shape index | D | D | D | D | ||||

| 8a_3D_Is_Attached_To_Pleural_Wall | ||||||||

| 8b_3D_Relative_Border_To_Lung | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

| 9d_3D_AV_Mst_COG_To_Border_[mm] | ||||||||

| 9e_3D_SD_Dist_COG_To_Border_[mm] | ||||||||

| 9f_3D_MIN_Dist_COG_To_Border_[mm] | ||||||||

| 10a_3D_Relative_Volume_AirSpaces | D | X | D | X | X | X | ||

| Mean [HU] | D | XD | XD | XD | XD | XD | XD | |

| Histogram ENTROPY Layer 1 | D | D | ||||||

| avgGLN | X | D | X | D | ||||

| avgLGRE | X | X | X | X | X | X | ||

| 3D Laws features E5 L5 S5 Layer 1 | ||||||||

| 3D Laws features E5 S5 E5 Layer 1 | ||||||||

| 3D Laws features L5 S5 W5 Layer 1 | ||||||||

| 3D Laws features R5 S5 W5 Layer 1 | ||||||||

X: Original variable was selected

D: Delta variable was selected

We also compared the prediction performance of the prediction models using the 23 repeatable T1 features (and their delta features) versus the ones using all 219 features (and their delta features). The comparison results are presented in Table 5. We find that, by using the 23 repeatable features, we can obtain a prediction model that has a similar prediction performance as using all 219 features. Indeed, the best model was the one trained on the repeatable features and their delta features. Moreover, the models trained on the repeatable feature subset had the biggest performance improvement when delta features were combined with T1 features. The C-index in external validation increased from 0.780 to 0.874. A possible explanation is that the repeatable features have been approved to be highly repeatable based on the three-step analysis in Section 2.8. They are helpful in the identification of a reliable model. Another interesting finding is that the traditional logistic regression performed well when the dimension of the candidate variables was small. Therefore, identifying repeatable features is critical for developing stable and reproducible models. Repeatability and/or reproducibility study is recommended for any radiomics study when a budget is allowed.

Table 5:

Accessing the prediction performance of the prediction models using the 23 reproducible T1 features and their delta features for the lung cancer study.

| Original dataset |

Feature selection |

Feature normalization |

Feature generation |

Method | # of Features |

Internal Repeated CV |

External Validation |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C- index |

Brier | C- index |

Brier | ||||||

| T1 + delta | Stability | Yes/No* | log-transform | random forest | 44 | 0.879 | 0.082 | 0.827 | 0.094 |

| T1 only | Stability | Yes/No* | raw | random forest | 20 | 0.889 | 0.107 | 0.821 | 0.113 |

| Repeatable 23 features + delta | Stability | Yes/No* | log-transform | logistic regression | 7 | 0.850 | 0.118 | 0.874 | 0.093 |

| Repeatable 23 features, No delta | lasso | Yes | log-transform | logistic regression | 12 | 0.844 | 0.130 | 0.780 | 0.121 |

“Yes/No” means that there is no difference in terms of performance using normalization or without normalization.

We conducted another real case study of machine learning survival analysis using a subset in the radiomics study by Aerts et al. 96. This case study demonstrated a practical workflow of analyzing the high-dimensional radiomic features with a time-to-event outcome based on our RANDAM recommendations. The detailed statistical report, the line-by-line R code file, and the datasets can be found in the online supplementary materials.

5. Closing Remarks

Parameters derived from medical imaging are used clinically to help detect disease, identify phenotypes, define longitudinal change, and predict outcomes. In mpQIB studies, multiple QIBs are considered together to improve the clinical use potential. This paper is the fifth in a five-part series on statistical methodology for mpQIB performance assessment. We focus on derived features selected from radiomic analysis. Unlike studies in which features are evaluated for association with an outcome determined by an objective truth basis, radiomic analyses involve high-dimensional feature extraction from radiographic medical images using data-driven algorithms. These radiomic features are DIMs because they are quantitative measures discovered under a data-driven framework from images beyond visual recognition but evident as patterns irrespective of ground truth basis.

We provide a list of recommendations, RANDAM, for statistical analysis, modeling, and reporting in a radiomic study. RANDAM contains five main components: design, data preparation, data analysis and modeling, reporting, and material availability. It can be utilized as a guideline in the design, conduct, analysis, and reporting of radiomics studies. We are hopeful this checklist will help radiomic developers conduct high-quality and reproducible studies.

