Abstract

Background

There are limited treatment options for uncomplicated urinary tract infection (uUTI) caused by resistant pathogens. Sulopenem etzadroxil/probenecid (sulopenem) is an oral thiopenem antibiotic active against multidrug-resistant pathogens that cause uUTIs.

Methods

Patients with uUTI were randomized to 5 days of sulopenem or 3 days of ciprofloxacin. The primary endpoint was overall success, defined as both clinical and microbiologic response at day 12. In patients with ciprofloxacin-nonsusceptible baseline pathogens, sulopenem was compared for superiority over ciprofloxacin; in patients with ciprofloxacin-susceptible pathogens, the agents were compared for noninferiority. Using prespecified hierarchical statistical testing, the primary endpoint was tested in the combined population if either superiority or noninferiority was declared in the nonsusceptible or susceptible population, respectively.

Results

In the nonsusceptible population, sulopenem was superior to ciprofloxacin, 62.6% vs 36.0% (difference, 26.6%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 15.1 to 7.4; P <.001). In the susceptible population, sulopenem was not noninferior to ciprofloxacin, 66.8% vs 78.6% (difference, −11.8%; 95% CI, −18.0 to 5.6). The difference was driven by a higher rate of asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) post-treatment in patients on sulopenem. In the combined analysis, sulopenem was noninferior to ciprofloxacin, 65.6% vs 67.9% (difference, −2.3%; 95% CI, −7.9 to 3.3). Diarrhea occurred more frequently with sulopenem (12.4% vs 2.5%).

Conclusions

Sulopenem was noninferior to ciprofloxacin in the treatment of uUTIs. Sulopenem was superior to ciprofloxacin in patients with uUTIs due to ciprofloxacin-nonsusceptible pathogens. Sulopenem was not noninferior in patients with ciprofloxacin-susceptible pathogens, driven largely by a lower rate of ASB in those who received ciprofloxacin.

Clinical Trial Registration

Keywords: sulopenem, uncomplicated urinary tract infection

This phase 3, double-blind, double-dummy study comparing sulopenem to ciprofloxacin in women with uncomplicated urinary tract infections demonstrated comparable clinical response rates between treatment groups and antibiotic class dependent rates of post-treatment asymptomatic bacteria.

Among the most common infections caused by multidrug-resistant Enterobacterales are those that involve the urinary tract. Uncomplicated urinary tract infections (uUTIs) account for 30 million prescriptions in the United States annually (IQVIA, data on file). While several oral antibiotics are available to treat uUTIs, including β-lactams, quinolones, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (TMP–SMX), fosfomycin, and nitrofurantoin, resistance rates are now ≥20% for some agents, a rate at which cultures should be considered, complicating the selection of empiric therapy [1–7] . Ineffective treatments may prompt additional testing and a second prescription, incurring additional costs. More antibiotics may lead to more adverse events [8] and may select for resistant colonizing pathogens, contributing to morbidity [9, 10]. New, safe, and well-tolerated orally bioavailable antibacterials that are active against multidrug-resistant pathogens are needed to address this problem [4].

Sulopenem etzadroxil, the prodrug of intravenous sulopenem, is an oral thiopenem that is active against multidrug-resistant gram-negative pathogens, including those that produce extended-spectrum β-lactamases (ESBLs), similar to ertapenem [11]. Combined with probenecid to extend its half-life in plasma, sulopenem obtains high concentrations in urine and was evaluated for treatment of uUTIs in women.

METHODS

Trial Design

This prospective, randomized, multicenter, double-blind, double-dummy study that compared oral sulopenem etzadroxil/probenecid (sulopenem) to oral ciprofloxacin in patients with uUTIs was conducted from August 2018 through January 2020 at 142 centers in 4 countries. The institutional review board or ethics committee for each site reviewed and approved the protocol. All patients signed written informed consent prior to participation.

Eligible patients were women aged ≥18 years with uUTIs, defined by a urinalysis positive for nitrite and either a positive leukocyte esterase or microscopic evidence of white blood cells, and ≥ 2 signs/symptoms of uUTI including urinary frequency, urgency, dysuria, or suprapubic pain, without evidence of fever, chills, costovertebral angle tenderness, flank pain, nausea, vomiting, or fever (Supplementary Table 1). A standardized questionnaire was used to collect symptoms at baseline and all subsequent visits. Urine for culture and susceptibility testing was collected at all visits. Susceptibility results were not made available to investigators until after the test-of-cure (TOC) assessment. Additional details are available in the Study Protocol (Supplementary Materials).

Randomization, Treatment, and Monitoring

Patients were randomized by blinded site staff in a 1:1 ratio to sulopenem or ciprofloxacin using a centralized interactive web randomization system with a block size of 2. Patients received a sulopenem etzadroxil 500 mg/probenecid 500 mg bilayer tablet twice daily for 5 days or ciprofloxacin 250 mg twice daily for 3 days [12]. Each regimen included a matched placebo to maintain the blind.

Efficacy End Points

The intent-to-treat (ITT) population comprised all randomized patients, the safety population comprised all ITT patients who received ≥ 1 dose of study medication, the modified ITT (MITT) population included all safety patients who had the disease under study, and the microbiologic MITT (mMITT) population was defined as all MITT patients with baseline urine cultures positive for Enterobacterales or Staphylococcus saprophyticus at ≥105 colony-forming units (CFU)/mL and ≤ 2 species of microorganisms. A clinically evaluable and a microbiologically evaluable population were also analyzed for efficacy.

A patient was a success if alive at the visit, had not received a nonstudy antibiotic for uUTI, had resolution of the symptoms present at trial entry, and had no new UTI symptoms and a urine culture collected at follow-up that demonstrated <103 CFU/mL of the baseline uropathogen. Isolates from TOC cultures that matched the genus and species of the baseline isolate but demonstrated a ≥ 4 times difference in minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for any tested antibiotic were examined using whole-genome sequencing (WGS) to confirm recurrence of the baseline isolate. Patients given an antibiotic active against a uropathogen, even if given for reasons other than uUTI, or if any outcome data were missing were defined as having an indeterminate outcome and considered a failure.

The primary end point, overall response, was a combined clinical and microbiologic response on day 12. Based on direction from the US Food and Drug Administration, overall response was to be compared in 2 subsets of the mMITT population: one with baseline pathogens susceptible to ciprofloxacin (MIC ≤1 μg/mL), the mMITT-S population and one with baseline pathogens nonsusceptible to ciprofloxacin (MIC ≥2 μg/mL), the mMITT-R population.

Additional efficacy assessments included clinical response on day 12 and overall and clinical responses at end of treatment (EOT; day 5) and the final visit (day 28).

Safety

All safety analyses were conducted on the safety population. Safety parameters included adverse events, clinical laboratory parameters, and vital signs. A treatment-emergent adverse event was any adverse event that was new, increased in frequency, or worsened in severity following initiation of study drug.

