Abstract

Purpose:

Pathogenic variants in genes involved in the epigenetic machinery are an emerging cause of neurodevelopment disorders (NDDs). Lysine-demethylase 2B (KDM2B) encodes an epigenetic regulator and mouse models suggest an important role during development. We set out to determine whether KDM2B variants are associated with NDD.

Methods:

Through international collaborations, we collected data on individuals with heterozygous KDM2B variants. We applied methylation arrays on peripheral blood DNA samples to determine a KDM2B associated epigenetic signature.

Results:

We recruited a total of 27 individuals with heterozygous variants in KDM2B. We present evidence, including a shared epigenetic signature, to support a pathogenic classification of 15 KDM2B variants and identify the CxxC domain as a mutational hotspot. Both loss-of-function and CxxC-domain missense variants present with a specific subepisignature. Moreover, the KDM2B episignature was identified in the context of a dual molecular diagnosis in multiple individuals. Our efforts resulted in a cohort of 21 individuals with heterozygous (likely) pathogenic variants. Individuals in this cohort present with developmental delay and/or intellectual disability; autism; attention deficit disorder/attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; congenital organ anomalies mainly of the heart, eyes, and urogenital system; and subtle facial dysmorphism.

Conclusion:

Pathogenic heterozygous variants in KDM2B are associated with NDD and a specific epigenetic signature detectable in peripheral blood.

Keywords: Human Genetics, KDM2B, MDEMs, Methylation signatures, Neurodevelopmental disorders

Introduction

Genes encoding for epigenetic regulators are an emerging class of monogenic disease genes associated with neurodevelopment disorders (NDDs). This group of disorders, collectively referred to as “Mendelian Disorders of the Epigenetic Machinery” (MDEMs), present with neurodevelopmental delay, congenital malformations, and/or growth abnormalities.1 For an increasing number of MDEMs, distinct genome-wide methylation signatures (episignatures) have been identified.2 These signatures present as valuable tools in clinical practice because they are unique for each disorder and can be detected in peripheral blood samples, providing a robust and easily accessible diagnostic tool that enables the diagnosis of uncharacterized individuals as well as the identification of novel pathogenic variants through pinpointing the causal gene.3

The KDM2B gene (lysine-demethylase 2B, also called FBXL10, NDY1, CXXC2, and JHDM1B; OMIM 609078) encodes for a well-studied component of the epigenetic machinery. The canonical, full-length KDM2B protein acts by demethylating lysine residues K4, K36, and K79 of histone 3.4–11 This catalytic activity is provided by the JmjC domain, which is conserved from yeast to human.4,9 The CxxC domain directs KDM2B to promotor regions by binding unmethylated CpG dinucleotides.12–14 This DNA-binding capacity has been linked to the recruitment of the polycomb repressive complex 1 to developmental genes.10,15,16 KDM2B has been implicated in many biological processes, including cell cycle regulation, metabolic regulation, and DNA-damage repair.11,13,17,18 Moreover, in line with a central role in epigenetic and transcriptional regulation, KDM2B is essential for organism development and regulates cellular differentiation.12

KDM2B, together with SETD1B, has been implicated as a disease-causing gene in the rare 12q24.31 microdeletion syndrome.19–21 In addition, 2 sporadic patients and 1 family with heterozygous KDM2B missense variants have been described.22–24 A monogenic KDM2B-related human disorder has however not been delineated, and the significance of the reported variants remains uncertain.

Materials and Methods

Inclusion criteria and data collection

Individuals were included based on the identification of a heterozygous KDM2B suspected to be pathogenic on the basis of in silico predictions and/or inheritance. Individuals carrying biallelic variants of uncertain significance (VUS) were not considered for this study. Individual 1 was identified as the index patient after a KDM2B variant was annotated to be of interest after diagnostic trio exome sequencing. Families 2 to 5 were included after local, in-house database searches. All remaining individuals were included after personal communication, literature search, or from searches using the GeneMatcher platform.25 For the published cases, we contacted the original authors for updated clinical information. For all individuals, clinical and genetic data were collected through a standardized spreadsheet, which was completed by the respective physicians and/or researchers.

Genetic variant detection

Variants in individuals/families 24, 25, 29, 30, and 34 were identified as described before.19,20,22,24 The variant in individual 4.3 was identified through targeted Sanger sequencing. All other variants were detected through clinical and/or research-based exome sequencing.

Analysis and classification of KD2MB variants

Structural analysis of variants was performed using Pymol (The Pymol Molecular Graphics System, Version 2.5, Schrödinger, LLC). All Figures were generated using Pymol. Four in silico prediction algorithms were consulted: Sorting Intolerant from Tolerant, Metadome, MutationTaster, and Polymorphism Phenotyping v2.26–29 All variants were manually analyzed using Alamut Visual v2.15 (Sophia Genetics). Variants were classified according to the 2015 American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics/Association for Molecular Pathology guidelines.30 Episign results were used to support classification according to criterium Pathogenic Strong 3 (PS3), and Pathogenic Moderate 1 (PM1) was applied for variants in the CxxC domain.

Development of episignature

Materials and methods associated with episignature development are provided as Supplemental Methods in the supplementary material.

Results

We initiated this study after the identification of a de novo c.1912G>A (p.Gly638Ser) variant in KDM2B (NM_032590.4; Table 1; Supplemental Table 1) through diagnostic trio exome sequencing in the index patient (individual 1), who was diagnosed with speech delay, autism spectrum disorder (ASD), and a congenital heart defect (CHD) (Table 2; Supplemental Table 2). The identified variant was absent from the Genome Aggregation Database (gnomAD),31 predicted damaging by multiple algorithms (Supplemental Table 1), and affects a well-conserved residue (Supplemental Figure 1A) located within the CxxC domain (Figure 1A and B). KDM2B presented as an outstanding candidate disease gene because the gene is intolerant for both putative loss-of-function (LoF) (observed/expected = 0.09 [0.05–0.18]) and missense (z-score = 3.44) variants in the general population.31 In addition, several animal models presented with severe congenital defects.12,32–35 We therefore aimed to study additional individuals with heterozygous KDM2B variants and formed this cohort after online matchmaking using the GeneMatcher platform,25 literature search, personal communication, and in-house database searches. This study was approved by the medical ethical committee installed by the University Medical Centre Utrecht (TCBIO 20/714, March 18, 2021).

Table 1.

Overview of KDM2B variants in the cohort

| Individual | Variant (NM_032590.4) |

Inheritance | gnomAD | In Silico Prediction | EpiSign | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathogenic variants | ||||||

