Abstract

The novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2 continues to cause death and disease throughout the world, underscoring the necessity of understanding the virus and host immune response. From the start of the pandemic, a prominent pattern of central nervous system (CNS) pathologies, including demyelination, has emerged, suggesting an underlying mechanism of viral mimicry to CNS proteins. We hypothesized that immunodominant epitopes of SARS-CoV-2 share homology with proteins associated with multiple sclerosis (MS). Using PEPMatch, a newly developed bioinformatics package which predicts peptide similarity within specific amino acid mismatching parameters consistent with published MHC binding capacity, we discovered that nucleocapsid protein shares significant overlap with 22 MS-associated proteins, including myelin proteolipid protein (PLP). Further computational evaluation demonstrated that this overlap may have critical implications for T cell responses in MS patients and is likely unique to SARS-CoV-2 among the major human coronaviruses. Our findings substantiate the hypothesis of viral molecular mimicry in the pathogenesis of MS and warrant further experimental exploration.

Subject terms: Computational models, Computational neuroscience, MHC

Introduction

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) is a novel pathogen that emerged in late 2019 as the causative agent of COVID-19. Due to the resulting global pandemic—there have been approximately 635 million documented cases worldwide1—as well as the novelty of the virus itself, much attention has been focused on post-viral sequalae reported in recovered patients. A significant proportion of these sequelae are related to aberrations in the central nervous system (CNS)2. In fact, 1 in 4 individuals with long-COVID recently reported persistent cognitive deficits and there is an emerging consensus on the significance of long-COVID as a public health burden3. Neurological manifestations have also been reported during acute SARS-CoV-2 infection, including encephalitis, encephalomyelitis, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder, myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein antibody-associated disease, and multiple sclerosis4. Taken together, these manifestations suggest a pathogenesis potentially involving demyelination, which may further suggest the centrality of an autoimmune process in both acute and post-infectious clinical presentations in some COVID-19 patients.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common autoimmune demyelinating disease in the United States and affects approximately 3 million people worldwide5. It has been widely suggested that the etiology of MS involves an initial infectious insult. For decades, it has been noted that the onset of first and recurring episodes of MS are often preceded by acute infections6–8. Importantly, studies investigating seasonal coronaviruses and SARS-CoV-2 have suggested the ability of these viruses to elicit cross-reactivity with viruses thought to play a role in the initial pathogenesis of MS9. In addition, other notable autoimmune diseases such as Guillain–Barre Syndrome, hypothesized to be driven in part by molecular mimicry, have been reported following SARS-CoV-2 infection10. We hypothesized that SARS-CoV-2 proteins share homology with CNS proteins, which could play a role in the physical manifestations of MS following acute SARS-CoV-2 infection.

Although the development of MS is likely a coalescence of the cellular and humoral adaptive immune arms, T cells have been implicated as being central drivers of disease manifestation in both the mouse model of MS (experimental autoimmune encephalitis, EAE) and humans11,12. Central to the theory of molecular mimicry is the degenerative nature of both T cells and MHC binding, in which multiple peptides can bind to the same MHC, and in turn multiple peptide:MHC combinations can be recognized by the same T cell Receptor (TCR)13,14. Several pathogenic proteins have been assessed for their homology to MS-associated antigens15,16, but no analyses to date have fully captured physiological parameters like MHC degeneracy and peptide length restrictions to provide a comprehensive picture of homology in the context of MHC presentation.

Here, we use PEPMatch17, a newly developed, bioinformatic homology-based package, to assess the potential for molecular mimicry between known immunodominant proteins from SARS-CoV-2 and MS-associated proteins in the context of a T-cell mediated response. Critically, PEPMatch has built-in parameters for both peptide length and mismatching rate, which more closely mimics the constraints imposed by MHC presentation of peptides to TCRs and thus the potential for molecular mimicry. We report that nucleocapsid protein from SARS-CoV-2 shares significant overlap with MS-associated proteins, including the canonical MS protein, myelin proteolipid protein (PLP). Our computational study substantiates the molecular mimicry hypothesis in the neurological sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection and lays the groundwork for future experimental and epidemiological studies investigating MS pathogenic etiologies.

Results

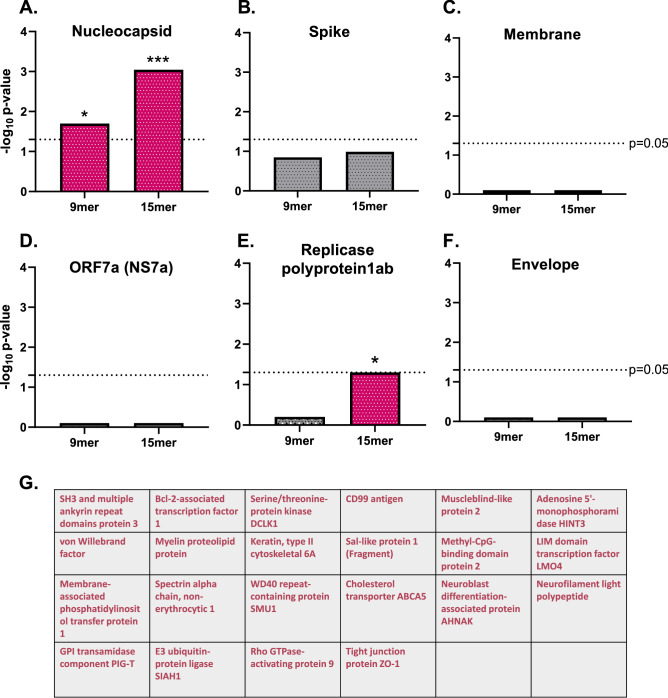

SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid exhibits significant homology with MS-associated proteins across both 9mer and 15mer peptide groups

We used PEPMatch17 to determine the sequence homology between immunodominant proteins from SARS-CoV-2 and MS-associated proteins, which were compiled using the Immune Epitope Database and Analysis Resource (IEDB) (http://www.iedb.org/) (Table 1). We tested both 9mer and 15mer segments to contextualize MHC I and MHC II presentation, respectively. These peptide lengths correspond to experimentally validated epitope lengths associated with CD8+ and CD4+ T cell recognition, respectively17. Intriguingly, nucleocapsid protein shared significant overlap with MS-associated proteins in both 9mer and 15mer groups (Fig. 1A) (see Methods for full details on background controls and statistical comparisons). Spike, membrane, NS7a, and envelope proteins from SARS-CoV-2 did not share significant overlap with the list of MS proteins above their sequence-shuffled controls, and replicase polyprotein 1ab had significantly elevated peptide matches above its sequence-shuffled control only in the 15mer group (Fig. 1B–F). Out of the 108 antigens on the list of MS-associated proteins used in this analysis, 22 proteins had sequences matching nucleocapsid across both 9mer and 15mer groups. Of note, the canonical MS-associated protein PLP shared homology with nucleocapsid from SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 1G).

Table 1.