Statistical Analyses

The proposed sample size in the mMITT-S population was 441 patients per arm based on the method of Farrington and Manning and assumed a noninferiority margin of 10%, a power of 90%, a 1-sided alpha level of 0.025, and a 70% success rate. Assuming a 22% ciprofloxacin resistance rate and 105 patients per treatment group in the mMITT-R population, there was 90% power to show superiority given overall success rates of 66% and 43% in the sulopenem and ciprofloxacin groups, respectively. If 83% of the randomized patients met criteria for inclusion in the mMITT population, the sample size for the ITT population was 1364.

Two interim analyses were to be performed when overall response data at day 12 were available for approximately 33% and 66% of the patients to confirm the initial sample size estimate for the mMITT-S population based on the blinded overall outcome and evaluability rates. When 66% of the population had been enrolled, an unblinded interim analysis for sample size reestimation of the mMITT-R population based on conditional power was conducted [13]. A data monitoring committee supported by an independent, unblinded statistician conducted sample size reestimations and provided recommendations to the sponsor, who remained blinded to treatment.

The superiority of sulopenem was tested relative to ciprofloxacin in the mMITT-R population and noninferiority was tested in the comparison of sulopenem and ciprofloxacin in the mMITT-S population. Because these were separate objectives in mutually exclusive groups, alpha sharing to control the overall type I error rate was not required. In the combined mMITT population, a hierarchy of analyses was prespecified to control for inflation of the overall type I error [13]. If noninferiority or superiority was declared for the primary comparisons, further comparisons of the primary efficacy end point were to be statistically tested in the order presented in the prespecified sequence (Supplementary Table 2).

A test for superiority of sulopenem to ciprofloxacin in the mMITT-R population was based on a 2-sided 95% confidence interval (CI) for the observed treatment difference in success rates without stratification [14]. If the lower bound of the 95% CI was >0%, superiority of sulopenem to ciprofloxacin would be concluded. Similarly, the noninferiority hypothesis test is a 1-sided hypothesis test performed at the 2.5% level of significance based on the lower limit of the 2-sided 95% CI for the observed difference in the overall success rate (sulopenem minus ciprofloxacin) without stratification [14] in the mMITT-S population. If the lower limit of the 95% CI for difference in success rates is greater than −10%, noninferiority of sulopenem to ciprofloxacin would be concluded. Comparison of overall response in the mMITT population as specified in the hierarchical testing procedure was tested for noninferiority using the same procedure as for the mMITT-S population. Additional analyses calculated the CI using the Miettinen and Nurminen method [14] stratified for baseline susceptibility with the inverse variance as weights and also using a random effects model.

For measures of the primary end point at other time points, 2-sided 95% unstratified CIs were constructed for the observed difference in the overall success rates between the treatment groups; no conclusion of noninferiority was made. An assessment of the primary end point in which the urine culture collected at the follow-up visit demonstrated <102 CFU/mL of the baseline uropathogen in addition to other end point criteria was also performed. Kaplan–Meier curves for time to symptom resolution were provided.

Differences in baseline patient characteristics between treatment groups were analyzed using the χ 2 or Fisher exact test for dichotomous variables, the Wilcoxon rank sum test for ordinal variables and continuous variables, and the χ 2 test for analyses of superiority of the primary end point.

RESULTS

Patients

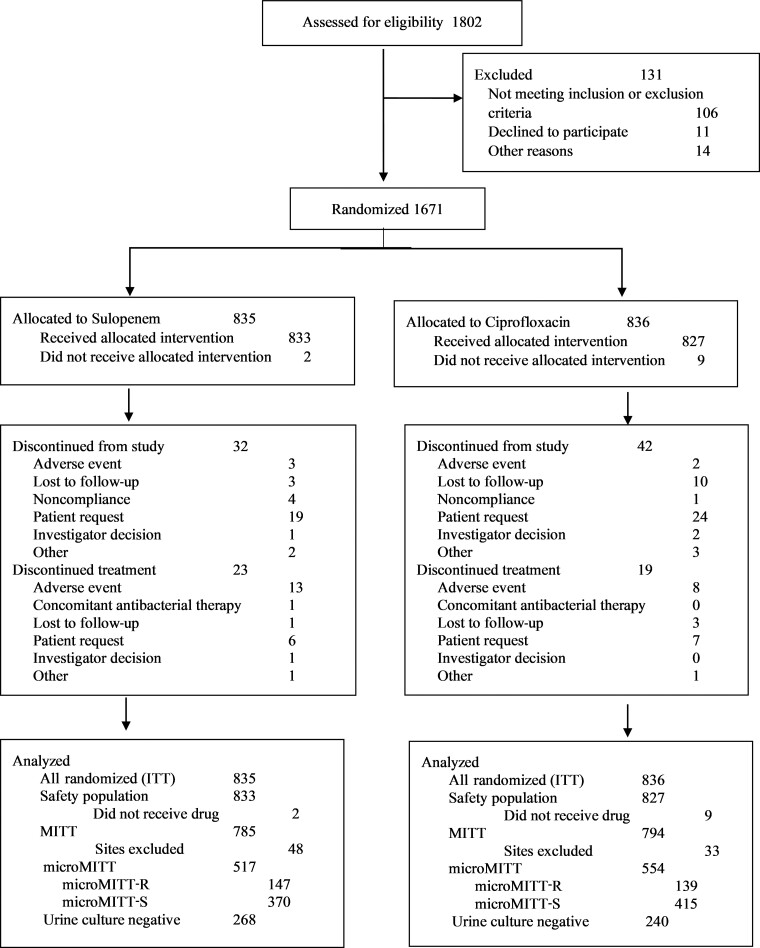

After the sample size was readjusted and as a consequence of a higher-than-expected rate of ciprofloxacin resistance, 1802 patients were screened, of whom 1671 were randomized, an increase over the originally targeted 1364. Eleven patients did not receive study drug, resulting in a safety population of 1660 patients. Prior to unblinding, patients from 2 centers were excluded from the efficacy population because of data integrity concerns, leaving 1579 patients in the MITT population, of whom 1071 had a study uropathogen at baseline. Of these, 286 (26.7%) had a ciprofloxacin-nonsusceptible organism and 785 (73.3%) a ciprofloxacin-susceptible organism (Figure 1, Supplementary Table 3).

Figure 1.

Analysis population disposition. Abbreviations: ITT, intent-to-treat; MITT, modified intent-to-treat; microMITT, microbiologic modified intent-to-treat with a qualifying baseline urine isolate; microMITT-R, microbiologic modified intent-to-treat with a qualifying baseline urine isolate nonsusceptible to ciprofloxacin; microMITT-S, microbiologic modified intent-to-treat with a qualifying baseline urine isolate susceptible to ciprofloxacin.

