Abstract

The question of “when” to treat speech sounds is often posed in the context of normative data. New normative data suggests that speech sounds such as /ɹ/ and /l/ are acquired earlier than previously thought (McLeod & Crowe, 2018; Crowe & McLeod, 2020). The present study compared treatment of late-acquired sounds between two age groups of English-speaking children: Young children (4–5) and Old children (7–8). Eight monolingual children with speech sound disorder (SSD), participated in the study. Each child received a criterion-based, standardized, two-phase therapy protocol. Treatment efficacy was measured by examining children’s accuracy on real word speech probes. Treatment efficiency was measured by calculating the number of sessions required to meet exit criterion and mean session duration. For treatment efficacy, Young children learned treated sounds as effectively as Old children did. For treatment efficiency, both groups required a comparable number of sessions, but Young children required longer sessions than Old children. The results suggest that delaying treatment of individual speech sounds is unnecessary, and that a range of sounds should be considered as potential treatment targets.

Keywords: speech sound disorders, treatment, normative data, articulation

Introduction

Children with speech sound disorders (SSD) are at risk for negative impacts across social (McCormack et al., 2009, 2011), academic (Lewis & Freebairn, 1992; Sices et al., 2007), and occupational domains (Feeney et al., 2012). Therefore, it is critical to begin an effective treatment program soon after diagnosis. One of the first steps in treatment planning involves selecting targets for treatment. Although determining what to treat (i.e. which phonemes) is an important question, when to begin treatment on a particular sound may be equally as important. In the present inquiry, we are focusing on English-speaking children’s age and the treatment of liquid sounds (e.g. /ɹ, l/). The normative age of acquisition of these sounds was previously estimated to occur later in a child’s development, with some norms placing this age between 6 and 8, dependent upon the criteria used for acceptability (Sander, 1972; Smit et al., 1990; Templin, 1957). Under a traditional approach to treatment, this would lead to waiting to initiate treatment for these sounds until the normative age passed (e.g., Van Riper & Emerick, 1984). The most recent normative data suggests that most sounds are acquired earlier than previously thought (Crowe & McLeod, 2020; McLeod & Crowe, 2018). This suggests that treatment for previously categorized “late-acquired sounds” could occur earlier in a child’s development. What is unclear is whether younger children respond to treatment for late-acquired sounds in the same way as older children. Therefore, the following discussion centers on the influence of children’s development and the use of normative data in treatment.

Progression of speech sound acquisition in SSD

SSD is a broad term that encompasses any type of disorder that results in errors on producing and perceiving speech sounds (ASHA, n.d.). The focus of the present inquiry is on children who have functional, non-apraxic SSDs (i.e., phonological impairment, articulation impairment). The development of speech sounds in children with SSD differs from that of typically developing (TD) children. Shriberg, Gruber, and Kwiatkowski (1994) examined the long-term developmental sequence, normalization rates, and error types of children with severe SSD. They found that children with severe SSD normalize speech sound errors at different ages than TD children. Between the ages of 4 and 6, children with SSD demonstrated learning of sounds in similar sequences and rates as TD children; however, the initial acquisition of speech sounds was delayed in children with SSD (Shriberg et al., 1994). Therefore, there may be periods in which children are more receptive to therapy. Thus, aligning treatment with this period may promote treatment efficacy.

Causes of age differences in SSD

Previous research examining speech and language acquisition have found that there are periods of accelerated and decelerated learning (Shriberg et al., 1994). The underlying mechanism responsible for these periods could be the result of neurological differences occurring during development. In terms of neurological development, there is evidence demonstrating functional and structural neurological differences between children with SSD and TD children (Liégeois et al., 2014) as well as children who have persistent speech errors (Preston et al., 2012; 2014). These differences were apparent in children at 8 years old. These differences in neurological structure and function may explain age-related differences that were observed longitudinally (Shriberg et al., 1994).

Treatment and normative data

Treatment efficacy for SSDs is generally measured as growth in speech sound accuracy on the treated sound in either treated or untreated words (Gierut, 1998). Treatment efficiency is how rapidly a child can progress through a treatment protocol to normalization (Kamhi, 2006). Historically, there has been an emphasis on describing sounds as “early” or “late” when it comes to selecting treatment targets; however, recent research may shift treatment practices (Storkel, 2019). Mcleod and Crowe (2018) examined the acquisition of English speech sounds cross-linguistically and reported the age at which these speech sounds were acquired. Their findings revealed an earlier acquisition of speech sounds than what previous investigations found (i.e. Sander, 1972; Smit et al.; 1990, Templin, 1957). All sounds were acquired before age 5, except for /θ/, which was not expected to develop until age 6 (Mcleod & Crowe, 2018). The authors further supported these findings by reviewing data on English-speaking children in the US (Crowe & McLeod, 2020). The authors reviewed 15 articles that included 18 907 TD children acquiring English consonant sounds in the United States (Crowe & McLeod, 2020). The findings confirmed the results of their previous study--most consonant classes were acquired by age 5, with liquids acquired by age 5 years, 11 months (Crowe & McLeod, 2020). Thus, the concept of ‘late-acquired’ sounds is evolving, and, with increased awareness of this data, clinical practices are likely to change as well. The use of normative data in making treatment decisions is likely to lead to earlier intervention for all speech sounds. What is unclear is whether young children with SSD (e.g., 4–5 years old) learn the sounds that were formerly considered to be late-acquired in the same way as older children (e.g., 7–8 years old)1. In other words, are younger children “ready” to learn late-acquired sounds at age 4 or 5?

Implications of treatment timing

There are many reasons why earlier treatment for late-acquired sounds may be beneficial for children with SSD. First, earlier intervention may reduce difficulty with acquiring literacy and language skills associated with negative academic outcomes often observed in children with communication disorders (McCormack et al., 2011). Furthermore, as children age and develop, it is less likely their peers produce typical developmental speech sound errors, which increases the likelihood that children with SSDs at later ages (e.g. age 9) will experience social isolation or stigma from peers (Lyons & Roulstone, 2018) or even their classroom teachers (Overby et al., 2007). Reducing these negative outcomes, among others, is of the utmost importance for children with SSD. Although there is potential for positive effects of prompt treatment for SSD, there are some potential drawbacks that may make treatment more difficult. These benefits and drawbacks will be discussed in the following paragraphs.

Given the most recent information on speech sound acquisition, it is now possible to consider a broader set of sounds for treatment targets for children with SSDs at younger ages. Under the new normative data sets, preschoolers acquired the following sounds with 90% accuracy: /v,s,z,ɹ,l,ʃ,ʒ,ʧ,ʤ,ð/. What is unclear is whether children with SSDs at this age are ready for treatment of these sounds. Normative data shows that peers are acquiring these sounds at this age, and previous research has shown that this age has a period of accelerated learning for speech sounds (Shriberg et al., 1994). However, it is possible that younger children are not developmentally ready to follow instructions needed to produce these sounds. Many of these sounds are complex in that they cannot be visualized in conversational speech. This may limit young children’s ability to acquire these sounds through speech therapy.