List of proteins used in this analysis.

| UniProt IDs | Protein name | Gene names | Organism |

|---|---|---|---|

| Q07157 | Tight junction protein ZO-1 | TJP1 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q9Y6M0 | Testisin | PRSS21 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P63313 | Thymosin beta-10 | TMSB10 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q9Y617 | Phosphoserine aminotransferase | PSAT1 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q01082 | Spectrin beta chain, non-erythrocytic 1 | SPTBN1 SPTB2 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q6ZMD2 | Protein spinster homolog 3 | SPNS3 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q8IUQ4 | E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase SIAH1 | SIAH1 HUMSIAH | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| O94885 | SAM and SH3 domain-containing protein 1 | SASH1 KIAA0790 PEPE1 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P04275 | von Willebrand factor | VWF F8VWF | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q16864 | V-type proton ATPase subunit F | ATP6V1F ATP6S14 VATF | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| O43660 | Pleiotropic regulator 1 | PLRG1 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P20132 | L-serine dehydratase/L-threonine deaminase | SDS SDH | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q06190 | Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 2A regulatory subunit B'' subunit alpha | PPP2R3A PPP2R3 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q70J99 | Protein unc-13 homolog D | UNC13D | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q9NYF8 | Bcl-2-associated transcription factor 1 | BCLAF1 BTF KIAA0164 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P05023 | Sodium/potassium-transporting ATPase subunit alpha-1 | ATP1A1 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q6JQN1 | Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase family member 10 | ACAD10 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q8WWZ7 | Cholesterol transporter ABCA5 | ABCA5 KIAA1888 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q8N6D5 | Ankyrin repeat domain-containing protein 29 | ANKRD29 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q9BZR8 | Apoptosis facilitator Bcl-2-like protein 14 | BCL2L14 BCLG | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q9H0Q3 | FXYD domain-containing ion transport regulator 6 | FXYD6 UNQ521/PRO1056 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q9HC77 | Centromere protein J | CENPJ CPAP LAP LIP1 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P25024 | C-X-C chemokine receptor type 1 | CXCR1 CMKAR1 IL8RA | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P63151 | Serine/threonine-protein phosphatase 2A 55 kDa regulatory subunit B alpha isoform | PPP2R2A | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q14469 | Transcription factor HES-1 | HES1 BHLHB39 HL HRY | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q09666 | Neuroblast differentiation-associated protein AHNAK | AHNAK PM227 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q12860 | Contactin-1 | CNTN1 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P49771 | Fms-related tyrosine kinase 3 ligand | FLT3LG | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q9Y6R7 | IgGFc-binding protein | FCGBP | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P14209 | CD99 antigen | CD99 MIC2 MIC2X MIC2Y | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P04083 | Annexin A1 | ANXA1 ANX1 LPC1 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P0DP25 | Calmodulin-3 | CALM3 CALML2 CAM3 CAMC CAMIII | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P50995 | Annexin A11 | ANXA11 ANX11 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q7L5A8 | Fatty acid 2-hydroxylase | FA2H FAAH FAXDC1 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q9UBB5 | Methyl-CpG-binding domain protein 2 | MBD2 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q96KP4 | Cytosolic non-specific dipeptidase | CNDP2 CN2 CPGL HEL-S-13 PEPA | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| O15075 | Serine/threonine-protein kinase DCLK1 | DCLK1 DCAMKL1 DCDC3A KIAA0369 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q9NPB8 | Glycerophosphocholine phosphodiesterase GPCPD1 | GPCPD1 GDE5 KIAA1434 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P50502 | Hsc70-interacting protein | ST13 AAG2 FAM10A1 HIP SNC6 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P07099 | Epoxide hydrolase 1 | EPHX1 EPHX EPOX | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P61968 | LIM domain transcription factor LMO4 | LMO4 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q5QNW6 | Histone H2B type 2-F | H2BC18 HIST2H2BF | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P01344 | Insulin-like growth factor II | IGF2 PP1446 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| A4QPB2 | Low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 5-like protein | LRP5L | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P05783 | Keratin, type I cytoskeletal 18 | KRT18 CYK18 PIG46 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q9UBV8 | Peflin | PEF1 ABP32 UNQ1845/PRO3573 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q92903 | Phosphatidate cytidylyltransferase 1 | CDS1 CDS | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P49327 | Fatty acid synthase | FASN FAS | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P20592 | Interferon-induced GTP-binding protein Mx2 | MX2 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P60201 | Myelin proteolipid protein | PLP1 PLP | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P60709 | Actin, cytoplasmic 1 | ACTB | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q14938 | Nuclear factor 1 X-type | NFIX | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q9H1E3 | Nuclear ubiquitous casein and cyclin-dependent kinase substrate 1 | NUCKS1 NUCKS JC7 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P20292 | Arachidonate 5-lipoxygenase-activating protein | ALOX5AP FLAP | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q6ZMW3 | Echinoderm microtubule-associated protein-like 6 | EML6 EML5L | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P09471 | Guanine nucleotide-binding protein G(o) subunit alpha | GNAO1 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q13349 | Integrin alpha-D | ITGAD | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q13491 | Neuronal membrane glycoprotein M6-b (M6b) | GPM6B M6B | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q5VZF2 | Muscleblind-like protein 2 | MBNL2 MBLL MBLL39 MLP1 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| O95897 | Noelin-2 | OLFM2 NOE2 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| O00562 | Membrane-associated phosphatidylinositol transfer protein 1 | PITPNM1 DRES9 NIR2 PITPNM | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q9NQE9 | Adenosine 5'-monophosphoramidase HINT3 | HINT3 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P02686 | Myelin basic protein (P02868) | MBP | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P55082 | Microfibril-associated glycoprotein 3 | MFAP3 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P07196 | Neurofilament light polypeptide | NEFL NF68 NFL | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q8IXS6 | Paralemmin-2 | PALM2 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q6NY19 | KN motif and ankyrin repeat domain-containing protein 3 | KANK3 ANKRD47 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P20916 | Myelin-associated glycoprotein | MAG GMA | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| O95298 | NADH dehydrogenase [ubiquinone] 1 subunit C2 | NDUFC2 HLC1 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P68871 | Hemoglobin subunit beta | HBB | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q9H2D1 | Mitochondrial folate transporter/carrier | SLC25A32 MFT MFTC | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q13813 | Spectrin alpha chain, non-erythrocytic 1 | SPTAN1 NEAS SPTA2 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q6UWS5 | Protein PET117 homolog, mitochondrial | PET117 UNQ607/PRO1194 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q8IXJ6 | NAD-dependent protein deacetylase sirtuin-2 | SIRT2 SIR2L SIR2L2 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P0DTU4 | T cell receptor beta chain MC.7.G5 | TRB | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P37837 | Transaldolase | TALDO1 TAL TALDO TALDOR | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P04271 | Protein S100-B | S100B | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| O00193 | Small acidic protein | SMAP C11orf58 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q2TAY7 | WD40 repeat-containing protein SMU1 | SMU1 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P62273 | 40S ribosomal protein S29 | RPS29 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P02538 | Keratin, type II cytoskeletal 6A | KRT6A K6A KRT6D | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P35579 | Myosin-9 | MYH9 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P16949 | Stathmin | STMN1 C1orf215 LAP18 OP18 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q7KZF4 | Staphylococcal nuclease domain-containing protein 1 | SND1 TDRD11 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q86YJ6 | Threonine synthase-like 2 | THNSL2 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q15437 | Protein transport protein Sec23B | SEC23B | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| E7EV99 | Alpha-adducin | ADD1 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| X6RJP6 | Transgelin-2 (Fragment) | TAGLN2 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| A0A0A0MS51 | Actin-depolymerizing factor | GSN | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| C9J9K3 | 40S ribosomal protein SA (Fragment) | RPSA | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| J3QQK6 | Myelin basic protein (J3QQK6) | MBP | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| H3BQR2 | Cytosolic Fe-S cluster assembly factor NUBP2 | NUBP2 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| B5MCX3 | Septin-2 | SEPTIN2 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| B7WPG3 | Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein L-like | HNRNPLL | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| F5H5N1 | Complex I-20kD | NDUFS7 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| E9PEF9 | Aldo–keto reductase family 1 member B1 | AKR1B1 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| A0A0U1RQS4 | SH3 and multiple ankyrin repeat domains protein 3 | SHANK3 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| H3BSM9 | Sal-like protein 1 (Fragment) | SALL1 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q6FGG4 | Complex I-B9 | NDUFA3 hCG_20947 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| J3KPH8 | Histone deacetylase | HDAC7 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| R4GN15 | Rho GTPase-activating protein 9 | ARHGAP9 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| A0A1W2PP57 | GPI transamidase component PIG-T | PIGT | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| C9JVQ0 | Small nuclear ribonucleoprotein G | SNRPG | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| H0Y4W2 | Transformation/transcription domain-associated protein | TRRAP | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| X1WI28 | 60S ribosomal protein L10 (Fragment) | RPL10 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| E9PB61 | THO complex subunit 4 | ALYREF | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| J3KN36 | Nodal modulator 3 | NOMO3 | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| Q16653 | Myelin oligodendrocyte-glycoprotein | MOG | Homo sapiens (Human) |