Baseline characteristics were similar among those in the safety and MITT-S populations (Table 1). The demographics of the mMITT-R population, however, differed from those of the mMITT-S population (Table 2). Patients with diabetes mellitus and a creatinine clearance <72 mL/min were more likely to have a ciprofloxacin-nonsusceptible pathogen at baseline (odds ratio 1.8; P = .006). Similar proportions of patients on sulopenem and ciprofloxacin completed treatment (Figure 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients in the Treated Populations

| Parameter | Safety Population | mMITT-R | mMITT-S | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sulopenem (N = 833) n (%) |

Ciprofloxacin (N = 827) n (%) |

Sulopenem (N = 147) n (%) |

Ciprofloxacin (N = 139) n (%) |

Sulopenem (N = 370) n (%) |

Ciprofloxacin (N = 415) n (%) |

|

| Age, y | ||||||

| ȃMean (SD) | 49.7 (18.7) | 50.2 (19.0) | 54.5 (19.3) | 56.3 (20.1) | 50.9 (19.0) | 49.9 (18.6) |

| ȃRange | 18, 89 | 18, 96 | 18, 89 | 18, 87 | 18, 89 | 18, 96 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| ȃHispanic or Latinx | 299 (35.9) | 260 (31.4) | 58 (39.5) | 53 (38.1) | 83 (22.4) | 101 (24.3) |

| Geographic region | ||||||

| ȃUnited States | 494 (59.3) | 466 (56.3) | 81 (55.1) | 82 (59.0) | 188 (50.8) | 218 (52.5) |

| Race | ||||||

| ȃBlack | 74 (8.9) | 67 (8.1) | 14(9.5) | 12 (8.6) | 33 (8.9) | 34 (8.2) |

| ȃWhite | 734 (88.1) | 746 (90.2) | 130 (88.4) | 126 (90.6) | 330 (89.2) | 376 (90.6) |

| ȃOther | 25 (3.0) | 14 (1.7) | 3 (2.0) | 1 (0.7) | 7 (1.9) | 5 (1.2) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 107 (12.8) | 113 (13.7) | 27 (18.4) | 26 (18.7) | 42 (11.4) | 49 (11.8) |

| Body mass index, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 27.9 (6.8) | 27.5 (6.3) | 28.3 (7.1) | 28.6 (6.4) | 27.6 (6.7) | 27.3 (6.4) |

| Creatinine clearancea, mean (SD), mL/min | 79.6 (27.0) | 79.3 (26.4) | 74.4 (28.2) | 71.0 (28.2) | 76.7 (27.4) | 79.9 (25.0) |

Safety population includes all patients randomized who received a dose of study drug.

Abbreviations: mMITT-R, microbiologic modified intent-to-treat with a qualifying baseline urine isolate nonsusceptible to ciprofloxacin; mMITT-S, microbiologic modified intent-to-treat with a qualifying baseline urine isolate susceptible to ciprofloxacin; SD, standard deviation.

aCalculated by Cockcroft-Gault method.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Patients by Quinolone Susceptibility

| Parameter | mMITT-S (N = 785) n (%) |

mMITT-R (N = 286) n (%) |

P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | <.001 | ||

| ȃMean (SD) | 50.4 (18.8) | 55.4 (19.7) | |

| ȃMin, max | 18.0, 96.0 | 18.0, 89.0 | |

| Ethnicity | <.001 | ||

| ȃHispanic or Latinx | 184 (23.4) | 111 (38.8) | |

| ȃNot Hispanic or Latinx | 598 (76.2) | 174 (60.8) | |

| ȃNot reported | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.3) | |

| Geographic region | .091 | ||

| ȃUnited States | 406 (51.7) | 163 (57.0) | |

| ȃNot the United States | 379 (48.3) | 123 (43.0) | |

| Race | .661 | ||

| ȃBlack or African American | 67 (8.5) | 26 (9.1) | |

| ȃAsian | 6 (0.8) | 2 (0.7) | |

| ȃWhite | 706 (89.9) | 256 (89.5) | |

| ȃOther | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.7) | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 91 (11.6) | 53 (18.5) | .004 |

| Body mass index, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 27.5 (6.6) | 28.5 (6.8) | .008 |

| Creatinine clearance,a mean (SD), mL/min | 78.4 (26.2) | 72.7 (28.2) | .001 |

Abbreviations: mMITT-R, microbiologic modified intent-to-treat with a qualifying baseline urine isolate nonsusceptible to ciprofloxacin; mMITT-S, microbiologic modified intent-to-treat with a qualifying baseline urine isolate susceptible to ciprofloxacin; SD, standard deviation.

aCalculated by Cockcroft-Gault method.

The predominant pathogen in the mMITT population was Escherichia coli followed by Klebsiella pneumoniae and Proteus mirabilis with similar distributions in the mMITT-R and mMITT-S populations (Table 3). blaCTX-M-15 was identified in 69 of 123 (56.1%) isolates that were both ciprofloxacin-nonsusceptible and ESBL-positive. Among all uropathogens at baseline, 53 of 1071 (4.9%) pathogens were resistant to all 4 commonly used classes of antibacterials (quinolones, at least 1 β-lactam, nitrofurantoin, and TMP–SMX; Table 4). Four (0.4%) baseline uropathogens were carbapenem-resistant.

Table 3.

Distribution of Study Uropathogens at Baseline

| Uropathogens by Study Population | Sulopenem n (%) |

Ciprofloxacin n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| mMITT-R | ||

| ȃNumber of patients | 147 | 139 |

| ȃNumber of organisms | 154 | 144 |

| ȃȃEscherichia coli | 127 (86.4) | 120 (86.3) |

| ȃȃKlebsiella pneumoniae | 14 (9.5) | 16 (11.5) |

| ȃȃProteus mirabilis | 9 (6.1) | 6 (4.3) |

| ȃȃMorganella morganii | 3 (2.0) | 1 (0.7) |

| ȃȃEnterobacter cloacae complex | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) |

| ȃȃProvidencia stuartii | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.7) |

| mMITT-S | ||

| ȃNumber of patients | 370 | 415 |

| ȃNumber of organisms | 381 | 430 |

| ȃȃEscherichia coli | 313 (84.6) | 349 (84.1) |

| ȃȃKlebsiella pneumoniae | 37 (10.0) | 32 (7.7) |

| ȃȃProteus mirabilis | 8 (2.2) | 11 (2.7) |

| ȃȃStaphylococcus saprophyticus | 5 (1.4) | 8 (1.9) |

| ȃȃKlebsiella aerogenes | 4 (1.1) | 6 (1.4) |

| ȃȃCitrobacter freundii | 0 (0.0) | 6 (1.4) |

| ȃȃCitrobacter koseri | 4 (1.1) | 1 (0.2) |

| ȃȃEnterobacter cloacae complex | 3 (0.8) | 2 (0.5) |

| ȃȃKlebsiella oxytoca | 2 (0.5) | 3 (0.7) |

| ȃȃKlebsiella variicola | 4 (1.1) | 1 (0.2) |

| ȃȃLelliottia amnigena | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.7) |

| ȃȃMorganella morganii | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.7) |

| ȃȃRaoultella planticola | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.5) |

| ȃȃEnterobacter aerogenes | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| ȃȃPantoea septica | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

| ȃȃSerratia marcescens | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.2) |

Patients could have more than 1 pathogen.