| 1 | c.1912G>A | p.(Gly638Ser) | De novo | − | 4/4 | Y |

| 3.1, 3.2 | c.3370C>T | p.(Arg1124*) | Paternal | − | LoF | Y; Y |

| 4.1, 4.2, 4.3 | c.946G>A | p.(Val316Ile) | Paternal | 1× | 4/4 | Y; U; Y |

| 6 | c.499C>T | p.(Arg167Trp) | De novo | − | 4/4 | Y |

| 7 | c.1894G>T | p.(Asp632Tyr) | De novo | − | 4/4 | Y |

| 8 | c.1880G>A | p.(Cys627Tyr) | De novo | − | 4/4 | NA |

| 10 | c.457delA | p.(Met153Cysfs*24) | De novo | − | LoF | Y |

| 11 | c.3005_3023del19 | p.(Asn1002Serfs*35) | De novo | − | LoF | Y |

| 18, 31 | c.1847G>A | p.(Cys616Tyr) | De novo | − | 4/4 | Y; NA |

| 20 | c.1913G>A | p.(Gly638Asp) | De novo | − | 4/4 | NA |

| 22 | c.1846T>C | p.(Cys616Arg) | De novo | − | 4/4 | Y |

| 23 | c.1889G>C | p.(Cys630Ser) | De novo | − | 4/4 | Y |

| 25.1, 25.2 | 12q24.31 deletion | Paternal | NA | LoF | Y; NA | |

| 29 | 12q24.31 deletion | De novo | NA | LoF | Y | |

| 30 | 12q24.31 deletion | De novo | NA | LoF | Y | |

| Likely pathogenic variants | ||||||

| 13 | c.1903_1905delAAG | p.(K635del) | De novo | − | NA | NA |

| Variants of uncertain significance | ||||||

| 17 | c.1627G>A | p.(Ala543Thr) | De novo | 2× | 4/4 | NA |

| 2 | c.2297G>A | p.(Arg766Gln) | De novo | 2×, 7alt | 3/4 | N |

| 5.1, 5.2 | c.1954A>G | p.(Ile652Val) | Maternal | 2× | 3/4 | N; U |

| 14 | c.3637C>T | p.(Arg1213Trp) | De novo | 5alt | 4/4 | N |

| 19 | c.777+5G>A | Splice site | De novo | − | 3/3 reduced | N |

International collaborations resulted in a cohort of 27 individuals representing 21 variants in KDM2B. Table 1 indicates genetic details of each variant, appearance of the variant in the gnomAD (or alternative variants affecting the same residu), summary of in silico prediction results, and inclusion in the KDM2B episignature cohort. Additional and supporting information per variant can be found in Supplemental Table 1. “×” indicates times, “−” indicates absence.

alt, alternative; gnomAD, Genome Aggregation Database; LoF, loss-of-function; N, no/negative; NA, not applicable/not assessed; U, uncertain; Y, yes/positive.

Table 2.

An overview of the phenotypes associated with KDM2B variants

| No. | Sex, Age, y | Variant (NM_032590.4) | Inheritance | ID/DD | Behavior/Psychiatry | Hypotonia | Microcephaly (OFC <−2 SD) |

Cardiac Anomalies | Kidney Anomalies | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pathogenic variants | ||||||||||

| 1 | M, 7 | c.1912G>A, p.(Gly638Ser) | De novo | Speechdelay, SON-IQ 86 | Autism | − | − | VSD, ASD, fetal atrial flutter | − | Familial polydactyly |

| 3.1 | F, 7 | c.3370C>T, p.(Arg1124*) | Paternal | Severe ID | Hyperactivity | + | − | VSD, DORV | NA | Phelan-McDermid syndrome, 22q13 deletion |

| 3.2 | M, 42 | c.3370C>T, p.(Arg1124*) | Unknown | Learning difficulties | ADD | NA | − | − | NA | COPD |

| 4.1 | M, 15 | c.946G>A, p.(Val316Ile) | Paternal | Mild | Autism, ADHD, tantrums | NA | − | NA | NA | Epilepsy |

| 4.2 | M, 65 | c.946G>A, p.(Val316Ile) | Unknown | Learning difficulties, mild ID | NA | NA | − | NA | NA | Decreased renal function, osteoporosis (adult age) |

| 4.3 | F, 21 | c.946G>A, p.(Val316Ile) | Paternal | Moderate | Autism, tantrums, anxiety | NA | − | NA | NA | |

| 6 | M, 9 | c.499C>T, p.(Arg167Trp) | De novo | Speech delay, nonverbal IQ 97 | ADHD | − | − | − | − | Congenital ptosis, cryptorchidism |

| 7 | M, 4 | c.1894G>T, p.(Asp632Tyr) | De novo | Learning difficulties | Autism, ADHD, impulsiveness | − | − | PVS, ASD | − | Hypertonia, progressive contractures, inguinal hernia |

| 8 | F, 6 | c.1880G>A, p.(Cys627Tyr) | De novo | Mild speech delay | − | − | − | ASD, MR, PDA, PVS | Single kidney | Short stature |

| 10 | M, 10 | c.457del, p.Met153Cysfs*24 | De novo | Mild ID, IQ 66 | − | − | − | Atrial septal aneurysm, MR | − | SHOC2-related Noonan syndrome |

| 11 | F, 5 | c.3005_3023del19, p.(Asn1002Sfs35) | De novo | Global DD, moderate ID | Autism, hyperactivity | + | − | − | NA | Epilepsy, MRI abnormalities (MCD) |

| 18 | M, 5 | c.1847G>A, p.(Cys616Tyr) | De novo | Moderate global DD | − | − | + | − | Single kidney | Coloboma, hypertrichosis, failure to thrive |

| 20 | F, 14 | c.1913G>A, p.(Gly638Asp) | De novo | Speech delay, learning difficulties | Mild autistic features | NA | − | Mild mitral insufficiency | − | Short stature, R oculomotor defect enophtalmus |

| 22 | M, 16 mo | c.1846T>C, p.(Cys616Arg) | De novo | Global DD, speech delay | − | Upper limbs | − | PFO | Single kidney | Brain MRI abnormalities, unilateral anophthalmia, bilateral SNHL, facial asymmetry |

| 23 | F, 3 | c.1889G>C, p.(Cys630Ser) | De novo | Severe DD, no speech | − | + | NA | ASD | Single kidney, right VUR | Short stature, poor weight gain, squint, congenital obstructio ductus nasolacrimalis |

| 25.1 | F, 12 | 12q24.31 deletion (including KDM2B and HNF1A) | Paternal | Severe, no speech, cannot walk | Not specified | + | + | NA | Normal renal function | Epilepsy, hip dysplasia (Choueryet al,19 Krzyzewska et al20) |

| 25.2 | M, adult | 12q24.31 deletion (including KDM2B and HNF1A) | Unknown | Normal | − | − | − | − | − | Insulin-dependent diabetes at 14 y (Chouery et al,19 Krzyzewska et al20) |

| 29 | F, 12 | 12q24.31deletion (including KDM2B and SETD1B) | De novo | + | Autism, ADHD | − | − | NA | NA | Preauricular tags, oligodontia, umbilical hernia (Krzyzewska et al20) |

| 30 | M, 9 | 12q24.31 deletion (including KDM2B and SETD1B) | De novo | + | Probable autism | + | OFC at fourth percentile | NA | NA | Epilepsy (Krzyzewskaet al,20 patient 10; Labonne et al21) |

| 31 | M, 5 | c.1847G>A, p.(Cys616Tyr) | De novo | Speech delay, mild-moderate ID | Stereotypies | − | + | ASD | − | Cryptorchidism, talus pes, kyphosis, congenital obstruction of ductus nasolacrimalis |

| Likely pathogenic variant (sample not available for methylation analysis) | ||||||||||

| 13 | F, 4 | c.1903_1905delAAG, p.(Lys635del) | De novo | Moderate speech delay, mild ID | − | + | + | ASD (2 times), PVS, PDA, PFO | − | Feeding difficulties at birth |

| VUS (sample not available for methylation analysis) | ||||||||||

| 17 | F, 7 | c.1627G>A, p.(Ala543Thr) | De novo | + | Autism | + | − | PFO | NA | History of failure to thrive until age 2 y, epilepsy, later obesity, MRI abnormalities |

| VUS(variants not showing KDM2B specific episignature) | ||||||||||

| 2 | F, 1.8 | c.2297G>A, p.(Arg766Gln) | De novo | − | − | − | NA | − | NA | CL/P, preaxial polydactyly, finger contractures, thumb hypoplasia |

| 5.1 | M, 28 | c.1954A>G, p.(Ile652Val) | Maternal | Mild-moderate | Autism | NA | − | NA | NA | Scoliosis, hearing loss due to cholesteatoma |

| 5.2 | F, 58 | c.1954A>G, p.(Ile652Val) | Unknown | − | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Dyslexia |

| 14 | M, 12 | c.3637C>T, p.(Arg1213Trp) | De novo | Global DD, limited speech, mild ID (IQ 64) | Hyperactivity, aggressive behavior | + | − | − | − | Macrocephaly, epilepsy, brain MRI abnormalities, hand/finger abnormalities |

| 19 | F, 1 | c.777+5G>A | De novo | Severe DD, no speech | NA | + | + | ASD | Thrombotic angiopathy | Neonatal seizures, SNHL, abnormal renal vasculature |

Table 2 summarizes the clinical features of individuals with KDM2B variants. More extensive data are presented in Supplemental Table 2 and the clinical summaries. “+” indicates presence of feature and “−” indicates absence of feature.