| P0DTC2 | Spike glycoprotein | S | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| A0A6C0T6Z7 | Nucleoprotein (Nucleocapsid) | N | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| P0DTC5 | Membrane protein | M | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| P15423 | Spike glycoprotein | S | Human coronavirus 229E |

| P15130 | Nucleoprotein (Nucleocapsid) | N | Human coronavirus 229E |

| P15422 | Membrane protein | M | Human coronavirus 229E |

| Q6Q1S2 | Spike glycoprotein | S | Human coronavirus NL63 |

| Q6Q1R8 | Nucleoprotein (Nucleocapsid) | N | Human coronavirus NL63 |

| Q6Q1R9 | Membrane protein | M | Human coronavirus NL63 |

| P36334 | Spike glycoprotein | S | Human coronavirus OC43 |

| P33469 | Nucleoprotein (Nucleocapsid) | N | Human coronavirus OC43 |

| Q01455 | Membrane protein | M | Human coronavirus OC43 |

| Q5MQD0 | Spike glycoprotein | S | Human coronavirus HKU1 (isolate N1) |

| Q5MQC6 | Nucleoprotein (Nucleocapsid) | N | Human coronavirus HKU1 (isolate N1) |

| Q5MQC7 | Membrane protein | M | Human coronavirus HKU1 (isolate N1) |

| P03211 | Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 1 | EBNA1 | Epstein-Barr virus (strain B95-8) |

| P12978 | Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 2 | EBNA2 | Epstein-Barr virus (strain B95-8) |

| P12977 | Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 3 | EBNA3 | Epstein-Barr virus (strain B95-8) |

| P03203 | Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 4 | EBNA4 | Epstein-Barr virus (strain B95-8) |

| Q8AZK7 | Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen leader protein | EBNA-LP | Epstein-Barr virus (strain B95-8) |

| P03204 | Epstein-Barr nuclear antigen 6 | EBNA6 | Epstein-Barr virus (strain B95-8) |

| P03230 | Latent membrane protein 1 | LMP1 | Epstein-Barr virus (strain B95-8) |

| P13285 | Latent membrane protein 2 | LMP2 | Epstein-Barr virus (strain B95-8) |

| P06725 | 65 kDa phosphoprotein | UL83 | Human cytomegalovirus (strain AD169) |

| P13202 | Immediate early protein IE1 | UL123 | Human cytomegalovirus (strain AD169) |

| P06473 | Envelope glycoprotein B | gB | Human cytomegalovirus (strain AD169) |

| P09713 | Unique short US2 glycoprotein | US2 | Human cytomegalovirus (strain AD169) |

| P13200 | Cytoplasmic envelopment protein 3 | UL99 | Human cytomegalovirus (strain AD169) |

| P12824 | Envelope glycoprotein H | gH | Human cytomegalovirus (strain AD169) |

| P09712 | Membrane glycoprotein US3 | US3 | Human cytomegalovirus (strain AD169) |

| P14334 | Unique short US6 glycoprotein | US6 | Human cytomegalovirus (strain AD169) |

| P08560 | Glycoprotein UL18 | H301 | Human cytomegalovirus (strain AD169) |

| P0DTC7 | ORF7a protein | 7a | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| P0DTD1 | Replicase polyprotein 1ab | Rep | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

| P0DTC4 | Envelope small membrane protein | E | Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 |

Briefly, MS-associated proteins were compiled using the IEDB (see Methods for full methodology on protein selection). This was to ensure that proteins utilized in this analysis have been experimentally associated with MS in the literature. SARS-CoV-2, seasonal coronavirus, EBV, and CMV immunodominant proteins are also listed.

Figure 1.

Nucleocapsid protein shares significant homology with MS-associated proteins. (A) PEPMatch was used to determine the overlap between nucleocapsid protein from SARS-CoV-2 and MS-associated proteins, which were determined using an IEDB query. For comparison, 30 iterations of shuffled-sequence nucleocapsid protein were run through the analysis with the same parameters as the intact nucleocapsid sequence, whose average was then compared to MS-associated proteins. Fisher’s exact or Chi square tests were run on both the 9mer and the 15mer peptides, with up to 2 mismatches for the 9mer peptides and up to 7 mismatches for the 15mer peptides. (B–F) The same analysis was run as in (A) using the specified proteins labeled above each graph from SARS-CoV-2. (G) Shown are the proteins whose peptides significantly overlapped with nucleocapsid across both the 9mer and 15mer groups.

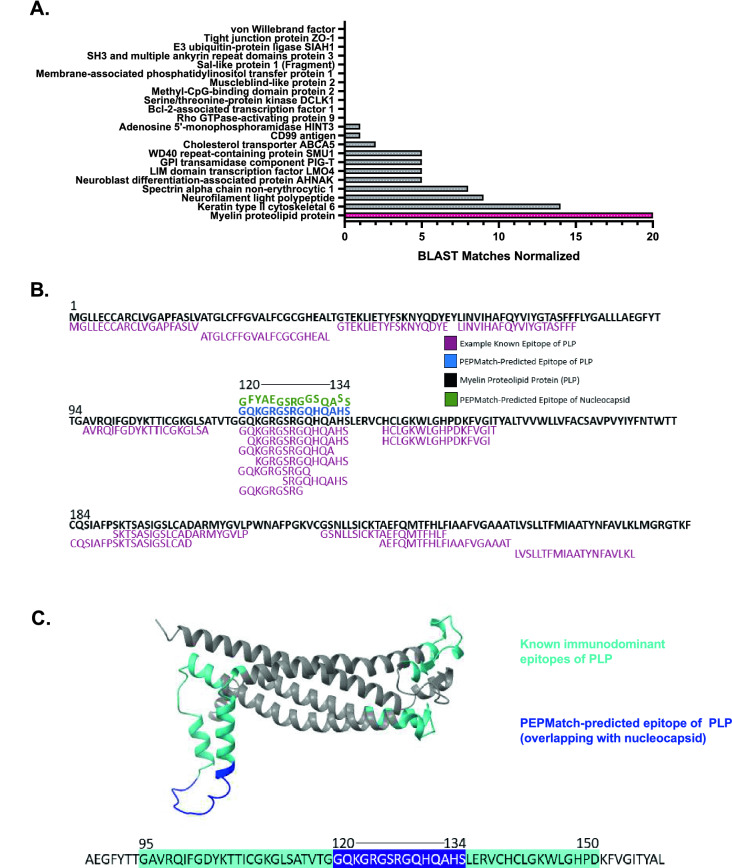

PEPMatch-predicted PLP epitope shares homology with experimentally validated MS-associated peptides and is in a region known to elicit T-cell responses in MS patients

To contextualize the above findings, we investigated whether epitopes returned from PEPMatch had been documented in the literature. We found that of all the proteins returned from the PEPMatch analysis, PLP had the highest number of BLASTp-verified homologous sequences that have been experimentally validated and curated on the IEDB (Fig. 2A,B). PLP has been documented to contain epitopes recognized by T cells from MS patients across numerous studies18,19. In one study, T cell lines derived from MS patients and activated with PLP showed the strongest reactivity against regions 40–60, 95–117, 117–150, and 185–206 out of all 9 regions of PLP tested20. The authors concluded from this study that these regions were largely responsible for eliciting strong T cell responses in MS patients. We found that the PLP peptides returned from PEPMatch fell within one of these immunodominant regions (Fig. 2C). Overall, these results provide a computational basis for the potential of SARS-CoV-2 to initiate T-cell-driven molecular mimicry through specific MS-associated proteins, including PLP.

Figure 2.