The focus of the present investigation is on the treatment of liquid sounds. These sounds have the tendency to be persistently in error, with an estimated 1%–2% of these errors persisting into adulthood (Flipsen, 2015). This sound can be produced with either bunched or retroflex tongue postures (Byun et al., 2014), and may not respond to traditional treatment as effectively as with the use of external tools, such as ultrasound visual biofeedback (Preston et al., 2019), or spectral biofeedback (Byun & Hitchcock, 2012). According to a review, the majority of the research using biofeedback methods has been conducted on children who are older (~10), which limits our understanding of whether treatment for later-acquired sounds is effective in younger populations (Hitchcock et al., 2019).

Older children often receive treatment for speech sounds, such as /ɹ, s/, at ages 7 or 8—the age at which previous normative sets placed acquisition of these sounds. While their advanced development may benefit them in terms of attention and ability to follow complex speech cues, there are drawbacks to waiting to provide treatment for speech sounds. Previous research has indicated that adults with a history of moderate phonological or language disorders reported having lower academic and occupational outcomes (Felsenfeld et al., 1992). These participants (age 32–34) reported having received lower grades in school, and required more support services as well as completing fewer years of education overall (Felsenfeld et al., 1992). These results are supported by a cross-sectional study that found that those with a history of SSD performed more poorly on measures of phonology, reading, and spelling as compared to age, sex, and socio-economic controls at four time points across development and into adulthood (Lewis & Freebairn, 1992). Furthermore, a recent population-based study found that children with persistent speech errors achieved lower educational attainment throughout adolescence based on standardized educational assessments when controlling for IQ (Wren et al., 2021). One reason for these poor outcomes is that phonological awareness skills, such as segmentation of sounds in words, is often impacted in children with SSD which leads to difficulty with literacy acquisition (Hesketh, 2004). Another reason for poor literacy outcomes in this population is that children at older ages are learning how to read and having difficulty with even one speech sound can impact their spelling and decoding abilities (Farquharson, 2019). Furthermore, TD children have acquired most speech sounds, with the exception of /θ/, by kindergarten age (Crowe & McLeod, 2020). This sets older children with SSDs at risk of social stigmatization based on their speech and may lead to bullying and difficulty with self-confidence in the academic setting (Krueger, 2019; McLeod et al., 2013).

Purpose

The purpose of the present study was to compare the treatment of “late-acquired” sounds in two age groups of children with SSD. All children were treated on prevocalic /ɹ/ or /l/, depending on which sound was in error. Through the presentation of the current results, we addressed the following research questions:

How do young children (age 4–5) and old children (age 7–8) with SSD learn the /r/ or /l/ sound in terms of treatment efficacy (e.g., speech sound accuracy)?

How do young children (age 4–5) and old children (age 7–8) with SSD learn the /r/ or /l/ sound in terms of treatment efficiency (e.g., number of sessions, and mean session duration)?

In addressing these questions, we explored whether children of different age groups responded differently to treatment in terms of efficacy and efficiency. Our hypothesis was that young children may attain a higher level of accuracy in fewer sessions than older children due to increased plasticity, less time spent producing errors, and by virtue of being in a theoretical phase of accelerated learning (Shriberg, et al., 1994).

Materials and methods

Experimental Design

The present study used a single-subject multiple baseline across participants design to provide an intensive and comprehensive examination of within-subjects effects of the treatment protocol. Eight participants met inclusionary criteria and were enrolled in the study. Seven of the eight participants were treated with the same sound (e.g., /ɹ/), while another participant (Young 4) was treated on /l/. Treatment sounds were selected based on the late-acquired sounds each child produced in error. Only liquid sounds were included because they share phonetic features, these are traditionally designated as late-acquired sounds, and both younger and older children often produce these sounds with a substitution of /w/, rather than a distortion (Smit, 1993). In the case of these participants, all initial sounds were produced with a /w/ substitution for the target sounds and no deletions or distortions were observed in initial position. With this design, the external validity of the experiment was increased by providing a within-group replication of the same treatment for the same sound. This demonstrated whether different children showed similar outcomes for the same sound.

Each participant was assigned a baseline of three, four, or five. As each new participant enrolled, the baseline increased by one up to five baselines. The examiner was not blinded to the child’s baseline condition or target sound. The child’s first session contained a full probe of their phonetic and phonological inventories from the Phonological Knowledge Protocol (PKP), which elicits all sounds in 15–17 vowel contexts and positions: 5 initial, 5–7 medial, 5 final (Dinnsen & Gierut, 2008). If the child’s accuracy for their treatment target on this probe was 0%–7%, then the next two sessions probed these sounds using the 15–17 vowel contexts and positions from the PKP. Accuracy on these probes was required to be 0%–7% in each baseline session to be included in the treatment portion of the study.

Participants

Participants were required to score within normal limits on a series of standardized, norm-referenced assessments. These assessments examined children’s receptive language abilities (Test of Language Development (Primary), 4th Edition (TOLD-P4); Newcomer & Hammill, 2002), hearing (20 dB HL at 1, 2, and 4 kHz), and nonverbal intelligence (Reynolds Intelligence Assessment Scales (RIAS); Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2003). Additionally, participants’ errors were required to be rated as “linguistic” in nature (not motoric) as measured by the Kaufman Speech Praxis Test (KSPT; Kaufman, 1995). In terms of inclusionary criteria for articulation, participants were required to score below the 10th percentile on the Goldman-Fristoe Test of Articulation (GFTA; Goldman & Fristoe, 2000; 2015). For a complete description of errors observed on this assessment, please refer to Appendix A. This study took place as the 3rd edition of this assessment was released, so the first two participants in each group were administered the GFTA-2, while the last two participants in each group were administered the GFTA-3. The correlation between scores on these two assessments is reported to be 0.83, so there was no concern that one test was more or less sensitive than the other (Goldman & Fristoe, 2015).

Seventeen monolingual children were recruited through word-of-mouth and social media announcements (e.g., Facebook). Participants were speakers of a Midwestern dialect of American English. They were divided into two age groups: 4 years, 0 months to 5 years, 11 months (the “Young” group) and 7 years, 0 months to 8 years, 11 months (the “Old” group). These age groups were selected because the younger group (4–5) was at the age at which the most recent normative data sets indicate that the /ɹ/ and /l/ sounds should be acquired (Crowe & McLeod, 2020; McLeod & Crowe, 2018). The Old group (7–8) were beyond the age at which older normative sets suggested the /ɹ/ and /l/ sounds should be acquired (Smit et al., 1990). Two participants withdrew due to scheduling conflicts, 2 were excluded for accurately producing the treatment sound on a baseline probe, 4 were excluded for scoring above the 10th percentile on the GFTA, and 1 was excluded for scoring below the 10th percentile on the receptive language test. Therefore, 8 participants advanced to the treatment portion of the study. Of these, four were male, and four were female. All children who advanced to treatment were Caucasian and non-Hispanic, per parent report. All but two participants (one Old and one Young) were receiving treatment from their school-based SLPs in addition to the treatment received for the present study. Those who were receiving treatment from their school-based providers continued during the study without interruption. Treatment goals at the time of the study for these children were not provided, but the parents reported past treatment targets, and they are listed in Table 1. The selected treatment sound for each child was absent from the children’s phonetic inventory based on GFTA and PKP data. All children enrolled in the study produced either substitutions or omissions for their error sound (e.g. /ɹ/ →[w] and /ɹ/ omission in final position).