ADD, attention deficit disorder; ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; ASD, atrial septal defect; CL/P, cleft lip/palate; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; DD, developmental delay; DORV, double outlet right ventricle; F, female; ID, intellectual disability; M, male; MCD, malformation of cortical development; MR, mitral regurgitation; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NA, not assessed; PDA, persistent ductus arteriosus; PFO, persistent foramen ovale; PVS, pulmonary valve stenosis; R, right; SNHL, sensorineural hearing loss; SON-IQ, Snijders-Oomen non-verbal intelligence quotient; VSD, ventricular septal defect; VUS, variant of uncertain significance; VUR, vesicoureteral reflux.

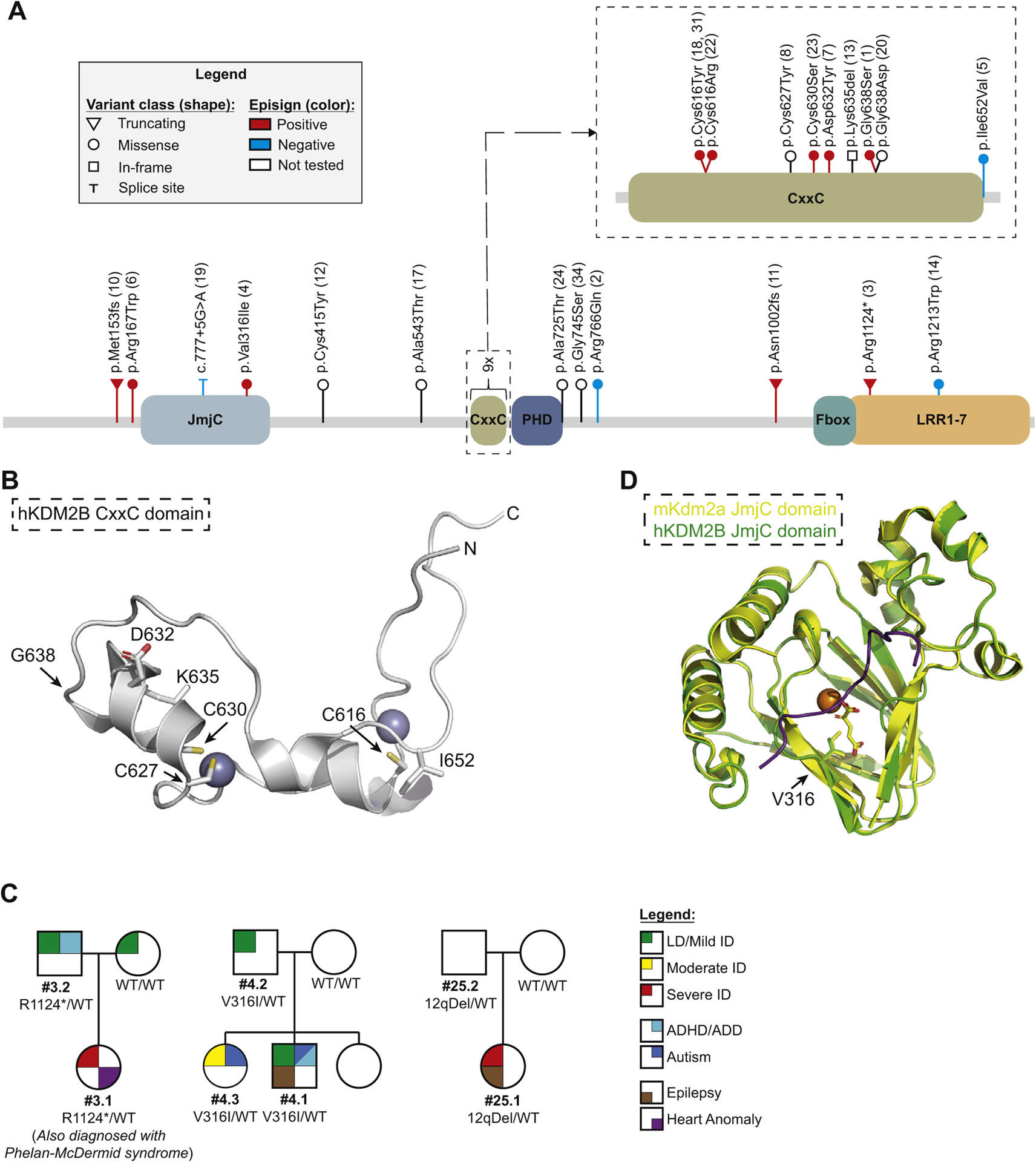

Figure 1. A cohort of individuals with heterozygous KDM2B variants.

A. Schematic representation of the KDM2B gene, its known domains, and the variants included in this study. Lollipops representing individual variants indicate location, classification of (predicted) effect on the transcript and/or protein (shape), and the classification based on the first analysis of the methylation arrays (color; Supplemental Figure 2). Larger deletions (ie, cases 25.1, 25.2, 29, and 30) are not shown. B. Projection of CxxC domain missense variants on the known crystal structure. Purple spheres represent Zn2+ ions. Side chains of relevant residues are included. C. Pedigrees depicting all cases of inherited pathogenic variants for which the pedigrees have not been published before (families 3, 4, and 25). All remaining pedigrees can be found in Supplemental Figure 1. D. Projection of the p.Val316Ile (family 4) variant on the structure of the mouse Kdm2a JmjC structure (yellow). Predicted human KDM2B JmjC structure as determined by AlphaFold is shown in green. Orange sphere indicates Fe2+ ion and the α-ketoglutarate cofactor is shown as yellow sticks. Purple line indicates target peptide (histon 3). ADD, attention deficit disorder; ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; ID, intellectual disability; LD, learning difficulties; WT, wild type.

We collected data of a total of 27 individuals from 22 families representing 21 different heterozygous variants in KDM2B (Figure 1; Tables 1 and 2; Supplemental Figure 1; Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). Our cohort encompassed 3 putative LoF variants, 13 missense variants, 1 in-frame deletion, and three 12q24.31 microdeletions. A total of 17 variants were confirmed to be de novo. Of note, one of these variants was identified twice and thus occurred de novo at 2 independent occasions (c.1847G>A; individuals 18 and 31). Four variants were inherited (families 3, 4, 5, and 25; Figure 1C and Supplemental Figure 1B). Four individuals with microdeletions have been reported previously: family 25 with an inherited 12q deletion19 and individuals 29 and 30 with a de novo 12q deletion including KDM2B and SETD1B.20

We observed a remarkable clustering of variants (8 missense and 1 in-frame deletion) in the DNA-binding CxxC domain (Figure 1A and B), of which, 7 missense variants were predicted damaging by all algorithms. The only exception was p.Ile652Val, which was the only inherited variant and is reported twice in gnomAD. We performed structural modeling, which showed that this residue is located toward the surface and the substitution is not expected to influence local structure. All other variants affecting the CxxC domain however are expected to affect protein function by either interfering with the binding with Zn2+ ions (p.Cys616, p.Cys627, and p.Cys630) or affecting the local structure (p.Gly638, p.Asp632, and p.Lys635; Figure 1B). The p.Val316Ile variant is likely located at the active site of the JmjC domain and therefore is expected to affect its catalytic function (Figure 1D).