One of the biggest challenges to establishing radiomics-based models as DIMs in clinical decision support is the open science, including sharing image data and metadata across multiple sites, and making software code and models publicly available. Open science facilitates knowledge transfer and reproducibility of a radiomics study. Making code and data publicly available is a key step to reuse and evaluation. The open models, thus, can be monitored in “real world” use with a focus on maintained or improved performance. To date, remarkable collaborative efforts have been made in quantitative image biomarkers, including the RSNA’s QIBA and the National Cancer Institute’s (NCI) Quantitative Imaging Network (QIN). Radiomics has excellent potential to expand the horizons of medical imaging toward better precision medicine.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Contributor Information

Xiaofeng Wang, Department of Quantitative Health Sciences, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland OH, USA.

Gene Pennello, Center for Devices and Radiological Health, US Food and Drug Administration Division of Imaging, Diagnostic and Software Reliability, Office of Science and Engineering Laboratories, Center for Devices and Radiological Health, US Food and Drug Administration, 10903 New Hampshire Avenue, Silver Spring, MD 20993.

Nandita M. deSouza, Division of Radiotherapy and Imaging, The Institute of Cancer Research and Royal Marsden Hospital, London, UK; European Imaging Biomarkers Alliance, European Society of Radiology

Erich P. Huang, Division of Cancer Treatment and Diagnosis, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA

Andrew J. Buckler, Euclid Bioimaging, Inc., Boston, MA, USA

Huiman X. Barnhart, Department of Biostatistics and Bioinformatics, Duke University, Durham, NC, USA

Jana G. Delfino, Center for Devices and Radiological Health, US Food and Drug Administration. Silver Spring, MD

David L. Raunig, Data Science Institute, Statistical and Quantitative Sciences, Takeda Pharmaceuticals America Inc, Lexington, MA, USA

Lu Wang, Department of Quantitative Health Sciences, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland OH, USA.

Alexander R. Guimaraes, Department of Diagnostic Radiology, Oregon Health & Sciences University, Portland, OR, USA

Timothy J. Hall, Department of Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA

Nancy A. Obuchowski, Department of Quantitative Health Sciences, Lerner Research Institute, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland OH, USA