Table 1.

Participant age, treatment target for the present study, prior or present treatment targets based on parent report, baseline condition, and scores on inclusionary tests.

| Subject | Age (years; months) | Previous Treatment Targets | Number of Baselines | GFTA %ile rank (Standard score; Severity Classification) | RIAS %ile rank (NIX) | TOLD-P4 RLI %ile rank (Index score) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Old 1 | 8;10 | Sounds not reported for prior treatment | 3 | 2 (79; Borderline) | 47 (99) | 35 (94) |

| Old 2 | 8;1 | /f, h, z, ɹ/ | 4 | 1 (50; Severe) | 70 (108) | 70 (105) |

| Old 3 | 7;11 | / ɹ / | 4 | 0.1 (52; Severe) | 66 (106) | 90 (119) |

| Old 4 | 8;3 | /tʃ, g, l, ɹ / | 5 | 0.1(40; Severe) | 45(99) | 82(114) |

| Young 1 | 4;11 | /s, g, ɹ, k, ʃ, l-clusters/ | 3 | 8 (79; Borderline) | 77 (111) | 55 (102) |

| Young 2 | 5;9 | “all” | 3 | 0.1(43; Severe) | (92) | 55(102) |

| Young 3 | 4;10 | /k, ɹ, s, θ, f/ | 4 | 5 (68; Severe) | 34 (94) | 77 (111) |

| Young 4 | 4;3 | “none” | 5 | 1(63; Severe) | 34(94) | 50(100) |

Note. GFTA refers to the Goldman-Fristoe Test of Articulation, and the severity descriptions are based on descriptions from the examiner’s manual; RIAS refers to the Reynolds Intellectual Assessment Scales; NIX refers to Nonverbal intelligence index; TOLD-P4 refers to the Test of Language Development-Primary: Fourth Edition; RLI refers to Receptive Language Index.

Materials

The treatment pictures were an adapted story, Bill and Pete (DePaola, 1996), as used in Gierut et al. (2010). The names of items and verbs throughout the story were substituted with 8 CVC nonwords selected from a database (Storkel, 2013). Nonwords were used for treatment instead of real words because previous research has found that the use of nonwords engages children in creating new lexical entries and promotes broad change to the phonological system (Cummings & Barlow, 2011; Gierut & Morrisette, 2010). The final consonants of these nonwords were controlled to be early-acquired sounds /p,b,m,n,t,d/ to increase the likelihood that children had acquired these sounds, so that treatment was focused on the acquisition of the initial sound only. Participants in this study did not produce these sounds in error. Phonotactic probability and phonological neighborhood density of these nonwords were evaluated and used to select a mixture of high and low biphone sequences and dense and sparse neighborhoods based on child corpus values (Storkel, 2013; Storkel & Hoover, 2010). For a complete summary of treatment nonwords, refer to Appendix B.

Procedures

Once inclusionary criterion were met, the treatment protocol was initiated. Children received treatment two to three times per week in either their school or the lab setting. All treatment procedures were approved by the institutional review board at each university where data collection and analysis took place (#20180510BK01978 & #00004092). The treatment procedures were consistent with previous treatment studies in which two phases (Imitation, Spontaneous) are conducted and movement through phases requires meeting a criterion (e.g., Gierut, 1999). To move to the Spontaneous phase, children were required to attain 75% accuracy across 2 consecutive sessions, or a maximum of 14 sessions in this phase. To complete the Spontaneous treatment phase, children were required to attain 90% accuracy across 3 consecutive sessions, or a maximum of 24 sessions in this phase. The maximum cap was set to protect participants from continuing a therapy that is not working for their needs, and is twice as high as that of similar study procedures (Gierut, 1999).

The examiner for each session was either the first author (a licensed SLP) or a trained graduate student in SLP. All were speakers of American English as their first language and of the same dialectal backgrounds as the children they were treating. At the beginning of each session, the examiner noted the start time on the scoresheet. Children were seated in front of a computer and the examiner read a story to familiarize and contextualize the treatment nonwords. Then drill play with the nonwords was conducted. Each of eight nonwords were presented one at a time in sequential order. This combination of 8 nonwords was repeated 10 times for a total of 80 scored trials. The examiner judged each initial production attempt in real time during the session and a second judge listened to audio files and independently scored the sessions to verify the examiner’s scoring. Agreement between examiners was found to be 96.2%. Once 80 trials were completed, the examiner noted the end time on the scoresheet and the session was terminated.

Imitation phase.

In the first phase of treatment, each child was shown each nonword on individual slides and the examiner provided an imitative prompt (e.g. “Say [treatment word]”). The child then imitated the word, and the examiner provided knowledge of results (e.g., whether the response was correct) and knowledge of performance (e.g., placement) feedback (Maas et al., 2008). Cues were individualized for each child to promote the most accurate production (Byun et al., 2014). These included placement cues (e.g., “Make sure the sides of your tongue touch your teeth!”) as well as visual cues (e.g., a mirror), perceptual cues (e.g., “That sounded like a /w/ sound, not an /l/”), and metalinguistic cues (e.g., “That was a good growling sound!”). These were selected based on the child’s response to the cues and the types of errors the child made. For example, if the child obtained a correct production, the examiner provided relevant feedback such as “Good job! You raised your tongue up”! If the child did not get the word correct, the examiner provided feedback relevant to the child’s error such as “That wasn’t correct, you didn’t raise your tongue up.” The child would complete a second attempt, and would again receive feedback. These second attempts allowed the dose to vary by accuracy. Thus, a lower session accuracy is associated with a higher dose (or more second attempts), and a higher session accuracy was associated with a lower dose (fewer second attempts). This allowed for a threshold dose and tailoring a higher or lower dose to meet the child’s needs. The PKP was administered upon completion of the Imitation phase to examine the changes that occurred due to treatment. This probe is henceforth known as the “phase shift probe”.

Spontaneous phase.

The Spontaneous phase procedures were nearly identical to those of the Imitation phase. However, rather than providing a verbal model for imitation, children were asked “What’s this”? by the examiner. If the child said “I don’t know” or a similar response, the examiner responded by following a cueing hierarchy. First, the child was provided with a cloze option, such as “This is the baby crocodile named …”. If the child failed to respond with the treatment word, the examiner elicited a delayed imitation by saying, “Is it a [treatment word] or a table”? If the child still did not respond correctly, direct imitation was prompted “Say [treatment word]”. As in the Imitation phase, the first responses were scored.