Abbreviations: mMITT-R, microbiologic modified intent-to-treat with a qualifying baseline urine isolate nonsusceptible to ciprofloxacin; mMITT-S, microbiologic modified intent-to-treat with a qualifying baseline urine isolate susceptible to ciprofloxacin.

Table 4.

Distribution of Pathogens by Extended-Spectrum β-Lactamase, Ciprofloxacin, Trimethoprim–Sulfamethoxazole, and Nitrofurantoin Susceptibility—Microbiologic Modified Intent-to-Treat Population

| Susceptibility Category | Sulopenem (N = 517) n (%) |

Ciprofloxacin (N = 554) n (%) |

Total (N = 1071) n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ciprofloxacin-nonsusceptible | 150 (29.0) | 143 (25.8) | 293 (27.4) |

| β-lactam–nonsusceptible | 330 (63.8) | 345 (62.3) | 675 (63.0) |

| ȃExtended-spectrum β-lactamase–positive | 73 (14.1) | 72 (13.0) | 145 (13.5) |

| ȃOnly amoxicillin/ampicillin–nonsusceptible | 88 (17.0) | 95 (17.1) | 183 (17.1) |

| Trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole-nonsusceptible | 171 (33.1) | 167 (30.1) | 338 (31.6) |

| Nitrofurantoin-nonsusceptible | 97 (18.8) | 95 (17.1) | 192 (17.9) |

| Nonsusceptible to 3 classes | 65 (12.6) | 51 (9.2) | 116 (10.8) |

| Nonsusceptible to 4 classes | 25 (4.8) | 28 (5.1) | 53 (4.9) |

Patients were considered extended-spectrum β-lactamase–positive if they had a baseline urine specimen positive for at least 1 Enterobacterales with a ceftriaxone minimum inhibitory concentration >1 µg/mL. A pathogen is β-lactam–resistant if it is resistant to at least 1 of the following drugs: sulopenem, cefazolin, ertapenem, meropenem, ampicillin, ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, amoxicillin, imipenem, piperacillin-tazobactam. Nonsusceptible to 3 classes = nonsusceptible to ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, and at least 1 β-lactam. Nonsusceptible to 4 classes = nonsusceptible to ciprofloxacin, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole, at least 1 β-lactam, and nitrofurantoin.

Efficacy Outcomes

In the mMITT-R population, sulopenem was superior to ciprofloxacin (Table 5, Supplementary Table 4). In the mMITT-S population, sulopenem was not noninferior to ciprofloxacin. As superiority was declared in 1 of the 2 comparisons, the hierarchical testing procedure dictated a comparison of outcomes in the mMITT population. Here, sulopenem was noninferior to ciprofloxacin. Additional analyses of the primary end point are consistent with these observations (Supplementary Tables 5 and 6).

Table 5.

Primary and Secondary Efficacy End Points

| Time of End Point Assessment | Sulopenem etzadroxil/Probenecid n/N (%) |

Ciprofloxacin n/N (%) |

Absolute Difference (95% Confidence Interval) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Combined clinical and microbiologic response | |||

| Day 5 (end of treatment) | |||

| ȃmMITT-R | 95/147 (64.6) | 42/139 (30.2) | 34.4 (23.1 to 44.8) |

| ȃmMITT-S | 240/370 (64.9) | 271/415 (65.3) | −0.4 (−7.1 to 6.2) |

| ȃmMITT | 335/517 (64.8) | 313/554 (56.5) | 8.3 (2.4 to 14.1) |

| Day 12 (test of cure: primary end point) | |||

| ȃmMITT-R | 92/147 (62.6) | 50/139 (36.0) | 26.6 (15.1 to 37.4) |

| ȃmMITT-S | 247/370 (66.8) | 326/415 (78.6) | −11.8 (−18.0 to −5.6) |

| ȃmMITT | 339/517 (65.6) | 376/554 (67.9) | −2.3 (−7.9 to 3.3) |

| Day 28 (late follow-up) | |||

| ȃmMITT-R | 100/147 (68.0) | 62/139 (44.6) | 23.4 (12.0 to 34.3) |

| ȃmMITT-S | 256/370 (69.2) | 323/415 (77.8) | −8.6 (−14.8 to −2.5) |

| ȃmMITT | 356/517 (68.9) | 385/554 (69.5) | −0.6 (−6.2 to 4.9) |

| Clinical response | |||

| Day 5 | |||

| ȃmMITT-R | 99/147 (67.3) | 83/139 (59.7) | 7.6 (−3.5 to 18.7) |

| ȃmMITT-S | 256/370 (69.2) | 290/415 (69.9) | −0.7 (−7.2 to 5.7) |

| ȃmMITT | 355/517 (68.7) | 373/554 (67.3) | 1.3 (−4.3 to 6.9) |

| Day 12 | |||

| ȃmMITT-R | 122/147 (83.0) | 87/139 (62.6) | 20.4 (10.2 to 30.4) |

| ȃmMITT-S | 300/370 (81.1) | 349/415 (84.1) | −3.0 (−8.4 to 2.3) |

| ȃmMITT | 422/517 (81.6) | 436/554 (78.7) | 2.9 (−1.9 to 7.7) |

| ȃMITT | 647/785 (82.4) | 638/794 (80.4) | 2.1 (−1.8 to 5.9) |

| Day 28 | |||

| ȃmMITT-R | 122/147 (83.0) | 82/139 (59.0) | 24.0 (13.7 to 34.0) |

| ȃmMITT-S | 295/370 (79.7) | 341/415 (82.2) | −2.4 (−8.0 to 3.1) |

| ȃmMITT | 417/517 (80.7) | 423/554 (76.4) | 4.3 (−0.6 to 9.2) |

| ȃMITT | 643/785 (81.9) | 631/794 (79.5) | 2.4 (−1.5 to 6.3) |

| Combined response | |||

| Day 12 | |||

| ȃExtended-spectrum β-lactamase–positive | 41/73 (56.2) | 34/72 (47.2) | 8.9 (−7.3, 24.8) |

| ȃβ-lactam-, ciprofloxacin-, and TMP–SMX-nonsusceptible | 40/65 (61.5) | 19/51 (37.3) | 24.3 (5.9 to 41.0) |

| ȃβ-lactam-, ciprofloxacin-, TMP–SMX-, and nitrofurantoin-nonsusceptible | 20/25 (80.0) | 12/28 (42.9) | 37.1 (10.8 to 58.5) |

Abbreviations: mMITT, microbiologic modified intent-to-treat with a qualifying baseline urine isolate; mMITT-R, microbiologic modified intent-to-treat with a qualifying baseline urine isolate nonsusceptible to ciprofloxacin; mMITT-S, microbiologic modified intent-to-treat with a qualifying baseline urine isolate susceptible to ciprofloxacin; TMP–SMX, trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole.