References

- 1.Sullivan DC, Obuchowski NA, Kessler LG, et al. Metrology Standards for Quantitative Imaging Biomarkers. Radiology 2015; 277: 813–825. 2015/August/13. DOI: 10.1148/radiol.2015142202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Raunig DL, McShane LM, Pennello G, et al. Quantitative imaging biomarkers: a review of statistical methods for technical performance assessment. Stat Methods Med Res 2015; 24: 27–67. 2014/June/13. DOI: 10.1177/0962280214537344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Obuchowski NA, Reeves AP, Huang EP, et al. Quantitative imaging biomarkers: a review of statistical methods for computer algorithm comparisons. Stat Methods Med Res 2015; 24: 68–106. 2014/June/13. DOI: 10.1177/0962280214537390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kessler LG, Barnhart HX, Buckler AJ, et al. The emerging science of quantitative imaging biomarkers terminology and definitions for scientific studies and regulatory submissions. Stat Methods Med Res 2015; 24: 9–26. 2014/June/13. DOI: 10.1177/0962280214537333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gillies RJ, Kinahan PE and Hricak H. Radiomics: Images Are More than Pictures, They Are Data. Radiology 2016; 278: 563–577. 2015/November/19. DOI: 10.1148/radiol.2015151169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aerts HJ. The potential of radiomic-based phenotyping in precision medicine: a review. JAMA oncology 2016; 2: 1636–1642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lambin P, Leijenaar RTH, Deist TM, et al. Radiomics: the bridge between medical imaging and personalized medicine. Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2017; 14: 749–762. 2017/October/05. DOI: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lambin P, Rios-Velazquez E, Leijenaar R, et al. Radiomics: extracting more information from medical images using advanced feature analysis. European journal of cancer 2012; 48: 441–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alahmari SS, Cherezov D, Goldgof D, et al. Delta Radiomics Improves Pulmonary Nodule Malignancy Prediction in Lung Cancer Screening. IEEE Access 2018; 6: 77796–77806. 2019/January/05. DOI: 10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2884126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tixier L, Le Rest CC, Hatt M, et al. Intratumor heterogeneity characterized by textural features on baseline 18L-LDGPET images predicts response to concomitant radiochemotherapy in esophageal cancer. JNuclMed 2011; 52: 369–378. 2011/February/16. DOI: 10.2967/jnumed.110.082404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun R, Limkin EJ, Vakalopoulou M, et al. A radiomics approach to assess tumour-infiltrating CD8 cells and response to anti-PD-1 or anti-PD-L1 immunotherapy: an imaging biomarker, retrospective multicohort study. Lancet Oncol 2018; 19: 1180–1191. 2018/August/19. DOI: 10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30413-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aerts HJ, Velazquez ER, Leijenaar RT, et al. Decoding tumour phenotype by noninvasive imaging using a quantitative radiomics approach. Nat Commun 2014; 5: 4006. 2014/June/04. DOI: 10.1038/ncomms5006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Drabycz S, Roldan G, de Robles P, et al. An analysis of image texture, tumor location, and MGMT promoter methylation in glioblastoma using magnetic resonance imaging. Neuroimage 2010; 49: 1398–1405. 2009/October/03. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2009.09.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gutman DA, Dunn WD Jr., Grossmann P, et al. Somatic mutations associated with MRI-derived volumetric features in glioblastoma. Neuroradiology 2015; 57: 1227–1237. 2015/September/05. DOI: 10.1007/s00234-015-1576-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kurhanewicz J, Vigneron D, Carroll P, et al. Multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging in prostate cancer: present and future. Curr Opin Urol 2008; 18: 71–77. DOI: 10.1097/MOU.0b013e3282f19d01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parekh VS and Jacobs MA. Multiparametric radiomics methods for breast cancer tissue characterization using radiological imaging. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2020; 180: 407–421. 2020/February/06. DOI: 10.1007/s10549-020-05533-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhang B, Tian J, Dong D, et al. Radiomics features of multiparametric MRI as novel prognostic factors in advanced nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Clinical Cancer Research 2017; 23: 4259–4269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ng S-H, Lin C-Y, Chan S-C, et al. Clinical utility of multimodality imaging with dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI, diffusion-weighted MRI, and 18F-FDG PET/CT for the prediction of neck control in oropharyngeal or hypopharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma treated with chemoradiation. PLoS One 2014; 9: el15933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Balagurunathan Y, Kumar V, Gu Y, et al. Test-retest reproducibility analysis of lung CT image features. J Digit Imaging 2014; 27: 805–823. 2014/July/06. DOI: 10.1007/s10278-014-9716-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Traverso A, Wee L, Dekker A, et al. Repeatability and Reproducibility of Radiomic Features: A Systematic Review. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2018; 102: 1143–1158. 2018/September/02. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.05.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zwanenburg A, Vallieres M, Abdalah MA, et al. The Image Biomarker Standardization Initiative: Standardized Quantitative Radiomics for High-Throughput Image-based Phenotyping. Radiology 2020; 295: 328–338. 2020/March/11. DOI: 10.1148/radiol.2020191145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zwanenburg AL, Stefan; Vallieres M; Lock S. Image biomarker standardisation initiative reference manual. arXiv preprint 2016; arXiv:1612.07003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sanduleanu S, Woodruff HC, De Jong EEC, et al. Tracking tumor biology with radiomics: a systematic review utilizing a radiomics quality score. Radiotherapy and Oncology 2018; 127: 349–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sollini M, Cozzi L, Antunovic L, et al. PET Radiomics in NSCLC: state of the art and a proposal for harmonization of methodology. Scientific reports 2017; 7: 1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Collins GS, Reitsma JB, Altman DG, et al. Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): the TRIPOD statement. Ann Intern Med’2015; 162: 55–63. 2015/January/07. DOI: 10.7326/M14-0697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moons KG, Altman DG, Reitsma JB, et al. Transparent Reporting of a multivariable prediction model for Individual Prognosis or Diagnosis (TRIPOD): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med’2015; 162: W1–73. 2015/January/07. DOI: 10.7326/M14-0698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yusuf M, Atal I, Li J, et al. Reporting quality of studies using machine learning models for medical diagnosis: a systematic review. BMJ open 2020; 10: e034568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Obuchowski NA, Barnhart HX, Buckler AJ, et al. Statistical issues in the comparison of quantitative imaging biomarker algorithms using pulmonary nodule volume as an example. Stat Methods Med Res 2015; 24: 107–140. 