Because of the role of KDM2B in the epigenetic machinery, we hypothesized that impaired KDM2B function leads to genome-wide changes in DNA methylation, an effect that has been observed in >50 other genetic syndromes.2,3,36 These methylation changes present as disease specific episignatures, which are detectable in peripheral blood. As such, episignatures provide not only fundamental insights into the molecular consequences of genetic variants but also easily accessible diagnostic tools to identify syndromes or reclassify VUS.3

We generated genome-wide methylation array data for 21 individuals (Table 1; Supplemental Table 1) according to the previously established protocols.37 We excluded 2 samples because of technical errors (samples 2 and 4.2; Supplemental Figure 2D). Another 3 samples failed to group with case samples after cross validations and were excluded for the establishment of the episignature (samples 5.1, 14, and 19; Supplemental Figure 2B, D, and E). These 3 variants were previously classified as VUS on the basis of their inheritance and/or presence in gnomAD (Table 1; Supplemental Table 1).

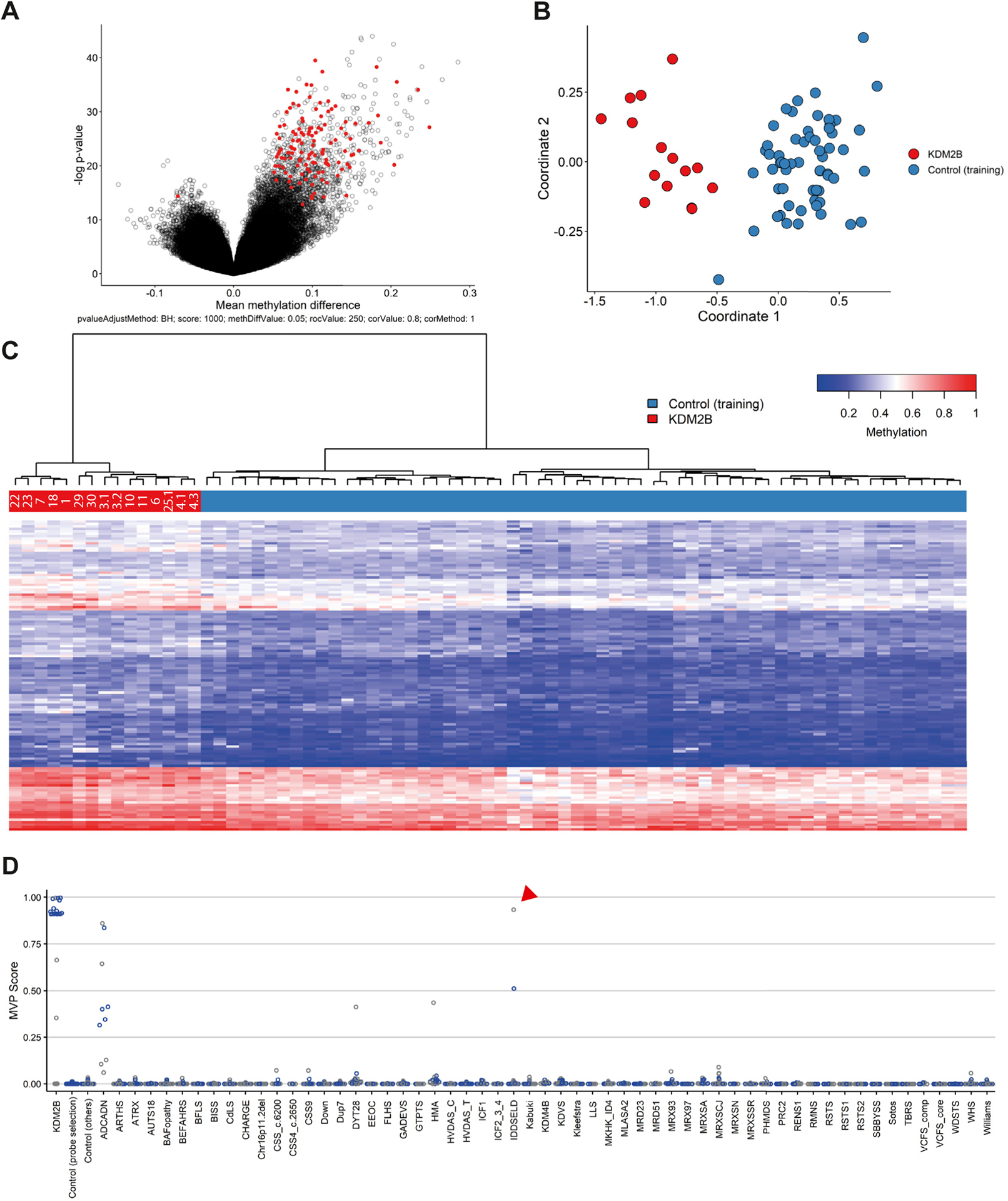

The remaining 15 samples, representing 13 variants, were used to establish a KDM2B episignature (Figure 2). Methylation patterns were assessed for sample quality, degree of methylation change, and statistical robustness of observed changes at each probe, allowing for effective modeling of the methylation differences observed between case samples and matched controls (see Materials and Methods). Comparisons were performed against age- and sex-matched controls, leading to the identification of 156 statistically differentially methylated probes (Figure 2A). Hierarchical clustering based on this probe set showed distinct clustering of case samples away from controls, with all samples presenting a more similar methylation profile to one another than the matched controls (Figure 2B and C). Cross validation assays, based on the removal of each single sample from the probe selection training process, confirmed that the probe set was able to effectively identify KDM2B variants because all case samples remained grouped together in each iteration (Supplemental Figure 3B). In conclusion, we have established an episignature that is able to discriminate KDM2B variants from controls and classified these 13 variants as pathogenic (Table 1). Interestingly, the KDM2B associated episignature mainly consisted of hypermethylated probes (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. A KDM2B specific episignature.

After initial analysis (Supplemental Figure 2), 15 samples identified as outliers in the initial analysis were included for the training of a KDM2B specific episignature. A. Volcano plot indicating probes (red) included in the KDM2B episignature. B. Multidimensional scaling plot for selected probes, representing the pairwise distance across samples (red) and controls (blue) based on the top 2 dimensions. C. Heatmap of selected probes and unsupervised hierarchal clustering results indicating the episignature’s ability to differentiate KDM2B variants (red) from controls (blue). D. Support vector machine (SVM) classifier indicating specificity of the KDM2B episignature. Graph shows summary of 4-fold validation using all 15 case samples, using 75% of unaffected controls and other episignatures for training (blue) and the other 25% for testing (gray). Y-axis: MVP scores as determined by SVM. X-axis: different groups of samples, controls, and other known episignatures. Red arrowhead indicates the intellectual developmental disorder with seizures and language delay sample referred to in the text. MVP, methylation variant pathogenicity.

We next tested the sensitivity and specificity of the episignature using a support vector machine. For each sample, we determined a methylation variant pathogenicity (MVP) score between 0 and 1 on the basis of matching the KDM2B episignature. All KDM2B samples included in the training set received scores of >0.8, whereas control samples remained near 0, indicating high sensitivity for the detection of the KDM2B episignature (Supplemental Figure 3C). Specificity was tested using a similar classifier that was instead trained against a large number of samples with confirmed diagnoses of non-KDM2B related disorders from our Episign knowledge database. In total, 75% of both case and control samples were used for training the classifier with the remaining 25% reserved for testing (Figure 2D). Case samples again scored high (>0.85) whereas the remainder of samples scored low (<0.5), with few exceptions. The most notable exceptions were cerebellar ataxia, deafness, and narcolepsy (ADCADN; OMIM 604121), Hunter-McAlpine syndrome (HMA; OMIM 601379), and dystonia 28, childhood-onset (DYT28; OMIM 617284). One other sample among the control samples did score remarkably high for the KDM2B signature (Figure 2D, red arrow head). This patient was previously diagnosed with intellectual developmental disorder with seizures and language delay (IDDSELD; OMIM 619000), a disorder caused by SETD1B variants. Upon closer investigation, we identified this sample to originate from a case with a 12q24.31 microdeletion including SETD1B but not KDM2B.20,38 We hypothesize that the deletion might have affected KDM2B regulatory regions. For reference, we have included the clinical description of this individual (individual 33, Supplemental Table 2).