Reasons for failure are provided in Table 6. Patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB) contributed substantially to the difference in outcome between treatment regimens. Patients with ASB treated with sulopenem were no more likely to experience clinical relapse at the next visit than were patients otherwise cured at the same visit (Table 7). Clinical data on the 8 sulopenem patients who had ASB at TOC and then experienced clinical relapse at day 28 are presented in Supplementary Table 7.

Table 6.

Reasons for Treatment Failure

| Reason for Overall Nonresponse at Test of Cure | mMITT-R | mMITT-S | mMITT | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sulopenem (N = 147) n (%) |

Ciprofloxacin (N = 139) n (%) |

Sulopenem (N = 370) n (%) |

Ciprofloxacin (N = 415) n (%) |

Sulopenem (N= 517) n (%) |

Ciprofloxacin (N= 554) n (%) |

|

| Total number of nonresponders | 49 (33.3) | 84 (60.4) | 105 (28.4) | 65 (15.7) | 154 (29.8) | 149 (26.9) |

| ȃMicrobiologic failure only | 27 (18.4) | 38 (27.3) | 47 (12.7) | 16 (3.9) | 74 (14.3) | 54 (9.7) |

| ȃClinical failure only | 17 (11.6) | 13 (9.4) | 38 (10.3) | 42 (10.1) | 55 (10.6) | 55 (9.9) |

| ȃBoth clinical and microbiologic failure | 5 (3.4) | 25 (18.0) | 18 (4.9) | 4 (1.0) | 23 (4.4) | 29 (5.2) |

| ȃReceipt of nonstudy antibacterial therapy for uUTI | 0 (0.0) | 11 (7.9) | 4 (1.1) | 5 (1.2) | 4 (0.8) | 16 (2.9) |

| ȃDeath due to uUTI | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| ȃIndeterminate outcome | 6 (4.1) | 5 (3.6) | 18 (4.9) | 24 (5.8) | 24 (4.6) | 29 (5.2) |

Microbiologic failure is defined as test-of-cure visit urine culture with ≥103 CFU/mL of the baseline uropathogen; clinical failure is defined as no resolution or worsening of uUTI symptoms present at trial entry and/or new uUTI symptoms. Patients who received nonstudy antibacterial therapy may have another reason for failure.

Abbreviations: mMITT, microbiologic modified intent-to-treat with a qualifying baseline urine isolate; mMITT-R, microbiologic modified intent-to-treat with a qualifying baseline urine isolate nonsusceptible to ciprofloxacin; mMITT-S, microbiologic modified intent-to-treat with a qualifying baseline urine isolate susceptible to ciprofloxacin; uUTI, uncomplicated urinary tract infection.

Table 7.

Asymptomatic Bacteriuria and Subsequent Clinical Response to Treatment Among Sulopenem-Treated Patients

| Overall Response at End of Treatment (Day 5) | Clinical Failure at TOC (Day 12) n/N (%) |

|---|---|

| Success | 31/335 (9.3%) |

| Asymptomatic bacteriuria | 1/12 (8.3%) |

| Overall response at TOC (day 12) | Clinical failure at final visit (day 28) |

| Success | 20/339 (5.9%) |

| Asymptomatic bacteriuria | 8/74 (10.8%) |

The table presents patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria at a given visit and the proportion who experienced a clinical failure at the next visit. Clinical failure includes symptoms of uncomplicated urinary tract infection or receipt of an antibiotic or both. P value (Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test) at day 12 = 0.914; P value (Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test) at day 28 = 0.128.

Abbreviation: TOC, test of cure visit.