After the completion of treatment, children underwent “immediate post testing” at their next session. The post testing was a repeated administration of the full PKP. Then the PKP was administered again 2 weeks after treatment was terminated to determine whether any growth was maintained. This test is referred to as “delayed post test”. While it is possible that the repeated productions of these words influenced the observed change in scores on the PKP, it is unlikely because children did not receive any prompt to use their new productions of treatment sounds, did not receive any feedback on their productions, and due to the high number of items on this protocol (198 words).

Procedural Fidelity

Procedural fidelity of the examiner for the treatment group to the treatment procedures was judged by a trained rater. Thirty percent of treatment videos for each participant were checked against a treatment script. The rater found 100% fidelity to treatment procedures in terms of providing the correct script for treatment, the correct picture stimuli, and the correct number of exposures to treatment nonwords.

Data Analysis

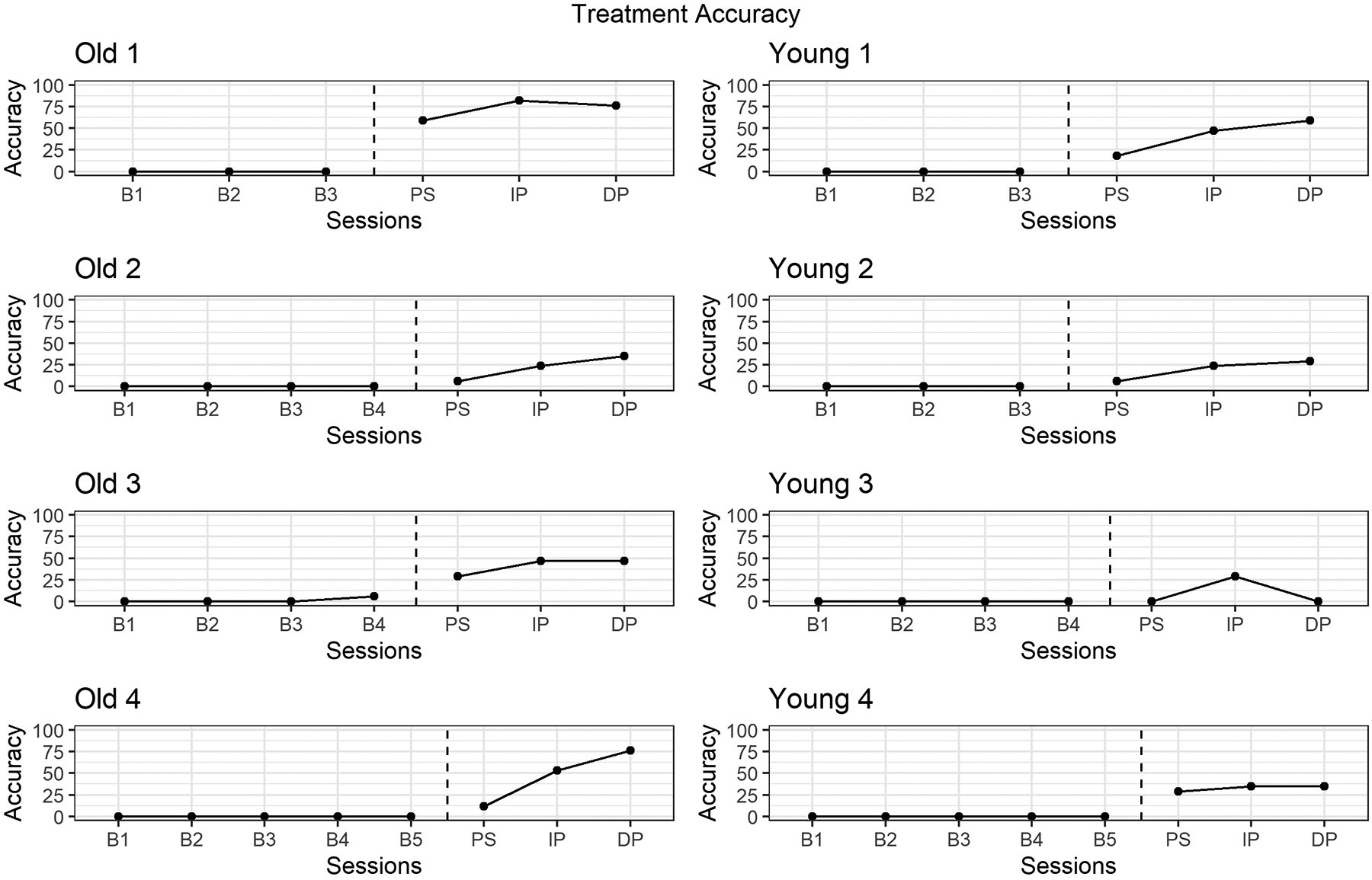

To measure treatment efficacy, the percent accuracy of the production of treatment sounds in untreated real words was calculated based on perceptual judgment. If the treated phoneme was produced without error (i.e., distortions, substitutions), it was counted as correct. Accuracy of untreated phonemes was not scored. These productions were elicited through administering the PKP probe at pretest (baseline), at phase shift, immediate posttest, and 2-week delayed posttest in 17 different words which contained target treatment sounds in initial, medial and final positions in words. Accuracy on untreated real words provides a measure of children’s generalization to non-treatment contexts. These were plotted in Figure 1 and described within subjects and between each age group.

Figure 1:

PKP probe accuracy at baseline, phase shift, immediate posttest, and 2-week delayed posttest.

To measure treatment efficiency, the total number of sessions were calculated for each child. In addition, descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, range) of the treatment session duration for each participant was calculated.

Reliability

Untreated real words containing treatment targets were phonetically transcribed by a trained rater using Phon software (Hedlund & Rose, 2019; Rose et al. 2006; Rose & MacWhinney, 2014). These words were transcribed from audio recordings of the sessions by the examiner and transcribed a second time by a trained second scorer who was blind to the treatment condition. Agreement between transcribers on targeted treatment sounds in untreated real words was found to be 96.18%. Any disagreements were discussed and the raters listened to the token again to reach agreement. If consensus was not reached, a third judge trained in phonetic transcription was consulted to provide a decision.

Results

Treatment Accuracy

Children’s accuracy on untreated real words at each time point were plotted in Figure 1. Accuracy values are based on productions of sounds in 17 untreated real words containing the target sounds. Old 1 demonstrated a stable baseline, with imitation sessions promoting a change in accuracy at phase shift (59%). This progress continued on untreated /r/ words with accuracy at 82% at immediate posttest, and progress was maintained after treatment was discontinued with accuracy at delayed posttest at 76%. Young 1 also demonstrated a stable baseline, and an increase in accuracy at phase shift (18%), and continued to show growth at immediate posttest (47%) and further growth once treatment was discontinued with 59% accuracy at delayed posttest. All other participants, with the exception of Young 3, demonstrated similar patterns of stable baselines, with growth at phase shift and immediate posttest and maintained accuracy from immediate posttest to delayed posttest (Old 3, Young 2, Young 4) or increased accuracy at delayed posttest (Old 2, Old 4). While Young 3 demonstrated a stable baseline, they did not demonstrate an increase in accuracy on untreated real words as a result of the imitation phase of treatment at phase shift (0%). Young 3 attained 29% accuracy at immediate posttest demonstrating some effect of treatment, but this progress was not maintained once treatment was discontinued as shown by a return to baseline levels (0%) at delayed posttest. These results indicate that treatment was effective for all children, with the exception of Young 3. We considered that since children were treated on sounds in the initial position only, their performance on real words with treatment sounds in initial position (excluding medial and final position words) would differ from the results found here. We conducted an analysis on treatment sounds in initial position only and found no differences in our conclusion.