A total of 4 KDM2B variants within our cohort tested negative for the signature. Among the negative samples are 3 missense variants for which pathogenicity was doubtful based on the a priori predictions and/or gnomAD data. The other negative sample in our cohort was that of the only splice-site variant, indicating that the predicted splice effects do not occur or at least not to a level that interferes with gene functionality. We classified these 4 variants as VUS because a negative episignature result does not suffice to infer an absence of functional effects (Table 1).

Of note, 2 individuals in our cohort with microdeletions encompassing both KDM2B and SETD1B (individuals 29 and 30) were previously shown to have the SETD1B-associated episignature.20 In the same samples, we have now additionally identified the KDM2B episignature. Another sample showing 2 distinct episignatures was sample 3.1, which was from a girl who was previously diagnosed with Phelan-McDermid syndrome (OMIM 606232) due to a 22q13 deletion. These results indicate that multiple episignatures can coexist in a single individual, and the method is able to correctly identify 2 syndromes independently.

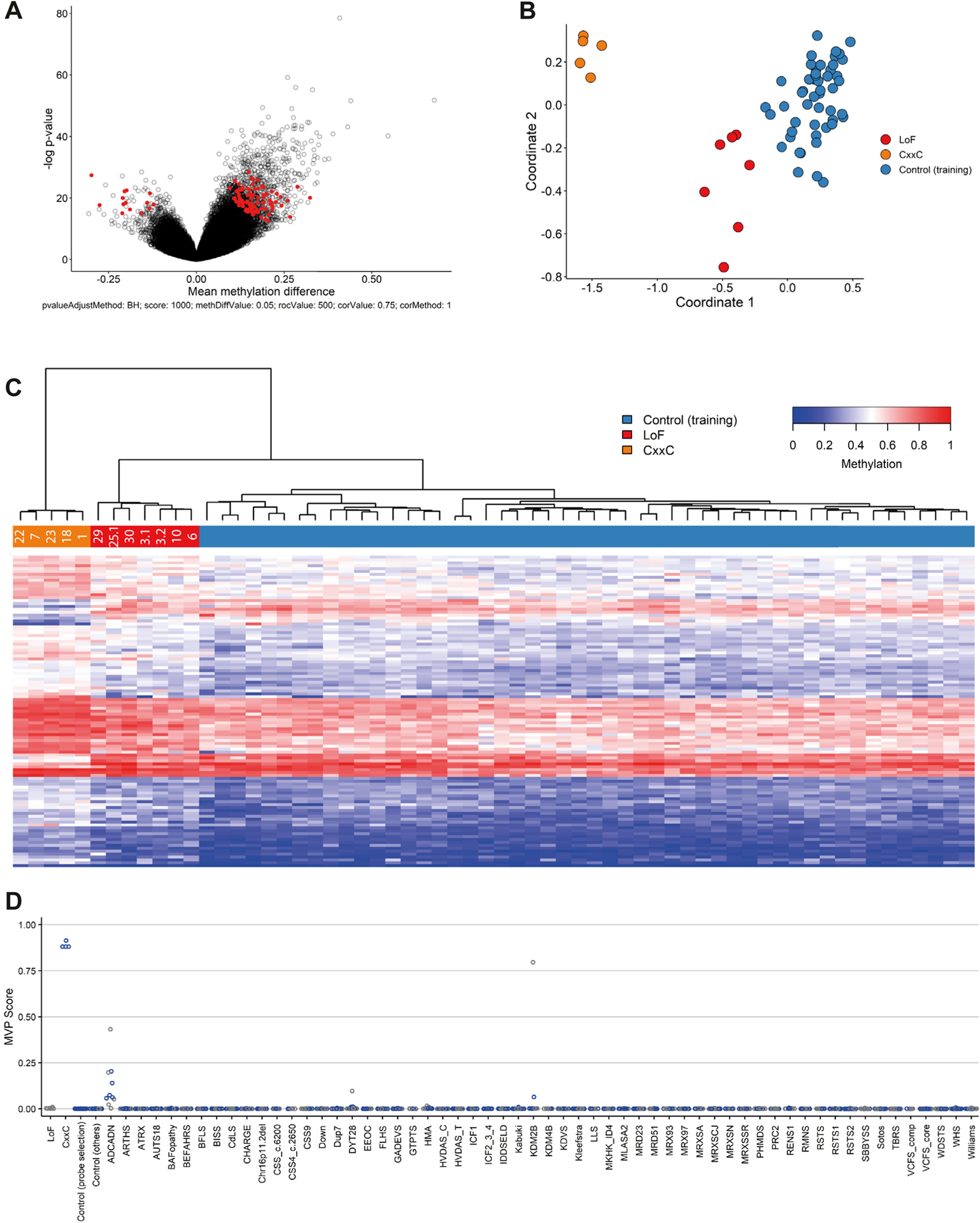

The clustering of missense variants in the CxxC domain suggests a distinct effect on KDM2B function over LoF variants. We therefore trained a separate classifier using 5 CxxC domain missense samples (Figure 3; Supplemental Table 1). Interestingly, the resulting probeset not only correctly differentiated all KDM2B variants (ie, including the LoF variants) from controls but also was able to distinguish CxxC and LoF variants (Figure 3B and C). Of note, 106 hypermethylated probes among the 107 significant probes selected for the CxxC-trained episignature present with an on average increased methylation level, even exceeding that of the hypermethylated probes of the pan-KDM2B probeset (mean methylation difference of all hypermethylated probes: 16.56% ± 4.21% vs 10.38% ± 3.68%; Figure 2A and Figure 3A). Importantly, a probeset trained using LoF samples was able to discriminate CxxC from LoF variants as well (Supplemental Figure 4). In conclusion, CxxC missense variants cause a distinct episignature that is associated with increased hypermethylation levels, suggesting an additional effect on KDM2B functioning of these variants.

Figure 3. A CxxC-variant specific episignature.

All samples representing a CxxC-domain variant and included in the KDM2B episignature training set were used to train a CxxC-variant specific episignature. A. Volcano plot indicating all probes (red) included in the CxxC episignature. B. Multidimensional scaling plot for selected probes representing the pairwise distance across CxxC variants (orange), LoF variants (red), and controls (blue) based on the top 2 dimensions. C. Heatmap of selected probes and unsupervised hierarchal clustering results indicating the episignature’s ability to differentiate KDM2B variants (red and orange) from controls (blue) and to differentiate CxxC variants (orange) from LoF variants (red). D. Support vector machine classifier indicating specificity of the CxxC episignature. Graph is same as in Figure 2D. MVP, methylation variant pathogenicity.

Next, we set out to reclassify 4 variants that were not tested for the episignature on the basis of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics/Association for Molecular Pathology guidelines30 (Supplemental Table 1). Importantly, we considered the CxxC domain as an established hotspot for pathogenic variation in KDM2B (criterium PM1). We reclassified 2 variants as pathogenic, 1 variant as likely pathogenic, and 1 as VUS (Table 1; Supplemental Table 1). In summary, we classified 15 variants as pathogenic, 1 variant as likely pathogenic, and 6 variants remained as VUS (Table 1; Supplemental Table 1, Supplemental Figure 5).