PEPMatch-predicted epitope of myelin proteolipid protein (PLP) has high similarity to experimentally validated epitopes and is in a region associated with strong T cell responses in MS patients. (A) PEPMatch-predicted peptides sharing homology with nucleocapsid were assessed for overlap with known, experimentally validated epitopes on the Immune Epitope Databases (IEDB). All known epitopes for each protein were run in a BLASTp query against the peptide(s) returned from PEPMatch. The number of homology “hits” were quantified and divided by the number of input PEPMatch peptides for that protein for normalization. (B) The PEPMatch-predicted epitope of PLP matching nucleocapsid (blue) was aligned with the full-length sequence of PLP (black) and the nucleocapsid peptide to which it matches (green) alongside examples of known epitopes of PLP identified in the literature and available on the IEDB (berry). (C) Predicted PLP structure was highlighted with known immunodominant areas previously identified as eliciting strong T cell responses preferentially in MS patients20 (cyan) against the PEPMatch-predicted epitope sharing homology with nucleocapsid (dark blue).

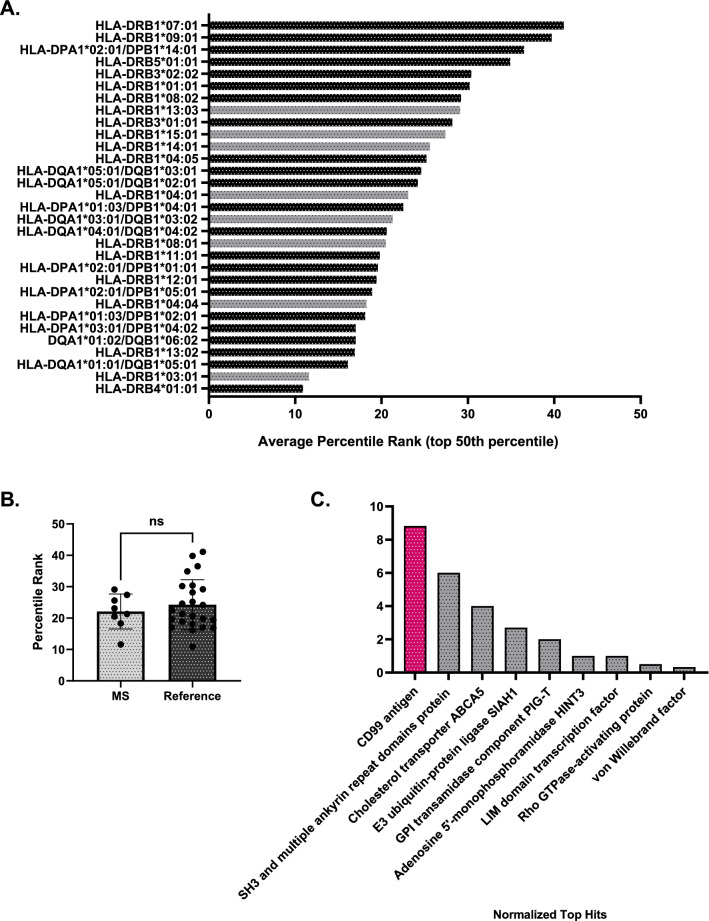

MHC-binding prediction reveals other proteins of interest which may facilitate molecular mimicry beyond PLP

Given that molecular mimicry is likely facilitated not only by sequence similarity but also by HLA haplotype6,21, we next investigated whether MS-associated alleles22–24 would be predicted to bind to the nucleocapsid peptides returned from the PEPMatch analysis. We compared the binding propensity of MS-associated alleles to a set of alleles which represent approximately 99% of the population worldwide to contextualize the analysis25. We analyzed the top 50th percentile of binding predictions returned from the algorithm in order to focus on physiologically relevant binding predictions while retaining maximum information on the alleles26. We found that while some MS-associated alleles demonstrated high average binding capacities (represented by low average percentile rank, Fig. 3A), including HLA-DRB1*03:01, HLA-DRB1*04:04, and HLA-DRB1*08:01, there was no significant difference in average binding predictions from MS-associated alleles in comparison to the reference set of alleles (Fig. 3B). We next asked whether certain proteins matching the nucleocapsid peptides from the original PEPMatch analysis were enriched amongst the top peptide:allele binding predictions. Inspection of these peptide:allele combinations that scored a 10th percentile rank or less across all alleles revealed unique proteins enriched for predicted MHC binding (Fig. 3C). Although our focus has largely centered on the canonical MS protein PLP, this analysis highlights other potential proteins returned from the PEPMatch analysis that may trigger autoimmunity across a wide variety of HLA-haplotyped individuals, including CD99 (Fig. 3C).

Figure 3.

MHC-binding prediction provides insight on proteins which may engage in molecular mimicry beyond PLP. (A) MHC-binding prediction tool by the IEDB was used to determine the binding of nucleocapsid peptide hits from the PEPMatch analysis and MS-associated alleles (gray) versus a reference set of alleles (black)25. Shown are the top 50th percentile of average binding predictions of all 15mer nucleocapsid peptides from the original analysis and their respective HLA alleles that are predicted to bind. The lower the percentile rank, the stronger the predicted binding between the allele and the set of peptides run in the analysis. (B) Data from (A) grouped by allele classification. (C) Peptide:allele combinations with a percentile rank of 10th or less were collected and assessed for their respective MS-associated protein matches from the original PEPMatch analysis; plotted are the proteins that were returned from this analysis that are normalized to their respective number of peptides input.

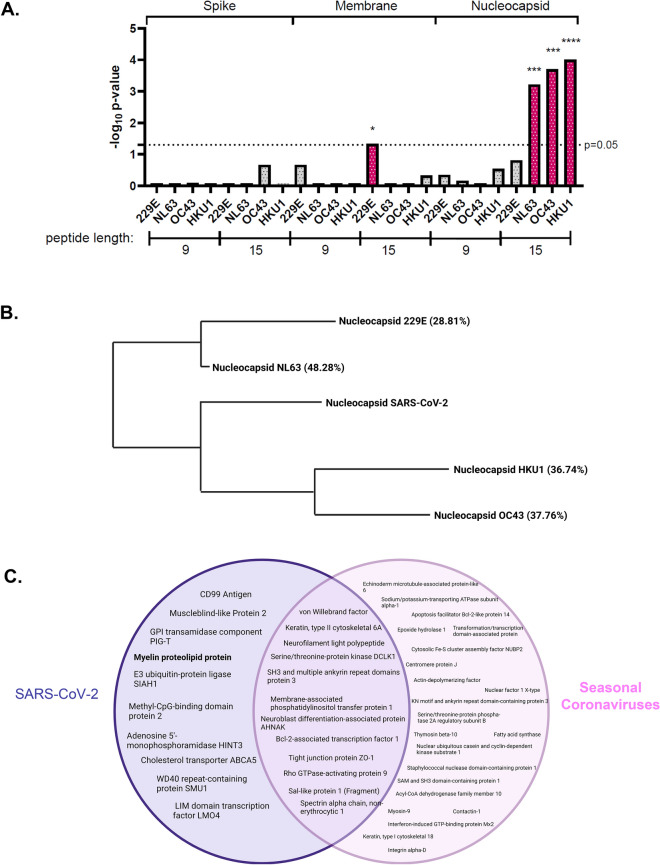

Seasonal coronaviruses share significant homology with MS-associated proteins but do not overlap with PLP

Seasonal coronaviruses have been implicated in the development of MS27–29. To determine whether the above findings were unique to SARS-CoV-2, we tested whether nucleocapsid, spike, or membrane proteins from seasonal coronaviruses 229E, NL63, OC43, and HKU1 shared significant homology with MS-associated proteins. We found that the nucleocapsid protein from 3 out of the 4 seasonal coronaviruses tested shared significant homology with MS-associated proteins, but only in the 15mer groups (Fig. 4A); due to the stricter matching parameters of the 9mer group, this suggests a higher degree of peptide similarity between SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid and MS-associated proteins (Fig. 1A). Nucleocapsid proteins of these 3 seasonal coronaviruses also share the highest percent identity to SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid as determined by BLASTp (Fig. 4B). Of note, while the coronaviruses all had some shared PEPMatch protein “hits”, only PLP significantly overlapped with the nucleocapsid of SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 4C).