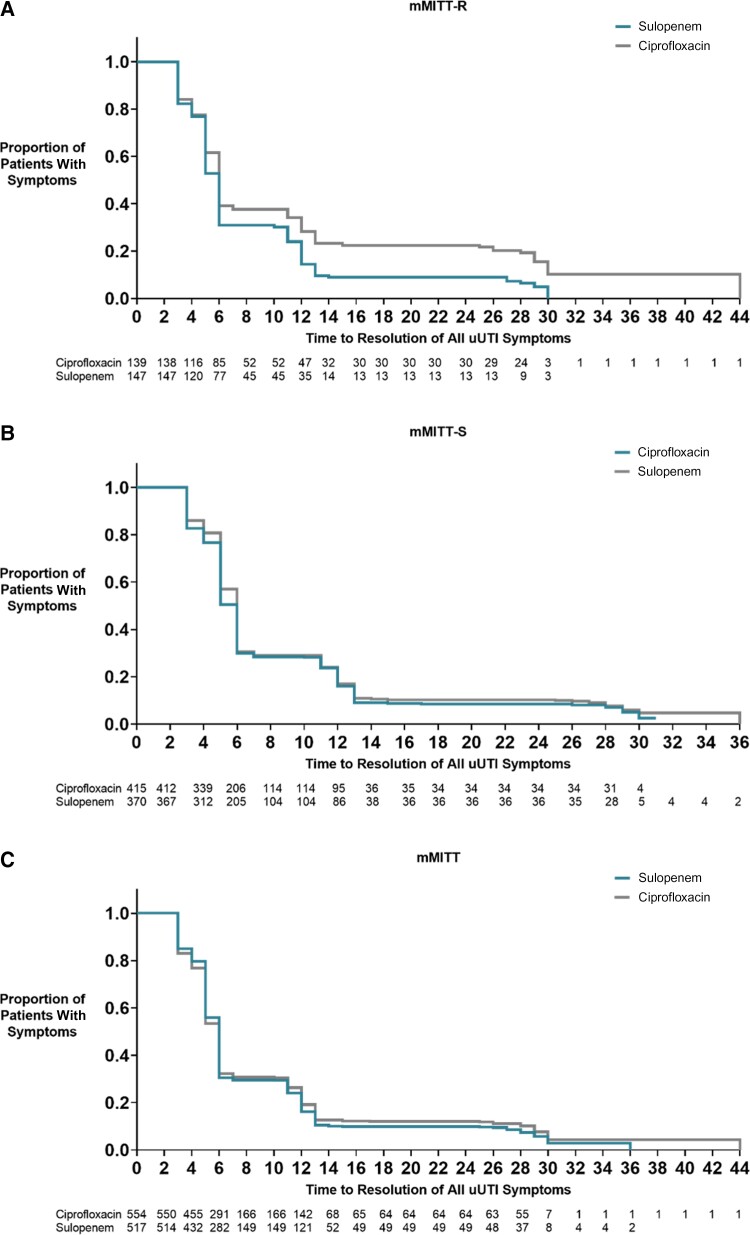

Clinical response to treatment, which by definition does not include ASB, was assessed at day 12 (Table 5). In the mMITT-R population, response rates for sulopenem (83.0%) were again higher than the rate for patients who received ciprofloxacin (62.6%). In the mMITT-S population, the lower limit of the difference in clinical response rates was greater than −10%. Clinical response was observed in 300 of 370 patients (81.1%) treated with sulopenem and 349 of 415 patients (84.1%) treated with ciprofloxacin (difference, −3.0%; 95% CI, −8.4% to 2.3%). Clinical response rates were similar in the mMITT population, as was resolution of clinical symptoms over time (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier analysis of the time to resolution of symptoms in days since first treatment for patients treated with either sulopenem or ciprofloxacin. A, mMITT-R, microbiologic modified intent-to-treat with a qualifying baseline urine isolate nonsusceptible to ciprofloxacin. B, mMITT-S, microbiologic modified intent-to-treat with a qualifying baseline urine isolate susceptible to ciprofloxacin. C, mMITT, microbiologic modified intent-to-treat with a qualifying baseline urine isolate. Patients who received rescue antibiotic therapy prior to resolution are censored at day 29. Abbreviation: uUTI, uncomplicated urinary tract infection.

Among sulopenem-treated patients, the overall combined response at EOT was similar to that of the clinical response, as ASB was uncommon at this visit (Table 5).

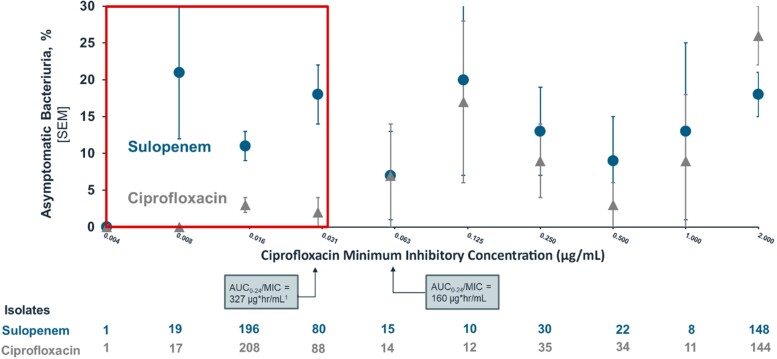

In a post hoc analysis performed to better understand the contribution of ASB to treatment outcome, the overall success for each treatment regimen is provided by MIC of the baseline pathogen (Figure 3, Supplementary Table 8). As described above, higher treatment responses in patients treated with sulopenem were identified when the ciprofloxacin MIC was ≥2 μg/mL. Similar outcomes were observed for pairwise comparisons of MICs between >0.03 μg/mL and <2 μg/mL. Differences in outcome between the 2 regimens only became evident at ciprofloxacin MICs ≤0.03 μg/mL when the rate of ASB fell for ciprofloxacin-treated patients but remained the same for those who received sulopenem.

Figure 3.

The proportion of patients with asymptomatic bacteriuria at the test-of-cure visit by the MIC to ciprofloxacin of that patient's baseline isolate, treated with either sulopenem or ciprofloxacin. The AUC0–24 for ciprofloxacin is calculated based on the US Ciprofloxacin Prescribing Information [12] and the AUC0–24/MIC is provided as per reference [21]. The red box indicates urine isolates with an MIC at the projected AUC/MIC threshold for tissue levels of ciprofloxacin. Abbreviations: AUC, area under the curve; MIC, minimum inhibitory concentration; SEM , standard error of the mean.

The microbiologic response for sulopenem-treated patients in the mMITT population demonstrated activity against all pathogens at all MIC thresholds (Supplementary Table 9). Two sulopenem-treated patients with K. pneumoniae at baseline with sulopenem MICs ≥4 μg/mL were considered overall successes at TOC. One sulopenem patient had an isolate cultured post-baseline (MIC = 0.25 μg/mL) that had an MIC >4 time the baseline result (MIC = 0.03 μg/mL), confirmed to have a similar sequence type by WGS; this patient was a clinical failure.