Treatment Efficiency

The number of sessions for each participant is provided by phase in Table 2. Overall, the Young group required 17 sessions on average (SD = 3, range 13–20) whereas the Old group required 19 sessions on average (SD = 3, range 17–24). Within the Imitation treatment phase, children in the Young group required 8 sessions on average (SD = 2, range 7–10), whereas the Old group required 12 sessions on average (SD = 1, range 10–14). Within the Spontaneous phase, children in the Young group required 9 sessions to meet criterion (SD = 4, range 3–13), on average, whereas the Old group required 7 sessions (SD = 4, range 3–14). Although the overall number of sessions was similar between Young and Old children, the differences in each phase are notable. Between groups, Young children required fewer sessions in the Imitation phase than Old children; conversely, Old children required fewer sessions in the Spontaneous phase than Young children. In addition, the variability among both groups was higher in the Spontaneous phase and the differences within groups were notable as well. All Old children, with the exception of Old 3 required more sessions in the Imitation phase than the spontaneous phase. Young children were somewhat divided—Young 1 and 2 required fewer sessions in the Imitation phase than the Spontaneous phase, while Young 3 and 4 required more sessions in the Imitation phase than the Spontaneous phase. This suggests that, while the group means suggest Young children may progress through the Imitation phase in fewer sessions than Old children, some variability does exist. Overall, these results suggest that Young children responded accurately to imitative prompts more often than Old children, since fewer sessions were required to reach the accuracy level of 75% across 2 consecutive session.

Table 2.

Number of sessions required in each treatment phase and overall, by participant.

| Participant | Sessions in Imitation Phase | Sessions in Spontaneous Phase | Sessions Overall |

|---|---|---|---|

| Old 1 | 12 | 7 | 19 |

| Old 2 | 12 | 5 | 17 |

| Old 3 | 10 | 14 | 24 |

| Old 4 | 14 | 3 | 17 |

| Young 1 | 7 | 13 | 20 |

| Young 2 | 6 | 11 | 17 |

| Young 3 | 10 | 7 | 17 |

| Young 4 | 10 | 3 | 13 |

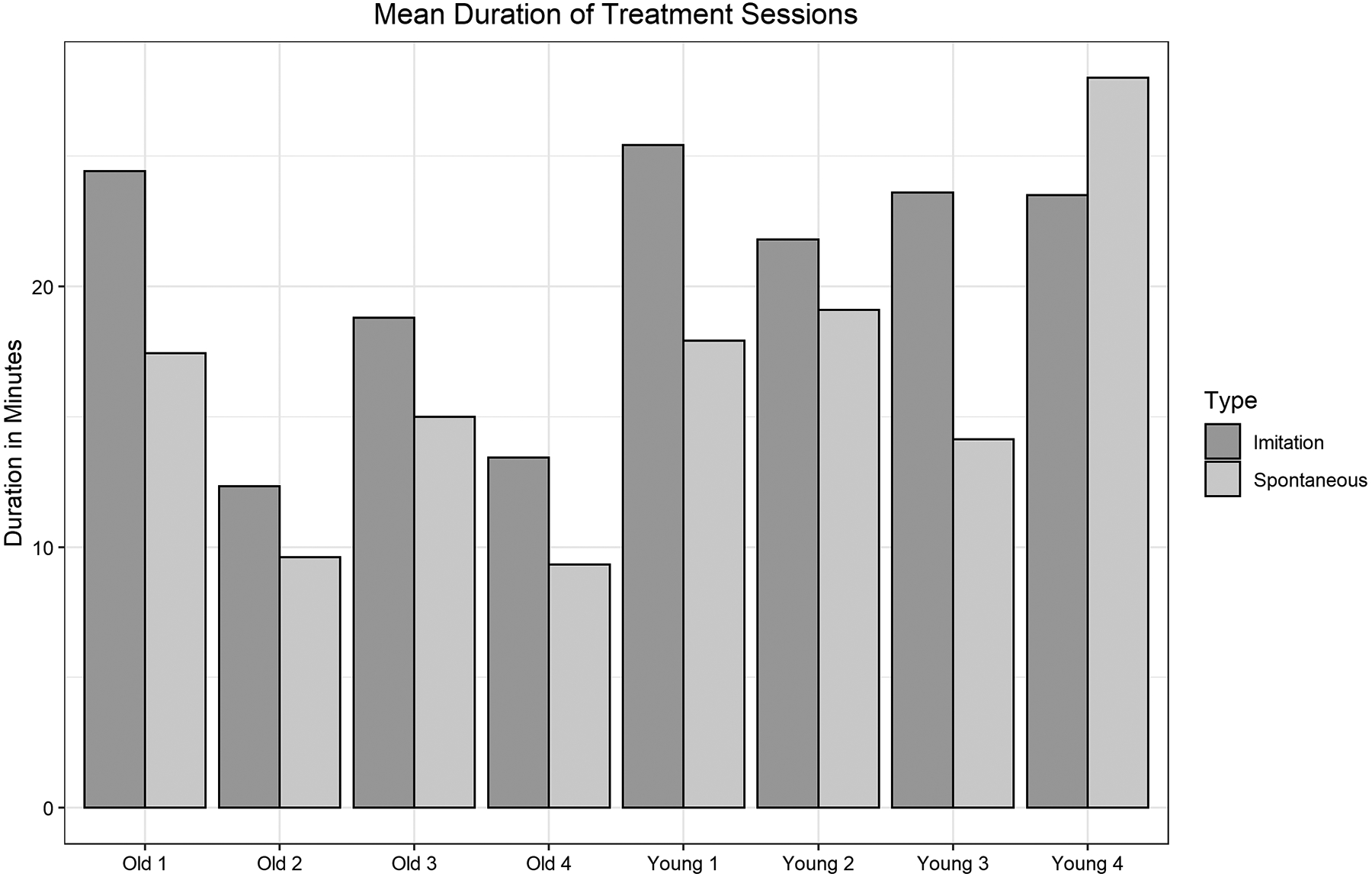

The duration of sessions differed between age groups. These values are shown in Figure 2. Young children required sessions 21.20 minutes in duration overall, on average, to meet the 80-trial requirement per session (SD = 1.95, range 19.7–24.54), while Old children required 15.67 minutes on average overall (SD = 4.02, range 11.53–21.84). This finding may suggest that younger children require more time for feedback and redirection in treatment sessions. All participants with the exception of Young 4 required longer sessions in the Imitation phase than the Spontaneous phase.