Figure 4.

Nucleocapsid of seasonal coronaviruses show homology with MS-associated proteins, but only SARS-CoV-2 overlaps with PLP. (A) PEPMatch homology analysis was conducted as in Fig. 1 using spike, membrane, and nucleocapsid proteins from seasonal coronaviruses 229E, NL63, OC43, and HKU1. (B) BLASTp analysis was conducted to determine overall percent identity of seasonal coronavirus nucleocapsid proteins against SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid. Shown is a representation of the BLASTp homology output, with percent identity to SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid in parentheses. (C) PEPMatch-predicted proteins sharing homology with SARS-CoV-2 (left) and seasonal coronaviruses (right) were assessed for overlap using a Venn diagram.

Discussion

Since the beginning of the pandemic, SARS-CoV-2 has been associated with CNS sequelae with manifestations ranging from memory loss and attention deficits to demyelination3,4,30,31. Although viral molecular mimicry has been a long-standing hypothesis regarding the triggering of initial and recurrent episodes of MS demyelination7, no bioinformatic approaches had been created which consider physiological parameters necessary for fully understanding MHC presentation capacity. In this analysis, we demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 may be associated with the development of MS using a new computational tool developed by the IEDB team that includes more robust physiological parameters in its assessment for homology.

SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid, spike, and membrane proteins have been widely demonstrated to elicit strong immune responses32. Indeed, it was recently found that these 3 proteins were among the 9 viral proteins making up 83% of CD4+ T cell responses, and among the 8 accounting for 81% of CD8+ T cell responses in COVID-convalescent patients33,34. In addition, NS7a35, replicase polyprotein1ab36, and envelope37 proteins have all been implicated in driving immune responses in individuals recovering from SARS-CoV-2. We asked whether any of these proteins shared significant homology with MS-associated neuro-antigens—an observation which would fortify the proposed case for molecular mimicry in the development of MS following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Interestingly, both the 9mer and 15mer groups (representing MHC I and II, respectively) from nucleocapsid showed significant sequence overlap with MS-associated proteins (Fig. 1A), in contrast to most of the other proteins tested in our analysis with the exception of replicase polyprotein 1ab, which showed significance only in the 15mer group (Fig. 1E). Given the strict parameters for amino acid homology for the 9mer group—protein sequences had to exactly match a minimum of 78% of the time—a strong overlap of nucleocapsid and MS-associated proteins highlights the potential for SARS-CoV-2-mediated molecular mimicry across both classes of MHC.

Myelin proteolipid protein (PLP) has been implicated in the development of MS across a multitude of studies20,38–40. In humans, the development of MS following Rubella virus infection was demonstrated to be linked to the high relative similarity score of E2 protein to PLP16,41, demonstrating the potential for sequence overlap leading to the induction of demyelinating disease. More recently, França et al. discovered that the NS5 epitope of Zika virus shared 83% sequence homology with PLP, implicating NS5 as a likely candidate for driving the development of MS and possibly other CNS inflammatory demyelinating disorders42. In our own study using PEPMatch, we found that an epitope from PLP shared significant homology with a nucleocapsid peptide from SARS-CoV-2 (Fig. 1G). Importantly, the PLP epitope that overlaps with nucleocapsid is associated with a high number of experimentally validated epitopes curated from the literature (Fig. 2A,B), providing evidence for the potential for SARS-CoV-2-driven molecular mimicry. Among the numerous studies that have investigated the autoantigenicity of specific epitopes of PLP in the context of MS-development18,19, certain epitopes have been specifically associated with eliciting strong T cell responses in MS patients20. The epitope returned from PEPMatch in our study, 120–134, is encompassed within an epitope associated with strong T cell responses in DR15*01-positive MS subjects20 (Fig. 2C). Collectively, this data substantiates the hypothesis that SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid may be providing the basis for molecular mimicry preceding the development of MS in susceptible individuals.

In the words of Wekerle, “Molecular mimicry thus goes well beyond the simple structural resemblance of two individual peptides. It also embraces the peptide-presenting MHC…”7. We investigated whether nucleocapsid peptides returned from PEPMatch would be predicted to bind preferentially to MS-associated class II HLA alleles, of which more has been published in relation to MS susceptibility than for class I HLA. Using the top 50th percentile of binding predictions, the average percentile rank of all peptide:allele combinations grouped by allele demonstrated no significant pattern of binding enrichment among the MS-associated alleles (Fig. 3B). Several salient considerations must be acknowledged when interpretating these data, however. Importantly, weakly binding peptide epitopes from myelin basic protein (MBP) have been associated with eliciting strong autoimmune responses in EAE mouse models43, suggesting that predicting the binding propensity of peptide:allele combinations may be more complex than fully accounted for by this machine learning algorithm. This analysis also is limited in scope by the total number of HLA alleles assessed. We analyzed 31 alleles; there are over 33,000 allele and haplotype entries on the IPD/IMGT-HLA database44. However, our results suggest that certain HLA alleles not previously associated with MS development may increase susceptibility to CNS-related sequelae, including HLA-DRB4*01:01, though this speculation warrants further investigation.

Top ranking MS-associated alleles from our analysis, including HLA-DRB1*03:01, have not only been associated with the development of MS, but also the development of other autoimmune disorders. HLA-DRB1*03:01 has been associated with autoimmune hepatitis45, autoimmune encephalitis46, neuromyelitis optica47, and autoimmune Addison’s disease (AAD)48. AAD has been reported in the literature following acute COVID-19 infection49–51, suggesting that this allele may predispose individuals of this haplotype to other acute autoimmune-related manifestations of SARS-CoV-2 beyond CNS pathologies. In conclusion, numerous studies have been published which link specific HLA haplotypes with susceptibility of severe COVID outcomes52–54; however, no studies exist to date which explore the haplotypes of individuals with rare CNS sequelae following SARS-CoV-2 infection. Future experimental investigation should broaden the scope of disease manifestations to better understand the potential link between HLA haplotype and SARS-CoV-2 neuropathogenesis.

To further explore the relationship between allele binding predictions and CNS manifestations, we gathered the peptides of percentile rank 10 or lower26 and tallied the original proteins from which the peptides originated. We found a considerable enrichment of CD99 peptides among the top allele binding predictions (Fig. 3C). CD99 is a cell surface protein expressed by a wide number of tissues and organ systems, including lymphocytes, and is critical for cellular adhesion, migration, and diapedesis55. Recently, CD99 was implicated in exacerbated COVID-19-associated kidney injury56. Elution of CD99 peptides in the urine separated groups of patients with mild versus severe kidney pathology; in addition, CD99+ lymphocytes were found in significantly lower percentages in patients with severe outcomes. The authors speculated that aberrant autoimmune responses directed against CD99 may be promoting the exacerbation of kidney injury, and that this reduction of CD99 overall could indicate a loss of endothelial integrity56. Recently, Domizio and colleagues found that acute respiratory injury following SARS-CoV-2 infection is in part due to lung endothelial damage, which they speculated translated to other organ systems as well57. Neuropathogenesis following SARS-CoV-2 infection has been noted for distinct pathophysiological patterns, including loss of blood–brain barrier (BBB) integrity58, which is structurally maintained largely through endothelial cells59. Integral to these observations is the finding that Keratin Type II Cytoskeleton 6A (a protein recovered in our original PEPMatch analysis, Fig. 1G) was also found to be dysregulated in patients with severe kidney injury56. This keratin protein has been associated with wound healing, in which loss of this protein led to profound inabilities of mice to undergo normal wound healing processes60. The peptides identified from PEPMatch (Fig. 1G), and more specifically those predicted to be bound and presented on MHC (Fig. 3C) warrant further experimental investigation, as they collectively suggest a mechanism by which molecular mimicry initiated by SARS-CoV-2 infection could lead to the inappropriate targeting of proteins involved in a range of biological processes necessary for a multitude of organ systems, culminating in severe neurological and other pathological outcomes.