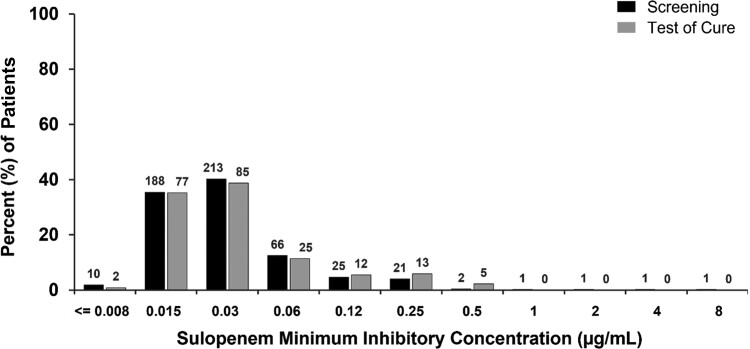

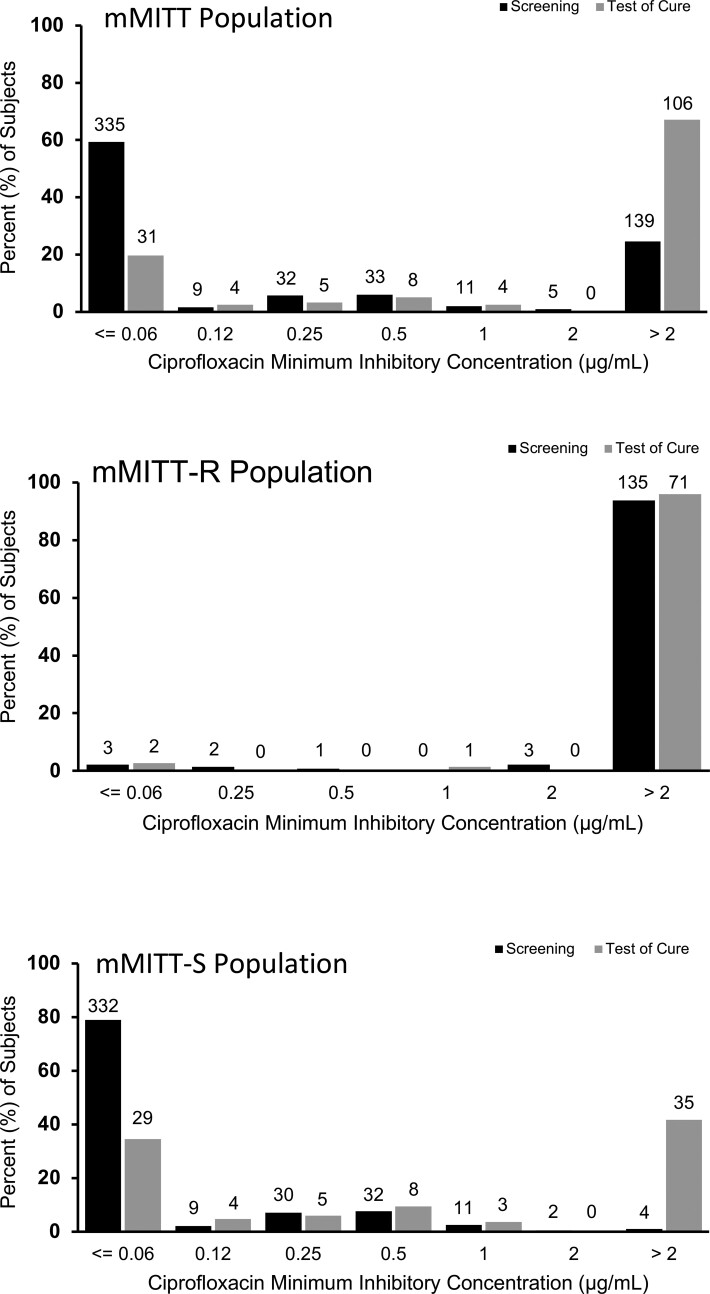

To explore the impact of therapy on organism susceptibility, we looked at the MICs of all organisms identified at any CFU/mL in urine cultures both before and after treatment, not just recurrent baseline pathogens. The distribution of sulopenem MICs did not differ after sulopenem treatment (Figure 4); however, 35 of 84 (41.7%) ciprofloxacin-treated patients with ciprofloxacin-susceptible uropathogens at baseline had a ciprofloxacin-nonsusceptible organism at TOC (Figure 5). Polymerase chain reaction testing of the initial urine sample for these 35 patients did not reveal any evidence of a quinolone-resistance gene, confirming that a resistant clone was not present at baseline.

Figure 4.

Organisms at screening and baseline include any uropathogen isolated in the urine culture, regardless of colony count. N above columns indicates number of organisms.

Figure 5.

Organisms at screening and baseline include any uropathogen isolated in the urine culture, regardless of colony count. N above columns indicates number of organisms. Abbreviations: mMITT, microbiologic modified intent-to-treat with a qualifying baseline urine isolate; mMITT-R, microbiologic modified intent-to-treat with a qualifying baseline urine isolate nonsusceptible to ciprofloxacin; mMITT-S, microbiologic modified intent-to-treat with a qualifying baseline urine isolate susceptible to ciprofloxacin.

Safety

Adverse events were reported more frequently in sulopenem-treated patients than in those treated with ciprofloxacin (Table 8), driven by a higher incidence of mild diarrhea or loose stool, which tended to resolve while continuing therapy. There were no reported cases of Clostridioides difficile colitis. Discontinuation of treatment for adverse events was uncommon. Serious adverse events (SAEs) were infrequent on each regimen. A treatment-related SAE occurred in a 54-year-old sulopenem-treated patient; she developed angioedema and was treated successfully as an outpatient. One sulopenem-treated patient died of lung adenocarcinoma 5 months after completing therapy.

Table 8.

Safety Analysis

| Variable | Sulopenem Etzadroxil/Probenecid (N = 833) n (%) |

Ciprofloxacin (N= 827) n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Any adverse event | ||

| ȃAny event, no. of patients (%) | 208 (25.0) | 116 (14.0) |

| ȃTotal no. of events | 361 | 168 |

| Treatment-related adverse event | ||

| ȃAny event, no. of patients (%) | 207 (24.8) | 115 (13.9) |

| ȃTotal no. of events | 223 | 70 |

| Serious adverse event, no. of patients (%) | ||

| ȃAny event | 6 (0.7) | 2 (0.2) |

| ȃTreatment-related event | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Death, no. (%) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Treatment-limiting adverse event, no. of patients (%) | 13 (1.6) | 8 (1.0) |

| Most common treatment-related adverse event, no. of patients (%) | ||

| ȃDiarrhea | 103 (12.4) | 21 (2.5) |

| ȃNausea | 32 (3.8) | 30 (3.6) |

| ȃHeadache | 18 (2.2) | 18 (2.2) |

| ȃVomiting | 13 (1.6) | 11 (1.3) |

| ȃDizziness | 9 (1.1) | 5 (0.6) |

DISCUSSION

Carbapenems have been used to treat UTIs since the introduction of imipenem/cilastatin 35 years ago. In this study of a population of women similar to those in a typical community setting [15, 16], sulopenem etzadroxil/probenecid, an orally bioavailable thiopenem, demonstrated superiority to ciprofloxacin in patients whose baseline uropathogen was resistant to ciprofloxacin. At the time this study was designed, ciprofloxacin was the most commonly used antibiotic for treating uUTIs, in spite of increasing rates of resistance and concerns about collateral damage associated with its use [1]. Resistance of any baseline pathogen to ciprofloxacin was observed in 27% of study participants, and collateral damage was evidenced by increased rates of quinolone resistance after treatment with ciprofloxacin.

While nitrofurantoin-resistant E. coli was observed in only 5.1% patients, the resistance rate increased to 18% when P. mirabilis and K. pneumoniae were included. Resistance to TMP–SMX was noted in 32% of patients. Five percent of study patients had a uropathogen resistant to all oral antibiotics commonly used for uUTIs; treatment with sulopenem was successful in 20 of 25 (80.0%) of these patients. Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines [1] recommend avoiding empiric treatment of acute pyelonephritis with ciprofloxacin when community rates of resistance exceed 10%. The data from this study, though generated in patients with uUTIs, support those recommendations, as the success rate of mismatched treatment is low and associated with clinical consequences.

Sulopenem was not noninferior to ciprofloxacin in patients whose baseline uropathogen was susceptible to ciprofloxacin. The difference in response rates was driven primarily by a higher rate of ASB among those who received sulopenem. The presence of ASB 1 week or more after completing therapy could portend either a clinical relapse or a return to the patient's baseline bladder microbiome. Sulopenem-treated patients, however, did not have a higher rate of clinical relapse, making it more likely that the presence of pathogens in the urine reflected bladder recolonization. The inclusion of ASB in the primary end point for studies of UTIs should be reconsidered, as it implies that post-treatment cultures should be obtained to document resolution of infection, a practice inconsistent with current treatment recommendations [17].

Why would ASB occur sooner post-treatment among sulopenem-treated patients than among those treated with ciprofloxacin? One possible explanation is that ciprofloxacin has a greater impact on vaginal flora than a β-lactam such as sulopenem and that this in turn influences the rate of bladder recolonization. Similar observations have been made in 2 previous studies of uUTI and in a recent mouse model of UTI [18–20]. The area under the curve (AUC)0–24 of ciprofloxacin in plasma after 250 mg twice daily dosing is approximately 9.6 μg × h/mL [12]. An AUC0–24/MIC of approximately 125 is required for achieving clinical and microbiologic success with ciprofloxacin [22], and this ratio would be achieved for organisms with an MIC <0.06 μg/mL. Consistent with this potential effect and assuming equal tissue and plasma concentrations, a lower rate of ASB was seen only in those ciprofloxacin-treated patients whose baseline uropathogens had MICs <0.06 µg/mL. This effect would not be relevant for organisms in the urine, where concentrations of ciprofloxacin are significantly higher than in plasma, but rather for those organisms among colonizing flora of the perineum and vagina, potential sources of bladder recolonization [20, 23].