Figure 2:

Mean number of minutes required for each subject for each phase.

Discussion

Traditionally, some sounds were not considered for treatment targets for young children because these sounds were not expected to develop until a later age according to available data (e.g. Sander, 1972; Smit et al., 1990). However, recent findings of normative acquisition have shown that children learn these sounds much earlier than previously observed (Crowe & McLeod, 2020; McLeod & Crowe, 2018). Considering these findings, it is important to examine the efficacy and efficiency of treatment in younger children to guide clinical practice. The purpose of the present study was to determine whether young children learned late-acquired sounds because of treatment in a similar way as older children did. The results of the present study showed that all but one child showed progress because of treatment—regardless of age.

Treatment Efficacy

In terms of treatment efficacy, most children demonstrated progress at immediate posttest, with some observed differences at delayed posttest. Based on productions of untreated words from the PKP, children in both age groups demonstrated growth in accuracy of target phonemes from baseline to immediate posttest. All children, with the exception of Young 3, demonstrated growth at phase shift, and all children except Young 3 maintained their level of accuracy at delayed posttest. This finding was not surprising as there are many treatment studies that demonstrate effective results in children, including those age 8 and those even older (Sugden et al., 2018). Although the number of participants in the present study was limited, these findings are consistent with previous research suggesting that treatment for at least some late-acquired sounds, like /l, ɹ/ can be effective regardless of age.

Both groups attained a comparable level of accuracy of their treatment sounds. It is, however, important to acknowledge that there did not appear to be any penalty for waiting to treat late-acquired sounds. That said, SSDs often carry secondary impacts in terms of academic success (Lewis & Freebairn, 1992; Sices et al., 2007) and socioemotional development (Krueger, 2019; McLeod et al., 2013). Therefore, to aid in making treatment decisions, clinicians must evaluate the whole child on a case-by-case basis to aid in treatment decisions, rather than basing such decisions on age and errors alone.

The treatment of complex treatment targets for SSD, such as late-acquired sounds, is well-studied. Considering recent knowledge regarding speech sound development (McLeod & Crowe, 2018), the connection between treating complex targets and a child’s age should be emphasized in future inquiries (Storkel, 2019). The results of the present study demonstrated that late-acquired sounds are suitable treatment targets for younger children, and age did not have an impact on their success in treatment, aside from treatment session duration. Much of the work on complex targets involves a discussion of generalization to untreated sounds (e.g., Gierut, 2001), as well as the use of lexical properties of words and nonwords to promote broader change to the phonological system (Storkel, 2018). While generalization to untreated sounds was not directly targeted in the present study, we found that the Young children had more errors than their Old counterparts due to their age differences, and the number of errors required to attain the GFTA score needed to qualify for the study. Old children had reached the point in their development—whether delayed or not—that most errors had normalized. In fact, most Old participants only produced their targeted treatment sound in error, but, due to their age, the single-sound error was sufficient for them to score below the 10th percentile on the articulation assessment. Therefore, answering a broader question of overall generalization to untreated sounds between the two age groups is not possible in the context of the present study.

In terms of lexical properties of words, the use of nonwords allows for control over features such as phonological neighborhood density. Previous research has found that controlling for factors, such as phonological neighborhood density and phonotactic probability can promote favorable change to a child’s speech sound system (Storkel, 2018). In addition, the use of nonwords promotes rapid change in the phonological system (Gierut et al., 2010). The results of the present study are in alignment with these findings in that we controlled for lexical factors of nonwords which resulted in growth for nearly all participants.

Treatment Efficiency

We predicted that Young children would progress through treatment in fewer sessions than Old children due to being in a theoretical phase of accelerated learning for speech sounds (Shriberg et al., 1994). Surprisingly, Young children required nearly the same number of sessions overall as Old children. Despite this similarity, when examining the results by phase, some differences emerged. Young children required fewer sessions on average than Old children to meet criterion in the Imitation phase. This suggests that Young children responded more accurately to imitative prompts than Old children. Conversely, Old children required fewer sessions, on average, in the Spontaneous phase than Young children, which is somewhat inflated due to the high number of sessions required by participant Old 3. All other children in the Old group required the same or fewer sessions in the Spontaneous phase than two of the Young children, which suggests that Old children may transfer articulation skills more readily, but there is some variability from child to child. Both types of prompts are frequently used in the treatment of SSD (Baker et al., 2018; Diepeveen et al., 2020). Imitative prompts are more directive and often used in the early stages of treatment to establish accurate productions of speech sounds. Spontaneous prompts, on the other hand, require the child to accurately produce words without the aid of a perceptual model. The results of the present study indicate that Old children may respond more accurately to this type of prompting in fewer sessions than Young children. That is, Old children transferred their accurate articulation skills from the Imitation phase of treatment to the Spontaneous phase more readily than Young children.

In terms of session duration, Young children required slightly longer sessions regardless of accuracy in the treatment sessions, and the amount of corrective feedback required. Although Young children required longer sessions, both the Young and Old group’s mean session durations were well within typical session lengths seen in clinical practice (Brumbaugh & Smit, 2013; McLeod & Baker, 2014; Mullen & Schooling, 2010; Sugden et al., 2018). One possible reason for this difference in session duration is that all children completed the same number of first attempt trials. It is possible that all 80 trials were not needed, and that children would have reached the same level of success with fewer trials. Since our variable of interest was differences among age groups when administered the same treatment, we did not test this possibility. Our hypothesis, based on the present data, is that this difference was the result of children’s prior experiences with treatment. Young children were all preschool-aged, and less-experienced with the process of speech therapy and schooling in general. Due to their young age, they had been receiving intervention services for less time than older participants had. The examiner in the present study often had to redirect Young children to the treatment and had to address questions. The Old children, on the other hand, had received speech therapy in the schools and were familiar with drill-based tasks. Therefore, the difference in treatment efficiency is likely to occur regardless of treatment target. Although we expect younger children to need slightly longer sessions due to their maturity level and inexperience with treatment, this does not suggest that SLPs should delay treatment for late-acquired sounds in young children with SSD.

Limitations and Future Directions

The present study only included eight participants, which poses issues with sufficient statistical power and generalizability. This design (single subject) ensured a complete examination of children’s skills at onset and to explore which factors may be relevant to prepare for a larger group design. Another limitation is that the treatment sounds were limited to the liquid feature class. It is thus unclear whether these findings would generalize to other sound classes. Finally, it is possible that since most children were receiving school-based services in addition to the treatment in this study that they responded differently to treatment. However, those who were not receiving treatment (Old 1, Young 4) did not respond differently than those who had a history of speech therapy.