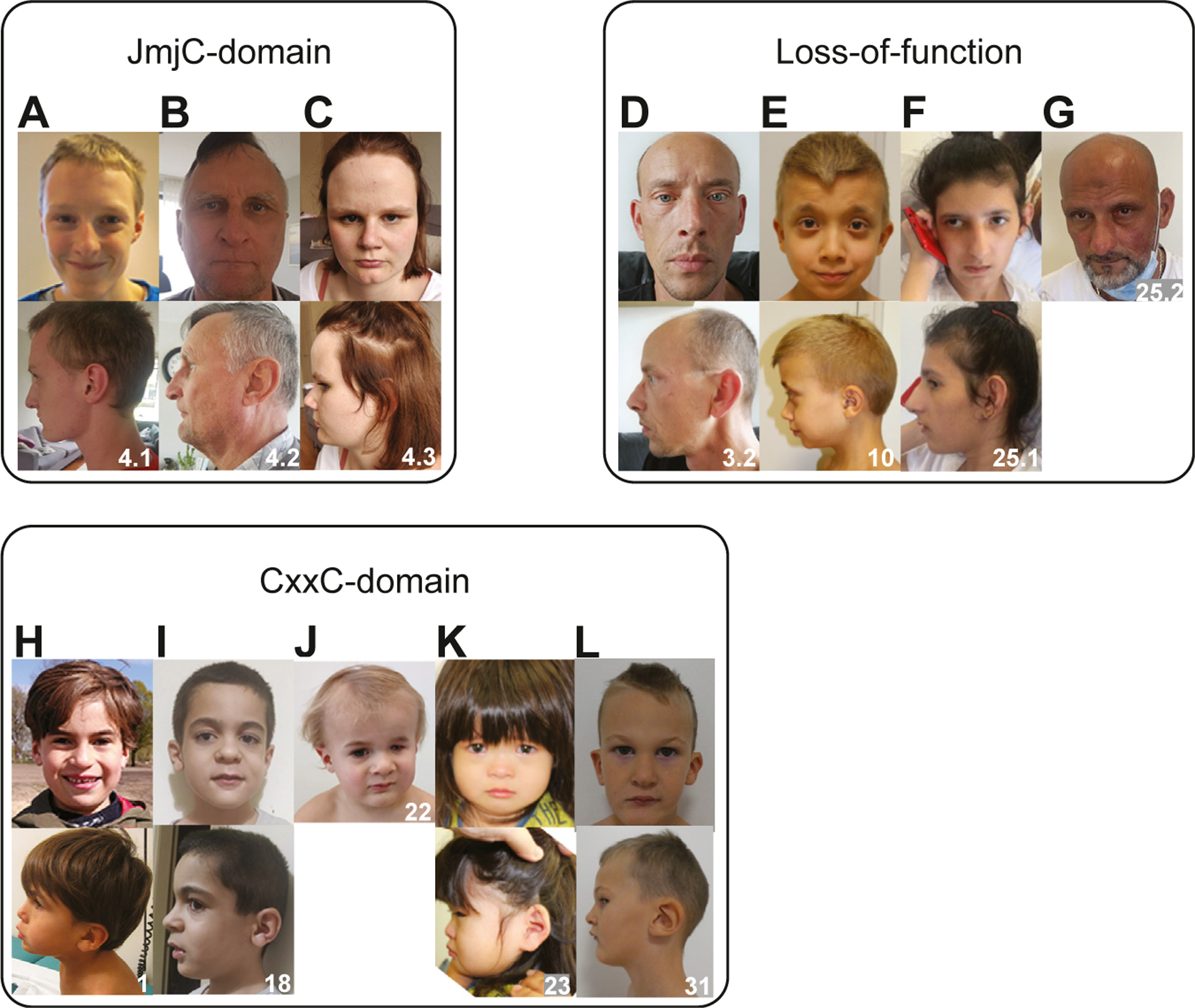

Clinical data of all individuals are systematically presented in Table 2. A more detailed description for each individual and their clinical histories are provided as supplemental material. Data form previously described individuals are included in Supplemental Table 2 as well. Of the 21 individuals with a—likely—pathogenic variant, 4 had a microdeletion and 2 had an additional genetic diagnosis. The remaining 15 individuals all presented with speech delay, developmental delay (DD), learning difficulties, and/or intellectual disability (ID). Behavioral concerns such as ASD and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder were common (9/15). Growth parameters were within the normal range for most patients. We observe several congenital defects, including heart defects (7/15), unilateral kidney agenesis (4/15), and ophthalmological anomalies (6/14). Two patients had cryptorchidism and 2 had epilepsy. We collected facial photographs of 12 (12/21) individuals (Figure 4). Facial features noted in several individuals with CxxC-domain variants were a broad nasal tip, large ear lobes, and exaggerated Cupid’s bow. Interestingly, in the individuals with LoF variants the nose was often more prominent, with a narrow nasal ridge and malar flattening, with the exception of individual 10 who also had a diagnosis of Noonan syndrome. Despite these subtle features, no consistent facial gestalt could be identified. In summary, we have delineated a novel syndrome that is caused by heterozygous KDM2B variants and characterized clinically by DD/ID; behavioral challenges including autism and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; congenital anomalies mainly of the heart, urogenital system, and eyes; and variable facial dysmorphism.

Figure 4. Facial characteristics of individuals with KDM2B pathogenic variants.

A-C. Individuals of family 4 with the p.Val316Ile variant located in the JmjC-domain. D-G. Individuals with loss-of-function variants. Individual 10 (E) was also affected with Noonan syndrome. H-L. Individuals with missense variants in the CxxC domain.

Because our methylation analysis revealed differences between CxxC and LoF variants, we studied potential genotype–phenotype relationships for these subgroups. Unilateral kidney agenesis and eye anomalies were only reported in CxxC cases. In addition, CHDs were present in 6 individuals with a CxxC variant (6/9) and only in 2 individuals with a LoF variant (2/8). Of note, this involved 1 individual with Noonan syndrome and 1 with Phelan-McDermid syndrome, and both syndromes are associated with CHD. We thus note that congenital organ anomalies might be overrepresented in individuals with CxxC variants; however, the current limited number of available cases precludes to draw any conclusions. Epilepsy did not occur in association with the CxxC-domain variants but occurred in 1 patient with a JmjC-domain variant, 1 patient with a frame-shift variant, and 2 patients with a 12q24.31 microdeletion.

Discussion

We describe a novel NDD caused by heterozygous pathogenic variants in KDM2B and present an episignature associated with the disorder. We identify the CxxC domain as a mutational hotspot, and variants affecting this domain are associated with a specific episignature. In line with other MDEMs, individuals with pathogenic variants in KDM2B present with variable phenotypic expression, including DD/ID, congenital organ anomalies, and/or facial dysmorphisms. Most pathogenic variants are of de novo origin, however, in 3 families, the variant was found to be inherited. Interestingly, individual 25.2 is an adult male with a 12q24.31 microdeletion, who did not seem to be clinically affected even though the KDM2B episignature was present in his sample (data not shown). These observations might reflect the variable expression of this disorder; although, we also consider alternative hypotheses. Because we were unable to test the grandparents, we cannot exclude germline mosaicism. Alternatively, all inherited variants originated from the father, possibly indicating that males are less severely affected. In mice, Kdm2b has been shown to be involved in X-chromosome silencing,39 and as such, a different clinical expression in males vs females seems plausible. Larger cohorts are needed to fully encompass the phenotypes and penetrance associated with the disorder and refine its (domain) specific episignature(s).