Molecular mimicry has been explored as a mechanism for triggering MS for decades, and several viral and bacterial pathogens have been associated with MS development61. The most strongly linked etiological agent of MS is Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), in which multiple recent studies have strongly implicated the development of MS with EBV infection62,63. In our own hands using PEPMatch, we were able to demonstrate that a larger proportion of EBV proteins share similarity with MS-associated proteins than its virologic cousin, cytomegalovirus (CMV), aligning with current views on MS etiology and substantiating the practicality and utility of PEPMatch as a new resource (Supplemental Fig. 1). Seasonal coronaviruses have also been implicated in the pathogenesis of MS using a range of bioinformatic and clinical approaches27–29. Primary T cell clones isolated from MS patients activated with HCoV-229E and HCoV-OC43 proteins cross-reacted with myelin basic protein (MBP) and PLP, highlighting the propensity for viral molecular mimicry involving seasonal coronaviruses29. In our study, we found that nucleocapsid protein from 3 out of the 4 major seasonal coronaviruses showed significant sequence overlap with MS-associated proteins (Fig. 4A); however, this effect was only found in the 15mer group, whose threshold for peptide sequence overlap is around 50%17; this indicates a greater percentage of exact sequence matching and overall homology of SARS-CoV-2 nucleocapsid to MS proteins. In addition, we found that no myelin proteins shared homology with any coronaviruses except for PLP and SARS-CoV-2. Discussion has arisen querying whether the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic will herald an increase in MS incidence64. Our results provide a computational basis for this hypothesis, which should be further investigated using epidemiological approaches.

Here, we utilized a new homology-based package called PEPMatch to determine the sequence overlap between immunodominant proteins from SARS-CoV-2 and proteins associated with MS. We found that nucleocapsid significantly overlapped with MS-associated proteins, including PLP. Our work suggests that a variety of proteins may be involved in triggering autoimmunity associated with MS pathogenesis in certain individuals. We chose to focus our analysis on understanding T-cell-driven molecular mimicry, though the creation and maintenance of autoantibodies has been strongly implicated in both MS and COVID-19 severity38,65. Recent reports have shown that nucleocapsid is critical in driving humoral immunity in both SARS-CoV66 and SARS-CoV-267. Future integrated experimental and computational efforts should focus on understanding the full breadth of autoimmunity following SARS-CoV-2 infection, including the involvement of other organ systems and both adaptive immune arms, for a more comprehensive understanding of pathological sequelae of SARS-CoV-2.

Methods

Protein compilation

MS-associated antigens were compiled using the Immune Epitope Database and Analysis Resource (http://www.iedb.org/). The search included the following parameters: “Organism: Homo Sapiens”, “Include Positive Assays”, “No B Cell Assays”, “Disease Data: Multiple Sclerosis (DOID:2377)”, and “MHC Restriction Type: Class I” (class I restriction was added to ensure that many proteins associated with both class I and class II were included in the analysis, as the vast majority of the 1200 + proteins discovered without filtering were associated only with class II). Finally, proteins were added which have been associated strongly with MS in the literature that did not originally appear in the IEDB filtering68. This list was trimmed down to proteins which had updated UniProt IDs, leading to the list of 108 MS-associated antigens used in this analysis. This list, with UniProt IDs, can be found in Table 1. Complete list of query proteins in this analysis, including proteins from SARS-CoV-2 and seasonal coronaviruses, as well as EBV and CMV proteins, can also be found in Table 1.

Homology assessment

Homology between SARS-CoV-2 immunodominant proteins and the list of MS-associated proteins was conducted primarily using PEPMatch and BLASTp. All code utilized in this analysis can be found on GitHub using the following link: https://github.com/mad-scientist-in-training/PEPMatch_SARS-CoV-2_MS.

PEPMatch

PEPMatch is a homology-based algorithm developed by Daniel Marrama17 and is freely available to use on GitHub: https://github.com/IEDB/PEPMatch. PEPMatch was utilized to preprocess the list of MS-associated proteins and query proteins (found in Table 1). Custom python scripts were created to utilize PEPMatch and perform all other processing necessary to run the package (see Homology Assessment for link to GitHub page). Parameters were set to preprocess all data sets separately into 9mer peptides and 15mer peptides, with 2 and 7 mismatches respectively. PEPMatch output for all significant tests is available in Supplemental Table 1.

BLASTp

To determine homology between PEPMatch-predicted peptides overlapping with nucleocapsid and experimentally validated epitopes (Fig. 2A), a list of epitopes for each protein was compiled using the IEDB. The search parameters included “Antigen: Protein_of_interest (Homo sapiens (human))”, “Include Positive Assays”, and “Host: Homo sapiens (human)”. Standard Protein BLAST (BLASTp) was used to determine the homology between all PEPMatch-predicted epitopes and experimentally validated peptides for each protein. To normalize, the total number of homology “hits” returned from BLASTp was divided by the number of peptides predicted from PEPMatch for each protein.

Example BLASTp analysis: PLP.

| Peptides returned from PEPMatch (overlapping with nucleocapsid): | 1 |

| Epitopes returned from IEDB query: | 150 |

| Number of Homology “hits” from BLASTp analysis | 20 |

| Normalized total hits | 20/1 = 20 |

BLASTp was also used to determine the percent identity between nucleocapsid from SARS-CoV-2 and seasonal coronaviruses using the standard, recommended parameters.

Statistics

For statistical comparisons, each query protein (spike, nucleocapsid, and membrane, NS7a, replicase polyprotein1ab, and envelope) was separately processed to provide “background” number of hits against MS-associated proteins. Specifically, custom python scripts (found on the GitHub page) were created to shuffle the amino acid sequence of each query protein, which were run to determine the number of matches with MS-associated proteins as background matching signal. Duplicate matches (for example, if identical peptides from 2 separate MS-associated proteins matched a SARS-CoV-2-derived peptide) were removed prior to statistical testing. For each query protein tested, 30 iterations of unique shuffled comparisons were run, which were then averaged and used in a Fisher’s exact or Chi-square test for statistical comparison. All analyses were run conservatively with two-tailed parameters; however, if the number of random matches exceeded the number of matches of the intact peptide, the p value was assumed to be 1. The following is an example of the statistics utilized for each protein in this analysis:

Spike, SARS-CoV-2

| 9mer peptides | Match in MS proteins | No match in MS proteins | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intact Peptides | 12 | 1253 | 1265 |

| Shuffle Peptides (avg) | 5 | 1260 | 1265 |

p = 0.1421 (− log10 transform: 0.847).

| 15mer peptides | Match in MS Proteins | No Match in MS Proteins | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intact Peptides | 66 | 1193 | 1259 |

| Shuffle Peptides (avg) | 48 | 1211 | 1259 |

p = 0.1028 (− log10 transform: 0.988).

Statistical analyses (as above) for all comparisons in this manuscript can be found in Supplemental Table 2.

3D structure of PLP

Structural visualization of myelin proteolipid protein (PLP) was conducted using AlphaFold69 and ChimeraX70,71. Specifically, AlphaFold-simulated structure of PLP (ID: P60201) was loaded into ChimeraX for manipulation and visualization. Protein regions of PLP identified to be immunodominant, specifically regions 40–60, 95–117, 117–150, and 185–20620, were highlighted and colored for accentuation. The sequence of PLP used throughout the analysis can be found on UniProt (https://www.uniprot.org/).