Conclusion

The present study provides data that supports the selection of late-acquired sounds for all children with SSD. We found that children aged 4–5 were as successful in treatment for late-acquired sounds (/ɹ/ and /l/) as children aged 7–8. Therefore, the use of associating treatment targets with a child’s age and with normative data is not necessary. Children do not require treatment targets that adhere to the developmental order of acquisition of phonemes. Selecting late-acquired sounds, especially in younger children with many errors, may lead to generalization to other untreated sounds (Gierut, 2001; Gierut et. al., 2010), which could reduce the overall amount of time spent in therapy. Young children may require slightly longer sessions than Old children to achieve the same trial-based dose, but the total number of sessions required for both groups, on average, was similar. This finding suggests that treating late-acquired sounds does not require more intensive treatment intensity for either age group. The full range of sounds should be considered as potential treatment targets.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge the schools and families who participated in this study, as well as the speech-language pathologists who referred children.

Funding statement:

This work was supported by the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders under grant number 5 T32 DC000052 - 17; the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under grant number P20GM103432. This study was registered as a clinical trial September 10, 2018 under identifier NCT03663972.

Appendix A

Errors made by each participant

| Participant | Target sound | Actual Produced Sound | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial position | Medial position | Final position | ||

| Old 1 | /ɹ/ | [w] and in clusters | [w] | Ø |

| Old 2 | /ʃ/ | [s̪] | [s̪] | [s̪] |

| Old 3 | /ɹ/ | [w] and in clusters | [w] | [w] |

| Old 4 | /ʃ/ | [s] | [s] | [s] |

| Young 1 | /f/ | [f] | Ø | [p] |

| Young 2 | /k/ | [h] | [ʔ] | [ʔ] |

| Young 3 | /ŋ/ | X | Ø | [ŋ] |

| Young 4 | /p/ | [p] | [b] | [p] |

Note. Sound errors observed by each participant during pretesting on the GFTA 2nd or 3rd edition. “Ø” indicates the participant deleted the target sound, and “X” indicates the sound was not assessed in that position.

Appendix B

Characteristics of treatment nonwords including biphone probabilities and neighborhood density

| Word | CV Biphone Probability | Code | VC Biphone Probability | Code | Neighborhood Density | Neighborhood Density Code |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| /ɹ/ treatment words | ||||||

| ɹib | 0.0044 | high | 0.0007 | low | 8 | low |

| ɹɛb | 0.0085 | high | 0.0007 | low | 8 | low |

| ɹad | 0.0011 | high | 0.0025 | high | 16 | high |

| ɹʌp | 0.0026 | high | 0.0012 | high | 14 | high |

| ɹᴐɪm | 0.0001 | low | 0.0000 | low | 4 | low |

| ɹʊp | 0.0002 | low | 0.0003 | low | 4 | low |

| ɹaʊn | 0.0005 | low | 0.0040 | high | 10 | high |

| ɹʊd | 0.0002 | low | 0.0013 | high | 12 | high |

| Mean | 0.0022 | 0.0013 | 9.5 | |||

| /l/ treatment words | ||||||

| læn | 0.0045 | high | 0.0144 | high | 25 | high |

| lʌp | 0.0018 | high | 0.0012 | high | 10 | high |

| lɑd | 0.0018 | high | 0.0025 | high | 13 | high |

| lɪm | 0.0062 | high | 0.0068 | high | 11 | high |

| lɛb | 0.0040 | high | 0.0007 | low | 7 | low |

| loʊp | 0.0022 | high | 0.0010 | low | 12 | high |

| lʊd | 0.0003 | low | 0.0013 | low | 12 | high |

| lɑʊb | 0.0003 | low | 0.0001 | low | 1 | low |

| Mean | 0.0026 | 0.0035 | 11.38 | |||

Footnotes

The rationale for the use of these ages as ‘young’ and ‘old’ is provided in the participant section of the methods

Disclosure statement:

The authors have no relevant financial or nonfinancial disclosures or conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributor Information

Breanna I. KRUEGER, University of Wyoming.

Holly L. STORKEL, University of Kansas.

References

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (n.d.) Speech Sound Disorders: Articulation and Phonology. (Practice Portal). Retrieved from www.asha.org/Practice-Portal/Clinical-Topics/Articulation-and-Phonology/.

- Baker E, Williams AL, McLeod S, & McCauley R (2018). Elements of phonological interventions for children with speech sound disorders: The development of a taxonomy. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 27(3), 906–935. 10.1044/2018_AJSLP-17-0127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brumbaugh KM, & Smit AB (2013). Treating children ages 3–6 who have speech sound disorder: a survey. Language, speech, and hearing services in schools, 44(3), 306–319. 10.1044/0161-1461(2013/12-0029) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byun TM, & Hitchcock ER (2012). Investigating the use of traditional and spectral biofeedback approaches to intervention for /r/ misarticulation. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 21(3), 207–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byun TM, Hitchcock ER, & Swartz MT (2014). Retroflex versus bunched in treatment for rhotic misarticulation: Evidence from ultrasound biofeedback intervention. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 57(6), 2116–2130. 10.1044/2014_JSLHR-S-14-0034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crowe K, & McLeod S (2020). Children’s English consonant acquisition in the United States: A review. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 29(4), 2155–2169. 10.1044/2020_AJSLP-19-00168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings AE, & Barlow JA (2011). A comparison of word lexicality in the treatment of speech sound disorders. Clinical Linguistics and Phonetics, 25(4), 265–286. 10.3109/02699206.2010.528822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diepeveen S, van Haaften L, Terband H, de Swart B, & Maassen B (2020). Clinical reasoning for speech sound disorders: Diagnosis and intervention in speech-language pathologists’ daily practice. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 29(3), 1529–1549. 10.1044/2020_AJSLP-19-00040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinnsen DA, & Gierut JA (Eds.). (2008). Optimality theory, phonological acquisition and disorders. Equinox Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Farquharson K (2019). It Might Not Be “Just Artic”: The Case for the Single Sound Error. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 4(1), 76–84. 10.1044/2018_PERS-SIG1-2018-0019 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney R, Desha L, Ziviani J, & Nicholson JM (2012). Health-related quality-of-life of children with speech and language difficulties: A review of the literature. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 14(1), 59–72. 10.3109/17549507.2011.604791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenfeld S, Broen PA, & McGue M (1992). A 28-year follow-up of adults with a history of moderate phonological disorder. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research, 35(5), 1114. 10.1044/jshr.3505.1114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flipsen P (2015). Emergence and prevalence of persistent and residual speech errors. Seminars in Speech and Language, 36(04), 217–223. 10.1055/s-0035-1562905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gierut JA (1998). Treatment efficacy: Functional phonological disorders in children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research: JSLHR, 41(1), S85–100. 10.1044/jslhr.4101.s85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gierut JA (1999). Syllable Onsets: Clusters and adjuncts in acquisition. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 42(3), 708–726. 10.1044/jslhr.4203.708 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gierut JA (2001). Complexity in phonological treatment. Language Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 32(4), 229. 10.1044/0161-1461(2001/021) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gierut JA, & Morrisette ML (2010). Phonological learning and lexicality of treated stimuli. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 24(2), 122–140. 10.3109/02699200903440975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gierut JA, Morrisette ML, & Ziemer SM (2010). Nonwords and generalization in children with phonological disorders. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 19(2), 167–177. 10.1044/1058-0360(2009/09-0020) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman R (2015). Goldman-Fristoe Test of Articulation–Third Edition (GFTA-3) (3rd ed.). Pearson. [Google Scholar]