This concentration-dependent effect of ciprofloxacin on vaginal flora would also carry with it the potential for selection of increasingly resistant pathogens among post-treatment flora. In this study, 35 of 420 (8.3%) patients without ciprofloxacin-nonsusceptible pathogens at baseline had a ciprofloxacin-nonsusceptible pathogen in their urine culture post-treatment. More worrisome, many of these isolates carried the bla CTX-M-15 ESBL resistance gene, a commonly circulating plasmid among E. coli [24], making future treatment with a quinolone or a non-penem β-lactam more likely to be unsuccessful.

uUTI in the community is most commonly treated empirically. The empirically treated population is best reflected in this study's MITT population in which clinical outcomes for sulopenem and ciprofloxacin were essentially the same. In the mMITT population in which microbiologic responses can also be evaluated, both the clinical and combined clinical and microbiologic outcomes were again similar. While a difference in outcome was seen among patients with ciprofloxacin-susceptible pathogens, this difference was due to the occurrence of ASB 7 days post-treatment, which is not relevant to patients and does not drive the clinician's initial empiric treatment decision.

Sulopenem was generally well tolerated. The only adverse event seen more frequently on sulopenem was mild, self-limited diarrhea. When used judiciously, sulopenem would provide an important option for the treatment of patients with uUTI known or suspected to be caused by drug-resistant pathogens.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Michael W Dunne, Iterum Therapeutics, Old Saybrook, Connecticut, USA.

Steven I Aronin, Iterum Therapeutics, Old Saybrook, Connecticut, USA.

Anita F Das, Das Statistical Consulting, Guerneville, California, USA.

Karthik Akinapelli, Iterum Therapeutics, Old Saybrook, Connecticut, USA.

Michael T Zelasky, Iterum Therapeutics, Old Saybrook, Connecticut, USA.

Sailaja Puttagunta, Iterum Therapeutics, Old Saybrook, Connecticut, USA.

Helen W Boucher, Tufts Medicine and Tufts University School of Medicine, Boston Massachusetts, USA.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Clinical Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

Notes

Financial support. This work was supported by Iterum Therapeutics.

References

- 1. Gupta K, Hooton TM, Naber KG, et al. International clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis and pyelonephritis in women: a 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the European Society for Microbiology and Infectious Diseases. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52:e103–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fihn SD. Acute uncomplicated urinary tract infection in women. N Engl J Med 2003; 349:259–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Talan DA, Takhar SS, Krishnadasan A, et al. Emergence of extended-spectrum β-lactamase urinary tract infections among hospitalized emergency department patients in the United States. Ann Emerg Med 2021; 77:32–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Critchley IA, Cotroneo N, Pucci MJ, Mendes R. The burden of antimicrobial resistance among urinary tract isolates of Escherichia coli in the United States in 2017. PLoS One 2019; 14:e0220265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dunne MW, Puttagunta S, Aronin SI, Brossette S, Murray J, Gupta V. Impact of empirical antibiotic therapy on outcomes of outpatient urinary tract infection due to nonsusceptible Enterobacterales. Microbiol Spectrum 2022; 10:e02359–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Aronin SI, Gupta V, Dunne MW, Watts JA, Yu KC. Regional differences in antibiotic-resistant Enterobacterales urine isolates in the United States. Int J Infect Dis 2022; 119:142–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dunne MW, Aronin SI, Yu KC, Watt JA, Gupta V. A multicenter analysis of trends in resistance in urinary Enterobacterales isolates from ambulatory patients in the United States: 2011–2020. BMC Infect Dis 2022; 22:194–205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. ten Doesschate T, van Haren E, Wijma RA, Koch BCP, Bonten MJM, van Werkhoven CH. The effectiveness of nitrofurantoin, fosfomycin and trimethoprim for the treatment of cystitis in relation to renal function. Clin Microbiol Infect 2020; 26:1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gharbi M, Drysdale JH, Lishman HL, et al. Antibiotic management of urinary tract infection in elderly patients in primary care and its association with bloodstream infections and all-cause mortality: population-based cohort study. BMJ 2019; 364:1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jorgensen S, Zurayk M, Yeung S, et al. Risk factors for early return visits to the emergency department in patients with urinary tract infection. Am J Emerg Med 2018; 36:12–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Karlowsky JA, Adam HJ, Baxter MR, et al. In vitro activity of sulopenem, an oral penem, against urinary isolates of Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018; 63:e01832–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ciprofloxacin [package insert]. Whippany, NJ: Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals Inc.; 2019.

- 13. Lan KKG, Wittes J. The B-value: a tool for monitoring data. Biometrics 1988; 44:579–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Westfall PH, Krishen A. Optimally weighted, fixed sequence and gatekeeper multiple testing procedures. J Stat Plan Infer 2001; 99:25–40. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Miettinen O, Nurminen M. Comparative analysis of two rates. Stat Med 1985; 4:213–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Taur Y, Smith MA. Adherence to the Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines in the treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infection. Clin Infect Dis 2007; 44:769–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kaye KS, Gupta V, Mulgirigama A, et al. Antimicrobial resistance trends in urine Escherichia coli isolates from adult and adolescent females in the United States from 2011 to 2019: rising ESBL strains and impact on patient management. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73:1992–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sobel J. Urinary tract infections. In: Bennet JE, Dolin R, Blaser M, eds. Mandell, Douglas, and Bennet. Principles and practice of infectious diseases. Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2020:988. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hooton TM, Scholes D, Gupta K, Stapleton AE, Roberts PL, Stamm WE. Amoxicillin-clavulanate vs ciprofloxacin for the treatment of uncomplicated cystitis in women. A randomized trial. JAMA 2005; 293:949–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hooton TM, Roberts PL, Stapleton AE. Cefpodoxime vs ciprofloxacin for short-course treatment of acute uncomplicated cystitis. A randomized trial. JAMA 2012; 307:583–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brannon JR, Dunigan TL, Beebout CJ, et al. Invasion of vaginal epithelial cells by uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat Commun 2020; 11:2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Forrest A, Nix DE, Ballow CH, Goss TF, Birmingham MC, Schentag JJ. Pharmacodynamics of intravenous ciprofloxacin in seriously ill patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 1993; 37:1073–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Thomas-White K, Forster SC, Kumar N, et al. Culturing of female bladder bacteria reveals an interconnected urogenital microbiota. Nat Commun 2018; 9:1557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Banerjee R, Johnson JR. A new clone sweeps clean: the enigmatic emergence of Escherichia coli sequence type 131. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58:4997–5004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.