Allele assessment

The MHC binding prediction machine learning algorithm from the IEDB was used to determine whether MS-associated alleles were predicted to preferentially bind and present nucleocapsid peptides in comparison to a reference set of alleles. MS-associated alleles were curated from the literature22–24 and used in comparison to an allele set from the IEDB that covers 99% of the population25. Nucleocapsid peptide “hits” from PEPMatch were used in the query against the total set of alleles (MS and reference) using the IEDB recommended 2.22 standard parameter. As most binding predictions were skewed heavily towards high percentile ranks, the top 50% percentile of all matching predictions were focused on to capture information for all alleles input while also providing physiologically relevant binding information. In Fig. 3C, the nucleocapsid peptide-MHC binding predictions of percentile rank 10 or less26 were cross-referenced with the original PEPMatch output to determine the homologous MS-associated proteins, and the frequency of peptide matches were tabulated and graphed.

Graphics

Graphics in this article were created using Biorender (https://biorender.com/).

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

We thank Avindra Nath, Thomas Esch, Daniel Rotrosen, Charles Hackett, Alison Deckhut-Augustine, and members of the Division of Allergy, Immunology, and Transplantation (DAIT) at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) for discussions about this project. In addition, we acknowledge Daniel Marrama, Bjoern Peters, Alessandro Sette, and those at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology for creating PEPMatch and providing expert advice and support during project development. This research was supported in part by an appointment to the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) Emerging Leaders in Data Science Research Participation Program. This program is administered by the Oak Ridge Institute for Science and Education through an interagency agreement between the U.S. Department of Energy and the National Institutes of Health.

Author contributions

C.M.L. and J.J.B. devised the main intellectual concepts of this project. C.M.L. ran the experiments, including data manipulation and creation of code facilitating the deployment of PEPMatch and other algorithms used in this study. C.M.L. wrote, while J.J.B. revised and edited, the manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Data availability

The authors declare that all data in support of the main findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files. All other data (including raw data generated in the supplemental findings) are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Code availability

All code generated for this project is available on GitHub at the following repository: https://github.com/mad-scientist-in-training/PEPMatch_SARS-CoV-2_MS.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-022-27348-8.

References

- 1.Coronavirus disease (COVID-19)—World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019.

- 2.Aghagoli G, et al. Neurological involvement in COVID-19 and potential mechanisms: A review. Neurocrit. Care. 2021;34:1062–1071. doi: 10.1007/s12028-020-01049-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nasserie T, Hittle M, Goodman SN. Assessment of the frequency and variety of persistent symptoms among patients with COVID-19: A Systematic review. JAMA Netw. Open. 2021;4:e2111417. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.11417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ismail II, Salama S. Association of CNS demyelination and COVID-19 infection: an updated systematic review. J. Neurol. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00415-021-10752-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Number of people with MS | Atlas of MS. https://www.atlasofms.org/map/global/epidemiology/number-of-people-with-ms.

- 6.Liblau R, Gautam AM. HLA, molecular mimicry and multiple sclerosis. Rev. Immunogenet. 2000;2:95–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wekerle H, Hohlfeld R. Molecular mimicry in multiple sclerosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;349:185–186. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcibr035136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chastain EML, Miller SD. Molecular mimicry as an inducing trigger for CNS autoimmune demyelinating disease. Immunol. Rev. 2012;245:227–238. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01076.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dykema, A. G. et al. Functional characterization of CD4+ T cell receptors crossreactive for SARS-CoV-2 and endemic coronaviruses. J. Clin. Investig.131, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Toscano G, et al. Guillain–Barré syndrome associated with SARS-CoV-2. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382:2574–2576. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2009191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olson JK, Eagar TN, Miller SD. Functional activation of myelin-specific T cells by virus-induced molecular mimicry. J. Immunol. 2002;169:2719–2726. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.5.2719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Krishnamoorthy G, Wekerle H. EAE: An immunologist’s magic eye. Eur. J. Immunol. 2009;39:2031–2035. doi: 10.1002/eji.200939568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Joshi SK, Suresh PR, Chauhan VS. Flexibility in MHC and TCR recognition: Degenerate specificity at the T cell level in the recognition of promiscuous th epitopes exhibiting no primary sequence homology. J. Immunol. 2001;166:6693–6703. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.11.6693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lang HLE, et al. A functional and structural basis for TCR cross-reactivity in multiple sclerosis. Nat. Immunol. 2002;3:940–943. doi: 10.1038/ni835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujinami RS, Oldstone MB, Wroblewska Z, Frankel ME, Koprowski H. Molecular mimicry in virus infection: crossreaction of measles virus phosphoprotein or of herpes simplex virus protein with human intermediate filaments. PNAS. 1983;80:2346–2350. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.8.2346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nath A, Wolinsky JS. Antibody response to rubella virus structural proteins in multiple sclerosis. Ann. Neurol. 1990;27:533–536. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marrama, D., Mahita, J., Sette, A. & Peters, B. Lack of evidence of significant homology of SARS-CoV-2 spike sequences to myocarditis-associated antigens. eBioMedicine75, (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Markovic-Plese S, et al. T cell recognition of immunodominant and cryptic proteolipid protein epitopes in humans. J. Immunol. 1995;155:982–992. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.155.2.982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pelfrey C, Tranquill L, Vogt A, McFarland H. T cell response to two immunodominant proteolipid protein (PLP) peptides in multiple sclerosis patients and healthy controls. Mult. Scler. 1996;1:270–278. doi: 10.1177/135245859600100503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trotter JL, et al. T cell recognition of myelin proteolipid protein and myelin proteolipid protein peptides in the peripheral blood of multiple sclerosis and control subjects. J. Neuroimmunol. 1998;84:172–178. doi: 10.1016/S0165-5728(97)00260-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Macdonald WA, et al. T cell allorecognition via molecular mimicry. Immunity. 2009;31:897–908. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weinshenker BG, et al. Major histocompatibility complex class II alleles and the course and outcome of MS: A population-based study. Neurology. 1998;51:742–747. doi: 10.1212/WNL.51.3.742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zivadinov, R. et al. HLA‐DRB1*1501, ‐DQB1*0301, ‐DQB1*0302, ‐DQB1*0602, and ‐DQB1*0603 Alleles are Associated With More Severe Disease Outcome on Mri in Patients With Multiple Sclerosis. in International Review of Neurobiology vol. 79 521–535 (Academic Press, 2007). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Patsopoulos NA, et al. Fine-mapping the genetic association of the major histocompatibility complex in multiple sclerosis: HLA and non-HLA effects. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003926. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Greenbaum J, et al. Functional classification of class II human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules reveals seven different supertypes and a surprising degree of repertoire sharing across supertypes. Immunogenetics. 2011;63:325–335. doi: 10.1007/s00251-011-0513-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Selecting thresholds (cut-offs) for MHC class I and II binding predictions. IEDB Solutions Centerhttps://help.iedb.org/hc/en-us/articles/114094151811-Selecting-thresholds-cut-offs-for-MHC-class-I-and-II-binding-predictions.

- 27.Jouvenne P, Mounir S, Stewart JN, Richardson CD, Talbot PJ. Sequence analysis of human coronavirus 229E mRNAs 4 and 5: Evidence for polymorphism and homology with myelin basic protein. Virus Res. 1992;22:125–141. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(92)90039-C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murray RS, Brown B, Brain D, Cabirac GF. Detection of coronavirus RNA and antigen in multiple sclerosis brain. Ann. Neurol. 1992;31:525–533. doi: 10.1002/ana.410310511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Talbot PJ, Boucher A, Duquette P, Gruslin E. Coronaviruses and Neuroantigens: myelin proteins, myelin genes. Exp. Models Mult. Scler. 2005 doi: 10.1007/0-387-25518-4_43. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ellul MA, et al. Neurological associations of COVID-19. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19:767–783. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30221-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu Y, et al. Nervous system involvement after infection with COVID-19 and other coronaviruses. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020;87:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.03.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thieme, C. et al. The SARS-COV-2 T-Cell Immunity is Directed Against the Spike, Membrane, and Nucleocapsid Protein and Associated with COVID 19 Severity. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3606763 (2020). 10.2139/ssrn.3606763.