- Hitchcock ER, Swartz MT, & Lopez M (2019). Speech sound disorder and visual biofeedback intervention: A preliminary investigation of treatment intensity. Seminars in Speech and Language, 40(2), 124–137. 10.1055/s-0039-1677763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamhi AG (2006). Treatment decisions for children with speech-sound disorders. Language, speech, and hearing services in schools, 37(4), 271–279. 10.1044/0161-1461(2006/031) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger BI (2019). Eligibility and speech sound disorders: Assessment of social impact. 4(1), 85–90. 10.1044/2018_PERS-SIG1-2018-0016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis BA, & Freebairn L (1992). Residual effects of preschool phonology disorders in grade school, adolescence, and adulthood. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research, 35(4), 819. 10.1044/jshr.3504.819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liégeois F, Mayes A, & Morgan A (2014). Neural correlates of developmental speech and language disorders: Evidence from neuroimaging. Current Developmental Disorders Reports, 1(3), 215–227. 10.1007/s40474-014-0019-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons R, & Roulstone S (2018a). Well-being and resilience in children with speech and language disorders. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research, 1. 10.1044/2017_JSLHR-L-16-0391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maas E, Robin DA, Austermann Hula SN, Freedman SE, Wulf G, Ballard KJ, & Schmidt RA (2008). Principles of motor learning in treatment of motor speech disorders. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 17(3), 277–298. 10.1044/1058-0360(2008/025) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack J, Harrison LJ, McLeod S, & McAllister L (2011). A nationally representative study of the association between communication impairment at 4–5 years and children’s life activities at 7–9 years. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research, 54(5), 1328. 10.1044/1092-4388(2011/10-0155) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCormack J, McLeod S, McAllister L, & Harrison LJ (2009). A systematic review of the association between childhood speech impairment and participation across the lifespan. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 11(2), 155–170. 10.1080/17549500802676859 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mcleod S, & Baker E (2014). Speech-language pathologists’ practices regarding assessment, analysis, target selection, intervention, and service delivery for children with speech sound disorders. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 28(7–8), 508–531. 10.3109/02699206.2014.926994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod S, & Crowe K (2018). Children’s consonant acquisition in 27 languages: A cross-linguistic review. In American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology (Vol. 27, Issue 4, pp. 1546–1571). 10.1044/2018_AJSLP-17-0100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod S, Daniel G, & Barr J (2013). “When he’s around his brothers … he’s not so quiet”: The private and public worlds of school-aged children with speech sound disorder. Journal of Communication Disorders, 46(1), 70–83. 10.1016/J.JCOMDIS.2012.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mullen R, & Schooling T (2010). The national outcomes measurement system for pediatric speech-language pathology. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 41(1), 44–60. 10.1044/0161-1461(2009/08-0051) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overby M, Carrell T, & Bernthal J (2007). Teachers’ perceptions of students with speech sound disorders: A quantitative and qualitative analysis. Language Speech and Hearing Services in Schools, 38(4), 327. 10.1044/0161-1461(2007/035) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston JL, Felsenfeld S, Frost SJ, Mencl WE, Fulbright RK, Grigorenko EL, Landi N, Seki A, & Pugh KR (2012). Functional brain activation differences in school-age children with speech sound errors: speech and print processing. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 55(4), 1068–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston JL, McAllister T, Phillips E, Boyce S, Tiede M, Kim JS, & Whalen DH (2019). Remediating Residual Rhotic Errors With Traditional and Ultrasound-Enhanced Treatment: A Single-Case Experimental Study. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 28(3), 1167. 10.23641/asha. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preston JL, Molfese PJ, Mencl WE, Frost SJ, Hoeft F, Fulbright RK, Landi N, Grigorenko EL, Seki A, & Felsenfeld S (2014). Structural brain differences in school-age children with residual speech sound errors. Brain and Language, 128(1), 25–33. 10.1016/j.bandl.2013.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sander EK (1972). When are speech sounds learned? Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 37(1), 55. 10.1044/jshd.3701.55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shriberg LD, Gruber FA, & Kwiatkowski J (1994). Developmental phonological disorders III: Long term speech-sound normalization. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 37(5), 1151–1177. 10.1044/jshr.3705.1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sices L, Taylor HG, Freebairn L, Hansen A, & Lewis B (2007). Relationship between speech-sound disorders and early literacy skills in preschool-age children: impact of comorbid language impairment. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics : JDBP, 28(6), 438–447. 10.1097/DBP.0b013e31811ff8ca [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit AB (1993). Phonologic error distributions in the Iowa-Nebraska articulation norms project: Consonant singletons. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 36(3), 533–547. 10.1044/jshr.3603.533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smit AB, Hand L, Freilinger JJ, Bernthal JE, & Bird A (1990). The Iowa articulation norms project and its Nebraska replication. Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 55(4), 779. 10.1044/jshd.5504.779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A, & Goffman L (1998). Stability and Patterning of Speech Movement Sequences in Children and Adults. Journal of Speech Language and Hearing Research, 41(1), 18. 10.1044/jslhr.4101.18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storkel HL (2013). A corpus of consonant-vowel-consonant real words and nonwords: Comparison of phonotactic probability, neighborhood density, and consonant age of acquisition. Behavior Research Methods, 45(4), 1159–1167. 10.3758/s13428-012-0309-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storkel HL (2018). Implementing evidence-based practice: Selecting treatment words to boost phonological learning. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 49(3), 482–496. 10.1044/2017_LSHSS-17-0080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storkel HL (2019). Using developmental norms for speech sounds as a means of determining treatment eligibility in schools. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 4(1), 67–75. 10.1044/2018_pers-sig1-2018-0014 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Storkel HL, & Hoover JR (2010). An online calculator to compute phonotactic probability and neighborhood density on the basis of child corpora of spoken American English. Behavior Research Methods, 42(2), 497–506. 10.3758/BRM.42.2.497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugden E, Baker E, Munro N, Williams AL, & Trivette CM (2018). Service delivery and intervention intensity for phonology-based speech sound disorders. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 53(4), 718–734. 10.1111/1460-6984.12399 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Templin MC (1957). Certain language skills in children. University of Minnesota Press. 10.5749/j.ctttv2st [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Riper C, & Emerick LL (1984). Speech correction: An introduction to speech pathology and audiology (7th ed.). Prentice-Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Wren Y, Pagnamenta E, Peters TJ, Emond A, Northstone K, Miller LL, & Roulstone S (2021). Educational outcomes associated with persistent speech disorder. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 56(2), 299–312. 10.1111/1460-6984.12599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]