For the KDM2B episignature, we noticed elevated MVP scores for 3 other disorders (Figure 2D). The first was ADCADN, caused by pathogenic variants in DNMT1, a methyltransferase known as the central player in the maintenance of CpG methylation.2,40 Interestingly, DNMT1 has been suggested to regulate H3K4 methylation, providing a direct mechanistic link with KDM2B.41 The second was HMA, a syndrome associated with duplication of 5q35.42,43 This region includes NSD1, which encodes a lysine methyl transferase known to methylate H3K36,44 providing a direct functional link with KDM2B as well. Finally, DYT28 is associated with KMT2B,45 encoding another methyltransferase reported to methylate H3K4.46 Phenotypically, the KDM2B related disorder shares features with HMA, eg, mild to moderate developmental delay, CHDs, and dysmorphism, but presents differently from ADCADN and DYT28. Interestingly, the KDM2B related disorder, ADCADN, HMA, and DYT28 episignatures are all characterized by hypermethylation.2,47,48 The elevated MVP scores might therefore reflect a set of loci sensitive to hypermethylation, irrespective of the underlying mechanisms. Future studies will have to determine whether and how the KDM2B disorder, ADCADN, DYT28, and HMA share a common etiology.

Hypermethylation has previously been linked to KDM2B because loss of Kdm2b in mouse embryonic stem cells leads to genome-wide hypermethylation of promotors associated with polycomb repressive complexes, implying that Kdm2b protects against de novo DNA methylation during mouse development.12 Interestingly, re-expression of a short Kdm2b isoform, lacking the catalytic JmjC domain, resets the methylation of CpG-islands to baseline levels and rescues embryonic lethality.12 This short isoform is highly expressed in mouse embryonic stem cells,34 suggesting important functions of Kdm2b besides lysine demethylation activity.

The clustering of variants in the CxxC domain, an excess of congenital defects, and a distinct episignature with even further elevated levels of hypermethylation associated with CxxC-domain variants are suggestive of a—partial—dominant-negative effect of these variants. Interestingly, the CxxC domain has been specifically implicated in the developmental functions of KDM2B because CxxC-domain mutants fail to rescue cellular differentiation induced by Kdm2b depletion in mouse embryonic stem cells,10 and specific deletion of the CxxC domain induces developmental defects in the heterozygous state whereas heterozygous knock-outs appear healthy.32,33 Recently, a heterozygous conditional mutant mouse with loss of the CxxC domain in the developing brain was shown to exhibit impaired memory and ASD-like behaviors.49 These animal models therefore share many features with the human syndrome and also point to the CxxC domain harboring important developmental functions. Further studies are necessary to fully understand the broad effect of KDM2B on human development.

The KDM2B-associated NDD represents a novel addition to the emerging group of MDEMs.1 Its associated episignature can aid in reclassification of VUS and the detection of missed variants during routine diagnostic testing, eg, due to variants outside coding regions or due to inherited variants missed by standard trio filtering.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the involved patients and their families for contributing to this study. In addition, they thank Yohei Misumi and Koen van Gassen for their contribution to this study and the genome diagnostic laboratory at the UMC Utrecht for facilitating cohort collection and variant interpretation. This work was funded by the government of Canada through GenomeCanada and the Ontario Genomics Institute (OGI-188). N.M. is supported by Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development (AMED) (JP20ek0109486, JP21ek0109549, JP21cm0106503, and JP21ek0109493 to N. Matsumoto). B.P. is supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) through grant PO2366/2-1. C.A.W. is supported by a grant from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) (R01NS035129) and is an investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute. M.T. is supported by the Italian Ministry of Health (5x1000_2019, RCR-2021-23671215, and RCR-2022-23682289 to M.T.). M.E.S.L. is supported by an Investigator Grant Award from B.C. Children’s Hospital Research Institute.

Footnotes

Ethics Declaration

This study was approved by the medical ethical committee installed by the University Medical Centre Utrecht (TCBIO 20/714, March 18, 2021). All individuals were included after informed consent forms, stating that they agree to participate in research efforts and publication of their clinical and genetic data and photos, for relevant cases, were signed and received by the respective institutions. Patient privacy was respected during the exchange of data among researchers and/or clinicians.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Additional Information

The online version of this article (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gim.2022.09.006) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available owing to privacy or ethical restrictions.