- 33.Grifoni A, et al. Targets of T cell responses to SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus in humans with COVID-19 disease and unexposed individuals. Cell. 2020;181:1489–1501.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.05.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tarke A, et al. Comprehensive analysis of T cell immunodominance and immunoprevalence of SARS-CoV-2 epitopes in COVID-19 cases. Cell Rep. Med. 2021;2:100204. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jordan SC, et al. T cell immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 and variants of concern (Alpha and Delta) in infected and vaccinated individuals. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2021;18:2554–2556. doi: 10.1038/s41423-021-00767-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gangaev, A. et al. Profound CD8 T cell responses towards the SARS-CoV-2 ORF1ab in COVID-19 patients. https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-33197/v1 (2020). 10.21203/rs.3.rs-33197/v1.

- 37.Tilocca B, et al. Immunoinformatic analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 envelope protein as a strategy to assess cross-protection against COVID-19. Microbes Infect. 2020;22:182–187. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2020.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shaw SY, Laursen RA, Lees MB. Analogous amino acid sequences in myelin proteolipid and viral proteins. FEBS Lett. 1986;207:266–270. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(86)81502-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amor S, Baker D, Groome N, Turk JL. Identification of a major encephalitogenic epitope of proteolipid protein (residues 56–70) for the induction of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis in Biozzi AB/H and nonobese diabetic mice. J. Immunol. 1993;150:5666–5672. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.150.12.5666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greer J. Increased immunoreactivity to two overlapping peptides of myelin proteolipid protein in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 1997;120:1447–1460. doi: 10.1093/brain/120.8.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dayhoff, M. O., Barker, W. C. & Hunt, L. T. [47] Establishing homologies in protein sequences. in Methods in Enzymology vol. 91 524–545 (Academic Press, 1983). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.França, L. C. et al. Molecular Mimicry between Zika virus and central nervous system inflammatory demyelinating disorders: the role of NS5 Zika virus epitope and PLP autoantigens. at 10.21203/rs.2.22564/v1 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.He X, et al. Structural snapshot of aberrant antigen presentation linked to autoimmunity: The immunodominant epitope of MBP complexed with I-Au. Immunity. 2002;17:83–94. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(02)00340-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.IPD-IMGT/HLA Database. https://www.ebi.ac.uk/ipd/imgt/hla/alleles/.

- 45.van Gerven NMF, et al. HLA-DRB1*03:01 and HLA-DRB1*04:01 modify the presentation and outcome in autoimmune hepatitis type-1. Genes Immun. 2015;16:247–252. doi: 10.1038/gene.2014.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hu F, et al. Novel findings of HLA association with anti-LGI1 encephalitis: HLA-DRB1*03:01 and HLA-DQB1*02:01. J. Neuroimmunol. 2020;344:577243. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2020.577243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Alvarenga MP, et al. The HLA DRB1*03:01 allele is associated with NMO regardless of the NMO-IgG status in Brazilian patients from Rio de Janeiro. J. Neuroimmunol. 2017;310:1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2017.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Skinningsrud B, et al. Multiple loci in the HLA complex are associated with Addison’s disease. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011;96:E1703–E1708. doi: 10.1210/jc.2011-0645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bhattarai, P., Allen, H., Aggarwal, A., Madden, D. & Dalton, K. Unmasking of Addison’s disease in COVID-19. SAGE Open Med. Case Rep.9, 2050313X211027758 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Oğuz, S. H. & Gürlek, A. Emergence of Autoimmune Type 1 Diabetes and Acute Adrenal Crisis Following COVID-19. https://www.researchsquare.com/article/rs-1015570/v1 (2021). 10.21203/rs.3.rs-1015570/v1.

- 51.Sánchez J, Cohen M, Zapater JL, Eisenberg Y. Primary adrenal insufficiency after COVID-19 infection. AACE Clin. Case Rep. 2021 doi: 10.1016/j.aace.2021.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Langton DJ, et al. The influence of HLA genotype on the severity of COVID-19 infection. HLA. 2021;98:14–22. doi: 10.1111/tan.14284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Migliorini F, et al. Association between HLA genotypes and COVID-19 susceptibility, severity and progression: a comprehensive review of the literature. Eur. J. Med. Res. 2021;26:84. doi: 10.1186/s40001-021-00563-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tavasolian, F. et al. HLA, Immune response, and susceptibility to COVID-19. Front. Immunol.11, (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.Pasello M, Manara MC, Scotlandi K. CD99 at the crossroads of physiology and pathology. J. Cell Commun. Signal. 2018;12:55–68. doi: 10.1007/s12079-017-0445-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Siwy J, et al. CD99 and polymeric immunoglobulin receptor peptides deregulation in critical COVID-19: A potential link to molecular pathophysiology? Proteomics. 2021;21:2100133. doi: 10.1002/pmic.202100133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Di Domizio J, et al. The cGAS-STING pathway drives type I IFN immunopathology in COVID-19. Nature. 2022 doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04421-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schwabenland M, et al. Deep spatial profiling of human COVID-19 brains reveals neuroinflammation with distinct microanatomical microglia-T-cell interactions. Immunity. 2021;54:1594–1610.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2021.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Engelhardt B. Development of the blood-brain barrier. Cell Tissue Res. 2003;314:119–129. doi: 10.1007/s00441-003-0751-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wong P, Coulombe PA. Loss of keratin 6 (K6) proteins reveals a function for intermediate filaments during wound repair. J. Cell Biol. 2003;163:327–337. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200305032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Libbey, J. E., McCoy, L. L. & Fujinami, R. S. Molecular Mimicry in Multiple Sclerosis. in International Review of Neurobiology vol. 79 127–147 (Academic Press, 2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 62.Bjornevik K, et al. Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science. 2022 doi: 10.1126/science.abj8222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lanz TV, et al. Clonally expanded B cells in multiple sclerosis bind EBV EBNA1 and GlialCAM. Nature. 2022 doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04432-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shalaby NM, Shehata HS. Could SARS-CoV-2 herald a surge of multiple sclerosis? Egypt J. Neurol. Psychiatry Neurosurg. 2021;57:22. doi: 10.1186/s41983-021-00277-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Song E, et al. Divergent and self-reactive immune responses in the CNS of COVID-19 patients with neurological symptoms. Cell Rep. Med. 2021;2:100288. doi: 10.1016/j.xcrm.2021.100288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liang Y, et al. Comprehensive antibody epitope mapping of the nucleocapsid protein of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus: Insight into the humoral immunity of SARS. Clin. Chem. 2005;51:1382–1396. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2005.051045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Smits VAJ, et al. The Nucleocapsid protein triggers the main humoral immune response in COVID-19 patients. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2021;543:45–49. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2021.01.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sun J, et al. T and B cell responses to myelin-oligodendrocyte glycoprotein in multiple sclerosis. J. Immunol. 1991;146:1490–1495. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.146.5.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.AlphaFold Protein Structure Database. https://alphafold.ebi.ac.uk/.

- 70.Goddard TD, et al. UCSF ChimeraX: Meeting modern challenges in visualization and analysis. Protein Sci. 2018;27:14–25. doi: 10.1002/pro.3235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Pettersen EF, et al. UCSF ChimeraX: Structure visualization for researchers, educators, and developers. Protein Sci. 2021;30:70–82. doi: 10.1002/pro.3943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Rickinson AB, Moss DJ. Human cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses to Epstein-Barr virus infection. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1997;15:405–431. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.15.1.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Moss P, Khan N. CD8+ T-cell immunity to cytomegalovirus. Hum. Immunol. 2004;65:456–464. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2004.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that all data in support of the main findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files. All other data (including raw data generated in the supplemental findings) are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

All code generated for this project is available on GitHub at the following repository: https://github.com/mad-scientist-in-training/PEPMatch_SARS-CoV-2_MS.