2014/June/13. DOI: 10.1177/0962280214537392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huang EP, Wang XF, Choudhury KR, et al. Meta-analysis of the technical performance of an imaging procedure: guidelines and statistical methodology. Stat Methods Med Res 2015; 24: 141–174. 2014/May/30. DOI: 10.1177/0962280214537394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cui Z and Gong G. The effect of machine learning regression algorithms and sample size on individualized behavioral prediction with functional connectivity features. Neuroimage 2018; 178: 622–637. 2018/June/06. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baum E and Haussler D. What size net gives valid generalization? Advances in neural information processing systems 1988; 1: 81–90. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harrell FE, Lee KL, Califf RM, et al. Regression modelling strategies for improved prognostic prediction. Statistics in medicine 1984; 3: 143–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peduzzi P, Concato J, Kemper E, et al. A simulation study of the number of events per variable in logistic regression analysis. J Clin Epidemiol 1996; 49: 1373–1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vittinghoff E and McCulloch CE. Relaxing the rule of ten events per variable in logistic and Cox regression. Am J Epidemiol 2007; 165: 710–718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Harrell FE. Regression modeling strategies: with applications to linear models, logistic and ordinal regression, and survival analysis. 2nd Edition ed. New York: Springer, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Riley RD, Snell KIE, Ensor J, et al. Minimum sample size for developing a multivariable prediction model: Part I–Continuous outcomes. Statistics in medicine 2019; 38: 1262–1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riley RD, Snell KI, Ensor J, et al. Minimum sample size for developing a multivariable prediction model: PART II - binary and time-to-event outcomes. Stat Med 2019; 38: 1276–1296. 2018/October/26. DOI: 10.1002/sim.7992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nagelkerke NJD. A note on a general definition of the coefficient of determination. Biometrika 1991; 78: 691–692. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mukherjee S, Tamayo P, Rogers S, et al. Estimating dataset size requirements for classifying DNA microarray data. J Comput Biol 2003; 10: 119–142. 2003/June/14. DOI: 10.1089/106652703321825928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Buckler AJ, Bresolin L, Dunnick NR, et al. A collaborative enterprise for multi-stakeholder participation in the advancement of quantitative imaging. Radiology 2011; 258: 906–914. 2011/February/23. DOI: 10.1148/radiol.10100799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shukla-Dave A, Obuchowski NA, Chenevert TL, et al. Quantitative imaging biomarkers alliance (QIBA) recommendations for improved precision of DWI and DCE-MRI derived biomarkers in multicenter oncology trials. J Magn Reson Imaging 2019; 49: e101–e121. 2018/November/20. DOI: 10.1002/jmri.26518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hesamian MH, Jia W, He X, et al. Deep learning techniques for medical image segmentation: achievements and challenges. Journal of digital imaging 2019; 32: 582–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Minaee S, Boykov YY, Porikli F, et al. Image segmentation using deep learning: A survey. Ieee T Pattern Anal 2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.van Timmeren JE, Cester D, Tanadini-Lang S, et al. Radiomics in medical imaging-"how-to" guide and critical reflection. Insights Imaging 2020; 11: 91. 2020/August/14. DOI: 10.1186/s13244-020-00887-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Parmar C, Barry JD, Hosny A, et al. Data Analysis Strategies in Medical Imaging. Clin Cancer Res 2018; 24: 3492–3499. 2018/March/28. DOI: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vial A, Stirling D, Field M, et al. The role of deep learning and radiomic feature extraction in cancer-specific predictive modelling: a review. Translational Cancer Research 2018; 7: 803–816. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Johnson WE, Li C and Rabinovic A. Adjusting batch effects in microarray expression data using empirical Bayes methods. Biostatistics 2007; 8: 118–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Orlhac F, Frouin F, Nioche C, et al. Validation of A Method to Compensate Multicenter Effects Affecting CT Radiomics. Radiology 2019; 291: 53–59. 2019/January/30. DOI: 10.1148/radiol.2019182023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Težak Ž, Ranamukhaarachchi D, Russek-Cohen E, et al. FDA perspectives on potential microarray-based clinical diagnostics. Human genomics 2006; 2: 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Stekhoven DJ and Buhlmann P. MissForest--non-parametric missing value imputation for mixed-type data. Bioinformatics 2012; 28: 112–118. 2011/November/01. DOI: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Buuren Sv and Groothuis-Oudshoorn K. mice: Multivariate imputation by chained equations in R. Journal of statistical software 2010: 1–68. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shah AD, Bartlett JW, Carpenter J, et al. Comparison of random forest and parametric imputation models for imputing missing data using MICE: a CALIBER study. Am J Epidemiol 2014; 179: 764–774. 2014/March/05. DOI: 10.1093/aje/kwt312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Benjamini Y and Hochberg Y. Controlling the false discovery rate: a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal statistical society: series B (Methodological) 1995; 57: 289–300. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Holm S A simple sequentially rejective multiple test procedure. Scandinavian journal of statistics 1979: 65–70. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kuhn M and Johnson K. Applied predictive modeling. Springer, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tibshirani R Regression shrinkage and selection via the lasso. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological) 1996; 58: 267–288. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Genuer R, Poggi J-M and Tuleau-Malot C. Variable selection using random forests. Pattern recognition letters 2010; 31: 2225–2236. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hofner B, Hothorn T, Kneib T, et al. A framework for unbiased model selection based on boosting. Journal of Computational and Graphical Statistics 2011; 20: 956–971. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fan J and Lv J. A selective overview of variable selection in high dimensional feature space. Statistica Sinica 2010; 20: 101. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Huang J, Breheny P and Ma S. A selective review of group selection in high-dimensional models. Statistical science: a review journal of the Institute of Mathematical Statistics 2012; 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fan J and Lv J. A selective overview of variable selection in high dimensional feature space. Statistica Sinica 2010; 20: 101–148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]