References

- 1.Fahrner JA, Bjornsson HT. Mendelian disorders of the epigenetic machinery: postnatal malleability and therapeutic prospects. Hum Mol Genet. 2019;28(R2):R254–R264. Published correction appears in Hum Mol Genet. 2020;29(5):876. 10.1093/hmg/ddz174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aref-Eshghi E, Kerkhof J, Pedro VP, et al. Evaluation of DNA methylation episignatures for diagnosis and phenotype correlations in 42 Mendelian neurodevelopmental disorders. Am J Hum Genet. 2020;106(3):356–370. Published correction appearance in Am J Hum Genet. 2021;108(6):1161–1163. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2020.01.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sadikovic B, Levy MA, Kerkhof J, et al. Clinical epigenomics: genome-wide DNA methylation analysis for the diagnosis of Mendelian disorders. Genet Med. 2021;23(6):1065–1074. Published correction appears in Genet Med. 2021;23(11):2228. 10.1038/s41436-020-01096-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsukada Y, Fang J, Erdjument-Bromage H, et al. Histone demethylation by a family of JmjC domain-containing proteins. Nature. 2006;439(7078):811–816. 10.1038/nature04433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.He J, Nguyen AT, Zhang Y. KDM2b/JHDM1b, an H3K36me2-specific demethylase, is required for initiation and maintenance of acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2011;117(14):3869–3880. 10.1182/blood-2010-10-312736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kang JY, Kim JY, Kim KB, et al. KDM2B is a histone H3K79 demethylase and induces transcriptional repression via sirtuin-1-mediated chromatin silencing. FASEB J. 2018;32(10):5737–5750. 10.1096/fj.201800242R [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Frescas D, Guardavaccaro D, Bassermann F, Koyama-Nasu R, Pagano M. JHDM1B/FBXL10 is a nucleolar protein that represses transcription of ribosomal RNA genes. Nature. 2007;450(7167):309–313. 10.1038/nature06255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janzer A, Stamm K, Becker A, Zimmer A, Buettner R, Kirfel J. The H3K4me3 histone demethylase Fbxl10 is a regulator of chemokine expression, cellular morphology, and the metabolome of fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2012;287(37):30984–30992. 10.1074/jbc.M112.341040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Klose RJ, Kallin EM, Zhang Y. JmjC-domain-containing proteins and histone demethylation. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7(9):715–727. 10.1038/nrg1945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.He J, Shen L, Wan M, Taranova O, Wu H, Zhang Y. Kdm2b maintains murine embryonic stem cell status by recruiting PRC1 complex to CpG islands of developmental genes. Nat Cell Biol. 2013;15(4):373–384. 10.1038/ncb2702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He J, Kallin EM, Tsukada YI, Zhang Y. The H3K36 demethylase Jhdm1b/Kdm2b regulates cell proliferation and senescence through p15(Ink4b). Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2008;15(11):1169–1175. 10.1038/nsmb.1499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Boulard M, Edwards JR, Bestor TH. FBXL10 protects polycomb-bound genes from hypermethylation. Nat Genet. 2015;47(5):479–485. 10.1038/ng.3272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deiktakis EE, Abrams M, Tsapara A, et al. Identification of structural elements of the lysine specific demethylase 2B CxxC domain associated with replicative senescence bypass in primary mouse cells. Protein J. 2020;39(3):232–239. 10.1007/s10930-020-09895-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xu C, Liu K, Lei M, et al. DNA sequence recognition of human CXXC domains and their structural determinants. Structure. 2018;26(1):85–95e3. 10.1016/j.str.2017.11.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Farcas AM, Blackledge NP, Sudbery I, et al. KDM2B links the polycomb repressive complex 1 (PRC1) to recognition of CpG islands. eLife. 2012;1:e00205. 10.7554/eLife.00205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu X, Johansen JV, Helin K. Fbxl10/Kdm2b recruits polycomb repressive complex 1 to CpG islands and regulates H2A ubiquitylation. Mol Cell. 2013;49(6):1134–1146. 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jiang Y, Qian X, Shen J, et al. Local generation of fumarate promotes DNA repair through inhibition of histone H3 demethylation. Nat Cell Biol. 2015;17(9):1158–1168. Published correction appears in Nat Cell Biol. 2018;20(10):1226. 10.1038/ncb3209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marcon E, Ni Z, Pu S, et al. Human-chromatin-related protein interactions identify a demethylase complex required for chromosome segregation. Cell Rep. 2014;8(1):297–310. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.05.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chouery E, Choucair N, Abou Ghoch J, El Sabbagh S, Corbani S, Mégarbané A. Report on a patient with a 12q24.31 microdeletion inherited from an insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus father. Mol Syndromol. 2013;4(3):136–142. 10.1159/000346473 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krzyzewska IM, Maas SM, Henneman P, et al. A genome-wide DNA methylation signature for SETD1B-related syndrome. Clin Epigenetics. 2019;11(1):156. 10.1186/s13148-019-0749-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Labonne JDJ, Lee KH, Iwase S, et al. An atypical 12q24.31 microdeletion implicates six genes including a histone demethylase KDM2B and a histone methyltransferase SETD1B in syndromic intellectual disability. Hum Genet. 2016;135(7):757–771. 10.1007/s00439-016-1668-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Girard SL, Gauthier J, Noreau A, et al. Increased exonic de novo mutation rate in individuals with schizophrenia. Nat Genet. 2011;43(9):860–863. 10.1038/ng.886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monies D, Abouelhoda M, AlSayed M, et al. The landscape of genetic diseases in Saudi Arabia based on the first 1000 diagnostic panels and exomes. Hum Genet. 2017;136(8):921–939. 10.1007/s00439-017-1821-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yokotsuka-Ishida S, Nakamura M, Tomiyasu Y, et al. Positional cloning and comprehensive mutation analysis identified a novel KDM2B mutation in a Japanese family with minor malformations, intellectual disability, and schizophrenia. J Hum Genet. 2021;66(6):597–606. 10.1038/s10038-020-00889-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sobreira N, Schiettecatte F, Valle D, Hamosh A. GeneMatcher: a matching tool for connecting investigators with an interest in the same gene. Hum Mutat. 2015;36(10):928–930. 10.1002/humu.22844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwarz JM, Cooper DN, Schuelke M, Seelow D. MutationTaster2: mutation prediction for the deep-sequencing age. Nat Methods. 2014;11(4):361–362. 10.1038/nmeth.2890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wiel L, Baakman C, Gilissen D, Veltman JA, Vriend G, Gilissen C. MetaDome: pathogenicity analysis of genetic variants through aggregation of homologous human protein domains. Hum Mutat. 2019;40(8):1030–1038. 10.1002/humu.23798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Adzhubei IA, Schmidt S, Peshkin L, et al. A method and server for predicting damaging missense mutations. Nat Methods. 2010;7(4):248–249. 10.1038/nmeth0410-248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vaser R, Adusumalli S, Leng SN, Sikic M, Ng PC. SIFT missense predictions for genomes. Nat Protoc. 2016;11(1):1–9. 10.1038/nprot.2015.123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17(5):405–424. 10.1038/gim.2015.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Karczewski KJ, Francioli LC, Tiao G, et al. The mutational constraint spectrum quantified from variation in 141,456 humans. Nature. 2020;581(7809):434–443. Published correction appears in Nature. 2021;590(7846):E53. Published correction appears in Nature. 2021;597(7874):E3-E4. 10.1038/s41586-020-2308-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andricovich J, Kai Y, Peng W, Foudi A, Tzatsos A. Histone demethylase KDM2B regulates lineage commitment in normal and malignant hematopoiesis. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(3):905–920. 10.1172/JCI84014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blackledge NP, Farcas AM, Kondo T, et al. Variant PRC1 complex-dependent H2A ubiquitylation drives PRC2 recruitment and polycomb domain formation. Cell. 2014;157(6):1445–1459. 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fukuda T, Tokunaga A, Sakamoto R, Yoshida N. Fbxl10/Kdm2b deficiency accelerates neural progenitor cell death and leads to exencephaly. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2011;46(3):614–624. 10.1016/j.mcn.2011.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Testoni S, Bartolone E, Rossi M, et al. KDM2B is implicated in bovine lethal multi-organic developmental dysplasia. PLoS One. 2012;7(9):e45634. 10.1371/journal.pone.0045634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aref-Eshghi E, Bend EG, Colaiacovo S, et al. Diagnostic utility of genome-wide DNA methylation testing in genetically unsolved individuals with suspected hereditary conditions. Am J Hum Genet. 2019;104(4):685–700. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2019.03.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aref-Eshghi E, Rodenhiser DI, Schenkel LC, et al. Genomic DNA methylation signatures enable concurrent diagnosis and clinical genetic variant classification in neurodevelopmental syndromes. Am J Hum Genet. 2018;102(1):156–174. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2017.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Qiao Y, Tyson C, Hrynchak M, et al. Clinical application of 2.7M Cytogenetics array for CNV detection in subjects with idiopathic autism and/or intellectual disability. Clin Genet. 2013;83(2):145–154. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2012.01860.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Boulard M, Edwards JR, Bestor TH. Abnormal X chromosome inactivation and sex-specific gene dysregulation after ablation of FBXL10. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2016;9:22. 10.1186/s13072-016-0069-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Winkelmann J, Lin L, Schormair B, et al. Mutations in DNMT1 cause autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia, deafness and narcolepsy. Hum Mol Genet. 2012;21(10):2205–2210. 10.1093/hmg/dds035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun L, Huang L, Nguyen P, et al. DNA methyltransferase 1 and 3B activate BAG-1 expression via recruitment of CTCFL/BORIS and modulation of promoter histone methylation. Cancer Res. 2008;68(8):2726–2735. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6654 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hunter AGW, Dupont B, McLaughlin M, et al. The Hunter-McAlpine syndrome results from duplication 5q35-qter. Clin Genet. 2005;67(1):53–60. 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2005.00378.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hunter AG, McAlpine PJ, Rudd NL, Fraser FC. A “new” syndrome of mental retardation with characteristic facies and brachyphalangy. J Med Genet. 1977;14(6):430–437. 10.1136/jmg.14.6.430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rayasam GV, Wendling O, Angrand PO, et al. NSD1 is essential for early post-implantation development and has a catalytically active SET domain. EMBO J. 2003;22(12):3153–3163. 10.1093/emboj/cdg288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zech M, Boesch S, Maier EM, et al. Haploinsufficiency of KMT2B, encoding the lysine-specific histone methyltransferase 2B, results in early-onset generalized dystonia. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;99(6):1377–1387. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2016.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Demers C, Chaturvedi CP, Ranish JA, et al. Activator-mediated recruitment of the MLL2 methyltransferase complex to the beta-globin locus. Mol Cell. 2007;27(4):573–584. 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.06.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ciolfi A, Foroutan A, Capuano A, et al. Childhood-onset dystonia-causing KMT2B variants result in a distinctive genomic hypermethylation profile. Clin Epigenetics. 2021;13(1):157. 10.1186/s13148-021-01145-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kernohan KD, Cigana Schenkel L, Huang L, et al. Identification of a methylation profile for DNMT1-associated autosomal dominant cerebellar ataxia, deafness, and narcolepsy. Clin Epigenetics. 2016;8:91. 10.1186/s13148-016-0254-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gao Y, Duque-Wilckens N, Aljazi MB, et al. Impaired KDM2B-mediated PRC1 recruitment to chromatin causes defective neural stem cell self-renewal and ASD/ID-like behaviors. iScience. 2022;25(2):103742. 10.1016/j.isci.2022.103742 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available owing to privacy or ethical restrictions.